Christopher Hills on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Christopher Brian Hills (April 9, 1926 – January 31, 1997) was an English-born author, described as the "Father of Spirulina" for popularizing spirulina

Believing that Jamaica's strength lay in its agriculture, Hills co-founded the Jamaica Agriculture & Industrial Party (AIP) as an alternative to the two major political parties:

Believing that Jamaica's strength lay in its agriculture, Hills co-founded the Jamaica Agriculture & Industrial Party (AIP) as an alternative to the two major political parties:

In 1959 Hills had lobbied Nehru to approve a government in exile for the

In 1959 Hills had lobbied Nehru to approve a government in exile for the

cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria ( ) are a group of autotrophic gram-negative bacteria that can obtain biological energy via oxygenic photosynthesis. The name "cyanobacteria" () refers to their bluish green (cyan) color, which forms the basis of cyanobacteri ...

as a food supplement

A dietary supplement is a manufactured product intended to supplement a person's diet by taking a pill, capsule, tablet, powder, or liquid. A supplement can provide nutrients either extracted from food sources, or that are synthetic ( ...

. He also wrote 30 books on consciousness, meditation

Meditation is a practice in which an individual uses a technique to train attention and awareness and detach from reflexive, "discursive thinking", achieving a mentally clear and emotionally calm and stable state, while not judging the meditat ...

, yoga

Yoga (UK: , US: ; 'yoga' ; ) is a group of physical, mental, and spiritual practices or disciplines that originated with its own philosophy in ancient India, aimed at controlling body and mind to attain various salvation goals, as pra ...

and spiritual evolution, divining

Divination () is the attempt to gain insight into a question or situation by way of an occultic ritual or practice. Using various methods throughout history, diviners ascertain their interpretations of how a should proceed by reading signs, ...

, world government

World government is the concept of a single political authority governing all of Earth and humanity. It is conceived in a variety of forms, from tyrannical to democratic, which reflects its wide array of proponents and detractors.

There has ...

, aquaculture

Aquaculture (less commonly spelled aquiculture), also known as aquafarming, is the controlled cultivation ("farming") of aquatic organisms such as fish, crustaceans, mollusks, algae and other organisms of value such as aquatic plants (e.g. Nelu ...

, and personal health.

Hills was described by the press as a "Natural Food

Natural food and all-natural food are terms in food labeling and marketing with several definitions, generally denoting foods that are not manufactured by processing. In some countries like the United Kingdom, the term "natural" is defined and ...

s Pioneer". There is no robust evidence that spirulina supplements have any significant beneficial health effects, and Hill's companies were sued for making misleading claims about their effectiveness.

Early biography

Born in Grimsby, England to a family of fishermen, Hills grew up sailing theNorth Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. A sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Se ...

. In 1940 he enrolled as a cadet in nautical school and joined the British Merchant Navy

The British Merchant Navy is the collective name given to British civilian ships and their associated crews, including officers and ratings. In the UK, it is simply referred to as the Merchant Navy or MN. Merchant Navy vessels fly the Red Ensi ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. At sea, Hills had several life and death experiences that formed his views on karma

Karma (, from , ; ) is an ancient Indian concept that refers to an action, work, or deed, and its effect or consequences. In Indian religions, the term more specifically refers to a principle of cause and effect, often descriptively called ...

, divinity and destiny. At the end of the war, as navigating officer for an Esso

Esso () is a trading name for ExxonMobil. Originally, the name was primarily used by its predecessor Standard Oil of New Jersey after the breakup of the original Standard Oil company in 1911. The company adopted the name "Esso" (from the phon ...

oil tanker docked in Curaçao

Curaçao, officially the Country of Curaçao, is a constituent island country within the Kingdom of the Netherlands, located in the southern Caribbean Sea (specifically the Dutch Caribbean region), about north of Venezuela.

Curaçao includ ...

, he set up shop as a commodities trader

A commodity market is a market that trades in the primary economic sector rather than manufactured products. The primary sector includes agricultural products, energy products, and metals. Soft commodities may be perishable and harvested, wh ...

with branch offices in Venezuela

Venezuela, officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many Federal Dependencies of Venezuela, islands and islets in the Caribbean Sea. It com ...

and Aruba

Aruba, officially the Country of Aruba, is a constituent island country within the Kingdom of the Netherlands, in the southern Caribbean Sea north of the Venezuelan peninsula of Paraguaná Peninsula, Paraguaná and northwest of Curaçao. In 19 ...

. When a client reneged on a deal, Hills moved to Jamaica

Jamaica is an island country in the Caribbean Sea and the West Indies. At , it is the third-largest island—after Cuba and Hispaniola—of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean. Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, west of Hispaniola (the is ...

. There with the help of the philanthropist Percy Junor he founded commodity companies specializing in sugar, bananas, insurance, telegraph communications and agricultural spices pimento, nutmeg

Nutmeg is the seed, or the ground spice derived from the seed, of several tree species of the genus '' Myristica''; fragrant nutmeg or true nutmeg ('' M. fragrans'') is a dark-leaved evergreen tree cultivated for two spices derived from its fru ...

s and ginger

Ginger (''Zingiber officinale'') is a flowering plant whose rhizome, ginger root or ginger, is widely used as a spice and a folk medicine. It is an herbaceous perennial that grows annual pseudostems (false stems made of the rolled bases of l ...

. Financing for the first export corporation came from British businessman Andrew Hay, then husband of best-selling motivational author Louise Hay

Louise Lynn Hay (October 8, 1926 – August 30, 2017) was an American motivational author, professional speaker and AIDS advocate. She authored several New Thought self-help books, including the 1984 book '' You Can Heal Your Life'', and founde ...

who in the 1950s was a high-fashion model and family friend.

On July 29, 1950, Christopher Hills married Norah Katherine Bremner (May 6, 1916 - December 14, 1995) in Saint Andrew, Surrey, Jamaica. Norah was an English woman who was deputy headmistress of Wolmer's School in Kingston

Kingston may refer to:

Places

* List of places called Kingston, including the six most populated:

** Kingston, Jamaica

** Kingston upon Hull, England

** City of Kingston, Victoria, Australia

** Kingston, Ontario, Canada

** Kingston upon Thames, ...

. Her father, Bernard Eustace Bremner (1889-1976), was the Magistrate, Chief of Customs, and Mayor of King's Lynn

King's Lynn, known until 1537 as Bishop's Lynn and colloquially as Lynn, is a port and market town in the borough of King's Lynn and West Norfolk in the county of Norfolk, England. It is north-east of Peterborough, north-north-east of Cambridg ...

, Norfolk

Norfolk ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in England, located in East Anglia and officially part of the East of England region. It borders Lincolnshire and The Wash to the north-west, the North Sea to the north and eas ...

who in 1951 co-founded the King's Lynn Festival with concert pianist Ruth Roche, Baroness Fermoy. Lady Fermoy, wife of Baron Fermoy

Baron Fermoy is a title in the Peerage of Ireland. The title was created by Queen Victoria by letters patent of 10 September 1856 for Edmond Roche.

Previous letters patent had been issued on 14 May 1855 which purported to create this barony fo ...

, is Diana, Princess of Wales

Diana, Princess of Wales (born Diana Frances Spencer; 1 July 1961 – 31 August 1997), was a member of the British royal family. She was the first wife of Charles III (then Prince of Wales) and mother of Princes William, ...

' maternal grandmother. The Hillses had two sons, both born in Jamaica. The family sailed to England for events such as the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II

The Coronation of the British monarch, coronation of Elizabeth II as queen of the United Kingdom and the other Commonwealth realms took place on 2 June 1953 at Westminster Abbey in London. Elizabeth acceded to the throne at the age of 25 upon th ...

and Mayor Bremner's presenting Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother

Elizabeth Angela Marguerite Bowes-Lyon (4 August 1900 – 30 March 2002) was Queen of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 to 6 February 1952 as the wife of King George VI. She was al ...

with Freedom of the Borough, which encompassed the royal family's home at nearby Sandringham Sandringham can refer to:

Places

Australia

* Sandringham, New South Wales, a suburb of Sydney

* Sandringham, Queensland, a rural locality

* Sandringham, Victoria, a suburb of Melbourne

**Sandringham railway line

**Sandringham railway station

* ...

.

Jamaica business leader

From 1949 to 1967, Christopher and Norah Hills became influential in Jamaica's commerce, art, politics and culture. Believing that Jamaica's strength lay in its agriculture, Hills co-founded the Jamaica Agriculture & Industrial Party (AIP) as an alternative to the two major political parties:

Believing that Jamaica's strength lay in its agriculture, Hills co-founded the Jamaica Agriculture & Industrial Party (AIP) as an alternative to the two major political parties: Jamaica Labour Party

The Jamaica Labour Party (JLP; ) is one of the two major political parties in Jamaica, the other being the People's National Party (PNP). While its name might suggest that it is a social democratic party (as is the case for "Labour" parties in se ...

(JLP) and People's National Party

The People's National Party (PNP) (PNP; ) is a Social democracy, social democratic List of political parties in Jamaica, political party in Jamaica, founded in 1938 by Norman Manley, Norman Washington Manley who served as party president unti ...

