Bronisław Malinowski on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

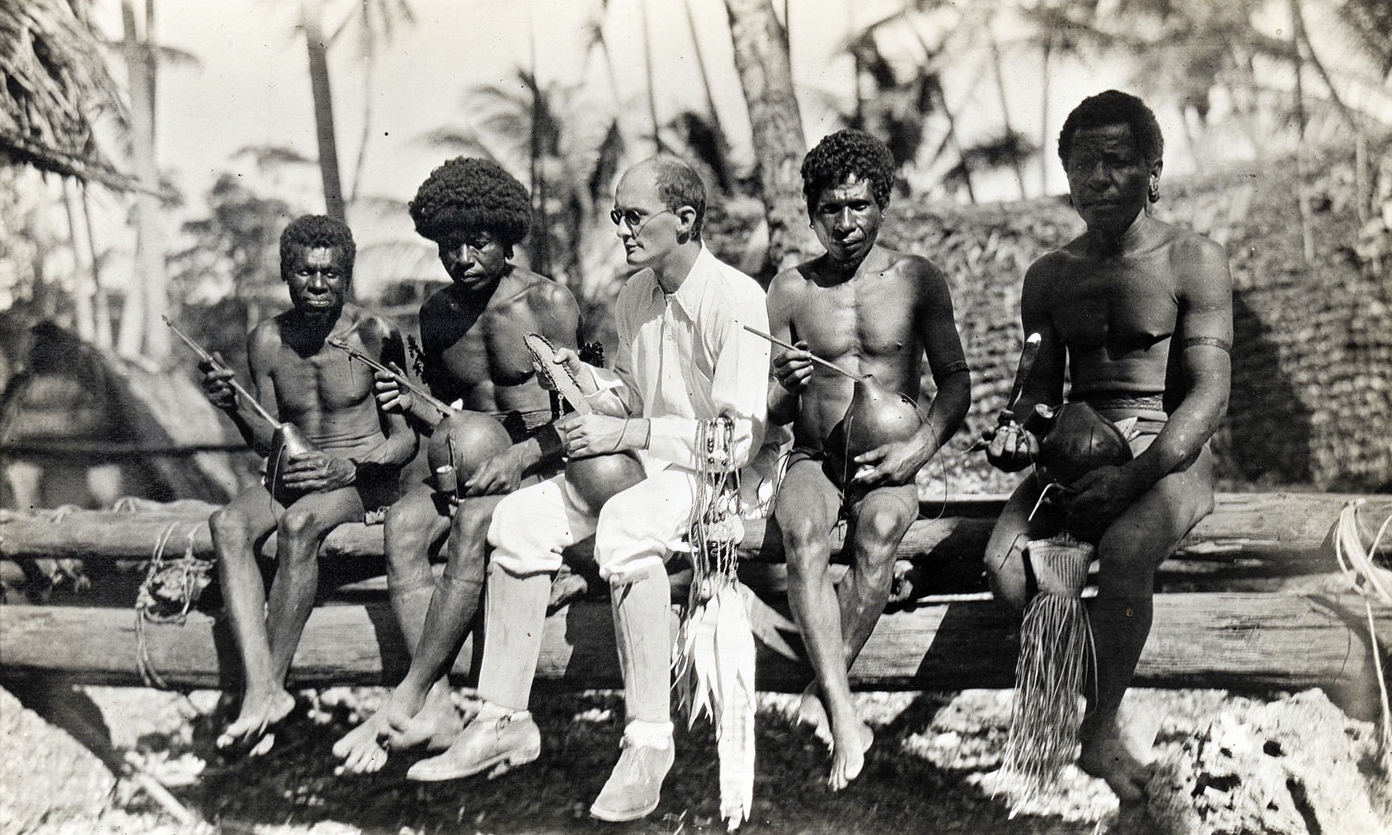

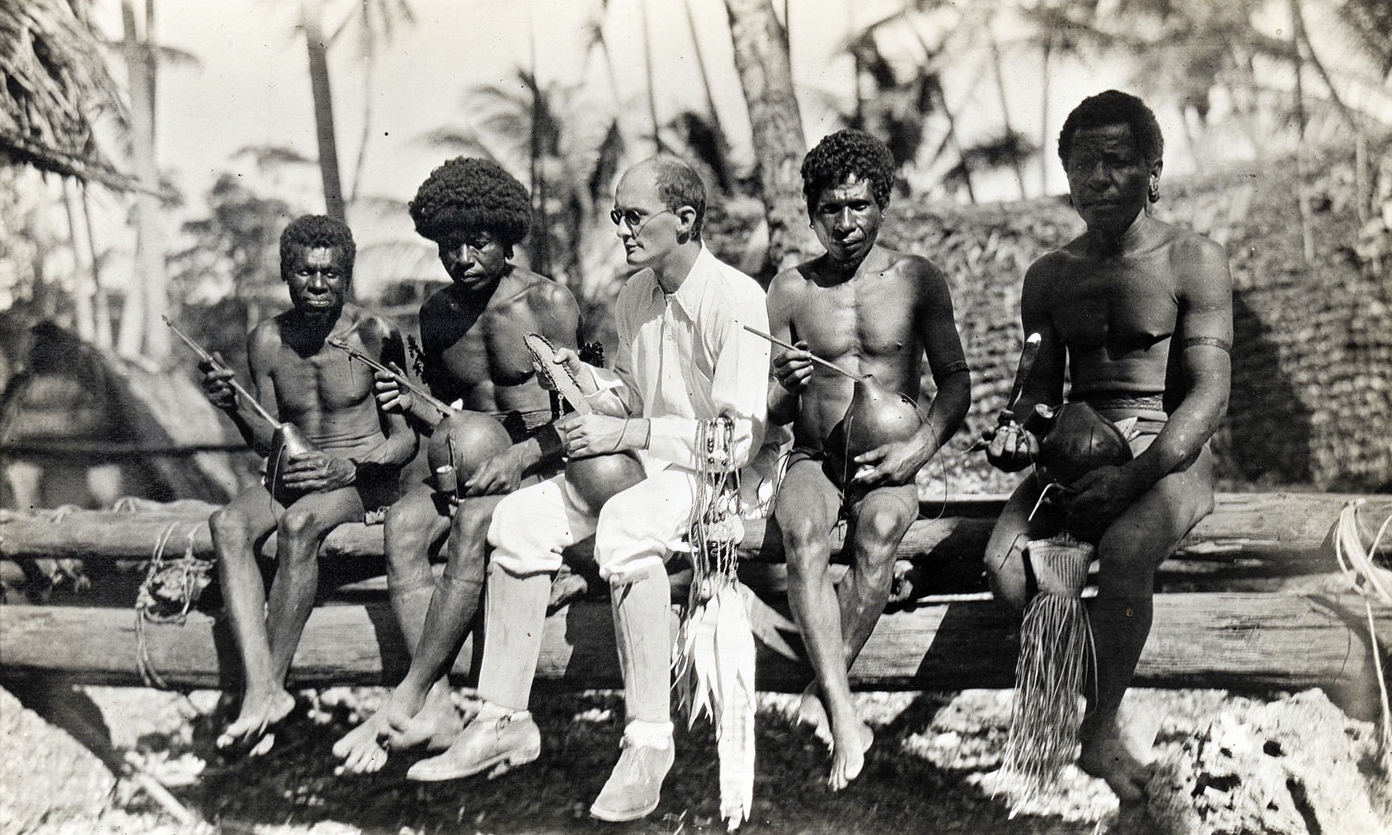

Bronisław Kasper Malinowski (; 7 April 1884 – 16 May 1942) was a Polish-British anthropologist and

/ref> As a child he was frail, often suffering from ill health, but excelled academically. On 30 May 1902 he passed his ''

In June 1914 he departed London, travelling to Australia, as the first step in his expedition to Papua (in what would later become

In June 1914 he departed London, travelling to Australia, as the first step in his expedition to Papua (in what would later become

In these two passages, Malinowski anticipated the distinction between description and analysis, and between the views of actors and analysts. This distinction continues to inform anthropological method and theory. His research from that period on the Trobriand traditional economy, with its particular focus on

In these two passages, Malinowski anticipated the distinction between description and analysis, and between the views of actors and analysts. This distinction continues to inform anthropological method and theory. His research from that period on the Trobriand traditional economy, with its particular focus on

“Before and After Malinowski: Alternative Views on the History of Anthropology [A Virtual Round Table at the Royal Anthropological Institute, London, 7 July 2022

/nowiki>”] (with the participation of Sophie Chevalier, Barbara Chambers Dawson, Thomas Hylland Eriksen, Michael Kraus, Adam Kuper, Herbert S. Lewis, Andrew Lyons, David Mills, David Shankland, James Urry, and Rosemary Lévy Zumwalt), ''BEROSE International Encyclopaedia of the Histories of Anthropology'', Paris.

Malinowski

Archive (Real audio stream) of

Baloma; the Spirits of the Dead in the Trobriand Islands

at sacred-texts.com

Papers of Bronislaw Malinowski held at LSE LibraryMalinowski's fieldwork photographs, Trobriand Islands, 1915–1918About the functional theory (selected chapters)Savage Memory – documentary about Malinowski's legacyMore Than Malinowski: Polish Cultural Anthropologists You Should Know

