Battle of Ticonderoga (1759) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Battle of Ticonderoga was a minor confrontation at Fort Carillon (later renamed Fort Ticonderoga) on July 26 and 27, 1759, during the

When Amherst learned through Sir William Johnson that the Iroquois League was prepared to support British efforts to drive the French out of their frontier forts, he decided to send an expedition to capture Fort Niagara. Jennings (1988), pp. 414–415 He sent 2,000 of the provincials west from Albany along with 3,000 regular troops under Brigadier General John Prideaux in May. He led the remainder of the provincials, consisting primarily of Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Connecticut men, north to Fort Edward, where they joined 6,000 regular troops (about 2,000 Royal Highlanders, as well as the 17th, 27th, and 53rd regiments of foot, the 1st Battalion of the 60th Foot, about 100

When Amherst learned through Sir William Johnson that the Iroquois League was prepared to support British efforts to drive the French out of their frontier forts, he decided to send an expedition to capture Fort Niagara. Jennings (1988), pp. 414–415 He sent 2,000 of the provincials west from Albany along with 3,000 regular troops under Brigadier General John Prideaux in May. He led the remainder of the provincials, consisting primarily of Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Connecticut men, north to Fort Edward, where they joined 6,000 regular troops (about 2,000 Royal Highlanders, as well as the 17th, 27th, and 53rd regiments of foot, the 1st Battalion of the 60th Foot, about 100

