Chester Nimitz on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Chester William Nimitz (; 24 February 1885 – 20 February 1966) was a

Originally, Nimitz applied to

Originally, Nimitz applied to

In June 1923, he became aide and assistant chief of staff to the Commander, Battle Fleet, and later to the Commander in Chief, United States Fleet. In August 1926, he went to the

In June 1923, he became aide and assistant chief of staff to the Commander, Battle Fleet, and later to the Commander in Chief, United States Fleet. In August 1926, he went to the

Ten days after the

Ten days after the

the

Nimitz married Catherine Vance Freeman (22 March 1892 – 1 February 1979) on 9 April 1913, in Wollaston, Massachusetts. Nimitz and his wife had four children:

# Catherine Vance "Kate" (22 February 1914, Brooklyn, NY – 14 January 2015)Potter. – p. 125.

# Chester William "Chet" Jr. (1915–2002)

# Anna Elizabeth "Nancy" (1919–2003)

# Mary Manson (1931–2006)

Catherine Vance graduated from the

Nimitz married Catherine Vance Freeman (22 March 1892 – 1 February 1979) on 9 April 1913, in Wollaston, Massachusetts. Nimitz and his wife had four children:

# Catherine Vance "Kate" (22 February 1914, Brooklyn, NY – 14 January 2015)Potter. – p. 125.

# Chester William "Chet" Jr. (1915–2002)

# Anna Elizabeth "Nancy" (1919–2003)

# Mary Manson (1931–2006)

Catherine Vance graduated from the

Dominican Sisters of San Rafael

working at the

Besides the honor of a United States Great Americans series 50¢ postage stamp, the following institutions and locations have been named in honor of Nimitz:

* , the first of her class of ten nuclear-powered supercarriers, which was commissioned in 1975 and remains in service

* Nimitz Foundation, established in 1970, which funds the National Museum of the Pacific War and the Admiral Nimitz Museum,

Besides the honor of a United States Great Americans series 50¢ postage stamp, the following institutions and locations have been named in honor of Nimitz:

* , the first of her class of ten nuclear-powered supercarriers, which was commissioned in 1975 and remains in service

* Nimitz Foundation, established in 1970, which funds the National Museum of the Pacific War and the Admiral Nimitz Museum,

Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz Statue

commissioned by the Naval Order of the United States, is situated near the bow of the

"The Strategic Leadership of Admiral Chester W. Nimitz"

. (Army War College Carlisle Barracks, 2012). * * Stone, Christopher B. "Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz: Leadership Forged Through Adversity" (PhD dissertation, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 2018)

Excerpt

* Wildenberg, Thomas

"Chester Nimitz and the development of fueling at sea"

''Naval War College Review'' 46.4 (1993): 52–62.

1944 interview with Admiral Nimitz

from '' Yank''.

National Museum of the Pacific War

Nimitz State Historic Site

in Fredericksburg, Texas

"The Navy's Part in the World War". (26 November 1945)

A speech by Nimitz from th

Commonwealth Club of California Records

at th

Hoover Institution Archives

*

Guide to the Chester W. Nimitz Papers, 1941–1966 MS 236

held by Special Collections & Archives, Nimitz Library at the United States Naval Academy {{DEFAULTSORT:Nimitz, Chester 1885 births 1966 deaths American five-star officers Battle of Midway American people of German descent Burials at Golden Gate National Cemetery Chiefs of Naval Operations Military personnel from Texas German-American culture in Texas Grand Crosses of the Order of George I High commissioners of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands Naval War College alumni People from Fredericksburg, Texas People from Kerrville, Texas United States Naval Academy alumni United States Navy admirals United States Navy World War II admirals United States Navy personnel who were court-martialed Honorary Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath Knights Grand Cross of the Military Order of Savoy Knights Grand Cross of the Order of Orange-Nassau Grand Crosses of the Order of the Crown (Belgium) Officers of the Legion of Honour American recipients of the Croix de guerre (Belgium) Recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (US Army) Recipients of the Order of Naval Merit (Brazil) Recipients of the Order of the Liberator General San Martin Recipients of the Order of the Sacred Tripod Recipients of the Navy Distinguished Service Medal People from Clinton Hill, Brooklyn United States Navy personnel of World War I

fleet admiral

An admiral of the fleet or shortened to fleet admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, usually equivalent to field marshal and marshal of the air force. An admiral of the fleet is typically senior to an admiral.

It is also a generic ter ...

in the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

. He played a major role in the naval history of World War II as Commander in Chief, US Pacific Fleet, and Commander in Chief, Pacific Ocean Areas

Pacific Ocean Areas (POA) was a major Allied military command in the Pacific Ocean theater of World War II. It was one of four major Allied commands during the Pacific War and one of three United States commands in the Asiatic-Pacific Theater. ...

, commanding Allied air, land, and sea forces during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

Nimitz was the leading US Navy authority on submarine

A submarine (often shortened to sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. (It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability.) The term "submarine" is also sometimes used historically or infor ...

s. Qualified in submarines during his early years, he later oversaw the conversion of these vessels' propulsion from gasoline to diesel, and then later was key in acquiring approval to build the world's first nuclear-powered

Nuclear power is the use of nuclear reactions to produce electricity. Nuclear power can be obtained from nuclear fission, nuclear decay and nuclear fusion reactions. Presently, the vast majority of electricity from nuclear power is produced b ...

submarine, , whose propulsion system later completely superseded diesel-powered submarines in the US. He also, beginning in 1917, was the Navy's leading developer of underway replenishment

Underway replenishment (UNREP) (United States Navy, U.S. Navy) or replenishment at sea (RAS) (North Atlantic Treaty Organization/Commonwealth of Nations) is a method of transferring fuel, munitions, and stores from one ship to another while unde ...

techniques, the tool which during the Pacific war would allow the US fleet to operate away from port almost indefinitely. The chief of the Navy's Bureau of Navigation in 1939, Nimitz served as Chief of Naval Operations

The chief of naval operations (CNO) is the highest-ranking officer of the United States Navy. The position is a statutory office () held by an Admiral (United States), admiral who is a military adviser and deputy to the United States Secretary ...

from 1945 until 1947. He was the United States' last surviving officer who served in the rank of fleet admiral. The supercarrier, the lead ship of her class, is named after him.

Early life and education

Nimitz, aGerman Texan

Texas Germans () are descendants of Germans who settled in Texas since the 1830s. The arriving Germans tended to cluster in ethnic enclaves; the majority settled in a broad, fragmented belt across the south-central part of the state, where many be ...

, was born the son of Anna Josephine (née Henke) and Chester Bernhard Nimitz on 24 February 1885, in Fredericksburg, Texas

Fredericksburg () is a city in and the county seat of Gillespie County, Texas, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 Census, this city had a population of 10,875.

Fredericksburg was founded in 1846 and named after Prince Frede ...

, where his grandfather's hotel is now the National Museum of the Pacific War. His frail, rheumatic

Rheumatology () is a branch of medicine devoted to the diagnosis and management of disorders whose common feature is inflammation in the bones, muscles, joints, and internal organs. Rheumatology covers more than 100 different complex diseases, c ...

father had died six months earlier, on 14 August 1884. In 1890, Anna married William Nimitz (1864–1943), Chester B. Nimitz's brother. He was significantly influenced by his German-born paternal grandfather, Charles Henry Nimitz, a former seaman in the German Merchant Marine, who taught him, "the sea – like life itself – is a stern taskmaster. The best way to get along with either is to learn all you can, then do your best and don't worry – especially about things over which you have no control". His grandfather had become a Texas Ranger in the Texas Mounted Volunteers in 1851 and later served as captain of the Gillespie Rifles Company in the Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army (CSA), also called the Confederate army or the Southern army, was the Military forces of the Confederate States, military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) duri ...

during the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

.

