Clarno Formation on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Day Fossil Beds National Monument is a

The Clarno Unit, the westernmost of the three units, consists of located west of

The Clarno Unit, the westernmost of the three units, consists of located west of  The park headquarters and main visitor center, both in the Sheep Rock Unit, are northeast of Bend and southeast of

The park headquarters and main visitor center, both in the Sheep Rock Unit, are northeast of Bend and southeast of

Early inhabitants of north-central Oregon included Sahaptin-speaking people of the Umatilla, Wasco, and Warm Springs tribes as well as the

Early inhabitants of north-central Oregon included Sahaptin-speaking people of the Umatilla, Wasco, and Warm Springs tribes as well as the  The John Day basin remained largely unexplored by non-natives until the mid-19th century.

The John Day basin remained largely unexplored by non-natives until the mid-19th century.  In 1864, a company of soldiers sent to protect mining camps from raids by Northern Paiutes discovered fossils in the Crooked River region, south of the John Day basin. One of their leaders, Captain John M. Drake, collected some of these fossils for

In 1864, a company of soldiers sent to protect mining camps from raids by Northern Paiutes discovered fossils in the Crooked River region, south of the John Day basin. One of their leaders, Captain John M. Drake, collected some of these fossils for  Merriam, a

Merriam, a

The John Day Fossil Beds National Monument lies within the Blue Mountains

The John Day Fossil Beds National Monument lies within the Blue Mountains  The monument contains extensive deposits of well-preserved fossils from various periods spanning more than 40 million years. Taken as a whole, the fossils present an unusually detailed view of plants and animals since the late Eocene. In addition, analysis of the John Day fossils has contributed to

The monument contains extensive deposits of well-preserved fossils from various periods spanning more than 40 million years. Taken as a whole, the fossils present an unusually detailed view of plants and animals since the late Eocene. In addition, analysis of the John Day fossils has contributed to

More than 80 soil types support a wide variety of flora within the monument. These soils stem from past and present geologic activity as well as ongoing additions of organic matter from life forms on or near the surface. Adapted to particular soil types and surface conditions, these plant communities range from

More than 80 soil types support a wide variety of flora within the monument. These soils stem from past and present geologic activity as well as ongoing additions of organic matter from life forms on or near the surface. Adapted to particular soil types and surface conditions, these plant communities range from

Birds are the animals most often seen in the monument. Included among the more than 50 species observed are

Birds are the animals most often seen in the monument. Included among the more than 50 species observed are  A 2003–04 survey of the monument found 55 species of butterflies such as the common sootywing, orange sulphur, great spangled fritillary, and

A 2003–04 survey of the monument found 55 species of butterflies such as the common sootywing, orange sulphur, great spangled fritillary, and

Entrance to the park and its visitor center, museums, and exhibits is free, and trails, overlooks, and picnic sites at all three units are open during daylight hours year-round. No food, lodging, or fuel is available in the park, and camping is not allowed. Hours of operation for the Cant Ranch and its cultural museum vary seasonally. The Thomas Condon Paleontology Center is open every day from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m except for federal holidays during the winter season from

Entrance to the park and its visitor center, museums, and exhibits is free, and trails, overlooks, and picnic sites at all three units are open during daylight hours year-round. No food, lodging, or fuel is available in the park, and camping is not allowed. Hours of operation for the Cant Ranch and its cultural museum vary seasonally. The Thomas Condon Paleontology Center is open every day from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m except for federal holidays during the winter season from

Official website

at th

John Day Fossil Beds

at ''The Oregon Encyclopedia''

State of the Park Report

– National Park Service, December 2013

– National Park Service, interactive

— real-time views of the Paleontology Lab and Sheep Rock

National Park Service: Wild Flowers at John Day Fossil Beds

— illustrated (PDF). {{authority control National Park Service national monuments in Oregon Fossil parks in the United States Fossil trackways in the United States Parks in Grant County, Oregon Protected areas of Wheeler County, Oregon Museums in Grant County, Oregon Natural history museums in Oregon Volcanoes of Oregon Landforms of Grant County, Oregon Landforms of Wheeler County, Oregon Eocene paleontological sites of North America Paleogene geology of Oregon Paleontology in Oregon Cenozoic paleontological sites of North America Protected areas established in 1975 1975 establishments in Oregon 1864 in paleontology 1975 in paleontology National Natural Landmarks in Oregon

U.S. national monument

In the United States, a national monument is a protected area that can be created from any land owned or controlled by the Federal government of the United States, federal government by Presidential proclamation (United States), proclamation ...

in Wheeler and Grant counties in east-central Oregon

Oregon ( , ) is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is a part of the Western U.S., with the Columbia River delineating much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while t ...

. Located within the John Day River

The John Day River is a tributary of the Columbia River, approximately long, in northeastern Oregon in the United States. It is known as the Mah-Hah River by the Cayuse people. Undammed along its entire length, the river is the fourth longest ...

basin and managed by the National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an List of federal agencies in the United States, agency of the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government, within the US Department of the Interior. The service manages all List ...

, the park is known for its well-preserved layers of fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserve ...

plants and mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

s that lived in the region between the late Eocene

The Eocene ( ) is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (Ma). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene'' comes ...

, about 45 million years ago, and the late Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first epoch (geology), geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and mea ...

, about 5 million years ago. The monument consists of three geographically separate units: Sheep Rock, Painted Hills, and Clarno.

The units cover a total of of semi-desert shrublands, riparian zone

A riparian zone or riparian area is the interface between land and a river or stream. In some regions, the terms riparian woodland, riparian forest, riparian buffer zone, riparian corridor, and riparian strip are used to characterize a ripari ...

s, and colorful badlands

Badlands are a type of dry terrain where softer sedimentary rocks and clay-rich soils have been extensively eroded."Badlands" in '' Chambers's Encyclopædia''. London: George Newnes, 1961, Vol. 2, p. 47. They are characterized by steep slopes, ...

. About 210,000 people visited the park in 2016 to engage in outdoor recreation or to visit the Thomas Condon Paleontology Center or the James Cant Ranch Historic District.

Before the arrival of Euro-Americans in the 19th century, the John Day basin was frequented by Sahaptin people who hunted, fished, and gathered roots and berries in the region. After road-building made the valley more accessible, settlers established farms, ranches, and a few small towns along the river and its tributaries. Paleontologists have been unearthing and studying the fossils in the region since 1864, when Thomas Condon

Thomas Condon (1822–1907) was an Irish Congregational church, Congregational minister, geologist, and paleontology, paleontologist who gained recognition for his work in the U.S. state of Oregon.

Life and career

Condon arrived in New York Cit ...

, a missionary and amateur geologist, recognized their importance and made them known globally. Parts of the basin became a National Monument in 1975.

