Catapult Technologies on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A catapult is a

A catapult is a

abstract at medievalists.net, quote: "The trebuchet, invented in China between the fifth and third centuries B.C.E., reached the Mediterranean by the sixth century C.E." Early uses were also attributed to

The Invention of the Counterweight Trebuchet: A Study in Cultural Diffusion

, p.71, p.74, See citation:"The traction trebuchet, invented by the Chinese sometime before the fourth century B.C." in page 74 They were probably used by the

Trebuchets were probably the most powerful catapult employed in the Middle Ages. The most commonly used ammunition were stones, but "darts and sharp wooden poles" could be substituted if necessary. The most effective kind of ammunition though involved fire, such as "firebrands, and deadly

Trebuchets were probably the most powerful catapult employed in the Middle Ages. The most commonly used ammunition were stones, but "darts and sharp wooden poles" could be substituted if necessary. The most effective kind of ammunition though involved fire, such as "firebrands, and deadly

The last large scale military use of catapults was during the

The last large scale military use of catapults was during the

A catapult is a

A catapult is a ballistic

Ballistics may refer to:

Science

* Ballistics, the science that deals with the motion, behavior, and effects of projectiles

** Forensic ballistics, the science of analyzing firearm usage in crimes

** Internal ballistics, the study of the proce ...

device used to launch a projectile

A projectile is an object that is propelled by the application of an external force and then moves freely under the influence of gravity and air resistance. Although any objects in motion through space are projectiles, they are commonly found ...

at a great distance without the aid of gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, charcoal (which is mostly carbon), and potassium nitrate, potassium ni ...

or other propellant

A propellant (or propellent) is a mass that is expelled or expanded in such a way as to create a thrust or another motive force in accordance with Newton's third law of motion, and "propel" a vehicle, projectile, or fluid payload. In vehicle ...

s – particularly various types of ancient and medieval siege engine

A siege engine is a device that is designed to break or circumvent heavy castle doors, thick city walls and other fortifications in siege warfare. Some are immobile, constructed in place to attack enemy fortifications from a distance, while othe ...

s. A catapult uses the sudden release of stored potential energy

In physics, potential energy is the energy of an object or system due to the body's position relative to other objects, or the configuration of its particles. The energy is equal to the work done against any restoring forces, such as gravity ...

to propel its payload. Most convert tension or torsion

Torsion may refer to:

Science

* Torsion (mechanics), the twisting of an object due to an applied torque

* Torsion of spacetime, the field used in Einstein–Cartan theory and

** Alternatives to general relativity

* Torsion angle, in chemistry

Bio ...

energy that was more slowly and manually built up within the device before release, via springs, bows, twisted rope, elastic, or any of numerous other materials and mechanisms which allow the catapult to launch a projectile such as rocks, cannon balls, or debris.

During wars in the ancient times, the catapult was usually known to be the strongest heavy weaponry. In modern times the term can apply to devices ranging from a simple hand-held implement (also called a "slingshot

A slingshot or catapult is a small hand-powered projectile weapon. The classic form consists of a Y-shaped frame, with two tubes or strips made from either a natural rubber or synthetic elastic material. These are attached to the upper two ends ...

") to a mechanism for launching aircraft from a ship.

The earliest catapults date to at least the 7th century BC, with King Uzziah

Uzziah (; ''‘Uzzīyyāhū'', meaning "my strength is Yah"; ; ), also known as Azariah (; ''‘Azaryā''; ; ), was the tenth king of the ancient Kingdom of Judah, and one of Amaziah's sons. () Uzziah was 16 when he became king of Judah and ...

of Judah recorded as equipping the walls of Jerusalem with machines that shot "great stones". Catapults are mentioned in Yajurveda

The ''Yajurveda'' (, , from यजुस्, "worship", and वेद, "knowledge") is the Veda primarily of prose mantras for worship rituals.Michael Witzel (2003), "Vedas and Upaniṣads", in ''The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism'' (Edito ...

under the name "Jyah" in chapter 30, verse 7. In the 5th century BC the mangonel

The mangonel, also called the traction trebuchet, was a type of trebuchet used in Ancient China starting from the Warring States period, and later across Eurasia by the 6th century AD. Unlike the later counterweight trebuchet, the mangonel was ...

appeared in ancient China

The history of China spans several millennia across a wide geographical area. Each region now considered part of the Chinese world has experienced periods of unity, fracture, prosperity, and strife. Chinese civilization first emerged in the Y ...

