British regional literature on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In literature regionalism refers to fiction or poetry that focuses on specific features, such as dialect, customs, history, and

In literature regionalism refers to fiction or poetry that focuses on specific features, such as dialect, customs, history, and

Amongst poets there is

Amongst poets there is

accessed 16 December 2008

/ref> * Wales ** Rhys Davies (1901–1978) – the

In literature regionalism refers to fiction or poetry that focuses on specific features, such as dialect, customs, history, and

In literature regionalism refers to fiction or poetry that focuses on specific features, such as dialect, customs, history, and landscape

A landscape is the visible features of an area of land, its landforms, and how they integrate with natural or man-made features, often considered in terms of their aesthetic appeal.''New Oxford American Dictionary''. A landscape includes the ...

, of a particular region (also called "local colour"). The setting

Setting may refer to:

* A location (geography) where something is set

* Set construction in theatrical scenery

* Setting (narrative), the place and time in a work of narrative, especially fiction

* Setting up to fail a manipulative technique to e ...

is particularly important in regional literature and the "locale is likely to be rural and/or provincial."

Development

Novelists

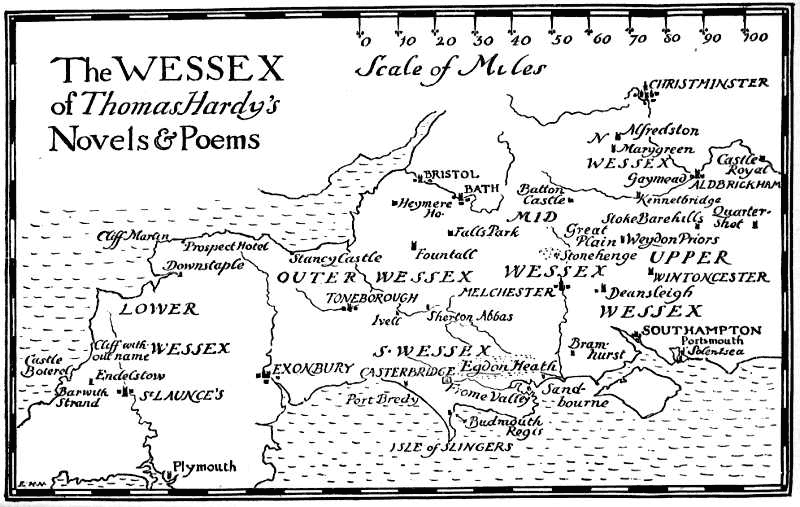

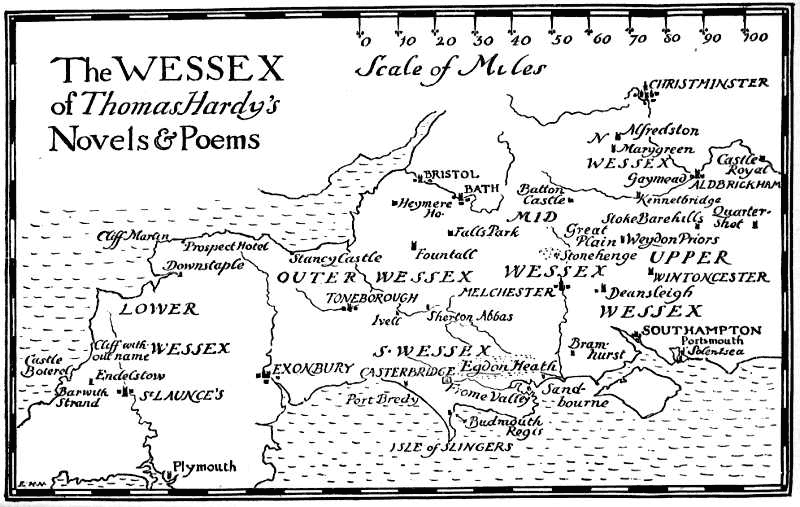

Thomas Hardy

Thomas Hardy (2 June 1840 – 11 January 1928) was an English novelist and poet. A Victorian realist in the tradition of George Eliot, he was influenced both in his novels and in his poetry by Romanticism, including the poetry of William Wor ...

's (1840–1928) novels can be described as regional because of the way he makes use of these elements in relation to a part of the West of England, that he names Wessex

la, Regnum Occidentalium Saxonum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of the West Saxons

, common_name = Wessex

, image_map = Southern British Isles 9th century.svg

, map_caption = S ...

