Cosmology in medieval Islam on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Islamic cosmology is the

The basic structure of the Islamic cosmos was one constituted of seven stacked layers of both heaven and earth. Humans live on the uppermost layer of the earth, whereas the bottommost layer is hell and the residence of the devil. The bottommost layer of heaven, directly above the earth, is the sky, whereas the uppermost one is

The basic structure of the Islamic cosmos was one constituted of seven stacked layers of both heaven and earth. Humans live on the uppermost layer of the earth, whereas the bottommost layer is hell and the residence of the devil. The bottommost layer of heaven, directly above the earth, is the sky, whereas the uppermost one is

The Hellenistic Greek astronomer

The Hellenistic Greek astronomer

In 1984, Abdelhamid Sabra coined the term "Andalusian Revolt" to describe an event beginning among twelfth century astronomers in

In 1984, Abdelhamid Sabra coined the term "Andalusian Revolt" to describe an event beginning among twelfth century astronomers in

Other achievements of the Maragha school include the observational evidences for the

Other achievements of the Maragha school include the observational evidences for the  An area of active discussion in the Maragheh school, and later the

An area of active discussion in the Maragheh school, and later the

cosmology

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe, the cosmos. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', with the meaning of "a speaking of the wo ...

of Islamic societies. Islamic cosmology is not a single unitary system, but is inclusive of a number of cosmological systems, including Quran

The Quran, also Romanization, romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a Waḥy, revelation directly from God in Islam, God (''Allah, Allāh''). It is organized in 114 chapters (, ) which ...

ic cosmology, the cosmology of the Hadith

Hadith is the Arabic word for a 'report' or an 'account f an event and refers to the Islamic oral tradition of anecdotes containing the purported words, actions, and the silent approvals of the Islamic prophet Muhammad or his immediate circle ...

collections, as well as those of Islamic astronomy

Medieval Islamic astronomy comprises the astronomical developments made in the Islamic world, particularly during the Islamic Golden Age (9th–13th centuries), and mostly written in the Arabic language. These developments mostly took place in th ...

and astrology

Astrology is a range of Divination, divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that propose that information about human affairs and terrestrial events may be discerned by studying the apparent positions ...

. Broadly, cosmological conceptions themselves can be divided into thought concerning the physical structure of the cosmos ( cosmography) and the origins of the cosmos (cosmogony

Cosmogony is any model concerning the origin of the cosmos or the universe.

Overview

Scientific theories

In astronomy, cosmogony is the study of the origin of particular astrophysical objects or systems, and is most commonly used in ref ...

).

In Islamic cosmology, the fundamental duality is between Creator (God

In monotheistic belief systems, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. In polytheistic belief systems, a god is "a spirit or being believed to have created, or for controlling some part of the un ...

) and creation.

Quranic cosmology

Overview

In Quranic cosmography, the cosmos is primarily constituted of seven heavens and earth. Above them is the Throne of God, a solid structure. The Quran indicates a round Earth and says the physical land on the ground has been spread. The definition and understanding of such a "spreading of physical land" varies based on scholars and academics.Heavens and the earths

The most important and frequently referred to constitutive features of the Quranic cosmos are the heavens and the earth:The most substantial elements of the qurʾānic universe/cosmos are the (seven) heavens and the earth. The juxtaposition of the heavens (''al-samāʾ''; pl. ''al-samāwāt'') and the earth (''al-arḍ''; not in the plural form in the Qurʾān) is seen in 222 qurʾānic verses. The heavens and the earth are the most vital elements on the scene—in terms of occurrence and emphasis—compared to which all other elements lose importance, and around which all others revolve. The same motif is used in the Bible as well.References to heavens and earth constitute a literary device known as a merism, where two opposites or contrasting terms are used to refer to the totality of something. In Arabic texts, the merism of "the heavens and the earth" is used to refer to the totality of creation. Contemporary and traditional interpretations have generally held in line with general biblical cosmology, with a flat Earth with skies stacked on top of each other, with some believing them to be domes and others flat circles. The Quranic cosmos also includes seven heavens and potentially seven earths as well, although the latter is disputed.

Six day creation

The Quran states that the universe was created in six days using a consistent, quasi-creedal formula (Q 7:54, 10:3, 11:7, 25:59, 32:4, 50:38, 57:4). Quran 41:9–12 represents one of the most developed creation accounts in the Quran:Say: "Do you indeed disbelieve in the One who created the earth in two days i-lladhī khalaqa l-'arḍa fī yawmayni and do you set up rivals to Him? That is the Lord of the worlds. He placed on it firm mountains (towering) above it, and blessed it, and decreed for it its (various) foods in four days, equal to the ones who ask. Then, He mounted (upward) to the sky humma stawā 'ilā l-samā'i while it was (still) smoke a-hiya dukhānun and said to it and to the earth, 'Come, both of you, willingly or unwillingly!' They both said, 'We come willingly'." He finished them (as) seven heavens in two days aḍā-hunna sabʿa samāwātin fī yawmayni and inspired each heaven (with) its affair.This passage contains a number of peculiarities compared with the Genesis creation account, including the formation of the earth before heaven and the idea that heaven existed in a formless state of smoke before being formed by God into its current form.

Cosmography

Theories of the entire cosmos

One theory of the entire cosmos was articulated by Fakhr al-Din al-Razi (1149–1209). In this conception, the entire cosmos can be divided into five spheres: five are part of the celestial sphere of the sun (Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, the fixed stars, and the "Great Sphere" (''al-falak al-aʿẓam'')), five within the sphere of the sun (Venus, Mercury, the moon, the "sublime sphere" (''al-kurrat al-laṭīfah'') of fire and earth, and the "gross sphere" (''al-kurrat al-kathīfah'') of water and earth), and finally the sun itself, which is also the center of the cosmos. For al-Razi, it is also true that the sun, moon, and the stars are themselves distinct from each of the spheres that they move in.Seven heavens

The basic structure of the Islamic cosmos was one constituted of seven stacked layers of both heaven and earth. Humans live on the uppermost layer of the earth, whereas the bottommost layer is hell and the residence of the devil. The bottommost layer of heaven, directly above the earth, is the sky, whereas the uppermost one is

The basic structure of the Islamic cosmos was one constituted of seven stacked layers of both heaven and earth. Humans live on the uppermost layer of the earth, whereas the bottommost layer is hell and the residence of the devil. The bottommost layer of heaven, directly above the earth, is the sky, whereas the uppermost one is Paradise

In religion and folklore, paradise is a place of everlasting happiness, delight, and bliss. Paradisiacal notions are often laden with pastoral imagery, and may be cosmogonical, eschatological, or both, often contrasted with the miseries of human ...

. The physical distance between any two of these layers is equivalent to the distance that could be traversed with 500 years of travel. Other traditions describes the seven heavens

In ancient Near Eastern cosmology, the seven heavens refer to seven firmaments or physical layers located above the open sky. The concept can be found in ancient Mesopotamian religion, Judaism, and Islam. Some traditions complement the seven ...

as each having a notable prophet in residence that Muhammad visits during Miʿrāj: Moses (Musa

Musa may refer to:

Places

*Mūša, a river in Lithuania and Latvia

* Musa, Azerbaijan, a village in Yardymli Rayon

* Musa, Iran, a village in Ilam province, Iran

* Musa, Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari, Iran

* Musa Kalayeh, Gilan province, Iran

* Abu M ...

) on the sixth heaven, Abraham ( Ibrahim) on the seventh heaven, etc.

Shape of the earth

Some scholars, among them the hadith traditionalists, advocated the notion of aflat Earth

Flat Earth is an archaic and scientifically disproven conception of the Figure of the Earth, Earth's shape as a Plane (geometry), plane or Disk (mathematics), disk. Many ancient cultures, notably in the cosmology in the ancient Near East, anci ...

and rejected notions of a round Earth once they had been introduced by the discovery of Hellenistic astronomy, especially the astronomical paradigm developed by Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; , ; ; – 160s/170s AD) was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were important to later Byzantine science, Byzant ...

and elaborated most extensively in his ''Almagest

The ''Almagest'' ( ) is a 2nd-century Greek mathematics, mathematical and Greek astronomy, astronomical treatise on the apparent motions of the stars and planetary paths, written by Ptolemy, Claudius Ptolemy ( ) in Koine Greek. One of the most i ...

''. Debate over the shape of the earth raged on in the medieval Islamic world, including among Kalam

''Ilm al-kalam'' or ''ilm al-lahut'', often shortened to ''kalam'', is the scholastic, speculative, or rational study of Islamic theology ('' aqida''). It can also be defined as the science that studies the fundamental doctrines of Islamic fai ...

theologians.

Multiverse

Al-Ghazali

Al-Ghazali ( – 19 December 1111), archaically Latinized as Algazelus, was a Shafi'i Sunni Muslim scholar and polymath. He is known as one of the most prominent and influential jurisconsults, legal theoreticians, muftis, philosophers, the ...

, in '' The Incoherence of the Philosophers'', defends the Ash'ari

Ash'arism (; ) is a school of theology in Sunni Islam named after Abu al-Hasan al-Ash'ari, a Shāfiʿī jurist, reformer (''mujaddid''), and scholastic theologian, in the 9th–10th century. It established an orthodox guideline, based on ...

doctrine of a created universe that is temporally finite, against the Aristotelian doctrine of an eternal universe. In doing so, he proposed the modal theory of possible world

A possible world is a complete and consistent way the world is or could have been. Possible worlds are widely used as a formal device in logic, philosophy, and linguistics in order to provide a semantics for intensional and modal logic. Their met ...

s, arguing that their actual world is the best of all possible worlds

The phrase "the best of all possible worlds" (; ) was coined by the German polymath and Enlightenment philosopher Gottfried Leibniz in his 1710 work '' Essais de Théodicée sur la bonté de Dieu, la liberté de l'homme et l'origine du mal'' ...

from among all the alternate timeline

Alternate history (also referred to as alternative history, allohistory, althist, or simply A.H.) is a subgenre of speculative fiction in which one or more historical events have occurred but are resolved differently than in actual history. As ...

s and world histories that God could have possibly created.

Al-Razi in his ''Matalib al-'Aliya'' explores the possibility that a multiverse exists in his interpretation of the Qur'an

The Quran, also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation directly from God ('' Allāh''). It is organized in 114 chapters (, ) which consist of individual verses ('). Besides ...

ic verse "All praise belongs to God, Lord of the Worlds." Al-Razi decides that God is capable of creating as many universes as he wishes, and that prior arguments for assuming the existence of a single universe are weak:

Al-Razi therefore rejected the Aristotelian and Avicennian notions of the impossibility of multiple universes and he spent a few pages rebutting the main Aristotelian arguments in this respect. This followed from his affirmation of atomism

Atomism () is a natural philosophy proposing that the physical universe is composed of fundamental indivisible components known as atoms.

References to the concept of atomism and its Atom, atoms appeared in both Ancient Greek philosophy, ancien ...

, as advocated by the Ash'ari

Ash'arism (; ) is a school of theology in Sunni Islam named after Abu al-Hasan al-Ash'ari, a Shāfiʿī jurist, reformer (''mujaddid''), and scholastic theologian, in the 9th–10th century. It established an orthodox guideline, based on ...

school of Islamic theology

Schools of Islamic theology are various Islamic schools and branches in different schools of thought regarding creed. The main schools of Islamic theology include the extant Mu'tazili, Ash'ari, Maturidi, and Athari schools; the extinct ones ...

, which entails the existence of vacant space in which the atoms move, combine and separate. He discussed in greater detail the void, the empty space between stars and constellations in the Universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents. It comprises all of existence, any fundamental interaction, physical process and physical constant, and therefore all forms of matter and energy, and the structures they form, from s ...

, in volume 5 of the ''Matalib''. He argued that there exists an infinite outer space beyond the known world, and that God has the power to fill the vacuum

A vacuum (: vacuums or vacua) is space devoid of matter. The word is derived from the Latin adjective (neuter ) meaning "vacant" or "void". An approximation to such vacuum is a region with a gaseous pressure much less than atmospheric pressur ...

with an infinite number of universes.

Cosmographical writings

''ʿAjā'ib al-makhlūqāt wa gharā'ib al-mawjūdāt

''Aja'ib al-Makhluqat wa Ghara'ib al-Mawjudat'' () or ''The Wonders of Creatures and the Marvels of Creation'' is an important work of paradoxography and cosmography by Zakariya al-Qazwini, who was born in Qazwin in 1203 shortly before the Mongol ...

'' (, meaning ''Marvels of creatures and Strange things existing'') is an important work of cosmography by Zakariya ibn Muhammad ibn Mahmud Abu Yahya al-Qazwini who was born in Qazwin year 600 ( AH (1203 AD).

Cosmogony

Rejection of an eternal universe

In contrast to ancientGreek philosophers

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC. Philosophy was used to make sense of the world using reason. It dealt with a wide variety of subjects, including astronomy, epistemology, mathematics, political philosophy, ethics, metaphysics ...

who believed that the universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents. It comprises all of existence, any fundamental interaction, physical process and physical constant, and therefore all forms of matter and energy, and the structures they form, from s ...

had an infinite past with no beginning, medieval philosophers and theologians

Theology is the study of religious belief from a Religion, religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an Discipline (academia), academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itse ...

developed the concept of the universe having a finite past with a beginning. The Christian philosopher John Philoponus

John Philoponus ( Greek: ; , ''Ioánnis o Philóponos''; c. 490 – c. 570), also known as John the Grammarian or John of Alexandria, was a Coptic Miaphysite philologist, Aristotelian commentator and Christian theologian from Alexandria, Byza ...

, presented the first such argument against the ancient Greek notion of an infinite past. His views were adopted and elaborated in many forms by medieval Jewish and Islamic thinkers, including Saadia Gaon

Saʿadia ben Yosef Gaon (892–942) was a prominent rabbi, Geonim, gaon, Jews, Jewish philosopher, and exegesis, exegete who was active in the Abbasid Caliphate.

Saadia is the first important rabbinic figure to write extensively in Judeo-Arabic ...

among the former and figures like Al-Kindi

Abū Yūsuf Yaʻqūb ibn ʼIsḥāq aṣ-Ṣabbāḥ al-Kindī (; ; ; ) was an Arab Muslim polymath active as a philosopher, mathematician, physician, and music theorist

Music theory is the study of theoretical frameworks for understandin ...

and Al-Ghazali

Al-Ghazali ( – 19 December 1111), archaically Latinized as Algazelus, was a Shafi'i Sunni Muslim scholar and polymath. He is known as one of the most prominent and influential jurisconsults, legal theoreticians, muftis, philosophers, the ...

among the latter. The two arguments used against an actual infinite past include arguments against the possible existence of an actual infinite and arguments against the possibility of arriving to an infinite sum by successive addition. The second argument was especially popularized in the work of Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (born Emanuel Kant; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German Philosophy, philosopher and one of the central Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works ...

. Today, these lines of reasoning form an important component of what is called the Kalam cosmological argument for the existence of God.

Six day creation

The Ismaili thinkerNasir Khusraw

Nasir Khusraw (; 1004 – between 1072–1088) was an Isma'ili poet, philosopher, traveler, and missionary () for the Isma'ili Fatimid Caliphate.

Despite being one of the most prominent Isma'ili philosophers and theologians of the Fatimids and ...

(d. after 1070) believed that the six-day creation period concerned not the creation of the physical cosmos but instead the spiritual one. Each of six days, from the first day of the week (Sunday) until Friday were symbolized by an individual figure, from Adam (Sunday), Noah (Tuesday), Abraham (Wednesday), Moses (Thursday), and Muhammad (who completes the six days on Friday). The seventh and final day was for the allocation of rewards and retribution.

Age of the universe

Early Muslim scholars believed that the world was six to seven thousand years old, and that only a few hundred years were remaining until the end/apocalypse. One tradition attributes to Muhammad a statement directed to his companions: "Your appointed time compared with that of those who were before you is as from the afternoon prayer (Asr prayer

Asr () is the 3rd of the 5 mandatory five daily Islamic prayers.

The Asr prayer consists of four obligatory cycles, rak'a. As with Dhuhr, if it is performed in congregation, the imam is silent except when announcing the takbir, i'tidal, a ...

) to the setting of the sun". Early Muslim Ibn Ishaq

Abu Abd Allah Muhammad ibn Ishaq ibn Yasar al-Muttalibi (; – , known simply as Ibn Ishaq, was an 8th-century Muslim historian and hagiographer who collected oral traditions that formed the basis of an important biography of the Islamic proph ...

estimated the prophet Noah

Noah (; , also Noach) appears as the last of the Antediluvian Patriarchs (Bible), patriarchs in the traditions of Abrahamic religions. His story appears in the Hebrew Bible (Book of Genesis, chapters 5–9), the Quran and Baháʼí literature, ...

lived 1200 years after Adam

Adam is the name given in Genesis 1–5 to the first human. Adam is the first human-being aware of God, and features as such in various belief systems (including Judaism, Christianity, Gnosticism and Islam).

According to Christianity, Adam ...

was expelled from paradise, the prophet Abraham

Abraham (originally Abram) is the common Hebrews, Hebrew Patriarchs (Bible), patriarch of the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In Judaism, he is the founding father who began the Covenant (biblical), covenanta ...

2342 years after Adam, Moses

In Abrahamic religions, Moses was the Hebrews, Hebrew prophet who led the Israelites out of slavery in the The Exodus, Exodus from ancient Egypt, Egypt. He is considered the most important Prophets in Judaism, prophet in Judaism and Samaritani ...

2907 years, Jesus

Jesus (AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Chris ...

4832 years and Muhammad

Muhammad (8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious and political leader and the founder of Islam. Muhammad in Islam, According to Islam, he was a prophet who was divinely inspired to preach and confirm the tawhid, monotheistic teachings of A ...

5432 years.

Astrology

With the sole exception of Fakhr al-Din al-Razi in the 13th century, all notable philosophers that commented on astrology criticized it. However, astrology was often confused and/or conflated with astronomy (and mathematics). For this reason, and to evade the criticisms being made of astrologers, the astronomers themselves (includingal-Farabi

file:A21-133 grande.webp, thumbnail, 200px, Postage stamp of the USSR, issued on the 1100th anniversary of the birth of Al-Farabi (1975)

Abu Nasr Muhammad al-Farabi (; – 14 December 950–12 January 951), known in the Greek East and Latin West ...

, Ibn al-Haytham

Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham (Latinization of names, Latinized as Alhazen; ; full name ; ) was a medieval Mathematics in medieval Islam, mathematician, Astronomy in the medieval Islamic world, astronomer, and Physics in the medieval Islamic world, p ...

, Avicenna

Ibn Sina ( – 22 June 1037), commonly known in the West as Avicenna ( ), was a preeminent philosopher and physician of the Muslim world, flourishing during the Islamic Golden Age, serving in the courts of various Iranian peoples, Iranian ...

, Biruni and Averroes

Ibn Rushd (14 April 112611 December 1198), archaically Latinization of names, Latinized as Averroes, was an Arab Muslim polymath and Faqīh, jurist from Al-Andalus who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astron ...

) would try to carve out a separate identity from them by joining the fray in the attacks against astrology. Their reasons for refuting astrology were often due to both scientific (the methods used by astrologers being conjectural rather than empirical

Empirical evidence is evidence obtained through sense experience or experimental procedure. It is of central importance to the sciences and plays a role in various other fields, like epistemology and law.

There is no general agreement on how t ...

) and religious (conflicts with orthodox Islamic scholars

In Islam, the ''ulama'' ( ; also spelled ''ulema''; ; singular ; feminine singular , plural ) are scholars of Islamic doctrine and law. They are considered the guardians, transmitters, and interpreters of religious knowledge in Islam.

"Ulama ...

) reasons.

Ibn Qayyim Al-Jawziyya

Shams ad-Dīn Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Abī Bakr ibn Ayyūb az-Zurʿī d-Dimashqī l-Ḥanbalī (29 January 1292–15 September 1350 CE / 691 AH–751 AH), commonly known as Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya ("The son of the principal of he scho ...

(1292–1350) spent over two hundred pages of his ''Miftah Dar al-SaCadah'' refuting the practices of divination

Divination () is the attempt to gain insight into a question or situation by way of an occultic ritual or practice. Using various methods throughout history, diviners ascertain their interpretations of how a should proceed by reading signs, ...

, especially in the form of astrology and alchemy. He recognized that the star

A star is a luminous spheroid of plasma (physics), plasma held together by Self-gravitation, self-gravity. The List of nearest stars and brown dwarfs, nearest star to Earth is the Sun. Many other stars are visible to the naked eye at night sk ...

s are much larger than the planet

A planet is a large, Hydrostatic equilibrium, rounded Astronomical object, astronomical body that is generally required to be in orbit around a star, stellar remnant, or brown dwarf, and is not one itself. The Solar System has eight planets b ...

s, and thus argued:

Al-Jawziyya also recognized the Milky Way

The Milky Way or Milky Way Galaxy is the galaxy that includes the Solar System, with the name describing the #Appearance, galaxy's appearance from Earth: a hazy band of light seen in the night sky formed from stars in other arms of the galax ...

galaxy

A galaxy is a Physical system, system of stars, stellar remnants, interstellar medium, interstellar gas, cosmic dust, dust, and dark matter bound together by gravity. The word is derived from the Ancient Greek, Greek ' (), literally 'milky', ...

to be a myriad of individual stars among the fixed stars and therefore that the situation was too complex to infer the influences of such stars.

Astronomy

Reception of Hellenistic astronomy

Much of 9th century astronomy in the Islamic world revolved around the dissemination of the astronomical work ofPtolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; , ; ; – 160s/170s AD) was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were important to later Byzantine science, Byzant ...

, primarily through his ''Almagest

The ''Almagest'' ( ) is a 2nd-century Greek mathematics, mathematical and Greek astronomy, astronomical treatise on the apparent motions of the stars and planetary paths, written by Ptolemy, Claudius Ptolemy ( ) in Koine Greek. One of the most i ...

''. Translations of it were produced, and summaries and commentaries of it were also written. In 850, al-Farghani wrote his own summary of the work, titled ''Kitab fi Jawani Ilm al-Nujum'' ("''A compendium of the science of stars''"), a summary of Ptolemic cosmography. The primary purpose of the work was to help explicate Ptolemy's, but it also included some corrections based on the findings of earlier Arab astronomers. Al-Farghani gave revised values for the obliquity of the ecliptic

The ecliptic or ecliptic plane is the orbital plane of Earth's orbit, Earth around the Sun. It was a central concept in a number of ancient sciences, providing the framework for key measurements in astronomy, astrology and calendar-making.

Fr ...

, the precession

Precession is a change in the orientation of the rotational axis of a rotating body. In an appropriate reference frame it can be defined as a change in the first Euler angle, whereas the third Euler angle defines the rotation itself. In o ...

al movement of the apogee

An apsis (; ) is the farthest or nearest point in the orbit of a planetary body about its primary body. The line of apsides (also called apse line, or major axis of the orbit) is the line connecting the two extreme values.

Apsides perta ...

s of the Sun and the Moon, and the circumference of the Earth. The books were widely circulated through the Muslim world, and even translated into Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

. Under the caliph Al-Ma'mun

Abū al-ʿAbbās Abd Allāh ibn Hārūn al-Maʾmūn (; 14 September 786 – 9 August 833), better known by his regnal name al-Ma'mun (), was the seventh Abbasid caliph, who reigned from 813 until his death in 833. His leadership was marked by t ...

, an astronomical program was instituted in Baghdad and Damascus with the stated intention of verifying Ptolemy's observations by comparing the predictions made from his models with new observations. The findings were compiled into a book called al-Zij al-Mumtahan ("The verified tables"), which is widely quoted in later astronomers but itself no longer extant.

Galaxy observation

The Arab astronomer Ibn Haytham (965–1040) "determined that because the Milky Way had noparallax

Parallax is a displacement or difference in the apparent position of an object viewed along two different sightline, lines of sight and is measured by the angle or half-angle of inclination between those two lines. Due to perspective (graphica ...

, it was very remote from the earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to Planetary habitability, harbor life. This is enabled by Earth being an ocean world, the only one in the Solar System sustaining liquid surface water. Almost all ...

and did not belong to the atmosphere." The Persian astronomer Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī (973–1048) proposed the Milky Way galaxy

A galaxy is a Physical system, system of stars, stellar remnants, interstellar medium, interstellar gas, cosmic dust, dust, and dark matter bound together by gravity. The word is derived from the Ancient Greek, Greek ' (), literally 'milky', ...

to be "a collection of countless fragments of the nature of nebulous stars." The Andalusian astronomer Ibn Bajjah

Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Yaḥyà ibn aṣ-Ṣā’igh at-Tūjībī ibn Bājja (), known simply as Ibn Bajja () or his Latinized name Avempace (; – 1138), was an Arab polymath, whose writings include works regarding astronomy, physi ...

("Avempace", d. 1138) proposed that the Milky Way was made up of many stars which almost touched one another and appeared to be a continuous image due to the effect of refraction

In physics, refraction is the redirection of a wave as it passes from one transmission medium, medium to another. The redirection can be caused by the wave's change in speed or by a change in the medium. Refraction of light is the most commo ...

from sublunary material, citing his observation of the conjunction of Jupiter and Mars on 500 AH (1106/1107 AD) as evidence. Ibn Qayyim Al-Jawziyya

Shams ad-Dīn Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Abī Bakr ibn Ayyūb az-Zurʿī d-Dimashqī l-Ḥanbalī (29 January 1292–15 September 1350 CE / 691 AH–751 AH), commonly known as Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya ("The son of the principal of he scho ...