Averaging about in elevation, the monument has a dry climate with temperatures that vary from summer highs of about to winter lows below freezing. The monument has more than 80 soil types that support a wide variety of flora, ranging from willow trees near the river to grasses on alluvial fan

An alluvial fan is an accumulation of sediments that fans outwards from a concentrated source of sediments, such as a narrow canyon emerging from an escarpment. They are characteristic of mountainous terrain in arid to Semi-arid climate, semiar ...

s to cactus among rocks at higher elevations. Fauna include more than 50 species of resident and migratory birds. Large mammals like elk

The elk (: ''elk'' or ''elks''; ''Cervus canadensis'') or wapiti, is the second largest species within the deer family, Cervidae, and one of the largest terrestrial mammals in its native range of North America and Central and East Asia. ...

and smaller animals such as raccoon

The raccoon ( or , ''Procyon lotor''), sometimes called the North American, northern or common raccoon (also spelled racoon) to distinguish it from Procyonina, other species of raccoon, is a mammal native to North America. It is the largest ...

s, coyote

The coyote (''Canis latrans''), also known as the American jackal, prairie wolf, or brush wolf, is a species of canis, canine native to North America. It is smaller than its close relative, the Wolf, gray wolf, and slightly smaller than the c ...

s, and voles

Voles are small rodents that are relatives of lemmings and hamsters, but with a stouter body; a longer, hairy tail; a slightly rounder head; smaller eyes and ears; and differently formed molar (tooth), molars (high-crowned with angular cusps i ...

frequent these units, which are also populated by a wide variety of reptiles, fish, butterflies, and other creatures adapted to particular niches of a mountainous semi-desert terrain.

Geography

The John Day Fossil Beds National Monument consists of three widely separated units—Sheep Rock, Painted Hills, and Clarno—in theJohn Day River

The John Day River is a tributary of the Columbia River, approximately long, in northeastern Oregon in the United States. It is known as the Mah-Hah River by the Cayuse people. Undammed along its entire length, the river is the fourth longest ...

basin of east-central Oregon. Located in rugged terrain in the counties of Wheeler and Grant, the park units are characterized by hills, deep ravines, and eroded fossil-bearing rock formations. To the west lies the Cascade Range

The Cascade Range or Cascades is a major mountain range of western North America, extending from southern British Columbia through Washington (state), Washington and Oregon to Northern California. It includes both non-volcanic mountains, such as m ...

, to the south the Ochoco Mountains, and to the east the Blue Mountains. Elevations within the park range from .

The Clarno Unit, the westernmost of the three units, consists of located west of

The Clarno Unit, the westernmost of the three units, consists of located west of Fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserve ...

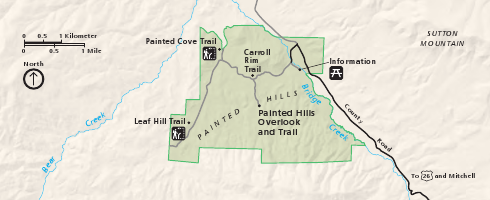

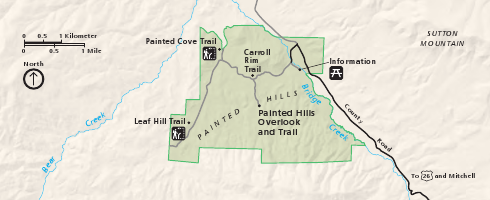

along Oregon Route 218. The Painted Hills Unit, which lies about halfway between the other two, covers . It is situated about northwest of Mitchell along Burnt Ranch Road, which intersects U.S. Route 26 west of Mitchell. These two units are entirely within Wheeler County. The remaining of the park, the Sheep Rock Unit, are located along Oregon Route 19 and the John Day River upstream of the unincorporated community of Kimberly. This unit is mostly in Grant County; a small part extends into Wheeler County. The Sheep Rock Unit is further subdivided into the Mascall Formation Overlook, Picture Gorge, the James Cant Ranch Historic District, Cathedral Rock, Blue Basin, and the Foree Area. Some of these are separated from one another by farms, ranches, and other parcels of land that are not part of the park.

The park headquarters and main visitor center, both in the Sheep Rock Unit, are northeast of Bend and southeast of

The park headquarters and main visitor center, both in the Sheep Rock Unit, are northeast of Bend and southeast of Portland

Portland most commonly refers to:

*Portland, Oregon, the most populous city in the U.S. state of Oregon

*Portland, Maine, the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maine

*Isle of Portland, a tied island in the English Channel

Portland may also r ...

by highway. The shortest highway distances from unit to unit within the park are Sheep Rock to Painted Hills, ; Painted Hills to Clarno, , and Clarno to Sheep Rock, .

The John Day River, a tributary of the Columbia River

The Columbia River (Upper Chinook language, Upper Chinook: ' or '; Sahaptin language, Sahaptin: ''Nch’i-Wàna'' or ''Nchi wana''; Sinixt dialect'' '') is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river headwater ...

, flows generally west from the Strawberry Mountains before reaching the national monument. It turns sharply north between the Mascall Formation Overlook and Kimberly, where the North Fork John Day River joins the main stem

In hydrology, a main stem or mainstem (also known as a trunk) is "the primary downstream segment of a river, as contrasted to its tributaries". The mainstem extends all the way from one specific headwater to the outlet of the river, although t ...

. Downstream of Kimberly, the river flows generally west to downstream of the unincorporated community of Twickenham

Twickenham ( ) is a suburban district of London, England, on the River Thames southwest of Charing Cross. Historic counties of England, Historically in Middlesex, since 1965 it has formed part of the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, who ...

, and generally north thereafter. Rock Creek enters the river at the north end of Picture Gorge. Bridge Creek passes through Mitchell, then north along the eastern edge of the Painted Hills Unit to meet the John Day downstream of Twickenham. Intermittent streams in the Clarno Unit empty into Pine Creek, which flows just beyond the south edge of the unit and enters the John Day upstream of the unincorporated community of Clarno.

History

Early inhabitants of north-central Oregon included Sahaptin-speaking people of the Umatilla, Wasco, and Warm Springs tribes as well as the

Early inhabitants of north-central Oregon included Sahaptin-speaking people of the Umatilla, Wasco, and Warm Springs tribes as well as the Northern Paiute

Northern may refer to the following:

Geography

* North, a point in direction

* Northern Europe, the northern part or region of Europe

* Northern Highland, a region of Wisconsin, United States

* Northern Province, Sri Lanka

* Northern Range, a ...

s, speakers of a Uto-Aztecan (Shoshonean) language. All were hunter-gatherer

A hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living in a community, or according to an ancestrally derived Lifestyle, lifestyle, in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local naturally occurring sources, esp ...

s competing for resources such as elk, huckleberries

Huckleberry is a name used in North America for several plants in the family Ericaceae, in two closely related genera: ''Vaccinium'' and ''Gaylussacia''.

Nomenclature

The name 'huckleberry' is a North American variation of the English dialectal ...

, and salmon

Salmon (; : salmon) are any of several list of commercially important fish species, commercially important species of euryhaline ray-finned fish from the genera ''Salmo'' and ''Oncorhynchus'' of the family (biology), family Salmonidae, native ...

. Researchers have identified 36 sites of related archeological interest, including rock shelters and cairn

A cairn is a human-made pile (or stack) of stones raised for a purpose, usually as a marker or as a burial mound. The word ''cairn'' comes from the (plural ).