, a type of traction trebuchet

A trebuchet () is a type of catapult that uses a hinged arm with a sling attached to the tip to launch a projectile. It was a common powerful siege engine until the advent of gunpowder. The design of a trebuchet allows it to launch projectiles ...

and catapult.Chevedden et al. (1995)abstract at medievalists.net, quote: "The trebuchet, invented in China between the fifth and third centuries B.C.E., reached the Mediterranean by the sixth century C.E." Early uses were also attributed to

Ajatashatru

Ajatasattu (Pāli: ) or Ajatashatru (Sanskrit: ) in the Buddhist tradition, or Kunika () and Kuniya () in the Jain tradition (reigned c. 492 to 460 BCE, or c. 405 to 373 BCE), was one of the most important kings of the Haryanka dynasty of Mag ...

of Magadha

Magadha was a region and kingdom in ancient India, based in the eastern Ganges Plain. It was one of the sixteen Mahajanapadas during the Second Urbanization period. The region was ruled by several dynasties, which overshadowed, conquered, and ...

in his 5th century BC war against the Licchavis. Greek catapults were invented in the early 4th century BC, being attested by Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus or Diodorus of Sicily (; 1st century BC) was an ancient Greece, ancient Greek historian from Sicily. He is known for writing the monumental Universal history (genre), universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty ...

as part of the equipment of a Greek army in 399 BC, and subsequently used at the siege of Motya

The siege of Motya took place in summer 398 BC in western Sicily. Dionysius, after securing peace with Carthage in 405 BC, had steadily increased his military power and had tightened his grip on Syracuse. He had fortified Syracuse against sie ...

in 397 BC.Diod. Sic. 14.42.1.

.

Etymology

The word 'catapult' comes from theLatin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

'catapulta', which in turn comes from the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

(''katapeltēs''), itself from κατά (''kata''), "downwards" and πάλλω (''pallō''), "to toss, to hurl". Catapults were invented by the ancient Greeks

Ancient Greece () was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity (), that comprised a loose collection of culturally and linguistically re ...

and in ancient India

Anatomically modern humans first arrived on the Indian subcontinent between 73,000 and 55,000 years ago. The earliest known human remains in South Asia date to 30,000 years ago. Sedentism, Sedentariness began in South Asia around 7000 BCE; ...

where they were used by the Magadhan King Ajatashatru

Ajatasattu (Pāli: ) or Ajatashatru (Sanskrit: ) in the Buddhist tradition, or Kunika () and Kuniya () in the Jain tradition (reigned c. 492 to 460 BCE, or c. 405 to 373 BCE), was one of the most important kings of the Haryanka dynasty of Mag ...

around the early to mid 5th century BC.

Greek and Roman catapults

The catapult andcrossbow

A crossbow is a ranged weapon using an Elasticity (physics), elastic launching device consisting of a Bow and arrow, bow-like assembly called a ''prod'', mounted horizontally on a main frame called a ''tiller'', which is hand-held in a similar f ...

in Greece are closely intertwined. Primitive catapults were essentially "the product of relatively straightforward attempts to increase the range and penetrating power of missiles by strengthening the bow which propelled them". The historian Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus or Diodorus of Sicily (; 1st century BC) was an ancient Greece, ancient Greek historian from Sicily. He is known for writing the monumental Universal history (genre), universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty ...

(fl. 1st century BC), described the invention of a mechanical arrow-firing catapult (''katapeltikon'') by a Greek task force in 399 BC. The weapon was soon after employed against Motya

Motya was an ancient and powerful city on San Pantaleo Island off the west coast of Sicily, in the Stagnone Lagoon between Drepanum (modern Trapani) and Lilybaeum (modern Marsala). It is within the present-day comune, commune of Marsala, Ital ...

(397 BC), a key Carthaginian The term Carthaginian ( ) usually refers to the civilisation of ancient Carthage.

It may also refer to:

* Punic people, the Semitic-speaking people of Carthage

* Punic language

The Punic language, also called Phoenicio-Punic or Carthaginian, i ...

stronghold in Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

.. Diodorus is assumed to have drawn his description from the highly rated history of Philistus

Philistus (; 432 – 356 BC), son of Archomenidas, was a Greek historian from Sicily, Magna Graecia. Life

Philistus was born in Syracuse around the time the Peloponnesian War began. He was a faithful supporter of the elder Dionysius, and c ...