(PNP), both of which he felt were too busy warring with each other to look out for the middle class and the country people who were the backbone of Jamaica's rural economy. Despite competing vigorously in the polls, the Hills couple were nevertheless close friends with JLP leader Sir Alexander Bustamante

Sir William Alexander Clarke Bustamante (born William Alexander Clarke; 24 February 1884 – 6 August 1977) was a Jamaican politician and Jamaica Labour Party leader, who, on Independence Day, August 6th, 1962, became the first prime minister ...

and Norman Manley

Norman Washington Manley (4 July 1893 – 2 September 1969) was a Jamaican statesman who served as the first and only Premier of Jamaica. A Rhodes Scholar, Manley became one of Jamaica's leading lawyers in the 1920s. Manley was an advocate o ...

, head of the PNP, who both served as Jamaican Prime Ministers. Norman Manley had been best man at the Hills' wedding.

In 1951 Christopher and Norah Hills founded Hills Galleries Ltd, which, in cooperation with the Prime Minister's wife Edna Manley

Edna Swithenbank Manley, Jamaican Order of Merit, OM (28 February 1900 – 9 February 1987) is considered one of the most important artists and arts educators in Jamaica. She was known primarily as a sculptor, although her oeuvre included ...

, became a nexus of the Jamaican art movement. The Gallery & Antiques showroom at 101 Harbour Street, Kingston was built on the site of Simon Bolivar

Simon may refer to:

People

* Simon (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the given name Simon

* Simon (surname), including a list of people with the surname Simon

* Eugène Simon, French naturalist and the genus ...

's Jamaica residence where, in 1815, the revolutionary wrote his famous letter Carta de Jamaica

The Jamaica Letter or (or Letter from Jamaica or , also "Answer from a southern American to a gentleman of this island") was a document written by Simón Bolívar in Jamaica in 1815. It was a response to a letter from Jamaican merchant Henry Cul ...

.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s Hills Galleries supplied and exhibited local celebrity artists Ian Fleming

Ian Lancaster Fleming (28 May 1908 – 12 August 1964) was a British writer, best known for his postwar ''James Bond'' series of spy novels. Fleming came from a wealthy family connected to the merchant bank Robert Fleming & Co., and his ...

and Noël Coward

Sir Noël Peirce Coward (16 December 189926 March 1973) was an English playwright, composer, director, actor, and singer, known for his wit, flamboyance, and what ''Time (magazine), Time'' called "a sense of personal style, a combination of c ...

, enjoyed the patronage of British royals and such high-profile clients as Sadruddin Aga Khan

Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan ( 1933 – 2003) was a French-born statesman and activist who served as United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees from 1966 to 1977, during which he reoriented the agency's focus beyond Europe and prepared it for a ...

, Winthrop Rockefeller

Winthrop Rockefeller (May 1, 1912 – February 22, 1973) was an American politician and philanthropist. Rockefeller was the fourth son and fifth child of American financier John D. Rockefeller Jr. and Abby Aldrich Rockefeller. He was one of th ...

, Elizabeth Taylor

Dame Elizabeth Rosemond Taylor (February 27, 1932 – March 23, 2011) was an English and American actress. She began her career as a child actress in the early 1940s and was one of the most popular stars of classical Hollywood cinema in the 19 ...

, Lady Bird Johnson

Claudia Alta "Lady Bird" Johnson (; December 22, 1912 – July 11, 2007) was First Lady of the United States from 1963 to 1969 as the wife of President Lyndon B. Johnson. She had previously been Second Lady of the United States from 1961 to 196 ...

, Grace Kelly

Grace Patricia Kelly (November 12, 1929 – September 14, 1982), also known as Grace of Monaco, was an American actress and Princess of Monaco as the wife of Prince Rainier III from their marriage on April 18, 1956, until her death in 1982. ...

and Errol Flynn

Errol Leslie Thomson Flynn (20 June 1909 – 14 October 1959) was an Australian and American actor who achieved worldwide fame during the Golden Age of Hollywood. He was known for his romantic swashbuckler roles, frequent partnerships with Oliv ...

. Hills Galleries was also the main agent for Rowney's, Grumbacher and Winsor & Newton

Winsor & Newton (also abbreviated W&N) is an England, English manufacturing company based in London that produces a wide variety of fine art products, including acrylic paint, acrylics, oil paint, oils, watercolour painting, watercolour, gouache ...

art supplies in the West Indies. Through multiple exhibitions, the Hillses nurtured or launched the careers of a plethora of Jamaican artists, such as Gaston Tabois, Kenneth Abendana Spencer, Carl Abrahams, Barrington Watson

Basil Barrington Watson Order of Distinction, CD (9 January 1931 – 26 January 2016) was a Jamaican painter.

Biography

Born in 1931 January 9th in Lucea, Jamaica, Lucea, Barrington Watson made his original mark in Jamaica as a football player ...

, Albert Huie

Albert Huie (31 December 1920 – 31 January 2010) was a Jamaican painter.

Early life and education

Born in Falmouth, Trelawny Parish, Jamaica, Huie moved to Kingston when he was 16 years old;

, Gloria Escoffery

Gloria Escoffery OD (22 December 1923 – 24 April 2002) was a Jamaican painter, poet and art critic that contributed to post-colonial arts and culture during the mid-to-late 20th century.

Biography

Born in Gayle, Saint Mary Parish, Jamaica, ...

, and the revivalist preacher/painter/sculptor Mallica Reynolds.

Christopher Hills opened a Hills Galleries branch on Jamaica's north coast at Montego Bay

Montego Bay () is the capital of the Parishes of Jamaica, parish of Saint James Parish, Jamaica, St. James in Jamaica. The city is the fourth most populous urban area in the country, after Kingston, Jamaica, Kingston, Spanish Town, and Portmore ...

, mooring his yacht, the ''Robanne'' at Round Hill, a popular resort for foreign leaders and industrialists vacationing in the Caribbean. It was there he met then Vice President Lyndon Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), also known as LBJ, was the 36th president of the United States, serving from 1963 to 1969. He became president after assassination of John F. Kennedy, the assassination of John F. Ken ...

and CBS president William S. Paley

William Samuel Paley (September 28, 1901 – October 26, 1990) was an American businessman, primarily involved in the media, and best known as the chief executive who built the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) from a small radio network into o ...

, who in 1956, sponsored a Hills Galleries exhibition of Jamaican art at Barbizon Plaza in New York City, which awoke U.S. art collectors to Jamaica's dynamic sphere of artistic talent. The exhibition was described by the Daily Gleaner as "Epochal in the establishment of a market for West Indian art." The Hills family spent weekends and holidays at Port Antonio

Port Antonio () is the capital of the parish of Portland on the northeastern coast of Jamaica, about from Kingston. It had a population of 12,285 in 1982 and 13,246 in 1991. It is the island's third largest port, famous as a shipping point for ...

visiting friends and clients including their neighbor, novelist Robin Moore

Robert Lowell Moore Jr. (October 31, 1925 – February 21, 2008) was an American writer who wrote '' The Green Berets'', '' The French Connection: A True Account of Cops, Narcotics, and International Conspiracy'', and with Xaviera Hollander and ...

at Blue Lagoon. There Hills met Baron Hans Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza

Hans Heinrich August Gábor Tasso Thyssen-Bornemisza de Kászon, Baron Thyssen-Bornemisza (13 April 1921 – 27 April 2002), was a Dutch-born Swiss industrialist and art collector. A member of the Thyssen family, he had a Hungarian title and ...

who asked Hills to curate part of his art collection. For five years many classic works of the baron's international art acquisitions decorated the walls of the Hills' home. Von Thyssen also granted Hills' children access to his private island at San San near Port Antonio.

Rastafari movement

Hills also became an advocate for Jamaica'sRastafari movement

Rastafari is an Abrahamic religion that developed in Jamaica during the 1930s. It is classified as both a new religious movement and a social movement by scholars of religion. There is no central authority in control of the movement and much ...

, who were being oppressed in the late fifties. He gave Rastafarians jobs as woodcarver

Wood carving (or woodcarving) is a form of woodworking by means of a cutting tool (knife) in one hand or a chisel by two hands or with one hand on a chisel and one hand on a mallet, resulting in a wooden figure or figurine, or in the sculpture, ...

s, free paints to poor artists, such as the now-famed Ras Dizzy and bailed them out of Spanish Town Prison while encouraging rasta brethren to sustain themselves through art and music. Christopher and Norah Hills were personally thanked for their years of support for struggling rastas by Mortimo Planno, the Rasta teacher of Bob Marley

Robert Nesta Marley (6 February 1945 – 11 May 1981) was a Jamaican singer, songwriter, and guitarist. Considered one of the pioneers of reggae, he fused elements of reggae, ska and rocksteady and was renowned for his distinctive voca ...

and one of the few Rastafarian elders to have met with Emperor Haile Selassie

Haile Selassie I (born Tafari Makonnen or ''Ethiopian aristocratic and court titles#Lij, Lij'' Tafari; 23 July 189227 August 1975) was Emperor of Ethiopia from 1930 to 1974. He rose to power as the Ethiopian aristocratic and court titles, Rege ...

in Addis Ababa

Addis Ababa (; ,) is the capital city of Ethiopia, as well as the regional state of Oromia. With an estimated population of 2,739,551 inhabitants as of the 2007 census, it is the largest city in the country and the List of cities in Africa b ...