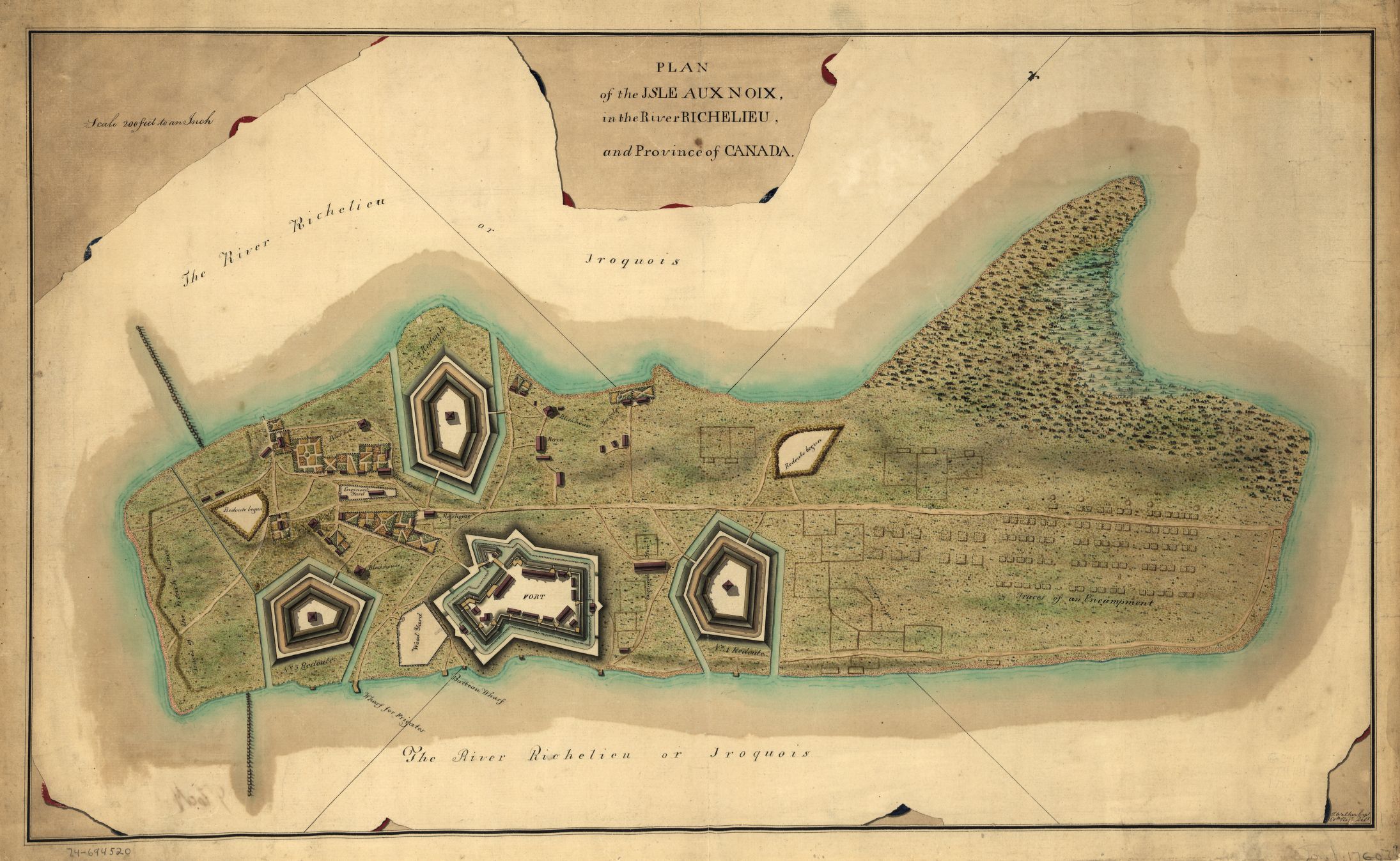

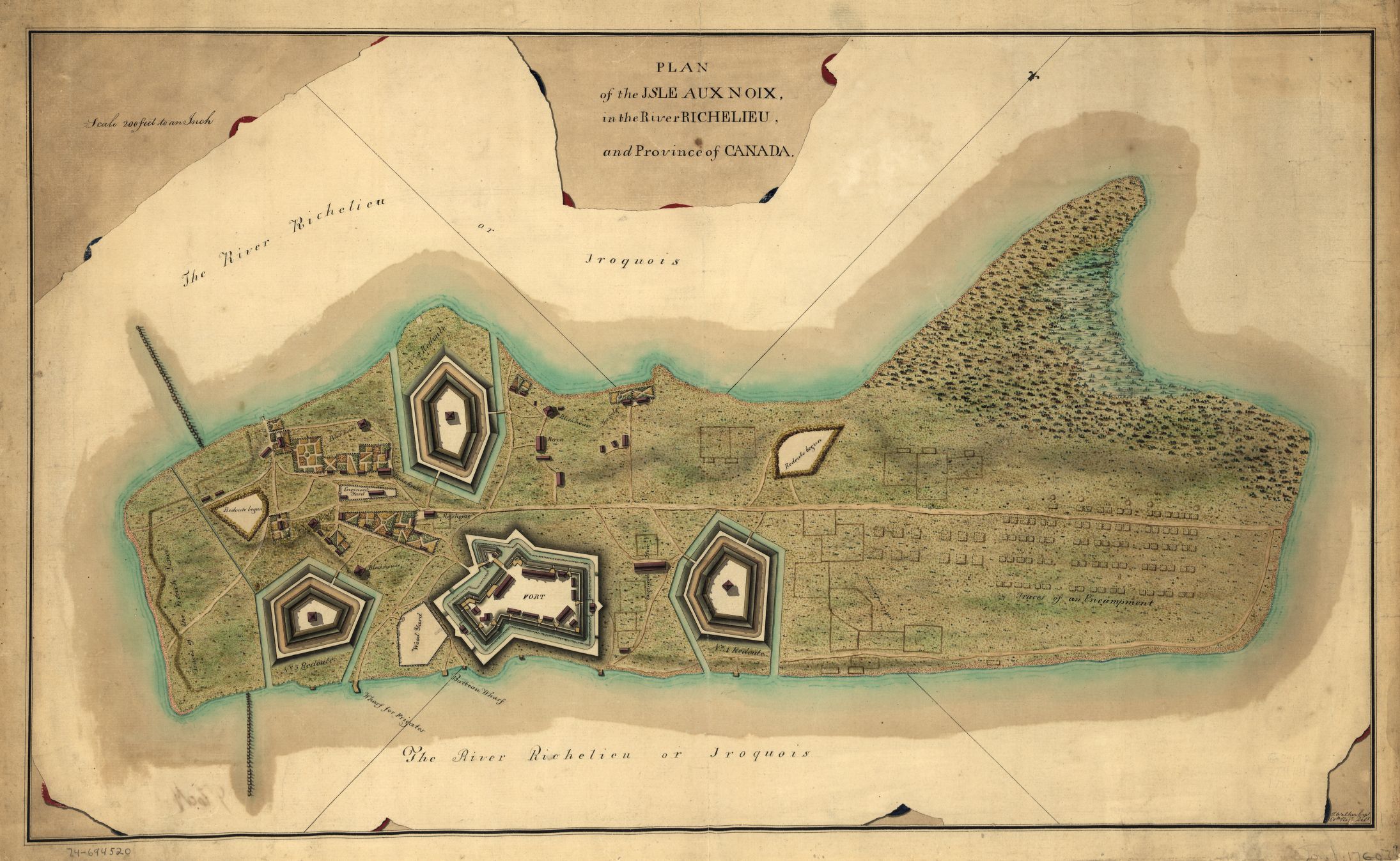

On October 11, Amherst's army began to sail and row north on Lake Champlain to attack Bourlamaque's position at the Île-aux-Noix in the Richelieu River. Over the next two days, one of the French ships was captured; the French abandoned and burned the others to prevent their capture. Kingsford (1890), p. 345 On October 18, he received word of Quebec's fall. As there was an "appearance of winter" (parts of the lake were beginning to freeze), and provincial militia enlistments were set to end on November 1, Amherst called off his attack, dismissed his militia forces, and returned the army to winter quarters. Anderson (2000), pp. 369–370 Kingsford (1890), pp. 344–345

The British definitively gained control of Canada with the surrender of Montreal in 1760. Parkman (1898), volume 2, p. 388 Fort Carillon, which had always been called ''Ticonderoga'' by the British (after the place where the fort is located), McLynn (2004), p. 43 was held by them through the end of the French and Indian War. Following that war, it was manned by small garrisons until 1775, when it was captured by American militia early in the

On October 11, Amherst's army began to sail and row north on Lake Champlain to attack Bourlamaque's position at the Île-aux-Noix in the Richelieu River. Over the next two days, one of the French ships was captured; the French abandoned and burned the others to prevent their capture. Kingsford (1890), p. 345 On October 18, he received word of Quebec's fall. As there was an "appearance of winter" (parts of the lake were beginning to freeze), and provincial militia enlistments were set to end on November 1, Amherst called off his attack, dismissed his militia forces, and returned the army to winter quarters. Anderson (2000), pp. 369–370 Kingsford (1890), pp. 344–345

The British definitively gained control of Canada with the surrender of Montreal in 1760. Parkman (1898), volume 2, p. 388 Fort Carillon, which had always been called ''Ticonderoga'' by the British (after the place where the fort is located), McLynn (2004), p. 43 was held by them through the end of the French and Indian War. Following that war, it was manned by small garrisons until 1775, when it was captured by American militia early in the

