Span of control

online

/ref>

History

The Confederacy was established by the Montgomery Convention in February 1861 by seven states (

The Confederacy was established by the Montgomery Convention in February 1861 by seven states (A revolution in disunion

According to historian Avery O. Craven in 1950, the Confederate States of America nation, as a state power, was created by secessionists in Southern slave states, who believed that the federal government was making them second-class citizens.Craven, Avery O., ''The Growth of Southern Nationalism. 1848–1861'' (1953). p. 350 They judged the agents of change to be abolitionists and anti-slavery elements in theCauses of secession

The immediate catalyst for secession was the victory of the Republican Party and the election of Abraham Lincoln as president in the 1860 elections. American Civil War historian James M. McPherson suggested that, for Southerners, the most ominous feature of the Republican victories in the congressional and presidential elections of 1860 was the magnitude of those victories: Republicans captured over 60 percent of the Northern vote and three-fourths of its Congressional delegations. The Southern press said that such Republicans represented the anti-slavery portion of the North, "a party founded on the single sentiment ... of hatred of African slavery", and now the controlling power in national affairs. The "Black Republican party" could overwhelm conservative Yankees. ''The New Orleans Delta'' said of the Republicans, "It is in fact, essentially, a revolutionary party" to overthrow slavery. By 1860, sectional disagreements between North and South concerned primarily the maintenance or expansion of Four of the seceding states, the

Four of the seceding states, the Secessionists and conventions

The pro-slavery "Attempts to thwart secession

In the antebellum months, the Corwin Amendment was an unsuccessful attempt by theInauguration and response

The first secession state conventions from the Deep South sent representatives to meet at the Montgomery Convention in Montgomery, Alabama, on February 4, 1861. There the fundamental documents of government were promulgated, a provisional government was established, and a representative Congress met for the Confederate States of America.Freehling, p. 503

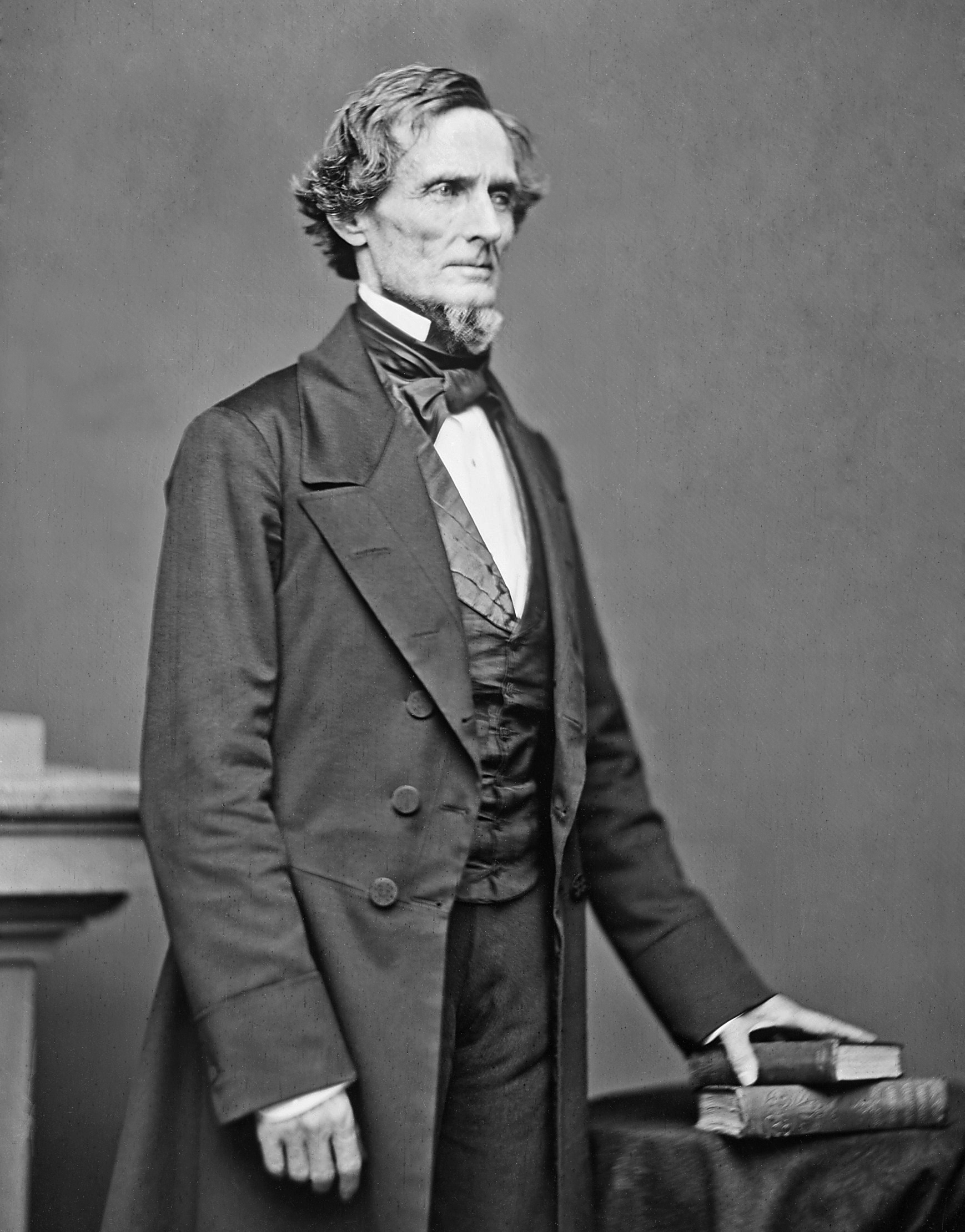

The new 'provisional' Confederate President Jefferson Davis issued a call for 100,000 men from the various states' militias to defend the newly formed Confederacy. All Federal property was seized, along with gold bullion and coining dies at the U.S. mints in

The first secession state conventions from the Deep South sent representatives to meet at the Montgomery Convention in Montgomery, Alabama, on February 4, 1861. There the fundamental documents of government were promulgated, a provisional government was established, and a representative Congress met for the Confederate States of America.Freehling, p. 503

The new 'provisional' Confederate President Jefferson Davis issued a call for 100,000 men from the various states' militias to defend the newly formed Confederacy. All Federal property was seized, along with gold bullion and coining dies at the U.S. mints in Secession

Secessionists argued that the United States Constitution was a contract among sovereign states that could be abandoned at any time without consultation and that each state had a right to secede. After intense debates and statewide votes, sevenStates

Initially, some secessionists may have hoped for a peaceful departure. Moderates in the Confederate Constitutional Convention included a provision against importation of slaves from Africa to appeal to the Upper South. Non-slave states might join, but the radicals secured a two-thirds requirement in both houses of Congress to accept them. Seven states declared their secession from the United States before Lincoln took office on March 4, 1861. After the Confederate attack onTerritories