, Ethiopia

Ethiopia, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country located in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the north, Djibouti to the northeast, Somalia to the east, Ken ...

.

Hills also reasoned Gandhian

The followers of Mahatma Gandhi,one of the prominent figure of the Indian independence movement, are called Gandhians.

Gandhi's legacy includes a wide range of ideas ranging from his dream of ideal India (or ''Rama Rajya)'', economics, environ ...

nonviolence

Nonviolence is the personal practice of not causing harm to others under any condition. It may come from the belief that hurting people, animals and/or the environment is unnecessary to achieve an outcome and it may refer to a general philosoph ...

with Leonard Howell

Leonard Percival Howell (16 June 1898 – 23 January 1981), also known as The Gong or G. G. Maragh (for ''Gangun Guru''), was a Jamaican religious figure. According to his biographer Hélène Lee, Howell was born into an Anglican family. He was o ...

, activist who founded Pinnacle, a Rastafarian community farm at Sligoville, a few miles from Hills' home. In 1958 Pinnacle was raided in a brutal crackdown by the authorities, ostensibly for growing marijuana

Cannabis (), commonly known as marijuana (), weed, pot, and ganja, List of slang names for cannabis, among other names, is a non-chemically uniform psychoactive drug from the ''Cannabis'' plant. Native to Central or South Asia, cannabis has ...

, but in fact Rastafari

Rastafari is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic religion that developed in Jamaica during the 1930s. It is classified as both a new religious movement and a social movement by Religious studies, scholars of religion. There is no central authori ...

at that time was regarded by The Crown as a threat to social harmony. Hills interceded with the Prime Minister but, with an election coming, law and order politics prevailed and many sustainable farming families had to leave the land. For his support, Hills was given the moniker "The First White Rasta". Unlike his skeptical friends and business colleagues, he saw Rastafarian spirituality as a righteous way of life, indeed growing out his hair and beard in solidarity and also in keeping with his emerging interest in the sadhu

''Sadhu'' (, IAST: ' (male), ''sādhvī'' or ''sādhvīne'' (female), also spelled ''saddhu'') is a religious ascetic, mendicant or any holy person in Hinduism and Jainism who has renounced the worldly life. They are sometimes alternatively ...

s and enlightened sages of India who had much in common with the vegetarian mystical Rastafarians.

Spiritual awakening

By 1960 Christopher Hills had accumulated a largemetaphysical

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that examines the basic structure of reality. It is traditionally seen as the study of mind-independent features of the world, but some theorists view it as an inquiry into the conceptual framework of h ...

library on frequent trips to Samuel Weiser Books in New York, while writing his own books, ''Kingdom of Desire'', ''Power of the Doctrine'' and ''The Power of Increased Perception''. At 30 he retired from business and began to research multiple spiritual paths and the physics of what Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein (14 March 187918 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist who is best known for developing the theory of relativity. Einstein also made important contributions to quantum mechanics. His mass–energy equivalence f ...

called Unified field theory

In physics, a Unified Field Theory (UFT) or “Theory of Everything” is a type of field theory that allows all fundamental forces of nature, including gravity, and all elementary particles to be written in terms of a single physical field. Ac ...

. Prolific research papers and lectures came out of Hills' laboratory in the Blue Mountains (Jamaica)

The Blue Mountains are the longest mountain range in Jamaica. They include the island's highest point, Blue Mountain Peak, at 2256 m (7402 ft). From the summit, accessible via a walking track, both the north and south coasts of the i ...

on subjects such as bioenergetics

Bioenergetics is a field in biochemistry and cell biology that concerns energy flow through living systems. This is an active area of biological research that includes the study of the transformation of energy in living organisms and the study o ...

, hypnosis

Hypnosis is a human condition involving focused attention (the selective attention/selective inattention hypothesis, SASI), reduced peripheral awareness, and an enhanced capacity to respond to suggestion.In 2015, the American Psychological ...

, tele-thought, biophysics

Biophysics is an interdisciplinary science that applies approaches and methods traditionally used in physics to study biological phenomena. Biophysics covers all scales of biological organization, from molecular to organismic and populations ...

, effects of solar radiation on living organisms, resonant systems of ionosphere

The ionosphere () is the ionized part of the upper atmosphere of Earth, from about to above sea level, a region that includes the thermosphere and parts of the mesosphere and exosphere. The ionosphere is ionized by solar radiation. It plays ...

, and capacitor effects of human body on static electricity and electron discharge of the nervous system. In 1960 he began a 30-year project to document the effects of sound and color on human consciousness and states of health.

Global outreach

With Norah Hills running the galleries, Hills set forth on a two-year journey travelling in Asia, Europe, Pakistan and India, meeting with members of the UN and calling on politicians, scientists and religious leaders.UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

hired him to shoot 1,000 photographs of their projects in faraway countries, which appeared in an exhibit at United Nations headquarters

The headquarters of the United Nations (UN) is on of grounds in the Turtle Bay, Manhattan, Turtle Bay neighborhood of Midtown Manhattan in New York City. It borders First Avenue (Manhattan), First Avenue to the west, 42nd Street (Manhattan), 42nd ...

.

Hills' global odyssey's itinerary grew out of publishing his views on conflict resolution

Conflict resolution is conceptualized as the methods and processes involved in facilitating the peaceful ending of Conflict (process), conflict and Revenge, retribution. Committed group members attempt to resolve group conflicts by actively co ...

and alternative government in a manifesto, ''Framework for Unity'', that was circulated to The Commission for Research in the Creative Faculties of Man, a network he had founded of thinkers around the world which, in 1961, included Humphry Osmond

Humphry Fortescue Osmond (1 July 1917 – 6 February 2004) was an English psychiatrist who moved to Canada and later the United States. He is known for inventing the word '' psychedelic'' and for his research into interesting and useful applicat ...

, Andrija Puharich

Andrija Puharich (February 19, 1918 – January 3, 1995) — born Henry Karel Puharić — was a medical and parapsychological researcher, medical inventor, physician and author, known as the person who brought Israeli Uri Geller (born 1946) an ...

, David Ben-Gurion

David Ben-Gurion ( ; ; born David Grün; 16 October 1886 – 1 December 1973) was the primary List of national founders, national founder and first Prime Minister of Israel, prime minister of the State of Israel. As head of the Jewish Agency ...

, and Lady Isobel Cripps

Dame Isobel Cripps, Order of the British Empire, GBE (''née'' Swithinbank; 25 January 1891 – 11 April 1979), also known as Isobel, the Honourable Lady Cripps, was a British overseas aid organiser and the wife of the Honourable Stafford Cripps ...

, among its 500 members.

After teaming up with his good friend and noted lawyer Luis Kutner

Luis Kutner (June 9, 1908 – March 1, 1993) was a US human rights activist, FBI informant, and lawyer who was on the National Advisory Council of the US branch of Amnesty International during its early years and created the concept of a livin ...

(co-founder of Amnesty International

Amnesty International (also referred to as Amnesty or AI) is an international non-governmental organization focused on human rights, with its headquarters in the United Kingdom. The organization says that it has more than ten million members a ...

), Hills decided to search the world for a spot to establish a Center where a dedicated community could live and test his ''World Constitution for Self-Government by Nature's Laws'', which he published in a book with an introduction by Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, and public intellectual. He had influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, and various areas of analytic ...

.

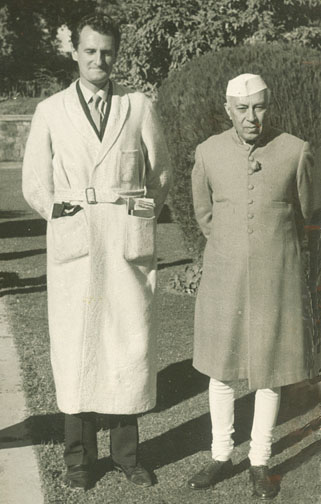

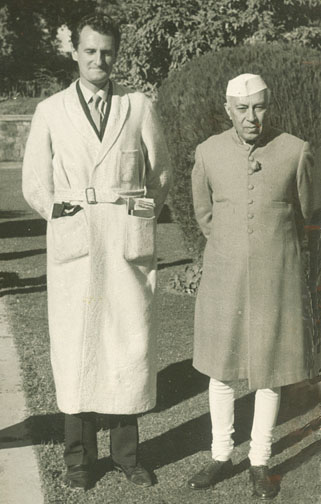

Friendship with Jawaharlal Nehru

Working his way on a speaking tour through Europe in the direction of India, Hills decided to make a precarious expedition to the remote HimalayanHunza Valley

The Hunza Valley (; ) is a mountainous valley located in the northern region of the Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan.

Geography

The valley stretches along the Hunza River and shares borders with Ishkoman Valley, Ishkoman to the northwest, Shigar Val ...

where he had long been curious about the diet and extraordinary longevity of the Pashtun

Pashtuns (, , ; ;), also known as Pakhtuns, or Pathans, are an Iranic ethnic group primarily residing in southern and eastern Afghanistan and northwestern Pakistan. They were historically also referred to as Afghans until 1964 after the ...

