British literature is

literature

Literature is any collection of Writing, written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to ...

from the

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and No ...

, the

Isle of Man

)

, anthem = " O Land of Our Birth"

, image = Isle of Man by Sentinel-2.jpg

, image_map = Europe-Isle_of_Man.svg

, mapsize =

, map_alt = Location of the Isle of Man in Europe

, map_caption = Location of the Isle of Man (green)

in Europ ...

, and the

Channel Islands

The Channel Islands ( nrf, Îles d'la Manche; french: îles Anglo-Normandes or ''îles de la Manche'') are an archipelago in the English Channel, off the French coast of Normandy. They include two Crown Dependencies: the Bailiwick of Jersey, ...

. This article covers British literature in the

English language

English is a West Germanic language of the Indo-European language family, with its earliest forms spoken by the inhabitants of early medieval England. It is named after the Angles, one of the ancient Germanic peoples that migrated to the ...

. Anglo-Saxon (

Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers in the mid-5th ...

) literature is included, and there is some discussion of

Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

and

Anglo-Norman Anglo-Norman may refer to:

*Anglo-Normans, the medieval ruling class in England following the Norman conquest of 1066

*Anglo-Norman language

**Anglo-Norman literature

*Anglo-Norman England, or Norman England, the period in English history from 1066 ...

literature, where literature in these languages relate to the early development of the

English language

English is a West Germanic language of the Indo-European language family, with its earliest forms spoken by the inhabitants of early medieval England. It is named after the Angles, one of the ancient Germanic peoples that migrated to the ...

and

literature

Literature is any collection of Writing, written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to ...

. There is also some brief discussion of major figures who wrote in

Scots, but the main discussion is in the various

Scottish literature articles.

The article

Literature in the other languages of Britain focuses on the literatures written in the other languages that are, and have been, used in Britain. There are also articles on these various literatures:

Latin literature in Britain,

Anglo-Norman Anglo-Norman may refer to:

*Anglo-Normans, the medieval ruling class in England following the Norman conquest of 1066

*Anglo-Norman language

**Anglo-Norman literature

*Anglo-Norman England, or Norman England, the period in English history from 1066 ...

,

Cornish,

Guernésiais,

Jèrriais,

Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

,

Manx,

Scottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic ( gd, Gàidhlig ), also known as Scots Gaelic and Gaelic, is a Goidelic language (in the Celtic branch of the Indo-European language family) native to the Gaels of Scotland. As a Goidelic language, Scottish Gaelic, as well as ...

,

Welsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, referring or related to Wales

* Welsh language, a Brittonic Celtic language spoken in Wales

* Welsh people

People

* Welsh (surname)

* Sometimes used as a synonym for the ancient Britons (Celtic peopl ...

, etc.

Irish writers

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

*** Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent u ...

have played an important part in the development of literature in England and

Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, but though the whole of

Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

was politically part of the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

between January 1801 and December 1922, it can be controversial to describe

Irish literature as British. For some this includes works by authors from

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label=Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is #Descriptions, variously described as ...

.

British identity

The nature of

British identity has changed over time. The island that contains

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

,

Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, and

Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the Bristol Channel to the south. It had a population in ...

has been known as

Britain from the time of the

Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lett ...

Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic ' ...

(–79).

[Pliny the Elder's ''Naturalis Historia'' Book IV. Chapter XL]

Latin text

an

English translation

numbered Book 4, Chapter 30,

at the Perseus Project. English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

as the national language had its beginnings with the

Anglo-Saxon invasion which started around AD 450. Before that, the inhabitants mainly spoke various

Celtic languages

The Celtic languages (usually , but sometimes ) are a group of related languages descended from Proto-Celtic. They form a branch of the Indo-European language family. The term "Celtic" was first used to describe this language group by Edward ...

. The various constituent parts of the present

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

joined at different times. Wales was annexed by the

Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England (, ) was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from 12 July 927, when it emerged from various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain.

On ...

under the

Acts of Union of 1536 and 1542. However, it was not until 1707 with

a treaty between England and

Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, that the

Kingdom of Great Britain

The Kingdom of Great Britain (officially Great Britain) was a sovereign country in Western Europe from 1 May 1707 to the end of 31 December 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of Union 1707, wh ...

came into existence. This merged in January 1801 with the

Kingdom of Ireland

The Kingdom of Ireland ( ga, label=Classical Irish, an Ríoghacht Éireann; ga, label= Modern Irish, an Ríocht Éireann, ) was a monarchy on the island of Ireland that was a client state of England and then of Great Britain. It existed from ...

to form the

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was a sovereign state in the British Isles that existed between 1801 and 1922, when it included all of Ireland. It was established by the Acts of Union 1800, which merged the Kingdom of Grea ...

. Until fairly recent times Celtic languages continued to be spoken widely in Scotland, Wales, Cornwall, and Ireland, and these languages still survive, especially in parts of Wales.

Subsequently,

Irish nationalism led to the

partition of the island of Ireland in 1921; thus literature of the

Republic of Ireland

Ireland ( ga, Éire ), also known as the Republic of Ireland (), is a country in north-western Europe consisting of 26 of the 32 counties of the island of Ireland. The capital and largest city is Dublin, on the eastern side of the island. ...

is not British, although literature from

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label=Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is #Descriptions, variously described as ...

is both Irish and British.

, especially if their subject matter relates to Wales, has been recognised as a distinctive entity since the 20th century. The need for a separate identity for this kind of writing arose because of the parallel development of modern

Welsh-language literature.

Because Britain was a

colonial power the use of English spread through the world; from the 19th century or earlier in the United States, and later in other former colonies, major writers in English began to appear beyond the boundaries of Britain and

Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

; later these included Nobel laureates.

The coming of the Anglo-Saxons: 449–c.1066

The other languages of early Britain

Although the

Romans withdrew from Britain in the early 5th century,

Latin literature

Latin literature includes the essays, histories, poems, plays, and other writings written in the Latin language. The beginning of formal Latin literature dates to 240 BC, when the first stage play in Latin was performed in Rome. Latin literature ...

, mostly ecclesiastical, continued to be written, including

Chronicle

A chronicle ( la, chronica, from Greek ''chroniká'', from , ''chrónos'' – "time") is a historical account of events arranged in chronological order, as in a timeline. Typically, equal weight is given for historically important events and ...

s by

Bede

Bede ( ; ang, Bǣda , ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, The Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable ( la, Beda Venerabilis), was an English monk at the monastery of St Peter and its companion monastery of St Paul in the Kingdom ...

(672/3–735), ''

Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum''; and

Gildas (–570), ''

De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae

''De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae'' ( la, On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain, sometimes just ''On the Ruin of Britain'') is a work written in Latin by the 6th-century AD British cleric St Gildas. It is a sermon in three parts condemning ...

''.