Fort Ticonderoga National Historic Landmark

250th Anniversary Commemorations of 1759 in the French and Indian War

including the unrestored 1759 map of Ticonderoga

Crown Point Road

– site about Amherst's supply road between Crown Point and the Fort at Number 4

Haldimand Collection

– Index of documents between Amherst and Frederick Haldimand, second in command of Prideaux's expedition {{DEFAULTSORT:Battle Of Ticonderoga (1759) Conflicts in 1759 Ticonderoga 1759 Ticonderoga 1759 Ticonderoga 1759 Pre-statehood history of New York (state) 1759 in the Province of New York William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham

French and Indian War

The French and Indian War, 1754 to 1763, was a colonial conflict in North America between Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of France, France, along with their respective Native Americans in the United States, Native American ...

. A British military force of more than 11,000 men under the command of General Sir Jeffery Amherst moved artillery to high ground overlooking the fort, which was defended by a garrison of 400 Frenchmen under the command of Brigadier General François-Charles de Bourlamaque.

Rather than defend the fort, de Bourlamaque, operating under instructions from General Louis-Joseph de Montcalm and New France

New France (, ) was the territory colonized by Kingdom of France, France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Kingdom of Great Br ...

's governor

A governor is an politician, administrative leader and head of a polity or Region#Political regions, political region, in some cases, such as governor-general, governors-general, as the head of a state's official representative. Depending on the ...

, the Marquis de Vaudreuil The Marquis de Vaudreuil may refer to:

* Philippe de Rigaud de Vaudreuil (1643–1702), governor of Montréal then of New France

* Pierre de Rigaud de Vaudreuil (1698–1778), last governor-general of New France

* Louis-Philippe de Rigaud, Marquis o ...

