Battle Of The Golden Spurs on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Battle of the Golden Spurs ( nl, Guldensporenslag; french: Bataille des éperons d'or) was a military confrontation between the royal army of

In June 1297, the French invaded Flanders and gained some rapid successes. The English, under Edward I, withdrew to face a war with Scotland, and the Flemish and French signed a temporary armistice in 1297, the Truce of Sint-Baafs-Vijve, which halted the conflict. In January 1300, when the truce expired, the French invaded Flanders again, and by May, were in total control of the county. Guy of Dampierre was imprisoned and Philip himself toured Flanders making administrative changes.

After Philip left Flanders, unrest broke out again in the Flemish city of Bruges directed against the French governor of Flanders,

In June 1297, the French invaded Flanders and gained some rapid successes. The English, under Edward I, withdrew to face a war with Scotland, and the Flemish and French signed a temporary armistice in 1297, the Truce of Sint-Baafs-Vijve, which halted the conflict. In January 1300, when the truce expired, the French invaded Flanders again, and by May, were in total control of the county. Guy of Dampierre was imprisoned and Philip himself toured Flanders making administrative changes.

After Philip left Flanders, unrest broke out again in the Flemish city of Bruges directed against the French governor of Flanders,

The Flemish were primarily town

The Flemish were primarily town

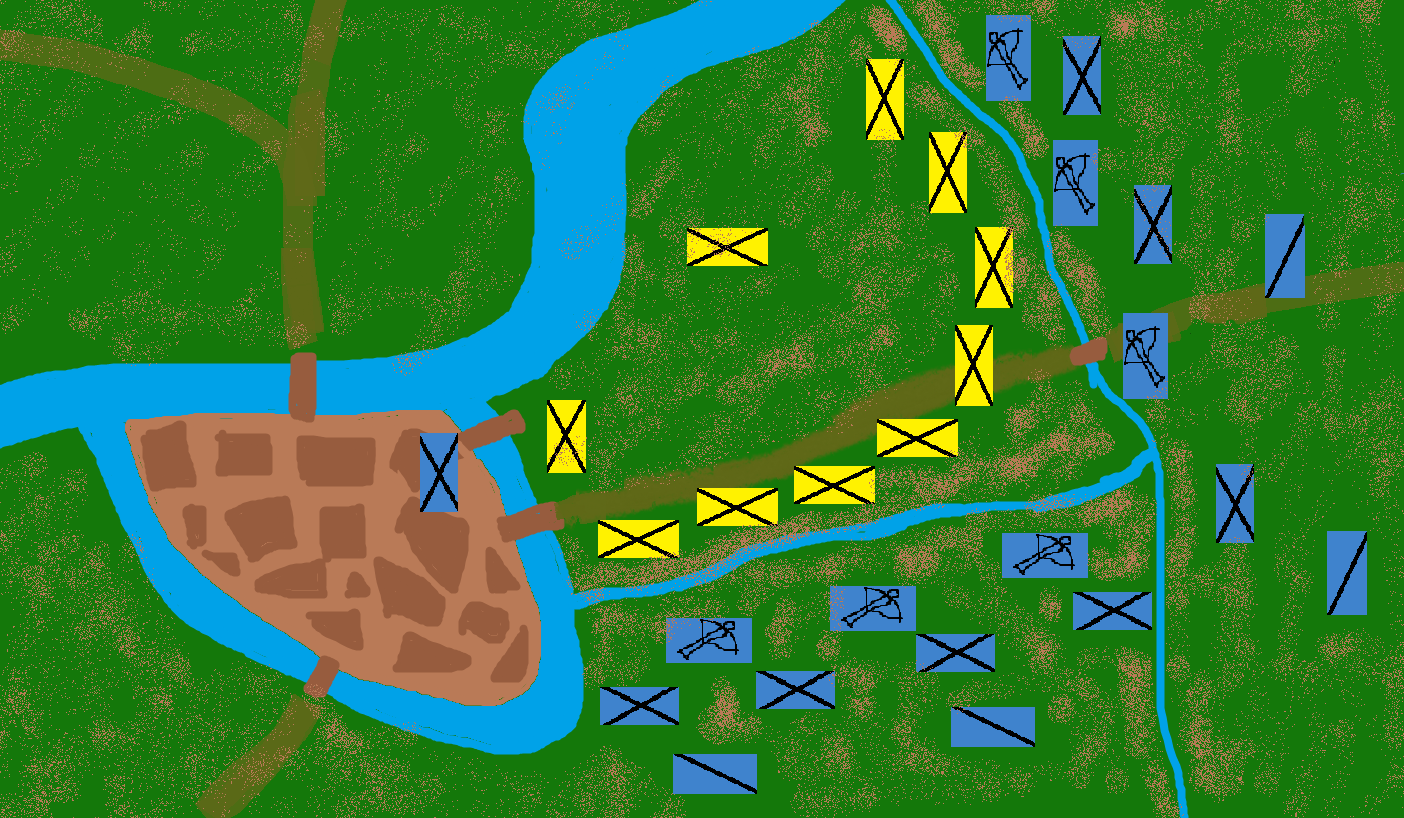

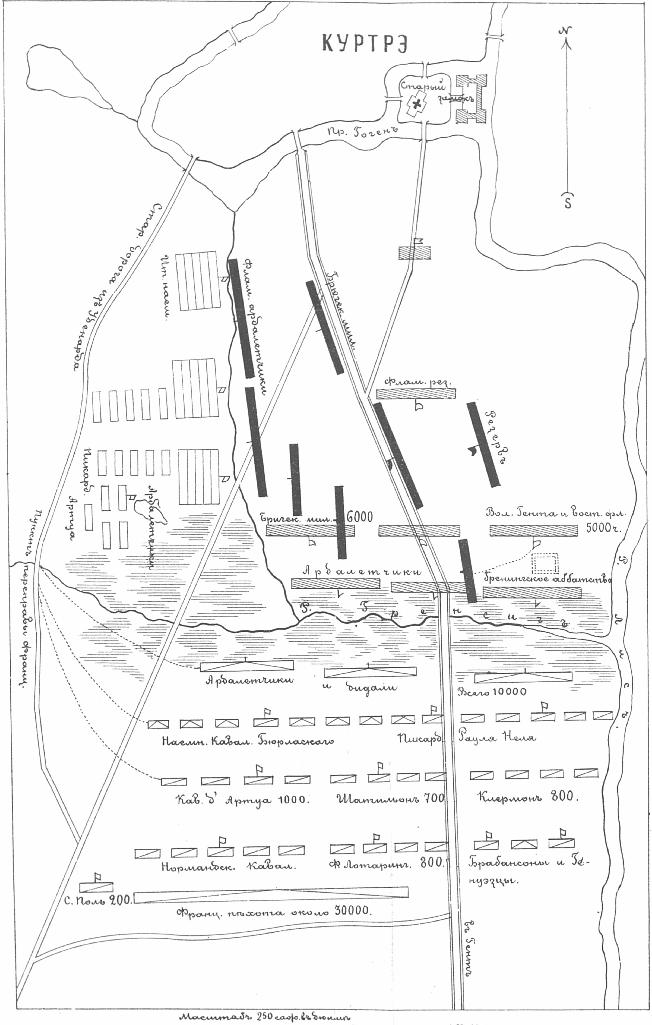

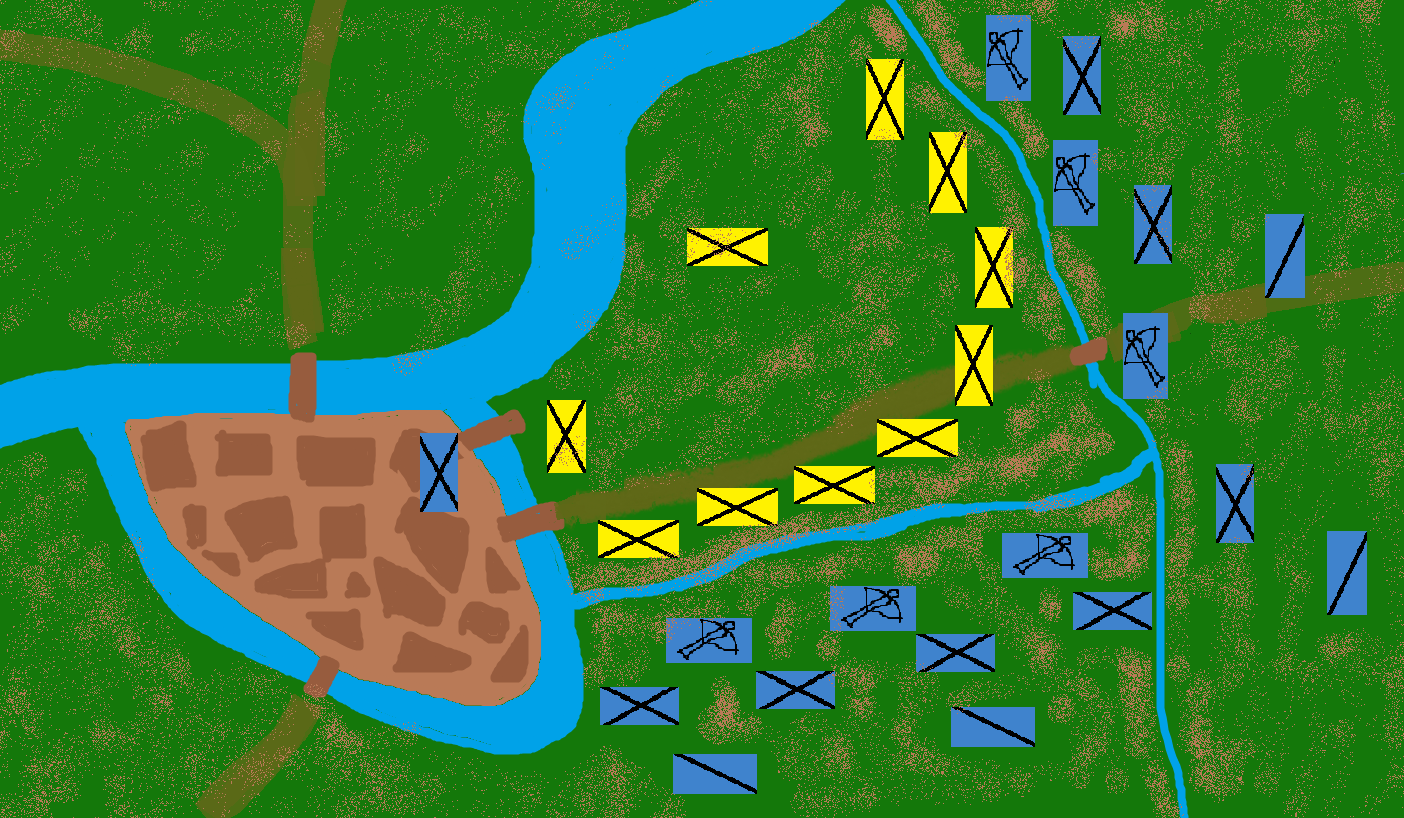

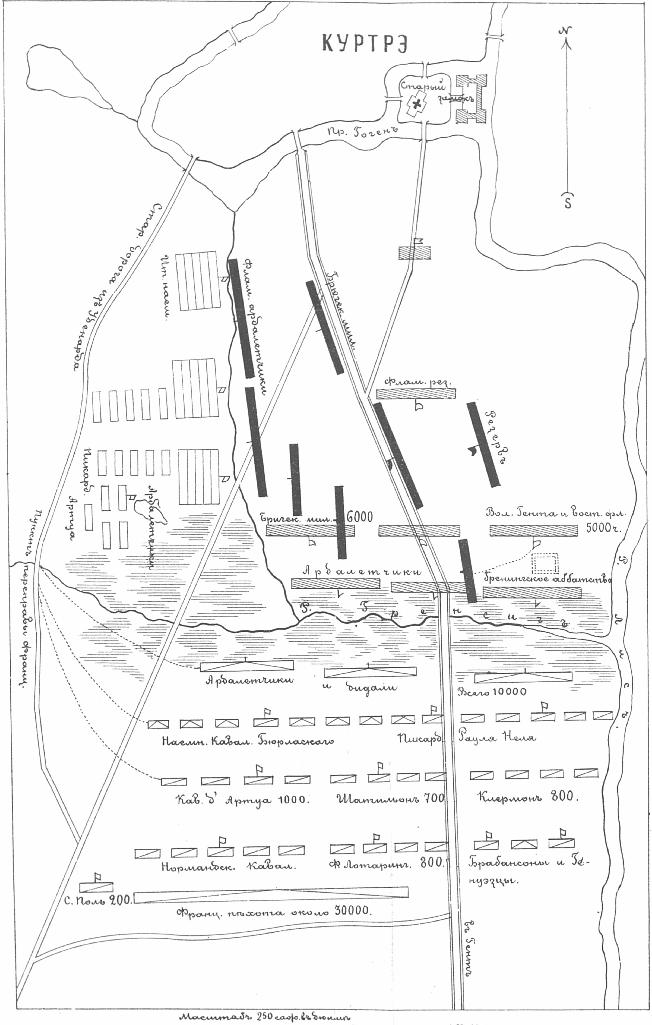

The combined Flemish forces met at Kortrijk on 26 June and laid siege to the castle, which housed a French garrison. As the siege was being laid, the Flemish leaders began preparing a nearby field for battle. The size of the French response was impressive, with 3,000

The combined Flemish forces met at Kortrijk on 26 June and laid siege to the castle, which housed a French garrison. As the siege was being laid, the Flemish leaders began preparing a nearby field for battle. The size of the French response was impressive, with 3,000  Some of the French footmen were trampled to death by the armoured cavalry, but most managed to get