Benjamin H. Bristow on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Benjamin Helm Bristow (June 20, 1832 – June 22, 1896) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 30th U.S. Treasury Secretary and the first

Benjamin Bristow

/ref> Solicitor General Bristow advocated for African American citizens in Kentucky to be allowed to testify in a white man's court case. He also advocated education for all races to be paid for by public funding. A native of Kentucky, Bristow was the son of a prominent Whig Unionist and attorney. Having graduated from Jefferson College in Pennsylvania in 1851, Bristow studied law and passed the bar in 1853, working as an attorney until the outbreak of the

Benjamin Helm Bristow was born in Edwards Hall on June 20, 1832, in Elkton, Kentucky,

Benjamin Helm Bristow was born in Edwards Hall on June 20, 1832, in Elkton, Kentucky,

In December 1860, after

In December 1860, after

In 1870, Congress created the

In 1870, Congress created the

Bristow called Delano a "very mean dog".

Political journalist, George W. Fishback, owner of the ''St. Louis Democrat'' advised Bristow and Wilson, on how to expose the ring and to bypass any corrupt federal appointees who would tip other ring partners of a federal investigation. Washington correspondent, Henry V. Boynton, also aided Bristow and Wilson in their investigation. Monitored by Wilson, incorruptible investigative agents, that included Yaryan, obtained a vast supply of evidence in

Political journalist, George W. Fishback, owner of the ''St. Louis Democrat'' advised Bristow and Wilson, on how to expose the ring and to bypass any corrupt federal appointees who would tip other ring partners of a federal investigation. Washington correspondent, Henry V. Boynton, also aided Bristow and Wilson in their investigation. Monitored by Wilson, incorruptible investigative agents, that included Yaryan, obtained a vast supply of evidence in

Bristow was upset over not winning the Republican presidential nomination and over the rumor he had been disloyal to President Grant. Bristow retired from politics, never again to run for political office. After 1878, he practiced law in

Bristow was upset over not winning the Republican presidential nomination and over the rumor he had been disloyal to President Grant. Bristow retired from politics, never again to run for political office. After 1878, he practiced law in

Solicitor General

A solicitor general is a government official who serves as the chief representative of the government in courtroom proceedings. In systems based on the English common law that have an attorney general or equivalent position, the solicitor general ...

.

A Union military officer, Bristow was a Republican Party reformer and civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' political freedom, freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and ...

advocate. During his tenure as Secretary of the Treasury, he is primarily known for breaking up and prosecuting the Whiskey Ring

The Whiskey Ring took place from 1871 to 1876 centering in St. Louis during the presidency of Ulysses S. Grant. The ring was an American scandal, broken in May 1875, involving the diversion of tax revenues in a conspiracy among government agent ...

at the behest of President Grant, a corrupt tax evasion profiteering ring that depleted the national treasury. Additionally, Bristow promoted gold standard

A gold standard is a backed currency, monetary system in which the standard economics, economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the ...

currency rather than paper money

Paper money, often referred to as a note or a bill (North American English), is a type of negotiable promissory note that is payable to the bearer on demand, making it a form of currency. The main types of paper money are government notes, which ...

. Bristow was one of Grant's most popular Cabinet members among reformers. Bristow supported Grant's Resumption of Specie Act of 1875, that helped stabilize the economy during the Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the "L ...

. As the United States' first solicitor general, Bristow aided President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

and Attorney General Amos T. Akerman

Amos Tappan Akerman (February 23, 1821 – December 21, 1880) was an American politician who served as United States Attorney General under President Ulysses S. Grant from 1870 to 1871.

A native of New Hampshire, Akerman graduated from Dartmou ...

's vigorous and thorough prosecution and destruction of the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to KKK or Klan, is an American Protestant-led Christian terrorism, Christian extremist, white supremacist, Right-wing terrorism, far-right hate group. It was founded in 1865 during Reconstruction era, ...

in the Reconstructed South.Department of JusticeBenjamin Bristow

/ref> Solicitor General Bristow advocated for African American citizens in Kentucky to be allowed to testify in a white man's court case. He also advocated education for all races to be paid for by public funding. A native of Kentucky, Bristow was the son of a prominent Whig Unionist and attorney. Having graduated from Jefferson College in Pennsylvania in 1851, Bristow studied law and passed the bar in 1853, working as an attorney until the outbreak of the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

in 1861. Fighting for the Union, Bristow served in the army during the American Civil War and was promoted to colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

. Wounded at the Battle of Shiloh

The Battle of Shiloh, also known as the Battle of Pittsburg Landing, was a major battle in the American Civil War fought on April 6–7, 1862. The fighting took place in southwestern Tennessee, which was part of the war's Western Theater of the ...

, Bristow recuperated and was promoted to lieutenant colonel. In 1863, Bristow was elected Kentucky state Senator, serving only one term. At the end of the Civil War, Bristow was appointed assistant to the U.S. District Attorney serving in the Louisville

Louisville is the most populous city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky, sixth-most populous city in the Southeast, and the 27th-most-populous city in the United States. By land area, it is the country's 24th-largest city; however, by populatio ...

area. In 1866, Bristow was appointed U.S. District attorney, serving in the Louisville area.

