Budai Nagy Antal Revolt on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Transylvanian peasant revolt ( hu, erdélyi parasztfelkelés), also known as the peasant revolt of Bábolna or Bobâlna revolt ( ro, Răscoala de la Bobâlna), was a popular revolt in the eastern territories of the

In order to tackle financial burdens resulting from the

In order to tackle financial burdens resulting from the

The rebels abandoned their fortified camp on Mount Bábolna, most probably because they needed new provisions. They moved towards Dés, pillaging the noblemen's manors during their march. They threatened all who did not support them with severe punishments. They established a new camp on the Szamos (Someș) River near the town. A new battle was fought between the rebels and their enemies near the camp in late September.

After being unable to overcome the rebels, the noblemen started new negotiations with them at Dellőapáti ( Apatiu). The representatives of the two parties reached a new compromise on 6 October, which was included in a new charter in the Kolozsmonostor Abbey four days later. For unknown reasons, the peasants accepted less favorable terms than those of the first agreement. Demény argues, their leaders had most probably realized that they were unable to resist for a long time.

According to the new agreement, the minimum amount of the rent payable by the peasants to the landowners was increased to 12 denars per year; peasants who held larger plots were to pay 25 to 100 denars to their lords, which was equal to the sum payable before the uprising. The new agreement did not determine the "gifts" that the peasants were to give to the landowners, only stating that they were required to fulfill this obligation three times a year. The agreement confirmed the noblemen's right to administer justice to the peasants living in their estates, but also stipulated that the peasants could appeal against their lords' decision to the court of a nearby village or small town.

The rebels abandoned their fortified camp on Mount Bábolna, most probably because they needed new provisions. They moved towards Dés, pillaging the noblemen's manors during their march. They threatened all who did not support them with severe punishments. They established a new camp on the Szamos (Someș) River near the town. A new battle was fought between the rebels and their enemies near the camp in late September.

After being unable to overcome the rebels, the noblemen started new negotiations with them at Dellőapáti ( Apatiu). The representatives of the two parties reached a new compromise on 6 October, which was included in a new charter in the Kolozsmonostor Abbey four days later. For unknown reasons, the peasants accepted less favorable terms than those of the first agreement. Demény argues, their leaders had most probably realized that they were unable to resist for a long time.

According to the new agreement, the minimum amount of the rent payable by the peasants to the landowners was increased to 12 denars per year; peasants who held larger plots were to pay 25 to 100 denars to their lords, which was equal to the sum payable before the uprising. The new agreement did not determine the "gifts" that the peasants were to give to the landowners, only stating that they were required to fulfill this obligation three times a year. The agreement confirmed the noblemen's right to administer justice to the peasants living in their estates, but also stipulated that the peasants could appeal against their lords' decision to the court of a nearby village or small town.

The delegates of the three Estates of Transylvania, noblemen (including the ennobled Saxons and Vlachs), Székelys, and Saxons, assembled at Torda on 2 February 1438. They confirmed their "brotherly union" against the rebellious peasants and the Ottoman marauders. Nine leaders of the revolt were executed at the assembly. Other defenders of Kolozsvár were mutilated. Taking advantage of the victory, the leaders of the noblemen also made attempts to harm their personal enemies. For instance, the voivode who wanted to seize some properties of the Báthorys accused them of having cooperated with the rebels. In retaliation for its support of the rebels, Kolozsvár was deprived of its municipal rights on 15 November. However, the burghers attained the restoration of their liberties with the support of

The delegates of the three Estates of Transylvania, noblemen (including the ennobled Saxons and Vlachs), Székelys, and Saxons, assembled at Torda on 2 February 1438. They confirmed their "brotherly union" against the rebellious peasants and the Ottoman marauders. Nine leaders of the revolt were executed at the assembly. Other defenders of Kolozsvár were mutilated. Taking advantage of the victory, the leaders of the noblemen also made attempts to harm their personal enemies. For instance, the voivode who wanted to seize some properties of the Báthorys accused them of having cooperated with the rebels. In retaliation for its support of the rebels, Kolozsvár was deprived of its municipal rights on 15 November. However, the burghers attained the restoration of their liberties with the support of

Wealth of the winners

{{Authority control 1437 in Europe 1438 in Europe Battles involving Transylvania Conflicts in 1437 Conflicts in 1438 15th-century rebellions Medieval Transylvania Peasant revolts Popular revolt in late-medieval Europe Riots and civil disorder in Hungary Wars involving Hungary

Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the coronation of the first king Stephen ...

in 1437. The revolt broke out after George Lépes, bishop of Transylvania

:''There is also a Romanian Orthodox Archbishop of Alba Iulia and a Greek Catholic Archdiocese of Făgăraş and Alba Iulia.''

The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Alba Iulia ( hu, Gyulafehérvári Római Katolikus Érsekség) is a Latin Church Ca ...