Citizens at Mesilla and

Citizens at Mesilla and Capitals

Southern Unionism

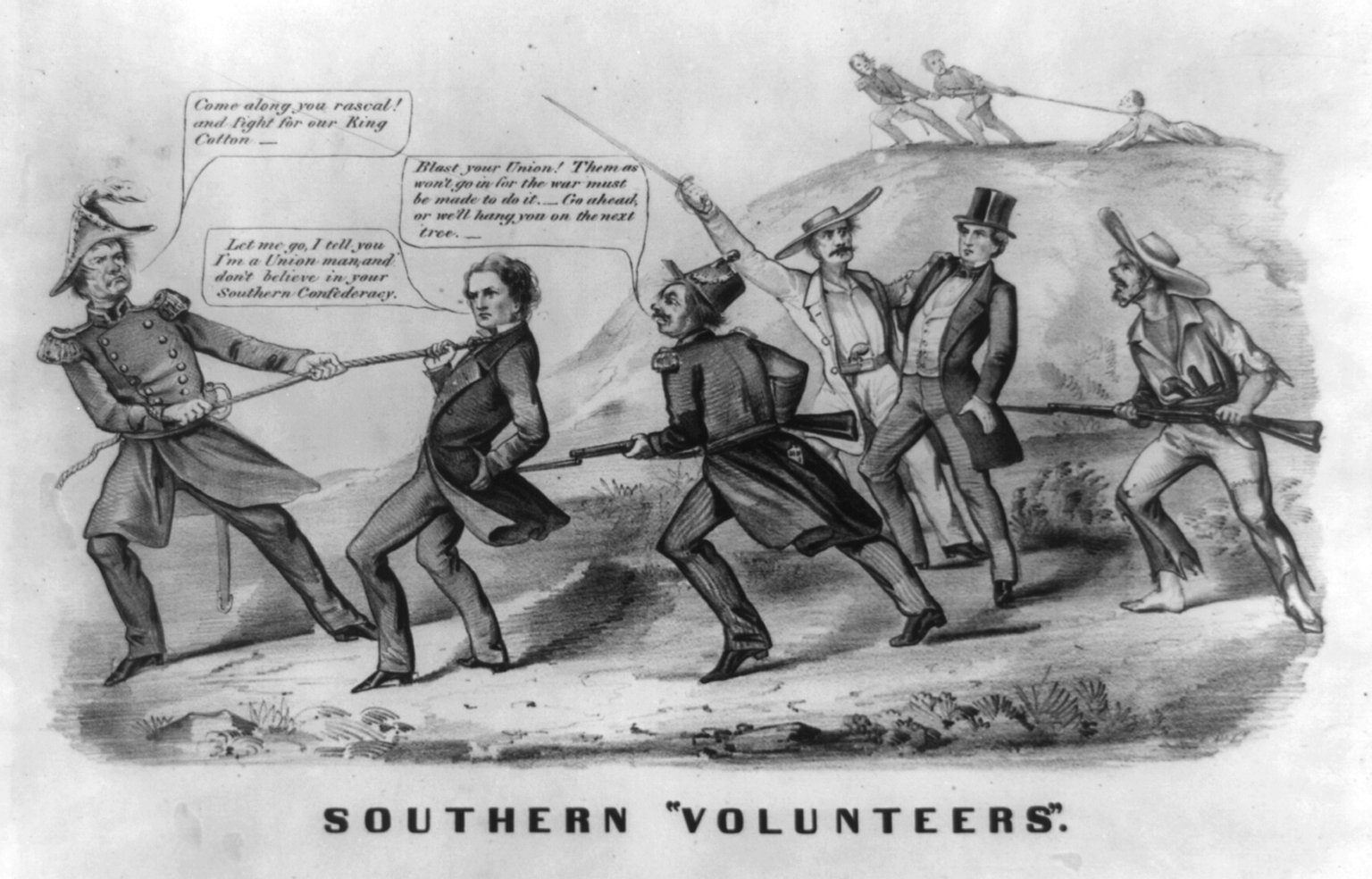

Unionism—opposition to the Confederacy—was widespread in the mountain regions of

Unionism—opposition to the Confederacy—was widespread in the mountain regions of Diplomacy

United States, a foreign power

During the four years of its existence under trial by war, the Confederate States of America asserted its independence and appointed dozens of diplomatic agents abroad. None were ever officially recognized by a foreign government. The United States government regarded the Southern states as being in rebellion or insurrection and so refused any formal recognition of their status. Even beforeInternational diplomacy

Once war with the United States began, the Confederacy pinned its hopes for survival on military intervention by Great Britain and/or=Cuba and Brazil

= The Confederacy's biggest foreign policy successes were with Cuba and Brazil. Militarily this meant little during the war. Brazil represented the "peoples most identical to us in Institutions", in which slavery remained legal until the 1880s. Cuba was a Spanish colony and the Captain–General of Cuba declared in writing that Confederate ships were welcome, and would be protected in Cuban ports. They were also welcome in Brazilian ports; slavery was legal throughout Brazil, and the abolitionist movement was small. After the end of the war, Brazil was the primary destination of those Southerners who wanted to continue living in a slave society, where, as one immigrant remarked, slaves were cheap (see Confederados). Historians speculate that if the Confederacy had achieved independence, it probably would have tried to acquire Cuba as a base of expansion.Confederacy at war

Motivations of soldiers

Most soldiers who joined Confederate national or state military units joined voluntarily. Perman (2010) says historians are of two minds on why millions of soldiers seemed so eager to fight, suffer and die over four years:Military strategy

Civil War historian E. Merton Coulter wrote that for those who would secure its independence, "The Confederacy was unfortunate in its failure to work out a general strategy for the whole war". Aggressive strategy called for offensive force concentration. Defensive strategy sought dispersal to meet demands of locally minded governors. The controlling philosophy evolved into a combination "dispersal with a defensive concentration around Richmond". The Davis administration considered the war purely defensive, a "simple demand that the people of the United States would cease to war upon us". Historian James M. McPherson is a critic of Lee's offensive strategy: "Lee pursued a faulty military strategy that ensured Confederate defeat". As the Confederate government lost control of territory in campaign after campaign, it was said that "the vast size of the Confederacy would make its conquest impossible". The enemy would be struck down by the same elements which so often debilitated or destroyed visitors and transplants in the South. Heat exhaustion, sunstroke, endemic diseases such as malaria and typhoid would match the destructive effectiveness of the Moscow winter on the French invasion of Russia, invading armies of Napoleon.Armed forces

The military armed forces of the Confederacy comprised three branches: Confederate States Army, Army, Confederate States Navy, Navy and Confederate States Marine Corps, Marine Corps. The Confederate military leadership included many veterans from the United States Army and United States Navy who had resigned their Federal commissions and were appointed to senior positions. Many had served in the Mexican–American War (including Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis), but some such as Leonidas Polk (who graduated from United States Military Academy, West Point but did not serve in the Army) had little or no experience.=Raising troops

= The immediate onset of war meant that it was fought by the "Provisional" or "Volunteer Army". State governors resisted concentrating a national effort. Several wanted a strong state army for self-defense. Others feared large "Provisional" armies answering only to Davis. When filling the Confederate government's call for 100,000 men, another 200,000 were turned away by accepting only those enlisted "for the duration" or twelve-month volunteers who brought their own arms or horses.

It was important to raise troops; it was just as important to provide capable officers to command them. With few exceptions the Confederacy secured excellent general officers. Efficiency in the lower officers was "greater than could have been reasonably expected". As with the Federals, political appointees could be indifferent. Otherwise, the officer corps was governor-appointed or elected by unit enlisted. Promotion to fill vacancies was made internally regardless of merit, even if better officers were immediately available.

Anticipating the need for more "duration" men, in January 1862 Congress provided for company level recruiters to return home for two months, but their efforts met little success on the heels of Confederate battlefield defeats in February. Congress allowed for Davis to require numbers of recruits from each governor to supply the volunteer shortfall. States responded by passing their own draft laws.

The veteran Confederate army of early 1862 was mostly twelve-month volunteers with terms about to expire. Enlisted reorganization elections disintegrated the army for two months. Officers pleaded with the ranks to re-enlist, but a majority did not. Those remaining elected majors and colonels whose performance led to officer review boards in October. The boards caused a "rapid and widespread" thinning out of 1,700 incompetent officers. Troops thereafter would elect only second lieutenants.

In early 1862, the popular press suggested the Confederacy required a million men under arms. But veteran soldiers were not re-enlisting, and earlier secessionist volunteers did not reappear to serve in war. One Macon, Georgia, newspaper asked how two million brave fighting men of the South were about to be overcome by four million northerners who were said to be cowards.

The immediate onset of war meant that it was fought by the "Provisional" or "Volunteer Army". State governors resisted concentrating a national effort. Several wanted a strong state army for self-defense. Others feared large "Provisional" armies answering only to Davis. When filling the Confederate government's call for 100,000 men, another 200,000 were turned away by accepting only those enlisted "for the duration" or twelve-month volunteers who brought their own arms or horses.

It was important to raise troops; it was just as important to provide capable officers to command them. With few exceptions the Confederacy secured excellent general officers. Efficiency in the lower officers was "greater than could have been reasonably expected". As with the Federals, political appointees could be indifferent. Otherwise, the officer corps was governor-appointed or elected by unit enlisted. Promotion to fill vacancies was made internally regardless of merit, even if better officers were immediately available.

Anticipating the need for more "duration" men, in January 1862 Congress provided for company level recruiters to return home for two months, but their efforts met little success on the heels of Confederate battlefield defeats in February. Congress allowed for Davis to require numbers of recruits from each governor to supply the volunteer shortfall. States responded by passing their own draft laws.

The veteran Confederate army of early 1862 was mostly twelve-month volunteers with terms about to expire. Enlisted reorganization elections disintegrated the army for two months. Officers pleaded with the ranks to re-enlist, but a majority did not. Those remaining elected majors and colonels whose performance led to officer review boards in October. The boards caused a "rapid and widespread" thinning out of 1,700 incompetent officers. Troops thereafter would elect only second lieutenants.

In early 1862, the popular press suggested the Confederacy required a million men under arms. But veteran soldiers were not re-enlisting, and earlier secessionist volunteers did not reappear to serve in war. One Macon, Georgia, newspaper asked how two million brave fighting men of the South were about to be overcome by four million northerners who were said to be cowards.

