Count Capodistria on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

His mother was Adamantine Gonemis (; Diamantina Gonemi), a countess, and daughter of the noble Christodoulos Gonemis (). The Gonemis were a

His mother was Adamantine Gonemis (; Diamantina Gonemi), a countess, and daughter of the noble Christodoulos Gonemis (). The Gonemis were a

Kapodistrias moved to

Kapodistrias moved to

The most important task facing the governor of Greece was to forge a modern state and with it a civil society, a task in which the workaholic Kapodistrias toiled at mightily, working from 5 am until 10 pm every night. Upon his arrival, Kapodistrias launched a major reform and modernisation programme that covered all areas. Kapodistrias distrusted the men who led the war of independence, believing them all to be self-interested, petty men whose only concern was power for themselves. Kapodistrias saw himself as the champion of the common people, long oppressed by the Ottomans, but also believed that the Greek people were not ready for democracy yet, saying that to give the Greeks democracy at present would be like giving a boy a razor; the boy did not need the razor and could easily kill himself as he did not know to use it properly. Kapodistrias argued that what the Greek people needed at present was an enlightened autocracy that would lift the nation out of the backwardness and poverty caused by the Ottomans and once a generation or two had passed with the Greeks educated and owning private property could democracy be established. Kapodistrias's role model was the Emperor Alexander I of Russia, whom he argued had been gradually moving Russia towards the norms of Western Europe during his reign, but he had died before he had finished his work.

Kapodistrias often expressed his feelings towards the other Greek leaders in harsh language, at one point saying he would crush the revolutionary leaders: "Il faut éteindre les brandons de la revolution". The Greek politician

The most important task facing the governor of Greece was to forge a modern state and with it a civil society, a task in which the workaholic Kapodistrias toiled at mightily, working from 5 am until 10 pm every night. Upon his arrival, Kapodistrias launched a major reform and modernisation programme that covered all areas. Kapodistrias distrusted the men who led the war of independence, believing them all to be self-interested, petty men whose only concern was power for themselves. Kapodistrias saw himself as the champion of the common people, long oppressed by the Ottomans, but also believed that the Greek people were not ready for democracy yet, saying that to give the Greeks democracy at present would be like giving a boy a razor; the boy did not need the razor and could easily kill himself as he did not know to use it properly. Kapodistrias argued that what the Greek people needed at present was an enlightened autocracy that would lift the nation out of the backwardness and poverty caused by the Ottomans and once a generation or two had passed with the Greeks educated and owning private property could democracy be established. Kapodistrias's role model was the Emperor Alexander I of Russia, whom he argued had been gradually moving Russia towards the norms of Western Europe during his reign, but he had died before he had finished his work.

Kapodistrias often expressed his feelings towards the other Greek leaders in harsh language, at one point saying he would crush the revolutionary leaders: "Il faut éteindre les brandons de la revolution". The Greek politician

In 1831, Kapodistrias ordered the imprisonment of

In 1831, Kapodistrias ordered the imprisonment of

On 19 June 2015 Prime Minister of Greece

On 19 June 2015 Prime Minister of Greece

Count

Count (feminine: countess) is a historical title of nobility in certain European countries, varying in relative status, generally of middling rank in the hierarchy of nobility. Pine, L. G. ''Titles: How the King Became His Majesty''. New York: ...