Cairns have been and are used for a broad variety of purposes. In prehistory, t ...

s, in or adjacent to the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument. Most significant among the prehistoric sites are the Picture Gorge pictographs

A pictogram (also pictogramme, pictograph, or simply picto) is a graphical symbol that conveys meaning through its visual resemblance to a physical object. Pictograms are used in systems of writing and visual communication. A pictography is a wri ...

, consisting of six panels of rock art in the canyon at the south end of the Sheep Rock Unit. The art is of undetermined origin and age but is "centuries old".

The John Day basin remained largely unexplored by non-natives until the mid-19th century.

The John Day basin remained largely unexplored by non-natives until the mid-19th century. Lewis and Clark

Lewis may refer to:

Names

* Lewis (given name), including a list of people with the given name

* Lewis (surname), including a list of people with the surname

Music

* Lewis (musician), Canadian singer

* " Lewis (Mistreated)", a song by Radiohe ...

noted but did not explore the John Day River while traveling along the Columbia River in 1805. John Day, for whom the river is named, apparently visited only its confluence with the Columbia in 1812. In 1829, Peter Skene Ogden

Peter Skene Ogden (alternately Skeene, Skein, or Skeen; baptised 12 February 1790 – 27 September 1854) was a British-Canadian fur trader and an early explorer of what is now British Columbia and the Western United States. During his many exped ...

, working for the Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), originally the Governor and Company of Adventurers of England Trading Into Hudson’s Bay, is a Canadian holding company of department stores, and the oldest corporation in North America. It was the owner of the ...

(HBC), led a company of explorers and fur trappers along the river through what would later become the Sheep Rock Unit. John Work, also of the HBC, visited this part of the river in 1831.

In the 1840s, thousands of settlers, attracted in part by the lure of free land, began emigrating west over the Oregon Trail

The Oregon Trail was a east–west, large-wheeled wagon route and Westward Expansion Trails, emigrant trail in North America that connected the Missouri River to valleys in Oregon Territory. The eastern part of the Oregon Trail crossed what ...

. Leaving drought, worn-out farms, and economic problems behind, they emigrated from states like Missouri, Illinois, and Iowa in the Midwest

The Midwestern United States (also referred to as the Midwest, the Heartland or the American Midwest) is one of the four census regions defined by the United States Census Bureau. It occupies the northern central part of the United States. It ...

to Oregon, especially the Willamette Valley

The Willamette Valley ( ) is a valley in Oregon, in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. The Willamette River flows the entire length of the valley and is surrounded by mountains on three sides: the Cascade Range to the east, the ...

in the western part of the state. After passage of the Homestead Act

The Homestead Acts were several laws in the United States by which an applicant could acquire ownership of Federal lands, government land or the American frontier, public domain, typically called a Homestead (buildings), homestead. In all, mo ...

of 1862 and the discovery of gold in the upper John Day basin, a fraction of these newcomers abandoned the Willamette Valley in favor of eastern Oregon. Some established villages and engaged in subsistence farming and ranching near streams. Settlement was made more practical by a supply route from The Dalles on the Columbia River to gold mines at Canyon City in the upper John Day valley. By the late 1860s, the route became formalized as The Dalles Military Road, which passed along Bridge Creek and south of Sheep Rock. Clashes between natives and non-natives and the desire of the U.S. Government to populate the region with Euro-Americans led to the gradual removal of native residents to reservations, including three in north-central Oregon: Warm Springs, Burns Paiute, and Umatilla.

In 1864, a company of soldiers sent to protect mining camps from raids by Northern Paiutes discovered fossils in the Crooked River region, south of the John Day basin. One of their leaders, Captain John M. Drake, collected some of these fossils for

In 1864, a company of soldiers sent to protect mining camps from raids by Northern Paiutes discovered fossils in the Crooked River region, south of the John Day basin. One of their leaders, Captain John M. Drake, collected some of these fossils for Thomas Condon

Thomas Condon (1822–1907) was an Irish Congregational church, Congregational minister, geologist, and paleontology, paleontologist who gained recognition for his work in the U.S. state of Oregon.

Life and career

Condon arrived in New York Cit ...

, a missionary pastor and amateur geologist who lived in The Dalles. Recognizing the scientific importance of the fossils, Condon accompanied soldiers traveling through the region. He discovered rich fossil beds along Bridge Creek and near Sheep Rock in 1865. Condon's trips to the area and his public lectures and reports about his finds led to wide interest in the fossil beds among scientists such as Edward Drinker Cope

Edward Drinker Cope (July 28, 1840 – April 12, 1897) was an American zoologist, paleontology, paleontologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist, herpetology, herpetologist, and ichthyology, ichthyologist. Born to a wealthy Quaker fam ...

of the Academy of Natural Sciences

The Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, formerly the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, is the oldest natural science research institution and museum in the Americas. It was founded in 1812, by many of the leading natur ...

. One of them, paleontologist Othniel C. Marsh of Yale

Yale University is a private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701, Yale is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States, and one of the nine colonial colleges ch ...

, accompanied Condon on a trip to the region in 1871. Condon's work led to his appointment in 1872 as Oregon's first state geologist and to international fame for the fossil beds. Specimens from the beds were sent to the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums, Education center, education and Research institute, research centers, created by the Federal government of the United States, U.S. government "for the increase a ...

and other museums worldwide, and by 1900 more than 100 articles and books had been published about the John Day Fossil Beds. During the first half of the 20th century, scientists such as John C. Merriam, Ralph Chaney, Frank H. Knowlton, and Alonzo W. Hancock continued work in the fossil beds, including those discovered near Clarno in about 1890.

Remote and arid, the John Day basin near the fossil beds was slow to attract homesteaders. The first settler in what became the Sheep Rock Unit is thought to have been Frank Butler, who built a cabin along the river in 1877. In 1881, Eli Casey Officer began grazing sheep on a homestead claim in same general area. His son Floyd later lived there with his family and sometimes accompanied Condon on his fossil hunts. In 1910, James and Elizabeth Cant bought from the Officer family. and converted it to a sheep ranch, which was eventually expanded to a sheep-and-cattle ranch of about .

Merriam, a

Merriam, a University of California

The University of California (UC) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university, research university system in the U.S. state of California. Headquartered in Oakland, California, Oakland, the system is co ...

paleontologist who had led expeditions to the region in 1899 and 1900, encouraged the State of Oregon to protect the area. In the early 1930s the state began to buy land for state parks at Picture Gorge, the Painted Hills, and Clarno that later became part of the national monument. In 1951 the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry

The Oregon Museum of Science and Industry (OMSI, ) is a science and technology museum in Portland, Oregon, United States. It contains three auditoriums, including a large-screen theatre, planetarium, and exhibition halls with a variety of hands- ...

established Camp Hancock, a field school for young students of geology, paleontology, and other sciences, on public lands surrounded by what would later become the Clarno Unit. In 1974 Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

authorized the National Park Service to establish the national monument, and President Gerald R. Ford

Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr. (born Leslie Lynch King Jr.; July 14, 1913December 26, 2006) was the 38th president of the United States, serving from 1974 to 1977. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, Ford assumed the p ...

signed the authorization. After the State of Oregon had completed the land transfer of the three state parks to the federal government, the monument was officially established on October 8, 1975.