, withdrew his forces, and attempted to blow up the fort. The fort's powder magazine was destroyed, but its walls were not severely damaged. The British then occupied the fort, which was afterwards known by the name Fort Ticonderoga. They embarked on a series of improvements to the area and began construction of a fleet to conduct military operations on Lake Champlain

Lake Champlain ( ; , ) is a natural freshwater lake in North America. It mostly lies between the U.S. states of New York (state), New York and Vermont, but also extends north into the Canadian province of Quebec.

The cities of Burlington, Ve ...

.

The French tactics were sufficient to prevent Amherst's army from joining James Wolfe at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham. However, they also tied up 3,000 of their own troops that were not able to assist in Quebec's defense. The capture of the fort, which had previously repulsed a large British army a year earlier, contributed to what the British called the " Annus Mirabilis" of 1759.

Background

TheFrench and Indian War

The French and Indian War, 1754 to 1763, was a colonial conflict in North America between Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of France, France, along with their respective Native Americans in the United States, Native American ...

, which started in 1754 over territorial disputes in what are now western Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

and upstate New York, had finally turned in the favor of the British in 1758 following a string of defeats in 1756 and 1757. The British were successful in capturing Louisbourg and Fort Frontenac in 1758. The only significant French victory in 1758 came when a large British army commanded by James Abercrombie was defeated by a smaller French force in the Battle of Carillon. During the following winter, French commanders withdrew most of the garrison

A garrison is any body of troops stationed in a particular location, originally to guard it. The term now often applies to certain facilities that constitute a military base or fortified military headquarters.

A garrison is usually in a city ...

from Fort Carillon (called Ticonderoga by the British) to defend Quebec City

Quebec City is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Quebec. As of July 2021, the city had a population of 549,459, and the Census Metropolitan Area (including surrounding communities) had a populati ...

, Montreal

Montreal is the List of towns in Quebec, largest city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Quebec, the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-largest in Canada, and the List of North American cit ...

and French-controlled forts on the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes spanning the Canada–United States border. The five lakes are Lake Superior, Superior, Lake Michigan, Michigan, Lake Huron, H ...

and the Saint Lawrence River. Atherton (1914), pp. 416–419

Carillon, located near the southern end of Lake Champlain

Lake Champlain ( ; , ) is a natural freshwater lake in North America. It mostly lies between the U.S. states of New York (state), New York and Vermont, but also extends north into the Canadian province of Quebec.

The cities of Burlington, Ve ...

, occupied a place that was strategic in importance even before Samuel de Champlain

Samuel de Champlain (; 13 August 1574#Fichier]For a detailed analysis of his baptismal record, see #Ritch, RitchThe baptism act does not contain information about the age of Samuel, neither his birth date nor his place of birth. – 25 December ...

discovered it in 1609, controlling access to a key portage trail between Champlain and Lake George along the main travel route between the Hudson River valley and the Saint Lawrence River. Lonergan (1959), pp. 2–8 When the war began, the area was part of the frontier

A frontier is a political and geographical term referring to areas near or beyond a boundary.

Australia

The term "frontier" was frequently used in colonial Australia in the meaning of country that borders the unknown or uncivilised, th ...

between the British province of New York

The Province of New York was a British proprietary colony and later a royal colony on the northeast coast of North America from 1664 to 1783. It extended from Long Island on the Atlantic, up the Hudson River and Mohawk River valleys to ...

and the French province of Canada

The Province of Canada (or the United Province of Canada or the United Canadas) was a British colony in British North America from 1841 to 1867. Its formation reflected recommendations made by John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham, in the Report ...

, and the British had stopped French advances further south in the 1755 Battle of Lake George. Parkman (1914), volume 1, pp. 305–308 However, the fort was constructed in a difficult location: in order to build on rock, the French had sited it relatively far from the lake, while it was still below nearby hilltops.See Chartrand, Rene (2008). The Forts of New France in Northeast America 1600–1763. New York: Osprey Publishing, p. 36.

