Christianity And Violence on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The

The

J. Denny Weaver, Professor Emeritus of Religion at Bluffton University, suggests that there are numerous evolving views on violence and nonviolence throughout the history of Christian theology. According to the view of many historians, the Constantinian shift turned Christianity from a persecuted into a persecuting religion.

Miroslav Volf has identified the intervention of a "new creation", as in the

J. Denny Weaver, Professor Emeritus of Religion at Bluffton University, suggests that there are numerous evolving views on violence and nonviolence throughout the history of Christian theology. According to the view of many historians, the Constantinian shift turned Christianity from a persecuted into a persecuting religion.

Miroslav Volf has identified the intervention of a "new creation", as in the

In Ulrich Luz's formulation; "After Constantine, the Christians too had a responsibility for war and peace. Already

In Ulrich Luz's formulation; "After Constantine, the Christians too had a responsibility for war and peace. Already

The

The

In the

In the

Exodus 22:18

states that "Thou shalt not permit a sorceress to live". Many people faced

Spiritual Aroma: Religion and Politics

''American Anthropologist'', New Series, Vol. 83, No. 3, pp. 582–601

"Gary North on D. James Kennedy"

, Chalcedon Blog, 6 September 2007. With these exceptions, all Christian faith groups now condemn slavery, and they see the practice of slavery as being incompatible with basic Christian principles.

A strain of hostility towards

A strain of hostility towards

Christians

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the world. The words '' Christ'' and ''C ...

have had diverse attitudes towards violence

Violence is characterized as the use of physical force by humans to cause harm to other living beings, or property, such as pain, injury, disablement, death, damage and destruction. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines violence a ...

and nonviolence

Nonviolence is the personal practice of not causing harm to others under any condition. It may come from the belief that hurting people, animals and/or the environment is unnecessary to achieve an outcome and it may refer to a general philosoph ...

over time. Both currently and historically, there have been four attitudes towards violence and war and four resulting practices of them within Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, which states that Jesus in Christianity, Jesus is the Son of God (Christianity), Son of God and Resurrection of Jesus, rose from the dead after his Crucifixion of Jesus, crucifixion, whose ...

: non-resistance

Nonresistance (or non-resistance) is "the practice or principle of not resisting authority, even when it is unjustly exercised". At its core is discouragement of, even opposition to, physical resistance to an enemy. It is considered as a form of pr ...

, Christian pacifism

Christian pacifism is the Christian theology, theological and Christian ethics, ethical position according to which pacifism and non-violence have both a scriptural and rational basis for Christians, and affirms that any form of violence is inco ...

, just war

The just war theory () is a doctrine, also referred to as a tradition, of military ethics that aims to ensure that a war is morally justifiable through a series of criteria, all of which must be met for a war to be considered just. It has bee ...

, and preventive war

A preventive war is an armed conflict "initiated in the belief that military conflict, while not imminent, is inevitable, and that to delay would involve greater risk." The party which is being attacked has a latent threat capability or it has sh ...

(Holy war

A religious war or a war of religion, sometimes also known as a holy war (), is a war and conflict which is primarily caused or justified by differences in religion and beliefs. In the modern period, there are frequent debates over the extent t ...

, e.g., the Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding t ...

). In the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

, the early church

Early Christianity, otherwise called the Early Church or Paleo-Christianity, describes the historical era of the Christian religion up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325. Christianity spread from the Levant, across the Roman Empire, and bey ...

adopted a nonviolent stance when it came to war

War is an armed conflict between the armed forces of states, or between governmental forces and armed groups that are organized under a certain command structure and have the capacity to sustain military operations, or between such organi ...

because the imitation of Jesus's sacrificial life was preferable to it. The concept of "Just War", the belief that limited uses of war were acceptable, originated in the writings of earlier non-Christian Roman and Greek thinkers such as Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, orator, writer and Academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises tha ...

and Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

. Later, this theory was adopted by Christian thinkers such as St Augustine, who like other Christians, borrowed much of the just war concept from Roman law

Roman law is the law, legal system of ancient Rome, including the legal developments spanning over a thousand years of jurisprudence, from the Twelve Tables (), to the (AD 529) ordered by Eastern Roman emperor Justinian I.

Roman law also den ...

and the works of Roman writers like Cicero. Even though "Just War" concept was widely accepted early on, warfare was not regarded as a virtuous activity and expressing concern for the salvation of those who killed enemies in battle, regardless of the cause for which they fought, was common. Concepts such as "Holy war", whereby fighting itself might be considered a penitential and spiritually meritorious act, did not emerge before the 11th century.

Bible

The

The Bible

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) originally writt ...

contains several texts which encourage, command, condemn, reward, punish, regulate and describe acts of violence.

Leigh Gibson and Shelly Matthews, associate professor of religion at Furman University

Furman University is a private university in Greenville, South Carolina, United States. Founded in 1826 and named after Baptist pastor Richard Furman, the Liberal arts college, liberal arts university is the oldest private institution of higher l ...

, write that some scholars, such as René Girard

René Noël Théophile Girard (; ; 25 December 1923 – 4 November 2015) was a French-American historian, literary critic, and philosopher of social science whose work belongs to the tradition of philosophical anthropology. Girard was the a ...

, "lift up the New Testament

The New Testament (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus, as well as events relating to Christianity in the 1st century, first-century Christianit ...

as somehow containing the antidote for Old Testament

The Old Testament (OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew and occasionally Aramaic writings by the Isr ...

violence". According to John Gager, such an analysis risks advocating the views of the heresiarch Marcion of Sinope

Marcion of Sinope (; ; ) was a theologian in early Christianity. Marcion preached that God had sent Jesus Christ, who was distinct from the "vengeful" God ( Demiurge) who had created the world. He considered himself a follower of Paul the Apost ...

(c. 85–160), who made a distinction between the God of the Old Testament responsible for violence and the God of mercy found in the New Testament.

Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2October 186930January 1948) was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethics, political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful Indian ...

embraced the concept of nonviolence which he had found in both Indian Religions

Indian religions, sometimes also termed Dharmic religions or Indic religions, are the religions that originated in the Indian subcontinent. These religions, which include Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism, and Sikhism,Adams, C. J."Classification o ...

and the New Testament (e.g. Sermon on the Mount

The Sermon on the Mount ( anglicized from the Matthean Vulgate Latin section title: ) is a collection of sayings spoken by Jesus of Nazareth found in the Gospel of Matthew (chapters 5, 6, and 7). that emphasizes his moral teachings. It is th ...

), which he then utilized in his strategy for social and political struggles.

Christian violence

J. Denny Weaver, Professor Emeritus of Religion at Bluffton University, suggests that there are numerous evolving views on violence and nonviolence throughout the history of Christian theology. According to the view of many historians, the Constantinian shift turned Christianity from a persecuted into a persecuting religion.