, a contemporary of the events then. The introduction of crossbows however, can be dated further back: according to the inventor Hero of Alexandria

Hero of Alexandria (; , , also known as Heron of Alexandria ; probably 1st or 2nd century AD) was a Greek mathematician and engineer who was active in Alexandria in Egypt during the Roman era. He has been described as the greatest experimental ...

(fl. 1st century AD), who referred to the now lost works of the 3rd-century BC engineer Ctesibius

Ctesibius or Ktesibios or Tesibius (; BCE) was a Greek inventor and mathematician in Alexandria, Ptolemaic Egypt. Very little is known of Ctesibius' life, but his inventions were well known in his lifetime. He was likely the first head of th ...

, this weapon was inspired by an earlier foot-held crossbow, called the ''gastraphetes

The gastraphetes (), also called belly bow or belly shooter, was a hand-held crossbow used by the Ancient Greeks. It was described in the 1st century by the Greek author Heron of Alexandria in his work ''Belopoeica'', which draws on an earlier ac ...

'', which could store more energy than the Greek bows. A detailed description of the ''gastraphetes'', or the "belly-bow",

. along with a watercolor drawing, is found in Heron's technical treatise ''Belopoeica''.

.

A third Greek author, Biton Biton (Hebrew: ביטון) is a Maghrebi Jewish surname which is common in Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jorda ...

(fl. 2nd century BC), whose reliability has been positively reevaluated by recent scholarship, described two advanced forms of the ''gastraphetes'', which he credits to Zopyros, an engineer from southern Italy

Southern Italy (, , or , ; ; ), also known as () or (; ; ; ), is a macroregion of Italy consisting of its southern Regions of Italy, regions.

The term "" today mostly refers to the regions that are associated with the people, lands or cultu ...

. Zopyrus has been plausibly equated with a Pythagorean

Pythagorean, meaning of or pertaining to the ancient Ionian mathematician, philosopher, and music theorist Pythagoras, may refer to:

Philosophy

* Pythagoreanism, the esoteric and metaphysical beliefs purported to have been held by Pythagoras

* Ne ...

of that name who seems to have flourished in the late 5th century BC. He probably designed his bow-machines on the occasion of the sieges of Cumae

Cumae ( or or ; ) was the first ancient Greek colony of Magna Graecia on the mainland of Italy and was founded by settlers from Euboea in the 8th century BCE. It became a rich Roman city, the remains of which lie near the modern village of ...

and Milet

Miletus (Ancient Greek: Μίλητος, Mílētos) was an influential ancient Greek city on the western coast of Anatolia, near the mouth of the Maeander River in present day Turkey. Renowned in antiquity for its wealth, maritime power, and e ...

between 421 BC and 401 BC.. The bows of these machines already featured a winched pull back system and could apparently throw two missiles at once.

Philo of Byzantium

Philo of Byzantium (, ''Phílōn ho Byzántios'', ), also known as Philo Mechanicus (Latin for "Philo the Engineer"), was a Greek engineer, physicist and writer on mechanics, who lived during the latter half of the 3rd century BC. Although he wa ...

provides probably the most detailed account on the establishment of a theory of belopoietics (''belos'' = "projectile"; ''poietike'' = "(art) of making") circa 200 BC. The central principle to this theory was that "all parts of a catapult, including the weight or length of the projectile, were proportional to the size of the torsion springs". This kind of innovation is indicative of the increasing rate at which geometry and physics were being assimilated into military enterprises.

From the mid-4th century BC onwards, evidence of the Greek use of arrow-shooting machines becomes more dense and varied: arrow firing machines (''katapaltai'') are briefly mentioned by Aeneas Tacticus

Aeneas Tacticus (; fl. 4th century BC) was one of the earliest Greek writers on the art of war and is credited as the first author to provide a complete guide to securing military communications. Polybius described his design for a hydraulic se ...

in his treatise on siegecraft written around 350 BC. An extant inscription from the Athenian

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

arsenal, dated between 338 and 326 BC, lists a number of stored catapults with shooting bolts of varying size and springs of sinews.. The later entry is particularly noteworthy as it constitutes the first clear evidence for the switch to torsion

Torsion may refer to:

Science

* Torsion (mechanics), the twisting of an object due to an applied torque

* Torsion of spacetime, the field used in Einstein–Cartan theory and

** Alternatives to general relativity

* Torsion angle, in chemistry

Bio ...

catapults, which are more powerful than the more-flexible crossbows and which came to dominate Greek and Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of Roman civilization

*Epistle to the Romans, shortened to Romans, a letter w ...

artillery design thereafter.. This move to torsion springs was likely spurred by the engineers of Philip II of Macedonia. Another Athenian inventory from 330 to 329 BC includes catapult bolts with heads and flights. As the use of catapults became more commonplace, so did the training required to operate them. Many Greek children were instructed in catapult usage, as evidenced by "a 3rd Century B.C. inscription from the island of Ceos in the Cyclades egulatingcatapult shooting competitions for the young". Arrow firing machines in action are reported from Philip II's siege of Perinth (Thrace

Thrace (, ; ; ; ) is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe roughly corresponding to the province of Thrace in the Roman Empire. Bounded by the Balkan Mountains to the north, the Aegean Sea to the south, and the Black Se ...

) in 340 BC.. At the same time, Greek fortifications began to feature high towers with shuttered windows in the top, which could have been used to house anti-personnel arrow shooters, as in Aigosthena

Aigosthena () was an ancient Greek fortified port city of Megaris, northwest of the ancient city of Megara to which it belonged. It is also the name of the coastal settlement at the foot of the ancient city walls, also known as Porto Germeno. ...

. Projectiles included both arrows and (later) stones that were sometimes lit on fire. Onomarchus of Phocis first used catapults on the battlefield against Philip II of Macedon

Philip II of Macedon (; 382 BC – October 336 BC) was the king (''basileus'') of the ancient kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedonia from 359 BC until his death in 336 BC. He was a member of the Argead dynasty, founders of the ...

. Philip's son, Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

, was the next commander in recorded history to make such use of catapults on the battlefield as well as to use them during sieges.

The Romans started to use catapults as arms for their wars against Syracuse

Syracuse most commonly refers to:

* Syracuse, Sicily, Italy; in the province of Syracuse

* Syracuse, New York, USA; in the Syracuse metropolitan area

Syracuse may also refer to:

Places

* Syracuse railway station (disambiguation)

Italy

* Provi ...

, Macedon, Sparta and Aetolia (3rd and 2nd centuries BC). The Roman machine known as an arcuballista was similar to a large crossbow. Later the Romans used ballista

The ballista (Latin, from Ancient Greek, Greek βαλλίστρα ''ballistra'' and that from βάλλω ''ballō'', "throw"), plural ballistae or ballistas, sometimes called bolt thrower, was an Classical antiquity, ancient missile weapon tha ...

catapults on their warships.

Other ancient catapults

In chronological order: * 19th century BC, Egypt, walls of the fortress ofBuhen

Buhen, alternatively known as Βοὥν (Bohón) in Ancient Greek, stands as a significant ancient Egyptian settlement on the western bank of the Nile, just below the Second Cataract in present-day Northern State, Sudan. Its origins trace back t ...

appear to contain platforms for siege weapons.

* c.750 BC, Judah, King Uzziah

Uzziah (; ''‘Uzzīyyāhū'', meaning "my strength is Yah"; ; ), also known as Azariah (; ''‘Azaryā''; ; ), was the tenth king of the ancient Kingdom of Judah, and one of Amaziah's sons. () Uzziah was 16 when he became king of Judah and ...

is documented as having overseen the construction of machines to "shoot great stones".

* between 484 and 468 BC, India, Ajatashatru

Ajatasattu (Pāli: ) or Ajatashatru (Sanskrit: ) in the Buddhist tradition, or Kunika () and Kuniya () in the Jain tradition (reigned c. 492 to 460 BCE, or c. 405 to 373 BCE), was one of the most important kings of the Haryanka dynasty of Mag ...

is recorded in Jaina texts as having used catapults in his campaign against the Licchavis.

* between 500 and 300 BC, China, recorded use of mangonel

The mangonel, also called the traction trebuchet, was a type of trebuchet used in Ancient China starting from the Warring States period, and later across Eurasia by the 6th century AD. Unlike the later counterweight trebuchet, the mangonel was ...

s.Chevedden, Paul E.; Eigenbrod, Les; Foley, Vernard; Soedel, Werner. (July 1995). "The Trebuchet". Scientific American

''Scientific American'', informally abbreviated ''SciAm'' or sometimes ''SA'', is an American popular science magazine. Many scientists, including Albert Einstein and Nikola Tesla, have contributed articles to it, with more than 150 Nobel Pri ...

