Christianity And Science on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Most scientific and technical innovations prior to the

Most sources of knowledge available to the

Most sources of knowledge available to the

H. Floris Cohen argued for a biblical Protestant, but not excluding Catholicism, influence on the early development of modern science.The Scientific Revolution: A Historiographical Inquiry

H. Floris Cohen argued for a biblical Protestant, but not excluding Catholicism, influence on the early development of modern science.The Scientific Revolution: A Historiographical Inquiry

H. Floris Cohen, University of Chicago Press 1994, 680 pages, , pages 308–321 He presented Dutch historian R. Hooykaas' argument that a biblical world-view holds all the necessary antidotes for the hubris of Greek rationalism: a respect for manual labour, leading to more experimentation and

While refined and clarified over the centuries, the

While refined and clarified over the centuries, the

Scientific Revolution

The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the emergence of History of science, modern science during the early modern period, when developments in History of mathematics#Mathematics during the Scientific Revolution, mathemati ...

were achieved by societies organized by religious traditions. Ancient Christian

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a Monotheism, monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the wo ...

scholars pioneered individual elements of the scientific method

The scientific method is an Empirical evidence, empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has been referred to while doing science since at least the 17th century. Historically, it was developed through the centuries from the ancient and ...

. Historically, Christianity has been and still is a patron of sciences. It has been prolific in the foundation of schools, universities

A university () is an educational institution, institution of tertiary education and research which awards academic degrees in several Discipline (academia), academic disciplines. ''University'' is derived from the Latin phrase , which roughly ...

and hospitals, and many Christian clergy have been active in the sciences and have made significant contributions to the development of science.

Historians of science

The history of science covers the development of science from ancient times to the present. It encompasses all three major branches of science: natural, social, and formal. Protoscience, early sciences, and natural philosophies such as al ...

such as Pierre Duhem

Pierre Maurice Marie Duhem (; 9 June 1861 – 14 September 1916) was a French theoretical physicist who made significant contributions to thermodynamics, hydrodynamics, and the theory of Elasticity (physics), elasticity. Duhem was also a prolif ...

credit medieval Catholic mathematicians and philosophers such as John Buridan

Jean Buridan (; ; Latin: ''Johannes Buridanus''; – ) was an influential 14thcentury French scholastic philosopher.

Buridan taught in the faculty of arts at the University of Paris for his entire career and focused in particular on logic and ...

, Nicole Oresme

Nicole Oresme (; ; 1 January 1325 – 11 July 1382), also known as Nicolas Oresme, Nicholas Oresme, or Nicolas d'Oresme, was a French philosopher of the later Middle Ages. He wrote influential works on economics, mathematics, physics, astrology, ...

and Roger Bacon

Roger Bacon (; or ', also '' Rogerus''; ), also known by the Scholastic accolades, scholastic accolade ''Doctor Mirabilis'', was a medieval English polymath, philosopher, scientist, theologian and Franciscans, Franciscan friar who placed co ...

as the founders of modern science. Duhem concluded that "the mechanics and physics of which modern times are justifiably proud to proceed, by an uninterrupted series of scarcely perceptible improvements, from doctrines professed in the heart of the medieval schools". Many of the most distinguished classical scholars in the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

held high office in the Eastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, officially the Orthodox Catholic Church, and also called the Greek Orthodox Church or simply the Orthodox Church, is List of Christian denominations by number of members, one of the three major doctrinal and ...

. Protestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

has had an important influence on science, according to the Merton Thesis, there was a positive correlation between the rise of English Puritanism

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to rid the Church of England of what they considered to be Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should ...

and German Pietism

Pietism (), also known as Pietistic Lutheranism, is a movement within Lutheranism that combines its emphasis on biblical doctrine with an emphasis on individual piety and living a holy Christianity, Christian life.

Although the movement is ali ...

on the one hand, and early experimental science on the other.

Christian scholars and scientists have made noted contributions to science

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

and technology

Technology is the application of Conceptual model, conceptual knowledge to achieve practical goals, especially in a reproducible way. The word ''technology'' can also mean the products resulting from such efforts, including both tangible too ...

fields, as well as medicine

Medicine is the science and Praxis (process), practice of caring for patients, managing the Medical diagnosis, diagnosis, prognosis, Preventive medicine, prevention, therapy, treatment, Palliative care, palliation of their injury or disease, ...

, both historically and in modern times.Baruch A. Shalev, ''100 Years of Nobel Prizes'' (2003), Atlantic Publishers & Distributors, p.57: between 1901 and 2000 reveals that 654 Laureates belong to 28 different religions. Most (65.4%) have identified Christianity in its various forms as their religious preference. Some scholars state that Christianity contributed to the rise of the Scientific Revolution

The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the emergence of History of science, modern science during the early modern period, when developments in History of mathematics#Mathematics during the Scientific Revolution, mathemati ...

. Between 1901 and 2001, about 56.5% of Nobel prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; ; ) are awards administered by the Nobel Foundation and granted in accordance with the principle of "for the greatest benefit to humankind". The prizes were first awarded in 1901, marking the fifth anniversary of Alfred N ...

laureates in scientific fields were Christians

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the world. The words '' Christ'' and ''C ...

, and 26% were of Jewish descent (including Jewish atheists

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, religion, and community are highly inte ...

).

Events in Christian Europe

The terms Christendom or Christian world commonly refer to the global Christian community, Christian states, Christian-majority countries or countries in which Christianity is dominant or prevails.SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christen ...

, such as the Galileo affair

The Galileo affair was an early 17th century political, religious, and scientific controversy regarding the astronomer Galileo Galilei's defence of heliocentrism, the idea that the Earth revolves around the Sun. It pitted supporters and opponent ...

, that were associated with the Scientific Revolution

The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the emergence of History of science, modern science during the early modern period, when developments in History of mathematics#Mathematics during the Scientific Revolution, mathemati ...

and the Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a Europe, European Intellect, intellectual and Philosophy, philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained th ...

led some scholars such as John William Draper

John William Draper (May 5, 1811 – January 4, 1882) was an English polymath: a scientist, philosopher, physician, chemist, historian and photographer. He is credited with pioneering portrait photography (1839–40) and producing the first deta ...

to postulate a conflict thesis, holding that religion and science have been in conflict throughout history. While the conflict thesis remains popular in atheistic and antireligious circles, it has lost favor among most contemporary historians of science. Most contemporary historians of science believe the Galileo affair is an exception in the overall relationship between science and Christianity and have also corrected numerous false interpretations of this event.

Overview

Most sources of knowledge available to the

Most sources of knowledge available to the early Christians

Early Christianity, otherwise called the Early Church or Paleo-Christianity, describes the historical era of the Christian religion up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325. Christianity spread from the Levant, across the Roman Empire, and bey ...

were connected to pagan

Paganism (, later 'civilian') is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Christianity, Judaism, and Samaritanism. In the time of the ...

worldviews as the early Christians largely lived among pagans. There were various opinions on how Christianity should regard pagan learning, which included its ideas about nature. For instance, among early Christian teachers, from Tertullian

Tertullian (; ; 155 – 220 AD) was a prolific Early Christianity, early Christian author from Roman Carthage, Carthage in the Africa (Roman province), Roman province of Africa. He was the first Christian author to produce an extensive co ...

(c. 160–220) held a generally negative opinion of Greek philosophy

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC. Philosophy was used to make sense of the world using reason. It dealt with a wide variety of subjects, including astronomy, epistemology, mathematics, political philosophy, ethics, metaphysic ...

, while Origen

Origen of Alexandria (), also known as Origen Adamantius, was an Early Christianity, early Christian scholar, Asceticism#Christianity, ascetic, and Christian theology, theologian who was born and spent the first half of his career in Early cent ...

(c. 185–254) regarded it much more favourably and required his students to read nearly every work available to them.