, had failed to collect the tithe for years because of a temporary debasement

A debasement of coinage is the practice of lowering the intrinsic value of coins, especially when used in connection with commodity money, such as gold or silver coins. A coin is said to be debased if the quantity of gold, silver, copper or nick ...

of the coinage, but then demanded the arrears

Arrears (or arrearage) is a legal term for the part of a debt that is overdue after missing one or more required payments. The amount of the arrears is the amount accrued from the date on which the first missed payment was due. The term is usually ...

in one sum when coins of higher value were again issued. Most commoners were unable to pay the demanded sum, but the bishop did not renounce his claim and applied interdict

In Catholic canon law, an interdict () is an ecclesiastical censure, or ban that prohibits persons, certain active Church individuals or groups from participating in certain rites, or that the rites and services of the church are banished from h ...

and other ecclesiastic penalties to enforce the payment.

The Transylvanian peasants had already been outraged because of the increase of existing seigneurial duties and taxes and the introduction of new taxes during the first decades of the century. The bishop also tried to collect the tithe from the petty noblemen

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The characteristi ...

and from Orthodox Vlachs

"Vlach" ( or ), also "Wallachian" (and many other variants), is a historical term and exonym used from the Middle Ages until the Modern Era to designate mainly Romanians but also Aromanians, Megleno-Romanians, Istro-Romanians and other Easter ...

who had settled in parcels abandoned by Catholic peasants. In the spring of 1437, Hungarian and Vlach commoners, poor townspeople from Kolozsvár (now Cluj-Napoca

; hu, kincses város)

, official_name=Cluj-Napoca

, native_name=

, image_skyline=

, subdivision_type1 = County

, subdivision_name1 = Cluj County

, subdivision_type2 = Status

, subdivision_name2 = County seat

, settlement_type = City

, le ...

in Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, and ...

)The article always mentions the Romanian official name of the settlements in parentheses, because Transylvania is now part of Romania. and petty noblemen started to assemble on the flat summit of Mount Bábolna near Alparét (Bobâlna

Bobâlna (''Olpret'' until 1957; hu, Alparét; german: Krautfeld) is a commune in Cluj County, Transylvania, Romania, having a population of 1,888. It is composed of eleven villages: Antăș (''Antos''), Băbdiu (''Zápróc''), Blidărești (''T ...

) where they set up a fortified camp. The bishop and his brother, Roland Lépes, the deputy of the voivode (or royal governor) of Transylvania, gathered their troops to fight against the rebels. The voivode, the two counts of the Székelys

Count (feminine: countess) is a historical title of nobility in certain European countries, varying in relative status, generally of middling rank in the hierarchy of nobility. Pine, L. G. ''Titles: How the King Became His Majesty''. New York ...

and many Transylvanian noblemen also hurried to the mountain to assist them against the rebels.

The rebels sent envoys to the voivode to inform him about their grievances, but the envoys were captured and executed. The voivode invaded the rebels' camp, but the peasants resisted and made a successful counter-attack, killing many noblemen during the battle. To prevent the rebels from continuing the war, the bishop and the leaders of the noblemen started negotiations with the rebels' envoys. Their compromise was recorded in the Kolozsmonostor Abbey

The Kolozsmonostor Abbey was a Benedictine Christian monastery at Kolozsmonostor in Transylvania in the medieval Kingdom of Hungary (now Mănăștur in Cluj-Napoca in Romania). According to modern scholars' consensus, the monastery was establis ...

on 6 July. The agreement reduced the tithe by half, abolished the ninth (a seigneurial tax), guaranteed the peasants' right to free movement and authorized them to hold an annual assembly to secure the execution of the agreement.

The noblemen, the counts of the Székelys and the delegates of the Saxon

The Saxons ( la, Saxones, german: Sachsen, ang, Seaxan, osx, Sahson, nds, Sassen, nl, Saksen) were a group of Germanic

*

*

*

*

peoples whose name was given in the early Middle Ages to a large country (Old Saxony, la, Saxonia) near the Nor ...

seats concluded a "brotherly union" against their enemies at Kápolna ( Căpâlna). The rebellious peasants left their camp and moved towards Dés (Dej

Dej (; hu, Dés; german: Desch, Burglos; yi, דעעש ''Desh'') is a municipality in Transylvania, Romania, north of Cluj-Napoca, in Cluj County. It lies where the river Someșul Mic meets the river Someșul Mare. The city administers four vil ...

). After a battle near the town, the parties concluded a new agreement on 6 October which increased the rent payable by the peasants to the landowners. Shortly thereafter, the peasants invaded the Kolozsmonostor Abbey and took possession of Kolozsvár and Nagyenyed (Aiud

Aiud (; la, Brucla, hu, Nagyenyed, Hungarian pronunciation: ; german: Straßburg am Mieresch) is a city located in Alba County, Transylvania, Romania. The city's population is 22,876. It has the status of municipality and is the 2nd-largest ...

). The united armies of the voivode of Transylvania, the counts of the Székelys and the Saxon seats forced the rebels to surrender in January 1438. The leaders of the revolt were executed and other rioters were mutilated at the assembly of the representatives of the Three Nations of Transylvania

Unio Trium Nationum (Latin for "Union of the Three Nations") was a pact of mutual aid codified in 1438 by three Estates of Transylvania: the (largely Hungarian) nobility, the Saxon ( German) patrician class, and the free military Székelys.

The ...

in February.

Background

Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the Ap ...

