Britain Awake on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

"Britain Awake" (also known as the Iron Lady speech) was a speech made by

"Britain Awake" (also known as the Iron Lady speech) was a speech made by

Thatcher made the speech on the evening of 19 January 1976. The address had been written beforehand, and a copy given to the press with an embargo of 8 pm. A comparison between the

Thatcher made the speech on the evening of 19 January 1976. The address had been written beforehand, and a copy given to the press with an embargo of 8 pm. A comparison between the  Thatcher criticised détente as providing only an illusion of safety and noted that it had not prevented Soviet intervention in the

Thatcher criticised détente as providing only an illusion of safety and noted that it had not prevented Soviet intervention in the

"Britain Awake" (also known as the Iron Lady speech) was a speech made by

"Britain Awake" (also known as the Iron Lady speech) was a speech made by British Conservative Party

The Conservative Party, officially the Conservative and Unionist Party and also known colloquially as the Tories, is one of the two main political parties in the United Kingdom, along with the Labour Party. It is the current governing party, ...

leader Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990. She was the first female British prime ...

at Kensington Town Hall

Kensington is a district in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea in the West of Central London.

The district's commercial heart is Kensington High Street, running on an east–west axis. The north-east is taken up by Kensington Gardens ...

, London, on 19 January 1976. The speech was strongly anti-Soviet

Anti-Sovietism, anti-Soviet sentiment, called by Soviet authorities ''antisovetchina'' (russian: антисоветчина), refers to persons and activities actually or allegedly aimed against the Soviet Union or government power within the S ...

, with Thatcher stating that the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

was "bent on world domination

World domination (also called global domination or world conquest or cosmocracy) is a hypothetical power structure, either achieved or aspired to, in which a single political authority holds the power over all or virtually all the inhabitants ...

" and taking advantage of détente

Détente (, French: "relaxation") is the relaxation of strained relations, especially political ones, through verbal communication. The term, in diplomacy, originates from around 1912, when France and Germany tried unsuccessfully to reduce ...

to make gains in the Angolan Civil War

The Angolan Civil War ( pt, Guerra Civil Angolana) was a civil war in Angola, beginning in 1975 and continuing, with interludes, until 2002. The war immediately began after Angola became independent from Portugal in November 1975. The war wa ...

. She questioned the British Labour government's defence cuts and the state of the NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

defences in parts of Europe. Thatcher stated that a Conservative government would align its foreign policy with the United States and increase defence spending. She also congratulated Malcolm Fraser

John Malcolm Fraser (; 21 May 1930 – 20 March 2015) was an Australian politician who served as the 22nd prime minister of Australia from 1975 to 1983, holding office as the leader of the Liberal Party of Australia.

Fraser was raised on hi ...

and Robert Muldoon

Sir Robert David Muldoon (; 25 September 19215 August 1992) was a New Zealand politician who served as the 31st Prime Minister of New Zealand, from 1975 to 1984, while leader of the National Party.

Serving as a corporal and sergeant in t ...

for their recent election as prime minister of Australia and New Zealand, respectively, but warned of the risks of a potential communist victory in the upcoming 1976 Italian general election

The 1976 Italian general election was held in Italy on 20 June 1976.Dieter Nohlen & Philip Stöver (2010) ''Elections in Europe: A data handbook'', p1048 It was the first election after the voting age was lowered to 18.

The Christian Democracy re ...

. Thatcher urged the British public to wake from "a long sleep" and make a choice that "will determine the life or death of our kind of society".

The speech was reported on in the Soviet press

Printed media in the Soviet Union, i.e., newspapers, magazines and journals, were under strict control of the Communist Party and the Soviet state. The desire to disseminate propaganda is believed to have been the driving force behind the creatio ...

, including by Yuri Gavrilov in the ''Krasnaya Zvezda

''Krasnaya Zvezda'' (russian: Кра́сная звезда́, literally "Red Star") is the official newspaper of the Soviet and later Russian Ministry of Defence. Today its official designation is "Central Organ of the Russian Ministry of Def ...