, Balti and Uzbek hill tribes. In Pakistan, Hills was the guest of Professors Duranni and Walid Uddin at Peshawar's College of Engineering. Visiting Sufi holy men and Islamic scholars in Karachi

Karachi is the capital city of the Administrative units of Pakistan, province of Sindh, Pakistan. It is the List of cities in Pakistan by population, largest city in Pakistan and 12th List of largest cities, largest in the world, with a popul ...

, he met Zulfikar Ali Bhutto

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (5 January 1928 – 4 April 1979) was a Pakistani barrister and politician who served as the fourth president of Pakistan from 1971 to 1973 and later as the ninth Prime Minister of Pakistan, prime minister of Pakistan from 19 ...

to discuss possible Indo-Pakistan cooperation in algae

Algae ( , ; : alga ) is an informal term for any organisms of a large and diverse group of photosynthesis, photosynthetic organisms that are not plants, and includes species from multiple distinct clades. Such organisms range from unicellular ...

cultivation in the climatically suitable Gujrat-Sind border region, which is where Bhutto and his ancestors were from. Later, when Bhutto was overthrown in a military coup, Hills orchestrated urgent appeals to General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq

Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq (12 August 192417 August 1988) was a Pakistani military officer and statesman who served as the sixth president of Pakistan from 1978 until Death of Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, his death in an airplane crash in 1988. He also se ...

for clemency, but, like many westerners protesting Bhutto's imprisonment, was ignored, and Bhutto was hanged.

In the 1950s Hills became known to Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru (14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat, and statesman who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20th century. Nehru was a pr ...

through his friend the Deputy leader of India's Congress Party, Surendra Mohan Ghose, a Bengali revolutionary and relative of Sri Aurobindo

Sri Aurobindo (born Aurobindo Ghose; 15 August 1872 – 5 December 1950) was an Indian Modern yoga gurus, yogi, maharishi, and Indian nationalist. He also edited the newspaper Bande Mataram (publication), ''Bande Mataram''.

Aurobindo st ...

. Hills invited Ghose to Jamaica, to speak at the 1961 Commonwealth Parliamentary Conference, and together they formed a partnership to promote World Union and global famine relief through algae aquaculture. S.M. Ghose was one of the founders of Auroville

Auroville (; City of Dawn French: Cité de l'aube) is an experimental township in Viluppuram district, mostly in the state of Tamil Nadu, India, with some parts in the Union Territory of Puducherry in India.

, an experimental sustainable-living International Village in Tamil Nadu

Tamil Nadu (; , TN) is the southernmost States and union territories of India, state of India. The List of states and union territories of India by area, tenth largest Indian state by area and the List of states and union territories of Indi ...

. In 1962 Ghose took Hills to Sri Aurobindo Ashram

The Sri Aurobindo Ashram (French: ''Ashram de Sri Aurobindo'') is a spiritual community (ashram) located in Pondicherry (city), Pondicherry, in the Indian territory of Puducherry (union territory), Puducherry. It was founded by Sri Aurob ...

for a personal audience with Aurobindo's successor, spiritual head of the ashram, Mirra Alfassa

Mirra Alfassa (21 February 1878 – 17 November 1973), known to her followers as The Mother or ''La Mère'', was a French-Indian spiritual guru, occultist and yoga teacher, and a collaborator of Sri Aurobindo, who considered her to be of ...

, known as "The Mother". Later Ghose arranged for Christopher Hills' son, John Hills, to give the keynote address at the World Parliament of Youth in Puducherry in 1971.

In 1959 Hills had lobbied Nehru to approve a government in exile for the

In 1959 Hills had lobbied Nehru to approve a government in exile for the Dalai Lama

The Dalai Lama (, ; ) is the head of the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism. The term is part of the full title "Holiness Knowing Everything Vajradhara Dalai Lama" (圣 识一切 瓦齐尔达喇 达赖 喇嘛) given by Altan Khan, the first Shu ...

fleeing persecution in Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ), or Greater Tibet, is a region in the western part of East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are other ethnic groups s ...

and to grant full refugee status to exiled Tibetans. He had become connected to the Tibetans through his study of Buddhism

Buddhism, also known as Buddhadharma and Dharmavinaya, is an Indian religion and List of philosophies, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha, a wandering teacher who lived in the 6th or ...

and in 1960 provided funding for the Young Lama's Home School in Dalhousie, Himachal Pradesh founded by his English friend Freda Bedi

Freda Bedi (born Freda Marie Houlston; 5 February 1911 – 26 March 1977), also known as Sister Palmo or Gelongma Karma Kechog Palmo, was an English-Indian social worker, writer, Indian nationalist and Buddhist nun. She was jailed in British In ...

, one of Gandhi's handpicked satyagrahi

Satyāgraha (from ; ''satya'': "truth", ''āgraha'': "insistence" or "holding firmly to"), or "holding firmly to truth",' or "truth force", is a particular form of nonviolent resistance or civil resistance. Someone who practises satyagraha is ...

s who became Gelongma Karma Kechog Palmo, the first Western woman to take ordination in Tibetan Buddhism

Tibetan Buddhism is a form of Buddhism practiced in Tibet, Bhutan and Mongolia. It also has a sizable number of adherents in the areas surrounding the Himalayas, including the Indian regions of Ladakh, Gorkhaland Territorial Administration, D ...

. Freda Bedi is the mother of film and television star Kabir Bedi

Kabir Bedi (born 16 January 1946) is an Indian actor. His career has spanned three continents covering India, the United States and especially Italy among other Western countries in three media: film, television and theatre. He is noted for his ...

. In 1968 Hills contributed to Freda Bedi's building of the Karma Drubgyu Thargay Ling nunnery at Tilokpur in the Kangra Valley

Kangra Valley is a river valley situated in the Western Himalayas.16th Gyalwa Karmapa, Rangjung Rigpe Dorje in 1974.

When Hills arrived in India, he found Nehru besieged by border disputes with China and discussion inevitably turned to Hills' theories of

Three years after Jamaica's 1962 declaration of Independence from Britain, the Hills family moved to London, at the suggestion of two of his mentors, Bertrand Russell and Sir George Trevelyan, 4th Baronet. They helped Hills find and purchase a six-story Edwardian building in London's leafy

Three years after Jamaica's 1962 declaration of Independence from Britain, the Hills family moved to London, at the suggestion of two of his mentors, Bertrand Russell and Sir George Trevelyan, 4th Baronet. They helped Hills find and purchase a six-story Edwardian building in London's leafy

The conference generated some controversy when Indian politics intersected with religion, particularly the concept of ''Christ Yoga'', a book Hills had written linking Christ's teachings to those of

The conference generated some controversy when Indian politics intersected with religion, particularly the concept of ''Christ Yoga'', a book Hills had written linking Christ's teachings to those of

"Conduct Your Own Awareness Sessions"

with new-age author Robert B. Stone to whom the University later bestowed an honorary PhD. A small workshop produced pendulums for dowsing and a line of negative ion generators. From this base in California, Hills extended his hospitality to scientists, writers, philosophers and scholars such as

Christopher Hills' lifelong crusade against dictatorships and Man's inhumanity was manifested in the book ''Rise of the Phoenix'' while his passionate beliefs against deficit spending were set forth in a book on the global economy—''The Golden Egg''. A recurring theme throughout all Christopher Hills' approaches to world, local and family problems was a process he developed called "Creative Conflict"—the same principles of solving differences between individuals, political parties and even nations that Hills had debated with Adlai Stevenson, Nehru and Luis Kutner.

Throughout the seventies and eighties Hills focused on international affairs, particularly the emergence of democracy in the Soviet Republics, eventually traveling to Russia to meet with

Christopher Hills' lifelong crusade against dictatorships and Man's inhumanity was manifested in the book ''Rise of the Phoenix'' while his passionate beliefs against deficit spending were set forth in a book on the global economy—''The Golden Egg''. A recurring theme throughout all Christopher Hills' approaches to world, local and family problems was a process he developed called "Creative Conflict"—the same principles of solving differences between individuals, political parties and even nations that Hills had debated with Adlai Stevenson, Nehru and Luis Kutner.

Throughout the seventies and eighties Hills focused on international affairs, particularly the emergence of democracy in the Soviet Republics, eventually traveling to Russia to meet with

Penny Slinger

John Hills

Christopher Hills Foundation

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hills, Christopher 1926 births 1997 deaths British male writers 20th-century British businesspeople 20th-century British philanthropists Dowsing New Age writers Philanthropists from California University and college founders British Merchant Navy personnel of World War II Algaculture Arts in Jamaica Businesspeople from California English emigrants to the United States Rastafari People from Grimsby People from Boulder Creek, California Jamaican businesspeople Jamaican philanthropists

conflict resolution

Conflict resolution is conceptualized as the methods and processes involved in facilitating the peaceful ending of Conflict (process), conflict and Revenge, retribution. Committed group members attempt to resolve group conflicts by actively co ...

and how to avoid war. Their connection also evolved out of the fact that India was experiencing famine in some states. With dependence on wheat shipments from the United States, Hills helped lobby President Lyndon Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), also known as LBJ, was the 36th president of the United States, serving from 1963 to 1969. He became president after assassination of John F. Kennedy, the assassination of John F. Ken ...

for an increase in wheat aid, which was granted. But when Hills mentioned his research with algae as a food source, then Nehru became interested and offered to support cultivation in India.

