Boccaccio on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

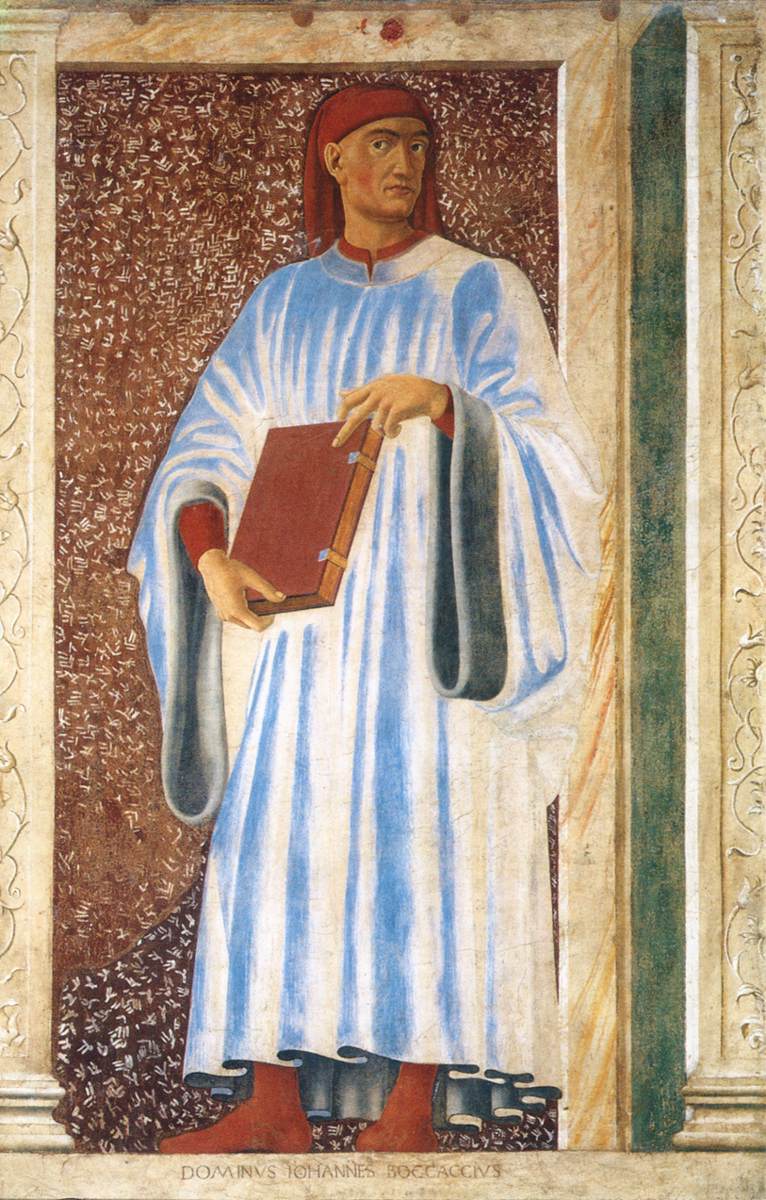

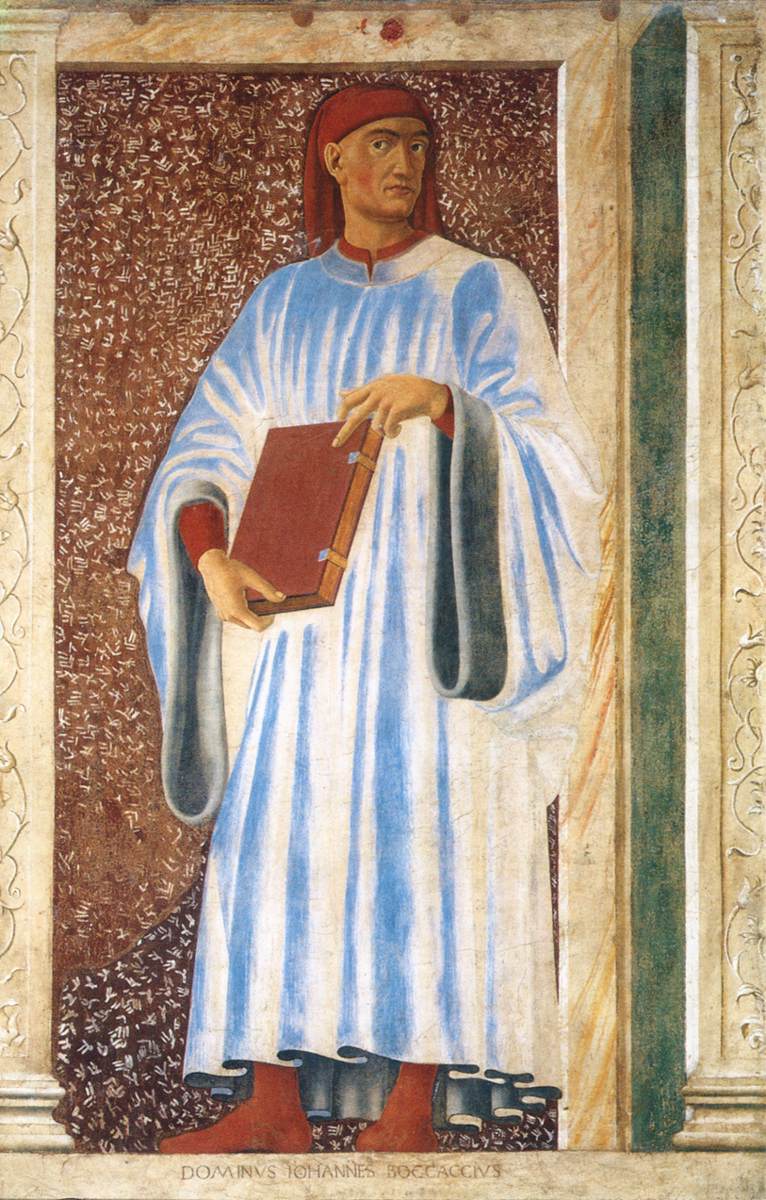

Giovanni Boccaccio (, , ; 16 June 1313 – 21 December 1375) was an Italian writer, poet, correspondent of

Giovanni Boccaccio (, , ; 16 June 1313 – 21 December 1375) was an Italian writer, poet, correspondent of

The details of Boccaccio's birth are uncertain. He was born in

The details of Boccaccio's birth are uncertain. He was born in

In Naples, Boccaccio began what he considered his true vocation of poetry. Works produced in this period include '' Il Filostrato'' and ''

In Naples, Boccaccio began what he considered his true vocation of poetry. Works produced in this period include '' Il Filostrato'' and '' In Florence, the overthrow of Walter of Brienne brought about the government of ''popolo minuto'' ("small people", workers). It diminished the influence of the nobility and the wealthier merchant classes and assisted in the relative decline of Florence. The city was hurt further in 1348 by the

In Florence, the overthrow of Walter of Brienne brought about the government of ''popolo minuto'' ("small people", workers). It diminished the influence of the nobility and the wealthier merchant classes and assisted in the relative decline of Florence. The city was hurt further in 1348 by the  In 1360, Boccaccio began work on ''

In 1360, Boccaccio began work on ''

Source

* Patrick, James A.(2007). ''Renaissance And Reformation''. Marshall Cavendish Corp. .

De claris mulieribus

From th

Rare Book and Special Collections Division

at the

Genealogie deorum gentilium Johannis Boccacii de Certaldo liber

a

Somni

De mulieribus claris

a

Somni

{{DEFAULTSORT:Boccaccio, Giovanni 1313 births 1375 deaths People from Certaldo Italian Renaissance humanists Italian Renaissance writers Italian male poets Italian Roman Catholics Medieval Italian diplomats Medieval Latin poets 14th-century people of the Republic of Florence 14th-century Italian historians 14th-century Italian poets 14th-century Latin writers 14th-century diplomats Deaths from edema

Giovanni Boccaccio (, , ; 16 June 1313 – 21 December 1375) was an Italian writer, poet, correspondent of

Giovanni Boccaccio (, , ; 16 June 1313 – 21 December 1375) was an Italian writer, poet, correspondent of Petrarch

Francesco Petrarca (; 20 July 1304 – 18/19 July 1374), commonly anglicized as Petrarch (), was a scholar and poet of early Renaissance Italy, and one of the earliest humanists.