, pp. 66–71. Original version.Paul E. CheveddenThe Invention of the Counterweight Trebuchet: A Study in Cultural Diffusion

, p.71, p.74, See citation:"The traction trebuchet, invented by the Chinese sometime before the fourth century B.C." in page 74 They were probably used by the

Mohist

Mohism or Moism (, ) was an ancient Chinese philosophy of ethics and logic, rational thought, and scientific technology developed by the scholars who studied under the ancient Chinese philosopher Mozi (), embodied in an eponymous book: the '' ...

s as early as the 4th century BC, descriptions of which can be found in the ''Mojing'' (compiled in the 4th century BC). In Chapter 14 of the ''Mojing'', the mangonel is described hurling hollowed out logs filled with burning charcoal at enemy troops. The mangonel was carried westward by the Avars and appeared next in the eastern Mediterranean by the late 6th century AD, where it replaced torsion powered siege engines such as the ballista and onager due to its simpler design and faster rate of fire. The Byzantines adopted the mangonel possibly as early as 587, the Persians in the early 7th century, and the Arabs in the second half of the 7th century. The Franks

file:Frankish arms.JPG, Aristocratic Frankish burial items from the Merovingian dynasty

The Franks ( or ; ; ) were originally a group of Germanic peoples who lived near the Rhine river, Rhine-river military border of Germania Inferior, which wa ...

and Saxons

The Saxons, sometimes called the Old Saxons or Continental Saxons, were a Germanic people of early medieval "Old" Saxony () which became a Carolingian " stem duchy" in 804, in what is now northern Germany. Many of their neighbours were, like th ...

adopted the weapon in the 8th century.

Medieval catapults

Castle

A castle is a type of fortification, fortified structure built during the Middle Ages predominantly by the nobility or royalty and by Military order (monastic society), military orders. Scholars usually consider a ''castle'' to be the private ...

s and fortified walled cities

A defensive wall is a fortification usually used to protect a city, town or other settlement from potential aggressors. The walls can range from simple palisades or earthworks to extensive military fortifications such as curtain walls with to ...

were common during this period and catapults were used as siege weapon

A siege engine is a device that is designed to break or circumvent heavy castle doors, thick city walls and other fortifications in siege warfare. Some are immobile, constructed in place to attack enemy fortifications from a distance, while othe ...

s against them. As well as their use in attempts to breach walls, incendiary missiles, or diseased carcasses or garbage could be catapulted over the walls.

Defensive techniques in the Middle Ages progressed to a point that rendered catapults largely ineffective. The Viking siege of Paris

Vikings were seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway, and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded, and settled throughout parts of Europe.Roesdahl, pp. 9� ...

(AD 885–6) "saw the employment by both sides of virtually every instrument of siege craft known to the classical world, including a variety of catapults", to little effect, resulting in failure..

The most widely used catapults throughout the Middle Ages were as follows:.

; Ballista

The ballista (Latin, from Ancient Greek, Greek βαλλίστρα ''ballistra'' and that from βάλλω ''ballō'', "throw"), plural ballistae or ballistas, sometimes called bolt thrower, was an Classical antiquity, ancient missile weapon tha ...

: Ballistae were similar to giant crossbows and were designed to work through torsion. The projectiles were large arrows or darts made from wood with an iron tip. These arrows were then shot "along a flat trajectory" at a target. Ballistae were accurate, but lacked firepower compared with that of a mangonel or trebuchet. Because of their immobility, most ballistae were constructed on site following a siege assessment by the commanding military officer.

:

; Springald

A springald, or espringal, was a Torsion siege engine device for throwing bolts in medieval times. It is depicted in a diagram in an 11th-century Byzantine manuscript, but in Western Europe is more evident in the late 12th century and early 13th c ...

: The springald's design resembles that of the ballista, being a crossbow powered by tension. The springald's frame was more compact, allowing for use inside tighter confines, such as the inside of a castle or tower, but compromising its power.

:

; Mangonel

The mangonel, also called the traction trebuchet, was a type of trebuchet used in Ancient China starting from the Warring States period, and later across Eurasia by the 6th century AD. Unlike the later counterweight trebuchet, the mangonel was ...

: This machine was designed to throw heavy projectiles from a "bowl-shaped bucket at the end of its arm". Mangonels were mostly used for “firing various missiles at fortresses, castles, and cities,” with a range of up to . These missiles included anything from stones to excrement to rotting carcasses. Mangonels were relatively simple to construct, and eventually wheels were added to increase mobility.