. On the other hand, it seems much less appropriate to describe Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian er ...

(1812–1870) as a regional novelist of London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

and the south of England. John Cowper Powys

John Cowper Powys (; 8 October 187217 June 1963) was an English philosopher, lecturer, novelist, critic and poet born in Shirley, Derbyshire, where his father was vicar of the parish church in 1871–1879. Powys appeared with a volume of verse ...

has been seen as a successor to Thomas Hardy

Thomas Hardy (2 June 1840 – 11 January 1928) was an English novelist and poet. A Victorian realist in the tradition of George Eliot, he was influenced both in his novels and in his poetry by Romanticism, including the poetry of William Wor ...

, and '' Wolf Solent'', '' A Glastonbury Romance'' (1932), along with '' Weymouth Sands'' (1934) and '' Maiden Castle'' (1936), are often referred to as his Wessex

la, Regnum Occidentalium Saxonum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of the West Saxons

, common_name = Wessex

, image_map = Southern British Isles 9th century.svg

, map_caption = S ...

novels. As with Hardy's novels, the landscape

A landscape is the visible features of an area of land, its landforms, and how they integrate with natural or man-made features, often considered in terms of their aesthetic appeal.''New Oxford American Dictionary''. A landscape includes the ...

plays a major role in Powys's works, and an elemental philosophy is important in the lives of his characters. Powys's first novel ''Wood and Stone'' was dedicated to Thomas Hardy. ''Maiden Castle'', the last of the Wessex novels, is set in Dorchester, Thomas Hardy's Casterbridge, and which he intended to be a "rival" to Hardy's '' Mayor of Casterbridge''. Mary Butts

Mary Francis Butts, (13 December 1890 – 5 March 1937) also Mary Rodker by marriage, was an English modernist writer. Her work found recognition in literary magazines such as '' The Bookman'' and '' The Little Review'', as well as from fellow m ...

was a modernist novelist who works are also associated with the idea of Wessex. "Like ohn CowperPowys, she found a key to both personal and national identity by tuning into the deep history of the Dorset landscape ith emphasis onsacred places and folk traditions".

The regional novel is generally seen as originating with Maria Edgeworth and Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet, playwright and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European and Scottish literature, notably the novels '' Ivanhoe'', '' Rob Roy ...

, but their regions are hardily "comparable to Hardy's Wessex, Blackmore's Exmoor, or Arnold Bennett's potteries, .. becausethey are nations."

The term has also been used, in the past, disparagingly, especially with regard to women writers Women have made significant contributions to literature since the earliest written texts. Women have been at the forefront of textual communication since early civilizations.

History

Among the first known female writers is Enheduanna; she is also ...

, as a synonym for minor writing.

Other writers that have been characterized as regional novelists, are the Brontë sisters from West Yorkshire

West Yorkshire is a metropolitan and ceremonial county in the Yorkshire and Humber Region of England. It is an inland and upland county having eastward-draining valleys while taking in the moors of the Pennines. West Yorkshire came into exi ...

. In 1904, novelist Virginia Woolf

Adeline Virginia Woolf (; ; 25 January 1882 28 March 1941) was an English writer, considered one of the most important modernist 20th-century authors and a pioneer in the use of stream of consciousness as a narrative device.

Woolf was born ...

visited their birthplace Haworth

Haworth () is a village in the City of Bradford, West Yorkshire, England, in the Pennines, south-west of Keighley, west of Bradford and east of Colne in Lancashire. The surrounding areas include Oakworth and Oxenhope. Nearby villages inc ...

and published an account in ''The Guardian'' on 21 December. She remarked on the symbiosis between the village and the Brontë sisters. She wrote: "Haworth expresses the Brontës; the Brontës express Haworth; they fit like a snail to its shell".

Mary Webb

Mary Gladys Webb (25 March 1881 – 8 October 1927) was an English romance novelist and poet of the early 20th century, whose work is set chiefly in the Shropshire countryside and among Shropshire characters and people whom she knew. Her ...

(1881–1927), Margiad Evans

Margiad Evans was the pseudonym of Peggy Eileen Whistler (17 March 1909 – 17 March 1958), an English poet, novelist and illustrator with a lifelong identification with the Welsh border country.Ceridwen Lloyd-Morgan: 'Williams , Peggy Eileen a ...

