Claude Bernard on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

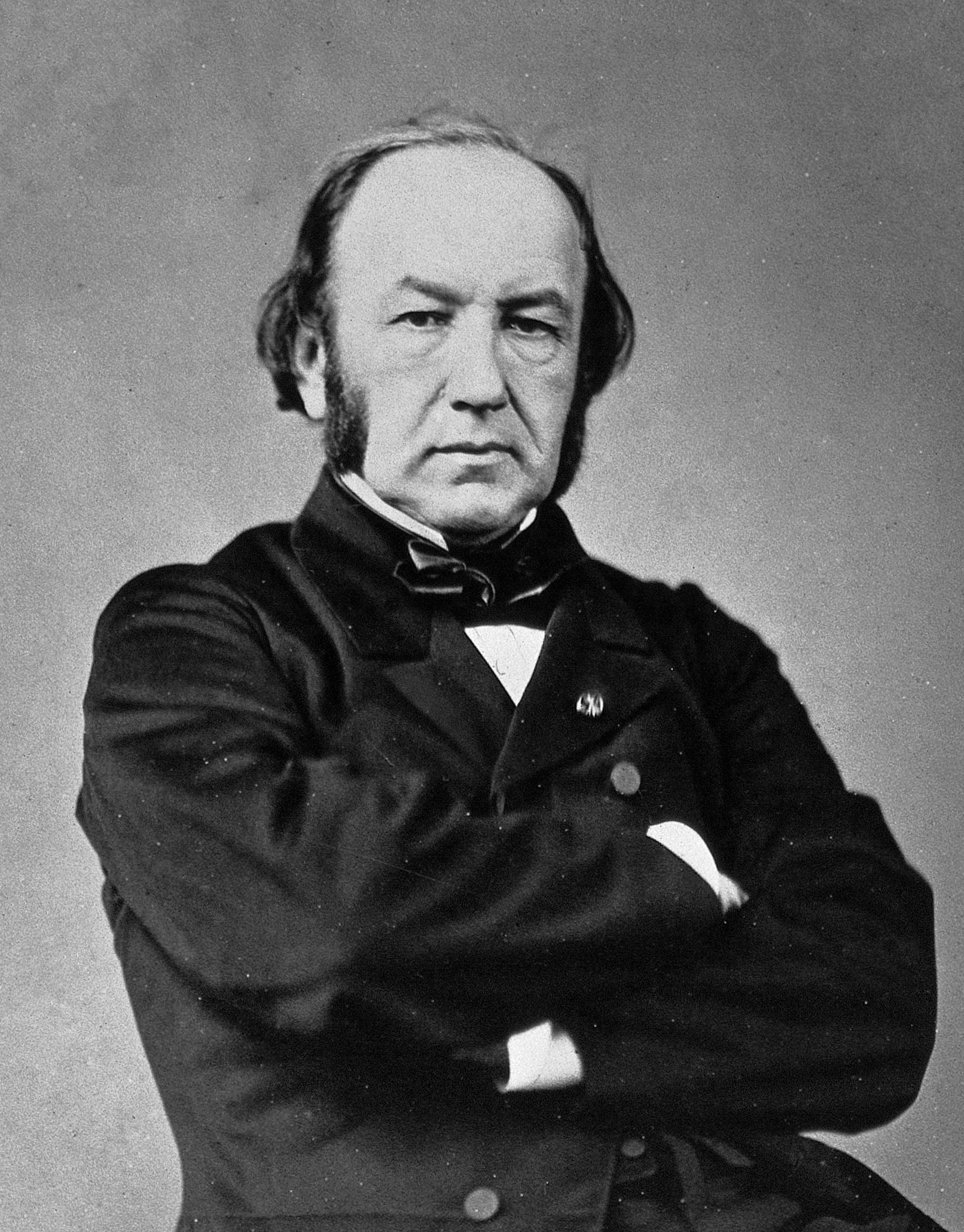

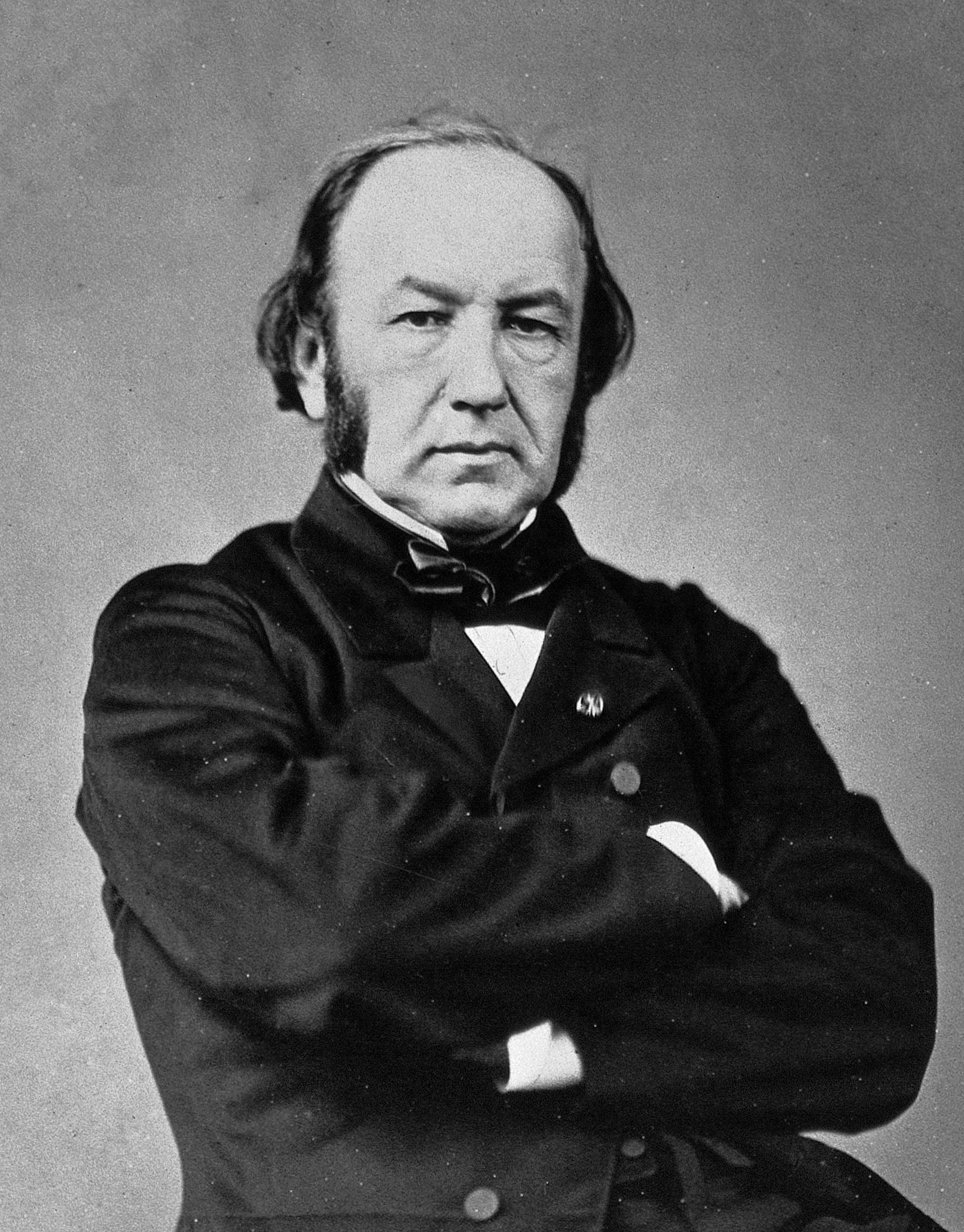

Claude Bernard (; 12 July 1813 – 10 February 1878) was a French physiologist. I. Bernard Cohen of

Bernard's first major work was on the functions of the

Bernard's first major work was on the functions of the

"Re-appraising Claude Bernard's Legacy. History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences"

a collection from '' History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences'', edited by Laurent Loison * * * * *

Biography, bibliography, and links on digitized sources

in the Virtual Laboratory of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science

'Claude Bernard': detailed biography and a comprehensive bibliography linked to complete on-line texts, quotations, images and more.