While in New Delhi, Hills spent time with the prime minister at Teen Murti Bhavan

The Teen Murti Bhavan (''Teen Murti House''; formerly known as Flagstaff House) is a building and former residence in New Delhi. It was built by the British Raj and became the residence of the first Prime Minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru, ...

, enjoying Jawaharlal Nehru's rose gardens and meeting his daughter Indira Gandhi

Indira Priyadarshini Gandhi (Given name, ''née'' Nehru; 19 November 1917 – 31 October 1984) was an Indian politician and stateswoman who served as the Prime Minister of India, prime minister of India from 1966 to 1977 and again from 1980 un ...

. Hills was the guest of Indian industrialist G.D. Birla, where on his first day in India, he had met Swami Shantananda, a sage and a politically connected guru with whom Hills would travel throughout India for two years, much like a roaming sanyassin. On one of his "pilgrimages", Hills was taken by Shantanananda and Nehru's Parliamentary Secretary S.D. Upadhyaya to Brindavan for a private audience with India's highest female yogini

A yogini (Sanskrit: योगिनी, IAST: ) is a female master practitioner of tantra and yoga, as well as a formal term of respect for female Hindu or Buddhist spiritual teachers in the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia and Greater Tibe ...

Sri Anandamayi Ma, from whom he felt a "genuine sublime holiness" and received one of the most significant blessings in his life.

In Patna

Patna (; , ISO 15919, ISO: ''Paṭanā''), historically known as Pataliputra, Pāṭaliputra, is the List of state and union territory capitals in India, capital and largest city of the state of Bihar in India. According to the United Nations, ...

, Bihar

Bihar ( ) is a states and union territories of India, state in Eastern India. It is the list of states and union territories of India by population, second largest state by population, the List of states and union territories of India by are ...

, Hills, along with Raynor Johnson, were the only Europeans to attend the 1961 Science & Spirituality Conference, where seeds were sown for Hills' decade of cooperation with hundreds of Indian scientists and yogis, many of whom eventually journeyed to visit Hills' centres in the West and who comprised many of the delegates for a 1970 Yoga conference Hills staged in New Delhi.

In 1963, the Sri Aurobindo Ashram

The Sri Aurobindo Ashram (French: ''Ashram de Sri Aurobindo'') is a spiritual community (ashram) located in Pondicherry (city), Pondicherry, in the Indian territory of Puducherry (union territory), Puducherry. It was founded by Sri Aurob ...

and Gandhi Peace Foundation

The Gandhi Peace Foundation is an Indian organisation that studies and develops Mahatma Gandhi's thought.

History

The foundation was established on 31 July 1958 to preserve and spread Gandhi's thought. It began with donation of 10 million rup ...

sponsored another conference in Patna, hosted by Rajendra Prasad

Rajendra Prasad (3 December 1884 – 28 February 1963) was an Indian politician, lawyer, journalist and scholar who served as the first president of India from 1950 to 1962. He joined the Indian National Congress during the Indian independen ...

, Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2October 186930January 1948) was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethics, political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful Indian ...

's longtime right-hand disciple and first President of India

The president of India (ISO 15919, ISO: ) is the head of state of the Republic of India. The president is the nominal head of the executive, the first citizen of the country, and the commander-in-chief, supreme commander of the Indian Armed ...

. Prasad was supposed to speak at the conference but became ill, and Hills' guru Shantananda was leading prayers for him every day at the Sadaqat Ashram in Patna. Prasad requested to meet Hills, whose goals for World Union he had heard about from Nehru. Hills considered Prasad the most spiritual of the founders of Independent India, and their meeting was a profound encounter in which Prasad gave his blessing for Hills' global endeavors, but then the president lost consciousness, tightly holding onto Hills' hand.

Microalgae International

In earlier travels from Jamaica to Japan, Hills had formed anaquaculture

Aquaculture (less commonly spelled aquiculture), also known as aquafarming, is the controlled cultivation ("farming") of aquatic organisms such as fish, crustaceans, mollusks, algae and other organisms of value such as aquatic plants (e.g. Nelu ...

research company with his friend and colleague, biologist Dr Hiroshi Nakamura, Dean of Tokyo Women's University. Dr Nakamura was a noted scientist and a colleague of Emperor Hirohito

, Posthumous name, posthumously honored as , was the 124th emperor of Japan according to the traditional order of succession, from 25 December 1926 until Death and state funeral of Hirohito, his death in 1989. He remains Japan's longest-reigni ...

(himself a marine biologist) who asked Nakamura to research alternative food sources for Japan after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki had devastated food supplies. The goal of Hills and Nakmura's organization Microalgae International Union, was to develop strains of algae as a way of harnessing the sun's energy for biofuel

Biofuel is a fuel that is produced over a short time span from Biomass (energy), biomass, rather than by the very slow natural processes involved in the formation of fossil fuels such as oil. Biofuel can be produced from plants or from agricu ...

s and human nutrition and as a solution to World Hunger. Presented with M.I.U.'s feasibility studies

A feasibility study is an assessment of the practicality of a project or system. A feasibility study aims to objectively and rationally uncover the strengths and weaknesses of an existing business or proposed venture, opportunities and threats pr ...

, Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru endorsed Hills' proposal for bringing the cultivation of protein-rich Chlorella

''Chlorella'' is a genus of about thirteen species of single- celled or colonial green algae of the division Chlorophyta. The cells are spherical in shape, about 2 to 10 μm in diameter, and are without flagella. Their chloroplasts contain t ...

algae to the villages of India.

With India's Home Minister, Gulzari Lal Nanda

Gulzarilal Nanda (4 July 1898 – 15 January 1998) was an Indian politician and economist who specialised in labour issues. He was the Acting Prime Minister of India for two 13-day tenures following the deaths of Jawaharlal Nehru in 1964 and L ...

, Hills had co-founded the Institute of Psychic and Spiritual Research in New Delhi. A devout Gandhian, Nanda feared social upheaval and possible communal violence if poor and hungry villagers started migrating to India's cities so he threw his support behind Hills' plan for developing rural economies via small footprint aquaculture that could help villages become sustainable. A detailed plan for a pilot project in the Rann of Kutch

The Rann of Kutch is a large area of salt marshes that span the border between India and Pakistan. It is located mostly in the Kutch district of the Indian state of Gujarat, with a minor portion extending into the Sindh province of Pakistan. ...

was approved by the Indian government. However, the initiative became mired in bureaucracy when Nehru died in 1964. Nanda became acting prime minister but only until the new Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri

Lal Bahadur Shastri (; born Lal Bahadur Srivastava; 2 October 190411 January 1966) was an Indian politician and statesman who served as the Prime Minister of India, prime minister of India from 1964 to 1966. He previously served as Minister ...

was nominated to succeed Nehru. Shastri continued working with Hills and had his staff prepare a budget request for Parliament to fund the chlorella

''Chlorella'' is a genus of about thirteen species of single- celled or colonial green algae of the division Chlorophyta. The cells are spherical in shape, about 2 to 10 μm in diameter, and are without flagella. Their chloroplasts contain t ...

algae project. However, because it competed with traditional agricultural interests, the aquaculture project became victim to political jockeying as well as an outbreak of war with Pakistan. With Shastri's mysterious death at the 1966 India-Pakistan peace conference in Tashkent

Tashkent (), also known as Toshkent, is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Uzbekistan, largest city of Uzbekistan. It is the most populous city in Central Asia, with a population of more than 3 million people as of April 1, 2024. I ...

, the project lost its key sponsor.

Nevertheless, the networks Hills had established with the founders of modern India proved valuable when his son, John Hills, was introduced by Nanda and S.M. Ghose to Prime Minister Indira Gandhi

Indira Priyadarshini Gandhi (Given name, ''née'' Nehru; 19 November 1917 – 31 October 1984) was an Indian politician and stateswoman who served as the Prime Minister of India, prime minister of India from 1966 to 1977 and again from 1980 un ...

, who helped the younger Hills garner support among India's Congress party and religious leaders for India's largest conference of Western scientists and Indian yogis.

Centre House, London

Three years after Jamaica's 1962 declaration of Independence from Britain, the Hills family moved to London, at the suggestion of two of his mentors, Bertrand Russell and Sir George Trevelyan, 4th Baronet. They helped Hills find and purchase a six-story Edwardian building in London's leafy

Three years after Jamaica's 1962 declaration of Independence from Britain, the Hills family moved to London, at the suggestion of two of his mentors, Bertrand Russell and Sir George Trevelyan, 4th Baronet. They helped Hills find and purchase a six-story Edwardian building in London's leafy Kensington

Kensington is an area of London in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, around west of Central London.

The district's commercial heart is Kensington High Street, running on an east–west axis. The north-east is taken up by Kensingt ...

. There Christopher Hills and others, including Kevin Kingsland, founded Centre House, a self-discovery and human-potential community known as a nucleus of yoga and spirituality in the emerging New Age

New Age is a range of Spirituality, spiritual or Religion, religious practices and beliefs that rapidly grew in Western world, Western society during the early 1970s. Its highly eclecticism, eclectic and unsystematic structure makes a precise d ...

movement throughout the late sixties and seventies. Seekers came from all over the world to study with visiting gurus, such as Swami Satchidananda

Satchidananda Saraswati (; 22 December 1914 – 19 August 2002), born C. K. Ramaswamy Gounder and known as Swami Satchidananda, was an Indian yoga guru and religious teacher, who gained following in the West. He founded his own brand of Integra ...

