Code Of Hammurabi on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Code of Hammurabi is a Babylonian legal text composed during 1755–1750 BC. It is the longest, best-organized, and best-preserved legal text from the

The relief appears to show Hammurabi standing before a seated Shamash. Shamash wears the horned crown of divinity and has a solar attribute, flames, spouting from his shoulders. Contrastingly, Scheil, in his , identified the seated figure as Hammurabi and the standing figure as Shamash. Scheil also held that the scene showed Shamash dictating to Hammurabi while Hammurabi held a scribe's

The relief appears to show Hammurabi standing before a seated Shamash. Shamash wears the horned crown of divinity and has a solar attribute, flames, spouting from his shoulders. Contrastingly, Scheil, in his , identified the seated figure as Hammurabi and the standing figure as Shamash. Scheil also held that the scene showed Shamash dictating to Hammurabi while Hammurabi held a scribe's

A second theory is that the Code is a sort of law report, and as such contains records of past cases and judgments, albeit phrased abstractly. This would provide one explanation for the casuistic format of the "laws"; indeed, Jean Bottéro believed he had found a record of a case that inspired one. However, such finds are inconclusive and very rare, despite the scale of the Mesopotamian legal corpus. Furthermore, legal judgments were frequently recorded in Mesopotamia, and they recount the facts of the case without generalising them. These judgments were concerned almost exclusively with points of fact, prompting Martha Roth to comment: "I know of only one case out of thousands extant that might be said to revolve around a point of law".

A second theory is that the Code is a sort of law report, and as such contains records of past cases and judgments, albeit phrased abstractly. This would provide one explanation for the casuistic format of the "laws"; indeed, Jean Bottéro believed he had found a record of a case that inspired one. However, such finds are inconclusive and very rare, despite the scale of the Mesopotamian legal corpus. Furthermore, legal judgments were frequently recorded in Mesopotamia, and they recount the facts of the case without generalising them. These judgments were concerned almost exclusively with points of fact, prompting Martha Roth to comment: "I know of only one case out of thousands extant that might be said to revolve around a point of law".

The laws are written in the Old Babylonian dialect of Akkadian. Their style is regular and repetitive, and today they are a standard set text for introductory Akkadian classes. However, as A. Leo Oppenheim summarises, the

The laws are written in the Old Babylonian dialect of Akkadian. Their style is regular and repetitive, and today they are a standard set text for introductory Akkadian classes. However, as A. Leo Oppenheim summarises, the

The Code of Hammurabi bears strong similarities to earlier Mesopotamian law collections. Many purport to have been written by rulers, and this tradition was probably widespread. Earlier law collections express their god-given legitimacy similarly. Like the Code of Hammurabi, they feature prologues and epilogues: the Code of Ur-Nammu has a prologue, the Code of Lipit-Ishtar a prologue and an epilogue, and the Laws of Eshnunna an epilogue. Also, like the Code of Hammurabi, they uphold the "one crime, one punishment" principle. The cases covered and language used are, overall, strikingly similar. Scribes were still copying earlier law collections, such as the Code of Ur-Nammu, when Hammurabi produced his own Code. This suggests that earlier collections may have not only resembled the Code but influenced it. Raymond Westbrook maintained that there was a fairly consistent tradition of "ancient Near Eastern law" which included the Code of Hammurabi, and that this was largely

The Code of Hammurabi bears strong similarities to earlier Mesopotamian law collections. Many purport to have been written by rulers, and this tradition was probably widespread. Earlier law collections express their god-given legitimacy similarly. Like the Code of Hammurabi, they feature prologues and epilogues: the Code of Ur-Nammu has a prologue, the Code of Lipit-Ishtar a prologue and an epilogue, and the Laws of Eshnunna an epilogue. Also, like the Code of Hammurabi, they uphold the "one crime, one punishment" principle. The cases covered and language used are, overall, strikingly similar. Scribes were still copying earlier law collections, such as the Code of Ur-Nammu, when Hammurabi produced his own Code. This suggests that earlier collections may have not only resembled the Code but influenced it. Raymond Westbrook maintained that there was a fairly consistent tradition of "ancient Near Eastern law" which included the Code of Hammurabi, and that this was largely

The Code is often referred to in legal scholarship, where its provisions are assumed to be laws, and the document is assumed to be a true code of laws. This is also true outside academia.

There is a relief portrait of Hammurabi over the doors to the House Chamber of the U.S. Capitol, along with portraits of 22 others "noted for their work in establishing the principles that underlie American law". There are replicas of the Louvre stele in institutions around the world, including the Headquarters of the United Nations in

The Code is often referred to in legal scholarship, where its provisions are assumed to be laws, and the document is assumed to be a true code of laws. This is also true outside academia.

There is a relief portrait of Hammurabi over the doors to the House Chamber of the U.S. Capitol, along with portraits of 22 others "noted for their work in establishing the principles that underlie American law". There are replicas of the Louvre stele in institutions around the world, including the Headquarters of the United Nations in

CDLI's transliteration, normalisation, and translation

Scheil's

(in French)

King's translation

Harper's translation (Wikisource)

The Louvre's page

{{DEFAULTSORT:Code of Hammurabi First Babylonian Empire Legal codes Jurisprudence Legal history Comparative law Ancient Near East law Ancient Near East steles 18th-century BC steles Akkadian inscriptions Akkadian literature Babylonia Babylon Susa 1901 archaeological discoveries 1901 in Iran Archaeological discoveries in Iran Near Eastern and Middle Eastern antiquities in the Louvre Hammurabi

ancient Near East

The ancient Near East was home to many cradles of civilization, spanning Mesopotamia, Egypt, Iran (or Persia), Anatolia and the Armenian highlands, the Levant, and the Arabian Peninsula. As such, the fields of ancient Near East studies and Nea ...