'' who dubbed Thatcher the "Iron Lady", a term also used afterwards by the news agency TASS

The Russian News Agency TASS (russian: Информацио́нное аге́нтство Росси́и ТАСС, translit=Informatsionnoye agentstvo Rossii, or Information agency of Russia), abbreviated TASS (russian: ТАСС, label=none) ...

. The Soviet reporting, including the nickname, was discussed in a Reuters

Reuters ( ) is a news agency owned by Thomson Reuters Corporation. It employs around 2,500 journalists and 600 photojournalists in about 200 locations worldwide. Reuters is one of the largest news agencies in the world.

The agency was est ...

story that Western outlets picked up. The British press adopted the term as a mark of the strength of Thatcher's anti-communist

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when the United States and th ...

stance, and she approved of its use.

Background

Thatcher had been a Conservative Party member of Parliament since 1959 and had served as Secretary of State for Education and Science inEdward Heath's government

Edward Heath of the Conservative Party formed the Heath ministry and was appointed Prime Minister of the United Kingdom by Queen Elizabeth II on 19 June 1970, following the 18 June general election. Heath's ministry ended after the February ...

. After Heath lost the February and October 1974 general elections, Thatcher challenged him for the leadership of the party. Her policy positions, including her support for economic liberalism

Economic liberalism is a political and economic ideology that supports a market economy based on individualism and private property in the means of production. Adam Smith is considered one of the primary initial writers on economic liberalis ...

, won her the backing of the party's right wing. She was elected party leader in February 1975, becoming Leader of the Opposition

The Leader of the Opposition is a title traditionally held by the leader of the largest political party not in government, typical in countries utilizing the parliamentary system form of government. The leader of the opposition is typically se ...

..

Foreign relations in this period were dominated by the Cold War, a confrontation between the West and the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

(USSR) and its allies. By 1975 détente

Détente (, French: "relaxation") is the relaxation of strained relations, especially political ones, through verbal communication. The term, in diplomacy, originates from around 1912, when France and Germany tried unsuccessfully to reduce ...

, a period of supposedly more friendly relations between the superpowers, was the principal position. At the time, some considered that détente could lead to the end of the Cold War. Thatcher had made few speeches on foreign policy by 1975. However, it was known that she was sceptical of Soviet intentions to keep the terms of the 1975 Helsinki Accords

The Helsinki Final Act, also known as Helsinki Accords or Helsinki Declaration was the document signed at the closing meeting of the third phase of the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE) held in Helsinki, Finland, betwee ...

, a move towards more extensive détente.

In September 1975, Thatcher carried out a tour of the United States and Canada, meeting with senior figures such as UN secretary-general Kurt Waldheim

Kurt Josef Waldheim (; 21 December 1918 – 14 June 2007) was an Austrian politician and diplomat. Waldheim was the Secretary-General of the United Nations from 1972 to 1981 and president of Austria from 1986 to 1992. While he was running for th ...

and US president Gerald Ford

Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr. ( ; born Leslie Lynch King Jr.; July 14, 1913December 26, 2006) was an American politician who served as the 38th president of the United States from 1974 to 1977. He was the only president never to have been elected ...

. During this tour, she met US defence secretary James R. Schlesinger, a noted opponent of détente, and Treasury secretary William E. Simon, a prominent economic liberalist. During the tour, she made a speech at the Washington Press Club

The National Press Club is a professional organization and social community in Washington, D.C. for journalists and communications professionals. It hosts public and private gatherings with invited speakers from public life. The club also offers e ...

setting out her commitment to roll back socialism in Britain and rejuvenate the country through economic liberalism. She mentioned her views on détente and cautioned about the risks of such a strategy. Still, the main focus was on her proposed domestic reforms and Britain's continuing relationship with the US.