Petrarch's rediscovery of Cicero's letters is often credited ...

, and an important Renaissance humanist

Renaissance humanism was a revival in the study of classical antiquity, at first in Italy and then spreading across Western Europe in the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries. During the period, the term ''humanist'' ( it, umanista) referred to teache ...

. Born in the town of Certaldo, he became so well known as a writer that he was sometimes simply known as "the Certaldese" and one of the most important figures in the European literary panorama of the fourteenth century. Some scholars (including Vittore Branca) define him as the greatest European prose writer of his time, a versatile writer who amalgamated different literary trends and genres, making them converge in original works, thanks to a creative activity exercised under the banner of experimentalism.

His most notable works are ''The Decameron

''The Decameron'' (; it, label= Italian, Decameron or ''Decamerone'' ), subtitled ''Prince Galehaut'' (Old it, Prencipe Galeotto, links=no ) and sometimes nicknamed ''l'Umana commedia'' ("the Human comedy", as it was Boccaccio that dubbed Da ...

'', a collection of short stories which in the following centuries was a determining element for the Italian literary tradition, especially after Pietro Bembo

Pietro Bembo, ( la, Petrus Bembus; 20 May 1470 – 18 January 1547) was an Italian scholar, poet, and literary theorist who also was a member of the Knights Hospitaller, and a cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church. As an intellectual of the ...

elevated the Boccaccian style to a model of Italian prose in the sixteenth century

The 16th century begins with the Julian year 1501 ( MDI) and ends with either the Julian or the Gregorian year 1600 ( MDC) (depending on the reckoning used; the Gregorian calendar introduced a lapse of 10 days in October 1582).

The 16th centur ...

, and '' On Famous Women''. He wrote his imaginative literature mostly in Tuscan vernacular

A vernacular or vernacular language is in contrast with a "standard language". It refers to the language or dialect that is spoken by people that are inhabiting a particular country or region. The vernacular is typically the native language, n ...

, as well as other works in Latin, and is particularly noted for his realistic dialogue which differed from that of his contemporaries, medieval writers who usually followed formulaic models for character and plot. The influence of Boccaccio's works was not limited to the Italian cultural scene but extended to the rest of Europe, exerting influence on authors such as Geoffrey Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer (; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for '' The Canterbury Tales''. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He w ...

, a key figure in English literature

English literature is literature written in the English language from United Kingdom, its crown dependencies, the Republic of Ireland, the United States, and the countries of the former British Empire. ''The Encyclopaedia Britannica'' defines E ...

, or later on Miguel de Cervantes

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra (; 29 September 1547 (assumed) – 22 April 1616 NS) was an Early Modern Spanish writer widely regarded as the greatest writer in the Spanish language and one of the world's pre-eminent novelists. He is best kno ...

, Lope de Vega

Félix Lope de Vega y Carpio ( , ; 25 November 156227 August 1635) was a Spanish playwright, poet, and novelist. He was one of the key figures in the Spanish Golden Age of Baroque literature. His reputation in the world of Spanish literatur ...

and the Spanish classical theater.

Boccaccio, together with Dante Alighieri

Dante Alighieri (; – 14 September 1321), probably baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri and often referred to as Dante (, ), was an Italian poet, writer and philosopher. His '' Divine Comedy'', originally called (modern Italian: ...

and Francesco Petrarca, is part of the so-called "Three Crowns" of Italian literature. He is remembered for being one of the precursors of humanism

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "human ...

, of which he helped lay the foundations in the city of Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico ...

, in conjunction with the activity of his friend and teacher Petrarch. He was the one who initiated Dante's criticism and philology: Boccaccio devoted himself to copying codices of the ''Divine Comedy

The ''Divine Comedy'' ( it, Divina Commedia ) is an Italian narrative poem by Dante Alighieri, begun 1308 and completed in around 1321, shortly before the author's death. It is widely considered the pre-eminent work in Italian literature a ...

'' and was a promoter of Dante's work and figure.