("the Land beyond the Forests") was a geographic region

In geography, regions, otherwise referred to as zones, lands or territories, are areas that are broadly divided by physical characteristics (physical geography), human impact characteristics (human geography), and the interaction of humanity and t ...

in the 15th-century Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the coronation of the first king Stephen ...

. Four major ethnic groups – the Hungarians

Hungarians, also known as Magyars ( ; hu, magyarok ), are a nation and ethnic group native to Hungary () and historical Hungarian lands who share a common culture, history, ancestry, and language. The Hungarian language belongs to the Urali ...

, Saxons

The Saxons ( la, Saxones, german: Sachsen, ang, Seaxan, osx, Sahson, nds, Sassen, nl, Saksen) were a group of Germanic

*

*

*

*

peoples whose name was given in the early Middle Ages to a large country (Old Saxony, la, Saxonia) near the Nor ...

, Székelys

The Székelys (, Székely runes: 𐳥𐳋𐳓𐳉𐳗), also referred to as Szeklers,; ro, secui; german: Szekler; la, Siculi; sr, Секељи, Sekelji; sk, Sikuli are a Hungarian subgroup living mostly in the Székely Land in Romania. ...

, and Vlachs

"Vlach" ( or ), also "Wallachian" (and many other variants), is a historical term and exonym used from the Middle Ages until the Modern Era to designate mainly Romanians but also Aromanians, Megleno-Romanians, Istro-Romanians and other Easter ...

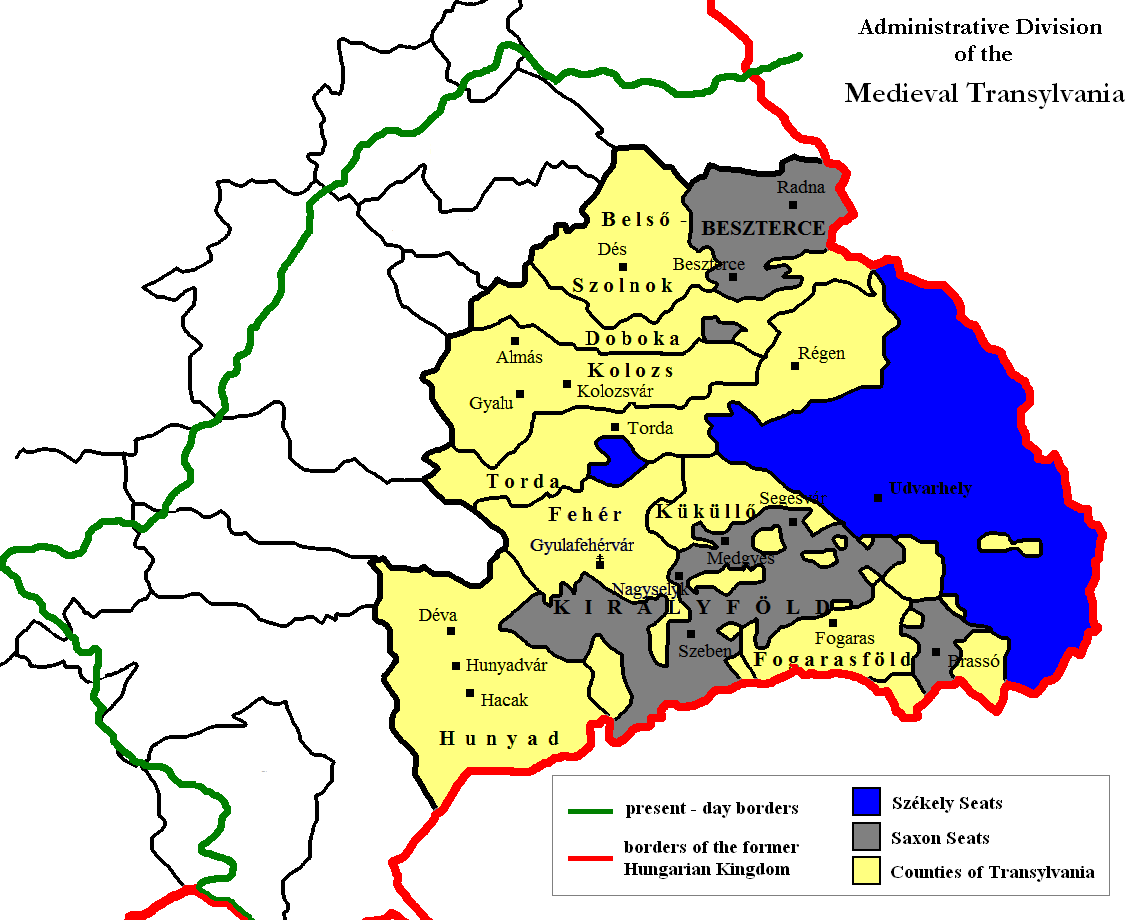

( Romanians) – inhabited the territory. The Hungarians, the Hungarian-speaking Székelys, and the Saxons formed sedentary communities, living in villages and towns. Many of the Vlachs were shepherds, herding their flocks between the mountains and the lowlands, but the monarchs and other landowners granted them fiscal privileges to advance their settlement in arable lands from the second half of the century. The Vlachs initially enjoyed a special status, which included that they were to pay tax only on their sheep, but Vlach commoners who settled in royal or private estates quickly lost their liberties. For administrative purposes, Transylvania was divided into counties and seats

A seat is a place to sit. The term may encompass additional features, such as back, armrest, head restraint but also headquarters in a wider sense.

