C. Daryll Forde on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

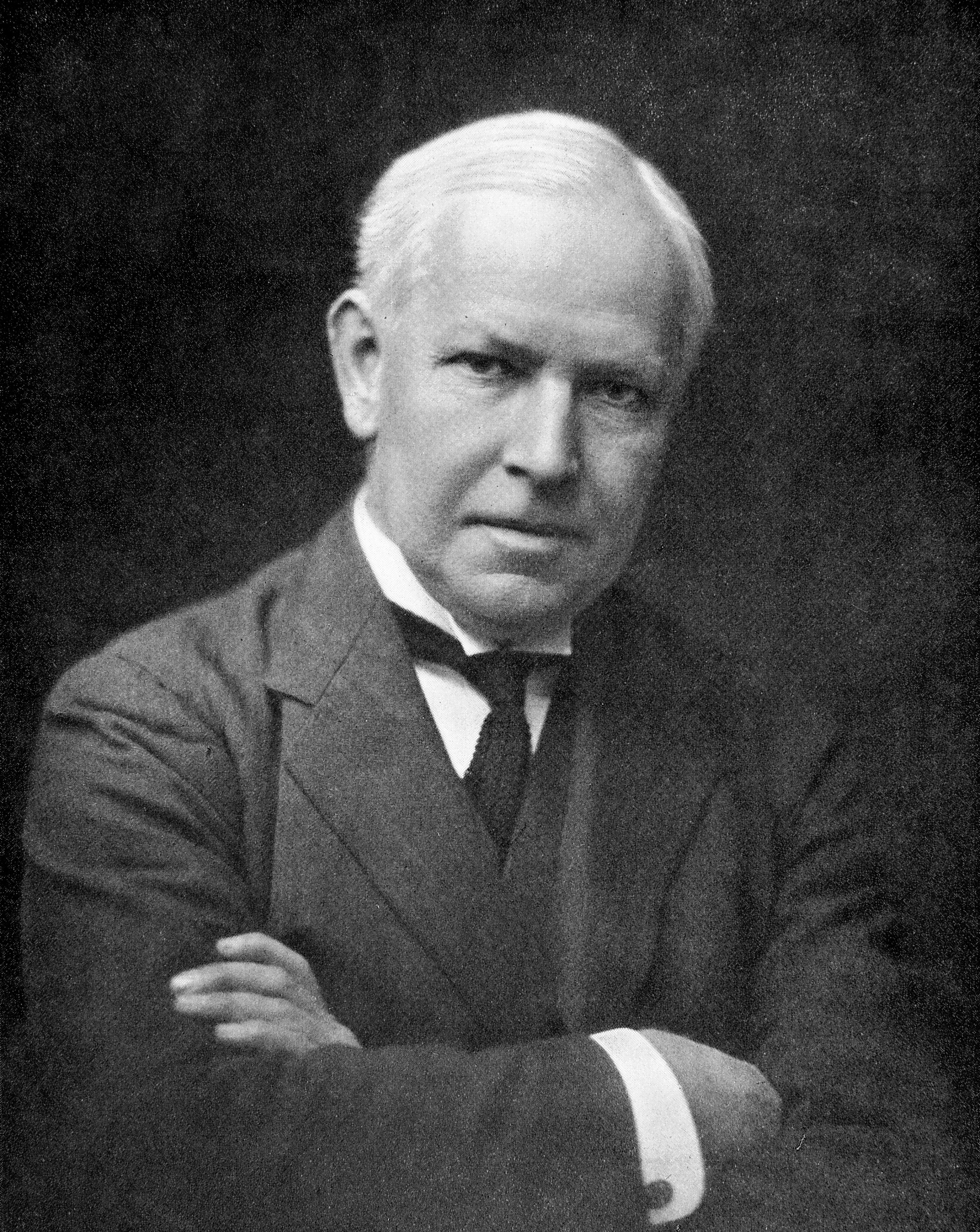

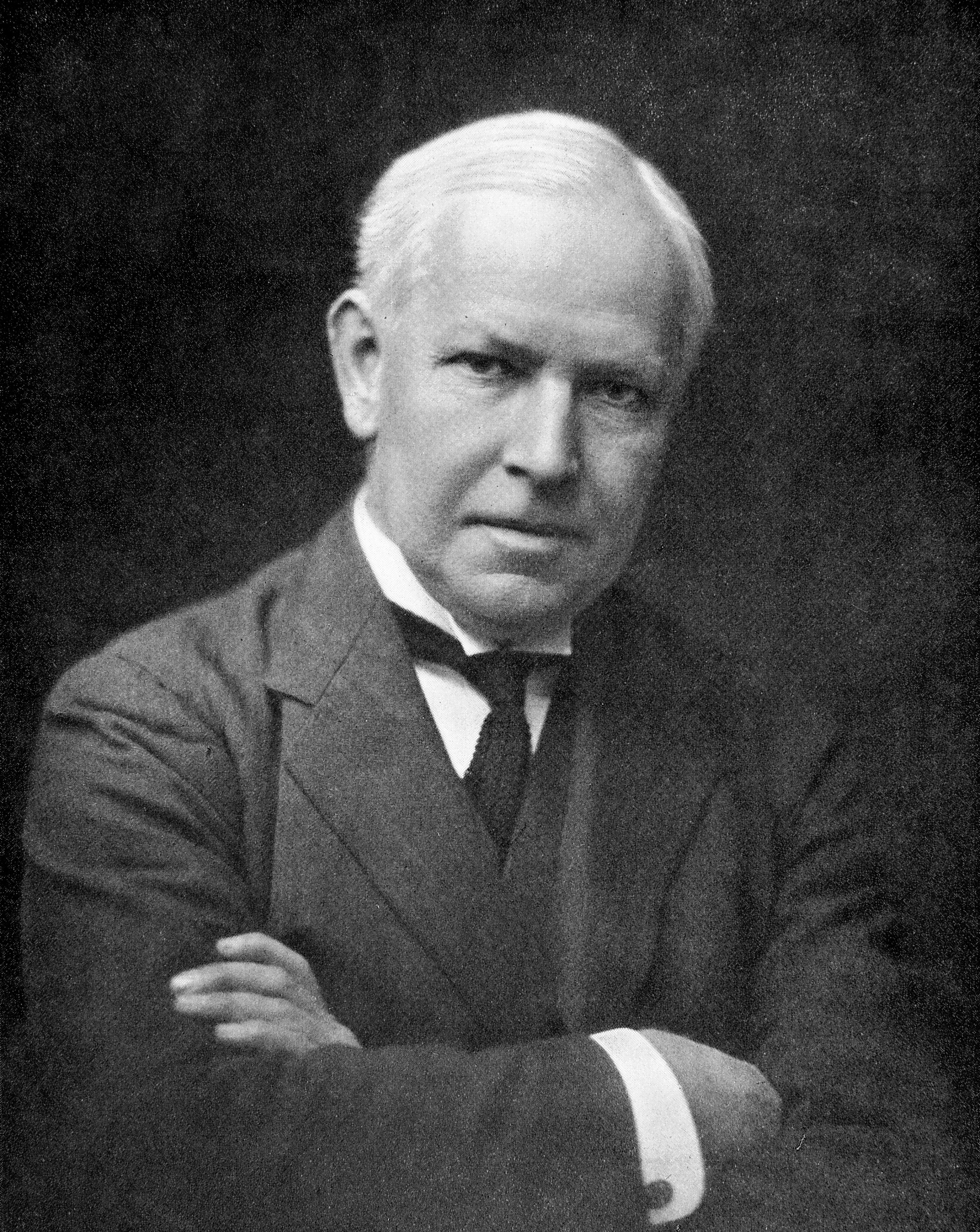

Cyril Daryll Forde

Forde was born in

Forde was born in

Complete bibliography

{{DEFAULTSORT:Forde, Daryll 1902 births 1973 deaths Alumni of University College London Academics of University College London 20th-century British anthropologists Fellows of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland Presidents of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland

FRAI

The Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland (RAI) is a long-established anthropological organisation, and Learned Society, with a global membership. Its remit includes all the component fields of anthropology, such as biolo ...

(16 March 1902 – 3 May 1973) was a British anthropologist

An anthropologist is a scientist engaged in the practice of anthropology. Anthropologists study aspects of humans within past and present societies. Social anthropology, cultural anthropology and philosophical anthropology study the norms, values ...

and Africanist.

Education and early career

Forde was born in

Forde was born in Tottenham

Tottenham (, , , ) is a district in north London, England, within the London Borough of Haringey. It is located in the Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county of Greater London. Tottenham is centred north-northeast of Charing Cross, ...

on 16 March 1902, the son of John Percival Daniel Forde, a reverend and schoolmaster, and Caroline Pearce Pittman. He attended the local county school in Tottenham, then went on to read geography

Geography (from Ancient Greek ; combining 'Earth' and 'write', literally 'Earth writing') is the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. Geography is an all-encompassing discipline that seeks an understanding o ...

at University College London

University College London (Trade name, branded as UCL) is a Public university, public research university in London, England. It is a Member institutions of the University of London, member institution of the Federal university, federal Uni ...