In the twentieth century, Boccaccio was the subject of critical-philological studies by Vittore Branca and Giuseppe Billanovich, and his ''Decameron'' was transposed to the big screen by the director and writer Pier Paolo Pasolini

Pier Paolo Pasolini (; 5 March 1922 – 2 November 1975) was an Italian poet, filmmaker, writer and intellectual who also distinguished himself as a journalist, novelist, translator, playwright, visual artist and actor. He is considered one of ...

.

Biography

Childhood and youth, 1313–1330

The details of Boccaccio's birth are uncertain. He was born in

The details of Boccaccio's birth are uncertain. He was born in Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico ...

or in a village near Certaldo where his family was from. He was the son of Florentine merchant Boccaccino di Chellino and an unknown woman; he was likely born out of wedlock. Boccaccio's stepmother was called Margherita de' Mardoli.

Boccaccio grew up in Florence. His father worked for the Compagnia dei Bardi The Compagnia dei Bardi was a Florentine banking and trading company which was started by the Bardi family, and which became one of the major medieval “super-companies” of the 14th Century.

History

The Bardi company was one of three major F ...

and, in the 1320s, married Margherita dei Mardoli, who was of a well-to-do family. Boccaccio may have been tutored by Giovanni Mazzuoli and received from him an early introduction to the works of Dante

Dante Alighieri (; – 14 September 1321), probably baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri and often referred to as Dante (, ), was an Italian poet, writer and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called (modern Italian: ' ...

. In 1326, his father was appointed head of a bank and moved with his family to Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adm ...

. Boccaccio was an apprentice at the bank but disliked the banking profession. He persuaded his father to let him study law at the '' Studium'' (the present-day University of Naples), where he studied canon law

Canon law (from grc, κανών, , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its members. It is t ...

for the next six years. He also pursued his interest in scientific and literary studies.

His father introduced him to the Neapolitan nobility and the French-influenced court of Robert the Wise (the king of Naples) in the 1330s. At this time, he fell in love with a married daughter of the king, who is portrayed as " Fiammetta" in many of Boccaccio's prose romances, including ''Il Filocolo'' (1338). Boccaccio became a friend of fellow Florentine Niccolò Acciaioli, and benefited from his influence as the administrator, and perhaps the lover, of Catherine of Valois-Courtenay, widow of Philip I of Taranto. Acciaioli later became counselor to Queen Joanna I of Naples

Joanna I, also known as Johanna I ( it, Giovanna I; December 1325 – 27 July 1382), was Queen of Naples, and Countess of Provence and Forcalquier from 1343 to 1382; she was also Princess of Achaea from 1373 to 1381.

Joanna was the eldest ...

and, eventually, her '' Grand Seneschal''.

It seems that Boccaccio enjoyed law no more than banking, but his studies allowed him the opportunity to study widely and make good contacts with fellow scholars. His early influences included Paolo da Perugia (a curator and author of a collection of myths called the ''Collectiones''), humanists Barbato da Sulmona and Giovanni Barrili, and theologian Dionigi di Borgo San Sepolcro

Dionigi di Borgo San Sepolcro OESA (Roberti of Roberti, Dennis) ( 1300 – 31 March 1342) was an Augustinian monk who was at one time Petrarch's confessor, and who taught Boccaccio at the beginning of his education in the humanities. He was ...

.

Adult years

In Naples, Boccaccio began what he considered his true vocation of poetry. Works produced in this period include '' Il Filostrato'' and ''

In Naples, Boccaccio began what he considered his true vocation of poetry. Works produced in this period include '' Il Filostrato'' and ''Teseida

''Teseida'' (full title: ''Teseida delle Nozze d’Emilia'', or ''The Theseid, Concerning the Nuptials of Emily'') is a long epic poem written by Giovanni Boccaccio c.1340–41. Running to almost 10,000 lines divided into twelve books, its notion ...

'' (the sources for Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer (; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for '' The Canterbury Tales''. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He w ...

's '' Troilus and Criseyde'' and ''The Knight's Tale

"The Knight's Tale" ( enm, The Knightes Tale) is the first tale from Geoffrey Chaucer's '' The Canterbury Tales''.

The Knight is described by Chaucer in the " General Prologue" as the person of highest social standing amongst the pilgrims, t ...