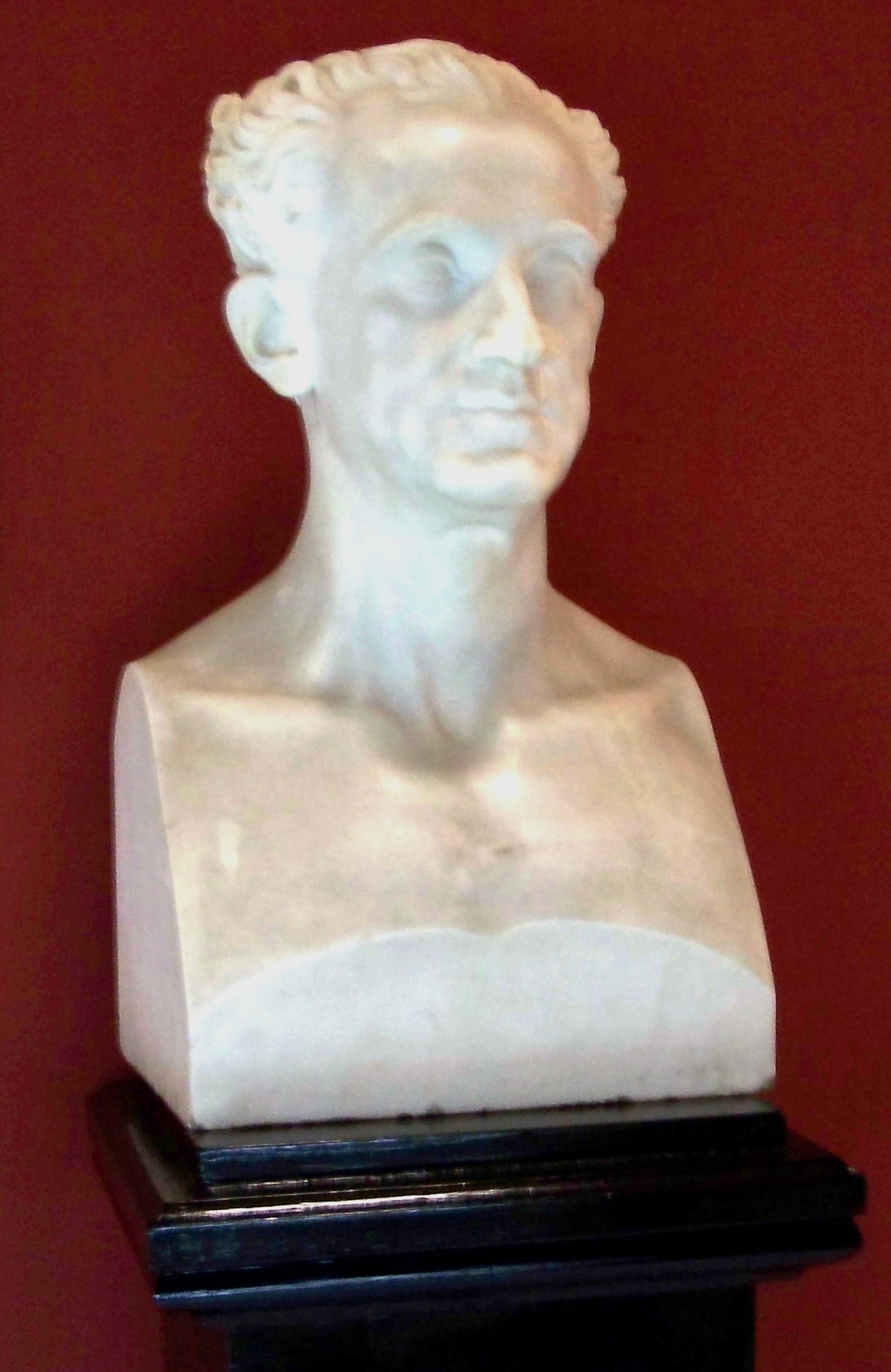

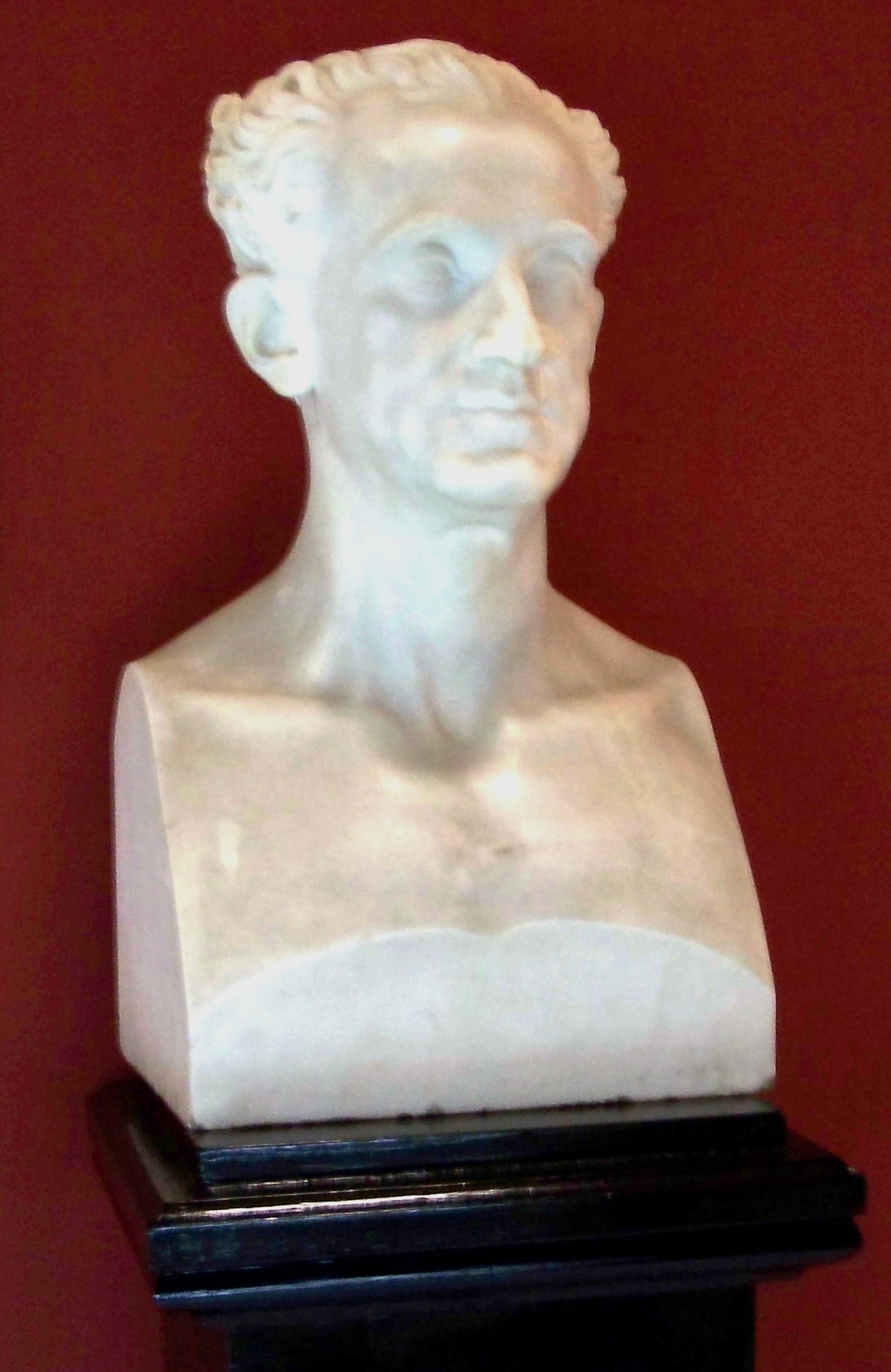

Ioannis Antonios Kapodistrias (; February 1776 –27 September 1831), sometimes anglicized

Anglicisation or anglicization is a form of cultural assimilation whereby something non-English becomes assimilated into or influenced by the culture of England. It can be sociocultural, in which a non-English place adopts the English language ...

as John Capodistrias, was a Greek statesman who was one of the most distinguished politicians and diplomats of 19th-century Europe.

Kapodistrias's involvement in politics began as a minister of the Septinsular Republic

The Septinsular Republic (; ), also known as the Republic of the Seven United Islands, was an oligarchic republic that existed from 1800 to 1807 under nominal Russian and Ottoman sovereignty in the Ionian Islands (Corfu, Paxoi, Lefkada, Cephalon ...

in the early 19th century. He went on to serve as the foreign minister

In many countries, the ministry of foreign affairs (abbreviated as MFA or MOFA) is the highest government department exclusively or primarily responsible for the state's foreign policy and relations, diplomacy, bilateral, and multilateral r ...

of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

from 1816 until his abdication in 1822, when he became increasingly active in supporting the Greek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution or the Greek Revolution of 1821, was a successful war of independence by Greek revolutionaries against the Ottoman Empire between 1821 and 1829. In 1826, the Greeks were assisted ...

that broke out a year earlier.

After a long and distinguished career in European politics and diplomacy, he was elected as the first head of state of independent Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

at the 1827 Third National Assembly at Troezen

The Third National Assembly at Troezen () was a Greek national assembly that convened at Troezen in 1827 during the latter stages of the Greek war of independence. Its aim was to complete the work of the 1826 'Third National Assembly of Epidaur ...

and served as the governor of Greece between 1828 and 1831. For his significant contribution during his governance, he is recognised as the founder of the modern Greek state, and the architect of Greek independence

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution or the Greek Revolution of 1821, was a successful war of independence by Greek revolutionaries against the Ottoman Empire between 1821 and 1829. In 1826, the Greeks were assisted ...

.

Background and early career

Ioannis Kapodistrias was born inCorfu

Corfu ( , ) or Kerkyra (, ) is a Greece, Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands; including its Greek islands, small satellite islands, it forms the margin of Greece's northwestern frontier. The island is part of the Corfu (regio ...

, the most populous Ionian Island

The Ionian Islands (Modern Greek: , ; Ancient Greek, Katharevousa: , ) are a group of islands in the Ionian Sea, west of mainland Greece. They are traditionally called the Heptanese ("Seven Islands"; , ''Heptanēsa'' or , ''Heptanēsos''; ), bu ...

(then under Venetian rule) to a distinguished Corfiote family. Kapodistrias's father was the nobleman, artist and politician Antonios Maria Kapodistrias ().

An ancestor of Kapodistrias had been created a ''conte'' (count) by Charles Emmanuel II, Duke of Savoy

The titles of the count of Savoy, and then duke of Savoy, are titles of nobility attached to the historical territory of Savoy. Since its creation, in the 11th century, the House of Savoy held the county. Several of these rulers ruled as kings at ...

, and the title was later (1679) inscribed in the ''Libro d'Oro

The ''Libro d'Oro'' (''The Golden Book''), originally published between 1315 and 1797, is the formal directory of nobles in the Republic of Venice (including the Ionian Islands). It has been resurrected as the ''Libro d'Oro della Nobiltà It ...

'' of the Corfu nobility; the title originates from the city of Capodistria

Capodistria or Capo d'Istria may refer to:

* Giovanni Capo d'Istria or Capodistria, the Italian name of the Greek statesman Ioannis Kapodistrias

* Capo d'Istria or Capodistria, the Italian name of the city of Koper

See also

*Kapodistrias (disambi ...

(now ''Koper'') in Slovenia

Slovenia, officially the Republic of Slovenia, is a country in Central Europe. It borders Italy to the west, Austria to the north, Hungary to the northeast, Croatia to the south and southeast, and a short (46.6 km) coastline within the Adriati ...

, then part of the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice, officially the Most Serene Republic of Venice and traditionally known as La Serenissima, was a sovereign state and Maritime republics, maritime republic with its capital in Venice. Founded, according to tradition, in 697 ...

and the place of origin of Kapodistrias's paternal family before they moved to Corfu in the 13th century, where they changed their religion from Catholic to Orthodox and they became completely hellenized. His family's name in Capodistria had been Vitori or Vittori. Origins of his paternal ancestors can also be found back in 1423 in Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

(with Victor/Vittoror NikiforosCapodistrias). The coat of arms of the family, which today can be seen in Corfu, represented a cyan shield with a diagonal strip, containing three stars, and a cross.

