Battle of Ticinus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The battle of Ticinus was fought between the Carthaginian forces of

The

The

Meanwhile, Hannibal assembled a Carthaginian army in New Carthage (modern Cartagena) over the winter, marching north in May 218 BC. He entered

Meanwhile, Hannibal assembled a Carthaginian army in New Carthage (modern Cartagena) over the winter, marching north in May 218 BC. He entered  Hearing that Publius Scipio was operating in the region, he assumed the Roman army in Massala which he had believed en route to Iberia had returned to Italy and reinforced the army already based in the north. Believing he would therefore be facing a much larger Roman force than he had anticipated, Hannibal felt an even more pressing need to recruit strongly among the Cisalpine Gauls. He determined that a display of confidence was called for and advanced boldly down the valley of the Po. However, Scipio led his army equally boldly against the Carthaginians, causing the Gauls to remain neutral. Both commanders attempted to inspire the ardour of their men for the coming battle by making fiery speeches to their assembled armies. Hannibal is reported to have stressed to his troops that they had to win, whatever the cost, as there was no place they could retreat to.

After camping at

Hearing that Publius Scipio was operating in the region, he assumed the Roman army in Massala which he had believed en route to Iberia had returned to Italy and reinforced the army already based in the north. Believing he would therefore be facing a much larger Roman force than he had anticipated, Hannibal felt an even more pressing need to recruit strongly among the Cisalpine Gauls. He determined that a display of confidence was called for and advanced boldly down the valley of the Po. However, Scipio led his army equally boldly against the Carthaginians, causing the Gauls to remain neutral. Both commanders attempted to inspire the ardour of their men for the coming battle by making fiery speeches to their assembled armies. Hannibal is reported to have stressed to his troops that they had to win, whatever the cost, as there was no place they could retreat to.

After camping at

Anticipating an engagement as he closed with the Romans, Hannibal had recalled all of his scouts and raiding parties and took with him an exclusively cavalry force which included almost all of his 6,000-strong mounted contingent. Carthage usually recruited foreigners to make up its army. Many were from North Africa, and are usually referred to as Libyans; the region provided two main types of cavalry: close-order shock cavalry (also known as "

Anticipating an engagement as he closed with the Romans, Hannibal had recalled all of his scouts and raiding parties and took with him an exclusively cavalry force which included almost all of his 6,000-strong mounted contingent. Carthage usually recruited foreigners to make up its army. Many were from North Africa, and are usually referred to as Libyans; the region provided two main types of cavalry: close-order shock cavalry (also known as "

Hannibal placed his cavalry in a line with the close-order formations in the centre. The more manoeuvrable

Hannibal placed his cavalry in a line with the close-order formations in the centre. The more manoeuvrable

The Romans withdrew as far as Piacenza. Two days after Ticinus the Carthaginians crossed the River Po, and then marched to Piacenza. They formed up outside the Roman camp and offered battle, which Scipio refused. The Carthaginians set up their own camp some away. That night 2,200 Gallic troops serving with the Roman army attacked the Romans closest to them in their tents, and deserted to the Carthaginians; taking the Romans' heads with them as a sign of good faith. Hannibal rewarded them and sent them back to their homes to enrol more recruits. Hannibal also made his first formal treaty with a Gallic tribe, and supplies and recruits started to come in. The Romans abandoned their camp and withdrew under cover of night. The next morning the Carthaginian cavalry bungled their pursuit and the Romans were able to set up camp on an area of high ground by the River Trebia at what is now

The Romans withdrew as far as Piacenza. Two days after Ticinus the Carthaginians crossed the River Po, and then marched to Piacenza. They formed up outside the Roman camp and offered battle, which Scipio refused. The Carthaginians set up their own camp some away. That night 2,200 Gallic troops serving with the Roman army attacked the Romans closest to them in their tents, and deserted to the Carthaginians; taking the Romans' heads with them as a sign of good faith. Hannibal rewarded them and sent them back to their homes to enrol more recruits. Hannibal also made his first formal treaty with a Gallic tribe, and supplies and recruits started to come in. The Romans abandoned their camp and withdrew under cover of night. The next morning the Carthaginian cavalry bungled their pursuit and the Romans were able to set up camp on an area of high ground by the River Trebia at what is now