back around them or through the gaps in their lines. The cavalry advanced rapidly across the streams and ditches to give the Flemish no time to react. The brooks presented difficulties for the French horsemen and a few fell from their steeds. Despite initial confusion, the crossing was successful in the end. The French reorganized their formations on the other side to maximize their effectiveness in battle.

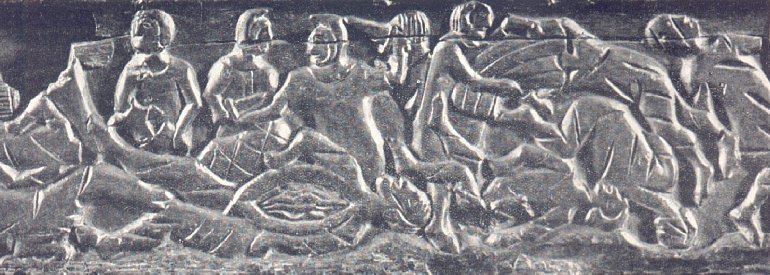

Ready for combat, the French knights and men-at-arms charged at a quick trot and with their lances ready against the main Flemish line. The Flemish crossbowmen and archers fell back behind the pikemen. A great noise rose throughout the dramatic battle scene. The disciplined Flemish foot-soldiers kept their pikes ready on the ground and their ''goedendags'' raised to meet the French charge. The Flemish infantry wall did not flinch and a part of the French cavalry hesitated. The bulk of the French formations carried on their forward momentum and fell on the Flemish in an ear-splitting crash of horses against men. Unable at most points to break the Flemish line of pikemen, many French knights were knocked from their horses and killed with the ''goedendag'', the spike of which was designed to penetrate the spaces between armour segments. Those cavalry groups that succeeded in breaking through were set upon by the reserve lines, surrounded and wiped out.

Some of the French footmen were trampled to death by the armoured cavalry, but most managed to get back around them or through the gaps in their lines. The cavalry advanced rapidly across the streams and ditches to give the Flemish no time to react. The brooks presented difficulties for the French horsemen and a few fell from their steeds. Despite initial confusion, the crossing was successful in the end. The French reorganized their formations on the other side to maximize their effectiveness in battle.

Ready for combat, the French knights and men-at-arms charged at a quick trot and with their lances ready against the main Flemish line. The Flemish crossbowmen and archers fell back behind the pikemen. A great noise rose throughout the dramatic battle scene. The disciplined Flemish foot-soldiers kept their pikes ready on the ground and their ''goedendags'' raised to meet the French charge. The Flemish