Miroslav Volf has identified the intervention of a "new creation", as in the

J. Denny Weaver, Professor Emeritus of Religion at Bluffton University, suggests that there are numerous evolving views on violence and nonviolence throughout the history of Christian theology. According to the view of many historians, the Constantinian shift turned Christianity from a persecuted into a persecuting religion.

Miroslav Volf has identified the intervention of a "new creation", as in the Second Coming

The Second Coming (sometimes called the Second Advent or the Parousia) is the Christianity, Christian and Islam, Islamic belief that Jesus, Jesus Christ will return to Earth after his Ascension of Jesus, ascension to Heaven (Christianity), Heav ...

, as a particular aspect of Christianity that generates violence. Writing about the latter, Volf says: "Beginning at least with Constantine's conversion, the followers of the Crucified have perpetrated gruesome acts of violence under the sign of the cross. Over the centuries, the seasons of Lent

Lent (, 'Fortieth') is the solemn Christianity, Christian religious moveable feast#Lent, observance in the liturgical year in preparation for Easter. It echoes the 40 days Jesus spent fasting in the desert and enduring Temptation of Christ, t ...

and Holy Week

Holy Week () commemorates the seven days leading up to Easter. It begins with the commemoration of Triumphal entry into Jerusalem, Christ's triumphal entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday, marks the betrayal of Jesus on Spy Wednesday (Holy Wednes ...

were, for the Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

, times of fear and trepidation. Muslim

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

s also associate the cross with violence; crusaders' rampages were undertaken under the sign of the cross."

The statement attributed to Jesus " I come not to bring peace, but to bring a sword" has been interpreted by some as a call to arms for Christians. Mark Juergensmeyer

Mark Juergensmeyer (born 1940 in Carlinville, Illinois) is an American Sociology, sociologist and scholar specialized in global studies and religious studies, and a writer best known for his studies on comparative religion, religious violence, an ...

argues that "despite its central tenets of love and peace, Christianity—like most traditions—has always had a violent side. The bloody history of the tradition has provided disturbing images and violent conflict is vividly portrayed in the Bible. This history and these biblical images have provided the raw material for theologically justifying the violence of contemporary Christian groups. For example, attacks on abortion clinics have been viewed not only as assaults on a practice that Christians regard as immoral, but also as skirmishes in a grand confrontation between forces of evil and good that has social and political implications", sometimes referred to as spiritual warfare

Spiritual warfare is the Christian concept of fighting against the work of preternatural evil forces. It is based on the belief in evil spirits, or demons, that are said to intervene in human affairs in various ways. Although spiritual warfa ...

.

Higher law has been used to justify violence by Christians.

Historically, according to René Girard, many Christians embraced violence when it became the state religion of the Roman Empire: "Beginning with Constantine, Christianity triumphed at the level of the state and soon began to cloak with its authority persecutions similar to those in which the early Christians were victims."

Wars

Attitudes towards the military before Constantine

The study of Christian participation in military service in the pre-Constantinian era has been highly contested and has generated a great deal of literature. Through most of the twentieth century, a consensus was formed aroundAdolf von Harnack

Carl Gustav Adolf von Harnack (born Harnack; 7 May 1851 – 10 June 1930) was a Baltic German Lutheran theologian and prominent Church historian. He produced many religious publications from 1873 to 1912 (in which he is sometimes credited ...

's view that the early church was pacifist

Pacifism is the opposition to war or violence. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaigner Émile Arnaud and adopted by other peace activists at the tenth Universal Peace Congress in Glasgow in 1901. A related term is ''a ...

, that during the second and third centuries, a growing accommodation of military service occurred, and by the time of Constantine, a just war ethic had arisen.

This consensus was challenged mostly by the work of John Helgeland in the 1970s and 1980s. He said that most of the early Christians opposed military service because they refused to practice the Roman religion and they also refused to perform the rituals of the Roman army, not because they were against killing. Helgeland also stated that there is a diversity of voices in the written literature, as well as evidence of a diversity of practices by Christians. George Kalantzis, Professor of Theology at Wheaton College, sided with Harnack in the debate writing that "literary evidence confirms the very strong internal coherence of the Church's non-violent stance for the first three centuries."

David Hunter has concluded that a "new consensus" has emerged and it includes aspects of Helgeland's and Harnack's views. Hunter suggests that the early Christians based their opposition to military service upon both their "aboherrence of Roman army religion" (Helgeland's view) and their opposition to bloodshed (Harnack's view). Hunter notes that there is evidence that by the 2nd century Christian practices had started to diverge from the theological principles espoused in early Christian literature. Hunter's third point of the "new consensus" is the assertion that the just war theory

The just war theory () is a doctrine, also referred to as a tradition, of military ethics that aims to ensure that a war is morally justifiable through a series of #Criteria, criteria, all of which must be met for a war to be considered just. I ...

reflects at least one pre-Constantinian view. Finally, to these three points, Kreider added that Christian attitudes towards violence were likely varied in different geographical locations, pointing out that pro-militarist views were stronger in border areas then they were in "heartland" areas which were more strongly aligned with the Empire.

There is little evidence concerning the extent of Christian participation in the military; generalizations are usually speculation. A few gravestones of Christian soldiers have been found.

Just war

Just war theory

The just war theory () is a doctrine, also referred to as a tradition, of military ethics that aims to ensure that a war is morally justifiable through a series of #Criteria, criteria, all of which must be met for a war to be considered just. I ...

is a doctrine of military ethics of Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of Roman civilization

*Epistle to the Romans, shortened to Romans, a letter w ...

philosophical and Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

origin studied by moral theologians, ethicists, and international policy makers, that holds that a conflict can and ought to meet the criteria of philosophical, religious or political justice, provided it follows certain conditions.

The concept of justification for war under certain conditions goes back at least to Roman and Greek thinkers such as Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, orator, writer and Academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises tha ...

and Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

. However its importance is connected to Christian medieval theory beginning from Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; ; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430) was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Africa. His writings deeply influenced the development of Western philosop ...

and Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas ( ; ; – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest, the foremost Scholasticism, Scholastic thinker, as well as one of the most influential philosophers and theologians in the W ...

.

According to Jared Diamond

Jared Mason Diamond (born September 10, 1937) is an American scientist, historian, and author. In 1985 he received a MacArthur Genius Grant, and he has written hundreds of scientific and popular articles and books. His best known is '' Guns, G ...

, Augustine of Hippo played a critical role in delineating Christian thinking about what constitutes a just war, and about how to reconcile Christian teachings of peace with the need for war in certain situations. Partly inspired by Cicero's writings, Augustine held that war could be justified in order to preserve the state, rectify wrongs by neighboring nations, and expand the state if a tyrant will lose power in doing so.