* Bronislaw Malinowski papers (MS 19). Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library. {{DEFAULTSORT:Malinowski, Bronislaw 1884 births 1942 deaths 19th-century anthropologists 19th-century non-fiction writers 20th-century anthropologists 20th-century non-fiction writers Academics of the London School of Economics Alumni of the London School of Economics Anthropologists of religion British agnostics British emigrants to Poland British emigrants to the United States British ethnographers British ethnologists Cornell University faculty Economic anthropologists Functionalism (social theory) Jagiellonian University alumni Members of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences Naturalised citizens of the United Kingdom Polish agnostics Polish anthropologists Polish Austro-Hungarians Polish emigrants to the United Kingdom Polish emigrants to the United States Polish ethnographers Polish ethnologists Scientists from Kraków Social anthropologists Trobriand Islands

ethnologist

Ethnology (from the grc-gre, ἔθνος, meaning 'nation') is an academic field that compares and analyzes the characteristics of different peoples and the relationships between them (compare cultural, social, or sociocultural anthropology) ...

whose writings on ethnography, social theory

Social theories are analytical frameworks, or paradigms, that are used to study and interpret social phenomena.Seidman, S., 2016. Contested knowledge: Social theory today. John Wiley & Sons. A tool used by social scientists, social theories rel ...

, and field research

Field research, field studies, or fieldwork is the collection of raw data outside a laboratory, library, or workplace setting. The approaches and methods used in field research vary across disciplines. For example, biologists who conduct f ...

have exerted a lasting influence on the discipline of anthropology.

Malinowski was born in what was part of the Austrian partition of Poland, and completed his initial studies at Jagiellonian University in his birth city of Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596 ...

. From 1910, at the London School of Economics

The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) is a public university, public research university located in London, England and a constituent college of the federal University of London. Founded in 1895 by Fabian Society members Sidn ...

(LSE), he studied exchange and economics, analysing Aboriginal Australia

The prehistory of Australia is the period between the first human habitation of the Australian continent and the colonisation of Australia in 1788, which marks the start of consistent written documentation of Australia. This period has been vari ...

through ethnographic documents. In 1914 he traveled to Australia. He conducted research in the Trobriand Islands

The Trobriand Islands are a archipelago of coral atolls off the east coast of New Guinea. They are part of the nation of Papua New Guinea and are in Milne Bay Province. Most of the population of 12,000 indigenous inhabitants live on the main isla ...

and other regions in New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; id, Papua, or , historically ) is the world's second-largest island with an area of . Located in Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is separated from Australia by the wide Torr ...

and Melanesia

Melanesia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It extends from Indonesia's New Guinea in the west to Fiji in the east, and includes the Arafura Sea.

The region includes the four independent countries of Fiji, Va ...

where he stayed for several years, studying indigenous culture

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

s.

Returning to England after World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, he published his principal work, ''Argonauts of the Western Pacific

''Argonauts of the Western Pacific: An Account of Native Enterprise and Adventure in the Archipelagoes of Melanesian New Guinea'' is a 1922 ethnological work by Bronisław Malinowski, which has had enormous impact on the ethnographic genre. The b ...

'' (1922), which established him as one of Europe's most important anthropologists. He took posts as lecturer and later as chair in anthropology at the LSE, attracting large numbers of students and exerting great influence on the development of British social anthropology. Over the years, he guest-lectured at several American universities; when World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

broke out, he remained in the United States, taking an appointment at Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Sta ...

. He died in 1942 and was interred in the United States. In 1967 his widow, Valetta Swann, published his personal diary kept during his fieldwork in Melanesia

Melanesia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It extends from Indonesia's New Guinea in the west to Fiji in the east, and includes the Arafura Sea.

The region includes the four independent countries of Fiji, Va ...

and New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; id, Papua, or , historically ) is the world's second-largest island with an area of . Located in Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is separated from Australia by the wide Torr ...

. It has since been a source of controversy, because of its ethnocentric and egocentric nature.

Malinowski's ethnography of the Trobriand Islands described the complex institution of the Kula ring

Kula, also known as the Kula exchange or Kula ring, is a ceremonial exchange system conducted in the Milne Bay Province of Papua New Guinea. The Kula ring was made famous by the father of modern anthropology, Bronisław Malinowski, who used this ...

and became foundational for subsequent theories of reciprocity and exchange. He was also widely regarded as an eminent fieldworker, and his texts regarding anthropological field methods were foundational to early anthropology, popularizing the concept of participatory observation. His approach to social theory

Social theories are analytical frameworks, or paradigms, that are used to study and interpret social phenomena.Seidman, S., 2016. Contested knowledge: Social theory today. John Wiley & Sons. A tool used by social scientists, social theories rel ...

was a form of psychological functionalism that emphasised how social and cultural institutions serve basic human needs—a perspective opposed to A. R. Radcliffe-Brown's structural functionalism

Structural functionalism, or simply functionalism, is "a framework for building theory that sees society as a complex system whose parts work together to promote solidarity and stability".

This approach looks at society through a macro-level o ...

, which emphasised ways in which social institutions function in relation to society as a whole.

Biography

Early life

Malinowski, scion of Polish '' szlachta'' (nobility), was born on 7 April 1884 inKraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596 ...

, in the Austrian partition

The Austrian Partition ( pl, zabór austriacki) comprise the former territories of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth acquired by the Habsburg monarchy during the Partitions of Poland in the late 18th century. The three partitions were conduct ...

of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth—then part of the Austro-Hungarian province known as the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria

The Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria,, ; pl, Królestwo Galicji i Lodomerii, ; uk, Королівство Галичини та Володимирії, Korolivstvo Halychyny ta Volodymyrii; la, Rēgnum Galiciae et Lodomeriae also known as ...

. His father, Lucjan Malinowski

Lucjan Feliks Malinowski (27 May 1839 in Jaroszewice, Poland – 15 January 1898 in Kraków) was a Polish linguist, a researcher of regional dialects of Silesia, a traveller, a professor of Jagiellonian University, from the 1887 principal S ...

, was a professor of Slavic philology

Philology () is the study of language in oral and written historical sources; it is the intersection of textual criticism, literary criticism, history, and linguistics (with especially strong ties to etymology). Philology is also defined as th ...

at the Jagiellonian University, and his mother was the daughter of a landowning family.Senft, Günter. 1997. Bronislaw Kasper Malinowski. in Verschueren, Ostman, Blommaert & Bulcaen (eds.) ''Handbook of Pragmatics'' Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamin/ref> As a child he was frail, often suffering from ill health, but excelled academically. On 30 May 1902 he passed his ''

matura

or its translated terms (''Mature'', ''Matur'', , , , , , ) is a Latin name for the secondary school exit exam or "maturity diploma" in various European countries, including Albania, Austria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, C ...

'' examinations (with distinction) at the Jan III Sobieski Secondary School, and later that year began studying at the College of Philosophy of Kraków's Jagiellonian University, where he initially focused on mathematics and the physical sciences.

While attending the university he became severely ill (possibly with tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, i ...

) and, while he recuperated, his interest turned more toward the social sciences

Social science is one of the branches of science, devoted to the study of societies and the relationships among individuals within those societies. The term was formerly used to refer to the field of sociology, the original "science of so ...

as he took courses in philosophy and education. In 1908 he received a doctorate in philosophy from the Jagiellonian University; his thesis was titled ''On the Principle of the Economy of Thought''.

During his student years he became interested in travel abroad, and visited Finland

Finland ( fi, Suomi ; sv, Finland ), officially the Republic of Finland (; ), is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of B ...

, Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

, the Canary Islands, western Asia, and North Africa; some of those travels were at least partly motivated by health concerns. He also spent three semesters at the University of Leipzig

Leipzig University (german: Universität Leipzig), in Leipzig in Saxony, Germany, is one of the world's oldest universities and the second-oldest university (by consecutive years of existence) in Germany. The university was founded on 2 Decemb ...

(ca. 1909-1910), where he studied under economist Karl Bücher

Karl Wilhelm Bücher (16 February 1847, Kirberg, Hesse – 12 November 1930, Leipzig, Saxony) was a German economist, one of the founders of non-market economics, and the founder of journalism as an academic discipline.

Biography

Early life ...

and psychologist Wilhelm Wundt. After reading James Frazer

Sir James George Frazer (; 1 January 1854 – 7 May 1941) was a Scottish social anthropologist and folklorist influential in the early stages of the modern studies of mythology and comparative religion.

Personal life

He was born on 1 Janua ...

's '' The Golden Bough'', he decided to become an anthropologist.

In 1910 he went to England, becoming a postgraduate student

Postgraduate or graduate education refers to academic or professional degrees, certificates, diplomas, or other qualifications pursued by post-secondary students who have earned an undergraduate (bachelor's) degree.

The organization and struc ...

at the London School of Economics

The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) is a public university, public research university located in London, England and a constituent college of the federal University of London. Founded in 1895 by Fabian Society members Sidn ...

, where his mentors included C. G. Seligman and Edvard Westermarck

Edvard Alexander Westermarck (Helsinki, 20 November 1862 – Tenala, 3 September 1939) was a Finnish philosopher and sociologist. Among other subjects, he studied exogamy and the incest taboo.

Biography

Westermarck was born in 1862 in a ...

.

Career

In 1911 Malinowski published, in Polish, his first academic paper, "''Totemizm i egzogamia''" ("Totemism and Exogamy"), in '' Lud''. The following year he published his first English-language academic paper, and in 1913 his first book, '' The Family among the Australian Aborigines'', and gave his first lectures at the LSE, on topics related topsychology of religion

Psychology of religion consists of the application of psychological methods and interpretive frameworks to the diverse contents of religious traditions as well as to both religious and irreligious individuals. The various methods and frameworks ...

and social psychology

Social psychology is the scientific study of how thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are influenced by the real or imagined presence of other people or by social norms. Social psychologists typically explain human behavior as a result of the ...

.

In June 1914 he departed London, travelling to Australia, as the first step in his expedition to Papua (in what would later become

In June 1914 he departed London, travelling to Australia, as the first step in his expedition to Papua (in what would later become Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea (abbreviated PNG; , ; tpi, Papua Niugini; ho, Papua Niu Gini), officially the Independent State of Papua New Guinea ( tpi, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niugini; ho, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niu Gini), is a country i ...

). The expedition was organized under the aegis of the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BAAS). In fact, initially Malinowski's journey to Australia was supposed to last only about half a year, as he was mainly planning on attending a conference there, and travelled there in a capacity of a secretary to Robert Ranulph Marett

Robert Ranulph Marett (13 June 1866 – 18 February 1943) was a British ethnologist and a proponent of the British Evolutionary School of cultural anthropology. Founded by Marett's older colleague, Edward Burnett Tylor, it asserted that mo ...

. Shortly afterward, his situation became complicated due to the outbreak of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

as although Polish by ethnicity, he was a subject of Austria-Hungary, which was at the state of war with the United Kingdom. Malinowski, at risk of internment, nonetheless decided not to return to Europe from the British-controlled region and after intervention by a number of his colleagues, including Marett as well as Alfred Cort Haddon, British authorities allowed him to stay in the Australian region and even provided him with new funding.

His first field trip, lasting from August 1914 to March 1915, took him to the Toulon Island ( Mailu Island) and the Woodlark Island

Woodlark Island, known to its inhabitants simply as Woodlark or Muyua, is the main island of the Woodlark Islands archipelago, located in Milne Bay Province and the Solomon Sea, Papua New Guinea.

Although no formal census has been conducted sinc ...

. This field trip was described in his 1915 monograph '' The natives of Mailu''. Subsequently, he conducted research in the Trobriand Islands

The Trobriand Islands are a archipelago of coral atolls off the east coast of New Guinea. They are part of the nation of Papua New Guinea and are in Milne Bay Province. Most of the population of 12,000 indigenous inhabitants live on the main isla ...

in the Melanesia

Melanesia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It extends from Indonesia's New Guinea in the west to Fiji in the east, and includes the Arafura Sea.

The region includes the four independent countries of Fiji, Va ...

region. He organized two larger expeditions during that time; from May 1915 to May 1916, and October 1917 to October 1918, in addition to several shorter excursions. It was during this period that he conducted his fieldwork on the Kula ring

Kula, also known as the Kula exchange or Kula ring, is a ceremonial exchange system conducted in the Milne Bay Province of Papua New Guinea. The Kula ring was made famous by the father of modern anthropology, Bronisław Malinowski, who used this ...

and advanced the practice of participant observation, which remains the hallmark of ethnographic research today. The ethnographic collection of artifacts from his expeditions is mostly held by the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

and the Melbourne Museum

The Melbourne Museum is a natural and cultural history museum located in the Carlton Gardens in Melbourne, Australia.

Located adjacent to the Royal Exhibition Building, the museum was opened in 2000 as a project of the Government of Victoria, ...

. During the breaks in between his expeditions he stayed in Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

, writing up his research, and publishing new articles, such as '' Baloma; the Spirits of the Dead in the Trobriand Islands''. In 1916 he received the title of Doctor of Sciences

Doctor of Sciences ( rus, доктор наук, p=ˈdoktər nɐˈuk, abbreviated д-р наук or д. н.; uk, доктор наук; bg, доктор на науките; be, доктар навук) is a higher doctoral degree in the Russi ...

