Charles Lyell on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known today for his association with

In 1832, Lyell married Mary Horner in Bonn, daughter of Leonard Horner (1785–1864), also associated with the

In 1832, Lyell married Mary Horner in Bonn, daughter of Leonard Horner (1785–1864), also associated with the

Throughout his life, Lyell kept a remarkable series of nearly three hundred manuscript notebooks and diaries. These span Lyell's long scientific career (1825–1874), and offer an unrivalled insight into personal influences, field observations, thoughts and relationships. They were acquired in 2019 by the

Throughout his life, Lyell kept a remarkable series of nearly three hundred manuscript notebooks and diaries. These span Lyell's long scientific career (1825–1874), and offer an unrivalled insight into personal influences, field observations, thoughts and relationships. They were acquired in 2019 by the

dedicated website

'' Although Darwin discussed evolutionary ideas with him from 1842, Lyell continued to reject evolution in each of the first nine editions of the ''Principles''. He encouraged Darwin to publish, and following the 1859 publication of ''

Although Darwin discussed evolutionary ideas with him from 1842, Lyell continued to reject evolution in each of the first nine editions of the ''Principles''. He encouraged Darwin to publish, and following the 1859 publication of ''

Before Lyell's work, phenomena's such as earthquakes were understood by the destruction that they brought. One of the contributions that Lyell made in ''Principles'' was to explain the cause of earthquakes. Lyell, in contrast, focused on more recent earthquakes (150 yrs), evidenced by surface irregularities such as faults, fissures, stratigraphic displacements and depressions.

Lyell's work on volcanoes focused largely on

Before Lyell's work, phenomena's such as earthquakes were understood by the destruction that they brought. One of the contributions that Lyell made in ''Principles'' was to explain the cause of earthquakes. Lyell, in contrast, focused on more recent earthquakes (150 yrs), evidenced by surface irregularities such as faults, fissures, stratigraphic displacements and depressions.

Lyell's work on volcanoes focused largely on

Lyell initially accepted the conventional view of other men of science, that the fossil record indicated a directional geohistory in which species went extinct. Around 1826, when he was on circuit, he read

Lyell initially accepted the conventional view of other men of science, that the fossil record indicated a directional geohistory in which species went extinct. Around 1826, when he was on circuit, he read  If I had stated... the possibility of the introduction or origination of fresh species being a natural, in contradistinction to a miraculous process, I should have raised a host of prejudices against me, which are unfortunately opposed at every step to any philosopher who attempts to address the public on these mysterious subjects...

As a result of his letters and, no doubt, personal conversations, Huxley and

If I had stated... the possibility of the introduction or origination of fresh species being a natural, in contradistinction to a miraculous process, I should have raised a host of prejudices against me, which are unfortunately opposed at every step to any philosopher who attempts to address the public on these mysterious subjects...

As a result of his letters and, no doubt, personal conversations, Huxley and  Quite strong remarks: no doubt Darwin resented Lyell's repeated suggestion that he owed a lot to

Quite strong remarks: no doubt Darwin resented Lyell's repeated suggestion that he owed a lot to

* Lyell Canyon in Yosemite National Park

* Lyell Fork, one of two large forks of the Tuolumne River

* Lyell Land (Greenland)

*

* Lyell Canyon in Yosemite National Park

* Lyell Fork, one of two large forks of the Tuolumne River

* Lyell Land (Greenland)

*

Elements of Geology

' 1 vol. 1st edition, July 1838 (John Murray, London) * ''Elements of Geology'' 2 vols. 2nd edition, July 1841 * ''Elements of Geology (Manual of Elementary Geology)'' 1 vol. 3rd edition, Jan. 1851 * ''Elements of Geology (Manual of Elementary Geology)'' 1 vol. 4th edition, Jan. 1852 * ''Elements of Geology (Manual of Elementary Geology)'' 1 vol. 5th edition, 1855 * ''Elements of Geology'' 6th edition, 1865

''Elements of Geology, The Student's Series'', 1871

Website showcasing Lyell's comprehensive archive

held at the University of Edinburgh * * * * * *

at ESP.

''Principles of Geology''

(7th edition, 1847) from

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

and as the author of ''Principles of Geology

''Principles of Geology: Being an Attempt to Explain the Former Changes of the Earth's Surface, by Reference to Causes Now in Operation'' is a book by the Scottish geologist Charles Lyell that was first published in 3 volumes from 1830 to 1833. ...

'' (1830–33), which presented to a wide public audience the idea that the earth was shaped by the same natural processes still in operation today, operating at similar intensities. The philosopher William Whewell

William Whewell ( ; 24 May 17946 March 1866) was an English polymath. He was Master of Trinity College, Cambridge. In his time as a student there, he achieved distinction in both poetry and mathematics.

The breadth of Whewell's endeavours is ...

dubbed this gradualistic view "uniformitarianism

Uniformitarianism, also known as the Doctrine of Uniformity or the Uniformitarian Principle, is the assumption that the same natural laws and processes that operate in our present-day scientific observations have always operated in the universe in ...

" and contrasted it with catastrophism

In geology, catastrophism is the theory that the Earth has largely been shaped by sudden, short-lived, violent events, possibly worldwide in scope.

This contrasts with uniformitarianism (sometimes called gradualism), according to which slow inc ...

, which had been championed by Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, baron Cuvier (23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier (; ), was a French natural history, naturalist and zoology, zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuv ...

and was better accepted in Europe. The combination of evidence and eloquence in ''Principles'' convinced a wide range of readers of the significance of " deep time" for understanding the earth and environment.

