CagA on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Helicobacter pylori'', previously known as ''Campylobacter pylori'', is a

An infection with ''Helicobacter pylori'' can either have no symptoms even when lasting a lifetime, or can harm the stomach and duodenal linings by inflammatory responses induced by several mechanisms associated with a number of

An infection with ''Helicobacter pylori'' can either have no symptoms even when lasting a lifetime, or can harm the stomach and duodenal linings by inflammatory responses induced by several mechanisms associated with a number of  The inflammatory response caused by bacteria colonizing near the pyloric antrum induces G cells in the antrum to secrete the hormone

The inflammatory response caused by bacteria colonizing near the pyloric antrum induces G cells in the antrum to secrete the hormone

''H. pylori'' infection is associated with

''H. pylori'' infection is associated with

In addition to using

In addition to using

gram-negative

Gram-negative bacteria are bacteria that, unlike gram-positive bacteria, do not retain the crystal violet stain used in the Gram staining method of bacterial differentiation. Their defining characteristic is that their cell envelope consists ...

, flagellated, helical bacterium. Mutants can have a rod or curved rod shape that exhibits less virulence

Virulence is a pathogen's or microorganism's ability to cause damage to a host.

In most cases, especially in animal systems, virulence refers to the degree of damage caused by a microbe to its host. The pathogenicity of an organism—its abili ...

. Its helical body (from which the genus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

name ''Helicobacter

''Helicobacter'' is a genus of gram-negative bacteria possessing a characteristic helical shape. They were initially considered to be members of the genus '' Campylobacter'', but in 1989, Goodwin ''et al.'' published sufficient reasons to justi ...

'' derives) is thought to have evolved to penetrate the mucous lining of the stomach

The stomach is a muscular, hollow organ in the upper gastrointestinal tract of Human, humans and many other animals, including several invertebrates. The Ancient Greek name for the stomach is ''gaster'' which is used as ''gastric'' in medical t ...

, helped by its flagella

A flagellum (; : flagella) (Latin for 'whip' or 'scourge') is a hair-like appendage that protrudes from certain plant and animal sperm cells, from fungal spores ( zoospores), and from a wide range of microorganisms to provide motility. Many pr ...

, and thereby establish infection. While many earlier reports of an association between bacteria and the ulcers had existed, such as the works of John Lykoudis, it was only in 1983 when the bacterium was formally described for the first time in the English-language Western literature as the causal agent of gastric ulcers by Australian physician-scientist

A physician-scientist (in North American English) or clinician-scientist (in British English and Australian English) is a physician who divides their professional time between direct clinical practice with patients and scientific research. Physicia ...

s Barry Marshall and Robin Warren

John Robin Warren (11 June 1937 – 23 July 2024) was an Australian pathologist, Nobel laureate, and researcher who is credited with the 1979 re-discovery of the bacterium '' Helicobacter pylori'', together with Barry Marshall. The duo pr ...

. In 2005, the pair was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine () is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single prize, but five separate prizes that, acco ...

for their discovery.

Infection of the stomach with ''H. pylori'' does not necessarily cause illness: over half of the global population is infected, but most individuals are asymptomatic. Persistent colonization

475px, Map of the year each country achieved List of sovereign states by date of formation, independence.

Colonization (British English: colonisation) is a process of establishing occupation of or control over foreign territories or peoples f ...

with more virulent strains can induce a number of gastric and non-gastric disorders. Gastric disorders due to infection begin with gastritis

Gastritis is the inflammation of the lining of the stomach. It may occur as a short episode or may be of a long duration. There may be no symptoms but, when symptoms are present, the most common is upper abdominal pain (see dyspepsia). Othe ...

, or inflammation of the stomach lining. When infection is persistent, the prolonged inflammation will become chronic gastritis. Initially, this will be non-atrophic gastritis, but the damage caused to the stomach lining can bring about the development of atrophic gastritis

Atrophic gastritis is a process of chronic inflammation of the gastric mucosa of the stomach, leading to a loss of gastric gland, gastric glandular cells and their eventual replacement by Intestinal metaplasia, intestinal and fibrous tissues. As ...

and ulcers within the stomach itself or the duodenum

The duodenum is the first section of the small intestine in most vertebrates, including mammals, reptiles, and birds. In mammals, it may be the principal site for iron absorption.

The duodenum precedes the jejunum and ileum and is the shortest p ...

(the nearest part of the intestine). At this stage, the risk of developing gastric cancer

Stomach cancer, also known as gastric cancer, is a malignant tumor of the stomach. It is a cancer that develops in the lining of the stomach. Most cases of stomach cancers are gastric carcinomas, which can be divided into a number of subtypes ...

is high. However, the development of a duodenal ulcer

Peptic ulcer disease is when the inner part of the stomach's gastric mucosa (lining of the stomach), the first part of the small intestine, or sometimes the lower esophagus, gets damaged. An ulcer in the stomach is called a gastric ulcer, while ...

confers a comparatively lower risk of cancer. ''Helicobacter pylori'' are class 1 carcinogenic bacteria, and potential cancers include gastric MALT lymphoma

MALT lymphoma (also called MALToma) is a form of lymphoma involving the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT), frequently of the stomach, but virtually any mucosal site can be affected. It is a cancer originating from B cells in the marginal zon ...

and gastric cancer

Stomach cancer, also known as gastric cancer, is a malignant tumor of the stomach. It is a cancer that develops in the lining of the stomach. Most cases of stomach cancers are gastric carcinomas, which can be divided into a number of subtypes ...

. Infection with ''H. pylori'' is responsible for an estimated 89% of all gastric cancers and is linked to the development of 5.5% of all cases cancers worldwide. ''H. pylori'' is the only bacterium known to cause cancer.

Extragastric complications that have been linked to ''H. pylori'' include anemia

Anemia (also spelt anaemia in British English) is a blood disorder in which the blood has a reduced ability to carry oxygen. This can be due to a lower than normal number of red blood cells, a reduction in the amount of hemoglobin availabl ...

due either to iron deficiency or vitamin B12 deficiency

Vitamin B12 deficiency, also known as cobalamin deficiency, is the medical condition in which the blood and tissue have a lower than normal level of Vitamin B12, vitamin B12. Symptoms can vary from none to severe. Mild deficiency may have fe ...

, diabetes mellitus

Diabetes mellitus, commonly known as diabetes, is a group of common endocrine diseases characterized by sustained hyperglycemia, high blood sugar levels. Diabetes is due to either the pancreas not producing enough of the hormone insulin, or th ...

, cardiovascular illness, and certain neurological disorders. An inverse association has also been claimed with ''H. pylori'' having a positive protective effect against asthma

Asthma is a common long-term inflammatory disease of the airways of the lungs. It is characterized by variable and recurring symptoms, reversible airflow obstruction, and easily triggered bronchospasms. Symptoms include episodes of wh ...

, esophageal cancer

Esophageal cancer (American English) or oesophageal cancer (British English) is cancer arising from the esophagus—the food pipe that runs between the throat and the stomach. Symptoms often include dysphagia, difficulty in swallowing and weigh ...

, inflammatory bowel disease

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a group of inflammatory conditions of the colon and small intestine, with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis (UC) being the principal types. Crohn's disease affects the small intestine and large intestine ...

(including gastroesophageal reflux disease

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) or gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) is a chronic upper gastrointestinal disease in which stomach content persistently and regularly flows up into the esophagus, resulting in symptoms and/or ...

and Crohn's disease

Crohn's disease is a type of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) that may affect any segment of the gastrointestinal tract. Symptoms often include abdominal pain, diarrhea, fever, abdominal distension, and weight loss. Complications outside of the ...

), and others.

Some studies suggest that ''H. pylori'' plays an important role in the natural stomach ecology by influencing the type of bacteria that colonize the gastrointestinal tract. Other studies suggest that non-pathogenic strains of ''H. pylori'' may beneficially normalize stomach acid secretion, and regulate appetite.

In 2023, it was estimated that about two-thirds of the world's population was infected with ''H. pylori'', being more common in developing countries

A developing country is a sovereign state with a less-developed Secondary sector of the economy, industrial base and a lower Human Development Index (HDI) relative to developed countries. However, this definition is not universally agreed upon. ...