Thatcher's appearances in this period were managed by her public relations

Public relations (PR) is the practice of managing and disseminating information from an individual or an organization (such as a business, government agency, or a nonprofit organization) to the public in order to influence their perception. ...

adviser Gordon Reece. On 19 January 1976 she was due to make a speech at Kensington Town Hall

Kensington is a district in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea in the West of Central London.

The district's commercial heart is Kensington High Street, running on an east–west axis. The north-east is taken up by Kensington Gardens ...

in London, one of her first major speeches as party leader.

Speech

Thatcher made the speech on the evening of 19 January 1976. The address had been written beforehand, and a copy given to the press with an embargo of 8 pm. A comparison between the

Thatcher made the speech on the evening of 19 January 1976. The address had been written beforehand, and a copy given to the press with an embargo of 8 pm. A comparison between the press release

A press release is an official statement delivered to members of the news media for the purpose of providing information, creating an official statement, or making an announcement directed for public release. Press releases are also consider ...

and the speech as made reveals few differences, and those of a mainly stylistic nature.

Thatcher opened the speech by stating that the first duty of any government was to defend its people from external threats and asked rhetorically if the current Labour government was doing so. She accused prime minister Harold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx, (11 March 1916 – 24 May 1995) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from October 1964 to June 1970, and again from March 1974 to April 1976. He ...

of cutting defence budgets at a time when the government faced its greatest external threat since the Second World War, that of the Soviet Union. Thatcher accused some members of the Labour Party of siding with the Soviets, who she stated was a dictatorship intent on becoming the leading military power in the world and "bent on world domination

World domination (also called global domination or world conquest or cosmocracy) is a hypothetical power structure, either achieved or aspired to, in which a single political authority holds the power over all or virtually all the inhabitants ...

". Thatcher noted that as a dictatorship, "the men in the Soviet politburo

The Political Bureau of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (, abbreviated: ), or Politburo ( rus, Политбюро, p=pəlʲɪtbʲʊˈro) was the highest policy-making authority within the Communist Party of th ...

don't have to worry about the ebb and flow of public opinion. They put guns before butter, while we put just about everything before guns".

Thatcher stated that as the Soviet Union had failed in economic and human terms, its only recourse to become a superpower was military means. She stated that she had warned the world before Helskini that the USSR was outspending the US in military research, weaponry, ships and strategic nuclear weapons and that some experts considered that the USSR had achieved strategic superiority over the US. Thatcher noted that she would attend British Army wargames in Germany in three days at a point when the USSR had an advantage of 150,000 men, 10,000 tanks and 2,600 aircraft over NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

in Europe. Thatcher raised concerns over the strength of NATO defences in Southern Europe, the Mediterranean, oil rigs and sea trade route

A sea lane, sea road or shipping lane is a regularly used navigable route for large water vessels (ships) on wide waterways such as oceans and large lakes, and is preferably safe, direct and economic. During the Age of Sail, they were determined b ...

s. She lamented the loss of British naval base

A naval base, navy base, or military port is a military base, where warships and naval ships are docked when they have no mission at sea or need to restock. Ships may also undergo repairs. Some naval bases are temporary homes to aircraft that us ...

s overseas when the USSR was constructing new bases.

Thatcher criticised détente as providing only an illusion of safety and noted that it had not prevented Soviet intervention in the

Thatcher criticised détente as providing only an illusion of safety and noted that it had not prevented Soviet intervention in the Angolan Civil War

The Angolan Civil War ( pt, Guerra Civil Angolana) was a civil war in Angola, beginning in 1975 and continuing, with interludes, until 2002. The war immediately began after Angola became independent from Portugal in November 1975. The war wa ...

or led to an improvement in living conditions behind the Iron Curtain

The Iron Curtain was the political boundary dividing Europe into two separate areas from the end of World War II in 1945 until the end of the Cold War in 1991. The term symbolizes the efforts by the Soviet Union (USSR) to block itself and its s ...