Types of seat

The following are examples of different kinds of seat:

* Armchair, a chair e ...

. The seven Transylvanian counties were subjected to the authority of a high-ranking royal official, the voivode of Transylvania

The Voivode of Transylvania (german: Vojwode von Siebenbürgen;Fallenbüchl 1988, p. 77. hu, erdélyi vajda;Zsoldos 2011, p. 36. la, voivoda Transsylvaniae; ro, voievodul Transilvaniei) was the highest-ranking official in Transylvania wit ...

. The seats were the administrative units of the autonomous Saxon and Székely communities.

The voivodes presided over the noblemen's general assemblies, which were annually held at a meadow near Torda (Turda

Turda (; hu, Torda, ; german: link=no, Thorenburg; la, Potaissa) is a city in Cluj County, Transylvania, Romania. It is located in the southeastern part of the county, from the county seat, Cluj-Napoca, to which it is connected by the Europ ...

). From the early 15th century, the voivodes rarely visited Transylvania, leaving the administration of the counties to their deputies, the vice-voivodes. The Transylvanian noblemen were exempted from taxation in 1324. Noblemen were granted the right to administer justice to the peasants living in their estates in 1342. The prelates acquired the same right in their domains in the second half of the 14th century. In 1366, Louis I of Hungary

Louis I, also Louis the Great ( hu, Nagy Lajos; hr, Ludovik Veliki; sk, Ľudovít Veľký) or Louis the Hungarian ( pl, Ludwik Węgierski; 5 March 132610 September 1382), was King of Hungary and Croatia from 1342 and King of Poland from 1370 ...

decreed

A decree is a legal proclamation, usually issued by a head of state (such as the president of a republic or a monarch), according to certain procedures (usually established in a constitution). It has the force of law. The particular term used for ...

that an oath taken by a Vlach ''knez'' (or chieftain) who "had been brought" to his estate by royal writ was equal to a true nobleman's oath, but other ''knezes'' were on a footing of equality with the heads of villages. The legal position of the ''knezes'' was similar to the " nobles of the Church" and other groups of conditional noble

A conditional noble or predialistSegeš 2002, p. 286. ( hu, prédiális nemes; la, nobilis praedialis; hr, predijalci) was a landowner in the Kingdom of Hungary who was obliged to render specific services to his lord in return for his landholding ...

s, but the monarchs frequently rewarded them with true nobility. The ennobled Vlachs enjoyed the same privileges as their ethnic Hungarian peers, thus they became members of the "Hungarian nation" which had been associated with the community of noblemen. On the other hand, the Vlach commoners who lived on their estates lost their liberties.

The Székelys were a community of privileged border guards. They fought in the royal army, for which they were exempted from taxation. A royal official, the count of the Székelys

The Count of the Székelys ( hu, székelyispán, la, comes Sicolorum) was the leader of the Hungarian-speaking Székelys in Transylvania, in the medieval Kingdom of Hungary. First mentioned in royal charters of the 13th century, the counts were ...

, was their supreme leader, but the Székely seats were administered by elected officials. The Saxons also had the right to elect the magistrates of their seats. They enjoyed personal freedom and paid a lump sum tax to the monarchs. The wealthiest Saxon towns – Bistritz, Hermannstadt and Kronstadt (Bistrița

(; german: link=no, Bistritz, archaic , Transylvanian Saxon: , hu, Beszterce) is the capital city of Bistrița-Năsăud County, in northern Transylvania, Romania. It is situated on the Bistrița River. The city has a population of approxima ...

, Sibiu

Sibiu ( , , german: link=no, Hermannstadt , la, Cibinium, Transylvanian Saxon: ''Härmeschtat'', hu, Nagyszeben ) is a city in Romania, in the historical region of Transylvania. Located some north-west of Bucharest, the city straddles the Cib ...

and Brașov

Brașov (, , ; german: Kronstadt; hu, Brassó; la, Corona; Transylvanian Saxon: ''Kruhnen'') is a city in Transylvania, Romania and the administrative centre of Brașov County.

According to the latest Romanian census (2011), Brașov has a pop ...

) – owned large estates which were cultivated by hundreds of peasants. Dozens of Saxons and Székely families held landed property in the counties, for which they also enjoyed the status of noblemen. Saxon and Székely leaders were occasionally invited to Torda to attend the general assemblies, which enabled the leaders of the three nations to coordinate their actions.

The towns, located in the counties, could hardly compete with the large Saxon centers. Kolozsvár was granted the right to buy landed property from the noblemen or other landowners in 1370, but its burghers were regarded as peasants by the bishops of Transylvania and the abbots of Kolozsmonostor Abbey

The Kolozsmonostor Abbey was a Benedictine Christian monastery at Kolozsmonostor in Transylvania in the medieval Kingdom of Hungary (now Mănăștur in Cluj-Napoca in Romania). According to modern scholars' consensus, the monastery was establis ...