British planning

For the 1759 campaign, British secretary of state, William Pitt, ordered General Jeffery Amherst, the victor at Louisbourg, to lead an army intoCanada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

by sailing north on Lake Champlain, while a second force under James Wolfe, who distinguished himself while serving under Amherst at Louisbourg, was targeted at the city of Quebec via the Saint Lawrence. Instructions were sent to the governors of the Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies were the British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America which broke away from the British Crown in the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), and joined to form the United States of America.

The Thirteen C ...

to raise up 20,000 provincial militia

A militia ( ) is a military or paramilitary force that comprises civilian members, as opposed to a professional standing army of regular, full-time military personnel. Militias may be raised in times of need to support regular troops or se ...

for these campaigns. Anderson (2000), p. 310 About 8,000 provincial men were raised and sent to Albany by provinces as far south as Pennsylvania and New Jersey. New York sent 3,000 men and New Jersey

New Jersey is a U.S. state, state located in both the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. Located at the geographic hub of the urban area, heavily urbanized Northeas ...

sent 1,000. Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

mustered 6,500 men; about 3,500 went to Albany, while the remainder were dispatched for service with Wolfe at Quebec or other service in Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada, located on its east coast. It is one of the three Maritime Canada, Maritime provinces and Population of Canada by province and territory, most populous province in Atlan ...

. Hutchinson (1828), p. 78 The balance of the provincial men came from the other New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

provinces and Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

. When Quaker Pennsylvania balked at sending any men, Amherst convinced them to raise men by threatening to withdraw troops from forts in the Ohio River

The Ohio River () is a river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing in a southwesterly direction from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to its river mouth, mouth on the Mississippi Riv ...

Valley on the province's western frontier

A frontier is a political and geographical term referring to areas near or beyond a boundary.

Australia

The term "frontier" was frequently used in colonial Australia in the meaning of country that borders the unknown or uncivilised, th ...

, which were regularly subjected to threats from Indians and the French. Bradley (1902), p. 338

When Amherst learned through Sir William Johnson that the Iroquois League was prepared to support British efforts to drive the French out of their frontier forts, he decided to send an expedition to capture Fort Niagara. Jennings (1988), pp. 414–415 He sent 2,000 of the provincials west from Albany along with 3,000 regular troops under Brigadier General John Prideaux in May. He led the remainder of the provincials, consisting primarily of Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Connecticut men, north to Fort Edward, where they joined 6,000 regular troops (about 2,000 Royal Highlanders, as well as the 17th, 27th, and 53rd regiments of foot, the 1st Battalion of the 60th Foot, about 100

When Amherst learned through Sir William Johnson that the Iroquois League was prepared to support British efforts to drive the French out of their frontier forts, he decided to send an expedition to capture Fort Niagara. Jennings (1988), pp. 414–415 He sent 2,000 of the provincials west from Albany along with 3,000 regular troops under Brigadier General John Prideaux in May. He led the remainder of the provincials, consisting primarily of Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Connecticut men, north to Fort Edward, where they joined 6,000 regular troops (about 2,000 Royal Highlanders, as well as the 17th, 27th, and 53rd regiments of foot, the 1st Battalion of the 60th Foot, about 100 Royal Artillery

The Royal Regiment of Artillery, commonly referred to as the Royal Artillery (RA) and colloquially known as "The Gunners", is one of two regiments that make up the artillery arm of the British Army. The Royal Regiment of Artillery comprises t ...

, 700 of Rogers' Rangers, and 500 light infantry

Light infantry refers to certain types of lightly equipped infantry throughout history. They have a more mobile or fluid function than other types of infantry, such as heavy infantry or line infantry. Historically, light infantry often fought ...

under Thomas Gage). Kingsford (1890), p. 331 contains a copy of Amherst's troop returns.

French planning

In the 1759 campaign, French war planners directed most of their war resources into the European theater of theSeven Years' War

The Seven Years' War, 1756 to 1763, was a Great Power conflict fought primarily in Europe, with significant subsidiary campaigns in North America and South Asia. The protagonists were Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of Prus ...