, Muktananda

Muktananda (16 May 1908 – 2 October 1982), born Krishna Rai, was a yoga guru and the founder of Siddha Yoga. He was a disciple of Bhagavan Nityananda. He wrote books on the subjects of Kundalini Shakti, Vedanta, and Kashmir Shaivism, ...

, B.K.S. Iyengar

Bellur Krishnamachar Sundararaja Iyengar (14 December 1918 – 20 August 2014) was an Indian teacher of yoga and author. He is the founder of the style of yoga as exercise, known as "Iyengar Yoga", and was considered one of the foremost Modern ...

, Sangharakshita

Dennis Philip Edward Lingwood (26 August 192530 October 2018), known more commonly as Sangharakshita, was a British spiritual teacher and writer. In 1967, he founded the Friends of the Western Buddhist Order (FWBO), which was renamed the Trirat ...

and John G. Bennett as well as Sanskrit scholar Dr. Rammurti Mishra, Christmas Humphreys

Travers Christmas Humphreys, QC (15 February 1901 – 13 April 1983) was a British jurist who prosecuted several controversial cases in the 1940s and 1950s, and who later became a judge at the Old Bailey. He also wrote a number of works on Maha ...

, Tibetan lama

Lama () is a title bestowed to a realized practitioner of the Dharma in Tibetan Buddhism. Not all monks are lamas, while nuns and female practitioners can be recognized and entitled as lamas. The Tibetan word ''la-ma'' means "high mother", ...

s, chief Druids

A druid was a member of the high-ranking priestly class in ancient Celtic cultures. The druids were religious leaders as well as legal authorities, adjudicators, lorekeepers, medical professionals and political advisors. Druids left no wr ...

, homeopathic

Homeopathy or homoeopathy is a pseudoscientific system of alternative medicine. It was conceived in 1796 by the German physician Samuel Hahnemann. Its practitioners, called homeopaths or homeopathic physicians, believe that a substance tha ...

doctors and scientists studying meditation, telepathy and neuroplasticity

Neuroplasticity, also known as neural plasticity or just plasticity, is the ability of neural networks in the brain to change through neurogenesis, growth and reorganization. Neuroplasticity refers to the brain's ability to reorganize and rewir ...

in Hills' Yoga Science laboratory. It was here Christopher Hills wrote his magnum opus, ''Nuclear Evolution'' – recognized as a definitive treatise on the chakra

A chakra (; ; ) is one of the various focal points used in a variety of ancient meditation practices, collectively denominated as Tantra, part of the inner traditions of Hinduism and Buddhism.

The concept of the chakra arose in Hinduism. B ...

s as they relate to the human endocrine system

The endocrine system is a messenger system in an organism comprising feedback loops of hormones that are released by internal glands directly into the circulatory system and that target and regulate distant Organ (biology), organs. In vertebrat ...

, light frequencies and human personality. Yoga Journal

''Yoga Journal'' is a website and digital journal, formerly a print magazine, on yoga as exercise founded in California in 1975 with the goal of combining the essence of traditional yoga with scientific understanding. It has produced live events ...

described the book as, "Synthesizing a vast amount of information ranging from the structure of DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

to the metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that examines the basic structure of reality. It is traditionally seen as the study of mind-independent features of the world, but some theorists view it as an inquiry into the conceptual framework of ...

of consciousness" and also as, "A giant step forward in integrating science with religion in a meaningful way."

Centre House was an experiment in group consciousness where the majority of residents were well-educated students, teachers and scientists interested in the convergence of science and spirituality. For a while the large basement kitchen was a macrobiotic

A macrobiotic diet (or macrobiotics) is an unconventional restrictive diet based on ideas about types of food drawn from Zen Buddhism. The diet tries to balance the supposed yin and yang elements of food and cookware. Major principles of macrobio ...

restaurant, first run by Craig Sams

Craig Sams (born 17 July 1944) is a UK-based businessman and author. He was a co-founder of Green & Black's chocolate company.

Early life and education

Craig Sams was born in Nebraska, US. He graduated from Wharton Business School in 1966.

Care ...

which counted Yoko Ono

Yoko Ono (, usually spelled in katakana as ; born February 18, 1933) is a Japanese multimedia artist, singer, songwriter, and peace activist. Her work also encompasses performance art and filmmaking.

Ono grew up in Tokyo and moved to New York ...

among its health-conscious patrons. One of the early members of Centre House, Muz Murray (Ramana Baba) founded "Gandalf's Garden" magazine there, a publication chronicling the spiritual vitality of London's New Age scene, and which later also became a separate mystical community at World's End, London. Kevin Kingsland went on to found the Centre for Human Communication in Devon and Grael Associates (a Community Company).