In Ulrich Luz's formulation; "After Constantine, the Christians too had a responsibility for war and peace. Already

In Ulrich Luz's formulation; "After Constantine, the Christians too had a responsibility for war and peace. Already Celsus

Celsus (; , ''Kélsos''; ) was a 2nd-century Greek philosopher and opponent of early Christianity. His literary work '' The True Word'' (also ''Account'', ''Doctrine'' or ''Discourse''; Greek: )Hoffmann p.29 survives exclusively via quotati ...

asked bitterly whether Christians, by aloofness from society, wanted to increase the political power of wild and lawless barbarian

A barbarian is a person or tribe of people that is perceived to be primitive, savage and warlike. Many cultures have referred to other cultures as barbarians, sometimes out of misunderstanding and sometimes out of prejudice.

A "barbarian" may ...

s. His question constituted a new actuality; from now on, Christians and churches had to choose between the testimony of the gospel, which included renunciation of violence, and responsible participation in political power, which was understood as an act of love toward the world." Augustine of Hippo's ''Epistle to Marcellinus'' (Ep 138) is the most influential example of the "new type of interpretation".

Just war theorists combine both a moral abhorrence towards war with a readiness to accept that war may sometimes be necessary. The criteria of the just war tradition act as an aid to determining whether resorting to arms is morally permissible. Just War theories are attempts "to distinguish between justifiable and unjustifiable uses of organized armed forces"; they attempt "to conceive of how the use of arms might be restrained, made more humane, and ultimately directed towards the aim of establishing lasting peace and justice."

The just war tradition addresses the morality of the use of force in two parts: when it is right to resort to armed force (the concern of ''jus ad bellum

' ( or ), literally "right to war" in Latin, refers to "the conditions under which States may resort to war or to the use of armed force in general". Jus ad bellum is one pillar of just war theory. Just war theory states that war should only be ...

'') and what is acceptable in using such force (the concern of ''jus in bello

The law of war is a component of international law that regulates the conditions for initiating war (''jus ad bellum'') and the conduct of hostilities (''jus in bello''). Laws of war define sovereignty and nationhood, states and territories, ...

''). In more recent years, a third category—''jus post bellum

''Jus post bellum'' ( ; Latin for "Justice after war") is a concept that deals with the morality of the termination phase of war, including the responsibility to rebuild. The idea has some historical pedigree as a concept in just war theory. In ...

''—has been added, which governs the justice of war termination and peace agreements, as well as the prosecution of war criminals.

Holy War

In 1095, at theCouncil of Clermont

The Council of Clermont was a mixed synod of ecclesiastics and laymen of the Catholic Church, called by Pope Urban II and held from 17 to 27 November 1095 at Clermont, Auvergne, at the time part of the Duchy of Aquitaine.

While the council ...

, Pope Urban II

Pope Urban II (; – 29 July 1099), otherwise known as Odo of Châtillon or Otho de Lagery, was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 12 March 1088 to his death. He is best known for convening the Council of Clermon ...

declared that some wars could be deemed as not only a '' bellum iustum'' ("just war"), but could, in certain cases, rise to the level of a ''bellum sacrum'' (holy war). Jill Claster, dean of New York University College of Arts and Science, characterizes this as a "remarkable transformation in the ideology of war", shifting the justification of war from being not only "just" but "spiritually beneficial". Thomas Murphy examined the Christian concept of Holy War

A religious war or a war of religion, sometimes also known as a holy war (), is a war and conflict which is primarily caused or justified by differences in religion and beliefs. In the modern period, there are frequent debates over the extent t ...

, asking "how a culture formally dedicated to fulfilling the injunction to 'love thy neighbor as thyself' could move to a point where it sanctioned the use of violence against the alien both outside and inside society". The religious sanctioning of the concept of "holy war" was a turning point in Christian attitudes towards violence; "Pope Gregory VII

Pope Gregory VII (; 1015 – 25 May 1085), born Hildebrand of Sovana (), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 22 April 1073 to his death in 1085. He is venerated as a saint in the Catholic Church.

One of the great ...

made the Holy War possible by drastically altering the attitude of the church towards war... Hitherto a knight could obtain remission of sins only by giving up arms, but Urban invited him to gain forgiveness 'in and through the exercise of his martial skills'." A holy war was defined by the Roman Catholic Church as "war that is not only just, but justifying; that is, a war that confers positive spiritual merit on those who fight in it".

In the 12th century, Bernard of Clairvaux

Bernard of Clairvaux, Cistercians, O.Cist. (; 109020 August 1153), venerated as Saint Bernard, was an abbot, Mysticism, mystic, co-founder of the Knights Templar, and a major leader in the reform of the Benedictines through the nascent Cistercia ...

wrote: "'The knight of Christ may strike with confidence and die yet more confidently; for he serves Christ when he strikes, and saves himself when he falls.... When he inflicts death, it is to Christ's profit, and when he suffers death, it is his own gain."

Jonathan Riley-Smith

Jonathan Simon Christopher Riley-Smith (27 June 1938 – 13 September 2016) was a historian of the Crusades, and, between 1994 and 2005, Dixie Professor of Ecclesiastical History at Cambridge. He was a Fellow of Emmanuel College, Cambridge.

Ea ...

writes,

The consensus among Christians on the use of violence has changed radically since the crusades were fought. The just war theory prevailing for most of the last two centuries—that violence is an evil which can in certain situations be condoned as the lesser of evils—is relatively young. Although it has inherited some elements (the criteria of legitimate authority, just cause, right intention) from the older war theory that first evolved around a.d. 400, it has rejected two premises that underpinned all medieval just wars, including crusades: first, that violence could be employed on behalf of Christ's intentions for mankind and could even be directly authorized by him; and second, that it was a morally neutral force which drew whatever ethical coloring it had from the intentions of the perpetrators.

Genocidal warfare

The

The Biblical

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) biblical languages ...

account of Joshua

Joshua ( ), also known as Yehoshua ( ''Yəhōšuaʿ'', Tiberian Hebrew, Tiberian: ''Yŏhōšuaʿ,'' Literal translation, lit. 'Yahweh is salvation'), Jehoshua, or Josue, functioned as Moses' assistant in the books of Book of Exodus, Exodus and ...

and the Battle of Jericho was used to justify genocide

Genocide is violence that targets individuals because of their membership of a group and aims at the destruction of a people. Raphael Lemkin, who first coined the term, defined genocide as "the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group" by ...

against Catholics

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

by Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

. Daniel Chirot, professor of Russian

Russian(s) may refer to:

*Russians (), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*A citizen of Russia

*Russian language, the most widely spoken of the Slavic languages

*''The Russians'', a b ...

and Eurasian studies at the University of Washington

The University of Washington (UW and informally U-Dub or U Dub) is a public research university in Seattle, Washington, United States. Founded in 1861, the University of Washington is one of the oldest universities on the West Coast of the Uni ...

, interprets 1 Samuel

The Book of Samuel () is a book in the Hebrew Bible, found as two books (1–2 Samuel) in the Old Testament. The book is part of the Deuteronomistic history, a series of books (Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings) that constitute a theological ...

15:1–3 as "the sentiment, so clearly expressed, that because a historical wrong was committed, justice demands genocidal retribution."

Inquisition

The Inquisition was a group of institutions within the judicial system of theCatholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

whose aim was to combat heresy

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, particularly the accepted beliefs or religious law of a religious organization. A heretic is a proponent of heresy.