*

Claude Bernard's works

digitized by th

BIUM (Bibliothèque interuniversitaire de médecine et d'odontologie, Paris)

see its digital librar

{{DEFAULTSORT:Bernard, Claude 1813 births 1878 deaths People from Rhône (department) Academic staff of the Collège de France French Roman Catholics French physiologists French medical writers Members of the Académie Française Members of the French Academy of Sciences Burials at Père Lachaise Cemetery Recipients of the Copley Medal Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Members of the Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters Academic staff of the École pratique des hautes études Corresponding members of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences Academic staff of the University of Paris Foreign members of the Royal Society University of Paris alumni International members of the American Philosophical Society

Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

called Bernard "one of the greatest of all men of science". He originated the term ''milieu intérieur

The internal environment (or ''milieu intérieur'' in French; ) was a concept developed by Claude Bernard, a French physiologist in the 19th century, to describe the interstitial fluid and its physiological capacity to ensure protective stabi ...

'' and the associated concept of homeostasis

In biology, homeostasis (British English, British also homoeostasis; ) is the state of steady internal physics, physical and chemistry, chemical conditions maintained by organism, living systems. This is the condition of optimal functioning fo ...

(the latter term being coined by Walter Cannon).

Life

Bernard was born in 12 July 1813 in the village of Saint-Julien, near Villefranche-sur-Saône. He received his early education in theJesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

school of that town, then attended college at Lyon

Lyon (Franco-Provençal: ''Liyon'') is a city in France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of the French Alps, southeast of Paris, north of Marseille, southwest of Geneva, Switzerland, north ...

, which he soon left to become assistant in a druggist's shop. He is sometimes described as an agnostic, and even humorously referred to by his colleagues as a "great priest of atheism". Despite this, after his death Cardinal Ferdinand Donnet claimed Bernard was a fervent Catholic, with a biographical entry in the ''Catholic Encyclopedia''. His leisure hours were devoted to the composition of a vaudeville

Vaudeville (; ) is a theatrical genre of variety entertainment which began in France in the middle of the 19th century. A ''vaudeville'' was originally a comedy without psychological or moral intentions, based on a comical situation: a drama ...

comedy, and the success it achieved moved him to attempt a prose drama in five acts, ''Arthur de Bretagne''. ''Arthur de Bretagne'', was published only after his death. A second edition appeared in 1943.

In 1834, at the age of twenty-one, he went to Paris to present this play to critic Saint-Marc Girardin, but was dissuaded from adopting literature as a profession. Girardin urged him to take up the study of medicine instead. Bernard followed his advice, later becoming an ''interne'' at the Hôtel-Dieu de Paris In French-speaking countries, a hôtel-Dieu () was originally a hospital for the poor and needy, run by the Catholic Church. Nowadays these buildings or institutions have either kept their function as a hospital, the one in Paris being the oldest an ...

. There, he met physiologist François Magendie, who served as physician at the hospital. Bernard became ''preparateur'' (lab assistant) at the in 1841.

In 1845, he married Marie Françoise "Fanny" Martin for convenience; the marriage was arranged by a colleague and her dowry helped finance his experiments. In 1847 he was appointed Magendie's deputy-professor at the college, and in 1855 he succeeded him as full professor. In 1860, Bernard was elected an international member of the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS) is an American scholarly organization and learned society founded in 1743 in Philadelphia that promotes knowledge in the humanities and natural sciences through research, professional meetings, publicat ...

. His field of research was considered inferior at the time, and the laboratory assigned to him was a "regular cellar."