Various

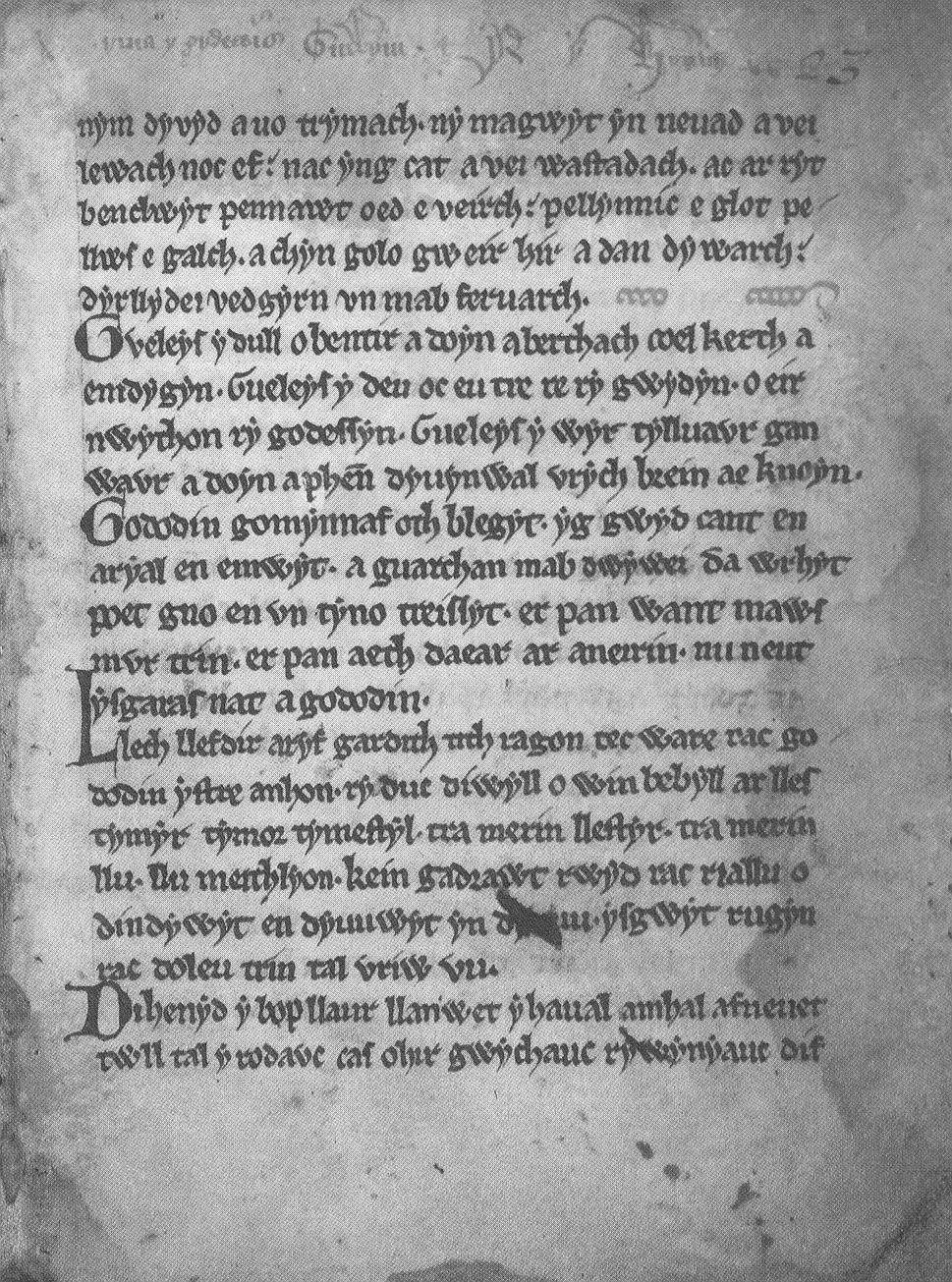

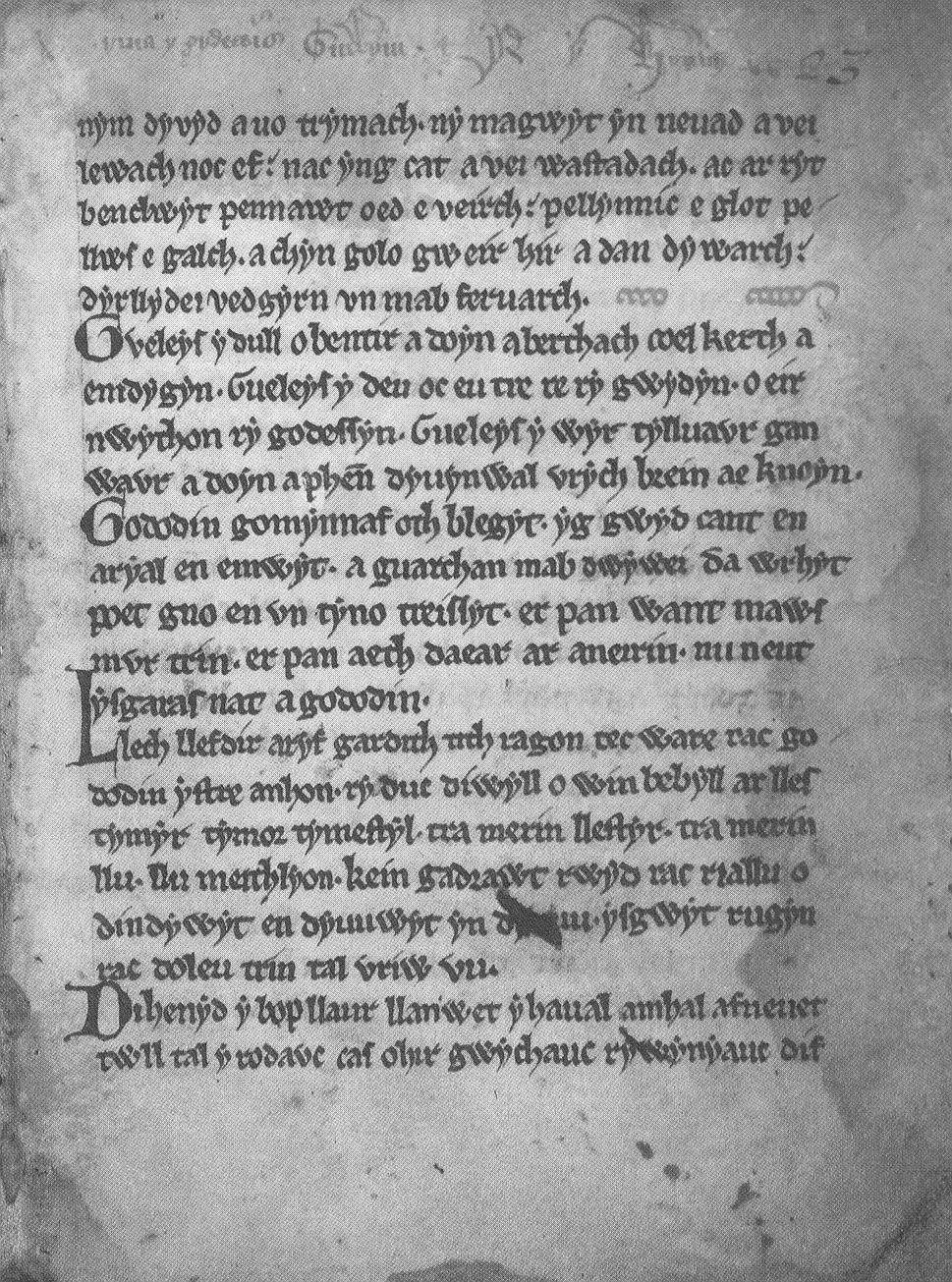

Celtic languages were spoken by many British people at that time. Among the most important written works that have survived are ''

Y Gododdin'' and the

Mabinogion

The ''Mabinogion'' () are the earliest Welsh prose stories, and belong to the Matter of Britain. The stories were compiled in Middle Welsh in the 12th–13th centuries from earlier oral traditions. There are two main source manuscripts, creat ...

. From the 8th to the 15th centuries,

Viking

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

s and

Norse settlers and their descendants

colonised parts of what is now modern Scotland. Some

Old Norse poetry survives relating to this period, including the ''

Orkneyinga saga'' an historical narrative of the history of the

Orkney Islands, from their capture by the Norwegian king in the 9th century until about 1200.

Old English literature: c. 658–1100

Old English literature

Old English literature, or Anglo-Saxon literature, encompasses the surviving literature written in

Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers in the mid-5th ...

in

Anglo-Saxon England

Anglo-Saxon England or Early Medieval England, existing from the 5th to the 11th centuries from the end of Roman Britain until the Norman conquest in 1066, consisted of various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms until 927, when it was united as the Kingdom of ...

, from the settlement of the

Saxons

The Saxons ( la, Saxones, german: Sachsen, ang, Seaxan, osx, Sahson, nds, Sassen, nl, Saksen) were a group of Germanic

*

*

*

*

peoples whose name was given in the early Middle Ages to a large country (Old Saxony, la, Saxonia) near the Nor ...

and other Germanic tribes in England (

Jutes and the

Angles) around 450, until "soon after the Norman Conquest" in 1066; that is, c. 1100–50.