In 1870, Bristow was appointed the United States' first U.S. Solicitor General, who aided the U.S. Attorney General by arguing cases before the U.S. Supreme Court. In 1874, Bristow was appointed U.S. Secretary of the Treasury by President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

. Initially Grant gave Bristow his full support during Bristow's popular prosecution of the Whiskey Ring

The Whiskey Ring took place from 1871 to 1876 centering in St. Louis during the presidency of Ulysses S. Grant. The ring was an American scandal, broken in May 1875, involving the diversion of tax revenues in a conspiracy among government agent ...

. However, when Bristow and Grant's Attorney General Edwards Pierrepont, another reforming Cabinet member, uncovered that Orville Babcock, Grant's personal secretary, was involved in the ring, Grant's relationship with Bristow cooled. In June 1876, due to friction over Bristow's zealous prosecution of the Whiskey Ring and rumor that Bristow was interested in running for the U.S. presidency, Bristow resigned from President Grant's Cabinet on his 44th birthday. During the 1876 United States presidential election

United States presidential election, Presidential elections were held in the United States on November 7, 1876. Republican Party (United States), Republican Governor Rutherford B. Hayes of Ohio very narrowly defeated Democratic Party (United Sta ...

, Bristow made an unsuccessful attempt at gaining the Republican presidential ticket, running as a Republican reformer. The Republicans, however, chose Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was the 19th president of the United States, serving from 1877 to 1881.

Hayes served as Cincinnati's city solicitor from 1858 to 1861. He was a staunch Abolitionism in the Un ...

. After the 1876 presidential election, Bristow returned to private practice in New York. He formed a successful law practice in 1878, often arguing cases before the U.S. Supreme Court until his death in 1896.

Bristow was credited, by historian Jean Edward Smith, as one of Grant's best cabinet choices. Reformers were generally pleased by Secretary Bristow's overall prosecution of the Whiskey Ring, and looked to him for cleaning up government corruption. Historians have also given credit for Bristow, America's first Solicitor General, for prosecuting the Ku Klux Klan. Bristow, however, had an ambitious, contentious nature, and at times this led to various feuds with Grant cabinet members. Bristow, a native of Kentucky, represented the Southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, Dixieland, or simply the South) is List of regions of the United States, census regions defined by the United States Cens ...

on Grant's cabinet, during Grant's second term.

Early life

Benjamin Helm Bristow was born in Edwards Hall on June 20, 1832, in Elkton, Kentucky,

Benjamin Helm Bristow was born in Edwards Hall on June 20, 1832, in Elkton, Kentucky, United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

.Boone, George Street. '. National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an List of federal agencies in the United States, agency of the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government, within the US Department of the Interior. The service manages all List ...

, 1973-07-10, 3. Bristow was the son of Francis M. Bristow and his wife Emily Helm. This work in turn cites:

*

* ''Whiskey Frauds'', 44th Congress, 1st Session, Mis. Doc. No. 186.

* McDonald, John, ''Secrets of the Great Whiskey Ring'', Chicago, 1880. A book by one concerned and to be considered in that light: John McDonald was supervisor of internal revenue at St Louis for nearly six years. Francis was a prominent lawyer and Whig member of Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

in 1854–1855 and 1859–1861. Edwards Hall was the home of his late grandfather, Benjamin Edwards. Bristow graduated at Jefferson College, Washington, Pennsylvania

Washington, also known as Little Washington to distinguish it from the District of Columbia, is a city in Washington County, Pennsylvania, United States, and its county seat. The population was 13,176 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 censu ...

, in 1851, studied law under his father, and was admitted to the Kentucky bar in 1853. For a while Bristow worked as a law partner for his father. His father later became a strong anti-slavery Unionist. His father's political anti-slavery and Whig views strongly influenced Bristow's own political outlook.

Marriage and family

On November 21, 1854, aged 22, Bristow married Abbie S. Briscoe. Benjamin and Abbie had two children one son, William A. Bristow, and one daughter Nannie Bristow. William was an attorney who worked in Bristow's New York law firm ''Bristow, Opdyke, & Willcox''. In June 1896 William was in London recovering from typhoid fever. Nannie married Eben S. Sumner a Massachusetts textile businessman and politician.Kentucky law practice (1858–1861)

In 1858, Bristow and his wife Abbie moved toHopkinsville

Hopkinsville is a home rule-class city in and the county seat of Christian County, Kentucky, United States. The population at the 2020 census was 31,180.

History

Early years

The area of present-day Hopkinsville was initially claimed in 1796 ...

, Kentucky

Kentucky (, ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north, West Virginia to the ...

. Bristow practiced law until the outbreak of the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

.

American Civil War (1861–1863)

In December 1860, after

In December 1860, after Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

was elected, the South seceded from the Union and formed the Confederacy (''1861''), primarily to protect the institution of slavery, profitable cotton plantations, and resistance to black integration and citizenship. President James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was the 15th president of the United States, serving from 1857 to 1861. He also served as the United States Secretary of State, secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and represented Pennsylvan ...