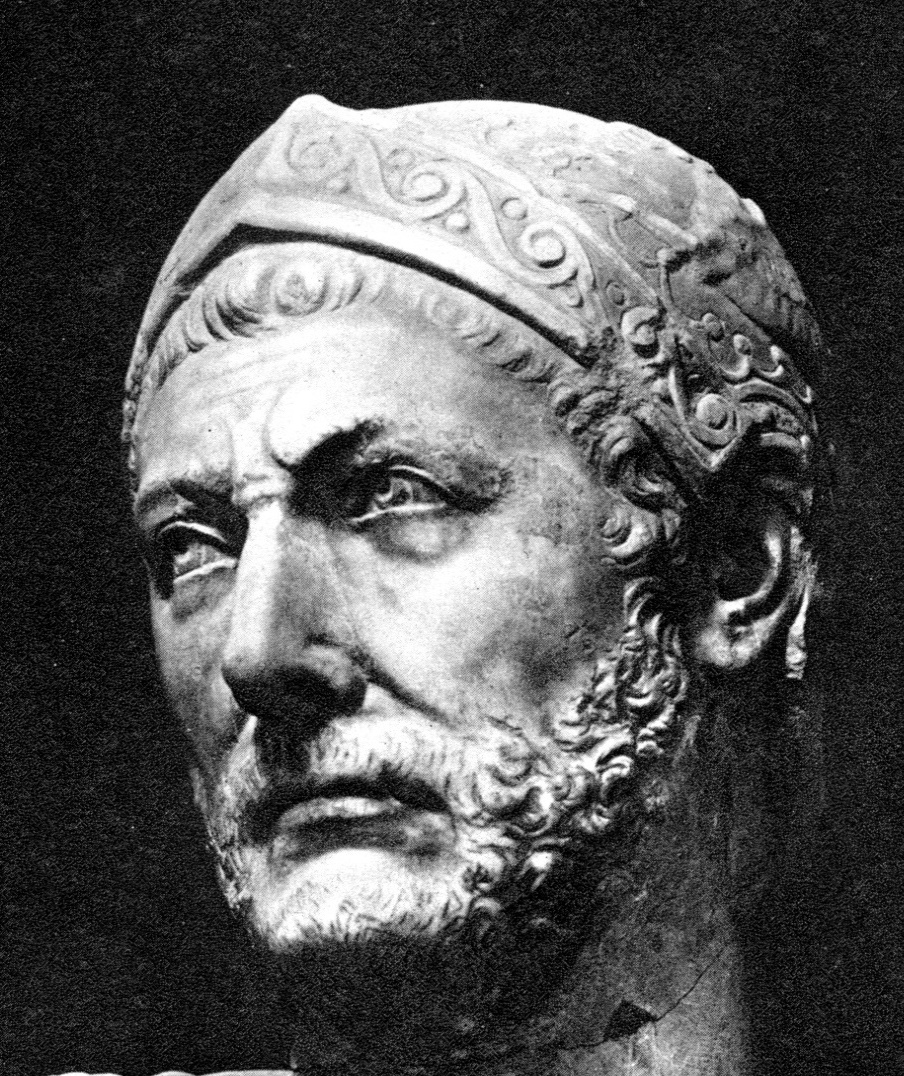

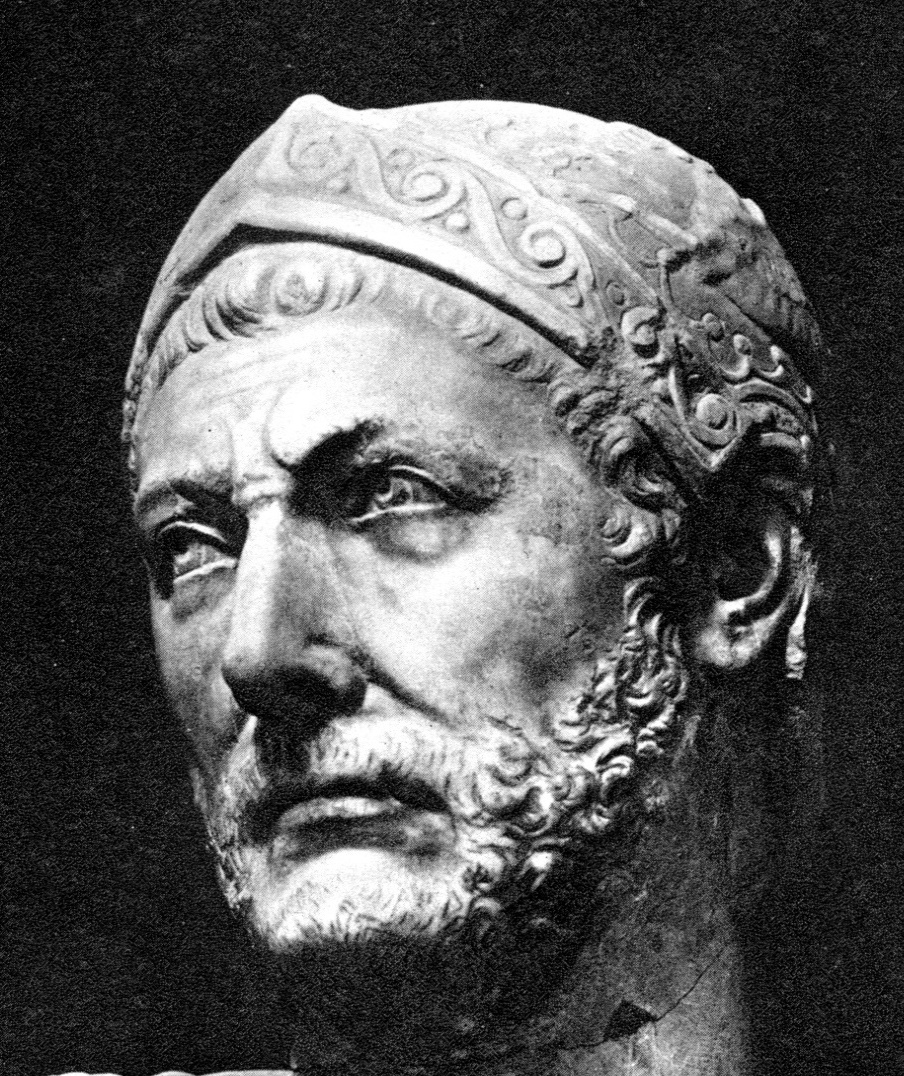

Hannibal

Hannibal (; xpu, 𐤇𐤍𐤁𐤏𐤋, ''Ḥannibaʿl''; 247 – between 183 and 181 BC) was a Carthaginian general and statesman who commanded the forces of Carthage in their battle against the Roman Republic during the Second Pu ...

and a Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lett ...

army under Publius Cornelius Scipio in late November 218 BC as part of the Second Punic War

The Second Punic War (218 to 201 BC) was the second of three wars fought between Carthage and Rome, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean in the 3rd century BC. For 17 years the two states struggled for supremacy, primarily in Ital ...

. It took place in the flat country on the right bank of the River Ticinus, to the west of modern Pavia

Pavia (, , , ; la, Ticinum; Medieval Latin: ) is a town and comune of south-western Lombardy in northern Italy, south of Milan on the lower Ticino river near its confluence with the Po. It has a population of c. 73,086. The city was the ...

in northern Italy. Hannibal led 6,000 Libyan

Demographics of Libya is the demography of Libya, specifically covering population density, ethnicity, education level, health of the populace, economic status, and religious affiliations, as well as other aspects of the Libyan population. The ...

and Iberian cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry in ...

, while Scipio led 3,600 Roman, Italian and Gallic cavalry and a large but unknown number of light infantry

Light infantry refers to certain types of lightly equipped infantry throughout history. They have a more mobile or fluid function than other types of infantry, such as heavy infantry or line infantry. Historically, light infantry often foug ...

javelin

A javelin is a light spear designed primarily to be thrown, historically as a ranged weapon, but today predominantly for sport. The javelin is almost always thrown by hand, unlike the sling, bow, and crossbow, which launch projectiles with the ...

men.

War had been declared early in 218 BC over perceived infringements of Roman prerogatives in Iberia (modern Spain and Portugal) by Hannibal. Hannibal had gathered a large army, marched out of Iberia, through Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