=Conscription

= The Confederacy passed the first American law of national conscription on April 16, 1862. The white males of the Confederate States from 18 to 35 were declared members of the Confederate army for three years, and all men then enlisted were extended to a three-year term. They would serve only in units and under officers of their state. Those under 18 and over 35 could substitute for conscripts, in September those from 35 to 45 became conscripts. The cry of "rich man's war and a poor man's fight" led Congress to abolish the substitute system altogether in December 1863. All principals benefiting earlier were made eligible for service. By February 1864, the age bracket was made 17 to 50, those under eighteen and over forty-five to be limited to in-state duty.

Confederate conscription was not universal; it was a selective service. The First Conscription Act of April 1862 exempted occupations related to transportation, communication, industry, ministers, teaching and physical fitness. The Second Conscription Act of October 1862 expanded exemptions in industry, agriculture and conscientious objection. Exemption fraud proliferated in medical examinations, army furloughs, churches, schools, apothecaries and newspapers.

Rich men's sons were appointed to the socially outcast "overseer" occupation, but the measure was received in the country with "universal odium". The legislative vehicle was the controversial Twenty Negro Law that specifically exempted one white overseer or owner for every plantation with at least 20 slaves. Backpedaling six months later, Congress provided overseers under 45 could be exempted only if they held the occupation before the first Conscription Act. The number of officials under state exemptions appointed by state Governor patronage expanded significantly. By law, substitutes could not be subject to conscription, but instead of adding to Confederate manpower, unit officers in the field reported that over-50 and under-17-year-old substitutes made up to 90% of the desertions.

The Confederacy passed the first American law of national conscription on April 16, 1862. The white males of the Confederate States from 18 to 35 were declared members of the Confederate army for three years, and all men then enlisted were extended to a three-year term. They would serve only in units and under officers of their state. Those under 18 and over 35 could substitute for conscripts, in September those from 35 to 45 became conscripts. The cry of "rich man's war and a poor man's fight" led Congress to abolish the substitute system altogether in December 1863. All principals benefiting earlier were made eligible for service. By February 1864, the age bracket was made 17 to 50, those under eighteen and over forty-five to be limited to in-state duty.

Confederate conscription was not universal; it was a selective service. The First Conscription Act of April 1862 exempted occupations related to transportation, communication, industry, ministers, teaching and physical fitness. The Second Conscription Act of October 1862 expanded exemptions in industry, agriculture and conscientious objection. Exemption fraud proliferated in medical examinations, army furloughs, churches, schools, apothecaries and newspapers.

Rich men's sons were appointed to the socially outcast "overseer" occupation, but the measure was received in the country with "universal odium". The legislative vehicle was the controversial Twenty Negro Law that specifically exempted one white overseer or owner for every plantation with at least 20 slaves. Backpedaling six months later, Congress provided overseers under 45 could be exempted only if they held the occupation before the first Conscription Act. The number of officials under state exemptions appointed by state Governor patronage expanded significantly. By law, substitutes could not be subject to conscription, but instead of adding to Confederate manpower, unit officers in the field reported that over-50 and under-17-year-old substitutes made up to 90% of the desertions.

Victories: 1861

The American Civil War broke out in April 1861 with a Confederate victory at the Battle of Fort Sumter in(bottom of page); Department of War details to States (top). This emboldened secessionists in Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee and North Carolina to secede rather than provide troops to march into neighboring Southern states. In May, Federal troops crossed into Confederate territory along the entire border from the Chesapeake Bay to New Mexico. The first battles were Confederate victories at Big Bethel (Battle of Big Bethel, Bethel Church, Virginia), First Bull Run (First Battle of Bull Run, First Manassas) in Virginia July and in August, Wilson's Creek (Battle of Wilson's Creek, Oak Hills) in Missouri. At all three, Confederate forces could not follow up their victory due to inadequate supply and shortages of fresh troops to exploit their successes. Following each battle, Federals maintained a military presence and occupied Washington, DC; Fort Monroe, Virginia; and Springfield, Missouri. Both North and South began training up armies for major fighting the next year. Union General George B. McClellan's forces gained possession of much of northwestern Virginia in mid-1861, concentrating on towns and roads; the interior was too large to control and became the center of guerrilla activity. General

Incursions: 1862

The victories of 1861 were followed by a series of defeats east and west in early 1862. To restore the Union by military force, the Federal strategy was to (1) secure the Mississippi River, (2) seize or close Confederate ports, and (3) march on Richmond. To secure independence, the Confederate intent was to (1) repel the invader on all fronts, costing him blood and treasure, and (2) carry the war into the North by two offensives in time to affect the mid-term elections. Much of northwestern Virginia was under Federal control. In February and March, most of Missouri and Kentucky were Union "occupied, consolidated, and used as staging areas for advances further South". Following the repulse of Confederate counter-attack at the Battle of Shiloh, Tennessee, permanent Federal occupation expanded west, south and east. Confederate forces repositioned south along the Mississippi River to Memphis, Tennessee, where at the naval Battle of Memphis, its River Defense Fleet was sunk. Confederates withdrew from northern Mississippi and northern Alabama. Battle of New Orleans, New Orleans was captured April 29 by a combined Army-Navy force under U.S. Admiral David Farragut, and the Confederacy lost control of the mouth of the Mississippi River. It had to concede extensive agricultural resources that had supported the Union's sea-supplied logistics base.Martis, ''Historical Atlas'', p. 28. Although Confederates had suffered major reverses everywhere, as of the end of April the Confederacy still controlled territory holding 72% of its population.Martis, ''Historical Atlas'', p. 27. Federal occupation expanded into northern Virginia, and their control of the Mississippi extended south to Nashville, Tennessee. Federal forces disrupted Missouri and Arkansas; they had broken through in western Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee and Louisiana. Along the Confederacy's shores, Union forces had closed ports and made garrisoned lodgments on every coastal Confederate state except Alabama and Texas. Although scholars sometimes assess the Union blockade as ineffectual under international law until the last few months of the war, from the first months it disrupted Confederate privateers, making it "almost impossible to bring their prizes into Confederate ports". British firms developed small fleets of Blockade runners of the American Civil War, blockade running companies, such as George Trenholm, John Fraser and Company and S. Isaac, Campbell & Company while the Ordnance Department secured its own blockade runners for dedicated munitions cargoes. During the Civil War fleets of Ironclad warship, armored warships were deployed for the first time in sustained blockades at sea. After some success against the Union blockade, in March the ironclad CSS Virginia, CSS ''Virginia'' was forced into port and burned by Confederates at their retreat. Despite several attempts mounted from their port cities, CSA naval forces were unable to break the Union blockade. Attempts were made by Commodore Josiah Tattnall III's ironclads from Savannah in 1862 with the USS Atlanta (1861), CSS ''Atlanta''. Secretary of the Navy Stephen Mallory placed his hopes in a European-built ironclad fleet, but they were never realized. On the other hand, four new English-built commerce raiders served the Confederacy, and several fast blockade runners were sold in Confederate ports. They were converted into commerce-raiding cruisers, and manned by their British crews. In the east, Union forces could not close on Richmond. General McClellan landed his army on the Peninsula Campaign, Lower Peninsula of Virginia. Lee subsequently ended that threat from the east, then Union General John Pope attacked overland from the north only to be repulsed at Second Bull Run (Second Battle of Bull Run, Second Manassas). Lee's strike north was turned back at Antietam MD, then Union Ambrose Burnside, Major General Ambrose Burnside's offensive was disastrously ended at Battle of Fredericksburg, Fredericksburg VA in December. Both armies then turned to winter quarters to recruit and train for the coming spring. In an attempt to seize the initiative, reprove, protect farms in mid-growing season and influence U.S. Congressional elections, two major Confederate incursions into Union territory had been launched in August and September 1862. Both Braxton Bragg's invasion of Kentucky and Battle of Antietam, Lee's invasion of Maryland were decisively repulsed, leaving Confederates in control of but 63% of its population. Civil War scholar Allan Nevins argues that 1862 was the strategic Ordinary high water mark, high-water mark of the Confederacy. The failures of the two invasions were attributed to the same irrecoverable shortcomings: lack of manpower at the front, lack of supplies including serviceable shoes, and exhaustion after long marches without adequate food. Also in September Confederate General William W. Loring pushed Federal forces from Charleston, West Virginia, Charleston, Virginia, and the Kanawha Valley in western Virginia, but lacking reinforcements Loring abandoned his position and by November the region was back in Federal control.Anaconda: 1863–64