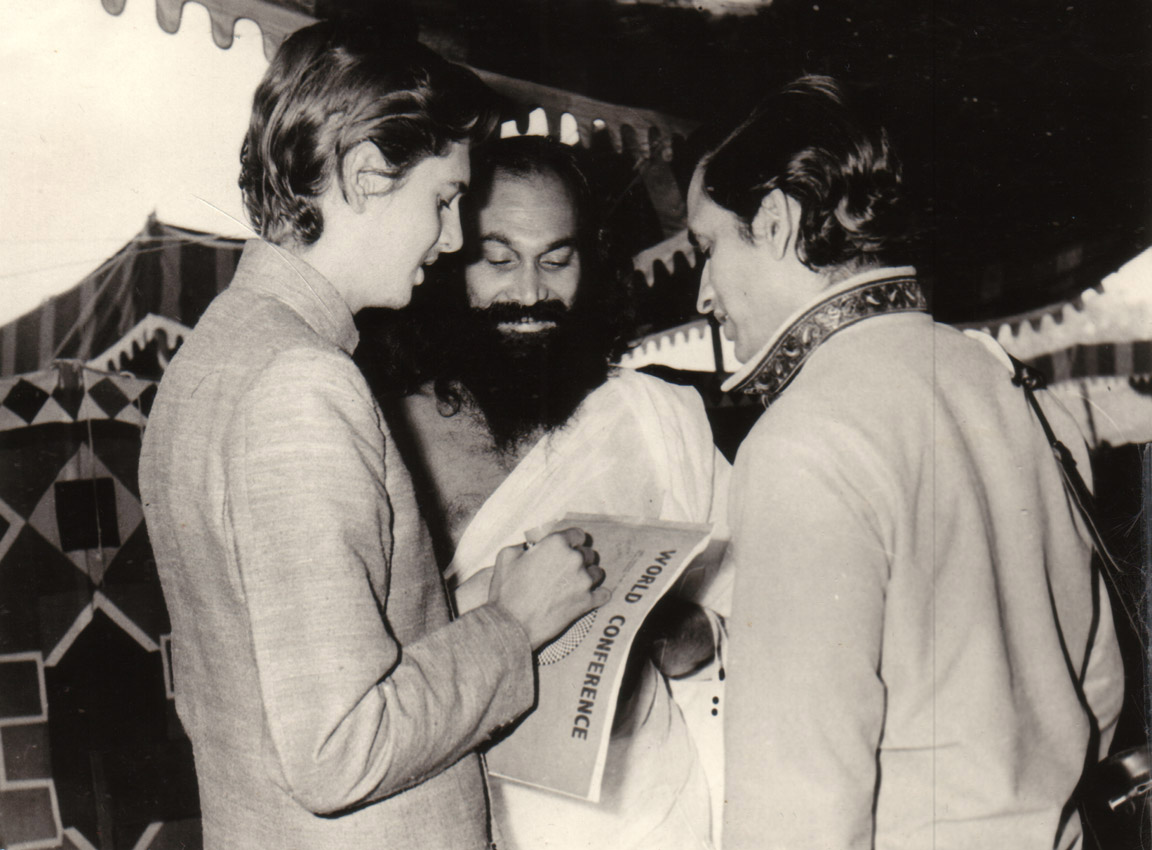

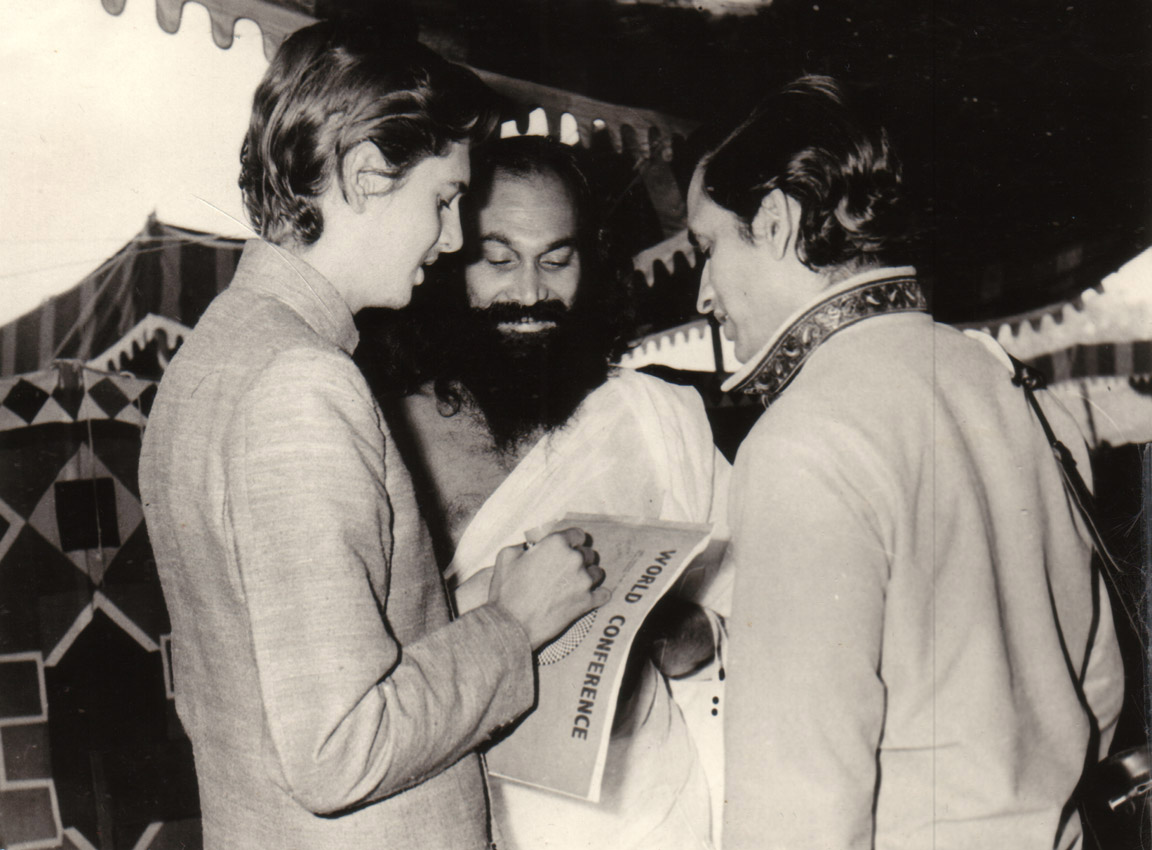

World Conference on Scientific Yoga, New Delhi

In December 1970 Christopher Hills, his son John, and Kevin Kingsland organized the world's first World Conference on Scientific Yoga (WCSY) in New Delhi, bringing 50 Western scientists together with 800 of India's leading swamis, yogis and lamas to discuss their research and establish a network for the creation of a World Yoga University. The conference generated some controversy when Indian politics intersected with religion, particularly the concept of ''Christ Yoga'', a book Hills had written linking Christ's teachings to those of

The conference generated some controversy when Indian politics intersected with religion, particularly the concept of ''Christ Yoga'', a book Hills had written linking Christ's teachings to those of Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha (),*

*

*

was a wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism. According to Buddhist legends, he was ...

and the Vedas

FIle:Atharva-Veda samhita page 471 illustration.png, upright=1.2, The Vedas are ancient Sanskrit texts of Hinduism. Above: A page from the ''Atharvaveda''.

The Vedas ( or ; ), sometimes collectively called the Veda, are a large body of relig ...

. But the conclave nevertheless emerged as a milestone in the soon-to-be-booming migration of Indian yogis to the West. John Hills, helped by his father's prior relationship with Nehru, worked with India's Prime Minister Indira Gandhi

Indira Priyadarshini Gandhi (Given name, ''née'' Nehru; 19 November 1917 – 31 October 1984) was an Indian politician and stateswoman who served as the Prime Minister of India, prime minister of India from 1966 to 1977 and again from 1980 un ...

and the Nehrus' yoga master Dhirendra Brahmachari to steer a fractious committee of MPs, ministers and often competitive spiritual leaders from disparate religions and castes into creating a uniquely diverse and widely hailed program of events. Presenters from the West included transpersonal psychology

Transpersonal psychology, or spiritual psychology, is an area of psychology that seeks to integrate the spiritual and transcendent human experiences within the framework of modern psychology.

Evolving from the humanistic psychology movement, ...

pioneer Stanislav Grof

Stanislav Grof (born July 1, 1931) is a Czech-born American psychiatrist. Grof is one of the principal developers of transpersonal psychology and research into the use of non-ordinary states of consciousness for purposes of psychological hea ...

and Sidney Jourard

Sidney Marshall Jourard (1926–1974) was a Canadian psychologist, professor, and writer. He was best known as the author of the books ''The Transparent Self'' and ''Healthy Personality: An Approach From the Viewpoint of Humanistic Psychology'', ...

who compared their research in lively sessions with Indian scholars, scientists, philosophers and yogis such as B.K.S. Iyengar

Bellur Krishnamachar Sundararaja Iyengar (14 December 1918 – 20 August 2014) was an Indian teacher of yoga and author. He is the founder of the style of yoga as exercise, known as "Iyengar Yoga", and was considered one of the foremost Modern ...

, Shri K. Pattabhi Jois

K. Pattabhi Jois (26 July 1915 – 18 May 2009) was an Indian yoga guru who developed and popularized the flowing style of yoga as exercise known as Ashtanga (vinyasa) yoga. In 1948, Jois established the Ashtanga Yoga Research Institute in My ...

, Jiddu Krishnamurti

Jiddu Krishnamurti ( ; 11 May 1895 – 17 February 1986) was an Indian Philosophy, philosopher, speaker, writer, and Spirituality, spiritual figure. Adopted by members of the Theosophy, Theosophical tradition as a child, he was raised to fill ...

, Swami Satchidananda

Satchidananda Saraswati (; 22 December 1914 – 19 August 2002), born C. K. Ramaswamy Gounder and known as Swami Satchidananda, was an Indian yoga guru and religious teacher, who gained following in the West. He founded his own brand of Integra ...

, Padma Bhushan Murugappa Channaveerappa Modi, R.R. Diwaker, Swami Rama

Swami Rama (; 1925 – 13 November 1996) was an Indian yoga guru. He moved to the US in 1969, initially teaching yoga at the YMCA, and founding the Himalayan Institute of Yoga Science and Philosophy in Illinois in 1971; its headquarters moved t ...

, Acharya Dharma Deva Vidya Martand, Kaivalyadhama Health and Yoga Research Center

Kaivalyadhama, officially the Kaivalyadhama Health and Yoga Research Centre, is a spiritual, therapeutic, and research centre founded by Swami Kuvalayananda in 1924. It aims to coordinate ancient yogic arts and tradition with modern science. Ku ...

and yoga hospital founder G. S. Melkote,

The actor James Coburn

James Harrison Coburn III (August 31, 1928 – November 18, 2002) was an American film and television actor who was featured in more than 70 films, largely action roles, and made 100 television appearances during a 45-year career.AllmoviBi ...

, a yoga and martial arts practitioner, described the World Conference on Scientific Yoga as "Very rewarding for me, definitely worth the time and money getting here."

During the conference, Dhirendra Brahmachari presided over the wedding of organizer Kevin Kingsland and yoga teacher Venika Mehra. James Coburn also attended. Kevin and Venika Kingsland went on to establish various Centres for Human Communication in the UK, USA and India, teaching yoga, human communication and promoting community consciousness.

Post-conference, the select delegates' presentations were published in ''CHAKRA'' magazine, founded with the help of Tantra

Tantra (; ) is an esoteric yogic tradition that developed on the India, Indian subcontinent beginning in the middle of the 1st millennium CE, first within Shaivism and later in Buddhism.

The term ''tantra'', in the Greater India, Indian tr ...

scholar Ajit Mookerjee and Indian art patron Virendra Kumar and edited by John Hills whose first venture in publishing was mentored by Baburao Patel

Baburao Patel (1904–1982) was an Indian publisher and writer, associated with films and politics.

Career

Baburao: A Pioneer of Indian Cinema. Baburao was a key figure in the early days of Indian cinema. He started his career as a journalist ...

M.P., editor of ''Filmindia

''filmindia'' is an Indian monthly magazine covering Indian cinema and published in English language.

Started by Baburao Patel in 1935, ''filmindia'' was the first English film periodical to be published from Bombay. The magazine was reportedly ...

'' and ''Mother India

''Mother India'' is a 1957 Indian epic drama film, directed by Mehboob Khan and starring Nargis, Sunil Dutt, Rajendra Kumar and Raaj Kumar. A remake of Khan's earlier film '' Aurat'' (1940), it is the story of a poverty-stricken village wo ...

'' magazines.

The conference was deemed a success and Christopher Hills was elected by a majority of the delegates to establish a World Yoga University somewhere on the planet. A mission that would take him from the United Kingdom to the United States.

University of the Trees

Christopher Hills visited his friend Laura Huxley who urged him to move to the United States where he settled inBoulder Creek, California

Boulder Creek () is a small rural mountain community in the coastal Santa Cruz Mountains. It is a census-designated place (CDP) in Santa Cruz County, California, Santa Cruz County, California, with a population of 5,429 as of the 2020 United Sta ...

, and became a U.S. citizen. There, amidst the ancient redwoods

Sequoioideae, commonly referred to as redwoods, is a subfamily of coniferous trees within the family Cupressaceae, that range in the northern hemisphere. It includes the largest and tallest trees in the world. The trees in the subfamily are a ...