, sympathetic to the South, did virtually nothing to contain Southern secession, prior to Lincoln's March 4, 1861, Inauguration. At the beginning of the Civil War in 1861, Bristow, an ardent Unionist, joined the Union Army, and mustered the 25th Kentucky Infantry . On September 21, 1861, Bristow was appointed lieutenant colonel of the 25th Kentucky Infantry. Bristow fought under General Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

and served bravely at three battles, Fort Henry, Fort Donelson, and Shiloh, at the latter he was injured.

In April 1862, General Grant and most of his Union Army were encamped at Pittsburg Landing, and had planned to attack Corinth, a Confederate stronghold. The Confederates, however attacked in full force, that surprised Grant's unentrenched Union Army. Grant and his men were able to hold off the Confederate Army, although one Union division was captured. The next day, after Grant received reinforcements, the Union Army attacked the Confederates in full force and pushed the Southern Army back to Corinth. At this two day Battle of Shiloh

The Battle of Shiloh, also known as the Battle of Pittsburg Landing, was a major battle in the American Civil War fought on April 6–7, 1862. The fighting took place in southwestern Tennessee, which was part of the war's Western Theater of the ...

in Tennessee, Bristow was severely wounded by an exploding shell over his head and temporarily forced to retire from field duty in order to recover from his injury. The force and noise of the explosion left Bristow deaf and unconscious, unable to command. Bristow was replaced by Major William B. Wall. After his recuperation, Bristow returned to field service during the summer of 1862 and helped recruit the 8th Kentucky Cavalry.

On September 8, 1862, Bristow was commissioned lieutenant colonel over the 8th Kentucky Cavalry. Bristow assumed command of the 8th Kentucky Cavalry in January 1863 after Col. James M. Shackleford, the previous commander, was promoted brigadier general. On April 1, 1863, Bristow was promoted to colonel and continued his command over the 8th Kentucky Cavalry. In July 1863 Col. Bristow and the Kentucky 8th Cavalry assisted in the capture of John Hunt Morgan during his July 1863 raid through Indiana and Ohio.

Kentucky state senator (1863–1865)

Bristow was honorably discharged from service in the Union Army on September 23, 1863, having been elected to the sixth district of theKentucky Senate

The Kentucky Senate is the upper house of the Kentucky General Assembly. The Kentucky Senate is composed of 38 members elected from single-member districts throughout Kentucky, the Commonwealth. There are no term limits for Kentucky senators. T ...

, which comprised Christian and Todd Counties. Bristow had not known he had been elected to the senate; he later resigned from the body in 1865 before the expiration of his four-year term. Bristow supported all Union war effort legislation, the presidential election of Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

in 1864, and the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment that outlawed slavery.

U.S. District Attorney (1866–1870)

In 1865, Bristow was appointed assistant to theUnited States Attorney

United States attorneys are officials of the U.S. Department of Justice who serve as the chief federal law enforcement officers in each of the 94 U.S. federal judicial districts. Each U.S. attorney serves as the United States' chief federal ...

. In 1866, Bristow was appointed district attorney for the Louisville, Kentucky district. As district attorney, he was renowned for his vigor in enforcing the 1866 U.S. Civil Rights Act. Bristow served as district attorney until 1870 and spent a few months practicing law in partnership with future United States Supreme Court Justice John Harlan.

First U.S. Solicitor General (1870–1872)

Prosecuted Ku Klux Klan

In 1870, Congress created the

In 1870, Congress created the U.S. Department of Justice

The United States Department of Justice (DOJ), also known as the Justice Department, is a federal executive department of the U.S. government that oversees the domestic enforcement of federal laws and the administration of justice. It is equi ...

, in part, to aid in the enforcement of U.S. Congressional Reconstruction laws and U.S. Constitutional amendments. On October 4, 1870, Bristow was appointed the first incumbent U.S. Solicitor General by President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

and served until November 12, 1872, having resigned the office. Bristow and U.S. Attorney General Amos Akerman prosecuted thousands of Klansmen

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to KKK or Klan, is an American Protestant-led Christian extremist, white supremacist, far-right hate group. It was founded in 1865 during Reconstruction in the devastated South. Various historians hav ...

that resulted in a brief two-year quiet period during the turbulent Reconstruction Era

The Reconstruction era was a period in History of the United States, US history that followed the American Civil War (1861-65) and was dominated by the legal, social, and political challenges of the Abolitionism in the United States, abol ...

in the South. In 1873 President Grant nominated him Attorney General of the United States

The United States attorney general is the head of the United States Department of Justice and serves as the chief law enforcement officer of the federal government. The attorney general acts as the principal legal advisor to the president of the ...

in case then Attorney General George H. Williams was confirmed as Chief Justice of the United States

The chief justice of the United States is the chief judge of the Supreme Court of the United States and is the highest-ranking officer of the U.S. federal judiciary. Appointments Clause, Article II, Section 2, Clause 2 of the U.S. Constitution g ...

, a contingency which did not arise.