The failed MiddleCollapse: 1865

The first three months of 1865 saw the Federal Carolinas Campaign, devastating a wide swath of the remaining Confederate heartland. The "breadbasket of the Confederacy" in the Great Valley of Virginia was occupied by Philip Sheridan. The Union Blockade captured Fort Fisher in North Carolina, and Sherman finally Second Battle of Charleston Harbor, took Charleston, South Carolina, by land attack. The Confederacy controlled no ports, harbors or navigable rivers. Railroads were captured or had ceased operating. Its major food-producing regions had been war-ravaged or occupied. Its administration survived in only three pockets of territory holding only one-third of its population. Its armies were defeated or disbanding. At the February 1865 Hampton Roads Conference with Lincoln, senior Confederate officials rejected his invitation to restore the Union with compensation for emancipated slaves. The three pockets of unoccupied Confederacy were southern Virginia – North Carolina, central Alabama – Florida, and Texas, the latter two areas less from any notion of resistance than from the disinterest of Federal forces to occupy them. The Davis policy was independence or nothing, while Lee's army was wracked by disease and desertion, barely holding the trenches defending Jefferson Davis' capital. The Confederacy's last remaining blockade-running port, Wilmington, North Carolina, Battle of Wilmington, was lost. When the Union broke through Lee's lines at Petersburg, Richmond in the American Civil War, Richmond fell immediately. Lee surrendered a remnant of 50,000 from thePostwar history

Amnesty and treason issue

When the war ended over 14,000 Confederates petitioned President Johnson for a pardon; he was generous in giving them out. He issued a general amnesty to all Confederate participants in the "late Civil War" in 1868. Congress passed additional Amnesty Acts in May 1866 with restrictions on office holding, and the Amnesty Act in May 1872 lifting those restrictions. There was a great deal of discussion in 1865 about bringing treason trials, especially against Jefferson Davis. There was no consensus in President Johnson's cabinet, and no one was charged with treason. An acquittal of Davis would have been humiliating for the government. Davis was indicted for treason but never tried; he was released from prison on bail in May 1867. The amnesty of December 25, 1868, by President Johnson eliminated any possibility of Jefferson Davis (or anyone else associated with the Confederacy) standing trial for treason. Henry Wirz, the commandant of a notorious prisoner-of-war camp near Andersonville, Georgia, was tried and convicted by a military court, and executed on November 10, 1865. The charges against him involved conspiracy and cruelty, not treason. The U.S. government began a decade-long process known as Reconstruction Era, Reconstruction which attempted to resolve the political and constitutional issues of the Civil War. The priorities were: to guarantee that Confederate nationalism and slavery were ended, to ratify and enforce the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, Thirteenth Amendment which outlawed slavery; the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, Fourteenth which guaranteed dual U.S. and state citizenship to all native-born residents, regardless of race; and the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, Fifteenth, which made it illegal to deny the right to vote because of race. By 1877, the Compromise of 1877 ended Reconstruction in the former Confederate states. Federal troops were withdrawn from the South, where conservative white Democrats had already regained political control of state governments, often through extreme violence and fraud to suppress black voting. The prewar South had many rich areas; the war left the entire region economically devastated by military action, ruined infrastructure, and exhausted resources. Still dependent on an agricultural economy and resisting investment in infrastructure, it remained dominated by the planter elite into the next century. Confederate veterans had been temporarily disenfranchised by Reconstruction policy, and Democrat-dominated legislatures passed new constitutions and amendments Disfranchisement after Reconstruction era, to now exclude most blacks and many poor whites. This exclusion and a weakened Republican Party remained the norm until the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The Solid South of the early 20th century did not achieve national levels of prosperity until long after World War II.''Texas v. White''

In ''Texas v. White'', the United States Supreme Court ruled – by a 5–3 majority – that Texas had remained a state ever since it first joined the Union, despite claims that it joined the Confederate States of America. In this case, the court held that the Constitution did not permit United States states, a state to unilaterally secede from the United States. Further, that the ordinances of secession, and all the acts of the legislatures within seceding states intended to give effect to such ordinances, were "absolutely Void (law), null", under the Constitution. This case settled the law that applied to all questions regarding state legislation during the war. Furthermore, it decided one of the "central constitutional questions" of the Civil War: The Union is perpetual and indestructible, as a matter of constitutional law. In declaring that no state could leave the Union, "except through revolution or through consent of the States", it was "explicitly repudiating the position of the Confederate states that the United States was a voluntary compact between sovereign states".Theories regarding the Confederacy's demise

"Died of states' rights"

Historian Frank Lawrence Owsley argued that the Confederacy "died of states' rights". The central government was denied requisitioned soldiers and money by governors and state legislatures because they feared that Richmond would encroach on the rights of the states. Georgia's governor Joseph E. Brown, Joseph Brown warned of a secret conspiracy by Jefferson Davis to destroy states' rights and individual liberty. The first conscription act in North America, authorizing Davis to draft soldiers, was said to be the "essence of military despotism"."Died of Davis"

The enemies of President Davis proposed that the Confederacy "died of Davis". He was unfavorably compared to George Washington by critics such as Edward Alfred Pollard, editor of the most influential newspaper in the Confederacy, the ''Richmond Examiner, Richmond (Virginia) Examiner''. E. Merton Coulter summarizes, "The American Revolution had its Washington; the Southern Revolution had its Davis ... one succeeded and the other failed." Beyond the early honeymoon period, Davis was never popular. He unwittingly caused much internal dissension from early on. His ill health and temporary bouts of blindness disabled him for days at a time.Coulter, ''The Confederate States of America'', pp. 105–106 Coulter, viewed by today's historians as a Confederate apologist,Fred A. Bailey, "E. Merton Coulter," in ''Reading Southern History: Essays on Interpreters and Interpretations'', ed. Glenn Feldman (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001, p. 46). Eric Foner, ''Freedom's Lawmakers: A Directory Of Black Officeholders During Reconstruction'', New York: Oxford University Press, 1993; Revised, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1996, p. xiiFoner, ''Freedom's Lawmakers'', p. xiiEric Foner, ''Black Legislators'', pp. 119–20, 180 says Davis was heroic and his will was indomitable. But his "tenacity, determination, and will power" stirred up lasting opposition from enemies that Davis could not shake. He failed to overcome "petty leaders of the states" who made the term "Confederacy" into a label for tyranny and oppression, preventing the "Flags of the Confederate States of America#First flag: the "Stars and Bars" (1861–1863), Stars and Bars" from becoming a symbol of larger patriotic service and sacrifice. Instead of campaigning to develop nationalism and gain support for his administration, he rarely courted public opinion, assuming an aloofness, "almost like an John Adams, Adams". Escott argues that Davis was unable to mobilize Confederate nationalism in support of his government effectively, and especially failed to appeal to the small farmers who comprised the bulk of the population. In addition to the problems caused by states rights, Escott also emphasizes that the widespread opposition to any strong central government combined with the vast difference in wealth between the slave-owning class and the small farmers created insolvable dilemmas when the Confederate survival presupposed a strong central government backed by a united populace. The prewar claim that white solidarity was necessary to provide a unified Southern voice in Washington no longer held. Davis failed to build a network of supporters who would speak up when he came under criticism, and he repeatedly alienated governors and other state-based leaders by demanding centralized control of the war effort. According to Coulter, Davis was not an efficient administrator as he attended to too many details, protected his friends after their failures were obvious, and spent too much time on military affairs versus his civic responsibilities. Coulter concludes he was not the ideal leader for the Southern Revolution, but he showed "fewer weaknesses than any other" contemporary character available for the role.Government and politics

Political divisions

Constitution

The Southern leaders met in Montgomery, Alabama, to write their constitution. Much of the Confederate States Constitution replicated the United States Constitution verbatim, but it contained several explicit protections of the institution of slavery including provisions for the recognition and protection of slavery in any territory of the Confederacy. It maintained the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves, ban on international slave-trading, though it made the ban's application explicit to "Negroes of the African race" in contrast to the U.S. Constitution's reference to "such Persons as any of the States now existing shall think proper to admit". It protected the Slavery in the United States#Internal slave trade, existing internal trade of slaves among slaveholding states. In certain areas, the Confederate Constitution gave greater powers to the states (or curtailed the powers of the central government more) than the U.S. Constitution of the time did, but in other areas, the states lost rights they had under the U.S. Constitution. Although the Confederate Constitution, like the U.S. Constitution, contained a commerce clause, the Confederate version prohibited the central government from using revenues collected in one state for funding internal improvements in another state. The Confederate Constitution's equivalent to the U.S. Constitution's General Welfare clause, general welfare clause prohibited protective tariffs (but allowed tariffs for providing domestic revenue), and spoke of "carry[ing] on the Government of the Confederate States" rather than providing for the "general welfare". State legislatures had the power to impeachment, impeach officials of the Confederate government in some cases. On the other hand, the Confederate Constitution contained a Necessary and Proper Clause and a Supremacy Clause that essentially duplicated the respective clauses of the U.S. Constitution. The Confederate Constitution also incorporated each of the 12 amendments to the U.S. Constitution that had been ratified up to that point. The Confederate Constitution did not specifically include a provision allowing states to secede; the Preamble spoke of each state "acting in its sovereign and independent character" but also of the formation of a "permanent federal government". During the debates on drafting the Confederate Constitution, one proposal would have allowed states to secede from the Confederacy. The proposal was tabled with only the South Carolina delegates voting in favor of considering the motion. The Confederate Constitution also explicitly denied States the power to bar slaveholders from other parts of the Confederacy from bringing their slaves into any state of the Confederacy or to interfere with the property rights of slave owners traveling between different parts of the Confederacy. In contrast with the secular language of the United States Constitution, the Confederate Constitution overtly asked God's blessing ("... invoking the favor and guidance of Almighty God ..."). Some historians have referred to the Confederacy as a form of Herrenvolk democracy.Executive