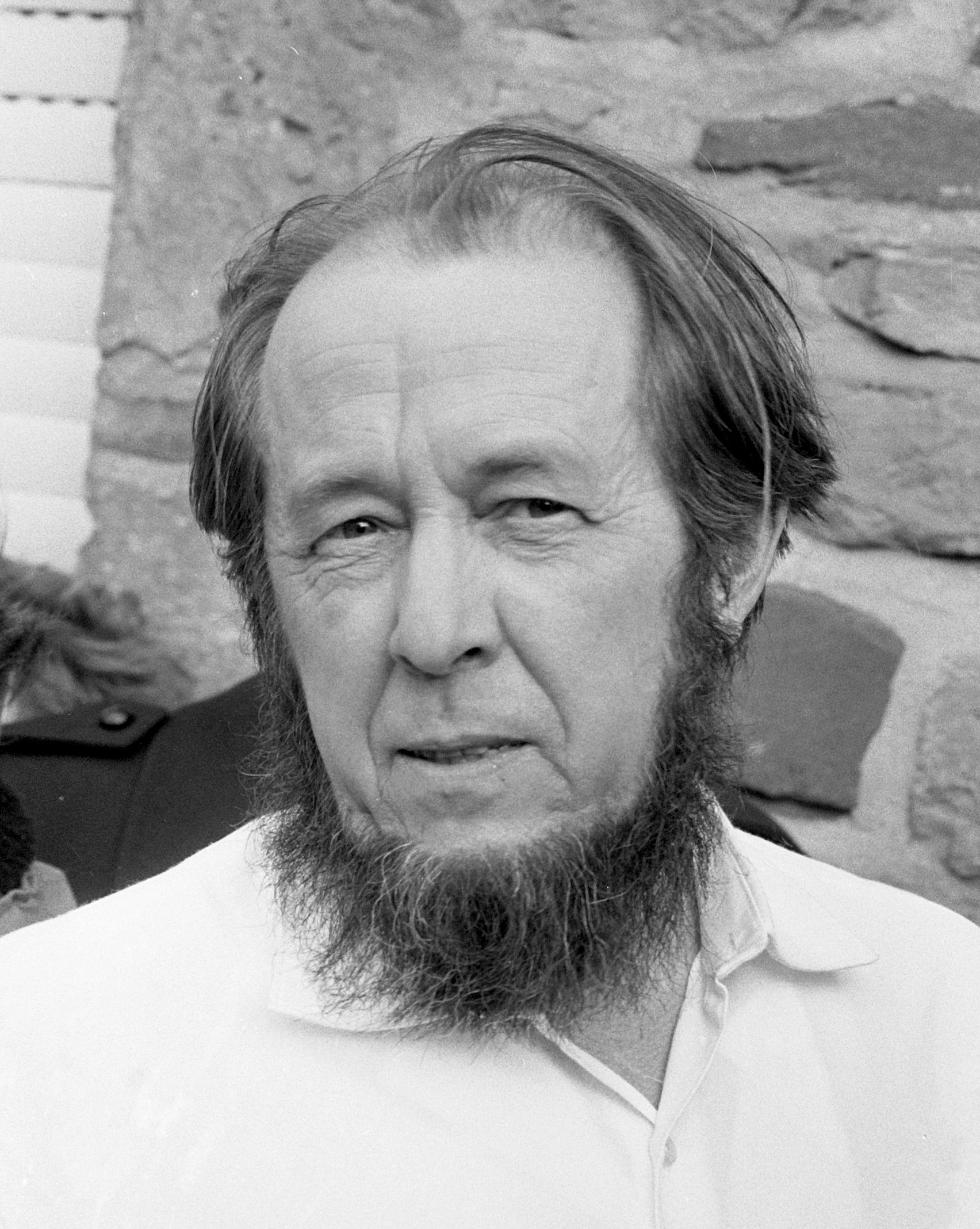

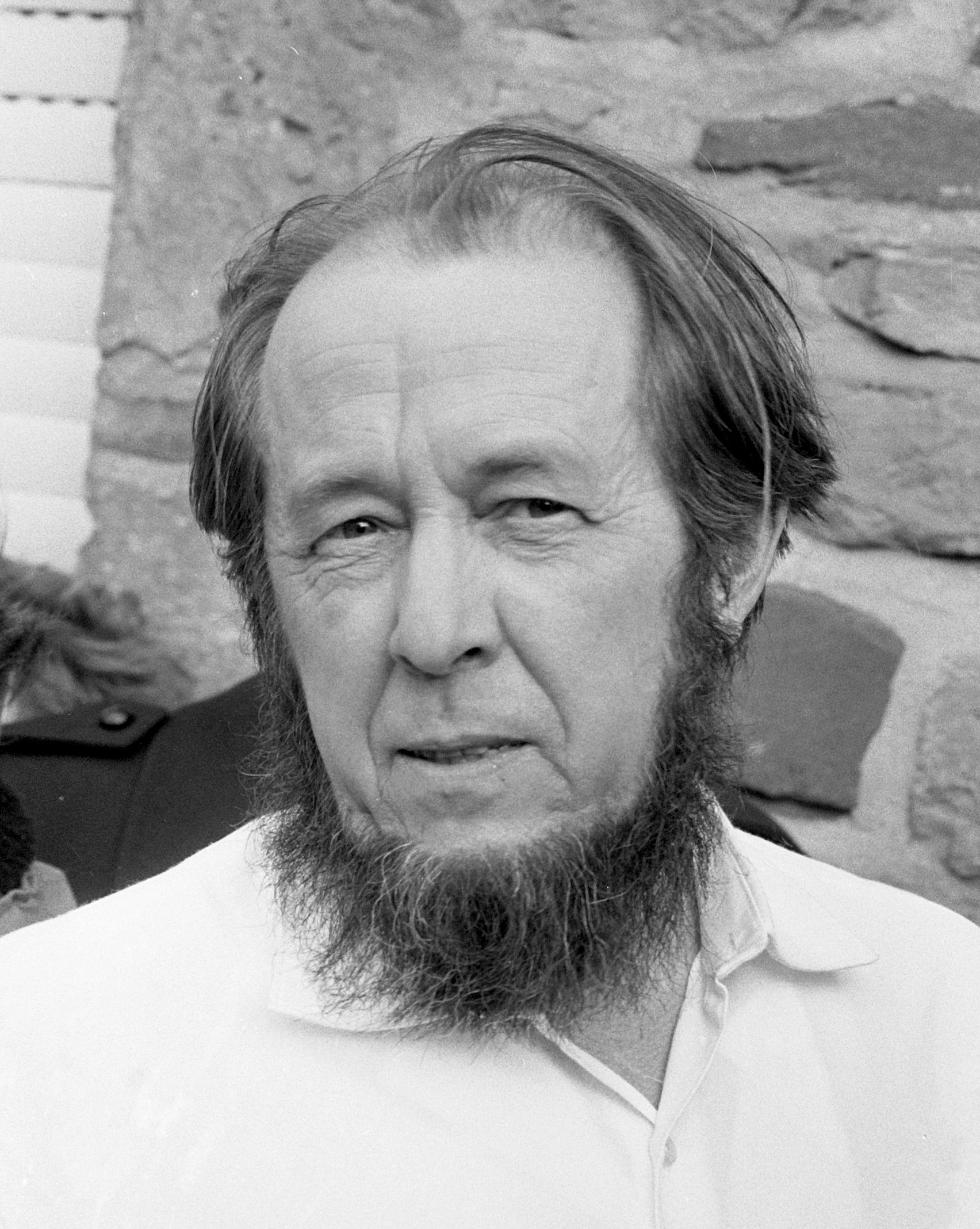

. She referred to the writings of Soviet dissident Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn. (11 December 1918 – 3 August 2008) was a Russian novelist. One of the most famous Soviet dissidents, Solzhenitsyn was an outspoken critic of communism and helped to raise global awareness of political repress ...