infantry wall did not flinch and a part of the French cavalry hesitated. The bulk of the French formations carried on their forward momentum and fell on the Flemish in an ear-splitting crash of horses against men. Unable at most points to break the Flemish line of pikemen, many French knights were knocked from their horses and killed with the ''goedendag'', the spike of which was designed to penetrate the spaces between armour segments. Those cavalry groups that succeeded in breaking through were set upon by the reserve lines, surrounded and wiped out.

To turn the tide of the battle, Artois ordered his rearguard of 700 men-at-arms to advance, joining the battle personally with his own knights and with

To turn the tide of the battle, Artois ordered his rearguard of 700 men-at-arms to advance, joining the battle personally with his own knights and with

With the French army defeated, the Flemish consolidated control over the County. Kortrijk castle surrendered on 13 July and John of Namur entered Ghent on 14 July and the "patrician" regime in the city and in Ypres were overthrown and replaced by more representative regimes. Guilds were also officially recognised.

The battle soon became known as the Battle of the Golden Spurs, after the 500 pairs of spurs that were captured in the battle and offered at the nearby Church of Our Lady. After the Battle of Roosebeke in 1382, the spurs were taken back by the French and Kortrijk was sacked by Charles VI in retaliation.

According to the ''Annals'', the French lost more than 1,000 men during the battle, including 75 important nobles. These included:

* Robert II, Count of Artois and his half-brother James

* Raoul of Clermont-Nesle, Lord of

With the French army defeated, the Flemish consolidated control over the County. Kortrijk castle surrendered on 13 July and John of Namur entered Ghent on 14 July and the "patrician" regime in the city and in Ypres were overthrown and replaced by more representative regimes. Guilds were also officially recognised.

The battle soon became known as the Battle of the Golden Spurs, after the 500 pairs of spurs that were captured in the battle and offered at the nearby Church of Our Lady. After the Battle of Roosebeke in 1382, the spurs were taken back by the French and Kortrijk was sacked by Charles VI in retaliation.