The Montgomery Convention to establish the Confederacy and its executive met on February 4, 1861. Each state as a sovereignty had one vote, with the same delegation size as it held in the U.S. Congress, and generally 41 to 50 members attended. Offices were "provisional", limited to a term not to exceed one year. One name was placed in nomination for president, one for vice president. Both were elected unanimously, 6–0. Jefferson Davis was elected provisional president. His U.S. Senate resignation speech greatly impressed with its clear rationale for secession and his pleading for a peaceful departure from the Union to independence. Although he had made it known that he wanted to be commander-in-chief of the Confederate armies, when elected, he assumed the office of Provisional President. Three candidates for provisional Vice President were under consideration the night before the February 9 election. All were from Georgia, and the various delegations meeting in different places determined two would not do, so Alexander H. Stephens was elected unanimously provisional Vice President, though with some privately held reservations. Stephens was inaugurated February 11, Davis February 18.

Davis and Stephens were elected president and vice president, unopposed Confederate States presidential election, 1861, on November 6, 1861. They were inaugurated on February 22, 1862.

Coulter stated, "No president of the U.S. ever had a more difficult task." Washington was inaugurated in peacetime. Lincoln inherited an established government of long standing. The creation of the Confederacy was accomplished by men who saw themselves as fundamentally conservative. Although they referred to their "Revolution", it was in their eyes more a counter-revolution against changes away from their understanding of U.S. founding documents. In Davis' inauguration speech, he explained the Confederacy was not a French-like revolution, but a transfer of rule. The Montgomery Convention had assumed all the laws of the United States until superseded by the Confederate Congress.

The Permanent Constitution provided for a President of the Confederate States of America, elected to serve a six-year term but without the possibility of re-election. Unlike the United States Constitution, the Confederate Constitution gave the president the ability to subject a bill to a line item veto, a power also held by some state governors.

The Confederate Congress could overturn either the general or the line item vetoes with the same two-thirds votes required in the Congress of the United States, U.S. Congress. In addition, appropriations not specifically requested by the executive branch required passage by a two-thirds vote in both houses of Congress. The only person to serve as president was Jefferson Davis, as the Confederacy was defeated before the completion of his term.

Jefferson Davis was elected provisional president. His U.S. Senate resignation speech greatly impressed with its clear rationale for secession and his pleading for a peaceful departure from the Union to independence. Although he had made it known that he wanted to be commander-in-chief of the Confederate armies, when elected, he assumed the office of Provisional President. Three candidates for provisional Vice President were under consideration the night before the February 9 election. All were from Georgia, and the various delegations meeting in different places determined two would not do, so Alexander H. Stephens was elected unanimously provisional Vice President, though with some privately held reservations. Stephens was inaugurated February 11, Davis February 18.

Davis and Stephens were elected president and vice president, unopposed Confederate States presidential election, 1861, on November 6, 1861. They were inaugurated on February 22, 1862.

Coulter stated, "No president of the U.S. ever had a more difficult task." Washington was inaugurated in peacetime. Lincoln inherited an established government of long standing. The creation of the Confederacy was accomplished by men who saw themselves as fundamentally conservative. Although they referred to their "Revolution", it was in their eyes more a counter-revolution against changes away from their understanding of U.S. founding documents. In Davis' inauguration speech, he explained the Confederacy was not a French-like revolution, but a transfer of rule. The Montgomery Convention had assumed all the laws of the United States until superseded by the Confederate Congress.

The Permanent Constitution provided for a President of the Confederate States of America, elected to serve a six-year term but without the possibility of re-election. Unlike the United States Constitution, the Confederate Constitution gave the president the ability to subject a bill to a line item veto, a power also held by some state governors.

The Confederate Congress could overturn either the general or the line item vetoes with the same two-thirds votes required in the Congress of the United States, U.S. Congress. In addition, appropriations not specifically requested by the executive branch required passage by a two-thirds vote in both houses of Congress. The only person to serve as president was Jefferson Davis, as the Confederacy was defeated before the completion of his term.

=Administration and cabinet

=

Legislative

The only two "formal, national, functioning, civilian administrative bodies" in the Civil War South were the Jefferson Davis administration and the Confederate Congresses. The Confederacy was begun by the Provisional Congress in Convention at Montgomery, Alabama on February 28, 1861. The Provisional Confederate Congress was a unicameral assembly, each state received one vote. The Permanent Confederate Congress was elected and began its first session February 18, 1862. The Permanent Congress for the Confederacy followed the United States forms with a bicameral legislature. The Senate had two per state, twenty-six Senators. The House numbered 106 representatives apportioned by free and slave populations within each state. Two Congresses sat in six sessions until March 18, 1865. The political influences of the civilian, soldier vote and appointed representatives reflected divisions of political geography of a diverse South. These in turn changed over time relative to Union occupation and disruption, the war impact on the local economy, and the course of the war. Without political parties, key candidate identification related to adopting secession before or after Lincoln's call for volunteers to retake Federal property. Previous party affiliation played a part in voter selection, predominantly secessionist Democrat or unionist Whig. The absence of political parties made individual roll call voting all the more important, as the Confederate "freedom of roll-call voting [was] unprecedented in American legislative history." Key issues throughout the life of the Confederacy related to (1) suspension of habeas corpus, (2) military concerns such as control of state militia, conscription and exemption, (3) economic and fiscal policy including impressment of slaves, goods and scorched earth, and (4) support of the Jefferson Davis administration in its foreign affairs and negotiating peace. ;Provisional Congress For the first year, the unicameral Provisional Confederate Congress functioned as the Confederacy's legislative branch. ;President of the Provisional Congress * Howell Cobb, Howell Cobb, Sr. of Georgia, February 4, 1861 – February 17, 1862 ;Presidents pro tempore of the Provisional Congress * Robert Woodward Barnwell of South Carolina, February 4, 1861 * Thomas Stanhope Bocock of Virginia, December 10–21, 1861 and January 7–8, 1862 * Josiah Abigail Patterson Campbell of Mississippi, December 23–24, 1861 and January 6, 1862 ;Sessions of the Confederate Congress * Provisional Congress of the Confederate States, Provisional Congress * 1st Confederate States Congress, 1st Congress * 2nd Confederate States Congress, 2nd Congress ;Tribal Representatives to Confederate Congress *Judicial

Florida District HenryRootesJackson.jpg, Henry R. Jackson

Georgia District NC-Congress-AsaBiggs.jpg, Asa Biggs

North Carolina District Andrew Gordon Magrath.jpg, Andrew Gordon Magrath, Andrew Magrath

South Carolina District

Post Office

Postmaster General J Davis 1861-5c.jpg, Jefferson Davis, 5 cent

Postage stamps and postal history of the Confederate States#Confederate postage, The first stamp, 1861 Csa jackson 1862-2c.jpg, Andrew Jackson

2 cent, 1862 George-washington-CSA-stamp.jpg, George Washington

20 cent, 1863

Civil liberties

The Confederacy actively used the army to arrest people suspected of loyalty to the United States. Historian Mark E. Neely, Jr., Mark Neely found 4,108 names of men arrested and estimated a much larger total. The Confederacy arrested pro-Union civilians in the South at about the same rate as the Union arrested pro-Confederate civilians in the North. Neely argues:Economy

Slaves

Across the South, widespread rumors alarmed the whites by predicting the slaves were planning some sort of insurrection. Slave patrol, Patrols were stepped up. The slaves did become increasingly independent, and resistant to punishment, but historians agree there were no insurrections. In the invaded areas, insubordination was more the norm than was loyalty to the old master; Bell I. Wiley, Bell Wiley says, "It was not disloyalty, but the lure of freedom." Many slaves became spies for the North, and large numbers ran away to federal lines. Lincoln'sPolitical economy

