British contribution to the Manhattan Project on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Britain contributed to the

Britain contributed to the

The 1938

The 1938

The British and Americans exchanged nuclear information, but did not initially combine their efforts. British officials did not reply to an August 1941 offer by Bush and Conant to create a combined British and American project. In November 1941,

The British and Americans exchanged nuclear information, but did not initially combine their efforts. British officials did not reply to an August 1941 offer by Bush and Conant to create a combined British and American project. In November 1941,

By March 1943 Conant decided that British help would benefit some areas of the project. In particular, the Manhattan Project could benefit enough from assistance from

By March 1943 Conant decided that British help would benefit some areas of the project. In particular, the Manhattan Project could benefit enough from assistance from

The Quebec Agreement allowed Simon and Peierls to meet with representatives of Kellex, who were designing and building the American gaseous diffusion plant, Union Carbide and Carbon, who would operate it, and

The Quebec Agreement allowed Simon and Peierls to meet with representatives of Kellex, who were designing and building the American gaseous diffusion plant, Union Carbide and Carbon, who would operate it, and

When cooperation resumed in September 1943, Groves and Oppenheimer revealed the existence of the Los Alamos Laboratory to Chadwick, Peierls and Oliphant. Oppenheimer wanted all three to proceed to Los Alamos as soon as possible, but it was decided that Oliphant would go to Berkeley to work on the electromagnetic process and Peierls would go to New York to work on the gaseous diffusion process. The task then fell to Chadwick. The original idea, favoured by Groves, was that the British scientists would work as a group under Chadwick, who would farm out work to them. This was soon discarded in favour of having the British Mission fully integrated into the laboratory. They worked in most of its divisions, only being excluded from plutonium chemistry and metallurgy.

First to arrive was Otto Frisch and Ernest Titterton and his wife Peggy, who reached Los Alamos on 13 December 1943. At Los Alamos Frisch continued his work on critical mass studies, for which Titterton developed electronic circuitry for high voltage generators, X-ray generators, timers and firing circuits. Peggy Titterton, a trained physics and metallurgy laboratory assistant, was one of the few women working at Los Alamos in a technical role. Chadwick arrived on 12 January 1944, but only stayed for a few months before returning to Washington, D.C.

When Oppenheimer appointed

When cooperation resumed in September 1943, Groves and Oppenheimer revealed the existence of the Los Alamos Laboratory to Chadwick, Peierls and Oliphant. Oppenheimer wanted all three to proceed to Los Alamos as soon as possible, but it was decided that Oliphant would go to Berkeley to work on the electromagnetic process and Peierls would go to New York to work on the gaseous diffusion process. The task then fell to Chadwick. The original idea, favoured by Groves, was that the British scientists would work as a group under Chadwick, who would farm out work to them. This was soon discarded in favour of having the British Mission fully integrated into the laboratory. They worked in most of its divisions, only being excluded from plutonium chemistry and metallurgy.

First to arrive was Otto Frisch and Ernest Titterton and his wife Peggy, who reached Los Alamos on 13 December 1943. At Los Alamos Frisch continued his work on critical mass studies, for which Titterton developed electronic circuitry for high voltage generators, X-ray generators, timers and firing circuits. Peggy Titterton, a trained physics and metallurgy laboratory assistant, was one of the few women working at Los Alamos in a technical role. Chadwick arrived on 12 January 1944, but only stayed for a few months before returning to Washington, D.C.

When Oppenheimer appointed  William Penney worked on means to assess the effects of a nuclear explosion, and wrote a paper on what height the bombs should be detonated at for maximum effect in attacks on Germany and Japan. He served as a member of the target committee established by Groves to select Japanese cities for atomic bombing, and on

William Penney worked on means to assess the effects of a nuclear explosion, and wrote a paper on what height the bombs should be detonated at for maximum effect in attacks on Germany and Japan. He served as a member of the target committee established by Groves to select Japanese cities for atomic bombing, and on

The Combined Development Trust was proposed by the Combined Policy Committee on 17 February 1944. The declaration of trust was signed by Churchill and Roosevelt on 13 June 1944. The trustees were approved at the Combined Policy Committee meeting on 19 September 1944. The United States trustees were Groves, who was elected chairman, geologist Charles K. Leith, and

The Combined Development Trust was proposed by the Combined Policy Committee on 17 February 1944. The declaration of trust was signed by Churchill and Roosevelt on 13 June 1944. The trustees were approved at the Combined Policy Committee meeting on 19 September 1944. The United States trustees were Groves, who was elected chairman, geologist Charles K. Leith, and

Groves appreciated the early British atomic research and the British scientists' contributions to the Manhattan Project, but stated that the United States would have succeeded without them. He considered British assistance "helpful but not vital", but acknowledged that "without active and continuing British interest, there probably would have been no atomic bomb to drop on Hiroshima." He considered Britain's key contributions to have been encouragement and support at the intergovernmental level, scientific aid, the production of powdered nickel in Wales, and preliminary studies and laboratory work.

Cooperation did not long survive the war. Roosevelt died on 12 April 1945, and the Hyde Park Agreement was not binding on subsequent administrations. In fact, it was physically lost. When Wilson raised the matter in a Combined Policy Committee meeting in June, the American copy could not be found. The British sent Stimson a photocopy on 18 July 1945. Even then, Groves questioned the document's authenticity until the American copy was located years later in the papers of Vice Admiral Wilson Brown, Jr., Roosevelt's naval aide, apparently misfiled by someone unaware of what Tube Alloys was, who thought it had something to do with naval guns.

Harry S. Truman (who had succeeded Roosevelt),

Groves appreciated the early British atomic research and the British scientists' contributions to the Manhattan Project, but stated that the United States would have succeeded without them. He considered British assistance "helpful but not vital", but acknowledged that "without active and continuing British interest, there probably would have been no atomic bomb to drop on Hiroshima." He considered Britain's key contributions to have been encouragement and support at the intergovernmental level, scientific aid, the production of powdered nickel in Wales, and preliminary studies and laboratory work.

Cooperation did not long survive the war. Roosevelt died on 12 April 1945, and the Hyde Park Agreement was not binding on subsequent administrations. In fact, it was physically lost. When Wilson raised the matter in a Combined Policy Committee meeting in June, the American copy could not be found. The British sent Stimson a photocopy on 18 July 1945. Even then, Groves questioned the document's authenticity until the American copy was located years later in the papers of Vice Admiral Wilson Brown, Jr., Roosevelt's naval aide, apparently misfiled by someone unaware of what Tube Alloys was, who thought it had something to do with naval guns.

Harry S. Truman (who had succeeded Roosevelt),  The next meeting of the Combined Policy Committee on 15 April 1946 produced no accord on collaboration, and resulted in an exchange of cables between Truman and Attlee. Truman cabled on 20 April that he did not see the communiqué he had signed as obligating the United States to assist Britain in designing, constructing and operating an atomic energy plant. Attlee's response on 6 June 1946 "did not mince words nor conceal his displeasure behind the nuances of diplomatic language." At issue was not just technical cooperation, which was fast disappearing, but the allocation of uranium ore. During the war this was of little concern, as Britain had not needed any ore, so all the production of the Congo mines and all the ore seized by the Alsos Mission had gone to the United States, but now it was also required by the British atomic project. Chadwick and Groves reached an agreement by which ore would be shared equally.

The

The next meeting of the Combined Policy Committee on 15 April 1946 produced no accord on collaboration, and resulted in an exchange of cables between Truman and Attlee. Truman cabled on 20 April that he did not see the communiqué he had signed as obligating the United States to assist Britain in designing, constructing and operating an atomic energy plant. Attlee's response on 6 June 1946 "did not mince words nor conceal his displeasure behind the nuances of diplomatic language." At issue was not just technical cooperation, which was fast disappearing, but the allocation of uranium ore. During the war this was of little concern, as Britain had not needed any ore, so all the production of the Congo mines and all the ore seized by the Alsos Mission had gone to the United States, but now it was also required by the British atomic project. Chadwick and Groves reached an agreement by which ore would be shared equally.

The

Britain contributed to the

Britain contributed to the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

by helping initiate the effort to build the first atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

s in the United States during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, and helped carry it through to completion in August 1945 by supplying crucial expertise. Following the discovery of nuclear fission

Nuclear fission is a reaction in which the nucleus of an atom splits into two or more smaller nuclei. The fission process often produces gamma photons, and releases a very large amount of energy even by the energetic standards of radio ...

in uranium

Uranium is a chemical element with the symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Uranium is weak ...