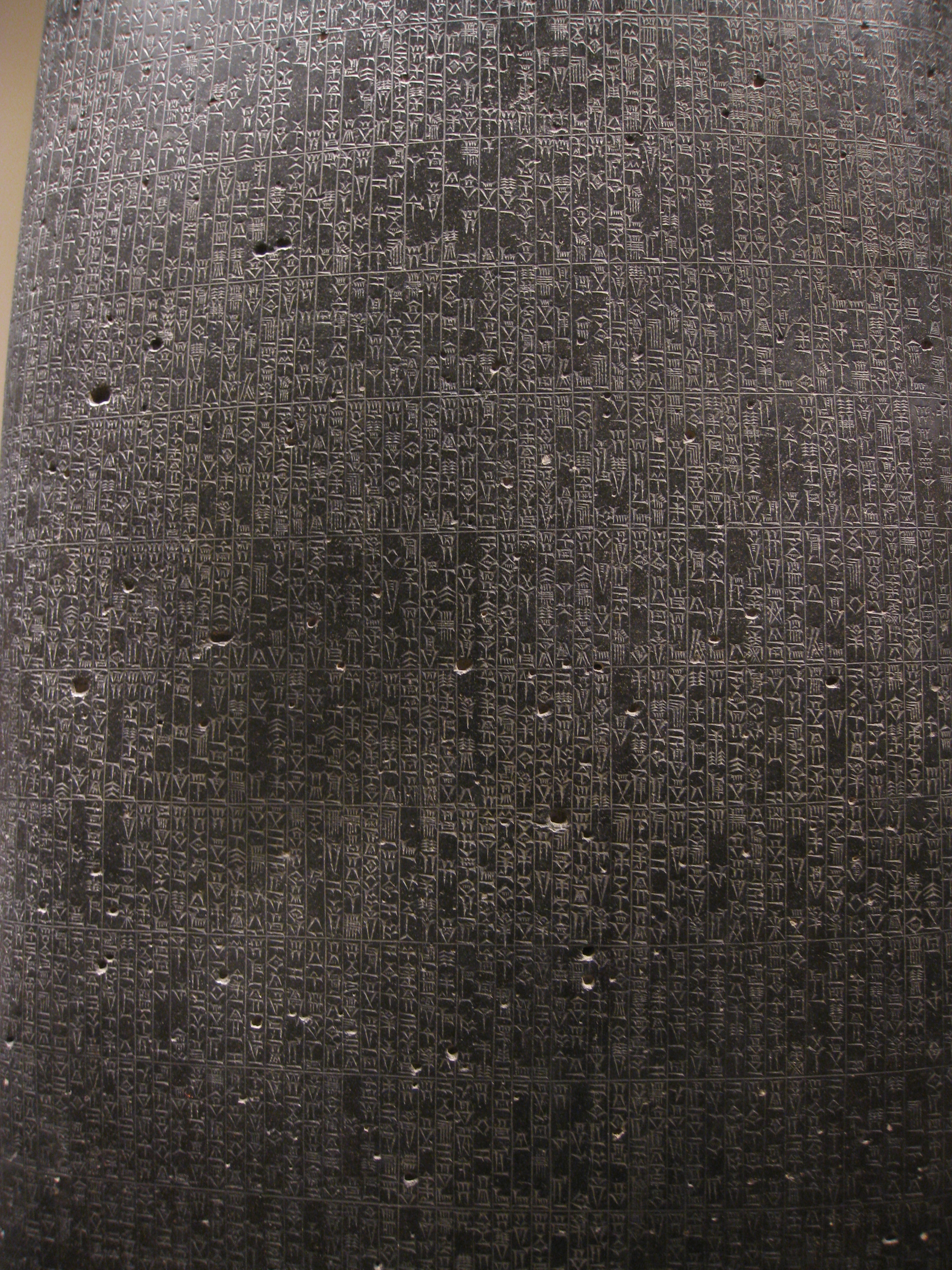

. It is written in the Old Babylonian dialect of Akkadian, purportedly by Hammurabi, sixth king of the First Dynasty of Babylon. The primary copy of the text is inscribed on a basalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanite, aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the planetary surface, surface of a terrestrial ...

stele tall.

The stele was rediscovered in 1901 at the site of Susa in present-day Iran, where it had been taken as plunder six hundred years after its creation. The text itself was copied and studied by Mesopotamian scribes for over a millennium. The stele now resides in the Louvre Museum

The Louvre ( ), or the Louvre Museum ( ), is a national art museum in Paris, France, and one of the most famous museums in the world. It is located on the Rive Droite, Right Bank of the Seine in the city's 1st arrondissement of Paris, 1st arron ...

.

The top of the stele features an image in relief

Relief is a sculpture, sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces remain attached to a solid background of the same material. The term ''wikt:relief, relief'' is from the Latin verb , to raise (). To create a sculpture in relief is to give ...

of Hammurabi with Shamash

Shamash (Akkadian language, Akkadian: ''šamaš''), also known as Utu (Sumerian language, Sumerian: dutu "Sun") was the List of Mesopotamian deities, ancient Mesopotamian Solar deity, sun god. He was believed to see everything that happened in t ...

, the Babylonian sun god and god of justice. Below the relief are about 4,130 lines of cuneiform

Cuneiform is a Logogram, logo-Syllabary, syllabic writing system that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Near East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. Cuneiform script ...

text: one fifth contains a prologue and epilogue in poetic style, while the remaining four fifths contain what are generally called the laws. In the prologue, Hammurabi claims to have been granted his rule by the gods "to prevent the strong from oppressing the weak". The laws are casuistic, expressed as "if... then" conditional sentences. Their scope is broad, including, for example, criminal law

Criminal law is the body of law that relates to crime. It proscribes conduct perceived as threatening, harmful, or otherwise endangering to the property, health, safety, and Well-being, welfare of people inclusive of one's self. Most criminal l ...

, family law

Family law (also called matrimonial law or the law of domestic relations) is an area of the law that deals with family matters and domestic relations.

Overview

Subjects that commonly fall under a nation's body of family law include:

* Marriag ...

, property law

Property law is the area of law that governs the various forms of ownership in real property (land) and personal property. Property refers to legally protected claims to resources, such as land and personal property, including intellectual prope ...

, and commercial law

Commercial law (or business law), which is also known by other names such as mercantile law or trade law depending on jurisdiction; is the body of law that applies to the rights, relations, and conduct of Legal person, persons and organizations ...

.

Modern scholars responded to the Code with admiration at its perceived fairness and respect for the rule of law

The essence of the rule of law is that all people and institutions within a Body politic, political body are subject to the same laws. This concept is sometimes stated simply as "no one is above the law" or "all are equal before the law". Acco ...

, and at the complexity of Old Babylonian society. There was also much discussion of its influence on the Mosaic Law. Scholars quickly identified —the "eye for an eye" principle—underlying the two collections. Debate among Assyriologists has since centred around several aspects of the Code: its purpose, its underlying principles, its language, and its relation to earlier and later law collections.

Despite the uncertainty surrounding these issues, Hammurabi is regarded outside Assyriology as an important figure in the history of law and the document as a true legal code. The U.S. Capitol has a relief portrait of Hammurabi alongside those of other historic lawgivers. There are replicas of the stele in numerous institutions, including the headquarters of the United Nations in New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

and the Pergamon Museum in Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

.

Background

Hammurabi

Hammurabi (or Hammurapi), the sixth king of the Amorite First Dynasty of Babylon, ruled from 1792 to 1750 BC ( middle chronology). He secured Babylonian dominance over theMesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

n plain through military prowess, diplomacy, and treachery. When Hammurabi inherited his father Sin-Muballit's throne, Babylon held little local sway; the local hegemon was Rim-Sin of Larsa

Larsa (, read ''Larsamki''), also referred to as Larancha/Laranchon (Gk. Λαραγχων) by Berossus, Berossos and connected with the biblical Arioch, Ellasar, was an important city-state of ancient Sumer, the center of the Cult (religious pra ...

. Hammurabi waited until Rim-Sin grew old, then conquered his territory in one swift campaign, leaving his organisation intact. Later, Hammurabi betrayed allies in Eshnunna, Elam, and Mari to gain their territories.

Hammurabi had an aggressive foreign policy, but his letters suggest he was concerned with the welfare of his many subjects and was interested in law and justice. He commissioned extensive construction works, and in his letters, he frequently presents himself as his people's shepherd. Justice is also a theme of the prologue to the Code, and "the word translated 'justice' []... is one whose root runs through both prologue and epilogue".

Earlier law collections

Although Hammurabi's Code was the first Mesopotamian law collection to be discovered, it was not the first written; several earlier collections survive. These collections were written in Sumerian and Akkadian. They also purport to have been written by rulers. There were almost certainly more such collections, as statements of other rulers suggest the custom was widespread. The similarities between these law collections make it tempting to assume a consistent underlying legal system. As with the Code of Hammurabi, however, it is difficult to interpret the purpose and underlying legal systems of these earlier collections, prompting numerous scholars to question whether this should be attempted. Extant collections include: * The Code of Ur-Nammu of Ur. * The Code of Lipit-Ishtar of Isin. * TheLaws of Eshnunna

The Laws of Eshnunna (abrv. LE) are inscribed on two cuneiform tablets discovered in Tell Abū Harmal, Baghdad, Iraq. The Iraqi Directorate of Antiquities headed by Taha Baqir unearthed two parallel sets of tablets in 1945 and 1947. The two table ...