(1909–1958) and Geraint Goodwin (1903–1942), are associate with the Welsh border region. George Eliot

Mary Ann Evans (22 November 1819 – 22 December 1880; alternatively Mary Anne or Marian), known by her pen name George Eliot, was an English novelist, poet, journalist, translator, and one of the leading writers of the Victorian era. She wrot ...

(1801–1886), on the other hand, is particularly associated with the rural English Midlands, whereas Arnold Bennett

Enoch Arnold Bennett (27 May 1867 – 27 March 1931) was an English author, best known as a novelist. He wrote prolifically: between the 1890s and the 1930s he completed 34 novels, seven volumes of short stories, 13 plays (some in collaboratio ...

(1867–1931) is the novelist of the Potteries in Staffordshire

Staffordshire (; postal abbreviation Staffs.) is a landlocked county in the West Midlands region of England. It borders Cheshire to the northwest, Derbyshire and Leicestershire to the east, Warwickshire to the southeast, the West Midlands C ...

, or the "Five Towns", (actually six) that now make-up Stoke-on-Trent

Stoke-on-Trent (often abbreviated to Stoke) is a city and Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority area in Staffordshire, England, with an area of . In 2019, the city had an estimated population of 256,375. It is the largest settlement ...

. R. D. Blackmore

Richard Doddridge Blackmore (7 June 1825 – 20 January 1900), known as R. D. Blackmore, was one of the most famous English novelists of the second half of the nineteenth century. He won acclaim for vivid descriptions and personification of the ...

(1825–1900), was one of the most famous English novelists of the second half of the nineteenth century, and he shared with Thomas Hardy

Thomas Hardy (2 June 1840 – 11 January 1928) was an English novelist and poet. A Victorian realist in the tradition of George Eliot, he was influenced both in his novels and in his poetry by Romanticism, including the poetry of William Wor ...

a Western England background and a strong sense of regional setting in his works. Noted for his eye for and sympathy with nature, critics of the time described this as one of the most striking features of his writings. He may be said to have done for Devon

Devon ( , historically known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South West England. The most populous settlement in Devon is the city of Plymouth, followed by Devon's county town, the city of Exeter. Devo ...

what Sir Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet, playwright and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European and Scottish literature, notably the novels '' Ivanhoe'', '' Rob Roy ...

did for the Highlands and Hardy for Wessex

la, Regnum Occidentalium Saxonum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of the West Saxons

, common_name = Wessex

, image_map = Southern British Isles 9th century.svg

, map_caption = S ...

. However, Blackmore is now remembered for one work, ''Lorna Doone

''Lorna Doone: A Romance of Exmoor'' is a novel by English author Richard Doddridge Blackmore, published in 1869. It is a romance based on a group of historical characters and set in the late 17th century in Devon and Somerset, particularly ar ...

''.

Catherine Cookson (1906 – 1998), who wrote about her deprived youth in South Tyneside

South Tyneside is a metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of Tyne and Wear, North East England.

It is bordered by all four other boroughs in Tyne and Wear – Gateshead to the west, Sunderland in the south, North Tyneside to the no ...

, County Durham

County Durham ( ), officially simply Durham,UK General Acts 1997 c. 23Lieutenancies Act 1997 Schedule 1(3). From legislation.gov.uk, retrieved 6 April 2022. is a ceremonial county in North East England.North East Assembly �About North East E ...

was one United Kingdom's most widely read novelists in the twentieth century. Sid Chaplin (1916–1986) is another writer from North-east England, who wrote, amongst other things, '' The Day of the Sardine'', published in 1961, which is set in a working-class community in Newcastle upon Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne ( RP: , ), or simply Newcastle, is a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England. The city is located on the River Tyne's northern bank and forms the largest part of the Tyneside built-up area. Newcastle is ...

, North Tyneside

North Tyneside is a metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of Tyne and Wear, England. It forms part of the greater Tyneside conurbation. North Tyneside Council is headquartered at Cobalt Park, Wallsend.

North Tyneside is bordered ...

at the very beginning of the 1960s.

Poets

Amongst poets there is

Amongst poets there is William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth (7 April 177023 April 1850) was an English Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped to launch the Romantic Age in English literature with their joint publication '' Lyrical Ballads'' (1798).

Wordsworth's ' ...

(1770–1850), and the other Lake Poets

The Lake Poets were a group of English poets who all lived in the Lake District of England, United Kingdom, in the first half of the nineteenth century. As a group, they followed no single "school" of thought or literary practice then known. They ...

, while the poet William Barnes

William Barnes (22 February 1801 – 7 October 1886) was an English polymath, writer, poet, philologist, priest, mathematician, engraving artist and inventor. He wrote over 800 poems, some in Dorset dialect, and much other work, including a co ...

(1801–1886) is seen as primarily a Dorset

Dorset ( ; archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a county in South West England on the English Channel coast. The ceremonial county comprises the unitary authority areas of Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole and Dorset. Covering an area of , ...

poet, especially because of his use of Dorset dialect

The term dialect (from Latin , , from the Ancient Greek word , 'discourse', from , 'through' and , 'I speak') can refer to either of two distinctly different types of linguistic phenomena:

One usage refers to a variety of a language that is ...

. John Clare

John Clare (13 July 1793 – 20 May 1864) was an English poet. The son of a farm labourer, he became known for his celebrations of the English countryside and sorrows at its disruption. His work underwent major re-evaluation in the late 20th ce ...

(1793 – 1864) was commonly known as "the Northamptonshire

Northamptonshire (; abbreviated Northants.) is a county in the East Midlands of England. In 2015, it had a population of 723,000. The county is administered by

two unitary authorities: North Northamptonshire and West Northamptonshire. It ...

Peasant Poet". His formal education was brief, his other employment and class-origins were lowly. Clare resisted the use of the increasingly standardised English grammar and orthography

An orthography is a set of conventions for writing a language, including norms of spelling, hyphenation, capitalization, word breaks, emphasis, and punctuation.

Most transnational languages in the modern period have a writing system, and ...

in his poetry and prose, alluding to political reasoning in comparing "grammar" (in a wider sense of orthography) to tyrannical government and slavery, personifying it in jocular fashion as a "bitch". He wrote in his Northamptonshire dialect, introducing local words to the literary canon such as "pooty" (snail), "lady-cow" (ladybird

Coccinellidae () is a widespread family of small beetles ranging in size from . They are commonly known as ladybugs in North America and ladybirds in Great Britain. Some entomologists prefer the names ladybird beetles or lady beetles as th ...

), "crizzle" (to crisp) and "throstle" (song thrush

The song thrush (''Turdus philomelos'') is a thrush that breeds across the West Palearctic. It has brown upper-parts and black-spotted cream or buff underparts and has three recognised subspecies. Its distinctive song, which has repeated musica ...

).

Alfred Tennyson (1809–1892) has been identified as a Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (abbreviated Lincs.) is a Counties of England, county in the East Midlands of England, with a long coastline on the North Sea to the east. It borders Norfolk to the south-east, Cambridgeshire to the south, Rutland to the south-we ...

poet, while Philip Larkin

Philip Arthur Larkin (9 August 1922 – 2 December 1985) was an English poet, novelist, and librarian. His first book of poetry, ''The North Ship'', was published in 1945, followed by two novels, ''Jill'' (1946) and ''A Girl in Winter'' (1947 ...

(1922–1985) is principally associated with the city of Hull. Basil Bunting's (1900–1985) semi-autobiographal poem '' Briggflatts'' can be read as a meditation on the limits of life and a celebration of Northumbrian culture and dialect, as symbolised by events and figures like the doomed Viking King Eric Bloodaxe

Eric Haraldsson ( non, Eiríkr Haraldsson , no, Eirik Haraldsson; died 954), nicknamed Bloodaxe ( non, blóðøx , no, Blodøks) and Brother-Slayer ( la, fratrum interfector), was a 10th-century Norwegian king. He ruled as King of Norway from ...

.

Ondaatje Prize

The Royal Society of Literature Ondaatje Prize is an annual literary award given by theRoyal Society of Literature

The Royal Society of Literature (RSL) is a learned society founded in 1820, by King George IV, to "reward literary merit and excite literary talent". A charity that represents the voice of literature in the UK, the RSL has about 600 Fellows, ele ...

. The £10,000 award is given for a work of fiction, non-fiction or poetry which evokes the "spirit of a place", and which is written by someone who is a citizen of or who has been resident in the Commonwealth or the Republic of Ireland. The prize bears the name of its benefactor Christopher Ondaatje and incorporates the Winifred Holtby Memorial Prize

The Winifred Holtby Memorial Prize was presented from 1967 until 2003 by the Royal Society of Literature for the best regional novel of the year. It is named after the novelist Winifred Holtby who was noted for her novels set in the rural scenes o ...

which was presented up to 2002 for regional fiction.