, scientists Rudolf Peierls

Sir Rudolf Ernst Peierls, (; ; 5 June 1907 – 19 September 1995) was a German-born British physicist who played a major role in Tube Alloys, Britain's nuclear weapon programme, as well as the subsequent Manhattan Project, the combined Allie ...

and Otto Frisch

Otto Robert Frisch FRS (1 October 1904 – 22 September 1979) was an Austrian-born British physicist who worked on nuclear physics. With Lise Meitner he advanced the first theoretical explanation of nuclear fission (coining the term) and first ...

at the University of Birmingham

, mottoeng = Through efforts to heights

, established = 1825 – Birmingham School of Medicine and Surgery1836 – Birmingham Royal School of Medicine and Surgery1843 – Queen's College1875 – Mason Science College1898 – Mason Univers ...

calculated, in March 1940, that the critical mass

In nuclear engineering, a critical mass is the smallest amount of fissile material needed for a sustained nuclear chain reaction. The critical mass of a fissionable material depends upon its nuclear properties (specifically, its nuclear fi ...

of a metallic sphere of pure uranium-235

Uranium-235 (235U or U-235) is an isotope of uranium making up about 0.72% of natural uranium. Unlike the predominant isotope uranium-238, it is fissile, i.e., it can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. It is the only fissile isotope that exi ...

was as little as , and would explode with the power of thousands of tons of dynamite

Dynamite is an explosive made of nitroglycerin, sorbents (such as powdered shells or clay), and stabilizers. It was invented by the Swedish chemist and engineer Alfred Nobel in Geesthacht, Northern Germany, and patented in 1867. It rapidl ...

. The Frisch–Peierls memorandum

The Frisch–Peierls memorandum was the first technical exposition of a practical nuclear weapon. It was written by expatriate German-Jewish physicists Otto Frisch and Rudolf Peierls in March 1940 while they were both working for Mark Oliphant a ...

prompted Britain to create an atomic bomb project, known as Tube Alloys

Tube Alloys was the research and development programme authorised by the United Kingdom, with participation from Canada, to develop nuclear weapons during the Second World War. Starting before the Manhattan Project in the United States, the ...

. Mark Oliphant, an Australian physicist working in Britain, was instrumental in making the results of the British MAUD Report known in the United States in 1941 by a visit in person. Initially the British project was larger and more advanced, but after the United States entered the war, the American project soon outstripped and dwarfed its British counterpart. The British government then decided to shelve its own nuclear ambitions, and participate in the American project.

In August 1943, the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As modern p ...

, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

, and the President of the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt, signed the Quebec Agreement

The Quebec Agreement was a secret agreement between the United Kingdom and the United States outlining the terms for the coordinated development of the science and engineering related to nuclear energy and specifically nuclear weapons. It was ...

, which provided for cooperation between the two countries. The Quebec Agreement established the Combined Policy Committee

The Quebec Agreement was a secret agreement between the United Kingdom and the United States outlining the terms for the coordinated development of the science and engineering related to nuclear energy and specifically nuclear weapons. It was ...

and the Combined Development Trust to coordinate the efforts of the United States, the United Kingdom and Canada. The subsequent Hyde Park Agreement in September 1944 extended this cooperation to the postwar period. A British Mission led by Wallace Akers assisted in the development of gaseous diffusion technology in New York. Britain also produced the powdered nickel required by the gaseous diffusion process. Another mission, led by Oliphant who acted as deputy director at the Berkeley Radiation Laboratory

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL), commonly referred to as the Berkeley Lab, is a United States national laboratory that is owned by, and conducts scientific research on behalf of, the United States Department of Energy. Located in ...

, assisted with the electromagnetic separation process. As head of the British Mission to the Los Alamos Laboratory

The Los Alamos Laboratory, also known as Project Y, was a secret laboratory established by the Manhattan Project and operated by the University of California during World War II. Its mission was to design and build the first atomic bombs. Ro ...

, James Chadwick

Sir James Chadwick, (20 October 1891 – 24 July 1974) was an English physicist who was awarded the 1935 Nobel Prize in Physics for his discovery of the neutron in 1932. In 1941, he wrote the final draft of the MAUD Report, which inspi ...

led a multinational team of distinguished scientists that included Sir Geoffrey Taylor, James Tuck, Niels Bohr

Niels Henrik David Bohr (; 7 October 1885 – 18 November 1962) was a Danish physicist who made foundational contributions to understanding atomic structure and quantum theory, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1922 ...

, Peierls, Frisch, and Klaus Fuchs

Klaus Emil Julius Fuchs (29 December 1911 – 28 January 1988) was a German theoretical physicist and atomic spy who supplied information from the American, British and Canadian Manhattan Project to the Soviet Union during and shortly af ...

, who was later revealed to be a Soviet atomic spy

Atomic spies or atom spies were people in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada who are known to have illicitly given information about nuclear weapons production or design to the Soviet Union during World War II and the early Col ...

. Four members of the British Mission became group leaders at Los Alamos. William Penney

William George Penney, Baron Penney, (24 June 19093 March 1991) was an English mathematician and professor of mathematical physics at the Imperial College London and later the rector of Imperial College London. He had a leading role in the ...

observed the bombing of Nagasaki

The United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945, respectively. The two bombings killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people, most of whom were civilians, and remain the o ...

and participated in the Operation Crossroads

Operation Crossroads was a pair of nuclear weapon tests conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll in mid-1946. They were the first nuclear weapon tests since Trinity in July 1945, and the first detonations of nuclear devices since the ...

nuclear tests in 1946.

Cooperation ended with the Atomic Energy Act of 1946

The Atomic Energy Act of 1946 (McMahon Act) determined how the United States would control and manage the nuclear technology it had jointly developed with its World War II allies, the United Kingdom and Canada. Most significantly, the Act ruled ...

, known as the McMahon Act, and Ernest Titterton

Sir Ernest William Titterton (4 March 1916 – 8 February 1990) was a British nuclear physicist.

A graduate of the University of Birmingham, Titterton worked in a research position under Mark Oliphant, who recruited him to work on radar ...

, the last British government employee, left Los Alamos on 12 April 1947. Britain then proceeded with High Explosive Research

High Explosive Research (HER) was the British project to develop atomic bombs independently after the Second World War. This decision was taken by a cabinet sub-committee on 8 January 1947, in response to apprehension of an American return ...

, its own nuclear weapons programme, and became the third country to test an independently developed nuclear weapon in October 1952.

Origins

The 1938

The 1938 discovery of nuclear fission

Nuclear fission was discovered in December 1938 by chemists Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann and physicists Lise Meitner and Otto Robert Frisch. Fission is a nuclear reaction or radioactive decay process in which the nucleus of an atom splits ...

in uranium

Uranium is a chemical element with the symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Uranium is weak ...

by Otto Robert Frisch

Otto Robert Frisch FRS (1 October 1904 – 22 September 1979) was an Austrian-born British physicist who worked on nuclear physics. With Lise Meitner he advanced the first theoretical explanation of nuclear fission (coining the term) and first ...

, Fritz Strassmann

Friedrich Wilhelm Strassmann (; 22 February 1902 – 22 April 1980) was a German chemist who, with Otto Hahn in December 1938, identified the element barium as a product of the bombardment of uranium with neutrons. Their observation was the ke ...

, Lise Meitner

Elise Meitner ( , ; 7 November 1878 – 27 October 1968) was an Austrian-Swedish physicist who was one of those responsible for the discovery of the element protactinium and nuclear fission. While working at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute on r ...

and Otto Hahn

Otto Hahn (; 8 March 1879 – 28 July 1968) was a German chemist who was a pioneer in the fields of radioactivity and radiochemistry. He is referred to as the father of nuclear chemistry and father of nuclear fission. Hahn and Lise Meitner ...

, raised the possibility that an extremely powerful atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

could be created. Refugees from Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and other fascist countries were particularly alarmed by the notion of a German nuclear weapon project. In the United States, three of them, Leo Szilard

Leo Szilard (; hu, Szilárd Leó, pronounced ; born Leó Spitz; February 11, 1898 – May 30, 1964) was a Hungarian-German-American physicist and inventor. He conceived the nuclear chain reaction in 1933, patented the idea of a nuclear ...