who had described the Cold War as the Third World War and noted that in recent years it was a war the West was losing, with more countries turning to socialism. Thatcher referred to contemporary writings by Soviet political writer Konstantin Zarodov and general secretary Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev; uk, links= no, Леонід Ілліч Брежнєв, . (19 December 1906– 10 November 1982) was a Soviet politician who served as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union between 1964 and ...

advocating bringing about a proletarian revolution

A proletarian revolution or proletariat revolution is a social revolution in which the working class attempts to overthrow the bourgeoisie and change the previous political system. Proletarian revolutions are generally advocated by socialis ...

across the world. Thatcher stated that if it did not act, Britain might find itself upon " the scrap heap of history".

Thatcher warned that all NATO members must share the burden of defence, especially as the US had restricted its foreign involvements after their defeat in the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

. She referred to cuts in defence spending of almost £5 billion, announced by Labour, and stated that the Secretary of State for Defence

The secretary of state for defence, also referred to as the defence secretary, is a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, with overall responsibility for the business of the Ministry of Defence. The incumbent is a membe ...

, Roy Mason, should be known instead as the "Secretary for Insecurity". Thatcher stated that "the longer Labour remains in Government, the more vulnerable this country will be", which received applause from the audience. She compared British defence spending, around £90 per head per year, unfavourably with that of West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 O ...

(£130), France (£115), the US (£215) and neutral Sweden (£160). She urged that this be increased, even though "we are poorer than most of our NATO allies. This is part of the disastrous economic legacy of Socialism".

Thatcher noted that Britain's reputation abroad had declined, stating that "as I travel the world, I find people asking again and again, 'What has happened to Britain?' They want to know why we are hiding our heads in the sand, why with all our experience, we are not giving a lead". She warned that the Soviet-backed MPLA

The People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola ( pt, Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola, Abbreviation, abbr. MPLA), for some years called the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola – Labour Party (), is an Angolan left-wi ...

was making rapid gains in Angola

, national_anthem = "Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordina ...

and warned of a domino effect for other countries in Africa if Angola was lost. A loss would also make it difficult to resolve the matter of independent, white-led Rhodesia

Rhodesia (, ), officially from 1970 the Republic of Rhodesia, was an unrecognised state in Southern Africa from 1965 to 1979, equivalent in territory to modern Zimbabwe. Rhodesia was the ''de facto'' Succession of states, successor state to th ...

(which was fighting the Rhodesian Bush War

The Rhodesian Bush War, also called the Second as well as the Zimbabwe War of Liberation, was a civil conflict from July 1964 to December 1979 in the unrecognised country of Rhodesia (later Zimbabwe-Rhodesia).

The conflict pitted three forc ...

against communist-supported black nationalists

Black nationalism is a type of racial nationalism or pan-nationalism which espouses the belief that black people are a race, and which seeks to develop and maintain a black racial and national identity. Black nationalist activism revolves arou ...

) and South African apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

.

Thatcher committed her party to follow a foreign policy closely aligned with the US and called for closer ties with European states and the Commonwealth nations

The Commonwealth of Nations, simply referred to as the Commonwealth, is a political association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire. The chief institutions of the organisation are the C ...

of Australia, New Zealand and Canada. She congratulated Australian prime minister Malcolm Fraser

John Malcolm Fraser (; 21 May 1930 – 20 March 2015) was an Australian politician who served as the 22nd prime minister of Australia from 1975 to 1983, holding office as the leader of the Liberal Party of Australia.

Fraser was raised on hi ...

on his November 1975 election and New Zealand prime minister Robert Muldoon

Sir Robert David Muldoon (; 25 September 19215 August 1992) was a New Zealand politician who served as the 31st Prime Minister of New Zealand, from 1975 to 1984, while leader of the National Party.