(written by Bilalama or by Dadusha).

* The "Laws of X," which, rather than a distinct collection, may be the end of the Code of Ur-Nammu.

There are additionally thousands of documents from the practice of law, from before and during the Old Babylonian period. These documents include contracts, judicial rulings, letters on legal cases, and reform documents such as that of Urukagina, king of Lagash in the mid-3rd millennium BC, whose reforms combatted corruption. Mesopotamia has the most comprehensive surviving legal corpus from before the '' Digest'' of Justinian, even compared to those from ancient Greece

Ancient Greece () was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity (), that comprised a loose collection of culturally and linguistically r ...

and Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

.

Copies

Louvre stele

The first copy of the text found, and still the most complete, is on a stele. The stele is now displayed on the ground floor of theLouvre

The Louvre ( ), or the Louvre Museum ( ), is a national art museum in Paris, France, and one of the most famous museums in the world. It is located on the Rive Droite, Right Bank of the Seine in the city's 1st arrondissement of Paris, 1st arron ...

, in Room 227 of the Richelieu wing. At the top is an image of Hammurabi with Shamash

Shamash (Akkadian language, Akkadian: ''šamaš''), also known as Utu (Sumerian language, Sumerian: dutu "Sun") was the List of Mesopotamian deities, ancient Mesopotamian Solar deity, sun god. He was believed to see everything that happened in t ...

, the Babylonian sun god and god of justice. Below the image are about 4,130 lines of cuneiform

Cuneiform is a Logogram, logo-Syllabary, syllabic writing system that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Near East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. Cuneiform script ...

text: One-fifth contains a prologue and epilogue, while the remaining four-fifths contain what are generally called the laws. Near the bottom, seven columns of the laws, each with more than eighty lines, were polished and erased in antiquity. The stele was found in three large fragments and reconstructed. It is high, with a circumference is at the summit and at the base. Hammurabi's image is high and wide.

The Louvre stele was found at the site of the ancient Elamite city of Susa. Susa is in modern-day Khuzestan Province

Khuzestan province () is one of the 31 Provinces of Iran. Located in the southwest of the country, the province borders Iraq and the Persian Gulf, covering an area of . Its capital is the city of Ahvaz. Since 2014, it has been part of Iran's R ...

, Iran (Persia at the time of excavation). The stele was excavated by the French Archaeological Mission under the direction of Jacques de Morgan

Jean-Jacques de Morgan (3 June 1857 – 14 June 1924) was a French mining engineer, geologist, and archaeologist. He was the director of antiquities in Egypt during the 19th century, and excavated in Memphis and Dahshur, providing many dra ...

. Father Jean-Vincent Scheil published the initial report in the fourth volume of the ''Reports of the Delegation to Persia'' (). According to Scheil, the stele's fragments were found on the tell of the Susa acropolis (), between December 1901 and January 1902. The few, large fragments made assembly easy.

Scheil hypothesised that the stele had been taken to Susa by the Elamite king Shutruk-Nakhunte and that he had commissioned the erasure of several columns of laws to write his legend there. It has been proposed that the relief portion of the stele, especially the beards of Hammurabi and Shamash, was reworked at the same time. Roth suggests the stele was taken as plunder from Sippar, where Hammurabi lived towards the end of his reign.