Other British regional novelists

Other British regional novelists: * North of England: ** Phyllis Bentley (1894–1977) – theWest Riding of Yorkshire

The West Riding of Yorkshire is one of three historic subdivisions of Yorkshire, England. From 1889 to 1974 the administrative county County of York, West Riding (the area under the control of West Riding County Council), abbreviated County ...

** Harold Heslop (1898–1983) – Durham Durham most commonly refers to:

*Durham, England, a cathedral city and the county town of County Durham

*County Durham, an English county

* Durham County, North Carolina, a county in North Carolina, United States

*Durham, North Carolina, a city in N ...

** James Hanley (1897–1985) – Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

, Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated Lancs) is the name of a historic county, ceremonial county, and non-metropolitan county in North West England. The boundaries of these three areas differ significantly.

The non-metropolitan county of Lancas ...

** Constance Holme (1881–1955) – Westmorland

Westmorland (, formerly also spelt ''Westmoreland'';R. Wilkinson The British Isles, Sheet The British IslesVision of Britain/ref> is a historic county in North West England spanning the southern Lake District and the northern Dales. It had an ...

** Winifred Holtby (1898–1935) – East Riding of Yorkshire

The East Riding of Yorkshire, or simply East Riding or East Yorkshire, is a ceremonial county and unitary authority area in the Yorkshire and the Humber region of England. It borders North Yorkshire to the north and west, South Yorkshire t ...

** Storm Jameson

Margaret Ethel Storm Jameson (8 January 1891 – 30 September 1986) was an English journalist and author, known for her novels and reviews and for her work as President of English PEN between 1938 and 1944.

Life and career

Jameson was born in ...

(1891–1986) – Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a Historic counties of England, historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other Eng ...

** Oliver Onions (1873–1961) – Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a Historic counties of England, historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other Eng ...

** Elizabeth Gaskell

Elizabeth Cleghorn Gaskell (''née'' Stevenson; 29 September 1810 – 12 November 1865), often referred to as Mrs Gaskell, was an English novelist, biographer and short story writer. Her novels offer a detailed portrait of the lives of many st ...

( 1810 – 1865) – Cheshire

Cheshire ( ) is a ceremonial and historic county in North West England, bordered by Wales to the west, Merseyside and Greater Manchester to the north, Derbyshire to the east, and Staffordshire and Shropshire to the south. Cheshire's county tow ...

and Lancashire

** Howard Spring

Howard Spring (10 February 1889 – 3 May 1965) was a Welsh author and journalist who wrote in English. He began his writing career as a journalist but from 1934 produced a series of best-selling novels for adults and children. The most su ...

(1889–1965) – Lancashire

Lancashire ( , ; abbreviated Lancs) is the name of a historic county, ceremonial county, and non-metropolitan county in North West England. The boundaries of these three areas differ significantly.

The non-metropolitan county of Lancas ...

** Leo Walmsley

Leo Walmsley (29 September 1892–8 June 1966) was an English writer. Walmsley was born in Shipley, West Riding of Yorkshire, but brought up in Robin Hood's Bay in the North Riding. Noted for his fictional ''Bramblewick'' series, based on Ro ...

(1892–1966) – Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ; abbreviated Yorks), formally known as the County of York, is a Historic counties of England, historic county in northern England and by far the largest in the United Kingdom. Because of its large area in comparison with other Eng ...

North coast

**Hugh Walpole

Sir Hugh Seymour Walpole, Commander of the Order of the British Empire, CBE (13 March 18841 June 1941) was an English novelist. He was the son of an Anglican clergyman, intended for a career in the church but drawn instead to writing. Among th ...

(1884–1941) – Cumberland

Cumberland ( ) is a historic counties of England, historic county in the far North West England. It covers part of the Lake District as well as the north Pennines and Solway Firth coast. Cumberland had an administrative function from the 12th c ...

* Midlands:

** H. E. Bates

Herbert Ernest Bates (16 May 1905 – 29 January 1974), better known as H. E. Bates, was an English writer. His best-known works include ''Love for Lydia'', '' The Darling Buds of May'', and ''My Uncle Silas''.

Early life

H.E. Bates was ...