Earlier attempts at reconciliation of Christianity with Newtonian mechanics

Newton's laws of motion are three physical laws that describe the relationship between the motion of an object and the forces acting on it. These laws, which provide the basis for Newtonian mechanics, can be paraphrased as follows:

# A body r ...

appear quite different from later attempts at reconciliation with the newer scientific ideas of evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

or relativity.''Religion and Science'', John Habgood

John Stapylton Habgood, Baron Habgood, (23 June 1927 – 6 March 2019) was a British Anglican bishop, academic, and life peer. He was Bishop of Durham from 1973 to 1983, and Archbishop of York from 18 November 1983 to 1995. In 1995, he was made ...

, Mills & Brown, 1964, pp., 11, 14–16, 48–55, 68–69, 90–91, 87 Many early interpretations of evolution polarized themselves around a ''struggle for existence

The concept of the struggle for existence (or struggle for life) concerns the competition or battle for resources needed to live. It can refer to human society, or to organisms in nature. The concept is ancient, and the term ''struggle for existe ...

.'' These ideas were significantly countered by later findings of universal patterns of biological cooperation. According to John Habgood

John Stapylton Habgood, Baron Habgood, (23 June 1927 – 6 March 2019) was a British Anglican bishop, academic, and life peer. He was Bishop of Durham from 1973 to 1983, and Archbishop of York from 18 November 1983 to 1995. In 1995, he was made ...

, all man really knows here is that the universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents. It comprises all of existence, any fundamental interaction, physical process and physical constant, and therefore all forms of matter and energy, and the structures they form, from s ...

seems to be a mix of good and evil

In philosophy, religion, and psychology, "good and evil" is a common dichotomy. In religions with Manichaeism, Manichaean and Abrahamic influence, evil is perceived as the dualistic cosmology, dualistic antagonistic opposite of good, in which ...

, beauty

Beauty is commonly described as a feature of objects that makes them pleasure, pleasurable to perceive. Such objects include landscapes, sunsets, humans and works of art. Beauty, art and taste are the main subjects of aesthetics, one of the fie ...

and pain

Pain is a distressing feeling often caused by intense or damaging Stimulus (physiology), stimuli. The International Association for the Study of Pain defines pain as "an unpleasant sense, sensory and emotional experience associated with, or res ...

, and that suffering

Suffering, or pain in a broad sense, may be an experience of unpleasantness or aversion, possibly associated with the perception of harm or threat of harm in an individual. Suffering is the basic element that makes up the negative valence (psyc ...

may somehow be part of the process of creation. Habgood holds that Christians should not be surprised that suffering may be used creatively by God

In monotheistic belief systems, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. In polytheistic belief systems, a god is "a spirit or being believed to have created, or for controlling some part of the un ...

, given their faith in the symbol of the Cross

A cross is a religious symbol consisting of two Intersection (set theory), intersecting Line (geometry), lines, usually perpendicular to each other. The lines usually run vertically and horizontally. A cross of oblique lines, in the shape of t ...

. Robert John Russell

Robert John Russell is founder and Director of the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences (CTNS). He is also the Ian G. Barbour Professor of Theology and Science in Residence at the Graduate Theological Union (GTU). He has written and edit ...

has examined consonance and dissonance between modern physics, evolutionary biology, and Christian theology.

Christian philosophers

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the world. The words ''Christ'' and ''Chr ...

Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; ; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430) was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Africa. His writings deeply influenced the development of Western philosop ...

(354–430) and Thomas Aquinas held that scriptures can have multiple interpretations on certain areas where the matters were far beyond their reach, therefore one should leave room for future findings to shed light on the meanings. Augustine argued:Usually, even a non-Christian knows something about the earth, the heavens, and the other elements of this world, about the motion and orbit of the stars ... Now, it is a disgraceful and dangerous thing for an infidel to hear a Christian, presumably giving the meaning of Holy Scripture, talking non-sense on these topics; and we should take all means to prevent such an embarrassing situation, in which people show up vast ignorance in a Christian and laugh it to scorn. The shame is not so much that an ignorant individual is derided, but that people outside the household of the faith think our sacred writers held such opinions, and, to the great loss of those for whose salvation we toil, the writers of our Scripture are criticized and rejected as unlearned men.The "Handmaiden" tradition, which saw secular studies of the universe as a very important and helpful part of arriving at a better understanding of scripture, was adopted throughout Christian history from early on. Also, the sense that God created the world as a self-operating system is what motivated many Christians throughout the Middle Ages to investigate nature. The

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

was one of the peaks in Christian history

The history of Christianity began with the life of Jesus, an itinerant Jewish preacher and teacher, who was crucified in Jerusalem . His followers proclaimed that he was the incarnation of God and had risen from the dead. In the two millen ...

and Christian civilization

Christianity has been intricately intertwined with the History of Western civilization, history and formation of Western society. Throughout history of Christianity, its long history, the Christian Church, Church has been a major source of so ...

, and Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

remained the leading city of the Christian world

The terms Christendom or Christian world commonly refer to the global Christian community, Christian states, Christian-majority countries or countries in which Christianity is dominant or prevails.SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christen ...

in size, wealth, and culture. There was a renewed interest in classical Greek philosophy, as well as an increase in literary output in vernacular Greek. The Byzantine science

Scientific scholarship during the Byzantine Empire played an important role in the transmission of classical knowledge to the Islamic world and to Renaissance Italy, and also in the transmission of Islamic science to Renaissance Italy. Its rich ...

played an important role in the transmission of classical knowledge to the Islamic world

The terms Islamic world and Muslim world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs, politics, and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is ...

and to Renaissance Italy

The Italian Renaissance ( ) was a period in History of Italy, Italian history between the 14th and 16th centuries. The period is known for the initial development of the broader Renaissance culture that spread across Western Europe and marked t ...

, and also in the transmission of Islamic science

Science in the medieval Islamic world was the science developed and practised during the Islamic Golden Age under the Abbasid Caliphate of Baghdad, the Umayyads of Córdoba, the Abbadids of Seville, the Samanids, the Ziyarids and the Buyi ...

to Renaissance Italy. Many of the most distinguished classical scholars held high office in the Eastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, officially the Orthodox Catholic Church, and also called the Greek Orthodox Church or simply the Orthodox Church, is List of Christian denominations by number of members, one of the three major doctrinal and ...

.The faculty was composed exclusively of philosophers, scientists, rhetoricians, and philologists

Philology () is the study of language in Oral tradition, oral and writing, written historical sources. It is the intersection of textual criticism, literary criticism, history, and linguistics with strong ties to etymology. Philology is also de ...

()

Modern historians of science such as J.L. Heilbron, Alistair Cameron Crombie

Alistair Cameron Crombie (4 November 1915 – 9 February 1996) was an Australian historian of science who began his career as a zoologist. He was noted for his contributions to research on competition between species before turning to history.

...

, David Lindberg, Edward Grant

Edward Grant (April 6, 1926 – June 21, 2020) was an American historian of medieval science. He was named a distinguished professor in 1983. Other honors include the 1992 George Sarton Medal, for "a lifetime scholarly achievement" as an histor ...

, Thomas Goldstein, and Ted Davis have reviewed the popular notion that medieval Christianity was a negative influence in the development of civilization and science. In their views, not only did the monks save and cultivate the remnants of ancient civilization during the barbarian invasions, but the medieval church promoted learnings and science through its sponsorship of many universities

A university () is an educational institution, institution of tertiary education and research which awards academic degrees in several Discipline (academia), academic disciplines. ''University'' is derived from the Latin phrase , which roughly ...

which, under its leadership, grew rapidly in Europe in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. St. Thomas Aquinas, the Church's "model theologian", not only argued that reason is in harmony with faith, he even recognized that reason can contribute to understanding revelation, and so encouraged intellectual development. He was not unlike other medieval theologians who sought out reason in the effort to defend his faith. Some of today's scholars, such as Stanley Jaki

Stanley L. Jaki (Jáki Szaniszló László) (17 August 1924 – 7 April 2009) was a Hungarian-born priest of the Benedictine order. From 1975 to his death, he was Distinguished University Professor at Seton Hall University, in South Orange, Ne ...