According to the ''Annals'', the French lost more than 1,000 men during the battle, including 75 important nobles. These included:

* Robert II, Count of Artois and his half-brother James

* Raoul of Clermont-Nesle, Lord of

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and rebellious forces of the County of Flanders

The County of Flanders was a historic territory in the Low Countries.

From 862 onwards, the counts of Flanders were among the original twelve peers of the Kingdom of France. For centuries, their estates around the cities of Ghent, Bruges a ...

on 11 July 1302 during the Franco-Flemish War (1297–1305). It took place near the town of Kortrijk

Kortrijk ( , ; vls, Kortryk or ''Kortrik''; french: Courtrai ; la, Cortoriacum), sometimes known in English as Courtrai or Courtray ( ), is a Belgian city and municipality in the Flemish province of West Flanders.

It is the capital and larg ...

(Courtrai) in modern-day Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to ...

and resulted in an unexpected victory for the Flemish. It is sometimes referred to as the Battle of Courtrai.

On 18 May 1302, after two years of French military occupation and several years of unrest, many cities in Flanders revolted against French rule, and the local militia massacred many Frenchmen in the city of Bruges

Bruges ( , nl, Brugge ) is the capital and largest City status in Belgium, city of the Provinces of Belgium, province of West Flanders in the Flemish Region of Belgium, in the northwest of the country, and the sixth-largest city of the countr ...

. King Philip IV of France

Philip IV (April–June 1268 – 29 November 1314), called Philip the Fair (french: Philippe le Bel), was King of France from 1285 to 1314. By virtue of his marriage with Joan I of Navarre, he was also King of Navarre as Philip I from 12 ...

immediately organized an expedition of 8,000 troops, including 2,500 men-at-arms, under Count Robert II of Artois

Robert II (September 1250 – 11 July 1302) was the Count of Artois, the posthumous son and heir of Robert I and Matilda of Brabant. He was a nephew of Louis IX of France. He died at the Battle of the Golden Spurs.

Life

An experienced soldier, ...

to put down the rebellion. Meanwhile, 9,400 men from the civic militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

s of several Flemish cities were assembled to counter the expected French attack.

When the two armies met outside the city of Kortrijk on 11 July, the cavalry charges of the mounted French men-at-arms proved unable to defeat the mail-armoured and well-trained Flemish militia infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and mar ...

's pike formation. The result was a rout

A rout is a panicked, disorderly and undisciplined retreat of troops from a battlefield, following a collapse in a given unit's command authority, unit cohesion and combat morale (''esprit de corps'').

History

Historically, lightly-e ...

of the French nobles, who suffered heavy losses at the hands of the Flemish. The 500 pairs of spurs that were captured from the French horsemen gave the battle its popular name. The battle was a famous early example of an all-infantry army overcoming an army that depended on the shock attacks of heavy cavalry.

While France was victorious in the overall Franco-Flemish War, the Battle of the Golden Spurs became an important cultural reference point for the Flemish Movement during the 19th and 20th centuries. In 1973, the date of the battle was chosen for the official holiday of the Flemish Community in Belgium.

A 1985 film called ''De leeuw van Vlaanderen (The Lion of Flanders)'' shows the battle, and the politics that led up to it.

Background

The origins of the Franco-Flemish War (1297–1305) can be traced back to the accession of Philip IV "the Fair" to the French throne in 1285. Philip hoped to reassert control over theCounty of Flanders

The County of Flanders was a historic territory in the Low Countries.

From 862 onwards, the counts of Flanders were among the original twelve peers of the Kingdom of France. For centuries, their estates around the cities of Ghent, Bruges a ...

, a semi-independent polity notionally part of the Kingdom of France

The Kingdom of France ( fro, Reaume de France; frm, Royaulme de France; french: link=yes, Royaume de France) is the historiographical name or umbrella term given to various political entities of France in the medieval and early modern period. ...

, and possibly even to annex it into the crown lands of France. In the 1290s, Philip attempted to gain support from the Flemish aristocracy and succeeded in winning the allegiance of some local notables, including John of Avesnes (Count of Hainaut, Holland

Holland is a geographical regionG. Geerts & H. Heestermans, 1981, ''Groot Woordenboek der Nederlandse Taal. Deel I'', Van Dale Lexicografie, Utrecht, p 1105 and former Provinces of the Netherlands, province on the western coast of the Netherland ...

and Zeeland). He was opposed by a faction led by the Flemish knight Guy of Dampierre who attempted to form a marriage alliance with the English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

against Philip. In Flanders, however, many of the cities were split into factions known as the "Lilies" (''Leliaerts''), who were pro-French, and the "Claws" (''Clauwaerts''), led by Pieter de Coninck in Bruges

Bruges ( , nl, Brugge ) is the capital and largest City status in Belgium, city of the Provinces of Belgium, province of West Flanders in the Flemish Region of Belgium, in the northwest of the country, and the sixth-largest city of the countr ...

, who advocated independence.

In June 1297, the French invaded Flanders and gained some rapid successes. The English, under Edward I, withdrew to face a war with Scotland, and the Flemish and French signed a temporary armistice in 1297, the Truce of Sint-Baafs-Vijve, which halted the conflict. In January 1300, when the truce expired, the French invaded Flanders again, and by May, were in total control of the county. Guy of Dampierre was imprisoned and Philip himself toured Flanders making administrative changes.

After Philip left Flanders, unrest broke out again in the Flemish city of Bruges directed against the French governor of Flanders,

In June 1297, the French invaded Flanders and gained some rapid successes. The English, under Edward I, withdrew to face a war with Scotland, and the Flemish and French signed a temporary armistice in 1297, the Truce of Sint-Baafs-Vijve, which halted the conflict. In January 1300, when the truce expired, the French invaded Flanders again, and by May, were in total control of the county. Guy of Dampierre was imprisoned and Philip himself toured Flanders making administrative changes.

After Philip left Flanders, unrest broke out again in the Flemish city of Bruges directed against the French governor of Flanders, Jacques de Châtillon

Jacques de Châtillon or James of Châtillon (died 11 July 1302) was Lord of Leuze, of Condé, of Carency, of Huquoy and of Aubigny, the son of Guy III, Count of Saint-Pol and Matilda of Brabant. He married Catherine of Condé and had issue.