Originally, Nimitz applied to

Originally, Nimitz applied to West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

in hopes of becoming an Army

An army, ground force or land force is an armed force that fights primarily on land. In the broadest sense, it is the land-based military branch, service branch or armed service of a nation or country. It may also include aviation assets by ...

officer, but no appointments were available. James L. Slayden, US Representative for Texas's 12th congressional district, told him that he had one appointment available for the United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (USNA, Navy, or Annapolis) is a United States Service academies, federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as United States Secre ...

and that he would award it to the best-qualified candidate. Nimitz felt that this was his only opportunity for further education and spent extra time studying to earn the appointment. He was appointed to the Naval Academy by Slayden in 1901, and graduated with distinction on 30 January 1905, seventh in a class of 114.

Military career

Early career

Nimitz joined thebattleship

A battleship is a large, heavily naval armour, armored warship with a main battery consisting of large naval gun, guns, designed to serve as a capital ship. From their advent in the late 1880s, battleships were among the largest and most form ...

at San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

, and cruised on her to the Far East. In September 1906, he was transferred to the cruiser ; on 31 January 1907, after the two years at sea as a warrant officer

Warrant officer (WO) is a Military rank, rank or category of ranks in the armed forces of many countries. Depending on the country, service, or historical context, warrant officers are sometimes classified as the most junior of the commissioned ...

then required by law, he was commissioned as an ensign

Ensign most often refers to:

* Ensign (flag), a flag flown on a vessel to indicate nationality

* Ensign (rank), a navy (and former army) officer rank

Ensign or The Ensign may also refer to:

Places

* Ensign, Alberta, Alberta, Canada

* Ensign, Ka ...

. Remaining on Asiatic Station in 1907, he successively served on the gunboat

A gunboat is a naval watercraft designed for the express purpose of carrying one or more guns to bombard coastal targets, as opposed to those military craft designed for naval warfare, or for ferrying troops or supplies.

History Pre-steam ...

, destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, maneuverable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy, or carrier battle group and defend them against a wide range of general threats. They were conceived i ...

, and cruiser .

The destroyer ''Decatur'' ran aground on a mud bank in the Philippines on 7 July 1908, while under the command of Ensign Nimitz. The incident was the result of a navigational error. Nimitz had failed to check the harbor's tide tables and tried Batangas' harbor when the water level was low, leaving ''Decatur'' stuck until the tide rose again the next morning, and she was pulled free by a small steamer. Following the grounding, a naval board of inquiry was convened to investigate the circumstances. The board found that Nimitz had indeed made an error in judgment, but they did not recommend any punitive measures against him. Instead, he received a letter of reprimand.

Nimitz returned to the United States on board USS ''Ranger'' when that vessel was converted to a school ship

A training ship is a ship used to train students as sailors. The term is mostly used to describe ships employed by navies to train future officers. Essentially there are two types: those used for training at sea and old Hulk (ship type), hulks us ...

, and in January 1909, began instruction in the First Submarine Flotilla. In May of that year, he was given command of the flotilla, with additional duty in command of , later renamed ''A-1''. He was promoted directly from ensign to lieutenant in January 1910. He commanded (later renamed ''C-5'') when that submarine was commissioned on 2 February 1910, and on 18 November 1910, assumed command of (later renamed ''D-1'').

In the latter command, he had additional duty from 10 October 1911, as Commander 3rd Submarine Division Atlantic Torpedo Fleet. In November 1911, he was ordered to the Boston Navy Yard

The Boston Navy Yard, originally called the Charlestown Navy Yard and later Boston Naval Shipyard, was one of the oldest shipbuilding facilities in the United States Navy. It was established in 1801 as part of the recent establishment of t ...

, to assist in fitting out and assumed command of that submarine, which had been renamed ''E-1'', at her commissioning on 14 February 1912. On the monitor

Monitor or monitor may refer to:

Places

* Monitor, Alberta

* Monitor, Indiana, town in the United States

* Monitor, Kentucky

* Monitor, Oregon, unincorporated community in the United States

* Monitor, Washington

* Monitor, Logan County, Wes ...

''Tonopah'' (then employed as a submarine tender) on 20 March 1912, he rescued Fireman Second Class W. J. Walsh from drowning, receiving a Silver Lifesaving Medal for his action.

After commanding the Atlantic Submarine Flotilla from May 1912 to March 1913, he supervised the building of diesel engine

The diesel engine, named after the German engineer Rudolf Diesel, is an internal combustion engine in which Combustion, ignition of diesel fuel is caused by the elevated temperature of the air in the cylinder due to Mechanics, mechanical Compr ...

s for the fleet oil tanker

An oil tanker, also known as a petroleum tanker, is a ship designed for the bulk cargo, bulk transport of petroleum, oil or its products. There are two basic types of oil tankers: crude tankers and product tankers. Crude tankers move large quant ...

, under construction at the New London Ship and Engine Company, Groton, Connecticut

Groton ( ) is a town in New London County, Connecticut, United States, located on the Thames River (Connecticut), Thames River. It is the home of General Dynamics Electric Boat, which is the major contractor for submarine work for the United St ...

.

World War I

In the summer of 1913, Nimitz (who spoke fluent German) studied engines at the Maschinenfabrik-Augsburg-Nürnberg (M.A.N.) diesel engine plants inNuremberg

Nuremberg (, ; ; in the local East Franconian dialect: ''Nämberch'' ) is the Franconia#Towns and cities, largest city in Franconia, the List of cities in Bavaria by population, second-largest city in the States of Germany, German state of Bav ...

, Germany, and Ghent

Ghent ( ; ; historically known as ''Gaunt'' in English) is a City status in Belgium, city and a Municipalities of Belgium, municipality in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is the capital and largest city of the Provinces of Belgium, province ...

, Belgium. Returning to the New York Navy Yard

The Brooklyn Navy Yard (originally known as the New York Navy Yard) is a shipyard and industrial complex in northwest Brooklyn in New York City, New York, U.S. The Navy Yard is located on the East River in Wallabout Bay, a semicircular bend ...

, he became executive

Executive ( exe., exec., execu.) may refer to:

Role or title

* Executive, a senior management role in an organization

** Chief executive officer (CEO), one of the highest-ranking corporate officers (executives) or administrators

** Executive dir ...

and engineer officer of ''Maumee'' at her commissioning on 23 October 1916.

After the United States declared war on Germany in April 1917, Nimitz was chief engineer of ''Maumee'' while the vessel served as a refueling ship for the first squadron of US Navy destroyers to cross the Atlantic, to take part in the war. Under his supervision, ''Maumee'' conducted the first-ever underway refuelings. On 10 August 1917, Nimitz became aide to Rear Admiral Samuel S. Robison, Commander, Submarine Force, US Atlantic Fleet ( ComSubLant).

On 6 February 1918, Nimitz was appointed chief of staff and was awarded a Letter of Commendation for meritorious service as COMSUBLANT's chief of staff. On 16 September, he reported to the office of the Chief of Naval Operations, and on October 25 was given additional duty as senior member, Board of Submarine Design.

Interwar Period

From May 1919 to June 1920, Nimitz served as executive officer of the battleship . He then commanded the cruiser with additional duty in command of Submarine Division 14, based atPearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the Reci ...

, Hawaii. Nimitz, assisted by four earnest Chief Petty Officers, supervised the construction of Submarine Base Pearl Harbor on a triangle-shaped, overgrown piece of land at the juncture of Southeast Loch and Quarry Loch, and served as the base's first commanding officer. During this tour, he also conducted an investigation into the R-14 sailing incident. His handling of the disciplinary action in the aftermath of the investigation was considered a model of even-handed fairness, cementing his reputation as a solid and capable leader. Returning to the mainland in the summer of 1922, he studied at the Naval War College

The Naval War College (NWC or NAVWARCOL) is the staff college and "Home of Thought" for the United States Navy at Naval Station Newport in Newport, Rhode Island. The NWC educates and develops leaders, supports defining the future Navy and associa ...

, Newport, Rhode Island

Newport is a seaside city on Aquidneck Island in Rhode Island, United States. It is located in Narragansett Bay, approximately southeast of Providence, Rhode Island, Providence, south of Fall River, Massachusetts, south of Boston, and nort ...

. In June 1923, he became aide and assistant chief of staff to the Commander, Battle Fleet, and later to the Commander in Chief, United States Fleet. In August 1926, he went to the

In June 1923, he became aide and assistant chief of staff to the Commander, Battle Fleet, and later to the Commander in Chief, United States Fleet. In August 1926, he went to the University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California), is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Berkeley, California, United States. Founded in 1868 and named after t ...

, where he established one of the first Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps

The Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps (NROTC) program is a college-based, commissioned officer training program of the United States Navy and the United States Marine Corps.

Origins

A pilot Naval Reserve unit was established in September 1924 ...

units and successfully advocated for the program's expansion.

Nimitz lost part of a finger in an accident with a diesel engine, saving the rest of it only when the machine briefly jammed against his Annapolis

Annapolis ( ) is the capital of the U.S. state of Maryland. It is the county seat of Anne Arundel County and its only incorporated city. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east o ...

ring.

In June 1929, he took command of Submarine Division 20. In June 1931, he assumed command of the destroyer tender

A destroyer tender or destroyer depot ship is a type of depot ship: an auxiliary ship designed to provide maintenance support to a flotilla of destroyers or other small warships. The use of this class has faded from its peak in the first half of ...

and the destroyers out of commission at San Diego, California

San Diego ( , ) is a city on the Pacific coast of Southern California, adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a population of over 1.4 million, it is the List of United States cities by population, eighth-most populous city in t ...

. In October 1933, he took command of the cruiser and deployed to the Far East

The Far East is the geographical region that encompasses the easternmost portion of the Asian continent, including North Asia, North, East Asia, East and Southeast Asia. South Asia is sometimes also included in the definition of the term. In mod ...

, where in December, ''Augusta'' became the flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of navy, naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically ...

of the Asiatic Fleet

The United States Asiatic Fleet was a fleet of the United States Navy during much of the first half of the 20th century. Before World War II, the fleet patrolled the Philippine Islands. Much of the fleet was destroyed by the Japanese by Februar ...

. While in command of the Augusta, his legal aide was Chesty Puller.

In April 1935, Nimitz returned home for three years as assistant chief of the Bureau of Navigation, before becoming commander, Cruiser Division 2, Battle Force. In September 1938 he took command of Battleship Division 1, Battle Force. During this time, Nimitz conducted experiments in the underway refueling of large ships which would prove a key element in the Navy's success in the war to come. "Tests were planned for the spring of 1939 une 1939using elements of the fleet left on the West Coast while the rest of the fleet was in the Caribbean participating in Fleet Problem XX. Nimitz was scheduled to remain on the West Coast aboard his flagship the Arizona. The aircraft carrier Saratoga, the heavy cruisers and Vincennes, and the light cruiser Trenton would also be left behind. These ships, with their escorts and at least one oiler, would constitute Task Force 7. Nimitz, as senior officer present, would be in command."

On 15 June 1939, he was appointed chief of the Bureau of Navigation.

From 1940 to 1941, Nimitz served as president of the Army Navy Country Club, in Arlington, Virginia.

World War II

Ten days after the

Ten days after the attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Empire of Japan on the United States Pacific Fleet at Naval Station Pearl Harbor, its naval base at Pearl Harbor on Oahu, Territory of ...

on 7 December 1941, Rear Admiral Nimitz was selected by President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

to be the commander-in-chief of the United States Pacific Fleet

The United States Pacific Fleet (USPACFLT) is a theater-level component command of the United States Navy, located in the Pacific Ocean. It provides naval forces to the Indo-Pacific Command. Fleet headquarters is at Joint Base Pearl Harbor� ...

(CINCPACFLT). Nimitz immediately departed Washington for Hawaii and took command in a ceremony on the top deck of the submarine . He was promoted to the rank of admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in many navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force. Admiral is ranked above vice admiral and below admiral of ...

, effective 31 December 1941, upon assuming command. The change of command ceremony would normally have taken place aboard a battleship; however, every battleship in Pearl Harbor had been either sunk or damaged during the attack. Assuming command at the most critical period of the war in the Pacific, Admiral Nimitz organized his forces to halt the Japanese advance, despite the shortage of ships, planes, and supplies. He had a significant advantage in that the United States had cracked the Japanese diplomatic naval code and had made progress on the naval code JN-25. The Japanese had kept radio silence before the attack on Pearl Harbor, although events were then moving so rapidly they had to rely on coded radio messages they did not realize were being read in Hawaii.

On 24 March 1942, the newly formed US-British Combined Chiefs of Staff

The Combined Chiefs of Staff (CCS) was the supreme military staff for the United States and Britain during World War II. It set all the major policy decisions for the two nations, subject to the approvals of British Prime Minister Winston Churchi ...

issued a directive designating the Pacific theater an area of American strategic responsibility. Six days later, the US Joint Chiefs of Staff

The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) is the body of the most senior uniformed leaders within the United States Department of Defense, which advises the president of the United States, the secretary of defense, the Homeland Security Council and ...

(JCS) divided the theater into three areas: the Pacific Ocean Areas

Pacific Ocean Areas (POA) was a major Allied military command in the Pacific Ocean theater of World War II. It was one of four major Allied commands during the Pacific War and one of three United States commands in the Asiatic-Pacific Theater. ...

, the Southwest Pacific Area (commanded by General Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American general who served as a top commander during World War II and the Korean War, achieving the rank of General of the Army (United States), General of the Army. He served with dis ...

), and the Southeast Pacific Area

The Southeast Pacific Area was one of the designated area commands created by the Combined Chiefs of Staff in the Pacific region during World War II. It was responsible to the Joint Chiefs of Staff via the Commander-in-Chief of the United States Na ...

. The JCS designated Nimitz as "Commander in Chief, Pacific Ocean Areas", with operational control over all Allied units (air, land, and sea) in that area.

Nimitz, in Hawaii, and his superior Admiral Ernest King

Ernest Joseph King (23 November 1878 – 25 June 1956) was a Fleet admiral (United States), fleet admiral in the United States Navy who served as Commander in Chief, United States Fleet (COMINCH) and Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) during Worl ...

, the Chief of Naval Operations, in Washington, rejected the plan of General Douglas MacArthur to advance on Japan through New Guinea and the Philippines and Formosa. Instead, they proposed an island-hopping plan that would allow them to bypass most of the Japanese strength in the Central Pacific until they reached Okinawa. President Roosevelt compromised, giving both MacArthur and Nimitz their own theaters. The two Pacific theaters were favored, to the dismay of generals George Marshall

George Catlett Marshall Jr. (31 December 1880 – 16 October 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the United States Army, Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army under pres ...

and Dwight Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

, who favored a Germany-first strategy. King and Nimitz provided MacArthur with some naval forces but kept most of the carriers. However, when the time came to plan an invasion of Japan, MacArthur was given overall command.

Nimitz faced superior Japanese forces at the crucial defensive actions of the Battle of the Coral Sea

The Battle of the Coral Sea, from 4 to 8 May 1942, was a major naval battle between the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) and naval and air forces of the United States and Australia. Taking place in the Pacific Theatre of World War II, the battle ...

and the Battle of Midway

The Battle of Midway was a major naval battle in the Pacific Ocean theater of World War II, Pacific Theater of World War II that took place on 4–7 June 1942, six months after Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor and one month after the Battle of t ...

. The Battle of the Coral Sea, while a loss in terms of total damage suffered, has been described as resulting in the strategic success of turning back an apparent Japanese invasion of Port Moresby

(; Tok Pisin: ''Pot Mosbi''), also referred to as Pom City or simply Moresby, is the capital and largest city of Papua New Guinea. It is one of the largest cities in the southwestern Pacific (along with Jayapura) outside of Australia and New ...

on the island of New Guinea. Two Japanese carriers were temporarily taken out of action in the battle, which would deprive the Japanese of their use in the Midway operation that shortly followed. The Navy's intelligence team reasoned that the Japanese would be attacking Midway, so Nimitz moved all his available forces to the defense. The severe losses in Japanese carriers at Midway affected the balance of naval air power during the remainder of 1942 and were crucial in neutralizing Japanese offensive threats in the South Pacific. Naval engagements during the Battle of Guadalcanal

The Guadalcanal campaign, also known as the Battle of Guadalcanal and codenamed Operation Watchtower by the United States, was an Allied offensive against forces of the Empire of Japan in the Solomon Islands during the Pacific Theater of W ...

left both forces severely depleted. However, with the allied advantage in land-based air-power, the results were sufficient to secure Guadalcanal. The US and allied forces then undertook to neutralize remaining Japanese offensive threats with the Solomon Islands campaign

The Solomon Islands campaign was a major military campaign, campaign of the Pacific War during World War II. The campaign began with the Empire of Japan, Japanese seizure of several areas in the British Solomon Islands and Bougainville Island, B ...

and the New Guinea campaign

The New Guinea campaign of the Pacific War lasted from January 1942 until the end of the war in August 1945. During the initial phase in early 1942, the Empire of Japan invaded the Territory of New Guinea on 23 January and Territory of Papua on ...

, while building capabilities for major fleet actions. In 1943, Midway became a forward submarine base, greatly enhancing US capabilities against Japanese shipping.

In terms of combat, 1943 was a relatively quiet year, but it proved decisive inasmuch as Nimitz gained the materiel

Materiel or matériel (; ) is supplies, equipment, and weapons in military supply-chain management, and typically supplies and equipment in a commerce, commercial supply chain management, supply chain context.

Military

In a military context, ...

and manpower needed to launch major fleet offensives to destroy Japanese power in the central Pacific region. This drive opened with the Gilbert and Marshall Islands campaign

The Gilbert and Marshall Islands campaign was a series of engagements fought from August 1942 to February 1944, in the Pacific War, Pacific theatre of World War II between the United States and Empire of Japan, Japan. They were the first battl ...

from November 1943 to February 1944, followed by the destruction of the strategic Japanese base at Truk Lagoon, and the Marianas campaign that brought the Japanese homeland within range of new strategic bombers. Nimitz's forces inflicted a decisive defeat on the Japanese fleet in the Battle of the Philippine Sea

The Battle of the Philippine Sea was a major naval battle of World War II on 19–20 June 1944 that eliminated the Imperial Japanese Navy's ability to conduct large-scale carrier actions. It took place during the United States' amphibious r ...

(19–20 June 1944), which allowed the capture of Saipan

Saipan () is the largest island and capital of the Northern Mariana Islands, an unincorporated Territories of the United States, territory of the United States in the western Pacific Ocean. According to 2020 estimates by the United States Cens ...

, Guam

Guam ( ; ) is an island that is an Territories of the United States, organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. Guam's capital is Hagåtña, Guam, Hagåtña, and the most ...

, and Tinian

Tinian () is one of the three principal islands of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI). Together with uninhabited neighboring Aguiguan, it forms Tinian Municipality, one of the four constituent municipalities of the Northern ...

. His Fleet Forces isolated enemy-held bastions on the central and eastern Caroline Islands

The Caroline Islands (or the Carolines) are a widely scattered archipelago of tiny islands in the western Pacific Ocean, to the north of New Guinea. Politically, they are divided between the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) in the cen ...

and secured in quick succession Peleliu

Peleliu (or Beliliou) is an island in the island nation of Palau. Peleliu, along with two small islands to its northeast, forms one of the sixteen states of Palau. The island is notable as the location of the Battle of Peleliu in World War II.

...

, Angaur

, or in Palauan, is an island and state in the Island country, island nation of Palau.

History

Angaur was traditionally divided among some eight clans. Traditional features within clan areas represent important symbols giving identity to fam ...

, and Ulithi

Ulithi (, , or ; pronounced roughly as YOU-li-thee) is an atoll in the Caroline Islands of the western Pacific Ocean, about east of Yap, within Yap State.

Name

The name of the island goes back to Chuukic languages, Proto-Chuukic ''*úlú-diw ...

. In the Philippines, his ships destroyed much of the remaining Japanese naval power at the Battle of Leyte Gulf

The Battle of Leyte Gulf () 23–26 October 1944, was the largest naval battle of World War II and by some criteria the largest naval battle in history, with over 200,000 naval personnel involved.

By late 1944, Japan possessed fewer capital sh ...

, that lasted from 24 to 26 October 1944. With the loss of the Philippines, Japan's energy supply routes from Indonesia came under direct threat, crippling their war effort.

By act of Congress, passed on 14 December 1944, the rank of fleet admiral

An admiral of the fleet or shortened to fleet admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, usually equivalent to field marshal and marshal of the air force. An admiral of the fleet is typically senior to an admiral.

It is also a generic ter ...

– the highest rank in the Navy – was established. The next day President Franklin Roosevelt appointed Nimitz to that rank. Nimitz took the oath of that office on 19 December 1944. In January 1945, Nimitz moved the headquarters of the Pacific Fleet forward from Pearl Harbor to Guam for the remainder of the war. Nimitz's wife remained in the continental United States for the duration of the war and did not join her husband in Hawaii or Guam. In 1945, Nimitz's forces launched successful amphibious assaults on Iwo Jima

is one of the Japanese Volcano Islands, which lie south of the Bonin Islands and together with them make up the Ogasawara Subprefecture, Ogasawara Archipelago. Together with the Izu Islands, they make up Japan's Nanpō Islands. Although sout ...

and Okinawa

most commonly refers to:

* Okinawa Prefecture, Japan's southernmost prefecture

* Okinawa Island, the largest island of Okinawa Prefecture

* Okinawa Islands, an island group including Okinawa itself

* Okinawa (city), the second largest city in th ...

and his carriers raided the home waters of Japan. In addition, Nimitz also arranged for the Army Air Force to mine the Japanese ports and waterways by air with B-29 Superfortress

The Boeing B-29 Superfortress is a retired American four-engined Propeller (aeronautics), propeller-driven heavy bomber, designed by Boeing and flown primarily by the United States during World War II and the Korean War. Named in allusion to ...

es in a successful mission called Operation Starvation

Operation Starvation was a naval mining operation conducted in World War II by the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) to disrupt Japanese shipping.

Operation

The mission was initiated at the insistence of Admiral Chester Nimitz who wanted ...

, which severely interrupted Japanese logistics.

On 2 September 1945, Nimitz signed as representative of the United States when Japan formally surrendered on board in Tokyo Bay

is a bay located in the southern Kantō region of Japan spanning the coasts of Tokyo, Kanagawa Prefecture, and Chiba Prefecture, on the southern coast of the island of Honshu. Tokyo Bay is connected to the Pacific Ocean by the Uraga Channel. Th ...

. On 5 October 1945, which had been officially designated as "Nimitz Day" in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, Nimitz was personally presented a second Gold Star for the third award of the Navy Distinguished Service Medal

The Navy Distinguished Service Medal is a military decoration of the United States Navy and United States Marine Corps which was first created in 1919 and is presented to Sailors and Marines to recognize distinguished and exceptionally meritorio ...

by President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. As the 34th vice president in 1945, he assumed the presidency upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt that year. Subsequen ...

"for exceptionally meritorious service as Commander in Chief, U.S. Pacific Fleet and Pacific Ocean Areas, from June 1944 to August 1945".

Post war

On 26 November 1945, Nimitz's nomination asChief of Naval Operations

The chief of naval operations (CNO) is the highest-ranking officer of the United States Navy. The position is a statutory office () held by an Admiral (United States), admiral who is a military adviser and deputy to the United States Secretary ...

(CNO) was confirmed by the US Senate, and on December 15, 1945, he relieved Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King. He had assured the President that he was willing to serve as the CNO for one two-year term, but no longer. He tackled the difficult task of reducing the most powerful navy in the world to a fraction of its war-time strength while establishing and overseeing active and reserve fleets with the strength and readiness required to support national policy.

For the postwar trial of German Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz

Karl Dönitz (; 16 September 1891 – 24 December 1980) was a German grand admiral and convicted war criminal who, following Adolf Hitler's Death of Adolf Hitler, suicide, succeeded him as head of state of Nazi Germany during the Second World ...

at the Nuremberg Trials #REDIRECT Nuremberg trials

{{redirect category shell, {{R from other capitalisation{{R from move ...

in 1946, Nimitz furnished an affidavit

An ( ; Medieval Latin for "he has declared under oath") is a written statement voluntarily made by an ''affiant'' or ''deposition (law), deponent'' under an oath or affirmation which is administered by a person who is authorized to do so by la ...

in support of the practice of unrestricted submarine warfare

Unrestricted submarine warfare is a type of naval warfare in which submarines sink merchant ships such as freighters and tankers without warning. The use of unrestricted submarine warfare has had significant impacts on international relations in ...

, a practice that he himself had employed throughout the war in the Pacific. This evidence is widely credited as a reason why Dönitz was sentenced to only 10 years of imprisonment.Judgement: Dönitzthe

Avalon Project

The Avalon Project is a digital library of documents relating to law, history and diplomacy. The project is part of the Yale Law School Lillian Goldman Law Library.

The project contains online electronic copies of documents dating back to the b ...

at the Yale Law School

Yale Law School (YLS) is the law school of Yale University, a Private university, private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. It was established in 1824. The 2020–21 acceptance rate was 4%, the lowest of any law school in the United ...

.

Nimitz endorsed an entirely new course for the US Navy's future by way of supporting then-Captain Hyman G. Rickover's chain-of-command-circumventing proposal in 1947 to build , the world's first nuclear-powered vessel. As is noted at a display at the Nimitz Museum in Fredericksburg, Texas: "Nimitz's greatest legacy as CNO is arguably his support of Admiral Hyman Rickover's effort to convert the submarine fleet from diesel to nuclear propulsion".

Inactive duty as a fleet admiral

Nimitz retired from office as CNO on 15 December 1947, and received a third Gold Star in lieu of a fourth Navy Distinguished Service Medal. However, since the rank of fleet admiral is a lifetime appointment, he remained on active duty for the rest of his life, with full pay and benefits. He and his wife, Catherine, moved toBerkeley, California

Berkeley ( ) is a city on the eastern shore of San Francisco Bay in northern Alameda County, California, United States. It is named after the 18th-century Anglo-Irish bishop and philosopher George Berkeley. It borders the cities of Oakland, Cali ...

. After he suffered a serious fall in 1964, he and Catherine moved to US Naval quarters on Yerba Buena Island

Yerba Buena Island ( Spanish: ''Isla Yerba Buena'') sits in San Francisco Bay within the borders of the City and County of San Francisco. The Yerba Buena Tunnel runs through its center and connects the western and eastern spans of the San Fran ...

in the San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay (Chochenyo language, Chochenyo: 'ommu) is a large tidal estuary in the United States, U.S. state of California, and gives its name to the San Francisco Bay Area. It is dominated by the cities of San Francisco, California, San ...

.

In San Francisco, Nimitz served in the mostly ceremonial post as a special assistant to the Secretary of the Navy in the Western Sea Frontier. He worked to help restore goodwill with Japan after World War II by helping to raise funds for the restoration of the Japanese Imperial Navy battleship , Admiral Heihachiro Togo's flagship at the Battle of Tsushima

The Battle of Tsushima (, ''Tsusimskoye srazheniye''), also known in Japan as the , was the final naval battle of the Russo-Japanese War, fought on 27–28 May 1905 in the Tsushima Strait. A devastating defeat for the Imperial Russian Navy, the ...

in 1905.

From 1949 to 1953, Nimitz served as UN-appointed plebiscite administrator for Jammu and Kashmir. His proposed role as administrator was accepted by Pakistan but rejected by India.

Nimitz became a member of the Bohemian Club of San Francisco. In 1948, he sponsored a Bohemian dinner in honor of US Army General Mark Clark, known for his campaigns in North Africa and Italy.

Nimitz served from 1948 to 1956 as a regent of the University of California

The University of California (UC) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university, research university system in the U.S. state of California. Headquartered in Oakland, California, Oakland, the system is co ...

, where he had formerly been a faculty member as a professor of naval science for the Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps

The Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps (NROTC) program is a college-based, commissioned officer training program of the United States Navy and the United States Marine Corps.

Origins

A pilot Naval Reserve unit was established in September 1924 ...

program. Nimitz was honored on 17 October 1964, by the University of California on Nimitz Day.

Personal life

University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California), is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Berkeley, California, United States. Founded in 1868 and named after t ...

, in 1934,Potter. pp. 158–59. became a music librarian with the Washington D.C. Public Library, and married US Navy Commander James Thomas Lay (1909–2001), from St. Clair, Missouri, in Chester and Catherine's suite at the Fairfax Hotel in Washington, D.C., on 9 March 1945. She had met Lay in the summer of 1934 while visiting her parents in Southeast Asia.

Chester Nimitz Jr. graduated from the US Naval Academy in 1936 and served as a submariner in the Navy until his retirement in 1957, reaching the (post-retirement) rank of rear admiral; he served as chairman of PerkinElmer

PerkinElmer, Inc., previously styled Perkin-Elmer, is an American global corporation that was founded in 1937 and originally focused on precision optics. Over the years it went into and out of several different businesses via acquisitions and di ...

from 1969 to 1980.

Anna Elizabeth ("Nancy") Nimitz was an expert on the Soviet economy

The economy of the Soviet Union was based on state ownership of the means of production, collective farming, and industrial manufacturing. An administrative-command system managed a distinctive form of central planning. The Soviet economy ...

at the RAND Corporation

The RAND Corporation, doing business as RAND, is an American nonprofit global policy think tank, research institute, and public sector consulting firm. RAND engages in research and development (R&D) in several fields and industries. Since the ...

from 1952 until her retirement in the 1980s.

Sister Mary Aquinas (Nimitz) joined thDominican Sisters of San Rafael

working at the

Dominican University of California

Dominican University of California is a private university in San Rafael, California, United States. It was founded in 1890 as Dominican College by the Dominican Sisters of San Rafael. It is one of the oldest universities in California.

Dominic ...

. She taught biology for 16 years and was academic dean for 11 years, acting president for one year, and vice president for institutional research for 13 years before becoming the university's emergency preparedness coordinator. She held this job until her death, due to cancer, on 27 February 2006.

Nimitz was also a Freemason

Freemasonry (sometimes spelled Free-Masonry) consists of fraternal groups that trace their origins to the medieval guilds of stonemasons. Freemasonry is the oldest secular fraternity in the world and among the oldest still-existing organizati ...

.

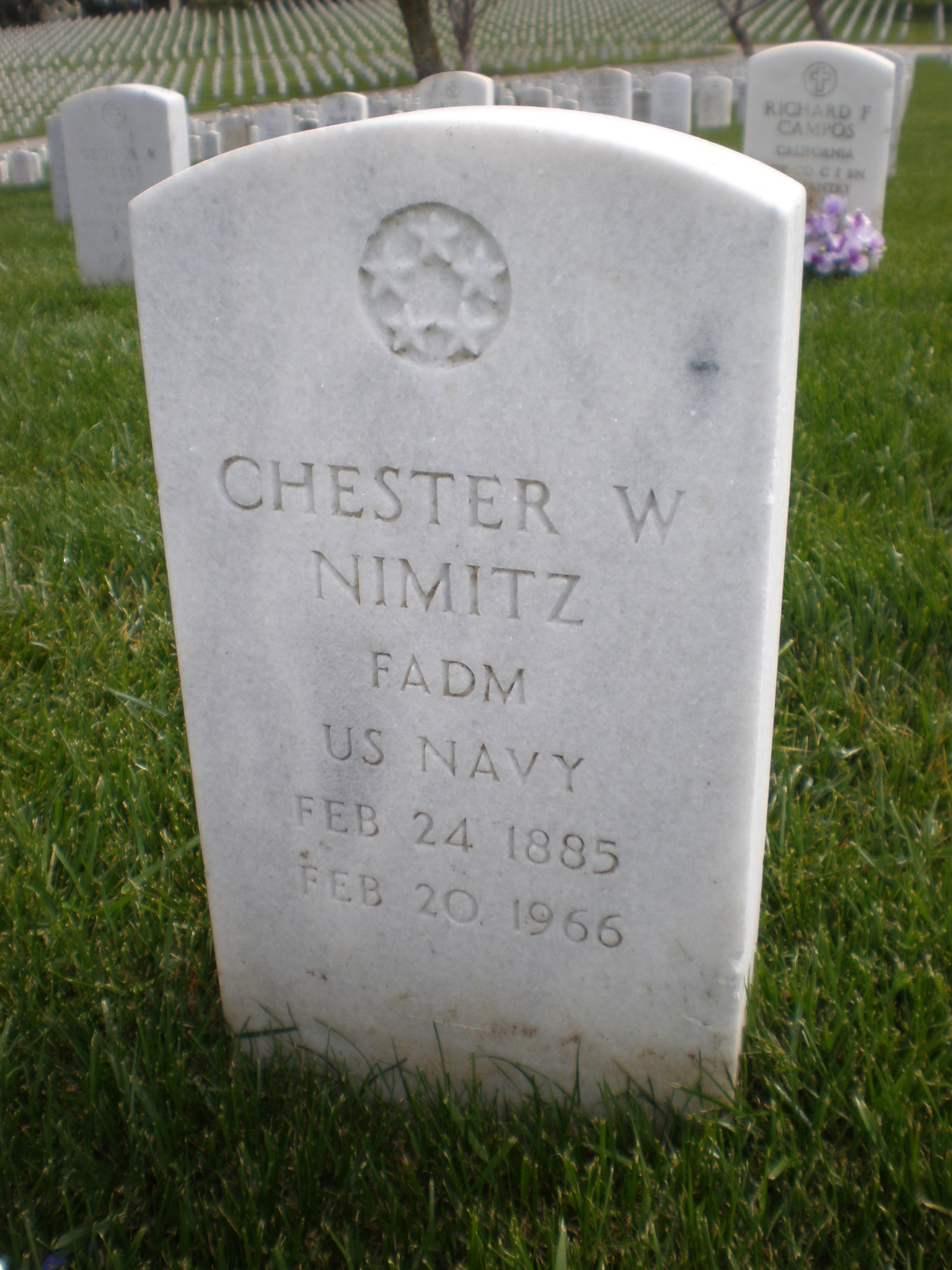

Death

In late 1965, Nimitz suffered a stroke, complicated bypneumonia

Pneumonia is an Inflammation, inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as Pulmonary alveolus, alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of Cough#Classification, productive or dry cough, ches ...

. In January 1966, he left the US Naval Hospital (Oak Knoll) in Oakland

Oakland is a city in the East Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area in the U.S. state of California. It is the county seat and most populous city in Alameda County, with a population of 440,646 in 2020. A major West Coast port, Oakland is ...

to return home to his naval quarters. He died at home on the evening of 20 February at Quarters One on Yerba Buena Island

Yerba Buena Island ( Spanish: ''Isla Yerba Buena'') sits in San Francisco Bay within the borders of the City and County of San Francisco. The Yerba Buena Tunnel runs through its center and connects the western and eastern spans of the San Fran ...

in San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay (Chochenyo language, Chochenyo: 'ommu) is a large tidal estuary in the United States, U.S. state of California, and gives its name to the San Francisco Bay Area. It is dominated by the cities of San Francisco, California, San ...

, four days before his 81st birthday. His funeral on 24 February – what would have been his 81st birthday – was at the chapel of adjacent Naval Station Treasure Island, and Nimitz was buried with full military honors at Golden Gate National Cemetery

Golden Gate National Cemetery is a United States national cemetery in California, located in the city of San Bruno, California, San Bruno, south of San Francisco. Because of the name and location, it is frequently confused with San Francisco ...

in San Bruno.Potter. – p.472. He lies alongside his wife and his lifelong friends Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, Admiral Richmond K. Turner, and Admiral Charles A. Lockwood and their wives, an arrangement made by all of them while living.

Dates of rank

:

United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (USNA, Navy, or Annapolis) is a United States Service academies, federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as United States Secre ...

Midshipman

A midshipman is an officer of the lowest Military rank#Subordinate/student officer, rank in the Royal Navy, United States Navy, and many Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth navies. Commonwealth countries which use the rank include Royal Cana ...

– January 1905

* Nimitz never held the rank of lieutenant junior grade, as he was appointed a full lieutenant after three years of service as an ensign. For administrative reasons, Nimitz's naval record states that he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant junior grade and lieutenant on the same day.

* Nimitz was promoted directly from captain to rear admiral. During Nimitz's service, there was only one rank of rear admiral

Rear admiral is a flag officer rank used by English-speaking navies. In most European navies, the equivalent rank is called counter admiral.

Rear admiral is usually immediately senior to commodore and immediately below vice admiral. It is ...

, without the later distinction between upper and lower half, nor did the rank of commodore exist when Nimitz was at that stage of his career.

* By presidential appointment, he skipped the rank of vice admiral

Vice admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, usually equivalent to lieutenant general and air marshal. A vice admiral is typically senior to a rear admiral and junior to an admiral.

Australia

In the Royal Australian Navy, the rank of Vice ...

and became an admiral in December 1941.

* Nimitz's rank of fleet admiral

An admiral of the fleet or shortened to fleet admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, usually equivalent to field marshal and marshal of the air force. An admiral of the fleet is typically senior to an admiral.