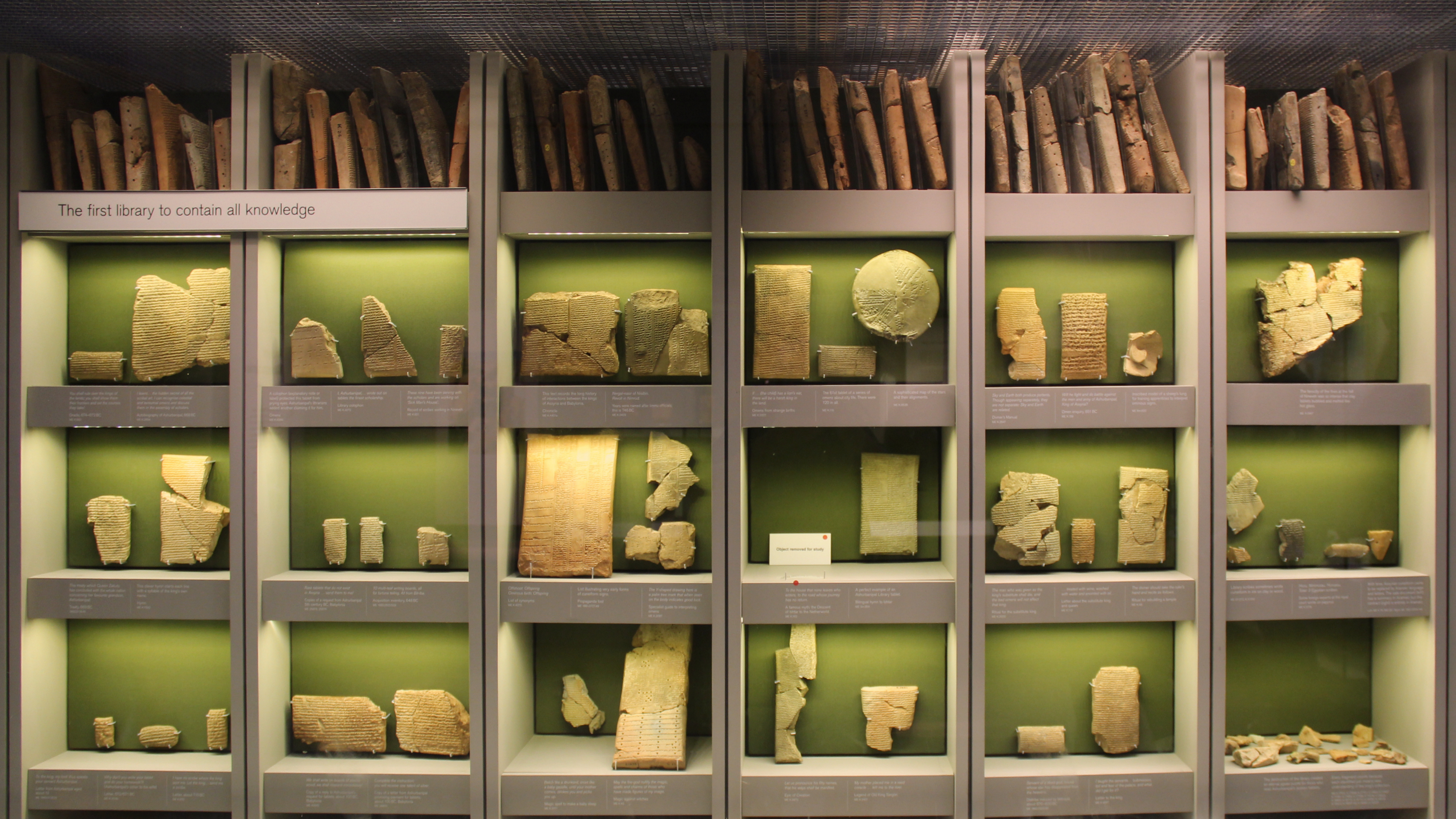

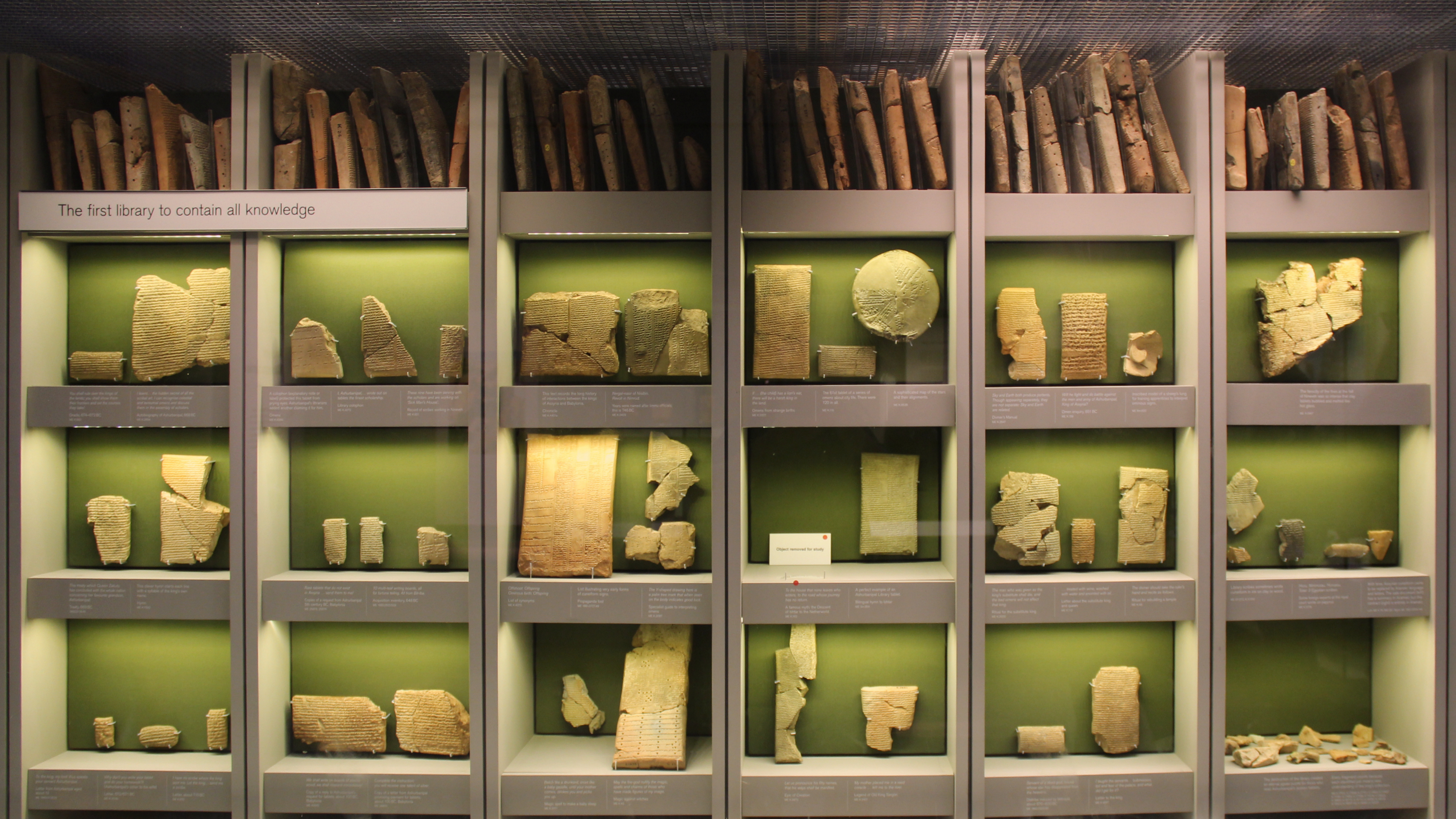

Other copies

Fragments of a second and possibly third stele recording the Code were found along with the Louvre stele at Susa. Over fifty manuscripts containing the laws are known. They were found not only in Susa but also in Babylon,Nineveh

Nineveh ( ; , ''URUNI.NU.A, Ninua''; , ''Nīnəwē''; , ''Nīnawā''; , ''Nīnwē''), was an ancient Assyrian city of Upper Mesopotamia, located in the modern-day city of Mosul (itself built out of the Assyrian town of Mepsila) in northern ...

, Assur, Borsippa, Nippur, Sippar

Sippar (Sumerian language, Sumerian: , Zimbir) (also Sippir or Sippara) was an ancient Near Eastern Sumerian and later Babylonian city on the east bank of the Euphrates river. Its ''Tell (archaeology), tell'' is located at the site of modern Tell ...

, Ur, Larsa, and more. Copies were created during Hammurabi's reign, and also after it, since the text became a part of the scribal curriculum. Copies have been found dating from one thousand years after the stele's creation, and a catalog from the library of Neo-Assyrian king Ashurbanipal (685–631 BC) lists a copy of the "judgments of Hammurabi". The additional copies fill in most of the stele's original text, including much of the erased section.

Early scholarship

The of the Code was published by Father Jean-Vincent Scheil in 1902, in the fourth volume of the ''Reports of the Delegation to Persia'' (). After a brief introduction with details of the excavation, Scheil gave a transliteration and a free translation into French, as well as a selection of images. Editions in other languages soon followed: in German by Hugo Winckler in 1902, in English by C. H. W. Johns in 1903, and in Italian by Pietro Bonfante, also in 1903. The Code was thought to be the earliest Mesopotamian law collection when it was rediscovered in 1902—for example, C. H. W. Johns' 1903 book was titled ''The Oldest Code of Laws in the World''. The English writerH. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells (21 September 1866 – 13 August 1946) was an English writer, prolific in many genres. He wrote more than fifty novels and dozens of short stories. His non-fiction output included works of social commentary, politics, hist ...

included Hammurabi in the first volume of '' The Outline of History'', and to Wells too the Code was "the earliest known code of law". However, three earlier collections were rediscovered afterwards: the Code of Lipit-Ishtar in 1947, the Laws of Eshnunna in 1948, and the Code of Ur-Nammu in 1952. Early commentators dated Hammurabi and the stele to the 23rd century BC. However, this is an earlier estimate than even the " ultra-long chronology" would support. The Code was compiled near the end of Hammurabi's reign. This was deduced partly from the list of his achievements in the prologue.

Scheil enthused about the stele's importance and perceived fairness, calling it "a moral and political masterpiece". C. H. W. Johns called it "one of the most important monuments in the history of the human race". He remarked that "there are many humanitarian clauses and much protection is given the weak and the helpless", and even lauded a "wonderful modernity of spirit". John Dyneley Prince called the Code's rediscovery "the most important event which has taken place in the development of Assyriological science since the days of Rawlinson and Layard". Charles Francis Horne commended the "wise law-giver" and his "celebrated code". James Henry Breasted noted the Code's "justice to the widow, the orphan, and the poor", but remarked that it "also allows many of the old and naïve ideas of justice to stand". Commentators praised the advanced society they believed the Code evinced. Several singled out perceived secularism

Secularism is the principle of seeking to conduct human affairs based on naturalistic considerations, uninvolved with religion. It is most commonly thought of as the separation of religion from civil affairs and the state and may be broadened ...

: Owen Jenkins, for example, but even Charles Souvay for the ''Catholic Encyclopedia

''The'' ''Catholic Encyclopedia: An International Work of Reference on the Constitution, Doctrine, Discipline, and History of the Catholic Church'', also referred to as the ''Old Catholic Encyclopedia'' and the ''Original Catholic Encyclopedi ...

'', who opined that unlike the Mosaic Law the Code was "founded upon the dictates of reason". The question of the Code's influence on the Mosaic Law received much early attention. Scholars also identified Hammurabi with the Biblical figure Amraphel, but this proposal has since been abandoned.