'', respectively), '' The Filocolo'' (a prose version of an existing French romance), and ''La caccia di Diana'' (a poem in '' terza rima'' listing Neapolitan women). The period featured considerable formal innovation, including possibly the introduction of the Sicilian octave

The Sicilian octave ( Italian: ''ottava siciliana'') is a verse form consisting of eight lines of eleven syllables each, called a hendecasyllable. The form is common in late medieval Italian poetry. In English poetry, iambic pentameter is often ...

, where it influenced Petrarch

Francesco Petrarca (; 20 July 1304 – 18/19 July 1374), commonly anglicized as Petrarch (), was a scholar and poet of early Renaissance Italy, and one of the earliest humanists.

Petrarch's rediscovery of Cicero's letters is often credited ...

.

Boccaccio returned to Florence in early 1341, avoiding the plague

Plague or The Plague may refer to:

Agriculture, fauna, and medicine

*Plague (disease), a disease caused by ''Yersinia pestis''

* An epidemic of infectious disease (medical or agricultural)

* A pandemic caused by such a disease

* A swarm of pes ...

of 1340 in that city, but also missing the visit of Petrarch to Naples in 1341. He had left Naples due to tensions between the Angevin king and Florence. His father had returned to Florence in 1338, where he had gone bankrupt. His mother died shortly afterward (possibly, as she was unknown – see above). Boccaccio continued to work, although dissatisfied with his return to Florence, producing ''Comedia delle ninfe fiorentine'' in 1341 (also known as ''Ameto''), a mix of prose and poems, completing the fifty-canto

The canto () is a principal form of division in medieval and modern long poetry.

Etymology and equivalent terms

The word ''canto'' is derived from the Italian word for "song" or "singing", which comes from the Latin ''cantus'', "song", from the ...

allegorical poem ''Amorosa visione'' in 1342, and '' Fiammetta'' in 1343. The pastoral piece "Ninfale fiesolano" probably dates from this time, also. In 1343, Boccaccio's father remarried to Bice del Bostichi. His other children by his first marriage had all died, but he had another son named Iacopo in 1344.

In Florence, the overthrow of Walter of Brienne brought about the government of ''popolo minuto'' ("small people", workers). It diminished the influence of the nobility and the wealthier merchant classes and assisted in the relative decline of Florence. The city was hurt further in 1348 by the

In Florence, the overthrow of Walter of Brienne brought about the government of ''popolo minuto'' ("small people", workers). It diminished the influence of the nobility and the wealthier merchant classes and assisted in the relative decline of Florence. The city was hurt further in 1348 by the Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

, which killed some three-quarters of the city's population, later represented in the ''Decameron''.

From 1347, Boccaccio spent much time in Ravenna, seeking new patronage and, despite his claims, it is not certain whether he was present in plague-ravaged Florence. His stepmother died during the epidemic and his father was closely associated with the government efforts as minister of supply in the city. His father died in 1349 and Boccaccio was forced into a more active role as head of the family.

Boccaccio began work on ''The Decameron

''The Decameron'' (; it, label= Italian, Decameron or ''Decamerone'' ), subtitled ''Prince Galehaut'' (Old it, Prencipe Galeotto, links=no ) and sometimes nicknamed ''l'Umana commedia'' ("the Human comedy", as it was Boccaccio that dubbed Da ...

'' around 1349. It is probable that the structures of many of the tales date from earlier in his career, but the choice of a hundred tales and the frame-story ''lieta brigata'' of three men and seven women dates from this time. The work was largely complete by 1352. It was Boccaccio's final effort in literature and one of his last works in Tuscan vernacular; the only other substantial work was ''Corbaccio

''Il Corbaccio'', or "The Crow", is an Italian literary work by Giovanni Boccaccio, traditionally dated c. 1355.Boccaccio, Giovanni. ''The Corbaccio''. Trans. and ed. Anthony K. Cassell, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1975.

Plot

The work is na ...

'' (dated to either 1355 or 1365). Boccaccio revised and rewrote ''The Decameron'' in 1370–1371. This manuscript has survived to the present day.