His mother was Adamantine Gonemis (; Diamantina Gonemi), a countess, and daughter of the noble Christodoulos Gonemis (). The Gonemis were a

His mother was Adamantine Gonemis (; Diamantina Gonemi), a countess, and daughter of the noble Christodoulos Gonemis (). The Gonemis were a Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

family originally from the island of Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

, they had migrated to Crete

Crete ( ; , Modern Greek, Modern: , Ancient Greek, Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the List of islands by area, 88th largest island in the world and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fifth la ...

when Cyprus fell to the Ottomans in the 16th century. They then migrated to Epirus

Epirus () is a Region#Geographical regions, geographical and historical region, historical region in southeastern Europe, now shared between Greece and Albania. It lies between the Pindus Mountains and the Ionian Sea, stretching from the Bay ...

, near Argyrokastro, when Crete fell in the 17th century, finally settling on the Ionian island of Corfu. The Gonemis family, like the Kapodistriases, had been listed in the ''Libro d'Oro'' (Golden Book) of Corfu.

Kapodistrias, though born and raised as a nobleman, was throughout his life a liberal thinker and had democratic ideals. His ancestors fought along with the Venetians during the Ottoman sieges of Corfu and had received a title of nobility from them.

Kapodistrias studied medicine

Medicine is the science and Praxis (process), practice of caring for patients, managing the Medical diagnosis, diagnosis, prognosis, Preventive medicine, prevention, therapy, treatment, Palliative care, palliation of their injury or disease, ...

, philosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

and law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior, with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been variously described as a science and as the ar ...

at the University of Padua

The University of Padua (, UNIPD) is an Italian public research university in Padua, Italy. It was founded in 1222 by a group of students and teachers from the University of Bologna, who previously settled in Vicenza; thus, it is the second-oldest ...

in 1795–97. When he was 21 years old, in 1797, he started his medical practice as a doctor in his native island of Corfu. In 1799, when Corfu was briefly occupied by the forces of Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

and Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

, Kapodistrias was appointed chief medical director of the military hospital. In 1802 he founded an important scientific and social progress organisation in Corfu, the "National Medical Association", of which he was an energetic member.

Some scholars have suggested that Kapodistrias had a romantic affair with Roxandra Sturdza, prior to her marriage with Count Albert Cajetan von Edling in 1816.

Minister of the Septinsular Republic

After two years of revolutionary freedom, triggered by the French Revolution and the ascendancy ofNapoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

, in 1799 Russia and the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

drove the French out of the seven Ionian islands

The Ionian Islands (Modern Greek: , ; Ancient Greek, Katharevousa: , ) are a archipelago, group of islands in the Ionian Sea, west of mainland Greece. They are traditionally called the Heptanese ("Seven Islands"; , ''Heptanēsa'' or , ''Heptanē ...

and organised them as a free and independent state – the Septinsular Republic

The Septinsular Republic (; ), also known as the Republic of the Seven United Islands, was an oligarchic republic that existed from 1800 to 1807 under nominal Russian and Ottoman sovereignty in the Ionian Islands (Corfu, Paxoi, Lefkada, Cephalon ...

– ruled by its nobles

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally appointed by and ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. T ...

. Kapodistrias, substituting for his father, became one of two ministers of the new state. Thus, at the age of 25, Kapodistrias became involved in politics. In Kefalonia

Kefalonia or Cephalonia (), formerly also known as Kefallinia or Kephallonia (), is the largest of the Ionian Islands in western Greece and the 6th-largest island in Greece after Crete, Euboea, Lesbos, Rhodes and Chios. It is also a separate regio ...

he was successful in convincing the populace to remain united and disciplined to avoid foreign intervention and, by his argument and sheer courage, he faced and appeased rebellious opposition without conflict. With the same peaceful determination, he established authority in all the seven islands.

When Russia sent an envoy, Count George Mocenigo

George may refer to:

Names

* George (given name)

* George (surname)

People

* George (singer), American-Canadian singer George Nozuka, known by the mononym George

* George Papagheorghe, also known as Jorge / GEØRGE

* George, stage name of Giorg ...

(1762–1839), a noble from Zakynthos

Zakynthos (also spelled Zakinthos; ; ) or Zante (, , ; ; from the Venetian language, Venetian form, traditionally Latinized as Zacynthus) is a Greece, Greek island in the Ionian Sea. It is the third largest of the Ionian Islands, with an are ...

who had served as Russian Diplomat in Italy, Kapodistrias became his protégé. Mocenigo later helped Kapodistrias to join the Russian diplomatic service.

When elections were carried for a new Ionian Senate

The Ionian Senate () was the executive and later legislative body of the Septinsular Republic (1800–1807/1814) and the executive council of its successor, the United States of the Ionian Islands (1815–1864). During most of its history it was ...

, Kapodistrias was unanimously appointed as Chief Minister of State. In December, 1803, a less feudal and more liberal and democratic constitution was voted by the Senate. As minister of state, he organised the public sector, putting particular emphasis on education. In 1807 the French re-occupied the islands and dissolved the Septinsular Republic.

Russian diplomatic service

In 1809 Kapodistrias entered the service ofAlexander I of Russia

Alexander I (, ; – ), nicknamed "the Blessed", was Emperor of Russia from 1801, the first king of Congress Poland from 1815, and the grand duke of Finland from 1809 to his death in 1825. He ruled Russian Empire, Russia during the chaotic perio ...

. His first important mission, in November 1813, was as unofficial Russian ambassador to Switzerland, with the task of helping disentangle the country from the French dominance imposed by Napoleon. He secured Swiss unity, independence and neutrality, which were formally guaranteed by the Great Powers, and actively facilitated the initiation of a new federal constitution for the 19 cantons

A canton is a type of administrative division of a country. In general, cantons are relatively small in terms of area and population when compared with other administrative divisions such as counties, departments, or provinces. Internationally, th ...

that were the component states of Switzerland, with personal drafts.

Collaborating with Anthimos Gazis

Anthimos Gazis or Gazes (; born Anastasios Gazalis, ; 1758 24 June 1828) was a Greek scholar, revolutionary and politician. He was born in Milies (Thessaly) in Ottoman Greece in 1758 into a family of modest means. In 1774 he became an Eastern Or ...

, in 1814 he founded in Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

the " Philomuse Society", an educational organization promoting philhellenism

Philhellenism ("the love of Greek culture") was an intellectual movement prominent mostly at the turn of the 19th century. It contributed to the sentiments that led Europeans such as Lord Byron, Charles Nicolas Fabvier and Richard Church to a ...

, such as studies for the Greeks in Europe.

In the ensuing Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon, Napol ...

, 1815, as the Russian minister, he counterbalanced the paramount influence of the Austrian minister, Prince Metternich

Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar, Prince of Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein ( ; 15 May 1773 – 11 June 1859), known as Klemens von Metternich () or Prince Metternich, was a Germans, German statesman and diplomat in the service of the Austrian ...

, and insisted on French state unity under a Bourbon Bourbon may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bourbon whiskey, an American whiskey made using a corn-based mash

* Bourbon, a beer produced by Brasseries de Bourbon

* Bourbon biscuit, a chocolate sandwich biscuit

* Bourbon coffee, a type of coffee ma ...

monarch. He also obtained new international guarantees for the constitution and neutrality of Switzerland through an agreement among the Powers. After these brilliant diplomatic successes, Alexander I appointed Kapodistrias joint Foreign Minister of Russia (with Karl Robert Nesselrode

Karl Robert Reichsgraf von Nesselrode-Ehreshoven, also known as Charles de Nesselrode (; 14 December 1780 – 23 March 1862), was a Russian diplomat of German noble descent. For 40 years (1816–1856), Nesselrode guided Russian policy as for ...

).

In the course of his assignment as Foreign Minister of Russia, Kapodistrias's ideas came to represent a progressive alternative to Metternich

Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar, Prince of Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein ( ; 15 May 1773 – 11 June 1859), known as Klemens von Metternich () or Prince Metternich, was a Germans, German statesman and diplomat in the service of the Austrian ...