[''The Oxford Companion to English Literature'', ed. Margaret Drabble. (Oxford: Oxford University Press,1996)] These works include genres such as

epic poetry

An epic poem, or simply an epic, is a lengthy narrative poem typically about the extraordinary deeds of extraordinary characters who, in dealings with gods or other superhuman forces, gave shape to the mortal universe for their descendants.

...

,

hagiography,

sermon

A sermon is a religious discourse or oration by a preacher, usually a member of clergy. Sermons address a scriptural, theological, or moral topic, usually expounding on a type of belief, law, or behavior within both past and present contexts. ...

s,

Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus ...

translations, legal works,

chronicle

A chronicle ( la, chronica, from Greek ''chroniká'', from , ''chrónos'' – "time") is a historical account of events arranged in chronological order, as in a timeline. Typically, equal weight is given for historically important events and ...

s, riddles, and others.

[ Angus Cameron (1983). "Anglo-Saxon literature" in '']Dictionary of the Middle Ages

The ''Dictionary of the Middle Ages'' is a 13-volume encyclopedia of the Middle Ages published by the American Council of Learned Societies between 1982 and 1989. It was first conceived and started in 1975 with American medieval historian Jos ...

'', v. 1, pp. 274–88. In all there are about 400 surviving

manuscript

A manuscript (abbreviated MS for singular and MSS for plural) was, traditionally, any document written by hand – or, once practical typewriters became available, typewritten – as opposed to mechanically printed or reproduced i ...

s from the period.

Oral tradition

Oral tradition, or oral lore, is a form of human communication wherein knowledge, art, ideas and Culture, cultural material is received, preserved, and transmitted orally from one generation to another.Jan Vansina, Vansina, Jan: ''Oral Traditio ...

was very strong in early

English culture

The culture of England is defined by the cultural norms of England and the English people. Owing to England's influential position within the United Kingdom it can sometimes be difficult to differentiate English culture from the culture of the ...

and most literary works were written to be performed.

Epic poems

An epic poem, or simply an epic, is a lengthy narrative poem typically about the extraordinary deeds of extraordinary characters who, in dealings with gods or other superhuman forces, gave shape to the mortal universe for their descendants.

...

were thus very popular, and some, including ''

Beowulf

''Beowulf'' (; ang, Bēowulf ) is an Old English epic poem in the tradition of Germanic heroic legend consisting of 3,182 alliterative lines. It is one of the most important and most often translated works of Old English literature. ...

'', have survived to the present day. ''Beowulf'' is the most famous work in Old English and has achieved

national epic

A national epic is an epic poem or a literary work of epic scope which seeks or is believed to capture and express the essence or spirit of a particular nation—not necessarily a nation state, but at least an ethnic or linguistic group with a ...

status in England, despite being set in Scandinavia.

Nearly all Anglo-Saxon authors are anonymous: twelve are known by name from medieval sources, but only four of those are known by their vernacular works with any certainty:

Cædmon

Cædmon (; ''fl. c.'' 657 – 684) is the earliest English poet whose name is known. A Northumbrian cowherd who cared for the animals at the double monastery of Streonæshalch (now known as Whitby Abbey) during the abbacy of St. Hilda, he w ...

,

Bede

Bede ( ; ang, Bǣda , ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, The Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable ( la, Beda Venerabilis), was an English monk at the monastery of St Peter and its companion monastery of St Paul in the Kingdom ...

,

Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great (alt. Ælfred 848/849 – 26 October 899) was King of the West Saxons from 871 to 886, and King of the Anglo-Saxons from 886 until his death in 899. He was the youngest son of King Æthelwulf and his first wife Osburh, who bo ...

, and

Cynewulf. Cædmon is the earliest English poet whose name is known. Cædmon's only known surviving work is ''Cædmon's Hymn'', which probably dates from the late 7th century.

Chronicles contained a range of historical and literary accounts, and a notable example is the ''

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

The ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' is a collection of annals in Old English, chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The original manuscript of the ''Chronicle'' was created late in the 9th century, probably in Wessex, during the reign of A ...

''. The poem ''

Battle of Maldon

The Battle of Maldon took place on 11 August 991 AD near Maldon beside the River Blackwater in Essex, England, during the reign of Æthelred the Unready. Earl Byrhtnoth and his thegns led the English against a Viking invasion. The battl ...

'' also deals with history. This is the name given to a work, of uncertain date, celebrating the real

Battle of Maldon

The Battle of Maldon took place on 11 August 991 AD near Maldon beside the River Blackwater in Essex, England, during the reign of Æthelred the Unready. Earl Byrhtnoth and his thegns led the English against a Viking invasion. The battl ...

of 991, at which the Anglo-Saxons failed to prevent a

Viking

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

invasion.

[

Classical antiquity was not forgotten in Anglo-Saxon England, and several Old English poems are adaptations of ]late classical

Late antiquity is the time of transition from classical antiquity to the Middle Ages, generally spanning the 3rd–7th century in Europe and adjacent areas bordering the Mediterranean Basin. The popularization of this periodization in Englis ...

philosophical texts. The longest is King Alfred

Alfred the Great (alt. Ælfred 848/849 – 26 October 899) was King of the West Saxons from 871 to 886, and King of the Anglo-Saxons from 886 until his death in 899. He was the youngest son of King Æthelwulf and his first wife Osburh, who ...

's (849–99) translation of Boethius

Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, commonly known as Boethius (; Latin: ''Boetius''; 480 – 524 AD), was a Roman senator, consul, ''magister officiorum'', historian, and philosopher of the Early Middle Ages. He was a central figure in the t ...

' '' Consolation of Philosophy''.

Late medieval literature: 1066–1500

The linguistic diversity of the islands in the medieval period contributed to a rich variety of artistic production, and made British literature distinctive and innovative.

The linguistic diversity of the islands in the medieval period contributed to a rich variety of artistic production, and made British literature distinctive and innovative.[''Language and Literature'', Ian Short, in ''A Companion to the Anglo-Norman World'', edited Christopher Harper-Bill and Elisabeth van Houts, Woodbridge 2003, ]

Some works were still written in Latin; these include Gerald of Wales

Gerald of Wales ( la, Giraldus Cambrensis; cy, Gerallt Gymro; french: Gerald de Barri; ) was a Cambro-Norman priest and historian. As a royal clerk to the king and two archbishops, he travelled widely and wrote extensively. He studied and taugh ...

's late-12th-century book on his beloved Wales, '' Itinerarium Cambriae''. After the Norman Conquest

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Norman, Breton, Flemish, and French troops, all led by the Duke of Normandy, later styled William the Conq ...

of 1066, Anglo-Norman literature Anglo-Norman may refer to:

*Anglo-Normans, the medieval ruling class in England following the Norman conquest of 1066

*Anglo-Norman language

** Anglo-Norman literature

*Anglo-Norman England, or Norman England, the period in English history from 106 ...

developed, introducing literary trends from Continental Europe

Continental Europe or mainland Europe is the contiguous continent of Europe, excluding its surrounding islands. It can also be referred to ambiguously as the European continent, – which can conversely mean the whole of Europe – and, by ...

, such as the ''chanson de geste

The ''chanson de geste'' (, from Latin 'deeds, actions accomplished') is a medieval narrative, a type of epic poem that appears at the dawn of French literature. The earliest known poems of this genre date from the late 11th and early 12th c ...

''. However, the indigenous development of Anglo-Norman literature was precocious in comparison to continental Oïl literature.Geoffrey of Monmouth

Geoffrey of Monmouth ( la, Galfridus Monemutensis, Galfridus Arturus, cy, Gruffudd ap Arthur, Sieffre o Fynwy; 1095 – 1155) was a British cleric from Monmouth, Wales and one of the major figures in the development of British historiography ...