Most whites were subsistence farmers who traded their surpluses locally. The plantations of the South, with white ownership and an enslaved labor force, produced substantial wealth from cash crops. It supplied two-thirds of the world's cotton, which was in high demand for textiles, along with tobacco, sugar, and naval stores (such as turpentine). These raw materials were exported to factories in Europe and the Northeast. Planters reinvested their profits in more slaves and fresh land, as cotton and tobacco depleted the soil. There was little manufacturing or mining; shipping was controlled by non-southerners. The plantations that enslaved over three million black people were the principal source of wealth. Most were concentrated in "Black Belt (geological formation), black belt" plantation areas (because few white families in the poor regions owned slaves). For decades, there had been widespread fear of slave revolts. During the war, extra men were assigned to "home guard" patrol duty and governors sought to keep militia units at home for protection. Historian William Barney reports, "no major slave revolts erupted during the Civil War." Nevertheless, slaves took the opportunity to enlarge their sphere of independence, and when union forces were nearby, many ran off to join them. Slave labor was applied in industry in a limited way in the Upper South and in a few port cities. One reason for the regional lag in industrial development was top-heavy income distribution. Mass production requires mass markets, and Economics of slavery, slaves living in small cabins, using self-made tools and outfitted with one suit of work clothes each year of inferior fabric, did not generate consumer demand to sustain local manufactures of any description in the same way as did a mechanized family farm of free labor in the North. The Southern economy was "pre-capitalist" in that slaves were put to work in the largest revenue-producing enterprises, not free labor markets. That labor system as practiced in the American South encompassed paternalism, whether abusive or indulgent, and that meant labor management considerations apart from productivity. Approximately 85% of both the North and South white populations lived on family farms, both regions were predominantly agricultural, and mid-century industry in both was mostly domestic. But the Southern economy was pre-capitalist in its overwhelming reliance on the agriculture of cash crops to produce wealth, while the great majority of farmers fed themselves and supplied a small local market. Southern cities and industries grew faster than ever before, but the thrust of the rest of the country's exponential growth elsewhere was toward urban industrial development along transportation systems of canals and railroads. The South was following the dominant currents of the American economic mainstream, but at a "great distance" as it lagged in the all-weather modes of transportation that brought cheaper, speedier freight shipment and forged new, expanding inter-regional markets. A third count of the pre-capitalist Southern economy relates to the cultural setting. The South and southerners did not adopt a work ethic, nor the habits of thrift that marked the rest of the country. It had access to the tools of capitalism, but it did not adopt its culture. The Southern Cause as a national economy in the Confederacy was grounded in "slavery and race, planters and patricians, plain folk and folk culture, cotton and plantations".National production

The Confederacy started its existence as an agrarian economy with exports, to a world market, of cotton, and, to a lesser extent, tobacco and sugarcane. Local food production included grains, hogs, cattle, and gardens. The cash came from exports but the Southern people spontaneously stopped exports in early 1861 to hasten the impact of "King Cotton", a failed strategy to coerce international support for the Confederacy through its cotton exports. When the blockade was announced, commercial shipping practically ended (the ships could not get insurance), and only a trickle of supplies came via blockade runners. The cutoff of exports was an economic disaster for the South, rendering useless its most valuable properties, its plantations and their enslaved workers. Many planters kept growing cotton, which piled up everywhere, but most turned to food production. All across the region, the lack of repair and maintenance wasted away the physical assets.

The eleven states had produced $155 million in manufactured goods in 1860, chiefly from local grist-mills, and lumber, processed tobacco, cotton goods and naval stores such as turpentine. The main industrial areas were border cities such as Baltimore, Wheeling, Louisville and St. Louis, that were never under Confederate control. The government did set up munitions factories in the Deep South. Combined with captured munitions and those coming via blockade runners, the armies were kept minimally supplied with weapons. The soldiers suffered from reduced rations, lack of medicines, and the growing shortages of uniforms, shoes and boots. Shortages were much worse for civilians, and the prices of necessities steadily rose.

The Confederacy adopted a tariff or tax on imports of 15%, and imposed it on all imports from other countries, including the United States. The tariff mattered little; the Union blockade minimized commercial traffic through the Confederacy's ports, and very few people paid taxes on goods smuggled from the North. The Confederate government in its entire history collected only $3.5 million in tariff revenue. The lack of adequate financial resources led the Confederacy to finance the war through printing money, which led to high inflation. The Confederacy underwent an economic revolution by centralization and standardization, but it was too little too late as its economy was systematically strangled by blockade and raids.

The Confederacy started its existence as an agrarian economy with exports, to a world market, of cotton, and, to a lesser extent, tobacco and sugarcane. Local food production included grains, hogs, cattle, and gardens. The cash came from exports but the Southern people spontaneously stopped exports in early 1861 to hasten the impact of "King Cotton", a failed strategy to coerce international support for the Confederacy through its cotton exports. When the blockade was announced, commercial shipping practically ended (the ships could not get insurance), and only a trickle of supplies came via blockade runners. The cutoff of exports was an economic disaster for the South, rendering useless its most valuable properties, its plantations and their enslaved workers. Many planters kept growing cotton, which piled up everywhere, but most turned to food production. All across the region, the lack of repair and maintenance wasted away the physical assets.

The eleven states had produced $155 million in manufactured goods in 1860, chiefly from local grist-mills, and lumber, processed tobacco, cotton goods and naval stores such as turpentine. The main industrial areas were border cities such as Baltimore, Wheeling, Louisville and St. Louis, that were never under Confederate control. The government did set up munitions factories in the Deep South. Combined with captured munitions and those coming via blockade runners, the armies were kept minimally supplied with weapons. The soldiers suffered from reduced rations, lack of medicines, and the growing shortages of uniforms, shoes and boots. Shortages were much worse for civilians, and the prices of necessities steadily rose.

The Confederacy adopted a tariff or tax on imports of 15%, and imposed it on all imports from other countries, including the United States. The tariff mattered little; the Union blockade minimized commercial traffic through the Confederacy's ports, and very few people paid taxes on goods smuggled from the North. The Confederate government in its entire history collected only $3.5 million in tariff revenue. The lack of adequate financial resources led the Confederacy to finance the war through printing money, which led to high inflation. The Confederacy underwent an economic revolution by centralization and standardization, but it was too little too late as its economy was systematically strangled by blockade and raids.

Transportation systems

In peacetime, the South's extensive and connected systems of navigable rivers and coastal access allowed for cheap and easy transportation of agricultural products. The railroad system in the South had developed as a supplement to the navigable rivers to enhance the all-weather shipment of cash crops to market. Railroads tied plantation areas to the nearest river or seaport and so made supply more dependable, lowered costs and increased profits. In the event of invasion, the vast geography of the Confederacy made logistics difficult for the Union. Wherever Union armies invaded, they assigned many of their soldiers to garrison captured areas and to protect rail lines.

At the onset of the Civil War the South had a rail network disjointed and plagued by changes in track gauge as well as lack of interchange. Locomotives and freight cars had fixed axles and could not use tracks of different gauges (widths). Railroads of different gauges leading to the same city required all freight to be off-loaded onto wagons for transport to the connecting railroad station, where it had to await freight cars and a locomotive#Motive power, locomotive before proceeding. Centers requiring off-loading included Vicksburg, New Orleans, Montgomery, Wilmington and Richmond. In addition, most rail lines led from coastal or river ports to inland cities, with few lateral railroads. Because of this design limitation, the relatively primitive railroads of the Confederacy were unable to overcome the Union naval blockade of the South's crucial intra-coastal and river routes.

The Confederacy had no plan to expand, protect or encourage its railroads. Southerners' refusal to export the cotton crop in 1861 left railroads bereft of their main source of income. Many lines had to lay off employees; many critical skilled technicians and engineers were permanently lost to military service. In the early years of the war the Confederate government had a hands-off approach to the railroads. Only in mid-1863 did the Confederate government initiate a national policy, and it was confined solely to aiding the war effort.Mary Elizabeth Massey. ''Ersatz in the Confederacy'' (1952) p. 128. Railroads came under the ''de facto'' control of the military. In contrast, the U.S. Congress had authorized military administration of Union-controlled railroad and telegraph systems in January 1862, imposed a standard gauge, and built railroads into the South using that gauge. Confederate armies successfully reoccupying territory could not be resupplied directly by rail as they advanced. The C.S. Congress formally authorized military administration of railroads in February 1865.

In the last year before the end of the war, the Confederate railroad system stood permanently on the verge of collapse. There was no new equipment and raids on both sides systematically destroyed key bridges, as well as locomotives and freight cars. Spare parts were cannibalized; feeder lines were torn up to get replacement rails for trunk lines, and rolling stock wore out through heavy use.

In peacetime, the South's extensive and connected systems of navigable rivers and coastal access allowed for cheap and easy transportation of agricultural products. The railroad system in the South had developed as a supplement to the navigable rivers to enhance the all-weather shipment of cash crops to market. Railroads tied plantation areas to the nearest river or seaport and so made supply more dependable, lowered costs and increased profits. In the event of invasion, the vast geography of the Confederacy made logistics difficult for the Union. Wherever Union armies invaded, they assigned many of their soldiers to garrison captured areas and to protect rail lines.

At the onset of the Civil War the South had a rail network disjointed and plagued by changes in track gauge as well as lack of interchange. Locomotives and freight cars had fixed axles and could not use tracks of different gauges (widths). Railroads of different gauges leading to the same city required all freight to be off-loaded onto wagons for transport to the connecting railroad station, where it had to await freight cars and a locomotive#Motive power, locomotive before proceeding. Centers requiring off-loading included Vicksburg, New Orleans, Montgomery, Wilmington and Richmond. In addition, most rail lines led from coastal or river ports to inland cities, with few lateral railroads. Because of this design limitation, the relatively primitive railroads of the Confederacy were unable to overcome the Union naval blockade of the South's crucial intra-coastal and river routes.

The Confederacy had no plan to expand, protect or encourage its railroads. Southerners' refusal to export the cotton crop in 1861 left railroads bereft of their main source of income. Many lines had to lay off employees; many critical skilled technicians and engineers were permanently lost to military service. In the early years of the war the Confederate government had a hands-off approach to the railroads. Only in mid-1863 did the Confederate government initiate a national policy, and it was confined solely to aiding the war effort.Mary Elizabeth Massey. ''Ersatz in the Confederacy'' (1952) p. 128. Railroads came under the ''de facto'' control of the military. In contrast, the U.S. Congress had authorized military administration of Union-controlled railroad and telegraph systems in January 1862, imposed a standard gauge, and built railroads into the South using that gauge. Confederate armies successfully reoccupying territory could not be resupplied directly by rail as they advanced. The C.S. Congress formally authorized military administration of railroads in February 1865.

In the last year before the end of the war, the Confederate railroad system stood permanently on the verge of collapse. There was no new equipment and raids on both sides systematically destroyed key bridges, as well as locomotives and freight cars. Spare parts were cannibalized; feeder lines were torn up to get replacement rails for trunk lines, and rolling stock wore out through heavy use.

Horses and mules

The Confederate army experienced a persistent shortage of horses and mules, and requisitioned them with dubious promissory notes given to local farmers and breeders. Union forces paid in real money and found ready sellers in the South. Both armies needed horses for cavalry and for artillery. Mules pulled the wagons. The supply was undermined by an unprecedented epidemic of glanders, a fatal disease that baffled veterinarians. After 1863 the invading Union forces had a policy of shooting all the local horses and mules that they did not need, in order to keep them out of Confederate hands. The Confederate armies and farmers experienced a growing shortage of horses and mules, which hurt the Southern economy and the war effort. The South lost half of its 2.5 million horses and mules; many farmers ended the war with none left. Army horses were used up by hard work, malnourishment, disease and battle wounds; they had a life expectancy of about seven months.Financial instruments

Both the individual Confederate states and later the Confederate government printed Confederate States of America dollars as paper currency in various denominations, with a total face value of $1.5 billion. Much of it was signed by Treasurer Edward C. Elmore. Inflation became rampant as the paper money depreciated and eventually became worthless. The state governments and some localities printed their own paper money, adding to the runaway inflation. Many bills still exist, although in recent years counterfeit copies have proliferated. The Confederate government initially wanted to finance its war mostly through tariffs on imports, export taxes, and voluntary donations of gold. After the spontaneous imposition of an embargo on cotton sales to Europe in 1861, these sources of revenue dried up and the Confederacy increasingly turned to Government debt, issuing debt and printing money to pay for war expenses. The Confederate States politicians were worried about angering the general population with hard taxes. A tax increase might disillusion many Southerners, so the Confederacy resorted to printing more money. As a result, inflation increased and remained a problem for the southern states throughout the rest of the war. By April 1863, for example, the cost of flour in Richmond had risen to $100 a barrel and housewives were rioting.

The Confederate government took over the three national mints in its territory: the Charlotte Mint in North Carolina, the Dahlonega Mint in Georgia, and the New Orleans Mint in Louisiana. During 1861 all of these facilities produced small amounts of gold coinage, and the latter half dollars as well. Since the mints used the current dies on hand, all appear to be U.S. issues. However, by comparing slight differences in the dies specialists can distinguish 1861-O half dollars that were minted either under the authority of the U.S. government, the State of Louisiana, or finally the Confederate States. Unlike the gold coins, this issue was produced in significant numbers (over 2.5 million) and is inexpensive in lower grades, although fakes have been made for sale to the public. However, before the New Orleans Mint ceased operation in May, 1861, the Confederate government used its own reverse design to strike four half dollars. This made one of the great rarities of American numismatics. A lack of silver and gold precluded further coinage. The Confederacy apparently also experimented with issuing one cent coins, although only 12 were produced by a jeweler in Philadelphia, who was afraid to send them to the South. Like the half dollars, copies were later made as souvenirs.

US coinage was hoarded and did not have any general circulation. U.S. coinage was admitted as legal tender up to $10, as were British sovereigns, Napoléon (coin), French Napoleons and Spanish and Mexican doubloons at a fixed rate of exchange. Confederate money was paper and postage stamps.

The Confederate government initially wanted to finance its war mostly through tariffs on imports, export taxes, and voluntary donations of gold. After the spontaneous imposition of an embargo on cotton sales to Europe in 1861, these sources of revenue dried up and the Confederacy increasingly turned to Government debt, issuing debt and printing money to pay for war expenses. The Confederate States politicians were worried about angering the general population with hard taxes. A tax increase might disillusion many Southerners, so the Confederacy resorted to printing more money. As a result, inflation increased and remained a problem for the southern states throughout the rest of the war. By April 1863, for example, the cost of flour in Richmond had risen to $100 a barrel and housewives were rioting.

The Confederate government took over the three national mints in its territory: the Charlotte Mint in North Carolina, the Dahlonega Mint in Georgia, and the New Orleans Mint in Louisiana. During 1861 all of these facilities produced small amounts of gold coinage, and the latter half dollars as well. Since the mints used the current dies on hand, all appear to be U.S. issues. However, by comparing slight differences in the dies specialists can distinguish 1861-O half dollars that were minted either under the authority of the U.S. government, the State of Louisiana, or finally the Confederate States. Unlike the gold coins, this issue was produced in significant numbers (over 2.5 million) and is inexpensive in lower grades, although fakes have been made for sale to the public. However, before the New Orleans Mint ceased operation in May, 1861, the Confederate government used its own reverse design to strike four half dollars. This made one of the great rarities of American numismatics. A lack of silver and gold precluded further coinage. The Confederacy apparently also experimented with issuing one cent coins, although only 12 were produced by a jeweler in Philadelphia, who was afraid to send them to the South. Like the half dollars, copies were later made as souvenirs.

US coinage was hoarded and did not have any general circulation. U.S. coinage was admitted as legal tender up to $10, as were British sovereigns, Napoléon (coin), French Napoleons and Spanish and Mexican doubloons at a fixed rate of exchange. Confederate money was paper and postage stamps.

Food shortages and riots

By mid-1861, the Union naval blockade virtually shut down the export of cotton and the import of manufactured goods. Food that formerly came overland was cut off.

As women were the ones who remained at home, they had to make do with the lack of food and supplies. They cut back on purchases, used old materials, and planted more flax and peas to provide clothing and food. They used ersatz substitutes when possible, but there was no real coffee, only okra and chicory substitutes. The households were severely hurt by inflation in the cost of everyday items like flour, and the shortages of food, fodder for the animals, and medical supplies for the wounded.

State governments requested that planters grow less cotton and more food, but most refused. When cotton prices soared in Europe, expectations were that Europe would soon intervene to break the blockade and make them rich, but Europe remained neutral. The Georgia legislature imposed cotton quotas, making it a crime to grow an excess. But food shortages only worsened, especially in the towns.

The overall decline in food supplies, made worse by the inadequate transportation system, led to serious shortages and high prices in urban areas. When bacon reached a dollar a pound in 1863, the poor women of Richmond, Atlanta and many other cities began to riot; they broke into shops and warehouses to seize food, as they were angry at ineffective state relief efforts, speculators, and merchants. As wives and widows of soldiers, they were hurt by the inadequate welfare system.

By mid-1861, the Union naval blockade virtually shut down the export of cotton and the import of manufactured goods. Food that formerly came overland was cut off.

As women were the ones who remained at home, they had to make do with the lack of food and supplies. They cut back on purchases, used old materials, and planted more flax and peas to provide clothing and food. They used ersatz substitutes when possible, but there was no real coffee, only okra and chicory substitutes. The households were severely hurt by inflation in the cost of everyday items like flour, and the shortages of food, fodder for the animals, and medical supplies for the wounded.

State governments requested that planters grow less cotton and more food, but most refused. When cotton prices soared in Europe, expectations were that Europe would soon intervene to break the blockade and make them rich, but Europe remained neutral. The Georgia legislature imposed cotton quotas, making it a crime to grow an excess. But food shortages only worsened, especially in the towns.

The overall decline in food supplies, made worse by the inadequate transportation system, led to serious shortages and high prices in urban areas. When bacon reached a dollar a pound in 1863, the poor women of Richmond, Atlanta and many other cities began to riot; they broke into shops and warehouses to seize food, as they were angry at ineffective state relief efforts, speculators, and merchants. As wives and widows of soldiers, they were hurt by the inadequate welfare system.

Devastation by 1865

By the end of the war deterioration of the Southern infrastructure was widespread. The number of civilian deaths is unknown. Every Confederate state was affected, but most of the war was fought in Virginia and Tennessee, while Texas and Florida saw the least military action. Much of the damage was caused by direct military action, but most was caused by lack of repairs and upkeep, and by deliberately using up resources. Historians have recently estimated how much of the devastation was caused by military action. Paul Paskoff calculates that Union military operations were conducted in 56% of 645 counties in nine Confederate states (excluding Texas and Florida). These counties contained 63% of the 1860 white population and 64% of the slaves. By the time the fighting took place, undoubtedly some people had fled to safer areas, so the exact population exposed to war is unknown.Effect on women and families

National flags

[7-, 9, 11-, 13-stars]

"Stars and Bars" Second national flag of the Confederate States of America.svg, 2nd National Flag

[Richmond Capitol]

"Stainless Banner" Confederate National Flag since Mar 4 1865.svg, 3rd National Flag

[never flown]

"Blood Stained Banner" Conf Navy Jack (light blue).svg, CSA Naval Jack

1863–65 Battle flag of the Confederate States of America.svg, Battle Flag

"Southern Cross"

Geography

Region and climate

The Confederate States of America claimed a total of of coastline, thus a large part of its territory lay on the seacoast with level and often sandy or marshy ground. Most of the interior portion consisted of arable farmland, though much was also hilly and mountainous, and the far western territories were deserts. The lower reaches of the Mississippi River bisected the country, with the western half often referred to as the Trans-Mississippi Theater of the American Civil War, Trans-Mississippi. The highest point (excluding Arizona and New Mexico) was Guadalupe Peak in Texas at . Climate

Much of the area claimed by the Confederate States of America had a humid subtropical climate with mild winters and long, hot, humid summers. The climate and terrain varied from vast swamps (such as those in Florida and Louisiana) to semi-arid steppe climate, steppes and arid desert climate, deserts west of longitude 100 degrees west. The subtropical climate made winters mild but allowed infectious diseases to flourish. Consequently, on both sides more soldiers died from disease than were killed in combat,Two-thirds of soldiers' deaths occurred due to disease.

a fact hardly atypical of pre-World War I conflicts.

Climate

Much of the area claimed by the Confederate States of America had a humid subtropical climate with mild winters and long, hot, humid summers. The climate and terrain varied from vast swamps (such as those in Florida and Louisiana) to semi-arid steppe climate, steppes and arid desert climate, deserts west of longitude 100 degrees west. The subtropical climate made winters mild but allowed infectious diseases to flourish. Consequently, on both sides more soldiers died from disease than were killed in combat,Two-thirds of soldiers' deaths occurred due to disease.

a fact hardly atypical of pre-World War I conflicts.

Demographics

Population

The 1860 United States Census, United States Census of 1860 gives a picture of the overall 1860 population for the areas that had joined the Confederacy. Note that the population numbers exclude non-assimilated Indian tribes. In 1860, the areas that later formed the eleven Confederate states (and including the future West Virginia) had 132,760 (1.46%) free blacks. Males made up 49.2% of the total population and females 50.8% (whites: 48.60% male, 51.40% female; slaves: 50.15% male, 49.85% female; free blacks: 47.43% male, 52.57% female).Rural and urban population

The CSA was overwhelmingly rural. Few towns had populations of more than 1,000 – the typical county seat had a population of fewer than 500. Cities were rare; of the twenty largest U.S. cities in the 1860 census, only

The CSA was overwhelmingly rural. Few towns had populations of more than 1,000 – the typical county seat had a population of fewer than 500. Cities were rare; of the twenty largest U.S. cities in the 1860 census, only Military leaders

Military leaders of the Confederacy (with their state or country of birth and highest rank)Eicher, ''Civil War High Commands''. included:

*

Military leaders of the Confederacy (with their state or country of birth and highest rank)Eicher, ''Civil War High Commands''. included:

* See also

* American Civil War prison camps * Cabinet of the Confederate States of America * Commemoration of the American Civil War * Commemoration of the American Civil War on postage stamps * Confederate colonies * Confederate Patent Office * Confederate war finance * ''C.S.A.: The Confederate States of America'' * History of the Southern United States * Knights of the Golden Circle * List of Confederate arms manufacturers * List of Confederate arsenals and armories * List of Confederate monuments and memorials * List of treaties of the Confederate States of America * List of historical separatist movements * List of civil wars * National Civil War Naval MuseumNotes

References

* Bowman, John S. (ed), ''The Civil War Almanac'', New York: Bison Books, 1983 * Eicher, John H., & Eicher, David J., ''Civil War High Commands'', Stanford University Press, 2001, * Martis, Kenneth C. ''The Historical Atlas of the Congresses of the Confederate States of America 1861–1865'' (1994)Further reading

Overviews and reference

''American Annual Cyclopaedia for 1861'' (N.Y.: Appleton's, 1864)

an encyclopedia of events in the U.S. and CSA (and other countries); covers each state in detail

''Appletons' annual cyclopedia and register of important events: Embracing political, military, and ecclesiastical affairs; public documents; biography, statistics, commerce, finance, literature, science, agriculture, and mechanical industry, Volume 3 1863'' (1864)

thorough coverage of the events of 1863 * Beringer, Richard E., Herman Hattaway, Archer Jones, and William N. Still Jr. ''Why the South Lost the Civil War''. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1986. . * Boritt, Gabor S., and others., ''Why the Confederacy Lost'', (1992) * Coulter, E. Merton ''The Confederate States of America, 1861–1865'', 1950 * Current, Richard N., ed. ''Encyclopedia of the Confederacy'' (4 vol), 1993. 1900 pages, articles by scholars. * * Eaton, Clement ''A History of the Southern Confederacy'', 1954 * Faust, Patricia L., ed. ''Historical Times Illustrated History of the Civil War''. New York: Harper & Row, 1986. . * Gallagher, Gary W. ''The Confederate War''. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997. . * Heidler, David S., and Jeanne T. Heidler, eds. ''Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History''. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. . 2740 pages. * James M. McPherson, McPherson, James M. ''Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era''. Oxford History of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988. . standard military history of the war; Pulitzer Prize * Allan Nevins, Nevins, Allan. ''The War for the Union''. Vol. 1, ''The Improvised War 1861–1862''. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1959. ; ''The War for the Union''. Vol. 2, ''War Becomes Revolution 1862–1863''. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1960. ; ''The War for the Union''. Vol. 3, ''The Organized War 1863–1864''. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1971. ; ''The War for the Union''. Vol. 4, ''The Organized War to Victory 1864–1865''. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1971. . The most detailed history of the war. * Charles P. Roland, Roland, Charles P. ''The Confederacy'', (1960) brief survey * * Thomas, Emory M. ''The Confederate Nation, 1861–1865''. New York: Harper & Row, 1979. . Standard political-economic-social history * Wakelyn, Jon L. ''Biographical Dictionary of the Confederacy'' Greenwood Press * Russell Weigley, Weigley, Russell F. ''A Great Civil War: A Military and Political History, 1861–1865''. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2000. .

Historiography

* * Boles, John B. and Evelyn Thomas Nolen, eds. ''Interpreting Southern History: Historiographical Essays in Honor of Sanford W. Higginbotham'' (1987) * * Foote, Lorien. "Rethinking the Confederate home front." ''Journal of the Civil War Era'' 7.3 (2017): 446-46online

* * Grant, Susan-Mary, and Brian Holden Reid, eds. ''The American civil war: explorations and reconsiderations'' (Longman, 2000.) * Hettle, Wallace. ''Inventing Stonewall Jackson: A Civil War Hero in History and Memory'' (LSU Press, 2011). * Link, Arthur S. and Rembert W. Patrick, eds. ''Writing Southern History: Essays in Historiography in Honor of Fletcher M. Green'' (1965) * Sternhell, Yael A. "Revisionism Reinvented? The Antiwar Turn in Civil War Scholarship." ''Journal of the Civil War Era'' 3.2 (2013): 239–25

online

* Woodworth, Steven E. ed. ''The American Civil War: A Handbook of Literature and Research'' (1996), 750 pages of historiography and bibliography

State studies

* Tucker, Spencer, ed. ''American Civil War: A State-by-State Encyclopedia'' (2 vol 2015) 1019ppBorder states