Bernard was chosen around this time to be the inaugural Chair of physiology at the Sorbonne, but no laboratory was provided for his use. After speaking with Bernard in 1864, Louis Napoleon built a laboratory at the Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle

The French National Museum of Natural History ( ; abbr. MNHN) is the national natural history museum of France and a of higher education part of Sorbonne University. The main museum, with four galleries, is located in Paris, France, within the Ja ...

in the Jardin des Plantes

The Jardin des Plantes (, ), also known as the Jardin des Plantes de Paris () when distinguished from other ''jardins des plantes'' in other cities, is the main botanical garden in France. Jardin des Plantes is the official name in the present da ...

for him. At the same time, Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles-Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was President of France from 1848 to 1852 and then Emperor of the French from 1852 until his deposition in 1870. He was the first president, second emperor, and last ...

established a professorship which Bernard accepted, leaving the Sorbonne in 1868. In the same year, he was also admitted a member of the ''Académie française

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of tertiary education. The name traces back to Plato's school of philosophy, founded approximately 386 BC at Akademia, a sanctuary of Athena, the go ...

'' and elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences () is one of the Swedish Royal Academies, royal academies of Sweden. Founded on 2 June 1739, it is an independent, non-governmental scientific organization that takes special responsibility for promoting nat ...

.

When he died on 10 February 1878, he was given a public funeral, which France had never allowed for a man of science. He was interred in Père Lachaise Cemetery

Père Lachaise Cemetery (, , formerly , ) is the largest cemetery in Paris, France, at . With more than 3.5 million visitors annually, it is the most visited necropolis in the world.

Buried at Père Lachaise are many famous figures in the ...

in Paris.

Career

Bernard's first major work was on the functions of the

Bernard's first major work was on the functions of the pancreas

The pancreas (plural pancreases, or pancreata) is an Organ (anatomy), organ of the Digestion, digestive system and endocrine system of vertebrates. In humans, it is located in the abdominal cavity, abdomen behind the stomach and functions as a ...

. His discovery that the juices

Juice is a drink made from the extraction or pressing of the natural liquid contained in fruit and vegetables. It can also refer to liquids that are flavored with concentrate or other biological food sources, such as meat or seafood, ...

are a significant part of the digestive process won him the prize for experimental physiology from the French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (, ) is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French Scientific method, scientific research. It was at the forefron ...

. In perhaps his most famous experiment, he discovered the glycogen

Glycogen is a multibranched polysaccharide of glucose that serves as a form of energy storage in animals, fungi, and bacteria. It is the main storage form of glucose in the human body.

Glycogen functions as one of three regularly used forms ...

ic function of the liver

The liver is a major metabolic organ (anatomy), organ exclusively found in vertebrates, which performs many essential biological Function (biology), functions such as detoxification of the organism, and the Protein biosynthesis, synthesis of var ...

. The liver, in addition to secreting bile, also produces the sugars that can cause hypoglycemia

Hypoglycemia (American English), also spelled hypoglycaemia or hypoglycæmia (British English), sometimes called low blood sugar, is a fall in blood sugar to levels below normal, typically below 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L). Whipple's tria ...

, which helped advance study of diabetes mellitus

Diabetes mellitus, commonly known as diabetes, is a group of common endocrine diseases characterized by sustained hyperglycemia, high blood sugar levels. Diabetes is due to either the pancreas not producing enough of the hormone insulin, or th ...

and its causes. In 1851, while examining the effects produced in the temperature of various parts of the body by each section of the nerve or nerves belonging to them, he noticed that division of the cervical sympathetic nerve resulted in more active circulation and more forcible pulsation of the arteries in certain parts of the head. A few months later, he observed that electrical excitation of the upper portion of the divided nerve had the contrary effect. This discovery of the vasomotor system also established the existence of both vasodilator

Vasodilation, also known as vasorelaxation, is the widening of blood vessels. It results from relaxation of smooth muscle cells within the vessel walls, in particular in the large veins, large arteries, and smaller arterioles. Blood vessel wal ...

and vasoconstrictor nerves.

Bernard's scientific discoveries were made through vivisection

Vivisection () is surgery conducted for experimental purposes on a living organism, typically animals with a central nervous system, to view living internal structure. The word is, more broadly, used as a pejorative catch-all term for Animal test ...