Serving as a corporal and sergeant in t ...

on his election in December; both men had beaten socialist opponents. Thatcher called for Britain to provide "a reasoned and vigorous defence of the Western concept of rights and liberties" and referred to recent speeches on this theme by the US ambassador to the UN, Daniel Patrick Moynihan.

Thatcher referred to Britain's position in the European Economic Community (EEC) and called for members to maintain strong national identities

National identity is a person's identity or sense of belonging to one or more states or to one or more nations. It is the sense of "a nation as a cohesive whole, as represented by distinctive traditions, culture, and language". National identity ...

and to resist any move toward closer union. She warned of the threat of a communist victory in the Italian general election, in a "difficult year ahead" (there were concerns at this time over a resurgence in Eurocommunism

Eurocommunism, also referred to as democratic communism or neocommunism, was a trend in the 1970s and 1980s within various Western European communist parties which said they had developed a theory and practice of social transformation more rele ...

and real chances for a communist victory in the Italian election and the Portuguese legislative election). She called for closer cooperation between the police and security services of the EEC and NATO nations and commended the British police for their response to recent terrorist incidents (this included gun and bomb attacks in London as part of the Provisional IRA campaign

From 1969 until 1997,Moloney, p. 472 the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) conducted an armed paramilitary campaign primarily in Northern Ireland and England, aimed at ending British rule in Northern Ireland in order to create a united Ire ...

and the capture of four IRA members in the 1975 Balcombe Street siege

The Balcombe Street siege was an incident involving members of the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) and London's Metropolitan Police lasting from 6 to 12 December 1975. The siege ended with the surrender of the four IRA members and the ...

). At this point Thatcher skipped several pages of her written speech, at the moment she had designated for the purpose in case time was short. The omitted text noted that Britain's economic and military strength had been weakened under Labour's policies and noted that "Soviet military power will not disappear just because we refuse to look at it".

Thatcher concluded her speech by stating that the Conservatives believed Britain was a great country and had the "vital task of shaking the British public out of a long sleep". Her closing sentences were: "There are moments in our history when we have to make a fundamental choice. This is one such moment – a moment when our choice will determine the life or death of our kind of society, – and the future of our children. Let's ensure that our children will have cause to rejoice that we did not forsake their freedom". Part of the speech was broadcast on BBC Radio

BBC Radio is an operational business division and service of the British Broadcasting Corporation (which has operated in the United Kingdom under the terms of a royal charter since 1927). The service provides national radio stations covering ...

at 10 pm that night.

Impact

In his biography of Thatcher, ''Iron Lady'' (2004), John Campbell considers that she made a mistake in stating in her speech that "we are fighting a major internal war against terrorism in Northern Ireland and need more troops in order to win it". British government policy, and the policy adopted by the Conservative Party when they entered government in 1979, was to consider the Northern Ireland situation as a police matter, with the army only deployed (asOperation Banner

Operation Banner was the operational name for the British Armed Forces' operation in Northern Ireland from 1969 to 2007, as part of the Troubles. It was the longest continuous deployment in British military history. The British Army was initial ...

) to assist the civilian authorities. This would be the last time Thatcher would use such terminology concerning the Troubles

The Troubles ( ga, Na Trioblóidí) were an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland that lasted about 30 years from the late 1960s to 1998. Also known internationally as the Northern Ireland conflict, it is sometimes described as an "i ...

, but it may indicate her personal thoughts on the matter. The Soviet ambassador to the United Kingdom, , lodged an official protest about the tone of the speech.

The Soviet press

Printed media in the Soviet Union, i.e., newspapers, magazines and journals, were under strict control of the Communist Party and the Soviet state. The desire to disseminate propaganda is believed to have been the driving force behind the creatio ...

reported on the speech, with Captain Yuri Gavrilov writing an article for the 24 January edition of ''Krasnaya Zvezda

''Krasnaya Zvezda'' (russian: Кра́сная звезда́, literally "Red Star") is the official newspaper of the Soviet and later Russian Ministry of Defence. Today its official designation is "Central Organ of the Russian Ministry of Def ...