. In February, France's war minister, Marshal Belle-Isle, notified General Louis-Joseph de Montcalm, who was responsible for the defense of Canada, that he would not receive any significant support from France, due in large part to English naval domination of the Atlantic and the risks associated with sending a large military force under those circumstances. Belle-Isle impressed on Montcalm the importance of maintaining at least a foothold in North America, as the territory would be virtually impossible to retake otherwise. Montcalm responded, "Unless we have unexpected luck, or stage a diversion elsewhere within North America, Canada will fall during the coming campaign season. The English have 60,000 men, we have 11,000." McLynn (2004), p. 135

Montcalm decided to focus French manpower on defending the core territory of Canada: Montreal

Montreal is the List of towns in Quebec, largest city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Quebec, the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-largest in Canada, and the List of North American cit ...

, the city of Quebec, and the Saint Lawrence River Valley. He placed 3,000 troops from the la Reine and Berry

A berry is a small, pulpy, and often edible fruit. Typically, berries are juicy, rounded, brightly colored, sweet, sour or tart, and do not have a stone or pit although many pips or seeds may be present. Common examples of berries in the cul ...

regiments under Brigadier General François-Charles de Bourlamaque for the defense south of Montreal, of which around 2,300 were assigned to Fort Carillon. Parkman (1898), volume 2, p. 248 Reid (2003), pp. 22, 44 He knew (after his own experience in the previous year's battle there) that this force was too small to hold Carillon against a determined attack by a force with competent leaders. Parkman (1898), volume 2, p. 185 Instructions from Montcalm and New France

New France (, ) was the territory colonized by Kingdom of France, France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Kingdom of Great Br ...

's governor, the Marquis de Vaudreuil The Marquis de Vaudreuil may refer to:

* Philippe de Rigaud de Vaudreuil (1643–1702), governor of Montréal then of New France

* Pierre de Rigaud de Vaudreuil (1698–1778), last governor-general of New France

* Louis-Philippe de Rigaud, Marquis o ...

, to de Bourlamaque were to hold Carillon as long as possible, then to destroy it, as well as the nearby Fort St. Frédéric, before retreating toward Montreal. McLynn (2004), p. 154

British advance and French retreat

Although General Amherst had been ordered to move his forces "as early in the year, as on or about, the 7th of May, if the season shall happen to permit", Amherst's army of 11,000 did not leave the southern shores of Lake George until July 21. There were several reasons for the late departure. One was logistical; Prideaux's expedition to forts Oswego and Niagara also departed from Albany; Anderson (2000), p. 340 another was the slow arrival of provincial militias. McLynn (2004), p. 146 When his troops landed and began advancing on the fort, Amherst was pleased to learn that the French had abandoned the outer defenses. He still proceeded with caution, occupying the old French lines from the 1758 battle on July 22, amid reports that the French were actively loading bateaux at the fort. Kingsford (1890), p. 332 His original plan had been to flank the fort, denying the road to Fort St. Frédéric as a means of French escape. In the absence of French resistance outside the fort, he decided instead to focus his attention on the fort itself. Hamilton (1964), p. 94 For the next three days, the British entrenched and began layingsiege

A siege () . is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or by well-prepared assault. Siege warfare (also called siegecrafts or poliorcetics) is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict charact ...

lines to establish positions near the fort. This work was complicated by the fact there was little diggable ground near the fort, and sandbags were required to protect the siege works. During this time, the French gun batteries fired, at times quite heavily, on the British positions. On July 25, a detachment of Rogers' Rangers launched some boats onto the lake north of the fort and cut a log boom the French had placed to prevent ships from moving further north on the lake. Hamilton (1964), p. 96 Kingsford (1890), p. 333 By July 26, the British had pulled artillery to within of the fort's walls. Anderson (2000), p. 342

Bourlamaque had withdrawn with all but 400 of his men to Fort St. Frédéric as soon as he learned that the British were approaching. The cannon fire by this small force killed five and wounded another 31 of the besieging British. Captain Louis-Philippe Le Dossu d'Hébécourt, who had been left in command of the fort, judged on the evening of July 26 that it was time to leave. His men aimed the fort's guns at its walls, laid mines, and put down a powder trail to the overstocked powder magazine. They then lit the fuse and abandoned the fort, leaving the French flag flying. The British were notified of this action by the arrival of French deserters. General Amherst offered 100 guineas

The guinea (; commonly abbreviated gn., or gns. in plural) was a coin, minted in Great Britain between 1663 and 1814, that contained approximately one-quarter of an ounce of gold. The name came from the Guinea region in West Africa, from where m ...