(modern France) and over the Alps into Cisalpine Gaul

Cisalpine Gaul ( la, Gallia Cisalpina, also called ''Gallia Citerior'' or ''Gallia Togata'') was the part of Italy inhabited by Celts ( Gauls) during the 4th and 3rd centuries BC.

After its conquest by the Roman Republic in the 200s BC it was ...

(northern Italy), where many of the local tribes were opposed to Rome. The Romans were taken by surprise, but one of the consuls

A consul is an official representative of the government of one state in the territory of another, normally acting to assist and protect the citizens of the consul's own country, as well as to facilitate trade and friendship between the people ...

for the year, Scipio, led an army along the north bank of the Po with the intention of giving battle to Hannibal. The two commanding generals each led out strong forces to reconnoitre their opponents. Scipio mixed many javelinmen with his main cavalry force, anticipating a large-scale skirmish. Hannibal put his close-order cavalry in the centre of his line, with his light Numidian cavalry

Numidian cavalry was a type of light cavalry developed by the Numidians. After they were used by Hannibal during the Second Punic War, they were described by the Roman historian Livy as "by far the best horsemen in Africa."

History

Numidian cava ...

on the wings. On sighting the Roman infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and mar ...

the Carthaginian centre immediately charged and the javelinmen fled back through the ranks of their cavalry. A large cavalry melee

A melee ( or , French: mêlée ) or pell-mell is disorganized hand-to-hand combat in battles fought at abnormally close range with little central control once it starts. In military aviation, a melee has been defined as " air battle in which ...

ensued: many cavalry dismounted to fight on foot and some of the Roman javelinmen reinforced the fighting line. This continued indecisively until the Numidians swept round both ends of the line of battle. They then attacked the still disorganised javelinmen; the small Roman cavalry reserve, to which Scipio had attached himself; and the rear of the already engaged Roman cavalry. All three of these Roman forces were thrown into confusion and panic.