K ...

. On 18 May 1302, rebellious citizens who had fled Bruges returned to the city and murdered every Frenchman they could find, an act known as the '' Bruges Matins''. With Guy of Dampierre still imprisoned, command of the rebellion was taken by John and Guy of Namur

Guy of Dampierre, Count of Zeeland, also called Guy of Namur ( nl, region=BE, Gwijde van Namen, label=Flemish) (ca. 1272 – 13 October 1311 in Pavia), was a Flemish noble who was the Lord of Ronse and later the self-proclaimed Count of Zeeland ...

. Most of the towns of the County of Flanders agreed to join the Bruges rebellion except for the city of Ghent

Ghent ( nl, Gent ; french: Gand ; traditional English: Gaunt) is a city and a municipality in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is the capital and largest city of the East Flanders province, and the third largest in the country, exceeded i ...

which refused to take part. Most of the Flemish nobility also took the French side, fearful of what had become an attempt to take power by the lower classes.

Forces

In order to quell the revolt, Philip sent a powerful force led by Count Robert II of Artois to march on Bruges. Against the French, the Flemish under William of Jülich fielded a largelyinfantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and mar ...

force which was drawn mainly from Bruges, West Flanders

West Flanders ( nl, West-Vlaanderen ; vls, West Vloandern; french: (Province de) Flandre-Occidentale ; german: Westflandern ) is the westernmost province of the Flemish Region, in Belgium. It is the only coastal Belgian province, facing the No ...

, and the east of the county. The city of Ypres

Ypres ( , ; nl, Ieper ; vls, Yper; german: Ypern ) is a Belgian city and municipality in the province of West Flanders. Though

the Dutch name is the official one, the city's French name is most commonly used in English. The municipality ...

sent a contingent of five hundred men under Jan van Renesse, and despite their city's refusal to join the revolt, Jan Borluut arrived with seven hundred volunteers from Ghent.

militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

who were well equipped and trained. The militia fought primarily as infantry, were organized by guild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular area. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradesmen belonging to a professional association. They sometim ...

, and were equipped with steel

Steel is an alloy made up of iron with added carbon to improve its strength and fracture resistance compared to other forms of iron. Many other elements may be present or added. Stainless steels that are corrosion- and oxidation-resistan ...

helmets, mail

The mail or post is a system for physically transporting postcards, letters, and parcels. A postal service can be private or public, though many governments place restrictions on private systems. Since the mid-19th century, national postal sys ...

haubergeons, spear

A spear is a pole weapon consisting of a shaft, usually of wood, with a pointed head. The head may be simply the sharpened end of the shaft itself, as is the case with fire hardened spears, or it may be made of a more durable material fastene ...

s, pikes, bows, crossbow

A crossbow is a ranged weapon using an Elasticity (physics), elastic launching device consisting of a Bow and arrow, bow-like assembly called a ''prod'', mounted horizontally on a main frame called a ''tiller'', which is hand-held in a similar ...

s and the ''goedendag

A goedendag ( Dutch for "good day"; also rendered godendac, godendard, godendart, and sometimes conflated with the related plançon) was a weapon originally used by the militias of Medieval Flanders in the 14th century, notably during the Fran ...

''. All Flemish troops at the battle had helmets, neck protection, iron or steel gloves and effective weapons, though not all could afford mail armor. The ''goedendag'' was a specifically Flemish weapon, made from a thick -long wooden shaft and topped with a steel spike. They were a well-organized force of 8,000–10,000 infantry, as well as four hundred noblemen, and the urban militias of the time prided themselves on their regular training and preparation. About 900 of the Flemish were crossbowmen. The Flemish militia formed a line formation against cavalry with ''goedendags'' and pikes pointed outward. Because of the high rate of defections among the Flemish nobility, there were few mounted knights on the Flemish side. The ''Annals of Ghent

The ''Annals of Ghent'' ( la, Annales Gandenses) is a short Medieval chronicle which is an important source on the Franco-Flemish War (1297–1305), the Crusade of the Poor (1309), and the history of the County of Flanders. Written by an unknown F ...

'' claimed that there were just ten cavalrymen in the Flemish force.

The French, by contrast, fielded a royal army with a core of 2,500 noble cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry in ...

, including knights and squires, arrayed into ten formations of 250 armored horsemen. During the deployment for the battle, they were arranged into three battles, of which the first two were to attack and the third to function as a rearguard and reserve

Reserve or reserves may refer to:

Places

* Reserve, Kansas, a US city

* Reserve, Louisiana, a census-designated place in St. John the Baptist Parish

* Reserve, Montana, a census-designated place in Sheridan County

* Reserve, New Mexico, a US ...

. They were supported by about 5,500 infantry, a mix of crossbow

A crossbow is a ranged weapon using an Elasticity (physics), elastic launching device consisting of a Bow and arrow, bow-like assembly called a ''prod'', mounted horizontally on a main frame called a ''tiller'', which is hand-held in a similar ...

men, spearmen, and light infantry

Light infantry refers to certain types of lightly equipped infantry throughout history. They have a more mobile or fluid function than other types of infantry, such as heavy infantry or line infantry. Historically, light infantry often foug ...

. The French had about 1,000 crossbowmen, most of whom were from the Kingdom of France and perhaps a few hundred were recruited from northern Italy and Spain. Contemporary military theory valued each knight as equal to roughly ten footmen.

The Battle

The combined Flemish forces met at Kortrijk on 26 June and laid siege to the castle, which housed a French garrison. As the siege was being laid, the Flemish leaders began preparing a nearby field for battle. The size of the French response was impressive, with 3,000

The combined Flemish forces met at Kortrijk on 26 June and laid siege to the castle, which housed a French garrison. As the siege was being laid, the Flemish leaders began preparing a nearby field for battle. The size of the French response was impressive, with 3,000 knights

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the ...

and 4,000–5,000 infantry being an accepted estimate. The Flemish failed to take the castle and the two forces clashed on 11 July in an open field near the city next to the Groeninge stream

A stream is a continuous body of surface water flowing within the bed and banks of a channel. Depending on its location or certain characteristics, a stream may be referred to by a variety of local or regional names. Long large streams ...