. The prevalence has declined in many countries due to eradication treatments with antibiotics and proton-pump inhibitor

Proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) are a class of medications that cause a profound and prolonged reduction of gastric acid, stomach acid production. They do so by irreversibly inhibiting the stomach's H+/K+ ATPase, H+/K+ ATPase proton pump. The body ...

s, and with increased standards of living

Standard of living is the level of income, comforts and services available to an individual, community or society. A contributing factor to an individual's quality of life, standard of living is generally concerned with objective metrics outside ...

.

Microbiology

''Helicobacter pylori'' is a species ofgram-negative bacteria

Gram-negative bacteria are bacteria that, unlike gram-positive bacteria, do not retain the Crystal violet, crystal violet stain used in the Gram staining method of bacterial differentiation. Their defining characteristic is that their cell envelo ...

in the ''Helicobacter

''Helicobacter'' is a genus of gram-negative bacteria possessing a characteristic helical shape. They were initially considered to be members of the genus '' Campylobacter'', but in 1989, Goodwin ''et al.'' published sufficient reasons to justi ...

'' genus.

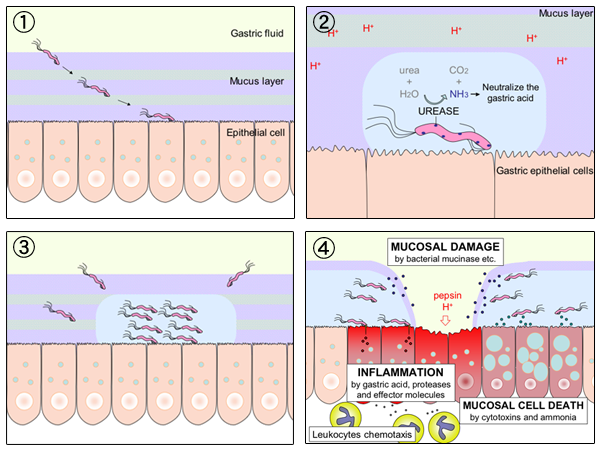

About half the world's population is infected with ''H. pylori'' but only a few strains are pathogenic

In biology, a pathogen (, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of"), in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a germ.

The term ...

. ''H pylori'' is a helical bacterium having a predominantly helical shape, also often described as having a spiral or ''S'' shape. Its helical shape is better suited for progressing through the viscous mucosa lining of the stomach, and is maintained by a number of enzymes

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as pro ...

in the cell wall's peptidoglycan

Peptidoglycan or murein is a unique large macromolecule, a polysaccharide, consisting of sugars and amino acids that forms a mesh-like layer (sacculus) that surrounds the bacterial cytoplasmic membrane. The sugar component consists of alternating ...

. The bacteria reach the less acidic mucosa by use of their flagella

A flagellum (; : flagella) (Latin for 'whip' or 'scourge') is a hair-like appendage that protrudes from certain plant and animal sperm cells, from fungal spores ( zoospores), and from a wide range of microorganisms to provide motility. Many pr ...

. Three strains studied showed a variation in length from 2.8 to 3.3 μm but a fairly constant diameter of 0.55–0.58 μm. ''H. pylori'' can convert from a helical to an inactive coccoid form that can evade the immune system, and that may possibly become viable, known as viable but nonculturable

Viable but nonculturable (VBNC) bacteria refers as to bacteria that are in a state of very low metabolic activity and do not divide, but are alive and have the ability to become culturable once resuscitated.

Bacteria in a VBNC state cannot grow on ...

(VBNC).

''Helicobacter pylori'' is microaerophilic

A microaerophile is a microorganism that requires environments containing lower levels of dioxygen than that are present in the atmosphere (i.e. < 21% O2; typically 2–10% O2) for optimal growth. A more r ...

– that is, it requires oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

, but at lower concentration than in the atmosphere

An atmosphere () is a layer of gases that envelop an astronomical object, held in place by the gravity of the object. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. A stellar atmosph ...

. It contains a hydrogenase

A hydrogenase is an enzyme that Catalysis, catalyses the reversible Redox, oxidation of molecular hydrogen (H2), as shown below:

Hydrogen oxidation () is coupled to the reduction of electron acceptors such as oxygen, nitrate, Ferric, ferric i ...

that can produce energy by oxidizing molecular hydrogen

Hydrogen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol H and atomic number 1. It is the lightest and abundance of the chemical elements, most abundant chemical element in the universe, constituting about 75% of all baryon, normal matter ...

(H2) made by intestinal bacteria.

''H. pylori'' can be demonstrated in tissue by Gram stain

Gram stain (Gram staining or Gram's method), is a method of staining used to classify bacterial species into two large groups: gram-positive bacteria and gram-negative bacteria. It may also be used to diagnose a fungal infection. The name comes ...

, Giemsa stain

Giemsa stain (), named after German chemist and bacteriologist Gustav Giemsa, is a nucleic acid stain used in cytogenetics and for the histopathological diagnosis of malaria and other parasites.

Uses

It is specific for the phosphate groups o ...

, H&E stain

Hematoxylin and eosin stain ( or haematoxylin and eosin stain or hematoxylin–eosin stain; often abbreviated as H&E stain or HE stain) is one of the principal tissue stains used in histology. It is the most widely used stain in medical diag ...

, Warthin-Starry silver stain, acridine orange stain, and phase-contrast microscopy

__NOTOC__

Phase-contrast microscopy (PCM) is an optical microscopy technique that converts phase shifts in light passing through a transparent specimen to brightness changes in the image. Phase shifts themselves are invisible, but become visibl ...

. It is capable of forming biofilm

A biofilm is a Syntrophy, syntrophic Microbial consortium, community of microorganisms in which cell (biology), cells cell adhesion, stick to each other and often also to a surface. These adherent cells become embedded within a slimy ext ...

s. Biofilms help to hinder the action of antibiotics and can contribute to treatment failure.

To successfully colonize its host, ''H. pylori'' uses many different virulence factor

Virulence factors (preferably known as pathogenicity factors or effectors in botany) are cellular structures, molecules and regulatory systems that enable microbial pathogens (bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoa) to achieve the following:

* c ...

s including oxidase

In biochemistry, an oxidase is an oxidoreductase (any enzyme that catalyzes a redox reaction) that uses dioxygen (O2) as the electron acceptor. In reactions involving donation of a hydrogen atom, oxygen is reduced to water (H2O) or hydrogen peroxid ...

, catalase

Catalase is a common enzyme found in nearly all living organisms exposed to oxygen (such as bacteria, plants, and animals) which catalyzes the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide to water and oxygen. It is a very important enzyme in protecting ...

, and urease

Ureases (), functionally, belong to the superfamily of amidohydrolases and phosphotriesterases. Ureases are found in numerous Bacteria, Archaea, fungi, algae, plants, and some invertebrates. Ureases are nickel-containing metalloenzymes of high ...

. Urease is the most abundant protein, its expression representing about 10% of the total protein weight.

''H. pylori'' possesses five major outer membrane protein families. The largest family includes known and putative adhesins. The other four families are porins, iron transporters, flagellum

A flagellum (; : flagella) (Latin for 'whip' or 'scourge') is a hair-like appendage that protrudes from certain plant and animal sperm cells, from fungal spores ( zoospores), and from a wide range of microorganisms to provide motility. Many pr ...

-associated proteins, and proteins of unknown function. Like other typical gram-negative bacteria, the outer membrane of ''H. pylori'' consists of phospholipids

Phospholipids are a class of lipids whose molecule has a hydrophilic "head" containing a phosphate group and two hydrophobic "tails" derived from fatty acids, joined by an alcohol residue (usually a glycerol molecule). Marine phospholipids typi ...

and lipopolysaccharide

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), now more commonly known as endotoxin, is a collective term for components of the outermost membrane of the cell envelope of gram-negative bacteria, such as '' E. coli'' and ''Salmonella'' with a common structural archit ...

(LPS). The O-antigen of LPS may be fucosylated and mimic Lewis blood group antigens found on the gastric epithelium.

Genome

''Helicobacter pylori'' consists of a large diversity of strains, and hundreds ofgenome

A genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as ...

s have been completely sequenced

In genetics and biochemistry, sequencing means to determine the primary structure (sometimes incorrectly called the primary sequence) of an unbranched biopolymer. Sequencing results in a symbolic linear depiction known as a sequence which succi ...