.

In 1919, he returned to Europe, staying at Tenerife

Tenerife (; ; formerly spelled ''Teneriffe'') is the largest and most populous island of the Canary Islands. It is home to 43% of the total population of the archipelago. With a land area of and a population of 978,100 inhabitants as of Janu ...

for over a year before coming back to London on 1921. He resumed teaching at the London School of Economics

The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) is a public university, public research university located in London, England and a constituent college of the federal University of London. Founded in 1895 by Fabian Society members Sidn ...

, accepting a position as a lecturer, declining a job offer from the Polish Jagiellonian University. The following year, his book ''Argonauts of the Western Pacific

''Argonauts of the Western Pacific: An Account of Native Enterprise and Adventure in the Archipelagoes of Melanesian New Guinea'' is a 1922 ethnological work by Bronisław Malinowski, which has had enormous impact on the ethnographic genre. The b ...

'', often described as his masterpiece, was published. For the next two decades, he would establish the London School of Economics as Europe's main centre of anthropology. In 1924 he was promoted to a reader

A reader is a person who reads. It may also refer to:

Computing and technology

* Adobe Reader (now Adobe Acrobat), a PDF reader

* Bible Reader for Palm, a discontinued PDA application

* A card reader, for extracting data from various forms of ...

, and in 1927, a full professor. In 1930 he became a corresponding foreign member of the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences

The Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences or Polish Academy of Learning ( pl, Polska Akademia Umiejętności), headquartered in Kraków and founded in 1872, is one of two institutions in contemporary Poland having the nature of an academy of scien ...

. In 1933, he became a foreign member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences. In 1934 he travelled to Southern Africa, carrying out research among several tribes such as the Bemba, Kikuyu Kikuyu or Gikuyu (Gĩkũyũ) mostly refers to an ethnic group in Kenya or its associated language.

It may also refer to:

* Kikuyu people, a majority ethnic group in Kenya

*Kikuyu language, the language of Kikuyu people

*Kikuyu, Kenya, a town in Cent ...

, Maragoli

The Maragoli, or Logoli (''Ava-Logooli''), are now the second-largest ethnic group of the 6 million-strong Luhya nation in Kenya, numbering around 2.1 million, or 15% of the Luhya people according to the last Kenyan census. Their language i ...

, Maasai and the Swazi people

The Swazi or Swati ( Swati: ''Emaswati'', singular ''Liswati'') are a Bantu ethnic group native to Southern Africa, inhabiting Eswatini, a sovereign kingdom in Southern Africa. EmaSwati are part of the Nguni-language speaking peoples whose or ...

. The period 1926-1935 was the most productive time of his career, seeing the publications of many articles and several more books.

Malinowski taught intermittently in the United States, which he first visited in 1926. When World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

broke out during one of his American visits, he stayed there. In 1941 he carried out field research among the Mexican peasants in Oaxaca

Oaxaca ( , also , , from nci, Huāxyacac ), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Oaxaca ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Oaxaca), is one of the 32 states that compose the political divisions of Mexico, Federative Entities of Mexico. It is ...

. He took up a position at Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Sta ...

as a visiting professor, where he remained until his death. In 1942, he co-founded the Polish Institute of Arts and Sciences of America

The Polish Institute of Arts and Sciences of America (PIASA) is a Polish-American scholarly institution headquartered in Manhattan (New York City), at 208 East 30th Street.

History

The Institute was founded during the height of World War II, in 1 ...

of which he became its first president.

Malinowski died in New Haven, Connecticut

New Haven is a city in the U.S. state of Connecticut. It is located on New Haven Harbor on the northern shore of Long Island Sound in New Haven County, Connecticut and is part of the New York City metropolitan area. With a population of 134 ...

on 16 May 1942, aged 58, of a stroke while preparing to resume his fieldwork in Oaxaca. He was interred at Evergreen Cemetery in New Haven.

Works

Except a few works from the early 1910s, all of Malinowski's research was published in English. His first book, ''The Family among the Australian Aborigines'', published in 1913, was based on materials he collected and wrote in the years 1909-1911. It was well-received not just by contemporary reviewers, but also by scholars generations later. In 1963, in his foreword to its new edition,John Arundel Barnes

John Arundel Barnes M.A. D.Phil. DSC FBA (9 September 1918 – 13 September 2010) was an Australian and British social anthropologist. Until his death in 2010, Barnes held the post of Emeritus Professor of Sociology, Fellow of Churchill College ...

called it an epochal work, and noted how it discredited the previously held theory that Australian Aborigines

Aboriginal Australians are the various Indigenous peoples of the Australian mainland and many of its islands, such as Tasmania, Fraser Island, Hinchinbrook Island, the Tiwi Islands, and Groote Eylandt, but excluding the Torres Strait Isla ...

have no institution of family.

Published in 1922, ''Argonauts of the Western Pacific'', about the Trobriand people who live on the small Kiriwana island chain northeast of the island of New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; id, Papua, or , historically ) is the world's second-largest island with an area of . Located in Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is separated from Australia by the wide Torr ...

, was widely regarded as a masterpiece and significantly boosted Malinowski's reputation in the world of academia. His later books included the '' Crime and Custom in Savage Society'' (1926), '' Myth in Primitive Psychology'' (1926), '' Sex and Repression in Savage Society'' (1927), '' The Father in Primitive Psychology'' (1927), ''The Sexual Life of Savages in North-Western Melanesia

''The Sexual Life of Savages in North-Western Melanesia: An Ethnographic Account of Courtship, Marriage, and Family Life Among the Natives of the Trobriand Islands, British New Guinea'' is a 1929 book by anthropologist Bronisław Malinowski. The ...

'' (1929) and '' Coral Gardens and Their Magic'' (1935).

A number of his works were published posthumously, or collected in anthologies: '' A Scientific Theory of Culture and Others Essays'' (1944), '' Freedom & Civilization'' (1944), '' The Dynamics of Culture Change'' (1945), '' Magic, Science and Religion and Other Essays'' (1948), '' Sex, Culture, and Myth'' (1962) the controversial '' A Diary in the Strict Sense of the Term'' (1967) and '' The Early Writings of Bronislaw Malinowski'' (1993).

The personal diary of Malinowski, along with several others, written in Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, w ...

, was discovered in his Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Sta ...

office after his death. First published in 1967, covering the period of his fieldwork in 1914–1915 and 1917–1918 in New Guinea and the Trobriand Islands, it set off a storm of controversy. The year it was published Clifford Geertz called it "gross" and "tiresome", and wrote that it portrayed Malinowski as "a crabbed, self-preoccupied, hypochondriacal narcissist, whose fellow-feeling for the people he lived with was limited in the extreme." Two decades later, however, he praised it as "backstage masterpiece of anthropology, our ''The Double Helix

''The Double Helix: A Personal Account of the Discovery of the Structure of DNA'' is an autobiographical account of the discovery of the double helix structure of DNA written by James D. Watson and published in 1968. It has earned both critical ...

''". Writing in 1987, James Clifford called it "a crucial document for the history of anthropology".

Many of Malinowski's works entered public domain

The public domain (PD) consists of all the creative work to which no exclusive intellectual property rights apply. Those rights may have expired, been forfeited, expressly waived, or may be inapplicable. Because those rights have expired, ...

in 2013.

Ideas and influences

Already a year after his deathClyde Kluckhohn

Clyde Kluckhohn (; January 11, 1905 in Le Mars, Iowa – July 28, 1960 near Santa Fe, New Mexico), was an American anthropologist and social theorist, best known for his long-term ethnographic work among the Navajo and his contributions to the ...

described his influence in the field as significant if somewhat controversial, noting that to some he "was a major prophet", and that "no anthropologist has ever had so wide a popular audience". In 1974 Witold Armon described many of his works as "classics".

Ethnography and fieldwork

Malinowski is often considered one of anthropology's most skilled ethnographers, especially because of his highly methodical and well-theorised approach to the study of social systems. He is often referred to as the first researcher to bring anthropology " off the verandah" (a phrase that is also the name of a André Singer's 1986 documentary about his work), that is, stressing the need for fieldwork enabling the researcher to experience the everyday life of his subjects along with them. Malinowski emphasised the importance of detailed participant observation and argued that anthropologists must have daily contact with their informants if they are to adequately record the "imponderabilia of everyday life" that are so important to understanding a different culture. He stated that the goal of the anthropologist, or ethnographer, is "to grasp the native's point of view, his relation to life, to realize ''his'' vision of ''his'' world". Because of the impact of his argument, he is sometimes credited with inventing the field of ethnography. Malinowski in his pioneering research literally set up a tent in the middle of villages he studied, in which he lived for extended periods of times, weeks or months. His argument was shaped by his initial experiences as an anthropologist in the mid-1910s in Australia and Oceania, where during his first field trip he found himself grossly unprepared for it, due to not knowing the language of the people he set to study, nor being able to observe their daily customs sufficiently (during that initial trip, he was lodged with a local missionary and just made daily trips to the village, and endeavour which became increasingly difficult once he lost his translator). His pioneering decision to subsequently immerse himself in the life of the natives represents his solution to this problem, and was the message he addressed to new, young anthropologists, aiming to both improve their experience and allow them to produce better data. He advocated that stance from his very first publications, which were often harshly critical of those of his elders in the field of anthropology, who did most of their writing based on second-handed accounts. This could be seen in the relation between Frazer - an influential early anthropologist, nonetheless described as the classic armchair scholar - and Malinowski was complex; Frazer was one of Malinowski's mentors and supporters, and his work is credited with inspiring young Malinowski to become an anthropologist. At the same time, Malinowski was critical of Frazer from his early days, and it has been suggested that what he learned from Frazer was not "how to be an anthropologist" but "how not to do anthropology". Ian Jarvie wrote that many of Malinowski's writing represented an "attack" on Frazer's school of fieldwork, although James A. Boon suggested this conflict has been exaggerated.Functionalism and other theories

Malinowski has been credited with originating, or being one of the main originators, of the school of social anthropology known as functionalism. It has been suggested that here he has been inspired by the views ofWilliam James

William James (January 11, 1842 – August 26, 1910) was an American philosopher, historian, and psychologist, and the first educator to offer a psychology course in the United States.

James is considered to be a leading thinker of the lat ...

. In contrast to Radcliffe-Brown

Alfred Reginald Radcliffe-Brown, FBA (born Alfred Reginald Brown; 17 January 1881 – 24 October 1955) was an English social anthropologist who helped further develop the theory of structural functionalism.

Biography

Alfred Reginald Radcli ...

's structural functionalism

Structural functionalism, or simply functionalism, is "a framework for building theory that sees society as a complex system whose parts work together to promote solidarity and stability".

This approach looks at society through a macro-level o ...

, Malinowski's psychological functionalism argued that culture functioned to meet the needs of individuals rather than the needs of society as a whole. He reasoned that when the needs of individuals, who comprise society, are met, then the needs of society are met. To Malinowski, the feelings of people and their motives were crucial to understanding the way their society functioned:

Apart from fieldwork, Malinowski also challenged the claim to universality of Freud's theory of the Oedipus complex

The Oedipus complex (also spelled Œdipus complex) is an idea in psychoanalytic theory. The complex is an ostensibly universal phase in the life of a young boy in which, to try to immediately satisfy basic desires, he unconsciously wishes to hav ...

. He initiated a cross-cultural approach in '' Sex and Repression in Savage Society'' (1927) where he demonstrated that specific psychological complexes are not universal.

In 1920, he published his first scientific article on the Kula ring. In reference to the Kula ring, Malinowski also stated:

In these two passages, Malinowski anticipated the distinction between description and analysis, and between the views of actors and analysts. This distinction continues to inform anthropological method and theory. His research from that period on the Trobriand traditional economy, with its particular focus on

In these two passages, Malinowski anticipated the distinction between description and analysis, and between the views of actors and analysts. This distinction continues to inform anthropological method and theory. His research from that period on the Trobriand traditional economy, with its particular focus on magic

Magic or Magick most commonly refers to:

* Magic (supernatural), beliefs and actions employed to influence supernatural beings and forces

* Ceremonial magic, encompasses a wide variety of rituals of magic

* Magical thinking, the belief that unrela ...

and magicians, has also been described as a significant addition to the economic anthropology

Economic anthropology is a field that attempts to explain human economic behavior in its widest historic, geographic and cultural scope. It is an amalgamation of economics and anthropology. It is practiced by anthropologists and has a complex re ...

.

Malinowski likewise influenced the course of African history, serving as an academic mentor to Jomo Kenyatta, the father and first president of modern-day Kenya

)

, national_anthem = " Ee Mungu Nguvu Yetu"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Nairobi

, coordinates =

, largest_city = Nairobi

...

. Malinowski also wrote the introduction to ''Facing Mount Kenya'', Kenyatta's ethnographic study of the Gikuyu tribe.

In a brief passage in his 1979 book '' Broca's Brain'', the late science populariser Carl Sagan criticised Malinowski for thinking that "he had discovered a people in the Trobriand Islands who had not worked out the connection between sexual intercourse and childbirth", arguing that it was more likely that the islanders were simply making fun of Malinowski. Mark Mosko wrote in 2014 that further research on Trobriand people affirmed some of Malinowski's claims about their beliefs on procreation, adding that the dogmas are tied to a complicated system of belief encapsulating magic into beliefs about human and plant procreation, but he also stated that "the preponderance of ethnographic evidence ... refutes Malinowski’s notorious claims of Islanders’ supposed “ignorance of physiological paternity”".

Teacher

As a teacher, he preferred lectures to discussions. He has been praised for his friendly and egalitarian attitude towards women students. Among his students were such future prominent social scientists as Hilda Beemer Kuper, Edith Clarke, Kazimierz Dobrowolski,Raymond Firth

Sir Raymond William Firth (25 March 1901 – 22 February 2002) was an ethnologist from New Zealand. As a result of Firth's ethnographic work, actual behaviour of societies (social organization) is separated from the idealized rules of behaviou ...

, Meyer Fortes

Meyer Fortes FBA FRAI (25 April 1906 – 27 January 1983) was a South African-born anthropologist, best known for his work among the Tallensi and Ashanti in Ghana.

Originally trained in psychology, Fortes employed the notion of the "person ...

, Feliks Gross, Francis L. K. Hsu, Jomo Kenyatta, Edmund Leach

Sir Edmund Ronald Leach FRAI FBA (7 November 1910 – 6 January 1989) was a British social anthropologist and academic. He served as provost of King's College, Cambridge from 1966 to 1979. He was also president of the Royal Anthropologi ...

, Lucy Mair, Z. K. Matthews

Zachariah Keodirelang "ZK" Matthews (20 October 1901 – 11 May 1968) was a prominent black academic in South Africa, lecturing at South African Native College (renamed University of Fort Hare in 1955), where many future leaders of the African ...

, Józef Obrębski, Maria Ossowska

Maria Ossowska (''née'' Maria Niedźwiecka, 16 January 1896, Warsaw – 13 August 1974, Warsaw) was a Polish sociologist and social philosopher.

Life

A student of the philosopher Tadeusz Kotarbiński, she originally in 1925 received a doctorat ...

, Stanisław Ossowski, Ralph Piddington, Hortense Powdermaker

Hortense Powdermaker (December 24, 1900 – June 16, 1970) was an American anthropologist best known for her ethnographic studies of African Americans in rural America and of Hollywood.

Early life and education

Born to a Jewish family, Powdermak ...

, E. E. Evans-Pritchard, Margaret Read

Margaret Read (1892–1982) was the first female architect in Boulder, Colorado. Born in Iowa, she relocated with her parents to Boulder in 1910. After attending the University of Boulder for two years, she transferred to the University of Calif ...

, Audrey Richards

Audrey Isabel Richards, Commander of the Order of the British Empire, CBE, Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, FRAI, Fellow of the British Academy, FBA (8 July 1899 – 29 June 1984), was a pioneering British social an ...

, Isaac Schapera

Isaac Schapera FBA FRAI (23 June 1905 Garies, Cape Colony – 26 June 2003 London, England), was a social anthropologist at the London School of Economics specialising in South Africa. He was notable for his contributions of ethnographic an ...

, Andrzej Jan Waligórski, Camilla Wedgwood

Camilla Hildegarde Wedgwood (25 March 1901 – 17 May 1955) was a British anthropologist and academic administrator. She is best known for her research in the Pacific and her pioneering role as one of the British Commonwealth's first female an ...

, Monica Wilson

Monica Wilson, née Hunter (3 January 1908 – 26 October 1982) was a South African anthropologist, who was professor of social anthropology at the University of Cape Town.

Life

Monica Hunter was born to missionary parents in Lovedale in t ...

and Fei Xiaotong

Fei Xiaotong or Fei Hsiao-tung (November 2, 1910 – April 24, 2005) was a Chinese anthropologist and sociologist. He was a pioneering researcher and professor of sociology and anthropology; he was also noted for his studies in the study o ...

,.He is considered to have raised the next generation of anthropologists, particularly British.

Remembrance

The Malinowski Memorial Lecture, an annual anthropology lecture series atLondon School of Economics

The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) is a public university, public research university located in London, England and a constituent college of the federal University of London. Founded in 1895 by Fabian Society members Sidn ...

, inaugurated in 1959, is named after him. A student-led anthropology magazine at the LSE, ''The Argonaut'', took its name from Malinowski's ''Argonauts of the Western Pacific''.

The Society for Applied Anthropology

The Society for Applied Anthropology (SfAA) is a worldwide organization for the Applied Social Sciences, established "to promote the integration of anthropological perspectives and methods in solving human problems throughout the world; to advocate ...

established the Bronislaw Malinowski Award The Bronislaw Malinowski Award is an award given by the US-based Society for Applied Anthropology (SfAA) in honor of Bronisław Malinowski (1884–1942), an original member and strong supporter of the Society. Briefly established in 1950, the awar ...

in his honor in 1950. The award was awarded only until 1952, then went on hiatus until being re-established in 1973; it has been awarded annually since.

Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz

Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz (; 24 February 188518 September 1939), commonly known as Witkacy, was a Polish writer, painter, philosopher, theorist, playwright, novelist, and photographer active before World War I and during the interwar period.

...

based a character, Duke of Nevermore, from his novel '' The 622 Downfalls of Bungo or The Demonic Woman'' (written in the 1910s but not published until 1972) on Malinowski.

In 1957 Raymond Firth edited a book dedicated to the life and work of Malinowski, '' Man and Culture''.

The life and work of Malinowski is the subject of a documentary film

A documentary film or documentary is a non-fictional motion-picture intended to "document reality, primarily for the purposes of instruction, education or maintaining a historical record". Bill Nichols has characterized the documentary in te ...

''Tales From The Jungle: Malinowski'' aired by BBC Four channel in 2007.

Personal life

In 1919 Malinowski married Elsie Rosaline Masson, an Australian photographer, writer, and traveler (daughter ofDavid Orme Masson

Sir David Orme Masson KBE FRS FRSE LLD (13 January 1858 – 10 August 1937)L. W. Weickhardt,Masson, Sir David Orme (1858–1937), ''Australian Dictionary of Biography'', Volume 10, MUP, 1986, pp 432–435. Retrieved 6 October 2009 was a scie ...

), with whom he had three daughters: Józefa (born 1920), Wanda (born 1922), and Helena (born 1925). Elsie died in 1935, and in 1940 Malinowski married the English painter Valetta Swann. Malinowski's daughter Helena Malinowska Wayne wrote several articles and a book about her father's life.

While Malinowski was brought up in the Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

faith, after his mother's death he described himself as agnostic.

Selected publications

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *See also

*Maria Czaplicka

Maria Antonina Czaplicka (25 October 1884 – 27 May 1921), also referred to as Marya Antonina Czaplicka and Marie Antoinette Czaplicka, was a Polish cultural anthropologist who is best known for her ethnography of Siberian shamanism. Czaplicka ...

* Zofia Romer

Zofia Romer ''née'' Dembowska (February 16, 1885 – August 23, 1972) was a Polish painter. She was born in 1885 in Dorpat (now Tartu, Estonia) to well-known physician Tadeusz Dembowski and his wife Matylda. She grew up in Lithuania and Poland ...

* List of Poles

This is a partial list of notable Polish or Polish-speaking or -writing people. People of partial Polish heritage have their respective ancestries credited.

Science

Physics

* Czesław Białobrzeski

* Andrzej Buras

* Georges Charpa ...

* Archaeology of trade

Notes

References

Further reading

* * Vermeulen, Han F. & Frederico Delgado Rosa (eds.). 2022“Before and After Malinowski: Alternative Views on the History of Anthropology [A Virtual Round Table at the Royal Anthropological Institute, London, 7 July 2022

/nowiki>”] (with the participation of Sophie Chevalier, Barbara Chambers Dawson, Thomas Hylland Eriksen, Michael Kraus, Adam Kuper, Herbert S. Lewis, Andrew Lyons, David Mills, David Shankland, James Urry, and Rosemary Lévy Zumwalt), ''BEROSE International Encyclopaedia of the Histories of Anthropology'', Paris.

External links

* *Malinowski

Archive (Real audio stream) of

BBC Radio 4

BBC Radio 4 is a British national radio station owned and operated by the BBC that replaced the BBC Home Service in 1967. It broadcasts a wide variety of spoken-word programmes, including news, drama, comedy, science and history from the BBC' ...

edition of 'Thinking allowed' on MalinowskiBaloma; the Spirits of the Dead in the Trobriand Islands

at sacred-texts.com

Papers of Bronislaw Malinowski held at LSE Library

* Bronislaw Malinowski papers (MS 19). Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library. {{DEFAULTSORT:Malinowski, Bronislaw 1884 births 1942 deaths 19th-century anthropologists 19th-century non-fiction writers 20th-century anthropologists 20th-century non-fiction writers Academics of the London School of Economics Alumni of the London School of Economics Anthropologists of religion British agnostics British emigrants to Poland British emigrants to the United States British ethnographers British ethnologists Cornell University faculty Economic anthropologists Functionalism (social theory) Jagiellonian University alumni Members of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences Naturalised citizens of the United Kingdom Polish agnostics Polish anthropologists Polish Austro-Hungarians Polish emigrants to the United Kingdom Polish emigrants to the United States Polish ethnographers Polish ethnologists Scientists from Kraków Social anthropologists Trobriand Islands