The Cant Ranch House and associated land and outbuildings were listed on the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government's official United States National Register of Historic Places listings, list of sites, buildings, structures, Hist ...

as the James Cant Ranch Historic District in 1984. After the monument opened in 1975, the ranch house served as headquarters for all three units. In 2005, the lower floor of the ranch house was opened to the public; it features exhibits about the cultural history of the region. The Thomas Condon Paleontology Center, a $7.5 million museum and visitor center at the Sheep Rock Unit, also opened in 2005. Among the center's offerings are displays of fossils, murals depicting life in the basin during eight geologic times ranging from about 45 million to about 5 million years ago, and views of the paleontology laboratory.

In March 2011, the Park Service installed two webcams

A webcam is a video camera which is designed to record or stream to a computer or computer network. They are primarily used in Videotelephony, video telephony, live streaming and social media, and Closed-circuit television, security. Webcams can b ...

at the Sheep Rock Unit. Both transmit continuous real-time images; one shows the paleontology lab at the Condon Center and the other depicts Sheep Rock and nearby features. In June 2011, work was finished on a new ranger residence in the Painted Hills Unit that makes the unit almost carbon-neutral

Global net-zero emissions is reached when greenhouse gas emissions and Greenhouse gas removal, removals due to human activities are in balance. It is often called simply net zero. ''Emissions'' can refer to all greenhouse gases or only carbon diox ...

. Solar panels generate enough electricity to power the house as well as the ranger's electric vehicle, on loan from its manufacturer for a year. The project is part of ongoing efforts to make the whole park carbon-neutral.

Geology and paleontology

The John Day Fossil Beds National Monument lies within the Blue Mountains

The John Day Fossil Beds National Monument lies within the Blue Mountains physiographic province

physiographic province is a geographic region with a characteristic geomorphology, and often specific subsurface rock type or structural elements. The continents are subdivided into various physiographic provinces, each having a specific characte ...

, which originated during the late Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately 143.1 Mya. ...

and early Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 143.1 to 66 mya (unit), million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era (geology), Era, as well as the longest. At around 77.1 million years, it is the ...

, about 118 to 93 million years ago. Northeastern Oregon was assembled in large blocks (exotic terrane

In geology, a terrane (; in full, a tectonostratigraphic terrane) is a crust fragment formed on a tectonic plate (or broken off from it) and accreted or " sutured" to crust lying on another plate. The crustal block or fragment preserves its d ...

s) of Permian

The Permian ( ) is a geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system which spans 47 million years, from the end of the Carboniferous Period million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Triassic Period 251.902 Mya. It is the s ...

, Triassic

The Triassic ( ; sometimes symbolized 🝈) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.5 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.4 Mya. The Triassic is t ...

, and Jurassic rock shifted by tectonic

Tectonics ( via Latin ) are the processes that result in the structure and properties of the Earth's crust and its evolution through time. The field of ''planetary tectonics'' extends the concept to other planets and moons.

These processes ...

forces and accreted to what was then the western edge of the North American continent, near the Idaho border. By the beginning of the Cenozoic

The Cenozoic Era ( ; ) is Earth's current geological era, representing the last 66million years of Earth's history. It is characterized by the dominance of mammals, insects, birds and angiosperms (flowering plants). It is the latest of three g ...

era, 66 million years ago, the Blue Mountains province was uplifting (that is, was being pushed higher by tectonic forces), and the Pacific Ocean shoreline, formerly near Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest and Mountain states, Mountain West subregions of the Western United States. It borders Montana and Wyoming to the east, Nevada and Utah to the south, and Washington (state), ...

, had shifted to the west.

Volcanic eruptions about 44 million years ago during the Eocene

The Eocene ( ) is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (Ma). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene'' comes ...

deposited lavas accompanied by debris flows (lahar

A lahar (, from ) is a violent type of mudflow or debris flow composed of a slurry of Pyroclastic rock, pyroclastic material, rocky debris and water. The material flows down from a volcano, typically along a valley, river valley.

Lahars are o ...

s) atop the older rocks in the western part of the province. Containing fragments of shale

Shale is a fine-grained, clastic sedimentary rock formed from mud that is a mix of flakes of Clay mineral, clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g., Kaolinite, kaolin, aluminium, Al2Silicon, Si2Oxygen, O5(hydroxide, OH)4) and tiny f ...

, siltstone

Siltstone, also known as aleurolite, is a clastic sedimentary rock that is composed mostly of silt. It is a form of mudrock with a low clay mineral content, which can be distinguished from shale by its lack of fissility.

Although its permeabil ...

, conglomerates, and breccia

Breccia ( , ; ) is a rock composed of large angular broken fragments of minerals or Rock (geology), rocks cementation (geology), cemented together by a fine-grained matrix (geology), matrix.

The word has its origins in the Italian language ...

s, the debris flows entombed plants and animals caught in their paths; the remnants of these ancient flows comprise the rock formations exposed in the Clarno Unit. Preserved in the Clarno Nut Beds are fossils of tropical and subtropical nuts, fruits, roots, branches, and seeds. The Clarno Formation also contains bones, palm leaves longer than , avocado trees, and other subtropical plants from 50 million years ago, when the climate was warmer and wetter than it is in the 21st century. Large mammals that inhabited this region between 50 and 35 million years ago included browsers

Browse, browser, or browsing may refer to:

Computing

*Browser service, a feature of Microsoft Windows to browse shared network resources

*Code browser, a program for navigating source code

*File browser or file manager, a program used to manage f ...

such as brontotheres and amynodonts, scavengers like the hyaenodonts

Hyaenodontidae ("hyena teeth") is a family of placental mammals in the extinct superfamily Hyaenodontoidea. Hyaenodontids arose during the early Eocene and persisted well into the early Miocene. Fossils of this group have been found in Asia, Nor ...

, as well as '' Patriofelis'' and other predators. Eroded remnants of the Clarno stratovolcano

A stratovolcano, also known as a composite volcano, is a typically conical volcano built up by many alternating layers (strata) of hardened lava and tephra. Unlike shield volcanoes, stratovolcanoes are characterized by a steep profile with ...

es, once the size of Mount Hood

Mount Hood, also known as Wy'east, is an active stratovolcano in the Cascade Range and is a member of the Cascade Volcanic Arc. It was formed by a subduction zone on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast and rests in the Pacific N ...

, are still visible near the monument, for example Black Butte, White Butte, and other butte

In geomorphology, a butte ( ) is an isolated hill with steep, often vertical sides and a small, relatively flat top; buttes are smaller landforms than mesas, plateaus, and table (landform), tablelands. The word ''butte'' comes from the French l ...

s near Mitchell.