. The genome of the strain ''26695'' consists of about 1.7 million base pair

A base pair (bp) is a fundamental unit of double-stranded nucleic acids consisting of two nucleobases bound to each other by hydrogen bonds. They form the building blocks of the DNA double helix and contribute to the folded structure of both DNA ...

s, with some 1,576 genes. The pan-genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a pan-genome (pangenome or supragenome) is the entire set of genes from all strains within a clade. More generally, it is the union of all the genomes of a clade. The pan-genome can be broken do ...

, that is the combined set of 30 sequenced strains, encodes 2,239 protein families ( orthologous groups OGs). Among them, 1,248 OGs are conserved in all the 30 strains, and represent the universal core. The remaining 991 OGs correspond to the accessory genome in which 277 OGs are unique to one strain.

There are eleven restriction modification system

The restriction modification system (RM system) is found in bacteria and archaea, and provides a defense against foreign DNA, such as that borne by bacteriophages.

Bacteria have restriction enzymes, also called restriction endonucleases, which ...

s in the genome of ''H. pylori''. This is an unusually high number providing a defence against bacteriophages.

Transcriptome

Single-cell transcriptomics

Single-cell transcriptomics examines the gene expression level of individual Cell (biology), cells in a given population by simultaneously measuring the RNA concentration (conventionally only messenger RNA (mRNA)) of hundreds to thousands of genes. ...

using single-cell RNA-Seq gave the complete transcriptome

The transcriptome is the set of all RNA transcripts, including coding and non-coding, in an individual or a population of cells. The term can also sometimes be used to refer to all RNAs, or just mRNA, depending on the particular experiment. The ...

of ''H. pylori'' which was published in 2010. This analysis of its transcription confirmed the known acid induction of major virulence

Virulence is a pathogen's or microorganism's ability to cause damage to a host.

In most cases, especially in animal systems, virulence refers to the degree of damage caused by a microbe to its host. The pathogenicity of an organism—its abili ...

loci, including the urease (ure) operon and the Cag pathogenicity island (PAI). A total of 1,907 transcription start site

Transcription is the process of copying a segment of DNA into RNA for the purpose of gene expression. Some segments of DNA are transcribed into RNA molecules that can encode proteins, called messenger RNA (mRNA). Other segments of DNA are transc ...

s 337 primary operon

In genetics, an operon is a functioning unit of DNA containing a cluster of genes under the control of a single promoter. The genes are transcribed together into an mRNA strand and either translated together in the cytoplasm, or undergo splic ...

s, and 126 additional suboperons, and 66 monocistron

A cistron is a region of DNA that is conceptually equivalent to some definitions of a gene, such that the terms are synonymous from certain viewpoints, especially with regard to the molecular gene as contrasted with the Mendelian gene. The quest ...

s were identified. Until 2010, only about 55 transcription start sites (TSSs) were known in this species. 27% of the primary TSSs are also antisense TSSs, indicating that – similar to '' E. coli'' – antisense transcription occurs across the entire ''H. pylori'' genome. At least one antisense TSS is associated with about 46% of all open reading frame

In molecular biology, reading frames are defined as spans of DNA sequence between the start and stop codons. Usually, this is considered within a studied region of a prokaryotic DNA sequence, where only one of the six possible reading frames ...

s, including many housekeeping gene

In molecular biology, housekeeping genes are typically constitutive genes that are required for the maintenance of basic cellular function, and are expressed in all cells of an organism under normal and patho-physiological conditions. Although ...

s. About 50% of the 5 UTRs (leader sequences) are 20–40 nucleotides (nt) in length and support the AAGGag motif located about 6 nt (median distance) upstream of start codons as the consensus Shine–Dalgarno sequence

The Shine–Dalgarno (SD) sequence is, sometimes partially, part of a ribosomal binding site in bacterial and archaeal messenger RNA. It is generally located around 8 bases upstream of the start codon AUG. The RNA sequence helps recruit the ribos ...

in ''H. pylori''.

Proteome

Theproteome

A proteome is the entire set of proteins that is, or can be, expressed by a genome, cell, tissue, or organism at a certain time. It is the set of expressed proteins in a given type of cell or organism, at a given time, under defined conditions. P ...

of ''H. pylori'' has been systematically analyzed and more than 70% of its protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residue (biochemistry), residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including Enzyme catalysis, catalysing metab ...

s have been detected by mass spectrometry

Mass spectrometry (MS) is an analytical technique that is used to measure the mass-to-charge ratio of ions. The results are presented as a ''mass spectrum'', a plot of intensity as a function of the mass-to-charge ratio. Mass spectrometry is used ...

, and other methods. About 50% of the proteome has been quantified, informing of the number of protein copies in a typical cell.

Studies of the interactome

In molecular biology, an interactome is the whole set of molecular interactions in a particular cell. The term specifically refers to physical interactions among molecules (such as those among proteins, also known as protein–protein interactions ...

have identified more than 3000 protein-protein interactions. This has provided information of how proteins interact with each other, either in stable protein complex

A protein complex or multiprotein complex is a group of two or more associated polypeptide chains. Protein complexes are distinct from multidomain enzymes, in which multiple active site, catalytic domains are found in a single polypeptide chain.

...

es or in more dynamic, transient interactions, which can help to identify the functions of the protein. This in turn helps researchers to find out what the function of uncharacterized proteins is, e.g. when an uncharacterized protein interacts with several proteins of the ribosome

Ribosomes () are molecular machine, macromolecular machines, found within all cell (biology), cells, that perform Translation (biology), biological protein synthesis (messenger RNA translation). Ribosomes link amino acids together in the order s ...

(that is, it is likely also involved in ribosome function). About a third of all ~1,500 proteins in ''H. pylori'' remain uncharacterized and their function is largely unknown.

Infection

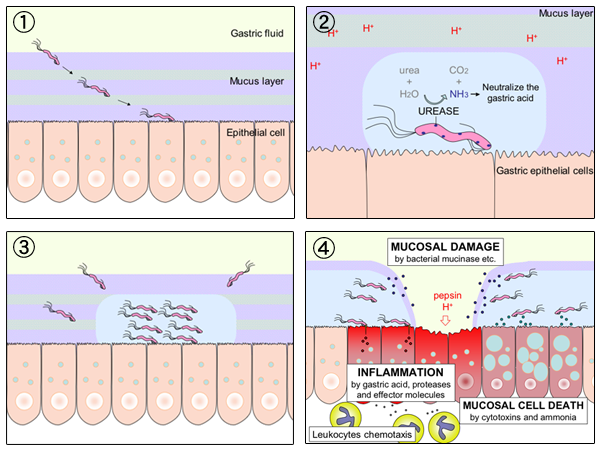

An infection with ''Helicobacter pylori'' can either have no symptoms even when lasting a lifetime, or can harm the stomach and duodenal linings by inflammatory responses induced by several mechanisms associated with a number of

An infection with ''Helicobacter pylori'' can either have no symptoms even when lasting a lifetime, or can harm the stomach and duodenal linings by inflammatory responses induced by several mechanisms associated with a number of virulence factor

Virulence factors (preferably known as pathogenicity factors or effectors in botany) are cellular structures, molecules and regulatory systems that enable microbial pathogens (bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoa) to achieve the following:

* c ...

s. Colonization

475px, Map of the year each country achieved List of sovereign states by date of formation, independence.

Colonization (British English: colonisation) is a process of establishing occupation of or control over foreign territories or peoples f ...

can initially cause ''H. pylori induced gastritis'', an inflammation of the stomach lining that became a listed disease in ICD11. This will progress to chronic gastritis if left untreated. Chronic gastritis may lead to atrophy

Atrophy is the partial or complete wasting away of a part of the body. Causes of atrophy include mutations (which can destroy the gene to build up the organ), malnutrition, poor nourishment, poor circulatory system, circulation, loss of hormone, ...

of the stomach lining, and the development of peptic ulcer

Peptic ulcer disease is when the inner part of the stomach's gastric mucosa (lining of the stomach), the first part of the small intestine, or sometimes the lower esophagus, gets damaged. An ulcer in the stomach is called a gastric ulcer, while ...

s (gastric or duodenal). These changes may be seen as stages in the development of gastric cancer

Stomach cancer, also known as gastric cancer, is a malignant tumor of the stomach. It is a cancer that develops in the lining of the stomach. Most cases of stomach cancers are gastric carcinomas, which can be divided into a number of subtypes ...