:

; Onager

The onager (, ) (''Equus hemionus''), also known as hemione or Asiatic wild ass, is a species of the family Equidae native to Asia. A member of the subgenus ''Asinus'', the onager was Scientific description, described and given its binomial name ...

: Mangonels are also sometimes referred to as Onagers. Onager catapults initially launched projectiles from a sling, which was later changed to a "bowl-shaped bucket". The word ''Onager'' is derived from the Greek word ''onagros'' for "wild ass", referring to the "kicking motion and force" that were recreated in the Mangonel's design. Historical records regarding onagers are scarce. The most detailed account of Mangonel use is from "Eric Marsden's translation of a text written by Ammianus Marcellius in the 4th Century AD" describing its construction and combat usage..

:

; Trebuchet

A trebuchet () is a type of catapult that uses a hinged arm with a sling attached to the tip to launch a projectile. It was a common powerful siege engine until the advent of gunpowder. The design of a trebuchet allows it to launch projectiles ...

:  Trebuchets were probably the most powerful catapult employed in the Middle Ages. The most commonly used ammunition were stones, but "darts and sharp wooden poles" could be substituted if necessary. The most effective kind of ammunition though involved fire, such as "firebrands, and deadly

Trebuchets were probably the most powerful catapult employed in the Middle Ages. The most commonly used ammunition were stones, but "darts and sharp wooden poles" could be substituted if necessary. The most effective kind of ammunition though involved fire, such as "firebrands, and deadly Greek Fire

Greek fire was an incendiary weapon system used by the Byzantine Empire from the seventh to the fourteenth centuries. The recipe for Greek fire was a closely-guarded state secret; historians have variously speculated that it was based on saltp ...

". Trebuchets came in two different designs: Traction, which were powered by people, or Counterpoise, where the people were replaced with "a weight on the short end". The most famous historical account of trebuchet use dates back to the siege of Stirling Castle

Stirling Castle, located in Stirling, is one of the largest and most historically and architecturally important castles in Scotland. The castle sits atop an Intrusive rock, intrusive Crag and tail, crag, which forms part of the Stirling Sill ge ...

in 1304, when the army of Edward I constructed a giant trebuchet known as Warwolf

The Warwolf, also known as the ''Loup-de-Guerre'' or ''Ludgar'', is believed to have been the largest trebuchet ever made. It was created in Scotland by order of Edward I of England, during the siege of Stirling Castle in 1304, as part of the ...

, which then proceeded to "level a section of astle

Astle is an English language, English surname of dual origins. In the East Midlands, the surname is certainly of patronymic origin. This is also a possibility in Cheshire yet the name there more probably originated as a Surname#Location name, l ...

wall, successfully concluding the siege".

:

; Couillard: A simplified trebuchet, where the trebuchet's single counterweight is split, swinging on either side of a central support post.

:

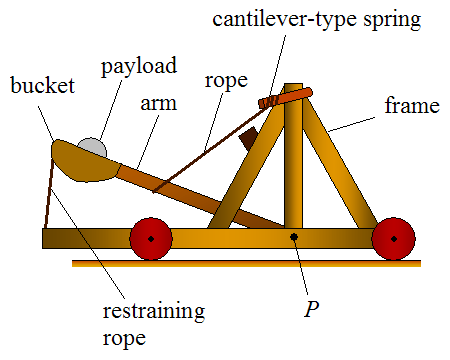

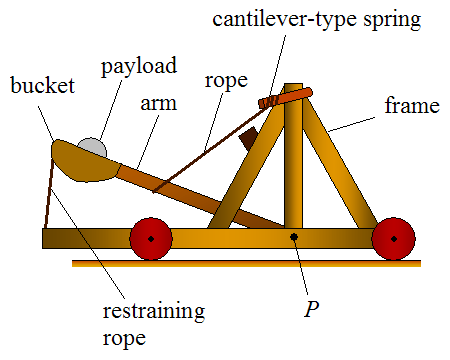

; Leonardo da Vinci's catapult: Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 1452 - 2 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially rested o ...

sought to improve the efficiency and range of earlier designs. His design incorporated a large wooden leaf spring

A leaf spring is a simple form of spring (device), spring commonly used for suspension (vehicle), suspension in wheeled vehicles. Originally called a ''laminated'' or ''carriage spring'', and sometimes referred to as a semi-elliptical spring, e ...

as an accumulator to power the catapult. Both ends of the bow are connected by a rope, similar to the design of a bow and arrow

The bow and arrow is a ranged weapon system consisting of an elasticity (physics), elastic launching device (bow) and long-shafted projectiles (arrows). Humans used bows and arrows for hunting and aggression long before recorded history, and the ...