From 1350, Boccaccio became closely involved with Italian humanism (although less of a scholar) and also with the Florentine government. His first official mission was to Romagna

Romagna ( rgn, Rumâgna) is an Italian historical region that approximately corresponds to the south-eastern portion of present-day Emilia-Romagna, North Italy. Traditionally, it is limited by the Apennines to the south-west, the Adriatic to th ...

in late 1350. He revisited that city-state twice and also was sent to Brandenburg

Brandenburg (; nds, Brannenborg; dsb, Bramborska ) is a state in the northeast of Germany bordering the states of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Saxony, as well as the country of Poland. With an area of 29,480 squ ...

, Milan and Avignon

Avignon (, ; ; oc, Avinhon, label= Provençal or , ; la, Avenio) is the prefecture of the Vaucluse department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of Southeastern France. Located on the left bank of the river Rhône, the commune had ...

. He also pushed for the study of Greek, housing Barlaam of Calabria

Barlaam of Seminara (Bernardo Massari, as a layman), c. 1290–1348, or Barlaam of Calabria ( gr, Βαρλαὰμ Καλαβρός) was an Eastern Orthodox Greek scholar born in southern Italy he was a scholar and clergyman of the 14th century, ...

, and encouraging his tentative translations of works by Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

, Euripides

Euripides (; grc, Εὐριπίδης, Eurīpídēs, ; ) was a tragedian of classical Athens. Along with Aeschylus and Sophocles, he is one of the three ancient Greek tragedians for whom any plays have survived in full. Some ancient scholars ...

, and Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

. In these years, he also took minor orders.

In October 1350, he was delegated to greet Francesco Petrarch as he entered Florence and also to have Petrarch as a guest at Boccaccio's home, during his stay. The meeting between the two was extremely fruitful and they were friends from then on, Boccaccio calling Petrarch his teacher and ''magister''. Petrarch at that time encouraged Boccaccio to study classical Greek and Latin literature. They met again in Padua

Padua ( ; it, Padova ; vec, Pàdova) is a city and ''comune'' in Veneto, northern Italy. Padua is on the river Bacchiglione, west of Venice. It is the capital of the province of Padua. It is also the economic and communications hub of the ...

in 1351, Boccaccio on an official mission to invite Petrarch to take a chair at the university in Florence. Although unsuccessful, the discussions between the two were instrumental in Boccaccio writing the '' Genealogia deorum gentilium''; the first edition was completed in 1360 and this remained one of the key reference works on classical mythology for over 400 years. It served as an extended defense for the studies of ancient literature and thought. Despite the Pagan beliefs at its core, Boccaccio believed that much could be learned from antiquity. Thus, he challenged the arguments of clerical intellectuals who wanted to limit access to classical sources to prevent any moral harm to Christian readers. The revival of classical antiquity became a foundation of the Renaissance, and his defense of the importance of ancient literature was an essential requirement for its development. The discussions also formalized Boccaccio's poetic ideas. Certain sources also see a conversion of Boccaccio by Petrarch from the open humanist of the ''Decameron'' to a more ascetic style, closer to the dominant fourteenth century ethos. For example, he followed Petrarch (and Dante) in the unsuccessful championing of an archaic and deeply allusive form of Latin poetry. In 1359, following a meeting with Pope Innocent VI

Pope Innocent VI ( la, Innocentius VI; 1282 or 1295 – 12 September 1362), born Étienne Aubert, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 18 December 1352 to his death in September 1362. He was the fifth Avignon pope ...

and further meetings with Petrarch, it is probable that Boccaccio took some kind of religious mantle. There is a persistent (but unsupported) tale that he repudiated his earlier works as profane in 1362, including ''The Decameron''.

In 1360, Boccaccio began work on ''

In 1360, Boccaccio began work on ''De mulieribus claris

''De Mulieribus Claris'' or ''De Claris Mulieribus'' (Latin for "Concerning Famous Women") is a collection of biographies of historical and mythological women by the Florentine author Giovanni Boccaccio, composed in Latin prose in 1361–1362. ...

'', a book offering biographies of 106 famous women, that he completed in 1374.