, known as ''Correa's cascade''. Extragastric complications that have been linked to ''H. pylori'' include anemia

Anemia (also spelt anaemia in British English) is a blood disorder in which the blood has a reduced ability to carry oxygen. This can be due to a lower than normal number of red blood cells, a reduction in the amount of hemoglobin availabl ...

due either to iron-deficiency or vitamin B12 deficiency, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular, and certain neurological disorders.

Peptic ulcers are a consequence of inflammation that allows stomach acid and the digestive enzyme pepsin

Pepsin is an endopeptidase that breaks down proteins into smaller peptides and amino acids. It is one of the main digestive enzymes in the digestive systems of humans and many other animals, where it helps digest the proteins in food. Pe ...

to overwhelm the protective mechanisms of the mucous membranes

A mucous membrane or mucosa is a membrane that lines various cavities in the body of an organism and covers the surface of internal organs. It consists of one or more layers of epithelial cells overlying a layer of loose connective tissue. It is ...

. The location of colonization of ''H. pylori'', which affects the location of the ulcer, depends on the acidity of the stomach. In people producing large amounts of acid, ''H. pylori'' colonizes near the pyloric antrum

The pylorus ( or ) connects the stomach to the duodenum. The pylorus is considered as having two parts, the ''pyloric antrum'' (opening to the body of the stomach) and the ''pyloric canal'' (opening to the duodenum). The ''pyloric canal'' ends a ...

(exit to the duodenum) to avoid the acid-secreting parietal cells

Parietal cells (also known as oxyntic cells) are epithelial cells in the stomach that secrete hydrochloric acid (HCl) and intrinsic factor. These cells are located in the gastric glands found in the lining of the fundus and body regions o ...

at the fundus (near the entrance to the stomach). G cell

A G cell or gastrin cell is a type of cell in the stomach and duodenum that secretes gastrin. It works in conjunction with gastric chief cells and parietal cells. G cells are found deep within the pyloric glands of the stomach antrum, and occasi ...

s express relatively high levels of PD-L1

Programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) also known as cluster of differentiation 274 (CD274) or B7 homolog 1 (B7-H1) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''CD274'' gene.

Programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) is a 40kDa type 1 transmembrane prote ...

that protects these cells from ''H. pylori''-induced immune destruction. In people producing normal or reduced amounts of acid, ''H. pylori'' can also colonize the rest of the stomach.

The inflammatory response caused by bacteria colonizing near the pyloric antrum induces G cells in the antrum to secrete the hormone

The inflammatory response caused by bacteria colonizing near the pyloric antrum induces G cells in the antrum to secrete the hormone gastrin

Gastrin is a peptide hormone that stimulates secretion of gastric acid (HCl) by the parietal cells of the stomach and aids in gastric motility. It is released by G cells in the pyloric antrum of the stomach, duodenum, and the pancreas.

...

, which travels through the bloodstream to parietal cells in the fundus. Gastrin stimulates the parietal cells to secrete more acid into the stomach lumen, and over time increases the number of parietal cells, as well. The increased acid load damages the duodenum, which may eventually lead to the formation of ulcers.

''Helicobacter pylori'' is a class I carcinogen

A carcinogen () is any agent that promotes the development of cancer. Carcinogens can include synthetic chemicals, naturally occurring substances, physical agents such as ionizing and non-ionizing radiation, and biologic agents such as viruse ...

, and potential cancers include gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue

The mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT), also called mucosa-associated lymphatic tissue, is a diffuse system of small concentrations of lymphoid tissue found in various submucosal membrane sites of the body, such as the gastrointestinal t ...

(MALT) lymphoma

Lymphoma is a group of blood and lymph tumors that develop from lymphocytes (a type of white blood cell). The name typically refers to just the cancerous versions rather than all such tumours. Signs and symptoms may include enlarged lymph node ...

s and gastric cancer

Stomach cancer, also known as gastric cancer, is a malignant tumor of the stomach. It is a cancer that develops in the lining of the stomach. Most cases of stomach cancers are gastric carcinomas, which can be divided into a number of subtypes ...

. Less commonly, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is a cancer of B cells, a type of lymphocyte that is responsible for producing antibodies. It is the most common form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma among adults, with an annual incidence of 7–8 cases per 100,000 ...

of the stomach is a risk. Infection with ''H. pylori'' is responsible for around 89 per cent of all gastric cancers, and is linked to the development of 5.5 per cent of all cases of cancer worldwide. Although the data varies between different countries, overall about 1% to 3% of people infected with ''Helicobacter pylori'' develop gastric cancer in their lifetime compared to 0.13% of individuals who have had no ''H. pylori'' infection. ''H. pylori''-induced gastric cancer is the third highest cause of worldwide cancer mortality as of 2018. Because of the usual lack of symptoms, when gastric cancer is finally diagnosed it is often fairly advanced. More than half of gastric cancer patients have lymph node metastasis when they are initially diagnosed.

Chronic inflammation that is a feature of cancer development is characterized by infiltration of neutrophil

Neutrophils are a type of phagocytic white blood cell and part of innate immunity. More specifically, they form the most abundant type of granulocytes and make up 40% to 70% of all white blood cells in humans. Their functions vary in differe ...

s and macrophage

Macrophages (; abbreviated MPhi, φ, MΦ or MP) are a type of white blood cell of the innate immune system that engulf and digest pathogens, such as cancer cells, microbes, cellular debris and foreign substances, which do not have proteins that ...

s to the gastric epithelium, which favors the accumulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, reactive oxygen species

In chemistry and biology, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are highly Reactivity (chemistry), reactive chemicals formed from diatomic oxygen (), water, and hydrogen peroxide. Some prominent ROS are hydroperoxide (H2O2), superoxide (O2−), hydroxyl ...

(ROS) and reactive nitrogen species

Reactive nitrogen species (RNS) are a family of antimicrobial molecules derived from nitric oxide (•NO) and superoxide (O2•−) produced via the enzymatic activity of inducible nitric oxide synthase 2 (Nitric oxide synthase 2A, NOS2) and NADPH ...

(RNS) that cause DNA damage

DNA repair is a collection of processes by which a cell identifies and corrects damage to the DNA molecules that encode its genome. A weakened capacity for DNA repair is a risk factor for the development of cancer. DNA is constantly modified ...

. The oxidative DNA damage and levels of oxidative stress

Oxidative stress reflects an imbalance between the systemic manifestation of reactive oxygen species and a biological system's ability to readily detoxify the reactive intermediates or to repair the resulting damage. Disturbances in the normal ...

can be indicated by a biomarker, 8-oxo-dG. Other damage to DNA includes double-strand break

DNA repair is a collection of processes by which a cell identifies and corrects damage to the DNA molecules that encode its genome. A weakened capacity for DNA repair is a risk factor for the development of cancer. DNA is constantly modified ...

s.

Small gastric

The stomach is a muscular, hollow organ in the upper gastrointestinal tract of humans and many other animals, including several invertebrates. The Ancient Greek name for the stomach is ''gaster'' which is used as ''gastric'' in medical terms re ...

and colorectal polyp

A colorectal polyp is a polyp (fleshy growth) occurring on the lining of the colon or rectum. Untreated colorectal polyps can develop into colorectal cancer.

Colorectal polyps are often classified by their behaviour (i.e. benign vs. malignant) ...

s are adenoma

An adenoma is a benign tumor of epithelium, epithelial tissue with glandular origin, glandular characteristics, or both. Adenomas can grow from many glandular organ (anatomy), organs, including the adrenal glands, pituitary gland, thyroid, prosta ...

s that are more commonly found in association with the mucosal damage induced by ''H. pylori'' gastritis. Larger polyps can in time become cancerous. A modest association of ''H. pylori'' has been made with the development of colorectal cancer

Colorectal cancer (CRC), also known as bowel cancer, colon cancer, or rectal cancer, is the development of cancer from the Colon (anatomy), colon or rectum (parts of the large intestine). Signs and symptoms may include Lower gastrointestinal ...

s, but as of 2020 causality had yet to be proved.