, Eugene Wigner

Eugene Paul "E. P." Wigner ( hu, Wigner Jenő Pál, ; November 17, 1902 – January 1, 1995) was a Hungarian-American theoretical physicist who also contributed to mathematical physics. He received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1963 "for his co ...

and Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theor ...

, were moved to write the Einstein–Szilárd letter to the President of the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt, warning of the danger. This led to the President creating the Advisory Committee on Uranium

The S-1 Executive Committee laid the groundwork for the Manhattan Project by initiating and coordinating the early research efforts in the United States, and liaising with the Tube Alloys Project in Britain.

In the wake of the discovery of nucle ...

. In Britain, Nobel Prize in Physics

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then " ...

laureates George Paget Thomson

Sir George Paget Thomson, FRS (; 3 May 189210 September 1975) was a British physicist and Nobel laureate in physics recognized for his discovery of the wave properties of the electron by electron diffraction.

Education and early life

Thomson ...

and William Lawrence Bragg

Sir William Lawrence Bragg, (31 March 1890 – 1 July 1971) was an Australian-born British physicist and X-ray crystallographer, discoverer (1912) of Bragg's law of X-ray diffraction, which is basic for the determination of crystal structu ...

were sufficiently concerned to take up the matter. Their concerns reached the Secretary of the Committee of Imperial Defence

The Committee of Imperial Defence was an important ''ad hoc'' part of the Government of the United Kingdom and the British Empire from just after the Second Boer War until the start of the Second World War. It was responsible for research, and som ...

, Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

Hastings Ismay

Hastings Lionel Ismay, 1st Baron Ismay (21 June 1887 – 17 December 1965), was a diplomat and general in the British Indian Army who was the first Secretary General of NATO. He also was Winston Churchill's chief military assistant during the ...

, who consulted with Sir Henry Tizard

Sir Henry Thomas Tizard (23 August 1885 – 9 October 1959) was an English chemist, inventor and Rector of Imperial College, who developed the modern "octane rating" used to classify petrol, helped develop radar in World War II, and led the fir ...

. Like many scientists, Tizard was sceptical of the likelihood of an atomic bomb being developed, reckoning the odds against success at 100,000 to 1.

Even at such long odds, the danger was sufficiently great to be taken seriously. Thomson, at Imperial College London

Imperial College London (legally Imperial College of Science, Technology and Medicine) is a public research university in London, United Kingdom. Its history began with Prince Albert, consort of Queen Victoria, who developed his vision for a cu ...

, and Mark Oliphant, an Australian physicist at the University of Birmingham

, mottoeng = Through efforts to heights

, established = 1825 – Birmingham School of Medicine and Surgery1836 – Birmingham Royal School of Medicine and Surgery1843 – Queen's College1875 – Mason Science College1898 – Mason Univers ...

, were tasked with carrying out a series of experiments on uranium. By February 1940, Thomson's team had failed to create a chain reaction in natural uranium, and he had decided that it was not worth pursuing. But at Birmingham, Oliphant's team had reached a strikingly different conclusion. Oliphant had delegated the task to two German refugee scientists, Rudolf Peierls

Sir Rudolf Ernst Peierls, (; ; 5 June 1907 – 19 September 1995) was a German-born British physicist who played a major role in Tube Alloys, Britain's nuclear weapon programme, as well as the subsequent Manhattan Project, the combined Allie ...

and Otto Frisch

Otto Robert Frisch FRS (1 October 1904 – 22 September 1979) was an Austrian-born British physicist who worked on nuclear physics. With Lise Meitner he advanced the first theoretical explanation of nuclear fission (coining the term) and first ...

, who could not work on the University's radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance (''ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, Marine radar, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor v ...

project because they were enemy alien

In customary international law, an enemy alien is any native, citizen, denizen or subject of any foreign nation or government with which a domestic nation or government is in conflict and who is liable to be apprehended, restrained, secured and ...

s and therefore lacked the necessary security clearance. They calculated the critical mass

In nuclear engineering, a critical mass is the smallest amount of fissile material needed for a sustained nuclear chain reaction. The critical mass of a fissionable material depends upon its nuclear properties (specifically, its nuclear fi ...

of a metallic sphere of pure uranium-235

Uranium-235 (235U or U-235) is an isotope of uranium making up about 0.72% of natural uranium. Unlike the predominant isotope uranium-238, it is fissile, i.e., it can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. It is the only fissile isotope that exi ...

, the only fissile

In nuclear engineering, fissile material is material capable of sustaining a nuclear fission chain reaction. By definition, fissile material can sustain a chain reaction with neutrons of thermal energy. The predominant neutron energy may be t ...

isotope

Isotopes are two or more types of atoms that have the same atomic number (number of protons in their nuclei) and position in the periodic table (and hence belong to the same chemical element), and that differ in nucleon numbers ( mass num ...

found in significant quantity in nature, and found that instead of tons, as everyone had assumed, as little as would suffice, which would explode with the power of thousands of tons of dynamite.

Oliphant took the Frisch–Peierls memorandum

The Frisch–Peierls memorandum was the first technical exposition of a practical nuclear weapon. It was written by expatriate German-Jewish physicists Otto Frisch and Rudolf Peierls in March 1940 while they were both working for Mark Oliphant a ...

to Tizard, and the MAUD Committee

The MAUD Committee was a British scientific working group formed during the Second World War. It was established to perform the research required to determine if an atomic bomb was feasible. The name MAUD came from a strange line in a telegram fro ...

was established to investigate further. It directed an intensive research effort, and in July 1941, produced two comprehensive reports that reached the conclusion that an atomic bomb was not only technically feasible, but could be produced before the war ended, perhaps in as little as two years. The Committee unanimously recommended pursuing the development of an atomic bomb as a matter of urgency, although it recognised that the resources required might be beyond those available to Britain. A new directorate known as Tube Alloys

Tube Alloys was the research and development programme authorised by the United Kingdom, with participation from Canada, to develop nuclear weapons during the Second World War. Starting before the Manhattan Project in the United States, the ...

was created to coordinate this effort. Sir John Anderson, the Lord President of the Council

The lord president of the Council is the presiding officer of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom and the fourth of the Great Officers of State, ranking below the Lord High Treasurer but above the Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal. The Lord ...

, became the minister responsible, and Wallace Akers from Imperial Chemical Industries

Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) was a British chemical company. It was, for much of its history, the largest manufacturer in Britain.

It was formed by the merger of four leading British chemical companies in 1926.

Its headquarters were at ...

(ICI) was appointed the director of Tube Alloys.

Early Anglo-American cooperation

In July 1940, Britain had offered to give the United States access to its scientific research, and theTizard Mission

The Tizard Mission, officially the British Technical and Scientific Mission, was a British delegation that visited the United States during WWII to obtain the industrial resources to exploit the military potential of the research and development ( ...

's John Cockcroft briefed American scientists on British developments. He discovered that the American project was smaller than the British, and not as far advanced. As part of the scientific exchange, the Maud Committee's findings were conveyed to the United States. Oliphant, one of the Maud Committee's members, flew to the United States in late August 1941, and discovered that vital information had not reached key American physicists. He met the Uranium Committee, and visited Berkeley, California

Berkeley ( ) is a city on the eastern shore of San Francisco Bay in northern Alameda County, California, United States. It is named after the 18th-century Irish bishop and philosopher George Berkeley. It borders the cities of Oakland and E ...

, where he spoke persuasively to Ernest O. Lawrence

Ernest Orlando Lawrence (August 8, 1901 – August 27, 1958) was an American nuclear physicist and winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1939 for his invention of the cyclotron. He is known for his work on uranium-isotope separation fo ...

, who was sufficiently impressed to commence his own research into uranium at the Berkeley Radiation Laboratory

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL), commonly referred to as the Berkeley Lab, is a United States national laboratory that is owned by, and conducts scientific research on behalf of, the United States Department of Energy. Located in ...

. Lawrence in turn spoke to James B. Conant

James Bryant Conant (March 26, 1893 – February 11, 1978) was an American chemist, a transformative President of Harvard University, and the first U.S. Ambassador to West Germany. Conant obtained a Ph.D. in Chemistry from Harvard in 1916. ...