Feud with Akerman

On the verge of prosecuting theKu Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to KKK or Klan, is an American Protestant-led Christian terrorism, Christian extremist, white supremacist, Right-wing terrorism, far-right hate group. It was founded in 1865 during Reconstruction era, ...

in mid-September 1871, Bristow in Washington launched a treacherous attack on his boss Akerman's reputation, while Akerman was fighting lawlessness in the South. After Grant returned from a trip to Dayton, Ohio, Bristow, wanting Akerman's cabinet post, told Grant that Akerman was "too small" for the job of Attorney General and he was not respected "by the Court & the profession generally". Bristow went so far as to call Akerman a "dead weight on the administration". Grant was shocked at Bristow's view of Akerman and surprised that Bristow had prodded Grant to get him fired by Grant. Grant refused to consider firing Akerman, telling Bristow that Akerman was thoroughly honest and an earnest man. Grant kept Akerman on the cabinet while Bristow retained his job of Solicitor General.

Civil rights speech

In 1871, Bristow traveled to his native Kentucky state and in a speech advocatedAfrican American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from an ...

civil rights. Bristow advocated that blacks be given the right to testify in juries. At this time Kentucky

Kentucky (, ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north, West Virginia to the ...

law forbade the 225,000 black U.S. citizens from testifying in any civil or criminal case involving a white man. He stated the Kentucky law that denied African Americans the right to testify in a white man's case had roots in slavery and was a "monstrous and grievous wrong to both races." Bristow stated that the Ku Klux Klan Act

The Enforcement Act of 1871 (), also known as the Ku Klux Klan Act, Third Enforcement Act, Third Ku Klux Klan Act, Civil Rights Act of 1871, or Force Act of 1871, is an Act of the United States Congress that was intended to combat the paramilit ...

and the previous Civil Rights acts passed by the U.S. Congress were designed to protect the "humblest citizens" from lawbreakers. Bristow stated he would "tax the rich man's property to educate his poor neighbor's child", and he would "tax the white man's property to educate the black man's child." Bristow advocated free universal education and all property in Kentucky be taxed to pay for schools.New York Times (June 16, 1876), ''Nomination of Benjamin H. Bristow''

Secretary of the Treasury (1874–1876)

On June 3, 1874, President Grant appointed BristowSecretary of the Treasury

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

after William A. Richardson was removed in light of the Sanborn incident that involved Treasury contract scandals. Bristow was hailed by the press as a much needed reformer. Bristow took control of the Treasury during the Long Depression

The Long Depression was a worldwide price and economic recession, beginning in Panic of 1873, 1873 and running either through March 1879, or 1899, depending on the metrics used. It was most severe in Europe and the United States, which had been e ...

, that was started by the Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the "L ...

. The Republican Party at this time was divided over currency. Bristow supported the hard money North Eastern Republicans and favored a resumption of species (coin money) to replace greenbacks (paper money). President Grant had vetoed the ''Inflation Bill'', on April 22, that would have increased paper money into the collapsed economy. Bristow's support of Grant's veto helped him get nominated for the Treasury by Grant. Sixteen days after Bristow took office, on June 20, Bristow's 42nd birthday, Grant signed a compromise act that legalized $26 million greenbacks released by previous Treasury Secretary Richardson, allowed a maximum of $382 million greenbacks, and authorized a redistribution of $55 million national banknotes. The act had little affect to alleve the devastated economy.

Internal reforms made

Fulfilling the press's reformer expectation, Bristow immediately went to work. He drastically reorganized the Treasury Department, abolished the corrupt office of supervising architect made famous by Alfred B. Mullett, and dismissed the second-comptroller and his subordinates for inefficiency. Bristow shook up the detective force and consolidated collection districts in theCustoms

Customs is an authority or Government agency, agency in a country responsible for collecting tariffs and for controlling International trade, the flow of goods, including animals, transports, personal effects, and hazardous items, into and out ...

and Internal Revenue Service

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) is the revenue service for the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government, which is responsible for collecting Taxation in the United States, U.S. federal taxes and administerin ...

s. He dismissed over 700 people and implemented civil service rules in the Treasury Department.

Feud with Robeson

Within a few months after Grant appointed Bristow to run the Treasury, Bristow developed a feud with Grant's appointed Secretary of Navy George M. Robeson. The controversy centered around Robeson wanting to have Senator A.G. Cattell appointed financial agent in London to negotiate a bond issue. Cattell had performed a similar service in 1873 under previous Secretary Richardson. Bristow refused to make the appointment and believed a Treasury appointee could do the job. Bristow lobbied Grant to appoint John Bigelow, head of the Treasury Department's Loan Division. Grant accepted Bristow's choice of Bigelow, but he warned Bristow that Bigelow had a previous episode of drunkness. Bristow went further to undercut Robeson's influence in the Grant cabinet. Bristow told Grant that Robeson's Navy Department was financially mismanaged, and was under the control of former treasury secretary Hugh McCulloch's banking house. Bristow's advisers told Bristow to cool things off, and take a less confrontational approach.Feud with Williams

Grant's appointed Attorney General George Williams position on the cabinet was not secure, after Williams nomination was withdrawn by Grant for Supreme Court Justice. His personal reputation and that of his wife, Kate Williams, was under public scrutiny. To defend her husband and herself, Kate sent out anonymous letters to slander Grant's cabinet, and others, including alleging sexual misconduct. Cabinet members who had received letters included Secretary of War William Belknap and Secretary of Navy George M. Robeson. Treasury department solicitor, Bluford Wilson, hired H.C. Whitely to investigate Kate and the letters. Wilson, Belknap, and Robeson agreed that Williams had to go. Bristow, supporting Wilson, urged Grant to fire Williams. Secretary of State Hamilton Fish told Grant that Kate had received a bribe of $30,000 from ''Pratt & Boyd'' for the Justice Department to drop a case against the company. Grant finally fired Williams, and replaced him with New York reformer Edwards Pierrepont, who cleaned up the Department of Justice.Feud with Delano

150px, Columbus DelanoBristow called Delano a "very mean dog".