Signs and symptoms

Most people infected with ''H. pylori'' never experience any symptoms or complications, but will have a 10% to 20% risk of developingpeptic ulcer

Peptic ulcer disease is when the inner part of the stomach's gastric mucosa (lining of the stomach), the first part of the small intestine, or sometimes the lower esophagus, gets damaged. An ulcer in the stomach is called a gastric ulcer, while ...

s or a 0.5% to 2% risk of stomach cancer. ''H. pylori induced gastritis'' may present as acute gastritis with stomach ache, nausea

Nausea is a diffuse sensation of unease and discomfort, sometimes perceived as an urge to vomit. It can be a debilitating symptom if prolonged and has been described as placing discomfort on the chest, abdomen, or back of the throat.

Over 30 d ...

, and ongoing dyspepsia

Indigestion, also known as dyspepsia or upset stomach, is a condition of impaired digestion. Symptoms may include upper abdominal fullness, heartburn, nausea, belching, or upper abdominal pain. People may also experience feeling full earlier ...

(indigestion) that is sometimes accompanied by depression and anxiety. Where the gastritis develops into chronic gastritis, or an ulcer, the symptoms are the same and can include indigestion

Indigestion, also known as dyspepsia or upset stomach, is a condition of impaired digestion. Symptoms may include upper abdominal fullness, heartburn, nausea, belching, or upper abdominal pain. People may also experience feeling full earlier ...

, stomach or abdominal pains, nausea, bloating

Abdominal bloating (or simply bloating) is a short-term disease that affects the gastrointestinal tract. Bloating is generally characterized by an excess buildup of gas, air or fluids in the stomach. A person may have feelings of tightness, pressu ...

, belching, feeling hunger in the morning, feeling full too soon, and sometimes vomiting

Vomiting (also known as emesis, puking and throwing up) is the forceful expulsion of the contents of one's stomach through the mouth and sometimes the nose.

Vomiting can be the result of ailments like food poisoning, gastroenteritis, pre ...

, heartburn, bad breath, and weight loss.

Complications of an ulcer can cause severe signs and symptoms such as black or tarry stool indicative of bleeding

Bleeding, hemorrhage, haemorrhage or blood loss, is blood escaping from the circulatory system from damaged blood vessels. Bleeding can occur internally, or externally either through a natural opening such as the mouth, nose, ear, urethr ...

into the stomach or duodenum; blood - either red or coffee-ground colored in vomit; persistent sharp or severe abdominal pain; dizziness, and a fast heartbeat. Bleeding is the most common complication. In cases caused by ''H. pylori'' there was a greater need for hemostasis

In biology, hemostasis or haemostasis is a process to prevent and stop bleeding, meaning to keep blood within a damaged blood vessel (the opposite of hemostasis is hemorrhage). It is the first stage of wound healing. Hemostasis involves three ...

often requiring gastric resection. Prolonged bleeding may cause anemia leading to weakness and fatigue. Inflammation of the pyloric antrum, which connects the stomach to the duodenum, is more likely to lead to duodenal ulcers, while inflammation of the corpus

Corpus (plural ''corpora'') is Latin for "body". It may refer to:

Linguistics

* Text corpus, in linguistics, a large and structured set of texts

* Speech corpus, in linguistics, a large set of speech audio files

* Corpus linguistics, a branch of ...

may lead to a gastric ulcer.

Stomach cancer

Stomach cancer, also known as gastric cancer, is a malignant tumor of the stomach. It is a cancer that develops in the Gastric mucosa, lining of the stomach. Most cases of stomach cancers are gastric carcinomas, which can be divided into a numb ...

can cause nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, constipation, and unexplained weight loss. Gastric polyps are adenoma

An adenoma is a benign tumor of epithelium, epithelial tissue with glandular origin, glandular characteristics, or both. Adenomas can grow from many glandular organ (anatomy), organs, including the adrenal glands, pituitary gland, thyroid, prosta ...

s that are usually asymptomatic and benign, but may be the cause of dyspepsia, heartburn, bleeding from the stomach, and, rarely, gastric outlet obstruction. Larger polyps may have become cancerous.

Colorectal polyp

A colorectal polyp is a polyp (fleshy growth) occurring on the lining of the colon or rectum. Untreated colorectal polyps can develop into colorectal cancer.

Colorectal polyps are often classified by their behaviour (i.e. benign vs. malignant) ...

s may be the cause of rectal bleeding, anemia, constipation, diarrhea, weight loss, and abdominal pain.

Pathophysiology

Virulence factor

Virulence factors (preferably known as pathogenicity factors or effectors in botany) are cellular structures, molecules and regulatory systems that enable microbial pathogens (bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoa) to achieve the following:

* c ...

s help a pathogen to evade the immune response of the host, and to successfully colonize. The many virulence factors of ''H. pylori'' include its flagella, the production of urease, adhesins, serine protease

Serine proteases (or serine endopeptidases) are enzymes that cleave peptide bonds in proteins. Serine serves as the nucleophilic amino acid at the (enzyme's) active site.

They are found ubiquitously in both eukaryotes and prokaryotes. Serin ...

HtrA (high temperature requirement A), and the major exotoxin

An exotoxin is a toxin secreted by bacteria. An exotoxin can cause damage to the host by destroying cells or disrupting normal cellular metabolism. They are highly potent and can cause major damage to the host. Exotoxins may be secreted, or, sim ...

s CagA and VacA. The presence of VacA and CagA are associated with more advanced outcomes. CagA is an oncoprotein associated with the development of gastric cancer.

''H. pylori'' infection is associated with

''H. pylori'' infection is associated with epigenetically

In biology, epigenetics is the study of changes in gene expression that happen without changes to the DNA sequence. The Greek prefix ''epi-'' (ἐπι- "over, outside of, around") in ''epigenetics'' implies features that are "on top of" or "in ...

reduced efficiency of the DNA repair

DNA repair is a collection of processes by which a cell (biology), cell identifies and corrects damage to the DNA molecules that encode its genome. A weakened capacity for DNA repair is a risk factor for the development of cancer. DNA is cons ...

machinery, which favors the accumulation of mutations and genomic instability as well as gastric carcinogenesis. It has been shown that expression of two DNA repair proteins, ERCC1

DNA excision repair protein ERCC-1 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''ERCC1'' gene. Together with ERCC4, ERCC1 forms the ERCC1-XPF enzyme complex that participates in DNA repair and DNA recombination.

Many aspects of these two gen ...

and PMS2, was severely reduced once ''H. pylori'' infection had progressed to cause dyspepsia

Indigestion, also known as dyspepsia or upset stomach, is a condition of impaired digestion. Symptoms may include upper abdominal fullness, heartburn, nausea, belching, or upper abdominal pain. People may also experience feeling full earlier ...

. Dyspepsia occurs in about 20% of infected individuals. Epigenetically reduced protein expression of DNA repair proteins MLH1

DNA mismatch repair protein Mlh1 or MutL protein homolog 1 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''MLH1'' gene located on chromosome 3. The gene is commonly associated with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Orthologs of human ...

, MGMT

MGMT () is an American rock band formed in 2002 in Middletown, Connecticut. It was founded by singers and multi-instrumentalists Andrew VanWyngarden and Benjamin Goldwasser, Ben Goldwasser.

Originally signed to Cantora Records by the nascent ...

and MRE11 are also evident. Reduced DNA repair in the presence of increased DNA damage increases carcinogenic mutations and is likely a significant cause of gastric carcinogenesis. These epigenetic alterations are due to ''H. pylori''-induced methylation of CpG sites in promoters of genes and ''H. pylori''-induced altered expression of multiple microRNA

Micro ribonucleic acid (microRNA, miRNA, μRNA) are small, single-stranded, non-coding RNA molecules containing 21–23 nucleotides. Found in plants, animals, and even some viruses, miRNAs are involved in RNA silencing and post-transcr ...

s.

Two related mechanisms by which ''H. pylori'' could promote cancer have been proposed. One mechanism involves the enhanced production of free radical

A daughter category of ''Ageing'', this category deals only with the biological aspects of ageing.

Ageing

Biogerontology

Biological processes

Causes of death

Cellular processes

Gerontology

Life extension

Metabolic disorders

Metabolism

...

s near ''H. pylori'' and an increased rate of host cell mutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, ...