. The leaf spring was not used to pull the catapult armature directly, rather the rope was wound around a drum. The catapult armature was attached to this drum which would be turned until enough potential energy was stored in the deformation of the spring. The drum would then be disengaged from the winding mechanism, and the catapult arm would snap around. Though no records exist of this design being built during Leonardo's lifetime, contemporary enthusiasts have reconstructed it.

Modern use

Military

The last large scale military use of catapults was during the

The last large scale military use of catapults was during the trench warfare

Trench warfare is a type of land warfare using occupied lines largely comprising Trench#Military engineering, military trenches, in which combatants are well-protected from the enemy's small arms fire and are substantially sheltered from a ...

of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. During the early stages of the war, catapults were used to throw hand grenade

A grenade is a small explosive weapon typically thrown by hand (also called hand grenade), but can also refer to a Shell (projectile), shell (explosive projectile) shot from the muzzle of a rifle (as a rifle grenade) or a grenade launcher. A mod ...

s across no man's land into enemy trenches. They were eventually replaced by small mortars

Mortar may refer to:

* Mortar (weapon), an indirect-fire infantry weapon

* Mortar (masonry), a material used to fill the gaps between blocks and bind them together

* Mortar and pestle, a tool pair used to crush or grind

* Mortar, Bihar, a village i ...

.

The SPBG (Silent Projector of Bottles and Grenades) was a Soviet proposal for an anti-tank weapon that launched grenades from a spring-loaded shuttle up to .

Special variants called aircraft catapult

An aircraft catapult is a device used to help fixed-wing aircraft gain enough airspeed and lift for takeoff from a limited distance, typically from the deck of a ship. They are usually used on aircraft carrier flight decks as a form of assist ...

s are used to launch planes from land bases and sea carriers when the takeoff runway is too short for a powered takeoff or simply impractical to extend. Ships also use them to launch torpedoes and deploy bombs against submarines.

In 2024, during the Gaza war

The Gaza war is an armed conflict in the Gaza Strip and southern Israel fought since 7 October 2023. A part of the unresolved Israeli–Palestinian conflict, Israeli–Palestinian and Gaza–Israel conflict, Gaza–Israel conflicts dating ...

, a trebuchet created by private initiative of an IDF reserve unit was used to throw firebrands over the border into Lebanon, in order to set on fire the undergrowth which offered camouflage to Hezbollah

Hezbollah ( ; , , ) is a Lebanese Shia Islamist political party and paramilitary group. Hezbollah's paramilitary wing is the Jihad Council, and its political wing is the Loyalty to the Resistance Bloc party in the Lebanese Parliament. I ...

fighters.

Toys, sports, entertainment

In the 1840s, the invention ofvulcanized

Vulcanization (British English: vulcanisation) is a range of processes for hardening rubbers. The term originally referred exclusively to the treatment of natural rubber with sulfur, which remains the most common practice. It has also grown to ...

rubber

Rubber, also called India rubber, latex, Amazonian rubber, ''caucho'', or ''caoutchouc'', as initially produced, consists of polymers of the organic compound isoprene, with minor impurities of other organic compounds.

Types of polyisoprene ...

allowed the making of small hand-held catapults, either improvised from Y-shaped sticks or manufactured for sale; both were popular with children and teenagers. These devices were also known as slingshots

A slingshot or catapult is a small hand-powered projectile weapon. The classic form consists of a Y-shaped frame, with two tubes or strips made from either a natural rubber or synthetic elastic material. These are attached to the upper two ends ...

in the United States.

Small catapults, referred to as "traps", are still widely used to launch clay target

Clay pigeon shooting, also known as clay target shooting, is a shooting sport involving shooting at special flying targets known as "clay pigeons" or "clay targets" with a shotgun. Despite their name, the targets are usually inverted saucers ...

s into the air in the sport of clay pigeon shooting

Clay pigeon shooting, also known as clay target shooting, is a shooting sport involving shooting at shooting target#Clay pigeons, special flying targets known as "clay pigeons" or "clay targets" with a shotgun. Despite their name, the targets ...