, have claimed that Christianity with its particular worldview

A worldview (also world-view) or is said to be the fundamental cognitive orientation of an individual or society encompassing the whole of the individual's or society's knowledge, culture, and Perspective (cognitive), point of view. However, whe ...

, was a crucial factor for the emergence of modern science. According to professor Noah J. Efron, virtually all modern scholars and historians agree that Christianity moved many early-modern intellectuals to study nature systematically.

Physics teacher David Hutchings and intellectual historian James C. Ungureanu credit the central tenets of traditional Christianity for having been the greatest benefit to scientific thinking, while at the same time noting the irony of the conflict thesis:David C. Lindberg states that the widespread popular belief that the Middle Ages was a time of ignorance and superstition due to the Christian church is a "caricature". According to Lindberg, while there are some portions of the classical tradition which suggest this view, these were exceptional cases. It was common to tolerate and encourage critical thinking about the nature of the world. The relation between Christianity and science is complex and cannot be simplified to either harmony or conflict, according to Lindberg. Lindberg reports that "the late medieval scholar rarely experienced the coercive power of the church and would have regarded himself as free (particularly in the natural sciences) to follow reason and observation wherever they led. There was no warfare between science and the church." Ted Peters in ''Encyclopedia of Religion'' writes that although there is some truth in the "Galileo's condemnation" story but through exaggerations, it has now become "a modern myth perpetuated by those wishing to see warfare between science and religion who were allegedly persecuted by an atavistic and dogma-bound ecclesiastical authority". In 1992, the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

's seeming vindication of Galileo attracted much comment in the media

Media may refer to:

Communication

* Means of communication, tools and channels used to deliver information or data

** Advertising media, various media, content, buying and placement for advertising

** Interactive media, media that is inter ...

:

A degree of concord between science and religion can be seen in religious belief and empirical science. The belief that God created the world and therefore humans, can lead to the view that he arranged for humans to know the world. This is underwritten by the doctrine of imago dei. In the words of Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas ( ; ; – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest, the foremost Scholasticism, Scholastic thinker, as well as one of the most influential philosophers and theologians in the W ...

, "Since human beings are said to be in the image of God in virtue of their having a nature that includes an intellect, such a nature is most in the image of God in virtue of being most able to imitate God".

During the Enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

, a period "characterized by dramatic revolutions in science" and the rise of Protestant challenges to the authority of the Catholic Church via individual liberty, the authority of Christian scriptures became strongly challenged. As science advanced, acceptance of a literal version of the Bible became "increasingly untenable" and some in that period presented ways of interpreting scripture according to its spirit on its authority and truth.

Regarding the subject on the distribution of Nobel Prizes by religion between 1901 and 2000, the data taken from Baruch A. Shalev, shows that between the years 1901 and 2000 reveals that 654 Laureates belong to 28 different religion. 65.4% have identified Christianity in its various forms as their religious preference. Overall, Christians have won a total of 78.3% of all the Nobel Prizes in Peace, 72.5% in Chemistry, 65.3% in Physics, 62% in Medicine, 54% in Economics and 49.5% of all Literature awards.

History

Roots of the Scientific Revolution

Between 1150 and 1200, Christian scholars had traveled to Sicily and Spain to retrieve the writings of Aristotle, which had been lost to the West after the Fall of the Roman Empire. This produced a period of cultural ferment that one "modern historian has called the twelfth century renaissance".Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas ( ; ; – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest, the foremost Scholasticism, Scholastic thinker, as well as one of the most influential philosophers and theologians in the W ...

responded by writing his monumental summas in support of human reason as compatible with faith. Christian theology adapted to Aristotle's secular and humanistic natural philosophy. By the Late Middle Ages, Aquinas's rationalism was being heatedly debated in the new universities. William Ockham

William of Ockham or Occam ( ; ; 9/10 April 1347) was an English Franciscan friar, scholastic philosopher, apologist, and theologian, who was born in Ockham, a small village in Surrey. He is considered to be one of the major figures of mediev ...

resolved the conflict by arguing that faith and reason should be pursued separately so that each could achieve its own end. Historians of science David C. Lindberg, Ronald Numbers and Edward Grant have described what followed as a "medieval scientific revival". Science historian Noah Efron has written that Christianity provided the early "tenets, methods, and institutions of what in time became modern science".

Modern western universities have their origins directly in the Medieval Church. They began as cathedral school

Cathedral schools began in the Early Middle Ages as centers of advanced education, some of them ultimately evolving into medieval universities. Throughout the Middle Ages and beyond, they were complemented by the monastic schools. Some of these ...

s, and all students were considered clerics. This was a benefit as it placed the students under ecclesiastical jurisdiction and thus imparted certain legal immunities and protections. The cathedral schools eventually became partially detached from the cathedrals and formed their own institutions, the earliest being the University of Bologna

The University of Bologna (, abbreviated Unibo) is a Public university, public research university in Bologna, Italy. Teaching began around 1088, with the university becoming organised as guilds of students () by the late 12th century. It is the ...

(1088), the University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate university, collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the List of oldest un ...

(1096), and the University of Paris

The University of Paris (), known Metonymy, metonymically as the Sorbonne (), was the leading university in Paris, France, from 1150 to 1970, except for 1793–1806 during the French Revolution. Emerging around 1150 as a corporation associated wit ...

(''c''. 1150).Rüegg, Walter: "Foreword. The University as a European Institution", in: ''A History of the University in Europe. Vol. 1: Universities in the Middle Ages'', Cambridge University Press, 1992, , pp. XIX–XX

Some scholars have noted a direct tie between "particular aspects of traditional Christianity" and the rise of science. Other scholars and historians have credited Christianity with laying the foundation for the Scientific Revolution

The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the emergence of History of science, modern science during the early modern period, when developments in History of mathematics#Mathematics during the Scientific Revolution, mathemati ...

. According to Robert K. Merton, the values of English Puritanism and German Pietism led to the Scientific Revolution

The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the emergence of History of science, modern science during the early modern period, when developments in History of mathematics#Mathematics during the Scientific Revolution, mathemati ...

of the 17th and 18th centuries. (The Merton Thesis is both widely accepted and disputed.) Merton explained that the connection between religious affiliation

Religious identity is a specific type of identity formation. Particularly, it is the sense of group membership to a religion and the importance of this group membership as it pertains to one's self-concept. Religious identity is not necessarily the ...

and interest in science was the result of a significant synergy between the ascetic

Asceticism is a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from worldly pleasures through self-discipline, self-imposed poverty, and simple living, often for the purpose of pursuing spiritual goals. Ascetics may withdraw from the world for their pra ...

Protestant values and those of modern science.

Influence of biblical worldviews on early modern science

At first, according toAndrew Dickson White

Andrew Dickson White (November 7, 1832 – November 4, 1918) was an American historian and educator who co-founded Cornell University, one of eight Ivy League universities in the United States, and served as its first president for nearly two de ...

's 1896 book '' A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom'', a biblical worldview affected negatively the progress of science through time. Dickinson also argues that immediately following the Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

matters were even worse. The interpretations of Scripture by Luther and Calvin became as sacred to their followers as the Scripture itself. For instance, when Georg Calixtus ventured, in interpreting the Psalms, to question the accepted belief that "the waters above the heavens" were contained in a vast receptacle upheld by a solid vault, he was bitterly denounced as heretical. Today, much of the scholarship in which the conflict thesis was originally based is considered to be inaccurate. For instance, the claim that early Christians rejected scientific findings by the Greco-Romans is false, since the "handmaiden" view of secular studies was seen to shed light on theology. This view was widely adapted throughout the early medieval period and afterwards by theologians (such as Augustine) and ultimately resulted in fostering interest in knowledge about nature through time. Also, the claim that people of the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

widely believed that the Earth was flat was first propagated in the same period that originated the conflict thesisJeffrey Russell. ''Inventing the Flat Earth: Columbus and Modern Historians''. Praeger Paperback; New Ed edition (30 January 1997). ; . and is still very common in popular culture. Modern scholars regard this claim as mistaken, as the contemporary historians of science David C. Lindberg and Ronald L. Numbers write: "there was scarcely a Christian scholar of the Middle Ages who did not acknowledge arth'ssphericity and even know its approximate circumference." From the fall of Rome to the time of Columbus, all major scholars and many vernacular writers interested in the physical shape of the Earth held a spherical view with the exception of Lactantius and Cosmas.