. The other proposed mechanism has been called a "perigenetic pathway", and involves enhancement of the transformed host cell phenotype by means of alterations in cell proteins, such as adhesion

Adhesion is the tendency of dissimilar particles or interface (matter), surfaces to cling to one another. (Cohesion (chemistry), Cohesion refers to the tendency of similar or identical particles and surfaces to cling to one another.)

The ...

proteins. ''H. pylori'' has been proposed to induce inflammation and locally high levels of tumor necrosis factor

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF), formerly known as TNF-α, is a chemical messenger produced by the immune system that induces inflammation. TNF is produced primarily by activated macrophages, and induces inflammation by binding to its receptors o ...

(TNF), also known as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα)), and/or interleukin 6

Interleukin 6 (IL-6) is an interleukin that acts as both a pro-inflammatory cytokine and an anti-inflammatory myokine. In humans, it is encoded by the ''IL6'' gene.

In addition, osteoblasts secrete IL-6 to stimulate osteoclast formation. Smoo ...

(IL-6). According to the proposed perigenetic mechanism, inflammation-associated signaling molecules, such as TNF, can alter gastric epithelial cell adhesion and lead to the dispersion and migration of mutated epithelial cells without the need for additional mutations in tumor suppressor gene

A tumor suppressor gene (TSG), or anti-oncogene, is a gene that regulates a cell (biology), cell during cell division and replication. If the cell grows uncontrollably, it will result in cancer. When a tumor suppressor gene is mutated, it results ...

s, such as genes that code for cell adhesion proteins.

Flagellum

The first virulence factor of ''Helicobacter pylori'' that enables colonization is itsflagellum

A flagellum (; : flagella) (Latin for 'whip' or 'scourge') is a hair-like appendage that protrudes from certain plant and animal sperm cells, from fungal spores ( zoospores), and from a wide range of microorganisms to provide motility. Many pr ...

. ''H. pylori'' has from two to seven flagella at the same polar location which gives it a high motility. The flagellar filaments are about 3 μm long, and composed of two copolymerized flagellin

Flagellins are a family of proteins present in flagellated bacteria which arrange themselves in a hollow cylinder to form the filament in a bacterial flagellum. Flagellin has a mass on average of about 40,000 daltons. Flagellins are the princi ...

s, FlaA and FlaB, coded by the genes ''flaA'', and ''flaB''. The minor flagellin FlaB is located in the proximal region and the major flagellin FlaA makes up the rest of the flagellum. The flagella are sheathed in a continuation of the bacterial outer membrane which gives protection against the gastric acidity. The sheath is also the location of the origin of the outer membrane vesicles that gives protection to the bacterium from bacteriophages.

Flagella motility is provided by the proton motive force

Chemiosmosis is the movement of ions across a semipermeable membrane bound structure, down their electrochemical gradient. An important example is the formation of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) by the movement of hydrogen ions (H+) across a membra ...

provided by urease-driven hydrolysis allowing chemotactic movements towards the less acidic pH gradient in the mucosa. The mucus layer is about 300 μm thick, and the helical shape of ''H. pylori'' aided by its flagella helps it to burrow through this layer where it colonises a narrow region of about 25 μm closest to the epithelial cell layer, where the pH is near to neutral. They further colonise the gastric pits and live in the gastric glands. Occasionally the bacteria are found inside the epithelial cells themselves. The use of quorum sensing

In biology, quorum sensing or quorum signaling (QS) is the process of cell-to-cell communication that allows bacteria to detect and respond to cell population density by gene regulation, typically as a means of acclimating to environmental disadv ...

by the bacteria enables the formation of a biofilm which furthers persistent colonisation. In the layers of the biofilm, ''H. pylori'' can escape from the actions of antibiotics, and also be protected from host-immune responses. In the biofilm, ''H. pylori'' can change the flagella to become adhesive structures.

Urease

chemotaxis

Chemotaxis (from ''chemical substance, chemo-'' + ''taxis'') is the movement of an organism or entity in response to a chemical stimulus. Somatic cells, bacteria, and other single-cell organism, single-cell or multicellular organisms direct thei ...

to avoid areas of high acidity (low pH), ''H. pylori'' also produces large amounts of urease

Ureases (), functionally, belong to the superfamily of amidohydrolases and phosphotriesterases. Ureases are found in numerous Bacteria, Archaea, fungi, algae, plants, and some invertebrates. Ureases are nickel-containing metalloenzymes of high ...

, an enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

which breaks down the urea

Urea, also called carbamide (because it is a diamide of carbonic acid), is an organic compound with chemical formula . This amide has two Amine, amino groups (–) joined by a carbonyl functional group (–C(=O)–). It is thus the simplest am ...

present in the stomach to produce ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic chemical compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the chemical formula, formula . A Binary compounds of hydrogen, stable binary hydride and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinctive pu ...

and bicarbonate

In inorganic chemistry, bicarbonate (IUPAC-recommended nomenclature: hydrogencarbonate) is an intermediate form in the deprotonation of carbonic acid. It is a polyatomic anion with the chemical formula .

Bicarbonate serves a crucial bioche ...

, which are released into the bacterial cytosol and the surrounding environment, creating a neutral area. The decreased acidity (higher pH) changes the mucus layer from a gel-like state to a more viscous state that makes it easier for the flagella to move the bacteria through the mucosa and attach to the gastric epithelial cells. ''Helicobacter pylori'' is one of the few known types of bacterium that has a urea cycle

The urea cycle (also known as the ornithine cycle) is a cycle of biochemical reactions that produces urea (NH2)2CO from ammonia (NH3). Animals that use this cycle, mainly amphibians and mammals, are called ureotelic.

The urea cycle converts highl ...

which is uniquely configured in the bacterium. 10% of the cell is of nitrogen

Nitrogen is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a Nonmetal (chemistry), nonmetal and the lightest member of pnictogen, group 15 of the periodic table, often called the Pnictogen, pnictogens. ...

, a balance that needs to be maintained. Any excess is stored in urea excreted in the urea cycle.

A final stage enzyme in the urea cycle is arginase, an enzyme that is crucial to the pathogenesis of ''H. pylori''. Arginase produces ornithine

Ornithine is a non-proteinogenic α-amino acid that plays a role in the urea cycle. It is not incorporated into proteins during translation. Ornithine is abnormally accumulated in the body in ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency, a disorder of th ...

and urea, which the enzyme urease breaks down into carbonic acid and ammonia. Urease is the bacterium's most abundant protein, accounting for 10–15% of the bacterium's total protein content. Its expression is not only required for establishing initial colonization in the breakdown of urea to carbonic acid and ammonia, but is also essential for maintaining chronic infection. Ammonia reduces stomach acidity, allowing the bacteria to become locally established. Arginase promotes the persistence of infection by consuming arginine; arginine is used by macrophages to produce nitric oxide, which has a strong antimicrobial effect. The ammonia produced to regulate pH is toxic to epithelial cells.

Adhesins

''H. pylori'' must make attachment with the epithelial cells to prevent its being swept away with the constant movement and renewal of the mucus. To give them this adhesion, bacterial outer membrane proteins as virulence factors called adhesins are produced. BabA (blood group antigen binding adhesin) is most important during initial colonization, and SabA (sialic acid binding adhesin) is important in persistence. BabA attaches to glycans and mucins in the epithelium. BabA (coded for by the ''babA2'' gene) also binds to the Lewis b antigen displayed on the surface of the epithelial cells. Adherence via BabA is acid sensitive and can be fully reversed by a decreased pH. It has been proposed that BabA's acid responsiveness enables adherence while also allowing an effective escape from an unfavorable environment such as a low pH that is harmful to the organism. SabA (coded for by the ''sabA'' gene) binds to increased levels of sialyl-Lewis X antigen expressed on gastric mucosa.Cholesterol glucoside

The outer membrane contains ''cholesterol glucoside'', a sterol glucoside that ''H. pylori'' glycosylates from thecholesterol

Cholesterol is the principal sterol of all higher animals, distributed in body Tissue (biology), tissues, especially the brain and spinal cord, and in Animal fat, animal fats and oils.

Cholesterol is biosynthesis, biosynthesized by all anima ...

in the gastric gland cells, and inserts it into its outer membrane. This cholesterol glucoside is important for membrane stability, morphology and immune evasion, and is rarely found in other bacteria.