.

The field near Kortrijk was crossed by numerous ditches

A ditch is a small to moderate divot created to channel water. A ditch can be used for drainage, to drain water from low-lying areas, alongside roadways or fields, or to channel water from a more distant source for plant irrigation. Ditches ...

and streams dug by the Flemish as Philip's army assembled. Some drained from the river Leie

The Lys () or Leie () is a river in France and Belgium, and a left-bank tributary of the Scheldt. Its source is in Pas-de-Calais, France, and it flows into the river Scheldt in Ghent, Belgium. Its total length is .

Historically a very poll ...

(or Lys), while others were concealed with dirt and tree branches, making it difficult for the French cavalry to charge the Flemish lines. The marshy ground also made the cavalry less effective. The French sent servants to place wood in the streams, but they were attacked before they completed their task. The Flemish placed themselves in a strong defensive position, in deeply stacked lines forming a square. The rear of the square was covered by a curve of the river Leie. The front presented a wedge to the French army and was placed behind larger rivulets.

The 1,000 French crossbowmen attacked their 900 Flemish counterparts and succeeded in forcing them back. Eventually, the French crossbow bolt

A bolt or quarrel is a dart-like projectile used by crossbows. The name "quarrel" is derived from the French word ''carré'', meaning square, referring to their typically square heads. Although their lengths vary, bolts are typically shorter and ...

s and arrows began to hit the main Flemish infantry formations' front ranks but inflicted little damage.

The French commander Robert of Artois was worried the outnumbered French foot would be attacked from all sides by superior, heavily armed Flemish infantry on the other side of the brooks. Furthermore, the Flemish would then have their formations right on edge of the brooks and a successful French cavalry crossing would be extremely difficult. He therefore recalled his foot soldiers to clear the way for 2,300 heavy cavalry arranged into two attack formations. The French cavalry unfurled their banner

A banner can be a flag or another piece of cloth bearing a symbol, logo, slogan or another message. A flag whose design is the same as the shield in a coat of arms (but usually in a square or rectangular shape) is called a banner of arms. Als ...

s and advanced on the command "Forward!".

Some of the French footmen were trampled to death by the armoured cavalry, but most managed to get back around them or through the gaps in their lines. The cavalry advanced rapidly across the streams and ditches to give the Flemish no time to react. The brooks presented difficulties for the French horsemen and a few fell from their steeds. Despite initial confusion, the crossing was successful in the end. The French reorganized their formations on the other side to maximize their effectiveness in battle.

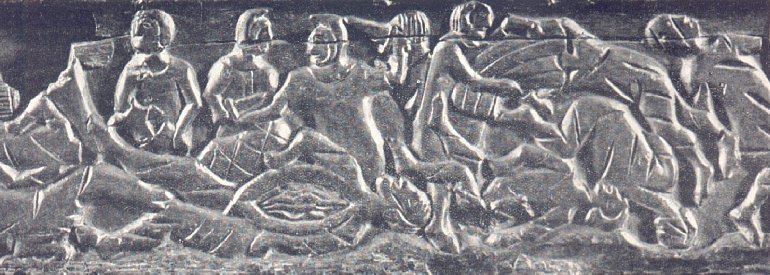

Ready for combat, the French knights and men-at-arms charged at a quick trot and with their lances ready against the main Flemish line. The Flemish crossbowmen and archers fell back behind the pikemen. A great noise rose throughout the dramatic battle scene. The disciplined Flemish foot-soldiers kept their pikes ready on the ground and their ''goedendags'' raised to meet the French charge. The Flemish infantry wall did not flinch and a part of the French cavalry hesitated. The bulk of the French formations carried on their forward momentum and fell on the Flemish in an ear-splitting crash of horses against men. Unable at most points to break the Flemish line of pikemen, many French knights were knocked from their horses and killed with the ''goedendag'', the spike of which was designed to penetrate the spaces between armour segments. Those cavalry groups that succeeded in breaking through were set upon by the reserve lines, surrounded and wiped out.

Some of the French footmen were trampled to death by the armoured cavalry, but most managed to get back around them or through the gaps in their lines. The cavalry advanced rapidly across the streams and ditches to give the Flemish no time to react. The brooks presented difficulties for the French horsemen and a few fell from their steeds. Despite initial confusion, the crossing was successful in the end. The French reorganized their formations on the other side to maximize their effectiveness in battle.

Ready for combat, the French knights and men-at-arms charged at a quick trot and with their lances ready against the main Flemish line. The Flemish crossbowmen and archers fell back behind the pikemen. A great noise rose throughout the dramatic battle scene. The disciplined Flemish foot-soldiers kept their pikes ready on the ground and their ''goedendags'' raised to meet the French charge. The Flemish infantry wall did not flinch and a part of the French cavalry hesitated. The bulk of the French formations carried on their forward momentum and fell on the Flemish in an ear-splitting crash of horses against men. Unable at most points to break the Flemish line of pikemen, many French knights were knocked from their horses and killed with the ''goedendag'', the spike of which was designed to penetrate the spaces between armour segments. Those cavalry groups that succeeded in breaking through were set upon by the reserve lines, surrounded and wiped out.

To turn the tide of the battle, Artois ordered his rearguard of 700 men-at-arms to advance, joining the battle personally with his own knights and with

To turn the tide of the battle, Artois ordered his rearguard of 700 men-at-arms to advance, joining the battle personally with his own knights and with trumpet

The trumpet is a brass instrument commonly used in classical and jazz ensembles. The trumpet group ranges from the piccolo trumpet—with the highest register in the brass family—to the bass trumpet, pitched one octave below the standard ...

s blaring. The rearguard did not attack the Flemish however, remaining stationary after its initial advance to protect the French baggage train. Artois' charge routed some of the Flemish troops under Guy of Namur, but could not break the entire Flemish formation. Artois' men-at-arms were attacked by fresh Flemish forces and the French fought back with desperate courage, aware of the danger they were in. Artois defended himself skillfully. His horse was struck down by a lay brother, Willem van Saeftinghe, and the count himself was killed, covered with multiple wounds. According to some tales, he begged for his life, but the Flemish refused to spare him, claiming that they did not understand French.