It is also a generic ter ...

was made permanent in the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

on 13 May 1946, a lifetime appointment.

Decorations and awards

United States awards

Foreign awards

Orders

Decorations

Service medals

Memorials and legacy

Fredericksburg, Texas

Fredericksburg () is a city in and the county seat of Gillespie County, Texas, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 Census, this city had a population of 10,875.

Fredericksburg was founded in 1846 and named after Prince Frede ...

* The Nimitz Freeway ( Interstate 880) – from Oakland

Oakland is a city in the East Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area in the U.S. state of California. It is the county seat and most populous city in Alameda County, with a population of 440,646 in 2020. A major West Coast port, Oakland is ...

to San Jose, California

San Jose, officially the City of San José ( ; ), is a cultural, commercial, and political center within Silicon Valley and the San Francisco Bay Area. With a city population of 997,368 and a metropolitan area population of 1.95 million, it is ...

, in the San Francisco Bay Area

The San Francisco Bay Area, commonly known as the Bay Area, is a List of regions of California, region of California surrounding and including San Francisco Bay, and anchored by the cities of Oakland, San Francisco, and San Jose, California, S ...

* Nimitz Glacier in Antarctica for his service during Operation Highjump

Operation HIGHJUMP, officially titled The United States Navy Antarctic Developments Program, 1946–1947, (also called Task Force 68), was a United States Navy (USN) operation to establish the Antarctic research base Little America (exploration b ...

as the CNO

* Nimitz Boulevard – a major thoroughfare in the Point Loma

Point Loma ( Spanish: ''Punta de la Loma'', meaning "Hill Point"; Kumeyaay: ''Amat Kunyily'', meaning "Black Earth") is a seaside community in San Diego, California, United States. Geographically it is a hilly peninsula that is bordered on the ...

Neighborhood of San Diego

San Diego ( , ) is a city on the Pacific coast of Southern California, adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a population of over 1.4 million, it is the List of United States cities by population, eighth-most populous city in t ...

* Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz Gate – Main gate for Naval Base San Diego San Diego

San Diego ( , ) is a city on the Pacific coast of Southern California, adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a population of over 1.4 million, it is the List of United States cities by population, eighth-most populous city in t ...

*Nimitz BEQ at the Naval Nuclear Power Training Command in Goose Creek, South Carolina

* Camp Nimitz, a recruit camp constructed in 1955 at Naval Training Center San Diego

* Nimitz Highway – Hawaii Route 92 located in Honolulu, Hawaii

Honolulu ( ; ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Hawaii, located in the Pacific Ocean. It is the county seat of the Consolidated city-county, consolidated City and County of Honol ...

near the Daniel K. Inouye International Airport

* The Nimitz Library, the main library at the US Naval Academy, Annapolis

Annapolis ( ) is the capital of the U.S. state of Maryland. It is the county seat of Anne Arundel County and its only incorporated city. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east o ...

, Maryland

* Nimitz Drive, in the Admiral Heights neighborhood of Annapolis

Annapolis ( ) is the capital of the U.S. state of Maryland. It is the county seat of Anne Arundel County and its only incorporated city. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east o ...

, Maryland

* Nimitz Lane, Willingboro, New Jersey

* Callaghan Hall (the Naval and Air Force ROTC building at UC Berkeley) containing the Nimitz Library (was gutted by arson in 1985)

* The town of Nimitz in Summers County, West Virginia

West Virginia is a mountainous U.S. state, state in the Southern United States, Southern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States.The United States Census Bureau, Census Bureau and the Association of American ...

* The summit on Guam

Guam ( ; ) is an island that is an Territories of the United States, organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. Guam's capital is Hagåtña, Guam, Hagåtña, and the most ...

where Chester Nimitz relocated his Pacific Fleet headquarters, and where the current Commander US Naval Forces Marianas (ComNavMar) resides, is called Nimitz Hill Nimitz Hill may refer to:

* Nimitz Hill (geographic feature), a hill in Asan, Guam surrounded by the Nimitz Hill Annex census-designated place

* Nimitz Hill (CDP), a census-designated place in Piti, Guam located adjacent to the Nimitz Hill Annex CDP ...

* Nimitz Park, a recreational area located at United States Fleet Activities Sasebo, Japan

* The Nimitz Trail in Tilden Park in Berkeley, California

Berkeley ( ) is a city on the eastern shore of San Francisco Bay in northern Alameda County, California, United States. It is named after the 18th-century Anglo-Irish bishop and philosopher George Berkeley. It borders the cities of Oakland, Cali ...

* The Main Gate at Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the Reci ...

is called Nimitz Gate

* Admiral Nimitz Circle – located in Fair Park

Fair Park is a recreational and educational complex in Dallas, Dallas, Texas, United States, located immediately east of Downtown Dallas, downtown. The area is registered as a Dallas Landmark and National Historic Landmark; many of the building ...

, Dallas, Texas

Dallas () is a city in the U.S. state of Texas and the most populous city in the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex, the List of Texas metropolitan areas, most populous metropolitan area in Texas and the Metropolitan statistical area, fourth-most ...

* Chester Nimitz Oriental Garden Waltz performed by Austin Lounge Lizards

* Admiral Nimitz Fanfare composed by John Steven Lasher (2014)

* Admiral Nimitz March composed by John Steven Lasher (2014)

* The Nimitz Building, Raytheon

Raytheon is a business unit of RTX Corporation and is a major U.S. defense contractor and industrial corporation with manufacturing concentrations in weapons and military and commercial electronics. Founded in 1922, it merged in 2020 with Unite ...

Company site headquarters, Portsmouth, Rhode Island

Portsmouth is a town in Newport County, Rhode Island, United States. The population was 17,871 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 U.S. census. Portsmouth is the second-oldest municipality in Rhode Island, after Providence Plantations, Provide ...

* Nimitz Road in Diego Garcia, British Indian Ocean Territory, is named in his honor.

* Nimitz Place part of Havemeyer Park located in Old Greenwich, Connecticut, was named in his honor along with many other World War II military personnel.

* Nimitz Hall is the Officer Candidate School

An officer candidate school (OCS) is a military school which trains civilians and Enlisted rank, enlisted personnel in order for them to gain a Commission (document), commission as Commissioned officer, officers in the armed forces of a country. H ...

barracks

Barracks are buildings used to accommodate military personnel and quasi-military personnel such as police. The English word originates from the 17th century via French and Italian from an old Spanish word 'soldier's tent', but today barracks ar ...

of Naval Station Newport

Naval Station Newport (NAVSTA Newport) is a United States Navy base located in the city of Newport, Rhode Island, Newport and the town of Middletown, Rhode Island. Naval Station Newport is home to the Naval War College and the Naval Justice Scho ...

, Newport, Rhode Island

Newport is a seaside city on Aquidneck Island in Rhode Island, United States. It is located in Narragansett Bay, approximately southeast of Providence, Rhode Island, Providence, south of Fall River, Massachusetts, south of Boston, and nort ...

. The barracks was dedicated March 15, 2013.

* Nimitz-McArthur Building, Headquarters US Pacific Command

* Nimitz Statue, designed by Armando Hinojosa of Laredo, is located at the entrance to SeaWorld in San Antonio, Texas

San Antonio ( ; Spanish for "Anthony of Padua, Saint Anthony") is a city in the U.S. state of Texas and the most populous city in Greater San Antonio. San Antonio is the List of Texas metropolitan areas, third-largest metropolitan area in Texa ...

.

* Nimitz Drive in Grants, New Mexico

Grants is a city in Cibola County, New Mexico, United States. It is located about west of Albuquerque. The population was 9,163 at the 2020 Census. It is the county seat of Cibola County.