The enzyme responsible for this is ''cholesteryl α-glucosyltransferase'' (αCgT or Cgt), encoded by the ''HP0421'' gene. A major effect of the depletion of host cholesterol by Cgt is to disrupt cholesterol-rich lipid raft

The cell membrane, plasma membranes of cells contain combinations of glycosphingolipids, cholesterol and protein Receptor (biochemistry), receptors organized in glycolipoprotein lipid microdomains termed lipid rafts. Their existence in cellular me ...

s in the epithelial cells. Lipid rafts are involved in cell signalling and their disruption causes a reduction in the immune inflammatory response, particularly by reducing interferon gamma

Interferon gamma (IFNG or IFN-γ) is a dimerized soluble cytokine that is the only member of the type II class of interferons. The existence of this interferon, which early in its history was known as immune interferon, was described by E. F. ...

. Cgt is also secreted by the type IV secretion system, and is secreted in a selective way so that gastric niches where the pathogen can thrive are created. Its lack has been shown to give vulnerability from environmental stress to bacteria, and also to disrupt CagA-mediated interactions.

Catalase

Colonization induces an intense anti-inflammatory response as a first-line immune system defence. Phagocytic leukocytes and monocytes infiltrate the site of infection, and antibodies are produced. ''H. pylori'' is able to adhere to the surface of the phagocytes and impede their action. This is responded to by the phagocyte in the generation and release of oxygen metabolites into the surrounding space. ''H. pylori'' can survive this response by the activity ofcatalase

Catalase is a common enzyme found in nearly all living organisms exposed to oxygen (such as bacteria, plants, and animals) which catalyzes the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide to water and oxygen. It is a very important enzyme in protecting ...

at its attachment to the phagocytic cell surface. Catalase decomposes hydrogen peroxide into water and oxygen, protecting the bacteria from toxicity. Catalase has been shown to almost completely inhibit the phagocytic oxidative response. It is coded for by the gene ''katA''.

Tipα

TNF-inducing protein alpha (Tipα) is a carcinogenic protein encoded by ''HP0596'' unique to ''H. pylori'' that induces the expression oftumor necrosis factor

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF), formerly known as TNF-α, is a chemical messenger produced by the immune system that induces inflammation. TNF is produced primarily by activated macrophages, and induces inflammation by binding to its receptors o ...

. Tipα enters gastric cancer cells where it binds to cell surface nucleolin, and induces the expression of vimentin

Vimentin is a structural protein that in humans is encoded by the ''VIM'' gene. Its name comes from the Latin ''vimentum'' which refers to an array of flexible rods.

Vimentin is a Intermediate filament#Type III, type III intermediate filamen ...

. Vimentin is important in the epithelial–mesenchymal transition

The epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a process by which epithelial cells lose their cell polarity and cell–cell adhesion, and gain migratory and invasive properties to become mesenchymal stem cells; these are multipotent stromal ...

associated with the progression of tumors.

CagA

CagA (cytotoxin-associated antigen A) is a majorvirulence factor

Virulence factors (preferably known as pathogenicity factors or effectors in botany) are cellular structures, molecules and regulatory systems that enable microbial pathogens (bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoa) to achieve the following:

* c ...

for ''H. pylori'', an oncoprotein that is encoded by the ''cagA'' gene. Bacterial strains with the ''cagA'' gene are associated with the ability to cause ulcers, MALT lymphomas, and gastric cancer. The ''cagA'' gene codes for a relatively long (1186-amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although over 500 amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the 22 α-amino acids incorporated into proteins. Only these 22 a ...

) protein. The ''cag'' pathogenicity island (PAI) has about 30 genes, part of which code for a complex type IV secretion system (T4SS or TFSS). The low GC-content

In molecular biology and genetics, GC-content (or guanine-cytosine content) is the percentage of nitrogenous bases in a DNA or RNA molecule that are either guanine (G) or cytosine (C). This measure indicates the proportion of G and C bases out of ...

of the ''cag'' PAI relative to the rest of the ''Helicobacter'' genome suggests the island was acquired by horizontal transfer from another bacterial species. The serine protease

Serine proteases (or serine endopeptidases) are enzymes that cleave peptide bonds in proteins. Serine serves as the nucleophilic amino acid at the (enzyme's) active site.

They are found ubiquitously in both eukaryotes and prokaryotes. Serin ...

HtrA also plays a major role in the pathogenesis of ''H. pylori''. The HtrA protein enables the bacterium to transmigrate across the host cells' epithelium, and is also needed for the translocation of CagA.

The virulence of ''H. pylori'' may be increased by genes of the ''cag'' pathogenicity island; about 50–70% of ''H. pylori'' strains in Western countries carry it. Western people infected with strains carrying the ''cag'' PAI have a stronger inflammatory response in the stomach and are at a greater risk of developing peptic ulcers or stomach cancer than those infected with strains lacking the island. Following attachment of ''H. pylori'' to stomach epithelial cells, the type IV secretion system expressed by the ''cag'' PAI "injects" the inflammation

Inflammation (from ) is part of the biological response of body tissues to harmful stimuli, such as pathogens, damaged cells, or irritants. The five cardinal signs are heat, pain, redness, swelling, and loss of function (Latin ''calor'', '' ...

-inducing agent, peptidoglycan, from their own cell wall

A cell wall is a structural layer that surrounds some Cell type, cell types, found immediately outside the cell membrane. It can be tough, flexible, and sometimes rigid. Primarily, it provides the cell with structural support, shape, protection, ...

s into the epithelial cells. The injected peptidoglycan is recognized by the cytoplasmic pattern recognition receptor (immune sensor) Nod1, which then stimulates expression of cytokines

Cytokines () are a broad and loose category of small proteins (~5–25 kDa) important in cell signaling.

Cytokines are produced by a broad range of cells, including immune cells like macrophages, B cell, B lymphocytes, T cell, T lymphocytes ...

that promote inflammation.

The type-IV secretion

Secretion is the movement of material from one point to another, such as a secreted chemical substance from a cell or gland. In contrast, excretion is the removal of certain substances or waste products from a cell or organism. The classical mec ...

apparatus also injects the ''cag'' PAI-encoded protein CagA into the stomach's epithelial cells, where it disrupts the cytoskeleton

The cytoskeleton is a complex, dynamic network of interlinking protein filaments present in the cytoplasm of all cells, including those of bacteria and archaea. In eukaryotes, it extends from the cell nucleus to the cell membrane and is compos ...

, adherence to adjacent cells, intracellular signaling, cell polarity

Cell polarity refers to spatial differences in shape, structure, and function within a cell. Almost all cell types exhibit some form of polarity, which enables them to carry out specialized functions. Classical examples of polarized cells are de ...

, and other cellular activities. Once inside the cell, the CagA protein is phosphorylated

In biochemistry, phosphorylation is described as the "transfer of a phosphate group" from a donor to an acceptor. A common phosphorylating agent (phosphate donor) is ATP and a common family of acceptor are alcohols:

:

This equation can be writt ...

on tyrosine residues by a host cell membrane-associated tyrosine kinase

A tyrosine kinase is an enzyme that can transfer a phosphate group from ATP to the tyrosine residues of specific proteins inside a cell. It functions as an "on" or "off" switch in many cellular functions.

Tyrosine kinases belong to a larger cla ...

(TK). CagA then allosterically activates protein tyrosine phosphatase

Protein tyrosine phosphatases (EC 3.1.3.48, systematic name protein-tyrosine-phosphate phosphohydrolase) are a group of enzymes that remove phosphate groups from phosphorylated tyrosine residues on proteins:

: proteintyrosine phosphate + H2O = ...

/ protooncogene Shp2

Tyrosine-protein phosphatase non-receptor type 11 (PTPN11) also known as protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1D (PTP-1D), Src homology region 2 domain-containing phosphatase-2 (SHP-2), or protein-tyrosine phosphatase 2C (PTP-2C) is an enzyme that in hu ...

.

These proteins are directly toxic to cells lining the stomach and signal strongly to the immune system that an invasion is under way. As a result of the bacterial presence, neutrophils and macrophages set up residence in the tissue to fight the bacteria assault. Pathogenic strains of ''H. pylori'' have been shown to activate the epidermal growth factor receptor

The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR; ErbB-1; HER1 in humans) is a transmembrane protein that is a receptor (biochemistry), receptor for members of the epidermal growth factor family (EGF family) of extracellular protein ligand (biochemistry ...