The Romans broke and fled, with heavy casualties. Scipio was wounded and only saved from death or capture by his 16-year-old son. That night Scipio broke camp and retreated over the Ticinus; the Carthaginians captured 600 of his rearguard the next day. After further manoeuvres Scipio established himself in a fortified camp to await reinforcements while Hannibal recruited among the local Gauls. When the Roman reinforcements arrived in December under Tiberius Longus, Hannibal heavily defeated him at the battle of the Trebia

The Battle of the Trebia (or Trebbia) was the first major battle of the Second Punic War, fought between the Carthaginian forces of Hannibal and a Roman army under Sempronius Longus on 22 or 23 December 218 BC. It took place on the flood ...

. The following spring, strongly reinforced by Gallic tribesmen, the Carthaginians moved south into Roman Italy. Hannibal campaigned in southern Italy for the next 12 years.

Background

Iberia

The

The First Punic War

The First Punic War (264–241 BC) was the first of Punic Wars, three wars fought between Roman Republic, Rome and Ancient Carthage, Carthage, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean in the early 3rd century BC. For 23 years ...

was fought between Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classi ...

and Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

in the 3rd century BC. They struggled for supremacy primarily on the Mediterranean island of Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

and its surrounding waters, and also in North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

. The war lasted for 23 years, from 264 to 241 BC, until the Carthaginians were defeated. The Treaty of Lutatius

The Treaty of Lutatius was the agreement between Carthage and Rome of 241 BC (amended in 237 BC), that ended the First Punic War after 23 years of conflict. Most of the fighting during the war took place on, or in the waters around, the islan ...

was signed by which Carthage evacuated Sicily and paid an indemnity

In contract law, an indemnity is a contractual obligation of one Party (law), party (the ''indemnitor'') to Financial compensation, compensate the loss incurred by another party (the ''indemnitee'') due to the relevant acts of the indemnitor or ...

of 3,200 talents over ten years. Four years later, when Carthage was weakened by the mutiny of part of its army and the rebellion of many of its African possessions, Rome seized Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label= Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, aft ...

and Corsica

Corsica ( , Upper , Southern ; it, Corsica; ; french: Corse ; lij, Còrsega; sc, Còssiga) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the 18 regions of France. It is the fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of ...

on a cynical pretence and imposed a further 1,200 talent indemnity. The annexation of Sardinia and Corsica by Rome and the additional financial imposition fuelled resentment in Carthage. The contemporary Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

historian Polybius

Polybius (; grc-gre, Πολύβιος, ; ) was a Greek historian of the Hellenistic period. He is noted for his work , which covered the period of 264–146 BC and the Punic Wars in detail.

Polybius is important for his analysis of the mixed ...

considered this act of bad faith by the Romans to be the single greatest cause of war with Carthage breaking out again nineteen years later.

Shortly after Rome's breach of the treaty the leading Carthaginian general Hamilcar Barca

Hamilcar Barca or Barcas ( xpu, 𐤇𐤌𐤋𐤒𐤓𐤕𐤟𐤁𐤓𐤒, ''Ḥomilqart Baraq''; –228BC) was a Carthaginian general and statesman, leader of the Barcid family, and father of Hannibal, Hasdrubal and Mago. He was also father-i ...

led many of his veterans on an expedition to expand Carthaginian holdings in south-east Iberia

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese language, Aragonese and Occitan language, Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a pe ...

(today Iberia consists of Spain and Portugal); this was to become a quasi-monarchial, autonomous Barcid fiefdom. Carthage gained silver mines, agricultural wealth, manpower

Human resources (HR) is the set of people who make up the workforce of an organization, business sector, industry, or economy. A narrower concept is human capital, the knowledge and skills which the individuals command. Similar terms includ ...

, military facilities such as shipyard

A shipyard, also called a dockyard or boatyard, is a place where ships are built and repaired. These can be yachts, military vessels, cruise liners or other cargo or passenger ships. Dockyards are sometimes more associated with maintenance ...

s, and territorial depth which encouraged it to stand up to future Roman demands. Hamilcar ruled as a viceroy

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory. The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the French word ''roy'', meaning " ...

and was succeeded by his son-in-law, Hasdrubal, in 229BC and then his son, Hannibal

Hannibal (; xpu, 𐤇𐤍𐤁𐤏𐤋, ''Ḥannibaʿl''; 247 – between 183 and 181 BC) was a Carthaginian general and statesman who commanded the forces of Carthage in their battle against the Roman Republic during the Second Pu ...

, eight years later. In 226 BC the Ebro Treaty was agreed with Rome, specifying the Ebro River as the northern boundary of the Carthaginian sphere of influence

In the field of international relations, a sphere of influence (SOI) is a spatial region or concept division over which a state or organization has a level of cultural, economic, military or political exclusivity.

While there may be a formal a ...