Heresy in Heresy in Christian ...

The Spanish Inquisition

The Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition () was established in 1478 by the Catholic Monarchs of Spain, Catholic Monarchs, King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile and lasted until 1834. It began toward the end of ...

is often cited in popular literature and history as an example of Catholic intolerance and repression. The total number of people who were processed by the Inquisition throughout its history was approximately 150,000; applying the percentages of executions that appeared in the trials of 1560–1700—about 2%—the approximate total would be about 3,000 of them were put to death. However, the actual death toll was probably higher, according to the data which Dedieu and García Cárcel provided to the tribunals of Toledo and Valencia

Valencia ( , ), formally València (), is the capital of the Province of Valencia, province and Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Valencian Community, the same name in Spain. It is located on the banks of the Turia (r ...

, respectively. It is likely that between 3,000 and 5,000 people were executed. About 50 people were executed by the Mexican Inquisition

The Mexican Inquisition was an extension of the Spanish Inquisition into New Spain. The Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire was not only a political event for the Spanish, but a religious event as well. In the early 16th century, the Protesta ...

. Included in that total are 29 people who were executed as "Judaizers

The Judaizers were a faction of the Jewish Christians, both of Jewish and non-Jewish origins, who regarded the Levitical laws of the Old Testament as still binding on all Christians. They tried to enforce Jewish circumcision upon the Gentile ...

" between 1571 and 1700 out of 324 people who were prosecuted for practicing the Jewish religion.

In the

In the Portuguese Inquisition

The Portuguese Inquisition (Portuguese language, Portuguese: ''Inquisição Portuguesa''), officially known as the General Council of the Holy Office of the Inquisition in Portugal, was formally established in Kingdom of Portugal, Portugal in 15 ...

, the major targets were people who had converted from Judaism

Judaism () is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic, Monotheism, monotheistic, ethnic religion that comprises the collective spiritual, cultural, and legal traditions of the Jews, Jewish people. Religious Jews regard Judaism as their means of o ...

to Catholicism

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

, the Conversos, also known as New Christians

New Christian (; ; ; ; ; ) was a socio-religious designation and legal distinction referring to the population of former Jews, Jewish and Muslims, Muslim Conversion to Christianity, converts to Christianity in the Spanish Empire, Spanish and Po ...

or Marranos

''Marranos'' is a term for Spanish and Portuguese Jews, as well as Navarrese jews, who converted to Christianity, either voluntarily or by Spanish or Portuguese royal coercion, during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, but who continued t ...

, because they were suspected of secretly practising Judaism. Many of these people were originally Spanish Jews

Spanish and Portuguese Jews, also called Western Sephardim, Iberian Jews, or Peninsular Jews, are a distinctive sub-group of Sephardic Jews who are largely descended from Jews who lived as New Christians in the Iberian Peninsula during the fe ...

, who had left Spain for Portugal. The number of victims of the Portuguese Inquisition is estimated to be around 40,000. One particular focus of the Spanish and Portuguese inquisitions was the issue of Jewish anusim

Anusim (, ; singular male, anús, ; singular female, anusá, , meaning "coerced") is a legal category of Jews in '' halakha'' (Jewish law) who were forced to abandon Judaism against their will, typically while forcibly converted to another re ...

and Muslim

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

converts to Catholicism, partly because these minority group

The term "minority group" has different meanings, depending on the context. According to common usage, it can be defined simply as a group in society with the least number of individuals, or less than half of a population. Usually a minority g ...

s were more numerous in Spain and Portugal than they were in many other parts of Europe, and partly because they were often considered suspect due to the assumption that they had secretly reverted to their former religions.

The Goa Inquisition was the office of the Portuguese Inquisition which operated in Portuguese India

The State of India, also known as the Portuguese State of India or Portuguese India, was a state of the Portuguese Empire founded seven years after the discovery of the sea route to the Indian subcontinent by Vasco da Gama, a subject of the ...

, as well as in the rest of the Portuguese Empire

The Portuguese Empire was a colonial empire that existed between 1415 and 1999. In conjunction with the Spanish Empire, it ushered in the European Age of Discovery. It achieved a global scale, controlling vast portions of the Americas, Africa ...

in Asia

Asia ( , ) is the largest continent in the world by both land area and population. It covers an area of more than 44 million square kilometres, about 30% of Earth's total land area and 8% of Earth's total surface area. The continent, which ...

. It was established in 1560, it was briefly suppressed from 1774 to 1778, and it was finally abolished in 1812. Based on the records that survive, H. P. Salomon and Rabbi Isaac S.D. Sassoon state that between the Inquisition's beginning in 1561 and its temporary abolition in 1774, some 16,202 persons were brought to trial by the Inquisition. Of this number, 57 of them were sentenced to death and executed, and another 64 were burned in effigy (this sentence was imposed on those persons who had either fled or died in prison; in the latter case, the executed person's remains and the effigy were both placed in a coffin and burned at the same time). Others were subjected to lesser punishments or penance, but the fate of many of those who were tried by the Inquisition is unknown.Salomon, H. P. and Sassoon, I. S. D., in Saraiva, Antonio Jose. ''The Marrano Factory. The Portuguese Inquisition and Its New Christians, 1536–1765'' (Brill, 2001 reprint/1975 revision), pp. 345–7.

During the second half of the 16th century, the Roman Inquisition

The Roman Inquisition, formally , was a system of partisan tribunals developed by the Holy See of the Catholic Church, during the second half of the 16th century, responsible for prosecuting individuals accused of a wide array of crimes according ...

was responsible for prosecuting individuals who were accused of committing a wide range of crimes which were related to religious doctrine, alternative religious doctrine

Doctrine (from , meaning 'teaching, instruction') is a codification (law), codification of beliefs or a body of teacher, teachings or instructions, taught principles or positions, as the essence of teachings in a given branch of knowledge or in a ...

or alternative religious beliefs. Out of 51,000–75,000 cases which were judged by the Inquisition in Italy after 1542, around 1,250 of them resulted in death sentence

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence ordering that an offender be punished in s ...

s.