(EGFR), a membrane protein

Membrane proteins are common proteins that are part of, or interact with, biological membranes. Membrane proteins fall into several broad categories depending on their location. Integral membrane proteins are a permanent part of a cell membrane ...

with a TK domain. Activation of the EGFR by ''H. pylori'' is associated with altered signal transduction

Signal transduction is the process by which a chemical or physical signal is transmitted through a cell as a biochemical cascade, series of molecular events. Proteins responsible for detecting stimuli are generally termed receptor (biology), rece ...

and gene expression

Gene expression is the process (including its Regulation of gene expression, regulation) by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional gene product that enables it to produce end products, proteins or non-coding RNA, ...

in host epithelial cells that may contribute to pathogenesis. A C-terminal

The C-terminus (also known as the carboxyl-terminus, carboxy-terminus, C-terminal tail, carboxy tail, C-terminal end, or COOH-terminus) is the end of an amino acid chain (protein or polypeptide), terminated by a free carboxyl group (-COOH). When t ...

region of the CagA protein (amino acids 873–1002) has also been suggested to be able to regulate host cell gene transcription

Transcription is the process of copying a segment of DNA into RNA for the purpose of gene expression. Some segments of DNA are transcribed into RNA molecules that can encode proteins, called messenger RNA (mRNA). Other segments of DNA are transc ...

, independent of protein tyrosine phosphorylation. A great deal of diversity exists between strains of ''H. pylori'', and the strain that infects a person can predict the outcome.

VacA

VacA (vacuolating cytotoxin autotransporter) is another major virulence factor encoded by the ''vacA'' gene. All strains of ''H. pylori'' carry this gene but there is much diversity, and only 50% produce the encoded cytotoxin. The four main subtypes of ''vacA'' are ''s1/m1, s1/m2, s2/m1,'' and ''s2/m2''. ''s1/m1'' and ''s1/m2'' are known to cause an increased risk of gastric cancer. VacA is an oligomeric protein complex that causes a progressive vacuolation in the epithelial cells leading to their death. The vacuolation has also been associated with promoting intracellular reservoirs of ''H. pylori'' by disrupting the calcium channel cell membrane TRPML1. VacA has been shown to increase the levels ofCOX2

Cytochrome c oxidase II is a protein in eukaryotes that is encoded by the MT-CO2 gene. Cytochrome c oxidase subunit II, abbreviated COXII, COX2, COII, or MT-CO2, is the second subunit of cytochrome c oxidase. It is also one of the three mitoc ...

, an up-regulation that increases the production of a prostaglandin

Prostaglandins (PG) are a group of physiology, physiologically active lipid compounds called eicosanoids that have diverse hormone-like effects in animals. Prostaglandins have been found in almost every Tissue (biology), tissue in humans and ot ...

indicating a strong host cell inflammatory response.

Outer membrane proteins and vesicles

About 4% of the genome encodes for outer membrane proteins that can be grouped into five families. The largest family includesbacterial adhesin Bacterial adhesins are cell-surface components or appendages of bacteria that facilitate adhesion or adherence to other cells or to surfaces, usually in the host they are infecting or living in. Adhesins are a type of virulence factor.

Adherence is ...

s. The other four families are porins, iron transporters, flagellum

A flagellum (; : flagella) (Latin for 'whip' or 'scourge') is a hair-like appendage that protrudes from certain plant and animal sperm cells, from fungal spores ( zoospores), and from a wide range of microorganisms to provide motility. Many pr ...

-associated proteins, and proteins of unknown function. Like other typical gram-negative bacteria, the outer membrane of ''H. pylori'' consists of phospholipids

Phospholipids are a class of lipids whose molecule has a hydrophilic "head" containing a phosphate group and two hydrophobic "tails" derived from fatty acids, joined by an alcohol residue (usually a glycerol molecule). Marine phospholipids typi ...

and lipopolysaccharide

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), now more commonly known as endotoxin, is a collective term for components of the outermost membrane of the cell envelope of gram-negative bacteria, such as '' E. coli'' and ''Salmonella'' with a common structural archit ...

(LPS). The O-antigen of LPS may be fucosylated and mimic Lewis blood group antigens found on the gastric epithelium.

''H. pylori'' forms blebs from the outer membrane that pinch off as outer membrane vesicles to provide an alternative delivery system for virulence factors including CagA.

A ''Helicobacter'' cysteine-rich protein HcpA is known to trigger an immune response, causing inflammation.

A ''Helicobacter pylori'' virulence factor ''DupA'' is associated with the development of duodenal ulcers.

Mechanisms of tolerance

The need for survival has led to the development of different mechanisms of tolerance that enable the persistence of ''H. pylori''. These mechanisms can also help to overcome the effects of antibiotics. ''H. pylori'' has to not only survive the harsh gastric acidity but also the sweeping of mucus by continuousperistalsis

Peristalsis ( , ) is a type of intestinal motility, characterized by symmetry in biology#Radial symmetry, radially symmetrical contraction and relaxation of muscles that propagate in a wave down a tube, in an wikt:anterograde, anterograde dir ...

, and phagocytic

Phagocytosis () is the process by which a cell (biology), cell uses its plasma membrane to engulf a large particle (≥ 0.5 μm), giving rise to an internal compartment called the phagosome. It is one type of endocytosis. A cell that performs ph ...

attack accompanied by the release of reactive oxygen species

In chemistry and biology, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are highly Reactivity (chemistry), reactive chemicals formed from diatomic oxygen (), water, and hydrogen peroxide. Some prominent ROS are hydroperoxide (H2O2), superoxide (O2−), hydroxyl ...

. All organisms encode genetic programs for response to stressful conditions including those that cause DNA damage. Stress conditions activate bacterial response mechanisms that are regulated by proteins expressed by regulator genes. The oxidative stress

Oxidative stress reflects an imbalance between the systemic manifestation of reactive oxygen species and a biological system's ability to readily detoxify the reactive intermediates or to repair the resulting damage. Disturbances in the normal ...

can induce potentially lethal mutagenic DNA adduct

In molecular genetics, a DNA adduct is a segment of DNA bound to a Carcinogen, cancer-causing chemical. This process could lead to the development of cancerous cells, or carcinogenesis. DNA adducts in scientific experiments are used as biomarkers ...

s in its genome. Surviving this DNA damage

DNA repair is a collection of processes by which a cell identifies and corrects damage to the DNA molecules that encode its genome. A weakened capacity for DNA repair is a risk factor for the development of cancer. DNA is constantly modified ...

is supported by transformation

Transformation may refer to:

Science and mathematics

In biology and medicine

* Metamorphosis, the biological process of changing physical form after birth or hatching

* Malignant transformation, the process of cells becoming cancerous

* Trans ...

-mediated recombinational repair, that contributes to successful colonization. ''H. pylori'' is naturally competent for transformation. While many organisms are competent only under certain environmental conditions, such as starvation, ''H. pylori'' is competent throughout logarithmic growth.

Transformation

Transformation may refer to:

Science and mathematics

In biology and medicine

* Metamorphosis, the biological process of changing physical form after birth or hatching

* Malignant transformation, the process of cells becoming cancerous

* Trans ...

(the transfer of DNA from one bacterial cell to another through the intervening medium) appears to be part of an adaptation for DNA repair

DNA repair is a collection of processes by which a cell (biology), cell identifies and corrects damage to the DNA molecules that encode its genome. A weakened capacity for DNA repair is a risk factor for the development of cancer. DNA is cons ...

. Homologous recombination

Homologous recombination is a type of genetic recombination in which genetic information is exchanged between two similar or identical molecules of double-stranded or single-stranded nucleic acids (usually DNA as in Cell (biology), cellular organi ...

is required for repairing double-strand break

DNA repair is a collection of processes by which a cell identifies and corrects damage to the DNA molecules that encode its genome. A weakened capacity for DNA repair is a risk factor for the development of cancer. DNA is constantly modified ...

s (DSBs). The AddAB helicase-nuclease complex resects DSBs and loads RecA

RecA is a 38 kilodalton protein essential for the repair and maintenance of DNA in bacteria. Structural and functional homologs to RecA have been found in all kingdoms of life. RecA serves as an archetype for this class of homologous DNA repair p ...