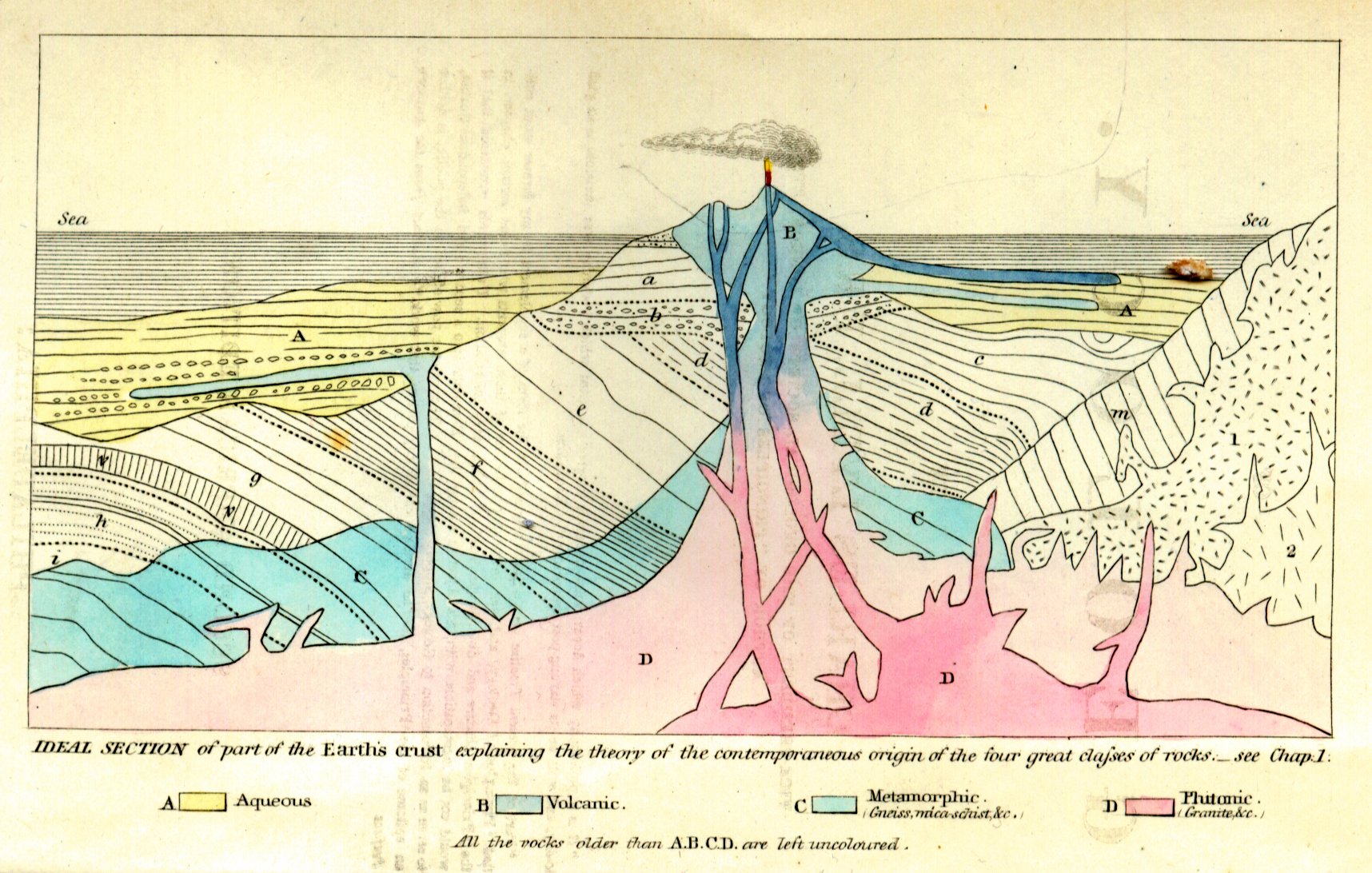

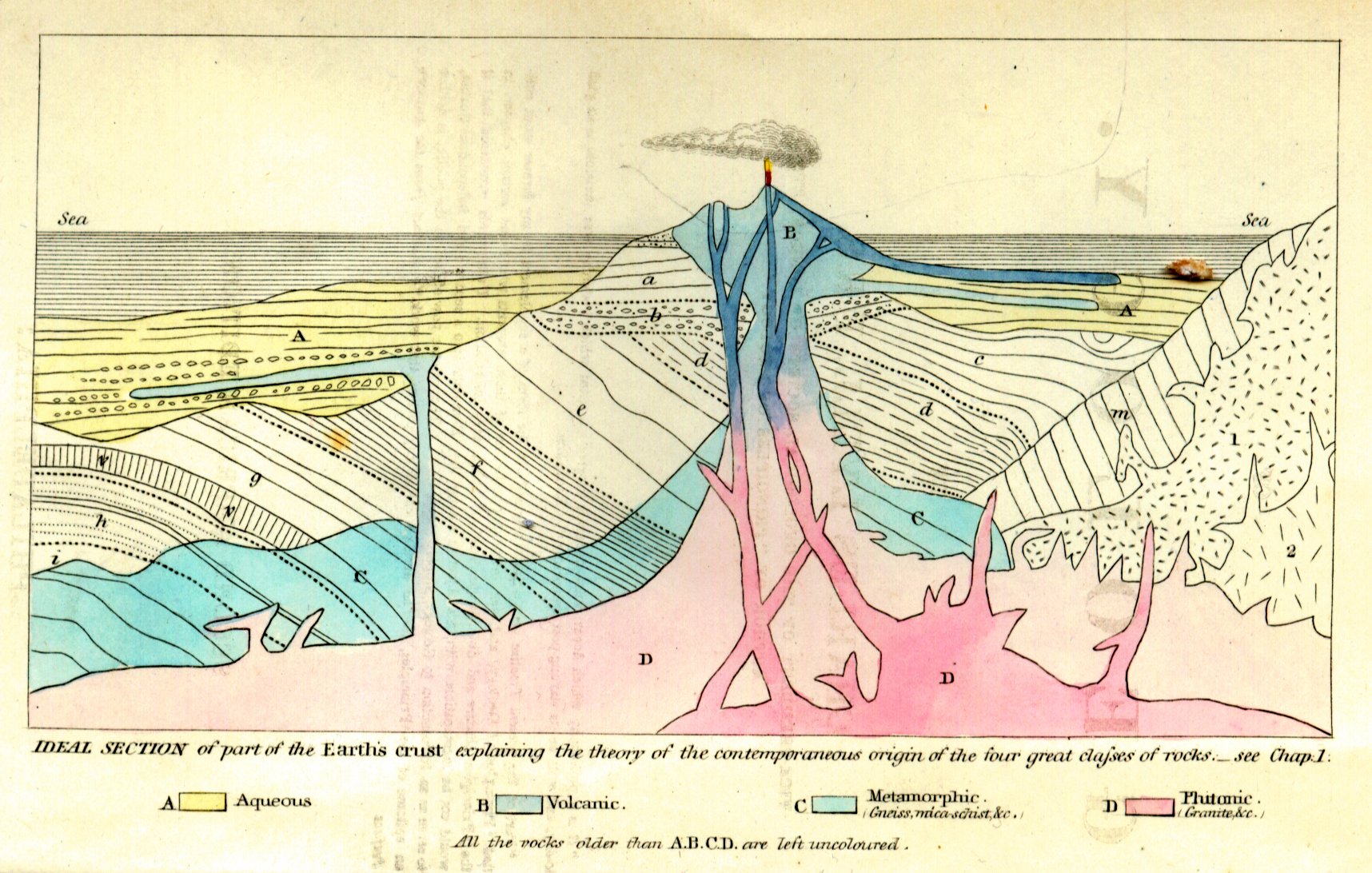

Lyell's scientific contributions included a pioneering explanation of climate change, in which shifting boundaries between oceans and continents could be used to explain long-term variations in temperature and rainfall. Lyell also gave influential explanations of earthquakes and developed the theory of gradual "backed up-building" of volcano

A volcano is commonly defined as a vent or fissure in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Earth, volcanoes are most oft ...

es. In stratigraphy

Stratigraphy is a branch of geology concerned with the study of rock layers (strata) and layering (stratification). It is primarily used in the study of sedimentary and layered volcanic rocks.

Stratigraphy has three related subfields: lithost ...

his division of the Tertiary

Tertiary (from Latin, meaning 'third' or 'of the third degree/order..') may refer to:

* Tertiary period, an obsolete geologic period spanning from 66 to 2.6 million years ago

* Tertiary (chemistry), a term describing bonding patterns in organic ch ...

period into the Pliocene

The Pliocene ( ; also Pleiocene) is the epoch (geology), epoch in the geologic time scale that extends from 5.33 to 2.58Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first epoch (geology), geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and mea ...

, and Eocene

The Eocene ( ) is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (Ma). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene'' comes ...

was highly influential. He incorrectly conjectured that icebergs were the impetus behind the transport of glacial erratic

A glacial erratic is a glacially deposited rock (geology), rock differing from the type of country rock (geology), rock native to the area in which it rests. Erratics, which take their name from the Latin word ' ("to wander"), are carried by gla ...

s, and that silty loess

A loess (, ; from ) is a clastic rock, clastic, predominantly silt-sized sediment that is formed by the accumulation of wind-blown dust. Ten percent of Earth's land area is covered by loesses or similar deposition (geology), deposits.

