Bangladesh Liberation War on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Bangladesh Liberation War (, ), also known as the Bangladesh War of Independence, was an

Before the

Before the

In 1947, the Bengali Muslims had identified themselves with Pakistan's Islamic project, but by the 1970s, the people of East Pakistan had given priority to their Bengali ethnicity over their religious identity, desiring a society in accordance with Western principles such as

In 1947, the Bengali Muslims had identified themselves with Pakistan's Islamic project, but by the 1970s, the people of East Pakistan had given priority to their Bengali ethnicity over their religious identity, desiring a society in accordance with Western principles such as

Although East Pakistan accounted for a slight majority of the country's population, political power remained in the hands of West Pakistanis. Since a straightforward system of representation based on population would have concentrated political power in East Pakistan, the West Pakistani establishment came up with the "

Although East Pakistan accounted for a slight majority of the country's population, political power remained in the hands of West Pakistanis. Since a straightforward system of representation based on population would have concentrated political power in East Pakistan, the West Pakistani establishment came up with the "

A planned military pacification carried out by the

A planned military pacification carried out by the

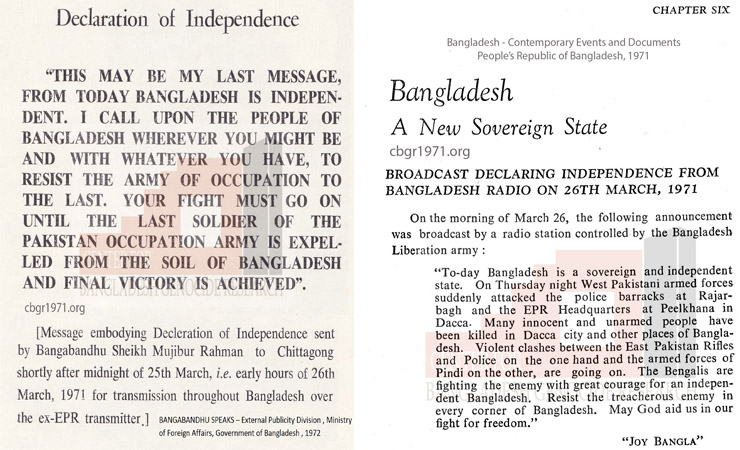

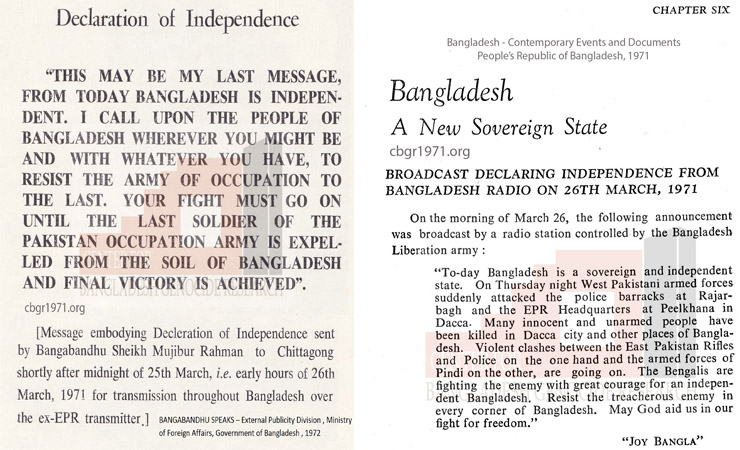

The violence unleashed by the Pakistani forces on 25 March 1971 proved the last straw to the efforts to negotiate a settlement. Following these incidents, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman signed an official declaration that read:

Sheikh Mujib also called upon the people to resist the occupation forces through a radio message. Rahman was arrested on the night of 25–26 March 1971 at about 1:30 am (as per Radio Pakistan's news on 29 March 1971).

A telegram containing the text of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's declaration reached some students in

The violence unleashed by the Pakistani forces on 25 March 1971 proved the last straw to the efforts to negotiate a settlement. Following these incidents, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman signed an official declaration that read:

Sheikh Mujib also called upon the people to resist the occupation forces through a radio message. Rahman was arrested on the night of 25–26 March 1971 at about 1:30 am (as per Radio Pakistan's news on 29 March 1971).

A telegram containing the text of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's declaration reached some students in

Bangladesh forces command was set up on 11 July, with Col.

Bangladesh forces command was set up on 11 July, with Col.

Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi concluded that instead of taking in millions of refugees, India would be economically better off going to war against Pakistan. As early as 28 April 1971, the Indian Cabinet had asked General Manekshaw (

Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi concluded that instead of taking in millions of refugees, India would be economically better off going to war against Pakistan. As early as 28 April 1971, the Indian Cabinet had asked General Manekshaw (

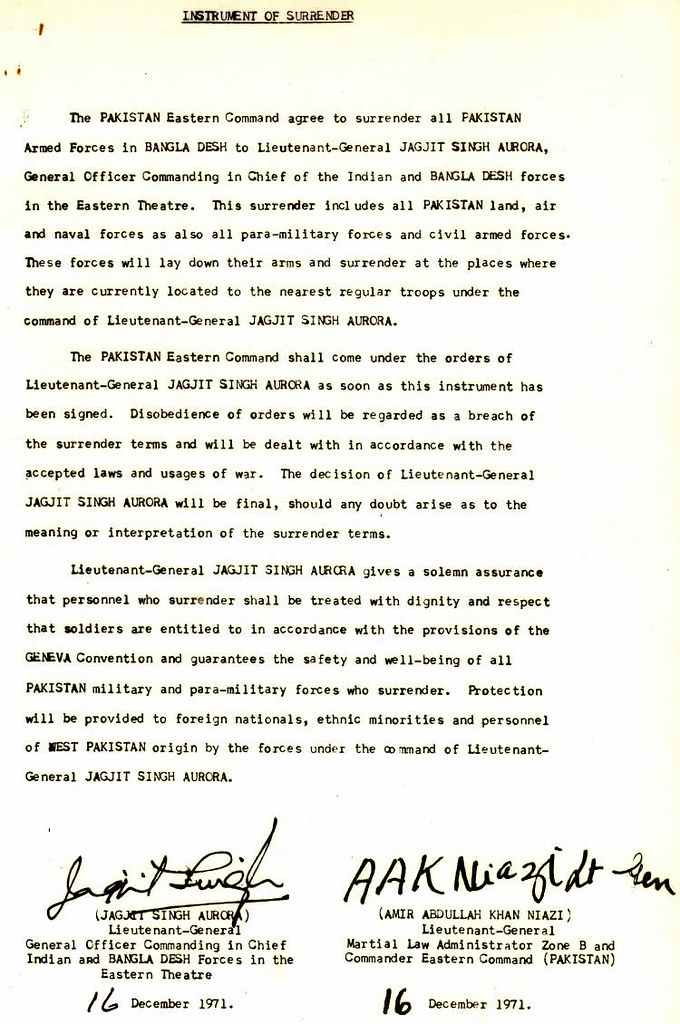

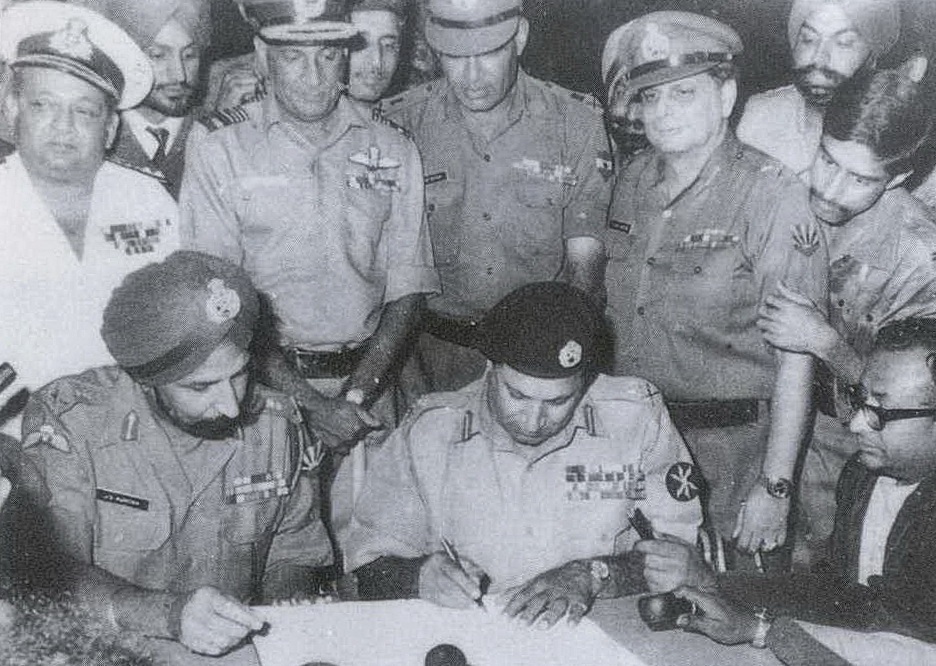

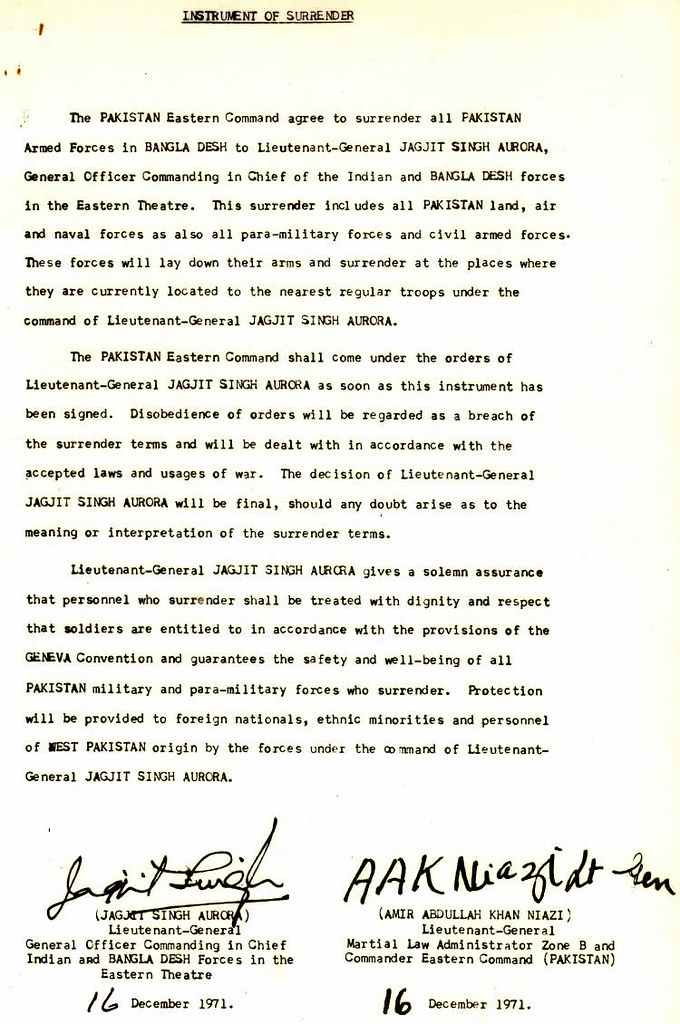

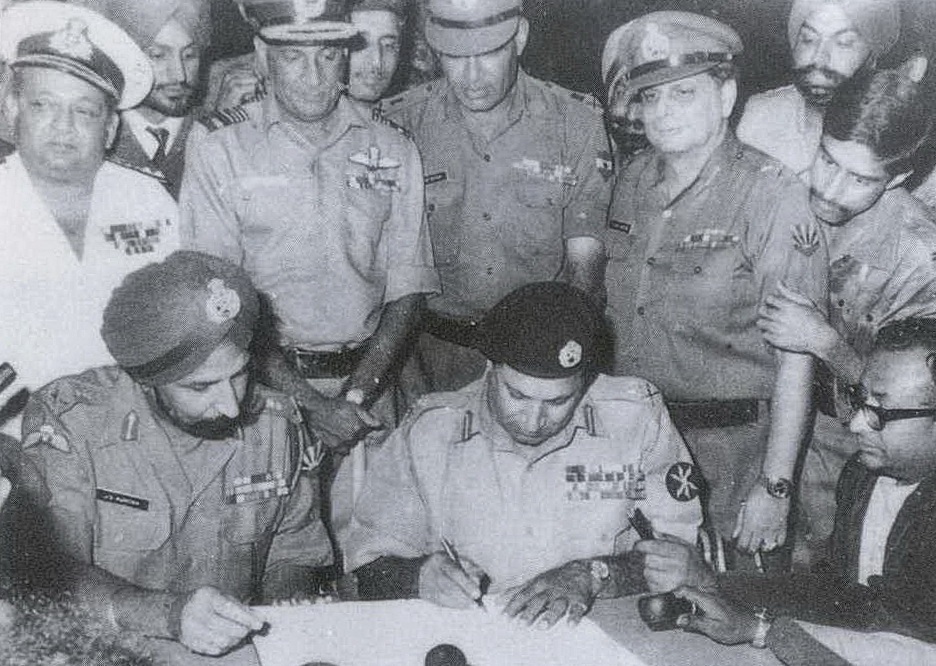

On 16 December 1971, Lt. Gen Amir Abdullah Khan Niazi,

On 16 December 1971, Lt. Gen Amir Abdullah Khan Niazi,

Death Tolls for the Major Wars and Atrocities of the Twentieth Century

'' and raped between 200,000 and 400,000 Many mass graves have been discovered in Bangladesh. The first night of war on Bengalis, which is documented in telegrams from the American Consulate in Dacca to the U.S. State Department, saw indiscriminate killings of students of Dacca University and other civilians. Numerous women were tortured, raped, and killed during the war; the exact numbers are not known and are debated. The widespread rape of Bangladeshi women led to birth of thousands of

Many mass graves have been discovered in Bangladesh. The first night of war on Bengalis, which is documented in telegrams from the American Consulate in Dacca to the U.S. State Department, saw indiscriminate killings of students of Dacca University and other civilians. Numerous women were tortured, raped, and killed during the war; the exact numbers are not known and are debated. The widespread rape of Bangladeshi women led to birth of thousands of

Army Terror Campaign Continues in Dacca; Evidence Military Faces Some Difficulties Elsewhere

, 31 March 1971, Confidential, 3 pp but also by Bengali nationalists against non-Bengali minorities, especially

Selective genocide

'', Cable (PDF) and "genocide" (see The Blood Telegram) for information on events they had knowledge of at the time. ''

The Men Behind Yahya in the Indo-Pak War of 1971

To demonstrate to China the ''bona fides'' of the United States as an ally, and in direct violation of the US Congress-imposed sanctions on Pakistan, Nixon sent military supplies to Pakistan and routed them through Jordan and Iran, while also encouraging China to increase its arms supplies to Pakistan. The Nixon administration also ignored reports it received of the genocidal activities of the Pakistani Army in East Pakistan, most notably the Blood telegram. Nixon denied getting involved in the situation, saying that it was an internal matter of Pakistan, but when Pakistan's defeat seemed certain, he sent the aircraft carrier USS ''Enterprise'' to the

Nixon denied getting involved in the situation, saying that it was an internal matter of Pakistan, but when Pakistan's defeat seemed certain, he sent the aircraft carrier USS ''Enterprise'' to the

The Tilt: the U.S. and the South Asian Crisis of 1971

* Quereshi, Major General Hakeem Arshad, ''The 1971 Indo-Pak War, A Soldiers Narrative'', Oxford University Press, 2002. * Raghavan, Srinath, ''1971: A Global History of the Creation of Bangladesh,'' Harvard Univ. Press, 2013. * Sisson, Richard & Rose, Leo, ''War and secession: Pakistan, India, and the creation of Bangladesh'', University of California Press (Berkeley), 1990. * Stephen, Pierre, and Payne, Robert, ''Massacre'', Macmillan, New York, (1973). * Totten, Samuel et al., eds., ''Century of Genocide: Eyewitness Accounts and Critical Views'', Garland Reference Library, 1997 * US Department of State Office of the Historian

''Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969–1976, Volume XI, South Asia Crisis, 1971''

* Zaheer, Hasan: ''The separation of East Pakistan: The rise and realisation of Bengali Muslim nationalism'', Oxford University Press, 1994. *

Handwritten Constitution of Bangladesh

1971 Bangladesh Genocide Archive

Freedom In the Air

The Daily Star

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20030501230820/http://www.bangladeshmariners.com/HmdrRprt/71mass.html 1971 Massacre in Bangladesh and the Fallacy in the Hamoodur Rahman Commission Report, Dr. M.A. Hasan

Women of Pakistan Apologize for War Crimes, 1996

Sheikh Mujib wanted a confederation: US papers, by Anwar Iqbal, Dawn, 7 July 2005

Bangladesh Liberation War Picture Gallery

Graphic images, viewer discretion advised

1971 War: How Russia sank Nixon's gunboat diplomacy

PM reiterated her vow to declare March 25 as Genocide Day

Call for international recognition and observance of genocide day

Genocide Day: As it was in March 1971

The case for UN recognition of Bangladesh genocide

{{Authority control 1971 in Bangladesh 1971 in India 1971 in Pakistan Conflicts in 1971 Civil wars involving the states and peoples of Asia Civil wars of the 20th century Military history of Bangladesh Separatist rebellion-based civil wars Wars involving Bangladesh Wars involving India Wars involving Pakistan Wars of independence Post-independence history of Pakistan Yahya Khan Bangladesh–Pakistan relations Bangladesh–India relations India–Pakistan relations Bengali nationalism Cold War conflicts Ethnicity-based civil wars History of East Pakistan Independence of Bangladesh Violence against indigenous peoples in Asia Territorial evolution of Bangladesh

armed conflict

War is an armed conflict between the armed forces of states, or between governmental forces and armed groups that are organized under a certain command structure and have the capacity to sustain military operations, or between such organi ...

sparked by the rise of the Bengali nationalist and self-determination

Self-determination refers to a people's right to form its own political entity, and internal self-determination is the right to representative government with full suffrage.

Self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international la ...

movement in East Pakistan

East Pakistan was the eastern province of Pakistan between 1955 and 1971, restructured and renamed from the province of East Bengal and covering the territory of the modern country of Bangladesh. Its land borders were with India and Burma, wit ...

, which resulted in the independence of Bangladesh

Bangladesh, officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, eighth-most populous country in the world and among the List of countries and dependencies by ...

. The war began when the Pakistani military junta

A military junta () is a system of government led by a committee of military leaders. The term ''Junta (governing body), junta'' means "meeting" or "committee" and originated in the Junta (Peninsular War), national and local junta organized by t ...

based in West Pakistan

West Pakistan was the western province of Pakistan between One Unit, 1955 and Legal Framework Order, 1970, 1970, covering the territory of present-day Pakistan. Its land borders were with Afghanistan, India and Iran, with a maritime border wit ...

—under the orders of Yahya Khan

Agha Muhammad Yahya Khan (4 February 191710 August 1980) was a Pakistani army officer who served as the third president of Pakistan from 1969 to 1971. He also served as the fifth Commander-in-Chief, Pakistan, commander-in-chief of the Pakistan ...

—launched Operation Searchlight

Operation Searchlight was a military operation carried out by the Pakistan Army in an effort to curb the Bengali nationalist movement in former East Pakistan in March 1971. Pakistan retrospectively justified the operation on the basis of ant ...

against East Pakistanis on the night of 25 March 1971, initiating the Bangladesh genocide

The Bangladesh genocide was the ethnic cleansing of Bengalis residing in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) during the Bangladesh Liberation War, perpetrated by the Pakistan Army and the Razakar (Pakistan), Razakars. It began on 25 March 1971, as ...

.

In response to the violence, members of the Mukti Bahini

The Mukti Bahini, initially called the Mukti Fauj, also known as the Bangladesh Forces, was a big tent armed guerrilla resistance movement consisting of the Bangladeshi military personnel, paramilitary personnel and civilians during the Ba ...

—a guerrilla

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, Partisan (military), partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, which may include Children in the military, recruite ...

resistance movement

A resistance movement is an organized group of people that tries to resist or try to overthrow a government or an occupying power, causing disruption and unrest in civil order and stability. Such a movement may seek to achieve its goals through ei ...

formed by Bengali military, paramilitary and civilians—launched a mass guerrilla war against the Pakistani military

The Pakistan Armed Forces (; ) are the Military, military forces of Pakistan. It is the List of countries by number of military and paramilitary personnel, world's sixth-largest military measured by Active duty, active military personnel and c ...

, liberating numerous towns and cities in the war's initial months. At first, the Pakistan Army regained momentum during the monsoon

A monsoon () is traditionally a seasonal reversing wind accompanied by corresponding changes in precipitation but is now used to describe seasonal changes in Atmosphere of Earth, atmospheric circulation and precipitation associated with annu ...

, but Bengali guerrillas

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, Partisan (military), partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, which may include Children in the military, recruite ...

counterattacked by carrying out widespread sabotage, including through Operation Jackpot against the Pakistan Navy

The Pakistan Navy (PN) (; ''romanized'': Pākistān Bahrí'a; ) is the naval warfare branch of the Pakistan Armed Forces. The Chief of the Naval Staff, a four-star admiral, commands the navy and is a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Com ...

, while the nascent Bangladesh Air Force

The Bangladesh Air Force (BAF) () is the aerial warfare branch of the Bangladesh Armed Forces. The air force is primarily responsible for air defence of Bangladesh's sovereign territory as well as providing air support to the Bangladesh Army a ...

flew sortie

A sortie (from the French word meaning ''exit'' or from Latin root ''surgere'' meaning to "rise up") is a deployment or dispatch of one military unit, be it an aircraft, ship, or troops, from a strongpoint. The term originated in siege warf ...

s against Pakistani military bases. India joined the war on 3 December 1971, after Pakistan launched preemptive air strikes on northern India. The subsequent Indo-Pakistani War involved fighting on two fronts; with air supremacy

Air supremacy (as well as air superiority) is the degree to which a side in a conflict holds control of air power over opposing forces. There are levels of control of the air in aerial warfare. Control of the air is the aerial equivalent of ...

achieved in the eastern theater and the rapid advance of the Allied Forces of Mukti Bahini and the Indian military, Pakistan surrendered in Dhaka on 16 December 1971, in what remains to date the largest surrender of armed personnel since the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

Rural and urban areas across East Pakistan saw extensive military operations and air strikes to suppress the tide of civil disobedience

Civil disobedience is the active and professed refusal of a citizenship, citizen to obey certain laws, demands, orders, or commands of a government (or any other authority). By some definitions, civil disobedience has to be nonviolent to be cal ...

that formed after the 1970 election stalemate. The Pakistan Army

The Pakistan Army (, ), commonly known as the Pak Army (), is the Land warfare, land service branch and the largest component of the Pakistan Armed Forces. The president of Pakistan is the Commander-in-chief, supreme commander of the army. The ...

, backed by Islamists, created radical religious militias—the Razakars, Al-Badr and Al-Shams—to assist it during raids on the local populace. Members of the Pakistani military and supporting militias engaged in mass murder, deportation and genocidal rape

Genocidal rape, a form of wartime sexual violence, is the action of a group which has carried out acts of mass rape and gang rapes, against its enemy during wartime as part of a genocidal campaign. During the Armenian genocide, the Greek ...

, pursuing a systematic campaign of annihilation against nationalist Bengali civilians, students, intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the i ...

, religious minorities and armed personnel. The capital, Dhaka

Dhaka ( or ; , ), List of renamed places in Bangladesh, formerly known as Dacca, is the capital city, capital and list of cities and towns in Bangladesh, largest city of Bangladesh. It is one of the list of largest cities, largest and list o ...

, was the scene of numerous massacres, including the Dhaka University massacre. Sectarian violence

Sectarian violence or sectarian strife is a form of communal violence which is inspired by sectarianism, that is, discrimination, hatred or prejudice between different sects of a particular mode of an ideology or different sects of a religion wi ...

also broke out between Bengalis and Urdu-speaking Biharis. An estimated 10 million Bengali refugees

A refugee, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), is a person "forced to flee their own country and seek safety in another country. They are unable to return to their own country because of feared persecution as ...

fled to neighboring India, while 30 million were internally displaced.

The war changed the geopolitical landscape of South Asia, with the emergence of Bangladesh as the world's seventh-most populous country. Due to complex regional alliances, the war was a major episode in Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

tensions involving the United States, the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

and China. The majority of member states in the United Nations recognized Bangladesh as a sovereign nation in 1972.

Background

Before the

Before the Partition of British India

The partition of India in 1947 was the division of British India into two independent dominion states, the Union of India and Dominion of Pakistan. The Union of India is today the Republic of India, and the Dominion of Pakistan is the Islam ...

, the Lahore Resolution

The Lahore Resolution, later called the Pakistan Resolution in Pakistan, was a formal political statement adopted by the All-India Muslim League on the occasion of its three-day general session in Lahore, Punjab, from 22 to 24 March 1940, call ...

initially envisaged separate Muslim

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

-majority states in British India's eastern and northwestern zones. A proposal for an independent United Bengal

United Bengal was a proposal to transform Bengal Presidency, Bengal Province into an undivided, sovereign state at the time of the Partition of India in 1947. It sought to prevent the Partition of Bengal (1947), division of Bengal on religious ...

was mooted by Prime Minister Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy

Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy (8 September 18925 December 1963) was an East Pakistani barrister, politician and statesman who served as the Prime Minister of Pakistan from 1956 to 1957 and before that as the Prime Minister of Bengal from 1946 to ...

in 1946 but opposed by the colonial authorities. The East Pakistan Renaissance Society advocated the creation of a sovereign state

A sovereign state is a State (polity), state that has the highest authority over a territory. It is commonly understood that Sovereignty#Sovereignty and independence, a sovereign state is independent. When referring to a specific polity, the ter ...

in eastern British India.

Political negotiations led, in August 1947, to the official birth of two states, Pakistan

Pakistan, officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of over 241.5 million, having the Islam by country# ...

and India, giving presumably permanent homes for Muslims and Hindus, respectively, after the British departed. The Dominion of Pakistan

The Dominion of Pakistan, officially Pakistan, was an independent federal dominion in the British Commonwealth of Nations, which existed from 14 August 1947 to Pakistan Day, 23 March 1956. It was created by the passing of the Indian Independence ...

comprised two geographically and culturally separate areas to the east and the west, with India in between.

The western zone was popularly (and, for a period, also officially) termed West Pakistan and the eastern zone (modern-day Bangladesh) was initially termed East Bengal

East Bengal (; ''Purbô Bangla/Purbôbongo'') was the eastern province of the Dominion of Pakistan, which covered the territory of modern-day Bangladesh. It consisted of the eastern portion of the Bengal region, and existed from 1947 until 195 ...

and later East Pakistan. Although the two zones' population was close to equal, political power was concentrated in West Pakistan, and it was widely perceived that East Pakistan was being exploited economically, leading to many grievances. Administration of two discontinuous territories was also seen as a challenge.

On 25 March 1971, after an election won by an East Pakistani political party (the Awami League

The Awami League, officially known as Bangladesh Awami League, is a major List of political parties in Bangladesh, political party in Bangladesh. The oldest existing political party in the country, the party played the leading role in achievin ...

) was ignored by the ruling (West Pakistani) establishment, rising political discontent and cultural nationalism

Cultural nationalism is a term used by scholars of nationalism to describe efforts among intellectuals to promote the formation of national communities through emphasis on a common culture. It is contrasted with "political" nationalism, which r ...

in East Pakistan was met by brutal and suppressive force from the ruling elite of the West Pakistan establishment, in what came to be termed Operation Searchlight

Operation Searchlight was a military operation carried out by the Pakistan Army in an effort to curb the Bengali nationalist movement in former East Pakistan in March 1971. Pakistan retrospectively justified the operation on the basis of ant ...

. The Pakistan Army's violent crackdown led to Awami League leader Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (17 March 1920 – 15 August 1975), also known by the honorific Bangabandhu, was a Bangladeshi politician, revolutionary, statesman and activist who was the founding president of Bangladesh. As the leader of Bangl ...

declaring East Pakistan's independence as the state of Bangladesh on 26 March 1971. Most Bengalis supported this move, although some Islamists

Islamism is a range of Religion, religious and Politics, political ideological movements that believe that Islam should influence political systems. Its proponents believe Islam is innately political, and that Islam as a political system is su ...

and Biharis opposed it and sided with the Pakistan Army instead.

Pakistani President Agha Muhammad Yahya Khan ordered the Pakistani military to restore the Pakistani government's authority, beginning the civil war. The war led a substantial number of refugees (estimated at the time to be about 10 million) to flood India's eastern provinces.''Crisis in South Asia – A report'' by Senator Edward Kennedy to the Subcommittee investigating the Problem of Refugees and Their Settlement, Submitted to U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee, 1 November 1971, U.S. Govt. Press.pp6-7 Facing a mounting humanitarian and economic crisis, India actively aided and organized the Bangladeshi resistance army, the Mukti Bahini

The Mukti Bahini, initially called the Mukti Fauj, also known as the Bangladesh Forces, was a big tent armed guerrilla resistance movement consisting of the Bangladeshi military personnel, paramilitary personnel and civilians during the Ba ...

.

Language controversy

In 1948,Governor-General

Governor-general (plural governors-general), or governor general (plural governors general), is the title of an official, most prominently associated with the British Empire. In the context of the governors-general and former British colonies, ...

Muhammad Ali Jinnah

Muhammad Ali Jinnah (born Mahomedali Jinnahbhai; 25 December 187611 September 1948) was a barrister, politician, and the founder of Pakistan. Jinnah served as the leader of the All-India Muslim League from 1913 until the inception of Pa ...

declared that "Urdu

Urdu (; , , ) is an Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan language spoken chiefly in South Asia. It is the Languages of Pakistan, national language and ''lingua franca'' of Pakistan. In India, it is an Eighth Schedule to the Constitution of Indi ...

, and only Urdu" would be Pakistan's federal language. But Urdu was historically prevalent only in the north, central, and western subcontinent

A continent is any of several large geographical regions. Continents are generally identified by convention rather than any strict criteria. A continent could be a single large landmass, a part of a very large landmass, as in the case of A ...

; in East Bengal, the native language was Bengali, one of the two most easterly branches of the Indo-European languages

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the northern Indian subcontinent, most of Europe, and the Iranian plateau with additional native branches found in regions such as Sri Lanka, the Maldives, parts of Central Asia (e. ...

. Bengali speakers constituted over 56% of Pakistan's population.

The government stand was widely viewed as an attempt to suppress the culture of the eastern wing. The people of East Bengal demanded that their language be given federal status alongside Urdu and English. The Language Movement began in 1948, as civil society protested the removal of Bengali script

The Bengali script or Bangla alphabet (, Romanization of Bengali, romanized: ''Bāṅlā bôrṇômālā'') is the standard writing system used to write the Bengali language, and has historically been used to write Sanskrit within Bengal. ...

from currency and stamps, which were in place since the British Raj

The British Raj ( ; from Hindustani language, Hindustani , 'reign', 'rule' or 'government') was the colonial rule of the British The Crown, Crown on the Indian subcontinent,

*

* lasting from 1858 to 1947.

*

* It is also called Crown rule ...

.

The movement reached its climax in 1952, when on 21 February, the police fired on protesting students and civilians, causing several deaths. The day is revered in Bangladesh as the Language Movement Day

The Language Movement Day (), officially called Language Martyrs' Day (), is a national holiday of Bangladesh taking place on 21 February each year and commemorating the Bengali language movement and its martyrs. On this day, people visit Shahee ...

. In memory of the deaths, UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO ) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) with the aim of promoting world peace and International secur ...

declared 21 February International Mother Language Day

International Mother Language Day is a worldwide annual observance held on 21 February to promote awareness of linguistic and cultural diversity and to promote multilingualism. First announced by UNESCO on 17 November 1999, it was formally reco ...

in November 1999.

Disparities

Although, East Pakistan had the larger population, West Pakistan dominated the divided country politically and received more money from the common budget. East Pakistan was already economically disadvantaged at the time of Pakistan's creation yet this economic disparity only increased under Pakistani rule. Factors included not only the deliberate state discrimination in developmental policies but also the fact that the presence of the country's capital and more immigrant businessmen in the Western Wing directed greater government allocations there. Due to low numbers of native businessmen in East Pakistan, substantial labor unrest and a tense political environment, there were also much lower foreign investments in the eastern wing. The Pakistani state's economic outlook was geared towards urban industry, which was not compatible with East Pakistan's mainly agrarian economy. Also, Bengalis were underrepresented in the Pakistani military. Officers of Bengali origin in the different wings of the armed forces made up just 5% of the overall force by 1965; of these, only a few were in command positions, with the majority in technical or administrative posts. West Pakistanis believed that Bengalis were not "martially inclined", unlikePashtuns

Pashtuns (, , ; ;), also known as Pakhtuns, or Pathans, are an Iranian peoples, Iranic ethnic group primarily residing in southern and eastern Afghanistan and northwestern Pakistan. They were historically also referred to as Afghan (ethnon ...

and Punjabis

The Punjabis (Punjabi language, Punjabi: ; ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ; romanised as Pañjābī) are an Indo-Aryan peoples, Indo-Aryan ethnolinguistic group associated with the Punjab region, comprising areas of northwestern India and eastern Paki ...

; Bengalis dismissed the " martial races" notion as ridiculous and humiliating.

Moreover, despite huge defense spending, East Pakistan received none of the benefits, such as contracts, purchasing and military support jobs. The Indo-Pakistani War of 1965 over Kashmir

Kashmir ( or ) is the Northwestern Indian subcontinent, northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term ''Kashmir'' denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir P ...

also highlighted the sense of military insecurity among Bengalis, as only an under-strength infantry

Infantry, or infantryman are a type of soldier who specialize in ground combat, typically fighting dismounted. Historically the term was used to describe foot soldiers, i.e. those who march and fight on foot. In modern usage, the term broadl ...

division and 15 combat aircraft

A military aircraft is any fixed-wing or rotary-wing aircraft that is operated by a legal or insurrectionary military of any type. Some military aircraft engage directly in aerial warfare, while others take on support roles:

* Combat aircraft, ...

without tank support were in East Pakistan to repulse any Indian retaliations during the conflict.

Ideological and cultural differences

In 1947, the Bengali Muslims had identified themselves with Pakistan's Islamic project, but by the 1970s, the people of East Pakistan had given priority to their Bengali ethnicity over their religious identity, desiring a society in accordance with Western principles such as

In 1947, the Bengali Muslims had identified themselves with Pakistan's Islamic project, but by the 1970s, the people of East Pakistan had given priority to their Bengali ethnicity over their religious identity, desiring a society in accordance with Western principles such as secularism

Secularism is the principle of seeking to conduct human affairs based on naturalistic considerations, uninvolved with religion. It is most commonly thought of as the separation of religion from civil affairs and the state and may be broadened ...

, democracy and socialism. Many Bengali Muslims strongly objected to the Islamist paradigm the Pakistani state imposed.

Most members of West Pakistan's ruling elite shared a vision of a liberal society, but nevertheless viewed a common faith as an essential mobilizing factor behind Pakistan's creation and the subsuming of Pakistan's multiple regional identities into one national identity. West Pakistanis were substantially more supportive than East Pakistanis of an Islamic state, a tendency that persisted after 1971.

Cultural and linguistic differences between the two wings gradually outweighed any sense of religious unity. The Bengalis took great pride in their culture and language which, with its Bengali script

The Bengali script or Bangla alphabet (, Romanization of Bengali, romanized: ''Bāṅlā bôrṇômālā'') is the standard writing system used to write the Bengali language, and has historically been used to write Sanskrit within Bengal. ...

and vocabulary

A vocabulary (also known as a lexicon) is a set of words, typically the set in a language or the set known to an individual. The word ''vocabulary'' originated from the Latin , meaning "a word, name". It forms an essential component of languag ...

, was unacceptable to the West Pakistani elite, who believed that it had assimilated considerable Hindu cultural influences. West Pakistanis, in an attempt to "Islamise" the East, wanted the Bengalis to adopt Urdu. The activities of the language movement nurtured a sentiment among Bengalis in favor of discarding Pakistan's communalism in favor of secular politics. The Awami League began propagating its secular message through its newspaper to the Bengali readership.

The Awami League's emphasis on secularism differentiated it from the Muslim League. In 1971, the Bangladeshi liberation struggle against Pakistan was led by secular leaders and secularists hailed the Bangladeshi victory as the triumph of secular Bengali nationalism over religion-centred Pakistani nationalism. While Pakistan's government strives for an Islamic state, Bangladesh was established secular. After the liberation victory, the Awami League attempted to build a secular order and the pro-Pakistan Islamist parties were barred from political participation. The majority of East Pakistani ulama

In Islam, the ''ulama'' ( ; also spelled ''ulema''; ; singular ; feminine singular , plural ) are scholars of Islamic doctrine and law. They are considered the guardians, transmitters, and interpreters of religious knowledge in Islam.

"Ulama ...

had either remained neutral or supported the Pakistani state, since they felt that the breakup of Pakistan would be detrimental for Islam.

Political differences

Although East Pakistan accounted for a slight majority of the country's population, political power remained in the hands of West Pakistanis. Since a straightforward system of representation based on population would have concentrated political power in East Pakistan, the West Pakistani establishment came up with the "

Although East Pakistan accounted for a slight majority of the country's population, political power remained in the hands of West Pakistanis. Since a straightforward system of representation based on population would have concentrated political power in East Pakistan, the West Pakistani establishment came up with the "One Unit

The One Unit Scheme (; ) was the reorganisation of the provinces of Pakistan by the central Pakistani government. It was led by Prime Minister Muhammad Ali Bogra on 22 November 1954 and passed on 30 September 1955. The government claimed tha ...

" scheme, whereby all of West Pakistan was considered one province. This was solely to counterbalance the East wing's votes.

After the 1951 assassination of Liaquat Ali Khan

Liaquat Ali Khan (1 October 189516 October 1951) was a Pakistani lawyer, politician and statesman who served as the first prime minister of Pakistan

The prime minister of Pakistan (, Roman Urdu, romanized: Wazīr ē Aʿẓam , ) is the he ...

, Pakistan's first prime minister, political power began to devolve to the new position of President of Pakistan

The president of Pakistan () is the head of state of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. The president is the nominal head of the executive and the supreme commander of the Pakistan Armed Forces.

, which replaced the office of Governor General

Governor-general (plural governors-general), or governor general (plural governors general), is the title of an official, most prominently associated with the British Empire. In the context of the governors-general and former British colonies, ...

when Pakistan became a republic, and, eventually, the military. The nominal elected chief executive, the Prime Minister, was frequently sacked by the establishment, acting through the President.

The East Pakistanis observed that the West Pakistani establishment swiftly deposed any East Pakistanis elected leader of Pakistan, such as Khawaja Nazimuddin

Sir Khawaja Nazimuddin (19 July 1894 – 22 October 1964), also spelled Khwaja Nazimuddin, was a Pakistani politician and statesman who served as the second Governor-General of Pakistan from 1948 to 1951, and later as the second Prime Minister ...

, Mohammad Ali Bogra

Syed Mohammad Ali Chowdhury Bogra (19 October 1909 – 23 January 1963) was an East Pakistani politician, statesman, and a diplomat who served as third prime minister of Pakistan from 1953 to 1955. He was appointed in this capacity in 1953 un ...

, Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy

Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy (8 September 18925 December 1963) was an East Pakistani barrister, politician and statesman who served as the Prime Minister of Pakistan from 1956 to 1957 and before that as the Prime Minister of Bengal from 1946 to ...

, and Iskander Mirza

Iskander Ali Mirza (13 November 189913 November 1969) was a Bengali politician, statesman and military general who served as the Dominion of Pakistan's fourth and last governor-general of Pakistan from 1955 to 1956, and then as the Islamic Repub ...

. Their suspicions were further aggravated by the military dictatorships of Ayub Khan (27 October 1958 – 25 March 1969) and Yahya Khan

Agha Muhammad Yahya Khan (4 February 191710 August 1980) was a Pakistani army officer who served as the third president of Pakistan from 1969 to 1971. He also served as the fifth Commander-in-Chief, Pakistan, commander-in-chief of the Pakistan ...

(25 March 1969 – 20 December 1971), both West Pakistanis. The situation reached a climax in 1970, when the Bangladesh Awami League

The Awami League, officially known as Bangladesh Awami League, is a major List of political parties in Bangladesh, political party in Bangladesh. The oldest existing political party in the country, the party played the leading role in achievin ...

, the largest East Pakistani political party, led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (17 March 1920 – 15 August 1975), also known by the honorific Bangabandhu, was a Bangladeshi politician, revolutionary, statesman and activist who was the founding president of Bangladesh. As the leader of Bangl ...

, won a landslide victory in the national elections. The party won 167 of the 169 seats allotted to East Pakistan, and thus a majority of the 313 seats in the National Assembly. This gave the Awami League the constitutional right to form a government. However, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (5 January 1928 – 4 April 1979) was a Pakistani barrister and politician who served as the fourth president of Pakistan from 1971 to 1973 and later as the ninth Prime Minister of Pakistan, prime minister of Pakistan from 19 ...

(a former Foreign Minister), the leader of the Pakistan People's Party

The Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) is a political party in Pakistan and one of the three major Pakistani political parties alongside the Pakistan Muslim League (N) and Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf. With a centre-left political position, it is cu ...

, refused to allow Rahman to become the Prime Minister of Pakistan.

Instead, he proposed the idea of having two Prime Ministers, one for each wing. The proposal elicited outrage in the east wing, already chafing under the other constitutional innovation, the "One Unit scheme". Bhutto also refused to accept Rahman's Six Points. On 3 March 1971, the two leaders of the two wings along with the President General Yahya Khan met in Dacca

Dhaka ( or ; , ), List of renamed places in Bangladesh, formerly known as Dacca, is the capital city, capital and list of cities and towns in Bangladesh, largest city of Bangladesh. It is one of the list of largest cities, largest and list o ...

to decide the fate of the country.

After their discussions yielded no satisfactory results, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman called for a nationwide strike. Bhutto feared a civil war, therefore, he sent his trusted companion, Mubashir Hassan

Mubashir Hassan (; 22 January 1922 – 14 March 2020) was a Pakistani politician, Humanism, humanist, political adviser, and an engineer who served in the capacity of Finance Minister of Pakistan, Finance Minister in Zulfikar Ali Bhutto#Prime M ...

. A message was conveyed, and Rahman decided to meet Bhutto. Upon his arrival, Rahman met with Bhutto and both agreed to form a coalition government with Rahman as premier and Bhutto as president, but Sheikh Mujib later ruled out such a possibility. Meanwhile, the military was unaware of these developments, and Bhutto increased his pressure on Rahman to reach a decision.

On 7 March 1971, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (soon to be prime minister) delivered a speech at the Racecourse Ground (now the Suhrawardy Udyan). In this speech he mentioned a further four-point condition to consider at the National Assembly Meeting on 25 March:

* The immediate lifting of martial law

Martial law is the replacement of civilian government by military rule and the suspension of civilian legal processes for military powers. Martial law can continue for a specified amount of time, or indefinitely, and standard civil liberties ...

.

* Immediate withdrawal of all military personnel to their barracks.

* An inquiry into the loss of life.

* Immediate transfer of power to the elected representative of the people before the assembly meeting 25 March.

He urged his people to turn every house into a fort of resistance. He closed his speech saying, "Our struggle is for our freedom. Our struggle is for our independence." This speech is considered the main event that inspired the nation to fight for its independence. General Tikka Khan

Tikka Khan, also known as the Butcher of Bengal.Tikka Khan title:

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

* (; 10 February 1915 – 28 March 2002) was a Pakistani military officer and war criminal who served as the first Chief of the Army Staff (Pakistan), chief of the a ...

was flown into Dacca to become Governor of East Bengal. East-Pakistani judges, including Justice Siddique, refused to swear him in.

Between 10 and 13 March, Pakistan International Airlines

Pakistan International Airlines, commonly known as PIA, is the flag carrier of Pakistan. With its primary hub at Jinnah International Airport in Karachi, the airline also operates from its secondary hubs at Allama Iqbal International Airport ...

canceled all its international routes to urgently fly "government passengers" to Dacca. These "government passengers" were almost all Pakistani soldiers in civilian dress. MV ''Swat'', a ship of the Pakistan Navy carrying ammunition and soldiers, was harbored in Chittagong

Chittagong ( ), officially Chattogram, (, ) (, or ) is the second-largest city in Bangladesh. Home to the Port of Chittagong, it is the busiest port in Bangladesh and the Bay of Bengal. The city is also the business capital of Bangladesh. It ...

Port, but the Bengali workers and sailors at the port refused to unload the ship. A unit of East Pakistan Rifles

East is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fact that eas ...

refused to obey commands to fire on the Bengali demonstrators, beginning a mutiny among the Bengali soldiers.

Response to the 1970 cyclone

The 1970 Bhola cyclone madelandfall

Landfall is the event of a storm moving over land after being over water. More broadly, and in relation to human travel, it refers to 'the first land that is reached or seen at the end of a journey across the sea or through the air, or the fact ...

on the East Pakistan coastline during the evening of 12 November, around the same time as a local high tide

Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravitational forces exerted by the Moon (and to a much lesser extent, the Sun) and are also caused by the Earth and Moon orbiting one another.

Tide tables ...

, killing an estimated 300,000 people. A 2017 World Meteorological Organization

The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for promoting international cooperation on atmospheric science, climatology, hydrology an ...

panel considers it the deadliest tropical cyclone

A tropical cyclone is a rapidly rotating storm system with a low-pressure area, a closed low-level atmospheric circulation, strong winds, and a spiral arrangement of thunderstorms that produce heavy rain and squalls. Depending on its locat ...

since at least 1873. A week after the landfall, President Khan conceded that his government had made "slips" and "mistakes" in its handling of the relief efforts due to a lack of understanding of the magnitude of the disaster.

A statement released by eleven political leaders in East Pakistan ten days after the cyclone hit charged the government with "gross neglect, callous and utter indifference". They also accused the president of playing down the magnitude of the problem in news coverage. On 19 November, students held a march in Dacca protesting the slowness of the government's response. Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani

Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani (12 December 1880 – 17 November 1976), also known reverentially as Maulana Bhashani, was a Bangladeshi politician and statesman who was one of the founder of the Awami League, the oldest and main political party in B ...

addressed a rally of 50,000 people on 24 November, where he accused the president of inefficiency and demanded his resignation.

As the conflict between East and West Pakistan developed in March, the Dacca offices of the two government organizations directly involved in relief efforts were closed for at least two weeks, first by a general strike

A general strike is a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large coalitions ...

and then by a ban on government work in East Pakistan by the Awami League

The Awami League, officially known as Bangladesh Awami League, is a major List of political parties in Bangladesh, political party in Bangladesh. The oldest existing political party in the country, the party played the leading role in achievin ...

. With this increase in tension, foreign personnel were evacuated over fears of violence. Relief work continued in the field, but long-term planning was curtailed. This conflict widened into the Bangladesh Liberation War in December and concluded with the creation of Bangladesh. This was one of the first times that a natural event helped trigger a civil war.

Operation Searchlight

Pakistan Army

The Pakistan Army (, ), commonly known as the Pak Army (), is the Land warfare, land service branch and the largest component of the Pakistan Armed Forces. The president of Pakistan is the Commander-in-chief, supreme commander of the army. The ...

—codenamed ''Operation Searchlight''—started on 25 March 1971 to curb the Bengali independence movement by taking control of the major cities on 26 March, and then eliminating all opposition, political or military, within one month. The Pakistani state used anti-Bihari violence by Bengalis in early March to justify Operation Searchlight.

Before the beginning of the operation, all foreign journalists were systematically deported from East Pakistan.

The main phase of Operation Searchlight ended with the fall of the last major town in Bengali hands in mid-May. The operation also began the Bangladesh genocide

The Bangladesh genocide was the ethnic cleansing of Bengalis residing in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) during the Bangladesh Liberation War, perpetrated by the Pakistan Army and the Razakar (Pakistan), Razakars. It began on 25 March 1971, as ...

. These systematic killings served only to enrage the Bengalis, resulting in East Pakistan's secession later that year. Bangladeshi media and reference books in English have published casualty figures that vary greatly, from 5,000 to 35,000 in Dacca, and 300,000 to 3,000,000 for Bangladesh as a whole. Independent researchers, including the British Medical Journal

''The BMJ'' is a fortnightly peer-reviewed medical journal, published by BMJ Publishing Group Ltd, which in turn is wholly-owned by the British Medical Association (BMA). ''The BMJ'' has editorial freedom from the BMA. It is one of the world ...

, have put forward figures ranging from 125,000 to 505,000. American political scientist

Political science is the scientific study of politics. It is a social science dealing with systems of governance and Power (social and political), power, and the analysis of political activities, political philosophy, political thought, polit ...

Rudolph Rummel

Rudolph Joseph Rummel (October 21, 1932 – March 2, 2014) was an American political scientist, a statistician and professor at Indiana University, Yale University, and University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. He spent his career studying data on collect ...

puts total deaths at 1.5 million. The atrocities have been called acts of genocide

Genocide is violence that targets individuals because of their membership of a group and aims at the destruction of a people. Raphael Lemkin, who first coined the term, defined genocide as "the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group" by ...

.

According to the ''Asia Times:''

Although the violence focused on the provincial capital, Dacca, it also affected all parts of East Pakistan. Residential halls of the University of Dacca

The University of Dhaka (), also known as Dhaka University (DU), is a public research university located in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Established in 1921, it is the oldest active university in the country.

The University of Dhaka was founded in 1921 ...

were particularly targeted. The only Hindu residential hall—Jagannath Hall

Jagannath Hall of Dhaka University is a residence hall for students from religious minorities, including Buddhists, Christian, and Hindus. It is one of the three original residence halls that date from the founding of the university in 1921, and ...

—was destroyed by the Pakistani armed forces, and an estimated 600 to 700 of its residents were murdered. The Pakistani army denied any cold-blooded killings at the university, but the Hamoodur Rahman Commission in Pakistan concluded that overwhelming force was used. This fact, and the massacre at Jagannath Hall and nearby student dormitories of Dacca University, are corroborated by a videotape secretly filmed by Professor Nurul Ula of the East Pakistan University of Engineering and Technology, whose residence was directly opposite the student dormitories.

The scale of the atrocities was first made clear in the West, when Anthony Mascarenhas, a Pakistani journalist who had been sent to the province by the military authorities to write a story favorable to Pakistan, instead fled to the United Kingdom and, on 13 June 1971, published an article in ''The Sunday Times

''The Sunday Times'' is a British Sunday newspaper whose circulation makes it the largest in Britain's quality press market category. It was founded in 1821 as ''The New Observer''. It is published by Times Newspapers Ltd, a subsidiary of N ...

'' describing the systematic killings by the military. The BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

wrote: "There is little doubt that Mascarenhas' reportage played its part in ending the war. It helped turn world opinion against Pakistan and encouraged India to play a decisive role", with Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi

Indira Priyadarshini Gandhi (Given name, ''née'' Nehru; 19 November 1917 – 31 October 1984) was an Indian politician and stateswoman who served as the Prime Minister of India, prime minister of India from 1966 to 1977 and again from 1980 un ...

saying that Mascarenhas' article led her "to prepare the ground for India's armed intervention".

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was arrested by the Pakistani Army. Yahya Khan appointed Brigadier (later General) Rahimuddin Khan

Rahimuddin Khan (21 July 1926 – 22 August 2022) was a four-star rank Pakistani general who briefly served as the 16th Governor of Sindh in 1988. Previously, he had served as the fourth Chairman Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee from 1984 to 19 ...

to preside over a special tribunal prosecuting Rahman with multiple charges. The tribunal's sentence was never made public, but Yahya caused the verdict to be held in abeyance in any case. Other Awami League leaders were arrested as well, while a few fled Dacca to avoid arrest. The Awami League was banned by General Yahya Khan.

Declaration of independence

The violence unleashed by the Pakistani forces on 25 March 1971 proved the last straw to the efforts to negotiate a settlement. Following these incidents, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman signed an official declaration that read:

Sheikh Mujib also called upon the people to resist the occupation forces through a radio message. Rahman was arrested on the night of 25–26 March 1971 at about 1:30 am (as per Radio Pakistan's news on 29 March 1971).

A telegram containing the text of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's declaration reached some students in

The violence unleashed by the Pakistani forces on 25 March 1971 proved the last straw to the efforts to negotiate a settlement. Following these incidents, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman signed an official declaration that read:

Sheikh Mujib also called upon the people to resist the occupation forces through a radio message. Rahman was arrested on the night of 25–26 March 1971 at about 1:30 am (as per Radio Pakistan's news on 29 March 1971).

A telegram containing the text of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's declaration reached some students in Chittagong

Chittagong ( ), officially Chattogram, (, ) (, or ) is the second-largest city in Bangladesh. Home to the Port of Chittagong, it is the busiest port in Bangladesh and the Bay of Bengal. The city is also the business capital of Bangladesh. It ...

. The message was translated into Bengali by Manjula Anwar. The students failed to secure permission from higher authorities to broadcast the message from the nearby Agrabad Station of Pakistan Broadcasting Corporation

The Pakistan Broadcasting Corporation (); also known as ''Radio Pakistan'', serves as the national public broadcaster for radio in Pakistan. Although some local stations predate its founding, it is the oldest existing broadcasting network in P ...

, but the message was read several times by the independent Swadhin Bangla Betar Kendro Radio established by rebel Bangali Radio workers in Kalurghat. Major Ziaur Rahman

Ziaur Rahman (19 January 193630 May 1981) was a Bangladeshi military officer and politician who served as the sixth president of Bangladesh from 1977 until Assassination of Ziaur Rahman, his assassination in 1981. One of the leading figures of t ...

was requested to provide security for the station and also read the Declaration on 27 March 1971. He broadcast the announcement of the declaration of independence on behalf of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman:

The Kalurghat Radio Station's transmission capability was limited, but the message was picked up by a Japanese ship in the Bay of Bengal

The Bay of Bengal is the northeastern part of the Indian Ocean. Geographically it is positioned between the Indian subcontinent and the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese peninsula, located below the Bengal region.

Many South Asian and Southe ...

. It was then re-transmitted by Radio Australia

ABC Radio Australia, also known as Radio Australia, is the international broadcasting and online service operated by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC), Australia's public broadcaster. Most programming is in English, with some in Tok ...

and later by the BBC.

M. A. Hannan, an Awami League leader from Chittagong, is said to have made the first announcement of the declaration of independence over the radio on 26 March 1971.

26 March 1971 is considered the official Independence Day of Bangladesh, and the name Bangladesh was in effect henceforth. In July 1971, Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi

Indira Priyadarshini Gandhi (Given name, ''née'' Nehru; 19 November 1917 – 31 October 1984) was an Indian politician and stateswoman who served as the Prime Minister of India, prime minister of India from 1966 to 1977 and again from 1980 un ...

openly referred to the former East Pakistan as Bangladesh. Some Pakistani and Indian officials continued to use the name "East Pakistan" until 16 December 1971.

Liberation War

March–June

At first, resistance was spontaneous and disorganized, and was not expected to be prolonged. But when the Pakistani Army cracked down upon the population, resistance grew. TheMukti Bahini

The Mukti Bahini, initially called the Mukti Fauj, also known as the Bangladesh Forces, was a big tent armed guerrilla resistance movement consisting of the Bangladeshi military personnel, paramilitary personnel and civilians during the Ba ...

became increasingly active. The Pakistani military sought to quell them, but increasingly many Bengali soldiers defected to this underground "Bangladesh army". These Bengali units slowly merged into the Mukti Bahini and bolstered their weaponry with supplies from India. Pakistan responded by airlifting in two infantry divisions and reorganizing their forces. They also raised paramilitary forces of Razakars, Al-Badrs and Al-Shams (mostly members of the Muslim League and other Islamist groups), as well as other Bengalis who opposed independence, and Bihar

Bihar ( ) is a states and union territories of India, state in Eastern India. It is the list of states and union territories of India by population, second largest state by population, the List of states and union territories of India by are ...

i Muslims who had settled during the time of partition.

On 17 April 1971, a provisional government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, a transitional government or provisional leadership, is a temporary government formed to manage a period of transition, often following state collapse, revoluti ...

was formed in Meherpur District

Meherpur District () is a northwestern district of Khulna Division in southwestern Bangladesh. It is bordered by West Bengal, India in the west, and by the Bangladeshi districts of Kushtia and Chuadanga to the east. Pre-independence Meherpur was ...

in western Bangladesh bordering India with Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, who was in prison in Pakistan, as president, Syed Nazrul Islam

Syed Nazrul Islam (1925 – 3 November 1975) was a Bangladeshi politician and a senior leader of the Awami League. During the Bangladesh War of Independence, he was declared as the Acting President of Bangladesh by the Provisional Government.

...

as acting president, Tajuddin Ahmad

Tajuddin Ahmad (23 July 1925 – 3 November 1975) was a Bangladeshi politician. He led the Provisional Government of Bangladesh, 1st Government of Bangladesh as its Prime Minister of Bangladesh, prime minister during the Bangladesh Liberation W ...

as prime minister, and General Muhammad Ataul Ghani Osmani as Commander-in-Chief, Bangladesh Forces. As fighting grew between the occupation army and the Bengali Mukti Bahini, an estimated 10 million Bengalis sought refuge in the Indian states of Assam and West Bengal.

June–September

Bangladesh forces command was set up on 11 July, with Col.

Bangladesh forces command was set up on 11 July, with Col. M. A. G. Osmani

Muhammad Ataul Gani Osmani (1 September 1918 – 16 February 1984) was a Bangladeshi Officer (armed forces), military officer, revolutionary and politician. His military career spanned three decades, beginning with his service in the Briti ...

as commander-in-chief (C-in-C) with the status of Cabinet Minister, Lt. Col. Abdur Rabb as chief of Staff (COS), Group Captain A. K. Khandker as Deputy Chief of Staff (DCOS) and Major A. R. Chowdhury as Assistant Chief of Staff (ACOS).

Osmani had differences of opinion with the Indian leadership about the role of the Mukti Bahini in the conflict. Indian leadership initially envisioned a well trained force of 8,000 guerrillas, operating in small cells around Bangladesh to facilitate eventual conventional combat. With the Bangladesh government in exile, Osmani favored a different strategy:

* Bengali conventional forces would occupy lodgments inside Bangladesh and the Bangladesh government would request international diplomatic recognition

Diplomatic recognition in international law is a unilateral declarative political act of a state that acknowledges an act or status of another state or government in control of a state (may be also a recognized state). Recognition can be acc ...

and intervention. Initially Mymensingh

Mymensingh () is a metropolis, metropolitan city and capital of Mymensingh Division, Bangladesh. Located on the bank of the Old Brahmaputra River, Brahmaputra River, about north of the national capital Dhaka, it is a major financial center ...

was picked for this operation, but Osmani later settled on Sylhet.

* Sending the maximum number of guerrillas into Bangladesh as soon as possible with the following objectives:

** Increasing Pakistani casualties through raids and ambush.

** Cripple economic activity by hitting power stations, railway lines, storage depots and communication networks.

** Destroy Pakistan Army mobility by blowing up bridges/culverts, fuel depots, trains and river crafts.

** The strategic objective was to make the Pakistanis spread their forces inside the province, so attacks could be made on isolated Pakistani detachments.

Bangladesh was divided into eleven sectors in July, each with a commander chosen from defected officers of the Pakistani army who joined the Mukti Bahini to lead guerrilla operations. The Mukti Bahini forces were given two to five weeks of training by the Indian army on guerrilla warfare. Most of their training camps were near the border area and operated with assistance from India. The 10th Sector was placed under Osmani's command and included the Naval Commandos and C-in-C's special force. Three brigades (eventually 8 battalions) were raised for conventional warfare; a large guerrilla force (estimated at 100,000) was trained.

Five infantry battalions were reformed and positioned along the northern and eastern borders of Bangladesh. Three more battalions were raised, and artillery batteries were formed. During June and July, Mukti Bahini regrouped across the border with Indian aid through Operation Jackpot and began sending 2,000–5,000 guerrillas across the border, the so-called Monsoon Offensive, which for various reasons (lack of proper training, supply shortage, lack of a proper support network inside Bangladesh) failed to achieve its objectives. Bengali regular forces also attacked border outposts in Mymensingh

Mymensingh () is a metropolis, metropolitan city and capital of Mymensingh Division, Bangladesh. Located on the bank of the Old Brahmaputra River, Brahmaputra River, about north of the national capital Dhaka, it is a major financial center ...

, Comilla

Comilla (), officially spelled Cumilla, is a metropolis on the banks of the Gomti River in eastern Bangladesh. Comilla was one of the cities of ancient Bengal. It was once the capital of Tripura kingdom. Comilla Airport is located in the Duli ...

and Sylhet

Sylhet (; ) is a Metropolis, metropolitan city in the north eastern region of Bangladesh. It serves as the administrative center for both the Sylhet District and the Sylhet Division. The city is situated on the banks of the Surma River and, as o ...

, but the results were mixed. Pakistani authorities concluded that they had successfully contained the Monsoon Offensive, which proved a near-accurate observation.

Guerrilla operations, which slackened during the training phase, picked up after August. Economic and military targets in Dacca were attacked. The major success story was Operation Jackpot, in which naval commandos mined and blew up berthed ships in Chittagong, Mongla, Narayanganj

Narayanganj () is a city in central Bangladesh in the Greater Dhaka area. It is in the Narayanganj District, about southeast of the capital city of Dhaka. With a population of almost 1 million, it is the 6th largest city in Bangladesh. It is als ...

and Chandpur on 15 August 1971.

October–December

Bangladeshi conventional forces attacked border outposts. Kamalpur, Belonia and theBattle of Boyra

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

are a few examples. 90 out of 370 border outposts fell to Bengali forces. Guerrilla attacks intensified, as did Pakistani and Razakar reprisals on civilian populations. Pakistani forces were reinforced by eight battalions from West Pakistan. The Bangladeshi independence fighters even managed to temporarily capture airstrips at Lalmonirhat and Shalutikar. Both of these were used for flying in supplies and arms from India. Pakistan sent another five battalions from West Pakistan as reinforcements.

Indian involvement

Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi concluded that instead of taking in millions of refugees, India would be economically better off going to war against Pakistan. As early as 28 April 1971, the Indian Cabinet had asked General Manekshaw (

Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi concluded that instead of taking in millions of refugees, India would be economically better off going to war against Pakistan. As early as 28 April 1971, the Indian Cabinet had asked General Manekshaw (Chairman of the Chiefs of Staff Committee

The Chiefs of Staff Committee (COSC) is an administrative forum of the senior-most military leaders of the Indian Armed Forces, which advises the Government of India on all military and strategic matters deemed privy to military coordination, ...

) to "Go into East Pakistan". Hostile relations in the past between India and Pakistan added to India's decision to intervene in Pakistan's civil war.

As a result, the Indian government decided to support the creation of a separate state for ethnic Bengalis by supporting the Mukti Bahini

The Mukti Bahini, initially called the Mukti Fauj, also known as the Bangladesh Forces, was a big tent armed guerrilla resistance movement consisting of the Bangladeshi military personnel, paramilitary personnel and civilians during the Ba ...

. RAW helped to organize, train and arm these insurgents. Consequently, the Mukti Bahini succeeded in harassing Pakistani military in East Pakistan, creating conditions conducive to a full-scale Indian military intervention in early December.

The Pakistan Air Force

The Pakistan Air Force (PAF) (; ) is the aerial warfare branch of the Pakistan Armed Forces, tasked primarily with the aerial defence of Pakistan, with a secondary role of providing air support to the Pakistan Army and Pakistan Navy when re ...

(PAF) launched a preemptive strike on Indian Air Force bases on 3 December 1971. The attack was modeled on the Israeli Air Force

The Israeli Air Force (IAF; , commonly known as , ''Kheil HaAvir'', "Air Corps") operates as the aerial and space warfare branch of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF). It was founded on May 28, 1948, shortly after the Israeli Declaration of Indep ...

's Operation Focus

Operation Focus (, ''Mivtza Moked'') was the opening airstrike by Israel at the start of the Six-Day War in 1967. It is sometimes referred to as the "Sinai Air Strike". At 07:45 on 5 June 1967, the Israeli Air Force (IAF) under Maj. Gen. Morde ...

during the Six-Day War

The Six-Day War, also known as the June War, 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states, primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, Syria, and Jordan from 5 to 10June ...

and intended to neutralize the Indian Air Force

The Indian Air Force (IAF) (ISO 15919, ISO: ) is the air force, air arm of the Indian Armed Forces. Its primary mission is to secure Indian airspace and to conduct aerial warfare during armed conflicts. It was officially established on 8 Octob ...

planes on the ground. India saw the strike as an open act of unprovoked aggression, which marked the official start of the Indo-Pakistani War. In response to the attack, both India and Pakistan formally acknowledged the "existence of a state of war between the two countries" even though neither government had formally issued a declaration of war

A declaration of war is a formal act by which one state announces existing or impending war activity against another. The declaration is a performative speech act (or the public signing of a document) by an authorized party of a national gov ...

.

Three Indian corps

Corps (; plural ''corps'' ; from French , from the Latin "body") is a term used for several different kinds of organization. A military innovation by Napoleon I, the formation was formally introduced March 1, 1800, when Napoleon ordered Gener ...

were involved in the liberation of East Pakistan. They were supported by nearly three brigade

A brigade is a major tactical military unit, military formation that typically comprises three to six battalions plus supporting elements. It is roughly equivalent to an enlarged or reinforced regiment. Two or more brigades may constitute ...

s of Mukti Bahini fighting alongside them, and many more who were fighting irregularly. That was far superior to the Pakistani army of three divisions

Division may refer to:

Mathematics

*Division (mathematics), the inverse of multiplication

* Division algorithm, a method for computing the result of mathematical division Military

*Division (military), a formation typically consisting of 10,000 t ...

. The Indians quickly overran the country, selectively engaging or bypassing heavily defended strongholds. Pakistani forces were unable to effectively counter the Indian attack, as they had been deployed in small units around the border to counter the guerrilla attacks by the Mukti Bahini. Unable to defend Dacca, the Pakistanis surrendered on 16 December 1971.

Air and naval war

The Indian Air Force carried out several sorties against Pakistan, and within a week, IAF aircraft dominated the skies of East Pakistan. It achieved near-totalair supremacy

Air supremacy (as well as air superiority) is the degree to which a side in a conflict holds control of air power over opposing forces. There are levels of control of the air in aerial warfare. Control of the air is the aerial equivalent of ...

by the end of the first week, as the entire Pakistani air contingent in the east, PAF No.14 Squadron, was grounded because of Indian and Bangladeshi airstrikes at Tejgaon, Kurmitola, Lalmonirhat and Shamsher Nagar. Sea Hawks from the carrier also struck Chittagong, Barisal

Barisal ( or ; , ), officially known as Barishal, is a major city that lies on the banks of the Kirtankhola river in south-central Bangladesh. It is the largest city and the administrative headquarter of both Barisal District and Barisal Divi ...

and Cox's Bazar

Cox's Bazar (; ; ) is a city, fishing port, tourism centre, and Cox's Bazar District, district headquarters in south-eastern Bangladesh. Cox's Bazar Beach, one of the most popular tourist attractions in Bangladesh, is the longest uninterrupte ...

, destroying the eastern wing of the Pakistan Navy

The Pakistan Navy (PN) (; ''romanized'': Pākistān Bahrí'a; ) is the naval warfare branch of the Pakistan Armed Forces. The Chief of the Naval Staff, a four-star admiral, commands the navy and is a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Com ...

and effectively blockading the East Pakistan ports, cutting off any escape routes for the stranded Pakistani soldiers. The nascent Bangladesh Navy

The Bangladesh Navy () is the naval warfare branch of the Bangladesh Armed Forces, responsible for the defence of Bangladesh's of maritime territorial area from any external threat, the security of sea ports and exclusive economic zones of Ban ...

(comprising officers and sailors who defected from the Pakistani Navy) aided the Indians in the marine warfare, carrying out attacks, most notably Operation Jackpot.

Surrender and aftermath

On 16 December 1971, Lt. Gen Amir Abdullah Khan Niazi,

On 16 December 1971, Lt. Gen Amir Abdullah Khan Niazi, Chief Martial Law Administrator

The office of the chief martial law administrator (CMLA) was a senior and authoritative post created in countries such as Pakistan, Bangladesh and Indonesia that gave considerable executive authority and powers to the holder of the post to enforc ...

of East Pakistan

East Pakistan was the eastern province of Pakistan between 1955 and 1971, restructured and renamed from the province of East Bengal and covering the territory of the modern country of Bangladesh. Its land borders were with India and Burma, wit ...

and Commander of Pakistan Army forces in East Pakistan signed the Instrument of Surrender. At the time of surrender only a few countries had provided diplomatic recognition

Diplomatic recognition in international law is a unilateral declarative political act of a state that acknowledges an act or status of another state or government in control of a state (may be also a recognized state). Recognition can be acc ...

to the new nation. Over 93,000 Pakistani troops surrendered to the Indian forces and Bangladesh Liberation forces, making it the largest surrender since World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

Bangladesh sought admission to the UN with most voting in its favor. China vetoed this as Pakistan was its key ally. The United States, also a key ally of Pakistan, was one of the last nations to accord Bangladesh recognition. To ensure a smooth transition, in 1972 the Simla Agreement

The Simla Agreement, also spelled Shimla Agreement, was a peace treaty signed between India and Pakistan on 2 July 1972 in Shimla, the capital of Himachal Pradesh. It followed the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971, which began after India interv ...

was signed between India and Pakistan. The treaty ensured that Pakistan recognized the independence of Bangladesh in exchange for the return of the Pakistani PoWs

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war for a ...

.

India treated all the PoWs in strict accordance with the Geneva Convention, rule 1925. It released more than 93,000 Pakistani PoWs in five months. Further, as a gesture of goodwill, nearly 200 soldiers who were sought for war crimes by Bengalis were pardoned by India. The accord also gave back of land that Indian troops had seized in West Pakistan during the war, though India retained a few strategic areas, most notably Kargil

Kargil or Kargyil is a City in Indian-administered Ladakh in the disputed Kashmir region. The application of the term "administered" to the various regions of Kashmir and a mention of the Kashmir dispute is supported by the WP:TERTIARY, tert ...

(which was in turn the focal point of a war between the two nations in 1999). This was done as a measure of promoting "lasting peace" and acknowledged by many observers as a sign of maturity by India. But some in India felt the treaty had been too lenient to Bhutto, who had pleaded for leniency, arguing that the fragile democracy in Pakistan would crumble if Pakistanis perceived the accord as overly harsh.

Reaction in West Pakistan to the war

Reaction to the defeat and dismemberment of half the nation was a shocking loss to top military and civilians alike. Few had expected that they would lose the formal war in under a fortnight, and there was also unsettlement over what was perceived as a meek surrender of the army in East Pakistan.Yahya Khan

Agha Muhammad Yahya Khan (4 February 191710 August 1980) was a Pakistani army officer who served as the third president of Pakistan from 1969 to 1971. He also served as the fifth Commander-in-Chief, Pakistan, commander-in-chief of the Pakistan ...

's dictatorship collapsed and gave way to Bhutto, who took the opportunity to rise to power.