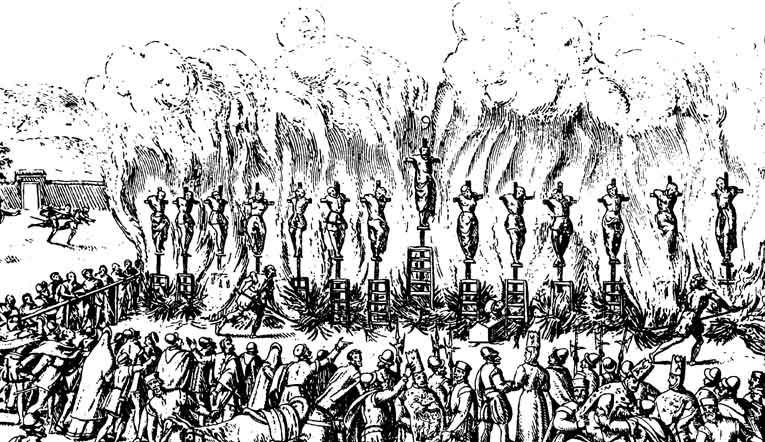

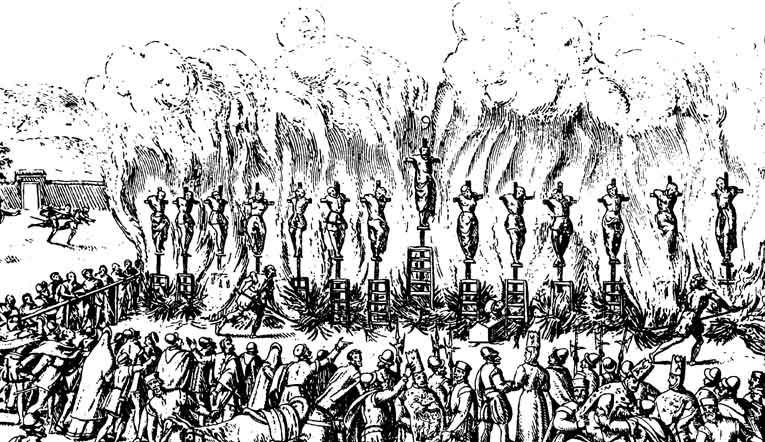

The period of witch trials in Early Modern Europe

Early modern Europe, also referred to as the post-medieval period, is the period of European history between the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, roughly the mid 15th century to the late 18th century. Histori ...

was a widespread moral panic

A moral panic is a widespread feeling of fear that some evil person or thing threatens the values, interests, or well-being of a community or society. It is "the process of arousing social concern over an issue", usually perpetuated by moral e ...

caused by the belief that malevolent Satanic witches

Witchcraft is the use of magic by a person called a witch. Traditionally, "witchcraft" means the use of magic to inflict supernatural harm or misfortune on others, and this remains the most common and widespread meaning. According to ''Enc ...

were operating as an organized threat to Christendom

The terms Christendom or Christian world commonly refer to the global Christian community, Christian states, Christian-majority countries or countries in which Christianity is dominant or prevails.SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christen ...

from the 15th to the 18th centuries. A variety of punishments was imposed upon those who were found guilty of witchcraft, including imprisonment, flogging, fines, or exile.

In the Old Testament

The Old Testament (OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew and occasionally Aramaic writings by the Isr ...

Exodus 22:18

states that "Thou shalt not permit a sorceress to live". Many people faced

capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence (law), sentence ordering that an offender b ...

if they were convicted of witchcraft during this period, either by being burned at the stake, hanged on the gallows, or beheaded. Similarly, in the New England Colonies

The New England Colonies of British America included Connecticut Colony, the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Massachusetts Bay Colony, Plymouth Colony, and the Province of New Hampshire, as well as a few smaller short-lived c ...

, people convicted of witchcraft were hanged (See Salem witch trials

The Salem witch trials were a series of hearings and prosecutions of people accused of witchcraft in Province of Massachusetts Bay, colonial Massachusetts between February 1692 and May 1693. More than 200 people were accused. Not everyone wh ...

). The scholarly consensus on the total number of executions for witchcraft ranges from 40,000 to 60,000.

The legal basis for some inquisitorial activity came from Pope Innocent IV

Pope Innocent IV (; – 7 December 1254), born Sinibaldo Fieschi, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 25 June 1243 to his death in 1254.

Fieschi was born in Genoa and studied at the universities of Parma and Bolo ...

's papal bull

A papal bull is a type of public decree, letters patent, or charter issued by the pope of the Catholic Church. It is named after the leaden Seal (emblem), seal (''bulla (seal), bulla'') traditionally appended to authenticate it.

History

Papal ...

''Ad extirpanda

''Ad extirpanda'' ("To eradicate"; named for its Latin incipit) was a papal bull promulgated on Wednesday, May 15, 1252 by Pope Innocent IV which authorized under defined circumstances the use of torture by the Inquisition as a tool for interrog ...

'' of 1252, which explicitly authorized (and defined the appropriate circumstances for) the use of torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons including corporal punishment, punishment, forced confession, extracting a confession, interrogational torture, interrogation for information, or intimid ...

by the Inquisition for eliciting confessions from heretics. By 1256, inquisitors were given absolution

Absolution is a theological term for the forgiveness imparted by ordained Priest#Christianity, Christian priests and experienced by Penance#Christianity, Christian penitents. It is a universal feature of the historic churches of Christendom, alth ...

if they used instruments of torture. "The overwhelming majority of sentences seem to have consisted of penances like wearing a cross sewn on one's clothes, going on pilgrimage, etc." When a suspect was convicted of unrepentant heresy, the inquisitorial tribunal was required by law to hand the person over to the secular authorities for final sentencing, at which point a magistrate would determine the penalty, which was usually burning at the stake although the penalty varied based on local law. The laws were inclusive of proscriptions against certain religious crimes (heresy, etc.), and the punishments included death by burning

Death by burning is an execution, murder, or suicide method involving combustion or exposure to extreme heat. It has a long history as a form of public capital punishment, and many societies have employed it as a punishment for and warning agai ...

, although imprisonment for life or banishment would usually be used. Thus the inquisitors generally knew what would be the fate of anyone so remanded, and cannot be considered to have divorced the means of determining guilt from its effects.

Except for the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; ; ), officially the State of the Church, were a conglomeration of territories on the Italian peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope from 756 to 1870. They were among the major states of Italy from the 8th c ...

, the institution of the Inquisition was abolished in Europe in the early 19th century, after the Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

and in the Americas, it was abolished after the Spanish American wars of independence

The Spanish American wars of independence () took place across the Spanish Empire during the early 19th century. The struggles in both hemispheres began shortly after the outbreak of the Peninsular War, forming part of the broader context of the ...

. The institution survived as a part of the Roman Curia

The Roman Curia () comprises the administrative institutions of the Holy See and the central body through which the affairs of the Catholic Church are conducted. The Roman Curia is the institution of which the Roman Pontiff ordinarily makes use ...

, but in 1904, it was renamed the "Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Holy Office". In 1965, it was renamed the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith

The Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith (DDF) is a department of the Roman Curia in charge of the religious discipline of the Catholic Church. The Dicastery is the oldest among the departments of the Roman Curia. Its seat is the Palace of t ...

.

Christian terrorism

Christian terrorism comprises terrorist acts that are committed by groups or individuals who useChristian

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a Monotheism, monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the wo ...

motivations or goals as a justification for their actions. As with other forms of religious terrorism

Religious terrorism (or, religious extremism) is a type of religious violence where terrorism is used as a strategy to achieve certain religious goals or which are influenced by religious beliefs and/or identity.

In the modern age, after the d ...