A loess ...

deposits might have settled out of flood waters. His creation of a separate period for human history, entitled the 'Recent', is widely cited as providing the foundations for the modern discussion of the Anthropocene

''Anthropocene'' is a term that has been used to refer to the period of time during which human impact on the environment, humanity has become a planetary force of change. It appears in scientific and social discourse, especially with respect to ...

.

Building on the innovative work of James Hutton

James Hutton (; 3 June Old Style and New Style dates, O.S. 1726 – 26 March 1797) was a Scottish geologist, Agricultural science, agriculturalist, chemist, chemical manufacturer, Natural history, naturalist and physician. Often referred to a ...

and his follower John Playfair, Lyell favoured an indefinitely long age for the earth, despite evidence suggesting an old but finite age. He was a close friend of Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

, and contributed significantly to Darwin's thinking on the processes involved in evolution. As Darwin wrote in ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life'')The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by M ...

'', "He who can read Sir Charles Lyell's grand work on the Principles of Geology, which the future historian will recognise as having produced a revolution in natural science, yet does not admit how incomprehensibly vast have been the past periods of time, may at once close this volume." Lyell helped to arrange the simultaneous publication in 1858 of papers by Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace

Alfred Russel Wallace (8 January 1823 – 7 November 1913) was an English naturalist, explorer, geographer, anthropologist, biologist and illustrator. He independently conceived the theory of evolution through natural selection; his 1858 pap ...

on natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the Heredity, heritable traits characteristic of a population over generation ...

, despite his personal religious qualms about the theory. He later published evidence from geology of the time man had existed on the earth.

Biography

Lyell was born into a wealthy family, on 14 November 1797, at the family's estate house, Kinnordy House, nearKirriemuir

Kirriemuir ( , ; ), sometimes called Kirrie or the ''Wee Red Toon'', is a burgh in Angus, Scotland, United Kingdom.

The playwright J. M. Barrie was born and buried here and a statue of Peter Pan is in the town square.

History

Some of th ...

in Forfarshire. He was the eldest of ten children. Lyell's father, also named Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known today for his association with Charles ...

, was noted as a translator and scholar of Dante

Dante Alighieri (; most likely baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri; – September 14, 1321), widely known mononymously as Dante, was an Italian Italian poetry, poet, writer, and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called ...

. An accomplished botanist, it was he who first exposed his son to the study of nature. Lyell's grandfather, also Charles Lyell, had made the family fortune supplying the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

at Montrose, enabling him to buy Kinnordy House.

The family seat is located in Strathmore, near the Highland Boundary Fault

The Highland Boundary Fault is a major fault zone that traverses Scotland from Arran and Helensburgh on the west coast to Stonehaven in the east. It separates two different geological terranes which give rise to two distinct physiographic ter ...

. Round the house, in the strath, is good farmland, but within a short distance to the north-west, on the other side of the fault, are the Grampian Mountains

The Grampian Mountains () is one of the three major mountain ranges in Scotland, that together occupy about half of Scotland. The other two ranges are the Northwest Highlands and the Southern Uplands. The Grampian range extends northeast to so ...

in the Highlands. His family's second country home was in a completely different geological and ecological area: he spent much of his childhood at Bartley Lodge in the New Forest

The New Forest is one of the largest remaining tracts of unenclosed pasture land, heathland and forest in Southern England, covering southwest Hampshire and southeast Wiltshire. It was proclaimed a royal forest by William the Conqueror, featu ...

, in Hampshire in southern England.

Lyell entered Exeter College, Oxford

Exeter College (in full: The Rector and Scholars of Exeter College in the University of Oxford) is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England, and the fourth-oldest college of the university.

The college was founde ...

, in 1816, and attended William Buckland

William Buckland Doctor of Divinity, DD, Royal Society, FRS (12 March 1784 – 14 August 1856) was an English theologian, geologist and paleontology, palaeontologist.

His work in the early 1820s proved that Kirkdale Cave in North Yorkshire h ...

's geological lectures. He graduated with a BA Hons. second class degree in classics, in December 1819, and gained his M.A. 1821. After graduation he took up law as a profession, entering Lincoln's Inn

The Honourable Society of Lincoln's Inn, commonly known as Lincoln's Inn, is one of the four Inns of Court (professional associations for Barrister, barristers and judges) in London. To be called to the bar in order to practise as a barrister ...

in 1820. He completed a circuit through rural England, where he could observe geological phenomena. In 1821 he attended Robert Jameson

image:Robert Jameson.jpg, Robert Jameson

Robert Jameson Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS FRSE (11 July 1774 – 19 April 1854) was a Scottish natural history, naturalist and mineralogist.

As Regius Professor of Natural History at the Univers ...

's lectures in Edinburgh, and visited Gideon Mantell

Gideon Algernon Mantell Membership of the Royal College of Surgeons, MRCS Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS (3 February 1790 – 10 November 1852) was an English obstetrician, geologist and paleontology, palaeontologist. His attempts to reconstr ...

at Lewes

Lewes () is the county town of East Sussex, England. The town is the administrative centre of the wider Lewes (district), district of the same name. It lies on the River Ouse, Sussex, River Ouse at the point where the river cuts through the Sou ...

, in Sussex

Sussex (Help:IPA/English, /ˈsʌsɪks/; from the Old English ''Sūþseaxe''; lit. 'South Saxons'; 'Sussex') is an area within South East England that was historically a kingdom of Sussex, kingdom and, later, a Historic counties of England, ...

. In 1823 he was elected joint secretary of the Geological Society

The Geological Society of London, known commonly as the Geological Society, is a learned society based in the United Kingdom. It is the oldest national geological society in the world and the largest in Europe, with more than 12,000 Fellows.

Fe ...

. As his eyesight began to deteriorate, he turned to geology as a full-time profession. His first paper, "On a recent formation of freshwater limestone in Forfarshire", was presented in 1826. By 1827, he had abandoned law and embarked on a geological career that would result in fame and the general acceptance of uniformitarianism, a working out of the ideas proposed by James Hutton

James Hutton (; 3 June Old Style and New Style dates, O.S. 1726 – 26 March 1797) was a Scottish geologist, Agricultural science, agriculturalist, chemist, chemical manufacturer, Natural history, naturalist and physician. Often referred to a ...

a few decades earlier.

In 1832, Lyell married Mary Horner in Bonn, daughter of Leonard Horner (1785–1864), also associated with the

In 1832, Lyell married Mary Horner in Bonn, daughter of Leonard Horner (1785–1864), also associated with the Geological Society of London

The Geological Society of London, known commonly as the Geological Society, is a learned society based in the United Kingdom. It is the oldest national geological society in the world and the largest in Europe, with more than 12,000 Fellows.

Fe ...

. The new couple spent their honeymoon in Switzerland and Italy on a geological tour of the area.

During the 1840s, Lyell travelled to the United States and Canada, and wrote two popular travel-and-geology books: ''Travels in North America'' (1845) and ''A Second Visit to the United States'' (1849). In 1866, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences () is one of the Swedish Royal Academies, royal academies of Sweden. Founded on 2 June 1739, it is an independent, non-governmental scientific organization that takes special responsibility for promoting nat ...