H. Floris Cohen argued for a biblical Protestant, but not excluding Catholicism, influence on the early development of modern science.The Scientific Revolution: A Historiographical Inquiry

H. Floris Cohen argued for a biblical Protestant, but not excluding Catholicism, influence on the early development of modern science.The Scientific Revolution: A Historiographical InquiryH. Floris Cohen, University of Chicago Press 1994, 680 pages, , pages 308–321 He presented Dutch historian R. Hooykaas' argument that a biblical world-view holds all the necessary antidotes for the hubris of Greek rationalism: a respect for manual labour, leading to more experimentation and

empiricism

In philosophy, empiricism is an epistemological view which holds that true knowledge or justification comes only or primarily from sensory experience and empirical evidence. It is one of several competing views within epistemology, along ...

, and a supreme God that left nature and open to emulation and manipulation. It supports the idea early modern science rose due to a combination of Greek and biblical thought.

Oxford historian Peter Harrison is another who has argued that a Biblical worldview was significant for the development of modern science. Harrison contends that Protestant approaches to the book of scripture had significant, if largely unintended, consequences for the interpretation of the book of nature. Harrison has also suggested that literal readings of the Genesis narratives of the Creation and Fall motivated and legitimated scientific activity in seventeenth-century England. For many of its seventeenth-century practitioners, science was imagined to be a means of restoring a human dominion over nature that had been lost as a consequence of the Fall.

Historian and professor of religion Eugene M. Klaaren holds that "a belief in divine creation" was central to an emergence of science in seventeenth-century England. The philosopher Michael Foster has published analytical philosophy connecting Christian doctrines of creation with empiricism. Historian William B. Ashworth has argued against the historical notion of distinctive mind-sets and the idea of Catholic and Protestant sciences. Historians James R. Jacob and Margaret C. Jacob have argued for a linkage between seventeenth-century Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

intellectual transformations and influential English scientists (e.g., Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle (; 25 January 1627 – 31 December 1691) was an Anglo-Irish natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, Alchemy, alchemist and inventor. Boyle is largely regarded today as the first modern chemist, and therefore one of the foun ...

and Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton () was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment that followed ...

). John Dillenberger

John Dillenberger (1918–2008) was professor of historical theology at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley, California. He was instrumental in forming the Graduate Theological Union which he headed during its first decade, first as dean f ...

and Christopher B. Kaiser have written theological surveys, which also cover additional interactions occurring in the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries. Philosopher of Religion, Richard Jones, has written a philosophical critique of the "dependency thesis" which assumes that modern science emerged from Christian sources and doctrines. Though he acknowledges that modern science emerged in a religious framework, that Christianity greatly elevated the importance of science by sanctioning and religiously legitimizing it in medieval period, and that Christianity created a favorable social context for it to grow; he argues that direct Christian beliefs or doctrines were not primary source of scientific pursuits by natural philosophers, nor was Christianity, in and of itself, exclusively or directly necessary in developing or practicing modern science.

Oxford University

The University of Oxford is a collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the second-oldest continuously operating u ...

historian and theologian John Hedley Brooke

John Hedley Brooke (born 20 May 1944) is a British historian of science specialising in the relationship between science and religion.

Biography

Born on 20 May 1944, Brooke is the son of Hedley Joseph Brooke, and Margaret Brooke, née Brown. ...

wrote that "when natural philosophers referred to ''laws'' of nature, they were not glibly choosing that metaphor. Laws were the result of legislation by an intelligent deity. Thus, the philosopher René Descartes

René Descartes ( , ; ; 31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650) was a French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician, widely considered a seminal figure in the emergence of modern philosophy and Modern science, science. Mathematics was paramou ...

(1596–1650) insisted that he was discovering the "laws that God has put into nature." Later Newton would declare that the regulation of the Solar System

The Solar SystemCapitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Sola ...

presupposed the "counsel and dominion of an intelligent and powerful Being." Historian Ronald L. Numbers stated that this thesis "received a boost" from mathematician and philosopher Alfred North Whitehead

Alfred North Whitehead (15 February 1861 – 30 December 1947) was an English mathematician and philosopher. He created the philosophical school known as process philosophy, which has been applied in a wide variety of disciplines, inclu ...

's ''Science and the Modern World'' (1925). Numbers has also argued, "Despite the manifest shortcomings of the claim that Christianity gave birth to science—most glaringly, it ignores or minimizes the contributions of ancient Greeks and medieval Muslims—it too, refuses to succumb to the death it deserves." The sociologist Rodney Stark

Rodney William Stark (July 8, 1934 – July 21, 2022) was an American sociologist of religion who was a longtime professor of sociology and of comparative religion at the University of Washington. At the time of his death he was the Distinguished ...

of Baylor University

Baylor University is a Private university, private Baptist research university in Waco, Texas, United States. It was chartered in 1845 by the last Congress of the Republic of Texas. Baylor is the oldest continuously operating university in Te ...

, argued in contrast that "Christian theology was essential for the rise of science."

Reconciliation in Britain in the early 20th century

In ''Reconciling Science and Religion: The Debate in Early-twentieth-century Britain'', historian of biology Peter J. Bowler argues that in contrast to the conflicts between science and religion in the U.S. in the 1920s (most famously the Scopes Trial), during this period Great Britain experienced a concerted effort at reconciliation, championed by intellectually conservative scientists, supported by liberal theologians but opposed by younger scientists and secularists and conservative Christians. These attempts at reconciliation fell apart in the 1930s due to increased social tensions, moves towardsneo-orthodox

In Christianity, Neo-orthodoxy or Neoorthodoxy, also known as crisis theology and dialectical theology, was a theological movement developed in the aftermath of the First World War. The movement was largely a reaction against doctrines of 19th ...

theology and the acceptance of the modern evolutionary synthesis.

In the twentieth century, several ecumenical

Ecumenism ( ; alternatively spelled oecumenism)also called interdenominationalism, or ecumenicalismis the concept and principle that Christians who belong to different Christian denominations should work together to develop closer relationships ...

organizations promoting a harmony between science and Christianity were founded, most notably the American Scientific Affiliation

The American Scientific Affiliation (ASA) is a Christian religious organization of scientists and people in science-related disciplines. The stated purpose is "to investigate any area relating Christian faith and science." The organization publi ...

, The Biologos Foundation, Christians in Science, The Society of Ordained Scientists, and The Veritas Forum.

Branches of Christianity

Catholicism

While refined and clarified over the centuries, the

While refined and clarified over the centuries, the Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

position on the relationship between science and religion is one of harmony and has maintained the teaching of natural law

Natural law (, ) is a Philosophy, philosophical and legal theory that posits the existence of a set of inherent laws derived from nature and universal moral principles, which are discoverable through reason. In ethics, natural law theory asserts ...

as set forth by Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas ( ; ; – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest, the foremost Scholasticism, Scholastic thinker, as well as one of the most influential philosophers and theologians in the W ...

. For example, regarding scientific study such as that of evolution, the church's unofficial position is an example of theistic evolution

Theistic evolution (also known as theistic evolutionism or God-guided evolution), alternatively called evolutionary creationism, is a view that God acts and creates through laws of nature. Here, God is taken as the primary cause while natural cau ...