When ultimately the French knights became aware that they could no longer be reinforced, their attacks faltered and they were gradually driven back into the rivulet marshes. There, disorganized, unhorsed, and encumbered by the mud, they were an easy target for the heavily armed Flemish infantry. A desperate charge by the French garrison in the besieged castle was thwarted by a Flemish contingent specifically placed there for that task. The French infantry was visibly shaken by the sight of their knights being slaughtered and withdrew from the rivulets. The Flemish front ranks then charged forward, routing their opponents, who were massacred. The surviving French fled, only to be pursued over by the Flemish. Unusually for the period, the Flemish infantry took few if any of the French knights prisoner for ransom, in revenge for the French "cruelty".

The ''Annals of Ghent'' concludes its description of the battle:

Aftermath

With the French army defeated, the Flemish consolidated control over the County. Kortrijk castle surrendered on 13 July and John of Namur entered Ghent on 14 July and the "patrician" regime in the city and in Ypres were overthrown and replaced by more representative regimes. Guilds were also officially recognised.

The battle soon became known as the Battle of the Golden Spurs, after the 500 pairs of spurs that were captured in the battle and offered at the nearby Church of Our Lady. After the Battle of Roosebeke in 1382, the spurs were taken back by the French and Kortrijk was sacked by Charles VI in retaliation.

According to the ''Annals'', the French lost more than 1,000 men during the battle, including 75 important nobles. These included:

* Robert II, Count of Artois and his half-brother James

* Raoul of Clermont-Nesle, Lord of

With the French army defeated, the Flemish consolidated control over the County. Kortrijk castle surrendered on 13 July and John of Namur entered Ghent on 14 July and the "patrician" regime in the city and in Ypres were overthrown and replaced by more representative regimes. Guilds were also officially recognised.

The battle soon became known as the Battle of the Golden Spurs, after the 500 pairs of spurs that were captured in the battle and offered at the nearby Church of Our Lady. After the Battle of Roosebeke in 1382, the spurs were taken back by the French and Kortrijk was sacked by Charles VI in retaliation.

According to the ''Annals'', the French lost more than 1,000 men during the battle, including 75 important nobles. These included:

* Robert II, Count of Artois and his half-brother James

* Raoul of Clermont-Nesle, Lord of Nesle

Nesle () is a commune in the Somme department in Hauts-de-France in northern France.

Geography

Nesle is situated at the junction of the D930 and D337 roads, some southwest of Saint-Quentin. The Ingon, a small stream, passes through the commu ...

, Constable of France

The Constable of France (french: Connétable de France, from Latin for 'count of the stables') was lieutenant to the King of France, the first of the original five Great Officers of the Crown (along with seneschal, chamberlain, butler, and ...

* Guy I of Clermont

Guy I of Clermont-Nesle (c. 1255 – 11 July 1302) was a Marshal of France, Seigneur (Lord) of Offemont ''jure uxoris'', and possibly of Ailly, Maulette and Breteuil. He might have been a Seigneur of Nesle also, or used the title "Sire of Nesl ...

, Lord of Breteuil, Marshal of France

Marshal of France (french: Maréchal de France, plural ') is a French military distinction, rather than a military rank, that is awarded to generals for exceptional achievements. The title has been awarded since 1185, though briefly abolished ( ...

* Simon de Melun

Simon de Melun (1250 – 11 July 1302 in Kortrijk) was a Marshal of France killed in the Battle of the Golden Spurs.

He was a younger son of Viscount Adam II of Melun and Constance of Sancerre. From his mother, he inherited the castles of L ...

, Lord of La Loupe and Marcheville, Marshal of France

Marshal of France (french: Maréchal de France, plural ') is a French military distinction, rather than a military rank, that is awarded to generals for exceptional achievements. The title has been awarded since 1185, though briefly abolished ( ...

* John I of Ponthieu, Count of Aumale

* John II of Trie, Count of Dammartin

* John II of Brienne, Count of Eu

* John of Avesnes, Count of Ostrevent, son of John II, Count of Holland

John II (1247 – 22 August 1304) was Count of Hainaut, Holland, and Zeeland.

Life

John II, born 1247, was the eldest son of John I of Hainaut and Adelaide of Holland.Detlev Schwennicke, ''Europäische Stammtafeln: Stammtafeln zur Geschichte der ...

* Godfrey of Brabant, Lord of Aarschot and Vierzon, and his son John of Vierzon

* Jacques de Châtillon

Jacques de Châtillon or James of Châtillon (died 11 July 1302) was Lord of Leuze, of Condé, of Carency, of Huquoy and of Aubigny, the son of Guy III, Count of Saint-Pol and Matilda of Brabant. He married Catherine of Condé and had issue.

K ...

, Lord of Leuze

* Pierre de Flotte, Chief Advisor to Philip IV the Fair

* Raoul de Nesle, son of John III, Count of Soissons John III (died before 8 October 1286), son of John II, Count of Soissons, and Marie de Chimay. Count of Soissons and Seigneur of Chimay. John inherited the countship of Soissons upon his father’s death in 1272.

John married Marguerite de Montfo ...

.

The Flemish victory at Kortrijk in 1302 was quickly reversed by the French. In 1304, the French destroyed the Flemish fleet at the Battle of Zierikzee and fought the Flemish at the battle at Mons-en-Pévèle. In June 1305, negotiations between the two sides led to the Peace of Athis-sur-Orge in which the Flemish were forced to pay the French substantial tribute. Robert of Béthune subsequently lost against the French between 1314 and 1320.

The town of Kortrijk hosts many monuments and a museum dedicated to the battle.

Historical significance

Effect on warfare

The Battle of the Golden Spurs had been seen as the first example of the gradual "Infantry Revolution

The Military Revolution is the theory that a series of radical changes in military strategy and tactics during the 16th and 17th centuries resulted in major lasting changes in governments and society. The theory was introduced by Michael Roberts i ...