. A little later Rome made a separate treaty with the city of Saguntum, which was situated well south of the Ebro. In 218 BC a Carthaginian army under Hannibal besieged, captured and sacked Saguntum and early the following year Rome declared war

A declaration of war is a formal act by which one state announces existing or impending war activity against another. The declaration is a performative speech act (or the signing of a document) by an authorized party of a national government, ...

on Carthage.

Cisalpine Gaul

Since the end of the First Punic War Rome had also been expanding, especially in the area of north Italy either side of theRiver Po

The Po ( , ; la, Padus or ; Ancient Ligurian: or ) is the longest river in Italy. It flows eastward across northern Italy starting from the Cottian Alps. The river's length is either or , if the Maira, a right bank tributary, is included. Th ...

known as Cisalpine Gaul

Cisalpine Gaul ( la, Gallia Cisalpina, also called ''Gallia Citerior'' or ''Gallia Togata'') was the part of Italy inhabited by Celts ( Gauls) during the 4th and 3rd centuries BC.

After its conquest by the Roman Republic in the 200s BC it was ...

. Roman attempts to establish towns and farms in the region from 232 BC led to repeated wars with the local Gallic tribes, who were finally defeated in 222BC. In 218BC the Romans pushed even further north, establishing two new towns, or "colonies", on the Po and appropriating large areas of the best land. Most of the Gauls simmered with resentment at this intrusion. The major Gallic tribes in Cisalpine Gaul attacked the Roman colonies there, causing the Romans to flee to their previously established colony of Mutina (modern Modena

Modena (, , ; egl, label= Modenese, Mòdna ; ett, Mutna; la, Mutina) is a city and '' comune'' (municipality) on the south side of the Po Valley, in the Province of Modena in the Emilia-Romagna region of northern Italy.

A town, and seat o ...

), where they were besieged. A Roman relief army broke through the siege, but was then ambushed and itself besieged in Tannetum.

It was the long-standing Roman procedure to elect two men each year, known as consuls

A consul is an official representative of the government of one state in the territory of another, normally acting to assist and protect the citizens of the consul's own country, as well as to facilitate trade and friendship between the people ...

, to each lead an army. In 218 BC the Romans raised an army to campaign in Iberia under the consul Publius Scipio, who was accompanied by his brother Gnaeus. The Roman Senate

The Roman Senate ( la, Senātus Rōmānus) was a governing and advisory assembly in ancient Rome. It was one of the most enduring institutions in Roman history, being established in the first days of the city of Rome (traditionally founded in ...

detached one Roman and one allied legion from the force intended for Iberia to reinforce the Roman position in northern Italy. The Scipios had to raise fresh troops to replace these and thus could not set out for Iberia until September. At the same time another Roman army in Sicily under the consul Sempronius Longus was preparing for an invasion of Carthaginian Africa.

Carthage invades Italy

Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

to the east of the Pyrenees

The Pyrenees (; es, Pirineos ; french: Pyrénées ; ca, Pirineu ; eu, Pirinioak ; oc, Pirenèus ; an, Pirineus) is a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. It extends nearly from its union with the Cantabrian Mountains to ...

, then took an inland route to avoid the Roman allies along the coast. Hannibal left his brother Hasdrubal Barca in charge of Carthaginian interests in Iberia. The Roman fleet carrying the Scipio brothers' army landed at Rome's ally Massalia (modern Marseille

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Fra ...

) at the mouth of the Rhone in September, at about the same time as Hannibal was fighting his way across the river against a force of local Gauls at the battle of Rhone Crossing. A Roman cavalry patrol scattered a force of Carthaginian cavalry, but Hannibal's main army evaded the Romans and Gnaeus Scipio continued to Iberia with the Roman force; Publius returned to northern Italy to coordinate the immediate Roman response there. The Carthaginians crossed the Alps

The Alps () ; german: Alpen ; it, Alpi ; rm, Alps ; sl, Alpe . are the highest and most extensive mountain range system that lies entirely in Europe, stretching approximately across seven Alpine countries (from west to east): France, Sw ...

with 38,000 infantry and 8,000 cavalry in October 218 BC, surmounting the difficulties of climate, terrain and the guerrilla tactics

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, raids, petty warfare, hit-and-run tacti ...

of the native tribes.

Hannibal arrived with 20,000 infantry, 6,000 cavalry and 37 elephants in what is now Piedmont

it, Piemontese

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

, northern Italy. The Romans had already withdrawn to their winter quarters and were astonished by Hannibal's appearance. His surprise entry into the Italian peninsula led to the cancellation of Rome's planned invasion of Africa by an army under Longus. The Carthaginians needed to obtain supplies of food, as they had exhausted their reserves. They also wished to obtain allies among the north-Italian Gallic tribes from which they could recruit, as Hannibal believed that he required a larger army if he were to effectively take on the Romans. The local tribe, the Taurini, were unwelcoming, so Hannibal promptly besieged their capital, (near the site of modern Turin

Turin ( , Piedmontese language, Piedmontese: ; it, Torino ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in Northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital ...