Columbus Delano

Columbus Delano (June 4, 1809 – October 23, 1896) was an American lawyer, rancher, banker, statesman, and a member of the prominent Delano family. Forced to live on his own at an early age, Delano struggled to become a self-made man. Delano ...

was Grant's Secretary of Interior, who allowed corruption in the vast Interior Department. Bristow, a reformer, wanted Delano out of office, believing Delano's departure would establish integrity in the Republican Party. Also, Bristow believed Delano was plotting to remove Bristow from the Interior. Bristow called Delano a "very mean dog" and said Delano deserved the "execration of every honest man." Bristow hired Frank Wolcott to investigate Delano's department, that was ripe with corruption. Wolcott discovered that surveyor general of Wyoming, Silas Reed, had been making contracts with corrupt surveyors who shared enormous profits with silent-partners.

One of those silent-partners was Delano's son John, who had no survey training or work experience. Wolcott sent Bristow damaging evidence against Delano, while Bristow shrewdly turned the documents over to Grant. Although the silent-partner contracts were technically legal, the scandal would embolden the Democrats. By April 1875, Delano had to go, but Grant delayed his resignation for several months. Delano fought back, by revealing information that other cabinet officers wanted Delano to stay in office, in addition to having made a false charge against Bristow. In October 1875, Grant finally replaced Delano with reformer Zachariah Chandler, who cleaned up corruption in the Interior Department.

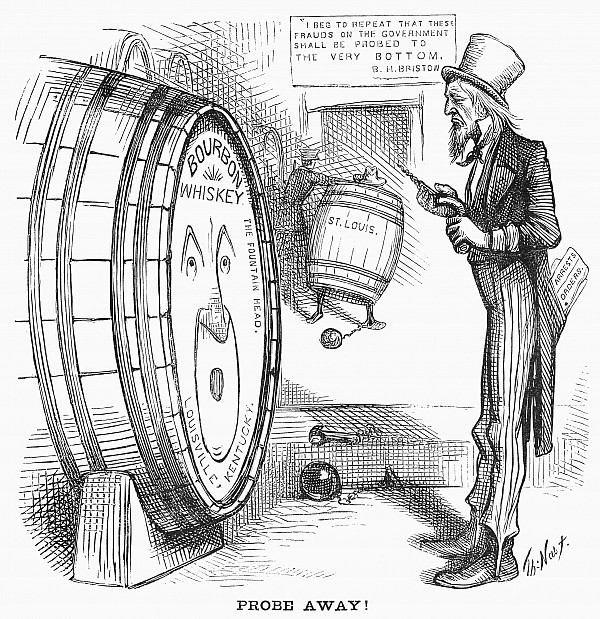

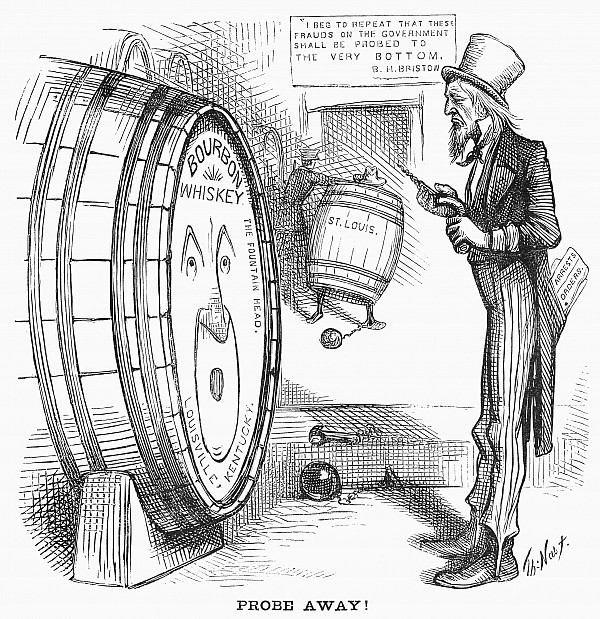

Broke the Whiskey Ring

In the Spring of 1875, Bristow began an anti-corruption campaign that would put him in the national spotlight. Bristow's greatest work in the Treasury Department came in prosecution and break up of the notoriousWhiskey Ring

The Whiskey Ring took place from 1871 to 1876 centering in St. Louis during the presidency of Ulysses S. Grant. The ring was an American scandal, broken in May 1875, involving the diversion of tax revenues in a conspiracy among government agent ...

headquartered in St. Louis

St. Louis ( , sometimes referred to as St. Louis City, Saint Louis or STL) is an independent city in the U.S. state of Missouri. It lies near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a populatio ...