" in Medieval warfare across Europe during the 14th century. Conventional military theory placed emphasis on mounted and heavily armoured knights which were considered essential to military success. Infantry remained, however, an essential arm in parts of Europe, such as the British Isles, throughout the Middle Ages. This meant that warfare was the preserve of a wealthy elite of ''bellatores'' (nobles specialized in warfare) serving as men-at-arms. The fact that this form of army, which was expensive to maintain, could be defeated by militia drawn from the "lower orders" led to a gradual change in the nature of warfare during the subsequent century. The tactics and composition of the Flemish army at Courtrai were later copied or adapted at the battles of Bannockburn (1314), Crecy (1346), Aljubarrota

Aljubarrota is a ''freguesia'' ("civil parish") in the municipality of Alcobaça, Portugal. It was formed in 2013 by the merger of the parishes of Prazeres and São Vicente. Its population in 2011 was 6,639Sempach (1386), Agincourt (1415),

Amid that resurgence, the Battle of the Golden Spurs became the subject of an "extensive cult" in 19th- and 20th-century Flanders. After Belgian independence in 1830, the Flemish victory was interpreted as a symbol of local pride. The battle was painted in 1836 by a leading Romanticist painter

Amid that resurgence, the Battle of the Golden Spurs became the subject of an "extensive cult" in 19th- and 20th-century Flanders. After Belgian independence in 1830, the Flemish victory was interpreted as a symbol of local pride. The battle was painted in 1836 by a leading Romanticist painter

Liebaart.org

{{DEFAULTSORT:Golden Spurs, Battle of The Battles of the Middle Ages 14th century in the county of Flanders Battle of the Golden Spurs Battles involving Flanders Battles involving France Battles in Flanders 1302 in Europe 1300s in France Conflicts in 1302 Franco-Flemish War

Grandson

Family (from la, familia) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its members and of society. Ideall ...

(1476) and in the battles of the Hussite Wars

The Hussite Wars, also called the Bohemian Wars or the Hussite Revolution, were a series of civil wars fought between the Hussites and the combined Catholic forces of Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor, Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund, the Papacy, Eur ...

(1419–34). As a result, cavalry became less important and nobles more commonly fought dismounted. The comparatively low costs of militia armies allowed even small states (such as the Swiss

Swiss may refer to:

* the adjectival form of Switzerland

*Swiss people

Places

* Swiss, Missouri

*Swiss, North Carolina

* Swiss, West Virginia

*Swiss, Wisconsin

Other uses

* Swiss-system tournament, in various games and sports

* Swiss Internation ...

) to raise militarily significant armies and meant that local rebellions were more likely to achieve military success.

In Flemish culture and politics

Interest in medieval history in Belgium emerged during the 19th century alongside the rise ofRomanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

in art and literature. According to the historian Jo Tollebeek, it soon became connected to nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Th ...

ideals because the Middle Ages were "a period that could be linked with the most important contemporary aspirations" of romantic nationalism.

Amid that resurgence, the Battle of the Golden Spurs became the subject of an "extensive cult" in 19th- and 20th-century Flanders. After Belgian independence in 1830, the Flemish victory was interpreted as a symbol of local pride. The battle was painted in 1836 by a leading Romanticist painter

Amid that resurgence, the Battle of the Golden Spurs became the subject of an "extensive cult" in 19th- and 20th-century Flanders. After Belgian independence in 1830, the Flemish victory was interpreted as a symbol of local pride. The battle was painted in 1836 by a leading Romanticist painter Nicaise de Keyser

Nicaise de Keyser (alternative first names: Nicaas, Nikaas of Nicasius; 26 August 1813, Zandvliet – 17 July 1887, Antwerp) was a Belgian painter of mainly history paintings and portraits who was one of the key figures in the Belgian Romantic-h ...

. Probably inspired by the painting, the Flemish writer Hendrik Conscience used it as the centerpiece of his classic 1838 novel, '' The Lion of Flanders'' ('''') which brought the events to a mass audience for the first time. It inspired an engraving by the artist James Ensor in 1895. A large monument and triumphal arch

A triumphal arch is a free-standing monumental structure in the shape of an archway with one or more arched passageways, often designed to span a road. In its simplest form a triumphal arch consists of two massive piers connected by an arch, cr ...

were also subsequently erected on the site of the battle between 1906 and 1908. The battle was evoked by King Albert I at the start of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

to inspire bravery among Flemish soldiers as an equivalent of the Walloon six hundred Franchimontois of 1468. In 1914, the Belgian victory against German cavalry at the Battle of Halen was dubbed the "Battle of the Silver Helmets" in analogy to the Golden Spurs. Its anniversary, 11 July, became an important annual Flemish observance. In 1973, the date was formalised as the official holiday of the Flemish Community

The Flemish Community ( nl, Vlaamse Gemeenschap ; french: Communauté flamande ; german: Flämische Gemeinschaft ) is one of the three institutional communities of Belgium, established by the Belgian constitution and having legal responsibilitie ...

.

As the Battle of the Golden Spurs became an important part of Flemish identity, it became increasingly important within the Flemish Movement. Emerging in the 1860s, it sought autonomy or even independence for Flemish (Dutch)-speaking Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to cultu ...

and became increasingly radical after World War I. The battle was seen as a "milestone" in a historic struggle for Flemish national liberation and a symbol of resistance to foreign rule. Flemish nationalists wrote poems and songs about the battle and celebrated its leaders. As a result of that linguistic-based nationalism, the contribution of French-speaking soldiers and command of the battle by the Walloon noble Guy of Namur

Guy of Dampierre, Count of Zeeland, also called Guy of Namur ( nl, region=BE, Gwijde van Namen, label=Flemish) (ca. 1272 – 13 October 1311 in Pavia), was a Flemish noble who was the Lord of Ronse and later the self-proclaimed Count of Zeeland ...

was neglected.

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * *Further reading

* *External links

Liebaart.org

{{DEFAULTSORT:Golden Spurs, Battle of The Battles of the Middle Ages 14th century in the county of Flanders Battle of the Golden Spurs Battles involving Flanders Battles involving France Battles in Flanders 1302 in Europe 1300s in France Conflicts in 1302 Franco-Flemish War