, of which he was the primary proponent in Europe at the time. In his description of the single-mindedness of scientists trying to prove their theories, he wrote: " does not hear the animals' cries of pain. He is blind to the blood that flows." His use of vivisection disgusted his wife and daughters, who returned at home once to discover that he had vivisected the family dog. The couple was officially separated in 1869 and his wife went on to actively campaign against the practice of vivisection. Some in the scientific community were also uncomfortable with the practice. The physician-scientist George Hoggan spent four months observing and working in Bernard's laboratory, later writing that his experiences there had "prepared imto see not only science, but even mankind, perish rather than have recourse to such means of saving it." Hoggan was a founding member of the National Anti-Vivisection Society

The National Anti-Vivisection Society (NAVS) is an international non-profit Animal welfare, animal protection group, based in London, working to end animal testing, and focused on the replacement of animals in research with advanced, scientific t ...

in the mid-1870s.

Milieu intérieur

The internal environment (or ''milieu intérieur'' in French; ) was a concept developed by Claude Bernard, a French physiologist in the 19th century, to describe the interstitial fluid and its physiological capacity to ensure protective stabi ...

, the "internal environment", is the key concept with which Bernard is associated. He explained that the body is "relatively independent" of the outside world, and that a healthy "internal environment" adapts to deficiencies in the surrounding environment, thus keeping the physiology balanced. This is the underlying principle of what would later be called homeostasis

In biology, homeostasis (British English, British also homoeostasis; ) is the state of steady internal physics, physical and chemistry, chemical conditions maintained by organism, living systems. This is the condition of optimal functioning fo ...

, a term coined by Walter Cannon.

Bernard was also interested in the physiological action of poisons, particularly curare and carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide (chemical formula CO) is a poisonous, flammable gas that is colorless, odorless, tasteless, and slightly less dense than air. Carbon monoxide consists of one carbon atom and one oxygen atom connected by a triple bond. It is the si ...

gas. He is credited with first describing carbon monoxide's affinity for hemoglobin

Hemoglobin (haemoglobin, Hb or Hgb) is a protein containing iron that facilitates the transportation of oxygen in red blood cells. Almost all vertebrates contain hemoglobin, with the sole exception of the fish family Channichthyidae. Hemoglobin ...

in 1857, although James Watt

James Watt (; 30 January 1736 (19 January 1736 OS) – 25 August 1819) was a Scottish inventor, mechanical engineer, and chemist who improved on Thomas Newcomen's 1712 Newcomen steam engine with his Watt steam engine in 1776, which was f ...

had drawn similar conclusions about hydrocarbonate's affinity for blood acting as "an antidote to the oxygen" in 1794 prior to the discoveries of carbon monoxide and hemoglobin.

Throughout his career, Bernard sought to establish the use in medicine of what would later become the scientific method

The scientific method is an Empirical evidence, empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has been referred to while doing science since at least the 17th century. Historically, it was developed through the centuries from the ancient and ...

. In ''An Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine'' (1865), he emphasized the importance of trusting evidence over clout, even if it "contradicts a prevailing theory," as " eories are only hypotheses" proven or disproven by facts. He criticized scientists who cherry-picked their data only to prove their own hypotheses.Bernard (1957), p. 38. Unlike many scientific writers of his time, Bernard wrote using the first person when discussing his own experiments and thoughts.Bernard (1957)

References

Further reading

"Re-appraising Claude Bernard's Legacy. History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences"

a collection from '' History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences'', edited by Laurent Loison * * * * *

External links

* * *Biography, bibliography, and links on digitized sources

in the Virtual Laboratory of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science

'Claude Bernard': detailed biography and a comprehensive bibliography linked to complete on-line texts, quotations, images and more.

*

Claude Bernard's works

digitized by th

BIUM (Bibliothèque interuniversitaire de médecine et d'odontologie, Paris)

see its digital librar

{{DEFAULTSORT:Bernard, Claude 1813 births 1878 deaths People from Rhône (department) Academic staff of the Collège de France French Roman Catholics French physiologists French medical writers Members of the Académie Française Members of the French Academy of Sciences Burials at Père Lachaise Cemetery Recipients of the Copley Medal Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Members of the Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters Academic staff of the École pratique des hautes études Corresponding members of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences Academic staff of the University of Paris Foreign members of the Royal Society University of Paris alumni International members of the American Philosophical Society