's aims of Austrian

Austrian may refer to:

* Austrians, someone from Austria or of Austrian descent

** Someone who is considered an Austrian citizen

* Austrian German dialect

* Something associated with the country Austria, for example:

** Austria-Hungary

** Austria ...

domination of Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

an affairs. Kapodistrias's liberal ideas of a new European order so threatened Metternich that he wrote in 1819: Realising that Kapodistrias's progressive vision was antithetical to his own, Metternich then tried to undermine Kapodistrias's position in the Russian court. Although Metternich was not a decisive factor in Kapodistrias's leaving his post as Russian Foreign Minister, he nevertheless attempted to actively undermine Kapodistrias by rumour and innuendo. According to the French ambassador to Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

, Metternich was a master of insinuation, and he attempted to neutralise Kapodistrias, viewing him as the only man capable of counterbalancing Metternich's own influence with the Russian court.

Metternich, by default, succeeded in the short term, since Kapodistrias eventually left the Russian court on his own, but with time, Kapodistrias's ideas and policies for a new Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

an order prevailed.

He was always keenly interested in the cause of his native country, and in particular the state of affairs in the Seven Islands, which in a few decades' time had passed from French revolutionary influence to Russian protection and then to British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

rule. He always tried to attract his Emperor's attention to matters Greek. In January 1817, an emissary from the Filiki Eteria

Filiki Eteria () or Society of Friends () was a secret political and revolutionary organization founded in 1814 in Odesa, Odessa, whose purpose was to overthrow Ottoman Empire, Ottoman rule in Ottoman Greece, Greece and establish an Independenc ...

, Nikolaos Galatis

Nikolaos Galatis (; c. 1792–1819) was a Greeks, Greek pre-Greek Revolution, revolutionary figure from Ithaca (island), Ithaca and one of the founding members of the Filiki Eteria, Filiki Etairia, the secret revolutionary society. He was initiat ...

, arrived in St. Petersburg to offer Kapodistrias leadership of the movement for Greek independence. Kapodhistrias rejected the offer, telling Galátis:

In December 1819, another emissary from the Filiki Eteria, Kamarinós, arrived in St. Petersburg, this time representing Petrobey Mavromichalis

Petros Mavromichalis (; 1765–1848), also known as Petrobey ( ), was a Greek general and politician who played a major role in the lead-up and during the Greek War of Independence. Before the war, he served as the Bey of Mani. His family h ...

with a request that Russia support an uprising against the Ottomans. Kapodistrias wrote a long and careful letter, which while expressing support for Greek independence in theory, explained that at present it was not possible for Russia to support such an uprising and advised Mavromichalis to call off the revolution before it started. Still undaunted, one of the leaders of the Filiki Eteria, Emmanuel Xánthos arrived in St. Petersburg to again appeal to Kapodistrias to have Russia support the planned revolution and was again informed that the Russian Foreign Minister "... could not become involved for the above reasons and that if the ''arkhigoi'' knew of other means to carry out their objective, let them use them". When Prince Alexander Ypsilantis

Alexandros Ypsilantis (12 December 1792 – 31 January 1828) was a Greek nationalist politician who was member of a prominent Phanariot Greeks, Phanariot Greek family, a prince of the Danubian Principalities, a senior officer of the Imperial R ...

asked Kapodistrias to support the planned revolution, Kapodistrias advised against going ahead, saying: "Those drawing up such plans are most guilty and it is they who are driving Greece to calamity. They are wretched hucksters destroyed by their own evil conduct and now taking money from simple souls in the name of the fatherland they do not possess. They want you in their conspiracy to inspire trust in their operations. I repeat: be on your guard against these men". Kapodistrias visited his Ionian homeland, by then under British rule, in 1818, and in 1819 he went to London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

to discuss the islanders' grievances with the British government, but the British gave him the cold shoulder, partly because, uncharacteristically, he refused to show them the memorandum he wrote to the czar about the subject.

In 1821, when Kapodistrias learned that Prince Alexander Ypsilantis

Alexandros Ypsilantis (12 December 1792 – 31 January 1828) was a Greek nationalist politician who was member of a prominent Phanariot Greeks, Phanariot Greek family, a prince of the Danubian Principalities, a senior officer of the Imperial R ...

had invaded the Ottoman protectorate of Moldavia

Moldavia (, or ; in Romanian Cyrillic alphabet, Romanian Cyrillic: or ) is a historical region and former principality in Eastern Europe, corresponding to the territory between the Eastern Carpathians and the Dniester River. An initially in ...

(modern north-eastern Romania) with the aim of provoking a general uprising in the Balkans against the Ottoman Empire, Kapodistrias was described as being "like a man struck by a thunderbolt". Czar Alexander, committed to upholding the established order in Europe, had no interest in supporting a revolt against the Ottoman Empire, and it thus fell to Kapodistrias to draft a declaration in Alexander's name denouncing Ypsilantis for abandoning "the precepts of religion and morality", condemning him for his "obscure devices and shady plots", ordering him to leave Moldavia at once and announcing that Russia would offer him no support. As a fellow Greek, Kapodistrias found this document difficult to draft, but his sense of loyalty to Alexander outweighed his sympathy for Ypsilantis. On Easter Sunday, 22 April 1821, the Sublime Porte had the Patriarch Grigorios V publicly hanged in Constantinople at the gate of his residence in Phanar

Fener (; ), also spelled Phanar, is a quarter midway up the Golden Horn in the district of Fatih in Istanbul, Turkey. The Turkish name is derived from the Greek word "phanarion" (Medieval Greek: Φανάριον), meaning lantern, streetlight or ...

. This, together with other news that the Ottomans were killing Orthodox priests, led Alexander to have Kapodistrias draft an ultimatum accusing the Ottomans of having trampled on the rights of their Orthodox subjects, of breaking treaties, insulting the Orthodox churches everywhere by hanging the Patriarch and of threatening "to disturb the peace that Europe has bought at so great a sacrifice". Kapodistrias ended his ultimatum: As the Sublime Porte declined to answer the Russian ultimatum within the seven day period allowed after it was presented by the ambassador Baron Georgii Stroganov on 18 July 1821, Russia broke off diplomatic relations with the Ottoman Empire. Kapodistrias became increasingly active in support of Greek independence

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution or the Greek Revolution of 1821, was a successful war of independence by Greek revolutionaries against the Ottoman Empire between 1821 and 1829. In 1826, the Greeks were assisted ...

from the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, but did not succeed in obtaining Alexander's support for the Greek revolution of 1821. This put Kapodistrias in an untenable situation and in 1822 he took an extended leave of absence from his position as Foreign Minister and retired to Geneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rhône exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

where he applied himself to supporting the Greek revolution by organising material and moral support.

Return to Greece and the Hellenic State

Kapodistrias moved to

Kapodistrias moved to Geneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rhône exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

, where he was greatly esteemed, having been made an Honorary Citizen for his past services to Swiss unity and particularly to the cantons. In 1827, he learned that the newly formed Greek National Assembly had, as he was the most illustrious Greek-born statesman in Europe, elected him as the first head of state of newly liberated Greece, with the title of ''Kyvernetes'' (Κυβερνήτης – Governor) for a seven-year term. A visitor to Kapodistrias in Geneva described him thus: "If there is to be found anywhere in the world an innate nobility, marked by a distinction of appearance, innocence, and intelligence in the eyes, a graceful simplicity of manner, a natural elegance of expression in any language, no one could be more intrinsically aristocratic than Count Capo d'Istria apodistriasof Corfu". Under the aristocratic veneer, Kapodistrias was an intense workaholic, a driven man and "an ascetic bachelor" who worked from dawn until late at night without a break, a loner whom few really knew well. Despite his work ethic, Kapodistrias had what the British historian David Brewer called an air of "melancholy fatalism" about him. Kapodistrias once wrote about the cause of Greek freedom that "Providence will decide and it will be for the best".