, Christian terrorists have relied on interpretations of the tenets of their faith

Faith is confidence or trust in a person, thing, or concept. In the context of religion, faith is " belief in God or in the doctrines or teachings of religion".

According to the Merriam-Webster's Dictionary, faith has multiple definitions, inc ...

—in this case, the Bible

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) originally writt ...

. Such groups have cited Old Testament

The Old Testament (OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew and occasionally Aramaic writings by the Isr ...

and New Testament

The New Testament (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus, as well as events relating to Christianity in the 1st century, first-century Christianit ...

scriptures

Religious texts, including scripture, are texts which various religions consider to be of central importance to their religious tradition. They often feature a compilation or discussion of beliefs, ritual practices, moral commandments and ...

as justifications for acts of violence and killings or they have sought to bring about the " end times" which are described in the New Testament.

These interpretations are typically different from the interpretations of established Christian denomination

A Christian denomination is a distinct Religion, religious body within Christianity that comprises all Church (congregation), church congregations of the same kind, identifiable by traits such as a name, particular history, organization, leadersh ...

s.

Forced conversions

After the Constantinian shift, Christianity became entangled in government. Whileanthropologists

An anthropologist is a scientist engaged in the practice of anthropology. Anthropologists study aspects of humans within past and present societies. Social anthropology, cultural anthropology and philosophical anthropology study the norms, values ...

have shown that throughout history the relationship between religion and politics has been complex, there is no doubt that religious institutions, including Christian ones, have been used coercively by governments, and that they have used coercion themselves.Firth, Raymond (1981Spiritual Aroma: Religion and Politics

''American Anthropologist'', New Series, Vol. 83, No. 3, pp. 582–601

Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; ; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430) was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Africa. His writings deeply influenced the development of Western philosop ...

advocated government force in his Epistle 185, ''A Treatise Concerning the Correction of the Donatists'', justifying coercion from scripture. He cites Jesus

Jesus (AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Chris ...

striking Paul

Paul may refer to:

People

* Paul (given name), a given name, including a list of people

* Paul (surname), a list of people

* Paul the Apostle, an apostle who wrote many of the books of the New Testament

* Ray Hildebrand, half of the singing duo ...

during Paul's vision on the road to Damascus

Damascus ( , ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in the Levant region by population, largest city of Syria. It is the oldest capital in the world and, according to some, the fourth Holiest sites in Islam, holiest city in Islam. Kno ...

. He also cites the parable of the great banquet in . Such short term pain for the sake of eternal salvation was an act of charity and love, in his view.

Examples of forced conversion to Christianity include: the Christian persecution of paganism under Theodosius I, the forced conversion and violent assimilation of pagan tribes in medieval Europe, the Inquisition, including its manifestations in Goa, Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

, Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

, and Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

, the forced conversion of indigenous children in North America and Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

Support of slavery

Early Christianity

Early Christianity, otherwise called the Early Church or Paleo-Christianity, describes the History of Christianity, historical era of the Christianity, Christian religion up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325. Spread of Christianity, Christian ...

variously opposed, accepted, or ignored slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

. The early Christian perspectives on slavery were formed in the contexts of Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, which states that Jesus in Christianity, Jesus is the Son of God (Christianity), Son of God and Resurrection of Jesus, rose from the dead after his Crucifixion of Jesus, crucifixion, whose ...

's roots in Judaism

Judaism () is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic, Monotheism, monotheistic, ethnic religion that comprises the collective spiritual, cultural, and legal traditions of the Jews, Jewish people. Religious Jews regard Judaism as their means of o ...

, and they were also shaped by the wider culture of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

. Both the Old and New Testament

The New Testament (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus, as well as events relating to Christianity in the 1st century, first-century Christianit ...

s recognize the existence of the institution of slavery.

The earliest surviving Christian teachings about slavery are from Paul the Apostle

Paul, also named Saul of Tarsus, commonly known as Paul the Apostle and Saint Paul, was a Apostles in the New Testament, Christian apostle ( AD) who spread the Ministry of Jesus, teachings of Jesus in the Christianity in the 1st century, first ...

. Paul did not renounce the institution of slavery, though perhaps this was not for personal reasons (similar to Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

). He taught that Christian slaves ought to serve their masters wholeheartedly. Nothing in the passage affirms slavery as a naturally valid or divinely mandated institution. Rather, Paul's discussion about the duties of Christian slaves and the responsibilities of Christian masters transforms the institution, even if it falls short of calling for slavery's outright abolition. In the ancient world the slave was a thing. Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

wrote that there could never be friendship between a master and a slave, for a master and a slave have nothing in common: "a slave is a living tool, just as a tool is an inanimate slave." Paul's words are entirely different. He calls the slave a "slave of Christ", one who wants to do "the will of God

The will of God or divine will is a concept found in the Hebrew Bible, the New Testament, and a number of other texts and worldviews, according to which God's Will (philosophy), will is the cause of everything that exists.

Thomas Aquinas

Accord ...

" and who will receive a "reward" for "whatever good he does". Likewise, the master is responsible to God

In monotheistic belief systems, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. In polytheistic belief systems, a god is "a spirit or being believed to have created, or for controlling some part of the un ...

for how he treats his slave, who is ultimately God's property rather than his own. This is another way of saying that the slave, no less than the master, has been made in God's image. As such, he possesses inestimable worth and great dignity. He is to be treated properly. In such a framework slavery, even though it was still slavery, could never be the same type of institution that was imposed on non-Christians. It was this transformation (which came from viewing all persons as being made in God's image) that ultimately destroyed slavery. Tradition describes Pope Pius I

Pius I (, Greek: Πίος) was the bishop of Rome from 140 to his death 154, according to the ''Annuario Pontificio''. His dates are listed as 142 or 146 to 157 or 161, respectively. He is considered to have opposed both the Valentinians and ...

(term c. 158–167) and Pope Callixtus I

Pope Callixtus I ( Greek: Κάλλιστος), also called Callistus I, was the bishop of Rome (according to Sextus Julius Africanus) from to his death or 223.Chapman, John (1908). "Pope Callistus I" in ''The Catholic Encyclopedia''. Vol. 3. ...

(term c. 217–222) as former slaves.

Nearly all Christian leaders before the late 15th century recognised the institution of slavery, within specific Biblical limitations, as being consistent with Christian theology

Christian theology is the theology – the systematic study of the divine and religion – of Christianity, Christian belief and practice. It concentrates primarily upon the texts of the Old Testament and of the New Testament, as well as on Ch ...

. In 1452, Pope Nicholas V

Pope Nicholas V (; ; 15 November 1397 – 24 March 1455), born Tommaso Parentucelli, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 6 March 1447 until his death in March 1455. Pope Eugene IV made him a Cardinal (Catholic Chu ...

instituted the hereditary slavery of captured Muslim

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

s and pagans, regarding all non-Christians as "enemies of Christ".