(UCL).

At that time there was no department of anthropology at UCL; the geography department had interests in ethnography

Ethnography is a branch of anthropology and the systematic study of individual cultures. It explores cultural phenomena from the point of view of the subject of the study. Ethnography is also a type of social research that involves examining ...

and archaeology

Archaeology or archeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts or ecofacts, ...

, but for the most part it was the domain of Grafton Elliot Smith

Sir Grafton Elliot Smith (15 August 1871 – 1 January 1937) was an Australian-British anatomist, Egyptologist and a proponent of the hyperdiffusionist view of prehistory. He believed in the idea that cultural innovations occur only once and ...

, a professor of anatomy

Anatomy () is the branch of morphology concerned with the study of the internal structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old scien ...

and noted proponent of hyperdiffusionism

Hyperdiffusionism is a pseudoarchaeological hypothesis that postulates that certain historical technologies or ideas were developed by a single people or civilization and then spread to other cultures. Thus, all great civilizations that engage in ...

. Forde studied under Smith and, upon completing his bachelor's degree in 1924, he was appointed a lecturer in the department of anatomy. His earliest work was influenced by Smith's belief that all of human civilisation originated in ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt () was a cradle of civilization concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in Northeast Africa. It emerged from prehistoric Egypt around 3150BC (according to conventional Egyptian chronology), when Upper and Lower E ...

. In his first book, ''Ancient Mariners'' (1928), Forde traced the origins of shipbuilding

Shipbuilding is the construction of ships and other Watercraft, floating vessels. In modern times, it normally takes place in a specialized facility known as a shipyard. Shipbuilders, also called shipwrights, follow a specialized occupation th ...

and maritime navigation to Egypt, whence he supposed it was carried around the world in ancient voyages:

Smith and Forde also collaborated on the excavation of a Bronze Age tumulus near Dunstable. The main focus of his research in the anatomy department, however, was the megalith

A megalith is a large stone that has been used to construct a prehistoric structure or monument, either alone or together with other stones. More than 35,000 megalithic structures have been identified across Europe, ranging geographically f ...

ic cultures of prehistoric western Europe. In this he was influenced by the culture historical theories of V. Gordon Childe

Vere Gordon Childe (14 April 189219 October 1957) was an Australian archaeologist who specialised in the study of European prehistory. He spent most of his life in the United Kingdom, working as an academic for the University of Edinburgh and ...

, who would become a lifelong friend and collaborator. Childe tempered Forde's enthusiasm for hyperdiffusionism, but Forde still advanced the idea that European megaliths were a "degenerated" imitation of monuments in the Near East. This theory remained influential in archaeology for many years.

Forde's archaeological work won him the Society of Antiquaries' prestigious Franks Studentship in 1924, and in 1928 he was awarded a doctorate in prehistoric archaeology.

Fellowship at Berkeley (1928–1930)

After receiving his doctorate, Forde won a Commonwealth Fellowship to work with the American anthropologistsAlfred Kroeber

Alfred Louis Kroeber ( ; June 11, 1876 – October 5, 1960) was an American cultural anthropologist. He received his PhD under Franz Boas at Columbia University in 1901, the first doctorate in anthropology awarded by Columbia. He was also the fi ...

and Robert Lowie

Robert Harry Lowie (born '; June 12, 1883 – September 21, 1957) was an Austrian-born American anthropologist. An expert on Indigenous peoples of the Americas, he was instrumental in the development of modern anthropology and has been described a ...

at the University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California), is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Berkeley, California, United States. Founded in 1868 and named after t ...

. He had been introduced to Lowie during the latter's visit to London in 1924. Both Kroeber and Lowie were students of Franz Boas

Franz Uri Boas (July 9, 1858 – December 21, 1942) was a German-American anthropologist and ethnomusicologist. He was a pioneer of modern anthropology who has been called the "Father of American Anthropology". His work is associated with the mov ...

, making Berkeley an influential early centre of what became known as Boasian anthropology

Boasian anthropology was a school within American anthropology founded by Franz Boas in the late 19th century. It was based on the four-field model of anthropology uniting the fields of cultural anthropology, linguistic anthropology, physical ant ...