. After the Great Chicago Fire

The Great Chicago Fire was a conflagration that burned in the American city of Chicago, Illinois during October 8–10, 1871. The fire killed approximately 300 people, destroyed roughly of the city including over 17,000 structures, and left mor ...

in 1871, Lyell was one of the first to donate books to help found the Chicago Public Library

The Chicago Public Library (CPL) is the public library system that serves the Chicago, City of Chicago in the U.S. state of Illinois. It consists of 81 locations, including a central library, three regional libraries, and branches distributed thr ...

.

In 1841, Lyell was elected as a member to the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS) is an American scholarly organization and learned society founded in 1743 in Philadelphia that promotes knowledge in the humanities and natural sciences through research, professional meetings, publicat ...

.

Lyell's wife died in 1873, and two years later (in 1875) Lyell himself died as he was revising the twelfth edition of ''Principles''. He is buried in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

where there is a bust to him by William Theed

William Theed (1804 – 9 September 1891), also known as William Theed the younger, was a British sculptor, the son of the sculptor and painter William Theed the elder (1764–1817). He specialised in portraiture, and his services were extensi ...

in the north aisle.

Lyell was knighted ( Kt) in 1848, and later, in 1864, made a baronet ( Bt), which is an hereditary honour. He was awarded the Copley Medal

The Copley Medal is the most prestigious award of the Royal Society of the United Kingdom, conferred "for sustained, outstanding achievements in any field of science". The award alternates between the physical sciences or mathematics and the bio ...

of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

in 1858 and the Wollaston Medal of the Geological Society

The Geological Society of London, known commonly as the Geological Society, is a learned society based in the United Kingdom. It is the oldest national geological society in the world and the largest in Europe, with more than 12,000 Fellows.

Fe ...

in 1866. Mount Lyell, the highest peak in Yosemite National Park

Yosemite National Park ( ) is a List of national parks of the United States, national park of the United States in California. It is bordered on the southeast by Sierra National Forest and on the northwest by Stanislaus National Forest. The p ...

, is named after him; the crater Lyell on the Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It Orbit of the Moon, orbits around Earth at Lunar distance, an average distance of (; about 30 times Earth diameter, Earth's diameter). The Moon rotation, rotates, with a rotation period (lunar ...

and a crater

A crater is a landform consisting of a hole or depression (geology), depression on a planetary surface, usually caused either by an object hitting the surface, or by geological activity on the planet. A crater has classically been described ...

on Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun. It is also known as the "Red Planet", because of its orange-red appearance. Mars is a desert-like rocky planet with a tenuous carbon dioxide () atmosphere. At the average surface level the atmosph ...

were named in his honour; Mount Lyell in western Tasmania, Australia, located in a profitable mining area, bears Lyell's name; and the Lyell Range in north-west Western Australia is named after him as well. In Southwest Nelson in the South Island of New Zealand, the Lyell Range, Lyell River and the gold mining town of Lyell (now only a camping site) were all named after Lyell. Lyall Bay in Wellington, New Zealand was possibly named after Lyell. The jawless fish '' Cephalaspis lyelli'', from the Old Red Sandstone

Old Red Sandstone, abbreviated ORS, is an assemblage of rocks in the North Atlantic region largely of Devonian age. It extends in the east across Great Britain, Ireland and Norway, and in the west along the eastern seaboard of North America. It ...

of southern Scotland, was named by Louis Agassiz

Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz ( ; ) FRS (For) FRSE (May 28, 1807 – December 14, 1873) was a Swiss-born American biologist and geologist who is recognized as a scholar of Earth's natural history.

Spending his early life in Switzerland, he recei ...

in honour of Lyell.

Sir Charles Lyell was buried at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

on 27 February 1875. The pallbearers included T. H. Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley (4 May 1825 – 29 June 1895) was an English biologist and anthropologist who specialized in comparative anatomy. He has become known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution.

The stor ...

, the Rev. W. S. Symonds and Mr John Carrick Moore.

Career and major writings

Lyell had private means, and earned further income as an author. He came from a prosperous family, worked briefly as a lawyer in the 1820s, and held the post of Professor of Geology atKing's College London

King's College London (informally King's or KCL) is a public university, public research university in London, England. King's was established by royal charter in 1829 under the patronage of George IV of the United Kingdom, King George IV ...

in the 1830s. From 1830 onward his books provided both income and fame. Each of his three major books was a work continually in progress. All three went through multiple editions during his lifetime, although many of his friends (such as Darwin) thought the first edition of the ''Principles'' was the best written. Lyell used each edition to incorporate additional material, rearrange existing material, and revisit old conclusions in light of new evidence.

Throughout his life, Lyell kept a remarkable series of nearly three hundred manuscript notebooks and diaries. These span Lyell's long scientific career (1825–1874), and offer an unrivalled insight into personal influences, field observations, thoughts and relationships. They were acquired in 2019 by the

Throughout his life, Lyell kept a remarkable series of nearly three hundred manuscript notebooks and diaries. These span Lyell's long scientific career (1825–1874), and offer an unrivalled insight into personal influences, field observations, thoughts and relationships. They were acquired in 2019 by the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh (, ; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a Public university, public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Founded by the City of Edinburgh Council, town council under th ...

's Heritage Collections, thanks to a fundraising campaign, with many generous individual and institutional donors from the UK and overseas. Highlights include his travels throughout Europe and the United States of America, the drafts of his correspondence with the likes of Charles Darwin, his geological and landscape sketches and his constant gathering of evidence and refinement of his theories. Lyell's collection held at the University of Edinburgh, including digital images of his five series of notebooks, and with links to other Lyell material held elsewhere, is now available on dedicated website

''

Principles of Geology

''Principles of Geology: Being an Attempt to Explain the Former Changes of the Earth's Surface, by Reference to Causes Now in Operation'' is a book by the Scottish geologist Charles Lyell that was first published in 3 volumes from 1830 to 1833. ...

'', Lyell's first book, was also his most famous, most influential, and most important. First published in three volumes in 1830–33, it established Lyell's credentials as an important geological theorist and propounded the doctrine of uniformitarianism

Uniformitarianism, also known as the Doctrine of Uniformity or the Uniformitarian Principle, is the assumption that the same natural laws and processes that operate in our present-day scientific observations have always operated in the universe in ...

. It was a work of synthesis, backed by his own personal observations on his travels.

The central argument in ''Principles'' was that ''the present is the key to the past'' – a concept of the Scottish Enlightenment

The Scottish Enlightenment (, ) was the period in 18th- and early-19th-century Scotland characterised by an outpouring of intellectual and scientific accomplishments. By the eighteenth century, Scotland had a network of parish schools in the Sco ...

which David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; – 25 August 1776) was a Scottish philosopher, historian, economist, and essayist who was best known for his highly influential system of empiricism, philosophical scepticism and metaphysical naturalism. Beg ...

had stated as "all inferences from experience suppose ... that the future will resemble the past", and James Hutton

James Hutton (; 3 June Old Style and New Style dates, O.S. 1726 – 26 March 1797) was a Scottish geologist, Agricultural science, agriculturalist, chemist, chemical manufacturer, Natural history, naturalist and physician. Often referred to a ...

had described when he wrote in 1788 that "from what has actually been, we have data for concluding with regard to that which is to happen thereafter." Geological remains from the distant past can, and should, be explained by reference to geological processes now in operation and thus directly observable. Lyell's interpretation of geological change as the steady accumulation of minute changes over enormously long spans of time was a powerful influence on the young Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

. Lyell asked Robert FitzRoy

Vice-Admiral Robert FitzRoy (5 July 1805 – 30 April 1865) was an English officer of the Royal Navy, politician and scientist who served as the second governor of New Zealand between 1843 and 1845. He achieved lasting fame as the captain of ...