, who forced them to pay the ninth (a seigneurial tax) on their vineyards until 1409. The merchants from Kolozsvár, Dés and other Transylvanian towns were exempted from internal levies, but the noblemen often ignored that privilege, forcing the merchants to pay duties while travelling across their domains.

The Hungarians, Saxons and Székelys adhered to Roman Catholicism. The Diocese of Transylvania included most of the province, but the Saxons of Southern Transylvania were subjected to the archbishops of Esztergom. Catholic commoners were to pay an ecclesiastic tax, the tithe

A tithe (; from Old English: ''teogoþa'' "tenth") is a one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government. Today, tithes are normally voluntary and paid in cash or cheques or more r ...

, but John XXIII

Pope John XXIII ( la, Ioannes XXIII; it, Giovanni XXIII; born Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli, ; 25 November 18813 June 1963) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 28 October 1958 until his death in June 19 ...

exempted the lesser noblemen from paying it in 1415. However, George Lépes, the bishop of Transylvania, ignored this decision, especially after John had been declared an antipope

An antipope ( la, antipapa) is a person who makes a significant and substantial attempt to occupy the position of Bishop of Rome and leader of the Catholic Church in opposition to the legitimately elected pope. At times between the 3rd and mid ...

. The Vlachs were originally exempt from the ecclesiastic tax, but Sigismund of Luxemburg

Sigismund of Luxembourg (15 February 1368 – 9 December 1437) was a monarch as King of Hungary and Croatia in union with Hungary, Croatia (''jure uxoris'') from 1387, King of Germany from 1410, King of Bohemia from 1419, and Holy Roman Emperor ...

, king of Hungary, decreed that the Vlachs who settled on lands abandoned by Catholic peasants were to also pay the tithe. Sigismund was an absent monarch, deeply involved in European politics; he spent much time outside Hungary, especially in his other realms, such as Germany and Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohe ...

.

The Ottomans attacked Transylvania almost every year starting in 1420. The peasants had to pay the increasing costs for defence against the Ottomans. They were regularly obliged to pay "extraordinary taxes" in addition to the chamber's profit (the traditional tax payable by each peasant household to the royal treasury). The king also ordered that every tenth peasant should take up arms in case of an Ottoman attack, although peasants had always been exempt from military obligations. The accommodation of the troops was also an irksome duty, because the soldiers often forced the peasants to supply them with food and clothes. The landowners began to collect the ninth from the peasants. Although the ninth had already been introduced in 1351, it was not regularly collected in Transylvania. The noblemen also made attempts to hinder the free movement of their serfs.

The increasing taxes and the new burdens stirred up the commoners. The Transylvanian Saxons could only overcome their rebellious serfs with the assistance of the vice-voivode, Roland Lépes, in 1417. The united armies of the counties and the Saxon seats crushed the Székely commoners' uprising in 1433. In early 1434, the burghers of Kronstadt had to seek the assistance of the count of the Székelys against the Vlachs who had risen up in Fogaras County

Fogaras was an administrative county (comitatus) of the Kingdom of Hungary. Its territory is now in central Romania (south-eastern Transylvania). The county's capital was Fogaras (present-day Făgăraș).

Geography

Fogaras county shared border ...

. Hussite ideas, especially their egalitarian Taborite

The Taborites ( cs, Táborité, cs, singular Táborita), known by their enemies as the Picards, were a faction within the Hussite movement in the medieval Lands of the Bohemian Crown.

Although most of the Taborites were of rural origin, they ...

version, began to spread among the peasantry in the 1430s. In May 1436, George Lépes urged the inquisitor James of the Marches to come to Transylvania, because Hussite preachers had converted many people to their faith in his diocese.

Peasant war

Bishop Lépes's actions

In order to tackle financial burdens resulting from the

In order to tackle financial burdens resulting from the Hussite wars

The Hussite Wars, also called the Bohemian Wars or the Hussite Revolution, were a series of civil wars fought between the Hussites and the combined Catholic forces of Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund, the Papacy, European monarchs loyal to the Ca ...

and military campaigns against the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, Sigismund of Luxemburg put lower value silver coins into circulation in 1432. The new pennies were known as quarting because they contained only a quarter of the silver content of the old currency. Bishop Lépes, who knew that pennies of higher value would again be minted in a few years, suspended the collection of the tithe in 1434.

After the valuable coins were issued, Lépes demanded the tithe for the previous years in one sum. Historians estimate that the peasant families were required to pay six to nine gold florins, although the value of an average peasant lot was only about 40 florins. Most peasants were unable to pay this amount, especially because they also had to pay the seigneurial taxes to the owners of their parcels.

To secure the payment of the arrears, the bishop applied ecclesiastic penalties, placing whole villages under interdict in summer 1436. He also excommunicated the petty noblemen who had refused to pay the tithe. However, most serfs resisted and their lords were unwilling to assist the bishop. At the bishop's request, the king ordered the voivode and the ''ispán

The ispánRady 2000, p. 19.''Stephen Werbőczy: The Customary Law of the Renowned Kingdom of Hungary in Three Parts (1517)'', p. 450. or countEngel 2001, p. 40.Curta 2006, p. 355. ( hu, ispán, la, comes or comes parochialis, and sk, župan)Kirs ...

s'' (or heads) of the counties to secure the collection of the tithe in early September. The king also decreed that all peasants who failed to pay the arrears within a month after their excommunication were to pay twelve golden florins as a penalty.