The Whiskey Ring was powerful and corrupt machine started by western distillers and their allies in the Internal Revenue Service; it profiteered by evading the collection of taxes on whiskey production. Distillers tended to bribe revenue agents, rather than pay excessive levies on alcohol. Past efforts to uncover the Whiskey Ring were unsuccessful, because ring members in Washington D.C. alerted other ring members of pending investigations. A November 1872 investigation, by three revenue investigators, into St. Louis distilleries, had found significant irregularities, but one agent who was bribed, submitted a whitewashed version of corruption. Despite Washington rumors of its existence, the ring seemed to be impregnable to prosecution.

Investigation

In the Fall of 1874 Bristow received a $125,000 (~$ in ) appropriation from Congress to investigate the Whiskey Ring. In December 1874, Bristow convinced Internal Revenue Supervisor J.W. Douglas to send a new investigation team, but Grant's private Secretary at the White House, Orville E. Babcock, convinced Douglas to revoke his order. An effort to transfer revenue supervisors, proposed by Douglas, to new locations, to dismantle the ring, was defeated when, out of political objection, Grant suspended the order on February 4, 1875. Grant desired to "detect frauds" that had already been committed by the Whiskey Ring, rather than transfer the supervisors. Bristow, and Grant appointed Treasury Solicitor Bluford Wilson, lost faith in Douglas' willingness to go after the ring, and launched a covert investigation by independent undercover investigators, suggested by revenue agent Homer Yaryan. Political journalist, George W. Fishback, owner of the ''St. Louis Democrat'' advised Bristow and Wilson, on how to expose the ring and to bypass any corrupt federal appointees who would tip other ring partners of a federal investigation. Washington correspondent, Henry V. Boynton, also aided Bristow and Wilson in their investigation. Monitored by Wilson, incorruptible investigative agents, that included Yaryan, obtained a vast supply of evidence in

Political journalist, George W. Fishback, owner of the ''St. Louis Democrat'' advised Bristow and Wilson, on how to expose the ring and to bypass any corrupt federal appointees who would tip other ring partners of a federal investigation. Washington correspondent, Henry V. Boynton, also aided Bristow and Wilson in their investigation. Monitored by Wilson, incorruptible investigative agents, that included Yaryan, obtained a vast supply of evidence in St. Louis

St. Louis ( , sometimes referred to as St. Louis City, Saint Louis or STL) is an independent city in the U.S. state of Missouri. It lies near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a populatio ...

of frauds committed by the ring. Bristow, in order to secure the enormity of the Whiskey Ring corruption, audited railroad and steamboat cargo receipts for accurate figures of the shipment of liquor in St. Louis and other key cities. To keep the investigation secret from the ring, Bristow gave the agents a cipher different from the Treasury code, while messages were relayed through Fishback and Boynton. Similar investigative work was done in Chicago

Chicago is the List of municipalities in Illinois, most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of Unite ...

and Milwaukee

Milwaukee is the List of cities in Wisconsin, most populous city in the U.S. state of Wisconsin. Located on the western shore of Lake Michigan, it is the List of United States cities by population, 31st-most populous city in the United States ...

. Evidence of fraudulent activity was quickly obtained, into a profiteering scheme, that involved corrupt distillers and revenue agents. To escape taxes, the Whiskey Ring shipped whiskey labelled vinegar, listed whiskey at a lower proof, or illegally used revenue stamps multiple times. As a result, millions of dollars were depleted from the treasury in tax revenues.

Bristow's investigation revealed that Grant appointment, General John McDonald, St. Louis Collector of Internal Revenue, who controlled seven states, was the ring leader. In April 1875, McDonald was called to Bristow's Washington office and confronted by Bristow and showed massive evidence against McDonald, who confessed to being the ring leader. However, after McDonald left Bristow's office, knowing he would be indicted, he unsuccessfully asked Wilson for indemnity from prosecution, and that the corrupt distilleries not be raided. McDonald pleaded that prosecution of the Whiskey Ring would hurt the Republican Party in Missouri. Wilson said later that he would have had McDonald fired on the spot, had he had the authority to do so.

Prosecution

On May 7, 1875, Bristow gave Grant the investigation findings of corruption by the Whiskey Ring and stressed the need for immediate prosecution. Without hesitation Grant gave Bristow permission to go after the ring, and told Bristow to move relentlessly against all those who were culpable. Three days later, on May 10, Bristow struck hard shattering the ring at one blow. Treasury agents raided and shut down distilleries, rectifying houses, and bottling plants in St. Louis, Chicago, Milwaukee, and six other Mid-Western states. Internal Revenue offices were placed under custody of the Treasury, while thirty-two installations were taken over. Books, papers, and tax receipts were confiscated, that proved and identified individual ring members guilt. Overwhelming evidence against the ring was collected, while federal grand juries produced over 350 indictments. A Republican Party patronage boss in Wisconsin was linked to corruption found in Milwaukee. Evidence suggested almost every Republican office holder in Chicago profited from illegal distilling. St. Louis proved to be the kingpin city of the Whiskey Ring. In the past six months, $1,650,000 in taxes was evaded, while over two years the tax evasion number reached $4,000,000. Bristow instituted almost 250 federal civil and criminal lawsuits against ring members, and within a year, Bristow, recovered $3,150,000 in unpaid taxes, and obtained 110 convictions on 176 indicted ring members. Chief clerk of the Treasury, Willam Avery, St. Louis revenue collector General John McDonald, and St. Louis deputy collector, John A. Joyce, were indicted and convicted.Babcock's St. Louis trial