(1905–1974) – Northamptonshire

Northamptonshire (; abbreviated Northants.) is a county in the East Midlands of England. In 2015, it had a population of 723,000. The county is administered by

two unitary authorities: North Northamptonshire and West Northamptonshire. It ...

** D. H. Lawrence

David Herbert Lawrence (11 September 1885 – 2 March 1930) was an English writer, novelist, poet and essayist. His works reflect on modernity, industrialization, sexuality, emotional health, vitality, spontaneity and instinct. His best-k ...

(1885–1930) – Nottinghamshire

Nottinghamshire (; abbreviated Notts.) is a landlocked county in the East Midlands region of England, bordering South Yorkshire to the north-west, Lincolnshire to the east, Leicestershire to the south, and Derbyshire to the west. The trad ...

* West of England:

**Mary Butts

Mary Francis Butts, (13 December 1890 – 5 March 1937) also Mary Rodker by marriage, was an English modernist writer. Her work found recognition in literary magazines such as '' The Bookman'' and '' The Little Review'', as well as from fellow m ...

(1890 – 1937) – Dorset

Dorset ( ; archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a county in South West England on the English Channel coast. The ceremonial county comprises the unitary authority areas of Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole and Dorset. Covering an area of , ...

** Joseph Hocking - Cornwall

** Winston Graham

Winston Mawdsley Graham OBE, born Winston Grime (30 June 1908 – 10 July 2003), was an English novelist best known for the Poldark series of historical novels set in Cornwall, though he also wrote numerous other works, including contemporary ...

(1909–2003) – Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a Historic counties of England, historic county and Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people ...

** Richard Jefferies

John Richard Jefferies (6 November 1848 – 14 August 1887) was an English nature writer, noted for his depiction of English rural life in essays, books of natural history, and novels. His childhood on a small Wiltshire farm had a great influ ...

(1848 – 1887) – Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated Wilts) is a historic and ceremonial county in South West England with an area of . It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset to the southwest, Somerset to the west, Hampshire to the southeast, Gloucestershire ...

** Katharine Lee (Kitty Lee Jenner, 1854–1936) - Cornwall

** Daphne du Maurier

Dame Daphne du Maurier, Lady Browning, (; 13 May 1907 – 19 April 1989) was an English novelist, biographer and playwright. Her parents were actor-manager Sir Gerald du Maurier and his wife, actress Muriel Beaumont. Her grandfather was Geo ...

(1907–1989) – West Country

The West Country (occasionally Westcountry) is a loosely defined area of South West England, usually taken to include all, some, or parts of the counties of Cornwall, Devon, Dorset, Somerset, Bristol, and, less commonly, Wiltshire, Glouc ...

** Eden Philpotts (1862–1960) – Dartmoor

Dartmoor is an upland area in southern Devon, England. The moorland and surrounding land has been protected by National Park status since 1951. Dartmoor National Park covers .

The granite which forms the uplands dates from the Carboniferous P ...

, Devon

Devon ( , historically known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South West England. The most populous settlement in Devon is the city of Plymouth, followed by Devon's county town, the city of Exeter. Devo ...

** T. F. Powys ( 1875–1953) – Dorset

Dorset ( ; archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a county in South West England on the English Channel coast. The ceremonial county comprises the unitary authority areas of Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole and Dorset. Covering an area of , ...

** Arthur Quiller-Couch - Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a Historic counties of England, historic county and Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people ...

** Silas Hocking - CornwallR. G. Burnett, 'Hocking, Silas Kitto (1850–1935)’, rev. Sayoni Basu, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

, Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the university press of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world, and its printing history dates back to the 1480s. Having been officially granted the legal right to print book ...

, 2004; online edn, May 200accessed 16 December 2008

/ref> * Wales ** Rhys Davies (1901–1978) – the

Rhondda Valley

Rhondda , or the Rhondda Valley ( cy, Cwm Rhondda ), is a former coalmining area in South Wales, historically in the county of Glamorgan. It takes its name from the River Rhondda, and embraces two valleys – the larger Rhondda Fawr valley ('' ...

, South Wales

South Wales ( cy, De Cymru) is a loosely defined region of Wales bordered by England to the east and mid Wales to the north. Generally considered to include the historic counties of Glamorgan and Monmouthshire, south Wales extends westwards ...

** Lewis Jones (1897–1939) – South Wales

South Wales ( cy, De Cymru) is a loosely defined region of Wales bordered by England to the east and mid Wales to the north. Generally considered to include the historic counties of Glamorgan and Monmouthshire, south Wales extends westwards ...