, he founded in 1973, an accredited college, University of the Trees, an alternative education and research center for the social sciences to study the laws of nature and their relation to human consciousness. Students lived on campus and studied subjects as diverse as the pseudoscientific alternative medicine radionics

Radionics—also called electromagnetic therapy (EMT) and the Abrams method—is a form of alternative medicine that claims that disease can be diagnosed and treated by applying electromagnetic radiation (EMR), such as radio waves, to the bod ...

and dowsing

Dowsing is a type of divination employed in attempts to locate ground water, buried metals or ores, gemstones, Petroleum, oil, claimed radiations (radiesthesia),As translated from one preface of the Kassel experiments, "roughly 10,000 active do ...

(Hills was a well-known diviner), meditation, hatha yoga

Hatha yoga (; Sanskrit हठयोग, International Alphabet of Sanskrit Transliteration, IAST: ''haṭhayoga'') is a branch of yoga that uses physical techniques to try to preserve and channel vital force or energy. The Sanskrit word ह� ...

, the Vedas, and early forms of social networking he called "Group Consciousness".

The campus housed University of the Trees Press which published Christopher Hills' writings and the research of a number of resident students who obtained degrees at the university and wrote books on light & color frequencies and the pseudoscience of radionics

Radionics—also called electromagnetic therapy (EMT) and the Abrams method—is a form of alternative medicine that claims that disease can be diagnosed and treated by applying electromagnetic radiation (EMR), such as radio waves, to the bod ...

. Hills coauthore"Conduct Your Own Awareness Sessions"

with new-age author Robert B. Stone to whom the University later bestowed an honorary PhD. A small workshop produced pendulums for dowsing and a line of negative ion generators. From this base in California, Hills extended his hospitality to scientists, writers, philosophers and scholars such as

Alan Watts

Alan Wilson Watts (6 January 1915 – 16 November 1973) was a British and American writer, speaker, and self-styled "philosophical entertainer", known for interpreting and popularising Buddhist, Taoist, and Hinduism, Hindu philosophy for a Wes ...

, Edgar Mitchell

Edgar Dean "Ed" Mitchell (September 17, 1930 – February 4, 2016) was a United States Navy officer and United States Naval Aviator, aviator, test pilot, Aerospace engineering, aeronautical engineer, Ufology, ufologist, and NASA astronaut. ...

, Barbara Marx Hubbard, Allen Ginsberg

Irwin Allen Ginsberg (; June 3, 1926 – April 5, 1997) was an American poet and writer. As a student at Columbia University in the 1940s, he began friendships with Lucien Carr, William S. Burroughs and Jack Kerouac, forming the core of th ...

, Thelma Moss

Thelma Moss (nee Schnee, January 6, 1918 – February 1, 1997) was an American actress, and later a psychologist and parapsychologist, best known for her work on Kirlian photography and the human aura.

Biography

Born Thelma Schnee, a nat ...

, Hiroshi Motoyama

was a Japanese parapsychologist, spiritual instructor and author whose primary topic was spiritual self-cultivation and the relationship between the mind and body. Motoyama emphasized the meditative practices of Samkhya/Yoga, karma, reincarnati ...

, Haridas Chaudhuri

Haridas Chaudhuri (May 1913 – 1975) was an Indian integral philosopher. He was a correspondent with Sri Aurobindo and the founder of the California Institute of Integral Studies (CIIS).

Early life and career

He was born in May 1913 in Shyam ...

, Sri Lanka president Ranasinghe Premadasa, Menninger Foundation's Swami Rama

Swami Rama (; 1925 – 13 November 1996) was an Indian yoga guru. He moved to the US in 1969, initially teaching yoga at the YMCA, and founding the Himalayan Institute of Yoga Science and Philosophy in Illinois in 1971; its headquarters moved t ...

, Evarts G. Loomis, Viktoras Kulvinskas

The Hippocrates Health Institute (HHI) is a nonprofit organization in West Palm Beach, Florida, US, originally co-founded in 1956 in Stoneham, Massachusetts, by Lithuanian-born Viktoras Kulvinskas and Ann Wigmore.

The Hippocrates Health Institu ...

, Max Lüscher, Marcia Moore

Marcia Moore (May 22, 1928 – January 14, 1979) was an American writer, astrologer and yoga teacher brought to national attention in 1965 through Jess Stearn's book ''Yoga, Youth, and Reincarnation''. She was an advocate and researcher of th ...

.

Supersensonics

Within the campus, Hills founded an experimental laboratory, managed by physicist Dr. Robert Massy, to develop his theories on the Electro Vibratory Body – documenting what Hills' colleague Stanford University's William A. Tiller Ph.D, calls "subtle energies" or "psychoenergetics". Shortly before he diedradionics

Radionics—also called electromagnetic therapy (EMT) and the Abrams method—is a form of alternative medicine that claims that disease can be diagnosed and treated by applying electromagnetic radiation (EMR), such as radio waves, to the bod ...

pioneer George de la Warr donated a substantial portion of his research files, library and instruments to Christopher Hills. In 1975 Hills wrote the book ''Supersensonics: The Science of Radiational Paraphysics'', widely considered "The Bible of dowsing" The book covers subjects including divining, telepathy, The I Ching, Egypt's Pyramids, Biblical miracles and discusses the value of low level extrasensory phenomena vs higher levels of insight, wisdom and consciousness. ''New Age Journal

''Whole Living'' was a Health#Maintaining health, health and lifestyle (sociology), lifestyle magazine geared towards "natural health, personal growth, and well-being," a concept the publishers refer to as "whole living." The magazine became a p ...

'' magazine called ''Supersensonics'' "A short course in miracles for scientist and seeker alike."

International philanthropy

With theCold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

in full swing liberation from the evils of totalitarianism was a constant theme in Hills writings. He lobbied hard against the KGB

The Committee for State Security (, ), abbreviated as KGB (, ; ) was the main security agency of the Soviet Union from 1954 to 1991. It was the direct successor of preceding Soviet secret police agencies including the Cheka, Joint State Polit ...

's persecution of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn. (11 December 1918 – 3 August 2008) was a Soviet and Russian author and Soviet dissidents, dissident who helped to raise global awareness of political repression in the Soviet Union, especially the Gulag pris ...

and the internal exile with police surveillance of Andrei Sakharov

Andrei Dmitrievich Sakharov (; 21 May 192114 December 1989) was a Soviet Physics, physicist and a List of Nobel Peace Prize laureates, Nobel Peace Prize laureate, which he was awarded in 1975 for emphasizing human rights around the world.

Alt ...

and the denial of an exit visa for Natan Sharansky

Natan Sharansky (; born 20 January 1948) is an Israeli politician, human rights activist, and author. He served as Chairman of the Executive for the Jewish Agency for Israel, Jewish Agency from June 2009 to August 2018, and currently serves as ...

's emigration to Israel. Christopher Hills' lifelong crusade against dictatorships and Man's inhumanity was manifested in the book ''Rise of the Phoenix'' while his passionate beliefs against deficit spending were set forth in a book on the global economy—''The Golden Egg''. A recurring theme throughout all Christopher Hills' approaches to world, local and family problems was a process he developed called "Creative Conflict"—the same principles of solving differences between individuals, political parties and even nations that Hills had debated with Adlai Stevenson, Nehru and Luis Kutner.

Throughout the seventies and eighties Hills focused on international affairs, particularly the emergence of democracy in the Soviet Republics, eventually traveling to Russia to meet with

Christopher Hills' lifelong crusade against dictatorships and Man's inhumanity was manifested in the book ''Rise of the Phoenix'' while his passionate beliefs against deficit spending were set forth in a book on the global economy—''The Golden Egg''. A recurring theme throughout all Christopher Hills' approaches to world, local and family problems was a process he developed called "Creative Conflict"—the same principles of solving differences between individuals, political parties and even nations that Hills had debated with Adlai Stevenson, Nehru and Luis Kutner.

Throughout the seventies and eighties Hills focused on international affairs, particularly the emergence of democracy in the Soviet Republics, eventually traveling to Russia to meet with Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet and Russian politician who served as the last leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to dissolution of the Soviet Union, the country's dissolution in 1991. He served a ...

where he joined the Soviet Peace Committee The Soviet Peace Committee (SPC, also known as Soviet Committee for the Defense of Peace, SCDP, ) was a state-sponsored organization responsible for coordinating peace movements active in the Soviet Union. It was founded in 1949 and existed until t ...

. U.S. Presidents Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

and George H. W. Bush

George Herbert Walker BushBefore the outcome of the 2000 United States presidential election, he was usually referred to simply as "George Bush" but became more commonly known as "George H. W. Bush", "Bush Senior," "Bush 41," and even "Bush th ...

bestowed awards on Hills for his commitment to democratic freedom and his humanitarian support for victims of oppression.

The Christopher Hills Foundation donated more than $9 million worth of spirulina products to charitable organizations in the U.S. and abroad. When the Soviet Union had occupied Afghanistan, Hills learned from his friends in Peshawar that Afghan freedom fighter Ahmad Shah Masoud's mujahadeen troops as well as Tajik and Pashtun