After touring Europe to rally support for the Greek cause, Kapodistrias landed in Nafplion

Nafplio or Nauplio () is a coastal city located in the Peloponnese in Greece. It is the capital of the regional unit of Argolis and an important tourist destination. Founded in antiquity, the city became an important seaport in the Middle Ages du ...

on 7 January 1828, and arrived in Aegina

Aegina (; ; ) is one of the Saronic Islands of Greece in the Saronic Gulf, from Athens. Tradition derives the name from Aegina (mythology), Aegina, the mother of the mythological hero Aeacus, who was born on the island and became its king.

...

on 8 January 1828. The British didn't allow him to pass from his native Corfu (a British protectorate since 1815 as part of the United States of the Ionian Islands

The United States of the Ionian Islands was a Greeks, Greek state (polity), state and Protectorate#Amical_protection, amical protectorate of the United Kingdom between 1815 and 1864. The succession of states, successor state of the Septinsular R ...

) fearing a possible unrest of the population. It was the first time he had ever set foot on the Greek mainland, and he found a discouraging situation there. Even while fighting against the Ottomans continued, factional and dynastic conflicts had led to two civil wars, which ravaged the country. Greece was bankrupt, and the Greeks were unable to form a united national government. Wherever Kapodistrias went in Greece, he was greeted by large and enthusiastic welcomes from the crowds.

Kapodistrias asked the Senate to give him full executive powers and to have the constitution suspended while the Senate was to be replaced with a Panhellenion, whose 27 members were all to be appointed by the governor. All requests were granted. Kapodistrias promised to call a National Assembly for April 1828. But, in fact, it took 18 months for the National Assembly to meet.

He declared the foundation of the Hellenic State and from the first capital of Greece, Nafplion

Nafplio or Nauplio () is a coastal city located in the Peloponnese in Greece. It is the capital of the regional unit of Argolis and an important tourist destination. Founded in antiquity, the city became an important seaport in the Middle Ages du ...

, he ushered in a new era in the country, which had just been liberated from centuries of Ottoman occupation. In September 1828, Kapodistrias at first restrained General Richard Church Richard Church may refer to:

*Richard Church (general) (1784–1873), Irish military officer in the British and Greek army

*Richard William Church (1815–1890), nephew of the general, Dean of St Paul's

*Richard Church (poet) (1893–1972), English ...

from advancing into the Roumeli, hoping that the French would intervene instead. However, a French presence in Central Greece was refused and caused a veto by the British, who favoured the creation of a smaller Greek state, mainly in Peloponnese (Morea). The new British ambassador Edward Dawkins and admiral Malcolm asked from Kapodistrias to retreat the Greek forces to Morea, but he refused to do so and abandon central Greece.

Kapodistrias ordered Church and Ypsilantis

The House of Ypsilantis or Ypsilanti (; ) was a Greek Phanariote family which grew into prominence and power in Constantinople during the last centuries of Ottoman Empire and gave several short-reign '' hospodars'' to the Danubian Principalities ...

to resume their advance, and by April 1829, the Greek forces had taken all of Greece up to the village of Kommeno Artas and the Makrinóros mountains. Kapodistrias insisted on involving himself closely in military operations, much to the intense frustration of his generals. General Ypsilantis

The House of Ypsilantis or Ypsilanti (; ) was a Greek Phanariote family which grew into prominence and power in Constantinople during the last centuries of Ottoman Empire and gave several short-reign '' hospodars'' to the Danubian Principalities ...

was incensed when Kapodistrias visited his camp to accuse him to his face of incompetence, and later refused a letter from him under the grounds it was "a monstrous and unacceptable communication". Church was attacked by Kapodistrias for being insufficiently aggressive, as the governor wanted him to conquer as much land as possible, to create a situation that would favor the Greek claims at the conference tables of London. In February 1829, Kapodistrias made his brother Agostino lieutenant-plenipotentiary of Roumeli, with control over pay, rations and equipment, and a final say over Ypsilantis and Church. Church wrote to Kapodistrias: "Let me ask you seriously to think of the position of a General in Chief of an Army before the enemy who has not the authority to order a payment of a sou, or the delivery of a ration of bread". Kapodistrias also appointed another brother, Viaro, to rule over the islands off eastern Greece, and sent a letter to the Hydriots reading: "Do not examine the actions of the government and do not pass judgement on them, because to do so can lead you into error, with harmful consequences to you".

Administration

The most important task facing the governor of Greece was to forge a modern state and with it a civil society, a task in which the workaholic Kapodistrias toiled at mightily, working from 5 am until 10 pm every night. Upon his arrival, Kapodistrias launched a major reform and modernisation programme that covered all areas. Kapodistrias distrusted the men who led the war of independence, believing them all to be self-interested, petty men whose only concern was power for themselves. Kapodistrias saw himself as the champion of the common people, long oppressed by the Ottomans, but also believed that the Greek people were not ready for democracy yet, saying that to give the Greeks democracy at present would be like giving a boy a razor; the boy did not need the razor and could easily kill himself as he did not know to use it properly. Kapodistrias argued that what the Greek people needed at present was an enlightened autocracy that would lift the nation out of the backwardness and poverty caused by the Ottomans and once a generation or two had passed with the Greeks educated and owning private property could democracy be established. Kapodistrias's role model was the Emperor Alexander I of Russia, whom he argued had been gradually moving Russia towards the norms of Western Europe during his reign, but he had died before he had finished his work.

Kapodistrias often expressed his feelings towards the other Greek leaders in harsh language, at one point saying he would crush the revolutionary leaders: "Il faut éteindre les brandons de la revolution". The Greek politician

The most important task facing the governor of Greece was to forge a modern state and with it a civil society, a task in which the workaholic Kapodistrias toiled at mightily, working from 5 am until 10 pm every night. Upon his arrival, Kapodistrias launched a major reform and modernisation programme that covered all areas. Kapodistrias distrusted the men who led the war of independence, believing them all to be self-interested, petty men whose only concern was power for themselves. Kapodistrias saw himself as the champion of the common people, long oppressed by the Ottomans, but also believed that the Greek people were not ready for democracy yet, saying that to give the Greeks democracy at present would be like giving a boy a razor; the boy did not need the razor and could easily kill himself as he did not know to use it properly. Kapodistrias argued that what the Greek people needed at present was an enlightened autocracy that would lift the nation out of the backwardness and poverty caused by the Ottomans and once a generation or two had passed with the Greeks educated and owning private property could democracy be established. Kapodistrias's role model was the Emperor Alexander I of Russia, whom he argued had been gradually moving Russia towards the norms of Western Europe during his reign, but he had died before he had finished his work.

Kapodistrias often expressed his feelings towards the other Greek leaders in harsh language, at one point saying he would crush the revolutionary leaders: "Il faut éteindre les brandons de la revolution". The Greek politician Spyridon Trikoupis

Spiridon Trikoupis (; 20 April 1788 – 24 February 1873) was a Greek statesman, diplomat, author and orator. He was the first Prime Minister of Greece (1833) and a member of provisional governments of Greece since 1826.

Early life

He was bor ...

wrote: "He apodistriascalled the primates

Primates is an order of mammals, which is further divided into the strepsirrhines, which include lemurs, galagos, and lorisids; and the haplorhines, which include tarsiers and simians ( monkeys and apes). Primates arose 74–63 ...

, Turks masquerading under Christian names; the military chiefs, brigands; the Phanariots, vessels of Satan; and the intellectuals, fools. Only the peasants and the artisans did he consider worthy of his love and protection, and he openly declared that his administration was conducted solely for their benefit". Trikoúpis described Kapodistrias as ''átolmos'' (cautious), a man who liked to move methodically and carefully with as little risk as possible, which led him to micro-manage the government by attempting to be the "minister of everything" as Kapodistrias only trusted himself to govern properly. Kapodistrias alienated many in the Greek elite with his haughty, high-handed manner together with his open contempt for the Greek elites, but he attracted support from several of the captains, such as Theodoros Kolokotronis

Theodoros Kolokotronis (; 3 April 1770 – ) was a Greek general and the pre-eminent leader of the Greek War of Independence (1821–1829) against the Ottoman Empire.