, the Curse of Ham, says: "Cursed be Canaan! The lowest of slaves will he be to his brothers. He also said, 'Blessed be the Lord, the God of Shem! May Canaan be the slave of Shem." This verse has been used to justify racialized slavery, since "Christians and even some Muslims eventually identified Ham's descendents as black Africans

Black is a racial classification of people, usually a political and skin color-based category for specific populations with a mid- to dark brown complexion. Not all people considered "black" have dark skin and often additional phenotypical c ...

". Anthony Pagden argued that "This reading of the Book of Genesis merged easily into a medieval iconographic tradition in which devils were always depicted as black. Later pseudo-scientific theories would be built around African skull shapes, dental structure, and body postures, in an attempt to find an unassailable argument—rooted in whatever the most persuasive contemporary idiom happened to be: law, theology, genealogy, or natural science—why one part of the human race should live in perpetual indebtedness to another."

Rodney Stark makes the argument in ''For the Glory of God: How Monotheism Led to Reformations, Science, Witch-Hunts, and the End of Slavery'', that Christianity helped to end slavery worldwide, as does Lamin Sanneh in ''Abolitionists Abroad''. These authors point out that Christians who believed that slavery was wrong on the basis of their religious convictions spearheaded abolitionism

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was France in 1315, but it was later used in its colonies. ...

, and many of the early campaigners for the abolition of slavery were driven by their Christian faith and they were also driven by a desire to realize their view that all people are equal under God.

Modern-day Christians

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the world. The words '' Christ'' and ''C ...

generally condemn slavery as wrong and contrary to God

In monotheistic belief systems, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. In polytheistic belief systems, a god is "a spirit or being believed to have created, or for controlling some part of the un ...

's will. Only peripheral groups such as the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to KKK or Klan, is an American Protestant-led Christian terrorism, Christian extremist, white supremacist, Right-wing terrorism, far-right hate group. It was founded in 1865 during Reconstruction era, ...

and other Christian hate group

A hate group is a social group that advocates and practices hatred, hostility, or violence towards members of a race, ethnicity, nation, religion, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, or any other designated sector of society.

Acc ...

s which operate on the racist fringes of the Christian Reconstructionist and Christian Identity

Christian Identity (also known as Identity Christianity) is an interpretation of Christianity which advocates the belief that only Celtic and Germanic peoples, such as the Anglo-Saxon, Nordic nations, or the Aryan race and kindred peoples, are ...

movements advocate the reinstitution of slavery. Full adherents of Christian Reconstructionism are few and they are marginalized among conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

Christians

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the world. The words '' Christ'' and ''C ...

.Martin, William. 1996. ''With God on Our Side: The Rise of the Religious Right in America''. New York: Broadway Books.Diamond, Sara, 1998. ''Not by Politics Alone: The Enduring Influence of the Christian Right'', New York: Guilford Press, p.213.Ortiz, Chris 2007"Gary North on D. James Kennedy"

, Chalcedon Blog, 6 September 2007. With these exceptions, all Christian faith groups now condemn slavery, and they see the practice of slavery as being incompatible with basic Christian principles.

Violence against Jews

A strain of hostility towards

A strain of hostility towards Judaism

Judaism () is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic, Monotheism, monotheistic, ethnic religion that comprises the collective spiritual, cultural, and legal traditions of the Jews, Jewish people. Religious Jews regard Judaism as their means of o ...

and the Jewish people

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, religion, and community are highly inte ...

developed among Christians

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the world. The words '' Christ'' and ''C ...

in the early years of Christianity, persisted over the ensuing centuries, was driven by numerous factors including theological differences, the Christian drive for converts, which is decreed by the Great Commission

In Christianity, the Great Commission is the instruction of the Resurrection appearances of Jesus, resurrected Jesus Christ to his disciple (Christianity), disciples to spread the gospel to all the nations of the world. The Great Commission i ...

, a misunderstanding of Jewish beliefs and practices, and the perception that Jews are hostile towards Christians.

Over the centuries, these attitudes were reinforced by Christian preaching, art

Art is a diverse range of cultural activity centered around ''works'' utilizing creative or imaginative talents, which are expected to evoke a worthwhile experience, generally through an expression of emotional power, conceptual ideas, tec ...

and popular teaching, all of which expressed contempt for Jews.

Modern antisemitism

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

has primarily been described as hatred against Jews as a race

Racial antisemitism is prejudice against Jews based on a belief or assertion that Jews constitute a distinct race that has inherent traits or characteristics that appear in some way abhorrent or inherently inferior or otherwise different from ...

, a form of racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one Race (human categorization), race or ethnicity over another. It may also me ...

, rather than hatred against Jews as a religious group, because its modern expression is rooted in 18th century racial theories, while anti-Judaism

Anti-Judaism denotes a spectrum of historical and contemporary ideologies that are fundamentally or partially rooted in opposition to Judaism. It encompasses the rejection or abrogation of the Mosaic covenant and advocates for the superse ...

is described as hostility towards the Jewish religion, a sentiment which is rooted in but more extreme than criticism of Judaism as a religion

Religion is a range of social system, social-cultural systems, including designated religious behaviour, behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, religious text, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics in religion, ethics, or ...

, but in Western Christianity

Western Christianity is one of two subdivisions of Christianity (Eastern Christianity being the other). Western Christianity is composed of the Latin Church and Protestantism, Western Protestantism, together with their offshoots such as the O ...

, anti-Judaism was transformed into antisemitism during the 12th century

The 12th century is the period from 1101 to 1200 in accordance with the Julian calendar.

In the history of European culture, this period is considered part of the High Middle Ages and overlaps with what is often called the Golden Age' of the ...

.

Christian opposition to violence

Historian Roland Bainton described theearly church

Early Christianity, otherwise called the Early Church or Paleo-Christianity, describes the historical era of the Christian religion up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325. Christianity spread from the Levant, across the Roman Empire, and bey ...

as pacifist

Pacifism is the opposition to war or violence. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaigner Émile Arnaud and adopted by other peace activists at the tenth Universal Peace Congress in Glasgow in 1901. A related term is ''a ...

—a period that ended with the accession of Constantine.

In the first few centuries of Christianity, many Christians refused to engage in military service. In fact, there were a number of famous examples of soldiers who became Christians and refused to engage in combat afterwards. They were subsequently executed for their refusal to fight. The commitment to pacifism and the rejection of military service are attributed by Mark J. Allman, professor in the Department of Religious and Theological Studies at Merrimack College

Merrimack College is a Private university, private Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian university in North Andover, Massachusetts. It was founded in 1947 by the Order of St. Augustine with an initial goal to educate World War II veterans. It en ...

, to two principles: "(1) the use of force (violence) was seen as antithetical to Jesus' teachings and service in the Roman military required worship of the emperor as a god which was a form of idolatry."