, Arthur H. Compton

Arthur Holly Compton (September 10, 1892 – March 15, 1962) was an American physicist who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1927 for his 1923 discovery of the Compton effect, which demonstrated the particle nature of electromagnetic radia ...

and George B. Pegram

George Braxton Pegram (October 24, 1876 – August 12, 1958) was an American physicist who played a key role in the technical administration of the Manhattan Project. He graduated from Trinity College (now Duke University) in 1895, and taught hig ...

. Oliphant's mission was a success; key American physicists became aware of the potential power of an atomic bomb. Armed with British data, Vannevar Bush

Vannevar Bush ( ; March 11, 1890 – June 28, 1974) was an American engineer, inventor and science administrator, who during World War II headed the U.S. Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD), through which almost all warti ...

, the director of the Office of Scientific Research and Development

The Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) was an agency of the United States federal government created to coordinate scientific research for military purposes during World War II. Arrangements were made for its creation during May 1 ...

(OSRD), briefed Roosevelt and Vice President Henry A. Wallace

Henry Agard Wallace (October 7, 1888 – November 18, 1965) was an American politician, journalist, farmer, and businessman who served as the 33rd vice president of the United States, the 11th U.S. Secretary of Agriculture, and the 10th U.S. ...

in a meeting at the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in ...

on 9 October 1941.

The British and Americans exchanged nuclear information, but did not initially combine their efforts. British officials did not reply to an August 1941 offer by Bush and Conant to create a combined British and American project. In November 1941,

The British and Americans exchanged nuclear information, but did not initially combine their efforts. British officials did not reply to an August 1941 offer by Bush and Conant to create a combined British and American project. In November 1941, Frederick L. Hovde

Frederick Lawson Hovde (7 February 1908 – 1 March 1983) was an American chemical engineer, researcher, educator and president of Purdue University.

Born in Erie, Pennsylvania, Hovde received his Bachelor of Chemical Engineering from the Unive ...

, the head of the London liaison office of OSRD, raised the issue of cooperation and exchange of information with Anderson and Lord Cherwell

Frederick Alexander Lindemann, 1st Viscount Cherwell, ( ; 5 April 18863 July 1957) was a British physicist who was prime scientific adviser to Winston Churchill in World War II.

Lindemann was a brilliant intellectual, who cut through bureau ...

, who demurred, ostensibly over concerns about American security. Ironically, it was the British project that had already been penetrated by atomic spies

Atomic spies or atom spies were people in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada who are known to have illicitly given information about nuclear weapons production or design to the Soviet Union during World War II and the early ...

for the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

.

Yet the United Kingdom did not have the manpower or resources of the United States, and despite its early and promising start, Tube Alloys fell behind its American counterpart and was dwarfed by it. Britain was spending around £430,000 per year on research and development, and Metropolitan-Vickers

Metropolitan-Vickers, Metrovick, or Metrovicks, was a British heavy electrical engineering company of the early-to-mid 20th century formerly known as British Westinghouse. Highly diversified, it was particularly well known for its industrial el ...

was building gaseous diffusion units for uranium enrichment

Enriched uranium is a type of uranium in which the percent composition of uranium-235 (written 235U) has been increased through the process of isotope separation. Naturally occurring uranium is composed of three major isotopes: uranium-238 (238 ...

worth £150,000; but the Manhattan Project was spending £8,750,000 on research and development, and had let construction contracts worth £100,000,000 at the fixed wartime rate of four dollars to the pound. On 30 July 1942, Anderson advised the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As modern p ...

, Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

, that: "We must face the fact that ... urpioneering work ... is a dwindling asset and that, unless we capitalise it quickly, we shall be outstripped. We now have a real contribution to make to a 'merger.' Soon we shall have little or none."

By then, the positions of the two countries had reversed from what they were in 1941. The Americans had become suspicious that the British were seeking commercial advantages after the war, and Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointe ...

Leslie R. Groves, Jr.

Lieutenant General Leslie Richard Groves Jr. (17 August 1896 – 13 July 1970) was a United States Army Corps of Engineers officer who oversaw the construction of the Pentagon and directed the Manhattan Project, a top secret research project ...

, who took over command of the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

on 23 September 1942, wanted to tighten security with a policy of strict compartmentalisation similar to the one that the British had imposed on radar. American officials decided that the United States no longer needed outside help. The Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

, Henry L. Stimson

Henry Lewis Stimson (September 21, 1867 – October 20, 1950) was an American statesman, lawyer, and Republican Party politician. Over his long career, he emerged as a leading figure in U.S. foreign policy by serving in both Republican and ...

, felt that since the United States was doing "ninety percent of the work" on the bomb, it would be "better for us to go along for the present without sharing anything more than we could help". In December 1942, Roosevelt agreed to restricting the flow of information to what Britain could use during the war, even if doing so slowed down the American project. In retaliation, the British stopped sending information and scientists to America, and the Americans then stopped all information sharing.

The British considered how they would produce a bomb without American help. A gaseous diffusion plant to produce of weapons-grade

Weapons-grade nuclear material is any fissionable nuclear material that is pure enough to make a nuclear weapon or has properties that make it particularly suitable for nuclear weapons use. Plutonium and uranium in grades normally used in nucle ...

uranium per day was estimated to cost up to £3,000,000 in research and development, and anything up to £50,000,000 to build in wartime Britain. A nuclear reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a fission nuclear chain reaction or nuclear fusion reactions. Nuclear reactors are used at nuclear power plants for electricity generation and in nuclear marine propulsion. Heat fr ...

to produce of plutonium

Plutonium is a radioactive chemical element with the symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is an actinide metal of silvery-gray appearance that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exh ...

per day would have to be built in Canada. It would take up to five years to build and cost £5,000,000. The project would also require facilities for producing the required heavy water for the reactor costing between £5,000,000 and £10,000,000, and for producing uranium metal £1,500,000. The project would need overwhelming priority, as it was estimated to require 20,000 workers, many of them highly skilled, 500,000 tons of steel, and 500,000 kW of electricity. Disruption to other wartime projects would be inevitable, and it was unlikely to be ready in time to affect the outcome of the war in Europe. The unanimous response was that before embarking on this, another effort should be made to obtain American cooperation.

Cooperation resumes

By March 1943 Conant decided that British help would benefit some areas of the project. In particular, the Manhattan Project could benefit enough from assistance from

By March 1943 Conant decided that British help would benefit some areas of the project. In particular, the Manhattan Project could benefit enough from assistance from James Chadwick

Sir James Chadwick, (20 October 1891 – 24 July 1974) was an English physicist who was awarded the 1935 Nobel Prize in Physics for his discovery of the neutron in 1932. In 1941, he wrote the final draft of the MAUD Report, which inspi ...

, the discoverer of the neutron

The neutron is a subatomic particle, symbol or , which has a neutral (not positive or negative) charge, and a mass slightly greater than that of a proton. Protons and neutrons constitute the atomic nucleus, nuclei of atoms. Since protons and ...

, and several other British scientists to warrant the risk of revealing weapon design secrets. Bush, Conant and Groves wanted Chadwick and Peierls to discuss bomb design with Robert Oppenheimer, and Kellogg still wanted British comments on the design of the gaseous diffusion plant.

Churchill took up the matter with Roosevelt at the Washington Conference on 25 May 1943, and Churchill thought that Roosevelt gave the reassurances he sought; but there was no follow-up. Bush, Stimson and William Bundy met Churchill, Cherwell and Anderson at 10 Downing Street

10 Downing Street in London, also known colloquially in the United Kingdom as Number 10, is the official residence and executive office of the first lord of the treasury, usually, by convention, the prime minister of the United Kingdom. Along w ...

in London. None of them was aware that Roosevelt had already made his decision, writing to Bush on 20 July 1943 with instructions to "renew, in an inclusive manner, the full exchange with the British Government regarding Tube Alloys."

Stimson, who had just finished a series of arguments with the British about the need for an invasion of France

France has been invaded on numerous occasions, by foreign powers or rival French governments; there have also been unimplemented invasion plans.

* the 1746 War of the Austrian Succession, Austria-Italian forces supported by the British navy attemp ...