Bristow's investigation extended into the White House, as evidence suggested Grant's private Secretary, Orville E. Babcock, was a secret and paid informer of the Whiskey Ring. Bristow found two incriminating and cryptic letters signed "Sylph", believed to have been Babcock's handwriting. The first was dated December 10, 1874, that said, "''I have succeeded. They will not go. I will write you.''" The other letter was dated February 3, 1875, that said, "''We have official information that the enemy weakens. Push things.''" In October 1875, Bristow brought the two letters to Grant's cabinet meeting. Babcock was brought in and confronted by both Bristow and Grant's Attorney General Edwards Pierrepont. Babcock said that the messages had to do with the building of the St. LouisEads Bridge

The Eads Bridge is a combined road and railway bridge over the Mississippi River connecting the cities of St. Louis, Missouri, and East St. Louis, Illinois. It is located on the St. Louis riverfront between Laclede's Landing, St. Louis, Lacled ...

and Missouri politics. Grant accepted Babcock's explanation over the letters. In December 1875, nonetheless, Babcock was formerly indicted in the Whiskey Ring and his trial was set for February 1876 in St. Louis. During the trial President Grant, who believed Babcock was innocent, took a deposition at the White House that defended Babcock, and it was read to the jury in St. Louis. Babcock was acquitted by the jury and he returned to Washington, D.C.

Resignation

In the aftermath of the Whiskey Ring prosecutions, including Babcock's trial, and an upcoming 1876 presidential election, Bristow's position on Grant's cabinet became untenable. Grant was grieved at Bristow's prosecution of Babcock, whom Grant maintained was innocent. Also, rumors swirled that Bristow prosecuted the Whiskey Ring, to get the Republican nomination, that caused Grant to feel betrayed by Bristow. Largely owing to friction between himself and the president, Bristow resigned his portfolio in June 1876; as Secretary of the Treasury he advocated the resumption ofspecie

Specie may refer to:

* Coins or other metal money in mass circulation

* Bullion coins

* Hard money (policy)

* Commodity money

* Specie Circular, 1836 executive order by US President Andrew Jackson regarding hard money

* Specie Payment Resumption A ...

payments and at least a partial retirement of " greenbacks"; and he was also an advocate of civil service

The civil service is a collective term for a sector of government composed mainly of career civil service personnel hired rather than elected, whose institutional tenure typically survives transitions of political leadership. A civil service offic ...

reform. With his resignation, unlike other Grant appointed cabinet members, such as Ebenezer R. Hoar (''Attorney General''), Amos T. Akerman

Amos Tappan Akerman (February 23, 1821 – December 21, 1880) was an American politician who served as United States Attorney General under President Ulysses S. Grant from 1870 to 1871.

A native of New Hampshire, Akerman graduated from Dartmou ...

(''Attorney General''), and Marshall Jewell

Marshall Jewell (October 20, 1825 – February 10, 1883) was a manufacturer, pioneer telegrapher, telephone entrepreneur, world traveler, and political figure who served as List of Governors of Connecticut, 44th and 46th Governor of Connecticut, ...

(''Postmaster General''), Bristow avoided the harsher reality of direct dismissal by Grant.

Presidential run (1876)

Bristow was a prominent reforming candidate for the Republican presidential nomination in 1876 (see U.S. presidential election, 1876). He was defeated at the Republican convention;Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was the 19th president of the United States, serving from 1877 to 1881.

Hayes served as Cincinnati's city solicitor from 1858 to 1861. He was a staunch Abolitionism in the Un ...

received the nomination. During the 1876 Republican Presidential Convention, Stalwart members of the Republican party, friends of President Grant, believed Bristow had been disloyal to Grant during the Whiskey Ring prosecutions, by going after Babcock. Rumor spread that Bristow had prosecuted the Whiskey Ring in an attempt to gain the 1876 Presidential Republican nomination. Bristow, however, proved to be a loyal statesman

A statesman or stateswoman is a politician or a leader in an organization who has had a long and respected career at the national or international level, or in a given field.

Statesman or statesmen may also refer to:

Newspapers United States

...

and had desired to keep President Grant and the nation from scandal. When Sec. Bristow testified in front of a congressional committee on the Whiskey Ring, he would not give any specific information regarding his conversations with President Grant, having claimed executive privilege

Executive privilege is the right of the president of the United States and other members of the executive branch to maintain confidential communications under certain circumstances within the executive branch and to resist some subpoenas and ot ...

.

The 1876 Republican National Convention

The 1876 Republican National Convention was a presidential nominating convention held at the Exposition Hall in Cincinnati, Ohio on June 14–16, 1876. President Ulysses S. Grant had considered seeking a third term, but with various scandals, a ...

, was held at Exposition Hall, in Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ; colloquially nicknamed Cincy) is a city in Hamilton County, Ohio, United States, and its county seat. Settled in 1788, the city is located on the northern side of the confluence of the Licking River (Kentucky), Licking and Ohio Ri ...

, Ohio

Ohio ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Erie to the north, Pennsylvania to the east, West Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Indiana to the ...

. On the first Presidential Ballot, Bristow was third, at 113 votes, while James G. Blaine received 285 votes, followed by Oliver P. Morton, at 124 votes. On the fourth Presidential Ballot, Bristow finished second, at 126 votes, his highest number, while Blaine was first, at 292 votes. On the seventh and final Presidential Ballot, Bristow received only 21 votes. Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was the 19th president of the United States, serving from 1877 to 1881.

Hayes served as Cincinnati's city solicitor from 1858 to 1861. He was a staunch Abolitionism in the Un ...

, was elected the Republican presidential candidate, at 384 votes. Blaine finished a close second at 351 votes.

New York attorney

Bristow was upset over not winning the Republican presidential nomination and over the rumor he had been disloyal to President Grant. Bristow retired from politics, never again to run for political office. After 1878, he practiced law in

Bristow was upset over not winning the Republican presidential nomination and over the rumor he had been disloyal to President Grant. Bristow retired from politics, never again to run for political office. After 1878, he practiced law in New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

and on October 16, aged 46, he established the law partnership of ''Bristow, Peet, Burnett, & Opdyke.'' Bristow was a prominent leader of the Eastern bar and was elected the second president of the American Bar Association

The American Bar Association (ABA) is a voluntary association, voluntary bar association of lawyers and law students in the United States; national in scope, it is not specific to any single jurisdiction. Founded in 1878, the ABA's stated acti ...

in 1879. Having remained an advocate of civil service reform, Bristow was vice president of the ''Civil Service Reform Association''. Bristow often ably argued in front of the U.S. Supreme Court.

Death and burial

In 1896, Bristow sufferedappendicitis

Appendicitis is inflammation of the Appendix (anatomy), appendix. Symptoms commonly include right lower abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, fever and anorexia (symptom), decreased appetite. However, approximately 40% of people do not have these t ...

and died at his home in New York City on June 22, just two days after his 64th birthday. He was buried at Woodlawn Cemetery, Bronx, New York.

Historical reputation

Historians primarily admire Bristow's prosecution and shutting down theWhiskey Ring

The Whiskey Ring took place from 1871 to 1876 centering in St. Louis during the presidency of Ulysses S. Grant. The ring was an American scandal, broken in May 1875, involving the diversion of tax revenues in a conspiracy among government agent ...

during his term as Grant's Secretary of Treasury. Although a lawyer by trade and having no financial training, he was able to rid the Internal Revenue Department of corruption. Bristow demonstrated his ability and in striking down the Whiskey Ring that was supported by powerful political forces. Bristow's zeal for reform, while he was Grant's appointed Secretary of Treasury, was in part motivated by a sincere belief to clean up the Republican Party from corruption, and in part, an ambition to run for the presidency, and be nominated on the 1876 Republican presidential ticket. His prosecutions offended the social and political Republican Party stalwarts who supported patronage, forcing him out of office. As the first Solicitor General Bristow aided in prosecuting the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to KKK or Klan, is an American Protestant-led Christian terrorism, Christian extremist, white supremacist, Right-wing terrorism, far-right hate group. It was founded in 1865 during Reconstruction era, ...

that enabled African Americans

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from any of the Black racial groups of Africa ...

in the South to vote freely without fear of violent retaliation. He was born a Southerner in Kentucky, but he lived the remaining years of his life in New York.

Historian Jean Edward Smith said Bristow's appointment to Secretary of Treasury was "one of Grant's best." Smith said Bristow "brought a reforming zeal to the Grant administration, reinforced by a heady dose of ambition that was not out of place for a man in his early forties."

Historian Charles W. Calhoun, had a less positive view of Bristow. Calhoun said Bristow was "ambitious" and had a "contentious nature".

Historian Ronald C. White said Bristow, as Secretary of Treasury, "brought honesty to the position".

Historian Ron Chernow

Ronald Chernow (; born March 3, 1949) is an American writer, journalist, and biographer. He has written bestselling historical non-fiction biographies.

Chernow won the 2011 Pulitzer Prize, 2011 Pulitzer Prize for Biography and the 2011 American ...

said Bristow was "honest and competent", and: "A zealous advocate of civil service reform".

Historian William S. McFeely said Grant's appointment of Bristow to run the Treasury was "reluctant", and "the department passed into the impeccably clean hands of Benjamin Bristow, a sound money man."

References

Sources

Books

* scholarly review and response by Calhoun at DOI: 10.14296/RiH/2014/2270 * * * * * *Journals

*New York Times

*Further reading

*v * Webb, Ross A., ''Benjamin Helm Bristow, border state politician'', University Press of Kentucky (1969).External links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Bristow, Benjamin H. 1832 births 1896 deaths People from Elkton, Kentucky Kentucky Whigs Kentucky Republicans Kentucky lawyers United States attorneys for the District of Kentucky Solicitors general of the United States United States secretaries of the treasury Union army colonels Presidents of the American Bar Association Washington & Jefferson College alumni Candidates in the 1876 United States presidential election Grant administration cabinet members Burials at Woodlawn Cemetery (Bronx, New York) Founding members of the American Bar Association American anti-corruption activists People of Kentucky in the American Civil War 19th-century members of the Kentucky General Assembly Unionist Kentucky state senators