.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, a powerful catapult, a trebuchet, was used by thrill-seekers first on private property and in 2001–2002 at Middlemoor Water Park, Somerset, England, to experience being catapulted through the air for . The practice has been discontinued due to a fatality at the Water Park. There had been an injury when the trebuchet was in use on private property. Injury and death occurred when those two participants failed to land onto the safety net. The operators of the trebuchet were tried, but found not guilty of manslaughter, though the jury noted that the fatality might have been avoided had the operators "imposed stricter safety measures." Human cannonball circus

A circus is a company of performers who put on diverse entertainment shows that may include clowns, acrobats, trained animals, trapeze acts, musicians, dancers, hoopers, tightrope walkers, jugglers, magicians, ventriloquists, and unicy ...

acts use a catapult launch mechanism, rather than gunpowder, and are risky ventures for the human cannonballs.

Early launched roller coaster

The launched roller coaster is a type of roller coaster that initiates a ride with high amounts of acceleration via one or a series of linear induction motors (LIM), linear synchronous motors (LSM), catapults, tires, chains, or other mechanism ...

s used a catapult system powered by a diesel engine or a dropped weight to acquire their momentum, such as Shuttle Loop

Shuttle Loop is a type of steel launched shuttle roller coaster designed by Reinhold Spieldiener of Intamin and manufactured by Anton Schwarzkopf. A total of 12 installations were produced between 1977 and 1982. These 12 installations have bee ...

installations between 1977 and 1978. The catapult system for roller coasters has been replaced by flywheel

A flywheel is a mechanical device that uses the conservation of angular momentum to store rotational energy, a form of kinetic energy proportional to the product of its moment of inertia and the square of its rotational speed. In particular, a ...

s and later linear motor

A linear motor is an electric motor that has had its stator and rotor (electric), rotor "unrolled", thus, instead of producing a torque (rotation), it produces a linear force along its length. However, linear motors are not necessarily straight. ...

s.

'' Pumpkin chunking'' is another widely popularized use, in which people compete to see who can launch a pumpkin the farthest by mechanical means (although the world record is held by a pneumatic air cannon).

Smuggling

In January 2011, a homemade catapult was discovered that was used tosmuggle

Smuggling is the illegal transportation of objects, substances, information or people, such as out of a house or buildings, into a prison, or across an international border, in violation of applicable laws or other regulations. More broadly, soc ...

cannabis

''Cannabis'' () is a genus of flowering plants in the family Cannabaceae that is widely accepted as being indigenous to and originating from the continent of Asia. However, the number of species is disputed, with as many as three species be ...

into the United States from Mexico. The machine was found from the border fence with bales of cannabis ready to launch..

See also

*Aircraft catapult

An aircraft catapult is a device used to help fixed-wing aircraft gain enough airspeed and lift for takeoff from a limited distance, typically from the deck of a ship. They are usually used on aircraft carrier flight decks as a form of assist ...

* Centrifugal gun

A centrifugal gun is a type of rapid-fire projectile accelerator, like a machine gun but operating on a different principle. Centrifugal guns use a rapidly rotating disc to impart energy to the projectiles, gaining kinetic energy from steam, elec ...

* List of siege engines

This is a list of siege engines invented through history. A siege engine is a weapon used to circumvent or destroy fortifications such as defensive walls, castles, bunkers and fortified gateways. Petrary is the generic term for medieval stone th ...

* Mangonel

The mangonel, also called the traction trebuchet, was a type of trebuchet used in Ancient China starting from the Warring States period, and later across Eurasia by the 6th century AD. Unlike the later counterweight trebuchet, the mangonel was ...

* Mass driver

A mass driver or electromagnetic catapult is a proposed method of non-rocket spacelaunch which would use a linear motor to Acceleration, accelerate and catapult Payload (air and space craft), payloads up to high speeds. Existing and proposed mass ...

* National Catapult Contest

* Sling (weapon)

A sling is a projectile weapon typically used to hand-throw a blunt projectile such as a stone, clay, or lead " sling-bullet". It is also known as the shepherd's sling or slingshot (in British English, although elsewhere it means something ...

* Trebuchet

A trebuchet () is a type of catapult that uses a hinged arm with a sling attached to the tip to launch a projectile. It was a common powerful siege engine until the advent of gunpowder. The design of a trebuchet allows it to launch projectiles ...

Notes

References

Bibliography

* . * . * . * . * . * . * .External links

* * . * . * . * . * . {{Authority control Projectile weapons Siege engines Obsolete technologies