( – ) was one of the major figures in the development of British history and of the popularity of the tales of King Arthur

King Arthur ( cy, Brenin Arthur, kw, Arthur Gernow, br, Roue Arzhur) is a legendary king of Britain, and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

In the earliest traditions, Arthur appears as ...

. He is best known for his chronicle ''Historia Regum Britanniae

''Historia regum Britanniae'' (''The History of the Kings of Britain''), originally called ''De gestis Britonum'' (''On the Deeds of the Britons''), is a pseudohistorical account of British history, written around 1136 by Geoffrey of Monmouth. ...

'' (History of the Kings of Britain) of 1136, which spread Celtic motifs to a wider audience. Wace ( – after 1174), who wrote in Norman-French, is the earliest known poet from Jersey

Jersey ( , ; nrf, Jèrri, label= Jèrriais ), officially the Bailiwick of Jersey (french: Bailliage de Jersey, links=no; Jèrriais: ), is an island country and self-governing Crown Dependency near the coast of north-west France. It is the ...

; he also developed the Arthurian legend

The Matter of Britain is the body of medieval literature and legendary material associated with Great Britain and Brittany and the legendary kings and heroes associated with it, particularly King Arthur. It was one of the three great Wester ...

.) At the end of the 12th century, Layamon

Layamon or Laghamon (, ; ) – spelled Laȝamon or Laȝamonn in his time, occasionally written Lawman – was an English poet of the late 12th/early 13th century and author of the ''Brut'', a notable work that was the first to present the legend ...

in '' Brut'' adapted Wace to make the first English-language work to use the legends of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table

The Knights of the Round Table ( cy, Marchogion y Ford Gron, kw, Marghekyon an Moos Krenn, br, Marc'hegien an Daol Grenn) are the knights of the fellowship of King Arthur in the literary cycle of the Matter of Britain. First appearing in lit ...

. It was also the first historiography

Historiography is the study of the methods of historians in developing history as an academic discipline, and by extension is any body of historical work on a particular subject. The historiography of a specific topic covers how historians h ...

written in English since the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

The ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' is a collection of annals in Old English, chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The original manuscript of the ''Chronicle'' was created late in the 9th century, probably in Wessex, during the reign of A ...

.

Middle English

Interest in King Arthur continued in the 15th century with Sir Thomas Malory

Sir Thomas Malory was an English writer, the author of ''Le Morte d'Arthur'', the classic English-language chronicle of the Arthurian legend, compiled and in most cases translated from French sources. The most popular version of ''Le Morte d'Ar ...

's ''Le Morte d'Arthur

' (originally written as '; inaccurate Middle French for "The Death of Arthur") is a 15th-century Middle English prose reworking by Sir Thomas Malory of tales about the legendary King Arthur, Guinevere, Lancelot, Merlin and the Knights of the ...

'' (1485), a popular and influential compilation of some French and English Arthurian romances. It was among the earliest books printed in England by Caxton.

In the later medieval period a new form of English now known as Middle English

Middle English (abbreviated to ME) is a form of the English language that was spoken after the Norman conquest of 1066, until the late 15th century. The English language underwent distinct variations and developments following the Old Englis ...

evolved. This is the earliest form which is comprehensible to modern readers and listeners, albeit not easily. Middle English Bible translations

Middle English Bible translations (1066-1500) covers the age of Middle English, beginning with the Norman conquest and ending about 1500. Aside from Wycliffe's Bible, this was not a fertile time for Bible translation. English literature was limit ...

, notably Wycliffe's Bible

Wycliffe's Bible is the name now given to a group of Bible translations into Middle English that were made under the direction of English theologian John Wycliffe. They appeared over a period from approximately 1382 to 1395. These Bible translat ...

, helped to establish English as a literary language. Wycliffe's Bible is the name now given to a group of Bible translations

The Bible has been translated into many languages from the biblical languages of Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek. all of the Bible has been translated into 724 languages, the New Testament has been translated into an additional 1,617 languages, ...

into Middle English that were made under the direction of, or at the instigation of, John Wycliffe

John Wycliffe (; also spelled Wyclif, Wickliffe, and other variants; 1328 – 31 December 1384) was an English scholastic philosopher, theologian, biblical translator, reformer, Catholic priest, and a seminary professor at the University of ...

. They appeared over a period from about 1382 to 1395.

''Piers Plowman

''Piers Plowman'' (written 1370–86; possibly ) or ''Visio Willelmi de Petro Ploughman'' (''William's Vision of Piers Plowman'') is a Middle English allegorical narrative poem by William Langland. It is written in un- rhymed, alliterati ...

'' or ''Visio Willelmi de Petro Plowman'' (''William's Vision of Piers Plowman'') (written c. 1360–1387) is a Middle English allegorical

As a literary device or artistic form, an allegory is a narrative or visual representation in which a character, place, or event can be interpreted to represent a hidden meaning with moral or political significance. Authors have used allegory t ...

narrative poem

Narrative poetry is a form of poetry that tells a story, often using the voices of both a narrator and characters; the entire story is usually written in metered verse. Narrative poems do not need rhyme. The poems that make up this genre may be ...

by William Langland

William Langland (; la, Willielmus de Langland; 1332 – c. 1386) is the presumed author of a work of Middle English alliterative verse generally known as ''Piers Plowman'', an allegory with a complex variety of religious themes. The poem tr ...

. It is written in unrhymed alliterative verse

In prosody, alliterative verse is a form of verse that uses alliteration as the principal ornamental device to help indicate the underlying metrical structure, as opposed to other devices such as rhyme. The most commonly studied traditions of ...

divided into sections called "passūs" (Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

for "steps"). ''Piers'' is considered by many critics to be one of the early great works of English literature along with Chaucer's ''Canterbury Tales

''The Canterbury Tales'' ( enm, Tales of Caunterbury) is a collection of twenty-four stories that runs to over 17,000 lines written in Middle English by Geoffrey Chaucer between 1387 and 1400. It is widely regarded as Chaucer's '' magnum opu ...

'' and '' Sir Gawain and the Green Knight'' during the Middle Ages.

''Sir Gawain and the Green Knight'' is a late-14th-century Middle English alliterative romance. It is one of the better-known Arthurian stories, of an established type known as the "beheading game". Developing from Welsh, Irish and English tradition ''Sir Gawain'' highlights the importance of honour and chivalry. "Preserved in the same manuscript with Sir Gawayne were three other poems, now generally accepted as the work of its author, including the intricate elegiac poem, ''Pearl

A pearl is a hard, glistening object produced within the soft tissue (specifically the mantle) of a living shelled mollusk or another animal, such as fossil conulariids. Just like the shell of a mollusk, a pearl is composed of calcium carb ...

''."

Geoffrey Chaucer ( – 1400), known as the Father of English literature, is widely considered the greatest English poet of the Middle Ages and was the first poet to have been buried in Poet's Corner in

Geoffrey Chaucer ( – 1400), known as the Father of English literature, is widely considered the greatest English poet of the Middle Ages and was the first poet to have been buried in Poet's Corner in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

. Chaucer is best known today for ''The Canterbury Tales

''The Canterbury Tales'' ( enm, Tales of Caunterbury) is a collection of twenty-four stories that runs to over 17,000 lines written in Middle English by Geoffrey Chaucer between 1387 and 1400. It is widely regarded as Chaucer's '' magnum opus ...

'', a collection of stories written in Middle English (mostly written in verse although some are in prose), that are presented as part of a story-telling contest by a group of pilgrims as they travel together on a journey from Southwark

Southwark ( ) is a district of Central London situated on the south bank of the River Thames, forming the north-western part of the wider modern London Borough of Southwark. The district, which is the oldest part of South London, developed ...

to the shrine of Saint Thomas Becket

Thomas Becket (), also known as Saint Thomas of Canterbury, Thomas of London and later Thomas à Becket (21 December 1119 or 1120 – 29 December 1170), was an English nobleman who served as Lord Chancellor from 1155 to 1162, and the ...

at Canterbury Cathedral

Canterbury Cathedral in Canterbury, Kent, is one of the oldest and most famous Christian structures in England. It forms part of a World Heritage Site. It is the cathedral of the Archbishop of Canterbury, currently Justin Welby, leader of the ...

. Chaucer is a crucial figure in developing the legitimacy of the vernacular

A vernacular or vernacular language is in contrast with a "standard language". It refers to the language or dialect that is spoken by people that are inhabiting a particular country or region. The vernacular is typically the native language, n ...

, Middle English, at a time when the dominant literary languages in England were French and Latin.

The multilingual nature of the audience for literature in the 14th century can be illustrated by the example of John Gower

John Gower (; c. 1330 – October 1408) was an English poet, a contemporary of William Langland and the Pearl Poet, and a personal friend of Geoffrey Chaucer. He is remembered primarily for three major works, the '' Mirour de l'Omme'', '' Vo ...

( – October 1408). A contemporary of Langland and a personal friend of Chaucer, Gower is remembered primarily for three major works, the ''Mirroir de l'Omme'', ''Vox Clamantis

''Vox Clamantis'' ("the voice of one crying out") is a Latin poem of 10,265 lines in elegiac couplets by John Gower (1330 – October 1408) . The first of the seven books is a dream vision giving a vivid account of the Peasants' Rebellion of ...

'', and ''Confessio Amantis

''Confessio Amantis'' ("The Lover's Confession") is a 33,000-line Middle English poem by John Gower, which uses the confession made by an ageing lover to the chaplain of Venus as a frame story for a collection of shorter narrative poems. Acco ...

'', three long poems written in Anglo-Norman Anglo-Norman may refer to:

*Anglo-Normans, the medieval ruling class in England following the Norman conquest of 1066

*Anglo-Norman language

**Anglo-Norman literature

*Anglo-Norman England, or Norman England, the period in English history from 1066 ...

, Latin, and Middle English respectively, which are united by common moral and political themes.

Women writers were also active, such as Marie de France in the 12th century and Julian of Norwich

Julian of Norwich (1343 – after 1416), also known as Juliana of Norwich, Dame Julian or Mother Julian, was an English mystic and anchoress of the Middle Ages. Her writings, now known as '' Revelations of Divine Love'', are the earlies ...

in the early 14th century. Julian's '' Revelations of Divine Love'' (around 1393) is believed to be the first published book written by a woman in the English language.[

] Margery Kempe

'

Margery Kempe ( – after 1438) was an English Christian mystic, known for writing through dictation ''The Book of Margery Kempe'', a work considered by some to be the first autobiography in the English language. Her book chronicles Kempe's d ...

( – after 1438) is known for writing ''The Book of Margery Kempe

''The Book of Margery Kempe'' is a medieval text attributed to Margery Kempe, an English Christian mystic and pilgrim who lived at the turn of the fifteenth century. It details Kempe's life, her travels, her alleged experiences of divine revelati ...

'', a work considered by some to be the first autobiography in the English language.

Major Scottish writers from the 15th century include Henrysoun, Dunbar

Dunbar () is a town on the North Sea coast in East Lothian in the south-east of Scotland, approximately east of Edinburgh and from the English border north of Berwick-upon-Tweed.

Dunbar is a former royal burgh, and gave its name to an ...

, Douglas

Douglas may refer to:

People

* Douglas (given name)

* Douglas (surname)

Animals

*Douglas (parrot), macaw that starred as the parrot ''Rosalinda'' in Pippi Longstocking

* Douglas the camel, a camel in the Confederate Army in the American Civil ...

and Lyndsay

Lindsay or Lindsey () is an English surname and given name. The given name comes from the Scottish surname and clan name, which comes from the toponym Lindsey, which in turn comes from the Old English toponym ''Lindesege'' ("Island of Lind") fo ...

. The works of Chaucer had an influence on Scottish writers.

Medieval drama

In the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

, drama in the vernacular languages of Europe may have emerged from religious enactments of the liturgy

Liturgy is the customary public ritual of worship performed by a religious group. ''Liturgy'' can also be used to refer specifically to public worship by Christians. As a religious phenomenon, liturgy represents a communal response to and partic ...

. Mystery play

Mystery plays and miracle plays (they are distinguished as two different forms although the terms are often used interchangeably) are among the earliest formally developed plays in medieval Europe. Medieval mystery plays focused on the represe ...

s were presented on the porches of the cathedrals or by strolling players on feast days

The calendar of saints is the traditional Christian method of organizing a liturgical year by associating each day with one or more saints and referring to the day as the feast day or feast of said saint. The word "feast" in this context does ...

. Miracle

A miracle is an event that is inexplicable by natural or scientific lawsOne dictionary define"Miracle"as: "A surprising and welcome event that is not explicable by natural or scientific laws and is therefore considered to be the work of a divi ...

and mystery plays, along with moralities and interludes, later evolved into more elaborate forms of drama, such as was seen on the Elizabethan stages. Another form of medieval theatre was the mummers' plays, a form of early street theatre associated with the Morris dance

Morris dancing is a form of English folk dance. It is based on rhythmic stepping and the execution of choreographed figures by a group of dancers, usually wearing bell pads on their shins. Implements such as sticks, swords and handkerchiefs may ...

, concentrating on themes such as Saint George

Saint George ( Greek: Γεώργιος (Geórgios), Latin: Georgius, Arabic: القديس جرجس; died 23 April 303), also George of Lydda, was a Christian who is venerated as a saint in Christianity. According to tradition he was a soldie ...

and the Dragon

A dragon is a reptilian legendary creature that appears in the folklore of many cultures worldwide. Beliefs about dragons vary considerably through regions, but dragons in western cultures since the High Middle Ages have often been depicted a ...

and Robin Hood

Robin Hood is a legendary heroic outlaw originally depicted in English folklore and subsequently featured in literature and film. According to legend, he was a highly skilled archer and swordsman. In some versions of the legend, he is dep ...

. These were folk tales re-telling old stories, and the actors travelled from town to town performing these for their audiences in return for money and hospitality.

Mystery plays and miracle plays are among the earliest formally developed plays in medieval Europe. Mystery plays focused on the representation of Bible stories in churches as tableaux with accompanying antiphon

An antiphon ( Greek ἀντίφωνον, ἀντί "opposite" and φωνή "voice") is a short chant in Christian ritual, sung as a refrain. The texts of antiphons are the Psalms. Their form was favored by St Ambrose and they feature prominentl ...

al song. They developed from the 10th to the 16th century, reaching the height of their popularity in the 15th century before being rendered obsolete by the rise of professional theatre.

There are four complete or nearly complete extant English biblical collections of plays from the late medieval period. The most complete is the '' York cycle'' of forty-eight pageants. They were performed in the city of

There are four complete or nearly complete extant English biblical collections of plays from the late medieval period. The most complete is the '' York cycle'' of forty-eight pageants. They were performed in the city of York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

, from the middle of the 14th century until 1569. Besides the Middle English drama, there are three surviving plays in Cornish known as the Ordinalia.

Having grown out of the religiously based mystery plays, the morality play is a genre

Genre () is any form or type of communication in any mode (written, spoken, digital, artistic, etc.) with socially-agreed-upon conventions developed over time. In popular usage, it normally describes a category of literature, music, or other f ...

of medieval and early Tudor theatrical entertainment, which represented a shift towards a more secular base for European theatre. Morality plays are a type of allegory

As a literary device or artistic form, an allegory is a narrative or visual representation in which a character, place, or event can be interpreted to represent a hidden meaning with moral or political significance. Authors have used allegory t ...

in which the protagonist

A protagonist () is the main character of a story. The protagonist makes key decisions that affect the plot, primarily influencing the story and propelling it forward, and is often the character who faces the most significant obstacles. If a st ...

is met by personification

Personification occurs when a thing or abstraction is represented as a person, in literature or art, as a type of anthropomorphic metaphor. The type of personification discussed here excludes passing literary effects such as "Shadows hold their ...

s of various moral

A moral (from Latin ''morālis'') is a message that is conveyed or a lesson to be learned from a story or event. The moral may be left to the hearer, reader, or viewer to determine for themselves, or may be explicitly encapsulated in a maxim. ...

attributes who try to prompt him to choose a godly life over one of evil. The plays were most popular in Europe during the 15th and 16th centuries.

''The Somonyng of Everyman'' (''The Summoning of Everyman'') ( – 1519), usually referred to simply as ''Everyman

The everyman is a stock character of fiction. An ordinary and humble character, the everyman is generally a protagonist whose benign conduct fosters the audience's identification with them.

Origin

The term ''everyman'' was used as early as ...

'', is a late 15th-century English morality play. Like John Bunyan

John Bunyan (; baptised 30 November 162831 August 1688) was an English writer and Puritan preacher best remembered as the author of the Christian allegory ''The Pilgrim's Progress,'' which also became an influential literary model. In addition ...

's allegory ''Pilgrim's Progress

''The Pilgrim's Progress from This World, to That Which Is to Come'' is a 1678 Christian allegory written by John Bunyan. It is regarded as one of the most significant works of theological fiction in English literature and a progenitor of ...

'' (1678), ''Everyman'' examines the question of Christian salvation through the use of allegorical characters.

The Renaissance: 1500 –1660

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

style and ideas were slow to penetrate England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

and Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, and the Elizabethan era

The Elizabethan era is the epoch in the Tudor period of the history of England during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603). Historians often depict it as the golden age in English history. The symbol of Britannia (a female personific ...

(1558–1603) is usually regarded as the height of the English Renaissance. However, many scholars see its beginnings in the early 1500s during the reign of Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

(1491 – 1547).

Italian literary influences arrived in Britain: the sonnet

A sonnet is a poetic form that originated in the poetry composed at the Court of the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II in the Sicilian city of Palermo. The 13th-century poet and notary Giacomo da Lentini is credited with the sonnet's inventio ...

form was introduced into English by Thomas Wyatt in the early 16th century, and was developed by Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey

Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey (1516/1517 – 19 January 1547), KG, was an English nobleman, politician and poet. He was one of the founders of English Renaissance poetry and was the last known person executed at the instance of King Henry VII ...

, (1516/1517 – 1547), who also introduced blank verse

Blank verse is poetry written with regular metrical but unrhymed lines, almost always in iambic pentameter. It has been described as "probably the most common and influential form that English poetry has taken since the 16th century", and Pa ...

into England, with his translation of Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: th ...

's ''Aeneid

The ''Aeneid'' ( ; la, Aenē̆is or ) is a Latin epic poem, written by Virgil between 29 and 19 BC, that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Trojan who fled the fall of Troy and travelled to Italy, where he became the ancestor of ...

'' in .

The spread of printing affected the transmission of literature across Britain and Ireland. The first book printed in English, William Caxton

William Caxton ( – ) was an English merchant, diplomat and writer. He is thought to be the first person to introduce a printing press into England, in 1476, and as a printer to be the first English retailer of printed books.

His parentage a ...

's own translation of '' Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye'', was printed abroad in 1473, to be followed by the establishment of the first printing press in England in 1474.

Latin continued in use as a language of learning long after the

Latin continued in use as a language of learning long after the Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

had established the vernaculars as liturgical languages for the elites.

''Utopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imaginary community or society that possesses highly desirable or nearly perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book '' Utopia'', describing a fictional island soc ...

'' is a work of fiction and political philosophy

Political philosophy or political theory is the philosophical study of government, addressing questions about the nature, scope, and legitimacy of public agents and institutions and the relationships between them. Its topics include politics, ...

by Thomas More

Sir Thomas More (7 February 1478 – 6 July 1535), venerated in the Catholic Church as Saint Thomas More, was an English lawyer, judge, social philosopher, author, statesman, and noted Renaissance humanist. He also served Henry VIII as Lord ...

(1478–1535) published in 1516. The book, written in Latin, is a frame narrative

A frame is often a structural system that supports other components of a physical construction and/or steel frame that limits the construction's extent.

Frame and FRAME may also refer to:

Physical objects

In building construction

*Framing (co ...

primarily depicting a fictional island society and its religious, social

Social organisms, including human(s), live collectively in interacting populations. This interaction is considered social whether they are aware of it or not, and whether the exchange is voluntary or not.

Etymology

The word "social" derives from ...

and political customs.

Elizabethan era: 1558–1603

Poetry

In the later 16th century, English poetry used elaborate language and extensive allusions to classical myths. Sir Edmund Spenser (1555–99) was the author of ''The Faerie Queene

''The Faerie Queene'' is an English epic poem by Edmund Spenser. Books IIII were first published in 1590, then republished in 1596 together with books IVVI. ''The Faerie Queene'' is notable for its form: at over 36,000 lines and over 4,000 sta ...

'', an epic poem and fantastical allegory celebrating the Tudor dynasty

The House of Tudor was a royal house of largely Welsh and English origin that held the English throne from 1485 to 1603. They descended from the Tudors of Penmynydd and Catherine of France. Tudor monarchs ruled the Kingdom of England and it ...

and Elizabeth I. The works of Sir Philip Sidney (1554–1586), a poet, courtier and soldier, include '' Astrophel and Stella'', ''The Defence of Poetry

''An Apology for Poetry'' (or ''The Defence of Poesy'') is a work of literary criticism by Elizabethan poet Philip Sidney. It was written in approximately 1580 and first published in 1595, after his death.

It is generally believed that he was ...

'', and '' Arcadia''. Poems intended to be set to music as songs, such as those by Thomas Campion

Thomas Campion (sometimes spelled Campian; 12 February 1567 – 1 March 1620) was an English composer, poet, and physician. He was born in London, educated at Cambridge, studied law in Gray's inn. He wrote over a hundred lute songs, masques ...

, became popular as printed literature was disseminated more widely in households (see English Madrigal School

The English Madrigal School was the brief but intense flowering of the musical madrigal in England, mostly from 1588 to 1627, along with the composers who produced them. The English madrigals were a cappella, predominantly light in style, and gener ...

).

Drama

During the reign of Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

(1558–1603) and then James I (1603–25), a London-centred culture that was both courtly and popular, produced great poetry and drama. The English playwrights were intrigued by Italian model: a conspicuous community of Italian actors had settled in London. The linguist and lexicographer John Florio

Giovanni Florio (1552–1625), known as John Florio, was an English linguist, poet, writer, translator, lexicographer, and royal language tutor at the Court of James I. He is recognised as the most important Renaissance humanist in England. ...

(1553–1625), whose father was Italian, was a royal language tutor at the Court of James I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

*James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

*James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

*James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334–13 ...

, and a possible friend and influence on William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

, had brought much of the Italian language

Italian (''italiano'' or ) is a Romance language of the Indo-European language family that evolved from the Vulgar Latin of the Roman Empire. Together with Sardinian, Italian is the least divergent language from Latin. Spoken by about 8 ...

and culture to England. He was also the translator of Montaigne

Michel Eyquem, Sieur de Montaigne ( ; ; 28 February 1533 – 13 September 1592), also known as the Lord of Montaigne, was one of the most significant philosophers of the French Renaissance. He is known for popularizing the essay as a lit ...

into English. The earliest Elizabethan plays include ''Gorboduc

Gorboduc ('' Welsh:'' Gorwy or Goronwy) was a legendary king of the Britons as recounted by Geoffrey of Monmouth. He was married to Judon. When he became old, his sons, Ferrex and Porrex, feuded over who would take over the kingdom. Porrex tried ...

'' (1561), by Sackville and Norton, and Thomas Kyd

Thomas Kyd (baptised 6 November 1558; buried 15 August 1594) was an English playwright, the author of '' The Spanish Tragedy'', and one of the most important figures in the development of Elizabethan drama.

Although well known in his own time, ...

's (1558–94) revenge tragedy

Revenge tragedy (sometimes referred to as revenge drama, revenge play, or tragedy of blood) is a theoretical genre in which the principal theme is revenge and revenge's fatal consequences. Formally established by American educator Ashley H. Thor ...

''The Spanish Tragedy

''The Spanish Tragedy, or Hieronimo is Mad Again'' is an Elizabethan tragedy written by Thomas Kyd between 1582 and 1592. Highly popular and influential in its time, ''The Spanish Tragedy'' established a new genre in English theatre, the rev ...

'' (1592). Highly popular and influential in its time, ''The Spanish Tragedy'' established a new genre

Genre () is any form or type of communication in any mode (written, spoken, digital, artistic, etc.) with socially-agreed-upon conventions developed over time. In popular usage, it normally describes a category of literature, music, or other f ...

in English literature theatre, the revenge play or revenge tragedy. Jane Lumley

Jane Lumley, Baroness Lumley ( Lady Jane Fitzalan; 1537 – 27 July 1578), sometimes called Joanna, was an English noblewoman. She was the first person to translate Euripides into English.

Life and family

Jane is the eldest child of three sibli ...

(1537–1578) was the first person to translate Euripides

Euripides (; grc, Εὐριπίδης, Eurīpídēs, ; ) was a tragedian of classical Athens. Along with Aeschylus and Sophocles, he is one of the three ancient Greek tragedians for whom any plays have survived in full. Some ancient scholars ...

into English. Her translation of ''Iphigeneia at Aulis

''Iphigenia in Aulis'' or ''Iphigenia at Aulis'' ( grc, Ἰφιγένεια ἐν Αὐλίδι, Īphigéneia en Aulídi; variously translated, including the Latin ''Iphigenia in Aulide'') is the last of the extant works by the playwright Euripide ...

'' is the first known dramatic work by a woman in English.

William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

(1564–1616) stands out in this period as a poet

A poet is a person who studies and creates poetry. Poets may describe themselves as such or be described as such by others. A poet may simply be the creator ( thinker, songwriter, writer, or author) who creates (composes) poems (oral or w ...

and playwright

A playwright or dramatist is a person who writes plays.

Etymology

The word "play" is from Middle English pleye, from Old English plæġ, pleġa, plæġa ("play, exercise; sport, game; drama, applause"). The word "wright" is an archaic English ...

as yet unsurpassed. Shakespeare wrote plays in a variety of genres, including histories

Histories or, in Latin, Historiae may refer to:

* the plural of history

* ''Histories'' (Herodotus), by Herodotus

* ''The Histories'', by Timaeus

* ''The Histories'' (Polybius), by Polybius

* ''Histories'' by Gaius Sallustius Crispus (Sallust), ...

, tragedies

Tragedy (from the grc-gre, τραγῳδία, ''tragōidia'', ''tragōidia'') is a genre of drama based on human suffering and, mainly, the terrible or sorrowful events that befall a main character. Traditionally, the intention of tragedy ...

, comedies

Comedy is a genre of fiction that consists of discourses or works intended to be humorous or amusing by inducing laughter, especially in theatre, film, stand-up comedy, television, radio, books, or any other entertainment medium. The term origin ...

and the late romances, or tragicomedies. Works written in the Elizabethan era include the comedy ''Twelfth Night

''Twelfth Night'', or ''What You Will'' is a romantic comedy by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written around 1601–1602 as a Twelfth Night's entertainment for the close of the Christmas season. The play centres on the twins Vi ...

'', tragedy ''Hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play, with 29,551 words. Set in Denmark, the play depicts ...

'', and history ''Henry IV, Part 1

''Henry IV, Part 1'' (often written as ''1 Henry IV'') is a history play by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written no later than 1597. The play dramatises part of the reign of King Henry IV of England, beginning with the battle at ...

''.

Jacobean period: 1603-1625

Drama

Shakespeare's career continued during the reign of King James I, and in the early 17th century he wrote the so-called " problem plays", like ''Measure for Measure

''Measure for Measure'' is a play by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written in 1603 or 1604 and first performed in 1604, according to available records. It was published in the '' First Folio'' of 1623.

The play's plot features its ...

'', as well as a number of his best known tragedies

Tragedy (from the grc-gre, τραγῳδία, ''tragōidia'', ''tragōidia'') is a genre of drama based on human suffering and, mainly, the terrible or sorrowful events that befall a main character. Traditionally, the intention of tragedy ...

, including ''King Lear

''King Lear'' is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare.

It is based on the mythological Leir of Britain. King Lear, in preparation for his old age, divides his power and land between two of his daughters. He becomes destitute and insane a ...

'' and '' Anthony and Cleopatra''. The plots of Shakespeare's tragedies often hinge on fatal errors or flaws, which overturn order and destroy the hero and those he loves. In his final period, Shakespeare turned to romance or tragicomedy

Tragicomedy is a literary genre that blends aspects of both tragic and comic forms. Most often seen in dramatic literature, the term can describe either a tragic play which contains enough comic elements to lighten the overall mood or a seriou ...

and completed four major plays, including '' The Tempest''. Less bleak than the tragedies, these four plays are graver in tone than the comedies of the 1590s, but they end with reconciliation and the forgiveness of potentially tragic errors.

Other important figures in Elizabethan and Jacobean theatre include Christopher Marlowe

Christopher Marlowe, also known as Kit Marlowe (; baptised 26 February 156430 May 1593), was an English playwright, poet and translator of the Elizabethan era. Marlowe is among the most famous of the Elizabethan playwrights. Based upon t ...

(1564–1593), Thomas Dekker ( – 1632), John Fletcher (1579–1625) and Francis Beaumont

Francis Beaumont ( ; 1584 – 6 March 1616) was a dramatist in the English Renaissance theatre, most famous for his collaborations with John Fletcher.

Beaumont's life

Beaumont was the son of Sir Francis Beaumont of Grace Dieu, near Thr ...

(1584–1616). Marlowe's subject matter is different from Shakespeare's as it focuses more on the moral drama of the renaissance man. His play Doctor Faustus (), is about a scientist and magician who sells his soul to the Devil. Beaumont and Fletcher

Beaumont and Fletcher were the English dramatists Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher, who collaborated in their writing during the reign of James I (1603–25).

They became known as a team early in their association, so much so that their joi ...

are less known, but they may have helped Shakespeare write some of his best dramas, and were popular at the time. Beaumont's comedy, '' The Knight of the Burning Pestle'' (1607), satirises the rising middle class and especially the ''nouveaux riches''.

After Shakespeare's death, the poet and dramatist Ben Jonson

Benjamin "Ben" Jonson (c. 11 June 1572 – c. 16 August 1637) was an English playwright and poet. Jonson's artistry exerted a lasting influence upon English poetry and stage comedy. He popularised the comedy of humours; he is best known for t ...

(1572–1637) was the leading literary figure of the Jacobean era. Jonson's aesthetics hark back to the Middle Ages and his characters embody the theory of humours

Humorism, the humoral theory, or humoralism, was a system of medicine detailing a supposed makeup and workings of the human body, adopted by Ancient Greek and Roman physicians and philosophers.

Humorism began to fall out of favor in the 1850 ...

, based on contemporary medical theory, though the stock types of Latin literature

Latin literature includes the essays, histories, poems, plays, and other writings written in the Latin language. The beginning of formal Latin literature dates to 240 BC, when the first stage play in Latin was performed in Rome. Latin literature ...

were an equal influence. Jonson's major plays include '' Volpone'' (1605 or 1606) and ''Bartholomew Fair

The Bartholomew Fair was one of London's pre-eminent summer charter fairs. A charter for the fair was granted to Rahere by Henry I to fund the Priory of St Bartholomew; and from 1133 to 1855 it took place each year on 24 August within the preci ...

'' (1614).

A popular style of theatre in Jacobean times was the revenge play, which had been popularised earlier by Thomas Kyd

Thomas Kyd (baptised 6 November 1558; buried 15 August 1594) was an English playwright, the author of '' The Spanish Tragedy'', and one of the most important figures in the development of Elizabethan drama.

Although well known in his own time, ...

(1558–94), and then developed by John Webster

John Webster (c. 1580 – c. 1632) was an English Jacobean dramatist best known for his tragedies '' The White Devil'' and '' The Duchess of Malfi'', which are often seen as masterpieces of the early 17th-century English stage. His life and c ...

(1578–1632) in the 17th century. Webster's most famous plays are ''The White Devil

''The White Devil'' (full original title: ''The White Divel; or, The Tragedy of Paulo Giordano Ursini, Duke of Brachiano. With The Life and Death of Vittoria Corombona the famous Venetian Curtizan'') is a tragedy by English playwright John W ...

'' (1612) and '' The Duchess of Malfi'' (1613). Other revenge tragedies include '' The Changeling'' written by Thomas Middleton

Thomas Middleton (baptised 18 April 1580 – July 1627; also spelt ''Midleton'') was an English Jacobean playwright and poet. He, with John Fletcher and Ben Jonson, was among the most successful and prolific of playwrights at work in the Jac ...

and William Rowley

William Rowley (c. 1585 – February 1626) was an English Jacobean dramatist, best known for works written in collaboration with more successful writers. His date of birth is estimated to have been c. 1585; he was buried on 11 February 1626 i ...

.

Poetry

Shakespeare also popularised the English sonnet, which made significant changes to Petrarch

Francesco Petrarca (; 20 July 1304 – 18/19 July 1374), commonly anglicized as Petrarch (), was a scholar and poet of early Renaissance Italy, and one of the earliest humanists.

Petrarch's rediscovery of Cicero's letters is often credited ...

's model. A collection of 154 sonnets

A sonnet is a poetic form that originated in the poetry composed at the Court of the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II in the Sicilian city of Palermo. The 13th-century poet and notary Giacomo da Lentini is credited with the sonnet's inventio ...

, dealing with themes such as the passage of time, love, beauty and mortality, were first published in a 1609 quarto.

Besides Shakespeare the major poets of the early 17th century included the metaphysical poets

Besides Shakespeare the major poets of the early 17th century included the metaphysical poets John Donne

John Donne ( ; 22 January 1572 – 31 March 1631) was an English poet, scholar, soldier and secretary born into a recusant family, who later became a cleric in the Church of England. Under royal patronage, he was made Dean of St Paul's Cathe ...

(1572–1631) and George Herbert (1593–1633). Influenced by continental Baroque

The Baroque (, ; ) is a style of architecture, music, dance, painting, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished in Europe from the early 17th century until the 1750s. In the territories of the Spanish and Portuguese empires including ...

, and taking as his subject matter both Christian mysticism and eroticism, Donne's metaphysical poetry uses unconventional or "unpoetic" figures, such as a compass or a mosquito, to achieve surprise effects.

George Chapman (?1559-?1634) was a successful playwright who is remembered chiefly for his translation in 1616 of Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

's Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; grc, Ἰλιάς, Iliás, ; "a poem about Ilium") is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Ody ...

and Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; grc, Ὀδύσσεια, Odýsseia, ) is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the '' Iliad'', ...

into English verse. This was the first ever complete translation of either poem into the English language and it had a profound influence on English literature.

Prose

Philosopher Sir Francis Bacon (1561–1626) wrote the utopian novel

Utopian and dystopian fiction are genres of speculative fiction that explore social and political structures. Utopian fiction portrays a setting that agrees with the author's ethos, having various attributes of another reality intended to appeal ...

'' New Atlantis'', and coined the phrase "''Knowledge is Power

The phrase "" (or "" or also "") is a Latin aphorism meaning "knowledge is power", commonly attributed to Sir Francis Bacon. The expression "" ('knowledge itself is power') occurs in Bacon's ''Meditationes Sacrae'' (1597). The exact phrase "" ...

''". Francis Godwin's 1638 '' The Man in the Moone'' recounts an imaginary voyage to the moon and is now regarded as the first work of science fiction in English literature.

At the Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

, the translation of liturgy

Liturgy is the customary public ritual of worship performed by a religious group. ''Liturgy'' can also be used to refer specifically to public worship by Christians. As a religious phenomenon, liturgy represents a communal response to and partic ...

and the Bible into vernacular languages provided new literary models. The ''Book of Common Prayer

The ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP) is the name given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The original book, published in 1549 in the reign ...

'' (1549) and the '' Authorised King James Version'' of the Bible have been hugely influential. The King James Bible, one of the biggest translation projects in the history of English up to that time, was started in 1604 and completed in 1611. It continued the tradition of Bible translation into English from the original languages that began with the work of William Tyndale

William Tyndale (; sometimes spelled ''Tynsdale'', ''Tindall'', ''Tindill'', ''Tyndall''; – ) was an English biblical scholar and linguist who became a leading figure in the Protestant Reformation in the years leading up to his execu ...

. (Previous translations into English had relied on the Vulgate

The Vulgate (; also called (Bible in common tongue), ) is a late-4th-century Latin translation of the Bible.

The Vulgate is largely the work of Jerome who, in 382, had been commissioned by Pope Damasus I to revise the Gospels u ...

). It became the standard Bible of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Brit ...

, and some consider it one of the greatest literary works of all time.

Late Renaissance: 1625–1660

The

The metaphysical poets

The term Metaphysical poets was coined by the critic Samuel Johnson to describe a loose group of 17th-century English poets whose work was characterised by the inventive use of conceits, and by a greater emphasis on the spoken rather than lyrica ...

continued writing in this period. Both John Donne and George Herbert died after 1625, but there was a second generation of metaphysical poets: Andrew Marvell

Andrew Marvell (; 31 March 1621 – 16 August 1678) was an English metaphysical poet, satirist and politician who sat in the House of Commons at various times between 1659 and 1678. During the Commonwealth period he was a colleague and friend ...

(1621–1678), Thomas Traherne (1636 or 1637–1674) and Henry Vaughan

Henry Vaughan (17 April 1621 – 23 April 1695) was a Welsh metaphysical poet, author and translator writing in English, and a medical physician. His religious poetry appeared in ''Silex Scintillans'' in 1650, with a second part in 1655.''Oxfo ...

(1622–1695). Their style was witty, with metaphysical conceits — far-fetched or unusual similes

A simile () is a figure of speech that directly ''compares'' two things. Similes differ from other metaphors by highlighting the similarities between two things using comparison words such as "like", "as", "so", or "than", while other metaphors cr ...

or metaphors, such as Marvell's comparison of the soul with a drop of dew; or Donne's description of the effects of absence on lovers to the action of a pair of compasses.

Another important group of poets at this time were the Cavalier poets. They were an important group of writers, who came from the classes that supported King Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms

The Wars of the Three Kingdoms were a series of related conflicts fought between 1639 and 1653 in the kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland, then separate entities united in a personal union under Charles I. They include the 1639 to 1640 Bi ...

(1639–51). (King Charles reigned from 1625 and was executed in 1649). The best known of these poets are Robert Herrick, Richard Lovelace, Thomas Carew, and Sir John Suckling. They "were not a formal group, but all were influenced" by Ben Jonson

Benjamin "Ben" Jonson (c. 11 June 1572 – c. 16 August 1637) was an English playwright and poet. Jonson's artistry exerted a lasting influence upon English poetry and stage comedy. He popularised the comedy of humours; he is best known for t ...

. Most of the Cavalier poets were courtier

A courtier () is a person who attends the royal court of a monarch or other royalty. The earliest historical examples of courtiers were part of the retinues of rulers. Historically the court was the centre of government as well as the official ...

s, with notable exceptions. For example, Robert Herrick was not a courtier, but his style marks him as a Cavalier poet. Cavalier works make use of allegory and classical allusions, and are influenced by Latin authors Horace

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (; 8 December 65 – 27 November 8 BC), known in the English-speaking world as Horace (), was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus (also known as Octavian). The rhetorician Quintilian regarded his ' ...

, Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the esta ...

, and Ovid