) stormed it, massacred the population and seized the supplies there. The modern historian Richard Miles believes that with these brutal actions Hannibal was sending out a clear message to the other Gallic tribes as to the likely consequences of non-cooperation.

Hearing that Publius Scipio was operating in the region, he assumed the Roman army in Massala which he had believed en route to Iberia had returned to Italy and reinforced the army already based in the north. Believing he would therefore be facing a much larger Roman force than he had anticipated, Hannibal felt an even more pressing need to recruit strongly among the Cisalpine Gauls. He determined that a display of confidence was called for and advanced boldly down the valley of the Po. However, Scipio led his army equally boldly against the Carthaginians, causing the Gauls to remain neutral. Both commanders attempted to inspire the ardour of their men for the coming battle by making fiery speeches to their assembled armies. Hannibal is reported to have stressed to his troops that they had to win, whatever the cost, as there was no place they could retreat to.

After camping at

Hearing that Publius Scipio was operating in the region, he assumed the Roman army in Massala which he had believed en route to Iberia had returned to Italy and reinforced the army already based in the north. Believing he would therefore be facing a much larger Roman force than he had anticipated, Hannibal felt an even more pressing need to recruit strongly among the Cisalpine Gauls. He determined that a display of confidence was called for and advanced boldly down the valley of the Po. However, Scipio led his army equally boldly against the Carthaginians, causing the Gauls to remain neutral. Both commanders attempted to inspire the ardour of their men for the coming battle by making fiery speeches to their assembled armies. Hannibal is reported to have stressed to his troops that they had to win, whatever the cost, as there was no place they could retreat to.

After camping at Piacenza

Piacenza (; egl, label= Piacentino, Piaṡëinsa ; ) is a city and in the Emilia-Romagna region of northern Italy, and the capital of the eponymous province. As of 2022, Piacenza is the ninth largest city in the region by population, with over ...

, a Roman colony founded earlier that year, the Romans created a pontoon bridge

A pontoon bridge (or ponton bridge), also known as a floating bridge, uses floats or shallow- draft boats to support a continuous deck for pedestrian and vehicle travel. The buoyancy of the supports limits the maximum load that they can carry ...

across the lower River Ticinus (the modern Ticino) and continued west. When his scouts reported the nearby presence of Carthaginians, Scipio ordered his army to encamp. The Carthaginians did the same. Next day each commander led out a strong force to personally reconnoitre the size and make up of the opposing army, about which they would have been almost completely ignorant.

Opposing forces

Anticipating an engagement as he closed with the Romans, Hannibal had recalled all of his scouts and raiding parties and took with him an exclusively cavalry force which included almost all of his 6,000-strong mounted contingent. Carthage usually recruited foreigners to make up its army. Many were from North Africa, and are usually referred to as Libyans; the region provided two main types of cavalry: close-order shock cavalry (also known as "

Anticipating an engagement as he closed with the Romans, Hannibal had recalled all of his scouts and raiding parties and took with him an exclusively cavalry force which included almost all of his 6,000-strong mounted contingent. Carthage usually recruited foreigners to make up its army. Many were from North Africa, and are usually referred to as Libyans; the region provided two main types of cavalry: close-order shock cavalry (also known as "heavy cavalry

Heavy cavalry was a class of cavalry intended to deliver a battlefield charge and also to act as a tactical reserve; they are also often termed '' shock cavalry''. Although their equipment differed greatly depending on the region and histor ...

") carrying spears; and light cavalry skirmisher

Skirmishers are light infantry or light cavalry soldiers deployed as a vanguard, flank guard or rearguard to screen a tactical position or a larger body of friendly troops from enemy advances. They are usually deployed in a skirmish line, an ir ...

s from Numidia

Numidia ( Berber: ''Inumiden''; 202–40 BC) was the ancient kingdom of the Numidians located in northwest Africa, initially comprising the territory that now makes up modern-day Algeria, but later expanding across what is today known as Tunis ...

who threw javelins from a distance and avoided close combat. Iberia also provided experienced cavalry: unarmoured close-order troops referred to by the ancient historian Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding in ...

as "steady", meaning that they were accustomed to sustained hand-to-hand combat rather than hit and run tactics. Hannibal's cavalry contingent would have consisted almost entirely of these three types, but the numbers of each are not known.

Most male Roman citizens were eligible for military service and would serve as infantry, with a better-off minority providing a cavalry component. Traditionally, when at war the Romans would raise two or more legions, each of 4,200 infantry and 300 cavalry. Approximately 1,200 of the infantry in each legion, poorer or younger men unable to afford the armour and equipment of a standard legionary

The Roman legionary (in Latin ''legionarius'', plural ''legionarii'') was a professional heavy infantryman of the Roman army after the Marian reforms. These soldiers would conquer and defend the territories of ancient Rome during the late Republ ...