Grants is located along the Trails of the Ancients B ...

Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz Statue

commissioned by the Naval Order of the United States, is situated near the bow of the

memorial

A memorial is an object or place which serves as a focus for the memory or the commemoration of something, usually an influential, deceased person or a historical, tragic event. Popular forms of memorials include landmark objects such as home ...

on Ford Island

Ford Island () is an islet in the center of Pearl Harbor, Oahu, in the U.S. state of Hawaii. It has been known as Rabbit Island, Marín's Island, and Little Goats Island; its native Hawaiian name is ''Mokuumeume''. The island had an area of ...

, facing the memorial

A memorial is an object or place which serves as a focus for the memory or the commemoration of something, usually an influential, deceased person or a historical, tragic event. Popular forms of memorials include landmark objects such as home ...

. The statue was dedicated 2 September 2013.

* Nimitz Beach Park, Agat, Guam

* Nimitz Drive, Purdue University

Purdue University is a Public university#United States, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in West Lafayette, Indiana, United States, and the flagship campus of the Purdue University system. The university was founded ...

, West Lafayette, Indiana

West Lafayette ( ) is a city in Wabash and Tippecanoe Townships, Tippecanoe County, Indiana, United States, approximately northwest of the state capital of Indianapolis and southeast of Chicago. West Lafayette is directly across the Wabash ...

* Nimitz Avenue, Mare Island

Mare Island (Spanish language, Spanish: ''Isla de la Yegua'') is a peninsula in the United States in the city of Vallejo, California, about northeast of San Francisco. The Napa River forms its eastern side as it enters the Carquinez Strait junc ...

, Vallejo California

* Chester W. Nimitz Street, Bakersfield, California

Bakersfield is a city in and the county seat of Kern County, California, United States. The city covers about near the southern end of the San Joaquin Valley, which is located in the Central Valley region.

Bakersfield's population as of th ...

* Nimitz Road, Dover, Delaware

Dover ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and the List of municipalities in Delaware, second-most populous city of the U.S. state of Delaware. It is also the county seat of Kent County, Delaware, Kent County and the princ ...

* Nimitz Street, College Station, Texas

College Station is a city in Brazos County, Texas, United States, situated in East-Central Texas in the Brazos Valley, towards the eastern edge of the region known as the Texas Triangle. It is northwest of Houston and east-northeast of Austin, ...

Schools

* Nimitz High School, (Harris County, Texas) * Nimitz High School, Irving, Texas. * Chester W. Nimitz Middle School,Odessa

ODESSA is an American codename (from the German language, German: ''Organisation der ehemaligen SS-Angehörigen'', meaning: Organization of Former SS Members) coined in 1946 to cover Ratlines (World War II aftermath), Nazi underground escape-pl ...

, Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

* Chester W. Nimitz Middle School, Huntington Park, California

* Nimitz Middle School, San Antonio

San Antonio ( ; Spanish for " Saint Anthony") is a city in the U.S. state of Texas and the most populous city in Greater San Antonio. San Antonio is the third-largest metropolitan area in Texas and the 24th-largest metropolitan area in the ...

, Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

* Chester Nimitz Middle School, Tulsa Oklahoma (Now Closed)

* Nimitz Elementary School, Sunnyvale, California

Sunnyvale () is a city located in the Santa Clara Valley in northwestern Santa Clara County, California, United States.

Sunnyvale lies along the historic El Camino Real (California), El Camino Real and U.S. Route 101 in California, Highway 1 ...

* Chester W. Nimitz Elementary School, Honolulu, Hawaii

Honolulu ( ; ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Hawaii, located in the Pacific Ocean. It is the county seat of the Consolidated city-county, consolidated City and County of Honol ...

* Nimitz Elementary School, Kerrville, Texas

Kerrville is a city in Texas, and the county seat of Kerr County, Texas, United States. The population of Kerrville was 24,278 at the 2020 census. Kerrville is named after James Kerr, a major in the Texas Revolution, and friend of settler-fo ...

Depictions in media

* in the 1965 war film "In Harm's Way," actor Henry Fonda plays the character "CINCPAC II," who might be based on Nimitz. * In the 1976 war film '' Midway,'' Nimitz is portrayed by actorHenry Fonda

Henry Jaynes Fonda (May 16, 1905 – August 12, 1982) was an American actor whose career spanned five decades on Broadway theatre, Broadway and in Hollywood. On screen and stage, he often portrayed characters who embodied an everyman image.

Bo ...

.

* In the 2019 war film '' Midway,'' Nimitz is portrayed by actor Woody Harrelson

Woodrow Tracy Harrelson (born July 23, 1961) is an American actor. He first became known for his role as bartender Woody Boyd on the NBC sitcom ''Cheers'' (1985–1993), for which he won a Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Supporting Actor in ...

.

See also

* Henry Arnold Karo—see hand-written inscription on photo given to Adm. Karo *Admiral of the Navy

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in many navy, navies. In the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general officer, general in the army or the air force. Admiral is r ...

References

:Bibliography

* * * "Some Thoughts to Live By", Chester W. Nimitz with Andrew Hamilton, , reprinted from ''Boys' Life

''Scout Life'' (formerly ''Boys' Life'') is the monthly magazine of the Boy Scouts of America (BSA). Its target readers are children between the ages of 6 and 18. The magazine‘s headquarters are in Irving, Texas.

''Scout Life'' is published ...

'', 1966.

* Potter, E. B. ''Nimitz''. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1976. .

* Potter, E. B., and Chester W. Nimitz. ''Sea Power''. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1960. .

*

*

*

* Lilly, Michael A., Capt., USN (Ret), "Nimitz at Ease", Stairway Press, 2019. ISBN 1949267261.

Further reading

* * * Knortz, James A"The Strategic Leadership of Admiral Chester W. Nimitz"

. (Army War College Carlisle Barracks, 2012). * * Stone, Christopher B. "Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz: Leadership Forged Through Adversity" (PhD dissertation, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 2018)

Excerpt

* Wildenberg, Thomas

"Chester Nimitz and the development of fueling at sea"

''Naval War College Review'' 46.4 (1993): 52–62.

1944 interview with Admiral Nimitz

from '' Yank''.

External links

* *National Museum of the Pacific War

Nimitz State Historic Site

in Fredericksburg, Texas

"The Navy's Part in the World War". (26 November 1945)

A speech by Nimitz from th

Commonwealth Club of California Records

at th

Hoover Institution Archives

*

Guide to the Chester W. Nimitz Papers, 1941–1966 MS 236

held by Special Collections & Archives, Nimitz Library at the United States Naval Academy {{DEFAULTSORT:Nimitz, Chester 1885 births 1966 deaths American five-star officers Battle of Midway American people of German descent Burials at Golden Gate National Cemetery Chiefs of Naval Operations Military personnel from Texas German-American culture in Texas Grand Crosses of the Order of George I High commissioners of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands Naval War College alumni People from Fredericksburg, Texas People from Kerrville, Texas United States Naval Academy alumni United States Navy admirals United States Navy World War II admirals United States Navy personnel who were court-martialed Honorary Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath Knights Grand Cross of the Military Order of Savoy Knights Grand Cross of the Order of Orange-Nassau Grand Crosses of the Order of the Crown (Belgium) Officers of the Legion of Honour American recipients of the Croix de guerre (Belgium) Recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (US Army) Recipients of the Order of Naval Merit (Brazil) Recipients of the Order of the Liberator General San Martin Recipients of the Order of the Sacred Tripod Recipients of the Navy Distinguished Service Medal People from Clinton Hill, Brooklyn United States Navy personnel of World War I