, captain of HMS ''Beagle'', to search for erratic boulders on the survey voyage of the ''Beagle'', and just before it set out FitzRoy gave Darwin Volume 1 of the first edition of Lyell's ''Principles''. When the ''Beagle'' made its first stop ashore at St Jago in the Cape Verde

Cape Verde or Cabo Verde, officially the Republic of Cabo Verde, is an island country and archipelagic state of West Africa in the central Atlantic Ocean, consisting of ten volcanic islands with a combined land area of about . These islands ...

islands, Darwin found rock formations which seen "through Lyell's eyes" gave him a revolutionary insight into the geological history of the island, an insight he applied throughout his travels.

While in South America Darwin received Volume 2 which considered the ideas of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck

Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, chevalier de Lamarck (1 August 1744 – 18 December 1829), often known simply as Lamarck (; ), was a French naturalist, biologist, academic, and soldier. He was an early proponent of the idea that biologi ...

in some detail. Lyell rejected Lamarck's idea of organic evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

, proposing instead "Centres of Creation" to explain diversity and territory of species. However, as discussed below

Below may refer to:

*Earth

*Ground (disambiguation)

*Soil

*Floor

* Bottom (disambiguation)

*Less than

*Temperatures below freezing

*Hell or underworld

People with the surname

* Ernst von Below (1863–1955), German World War I general

* Fred Belo ...

, many of his letters show he was fairly open to the idea of evolution. In geology Darwin was very much Lyell's disciple, and brought back observations and his own original theorising, including ideas about the formation of atoll

An atoll () is a ring-shaped island, including a coral rim that encircles a lagoon. There may be coral islands or cays on the rim. Atolls are located in warm tropical or subtropical parts of the oceans and seas where corals can develop. Most ...

s, which supported Lyell's uniformitarianism. On the return of the ''Beagle'' (October 1836) Lyell invited Darwin to dinner and from then on they were close friends.

Although Darwin discussed evolutionary ideas with him from 1842, Lyell continued to reject evolution in each of the first nine editions of the ''Principles''. He encouraged Darwin to publish, and following the 1859 publication of ''

Although Darwin discussed evolutionary ideas with him from 1842, Lyell continued to reject evolution in each of the first nine editions of the ''Principles''. He encouraged Darwin to publish, and following the 1859 publication of ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life'')The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by M ...

'', Lyell finally offered a tepid endorsement of evolution in the tenth edition of ''Principles''.

''Elements of Geology'' began as the fourth volume of the third edition of ''Principles

A principle may relate to a fundamental truth or proposition that serves as the foundation for a system of beliefs or behavior or a chain of reasoning. They provide a guide for behavior or evaluation. A principle can make values explicit, so t ...

'': Lyell intended the book to act as a suitable field guide for students of geology. The systematic, factual description of geological formations of different ages contained in ''Principles'' grew so unwieldy, however, that Lyell split it off as the ''Elements'' in 1838. The book went through six editions, eventually growing to two volumes and ceasing to be the inexpensive, portable handbook that Lyell had originally envisioned. Late in his career, therefore, Lyell produced a condensed version titled ''Student's Elements of Geology'' that fulfilled the original purpose.

'' Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man'' brought together Lyell's views on three key themes from the geology of the Quaternary Period

The Quaternary ( ) is the current and most recent of the three periods of the Cenozoic Era in the geologic time scale of the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS), as well as the current and most recent of the twelve periods of the ...

of earth history: glaciers, evolution, and the age of the human race. First published in 1863, it went through three editions that year, with a fourth and final edition appearing in 1873. The book was widely regarded as a disappointment because of Lyell's equivocal treatment of evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

. Lyell, a highly religious man with a strong belief in the special status of human reason, had great difficulty reconciling his beliefs with natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the Heredity, heritable traits characteristic of a population over generation ...

.

Scientific contributions

Lyell's geological interests ranged fromvolcano

A volcano is commonly defined as a vent or fissure in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Earth, volcanoes are most oft ...

es and geological dynamics through stratigraphy

Stratigraphy is a branch of geology concerned with the study of rock layers (strata) and layering (stratification). It is primarily used in the study of sedimentary and layered volcanic rocks.

Stratigraphy has three related subfields: lithost ...

, palaeontology

Paleontology, also spelled as palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of the life of the past, mainly but not exclusively through the study of fossils. Paleontologists use fossils as a means to classify organisms, measure geo ...

, and glaciology

Glaciology (; ) is the scientific study of glaciers, or, more generally, ice and natural phenomena that involve ice.

Glaciology is an interdisciplinary Earth science that integrates geophysics, geology, physical geography, geomorphology, clim ...

to topics that would now be classified as prehistoric archaeology

Prehistoric archaeology is a subfield of archaeology, which deals specifically with artefacts, civilisations and other materials from societies that existed before any form of writing system or historical record. Often the field focuses on ages ...

and paleoanthropology

Paleoanthropology or paleo-anthropology is a branch of paleontology and anthropology which seeks to understand the early development of anatomically modern humans, a process known as hominization, through the reconstruction of evolutionary kinsh ...

. He is best known, however, for his role in elaborating the doctrine of uniformitarianism

Uniformitarianism, also known as the Doctrine of Uniformity or the Uniformitarian Principle, is the assumption that the same natural laws and processes that operate in our present-day scientific observations have always operated in the universe in ...

. He played a critical role in advancing the study of loess

A loess (, ; from ) is a clastic rock, clastic, predominantly silt-sized sediment that is formed by the accumulation of wind-blown dust. Ten percent of Earth's land area is covered by loesses or similar deposition (geology), deposits.

A loess ...

.

Uniformitarianism

From 1830 to 1833 his multi-volume ''Principles of Geology

''Principles of Geology: Being an Attempt to Explain the Former Changes of the Earth's Surface, by Reference to Causes Now in Operation'' is a book by the Scottish geologist Charles Lyell that was first published in 3 volumes from 1830 to 1833. ...

'' was published. The work's subtitle was "An attempt to explain the former changes of the earth's surface by reference to causes now in operation", and this explains Lyell's impact on science. He drew his explanations from field studies conducted directly before he went to work on the founding geology text. He was, along with the earlier John Playfair, the major advocate of James Hutton

James Hutton (; 3 June Old Style and New Style dates, O.S. 1726 – 26 March 1797) was a Scottish geologist, Agricultural science, agriculturalist, chemist, chemical manufacturer, Natural history, naturalist and physician. Often referred to a ...

's idea of uniformitarianism

Uniformitarianism, also known as the Doctrine of Uniformity or the Uniformitarian Principle, is the assumption that the same natural laws and processes that operate in our present-day scientific observations have always operated in the universe in ...

, that the earth was shaped entirely by slow-moving forces still in operation today, acting over a very long time. This was in contrast to catastrophism

In geology, catastrophism is the theory that the Earth has largely been shaped by sudden, short-lived, violent events, possibly worldwide in scope.

This contrasts with uniformitarianism (sometimes called gradualism), according to which slow inc ...