Frame

Relief

The relief appears to show Hammurabi standing before a seated Shamash. Shamash wears the horned crown of divinity and has a solar attribute, flames, spouting from his shoulders. Contrastingly, Scheil, in his , identified the seated figure as Hammurabi and the standing figure as Shamash. Scheil also held that the scene showed Shamash dictating to Hammurabi while Hammurabi held a scribe's

The relief appears to show Hammurabi standing before a seated Shamash. Shamash wears the horned crown of divinity and has a solar attribute, flames, spouting from his shoulders. Contrastingly, Scheil, in his , identified the seated figure as Hammurabi and the standing figure as Shamash. Scheil also held that the scene showed Shamash dictating to Hammurabi while Hammurabi held a scribe's stylus

A stylus is a writing utensil or tool for scribing or marking into softer materials. Different styluses were used to write in cuneiform by pressing into wet clay, and to scribe or carve into a wax tablet. Very hard styluses are also used to En ...

, gazing attentively at the god. Martha Roth lists other interpretations: "that the king is offering the laws to the god; that the king is accepting or offering the emblems of sovereignty of the rod and ring; or—most probably—that these emblems are the measuring tools of the rod-measure and rope-measure used in temple-building". Hammurabi may even be imitating Shamash. It is certain, though, that the draughtsman showed Hammurabi's close links to the divine realm, using composition and iconography.

Prologue

The prologue and epilogue together occupy one-fifth of the text. Out of around 4,130 lines, the prologue occupies 300 lines and the epilogue occupies 500. They are in ring composition around the laws, though there is no visual break distinguishing them from the laws. Both are written in poetic style, and, as William W. Davies wrote, "contain much... which sounds very like braggadocio". The 300-line prologue begins with an etiology of Hammurabi's royal authority (1–49). Anum, the Babyloniansky god

The sky often has important religious significance. Many polytheism, polytheistic religions have deity, deities associated with the sky.

The daytime sky deities are typically distinct from the nighttime ones. Stith Thompson's ''Motif-Index o ...

and king of the gods, granted rulership over humanity to Marduk. Marduk chose the centre of his earthly power to be Babylon, which in the real world worshipped him as its tutelary god. Marduk established the office of kingship within Babylon. Finally, Anum, along with the Babylonian wind god Enlil

Enlil, later known as Elil and Ellil, is an List of Mesopotamian deities, ancient Mesopotamian god associated with wind, air, earth, and storms. He is first attested as the chief deity of the Sumerian pantheon, but he was later worshipped by t ...

, chose Hammurabi to be Babylon's king. Hammurabi was to rule "to prevent the strong from oppressing the weak" (37–39: ). He was to rise like Shamash over the Mesopotamians (the , literally the "black-headed people") and illuminate the land (40–44).'s line numbering, 's translation. The line numbers may seem low, since the CDLI edition does not include sections not found on the Louvre stele.

Hammurabi then lists his achievements and virtues (50–291). These are expressed in noun form, in the Akkadian first person singular nominal sentence construction " oun.. " ("I am oun). The first nominal sentence (50–53) is short: "I am Hammurabi, the shepherd, selected by the god Enlil" (). Then Hammurabi continues for over 200 lines in a single nominal sentence with the delayed to the very end (291).

Hammurabi repeatedly calls himself , "pious" (lines 61, 149, 241, and 272). The metaphor of Hammurabi as his people's shepherd also recurs. It was a common metaphor for ancient Near East

The ancient Near East was home to many cradles of civilization, spanning Mesopotamia, Egypt, Iran (or Persia), Anatolia and the Armenian highlands, the Levant, and the Arabian Peninsula. As such, the fields of ancient Near East studies and Nea ...

ern kings, but is perhaps justified by Hammurabi's interest in his subjects' affairs. His affinities with many different gods are stressed throughout. He is portrayed as dutiful in restoring and maintaining temples and peerless on the battlefield. The list of his accomplishments has helped establish that the text was written late in Hammurabi's reign. After the list, Hammurabi explains that he fulfilled Marduk's request to establish "truth and justice" () for the people (292–302), although the prologue never directly references the laws. The prologue ends "at that time:" (303: ) and the laws begin.

Epilogue

Unlike the prologue, the 500-line epilogue is explicitly related to the laws. The epilogue begins (3144'–3151'): "These are the just decisions which Hammurabi... has established" (). He exalts his laws and his magnanimity (3152'–3239'). He then expresses a hope that "any wronged man who has a lawsuit" () may have the laws of the stele read aloud to him and know his rights (3240'–3256'). This would bring Hammurabi praise (3257'–3275') and divine favour (3276'–3295'). Hammurabi wishes for good fortune for any ruler who heeds his pronouncements and respects his stele (3296'–3359'). However, he invokes the wrath of the gods on any man who disobeys or erases his pronouncements (3360'–3641', the end of the text). The epilogue contains much legal imagery, and the phrase "to prevent the strong from oppressing the weak" (3202'–3203': ) is reused from the prologue. However, the king's main concern appears to be ensuring that his achievements are not forgotten and his name not sullied. The list of curses heaped upon any future defacer is 281 lines long and extremely forceful. Some of the curses are very vivid: "may the god Sin... decree for him a life that is no better than death" (3486'–3508': ); "may he he future defacerconclude every day, month, and year of his reign with groaning and mourning" (3497'–3501': ); may he experience "the spilling of his life force like water" (3435'–3436': ). Hammurabi implores a variety of gods individually to turn their particular attributes against the defacer. For example: "may the tormgod Adad... deprive him of the benefits of rain from heaven and flood from the springs" (3509'–3515': ); "may the god f wisdom Ea... deprive him of all understanding and wisdom, and may he lead him into confusion" (3440'–3451': ). Gods and goddesses are invoked in this order: # Anum (3387'–3394') # Enlil (3395'–3422') # Ninlil (3423'–3439') # Ea (3440'–3458') # Shamash (3459'–3485') # Sin (3486'–3508') # Adad (3509'–3525') # Zababa (3526'–3536') # Ishtar (3537'–3573') # Nergal (3574'–3589') # Nintu (3590'–3599') # Ninkarrak (3600'–3619') # All the gods (3620'–3635') # Enlil, a second time (3636'–3641')Laws

The Code of Hammurabi is the longest and best-organised legal text from the ancient Near East, as well as the best-preserved. The classification below (columns 1–3) is Driver & Miles', with several amendments, and Roth's translation is used. Laws represented by letters are those reconstructed primarily from documents other than the Louvre stele.Theories of purpose

The purpose and legal authority of the Code have been disputed since the mid-20th century. Theories fall into three main categories: that it islegislation

Legislation is the process or result of enrolling, enacting, or promulgating laws by a legislature, parliament, or analogous governing body. Before an item of legislation becomes law it may be known as a bill, and may be broadly referred ...

, whether a code of law or a body of statute

A statute is a law or formal written enactment of a legislature. Statutes typically declare, command or prohibit something. Statutes are distinguished from court law and unwritten law (also known as common law) in that they are the expressed wil ...

s; that it is a sort of law report

A or is a compilation of Legal opinion, judicial opinions from a selection of case law decided by courts. These reports serve as published records of judicial decisions that are cited by lawyers and judges for their use as precedent in subsequ ...

, containing records of past cases and judgments; and that it is an abstract work of jurisprudence

Jurisprudence, also known as theory of law or philosophy of law, is the examination in a general perspective of what law is and what it ought to be. It investigates issues such as the definition of law; legal validity; legal norms and values ...

. The jurisprudence theory has gained much support within Assyriology.