A number of Boccaccio's close friends and other acquaintances were executed or exiled in the purge following the failed coup of 1361. It was in this year that Boccaccio left Florence to reside in Certaldo, although not directly linked to the conspiracy, where he became less involved in government affairs. He did not undertake further missions for Florence until 1365, and traveled to Naples and then on to Padua and Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

, where he met up with Petrarch in grand style at Palazzo Molina, Petrarch's residence as well as the place of Petrarch's library. He later returned to Certaldo. He met Petrarch only once again in Padua in 1368. Upon hearing of the death of Petrarch (19 July 1374), Boccaccio wrote a commemorative poem, including it in his collection of lyric poems, the ''Rime''.

He returned to work for the Florentine government in 1365, undertaking a mission to Pope Urban V. The papacy returned to Rome from Avignon

Avignon (, ; ; oc, Avinhon, label= Provençal or , ; la, Avenio) is the prefecture of the Vaucluse department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region of Southeastern France. Located on the left bank of the river Rhône, the commune had ...

in 1367, and Boccaccio was again sent to Urban, offering congratulations. He also undertook diplomatic missions to Venice and Naples.

Of his later works, the moralistic biographies gathered as ''De casibus virorum illustrium'' (1355–74) and ''De mulieribus claris'' (1361–1375) were most significant. Other works include a dictionary of geographical allusions in classical literature, ''De montibus, silvis, fontibus, lacubus, fluminibus, stagnis seu paludibus, et de nominibus maris liber''. He gave a series of lectures on Dante at the Santo Stefano church in 1373 and these resulted in his final major work, the detailed ''Esposizioni sopra la Commedia di Dante''. Boccaccio and Petrarch were also two of the most educated people in early Renaissance in the field of archaeology

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landsc ...

.

Boccaccio's change in writing style in the 1350s was due in part to meeting with Petrarch, but it was mostly due to poor health and a premature weakening of his physical strength. It also was due to disappointments in love. Some such disappointment could explain why Boccaccio came suddenly to write in a bitter ''Corbaccio'' style, having previously written mostly in praise of women and love, though elements of misogyny are present in ''Il Teseida''. Petrarch describes how Pietro Petrone (a Carthusian

The Carthusians, also known as the Order of Carthusians ( la, Ordo Cartusiensis), are a Latin enclosed religious order of the Catholic Church. The order was founded by Bruno of Cologne in 1084 and includes both monks and nuns. The order has i ...

monk) on his death bed in 1362 sent another Carthusian (Gioacchino Ciani) to urge him to renounce his worldly studies. Petrarch then dissuaded Boccaccio from burning his own works and selling off his personal library, letters, books, and manuscripts. Petrarch even offered to purchase Boccaccio's library, so that it would become part of Petrarch's library. However, upon Boccaccio's death, his entire collection was given to the monastery of Santo Spirito, in Florence, where it still resides.

His final years were troubled by illnesses, some relating to obesity and what often is described as dropsy

Edema, also spelled oedema, and also known as fluid retention, dropsy, hydropsy and swelling, is the build-up of fluid in the body's tissue. Most commonly, the legs or arms are affected. Symptoms may include skin which feels tight, the area ma ...

, severe edema that would be described today as congestive heart failure

Heart failure (HF), also known as congestive heart failure (CHF), is a syndrome, a group of signs and symptoms caused by an impairment of the heart's blood pumping function. Symptoms typically include shortness of breath, excessive fatigue, ...

. He died on 21 December 1375 in Certaldo, where he is buried.

Works

;Alphabetical listing of selected works: *'' Amorosa visione'' (1342) *'' Buccolicum carmen'' (1367–1369) *'' Caccia di Diana'' (1334–1337) *'' Comedia delle ninfe fiorentine'' (''Ninfale d'Ameto'', 1341–1342) *''Corbaccio

''Il Corbaccio'', or "The Crow", is an Italian literary work by Giovanni Boccaccio, traditionally dated c. 1355.Boccaccio, Giovanni. ''The Corbaccio''. Trans. and ed. Anthony K. Cassell, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1975.

Plot

The work is na ...

'' (around 1365, this date is disputed)

*'' De Canaria'' (within 1341–1345)

*'' De Casibus Virorum Illustrium'' (). Facsimile of 1620 Paris ed., 1962, Scholars' Facsimiles & Reprints, .

*''De mulieribus claris

''De Mulieribus Claris'' or ''De Claris Mulieribus'' (Latin for "Concerning Famous Women") is a collection of biographies of historical and mythological women by the Florentine author Giovanni Boccaccio, composed in Latin prose in 1361–1362. ...

'' (1361, revised up to 1375)

*''The Decameron

''The Decameron'' (; it, label= Italian, Decameron or ''Decamerone'' ), subtitled ''Prince Galehaut'' (Old it, Prencipe Galeotto, links=no ) and sometimes nicknamed ''l'Umana commedia'' ("the Human comedy", as it was Boccaccio that dubbed Da ...

'' (1349–52, revised 1370–1371)

*'' Elegia di Madonna Fiammetta'' (1343–1344)

*'' Esposizioni sopra la Comedia di Dante'' (1373–1374)

*'' Filocolo'' (1336–1339)

*'' Filostrato'' (1335 or 1340)

*'' Genealogia deorum gentilium libri'' (1360, revised up to 1374)

*'' Ninfale fiesolano'' (within 1344–46, this date is disputed)

*''Rime

Rime may refer to:

*Rime ice, ice that forms when water droplets in fog freeze to the outer surfaces of objects, such as trees

Rime is also an alternative spelling of "rhyme" as a noun:

*Syllable rime, term used in the study of phonology in ling ...

'' (finished 1374)

*'' Teseida delle nozze di Emilia'' (before 1341)

*'' Trattatello in laude di Dante'' (1357, title revised to ''De origine vita studiis et moribus viri clarissimi Dantis Aligerii florentini poetae illustris et de operibus compositis ab eodem'')

*''Zibaldone Magliabechiano

Giovanni Boccaccio's notebooks or '' zibaldoni'' have been preserved in three codices, known as the ''Zibaldone Laurenziano'', the ''Miscellanea Laurenziana'' and the ''Zibaldone Magliabechiano''. These are autograph manuscripts containing both ...

'' (within 1351–1356)

See Consoli's bibliography for an exhaustive listing.Consoli, Joseph P. (1992) ''Giovanni Boccaccio: an Annotated Bibliography''. New York: Garland. .

See also

*Influence of Italian humanism on Chaucer

Contact between Geoffrey Chaucer and the Italian humanists Petrarch or Boccaccio has been proposed by scholars for centuries.Thomas Warton, ''The history of English poetry, from the close of the eleventh to the commencement of the eighteenth c ...

Notes

Citations

Sources

* * * * * Çoban, R. V. (2020). The Manzikert Battle and Sultan Alp Arslan with European Perspective in the 15st Century in the Miniatures of Giovanni Boccaccio's "De Casibus Virorum Illustrium"s 226 and 232. French Manuscripts in Bibliothèque Nationale de France. S. Karakaya ve V. Baydar (Ed.), in 2nd International Muş Symposium Articles Book (pp. 48–64). Muş: Muş Alparslan UniversitySource

* Patrick, James A.(2007). ''Renaissance And Reformation''. Marshall Cavendish Corp. .

Further reading

* ''On Famous Women'', edited and translated by Virginia Brown. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001 (Latin text and English translation) * ''The Decameron'', * ''The Life of Dante'', translated by Vincenzo Zin Bollettino. New York: Garland, 1990 * ''The Elegy of Lady Fiammetta'', edited and translated rom the Italianby Mariangela Causa-Steindler and Thomas Mauch; with an introduction by Mariangela Causa-Steindler. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990 .External links

* * * * * *De claris mulieribus

From th

Rare Book and Special Collections Division

at the

Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It is the oldest federal cultural institution in the country. The libra ...

Genealogie deorum gentilium Johannis Boccacii de Certaldo liber

a

Somni

De mulieribus claris

a

Somni

{{DEFAULTSORT:Boccaccio, Giovanni 1313 births 1375 deaths People from Certaldo Italian Renaissance humanists Italian Renaissance writers Italian male poets Italian Roman Catholics Medieval Italian diplomats Medieval Latin poets 14th-century people of the Republic of Florence 14th-century Italian historians 14th-century Italian poets 14th-century Latin writers 14th-century diplomats Deaths from edema