, an idea of abrupt geological changes, which had been adapted in England to explain landscape features—such as rivers much smaller than their associated valleys—that seemed impossible to explain other than through violent action. Criticizing the reliance of his contemporaries on what he argued were ''ad hoc'' explanations, Lyell wrote,

Never was there a doctrine more calculated to foster indolence, and to blunt the keen edge of curiosity, than this assumption of the discordance between the former and the existing causes of change... The student was taught to despond from the first. Geology, it was affirmed, could never arise to the rank of an exact science... ith catastrophismwe see the ancient spirit of speculation revived, and a desire manifestly shown to cut, rather than patiently untie, the Gordian Knot.-Sir Charles Lyell, ''Lyell saw himself as "the spiritual saviour of geology, freeing the science from the old dispensation of Moses." The two terms, ''uniformitarianism'' and ''catastrophism'', were both coined byPrinciples of Geology ''Principles of Geology: Being an Attempt to Explain the Former Changes of the Earth's Surface, by Reference to Causes Now in Operation'' is a book by the Scottish geologist Charles Lyell that was first published in 3 volumes from 1830 to 1833. ...'', 1854 edition, p. 196; quoted byStephen Jay Gould Stephen Jay Gould ( ; September 10, 1941 – May 20, 2002) was an American Paleontology, paleontologist, Evolutionary biology, evolutionary biologist, and History of science, historian of science. He was one of the most influential and widely re ....

William Whewell

William Whewell ( ; 24 May 17946 March 1866) was an English polymath. He was Master of Trinity College, Cambridge. In his time as a student there, he achieved distinction in both poetry and mathematics.

The breadth of Whewell's endeavours is ...

; in 1866 R. Grove suggested the simpler term ''continuity'' for Lyell's view, but the old terms persisted. In various revised editions (12 in all, through 1872), ''Principles of Geology'' was the most influential geological work in the middle of the 19th century and did much to put geology on a modern footing.

Geological surveys

Lyell noted the "economic advantages" geological surveys could provide, citing their felicity in mineral-rich countries and provinces. Modern surveys, like theBritish Geological Survey

The British Geological Survey (BGS) is a partly publicly funded body which aims to advance Earth science, geoscientific knowledge of the United Kingdom landmass and its continental shelf by means of systematic surveying, monitoring and research. ...

(founded in 1835), and the US Geological Survey

The United States Geological Survey (USGS), founded as the Geological Survey, is an agency of the U.S. Department of the Interior whose work spans the disciplines of biology, geography, geology, and hydrology. The agency was founded on March ...

(founded in 1879), map and exhibit the natural resources within their countries. Over time, these surveys have been used extensively by modern extractive industries, such as nuclear, coal, and oil.

Volcanoes and geological dynamics

Before Lyell's work, phenomena's such as earthquakes were understood by the destruction that they brought. One of the contributions that Lyell made in ''Principles'' was to explain the cause of earthquakes. Lyell, in contrast, focused on more recent earthquakes (150 yrs), evidenced by surface irregularities such as faults, fissures, stratigraphic displacements and depressions.

Lyell's work on volcanoes focused largely on

Before Lyell's work, phenomena's such as earthquakes were understood by the destruction that they brought. One of the contributions that Lyell made in ''Principles'' was to explain the cause of earthquakes. Lyell, in contrast, focused on more recent earthquakes (150 yrs), evidenced by surface irregularities such as faults, fissures, stratigraphic displacements and depressions.

Lyell's work on volcanoes focused largely on Vesuvius

Mount Vesuvius ( ) is a Somma volcano, somma–stratovolcano located on the Gulf of Naples in Campania, Italy, about east of Naples and a short distance from the shore. It is one of several volcanoes forming the Campanian volcanic arc. Vesuv ...

and Etna, both of which he had earlier studied. His conclusions supported gradual building of volcanoes, so-called "backed up-building", as opposed to the upheaval argument supported by other geologists.

Stratigraphy and human history

Lyell was a key figure in establishing the classification of more recent geological deposits, long known as theTertiary

Tertiary (from Latin, meaning 'third' or 'of the third degree/order..') may refer to:

* Tertiary period, an obsolete geologic period spanning from 66 to 2.6 million years ago

* Tertiary (chemistry), a term describing bonding patterns in organic ch ...

period. From May 1828, until February 1829, he travelled with Roderick Impey Murchison

Sir Roderick Impey Murchison, 1st Baronet (19 February 1792 – 22 October 1871) was a Scottish geologist who served as director-general of the British Geological Survey from 1855 until his death in 1871. He is noted for investigating and desc ...

(1792–1871) to the south of France (Auvergne volcanic district) and to Italy. In these areas he concluded that the recent strata (rock layers) could be categorised according to the number and proportion of marine shells encased within. Based on this the third volume of his ''Principles of Geology

''Principles of Geology: Being an Attempt to Explain the Former Changes of the Earth's Surface, by Reference to Causes Now in Operation'' is a book by the Scottish geologist Charles Lyell that was first published in 3 volumes from 1830 to 1833. ...

'', published in 1833, proposed dividing the Tertiary

Tertiary (from Latin, meaning 'third' or 'of the third degree/order..') may refer to:

* Tertiary period, an obsolete geologic period spanning from 66 to 2.6 million years ago

* Tertiary (chemistry), a term describing bonding patterns in organic ch ...

period into four parts, which he named the Eocene

The Eocene ( ) is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (Ma). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene'' comes ...

, Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first epoch (geology), geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and mea ...

, Pliocene

The Pliocene ( ; also Pleiocene) is the epoch (geology), epoch in the geologic time scale that extends from 5.33 to 2.58Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( ; referred to colloquially as the ''ice age, Ice Age'') is the geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fin ...

epoch, distinguishing a more recent fossil layer from the Pliocene. The Recent epoch renamed the Holocene

The Holocene () is the current geologic time scale, geological epoch, beginning approximately 11,700 years ago. It follows the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene to ...

by French paleontologist Paul Gervais

Paul Gervais (full name: François Louis Paul Gervais) (26 September 1816 – 10 February 1879) was a French palaeontologist and entomologist.

Biography

Gervais was born in Paris, where he obtained the diplomas of doctor of science and of medic ...

in 1867 included all deposits from the era subject to human observation. In recent years Lyell's subdivisions have been widely discussed with debates about the Anthropocene

''Anthropocene'' is a term that has been used to refer to the period of time during which human impact on the environment, humanity has become a planetary force of change. It appears in scientific and social discourse, especially with respect to ...

.

Glaciers

In ''Principles of Geology'' (first edition, vol. 3, ch. 2, 1833) Lyell proposed thaticeberg

An iceberg is a piece of fresh water ice more than long that has broken off a glacier or an ice shelf and is floating freely in open water. Smaller chunks of floating glacially derived ice are called "growlers" or "bergy bits". Much of an i ...

s could be the means of transport for erratics. During periods of global warming, ice breaks off the poles and floats across submerged continents, carrying debris with it, he conjectured. When the iceberg melts, it rains down sediments upon the land. Because this theory could account for the presence of diluvium, the word ''drift'' became the preferred term for the loose, unsorted material, today called ''till''. Furthermore, Lyell believed that the accumulation of fine angular particles covering much of the world (today called loess

A loess (, ; from ) is a clastic rock, clastic, predominantly silt-sized sediment that is formed by the accumulation of wind-blown dust. Ten percent of Earth's land area is covered by loesses or similar deposition (geology), deposits.

A loess ...

) was a deposit settled from mountain flood water. Today some of Lyell's mechanisms for geological processes have been disproven, though many have stood the test of time. His observational methods and general analytical framework remain in use today as foundational principles in geology.