The son of a klepht leader who fought the Ottomans during the Orlov revolt ...

and Yannis Makriyannis who provided the necessary military force to back up Kapodistrias's decisions. Kapodistrias, an elegant, urbane diplomat, educated in Padua and accustomed to the polite society of Europe formed an unlikely, but deep friendship with Kolokotronis, a man of peasant origins and a former ''klepht'' (bandit). Kolokotronis described Kapodistrias as the only man capable of being president as he was not tied to any of the Greek factions, admired him for his concern for the common people who had suffered so much in the war, and liked Kapodistrias's interest in getting things done, regardless of the legal niceties. As Greece had no means of raising taxes, money was always in short supply and Kapodistrias was constantly writing letters to his friend, the Swiss banker Jean-Gabriel Eynard

Jean-Gabriel Eynard (28 December 1775 – 5 February 1863) was a Swiss banker and significant benefactor of the Greek independence movement.

Biography

Jean-Gabriel Eynard although belonging to a family who had settled in Switzerland since the ...

, asking for yet another loan. As a former Russian foreign minister, Kapodistrias was well connected to the European elite and he attempted to use his connections to secure loans for the new Greek state and to achieve the most favorable borders for Greece, which was being debated by Russian, French and British diplomats.

Kapodistrias re-established military unity, bringing an end to the Greek divisions, and re-organised the military establishing regular Army corps in the war against the Ottomans, taking advantage also of the Russo-Turkish War (1828–29)

The Russo-Turkish wars ( ), or the Russo-Ottoman wars (), began in 1568 and continued intermittently until 1918. They consisted of twelve conflicts in total, making them one of the longest series of wars in the history of Europe. All but four of ...

. The new Hellenic Army was then able to reconquer much territory lost to the Ottoman army during the civil wars. The Battle of Petra in September 1829 brought an end to the military operations of the war and secured the Greek dominion in Central Greece. He supported also two unfortunate military expeditions, to Chios and to Crete, but the Great powers decided that these islands were not to be included within the borders of the new state.

He adopted the Byzantine ''Hexabiblos'' of Armenopoulos as an interim civil code, he founded the Panellinion

The ''Panellinion'' () was the name given to the advisory body created on 23 April 1828 by Ioannis Kapodistrias, replacing the Legislative Body, as one of the terms he set to assume the governorship of the new country. The ''Panellinion'' was late ...

, as an advisory body, and a Senate, the first Hellenic Military Academy

The Hellenic Army Academy (, ΣΣΕ), commonly known as the Evelpidon, is a military academy. It is the Officer cadet school of the Greek Army and the oldest third-level educational institution in Greece. It was founded in 1828 in Nafplio by Io ...

, hospitals, orphanages and schools for the children, introduced new agricultural techniques, while he showed interest for the establishment of the first national museums and libraries. In 1830 he granted legal equality to the Jews in the new state; being one of the first European states to do so.

Interested in urban planning for the destroyed Greek cities after the war, he assigned Stamatis Voulgaris

Stamatis Voulgaris or Stamati Bulgari (), was a Greek painter, architect and the first urban planner of modern Greece. He was born in Lefkimmi in the island of Corfu, Venetian Ionian Islands in 1774, and died in 1842. He was also an officer in t ...

to present a new urban plan for the cities of Patras

Patras (; ; Katharevousa and ; ) is Greece's List of cities in Greece, third-largest city and the regional capital and largest city of Western Greece, in the northern Peloponnese, west of Athens. The city is built at the foot of Mount Panachaiko ...

, Argos

Argos most often refers to:

* Argos, Peloponnese, a city in Argolis, Greece

* Argus (Greek myth), several characters in Greek mythology

* Argos (retailer), a catalogue retailer in the United Kingdom

Argos or ARGOS may also refer to:

Businesses

...

, such as the Prónoia quarter in Nafplio

Nafplio or Nauplio () is a coastal city located in the Peloponnese in Greece. It is the capital of the regional unit of Argolis and an important tourist destination. Founded in antiquity, the city became an important seaport in the Middle Ages du ...

as settlement for war refugees.

He introduced also the first modern quarantine

A quarantine is a restriction on the movement of people, animals, and goods which is intended to prevent the spread of disease or pests. It is often used in connection to disease and illness, preventing the movement of those who may have bee ...

system in Greece, which brought epidemics like typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known simply as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella enterica'' serotype Typhi bacteria, also called ''Salmonella'' Typhi. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often th ...

, cholera

Cholera () is an infection of the small intestine by some Strain (biology), strains of the Bacteria, bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea last ...

and dysentery

Dysentery ( , ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications may include dehyd ...

under control for the first time since the start of the War of Independence; negotiated with the Great Powers and the Ottoman Empire the borders and the degree of independence of the Greek state and signed the peace treaty that ended the War of Independence with the Ottomans; introduced the '' phoenix'', the first modern Greek currency; organised local administration; and, in an effort to raise the living standards of the population, introduced the cultivation of the potato

The potato () is a starchy tuberous vegetable native to the Americas that is consumed as a staple food in many parts of the world. Potatoes are underground stem tubers of the plant ''Solanum tuberosum'', a perennial in the nightshade famil ...

into Greece. According to legend, although Kapodistrias ordered that potatoes be handed out to anyone interested, the population was reluctant at first to take advantage of the offer. The legend continues, that he then ordered that the whole shipment of potatoes be unloaded on public display on the docks of Nafplion, and placed it under guard to make the people believe that they were valuable. Soon, people would gather to look at the guarded potatoes and some started to steal them. The guards had been ordered in advance to turn a blind eye to such behaviour, and soon the potatoes had all been "stolen" and Kapodistrias's plan to introduce them to Greece had succeeded.

Furthermore, as part of his programme, he tried to undermine the authority of the traditional clans or dynasties which he considered the useless legacy of a bygone and obsolete era. However, he underestimated the political and military strength of the ''capetanei'' (καπεταναίοι – commanders) who had led the revolt against the Ottoman Turks in 1821, and who had expected a leadership role in the post-revolution Government. When a dispute between the ''capetanei'' of Laconia

Laconia or Lakonia (, , ) is a historical and Administrative regions of Greece, administrative region of Greece located on the southeastern part of the Peloponnese peninsula. Its administrative capital is Sparti (municipality), Sparta. The word ...

and the appointed governor of the province escalated into an armed conflict, he called in Russian troops to restore order, because much of the army was controlled by ''capetanei'' who were part of the rebellion.

Opposition and the Battle of Poros

George Finlay's 1861 ''History of Greek Revolution'' records that by 1831 Kapodistrias's government had become hated, chiefly by the independent Maniates, but also by part of the Roumeliotes and the rich and influential merchant families of Hydra,Spetses

Spetses (, "Pityussa") is an island in Attica, Greece. It is counted among the Saronic Islands group. Until 1948, it was part of the old prefecture of Argolis and Corinthia Prefecture, which is now split into Argolis and Corinthia. In ancient ...

and Psara

Psara (, , ; known in ancient times as /, /) is a Greek island in the Aegean Sea. Together with the small island of Antipsara (population 4) it forms the municipality of Psara. It is part of the Chios regional unit, which is part of the North A ...

. Their interests gradually were identified with the English policy and the most influential of them consisted the core of the so-called English Party

The English Party (), was one of the three informal early Greek parties that dominated the political history of the First Hellenic Republic and the first years of the Kingdom of Greece during the early 19th century, the other two being the Russ ...

.

The French stance, which was in general moderate towards Kapodistrias, became more hostile after the July Revolution

The French Revolution of 1830, also known as the July Revolution (), Second French Revolution, or ("Three Glorious ays), was a second French Revolution after French Revolution, the first of 1789–99. It led to the overthrow of King Cha ...

in 1830.