After the Clarno volcanoes had subsided, they were replaced about 36 million years ago by eruptions from volcanoes to the west, in the general vicinity of what would become the Cascade Range. The John Day volcanoes, as they are called, emitted large volumes of ash and dust, much of which settled in the John Day basin. As with the earlier Clarno debris flows, the rapid deposition of ash preserved the remains of plants and animals living in the region. Because ash and other debris fell during varied climatic and volcanic conditions and accumulated from many further eruptions extending into the early Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first epoch (geology), geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and mea ...

(about 20 million years ago), the sediment layers in the fossil beds vary in their chemical composition and color. Laid down on top of the Clarno Strata, the younger John Day Strata consist of several distinct groups of layers. The lowermost contains red ash such as that exposed in the Painted Hills Unit. The layer above it is mainly pea-green clay. On top of the pea-green layer are buff-colored layers. Fossils found in the John Day Strata include a wide variety of plants and more than 100 species of mammals, including dogs, cats, oreodonts, saber-toothed tigers, horses, camels, and rodents. The Blue Basin and the Sheep Rock unit contain many of these same fossils, as well as turtles, opossums, and large pigs. More than 60 plant species are fossilized in these strata, such as ''hydrangea

''Hydrangea'' ( or ) is a genus of more than 70 species of Flowering plant, flowering plants native plant, native to Asia and the Americas. Hydrangea is also used as the common name for the genus; some (particularly ''Hydrangea macrophylla, H. m ...

'', pea

Pea (''pisum'' in Latin) is a pulse or fodder crop, but the word often refers to the seed or sometimes the pod of this flowering plant species. Peas are eaten as a vegetable. Carl Linnaeus gave the species the scientific name ''Pisum sativum' ...

s, hawthorn, and mulberry

''Morus'', a genus of flowering plants in the family Moraceae, consists of 19 species of deciduous trees commonly known as mulberries, growing wild and under cultivation in many temperate world regions. Generally, the genus has 64 subordinat ...

, as well as pine

A pine is any conifer tree or shrub in the genus ''Pinus'' () of the family Pinaceae. ''Pinus'' is the sole genus in the subfamily Pinoideae.

''World Flora Online'' accepts 134 species-rank taxa (119 species and 15 nothospecies) of pines as cu ...

s and many deciduous trees. One of the notable plant fossils is the '' Metasequoia'' (dawn redwood), a genus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

thought to have gone extinct worldwide until it was discovered alive in China in the early 20th century.

After another period of erosion, a series of lava

Lava is molten or partially molten rock (magma) that has been expelled from the interior of a terrestrial planet (such as Earth) or a Natural satellite, moon onto its surface. Lava may be erupted at a volcano or through a Fissure vent, fractu ...

eruptions from fissures across northeastern Oregon, southeastern Washington, and western Idaho inundated much of the Blue Mountain province with liquid basalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanite, aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the planetary surface, surface of a terrestrial ...

. Extruded in the middle Miocene between 17 and 12 million years ago, more than 40 separate flows contributing to the Columbia River Basalt Group

The Columbia River Basalt Group (CRBG) is the youngest, smallest and one of the best-preserved continental flood basalt provinces on Earth, covering over mainly eastern Oregon and Washington, western Idaho, and part of northern Nevada. The b ...

have been identified, the largest of which involved up to of lava. The most prominent of these formations within the monument is the Picture Gorge Basalt, which rests above the John Day Strata.

Subsequent ashfall from eruptions in the Cascade Range in the late Miocene contributed to the Mascall Formation, layers of stream-deposited volcanic tuff

Tuff is a type of rock made of volcanic ash ejected from a vent during a volcanic eruption. Following ejection and deposition, the ash is lithified into a solid rock. Rock that contains greater than 75% ash is considered tuff, while rock co ...

s laid atop the Picture Gorge Basalt. Preserved in the Mascall are fossils of animals such as horses, camels, rhinoceroses, bears, pronghorn

The pronghorn (, ) (''Antilocapra americana'') is a species of artiodactyl (even-toed, hoofed) mammal indigenous to interior western and central North America. Though not an antelope, it is known colloquially in North America as the American ante ...

, deer, weasels, raccoons, cats, dogs, and sloths. These fauna thrived in the monument's open woodland and savannah between 15 and 12 million years ago. The fossils of oak, sycamore, maple, ginkgo, and elm trees reflect the area's cool climate during this time period.

The last major eruption occurred in the late Miocene, about 7 million years ago. The resulting stratum, the Rattlesnake Formation, lies on top of the Mascall and contains an ignimbrite

Ignimbrite is a type of volcanic rock, consisting of hardened tuff. Ignimbrites form from the deposits of pyroclastic flows, which are a hot suspension of particles and gases flowing rapidly from a volcano, driven by being denser than the surrou ...

. The Rattlesnake stratum has fossils of mastodon

A mastodon, from Ancient Greek μαστός (''mastós''), meaning "breast", and ὀδούς (''odoús'') "tooth", is a member of the genus ''Mammut'' (German for 'mammoth'), which was endemic to North America and lived from the late Miocene to ...

s, camels, rhinoceroses, the ancestors of dogs, lions, bears, and horses, and others that grazed on the grasslands of the time.

Two fossilized teeth found recently in the Rattlesnake stratum near Dayville are the earliest record of beaver

Beavers (genus ''Castor'') are large, semiaquatic rodents of the Northern Hemisphere. There are two existing species: the North American beaver (''Castor canadensis'') and the Eurasian beaver (''C. fiber''). Beavers are the second-large ...

, ''Castor californicus

''Castor californicus'' is an extinct species of beaver that lived in western North America from the end of the Miocene to the early Pleistocene. ''Castor californicus'' was first discovered in the Kettleman Hills of California, United States. ...

'', in North America. The beaver teeth, which are about 7 million years old, have been scheduled for display at the Condon Center.

The monument contains extensive deposits of well-preserved fossils from various periods spanning more than 40 million years. Taken as a whole, the fossils present an unusually detailed view of plants and animals since the late Eocene. In addition, analysis of the John Day fossils has contributed to

The monument contains extensive deposits of well-preserved fossils from various periods spanning more than 40 million years. Taken as a whole, the fossils present an unusually detailed view of plants and animals since the late Eocene. In addition, analysis of the John Day fossils has contributed to paleoclimatology

Paleoclimatology ( British spelling, palaeoclimatology) is the scientific study of climates predating the invention of meteorological instruments, when no direct measurement data were available. As instrumental records only span a tiny part of ...

(the study of Earth's past climates) and the study of evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

.

Paleontologists at the monument find, describe the location of, and collect fossil-bearing rocks from more than 700 sites. They take them to the paleontology laboratory at the visitor center, where the fossils are stabilized, separated from their rock matrix

Matrix (: matrices or matrixes) or MATRIX may refer to:

Science and mathematics

* Matrix (mathematics), a rectangular array of numbers, symbols or expressions

* Matrix (logic), part of a formula in prenex normal form

* Matrix (biology), the m ...