(1292–1350) proposed the Milky Way galaxy to be "a myriad of tiny stars packed together in the sphere of the fixed stars".

In the 10th century, the Persian astronomer Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi (known in the West as ''Azophi'') made the earliest recorded observation of the Andromeda Galaxy

The Andromeda Galaxy is a barred spiral galaxy and is the nearest major galaxy to the Milky Way. It was originally named the Andromeda Nebula and is cataloged as Messier 31, M31, and NGC 224. Andromeda has a Galaxy#Isophotal diameter, D25 isop ...

, describing it as a "small cloud". Al-Sufi also identified the Large Magellanic Cloud

The Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC) is a dwarf galaxy and satellite galaxy of the Milky Way. At a distance of around , the LMC is the second- or third-closest galaxy to the Milky Way, after the Sagittarius Dwarf Spheroidal Galaxy, Sagittarius Dwarf ...

, which is visible from Yemen

Yemen, officially the Republic of Yemen, is a country in West Asia. Located in South Arabia, southern Arabia, it borders Saudi Arabia to Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, the north, Oman to Oman–Yemen border, the northeast, the south-eastern part ...

, though not from Isfahan

Isfahan or Esfahan ( ) is a city in the Central District (Isfahan County), Central District of Isfahan County, Isfahan province, Iran. It is the capital of the province, the county, and the district. It is located south of Tehran. The city ...

; it was not seen by Europeans until Magellan's voyage in the 16th century. These were the first galaxies other than the Milky Way to be observed from Earth. Al-Sufi published his findings in his ''Book of Fixed Stars

''The Book of Fixed Stars'' ( ', literally ''The Book of the Shapes of Stars'') is an Astronomy, astronomical text written by Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi (Azophi) around 964. Following Graeco-Arabic translation movement, the translation movement in the ...

'' in 964.

Early heliocentric models

The Hellenistic Greek astronomer

The Hellenistic Greek astronomer Seleucus of Seleucia

Seleucus of Seleucia ( ''Seleukos''; born c. 190 BC; fl. c. 150 BC) was a Hellenistic astronomer and philosopher. Coming from Seleucia on the Tigris, Mesopotamia, the capital of the Seleucid Empire, or, alternatively, Seleukia on the Erythraea ...

, who advocated a heliocentric

Heliocentrism (also known as the heliocentric model) is a Superseded theories in science#Astronomy and cosmology, superseded astronomical model in which the Earth and Solar System, planets orbit around the Sun at the center of the universe. His ...

model in the 2nd century BC, wrote a work that was later translated into Arabic. A fragment of his work has survived only in Arabic translation, which was later referred to by the Persian philosopher Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi

Abū Bakr al-Rāzī, also known as Rhazes (full name: ), , was a Persian physician, philosopher and alchemist who lived during the Islamic Golden Age. He is widely regarded as one of the most important figures in the history of medicine, and a ...

(865–925).

In the late ninth century, Ja'far ibn Muhammad Abu Ma'shar al-Balkhi (Albumasar) developed a planetary model which some have interpreted as a heliocentric model

Heliocentrism (also known as the heliocentric model) is a superseded astronomical model in which the Earth and planets orbit around the Sun at the center of the universe. Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed th ...

. This is due to his orbit

In celestial mechanics, an orbit (also known as orbital revolution) is the curved trajectory of an object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an artificial satellite around an ...

al revolutions of the planets being given as heliocentric revolutions rather than geocentric revolutions, and the only known planetary theory in which this occurs is in the heliocentric theory. His work on planetary theory has not survived, but his astronomical data was later recorded by al-Hashimi, Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī and al-Sijzi.

In the early eleventh century, al-Biruni

Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni (; ; 973after 1050), known as al-Biruni, was a Khwarazmian Iranian scholar and polymath during the Islamic Golden Age. He has been called variously "Father of Comparative Religion", "Father of modern ...

had met several Indian scholars who believed in a rotating Earth. In his ''Indica'', he discusses the theories on the Earth's rotation

Earth's rotation or Earth's spin is the rotation of planet Earth around its own Rotation around a fixed axis, axis, as well as changes in the orientation (geometry), orientation of the rotation axis in space. Earth rotates eastward, in progra ...

supported by Brahmagupta

Brahmagupta ( – ) was an Indian Indian mathematics, mathematician and Indian astronomy, astronomer. He is the author of two early works on mathematics and astronomy: the ''Brāhmasphuṭasiddhānta'' (BSS, "correctly established Siddhanta, do ...

and other Indian astronomers, while in his ''Canon Masudicus'', al-Biruni writes that Aryabhata

Aryabhata ( ISO: ) or Aryabhata I (476–550 CE) was the first of the major mathematician-astronomers from the classical age of Indian mathematics and Indian astronomy. His works include the '' Āryabhaṭīya'' (which mentions that in 3600 ' ...

's followers assigned the first movement from east to west to the Earth and a second movement from west to east to the fixed stars. Al-Biruni also wrote that al-Sijzi also believed the Earth was moving and invented an astrolabe

An astrolabe (; ; ) is an astronomy, astronomical list of astronomical instruments, instrument dating to ancient times. It serves as a star chart and Model#Physical model, physical model of the visible celestial sphere, half-dome of the sky. It ...

called the "Zuraqi" based on this idea:

In his ''Indica'', al-Biruni briefly refers to his work on the refutation of heliocentrism, the ''Key of Astronomy'', which is now lost:

Early ''Hay'a'' program

Ibn al-Haytham

Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham (Latinization of names, Latinized as Alhazen; ; full name ; ) was a medieval Mathematics in medieval Islam, mathematician, Astronomy in the medieval Islamic world, astronomer, and Physics in the medieval Islamic world, p ...

(Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

ized as Alhazen) wrote a work in the ''hay'a'' tradition of Islamic astronomy known as ''Al-Shukūk ‛alà Baṭlamiyūs'' (''Doubts on Ptolemy''). He criticized Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; , ; ; – 160s/170s AD) was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were important to later Byzantine science, Byzant ...

's astronomical system on theoretical grounds but also sought reconciliation with it. Ibn al-Haytham developed a physical structure of the Ptolemaic system in his ''Treatise on the configuration of the World'', or ''Maqâlah fî ''hay'at'' al-‛âlam'', which became an influential work in the ''hay'a'' tradition. In his ''Epitome of Astronomy'', he insisted that the heavenly bodies "were accountable to the laws of physics."

In 1038, Ibn al-Haytham described the first non-Ptolemaic configuration in ''The Model of the Motions''. His reform was not concerned with cosmology

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe, the cosmos. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', with the meaning of "a speaking of the wo ...

, as he developed a systematic study of celestial kinematics

In physics, kinematics studies the geometrical aspects of motion of physical objects independent of forces that set them in motion. Constrained motion such as linked machine parts are also described as kinematics.

Kinematics is concerned with s ...

that was completely geometric

Geometry (; ) is a branch of mathematics concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. Geometry is, along with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. A mathematician w ...

. This in turn led to innovative developments in infinitesimal

In mathematics, an infinitesimal number is a non-zero quantity that is closer to 0 than any non-zero real number is. The word ''infinitesimal'' comes from a 17th-century Modern Latin coinage ''infinitesimus'', which originally referred to the " ...

geometry

Geometry (; ) is a branch of mathematics concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. Geometry is, along with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. A mathematician w ...

. His reformed model was the first to reject the equant

Equant (or punctum aequans) is a mathematical concept developed by Claudius Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD to account for the observed motion of the planets. The equant is used to explain the observed speed change in different stages of the plane ...

and eccentrics, separate natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe, while ignoring any supernatural influence. It was dominant before the develop ...

from astronomy, free celestial kinematics from cosmology, and reduce physical entities to geometrical entities. The model also propounded the Earth's rotation

Earth's rotation or Earth's spin is the rotation of planet Earth around its own Rotation around a fixed axis, axis, as well as changes in the orientation (geometry), orientation of the rotation axis in space. Earth rotates eastward, in progra ...

about its axis, and the centres of motion were geometrical points without any physical significance, like Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler (27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, Natural philosophy, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best know ...

's model centuries later.

In 1030, Abū al-Rayhān al-Bīrūnī discussed the Indian planetary theories of Aryabhata

Aryabhata ( ISO: ) or Aryabhata I (476–550 CE) was the first of the major mathematician-astronomers from the classical age of Indian mathematics and Indian astronomy. His works include the '' Āryabhaṭīya'' (which mentions that in 3600 ' ...