Evolution

Lyell initially accepted the conventional view of other men of science, that the fossil record indicated a directional geohistory in which species went extinct. Around 1826, when he was on circuit, he read

Lyell initially accepted the conventional view of other men of science, that the fossil record indicated a directional geohistory in which species went extinct. Around 1826, when he was on circuit, he read Lamarck

Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, chevalier de Lamarck (1 August 1744 – 18 December 1829), often known simply as Lamarck (; ), was a French naturalist, biologist, academic, and soldier. He was an early proponent of the idea that biolo ...

's ''Zoological Philosophy'' and on 2 March 1827 wrote to Mantell, expressing admiration, but cautioning that he read it "rather as I hear an advocate on the wrong side, to know what can be made of the case in good hands".:

:I devoured Lamarck... his theories delighted me... I am glad that he has been courageous enough and logical enough to admit that his argument, if pushed as far as it must go, if worth anything, would prove that men may have come from the Ourang-Outang. But after all, what changes species may really undergo!... That the earth is quite as old as he supposes, has long been my creed...

He struggled with the implications for human dignity, and later in 1827 wrote private notes on Lamarck's ideas. Lyell reconciled transmutation of species

The Transmutation of species and transformism are 18th and early 19th-century ideas about the change of one species into another that preceded Charles Darwin's theory of evolution through natural selection. The French ''Transformisme'' was a ter ...

with natural theology

Natural theology is a type of theology that seeks to provide arguments for theological topics, such as the existence of a deity, based on human reason. It is distinguished from revealed theology, which is based on supernatural sources such as ...

by suggesting that it would be as much a "remarkable manifestation of creative Power" as creating each species separately. He countered Lamarck's views by rejecting continued cooling of the earth in favour of "a fluctuating cycle", a long-term steady-state geohistory as proposed by James Hutton

James Hutton (; 3 June Old Style and New Style dates, O.S. 1726 – 26 March 1797) was a Scottish geologist, Agricultural science, agriculturalist, chemist, chemical manufacturer, Natural history, naturalist and physician. Often referred to a ...

. The fragmentary fossil record already showed "a high class of fishes, close to reptiles" in the Carboniferous

The Carboniferous ( ) is a Geologic time scale, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era that spans 60 million years, from the end of the Devonian Period Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the ...

period which he called "the first Zoological era", and quadrupeds could also have existed then. In November 1827, after William Broderip

William John Broderip FRS (21 November 1789 – 27 February 1859) was an English lawyer and naturalist.

Life

Broderip, the eldest son of William Broderip, surgeon from Bristol, was born at Bristol on 21 November 1789, and, after being educat ...

found a Middle Jurassic

The Middle Jurassic is the second Epoch (geology), epoch of the Jurassic Period (geology), Period. It lasted from about 174.1 to 161.5 million years ago. Fossils of land-dwelling animals, such as dinosaurs, from the Middle Jurassic are relativel ...

fossil of the early mammal ''Didelphis

''Didelphis'' is a genus of New World marsupials. The six species in the genus ''Didelphis'', commonly known as Large American opossums, are members of the ''opossum'' order (biology), order, Didelphimorphia.

The genus ''Didelphis'' is composed ...

'', Lyell told his father that "There was everything but man even as far back as the Oolite." Lyell inaccurately portrayed Lamarckism as a response to the fossil record, and said it was falsified by a lack of progress. He said in the second volume of ''Principles'' that the occurrence of this one fossil of the higher mammalia "in these ancient strata, is as fatal to the theory of successive development, as if several hundreds had been discovered."

In the first edition of ''Principles'', the first volume briefly set out Lyell's concept of a steady state with no real progression of fossils. The sole exception was the advent of humanity, with no great physical distinction from animals, but with absolutely unique intellectual and moral qualities. The second volume dismissed Lamarck's claims of animal forms arising from habits, continuous spontaneous generation

Spontaneous generation is a superseded scientific theory that held that living creatures could arise from non-living matter and that such processes were commonplace and regular. It was hypothesized that certain forms, such as fleas, could ...

of new life, and man having evolved from lower forms. Lyell explicitly rejected Lamarck's concept of transmutation of species, drawing on Cuvier's arguments, and concluded that species had been created with stable attributes. He discussed the geographical distribution of plants and animals, and proposed that every species of plant or animal was descended from a pair or individual, originated in response to differing external conditions. Species would regularly go extinct, in a "struggle for existence" between hybrids, or a "war one with another" due to population pressure. He was vague about how replacement species formed, portraying this as an infrequent occurrence which could rarely be observed.

The leading man of science Sir John Herschel

Sir John Frederick William Herschel, 1st Baronet (; 7 March 1792 – 11 May 1871) was an English polymath active as a mathematician, astronomer, chemist, inventor and experimental photographer who invented the blueprint and did botanical work. ...

wrote from Cape Town

Cape Town is the legislature, legislative capital city, capital of South Africa. It is the country's oldest city and the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. Cape Town is the country's List of municipalities in South Africa, second-largest ...

on 20 February 1836, thanking Lyell for sending a copy of ''Principles'' and praising the book as opening a way for bold speculation on "that mystery of mysteries, the replacement of extinct species by others" – by analogy with other intermediate causes, "the origination of fresh species, could it ever come under our cognizance, would be found to be a natural in contradistinction to a miraculous process". Lyell replied: "In regard to the origination of new species, I am very glad to find that you think it probable that it may be carried on through the intervention of intermediate causes. I left this rather to be inferred, not thinking it worth while to offend a certain class of persons by embodying in words what would only be a speculation."

Whewell subsequently questioned this topic, and in March 1837 Lyell told him:

: If I had stated... the possibility of the introduction or origination of fresh species being a natural, in contradistinction to a miraculous process, I should have raised a host of prejudices against me, which are unfortunately opposed at every step to any philosopher who attempts to address the public on these mysterious subjects...

As a result of his letters and, no doubt, personal conversations, Huxley and

If I had stated... the possibility of the introduction or origination of fresh species being a natural, in contradistinction to a miraculous process, I should have raised a host of prejudices against me, which are unfortunately opposed at every step to any philosopher who attempts to address the public on these mysterious subjects...

As a result of his letters and, no doubt, personal conversations, Huxley and Ernst Haeckel

Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckel (; ; 16 February 1834 – 9 August 1919) was a German zoologist, natural history, naturalist, eugenics, eugenicist, Philosophy, philosopher, physician, professor, marine biology, marine biologist and artist ...

were convinced that, at the time he wrote ''Principles'', he believed new species had arisen by natural methods. Adam Sedgwick

Adam Sedgwick FRS (; 22 March 1785 – 27 January 1873) was a British geologist and Anglican priest, one of the founders of modern geology. He proposed the Cambrian and Devonian period of the geological timescale. Based on work which he did ...

wrote worried letters to him about this.

By the time Darwin returned from the ''Beagle'' survey expedition in 1836, he had begun to doubt Lyell's ideas about the permanence of species. He continued to be a close personal friend, and Lyell was one of the first scientists to support ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life'')The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by M ...

'', though he did not subscribe to all its contents. Lyell was also a friend of Darwin's closest colleagues, Joseph Dalton Hooker

Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker (30 June 1817 – 10 December 1911) was a British botanist and explorer in the 19th century. He was a founder of geographical botany and Charles Darwin's closest friend. For 20 years he served as director of the Ro ...

and Huxley, but unlike them he struggled to square his religious beliefs with evolution. This inner struggle has been much commented on. He had particular difficulty in believing in natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the Heredity, heritable traits characteristic of a population over generation ...

as the main motive force in evolution.