to any man willing to enter the works to find and douse the fuse; but no one was willing to take up the offer. Hamilton (1964), p. 97 The entire works went off late that evening with a tremendous roar. The powder magazine was destroyed, and a number of wooden structures caught fire due to flying embers, but the fort's walls were not badly damaged. McLynn (2004), pp. 154–155 After the explosion, some of Gage's light infantry rushed into the fort and retrieved the French flag. Fires in the fort were not entirely extinguished for two days. Kingsford (1890), p. 334

Aftermath

The British began occupying the fort the next day. In one consequence of the French forces' hasty departure from Carillon, one of their scouting parties returned to the fort, believing it to still be in French hands; forty men were taken prisoner. The retreating French destroyed Fort St. Frédéric on July 31, leaving the way clear for the British to begin military operations on Lake Champlain (denying the British access to Champlain had been the reason for the existence of both forts). However, the French had a small armed fleet, which would first need to be neutralized. Bradley (1902), p. 340 The time needed to capture and effect some repairs to the two forts, as well as the need to build ships for use on Lake Champlain, delayed Amherst's forces further and prevented him from joining General Wolfe at the siege of Quebec. McLynn (2004), p. 155 Amherst, worried that Bourlamaque's retreat might be leading him into a trap, spent August and September overseeing the construction of a small navy, Fort Crown Point (a new fort next to the ruins of Fort St. Frédéric), and supply roads to the area from New England. Anderson (2000), p. 343 On October 11, Amherst's army began to sail and row north on Lake Champlain to attack Bourlamaque's position at the Île-aux-Noix in the Richelieu River. Over the next two days, one of the French ships was captured; the French abandoned and burned the others to prevent their capture. Kingsford (1890), p. 345 On October 18, he received word of Quebec's fall. As there was an "appearance of winter" (parts of the lake were beginning to freeze), and provincial militia enlistments were set to end on November 1, Amherst called off his attack, dismissed his militia forces, and returned the army to winter quarters. Anderson (2000), pp. 369–370 Kingsford (1890), pp. 344–345

The British definitively gained control of Canada with the surrender of Montreal in 1760. Parkman (1898), volume 2, p. 388 Fort Carillon, which had always been called ''Ticonderoga'' by the British (after the place where the fort is located), McLynn (2004), p. 43 was held by them through the end of the French and Indian War. Following that war, it was manned by small garrisons until 1775, when it was captured by American militia early in the

On October 11, Amherst's army began to sail and row north on Lake Champlain to attack Bourlamaque's position at the Île-aux-Noix in the Richelieu River. Over the next two days, one of the French ships was captured; the French abandoned and burned the others to prevent their capture. Kingsford (1890), p. 345 On October 18, he received word of Quebec's fall. As there was an "appearance of winter" (parts of the lake were beginning to freeze), and provincial militia enlistments were set to end on November 1, Amherst called off his attack, dismissed his militia forces, and returned the army to winter quarters. Anderson (2000), pp. 369–370 Kingsford (1890), pp. 344–345

The British definitively gained control of Canada with the surrender of Montreal in 1760. Parkman (1898), volume 2, p. 388 Fort Carillon, which had always been called ''Ticonderoga'' by the British (after the place where the fort is located), McLynn (2004), p. 43 was held by them through the end of the French and Indian War. Following that war, it was manned by small garrisons until 1775, when it was captured by American militia early in the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

. Lonergan (1959), pp. 56–59

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* A copiously detailed account of the British movements. * * Contains a report by British military engineer John Montresor detailing his suggested plan of attack on Ticonderoga. * A lengthy poem by Robert Louis Stevenson about the legend of Ticonderoga.External links

Fort Ticonderoga National Historic Landmark

250th Anniversary Commemorations of 1759 in the French and Indian War

including the unrestored 1759 map of Ticonderoga

Crown Point Road

– site about Amherst's supply road between Crown Point and the Fort at Number 4

Haldimand Collection

– Index of documents between Amherst and Frederick Haldimand, second in command of Prideaux's expedition {{DEFAULTSORT:Battle Of Ticonderoga (1759) Conflicts in 1759 Ticonderoga 1759 Ticonderoga 1759 Ticonderoga 1759 Pre-statehood history of New York (state) 1759 in the Province of New York William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham