Battle of Mycale on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Battle of Mycale was one of the two major battles (the other being the Battle of Plataea) that ended the second Persian invasion of Greece during the

After the battle, there were concerns over how the Greeks of Asia Minor could be defended against the potential Persian vengeance. The Peloponnesians suggested a population exchange, where the Greeks who did not want to live under Persian rule would be relocated in northern Greece, on the properties of the medizers who would be expelled. However, since all of northern Greece had surrendered to the Persians, this plan was abandoned. Also, Xanthippus had claimed the Greeks of Asia Minor were Athenian settlers, and thus Athens would not let their settlements be abandoned. Historian Joshua Nudell argues this debate over the Ionians presaged the future war between Athens and Sparta, namely the

After the battle, there were concerns over how the Greeks of Asia Minor could be defended against the potential Persian vengeance. The Peloponnesians suggested a population exchange, where the Greeks who did not want to live under Persian rule would be relocated in northern Greece, on the properties of the medizers who would be expelled. However, since all of northern Greece had surrendered to the Persians, this plan was abandoned. Also, Xanthippus had claimed the Greeks of Asia Minor were Athenian settlers, and thus Athens would not let their settlements be abandoned. Historian Joshua Nudell argues this debate over the Ionians presaged the future war between Athens and Sparta, namely the

Flower and Marincola observe that many of the predictions made by Hegesistratos did not materialise: the Ionians did not revolt when the Greeks arrived in Ionia, and did so only after the people of Samos and Miletus rebelled first. They note how odd it was for the Persians to not have attacked the Greeks while the latter were landing. They quote the 5th centuryBC Athenian general

Flower and Marincola observe that many of the predictions made by Hegesistratos did not materialise: the Ionians did not revolt when the Greeks arrived in Ionia, and did so only after the people of Samos and Miletus rebelled first. They note how odd it was for the Persians to not have attacked the Greeks while the latter were landing. They quote the 5th centuryBC Athenian general  Historian wonders why the Spartans, forever hesitant of embarking on naval campaigns to remote places, immediately agreed to sail to Samos after the visit of the envoys. Badi observes how strange it is for the Spartans to fight for the liberation of the Ionians at a time when the Greek mainland was still under Persian occupation. According to

Historian wonders why the Spartans, forever hesitant of embarking on naval campaigns to remote places, immediately agreed to sail to Samos after the visit of the envoys. Badi observes how strange it is for the Spartans to fight for the liberation of the Ionians at a time when the Greek mainland was still under Persian occupation. According to

Livius Picture Archive: Mycale (Dilek Dagi)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Battle Of Mycale Mycale Mycale 479 BC Mycale Battles involving ancient Athens Battles involving Sparta Battles involving ancient Greece

Greco-Persian Wars

The Greco-Persian Wars (also often called the Persian Wars) were a series of conflicts between the Achaemenid Empire and Polis, Greek city-states that started in 499 BC and lasted until 449 BC. The collision between the fractious political world ...

. It took place on 27 or 28 August, 479BC on the slopes of Mount Mycale, which is located on the coast of Ionia

Ionia ( ) was an ancient region encompassing the central part of the western coast of Anatolia. It consisted of the northernmost territories of the Ionian League of Greek settlements. Never a unified state, it was named after the Ionians who ...

opposite the island of Samos

Samos (, also ; , ) is a Greek island in the eastern Aegean Sea, south of Chios, north of Patmos and the Dodecanese archipelago, and off the coast of western Turkey, from which it is separated by the Mycale Strait. It is also a separate reg ...

. The battle was fought between an alliance of Greek city-states, including Sparta

Sparta was a prominent city-state in Laconia in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (), while the name Sparta referred to its main settlement in the Evrotas Valley, valley of Evrotas (river), Evrotas rive ...

, Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

and Corinth

Corinth ( ; , ) is a municipality in Corinthia in Greece. The successor to the ancient Corinth, ancient city of Corinth, it is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Sin ...

; and the Persian Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire, also known as the Persian Empire or First Persian Empire (; , , ), was an Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty in 550 BC. Based in modern-day Iran, it was the larg ...

of Xerxes I.

The previous year, the Persian invasion force, led by Xerxes himself, had scored victories at the battles of Thermopylae

Thermopylae (; ; Ancient: , Katharevousa: ; ; "hot gates") is a narrow pass and modern town in Lamia (city), Lamia, Phthiotis, Greece. It derives its name from its Mineral spring, hot sulphur springs."Thermopylae" in: S. Hornblower & A. Spaw ...

and Artemisium, and conquered Thessaly

Thessaly ( ; ; ancient Aeolic Greek#Thessalian, Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic regions of Greece, geographic and modern administrative regions of Greece, administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient Thessaly, a ...

, Boeotia

Boeotia ( ), sometimes Latinisation of names, Latinized as Boiotia or Beotia (; modern Greek, modern: ; ancient Greek, ancient: ), is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the modern regions of Greece, region of Central Greece (adm ...

and Attica

Attica (, ''Attikḗ'' (Ancient Greek) or , or ), or the Attic Peninsula, is a historical region that encompasses the entire Athens metropolitan area, which consists of the city of Athens, the capital city, capital of Greece and the core cit ...

; however, at the ensuing Battle of Salamis, the Greek navy had won an unlikely victory, and therefore prevented the conquest of the Peloponnese

The Peloponnese ( ), Peloponnesus ( ; , ) or Morea (; ) is a peninsula and geographic region in Southern Greece, and the southernmost region of the Balkans. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmus of Corinth land bridg ...

. Xerxes then retreated, leaving his general Mardonius with a substantial army to finish off the Greeks the following year.

In the summer of 479BC, the Greeks assembled an army, and marched to confront Mardonius at the Battle of Plataea. At the same time, the Greek fleet sailed to Samos

Samos (, also ; , ) is a Greek island in the eastern Aegean Sea, south of Chios, north of Patmos and the Dodecanese archipelago, and off the coast of western Turkey, from which it is separated by the Mycale Strait. It is also a separate reg ...

, where the demoralized remnants of the Persian navy were based. The Persians, seeking to avoid a battle, beached their fleet below the slopes of Mycale, and built a palisaded camp with the support of a Persian army unit. The Greek commander Leotychides decided to attack the Persians anyway, landing the fleet's complement of marines to do so.

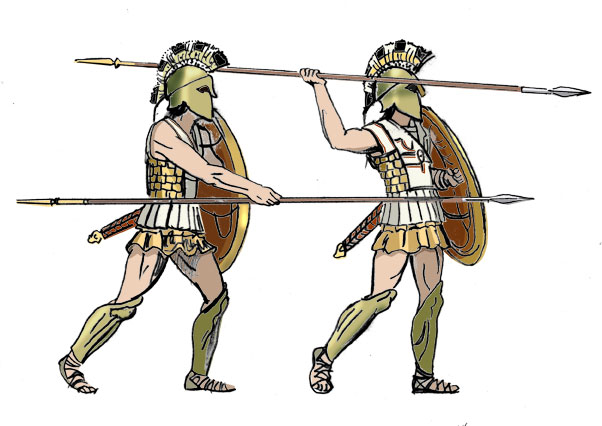

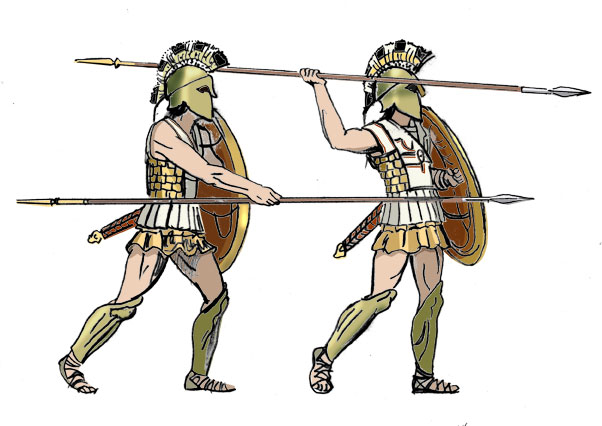

Although the Persian forces put up a sturdy resistance, the heavily armored Greek hoplites

Hoplites ( ) ( ) were citizen-soldiers of Ancient Greek city-states who were primarily armed with spears and shields. Hoplite soldiers used the phalanx formation to be effective in war with fewer soldiers. The formation discouraged the soldi ...

eventually routed the Persian troops, who fled to their camp. The Ionian Greek contingents in the Persian army defected, and the Persian camp was attacked, with a large number of Persians slaughtered. The Persian ships were then captured and burned. The complete destruction of the Persian navy, along with the destruction of Mardonius' army at Plataea, allegedly on the same day as the Battle of Mycale, decisively ended the invasion of Greece. After Plataea and Mycale, the Greeks would take the offensive against the Persians, marking a new phase of the Greco-Persian Wars.

Background

After Xerxes I was crowned the emperor of theAchaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire, also known as the Persian Empire or First Persian Empire (; , , ), was an Iranian peoples, Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty in 550 BC. Based in modern-day Iran, i ...

, he quickly resumed preparations for the invasion of Greece, including building two pontoon bridge

A pontoon bridge (or ponton bridge), also known as a floating bridge, is a bridge that uses float (nautical), floats or shallow-draft (hull), draft boats to support a continuous deck for pedestrian and vehicle travel. The buoyancy of the support ...

s across the Hellespont. A congress of city states met at Corinth

Corinth ( ; , ) is a municipality in Corinthia in Greece. The successor to the ancient Corinth, ancient city of Corinth, it is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Sin ...

in late autumn of 481BC, and a confederate alliance of Greek city-states was formed. In August 480BC, after hearing of Xerxes' approach, a small Greek army led by the Spartan king Leonidas I

Leonidas I (; , ''Leōnídas''; born ; died 11 August 480 BC) was king of the Ancient Greek city-state of Sparta. He was the son of king Anaxandridas II and the 17th king of the Agiad dynasty, a Spartan royal house which claimed descent fro ...

blocked the Pass of Thermopylae

Thermopylae (; ; Ancient: , Katharevousa: ; ; "hot gates") is a narrow pass and modern town in Lamia (city), Lamia, Phthiotis, Greece. It derives its name from its Mineral spring, hot sulphur springs."Thermopylae" in: S. Hornblower & A. Spaw ...

, while an Athenian-dominated navy sailed to the Straits of Artemisium. The vastly outnumbered Greek army held Thermopylae against the Persian army for six days in total, before being outflanked by the Persians. The Persians also achieved a costly naval triumph at the Battle of Artemisium, where they forced the Greek fleet to withdraw and thus captured the Euripus Strait.

After Thermopylae, the Persian army had burned and sacked the Boeotian cities which had not surrendered, namely Plataea and Thespiae, before taking possession of the now-evacuated city of Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

. The Greek army, meanwhile, prepared to defend the Isthmus of Corinth

The Isthmus of Corinth ( Greek: Ισθμός της Κορίνθου) is the narrow land bridge which connects the Peloponnese peninsula with the rest of the mainland of Greece, near the city of Corinth. The wide Isthmus was known in the a ...

. The ensuing naval Battle of Salamis ended in a decisive victory for the Greeks, marking a turning point in the conflict. Following the defeat of his navy at Salamis, Xerxes retreated to Asia with a minor portion of his army.

The Persian fleet had been stationed in Samos to defend Ionia and avert an Ionian revolt. The Persians were not expecting the Greeks to mount a naval attack on the other end of the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans and Anatolia, and covers an area of some . In the north, the Aegean is connected to the Marmara Sea, which in turn con ...

, because the Greeks had not followed through on their victory at Salamis by chasing the Persian fleet. However, the morale of the Persian fleet was breaking, and they were anxiously awaiting new reports on the status of the land army led by Mardonius. According to historian Charles Hignett, it was clear that only the triumph of the Persian land army in Greece could sustain Persian rule in Ionia.

Xerxes left Mardonius with most of his army, and the latter decided to camp for the winter in Thessaly. The 110 ships of the Greek fleet were anchored at Aegina

Aegina (; ; ) is one of the Saronic Islands of Greece in the Saronic Gulf, from Athens. Tradition derives the name from Aegina (mythology), Aegina, the mother of the mythological hero Aeacus, who was born on the island and became its king.

...

under the command of the Spartan king Leotychides in the spring of 479BC. Six people from Chios

Chios (; , traditionally known as Scio in English) is the fifth largest Greece, Greek list of islands of Greece, island, situated in the northern Aegean Sea, and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, tenth largest island in the Medi ...

who had made an unsuccessful attempt to overthrow Strattis, their ruling tyrant

A tyrant (), in the modern English usage of the word, is an absolute ruler who is unrestrained by law, or one who has usurped a legitimate ruler's sovereignty. Often portrayed as cruel, tyrants may defend their positions by resorting to ...

, escaped to Sparta. They requested the Spartan ephor

The ephors were a board of five magistrates in ancient Sparta. They had an extensive range of judicial, religious, legislative, and military powers, and could shape Sparta's home and foreign affairs.

The word "''ephors''" (Ancient Greek ''éph ...

s to free Ionia, and the latter sent them to Leotychides. They managed to persuade the Greek fleet to move to Delos. The Greeks hesitated to sail anywhere farther than Delos; because they were unfamiliar with the lands which lay there, thought they were full of armed peoples and believed the journey was too long. The Greek and Persian fleets stayed in their positions, apprehensive of moving closer to their opponent. Meanwhile, the Athenian navy under Xanthippus

Xanthippus (; , ; 520 – 475 BC) was a wealthy Ancient Athens, Athenian politician and general during the Greco-Persian Wars. He was the son of Ariphron and father of Pericles, both prominent Athenian statesmen. A marriage to Agariste, niece ...

had joined with the Greek fleet off Delos.

They were then approached by a delegation from Samos

Samos (, also ; , ) is a Greek island in the eastern Aegean Sea, south of Chios, north of Patmos and the Dodecanese archipelago, and off the coast of western Turkey, from which it is separated by the Mycale Strait. It is also a separate reg ...

under the leadership of Hegesistratos in the month of July, who said the Ionian cities were eager to revolt. They also pointed out the poor morale and reduced seaworthiness of the Persian fleet, the latter had occurred probably due to the long time it had spent at sea. Leotychides found Hegesistratos' name to be a good omen, since it meant "Army Leader". The delegation from Samos, as envoys of their nation, pledged their loyalty to the Hellenic alliance. Leotychides and the council of war decided to exploit this opportunity and sailed for Samos. The route he took probably began from the Cyclades

The CYCLADES computer network () was a French research network created in the early 1970s. It was one of the pioneering networks experimenting with the concept of packet switching and, unlike the ARPANET, was explicitly designed to facilitate i ...

, it then involved sailing for approximately in the open ocean, passing Icaria and Coressia to finally land near Mount Ampelus in Samos.

The Persians withdrew from Samos; Hignett argues that by doing so, they left to the Greeks an advantageous post which was the strongest on the Ionian coast. The Persians at Samos had control of the best harbor in all of the Aegean Sea and a great water supply. Historian John Barron argues their retreat was not absurd: the channel was just about wide at its thinnest point, therefore, the Greeks could not send their entire fleet after the Persians. But the Persians did not force a battle and did not move to the excellent harbor at Miletus

Miletus (Ancient Greek: Μίλητος, Mílētos) was an influential ancient Greek city on the western coast of Anatolia, near the mouth of the Maeander River in present day Turkey. Renowned in antiquity for its wealth, maritime power, and ex ...

, instead choosing to land at Mycale, where Barron says they could observe the Greeks but the Greeks could not see them. Barron notes the absolute breakdown of the will to fight of the Persians at this point.

Classicists Michael Flower and John Marincola argue that the Greeks may have decided to sail to Samos only because they were told about a potential Ionian revolt, and about the disrepair of the Persian fleet. Flower and Marincola note that the Greeks had previously been quite hesitant to sail beyond Delos because of the Persian fleet. Historian Marcello Lupi also notes that the Greek fleet had sailed at the insistence of the Samians and had been unwilling to chase the Persians after Salamis, hesitating to move out of Delos.

Flower and Marincola argue that the envoys from Samos were more reliable than the envoys from Chios, since the latter were "conspirators on the run" while the former were the representatives of their people. They note that Hegesistratos had claimed there was a chance the Persian fleet could be seized with one maneuver. They argue that Leotychides may have considered this a risk he could take. They also note that the Greek fleet had already sailed for Samos when their ambassadors reported the dismissal of the Phoenician ships from the Persian fleet.

Historian Peter Green argues that the Phoenician ships were dismissed either to defend the shores of Thrace

Thrace (, ; ; ; ) is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe roughly corresponding to the province of Thrace in the Roman Empire. Bounded by the Balkan Mountains to the north, the Aegean Sea to the south, and the Black Se ...

and the Dardanelles

The Dardanelles ( ; ; ), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli (after the Gallipoli peninsula) and in classical antiquity as the Hellespont ( ; ), is a narrow, natural strait and internationally significant waterway in northwestern Turkey th ...

; or because the Persian high command could not trust the Phoenicians after Salamis. Barron argues that the Phoenicians were dismissed due to their low morale. Historian Jack Balcer observes the error of the Persians in dismissing the Phoenicians, and claims the battle would have unfolded differently had the Phoenicians not been dismissed. Hignett argues that Leotychides was taking the risk of fighting a naval battle where the location and circumstances would be picked by the Persians, who could thus maximize their advantages. Barron argues that passing over the opportunity to destroy their opponent's fleet would be an absurd decision to make for both the Persians and the Greeks, especially since the land war was coming to a close, and because both sides would be expecting the mustering of their opponent's flotillas. Balcer notes how the original mission of the Greek fleet was not letting the Persian fleet reinforce Mardonius, and how the fleet took a bold decision to go on the offensive.

Opposing forces

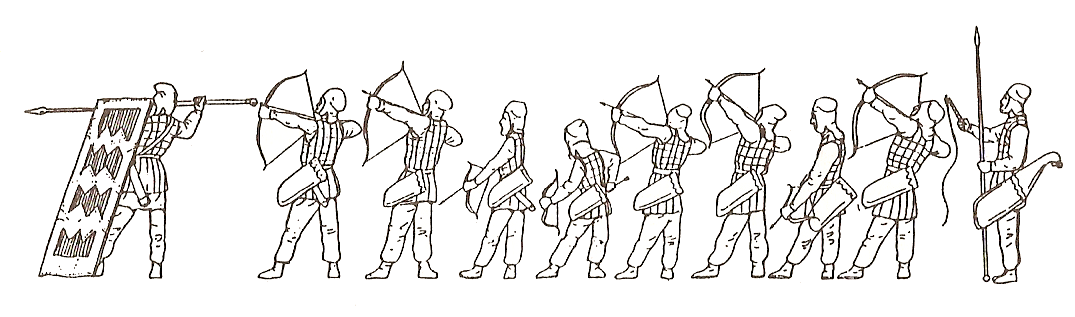

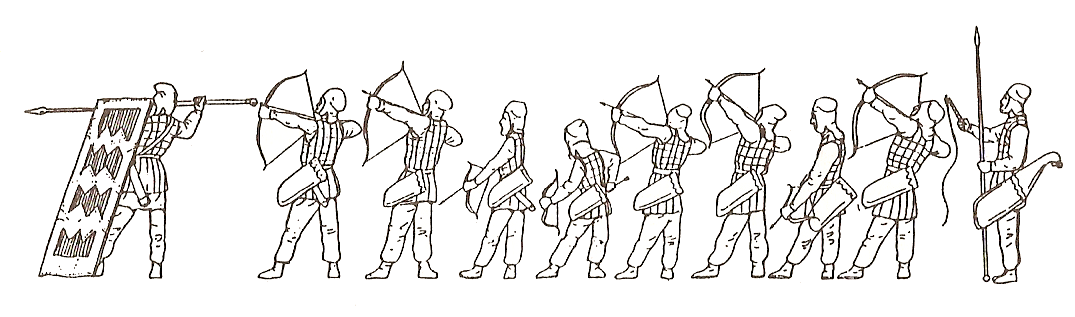

Persians

Ancient historianHerodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

gives the size of the Persian fleet which wintered at Cyme at 300 ships. The Phoenician ships were dismissed from the Persian fleet before the battle, which reduced its strength. Historian Charles Hignett found the fleet size of 300 ships to be too large, even if this number included the Phoenician ships. Green estimates that there were approximately just 100 ships in the Persian fleet after the Phoenicians left. Barron also arrives at an estimate of 100 ships after this dismissal.

Tigranes was the commander of the Persian land forces at Mycale. Artaÿntes was the joint commander of the Persian fleet, and he appointed his nephew, Ithamitres, as the third commander for the fleet. Herodotus states that there were 60,000 soldiers in the Persian army at Mycale. Hignett argues that Herodotus' own narrative of the battle contradicts these numbers, and claims Tigranes could not have had more than 10,000 soldiers in his unit. Shepherd also estimates that Tigranes had around 10,000 soldiers; with an additional 3,000 Persian infantry who had disembarked from the ships. Shepherd also notes that Tigranes notably did not have cavalry contingents among his troops. Green estimates that Tigranes had only 6,000 soldiers with him, who were joined by the 4,000 marines in the Persian fleet, for a total of 10,000 combatants. Historian Richard Evans estimates that there were around 4,000 total combatants available to the Persians.

Greeks

Historian Andrew Robert Burn estimates the Greek fleet had 110 ships. Burn notes that the figure of 250 ships is only stated by Ephorus. Flower and Marincola argue that the Athenians did not have the numbers to provide marines for 50 triremes and 8,000hoplites

Hoplites ( ) ( ) were citizen-soldiers of Ancient Greek city-states who were primarily armed with spears and shields. Hoplite soldiers used the phalanx formation to be effective in war with fewer soldiers. The formation discouraged the soldi ...

at Plataea both at the same time. They thus argue that the claim of 250 ships in the Greek fleet is not realistic. Herodotus did not give a precise order of battle

Order of battle of an armed force participating in a military operation or campaign shows the hierarchical organization, command structure, strength, disposition of personnel, and equipment of units and formations of the armed force. Various abbr ...

for Mycale in his account. Historian William Shepherd estimates Athens provided one-third of the ships; while Sparta and the Peloponnesian poleis may have contributed 10 and 20–30 ships respectively. Shepherd estimates Aegina and Corinth sent 10 ships each. Historian David Asheri posits that the Athenians contributed 50 ships to the Greek fleet at Mycale. An epigram from an ''agora

The agora (; , romanized: ', meaning "market" in Modern Greek) was a central public space in ancient Ancient Greece, Greek polis, city-states. The literal meaning of the word "agora" is "gathering place" or "assembly". The agora was the center ...

'' (public square) in Megara

Megara (; , ) is a historic town and a municipality in West Attica, Greece. It lies in the northern section of the Isthmus of Corinth opposite the island of Salamis Island, Salamis, which belonged to Megara in archaic times, before being taken ...

says Megarians fought and suffered casualties in the battle of Mycale, but they are not mentioned in any account of the battle.

The standard complement of a trireme

A trireme ( ; ; cf. ) was an ancient navies and vessels, ancient vessel and a type of galley that was used by the ancient maritime civilizations of the Mediterranean Sea, especially the Phoenicians, ancient Greece, ancient Greeks and ancient R ...

was 200 people, including 14 marines. Flower and Marincola estimate that the Greeks had 3,300 marines, with the 110 ships having 30 marines each. They note that the complement of marines on a trireme was probably not fixed, with Plutarch stating that there were 14 marines on each trireme at Salamis. Herodotus had said the Chian ships at the Battle of Lade had carried 40 marines each. Hignett also arrives at an estimate of 3,300 marines in the Greek force. He argues that there could not have been more than 6,000 marines, even if there were hoplites employed as rowers. Burn notes that the Greek contingent of marines was strong, and strongly considers the possibility that some of the Greek oarsmen served as light infantry

Light infantry refers to certain types of lightly equipped infantry throughout history. They have a more mobile or fluid function than other types of infantry, such as heavy infantry or line infantry. Historically, light infantry often fought ...

(agile, lightly-armed infantry) Historian George Cawkwell argues the Greeks had only 2,000 to 3,000 marines, because their ships had mostly naval personnel on board. Flower and Marincola also note that Leotychides and Xanthippus probably had equal powers, and posit that the military decisions were finalized by a majority vote.

Shepherd argues the Greek contingent at Mycale did not have more than 25,000 soldiers. Shepherd arrives at an estimate of 3,000 marines with 30 on each ship; and argues that the remaining 22,000 people on board served mostly as light infantry, with some of them being employed as hoplites. Green's estimate for the number of Greek combatants was 5,000 heavy infantry (rigid, heavily-armed infantry), and 2,000 to 3,000 sailors serving as light infantry. Evans estimates that there were 70 Athenian, 8 Spartan, 20 Corinthian, 3 Troe1zenian and 8 Sicyonian ships in the Greek fleet at Mycale. Supposing each ship had 10 hoplites on board, he comes up with the following order of battle: 700 hoplites from Athens, 200 from Corinth, 80 from Sicyon, 30 from Troezen and 80 from Sparta (probably helots

The helots (; , ''heílotes'') were a subjugated population that constituted a majority of the population of Laconia and Messenia – the territories ruled by Sparta. There has been controversy since antiquity as to their exact characteristic ...

); for a total of 1,100 hoplites. The triremes did not have weapons on board for the 170 oarsmen who staffed them, and so the oarsmen probably used whatever weapons and armor they could find, assuming they did fight.

Prelude

When the Persians heard the Greek fleet was approaching, they set sail from Samos towards Mycale in the Ionian mainland, possibly because they had decided they could not fight a naval battle. During the chaos of their retreat, the Samians freed 500 Athenian captives. Burn argues the Persian fleet had anchored at Mycale because their commanders thought it would be "useless to fight at sea". Cawkwell notes that the Persian fleet had moved from Samos to Mycale for protection according to Herodotus. Green argues the Persians retreated to Mycale because they could communicate easily with Sardis and retreat without trouble. The Persians arrived on the southern shore of Mycale, near a temple dedicated to the two Potnia (female goddesses),Demeter

In ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, Demeter (; Attic Greek, Attic: ''Dēmḗtēr'' ; Doric Greek, Doric: ''Dāmā́tēr'') is the Twelve Olympians, Olympian goddess of the harvest and agriculture, presiding over cro ...

and Kore (Persephone

In ancient Greek mythology and Ancient Greek religion, religion, Persephone ( ; , classical pronunciation: ), also called Kore ( ; ) or Cora, is the daughter of Zeus and Demeter. She became the queen of the Greek underworld, underworld afte ...

). Another temple dedicated to Eleusinian Demeter was nearby; three temples dedicated to these same goddesses were also present on or near the battlefield of Plataea.The Persians took away the armor and weapons of the Samians in their army, finding them unreliable. Furthermore, they sent the Milesians to their rear to guard the mountain passes of Mycale, suspecting the Milesians of wanting to defect. Hignett argues the Persian distrust of the Milesians was invented later, and notes that the Milesians were actually guarding the lines of communication and the mountain passes the Persians could use to retreat. To the south of these passes, on the beaches on the route from Samos, the Persians moored their fleet behind the cover of rocks, and built abatis (field fortifications) with the wood they had cut recently. They put up stakes (''skolopes'') on the ramparts, and as a result, the place where they had camped became known as Skolopoeis by Herodotus' time. With their preparations in place, the Persians decided to defend their position, primarily expecting a siege.

The camp was located near the Gaison river. German archaeologist Theodor Wiegand had suggested Domatia (modern day Doğanbey, Söke) as the site for the camp; while German classicist Johannes Kromayer had proposed a site near the modern village of Ak Bogaz. Shepherd proposes the village of Atburgazı as the site for the Persian camp and the battlefield. Historian Jan Zacharias van Rookhuijzen suggests Güllübahçe, Söke, the modern site of the ancient city of New Priene, as another potential location for the battlefield of Mycale. German philologist had suggested a location between Atburgazı and Yuvaca, Söke as the site for the battlefield.

The Greeks encamped at Kalamoi (the Reeds), adjacent to the Heraion of Samos and around from the city. Their opponent was inactive, and thus they were planning to not fight a battle, and instead attack the Persian communications center at the Hellespont. However, they decided to attack their opponent and his fleet, and moved towards Mycale, around from Samos by the naval route. Hignett argues this decision indicated the Greeks were sure they could fight a decisive battle. The Greeks prepared for a naval battle in case the Persians decided to fight at sea, but they had resolved to confront the Persian land army in case there was no naval battle. The Greek fleet moved towards the shore and called on the Ionians to revolt. The Greeks then sailed farther and their soldiers landed in a location beyond the line of sight of their opponents. Shepherd estimates this location was inside the bay and to the immediate west of the city of Priene. Herodotus reports that when the Greeks approached the Persian camp, rumor spread among them of a Greek victory at Plataea earlier on in the day.The battle

The Greeks probably formed into two wings. On the left were the Athenians, Corinthians,Sicyon

Sicyon (; ; ''gen''.: Σικυῶνος) or Sikyōn was an ancient Greek city state situated in the northern Peloponnesus between Corinth and Achaea on the territory of the present-day regional unit of Corinthia. The ruins lie just west of th ...

ians and Troezenians; around half of the army, who took up positions starting from the shore and ending at the foothills of Mount Mycale. On the right were the Spartans with the other contingents, deployed on the hills in uneven terrain. The battle of Mycale commenced in the afternoon on the same day as the battle of Plataea, which historian Paul A. Rahe estimates took place on 27 or 28 August. Hignett also proposes a date in late August. The battle began when the Greek left began fighting with the Persians while their right wing was still crossing the hills. The Persians moved out from their camp and put up their shield wall. Burn argues that Tigranes wanted to vanquish half of the Greeks facing him while the other half had still not arrived on the battlefield. Green argues that sending only the flank led by the Athenians at first was actually a tactical move by Leotychides, who wanted the Persians to think they had a large advantage in numbers. Green claims the Persians fell for the ruse and rushed to attack the Greeks.

The Greek right, under heavy arrow fire, decided to fight in close quarters. Until the Persian shield wall was unbroken, the Persians defended their position. At this point, the contingents on the Greek right encouraged each other by saying the victory should belong to them and not to the Spartans. They increased their efforts, and managed to break through the wall by shoving. Tigranes and Mardontes died in the ensuing combat. The Persians fought back initially, but then broke their lines and escaped to their camp. The soldiers of the right wing followed them into the camp, and most of the Persian soldiers fled from the camp, except the ethnic Persian troops, who grouped together and fought the Greek soldiers who had entered the camp. Finally, the left wing arrived, outflanking the camp and falling on the rear of the remaining Persian forces, thereby completing the rout.

Herodotus says the disarmed Samians had joined the Greeks on seeing the outcome of the battle hung in the balance. This inspired the other Ionian contingents to turn on the Persians as well. Meanwhile, the Milesians who were guarding the passes of Mycale also turned on the Persians. At first, they misdirected the fleeing Persian contingents, who then ended up back among the Greeks troops; then, perhaps seeing the outcome of the battle was certain, they began killing the fleeing Persians. The Greeks then burned the Persian fleet after a heavily contested fight with the Persian marines, after taking out the loot from the ships and placing it on the beach. The Persian fortifications were also burnt.

Herodotus does not mention specific figures for casualties, merely saying that losses were heavy on both sides. The Sicyonians in particular suffered, also losing their general Perilaus. On the Persian side, the admiral Mardontes and the general Tigranes were both killed, though Artaÿntes and Ithamitres escaped. Green estimates the Persian casualties at 4,000. Hermolycus, an Athenian from the ''deme

In Ancient Greece, a deme or (, plural: ''demoi'', δήμοι) was a suburb or a subdivision of Classical Athens, Athens and other city-states. Demes as simple subdivisions of land in the countryside existed in the 6th century BC and earlier, bu ...

'' (suburb) of Scambonidae, was considered to have been the most gallant Greek soldier during the battle. The Athenians were considered the most courageous contingent on the battlefield, followed by the soldiers of Corinth, Troezen and Sicyon.

Aftermath

With the twin victories of Plataea and Mycale, the second Persian invasion of Greece was over. Moreover, the threat of a future invasion was abated; although the Greeks were worried Xerxes would try again, over time it was apparent that the Persian desire to conquer Greece was much diminished. The Greeks returned to Samos and discussed their next moves. The Greek fleet then moved to the Hellespont, sailed first to Lecton and then to Abydos to break down the pontoon bridges, but found them destroyed. The Peloponnesians sailed home, but the Athenians remained to attack the Chersonesos, still held by the Persians. The Persians in the region and their Greek vassals made for Sestos, the strongest town in the region, and the Athenians laid siege to them there. After a protracted siege, Sestos fell to the Athenians, marking the beginning of a new phase in theGreco-Persian Wars

The Greco-Persian Wars (also often called the Persian Wars) were a series of conflicts between the Achaemenid Empire and Polis, Greek city-states that started in 499 BC and lasted until 449 BC. The collision between the fractious political world ...

, the Greek counterattack. The city-states of Chios, Lesbos

Lesbos or Lesvos ( ) is a Greek island located in the northeastern Aegean Sea. It has an area of , with approximately of coastline, making it the third largest island in Greece and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, eighth largest ...

and Samos joined the Hellenic alliance, and their Persian garrisons were eliminated. Strattis of Chios was overthrown, and the family of the poet Ion of Chios is highly likely to have played a role. The Greeks could not subdue Ionia entirely and could only free the Aegean islands. However, Thrace

Thrace (, ; ; ; ) is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe roughly corresponding to the province of Thrace in the Roman Empire. Bounded by the Balkan Mountains to the north, the Aegean Sea to the south, and the Black Se ...

and Macedonia were able to break their alliance with the Persians because of the Greek victories at Plataea and Mycale. Also, the coastal areas of Lydia

Lydia (; ) was an Iron Age Monarchy, kingdom situated in western Anatolia, in modern-day Turkey. Later, it became an important province of the Achaemenid Empire and then the Roman Empire. Its capital was Sardis.

At some point before 800 BC, ...

(Sparda), and the Asiatic Greek polities stretching from the Troad to Caria

Caria (; from Greek language, Greek: Καρία, ''Karia''; ) was a region of western Anatolia extending along the coast from mid-Ionia (Mycale) south to Lycia and east to Phrygia. The Carians were described by Herodotus as being Anatolian main ...

split off from the Persians.Peloponnesian War

The Second Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC), often called simply the Peloponnesian War (), was an Ancient Greece, ancient Greek war fought between Classical Athens, Athens and Sparta and their respective allies for the hegemony of the Ancien ...

.

Rahe argues the real reason Athens was trying to make its settlers stay in Ionia was because they could defend Athenian food imports from Crimea

Crimea ( ) is a peninsula in Eastern Europe, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, almost entirely surrounded by the Black Sea and the smaller Sea of Azov. The Isthmus of Perekop connects the peninsula to Kherson Oblast in mainland Ukrain ...

. Burn found this idea of a population exchange to have parallels with the population exchange between Greece and Turkey implemented 24 centuries later. Burn also found a repeat of the Battle of Mycale in the Battle of the Eurymedon, fought by the Athenian general Cimon

Cimon or Kimon (; – 450BC) was an Athenian '' strategos'' (general and admiral) and politician.

He was the son of Miltiades, also an Athenian ''strategos''. Cimon rose to prominence for his bravery fighting in the naval Battle of Salamis ...

against the Persians in 466BC. After Mycale, the state of Teos would create multiple imprecations to be used on people who exploited the role of the '' aesymnetes'' (elected official) to become tyrants.

After the battle, the Persian marshal Masistes would accuse the surviving naval commanders of being cowards; Burn, however, argues they survived because they were just trying to get their non-Persian soldiers back to the battlefield. In the spring of 488BC, the tyrant of Cilicia, Xenagoras of Halicarnassus, recently appointed by emperor Xerxes, would raid the temple of Apollo

Apollo is one of the Twelve Olympians, Olympian deities in Ancient Greek religion, ancient Greek and Ancient Roman religion, Roman religion and Greek mythology, Greek and Roman mythology. Apollo has been recognized as a god of archery, mu ...

at Didyma

Didyma (; ) was an Ancient Greece, ancient Greek sanctuary on the coast of Ionia in the domain of the famous city of Miletus. Apollo was the main deity of the sanctuary of Didyma, also called ''Didymaion''. But it was home to both of the Ancient ...

and seize the bronze idol of the deity, in revenge for the Milesians switching sides at Mycale. Historian Iain Spence argues the victory at Mycale reiterated the maritime supremacy of the Greeks. He further argues that the resultant defection of the Aegean states facilitated Greek marine campaigns, thus leading to the establishment of the naval empire of the Delian League

The Delian League was a confederacy of Polis, Greek city-states, numbering between 150 and 330, founded in 478 BC under the leadership (hegemony) of Classical Athens, Athens, whose purpose was to continue fighting the Achaemenid Empire, Persian ...

and Athens. The Persian Empire's borders were fixed and their numerous invasions became rare. After the Persian defeat at Mycale, the satrap

A satrap () was a governor of the provinces of the ancient Median kingdom, Median and Achaemenid Empire, Persian (Achaemenid) Empires and in several of their successors, such as in the Sasanian Empire and the Hellenistic period, Hellenistic empi ...

y of Bactria

Bactria (; Bactrian language, Bactrian: , ), or Bactriana, was an ancient Iranian peoples, Iranian civilization in Central Asia based in the area south of the Oxus River (modern Amu Darya) and north of the mountains of the Hindu Kush, an area ...

began an armed revolt, which may have bolstered the resolve of Artabanus to assassinate Xerxes.

Historian David C. Yates notes the exclusion of the states of Samos and Chios from the list of states on the Serpent Column, even though both had a strong claim. He argues they were excluded because they had opposed the continued Spartan command of the Hellenic League. Yates also notes the presence of Spartan and Corinthian troops in all five battles of the Persian Wars, the only two states to have this distinction.

Spoils

Xanthippus captured the cables of the Persian bridges in Cardia after he took the town. Barron notes that these cables might have adorned the stylobates (column bases) of the newly built Temple of Athena Nike on theAcropolis of Athens

The Acropolis of Athens (; ) is an ancient citadel located on a rocky outcrop above the city of Athens, Greece, and contains the remains of several Ancient Greek architecture, ancient buildings of great architectural and historical significance, ...

. Fragments from the cables, mixed with stern

The stern is the back or aft-most part of a ship or boat, technically defined as the area built up over the sternpost, extending upwards from the counter rail to the taffrail. The stern lies opposite the bow, the foremost part of a ship. O ...

decorations taken from the Persian ships at Mycale, were displayed at Delphi

Delphi (; ), in legend previously called Pytho (Πυθώ), was an ancient sacred precinct and the seat of Pythia, the major oracle who was consulted about important decisions throughout the ancient Classical antiquity, classical world. The A ...

near the terrace walls of the Temple of Apollo. An inscription near these displays said the Athenians had captured these items from the enemy, without mentioning the other Greek allies. The 4th centuryBC Athenian orator Demosthenes

Demosthenes (; ; ; 384 – 12 October 322 BC) was a Greek statesman and orator in ancient Athens. His orations constitute a significant expression of contemporary Athenian intellectual prowess and provide insight into the politics and cu ...

had thought the tall statue of Athena Promachos (forefighter), completed and displayed on the Acropolis of Athens, was constructed with money from the loot taken at Plataea and Mycale. According to the Roman engineer Vitruvius

Vitruvius ( ; ; –70 BC – after ) was a Roman architect and engineer during the 1st century BC, known for his multi-volume work titled . As the only treatise on architecture to survive from antiquity, it has been regarded since the Renaissan ...

, the "masts and spars" of the Persian ships were incorporated into the roof of the Odeon of Pericles theatre at Athens.

Analysis

Flower and Marincola observe that many of the predictions made by Hegesistratos did not materialise: the Ionians did not revolt when the Greeks arrived in Ionia, and did so only after the people of Samos and Miletus rebelled first. They note how odd it was for the Persians to not have attacked the Greeks while the latter were landing. They quote the 5th centuryBC Athenian general

Flower and Marincola observe that many of the predictions made by Hegesistratos did not materialise: the Ionians did not revolt when the Greeks arrived in Ionia, and did so only after the people of Samos and Miletus rebelled first. They note how odd it was for the Persians to not have attacked the Greeks while the latter were landing. They quote the 5th centuryBC Athenian general Demosthenes

Demosthenes (; ; ; 384 – 12 October 322 BC) was a Greek statesman and orator in ancient Athens. His orations constitute a significant expression of contemporary Athenian intellectual prowess and provide insight into the politics and cu ...

, who had said a naval landing could not be executed successfully when an opponent who held the land resolved to fight.

Balcer argues the Persians should have deployed their fleet in the open sea and should not have built their fortifications. He further argues that the Persian defeats were the results of military and logistical mistakes committed by the Persians.

Historian George Cawkwell argues the numbers given by Herodotus are highly overstated. He further argues that the battle was a "very minor affair", but its outcomes were major because it led to an Ionian revolt. Cawkwell observes that the withdrawal of the majority of the Persian fleet just before the battle of Mycale was a grave mistake. Cawkwell claims Tigranes didn't have many soldiers with him. He argues the Persian fleet did not have the required number of soldiers to fight the Greek fleet, and sailed to Mycale only because of the presence of Tigranes' troops.

Burn argues the destruction of the Persian fleet at Mycale allowed the Greek fleets absolute freedom of movement. Historian Muhammad Dandamayev agrees with this conclusion. The Persian and Median marines, as well as the Persian units in Tigranes' army, were almost completely massacred. In their absence, the Persian vassals had refused to fight and fled. Historian Paul A. Rahe argues the Persians had had ten months since the battle of Salamis to repair their fleet. He further argues that the Persian hesitation to fight a naval battle, despite their numerical superiority, indicated that either the morale of their commanders was shaken, or they believed the soldiers in their army drawn from their Greek vassals would mutiny. Rahe argues that emperor Xerxes could have been the one who ordered his soldiers not to fight a naval battle, and instead beach their ships.

Historian J. B. Bury argues the indecisiveness of the Spartans led to the Greeks of Asia Minor joining the Delian League led by Athens. He argues the Spartans left the Greeks of Asia Minor unprotected against the Persians, even though the latter had proposed the creation of a Hellenic League after Mycale. The hesitation of the Spartans to defend the Ionians and the resolve of Athens to do so led to the competition and strife between the two superpowers during the 5th centuryBC. Historian wonders why the Spartans, forever hesitant of embarking on naval campaigns to remote places, immediately agreed to sail to Samos after the visit of the envoys. Badi observes how strange it is for the Spartans to fight for the liberation of the Ionians at a time when the Greek mainland was still under Persian occupation. According to

Historian wonders why the Spartans, forever hesitant of embarking on naval campaigns to remote places, immediately agreed to sail to Samos after the visit of the envoys. Badi observes how strange it is for the Spartans to fight for the liberation of the Ionians at a time when the Greek mainland was still under Persian occupation. According to Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus or Diodorus of Sicily (; 1st century BC) was an ancient Greece, ancient Greek historian from Sicily. He is known for writing the monumental Universal history (genre), universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty ...

, it was actually the Samians who had persuaded the Greeks to attack the Persian fleet. Badi also questions the narrative of the Greek fleet mobilizing and sailing from Delos to Samos in one day, and says even a modern navy cannot move so quickly. Historian says the Greek triumph at Mycale was a strategic "feat of the first order", however, it was probably not appreciated by the contemporary Greeks. He argues most members of the Greek fleet were volunteers, enticed by the spoils they could take. Wallinga argues the Persian commanders had made a reasonable decision by stowing their ships, because they could then be used in the future, instead of risking them in a one-sided battle where the Persians had the numerical advantage but the morale of their crews was broken.

Formations

Historian Richard Evans estimates the length of the beach in Mycale at during low tide. Evans argues the small beach would have restricted the deployment of a phalanx with a uniform depth of ranks. He posits that the Greeks would have used a wedge formation, with 700 Athenian hoplites deploying 50 ranks deep while the others deployed ten ranks deep. Assuming each hoplite took up of space, he estimates the Athenians deployed 14 rows and formed a line wide. Similarly, he expects the Corinthians to have deployed 20 rows, the Sicyonians and Spartans 8 rows each, and the Troezenians 3 rows. Evans then estimates the Greek line was long.Historiography

The main source for the Greco-Persian Wars is the ancient Greek historianHerodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

. He gives an account of the battle of Mycale in Book Nine of his ''Histories''. Historian had noted multiple similarities in Herodotus' accounts, which he argued were arbitrary insertions by Herodotus. Fehling noted that the Spartan nauarch (fleet commander) at Mycale had used the same plan used by Themistocles at the Battle of Artemisium, and the Ionian tyrant

A tyrant (), in the modern English usage of the word, is an absolute ruler who is unrestrained by law, or one who has usurped a legitimate ruler's sovereignty. Often portrayed as cruel, tyrants may defend their positions by resorting to ...

s at the Battle of Lade: calling upon the Ionians to switch sides. Fehling also notes how the shield wall fighting is always concluded by the Athenians in Herodotus' accounts, especially at Plataea and Mycale. Shepherd also notes the multiple similarities between Plataea and Mycale. However, he finds some major differences in the latter battle: the absence of cavalry; the Persian command's lack of trust in their Greek vassal soldiers resulting in a lower force strength; and the reversal of Plataea at Mycale where the Greeks were the attackers and the Persians were the defenders.

Classicists Michael Flower and John Marincola also found these similarities between the battles of Plataea and Mycale to be suspicious, especially since the victories there gave both Sparta and Athens, respectively, similar triumphs on the same day. Flower and Marincola note that the victory at Mycale was not celebrated by any Athenian orators, who were otherwise proud of their other achievements in the Persian Wars. They argue this omission occurred because the leader at Mycale was a Spartan in what could be considered a naval battle, a domain where the Athenians believed they were better. Flower and Marincola note how the '' aristeia'' (heroic moment) of the Athenians takes place on Ionian lands, and wonder whether this part of Herodotus' account is structured to justify the Athenian claim to the command of the Delian League. Flower and Marincola find the account of Mycale given by Diodorus Siculus to be unreliable and mixed with arbitrary claims by Ephorus of Cyme, his primary source. Timaeus may also have been a source for Diodorus. Flower and Marincola note that in Herodotus' account, he mentions the burial of the fallen Greek soldiers after the battle of Thermopylae, but does not mention any burials after the battles of Mycale, Salamis or Marathon.Historian David Asheri found other similarities between Plataea and Mycale: the issue of defending the mountain passes, the deployment of the Athenians on the plains and the Spartans on the hills, the concluding heroic resistance of the few remaining Persian fighters and the delayed arrival of other Greek contingents on the battlefield. Asheri also noted a direct comparison between the battles of Mycale and Artemisium. Asheri argues the battle of Mycale was narrated by Herodotus from a religious perspective, and not from a strategic and military perspective. Asheri postulates that Herodotus used sources from Athens and Samos because of the biases towards these ''poleis'' in his account. Nudell argues that the Ionian betrayal of the Persians is overstated, perhaps invented to salvage the reputation of Greek states which had fought for the Persians.

Historian Henry Immerwahr posits that the battles of Plataea and Mycale are connected in a manner similar to how the battles of Thermopylae and Artemisium are connected. Badi also made note of these narrative structures, where a land battle and a naval battle are fought on the same day. Immerwahr notes how the Athenians at Mycale are shown to have been better combatants on land than the Spartans, which he believes to be a result of drawing from a pro-Athenian source. Hellanicus of Lesbos

Hellanicus (or Hellanikos) of Lesbos (Greek language, Greek: , ''Hellánikos ho Lésbios''), also called Hellanicus of Mytilene (Greek language, Greek: , ''Hellánikos ho Mutilēnaîos''; 490 – 405 BC), was an ancient Greece, Greek logographe ...

might have been the pro-Athenian and anti-Spartan source used by Herodotus.

Immerwahr notes how the Athenian victory at Mycale offsets their defeat at Artemisium. Badi argues Herodotus clubbed his account of Mycale with Plataea because he wanted to "superimpose" an Athenian victory on a Spartan one. Badi argues the Athenian victory at Mycale was also given more prestige in Herodotus' account, because the victor had not been forced to retreat from their position, unlike at Plataea. Immerwahr observes how the divine was the key element in the accounts of Plataea and Mycale given by Herodotus, whose narrative of the latter battle did not focus at all on military matters. Historian Richard Evans thinks Herodotus based his account of Mycale on battle descriptions in Homer

Homer (; , ; possibly born ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Despite doubts about his autho ...

's Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; , ; ) is one of two major Ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Odyssey'', the poem is divided into 24 books and ...

. Evans also notes the multiple parallels between Mycale and Thermopylae. Evans also notes Mycale to be the first battle in recorded history fought on a beach.

Historian Jan Zacharias van Rookhuijzen notes how Plutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

is the only ancient writer who described the victory at Mycale as something the Athenians took pride in. Plutarch, in his account, had also noted the Corinthian gallantry at Mycale. van Rookhuijzen notes how most ancient writers did not give the battle much thought, with Ephorus of Cyme being the only one who considered it to have some importance. Modern historians like Hignett and Cawkwell have claimed Herodotus also did not have much interest in the battle. Herodotus probably concluded his account with the battle of Mycale and the second Ionian revolt because he wanted to come full circle on the commencement of his account with the first Ionian Revolt.

Burn found Herodotus' account to be biased towards the Athenians. He also finds the battle of Mycale to have parallels with Plataea, as both battles saw only one flank engaged in combat, and both witnessed fighting at the Persian shield walls and camps. Hignett argues the similarities between the two battles are not suspicious and can naturally be expected. Burn says Mycale was a "relatively small battle", and notes how Thucydides

Thucydides ( ; ; BC) was an Classical Athens, Athenian historian and general. His ''History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts Peloponnesian War, the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been d ...

did not consider it as important as Salamis or Artemisium. In the works of the tragic poet Phrynichus, the naval victories at Salamis and Mycale were the results of policies crafted by the Athenian commander Themistocles. Historian says Phyrnichus formed his opinions on the Persian Wars by emphasizing the two triumphs of the Greek navy at Salamis and Mycale. Stoessl notes that Aeschylus

Aeschylus (, ; ; /524 – /455 BC) was an ancient Greece, ancient Greek Greek tragedy, tragedian often described as the father of tragedy. Academic knowledge of the genre begins with his work, and understanding of earlier Greek tragedy is large ...

believed the Europeans and Asians should not cross the seas and intervene in each other's countries. Stoessl says this is the reason for Aeschylus not even mentioning the battle of Mycale, precisely because it was fought in Asia Minor.

Ships

Historian Iain McDougall doubts the narrative of the Persian ships being burnt after the Greek victory at Mycale. He argues the ships would have been valuable items of loot, and notes how there is no historical precedent for such actions. German classicist Karl Julius Beloch had thought the Persians burned their ships themselves; Italian historian Giulio Giannelli had thought the Athenians and especially Themistocles had burnt the ships, while Hignett thought only the Ionian ships in the Persian fleet were spared. McDougall argues the ships in the Persian fleet which were burnt primarily belonged to the Ionian Greeks, who he argues had contributed most of the ships present at Mycale. McDougall further argues the ships in the Persian fleet were greatly damaged and could not be salvaged, and were therefore burnt. Asheri also says the Greeks did not have the required numbers to staff the ships they could have captured from the Persian fleet; therefore, they preferred burning the ships instead of letting the Persians take them back. McDougall and Wallinga argue the Persians had used wood from their ships to construct their field fortifications. Evans says this is not plausible, noting the statement by Herodotus, who says stones and tree trunks were used. Evans says the Persians were already quite exhausted, and stripping wood from their ships would have taken them too much time. Evans estimates there were 200 Persian ships, and says constructing a fortification to store all of them would be tough on the beach's terrain. Assuming the ships were stored in columns of 70 and rows of three, and each ship took up of length, of width and an additional on both the top and bottom; the total length would be and the total width would be . Evans says this is too large a fort to be accommodated on beaches in the Mediterranean, where the length from the land to the water is not more than usually.Notes

References

Bibliography

Theses and research papers

* * * * * *Books

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Book chapters

* * * *External links

Livius Picture Archive: Mycale (Dilek Dagi)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Battle Of Mycale Mycale Mycale 479 BC Mycale Battles involving ancient Athens Battles involving Sparta Battles involving ancient Greece