The Hydriots' customs dues were the chief source of the municipalities' revenue, so they refused to hand these over to Kapodistrias. It appears that Kapodistrias had refused to convene the National Assembly and was ruling as a despot, possibly influenced by his Russian experiences. The municipality of Hydra instructed Admiral Miaoulis and Mavrocordatos

The House of Mavrokordatos (), variously also Mavrocordato, Mavrocordatos, Mavrocordat, Mavrogordato or Maurogordato, is the name of a family of Phanariot Greeks originally from Chios, in which a branch rose to a princely rank and was distinguishe ...

to go to Poros

Poros (; ) is a small Greek island-pair in the southern part of the Saronic Gulf, about south of the port of Piraeus and separated from the Peloponnese by a wide sea channel, with the town of Galatas on the mainland across the strait. Its surf ...

and to seize the Hellenic Navy's fleet there. This Miaoulis did, the intention being to prevent a blockade of the islands, so for a time it seemed as if the National Assembly would be called.

Kapodistrias called on the British and French corps to support him in putting down the rebellion, but they refused to do so, and only the Russian Admiral Pyotr Ivanovich Ricord

Pyotr Ivanovich Ricord, also Petr Rikord (; – ) was a Russian admiral, traveller, scientist, diplomat, writer, shipbuilder, statesman, and public figure.

Pyotr Ricord was born in 1776 in the family of the prime major of Carabinier Ingermanlan ...

took his ships north to Poros. Colonel (later General) Kallergis took a half-trained force of Hellenic Army regulars and a force of irregulars in support. With less than 200 men, Miaoulis was unable to make much of a fight; Fort Heideck on Bourtzi Island was overrun by the regulars and the corvette ''Spetses'' (once Laskarina Bouboulina's ''Agamemnon'') was sunk by Ricord's force. Encircled by the Russians in the harbor and Kallergis's force on land, Poros surrendered. Miaoulis was forced to set charges in the flagship '' Hellas'' and the corvette ''Hydra'', blowing them up when he and his handful of followers returned to Hydra. Kallergis's men were enraged by the loss of the ships and sacked Poros, carrying off plunder to Nafplion.

The loss of the best ships in the fleet crippled the Hellenic Navy for many years, but it also weakened Kapodistrias's position. He did finally call the National Assembly but his other actions triggered more opposition and this led to his downfall.

Assassination

In 1831, Kapodistrias ordered the imprisonment of

In 1831, Kapodistrias ordered the imprisonment of Petrobey Mavromichalis

Petros Mavromichalis (; 1765–1848), also known as Petrobey ( ), was a Greek general and politician who played a major role in the lead-up and during the Greek War of Independence. Before the war, he served as the Bey of Mani. His family h ...

, who had been the leader of the successful uprising against the Turks. Mavromichalis was the Bey

Bey, also spelled as Baig, Bayg, Beigh, Beig, Bek, Baeg, Begh, or Beg, is a Turkic title for a chieftain, and a royal, aristocratic title traditionally applied to people with special lineages to the leaders or rulers of variously sized areas in ...

of the Mani Peninsula

The Mani Peninsula (), also long known by its medieval name Maina or Maïna (), is a geographical and cultural region in the Peloponnese of Southern Greece and home to the Maniots (), who claim descent from the ancient Spartans. The capital ci ...

, one of the wildest and most rebellious parts of Greecethe only section that had retained its independence from the Ottoman Empire and whose resistance had spearheaded the successful revolution. The arrest of their patriarch was a mortal offence to the Mavromichalis family, and on September 27, Petrobey's brother Konstantis and son Georgios Mavromichalis determined to kill Kapodistrias when he went to church that morning at the Church of Saint Spyridon

Spyridon, also Spyridon of Tremithus (Greek: ; c. 270 – 348), is a saint honoured in both the Eastern and Western Christian traditions.

Life

Spyridon was born in Assia, in Cyprus. He worked as a shepherd and was known for his great piety. ...

in Nafplion.

Kapodistrias woke up early in the morning and decided to go to church although his servants and bodyguards urged him to stay at home. When he reached the church he saw his assassins waiting for him. When he reached the church steps, Konstantis and Georgios came close as if to greet him. Suddenly Konstantis drew his pistol and fired, missing, the bullet sticking in the church wall where it is still visible today. Georgios plunged his dagger into Kapodistrias's chest while Konstantis shot him in the head. Konstantis was shot by General Fotomaras, who watched the murder scene from his own window. Georgios managed to escape and hide in the French Embassy; after a few days he surrendered to the Greek authorities. He was sentenced to death by a court-martial and was executed by firing squad. His last wish was that the firing squad not shoot his face, and his last words

Last words are the final utterances before death. The meaning is sometimes expanded to somewhat earlier utterances.

Last words of famous or infamous people are sometimes recorded (although not always accurately), which then became a historical an ...

were "Peace Brothers!"

Ioannis Kapodistrias was succeeded as Governor by his younger brother, Augustinos Kapodistrias

Count Augustinos Ioannis Maria Kapodistrias (; 1778–1857) was a Greek soldier and politician. He was born in Corfu

. Augustinos ruled only for six months, during which the country was very much plunged into chaos. Subsequently, King Otto was given the throne of the newly founded Kingdom of Greece

The Kingdom of Greece (, Romanization, romanized: ''Vasíleion tis Elládos'', pronounced ) was the Greece, Greek Nation state, nation-state established in 1832 and was the successor state to the First Hellenic Republic. It was internationally ...

.

Legacy and honours

Greece

Kapodistrias is greatly honoured in Greece today. In 1944Nikos Kazantzakis

Nikos Kazantzakis (; ; 2 March (Old Style and New Style dates, OS 18 February) 188326 October 1957) was a Greeks, Greek writer, journalist, politician, poet and philosopher. Widely considered a giant of modern Greek literature, he was nominate ...

wrote the play "Capodistria" in his honour. It is a tragedy

A tragedy is a genre of drama based on human suffering and, mainly, the terrible or sorrowful events that befall a tragic hero, main character or cast of characters. Traditionally, the intention of tragedy is to invoke an accompanying catharsi ...

in three acts and was performed at the Greek National Theatre

The National Theatre of Greece () is based in Athens, Greece.

History

The first permanent theatre in modern Greece had been the Boukoura Theatre from 1840, but it had difficulty in managing its operation and stood empty for long periods of ti ...

in 1946 to celebrate the anniversary of 25 March. The University of Athens

The National and Kapodistrian University of Athens (NKUA; , ''Ethnikó kai Kapodistriakó Panepistímio Athinón''), usually referred to simply as the University of Athens (UoA), is a public university in Athens, Greece, with various campuses alo ...

is named "''Kapodistrian''" in his honour; the Greek euro coin

Greek euro coins feature a unique design for each of the eight coins. They were all designed by Georgios Stamatopoulos with the minor coins depicting Greek ships, the middle ones portraying famous Greeks and the two large denominations showing ima ...

of 20 cent bears his face and name, as did the obverse

The obverse and reverse are the two flat faces of coins and some other two-sided objects, including paper money, flags, seals, medals, drawings, old master prints and other works of art, and printed fabrics. In this usage, ''obverse'' ...

of the 500 drachmas

Drachma may refer to:

* Ancient drachma, an ancient Greek currency

* Modern drachma, a modern Greek currency (1833...2002)

* Cretan drachma, currency of the former Cretan State

* Drachma proctocomys, moth species, the only species in the Genus '' ...

banknote of 1983–2001, before the introduction of the euro, and a major administrative reform that reduced the number of municipalities in the late 1990s, named the Kapodistrias reform

Kapodistrias reform (, "Kapodistrias Plan") is the common name of law 2539 of Greece, which reorganised the country's administrative divisions. The law, named after 19th-century Greek statesman (Ioannis Kapodistrias), passed the Hellenic Parliamen ...