In the 3rd century, Origen

Origen of Alexandria (), also known as Origen Adamantius, was an Early Christianity, early Christian scholar, Asceticism#Christianity, ascetic, and Christian theology, theologian who was born and spent the first half of his career in Early cent ...

wrote: "Christians could not slay their enemies." Clement of Alexandria

Titus Flavius Clemens, also known as Clement of Alexandria (; – ), was a Christian theology, Christian theologian and philosopher who taught at the Catechetical School of Alexandria. Among his pupils were Origen and Alexander of Jerusalem. A ...

wrote: "Above all, Christians are not allowed to correct with violence the delinquencies of sins." Tertullian

Tertullian (; ; 155 – 220 AD) was a prolific Early Christianity, early Christian author from Roman Carthage, Carthage in the Africa (Roman province), Roman province of Africa. He was the first Christian author to produce an extensive co ...

argued forcefully against all forms of violence, considering abortion

Abortion is the early termination of a pregnancy by removal or expulsion of an embryo or fetus. Abortions that occur without intervention are known as miscarriages or "spontaneous abortions", and occur in roughly 30–40% of all pregnan ...

, war

War is an armed conflict between the armed forces of states, or between governmental forces and armed groups that are organized under a certain command structure and have the capacity to sustain military operations, or between such organi ...

fare and even judicial death penalties to be forms of murder

Murder is the unlawful killing of another human without justification (jurisprudence), justification or valid excuse (legal), excuse committed with the necessary Intention (criminal law), intention as defined by the law in a specific jurisd ...

.

Pacifist and violence-resisting traditions have continued into contemporary times. One of those religious organizations are Jehovah's Witnesses, they are politically neutral and were one of the only religious groups as a whole to object to enlisting in WW2.

Several present-day Christian churches and communities were established specifically with nonviolence, including conscientious objection

A conscientious objector is an "individual who has claimed the right to refuse to perform military service" on the grounds of freedom of conscience or religion. The term has also been extended to objecting to working for the military–indu ...

to military service, as foundations of their beliefs. Members of the Historic Peace Churches such as Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestantism, Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally ...

, Mennonites

Mennonites are a group of Anabaptism, Anabaptist Christianity, Christian communities tracing their roots to the epoch of the Radical Reformation. The name ''Mennonites'' is derived from the cleric Menno Simons (1496–1561) of Friesland, part of ...

, Amish

The Amish (, also or ; ; ), formally the Old Order Amish, are a group of traditionalist Anabaptism, Anabaptist Christianity, Christian Christian denomination, church fellowships with Swiss people, Swiss and Alsace, Alsatian origins. As they ...

and the Church of the Brethren

The Church of the Brethren is an Anabaptist Christian denomination in the Schwarzenau Brethren tradition ( "Schwarzenau New Baptists") that was organized in 1708 by Alexander Mack in Schwarzenau, Germany during the Radical Pietist revival. ...

object to war based on their conviction that Christian life is incompatible with military actions, because Jesus

Jesus (AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Chris ...

enjoins his followers to love their enemies and refrain from committing acts of violence.

In the 20th century, Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister, civil and political rights, civil rights activist and political philosopher who was a leader of the civil rights move ...

and others adapted the nonviolent ideas of Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2October 186930January 1948) was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful campaign for India's independence from British ...

to a Baptist

Baptists are a Christian denomination, denomination within Protestant Christianity distinguished by baptizing only professing Christian believers (believer's baptism) and doing so by complete Immersion baptism, immersion. Baptist churches ge ...

theology and politics.

In the 21st century, Christian feminist thinkers have drawn attention to their views by opposing violence against women

Violence against women (VAW), also known as gender-based violence (GBV) or sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV), violent, violence primarily committed by Man, men or boys against woman, women or girls. Such violence is often considered hat ...

.

See also

*Buddhism and violence

Buddhism and violence looks at the historical and current examples of Violence, violent acts committed by Buddhists or groups connected to Buddhism, as well as the larger discussion of such behaviour within Buddhist traditions. Although Buddhism ...

* Christian fascism

*Christian fundamentalism

Christian fundamentalism, also known as fundamental Christianity or fundamentalist Christianity, is a religious movement emphasizing biblical literalism. In its modern form, it began in the late 19th and early 20th centuries among British an ...

*Christian Identity

Christian Identity (also known as Identity Christianity) is an interpretation of Christianity which advocates the belief that only Celtic and Germanic peoples, such as the Anglo-Saxon, Nordic nations, or the Aryan race and kindred peoples, are ...

*Christian nationalism

Christian nationalism is a form of religious nationalism that focuses on promoting the Christian views of its followers, in order to achieve prominence or Dominion theology, dominance in political, cultural, and social life. In countries with a ...

* Christian Nationalist Crusade

* Christian Party (United States, 1930s)

* Christianity and capital punishment

* Christians in the military

* Clerical fascism

* Criticism of Christianity

*God's Army (revolutionary group)

God's Army () was a Christian armed revolutionary group that opposed the then-ruling military junta of Myanmar (Burma). The group was an offshoot of the Karen National Union. They were based along the Thailand-Burma border, and conducted a st ...

* History of Christian thought on persecution and tolerance

* History of Christianity

The history of Christianity began with the life of Jesus, an itinerant Jewish preacher and teacher, who was Crucifixion of Jesus, crucified in Jerusalem . His followers proclaimed that he was the Incarnation (Christianity), incarnation of Go ...

*Hindu terrorism

Hindu terrorism, or sometimes Hindutva terror, or metonymically saffron terror, refer to terrorist acts carried out, on the basis of motivations in broad association with Hindu nationalism or Hindutva.

The phenomenon became a topic of conte ...

*Hindutva

Hindutva (; ) is a Far-right politics, far-right political ideology encompassing the cultural justification of Hindu nationalism and the belief in establishing Hindu hegemony within India. The political ideology was formulated by Vinayak Da ...

*Hindu nationalism

Hindu nationalism has been collectively referred to as the expression of political thought, based on the native social and cultural traditions of the Indian subcontinent. "Hindu nationalism" is a simplistic translation of . It is better descri ...

*Inquisition

The Inquisition was a Catholic Inquisitorial system#History, judicial procedure where the Ecclesiastical court, ecclesiastical judges could initiate, investigate and try cases in their jurisdiction. Popularly it became the name for various med ...

*Iron Guard

The Iron Guard () was a Romanian militant revolutionary nationalism, revolutionary Clerical fascism, religious fascist Political movement, movement and political party founded in 1927 by Corneliu Zelea Codreanu as the Legion of the Archangel M ...

*Islam and violence

The use of Political violence, politically and Religious violence, religiously-motivated violence in Islam dates back to History of Islam, its early history. Islam has its origins in the behavior, sayings, and rulings of the Muhammad in Islam, I ...

*Islamic fundamentalism

Islamic fundamentalism has been defined as a revivalist and reform movement of Muslims who aim to return to the founding scriptures of Islam. The term has been used interchangeably with similar terms such as Islamism, Islamic revivalism, Qut ...

*Islamism

Islamism is a range of religious and political ideological movements that believe that Islam should influence political systems. Its proponents believe Islam is innately political, and that Islam as a political system is superior to communism ...

* Judaism and violence

*Lord's Resistance Army