Lyell and Hooker were instrumental in arranging the peaceful co-publication of the theory of natural selection by Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace

Alfred Russel Wallace (8 January 1823 – 7 November 1913) was an English naturalist, explorer, geographer, anthropologist, biologist and illustrator. He independently conceived the theory of evolution through natural selection; his 1858 pap ...

in 1858: each had arrived at the theory independently. Lyell's views on gradual change and the power of a long time scale were important because Darwin thought that populations of an organism changed very slowly.

Although Lyell rejected evolution at the time of writing the ''Principles'', after the Darwin–Wallace papers and the ''Origin'' Lyell wrote in one of his notebooks on 3 May 1860:

:Mr. Darwin has written a work which will constitute an era in geology & natural history to show that... the descendants of common parents may become in the course of ages so unlike each other as to be entitled to rank as a distinct species, from each other or from some of their progenitors...

Lyell's acceptance of natural selection, Darwin's proposed mechanism for evolution, was equivocal, and came in the tenth edition of ''Principles''. '' The Antiquity of Man'' (published in early February 1863, just before Huxley's ''Man's place in nature'') drew these comments from Darwin to Huxley: "I am fearfully disappointed at Lyell's excessive caution" and "The book is a mere 'digest'". Quite strong remarks: no doubt Darwin resented Lyell's repeated suggestion that he owed a lot to

Quite strong remarks: no doubt Darwin resented Lyell's repeated suggestion that he owed a lot to Lamarck

Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, chevalier de Lamarck (1 August 1744 – 18 December 1829), often known simply as Lamarck (; ), was a French naturalist, biologist, academic, and soldier. He was an early proponent of the idea that biolo ...

, whom he (Darwin) had always specifically rejected. Darwin's daughter Henrietta (Etty) wrote to her father: "Is it fair that Lyell always calls your theory a modification of Lamarck's?"

In other respects ''Antiquity'' was a success. It sold well, and it "shattered the tacit agreement that mankind should be the sole preserve of theologians and historians". But when Lyell wrote that it remained a profound mystery how the huge gulf between man and beast could be bridged, Darwin wrote "Oh!" in the margin of his copy.

Legacy

Places named after Lyell: * Lyell, New Zealand * Lyell Butte, in theGrand Canyon

The Grand Canyon is a steep-sided canyon carved by the Colorado River in Arizona, United States. The Grand Canyon is long, up to wide and attains a depth of over a mile ().

The canyon and adjacent rim are contained within Grand Canyon Nati ...

* Lyell Canyon in Yosemite National Park

* Lyell Fork, one of two large forks of the Tuolumne River

* Lyell Land (Greenland)

*

* Lyell Canyon in Yosemite National Park

* Lyell Fork, one of two large forks of the Tuolumne River

* Lyell Land (Greenland)

* Lyell Glacier

Lyell Glacier is in the Sierra Nevada of California. The glacier was discovered by John Muir in 1871, and was the largest glacier in Yosemite National Park. It lies on the northern slopes of Mount Lyell.

The glacier has retreated since the en ...

* Lyell Glacier, South Georgia

Lyell Glacier () is a glacier flowing in a northerly direction to Harpon Bay at the southeast head of Cumberland West Bay, South Georgia. It was mapped by the Swedish Antarctic Expedition, 1901–04, under Otto Nordenskjöld, who named it for ...

* Mount Lyell (California)

* Mount Lyell (Canada)

* Mount Lyell (Tasmania)

*Lyell Avenue (Rochester, NY)

Bibliography

''Principles of Geology''

* ''Principles of Geology'' 1st edition, 1st vol. Jan. 1830 ( John Murray, London). * ''Principles of Geology'' 1st edition, 2nd vol. Jan. 1832 * ''Principles of Geology'' 1st edition, 3rd vol. May 1833 * ''Principles of Geology'' 2nd edition, 1st vol. 1832 * ''Principles of Geology'' 2nd edition, 2nd vol. Jan. 1833 * ''Principles of Geology'' 3rd edition, 4 vols. May 1834 * ''Principles of Geology'' 4th edition, 4 vols. June 1835 * ''Principles of Geology'' 5th edition, 4 vols. March 1837 * ''Principles of Geology'' 6th edition, 3 vols. June 1840 * ''Principles of Geology'' 7th edition, 1 vol. Feb. 1847 * ''Principles of Geology'' 8th edition, 1 vol. May 1850 * ''Principles of Geology'' 9th edition, 1 vol. June 1853 * ''Principles of Geology'' 10th edition, 1866–68 * ''Principles of Geology'' 11th edition, 2 vols. 1872 * ''Principles of Geology'' 12th edition, 2 vols. 1875 (published posthumously)''Elements of Geology''

*Elements of Geology

' 1 vol. 1st edition, July 1838 (John Murray, London) * ''Elements of Geology'' 2 vols. 2nd edition, July 1841 * ''Elements of Geology (Manual of Elementary Geology)'' 1 vol. 3rd edition, Jan. 1851 * ''Elements of Geology (Manual of Elementary Geology)'' 1 vol. 4th edition, Jan. 1852 * ''Elements of Geology (Manual of Elementary Geology)'' 1 vol. 5th edition, 1855 * ''Elements of Geology'' 6th edition, 1865

''Elements of Geology, The Student's Series'', 1871

''Travels in North America''

* * * *''Antiquity of Man''

* ''Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man'' 1 vol. 1st edition, Feb. 1863 (John Murray, London) * ''Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man'' 1 vol. 2nd edition, April 1863 * ''Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man'' 1 vol. 3rd edition, Nov. 1863 * ''Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man'' 1 vol. 4th edition, May 1873''Life, Letters, and Journals''

* *Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * ;Image source * Portraits of Honorary Members of the Ipswich Museum (Portfolio of 60 lithographs by T.H. Maguire) (George Ransome, Ipswich 1846–1852)Further reading

* '' Time's Arrow, Time's Cycle'' (1978), a book byStephen Jay Gould

Stephen Jay Gould ( ; September 10, 1941 – May 20, 2002) was an American Paleontology, paleontologist, Evolutionary biology, evolutionary biologist, and History of science, historian of science. He was one of the most influential and widely re ...

that reassesses Lyell's work

* ''Worlds Before Adam: The Reconstruction of Geohistory in the Age of Reform'' (2008), a major overview of Lyell's work in its scientific context by Martin J. S. Rudwick

* ''Principles of Geology: Penguin Classics'' (1997), the key chapters of Lyell's most famous work with an introduction by James A. Secord

External links

Website showcasing Lyell's comprehensive archive

held at the University of Edinburgh * * * * * *

at ESP.

''Principles of Geology''

(7th edition, 1847) from

Linda Hall Library

The Linda Hall Library is a privately endowed American library of science, engineering and technology located in Kansas City, Missouri, on the grounds of a urban arboretum. It claims to be the "largest independently funded public library of sc ...

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:Lyell, Charles

1797 births

1875 deaths

19th-century British geologists

Academics of King's College London

Alumni of Exeter College, Oxford

Burials at Westminster Abbey

Fellows of the Royal Society

Knights Bachelor

Members of Lincoln's Inn

Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

People from Angus, Scotland

Presidents of the Geological Society of London

Recipients of the Copley Medal

Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class)

Royal Medal winners

Scottish deists

Scottish geologists

Scottish knights

Scottish travel writers

Wollaston Medal winners

Lyell, Charles, 1st Baronet

People educated at Midhurst Grammar School

International members of the American Philosophical Society