, also carries his name. The fears that Britain, France and Russia had of any liberal and Republican movement at the time, because of the Reign of Terror

The Reign of Terror (French: ''La Terreur'', literally "The Terror") was a period of the French Revolution when, following the creation of the French First Republic, First Republic, a series of massacres and Capital punishment in France, nu ...

in the French Revolution, led them to insist on Greece becoming a monarchy after Kapodistrias's death. His summer home in Koukouritsa, Corfu has been converted to a museum commemorating his life and accomplishments and has been named ''Kapodistrias Museum

The Capodistrias Museum – Center of Capodistrian Studies (also known as: The Kapodistrias Museum or Kapodistrias Museum–Centre of Kapodistrian Studies) () is a museum dedicated to the memory and life's work of Ioannis Kapodistrias. It is locate ...

'' in his honour. It was donated by his late grand niece Maria Desylla-Kapodistria

Maria Desylla-Kapodistria (, 1898–1980) was the mayor of Corfu from 1956 until 1959. Her election as mayor on 15 April 1956 made her the first woman elected mayor of a city in the history of modern Greece. She donated the land on which the Kapo ...

, to three cultural societies in Corfu specifically for the aforementioned purposes. Society – Political Party of the Successors of Kapodistrias is a present-day political party in Greece.

Slovenia

On 8 December 2001 in the city Capodistria (Koper

Koper (; ) is the List of cities and towns in Slovenia, fifth-largest city in Slovenia. Located in the Slovenian Istria, Istrian region in the southwestern part of the country, Koper is the main urban center of the Slovene coast. Port of Koper i ...

) of Slovenia

Slovenia, officially the Republic of Slovenia, is a country in Central Europe. It borders Italy to the west, Austria to the north, Hungary to the northeast, Croatia to the south and southeast, and a short (46.6 km) coastline within the Adriati ...

a lifesize statue of Ioannis Kapodistrias was unveiled in the central square of the municipality. The square was renamed after Kapodistrias, since Koper was the place of Kapodistrias's ancestors before they moved to Corfu in the 14th century. The statue was created by Greek sculptor K. Palaiologos and was transported to Koper by a Greek Naval vessel. The ceremony was attended by the Greek ambassador and Eleni Koukou, a Kapodistrias scholar and professor at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens.

In the area of bilateral relations between Greece and Slovenia the Greek minister for Development Dimitris Sioufas met on 24 April 2007 with his counterpart Andrej Vizjak, Economy minister of Slovenia, and among other things he mentioned: "Greece has a special sentimental reason for these relations with Slovenia, because the family of Ioannis Kapodistrias, the first Governor of Greece, hails from Koper of Slovenia. And this is especially important for us."

Switzerland

On 21 September 2009, the city ofLausanne

Lausanne ( , ; ; ) is the capital and largest List of towns in Switzerland, city of the Swiss French-speaking Cantons of Switzerland, canton of Vaud, in Switzerland. It is a hilly city situated on the shores of Lake Geneva, about halfway bet ...

in Switzerland inaugurated a bronze statue of Kapodistrias in Ouchy

Ouchy is a port and a popular lakeside resort south of the centre of Lausanne in Switzerland, at the edge of Lake Geneva ().

Facilities

Very popular with tourists for the views of nearby France (Évian-les-Bains, Thonon), Ouchy is also a ...

. The ceremony was attended by the Foreign Ministers of the Russian Federation, Sergei Lavrov

Sergey Viktorovich Lavrov (, ; born 21 March 1950) is a Russian diplomat who has served as Minister of Foreign Affairs since 2004. He is the longest-serving Russian foreign minister since Andrei Gromyko during the Soviet Union.

Lavrov was b ...

and of Switzerland, Micheline Calmy-Rey

Micheline Anne-Marie Calmy-Rey (born 8 July 1945) is a Swiss politician who served as a Member of the Swiss Federal Council from 2003 to 2011. A member of the Social Democratic Party (SP/PS), she was the head of the Federal Department of Foreign ...

. In addition, the ''allée

In landscaping, an avenue (from the French), alameda (from the Portuguese and Spanish), or allée (from the French), is a straight path or road with a line of trees or large shrubs running along each side, which is used, as its Latin source ' ...

Ioannis-Capodistrias'' in Ouchy at Lausanne was named after him.

The cantons of Geneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rhône exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

and Vaud

Vaud ( ; , ), more formally Canton of Vaud, is one of the Cantons of Switzerland, 26 cantons forming the Switzerland, Swiss Confederation. It is composed of Subdivisions of the canton of Vaud, ten districts; its capital city is Lausanne. Its coat ...

in Switzerland awarded Kapodístrias honorary citizenship.

The ''quai

A wharf ( or wharfs), quay ( , also ), staith, or staithe is a structure on the shore of a harbour or on the bank of a river or canal where ships may dock to load and unload cargo or passengers. Such a structure includes one or more berths ( ...

Capo d'Istria'' in the city of Geneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rhône exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

, Switzerland, is named after Kapodistrias.

Russia

On 19 June 2015 Prime Minister of Greece

On 19 June 2015 Prime Minister of Greece Alexis Tsipras

Alexis Tsipras (, ; born 28 July 1974) is a Greek politician who served as Prime Minister of Greece from 2015 to 2019.

A left-wing figure, Tsipras was leader of the List of political parties in Greece, Greek political party Syriza from 200 ...

, in the first of that day's activities, addressed Russians of Greek descent at a statue of Ioannis Kapodistrias in St. Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea. The city had a population of 5,601, ...

.

International network

On 24 February 2007, the cities of Aegina, Nafplion, Corfu, Koper-Capodistria, andFamagusta

Famagusta, also known by several other names, is a city located on the eastern coast of Cyprus. It is located east of the capital, Nicosia, and possesses the deepest harbour of the island. During the Middle Ages (especially under the maritime ...

(one of the notable families of Famagusta was the Gonemis family, from whom Ioannis Capodistrias mother, Adamantine Gonemis, was descended) created the Ioannis Kapodistrias Network, a network of municipalities which are associated with the late governor. The network aims to promote the life and vision of Ioannis Kapodistrias across borders. The presidency of the network is currently held by the Greek municipality of Nafplion.

Notes

References

Further reading

* * Stella Ghervas, "Le philhellénisme russe : union d'amour ou d'intérêt?", in ''Regards sur le philhellénisme'',Geneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rhône exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

, Permanent Mission of Greece to the United Nations (Mission permanente de la Grèce auprès de l'ONU), 2008.

* Stella Ghervas, ''Réinventer la tradition. Alexandre Stourdza et l'Europe de la Sainte-Alliance'', Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

, Honoré Champion

Honoré Champion (1846–1913) was a French publisher. He founded Éditions Honoré Champion in 1874 and published scientific works geared towards laymen, particularly concerning history and literature.

Champion died from an embolism on 8 April ...

, 2008.

* Stella Ghervas, "Spas' political virtues : Capodistria at Ems (1826)", ''Analecta Histórico Médica'', IV, 2006 (with A. Franceschetti).

* Mathieu Grenet, ''La fabrique communautaire. Les Grecs à Venise, Livourne et Marseille, 1770–1840'', Athens and Rome, École française d'Athènes and École française de Rome, 2016 ()

* Michalopoulos, Dimitris, America, Russia and the Birth of Modern Greece, Washington-London: Academica Press, 2020, .

External links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Kapodistrias, Ioannis 1776 births 1831 deaths 18th-century Greek people 19th-century heads of state of Greece 19th-century prime ministers of Greece 19th-century Greek physicians Politicians from Corfu Greek people of Cypriot descent Greek people of Italian descent Greek nobility 19th-century Italian nobility Eastern Orthodox Christians from Greece Assassinated Greek politicians Deaths by firearm in Greece Foreign ministers of the Russian Empire Russo-Turkish War (1828–1829) Politicians from the Russian Empire People murdered in Greece Greek independence activists Septinsular Republic People murdered in 1831 Kapodistrias family 19th-century Greek scientists K Assassinated heads of state in Europe Politicians assassinated in the 1830s Greek Freemasons Ambassadors of the Russian Empire to Switzerland 19th-century Greek diplomats