, stating that faith and scientific findings regarding human evolution are not in conflict, though humans are regarded as a special creation, and that the existence of God is required to explain both monogenism

Monogenism or sometimes monogenesis is the theory of human origins which posits a common descent for all humans. The negation of monogenism is polygenism. This issue was hotly debated in the Western world in the nineteenth century, as the assum ...

and the spiritual component of human origins. Catholic schools have included all manners of scientific study in their curriculum for many centuries. Historian John Heilbron says that "The Roman Catholic Church gave more financial and social support to the study of astronomy for over six centuries, from the recovery of ancient learning during the late Middle Ages into the Enlightenment, then any other, and probably all, other Institutions."

The first universities in Europe were established by Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

monks. The first Western European institutions generally considered to be universities

A university () is an educational institution, institution of tertiary education and research which awards academic degrees in several Discipline (academia), academic disciplines. ''University'' is derived from the Latin phrase , which roughly ...

were established in present-day Italy (including the Kingdom of Sicily

The Kingdom of Sicily (; ; ) was a state that existed in Sicily and the southern Italian peninsula, Italian Peninsula as well as, for a time, in Kingdom of Africa, Northern Africa, from its founding by Roger II of Sicily in 1130 until 1816. It was ...

, the Kingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples (; ; ), officially the Kingdom of Sicily, was a state that ruled the part of the Italian Peninsula south of the Papal States between 1282 and 1816. It was established by the War of the Sicilian Vespers (1282–1302). Until ...

, and the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy (, ) was a unitary state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 10 June 1946, when the monarchy wa ...

), the Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from the late 9th century, when it was unified from various Heptarchy, Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland to f ...

, the Kingdom of France

The Kingdom of France is the historiographical name or umbrella term given to various political entities of France in the Middle Ages, medieval and Early modern France, early modern period. It was one of the most powerful states in Europe from th ...

, Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

, the Kingdom of Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

, the Kingdom of Portugal

The Kingdom of Portugal was a Portuguese monarchy, monarchy in the western Iberian Peninsula and the predecessor of the modern Portuguese Republic. Existing to various extents between 1139 and 1910, it was also known as the Kingdom of Portugal a ...

and the Kingdom of Scotland

The Kingdom of Scotland was a sovereign state in northwest Europe, traditionally said to have been founded in 843. Its territories expanded and shrank, but it came to occupy the northern third of the island of Great Britain, sharing a Anglo-Sc ...

between the 11th and 15th centuries for the study of the arts

The arts or creative arts are a vast range of human practices involving creativity, creative expression, storytelling, and cultural participation. The arts encompass diverse and plural modes of thought, deeds, and existence in an extensive ...

and the higher disciplines of theology

Theology is the study of religious belief from a Religion, religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an Discipline (academia), academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itse ...

, law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior, with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been variously described as a science and as the ar ...

, and medicine

Medicine is the science and Praxis (process), practice of caring for patients, managing the Medical diagnosis, diagnosis, prognosis, Preventive medicine, prevention, therapy, treatment, Palliative care, palliation of their injury or disease, ...

.de Ridder-Symoens (1992), pp. 47–55 These universities evolved from much older Christian

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a Monotheism, monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the wo ...

cathedral school

Cathedral schools began in the Early Middle Ages as centers of advanced education, some of them ultimately evolving into medieval universities. Throughout the Middle Ages and beyond, they were complemented by the monastic schools. Some of these ...

s and monastic school

Monastic schools () were, along with cathedral schools, the most important institutions of higher learning in the Latin West#Use with regard to Christianity, Latin West from the early Middle Ages until the 12th century. Since Cassiodorus's educatio ...

s, and it is difficult to define the exact date when they became true universities, though the lists of studia generalia for higher education in Europe held by the Vatican

Vatican may refer to:

Geography

* Vatican City, an independent city-state surrounded by Rome, Italy

* Vatican Hill, in Rome, namesake of Vatican City

* Ager Vaticanus, an alluvial plain in Rome

* Vatican, an unincorporated community in the ...

are a useful guide:

Galileo once stated "The intention of the Holy Spirit

The Holy Spirit, otherwise known as the Holy Ghost, is a concept within the Abrahamic religions. In Judaism, the Holy Spirit is understood as the divine quality or force of God manifesting in the world, particularly in acts of prophecy, creati ...

is to teach us how to go to heaven, not how the heavens go." In 1981, John Paul II

Pope John Paul II (born Karol Józef Wojtyła; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 16 October 1978 until Death and funeral of Pope John Paul II, his death in 2005.

In his you ...

, then pope

The pope is the bishop of Rome and the Head of the Church#Catholic Church, visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. He is also known as the supreme pontiff, Roman pontiff, or sovereign pontiff. From the 8th century until 1870, the po ...

of the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

, spoke of the relationship this way: "The Bible itself speaks to us of the origin of the universe and its make-up, not in order to provide us with a scientific treatise, but in order to state the correct relationships of Man with God and with the universe. Sacred Scripture wishes simply to declare that the world was created by God, and in order to teach this truth it expresses itself in the terms of the cosmology in use at the time of the writer". The influence of the Church on Western letters and learning has been formidable. The ancient texts of the Bible have deeply influenced Western art, literature and culture. For centuries following the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, small monastic communities were practically the only outposts of literacy in Western Europe. In time, the cathedral schools developed into Europe's earliest universities and the church has established thousands of primary, secondary and tertiary institutions throughout the world in the centuries since. The Church and clergymen have also sought at different times to censor texts and scholars. Thus, different schools of opinion exist as to the role and influence of the Church in relation to western letters and learning.

One view, first propounded by Enlightenment philosophers

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

, asserts that the Church's doctrines are entirely superstitious and have hindered the progress of civilization. Communist states

A communist state, also known as a Marxist–Leninist state, is a one-party state in which the totality of the power belongs to a party adhering to some form of Marxism–Leninism, a branch of the communist ideology. Marxism–Leninism was ...

have made similar arguments in their education in order to inculcate a negative view of Catholicism (and religion in general) in their citizens. The most famous incidents cited by such critics are narratives of the Church in relation to Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath who formulated a mathematical model, model of Celestial spheres#Renaissance, the universe that placed heliocentrism, the Sun rather than Earth at its cen ...

, Galileo Galilei

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei ( , , ) or mononymously as Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a poly ...

and Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler (27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, Natural philosophy, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best know ...

.

In opposition to this view, some historians of science, including non-Catholics such as J.L. Heilbron, A.C. Crombie, David Lindberg, Edward Grant

Edward Grant (April 6, 1926 – June 21, 2020) was an American historian of medieval science. He was named a distinguished professor in 1983. Other honors include the 1992 George Sarton Medal, for "a lifetime scholarly achievement" as an histor ...

, Thomas Goldstein, and Ted Davis, have argued that the Church had a significant, positive influence on the development of Western civilization. They hold that, not only did monks save and cultivate the remnants of ancient civilization during the barbarian invasions, but that the Church promoted learning and science through its sponsorship of many universities

A university () is an educational institution, institution of tertiary education and research which awards academic degrees in several Discipline (academia), academic disciplines. ''University'' is derived from the Latin phrase , which roughly ...

which, under its leadership, grew rapidly in Europe in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. St.Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas ( ; ; – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest, the foremost Scholasticism, Scholastic thinker, as well as one of the most influential philosophers and theologians in the W ...

, the Church's "model theologian," argued that reason is in harmony with faith, and that reason can contribute to a deeper understanding of revelation, and so encouraged intellectual development. The Church's priest-scientists, many of whom were Jesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

s, have been among the leading lights in astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest includ ...

, genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinians, Augustinian ...

, geomagnetism, meteorology

Meteorology is the scientific study of the Earth's atmosphere and short-term atmospheric phenomena (i.e. weather), with a focus on weather forecasting. It has applications in the military, aviation, energy production, transport, agricultur ...

, seismology

Seismology (; from Ancient Greek σεισμός (''seismós'') meaning "earthquake" and -λογία (''-logía'') meaning "study of") is the scientific study of earthquakes (or generally, quakes) and the generation and propagation of elastic ...