, and cleaned. The fossil specimens are then catalogued, indexed, stored in climate-controlled cabinets, and made available for research. In addition to preparing fossils, the paleontologists coordinate the monument's basic research in paleobotany

Paleobotany or palaeobotany, also known as paleophytology, is the branch of botany dealing with the recovery and identification of plant fossils from geological contexts, and their use for the biological reconstruction of past environments ( pal ...

and other scientific areas and manage the fossil museum in the visitor center.

Climate

Average precipitation, limited by therain shadow

A rain shadow is an area of significantly reduced rainfall behind a mountainous region, on the side facing away from prevailing winds, known as its leeward side.

Evaporated moisture from body of water, bodies of water (such as oceans and larg ...

effects of the Cascade Range and the Ochoco Mountains, varies from a year. In winter, much of the precipitation arrives as snow.

Weather data for the city of Mitchell, near the Painted Hills Unit, show that July and August are the warmest months, with an average high of and an average low of . January is the coldest month, when highs average and lows average . The highest recorded temperature in Mitchell was in 1972, and the lowest was in 1983. May is generally the wettest month, when precipitation averages .

Biology

Flora

More than 80 soil types support a wide variety of flora within the monument. These soils stem from past and present geologic activity as well as ongoing additions of organic matter from life forms on or near the surface. Adapted to particular soil types and surface conditions, these plant communities range from

More than 80 soil types support a wide variety of flora within the monument. These soils stem from past and present geologic activity as well as ongoing additions of organic matter from life forms on or near the surface. Adapted to particular soil types and surface conditions, these plant communities range from riparian

A riparian zone or riparian area is the interface between land and a river or stream. In some regions, the terms riparian woodland, riparian forest, riparian buffer zone, riparian corridor, and riparian strip are used to characterize a ripar ...

vegetation near the river to greasewood

Greasewood is a common name shared by several plants:

* ''Adenostoma fasciculatum'' is a plant with white flowers that is native to Oregon, Nevada, California, and northern Baja California. This shrub is one of the most widespread plants of the ...

and saltgrass on the alluvial fan

An alluvial fan is an accumulation of sediments that fans outwards from a concentrated source of sediments, such as a narrow canyon emerging from an escarpment. They are characteristic of mountainous terrain in arid to Semi-arid climate, semiar ...

s to plants such as hedgehog cactus in rocky outcrops at high elevation. Important to many of these communities is a black cryptobiotic crust that resists erosion, stores water, and fixes nitrogen used by the plants. The crust is composed of algae, lichens, mosses, fungi, and bacteria. Other areas of the monument have little or no flora. Volcanic tuffs and claystones that lack essential nutrients support few microorganisms and plants. Likewise, hard rock surfaces and steep slopes from which soils wash or blow away tend to remain bare.

Native grasses thrive in many parts of the monument despite competition from medusahead rye, Dalmatian toadflax, cheatgrass, and other invasive species. Bunchgrasses in the park include basin wildrye, Idaho fescue, Thurber's needlegrass, Indian ricegrass, and bottlebrush squirreltail, among others. Native grasses that form sod

Sod is the upper layer of turf that is harvested for transplanting. Turf consists of a variable thickness of a soil medium that supports a community of turfgrasses.

In British and Australian English, sod is more commonly known as ''turf'', ...

in parts of the monument include Sandberg's bluegrass and other bluegrass species. Reed canary grass, if mowed, also forms sod along stream banks.

Limited by their need for water, trees such as willow

Willows, also called sallows and osiers, of the genus ''Salix'', comprise around 350 species (plus numerous hybrids) of typically deciduous trees and shrubs, found primarily on moist soils in cold and temperate regions.

Most species are known ...

s, alder

Alders are trees of the genus ''Alnus'' in the birch family Betulaceae. The genus includes about 35 species of monoecious trees and shrubs, a few reaching a large size, distributed throughout the north temperate zone with a few species ex ...

s, and ponderosa pines are found only near the monument's streams or springs. Serviceberry bushes and shrubs like mountain mahogany

''Cercocarpus'', commonly known as mountain mahogany, is a small genus of at least nine species of nitrogen-fixing flowering plants in the rose family, Rosaceae. They are native to the western United States and northern Mexico, where they grow i ...

are found in places where moisture collects near rock slides and ledges. Elsewhere long-rooted rabbitbrush has adapted to survive in dry areas. Other shrubs with adaptive properties include greasewood, sagebrush

Sagebrush is the common name of several woody and herbaceous species of plants in the genus ''Artemisia (plant), Artemisia''. The best-known sagebrush is the shrub ''Artemisia tridentata''. Sagebrush is native to the western half of North Amer ...

, shadscale

''Atriplex confertifolia'', the shadscale or spiny saltbush, is a species of evergreen shrub in the family Amaranthaceae, which is native to the western United States and northern Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a c ...

, broom snakeweed, antelope bitterbrush, and purple sage. Western junipers, which have extensive root systems, thrive in the dry climate; in the absence of periodic fires they tend to displace grasses and sagebrush and to create relatively barren landscapes. The Park Service is considering controlled burning to limit the junipers and to create open areas for bunchgrasses that re-sprout from their roots after a fire.

Wildflowers, which bloom mainly in the spring and early summer, include pincushions, golden bee plant, dwarf purple monkey flower, and sagebrush mariposa lily at the Painted Hills Unit. Munro's globemallow, lupines, yellow fritillary, hedgehog cactus, and Applegate's Indian paintbrush are commonly seen at the Clarno and Sheep Rock units.

Fauna

Birds are the animals most often seen in the monument. Included among the more than 50 species observed are

Birds are the animals most often seen in the monument. Included among the more than 50 species observed are red-tailed hawk

The red-tailed hawk (''Buteo jamaicensis'') is a bird of prey that breeds throughout most of North America, from the interior of Alaska and northern Canada to as far south as Panama and the West Indies. It is one of the most common members of ...

s, American kestrel

The American kestrel (''Falco sparverius'') is the smallest and most common falcon in North America. Though it has been called the American sparrowhawk, this common name is a misnomer; the American kestrel is a true falcon, while neither th ...

s, great horned owl

The great horned owl (''Bubo virginianus''), also known as the tiger owl (originally derived from early naturalists' description as the "winged tiger" or "tiger of the air") or the hoot owl, is a large owl native to the Americas. It is an extreme ...

s, common nighthawk

The common nighthawk or bullbat (''Chordeiles minor'') is a medium-sized crepuscular or nocturnal bird of the Americas within the nightjar (Caprimulgidae) family, whose presence and identity are best revealed by its vocalization. Typically dark ...

s, and great blue heron

The great blue heron (''Ardea herodias'') is a large wading bird in the heron family Ardeidae, common near the shores of open water and in wetlands over most of North and Central America, as well as far northwestern South America, the Caribbea ...

s. Geese nest in the park each summer, and flocks of sandhill crane

The sandhill crane (''Antigone canadensis'') is a species of large Crane (bird), cranes of North America and extreme northeastern Siberia. The common name of this bird refers to its habitat, such as the Platte River, on the edge of Nebraska's S ...

s and swans pass overhead each year on their migratory flights. California quail, chukar partridge

The chukar partridge (''Alectoris chukar''), or simply chukar, is a Palearctic upland Upland game, gamebird in the pheasant family Phasianidae. It has been considered to form a superspecies complex along with the rock partridge, Philby's partrid ...

s, and mourning dove

The mourning dove (''Zenaida macroura'') is a member of the dove Family (biology), family, Columbidae. The bird is also known as the American mourning dove, the rain dove, the chueybird, colloquially as the turtle dove, and it was once known a ...

s are also common. Others seen near the Cant Ranch and the visitor center include rufous hummingbirds, Say's phoebe

Say's phoebe (''Sayornis saya'') is a passerine bird in the tyrant flycatcher family, Tyrannidae. A common bird across western North America, it prefers dry, desolate areas. It was named for Thomas Say, an American naturalist.

Taxonomy

Say's pho ...

, yellow warblers, western meadowlark

The western meadowlark (''Sturnella neglecta'') is a medium-sized icterid bird, about in length. It is found across western and central North America and is a Bird migration, full migrant, breeding in Canada and the United States with resident ...

s, and American goldfinch

The American goldfinch (''Spinus tristis'') is a small North American bird in the finch Family (biology), family. It is Bird migration, migratory, ranging from mid-Alberta to North Carolina during the breeding season, and from just south of th ...

es. Visitors on trails may encounter canyon wrens, mountain bluebirds, mountain chickadees, black-billed magpie

The black-billed magpie (''Pica hudsonia''), also known as the American magpie, is a bird in the corvid family found in the western half of North America. It is black and white, with the wings and tail showing black areas and iridescent hints ...

s, and other birds.

Large animals that frequent the park include elk

The elk (: ''elk'' or ''elks''; ''Cervus canadensis'') or wapiti, is the second largest species within the deer family, Cervidae, and one of the largest terrestrial mammals in its native range of North America and Central and East Asia. ...

, deer, cougar

The cougar (''Puma concolor'') (, ''Help:Pronunciation respelling key, KOO-gər''), also called puma, mountain lion, catamount and panther is a large small cat native to the Americas. It inhabits North America, North, Central America, Cent ...

, and pronghorn

The pronghorn (, ) (''Antilocapra americana'') is a species of artiodactyl (even-toed, hoofed) mammal indigenous to interior western and central North America. Though not an antelope, it is known colloquially in North America as the American ante ...

. Beaver

Beavers (genus ''Castor'') are large, semiaquatic rodents of the Northern Hemisphere. There are two existing species: the North American beaver (''Castor canadensis'') and the Eurasian beaver (''C. fiber''). Beavers are the second-large ...

, otter

Otters are carnivorous mammals in the subfamily Lutrinae. The 13 extant otter species are all semiaquatic, aquatic, or marine. Lutrinae is a branch of the Mustelidae family, which includes weasels, badgers, mink, and wolverines, among ...

, mink

Mink are dark-colored, semiaquatic, carnivorous mammals of the genera ''Neogale'' and '' Mustela'' and part of the family Mustelidae, which also includes weasels, otters, and ferrets. There are two extant species referred to as "mink": the A ...

, and raccoon

The raccoon ( or , ''Procyon lotor''), sometimes called the North American, northern or common raccoon (also spelled racoon) to distinguish it from Procyonina, other species of raccoon, is a mammal native to North America. It is the largest ...

s are found in or near the river. Coyote

The coyote (''Canis latrans''), also known as the American jackal, prairie wolf, or brush wolf, is a species of canis, canine native to North America. It is smaller than its close relative, the Wolf, gray wolf, and slightly smaller than the c ...

s, bats, and badger

Badgers are medium-sized short-legged omnivores in the superfamily Musteloidea. Badgers are a polyphyletic rather than a natural taxonomic grouping, being united by their squat bodies and adaptions for fossorial activity rather than by the ...

s are among the park's other mammals. Predators hunt smaller animals such as the rabbits, vole

Voles are small rodents that are relatives of lemmings and hamsters, but with a stouter body; a longer, hairy tail; a slightly rounder head; smaller eyes and ears; and differently formed molars (high-crowned with angular cusps instead of lo ...

s, mice, and shrew

Shrews ( family Soricidae) are small mole-like mammals classified in the order Eulipotyphla. True shrews are not to be confused with treeshrews, otter shrews, elephant shrews, West Indies shrews, or marsupial shrews, which belong to dif ...

s found in the park's grasslands and sagebrush-covered hills. Bushy-tailed woodrat

The bushy-tailed woodrat, or packrat (''Neotoma cinerea'') is a species of rodent in the family Cricetidae found in Canada and the United States.

Its natural habitats are boreal forests, temperate forests, dry savanna, temperate shrubland, and te ...

s inhabit caves and crevices in the monument's rock formations. Bighorn sheep

The bighorn sheep (''Ovis canadensis'') is a species of Ovis, sheep native to North America. It is named for its large Horn (anatomy), horns. A pair of horns may weigh up to ; the sheep typically weigh up to . Recent genetic testing indicates th ...

, wiped out in this region in the early 20th century, were reintroduced in the Foree Area of the Sheep Rock Unit in 2010.

Many habitats in the monument support populations of snakes and lizards. Southern alligator and western fence lizards are common; others that live here include short-horned and common side-blotched lizards and western skinks. Garter and gopher

Pocket gophers, commonly referred to simply as gophers, are burrowing rodents of the family Geomyidae. The roughly 41 speciesSearch results for "Geomyidae" on thASM Mammal Diversity Database are all endemic to North and Central America. They ar ...

snakes and western yellow-bellied racers frequent floodplains and canyon bottoms. Rattlesnakes, though venomous, are shy and usually flee before being seen. The springs and seeps in the park contain isolated populations of western toad

The western toad (''Anaxyrus boreas'') is a large toad species, between long, native to western North America. ''A. boreas'' is frequently encountered during the wet season on roads, or near water at other times. It can jump a considerable dista ...

s, American spadefoot toad

The Scaphiopodidae are a family of American spadefoot toads, which are native to North America. The family is small, comprising only eleven different species.

The American spadefoot toads are of typical shape to most fossorial (or burrowing) fr ...

s, Pacific tree frogs, and long-toed salamanders.

A 2003–04 survey of the monument found 55 species of butterflies such as the common sootywing, orange sulphur, great spangled fritillary, and

A 2003–04 survey of the monument found 55 species of butterflies such as the common sootywing, orange sulphur, great spangled fritillary, and monarch

A monarch () is a head of stateWebster's II New College Dictionary. "Monarch". Houghton Mifflin. Boston. 2001. p. 707. Life tenure, for life or until abdication, and therefore the head of state of a monarchy. A monarch may exercise the highest ...

. The monument's other insects have not been completely inventoried.