'' ("Red Star"), the newspaper of the Soviet ministry of defence

The Ministry of Defense (Minoboron; russian: Министерство обороны СССР) was a government ministry in the Soviet Union. The first Minister of Defense was Nikolai Bulganin, starting 1953. The Krasnaya Zvezda (Red Star) was th ...

. Gavrilov used the headline ("Iron Lady Wields Threats") for the piece and claimed the term "Iron Lady" was used by Thatcher's colleagues, though it is not clear if this is true. Gavrilov may have coined the term and used it to compare Thatcher to Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (, ; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898), born Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, was a conservative German statesman and diplomat. From his origins in the upper class of ...

, the "Iron Chancellor" of imperial Germany

The German Empire (), Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditar ...

. Gavrilov later noted that the speech marked a turning point in the Soviet Union's approach to the United Kingdom; he recalled that before the speech, Soviet cartoons portrayed Britain as a toothless lion, but afterwards they showed more respect for the nation's power. ''Komsomolskaya Pravda

''Komsomolskaya Pravda'' (russian: link=no, Комсомольская правда; lit. "Komsomol Truth") is a daily Russian tabloid newspaper, founded on 13 March 1925.

History and profile

During the Soviet era, ''Komsomolskaya Pravda'' wa ...

'' also reported on the speech and described Thatcher as a "militant ". Soviet news agency TASS

The Russian News Agency TASS (russian: Информацио́нное аге́нтство Росси́и ТАСС, translit=Informatsionnoye agentstvo Rossii, or Information agency of Russia), abbreviated TASS (russian: ТАСС, label=none) ...

also used the "Iron Lady" moniker.

Reuters Russian reporter Robert Evans wrote a story on the Soviet press coverage, including Gavrilov's use of the term "Iron Lady", picked up on by Western media outlets. The British press quickly adopted the term and used it as a descriptor of her tough anti-communist

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when the United States and th ...

stance. Thatcher regarded the nickname with amusement and pride. In a speech to her constituency Conservative Association

A Conservative Association (CA) is a local organisation composed of Conservative Party members in the United Kingdom. Every association varies in membership size but all correspond to a parliamentary constituency in England, Wales, Scotland and N ...

on 6 February, Thatcher adopted the nickname, stating: "Yes I am an iron lady, after all it wasn't a bad thing to be an iron duke, yes if that's how they wish to interpret my defence of values and freedoms fundamental to our way of life".

Thatcher later became prime minister of the United Kingdom after winning a decisive victory in the 1979 general election. She led a right-wing Conservative government that rolled back the extent of the state, implemented largescale privatisations and limited the power of the trade unions

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits (s ...

. She worked closely with the US president from 1981 to 1989, Ronald Reagan, to present an uncompromising stance to the Soviet Union, which remained until the reformist Mikhail Gorbachev became General Secretary of the Communist Party in 1985. Thatcher's pro-NATO stance and support for maintaining an independent nuclear deterrent stood in contrast to Labour's policies during this period. Her premiership also saw the resolution of the Rhodesia question with the formation of an independent Zimbabwe. However, she faced criticism for her refusal to support sanctions on the apartheid regime in South Africa. Thatcher resigned in 1990 after internal party conflicts over her Euroscepticism

Euroscepticism, also spelled as Euroskepticism or EU-scepticism, is a political position involving criticism of the European Union (EU) and European integration. It ranges from those who oppose some EU institutions and policies, and seek refor ...

and the failed implementation of the "poll tax

A poll tax, also known as head tax or capitation, is a tax levied as a fixed sum on every liable individual (typically every adult), without reference to income or resources.

Head taxes were important sources of revenue for many governments f ...

".

References

Works cited

* * * * {{Margaret Thatcher Speeches by Margaret Thatcher Cold War speeches 1976 in British politics January 1976 events in the United Kingdom