Rebellion breaks out

The revolt developed from local disturbances in the first half of 1437. The villagers from Daróc, Mákó and Türe ( Dorolțu, Macău and Turea) assaulted the abbot of Kolozsmonostor at Bogártelke ( Băgara) in March. InAlsó-Fehér County

Alsó-Fehér was an administrative county (comitatus) of the Kingdom of Hungary. Its territory is now in western Romania (central Transylvania). The latest capital of the county was Nagyenyed (present-day Aiud).

Geography

Alsó-Fehér county sha ...

and around Déva (Deva

Deva may refer to:

Entertainment

* ''Deva'' (1989 film), a 1989 Kannada film

* ''Deva'' (1995 film), a 1995 Tamil film

* ''Deva'' (2002 film), a 2002 Bengali film

* Deva (2007 Telugu film)

* ''Deva'' (2017 film), a 2017 Marathi film

* Deva ...

), the serfs gathered into small bands and attacked the noblemen's manors. Peasants from Alparét and Bogáta ( Bogata de Sus) were the first to settle on the top of the nearby Mount Bábolna in May or June. Being surrounded by high cliffs and dense forests and crowned by a plateau of about , the mountain was an ideal place for defence. Following the Taborites' military strategy, the rebels established a camp on the flat summit of the mountain.

A lesser nobleman, Antal Nagy de Buda, came with a group of peasants from Diós and Burjánosóbuda ( Deușu and Vechea) to the mountain. The Vlach Mihai arrived with people from Virágosberek ( Florești). Salt miners from Szék (Sic

The Latin adverb ''sic'' (; "thus", "just as"; in full: , "thus was it written") inserted after a quoted word or passage indicates that the quoted matter has been transcribed or translated exactly as found in the source text, complete with any e ...

) and poor townspeople from Kolozsvár joined the peasantry. About 5–6,000 armed men gathered on the plateau by the end of June, according to historian Lajos Demény's estimation.

Bishop Lépes and his brother, the vice-voivode, started to assemble their troops near the peasants' camp. The absent voivode, Ladislaus Csáki, hurried to Transylvania. The counts of the Székelys, Michael Jakcs and Henry Tamási, also joined the united armies of the voivode and the bishop. The young noblemen who joined the campaign wanted to make a sudden assault on the peasants, but the bishop suggested that the peasants should be pacified through negotiations. The delay enabled the rioters to complete the fortification of their camp.

First battle and compromise

The peasants elected four envoys to inform the voivode about their grievances. They requested Csáki to put an end to abuses over the collection of the tithe and to persuade the bishop to lift the ecclesiastic bans. They also demanded the confirmation of the serfs' right to free movement. Instead of entering into negotiations, the voivode had the rebels' envoys tortured and executed in late June. He soon invaded the rebels' camp, but the peasants repulsed the attack and encircled his army. During the ensuing battle, many noblemen perished; Bishop Lépes barely escaped from the battlefield. The representatives of the noblemen and the rebels entered into negotiations in early July. The rebels' deputies were appointed by their leaders, including Pál Nagy de Vajdaháza, who styled himself "the flag bearer of the ''universitas'' of the Hungarian and Vlach inhabitants of this part of Transylvania". The use of the term "''universitas''" evidences that the peasantry sought the acknowledgement of their liberties as a community. The peasants emphasized that they wanted to "regain their freedoms granted them by the ancient kings, freedoms that had been suppressed by all sorts of subterfuges", because they were convinced that their liberties had been recorded in a charter during the reign of the first king of Hungary,Saint Stephen

Stephen ( grc-gre, Στέφανος ''Stéphanos'', meaning "wreath, crown" and by extension "reward, honor, renown, fame", often given as a title rather than as a name; c. 5 – c. 34 AD) is traditionally venerated as the protomartyr or first ...

. Their belief in a "good king" who had secured his subjects' welfare in a mythical "golden age" was not unusual in the Middle Ages.

The parties reached a compromise which was recorded in the Kolozsmonostor Abbey on 6 July. They agreed that the tithe would be reduced by half. The payment of the rents, taxes and other levies due to the landowners and the royal treasury was suspended until the tithe was collected. The agreement abolished the ninth and prescribed that the peasants were only required to pay the rent to the landowners. The annual amount of the rent was fixed at 10 denars, much lower than the rent from before the uprising. The noblemen also acknowledged the peasants' right to free movement, which could only be limited if a peasant failed to fulfill his obligations to the landowner. To keep the execution of the agreement under surveillance, the peasants were authorized to hold an annual assembly at Mount Bábolna. Their assembly was entitled to punish noblemen who had broken the compromise.

The Kolozsmonostor agreement prescribed that the "delegates of the noblemen and the inhabitants of the realm" should ask Sigismund of Luxemburg to send an authentic copy of Stephen's charter. The peasants agreed that the provisions of the charter were to be applied in case of a contradiction between the charter and the Kolozsmonostor agreement. The peasants preserved the right to elect delegates and start new negotiations with the representatives of the noblemen if Stephen's charter did not properly regulate their obligations towards the landowners.

Union of the Three Nations

The bishop and the noblemen regarded the Kolozsmonostor agreement as a temporary compromise. Their motives were to encourage the rebels to demobilize and to give them time to muster new troops. They assembled at Kápolna and started negotiations with the counts of the Székelys and the delegates of the Saxon seats. This was the first occasion when the representatives of the noblemen, Székelys and Saxons held a joint assembly without the authorization of the monarch. They concluded a "brotherly union" against their enemies in early September, pledging to provide military assistance to each other against both internal and foreign aggressors. The bishop seems to have acknowledged that petty noblemen were exempt from paying the tithe, according to Demény, because theDiet of Hungary

The Diet of Hungary or originally: Parlamentum Publicum / Parlamentum Generale ( hu, Országgyűlés) became the supreme legislative institution in the medieval kingdom of Hungary from the 1290s, and in its successor states, Royal Hungary and ...

decreed that noblemen could not be forced to pay the tithe in 1438.

Second battle and second compromise

The rebels abandoned their fortified camp on Mount Bábolna, most probably because they needed new provisions. They moved towards Dés, pillaging the noblemen's manors during their march. They threatened all who did not support them with severe punishments. They established a new camp on the Szamos (Someș) River near the town. A new battle was fought between the rebels and their enemies near the camp in late September.

After being unable to overcome the rebels, the noblemen started new negotiations with them at Dellőapáti ( Apatiu). The representatives of the two parties reached a new compromise on 6 October, which was included in a new charter in the Kolozsmonostor Abbey four days later. For unknown reasons, the peasants accepted less favorable terms than those of the first agreement. Demény argues, their leaders had most probably realized that they were unable to resist for a long time.

According to the new agreement, the minimum amount of the rent payable by the peasants to the landowners was increased to 12 denars per year; peasants who held larger plots were to pay 25 to 100 denars to their lords, which was equal to the sum payable before the uprising. The new agreement did not determine the "gifts" that the peasants were to give to the landowners, only stating that they were required to fulfill this obligation three times a year. The agreement confirmed the noblemen's right to administer justice to the peasants living in their estates, but also stipulated that the peasants could appeal against their lords' decision to the court of a nearby village or small town.

The rebels abandoned their fortified camp on Mount Bábolna, most probably because they needed new provisions. They moved towards Dés, pillaging the noblemen's manors during their march. They threatened all who did not support them with severe punishments. They established a new camp on the Szamos (Someș) River near the town. A new battle was fought between the rebels and their enemies near the camp in late September.

After being unable to overcome the rebels, the noblemen started new negotiations with them at Dellőapáti ( Apatiu). The representatives of the two parties reached a new compromise on 6 October, which was included in a new charter in the Kolozsmonostor Abbey four days later. For unknown reasons, the peasants accepted less favorable terms than those of the first agreement. Demény argues, their leaders had most probably realized that they were unable to resist for a long time.

According to the new agreement, the minimum amount of the rent payable by the peasants to the landowners was increased to 12 denars per year; peasants who held larger plots were to pay 25 to 100 denars to their lords, which was equal to the sum payable before the uprising. The new agreement did not determine the "gifts" that the peasants were to give to the landowners, only stating that they were required to fulfill this obligation three times a year. The agreement confirmed the noblemen's right to administer justice to the peasants living in their estates, but also stipulated that the peasants could appeal against their lords' decision to the court of a nearby village or small town.

Last phase

The second agreement was again regarded as a provisional compromise by both parties. The charter prescribed that a joint delegation of the rebels and the noblemen should be sent to the king, who was staying in Prague, to seek hisarbitration

Arbitration is a form of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) that resolves disputes outside the judiciary courts. The dispute will be decided by one or more persons (the 'arbitrators', 'arbiters' or 'arbitral tribunal'), which renders the ' ...

. There is no evidence of the appointment of the delegates or their departure for Prague. Sigismund of Luxemburg died on 9 December 1437.

Knowing that their camp on the Szamos could easily be attacked, the rebels marched towards Kolozsvár in October or November. They invaded and pillaged the Báthorys' estates at Fejérd ( Feiurdeni). They also captured and beheaded many noblemen before attacking the abbey and forcing the abbot to flee. A group of rebels took possession of Nagyenyed with the assistance of its poor burghers and the inhabitants of the nearby villages. Most burghers of Kolozsvár also sympathized with the rebels, who thus entered the town without resistance. A Saxon charter recorded that Antal Nagy de Buda died fighting against the noblemen before 15 December. Demény refutes the credibility of the report, saying that all other sources indicate that the peasants were still resisting in January 1438.

The united armies of the new voivode, Desiderius Losonci, and Michael Jakcs laid siege to Kolozsvár. On 9 January, they sent a letter to the Saxon leaders, urging them to send reinforcements to contribute to the destruction of the "faithless peasants". During the siege, "not one soul could come out or go in" the town, according to the besiegers' report. The blockade caused a famine which forced the defenders to surrender before the end of January. The rebel groups around Nagyenyed were annihilated around the same time.

Aftermath and assessment

The delegates of the three Estates of Transylvania, noblemen (including the ennobled Saxons and Vlachs), Székelys, and Saxons, assembled at Torda on 2 February 1438. They confirmed their "brotherly union" against the rebellious peasants and the Ottoman marauders. Nine leaders of the revolt were executed at the assembly. Other defenders of Kolozsvár were mutilated. Taking advantage of the victory, the leaders of the noblemen also made attempts to harm their personal enemies. For instance, the voivode who wanted to seize some properties of the Báthorys accused them of having cooperated with the rebels. In retaliation for its support of the rebels, Kolozsvár was deprived of its municipal rights on 15 November. However, the burghers attained the restoration of their liberties with the support of

The delegates of the three Estates of Transylvania, noblemen (including the ennobled Saxons and Vlachs), Székelys, and Saxons, assembled at Torda on 2 February 1438. They confirmed their "brotherly union" against the rebellious peasants and the Ottoman marauders. Nine leaders of the revolt were executed at the assembly. Other defenders of Kolozsvár were mutilated. Taking advantage of the victory, the leaders of the noblemen also made attempts to harm their personal enemies. For instance, the voivode who wanted to seize some properties of the Báthorys accused them of having cooperated with the rebels. In retaliation for its support of the rebels, Kolozsvár was deprived of its municipal rights on 15 November. However, the burghers attained the restoration of their liberties with the support of John Hunyadi

John Hunyadi (, , , ; 1406 – 11 August 1456) was a leading Hungarian military and political figure in Central and Southeastern Europe during the 15th century. According to most contemporary sources, he was the member of a noble family of ...

on 21 September 1444.

Contemporaneous letters unanimously described the revolt as a peasant war against their lords. On 22 July 1437, the judge royal

The judge royal, also justiciar,Rady 2000, p. 49. chief justiceSegeš 2002, p. 202. or Lord Chief JusticeFallenbüchl 1988, p. 145. (german: Oberster Landesrichter,Fallenbüchl 1988, p. 72. hu, országbíró,Zsoldos 2011, p. 26. sk, krajinsk� ...

, Stephen Báthory

Stephen Báthory ( hu, Báthory István; pl, Stefan Batory; ; 27 September 1533 – 12 December 1586) was Voivode of Transylvania (1571–1576), Prince of Transylvania (1576–1586), King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania (1576–1586 ...

, referred to the Transylvanian events as the "peasants' war"; on 30 September, Roland Lépes mentioned that a nobleman had been wounded "in the general fight against the peasantry"; and Bishop Lépes wrote of the "war of the peasants" on 27 January 1439. Other documents (including the records of the meetings of the town council of Nagyenyed) emphasized that craftsmen and townspeople also joined the revolt. No contemporaneous source recorded that national hatreds played any role in the uprising. On the contrary, the cooperation of the Hungarian and Vlach commoners during the rebellion is well-documented. The first compromise between the rebels and the noblemen explicitly mentioned their common grievances. For instance, the rebels complained that "both the Hungarians and the Vlachs who lived near castles" had arbitrarily been compelled to pay the tithes on their swines and bees.

Historian Joseph Held states, the "conservative stance of the Transylvanian peasant movement was similar to late medieval peasant movements elsewhere in Europe". The peasants only wanted to secure the abolition of new seigneurial duties and the restoration of the traditional level of their taxes, without calling into question the basic structure of the society. On the other hand, Lajos Demény writes, the movement developed into a "general attack against feudal society" in Transylvania. Both historians conclude that the rebels could not achieve their principal purposes. The peasants' right to free movement was partially restored, but the landowners were again able to reduce it during the last decade of the century. According to historian Jean Sedlar, Vlach peasants "occupied the lowest rung of the social ladder, superior only to slaves" in medieval Transylvania because of their Orthodox faith. However, no merely ethnic prejudice prevented Vlachs from acquiring land and joining the Hungarian noble class, provided they accepted Catholicism and adopted a noble life-style. At the same time, the fact that upward mobility required the renunciation of Vlach identity clearly hindered this group from developing a sense of ethnic solidarity.

See also

*György Dózsa

György Dózsa (or ''György Székely'',appears as "Georgius Zekel" in old texts ro, Gheorghe Doja; 1470 – 20 July 1514) was a Székely man-at-arms (and by some accounts, a nobleman) from Transylvania, Kingdom of Hungary who led a peasa ...

*List of peasant revolts

This is a chronological list of conflicts in which peasants played a significant role.

Background

The history of peasant wars spans over two thousand years. A variety of factors fueled the emergence of the peasant revolt phenomenon, including:

...

*Popular revolts in late-medieval Europe

Popular revolts in late medieval Europe were uprisings and rebellions by (typically) peasants in the countryside, or the bourgeois in towns, against nobles, abbots and kings during the upheavals of the 14th through early 16th centuries, part of a ...

* Tuchin Revolt

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * *External links

Wealth of the winners

{{Authority control 1437 in Europe 1438 in Europe Battles involving Transylvania Conflicts in 1437 Conflicts in 1438 15th-century rebellions Medieval Transylvania Peasant revolts Popular revolt in late-medieval Europe Riots and civil disorder in Hungary Wars involving Hungary