, Brahmagupta

Brahmagupta ( – ) was an Indian Indian mathematics, mathematician and Indian astronomy, astronomer. He is the author of two early works on mathematics and astronomy: the ''Brāhmasphuṭasiddhānta'' (BSS, "correctly established Siddhanta, do ...

and Varahamihira in his ''Ta'rikh al-Hind'' (Latinized as ''Indica''). Al-Biruni agreed with the Earth's rotation

Earth's rotation or Earth's spin is the rotation of planet Earth around its own Rotation around a fixed axis, axis, as well as changes in the orientation (geometry), orientation of the rotation axis in space. Earth rotates eastward, in progra ...

about its own axis, and while he was initially neutral regarding the heliocentric

Heliocentrism (also known as the heliocentric model) is a Superseded theories in science#Astronomy and cosmology, superseded astronomical model in which the Earth and Solar System, planets orbit around the Sun at the center of the universe. His ...

and geocentric model

In astronomy, the geocentric model (also known as geocentrism, often exemplified specifically by the Ptolemaic system) is a superseded scientific theories, superseded description of the Universe with Earth at the center. Under most geocentric m ...

s, he eventually came to reject heliocentrism towards the end of his life. He remarked that if the Earth rotates on its axis and moves around the Sun, it would remain consistent with his astronomical parameters:

Andalusian Revolt

In 1984, Abdelhamid Sabra coined the term "Andalusian Revolt" to describe an event beginning among twelfth century astronomers in

In 1984, Abdelhamid Sabra coined the term "Andalusian Revolt" to describe an event beginning among twelfth century astronomers in al-Andalus

Al-Andalus () was the Muslim-ruled area of the Iberian Peninsula. The name refers to the different Muslim states that controlled these territories at various times between 711 and 1492. At its greatest geographical extent, it occupied most o ...

where mounting discomfort over the conflicts between theory and observation resulted in astronomers transitioning away from the unquestioned authority of Ptolemy to rejecting his theory in favor of radically different solutions. Nur ad-Din al-Bitruji (d. 1204) rejected the existence of eccentrics and epicycles. Instead, the motions of the planets would be explained by concentric spheres, as explained in his (only extant) work ''al-Murtaʿish fī ʾl-hayʾa'' ("The Revolutionary Book on Astronomy"). The major figures of this "revolt" were, among the astronomers, Ibn al-Zarqālluh, Jābir b. al-Aflaḥ, and al-Biṭrūjī, and among the philosophers, Ibn Bājja (Avempace), Ibn Ṭufayl (the teacher of al-Biṭrūjī), Averroes

Ibn Rushd (14 April 112611 December 1198), archaically Latinization of names, Latinized as Averroes, was an Arab Muslim polymath and Faqīh, jurist from Al-Andalus who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astron ...

, and Maimonides

Moses ben Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (, ) and also referred to by the Hebrew acronym Rambam (), was a Sephardic rabbi and Jewish philosophy, philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah schola ...

.

In the 12th century, Averroes

Ibn Rushd (14 April 112611 December 1198), archaically Latinization of names, Latinized as Averroes, was an Arab Muslim polymath and Faqīh, jurist from Al-Andalus who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astron ...

rejected the eccentric deferents introduced by Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; , ; ; – 160s/170s AD) was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were important to later Byzantine science, Byzant ...

. He rejected the Ptolemaic model and instead argued for a strictly concentric

In geometry, two or more objects are said to be ''concentric'' when they share the same center. Any pair of (possibly unalike) objects with well-defined centers can be concentric, including circles, spheres, regular polygons, regular polyh ...

model of the universe. He wrote the following criticism on the Ptolemaic model of planetary motion:

Averroes' contemporary, Maimonides

Moses ben Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (, ) and also referred to by the Hebrew acronym Rambam (), was a Sephardic rabbi and Jewish philosophy, philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah schola ...

, wrote the following on the planetary model proposed by Ibn Bajjah

Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Yaḥyà ibn aṣ-Ṣā’igh at-Tūjībī ibn Bājja (), known simply as Ibn Bajja () or his Latinized name Avempace (; – 1138), was an Arab polymath, whose writings include works regarding astronomy, physi ...

(Avempace):

Ibn Bajjah also proposed the Milky Way

The Milky Way or Milky Way Galaxy is the galaxy that includes the Solar System, with the name describing the #Appearance, galaxy's appearance from Earth: a hazy band of light seen in the night sky formed from stars in other arms of the galax ...

galaxy

A galaxy is a Physical system, system of stars, stellar remnants, interstellar medium, interstellar gas, cosmic dust, dust, and dark matter bound together by gravity. The word is derived from the Ancient Greek, Greek ' (), literally 'milky', ...

to be made up of many stars but that it appears to be a continuous image due to the effect of refraction

In physics, refraction is the redirection of a wave as it passes from one transmission medium, medium to another. The redirection can be caused by the wave's change in speed or by a change in the medium. Refraction of light is the most commo ...

in the Earth's atmosphere

The atmosphere of Earth is composed of a layer of gas mixture that surrounds the Earth's planetary surface (both lands and oceans), known collectively as air, with variable quantities of suspended aerosols and particulates (which create weathe ...

. Later in the 12th century, his successors Ibn Tufail

Ibn Ṭufayl ( – 1185) was an Arab Andalusian Muslim polymath: a writer, Islamic philosopher, Islamic theologian, physician, astronomer, and vizier.

As a philosopher and novelist, he is most famous for writing the first philosophical nov ...

and Nur Ed-Din Al Betrugi (Alpetragius) were the first to propose planetary models without any equant

Equant (or punctum aequans) is a mathematical concept developed by Claudius Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD to account for the observed motion of the planets. The equant is used to explain the observed speed change in different stages of the plane ...

, epicycles or eccentrics. Their configurations, however, were not accepted due to the numerical predictions of the planetary positions in their models being less accurate than that of the Ptolemaic model, mainly because they followed Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

's notion of perfectly uniform circular motion.

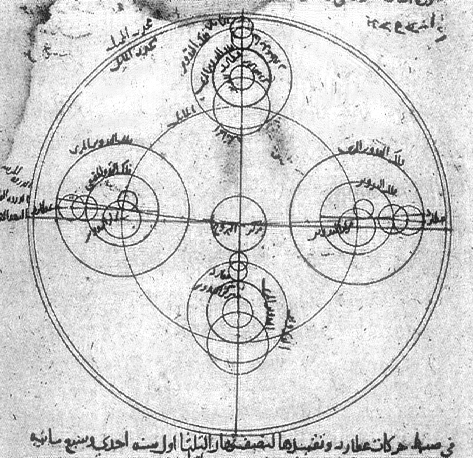

Maragha Revolution

The "Maragha Revolution" refers to theMaragheh

Maragheh () is a city in the Central District (Maragheh County), Central District of Maragheh County, East Azerbaijan province, East Azerbaijan province, Iran, serving as capital of both the county and the district. Maragheh is on the bank of ...

school's revolution

In political science, a revolution (, 'a turn around') is a rapid, fundamental transformation of a society's class, state, ethnic or religious structures. According to sociologist Jack Goldstone, all revolutions contain "a common set of elements ...

against Ptolemaic astronomy in response to the critiques produced by Ibn al-Haytham and the new research programme he introduced. The "Maragha school" was an astronomical tradition beginning in the Maragheh observatory

The Maragheh observatory (Persian language, Persian: رصدخانه مراغه), also spelled Maragha, Maragah, Marageh, and Maraga, was an astronomical observatory established in the mid 13th century under the patronage of the Ilkhanid Hulagu and ...

and continuing with astronomers from Damascus

Damascus ( , ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in the Levant region by population, largest city of Syria. It is the oldest capital in the world and, according to some, the fourth Holiest sites in Islam, holiest city in Islam. Kno ...

and Samarkand

Samarkand ( ; Uzbek language, Uzbek and Tajik language, Tajik: Самарқанд / Samarqand, ) is a city in southeastern Uzbekistan and among the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest continuously inhabited cities in Central As ...

, with the most significance influence by Ibn al-Shatir

ʿAbu al-Ḥasan Alāʾ al‐Dīn bin Alī bin Ibrāhīm bin Muhammad bin al-Matam al-Ansari, known as Ibn al-Shatir or Ibn ash-Shatir (; 1304–1375) was an Arab astronomer, mathematician and engineer. He worked as '' muwaqqit'' (موقت, timek ...

. Like their Andalusian predecessors, the Maragha astronomers attempted to solve the equant

Equant (or punctum aequans) is a mathematical concept developed by Claudius Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD to account for the observed motion of the planets. The equant is used to explain the observed speed change in different stages of the plane ...

problem and produce alternative configurations to the Ptolemaic model. They were more successful than their Andalusian predecessors in producing non-Ptolemaic configurations which eliminated the equant and eccentrics. The most important of the Maragha astronomers included Mo'ayyeduddin Urdi (d. 1266), Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī

Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad ibn al-Ḥasan al-Ṭūsī (1201 – 1274), also known as Naṣīr al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī (; ) or simply as (al-)Tusi, was a Persian polymath, architect, philosopher, physician, scientist, and theologian. Nasir al-Din al-Tu ...

(1201–1274), Najm al-Dīn al-Qazwīnī al-Kātibī (d. 1277), Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi (1236–1311), Sadr al-Sharia al-Bukhari (c. 1347), Ibn al-Shatir

ʿAbu al-Ḥasan Alāʾ al‐Dīn bin Alī bin Ibrāhīm bin Muhammad bin al-Matam al-Ansari, known as Ibn al-Shatir or Ibn ash-Shatir (; 1304–1375) was an Arab astronomer, mathematician and engineer. He worked as '' muwaqqit'' (موقت, timek ...

(1304–1375), Ali Qushji

Ala al-Dīn Ali ibn Muhammed (1403 – 18 December 1474), known as Ali Qushji (Ottoman Turkish language, Ottoman Turkish : علی قوشچی, ''kuşçu'' – falconry, falconer in Turkish language, Turkish; Latin: ''Ali Kushgii'') was a Tim ...

(c. 1474), al-Birjandi (d. 1525) and Shams al-Din al-Khafri (d. 1550).

Some have described their achievements in the 13th and 14th centuries as a "Maragha Revolution", "Maragha School Revolution", or "Scientific Revolution

The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the emergence of History of science, modern science during the early modern period, when developments in History of mathematics#Mathematics during the Scientific Revolution, mathemati ...

before the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

". An important aspect of this revolution included the realization that astronomy should aim to describe the behavior of physical bodies in mathematical

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

language, and should not remain a mathematical hypothesis

A hypothesis (: hypotheses) is a proposed explanation for a phenomenon. A scientific hypothesis must be based on observations and make a testable and reproducible prediction about reality, in a process beginning with an educated guess o ...

, which would only save the phenomena

A phenomenon ( phenomena), sometimes spelled phaenomenon, is an observable Event (philosophy), event. The term came into its modern Philosophy, philosophical usage through Immanuel Kant, who contrasted it with the noumenon, which ''cannot'' be ...

. The Maragha astronomers also realized that the Aristotelian view of motion

In physics, motion is when an object changes its position with respect to a reference point in a given time. Motion is mathematically described in terms of displacement, distance, velocity, acceleration, speed, and frame of reference to an o ...

in the universe being only circular or linear

In mathematics, the term ''linear'' is used in two distinct senses for two different properties:

* linearity of a '' function'' (or '' mapping'');

* linearity of a '' polynomial''.

An example of a linear function is the function defined by f(x) ...

was not true, as the Tusi-couple showed that linear motion could also be produced by applying circular motion

In physics, circular motion is movement of an object along the circumference of a circle or rotation along a circular arc. It can be uniform, with a constant rate of rotation and constant tangential speed, or non-uniform with a changing rate ...

s only.

Other achievements of the Maragha school include the observational evidences for the

Other achievements of the Maragha school include the observational evidences for the Earth's rotation

Earth's rotation or Earth's spin is the rotation of planet Earth around its own Rotation around a fixed axis, axis, as well as changes in the orientation (geometry), orientation of the rotation axis in space. Earth rotates eastward, in progra ...

on its axis by al-Tusi and Qushji (though this was rejected by their colleagues), the separation of natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe, while ignoring any supernatural influence. It was dominant before the develop ...

from astronomy by Ibn al-Shatir and Qushji, the rejection of the Ptolemaic model on empirical rather than philosophical

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

grounds by Ibn al-Shatir, and the development of mathematically identical models to the heliocentric Copernical model (though they remained geocentric).

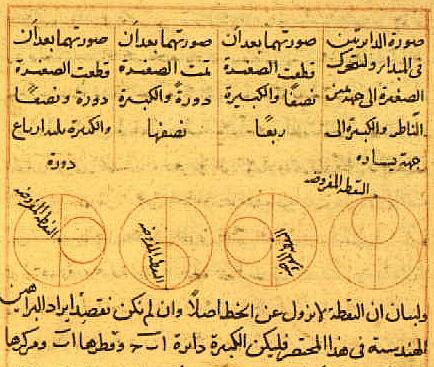

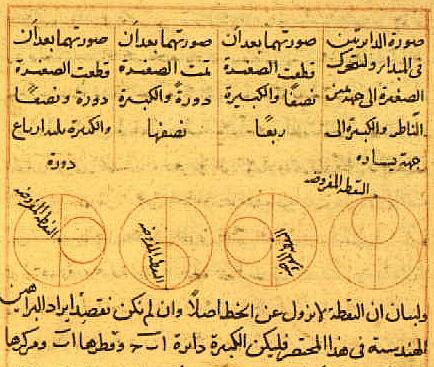

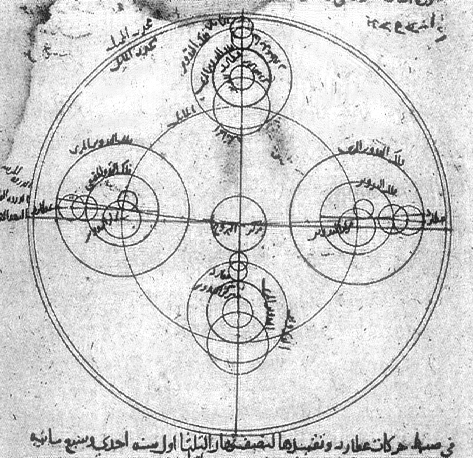

Mo'ayyeduddin Urdi (d. 1266) was the first of the Maragheh astronomers to develop a non-Ptolemaic model, and he proposed a new theorem, the "Urdi lemma". Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī

Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad ibn al-Ḥasan al-Ṭūsī (1201 – 1274), also known as Naṣīr al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī (; ) or simply as (al-)Tusi, was a Persian polymath, architect, philosopher, physician, scientist, and theologian. Nasir al-Din al-Tu ...

(1201–1274) resolved significant problems in the Ptolemaic system by developing the Tusi-couple as an alternative to the physically problematic equant

Equant (or punctum aequans) is a mathematical concept developed by Claudius Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD to account for the observed motion of the planets. The equant is used to explain the observed speed change in different stages of the plane ...

introduced by Ptolemy for every planet except Mercury. Ibn al-Shatir was able to extend this result to Mercury as well. Ibn al-Shatir

ʿAbu al-Ḥasan Alāʾ al‐Dīn bin Alī bin Ibrāhīm bin Muhammad bin al-Matam al-Ansari, known as Ibn al-Shatir or Ibn ash-Shatir (; 1304–1375) was an Arab astronomer, mathematician and engineer. He worked as '' muwaqqit'' (موقت, timek ...

(1304–1375) of Damascus

Damascus ( , ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in the Levant region by population, largest city of Syria. It is the oldest capital in the world and, according to some, the fourth Holiest sites in Islam, holiest city in Islam. Kno ...

, in ''A Final Inquiry Concerning the Rectification of Planetary Theory'', based on a number of issues he recognized in Ptolemy's model of the sun on the basis of observations (including his own), devised a new solar model.

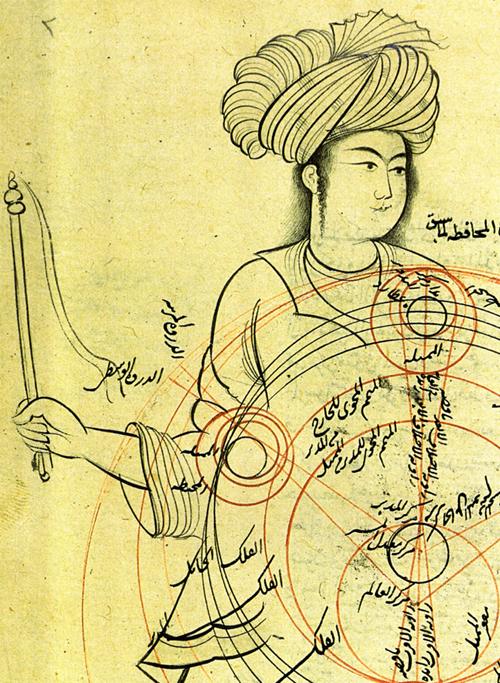

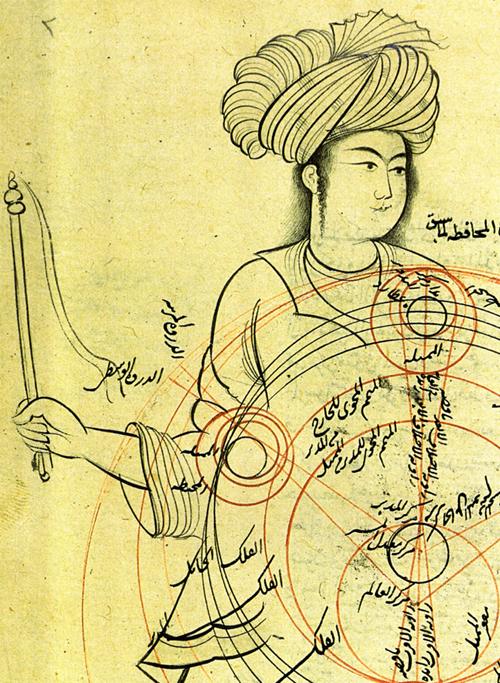

An area of active discussion in the Maragheh school, and later the

An area of active discussion in the Maragheh school, and later the Samarkand

Samarkand ( ; Uzbek language, Uzbek and Tajik language, Tajik: Самарқанд / Samarqand, ) is a city in southeastern Uzbekistan and among the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest continuously inhabited cities in Central As ...

and Istanbul

Istanbul is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, constituting the country's economic, cultural, and historical heart. With Demographics of Istanbul, a population over , it is home to 18% of the Demographics ...

observatories, was the possibility of the Earth's rotation

Earth's rotation or Earth's spin is the rotation of planet Earth around its own Rotation around a fixed axis, axis, as well as changes in the orientation (geometry), orientation of the rotation axis in space. Earth rotates eastward, in progra ...

. Supporters of this theory included Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī

Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad ibn al-Ḥasan al-Ṭūsī (1201 – 1274), also known as Naṣīr al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī (; ) or simply as (al-)Tusi, was a Persian polymath, architect, philosopher, physician, scientist, and theologian. Nasir al-Din al-Tu ...

, Nizam al-Din al-Nisaburi (c. 1311), al-Sayyid al-Sharif al-Jurjani (1339–1413), Ali Qushji (d. 1474), and Abd al-Ali al-Birjandi (d. 1525). Al-Tusi was the first to present empirical observational evidence of the Earth's rotation, using the location of comet

A comet is an icy, small Solar System body that warms and begins to release gases when passing close to the Sun, a process called outgassing. This produces an extended, gravitationally unbound atmosphere or Coma (cometary), coma surrounding ...

s relevant to the Earth as evidence, which Qushji elaborated on with further empirical observations while rejecting Aristotelian natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe, while ignoring any supernatural influence. It was dominant before the develop ...

altogether. Both of their arguments were similar to the arguments later used by Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath who formulated a mathematical model, model of Celestial spheres#Renaissance, the universe that placed heliocentrism, the Sun rather than Earth at its cen ...

in 1543 to explain the Earth's rotation (see Astronomical physics and Earth's motion section below).

Experimental astrophysics and celestial mechanics

In the 9th century, the eldest Banū Mūsā brother, Ja'far Muhammad ibn Mūsā ibn Shākir, made significant contributions to Islamic astrophysics andcelestial mechanics

Celestial mechanics is the branch of astronomy that deals with the motions of objects in outer space. Historically, celestial mechanics applies principles of physics (classical mechanics) to astronomical objects, such as stars and planets, to ...

. He was the first to hypothesize that the heavenly bodies and celestial spheres

The celestial spheres, or celestial orbs, were the fundamental entities of the cosmological models developed by Plato, Eudoxus, Aristotle, Ptolemy, Copernicus, and others. In these celestial models, the apparent motions of the fixed star ...

are subject to the same laws of physics as Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to Planetary habitability, harbor life. This is enabled by Earth being an ocean world, the only one in the Solar System sustaining liquid surface water. Almost all ...

, unlike the ancients who believed that the celestial spheres followed their own set of physical laws different from that of Earth.

In the early 11th century, Ibn al-Haytham

Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham (Latinization of names, Latinized as Alhazen; ; full name ; ) was a medieval Mathematics in medieval Islam, mathematician, Astronomy in the medieval Islamic world, astronomer, and Physics in the medieval Islamic world, p ...

(Alhazen) wrote the ''Maqala fi daw al-qamar'' (''On the Light of the Moon'') some time before 1021. He combined Aristotelian physics with the ancient mathematics (astronomy and optics). He disproved the universally held opinion that the Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It Orbit of the Moon, orbits around Earth at Lunar distance, an average distance of (; about 30 times Earth diameter, Earth's diameter). The Moon rotation, rotates, with a rotation period (lunar ...

reflects sunlight

Sunlight is the portion of the electromagnetic radiation which is emitted by the Sun (i.e. solar radiation) and received by the Earth, in particular the visible spectrum, visible light perceptible to the human eye as well as invisible infrare ...

and correctly concluded that it "emits light from those portions of its surface which the sun

The Sun is the star at the centre of the Solar System. It is a massive, nearly perfect sphere of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core, radiating the energy from its surface mainly as visible light a ...

's light strikes." In order to prove that "light is emitted from every point of the Moon's illuminated surface," he built an "ingenious experiment

An experiment is a procedure carried out to support or refute a hypothesis, or determine the efficacy or likelihood of something previously untried. Experiments provide insight into cause-and-effect by demonstrating what outcome occurs whe ...

al device." Ibn al-Haytham had "formulated a clear conception of the relationship between an ideal mathematical model and the complex of observable phenomena; in particular, he was the first to make a systematic use of the method of varying the experimental conditions in a constant and uniform manner, in an experiment showing that the intensity

Intensity may refer to:

In colloquial use

* Strength (disambiguation)

*Amplitude

* Level (disambiguation)

* Magnitude (disambiguation)

In physical sciences

Physics

*Intensity (physics), power per unit area (W/m2)

*Field strength of electric, m ...

of the light-spot formed by the projection of the moonlight

Moonlight consists of mostly sunlight (with little earthlight) reflected from the parts of the Moon's surface where the Sun's light strikes.

History

The ancient Greek philosopher Anaxagoras was aware that "''the sun provides the moon with its ...

through two small aperture

In optics, the aperture of an optical system (including a system consisting of a single lens) is the hole or opening that primarily limits light propagated through the system. More specifically, the entrance pupil as the front side image o ...

s onto a screen diminishes constantly as one of the apertures is gradually blocked up." Ibn al-Haytham, in his ''Book of Optics

The ''Book of Optics'' (; or ''Perspectiva''; ) is a seven-volume treatise on optics and other fields of study composed by the medieval Arab scholar Ibn al-Haytham, known in the West as Alhazen or Alhacen (965–c. 1040 AD).

The ''Book ...

'' (1021) also suggested that heaven, the location of the fixed stars, was less dense than air.

In the 12th century, Fakhr al-Din al-Razi participated in the debate among Islamic scholars over whether the celestial spheres

The celestial spheres, or celestial orbs, were the fundamental entities of the cosmological models developed by Plato, Eudoxus, Aristotle, Ptolemy, Copernicus, and others. In these celestial models, the apparent motions of the fixed star ...

or orbits (''falak'') are "to be considered as real, concrete physical bodies" or "merely the abstract circles in the heavens traced out year in and year out by the various stars and planets." He points out that many astronomers prefer to see them as solid spheres "on which the stars turn," while others, such as the Islamic scholar Dahhak, view the celestial sphere as "not a body but merely the abstract orbit traced by the stars." Al-Razi himself remains "undecided as to which celestial models, concrete or abstract, most conform with external reality," and notes that "there is no way to ascertain the characteristics of the heavens," whether by "observable" evidence or by authority (''al-khabar'') of "divine revelation

Revelation, or divine revelation, is the disclosing of some form of truth or knowledge through communication with a deity (god) or other supernatural entity or entities in the view of religion and theology.

Types Individual revelation

Thomas A ...

or prophetic traditions." He concludes that "astronomical models, whatever their utility or lack thereof for ordering the heavens, are not founded on sound rational proofs, and so no intellectual commitment can be made to them insofar as description and explanation of celestial realities are concerned."

The theologian Adud al-Din al-Iji (1281–1355), under the influence of the Ash'ari

Ash'arism (; ) is a school of theology in Sunni Islam named after Abu al-Hasan al-Ash'ari, a Shāfiʿī jurist, reformer (''mujaddid''), and scholastic theologian, in the 9th–10th century. It established an orthodox guideline, based on ...

doctrine of occasionalism, which maintained that all physical effects were caused directly by God's will rather than by natural causes, rejected the Aristotelian principle of an innate principle of circular motion in the heavenly bodies, and maintained that the celestial spheres were "imaginary things" and "more tenuous than a spider's web". His views were challenged by al-Jurjani (1339–1413), who argued that even if the celestial spheres "do not have an external reality, yet they are things that are correctly imagined and correspond to what xistsin actuality".

Astronomical physics and Earth's motion

The work ofAli Qushji

Ala al-Dīn Ali ibn Muhammed (1403 – 18 December 1474), known as Ali Qushji (Ottoman Turkish language, Ottoman Turkish : علی قوشچی, ''kuşçu'' – falconry, falconer in Turkish language, Turkish; Latin: ''Ali Kushgii'') was a Tim ...

(d. 1474), who worked at Samarkand

Samarkand ( ; Uzbek language, Uzbek and Tajik language, Tajik: Самарқанд / Samarqand, ) is a city in southeastern Uzbekistan and among the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest continuously inhabited cities in Central As ...

and then Istanbul

Istanbul is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, constituting the country's economic, cultural, and historical heart. With Demographics of Istanbul, a population over , it is home to 18% of the Demographics ...

, is seen as a late example of innovation in Islamic theoretical astronomy and it is believed he may have possibly had some influence on Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath who formulated a mathematical model, model of Celestial spheres#Renaissance, the universe that placed heliocentrism, the Sun rather than Earth at its cen ...

due to similar arguments concerning the Earth's rotation

Earth's rotation or Earth's spin is the rotation of planet Earth around its own Rotation around a fixed axis, axis, as well as changes in the orientation (geometry), orientation of the rotation axis in space. Earth rotates eastward, in progra ...

. Before Qushji, the only astronomer to present empirical evidence

Empirical evidence is evidence obtained through sense experience or experimental procedure. It is of central importance to the sciences and plays a role in various other fields, like epistemology and law.

There is no general agreement on how the ...

for the Earth's rotation was Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī

Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad ibn al-Ḥasan al-Ṭūsī (1201 – 1274), also known as Naṣīr al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī (; ) or simply as (al-)Tusi, was a Persian polymath, architect, philosopher, physician, scientist, and theologian. Nasir al-Din al-Tu ...

(d. 1274), who used the phenomena of comet

A comet is an icy, small Solar System body that warms and begins to release gases when passing close to the Sun, a process called outgassing. This produces an extended, gravitationally unbound atmosphere or Coma (cometary), coma surrounding ...

s to refute Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; , ; ; – 160s/170s AD) was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were important to later Byzantine science, Byzant ...

's claim that a stationary Earth can be determined through observation. Al-Tusi, however, eventually accepted that the Earth was stationary on the basis of Aristotelian cosmology and natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe, while ignoring any supernatural influence. It was dominant before the develop ...

. By the 15th century, the influence of Aristotelian physics

Aristotelian physics is the form of natural philosophy described in the works of the Greek philosopher Aristotle (384–322 BC). In his work ''Physics'', Aristotle intended to establish general principles of change that govern all natural bodies ...

and natural philosophy was declining due to religious opposition from Islamic theologians such as Al-Ghazali

Al-Ghazali ( – 19 December 1111), archaically Latinized as Algazelus, was a Shafi'i Sunni Muslim scholar and polymath. He is known as one of the most prominent and influential jurisconsults, legal theoreticians, muftis, philosophers, the ...

who opposed to the interference of Aristotelianism

Aristotelianism ( ) is a philosophical tradition inspired by the work of Aristotle, usually characterized by Prior Analytics, deductive logic and an Posterior Analytics, analytic inductive method in the study of natural philosophy and metaphysics ...

in astronomy, opening up possibilities for an astronomy unrestrained by philosophy. Under this influence, Qushji, in his ''Concerning the Supposed Dependence of Astronomy upon Philosophy'', rejected Aristotelian physics and completely separated natural philosophy from astronomy, allowing astronomy to become a purely empirical

Empirical evidence is evidence obtained through sense experience or experimental procedure. It is of central importance to the sciences and plays a role in various other fields, like epistemology and law.

There is no general agreement on how t ...

and mathematical science. This allowed him to explore alternatives to the Aristotelian notion of a stationary Earth, as he explored the idea of a moving Earth. He also observed comets and elaborated on al-Tusi's argument. He took it a step further and concluded, on the basis of empirical evidence rather than speculative philosophy, that the moving Earth theory is just as likely to be true as the stationary Earth theory and that it is not possible to empirically deduce which theory is true.Edith Dudley Sylla, "Creation and nature", in Arthur Stephen McGrade (2003), pp. 178–179, Cambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press was the university press of the University of Cambridge. Granted a letters patent by King Henry VIII in 1534, it was the oldest university press in the world. Cambridge University Press merged with Cambridge Assessme ...

, . His work was an important step away from Aristotelian physics and towards an independent astronomical physics.

Despite the similarity in their discussions regarding the Earth's motion, there is uncertainty over whether Qushji had any influence on Copernicus. However, it is likely that they both may have arrived at similar conclusions due to using the earlier work of al-Tusi as a basis. This is more of a possibility considering "the remarkable coincidence between a passage in ''De revolutionibus'' (I.8) and one in Ṭūsī's ''Tadhkira'' (II.1 in which Copernicus follows Ṭūsī's objection to Ptolemy's "proofs" of the Earth's immobility." This can be considered as evidence that not only was Copernicus influenced by the mathematical models of Islamic astronomers, but may have also been influenced by the astronomical physics they began developing and their views on the Earth's motion.

In the 16th century, the debate on the Earth's motion was continued by al-Birjandi (d. 1528), who in his analysis of what might occur if the Earth were moving, develops a hypothesis similar to Galileo Galilei

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei ( , , ) or mononymously as Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a poly ...

's notion of "circular inertia

Inertia is the natural tendency of objects in motion to stay in motion and objects at rest to stay at rest, unless a force causes the velocity to change. It is one of the fundamental principles in classical physics, and described by Isaac Newto ...

", which he described in the following observational test (as a response to one of Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi's arguments):

See also

* Sufi cosmology *Astronomy in the medieval Islamic world

Medieval Islamic astronomy comprises the astronomical developments made in the Islamic world, particularly during the Islamic Golden Age (9th–13th centuries), and mostly written in the Arabic language. These developments mostly took place in th ...

* Baháʼí cosmology

* Buddhist cosmology

Buddhist cosmology is the description of the shape and evolution of the Universe according to Buddhist Tripitaka, scriptures and Atthakatha, commentaries.

It consists of a temporal and a spatial cosmology. The temporal cosmology describes the ...

* Biblical cosmology

* Hindu cosmology

Hindu cosmology is the description of the universe and its states of matter, cycles within time, physical structure, and effects on living entities according to Hindu texts. Hindu cosmology is also intertwined with the idea of a creator who allo ...

* Jain cosmology

Jain cosmology is the description of the shape and functioning of the Universe (''loka'') and its constituents (such as living beings, matter, space, time etc.) according to Jainism. Jain cosmology considers the universe as an uncreated entity t ...

* Religious cosmology

Religious cosmology is an explanation of the origin, evolution, and eventual fate of the universe from a religious perspective. This may include beliefs on origin in the form of a creation myth, subsequent evolution, current organizational form a ...

* Arcs of Descent and Ascent

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * Daryabadi, Abdul Majid (1941), ''The Holy Qur'an, English Translation'', 57,Lahore

Lahore ( ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the Administrative units of Pakistan, Pakistani province of Punjab, Pakistan, Punjab. It is the List of cities in Pakistan by population, second-largest city in Pakistan, after Karachi, and ...

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

* Nasr, Seyyed Hossein (1993), ''An Introduction to Islamic Cosmological Doctrines: Conceptions of Nature and Methods Used for Its Study by the Ikhwan Al-Safa, Al-Biruni, and Ibn Sina'', State University of New York Press

The State University of New York Press (more commonly referred to as the SUNY Press) is a university press affiliated with the State University of New York system. The press, which was founded in 1966, is located in Albany, New York and publishe ...

* 1st edition 1964, 2nd edition 1993.

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Further reading

* {{Authority control Islam and science Islamic cosmology