, served as javelin

A javelin is a light spear designed primarily to be thrown, historically as a ranged weapon, but today predominantly for sport. The javelin is almost always thrown by hand, unlike the sling, bow, and crossbow, which launch projectiles with the ...

-armed skirmishers, known as velites

''Velites'' (singular: ) were a class of infantry in the Roman army of the mid-Republic from 211 to 107 BC. ''Velites'' were light infantry and skirmishers armed with javelins ( la, hastae velitares), each with a 75cm (30 inch) wooden shaft the ...

. They carried several javelins, which would be thrown from a distance, a short sword, and a shield. An army was usually formed by combining one or several Roman legions with the same number of similarly sized and equipped legions provided by their Latin allies; allied legions usually had a larger attached complement of cavalry than Roman ones. Scipio's army consisted of four legions, with approximately 16,000 infantry and 1,600 cavalry. A further 2,000 Gallic cavalry and many Gallic infantry were also serving with the Romans. Scipio led out all of his 3,600 cavalry and, anticipating that they would be outnumbered, supplemented them with a large but unknown number of the 4,500 or so available velites.

Battle

Neither the precise date nor the precise location of the battle are known: it took place in late November 218 BC on the flat country on the west bank of the Ticinus, not far from modernPavia

Pavia (, , , ; la, Ticinum; Medieval Latin: ) is a town and comune of south-western Lombardy in northern Italy, south of Milan on the lower Ticino river near its confluence with the Po. It has a population of c. 73,086. The city was the ...

. The ancient historians Livy and Polybius both give accounts of the battle, which agree on the main events, but differ in some of the details. Formal battles were usually preceded by the two armies camping two to twelve kilometres (1–7 mi) apart for days or weeks; sometimes forming up in battle order each day. In such circumstances either commander could prevent a battle from occurring, and unless both commanders were willing to at least some degree to give battle the stand off would end with one army simply marching off without engaging. Many battles were decided when one side was partially or wholly enveloped and their infantry were attacked in the flank or rear. It was unusual, prior to Ticinus, for one side's more mobile cavalry to be similarly enveloped. During periods when armies were encamped in close proximity it was common for their light forces to skirmish with each other, attempting to gather information on each other's forces and achieve minor, morale-raising victories. These were typically fluid affairs and viewed as preliminaries to any subsequent battle.

Hannibal placed his cavalry in a line with the close-order formations in the centre. The more manoeuvrable

Hannibal placed his cavalry in a line with the close-order formations in the centre. The more manoeuvrable Numidian cavalry

Numidian cavalry was a type of light cavalry developed by the Numidians. After they were used by Hannibal during the Second Punic War, they were described by the Roman historian Livy as "by far the best horsemen in Africa."

History

Numidian cava ...

were positioned on the flanks and possibly held back slightly. Scipio, who had gained a low opinion of the Carthaginian cavalry from the clash near the Rhone, expected an extended exchange of javelins and hoped that his velites, being smaller targets and better able to shelter behind their shields than the Carthaginian horses, would come off best. He arranged the 2,000 Gallic cavalry to the front of his formationmany or all of them would have carried a javelinman riding behind each of the cavalrymen, as was their tradition. Scipio positioned the velites in close support of the Gauls. On sighting the enemy, the velites sallied forward from behind their cavalry to advance within javelin-hurling range. On seeing this, the whole of the Carthaginian close-order cavalry promptly charged them. The Roman light infantry, realising they would be cut down if the Carthaginians came into contact with them, turned and fled, making no attempt to throw their missiles. The Roman cavalry, who were all close order attempted to counter charge the Carthaginians. They were obstructed by the large number of their infantry attempting to pass through their ranks to the rear, and in the case of the Gallic cavalry, possibly by still having a javelinman riding into battle behind each of the cavalrymen. The modern historian Philip Sabin comments that the Roman cavalry and infantry got into a "dreadful tangle".

The cavalry did not move into contact at speed, but at a fast walk or slow trot; any faster would have "ended in a growing pile of injured men and horses", according to the modern historian Sam Koon. Once in contact with the enemy, many of the cavalrymen dismounted to fight; this was a frequent occurrence in Punic War cavalry combat. There is debate among modern scholars as to the reasons for this common tactic. Certainly the second men on some, and possibly all, of the 2,000 Gallic cavalry's horses dismounted and joined the fight. Some of the Roman javelinmen also reinforced their cavalry comrades, but the extent to which this occurred is unclear. The ensuing melee is recorded as continuing for some time, with no clear advantage being gained by either side.