, and solar physics

Solar physics is the branch of astrophysics that specializes in the study of the Sun. It intersects with many disciplines of pure physics and astrophysics.

Because the Sun is uniquely situated for close-range observing (other stars cannot be re ...

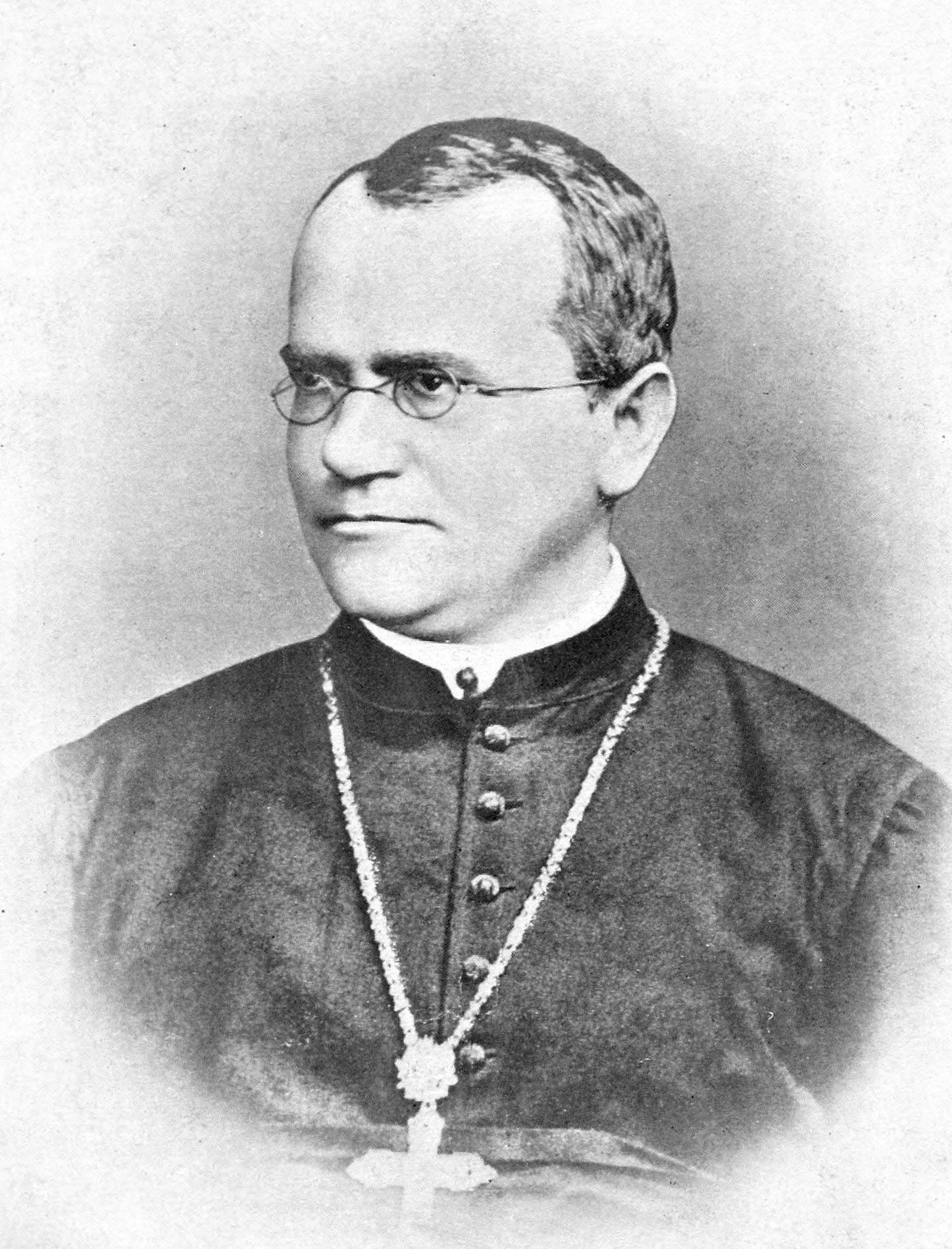

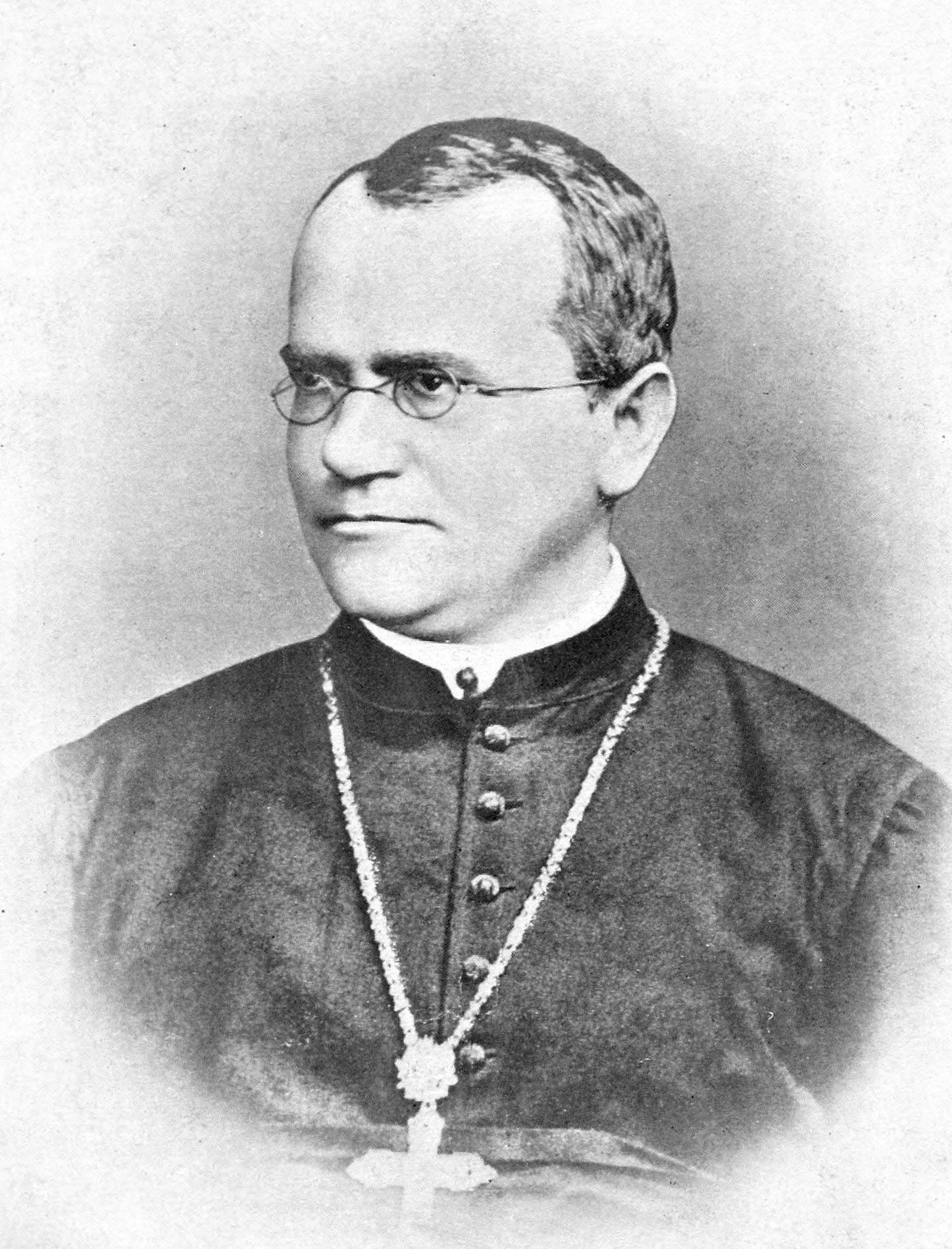

, becoming some of the "fathers" of these sciences. Examples include important churchmen such as the Augustinian abbot Gregor Mendel

Gregor Johann Mendel Order of Saint Augustine, OSA (; ; ; 20 July 1822 – 6 January 1884) was an Austrian Empire, Austrian biologist, meteorologist, mathematician, Augustinians, Augustinian friar and abbot of St Thomas's Abbey, Brno, St. Thom ...

(pioneer in the study of genetics), Roger Bacon

Roger Bacon (; or ', also '' Rogerus''; ), also known by the Scholastic accolades, scholastic accolade ''Doctor Mirabilis'', was a medieval English polymath, philosopher, scientist, theologian and Franciscans, Franciscan friar who placed co ...

(a Franciscan

The Franciscans are a group of related organizations in the Catholic Church, founded or inspired by the Italian saint Francis of Assisi. They include three independent Religious institute, religious orders for men (the Order of Friars Minor bei ...

friar who was one of the early advocates of the scientific method

The scientific method is an Empirical evidence, empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has been referred to while doing science since at least the 17th century. Historically, it was developed through the centuries from the ancient and ...

), and Belgian priest Georges Lemaître

Georges Henri Joseph Édouard Lemaître ( ; ; 17 July 1894 – 20 June 1966) was a Belgian Catholic priest, theoretical physicist, and mathematician who made major contributions to cosmology and astrophysics. He was the first to argue that the ...

(the first to propose the Big Bang

The Big Bang is a physical theory that describes how the universe expanded from an initial state of high density and temperature. Various cosmological models based on the Big Bang concept explain a broad range of phenomena, including th ...

theory; see Religious interpretations of the Big Bang theory). Other notable priest scientists have included Albertus Magnus

Albertus Magnus ( 1200 – 15 November 1280), also known as Saint Albert the Great, Albert of Swabia, Albert von Bollstadt, or Albert of Cologne, was a German Dominican friar, philosopher, scientist, and bishop, considered one of the great ...

, Robert Grosseteste

Robert Grosseteste ( ; ; 8 or 9 October 1253), also known as Robert Greathead or Robert of Lincoln, was an Kingdom of England, English statesman, scholasticism, scholastic philosopher, theologian, scientist and Bishop of Lincoln. He was born of ...

, Nicholas Steno

Niels Steensen (; Latinization (literature), Latinized to Nicolas Steno or Nicolaus Stenonius; 1 January 1638 – 25 November 1686 ) was a Danish people, Danish scientist, a pioneer in both anatomy and geology who became a Catholic Church, ...

, Francesco Grimaldi, Giambattista Riccioli, Roger Boscovich, and Athanasius Kircher

Athanasius Kircher (2 May 1602 – 27 November 1680) was a German Society of Jesus, Jesuit scholar and polymath who published around 40 major works of comparative religion, geology, and medicine. Kircher has been compared to fellow Jes ...

. Even more numerous are Catholic laity involved in science: Henri Becquerel

Antoine Henri Becquerel ( ; ; 15 December 1852 – 25 August 1908) was a French nuclear physicist who shared the 1903 Nobel Prize in Physics with Marie and Pierre Curie for his discovery of radioactivity.

Biography

Family and education

Becq ...

who discovered radioactivity

Radioactive decay (also known as nuclear decay, radioactivity, radioactive disintegration, or nuclear disintegration) is the process by which an unstable atomic nucleus loses energy by radiation. A material containing unstable nuclei is conside ...

; Galvani, Volta, Ampere

The ampere ( , ; symbol: A), often shortened to amp,SI supports only the use of symbols and deprecates the use of abbreviations for units. is the unit of electric current in the International System of Units (SI). One ampere is equal to 1 c ...

, Marconi, pioneers in electricity

Electricity is the set of physical phenomena associated with the presence and motion of matter possessing an electric charge. Electricity is related to magnetism, both being part of the phenomenon of electromagnetism, as described by Maxwel ...

and telecommunications

Telecommunication, often used in its plural form or abbreviated as telecom, is the transmission of information over a distance using electronic means, typically through cables, radio waves, or other communication technologies. These means of ...

; Lavoisier

Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier ( ; ; 26 August 17438 May 1794),

CNRS (

The Catholic

The Catholic

Between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries, the teaching of science in Jesuit schools, as laid down in the ''Ratio atque Institutio Studiorum Societatis Iesu'' ("The Official Plan of studies for the Society of Jesus") of 1599, was almost entirely based on the works of Aristotle.

The

Between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries, the teaching of science in Jesuit schools, as laid down in the ''Ratio atque Institutio Studiorum Societatis Iesu'' ("The Official Plan of studies for the Society of Jesus") of 1599, was almost entirely based on the works of Aristotle.

The

Protestantism has promoted economic growth and entrepreneurship, especially in the period after the

Protestantism has promoted economic growth and entrepreneurship, especially in the period after the

Scientific Elite: Nobel Laureates in the United States

' New York, The Free Press, 1977 , p.68: Protestants turn up among the American-reared laureates in slightly greater proportion to their numbers in the general population. Thus 72 percent of the seventy-one laureates but about two thirds of the American population were reared in one or another Protestant denomination-) Overall, Americans of Protestant background have won a total of 84.2% of all awarded Nobel Prizes in Chemistry, 60% in

In the field of Optics, Nestorian Christian Hunayn ibn-Ishaq's textbook on ophthalmology called the ''Ten Treatises on the Eye'', which was written in 950 A.D., remained the authoritative source on the subject in the western world until the 1800s.

It was a Christian scholar and Bishop from

In the field of Optics, Nestorian Christian Hunayn ibn-Ishaq's textbook on ophthalmology called the ''Ten Treatises on the Eye'', which was written in 950 A.D., remained the authoritative source on the subject in the western world until the 1800s.

It was a Christian scholar and Bishop from

Nestorian

/ref> with the The

The

Christian Scholars and Scientists have made noted contributions to science and technology fields, as well as

Christian Scholars and Scientists have made noted contributions to science and technology fields, as well as

According to ''100 Years of Nobel Prizes'' a review of Nobel prizes award between 1901 and 2000 reveals that (65.4%) of Nobel Prizes Laureates, have identified Christianity in its various forms as their religious preference (427 prizes). Overall, Christians are considered a total of 72.5% in

According to ''100 Years of Nobel Prizes'' a review of Nobel prizes award between 1901 and 2000 reveals that (65.4%) of Nobel Prizes Laureates, have identified Christianity in its various forms as their religious preference (427 prizes). Overall, Christians are considered a total of 72.5% in

100 Years of Nobel Prizes

p. 59 65.3% in

In 1610, Galileo published his ''

In 1610, Galileo published his ''

God-of-the-Gaps Arguments in Light of Luther's Theology of the Cross.

*

Cambridge Christians in Science (CiS) group

Christians in Science website

Ian Ramsey Centre, Oxford

The Society of Ordained Scientists

Mostly

"Science in Christian Perspective" The (ASA)

Canadian Scientific and Christian Affiliation (CSCA)

The International Society for Science & Religion's founding members.(Of various faiths including Christianity)

Association of Christians in the Mathematical Sciences

Secular Humanism.org article on Science and Religion

{{Christianity footer History of science

CNRS (

chemistry

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a physical science within the natural sciences that studies the chemical elements that make up matter and chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules a ...

"; Vesalius

Andries van Wezel (31 December 1514 – 15 October 1564), Latinization of names, latinized as Andreas Vesalius (), was an anatomist and physician who wrote ''De humani corporis fabrica, De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem'' (''On the fabric ...

, founder of modern human anatomy

Human anatomy (gr. ἀνατομία, "dissection", from ἀνά, "up", and τέμνειν, "cut") is primarily the scientific study of the morphology of the human body. Anatomy is subdivided into gross anatomy and microscopic anatomy. Gross ...

; and Cauchy

Baron Augustin-Louis Cauchy ( , , ; ; 21 August 1789 – 23 May 1857) was a French mathematician, engineer, and physicist. He was one of the first to rigorously state and prove the key theorems of calculus (thereby creating real a ...

, one of the mathematicians who laid the rigorous foundations of calculus

Calculus is the mathematics, mathematical study of continuous change, in the same way that geometry is the study of shape, and algebra is the study of generalizations of arithmetic operations.

Originally called infinitesimal calculus or "the ...

.

Throughout history many Catholic clerics have made significant contributions to science. These cleric-scientists include Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath who formulated a mathematical model, model of Celestial spheres#Renaissance, the universe that placed heliocentrism, the Sun rather than Earth at its cen ...

, Gregor Mendel

Gregor Johann Mendel Order of Saint Augustine, OSA (; ; ; 20 July 1822 – 6 January 1884) was an Austrian Empire, Austrian biologist, meteorologist, mathematician, Augustinians, Augustinian friar and abbot of St Thomas's Abbey, Brno, St. Thom ...

, Georges Lemaître

Georges Henri Joseph Édouard Lemaître ( ; ; 17 July 1894 – 20 June 1966) was a Belgian Catholic priest, theoretical physicist, and mathematician who made major contributions to cosmology and astrophysics. He was the first to argue that the ...

, Albertus Magnus

Albertus Magnus ( 1200 – 15 November 1280), also known as Saint Albert the Great, Albert of Swabia, Albert von Bollstadt, or Albert of Cologne, was a German Dominican friar, philosopher, scientist, and bishop, considered one of the great ...

, Roger Bacon

Roger Bacon (; or ', also '' Rogerus''; ), also known by the Scholastic accolades, scholastic accolade ''Doctor Mirabilis'', was a medieval English polymath, philosopher, scientist, theologian and Franciscans, Franciscan friar who placed co ...

, Pierre Gassendi

Pierre Gassendi (; also Pierre Gassend, Petrus Gassendi, Petrus Gassendus; 22 January 1592 – 24 October 1655) was a French philosopher, Catholic priest, astronomer, and mathematician. While he held a church position in south-east France, he a ...

, Roger Joseph Boscovich

Roger Joseph Boscovich (, ; ; ; 18 May 1711 – 13 February 1787) was a Croatian physicist, astronomer, mathematician, philosopher, diplomat, poet, theologian, Jesuit priest, and a polymath from the Republic of Ragusa.Marin Mersenne

Marin Mersenne, OM (also known as Marinus Mersennus or ''le Père'' Mersenne; ; 8 September 1588 – 1 September 1648) was a French polymath whose works touched a wide variety of fields. He is perhaps best known today among mathematicians for ...

, Bernard Bolzano

Bernard Bolzano (, ; ; ; born Bernardus Placidus Johann Nepomuk Bolzano; 5 October 1781 – 18 December 1848) was a Bohemian mathematician, logician, philosopher, theologian and Catholic priest of Italian extraction, also known for his liberal ...

, Francesco Maria Grimaldi

Francesco Maria Grimaldi (2 April 1618 – 28 December 1663) was an Italian Jesuit priest, mathematician and physicist who taught at the Jesuit college in Bologna. He was born in Bologna to Paride Grimaldi and Anna Cattani.

Work

Between 164 ...

, Nicole Oresme

Nicole Oresme (; ; 1 January 1325 – 11 July 1382), also known as Nicolas Oresme, Nicholas Oresme, or Nicolas d'Oresme, was a French philosopher of the later Middle Ages. He wrote influential works on economics, mathematics, physics, astrology, ...

, Jean Buridan

Jean Buridan (; ; Latin: ''Johannes Buridanus''; – ) was an influential 14thcentury French scholastic philosopher.

Buridan taught in the faculty of arts at the University of Paris for his entire career and focused in particular on logic and ...

, Robert Grosseteste

Robert Grosseteste ( ; ; 8 or 9 October 1253), also known as Robert Greathead or Robert of Lincoln, was an Kingdom of England, English statesman, scholasticism, scholastic philosopher, theologian, scientist and Bishop of Lincoln. He was born of ...

, Christopher Clavius

Christopher Clavius, (25 March 1538 – 6 February 1612) was a Jesuit German mathematician, head of mathematicians at the , and astronomer who was a member of the Vatican commission that accepted the proposed calendar invented by Aloysius ...

, Nicolas Steno

Niels Steensen (; Latinized to Nicolas Steno or Nicolaus Stenonius; 1 January 1638 – 25 November 1686 ) was a Danish scientist, a pioneer in both anatomy and geology who became a Catholic bishop in his later years. He has been beatified ...

, Athanasius Kircher

Athanasius Kircher (2 May 1602 – 27 November 1680) was a German Society of Jesus, Jesuit scholar and polymath who published around 40 major works of comparative religion, geology, and medicine. Kircher has been compared to fellow Jes ...

, Giovanni Battista Riccioli

Giovanni Battista Riccioli (17 April 1598 – 25 June 1671) was an Italian astronomer and a Catholic priest in the Jesuit order. He is known, among other things, for his experiments with pendulums and with falling bodies, for his discussion of ...

, William of Ockham

William of Ockham or Occam ( ; ; 9/10 April 1347) was an English Franciscan friar, scholastic philosopher, apologist, and theologian, who was born in Ockham, a small village in Surrey. He is considered to be one of the major figures of medie ...

, and others. The Catholic Church has also produced many lay scientists and mathematicians.

Cistercian in science

Cistercian

The Cistercians (), officially the Order of Cistercians (, abbreviated as OCist or SOCist), are a Catholic religious order of monks and nuns that branched off from the Benedictines and follow the Rule of Saint Benedict, as well as the contri ...

order used its own numbering system, which could express numbers from 0 to 9999 in a single sign. According to one modern Cistercian

The Cistercians (), officially the Order of Cistercians (, abbreviated as OCist or SOCist), are a Catholic religious order of monks and nuns that branched off from the Benedictines and follow the Rule of Saint Benedict, as well as the contri ...

, "enterprise and entrepreneurial spirit" have always been a part of the order's identity, and the Cistercians "were catalysts for development of a market economy" in twelfth-century Europe. Until the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

, most of the technological advances in Europe were made in the monasteries. According to the medievalist Jean Gimpel, their high level of industrial technology facilitated the diffusion of new techniques: "Every monastery had a model factory, often as large as the church and only several feet away, and waterpower drove the machinery of the various industries located on its floor."Gimpel, p 67. Cited by Woods. Waterpower was used for crushing wheat, sieving flour, fulling cloth and tanning – a "level of technological achievement hat

A hat is a Headgear, head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorpor ...

could have been observed in practically all" of the Cistercian monasteries.

The English science historian James Burke examines the impact of Cistercian waterpower, derived from Roman watermill technology such as that of Barbegal aqueduct and mill

The Barbegal aqueduct and mills was a Roman watermill complex in the commune of Fontvieille, Bouches-du-Rhône, near the town of Arles, in southern France. The complex has been referred to as "the greatest known concentration of mechanical powe ...

near Arles

Arles ( , , ; ; Classical ) is a coastal city and Communes of France, commune in the South of France, a Subprefectures in France, subprefecture in the Bouches-du-Rhône Departments of France, department of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Reg ...

in the fourth of his ten-part '' Connections'' TV series, called "Faith in Numbers". The Cistercians

The Cistercians (), officially the Order of Cistercians (, abbreviated as OCist or SOCist), are a Catholic religious order of monks and nuns that branched off from the Benedictines and follow the Rule of Saint Benedict, as well as the contri ...

made major contributions to culture and technology in medieval Europe: Cistercian architecture

Cistercian architecture is a style of architecture associated with the churches, monasteries and abbeys of the Roman Catholic Cistercian Order. It was heavily influenced by Bernard of Clairvaux (d. 1153), who believed that churches should avoid ...

is considered one of the most beautiful styles of medieval architecture