** Gwyn Thomas (1913–1981) – the Rhondda Valley

Rhondda , or the Rhondda Valley ( cy, Cwm Rhondda ), is a former coalmining area in South Wales, historically in the county of Glamorgan. It takes its name from the River Rhondda, and embraces two valleys – the larger Rhondda Fawr valley ('' ...

** Gwyn Jones (1907–1999) – South Wales

South Wales ( cy, De Cymru) is a loosely defined region of Wales bordered by England to the east and mid Wales to the north. Generally considered to include the historic counties of Glamorgan and Monmouthshire, south Wales extends westwards ...

** Jack Jones Jack Jones may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Music

*Jack Jones (American singer) (born 1938), American jazz and pop singer

*Jack Jones, stage name of Australian singer Irwin Thomas (born 1971)

*Jack Jones (Welsh musician) (born 1992), Welsh mu ...

(1884–1970) – Merthyr Tydfil

Merthyr Tydfil (; cy, Merthyr Tudful ) is the main town in Merthyr Tydfil County Borough, Wales, administered by Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council. It is about north of Cardiff. Often called just Merthyr, it is said to be named after T ...

, South Wales

South Wales ( cy, De Cymru) is a loosely defined region of Wales bordered by England to the east and mid Wales to the north. Generally considered to include the historic counties of Glamorgan and Monmouthshire, south Wales extends westwards ...

* Scotland:

** Lewis Grassic Gibbon

Lewis Grassic Gibbon was the pseudonym of James Leslie Mitchell (13 February 1901 – 7 February 1935), a Scottish writer. He was best known for ''A Scots Quair'', a trilogy set in the north-east of Scotland in the early 20th century, of which ...

(1901–1935) – The Mearns

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things already mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in English. ''The'' is the ...

: The County of Kincardine, Scotland

**Nan Shepherd

Anna "Nan" Shepherd (11 February 1893 – 27 February 1981) was a Scottish Modernist writer and poet, best known for her seminal mountain memoir, ''The Living Mountain'', based on experiences of hill walking in the Cairngorms. This is noted as a ...

(1893–1981) – Cairngorm Mountains

The Cairngorms ( gd, Am Monadh Ruadh) are a mountain range in the eastern Highlands of Scotland closely associated with the mountain Cairn Gorm. The Cairngorms became part of Scotland's second national park (the Cairngorms National Park) on 1 ...

, Scotland

* South East

** East End Literature (London, England)

** Sheila Kaye-Smith (1887–1956) – the border of Sussex

Sussex (), from the Old English (), is a historic county in South East England that was formerly an independent medieval Anglo-Saxon kingdom. It is bounded to the west by Hampshire, north by Surrey, northeast by Kent, south by the Englis ...

and Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

See also

*American Literary Regionalism

American literary regionalism or local color is a style or genre of writing in the United States that gained popularity in the mid to late 19th century into the early 20th century. In this style of writing, which includes both poetry and prose, the ...

* '' Criollismo'' in Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived ...

* Nationalisms and regionalisms of Spain

Both the perceived nationhood of Spain, and the perceived distinctions between different parts of its territory derive from historical, geographical, linguistic, economic, political, ethnic and social factors.

Present-day Spain was formed in the ...

* Regional literature of France

References

{{ReflistBibliography

* Bellamy, Liz, ''Regionalism and Nationalism: Maria Edgeworth, Walter Scott and the definition of Britishness''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. * Bentley, Phyllis Eleanor, ''The English regional novel'' 1894–1977. London: Allen & Unwin,941

Year 941 ( CMXLI) was a common year starting on Friday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place

Byzantine Empire

* May – September – Rus'–Byzantine War: The Rus' and their allies, th ...

* Keith, W. J., ''Regions of the imagination: the development of British rural fiction''. Toronto; Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, c1988.

* Pite, Ralph, ''Hardy's geography: Wessex and the regional novel''. Palgrave, 2002.

* Radford, Andrew D., ''Mapping the Wessex novel: landscape, history and the parochial in British literature'', 1870–1940. London; New York: Continuum International Pub., 2010.

* Snell, K. D. M., ''The regional novel in Britain and Ireland''. 1800–1990. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998;

** and ''The Bibliography of Regional Fiction in Britain and Ireland'': 1800–2000. Aldershott: Ashgate, 2002.

British literature