Then the Carthaginian light cavalry swept round both ends of the line of battle, attacking the still disorganised velites and the small Roman cavalry reserve, where Scipio had positioned himself. These Carthaginians also threatened, and threw javelins at, the rear of the already engaged Roman troops, throwing them into confusion and panic. The velites, still aware of their vulnerability to cavalry, immediately fled. The Roman reserve cavalry attempted to protect the rear of the fighting line, but were surrounded and Scipio was badly wounded. The main force of Roman cavalry, attacked from both sides, was routed and suffered heavy losses. In the confusion Scipio's 16-year-old son, also named Publicus Cornelius Scipio, cut his way through to his wounded father at the head of a small group; he escorted him away from the fight, saving him from being either captured or killed. The losses suffered by each side are not known, but the Roman casualties are believed to have been severe.

The surviving Roman forces regathered at their camp, still held by their heavy infantry. Aware the Carthaginians could now use their superiority in cavalry to isolate his camp, Scipio withdrew during the night back over the Ticinus. He left a force behind to dismantle the pontoon bridge so the Carthaginians would be unable to follow. Hannibal pursued the next day and captured 600 men from this rearguard, but not before the bridge had been rendered impassable.

Aftermath

Rivergaro

Rivergaro ( Piacentino: ) is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Province of Piacenza in the Italian region Emilia-Romagna, located about northwest of Bologna and about southwest of Piacenza. As of 31 December 2011, it had a population of 6,843 a ...

. Even so, they had to abandon much of their baggage and heavier gear, and many stragglers were killed or captured. Scipio waited for reinforcements while Hannibal camped at a distance on the plain below and gathered and trained the Gauls now flocking to his standard.

Shocked by Hannibal's arrival and Scipio's setback, the Roman Senate ordered the army commanded by Tiberius Longus in Sicily to march north to assist Scipio. When Longus arrived in December, Hannibal enticed him into attacking and heavily defeated him at the battle of the Trebia

The Battle of the Trebia (or Trebbia) was the first major battle of the Second Punic War, fought between the Carthaginian forces of Hannibal and a Roman army under Sempronius Longus on 22 or 23 December 218 BC. It took place on the flood ...

; only approximately 10,000 of the Roman army of 40,000 were able to fight their way off the battlefield. As a result the flow of Gallic support became a flood and the Carthaginian army grew to 60,000 men. Hannibal settled into winter quarters to rest and train his men, while the Romans drew up plans to prevent Hannibal from breaking into Roman Italy. In May 217BC the Carthaginians crossed the Apennines

The Apennines or Apennine Mountains (; grc-gre, links=no, Ἀπέννινα ὄρη or Ἀπέννινον ὄρος; la, Appenninus or – a singular with plural meaning;''Apenninus'' (Greek or ) has the form of an adjective, which wou ...

and provoked a Roman army into a hasty pursuit without proper reconnaissance. Hannibal set an ambush and in the battle of Lake Trasimene

The Battle of Lake Trasimene was fought when a Carthaginian force under Hannibal ambushed a Roman army commanded by Gaius Flaminius on 21 June 217 BC, during the Second Punic War. It took place on the north shore of Lake Trasimene, to t ...

completely defeated the Roman force, killing 15,000 Romans and taking 15,000 prisoner

A prisoner (also known as an inmate or detainee) is a person who is deprived of liberty against their will. This can be by confinement, captivity, or forcible restraint. The term applies particularly to serving a prison sentence in a prison. ...

. A cavalry force of 4,000 from another Roman army were also engaged and wiped out. Hannibal campaigned in Italy for the next 12 years.

In 204 BC Publius Cornelius Scipio, the same man who had fought as a youth at Ticinus, invaded the Carthaginian homeland in North Africa, defeated the Carthaginians in two major battles and won the allegiance of the Numidian kingdoms of North Africa. Hannibal and the remnants of his army were recalled from Italy to confront him. They met at the battle of Zama

The Battle of Zama was fought in 202 BC near Zama, now in Tunisia, and marked the end of the Second Punic War. A Roman army led by Publius Cornelius Scipio, with crucial support from Numidian leader Masinissa, defeated the Carthaginian ...

in October 202BC and Hannibal was decisively defeated. As a consequence Carthage agreed a peace treaty

A peace treaty is an agreement between two or more hostile parties, usually countries or governments, which formally ends a state of war between the parties. It is different from an armistice, which is an agreement to stop hostilities; a surre ...

which stripped it of most of its territory and power.

Notes, citations and sources

Notes

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{Authority controlTicinus

The river Ticino ( , ; lmo, Tesín; French and german: Tessin; la, Ticīnus) is the most important perennial left-bank tributary of the Po. It has given its name to the Swiss canton through which its upper portion flows.

It is one of the four ...

Ticinus

The river Ticino ( , ; lmo, Tesín; French and german: Tessin; la, Ticīnus) is the most important perennial left-bank tributary of the Po. It has given its name to the Swiss canton through which its upper portion flows.

It is one of the four ...

218 BC

Ticinus

The river Ticino ( , ; lmo, Tesín; French and german: Tessin; la, Ticīnus) is the most important perennial left-bank tributary of the Po. It has given its name to the Swiss canton through which its upper portion flows.

It is one of the four ...