Legislation

The term "code" presupposes that the document was intended to be enforced as legislation. It was used by Scheil in his , and widely adopted afterwards. C. H. W. Johns, one of the most prolific early commentators on the document, proclaimed that "the Code well deserves its name". Recent Assyriologists have used the term without comment, as well as scholars outside Assyriology. However, only if the text was intended as enforced legislation can it truly be called a code of law and its provisions laws. The document, on first inspection, resembles a highly organised code similar to theCode of Justinian

The Code of Justinian (, or ) is one part of the ''Corpus Juris Civilis'', the codification of Roman law ordered early in the 6th century AD by Justinian I, who was Eastern Roman emperor in Constantinople. Two other units, the Digest and the I ...

and the Napoleonic Code

The Napoleonic Code (), officially the Civil Code of the French (; simply referred to as ), is the French civil code established during the French Consulate in 1804 and still in force in France, although heavily and frequently amended since i ...

. There is also evidence that , which in the Code of Hammurabi sometimes denote individual "laws", were enforced. One copy of the Code calls it a , "royal decree", which denotes a kind of enforced legislation.

However, the arguments against this view are strong. Firstly, it would make a very unusual code—Reuven Yaron called the designation "Code" a "persistent misnomer". Vital areas of society and commerce are omitted. For example, Marc Van De Mieroop observes that the Code "deals with cattle and agricultural fields, but it almost entirely ignores the work of shepherds, vital to Babylonia's economy". Then, against the legislation theory more generally, highly implausible circumstances are covered, such as threshing

Threshing or thrashing is the process of loosening the edible part of grain (or other crop) from the straw to which it is attached. It is the step in grain preparation after reaping. Threshing does not remove the bran from the grain.

History of ...

with goats, animals far too unruly for the task (law 270). The laws are also strictly casuistic ("if... then"); unlike in the Mosaic Law, there are no apodictic laws (general commands). These would more obviously suggest prescriptive legislation. The strongest argument against the legislation theory, however, is that most judges appear to have paid the Code no attention. This line of criticism originated with Benno Landsberger in 1950. No Mesopotamian legal document explicitly references the Code or any other law collection, despite the great scale of the corpus. Two references to prescriptions on "a stele" () come closest. In contrast, numerous judgments cite royal -decrees. Raymond Westbrook held that this strengthened the argument from silence that ancient Near Eastern legal "codes" had legal import. Furthermore, many Old Babylonian judgments run entirely counter to the Code's prescriptions.

Law report

A second theory is that the Code is a sort of law report, and as such contains records of past cases and judgments, albeit phrased abstractly. This would provide one explanation for the casuistic format of the "laws"; indeed, Jean Bottéro believed he had found a record of a case that inspired one. However, such finds are inconclusive and very rare, despite the scale of the Mesopotamian legal corpus. Furthermore, legal judgments were frequently recorded in Mesopotamia, and they recount the facts of the case without generalising them. These judgments were concerned almost exclusively with points of fact, prompting Martha Roth to comment: "I know of only one case out of thousands extant that might be said to revolve around a point of law".

A second theory is that the Code is a sort of law report, and as such contains records of past cases and judgments, albeit phrased abstractly. This would provide one explanation for the casuistic format of the "laws"; indeed, Jean Bottéro believed he had found a record of a case that inspired one. However, such finds are inconclusive and very rare, despite the scale of the Mesopotamian legal corpus. Furthermore, legal judgments were frequently recorded in Mesopotamia, and they recount the facts of the case without generalising them. These judgments were concerned almost exclusively with points of fact, prompting Martha Roth to comment: "I know of only one case out of thousands extant that might be said to revolve around a point of law".

Jurisprudence

A third theory, which has gained traction within Assyriology, is that the Code is not a true code but an abstract treatise on how judgments should be formulated. This led Fritz Rudolf Kraus, in an early formulation of the theory, to call it jurisprudence (). Kraus proposed that it was a work of Mesopotamian scholarship in the same category as omen collections like and . Others have provided their own versions of this theory. A. Leo Oppenheim remarked that the Code of Hammurabi and similar Mesopotamian law collections "represent an interesting formulation of social criticism and should not be taken as normative directions". This interpretation bypasses the problem of low congruence between the Code and actual legal judgments. Secondly, the Code does bear striking similarities to other works of Mesopotamian scholarship. Key points of similarity are the list format and the order of the items, which Ann Guinan describes as a complex "serial logic". Marc Van De Mieroop explains that, in common with other works of Mesopotamian scholarship such as omen lists, king lists, and god lists, the entries of the Code of Hammurabi are arranged according to two principles. These are "opposition"—whereby a variable in one entry is altered to make another entry—and "pointillism"—whereby new conditions are added to an entry, or paradigmatic series pursued, to generate a sequence. Van De Mieroop provides the following examples: Laws 215 and 218 illustrate the principle of opposition: one variable of the first law, the outcome of the operations, is altered to create the second. Here, following the principle of pointillism, circumstances are added to the first entry to create more entries. Pointillism also lets list entries be generated by following paradigmatic series common to multiple branches of scholarship. It can thus explain the implausible entries. For example, in the case of the goat used for threshing (law 270), the previous laws concern other animals that ''were'' used for threshing. The established series of domesticated beasts dictated that a goat come next. Wolfram von Soden, who decades earlier called this way of thinking ("list science"), often denigrated it. However, more recent writers, such as Marc Van De Mieroop, Jean Bottéro, and Ann Guinan, have either avoided value judgments or expressed admiration. Lists were central to Mesopotamian science and logic, and their distinctive structural principles let entries be generated infinitely. Linking the Code to the scribal tradition within which "list science" emerged also explains why trainee scribes copied and studied it for over a millennium. The Code appears in a late Babylonian (7th–6th century BC) list of literary and scholarly texts. No other law collection became so entrenched in the curriculum. Rather than a code of laws, then, it may be a scholarly treatise. Much has been written on what the Code suggests about Old Babylonian society and its legal system. For example, whether it demonstrates that there were no professional advocates, or that there were professional judges. Scholars who approach the Code as a self-contained document renounce such claims.Underlying principles

One principle widely accepted to underlie the Code is , or "eye for an eye". Laws 196 and 200 respectively prescribe an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth when one man destroys another's. Punishments determined by could be transferred to the sons of the wrongdoer. For example, law 229 states that the death of a homeowner in a house collapse necessitates the death of the house's builder. The following law 230 states that if the homeowner's son died, the builder's son must die also. Persons were not equal before the law; not just age and profession but also class and gender dictated the punishment or remedy they received. Three main kinds of person, , , and (male)/ (female), are mentioned throughout the Code. A / was a male/female slave. As for and , though contentious, it seems likely that the difference was one of social class, with meaning something like "gentleman" and something like "commoner". The penalties were not necessarily stricter for a than an : a 's life may have been cheaper, but so were some of his fines. There was also inequality within these classes: laws 200 and 202, for example, show that one could be of higher rank than another. The above principles are distant in spirit from modern systems ofcommon

Common may refer to:

As an Irish surname, it is anglicised from Irish Gaelic surname Ó Comáin.

Places

* Common, a townland in County Tyrone, Northern Ireland

* Boston Common, a central public park in Boston, Massachusetts

* Cambridge Com ...

and civil law, but some may be more familiar. One such principle is the presumption of innocence

The presumption of innocence is a legal principle that every person Accused (law), accused of any crime is considered innocent until proven guilt (law), guilty. Under the presumption of innocence, the legal burden of proof is thus on the Prosecut ...

; the first two laws of the stele prescribe punishments, determined by , for unsubstantiated accusations. Written evidence was valued highly, especially in matters of contract

A contract is an agreement that specifies certain legally enforceable rights and obligations pertaining to two or more parties. A contract typically involves consent to transfer of goods, services, money, or promise to transfer any of thos ...

. One crime was given only one punishment. The laws also recognized the importance of the intentions of a defendant. Lastly, the Code's establishment on public stelae was supposedly intended to increase access to justice. Whether or not this was true, suggesting that a wronged man have the stele read aloud to him (lines 3240'–3254') is a concrete measure in this direction, given the inaccessibility of scribal education in the Old Babylonian period.

The prologue asserts that Hammurabi was chosen by the gods. Raymond Westbrook observed that in ancient Near Eastern law, "the king was the primary source of legislation". However, they could delegate their god-given legal authority to judges. However, as Owen B. Jenkins observed, the prescriptions themselves bear "an astonishing absence... of all theological or even ceremonial law".

Language

cuneiform

Cuneiform is a Logogram, logo-Syllabary, syllabic writing system that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Near East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. Cuneiform script ...

signs themselves are "vertically arranged... within boxes placed in bands side by side from right to left", an arrangement already antiquated by Hammurabi's time.

The laws are expressed in casuistic format: they are conditional sentences with the case detailed in the protasis ("if" clause

In language, a clause is a Constituent (linguistics), constituent or Phrase (grammar), phrase that comprises a semantic predicand (expressed or not) and a semantic Predicate (grammar), predicate. A typical clause consists of a subject (grammar), ...

) and the remedy given in the apodosis ("then" clause). The protasis begins , "if", except when it adds to circumstances already specified in a previous law (e.g. laws 36, 38, and 40). The preterite

The preterite or preterit ( ; abbreviated or ) is a grammatical tense or verb form serving to denote events that took place or were completed in the past; in some languages, such as Spanish, French, and English, it is equivalent to the simple p ...

is used for simple past verbs in the protasis, or possibly for a simple conditional. The perfect often appears at the end of the protasis after one or more preterites to convey sequence of action, or possibly a hypothetical conditional. The durative, sometimes called the "present" in Assyriology, may express intention in the laws. For ease of English reading, some translations give preterite and perfect verbs in the protasis a present sense. In the apodosis, the verbs are in the durative, though the sense varies between permissive—"it is permitted that ''x'' happen"—and instructive—"''x'' must/will happen". In both protasis and apodosis, sequence of action is conveyed by suffixing verbs with , "and". can also have the sense "but".

The Code is relatively well-understood, but some items of its vocabulary are controversial. As mentioned, the terms and have proved difficult to translate. They probably denote respectively a male member of a higher and lower social class. Wolfram von Soden, in his '' Akkadisches Handwörterbuch'', proposed that was derived from , "to bow down/supplicate". As a word for a man of low social standing, it has endured, possibly from a Sumerian root, into Arabic (), Italian (), Spanish (), and French (). However, some earlier translators, also seeking to explain the 's special treatment, translated it as "leper" and even "noble". Some translators have supplied stilted readings for , such as "seignior", "elite man", and "member of the aristocracy"; others have left it untranslated. Certain legal terms have also proved difficult to translate. For example, and can denote the law in general as well as individual laws, verdicts, divine pronouncements and other phenomena. can likewise denote the law in general as well as a kind of royal decree.

Relation to other law collections

Other Mesopotamian

The Code of Hammurabi bears strong similarities to earlier Mesopotamian law collections. Many purport to have been written by rulers, and this tradition was probably widespread. Earlier law collections express their god-given legitimacy similarly. Like the Code of Hammurabi, they feature prologues and epilogues: the Code of Ur-Nammu has a prologue, the Code of Lipit-Ishtar a prologue and an epilogue, and the Laws of Eshnunna an epilogue. Also, like the Code of Hammurabi, they uphold the "one crime, one punishment" principle. The cases covered and language used are, overall, strikingly similar. Scribes were still copying earlier law collections, such as the Code of Ur-Nammu, when Hammurabi produced his own Code. This suggests that earlier collections may have not only resembled the Code but influenced it. Raymond Westbrook maintained that there was a fairly consistent tradition of "ancient Near Eastern law" which included the Code of Hammurabi, and that this was largely

The Code of Hammurabi bears strong similarities to earlier Mesopotamian law collections. Many purport to have been written by rulers, and this tradition was probably widespread. Earlier law collections express their god-given legitimacy similarly. Like the Code of Hammurabi, they feature prologues and epilogues: the Code of Ur-Nammu has a prologue, the Code of Lipit-Ishtar a prologue and an epilogue, and the Laws of Eshnunna an epilogue. Also, like the Code of Hammurabi, they uphold the "one crime, one punishment" principle. The cases covered and language used are, overall, strikingly similar. Scribes were still copying earlier law collections, such as the Code of Ur-Nammu, when Hammurabi produced his own Code. This suggests that earlier collections may have not only resembled the Code but influenced it. Raymond Westbrook maintained that there was a fairly consistent tradition of "ancient Near Eastern law" which included the Code of Hammurabi, and that this was largely customary law

A legal custom is the established pattern of behavior within a particular social setting. A claim can be carried out in defense of "what has always been done and accepted by law".

Customary law (also, consuetudinary or unofficial law) exists wher ...

. Nonetheless, there are differences: for example, Stephen Bertman has suggested that where earlier collections are concerned with compensating victims, the Code is concerned with physically punishing offenders. Additionally, the above conclusions of similarity and influence apply only to the law collections themselves. The actual legal practices from the context of each code are mysterious.

The Code of Hammurabi also bears strong similarities to later Mesopotamian law collections: to the casuistic Middle Assyrian Laws and to the Neo-Babylonian Laws, whose format is largely relative ("a man who..."). It is easier to posit direct influence for these later collections, given the Code's survival through the scribal curriculum. Lastly, although influence is more difficult to trace, there is evidence that the Hittite laws may have been part of the same tradition of legal writing outside Mesopotamia proper.

Mosaic, Graeco-Roman, and modern

The relationship of the Code of Hammurabi to the Mosaic Law, specifically the Covenant Code of Exodus 20:22–23:19, has been a subject of discussion since its discovery. Friedrich Delitzsch argued the case for strong influence in a 1902 lecture, in one episode of the "" ("Babel and Bible", or " Panbabylonism") debate on the influence of ancient Mesopotamian cultures on ancient Israel. However, he was met with strong resistance. There was cultural contact between Mesopotamia and the Levant, and Middle Bronze Age tablets of casuistic cuneiform law have been found at Hazor. There are also similarities between the Code of Hamurabi and the Covenant Code: in the casuistic format, in principles such as ("eye for an eye"), and in the content of the provisions. Some similarities are striking, such as in the provisions concerning a man-goring ox (Code of Hammurabi laws 250–252, Exodus 21:28–32). Certain writers have posited direct influence: David P. Wright, for example, asserts that the Covenant Code is "directly, primarily, and throughout dependent upon the Laws of Hammurabi", "a creative rewriting of Mesopotamian sources... to be viewed as an academic abstraction rather than a digest of laws". Others posit indirect influence, such as viaAramaic

Aramaic (; ) is a Northwest Semitic language that originated in the ancient region of Syria and quickly spread to Mesopotamia, the southern Levant, Sinai, southeastern Anatolia, and Eastern Arabia, where it has been continually written a ...

or Phoenicia

Phoenicians were an Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient Semitic group of people who lived in the Phoenician city-states along a coastal strip in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modern Lebanon and the Syria, Syrian ...

n intermediaries. The consensus, however, is that the similarities are a result of inheriting common traditions. In 1916, George A. Barton cited "a similarity of antecedents and of general intellectual outlook". More recently, David Winton Thomas has stated: "There is no ground for assuming any direct borrowing by the Hebrew from the Babylonian. Even where the two sets of laws differ little in the letter, they differ much in the spirit".

The influence of the Code of Hammurabi on later law collections is difficult to establish. Marc Van De Mieroop suggests that it may have influenced the Greek Gortyn Code and the Roman Twelve Tables

The Laws of the Twelve Tables () was the legislation that stood at the foundation of Roman law. Formally promulgated in 449 BC, the Tables consolidated earlier traditions into an enduring set of laws.Crawford, M.H. 'Twelve Tables' in Simon Hornbl ...

. However, even Van De Mieroop acknowledges that most Roman law

Roman law is the law, legal system of ancient Rome, including the legal developments spanning over a thousand years of jurisprudence, from the Twelve Tables (), to the (AD 529) ordered by Eastern Roman emperor Justinian I.

Roman law also den ...

is not similar to the Code, or likely to have been influenced by it.

Knowing the Code's influence on modern law requires knowing its influence on Mosaic and Graeco-Roman law. Since this is contentious, commentators have restricted themselves to observing similarities and differences between the Code and, e.g., United States law

The law of the United States comprises many levels of Codification (law), codified and uncodified forms of law, of which the supreme law is the nation's Constitution of the United States, Constitution, which prescribes the foundation of the ...

and medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with the fall of the West ...

law. Some have remarked that the punishments found in the Code are no more severe, and, in some cases, less so.

Law 238 stipulates that a sea captain

A sea captain, ship's captain, captain, master, or shipmaster, is a high-grade licensed mariner who holds ultimate command and responsibility of a merchant vessel. The captain is responsible for the safe and efficient operation of the ship, inc ...

, ship-manager, or ship charterer that saved a ship from total loss was only required to pay one-half the value of the ship to the ship-owner

A shipowner, ship owner or ship-owner is the owner of a ship. They can be merchant vessels involved in the sea transport, shipping industry or non commercially owned. In the commercial sense of the term, a shipowner is someone who equips and expl ...

. In the '' Digesta seu Pandectae'' (533), the second volume of the codification of laws ordered by Justinian I

Justinian I (, ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was Roman emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign was marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovatio imperii'', or "restoration of the Empire". This ambition was ...

(527–565) of the Eastern Roman Empire, a legal opinion

In law, a legal opinion is in certain jurisdictions a written explanation by a judge or group of judges that accompanies an order or ruling in a case, laying out the rationale and legal principles for the ruling.

Opinions are in those jurisdi ...

written by the Roman jurist Paulus at the beginning of the Crisis of the Third Century

The Crisis of the Third Century, also known as the Military Anarchy or the Imperial Crisis, was a period in History of Rome, Roman history during which the Roman Empire nearly collapsed under the combined pressure of repeated Barbarian invasions ...

in 235 AD was included about the '' Lex Rhodia'' ("Rhodian law") that articulates the general average principle of marine insurance established on the island of Rhodes

Rhodes (; ) is the largest of the Dodecanese islands of Greece and is their historical capital; it is the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, ninth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea. Administratively, the island forms a separ ...

in approximately 1000 to 800 BC as a member of the Doric Hexapolis, plausibly by the Phoenicia

Phoenicians were an Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient Semitic group of people who lived in the Phoenician city-states along a coastal strip in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modern Lebanon and the Syria, Syrian ...

ns during the proposed Dorian invasion and emergence of the purported Sea Peoples during the Greek Dark Ages (c. 1100 – c. 750) that led to the proliferation of the Doric Greek

Doric or Dorian (), also known as West Greek, was a group of Ancient Greek dialects; its Variety (linguistics), varieties are divided into the Doric proper and Northwest Doric subgroups. Doric was spoken in a vast area, including northern Greec ...

dialect

A dialect is a Variety (linguistics), variety of language spoken by a particular group of people. This may include dominant and standard language, standardized varieties as well as Vernacular language, vernacular, unwritten, or non-standardize ...

. The law of general average constitutes the fundamental principle

A principle may relate to a fundamental truth or proposition that serves as the foundation for a system of beliefs or behavior or a chain of reasoning. They provide a guide for behavior or evaluation. A principle can make values explicit, so t ...

that underlies all insurance

Insurance is a means of protection from financial loss in which, in exchange for a fee, a party agrees to compensate another party in the event of a certain loss, damage, or injury. It is a form of risk management, primarily used to protect ...

.

Reception outside Assyriology

The Code is often referred to in legal scholarship, where its provisions are assumed to be laws, and the document is assumed to be a true code of laws. This is also true outside academia.

There is a relief portrait of Hammurabi over the doors to the House Chamber of the U.S. Capitol, along with portraits of 22 others "noted for their work in establishing the principles that underlie American law". There are replicas of the Louvre stele in institutions around the world, including the Headquarters of the United Nations in

The Code is often referred to in legal scholarship, where its provisions are assumed to be laws, and the document is assumed to be a true code of laws. This is also true outside academia.

There is a relief portrait of Hammurabi over the doors to the House Chamber of the U.S. Capitol, along with portraits of 22 others "noted for their work in establishing the principles that underlie American law". There are replicas of the Louvre stele in institutions around the world, including the Headquarters of the United Nations in New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

and the Peace Palace in The Hague

The Hague ( ) is the capital city of the South Holland province of the Netherlands. With a population of over half a million, it is the third-largest city in the Netherlands. Situated on the west coast facing the North Sea, The Hague is the c ...

(seat of the International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice (ICJ; , CIJ), or colloquially the World Court, is the only international court that Adjudication, adjudicates general disputes between nations, and gives advisory opinions on International law, internation ...

).

Medico-legal legacy and political implications

Hammurabi's Code is notable for its comprehensive approach to law, covering subjects from criminal acts to medical practices. The Code includes specific rules that regulate medical treatments, set surgery fees, and punish malpractice. For instance, if a physician caused the death of a noble during surgery, they would be severely punished, sometimes having their hand cut off. This harshness portrays how seriously medical responsibility was taken even in ancient times. From a political science perspective, Hammurabi's Code is valuable and fundamental because it demonstrates how law was used to reinforce social hierarchies and maintain control. writes that the Code's laws were applied differently depending on a person's social class, so nobles received greater protection than commoners and enslaved people. This legal stratification reflects the power dynamic of Babylonian society and shows how law was used not just to govern but also to preserve the social order. Finally, the Hammurabi's Code could be considered impressive by its power (despite its modern irrelevancy) and severity. The harsh punishments may seem extreme by modern standards, but they were likely necessary to maintain order in a society where survival depended on strict adherence to rules. At the same time, Hammurabi's Code represents a significant step forward in the development of law, medicine and the medico-legal system. By codifying laws and making them public, Hammurabi established a system that would influence generations so that the principles of justice, fairness, and accountability that underpin the Code continue to resonate today.See also

* History of institutions in MesopotamiaReferences

Notes

Citations

Sources

Books and journals

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Web

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

CDLI's transliteration, normalisation, and translation

Scheil's

(in French)

King's translation

Harper's translation (Wikisource)

The Louvre's page

{{DEFAULTSORT:Code of Hammurabi First Babylonian Empire Legal codes Jurisprudence Legal history Comparative law Ancient Near East law Ancient Near East steles 18th-century BC steles Akkadian inscriptions Akkadian literature Babylonia Babylon Susa 1901 archaeological discoveries 1901 in Iran Archaeological discoveries in Iran Near Eastern and Middle Eastern antiquities in the Louvre Hammurabi