The John Day River, which passes through the Sheep Rock Unit, is the longest undammed tributary of the Columbia River, although two Columbia River dams below the John Day River mouth impede migratory fish travel to some degree. Chinook salmon

The Chinook salmon (''Oncorhynchus tshawytscha'') is the largest and most valuable species of Oncorhynchus, Pacific salmon. Its common name is derived from the Chinookan peoples. Other vernacular names for the species include king salmon, quinn ...

and steelhead

Steelhead, or occasionally steelhead trout, is the Fish migration#Classification, anadromous form of the coastal rainbow trout or Columbia River redband trout (''O. m. gairdneri'', also called redband steelhead). Steelhead are native to cold-wa ...

pass through the monument on their way to and from upstream spawning

Spawn is the Egg cell, eggs and Spermatozoa, sperm released or deposited into water by aquatic animals. As a verb, ''to spawn'' refers to the process of freely releasing eggs and sperm into a body of water (fresh or marine); the physical act is ...

beds and the Pacific Ocean. Species observed at the Sheep Rock Unit also include those able to tolerate warm summer river temperatures: bridgelip suckers, northern pikeminnow, redside shiners, and smallmouth bass

The smallmouth bass (''Micropterus dolomieu'') is a species of freshwater fish in the Centrarchidae, sunfish family (biology), family (Centrarchidae) of the order (biology), order Centrarchiformes. It is the type species of its genus ''Micropterus ...

. From October through June, when the water is cooler, Columbia River redband trout

The Columbia River redband trout, the inland redband trout or the interior redband troutsculpin

A sculpin is a type of fish that belongs to the superfamily Cottoidea in the order Perciformes.Kane, E. A. and T. E. Higham. (2012)Life in the flow lane: differences in pectoral fin morphology suggest transitions in station-holding demand acros ...

are among species that move downriver through the park. The Park Service has removed or replaced irrigation diversions along the river or Rock Creek that formerly impeded fish movement, and it is restoring riparian vegetation such as black cottonwood trees that shade the water in summer and provide habitat for aquatic insects.

Activities

Entrance to the park and its visitor center, museums, and exhibits is free, and trails, overlooks, and picnic sites at all three units are open during daylight hours year-round. No food, lodging, or fuel is available in the park, and camping is not allowed. Hours of operation for the Cant Ranch and its cultural museum vary seasonally. The Thomas Condon Paleontology Center is open every day from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m except for federal holidays during the winter season from

Entrance to the park and its visitor center, museums, and exhibits is free, and trails, overlooks, and picnic sites at all three units are open during daylight hours year-round. No food, lodging, or fuel is available in the park, and camping is not allowed. Hours of operation for the Cant Ranch and its cultural museum vary seasonally. The Thomas Condon Paleontology Center is open every day from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m except for federal holidays during the winter season from Veterans Day

Veterans Day (originally known as Armistice Day) is a federal holiday in the United States observed annually on November 11, for honoring military veterans of the United States Armed Forces. It coincides with holidays in several countries, i ...

in November through Presidents' Day

Presidents' Day, officially Washington's Birthday at the federal governmental level, is a holiday in the United States celebrated on the third Monday of February. It is often celebrated to honor all those who served as presidents of the United S ...

in February. Its amenities include a fossil museum, theater, education classroom, bookstore, restrooms, and drinking fountains. There is no cell phone or pay telephone service in the monument. Water taps at picnic areas are shut down in the colder months.

The Sheep Rock Unit has eight trails ranging in length from at the Mascall Formation Overlook to at Blue Basin. Four trails of a quarter-mile to long cross parts of the Painted Hills Unit. At the Clarno Unit, three separate quarter-mile trails begin at a parking lot along Oregon Route 218, below the face of the Clarno Palisades. Many of the trails have interpretive signs about the history, geology, and fossils of the region, and three trails—Story in Stone at the Sheep Rock Unit, and Painted Cove and Leaf Hill at the Painted Hills Unit—are accessible by wheelchair. Visitors are asked to stay on the trails and off bare rock and hardpan

In soil science, agriculture and gardening, hardpan or soil pan is a dense layer of soil, usually found below the uppermost topsoil layer. There are different types of hardpan, all sharing the general characteristic of being a distinct soil layer ...

to avoid damage to fossils and fragile soils.

Ranger-led events at the monument have historically included indoor and outdoor talks, showings of an 18-minute orientation film, hikes in Blue Basin, Cant Ranch walking tours, and astronomy programs at the Painted Hills Unit. These events are free and most do not require reservations. Specific times for the activities are available from rangers at the monument. For students and teachers, the Park Service offers programs at the monument as well as fossil kits and other materials for classroom use.

Pets are allowed in developed areas and along hiking trails but must be leashed or otherwise restrained. Horses are not allowed on hiking trails, in picnic areas, or on bare rock exposures in undeveloped areas of the monument. Digging, disturbing, or collecting any of the park's natural resources, including fossils, is prohibited. Fossil theft is an ongoing problem. No mountain biking is allowed on monument land, although the Malheur National Forest

The Malheur National Forest is a United States National Forest, National Forest in the U.S. state of Oregon. It contains more than in the Blue Mountains (Pacific Northwest), Blue Mountains of eastern Oregon. The forest consists of Great Basi ...

east of Dayville has biking trails. Fishing is legal from monument lands along the John Day River for anyone with an Oregon fishing license. Rafting on the John Day River is seasonally popular, although the favored runs begin at or downstream of Service Creek and do not pass through the monument. Risks to monument visitors include extremely hot summer temperatures and icy winter roads, two species of venomous rattlesnakes, two species of venomous spiders, tick

Ticks are parasitic arachnids of the order Ixodida. They are part of the mite superorder Parasitiformes. Adult ticks are approximately 3 to 5 mm in length depending on age, sex, and species, but can become larger when engorged. Ticks a ...

s, scorpions, puncturevine, and poison ivy

Poison ivy is a type of allergenic plant in the genus '' Toxicodendron'' native to Asia and North America. Formerly considered a single species, '' Toxicodendron radicans'', poison ivies are now generally treated as a complex of three separate s ...

.

See also

*List of fossil sites

This list of fossil sites is a worldwide list of localities known well for the presence of fossils. Some entries in this list are notable for a single, unique find, while others are notable for the large number of fossils found there. Many of ...

* List of national monuments of the United States

The United States has 138 protected areas known as national monuments. The president of the United States can establish a national monument by presidential proclamation, and the United States Congress can do so by legislation. The president's a ...

Notes and references

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* *External links

Official website

at th

John Day Fossil Beds

at ''The Oregon Encyclopedia''

State of the Park Report

– National Park Service, December 2013

– National Park Service, interactive

— real-time views of the Paleontology Lab and Sheep Rock

National Park Service: Wild Flowers at John Day Fossil Beds

— illustrated (PDF). {{authority control National Park Service national monuments in Oregon Fossil parks in the United States Fossil trackways in the United States Parks in Grant County, Oregon Protected areas of Wheeler County, Oregon Museums in Grant County, Oregon Natural history museums in Oregon Volcanoes of Oregon Landforms of Grant County, Oregon Landforms of Wheeler County, Oregon Eocene paleontological sites of North America Paleogene geology of Oregon Paleontology in Oregon Cenozoic paleontological sites of North America Protected areas established in 1975 1975 establishments in Oregon 1864 in paleontology 1975 in paleontology National Natural Landmarks in Oregon