, was reluctant to appear to disagree with them about everything, and spoke in conciliatory terms about the need for good post-war relations between the two countries. For his part, Churchill disavowed interest in the commercial applications of nuclear technology. The reason for British concern about the post-war cooperation, Cherwell explained, was not commercial concerns, but so that Britain would have nuclear weapons after the war. Anderson then drafted an agreement for full interchange, which Churchill re-worded "in more majestic language". News arrived in London of Roosevelt's decision on 27 July, and Anderson was dispatched to Washington with the draft agreement. Churchill and Roosevelt signed what became known as the Quebec Agreement

The Quebec Agreement was a secret agreement between the United Kingdom and the United States outlining the terms for the coordinated development of the science and engineering related to nuclear energy and specifically nuclear weapons. It was ...

at the Quebec Conference on 19 August 1943.

The Quebec Agreement established the Combined Policy Committee

The Quebec Agreement was a secret agreement between the United Kingdom and the United States outlining the terms for the coordinated development of the science and engineering related to nuclear energy and specifically nuclear weapons. It was ...

to coordinate the efforts of the United States, United Kingdom and Canada. Stimson, Bush and Conant served as the American members of the Combined Policy Committee, Field Marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, ordinarily senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army and as such few persons are appointed to it. It is considered as ...

Sir John Dill

Sir John Greer Dill, (25 December 1881 – 4 November 1944) was a senior British Army officer with service in both the First World War and the Second World War. From May 1940 to December 1941 he was the Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS ...

and Colonel J. J. Llewellin were the British members, and C. D. Howe was the Canadian member. Llewellin returned to the United Kingdom at the end of 1943 and was replaced on the committee by Sir Ronald Ian Campbell

Sir Ronald Ian Campbell (7 June 1890 – 22 April 1983) was a British diplomat.

Campbell was the second son of Sir Guy Campbell, 3rd Baronet (see Campbell baronets), and Nina, daughter of Frederick Lehmann. He was educated at Eton and gradua ...

, who in turn was replaced by the British Ambassador to the United States, Lord Halifax

Edward Frederick Lindley Wood, 1st Earl of Halifax, (16 April 1881 – 23 December 1959), known as The Lord Irwin from 1925 until 1934 and The Viscount Halifax from 1934 until 1944, was a senior British Conservative politician of the 19 ...

, in early 1945. Dill died in Washington, D.C., in November 1944 and was replaced both as Chief of the British Joint Staff Mission and as a member of the Combined Policy Committee by Field Marshal Sir Henry Maitland Wilson

Field Marshal Henry Maitland Wilson, 1st Baron Wilson, (5 September 1881 – 31 December 1964), also known as Jumbo Wilson, was a senior British Army officer of the 20th century. He saw active service in the Second Boer War and then during the ...

.

Even before the Quebec Agreement was signed, Akers had already cabled London with instructions that Chadwick, Peierls, Oliphant and Francis Simon should leave immediately for North America. They arrived on 19 August, the day it was signed, expecting to be able to talk to American scientists, but were unable to do so. Two weeks would pass before American officials learnt of the contents of the Quebec Agreement. Over the next two years, the Combined Policy Committee met only eight times.

The first occasion was on 8 September 1943, on the afternoon after Stimson discovered that he was the chairman. The first meeting established a Technical Subcommittee chaired by Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

Wilhelm D. Styer

Wilhelm Delp Styer (22 July 1893 – 26 February 1975) was a lieutenant general in the United States Army during World War II. A graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point with the class of 1916, he was commissioned into the ...

. Because the Americans did not want Akers on the Technical Subcommittee due to his ICI background, Llewellin nominated Chadwick, whom he also wanted to be Head of the British Mission to the Manhattan Project. The other members were Richard C. Tolman

Richard Chace Tolman (March 4, 1881 – September 5, 1948) was an American mathematical physicist and physical chemist who made many contributions to statistical mechanics. He also made important contributions to theoretical cosmology in t ...

, who was Groves's scientific adviser, and C. J. Mackenzie, the president of the Canadian National Research Council. It was agreed that the Technical Committee could act without consulting the Combined Policy Committee whenever its decision was unanimous. The Technical Subcommittee held its first meeting on 10 September, but negotiations dragged on. The Combined Policy Committee ratified the proposals in December 1943, by which time several British scientists had already commenced working on the Manhattan Project in the United States.

There remained the issue of cooperation between the Manhattan's Project's Metallurgical Laboratory

The Metallurgical Laboratory (or Met Lab) was a scientific laboratory at the University of Chicago that was established in February 1942 to study and use the newly discovered chemical element plutonium. It researched plutonium's chemistry and m ...

in Chicago and the Montreal Laboratory. At the Combined Policy Committee meeting on 17 February 1944, Chadwick pressed for resources to build a nuclear reactor at what is now known as the Chalk River Laboratories

Chalk River Laboratories (french: Laboratoires de Chalk River; also known as CRL, Chalk River Labs and formerly Chalk River Nuclear Laboratories, CRNL) is a Canadian nuclear research facility in Deep River, about north-west of Ottawa.

CRL is ...

. Britain and Canada agreed to pay the cost of this project, but the United States had to supply the heavy water. At that time, the United States controlled, by a supply contract, the only major production site on the continent, that of the Consolidated Mining and Smelting Company at Trail, British Columbia

Trail is a city in the West Kootenay region of the Interior of British Columbia, Canada. It was named after the Dewdney Trail, which passed through the area. The town was first called Trail Creek or Trail Creek Landing, and the name was short ...

. Given that it was unlikely to have any impact on the war, Conant in particular was cool about the proposal, but heavy water reactors were of great interest. Groves was willing to support the effort and supply the heavy water required, but with certain restrictions. The Montreal Laboratory would have access to data from the research reactors at Argonne and the X-10 Graphite Reactor at Oak Ridge, but not from the production reactors at the Hanford Site

The Hanford Site is a decommissioned nuclear production complex operated by the United States federal government on the Columbia River in Benton County in the U.S. state of Washington. The site has been known by many names, including SiteW a ...

; nor would they be given any information about plutonium. This arrangement was formally approved by the Combined Policy Committee meeting on 19 September 1944. The Canadian ZEEP

The ZEEP (Zero Energy Experimental Pile) reactor was a nuclear reactor built at the Chalk River Laboratories near Chalk River, Ontario, Canada (which superseded the Montreal Laboratory for nuclear research in Canada). ZEEP first went critical ...

(Zero Energy Experimental Pile) reactor went critical

Critical or Critically may refer to:

*Critical, or critical but stable, medical states

**Critical, or intensive care medicine

* Critical juncture, a discontinuous change studied in the social sciences.

*Critical Software, a company specializing ...

on 5 September 1945.

Chadwick supported British involvement in the Manhattan Project to the fullest extent, abandoning any hopes of a British project during the war. With Churchill's backing, he attempted to ensure that every request from Groves for assistance was honoured. While the pace of research was easing as the war entered its final phase, these scientists were still in great demand, and it fell to Anderson, Cherwell and Sir Edward Appleton, the Permanent Secretary

A permanent secretary (also known as a principal secretary) is the most senior civil servant of a department or ministry charged with running the department or ministry's day-to-day activities. Permanent secretaries are the non-political civil ...

of the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research Department of Scientific and Industrial Research, abbreviated DSIR was the name of several British Empire organisations founded after the 1923 Imperial Conference to foster intra-Empire trade and development.

* Department of Scientific and Industria ...

, which was responsible for Tube Alloys, to prise them away from the wartime projects in which they were invariably engaged.

The September 1944 Hyde Park Agreement extended both commercial and military cooperation into the post-war period. The Quebec Agreement specified that nuclear weapons would not be used against another country without mutual consent. On 4 July 1945, Wilson agreed that the use of nuclear weapons against Japan would be recorded as a decision of the Combined Policy Committee.

Gaseous diffusion project

Tube Alloys made its greatest advances in gaseous diffusion technology, and Chadwick had originally hoped that the pilot plant at least would be built in Britain. Gaseous diffusion technology was devised by Simon and three expatriates, Nicholas Kurti from Hungary, Heinrich Kuhn from Germany, and Henry Arms from the United States, at theClarendon Laboratory

The Clarendon Laboratory, located on Parks Road within the Science Area in Oxford, England (not to be confused with the Clarendon Building, also in Oxford), is part of the Department of Physics at Oxford University. It houses the atomic and ...

in 1940. The prototype gaseous diffusion equipment, two two-stage models and two ten-stage models, was manufactured by Metropolitan-Vickers

Metropolitan-Vickers, Metrovick, or Metrovicks, was a British heavy electrical engineering company of the early-to-mid 20th century formerly known as British Westinghouse. Highly diversified, it was particularly well known for its industrial el ...

at a cost of £150,000 for the four units. Two single-stage machines were later added. Delays in delivery meant that experiments with the single-stage machine did not commence until June 1943, and with the two-stage machine until August 1943. The two ten-stage machines were delivered in August and November 1943, but by this time the research programme they had been built for had been overtaken by events.

The Quebec Agreement allowed Simon and Peierls to meet with representatives of Kellex, who were designing and building the American gaseous diffusion plant, Union Carbide and Carbon, who would operate it, and

The Quebec Agreement allowed Simon and Peierls to meet with representatives of Kellex, who were designing and building the American gaseous diffusion plant, Union Carbide and Carbon, who would operate it, and Harold Urey

Harold Clayton Urey ( ; April 29, 1893 – January 5, 1981) was an American physical chemist whose pioneering work on isotopes earned him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1934 for the discovery of deuterium. He played a significant role in th ...

's Substitute Alloy Materials (SAM) Laboratories at Columbia University, the Manhattan Project's centre tasked with research and development of the process. The year's loss of cooperation cost the Manhattan Project dearly. The corporations were committed to tight schedules, and the engineers were unable to incorporate British proposals that would involve major changes. Nor would it be possible to build a second plant. Nonetheless, the Americans were still eager for British assistance, and Groves asked for a British mission to be sent to assist the gaseous diffusion project. In the meantime, Simon and Peierls were attached to Kellex.

The British mission consisting of Akers and fifteen British experts arrived in December 1943. This was a critical time. Severe problems had been encountered with the Norris-Adler barrier. Nickel

Nickel is a chemical element with symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel is a hard and ductile transition metal. Pure nickel is chemically reactive but large pieces are slow t ...

powder and electro-deposited nickel mesh diffusion barriers were pioneered by American chemist Edward Adler and British interior decorator Edward Norris at the SAM Laboratories. A decision had to be made whether to persevere with it or switch to a powdered nickel barrier based upon British technology that had been developed by Kellex. Up to this point, both were under development. The SAM Laboratory had 700 people working on gaseous diffusion and Kellex had about 900. The British experts conducted a thorough review, and agreed that the Kellex barrier was superior, but felt that it would be unlikely to be ready in time. Kellex's technical director, Percival C. Keith, disagreed, arguing that his company could get it ready and produce it more quickly than the Norris-Adler barrier. Groves listened to the British experts before he formally adopted the Kellex barrier on 5 January 1944.

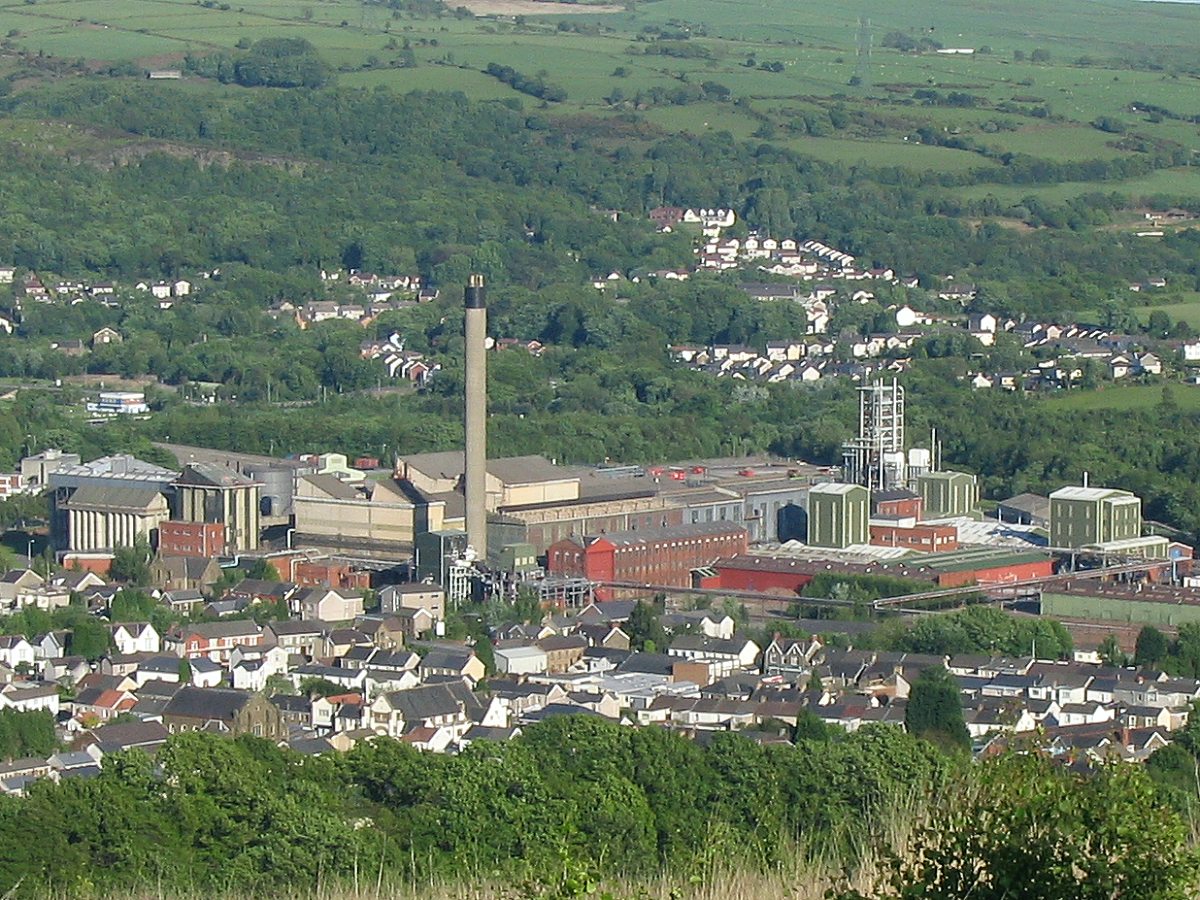

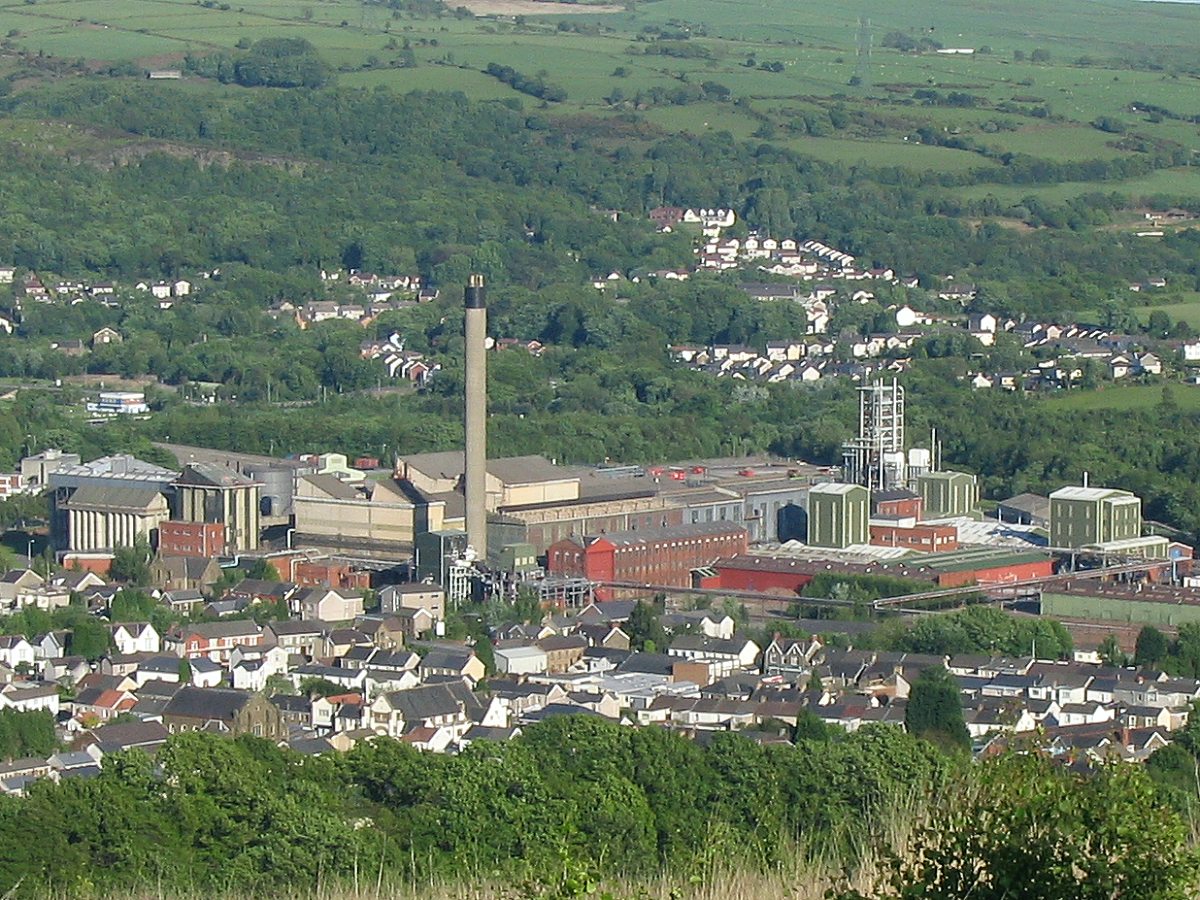

The United States Army assumed responsibility for procuring sufficient quantities of the right type of powdered nickel. In this, the British were able to help. The only company that manufactured it was the Mond Nickel Company

The Mond Nickel Company Limited was a United Kingdom-based mining company, formed on September 20, 1900, licensed in Canada to carry on business in the province of Ontario, from October 16, 1900. The firm was founded by Ludwig Mond (1839-1909) to ...

at Clydach in Wales. By the end of June 1945, it had supplied the Manhattan Project with of nickel powder, paid for by the British government and supplied to the United States under Reverse Lend-Lease

Lend-Lease, formally the Lend-Lease Act and introduced as An Act to Promote the Defense of the United States (), was a policy under which the United States supplied the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union and other Allied nations with food, oil, ...

.

The Americans planned to have the K-25 plant in full production by June or July 1945. Having taken two years to get the prototype stages working, the British experts regarded this as incredibly optimistic, and felt that, barring a miracle, it would be unlikely to reach that point before the end of 1946. This opinion offended their American counterparts and dampened the enthusiasm for cooperation, and the British mission returned to the United Kingdom in January 1944. Armed with the British Mission's report, Chadwick and Oliphant were able to persuade Groves to reduce K-25's enrichment target; the output of K-25 would be enriched to weapons grade by being fed into the electromagnetic plant. Despite the British Mission's pessimistic forecasts, K-25 was producing enriched uranium in June 1945.

After the rest of the mission departed, Peierls, Kurti and Fuchs remained in New York, where they worked with Kellex. They were joined there by Tony Skyrme

Tony Hilton Royle Skyrme (; 5 December 1922, Lewisham – 25 June 1987) was a British physicist.

He proposed modelling the effective interaction between nucleons in nuclei by a zero-range potential. This idea is still widely used today in ...

and Frank Kearton

Christopher Frank Kearton, Baron Kearton, , (17 February 1911 – 2 July 1992), usually known as Frank Kearton, was a British life peer in the House of Lords. He was also a scientist and industrialist and former Chancellor of the University o ...

, who arrived in March 1944. Kurti returned to England in April 1944 and Kearton in September. Peierls moved on to the Los Alamos Laboratory

The Los Alamos Laboratory, also known as Project Y, was a secret laboratory established by the Manhattan Project and operated by the University of California during World War II. Its mission was to design and build the first atomic bombs. Ro ...

in February 1944; Skyrme followed in July, and Fuchs in August.

Electromagnetic project

On 26 May 1943, Oliphant wrote to Appleton to say that he had been considering the problem ofelectromagnetic isotope separation

A calutron is a mass spectrometer originally designed and used for separating the isotopes of uranium. It was developed by Ernest Lawrence during the Manhattan Project and was based on his earlier invention, the cyclotron. Its name was derived ...

, and believed that he had devised a better method than Lawrence's, one which would result in a five to tenfold improvement in efficiency, and make it more practical to use the process in Britain. His proposal was reviewed by Akers, Chadwick, Peierls and Simon, who agreed that it was sound. While the majority of scientific opinion in Britain favoured the gaseous diffusion method, there was still a possibility that electromagnetic separation might be useful as a final stage in the enrichment process, taking uranium that had already been enriched to 50 per cent by the gaseous process, and enriching it to pure uranium-235. Accordingly, Oliphant was released from the radar project to work on Tube Alloys, conducting experiments on his method at the University of Birmingham.

Oliphant met Groves and Oppenheimer in Washington, D.C., on 18 September 1943, and they attempted to persuade him to join the Los Alamos Laboratory, but Oliphant felt that he would be of more use assisting Lawrence on the electromagnetic project. Accordingly, the Technical Subcommittee directed that Oliphant and six assistants would go to Berkeley, and later move on to Los Alamos. Oliphant found that he and Lawrence had quite different designs, and that the American one was frozen, but Lawrence, who had expressed a desire for Oliphant to join him on the electromagnetic project as early as 1942, was eager for Oliphant's assistance. Oliphant secured the services of a fellow Australian physicist, Harrie Massey

Sir Harrie Stewart Wilson Massey (16 May 1908 – 27 November 1983) was an Australian mathematical physicist who worked primarily in the fields of atomic and atmospheric physics.

A graduate of the University of Melbourne and Cambridge Unive ...

, who had been working for the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

on magnetic mines

A naval mine is a self-contained explosive device placed in water to damage or destroy surface ships or submarines. Unlike depth charges, mines are deposited and left to wait until they are triggered by the approach of, or contact with, any v ...

, along with James Stayers and Stanley Duke, who had worked with him on the cavity magnetron

The cavity magnetron is a high-power vacuum tube used in early radar systems and currently in microwave ovens and linear particle accelerators. It generates microwaves using the interaction of a stream of electrons with a magnetic field whi ...

. This initial group set out for Berkeley in a B-24 Liberator

The Consolidated B-24 Liberator is an American heavy bomber, designed by Consolidated Aircraft of San Diego, California. It was known within the company as the Model 32, and some initial production aircraft were laid down as export models ...

bomber in November 1943. Oliphant found that Berkeley had shortages of key skills, particularly physicists, chemists and engineers. He prevailed on Sir David Rivett

Sir Albert Cherbury David Rivett, KCMG (4 December 1885 – 1 April 1961) was an Australian chemist and science administrator.

Background and education

Rivett was born at Port Esperance, Tasmania, Australia, a son of the Rev. Albert Rivett ( ...

, the head of the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research

The Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) is South Africa's central and premier scientific research and development organisation. It was established by an act of parliament in 1945 and is situated on its own campus in the c ...

in Australia, to release Eric Burhop

Eric Henry Stoneley Burhop, (31 January 191122 January 1980) was an Australian physicist and humanitarian.

A graduate of the University of Melbourne, Burhop was awarded an 1851 Exhibition Scholarship to study at the Cavendish Laboratory under ...

to work on the project. His requests for personnel were met, and the British mission at Berkeley grew in number to 35, two of whom, Robin Williams and George Page, were New Zealanders.

Members of the British mission occupied several key positions in the electromagnetic project. Oliphant became Lawrence's ''de facto'' deputy, and was in charge of the Berkeley Radiation Laboratory when Lawrence was absent. His enthusiasm for the electromagnetic project was rivalled only by Lawrence's, and his involvement went beyond scientific problems, extending to policy questions such as whether to expand the electromagnetic plant, although in this he was unsuccessful. The British chemists made important contributions, particularly Harry Emeléus and Philip Baxter

Sir John Philip Baxter (7 May 1905 – 5 September 1989) was a British chemical engineer. He was the second director of the University of New South Wales from 1953, continuing as vice-chancellor when the position's title was changed in 1955. Un ...

, a chemist who had been research manager at ICI, was sent to the Manhattan Project's Clinton Engineering Works at Oak Ridge, Tennessee

Oak Ridge is a city in Anderson County, Tennessee, Anderson and Roane County, Tennessee, Roane counties in the East Tennessee, eastern part of the U.S. state of Tennessee, about west of downtown Knoxville, Tennessee, Knoxville. Oak Ridge's popu ...

, in 1944 in response to a request for assistance with uranium chemistry, and became personal assistant to the general manager. His status as an ICI employee was of no concern to Groves. The British mission was given complete access to the electromagnetic project, both in Berkeley and at the Y-12 electromagnetic separation plant in Oak Ridge. While some of the British mission remained at Berkeley or Oak Ridge only for a few weeks, most stayed until the end of the war. Oliphant returned to Britain in March 1945, and was replaced as head of the British mission in Berkeley by Massey.

Los Alamos Laboratory

When cooperation resumed in September 1943, Groves and Oppenheimer revealed the existence of the Los Alamos Laboratory to Chadwick, Peierls and Oliphant. Oppenheimer wanted all three to proceed to Los Alamos as soon as possible, but it was decided that Oliphant would go to Berkeley to work on the electromagnetic process and Peierls would go to New York to work on the gaseous diffusion process. The task then fell to Chadwick. The original idea, favoured by Groves, was that the British scientists would work as a group under Chadwick, who would farm out work to them. This was soon discarded in favour of having the British Mission fully integrated into the laboratory. They worked in most of its divisions, only being excluded from plutonium chemistry and metallurgy.

First to arrive was Otto Frisch and Ernest Titterton and his wife Peggy, who reached Los Alamos on 13 December 1943. At Los Alamos Frisch continued his work on critical mass studies, for which Titterton developed electronic circuitry for high voltage generators, X-ray generators, timers and firing circuits. Peggy Titterton, a trained physics and metallurgy laboratory assistant, was one of the few women working at Los Alamos in a technical role. Chadwick arrived on 12 January 1944, but only stayed for a few months before returning to Washington, D.C.

When Oppenheimer appointed

When cooperation resumed in September 1943, Groves and Oppenheimer revealed the existence of the Los Alamos Laboratory to Chadwick, Peierls and Oliphant. Oppenheimer wanted all three to proceed to Los Alamos as soon as possible, but it was decided that Oliphant would go to Berkeley to work on the electromagnetic process and Peierls would go to New York to work on the gaseous diffusion process. The task then fell to Chadwick. The original idea, favoured by Groves, was that the British scientists would work as a group under Chadwick, who would farm out work to them. This was soon discarded in favour of having the British Mission fully integrated into the laboratory. They worked in most of its divisions, only being excluded from plutonium chemistry and metallurgy.

First to arrive was Otto Frisch and Ernest Titterton and his wife Peggy, who reached Los Alamos on 13 December 1943. At Los Alamos Frisch continued his work on critical mass studies, for which Titterton developed electronic circuitry for high voltage generators, X-ray generators, timers and firing circuits. Peggy Titterton, a trained physics and metallurgy laboratory assistant, was one of the few women working at Los Alamos in a technical role. Chadwick arrived on 12 January 1944, but only stayed for a few months before returning to Washington, D.C.

When Oppenheimer appointed Hans Bethe

Hans Albrecht Bethe (; July 2, 1906 – March 6, 2005) was a German-American theoretical physicist who made major contributions to nuclear physics, astrophysics, quantum electrodynamics, and solid-state physics, and who won the 1967 Nobel ...

as the head of the laboratory's prestigious Theoretical (T) Division, he offended Edward Teller

Edward Teller ( hu, Teller Ede; January 15, 1908 – September 9, 2003) was a Hungarian-American theoretical physicist who is known colloquially as "the father of the hydrogen bomb" (see the Teller–Ulam design), although he did not care for ...

, who was given his own group, tasked with investigating Teller's "Super" bomb, and eventually assigned to Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi (; 29 September 1901 – 28 November 1954) was an Italian (later naturalized American) physicist and the creator of the world's first nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1. He has been called the "architect of the nuclear age" an ...

's F Division. Oppenheimer then wrote to Groves requesting that Peierls be sent to take Teller's place in T Division. Peierls arrived from New York on 8 February 1944, and subsequently succeeded Chadwick as head of the British Mission at Los Alamos. Egon Bretscher worked in Teller's Super group, as did Anthony French

Anthony Philip French (November 19, 1920 – February 3, 2017) was a British professor of physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He was born in Brighton, England. French was a graduate of Cambridge University, receiving his ...

, who later recalled that "never at any time did I have anything to do with the fission bomb once I went to Los Alamos." Four members of the British Mission became group leaders: Bretscher (Super Experimentation), Frisch (Critical Assemblies and Nuclear Specifications), Peierls (Implosion Hydrodynamics) and George Placzek (Composite Weapon).

Niels Bohr

Niels Henrik David Bohr (; 7 October 1885 – 18 November 1962) was a Danish physicist who made foundational contributions to understanding atomic structure and quantum theory, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1922 ...

and his son Aage

Aage is a Danish masculine given name and a less common spelling of the Norwegian given name Åge. Variants include the Swedish name Åke. People with the name Aage include:

* Aage Bendixen (1887–1973), Danish actor

* Aage Berntsen (1885–195 ...

, a physicist who acted as his father's assistant, arrived on 30 December on the first of several visits as a consultant. Bohr and his family had escaped from occupied Denmark

At the outset of World War II in September 1939, Denmark declared itself neutral. For most of the war, the country was a protectorate and then an occupied territory of Germany. The decision to occupy Denmark was taken in Berlin on 17 Decemb ...

to Sweden. A De Havilland Mosquito

The de Havilland DH.98 Mosquito is a British twin-engined, shoulder-winged, multirole combat aircraft, introduced during the World War II, Second World War. Unusual in that its frame was constructed mostly of wood, it was nicknamed the "Wooden ...

bomber brought him to England where he joined Tube Alloys. In America, he was able to visit Oak Ridge and Los Alamos, where he found many of his former students. Bohr acted as a critic, a facilitator and a role model for younger scientists. He arrived at a critical time, and several nuclear fission studies and experiments were conducted at his instigation. He played an important role in the development of the uranium tamper, and in the design and adoption of the modulated neutron initiator

A modulated neutron initiator is a neutron source capable of producing a burst of neutrons on activation. It is a crucial part of some nuclear weapons, as its role is to "kick-start" the chain reaction at the optimal moment when the configuration i ...

. His presence boosted morale, and helped improve the administration of the laboratory to strengthen ties with the Army.

Nuclear physicists knew about fission, but not the hydrodynamics of conventional explosions. As a result, there were two additions to the team that made significant contributions in this area of physics. First was James Tuck whose field of expertise was in shaped charges used in anti tank

Anti-tank warfare originated from the need to develop technology and tactics to destroy tanks during World War I. Since the Triple Entente deployed the first tanks in 1916, the German Empire developed the first anti-tank weapons. The first deve ...

weapons for armour piercing

Armour-piercing ammunition (AP) is a type of projectile designed to penetrate either body armour or vehicle armour.

From the 1860s to 1950s, a major application of armour-piercing projectiles was to defeat the thick armour carried on many warsh ...

. In terms of the plutonium bomb the scientists at Los Alamos were trying to wrestle with the idea of the implosion issue. Tuck was sent to Los Alamos in April 1944 and used a radical concept of explosive lens

An explosive lens—as used, for example, in nuclear weapons—is a highly specialized shaped charge. In general, it is a device composed of several explosive charges. These charges are arranged and formed with the intent to control the shape ...

ing which was then put into place. Tuck also designed the Urchin initiator for the bomb working closely with Seth Neddermeyer

Seth Henry Neddermeyer (September 16, 1907 – January 29, 1988) was an American physicist who co-discovered the muon, and later championed the Implosion-type nuclear weapon while working on the Manhattan Project at the Los Alamos Labor ...

. This work was crucial to the success of the plutonium

Plutonium is a radioactive chemical element with the symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is an actinide metal of silvery-gray appearance that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exh ...

atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

: Italian-American scientist Bruno Rossi

Bruno Benedetto Rossi (; ; 13 April 1905 – 21 November 1993) was an Italian experimental physicist. He made major contributions to particle physics and the study of cosmic rays. A 1927 graduate of the University of Bologna, he became in ...