. The intellectual climate there—very different to anthropology in Britain—had a profound effect on Forde's scholarship. He would later refer to it as his "transatlantic noviciate".

Both Kroeber and Lowie also had backgrounds in archaeology, but were committed to the Boasian four field approach and the holistic study of humanity. They therefore encouraged Forde to conduct ethnographic

Ethnography is a branch of anthropology and the systematic study of individual cultures. It explores cultural phenomena from the point of view of the subject of the study. Ethnography is also a type of social research that involves examining ...

fieldwork with local Native American tribes. He worked with the Yuma of the lower Colorado river valley and the Hopi

The Hopi are Native Americans who primarily live in northeastern Arizona. The majority are enrolled in the Hopi Tribe of Arizona and live on the Hopi Reservation in northeastern Arizona; however, some Hopi people are enrolled in the Colorado ...

of northern Arizona, leading to his most well-known work, ''Habitat, Economy and Society: a Geographical Introduction to Ethnology'' (1934). At Berkeley, he was trained in ecological anthropology and brought this tradition with him back to the UK.

Chair at Aberystwyth University (University College of Wales, Aberystwyth) 1930-1945

In 1930, when still only 28 years old, Daryll Forde was appointed Gregynog Professor of Geography and Anthropology at theUniversity College of Wales, Aberystwyth

Aberystwyth University () is a Public university, public Research university, research university in Aberystwyth, Wales. Aberystwyth was a founding member institution of the former federal University of Wales. The university has over 8,000 stude ...

. It was here, aged 31, that he commenced a 5-year excavation programme on the local Iron Age hillfort of Pen Dinas

Pen Dinas () is a large hill in Penparcau, on the coast of Ceredigion, Wales, (just south of Aberystwyth) upon which an extensive Iron Age, Celtic hillfort is situated. The site can easily be reached on foot from Aberystwyth town centre and is a ...

between 1933 and 1937, answering many earlier calls made during the 1920s for the excavation and dating of a local hillfort. Contemporary photographs of the excavation show the young Daryll Forde on site, well-dressed among the workmen and clearly enjoying directing one of the largest hillfort excavations in southern Britain at that time. It was during his early years at Aberystwyth in 1934 that he also published his influential text book 'Habitat, Economy and Society'.

Later career

From 1945 he worked atUniversity College London

University College London (Trade name, branded as UCL) is a Public university, public research university in London, England. It is a Member institutions of the University of London, member institution of the Federal university, federal Uni ...

, and built a school of American-style cultural anthropology

Cultural anthropology is a branch of anthropology focused on the study of cultural variation among humans. It is in contrast to social anthropology, which perceives cultural variation as a subset of a posited anthropological constant. The term ...

there, distinct from the social anthropology

Social anthropology is the study of patterns of behaviour in human societies and cultures. It is the dominant constituent of anthropology throughout the United Kingdom and much of Europe, where it is distinguished from cultural anthropology. In t ...

of British-trained contemporaries such as Alfred Radcliffe-Brown

Alfred Reginald Radcliffe-Brown, FBA (born Alfred Reginald Brown; 17 January 1881 – 24 October 1955) was an English social anthropologist who helped further develop the theory of structural functionalism. He conducted fieldwork in the Andam ...

, Meyer Fortes

Meyer Fortes FBA FRAI (25 April 1906 – 27 January 1983) was a South African-born anthropologist, best known for his work among the Tallensi and Ashanti in Ghana.

Originally trained in psychology, Fortes employed the notion of the "perso ...

and E. E. Evans-Pritchard

Sir Edward Evan Evans-Pritchard FBA FRAI (21 September 1902 – 11 September 1973) was an English anthropologist who was instrumental in the development of social anthropology. He was Professor of Social Anthropology at the University of Ox ...

.

From 1935 he worked in Nigeria with the Yakö people. His work in Africa resulted in several volumes of ''African Worlds: Studies in the Cosmological Ideas and Social Values of African Peoples'' (1954). From 1945 to 1973 he was the director of the International African Institute

The International African Institute (IAI) was founded (as the International Institute of African Languages and Cultures - IIALC) in 1926 in London for the study of African languages. Frederick Lugard was the first chairman (1926 to his death in 19 ...

.

UCL's department of anthropology has an annual lecture series and a seminar room named in his honour.

References

External links

Complete bibliography

{{DEFAULTSORT:Forde, Daryll 1902 births 1973 deaths Alumni of University College London Academics of University College London 20th-century British anthropologists Fellows of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland Presidents of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland