Brigham Young on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

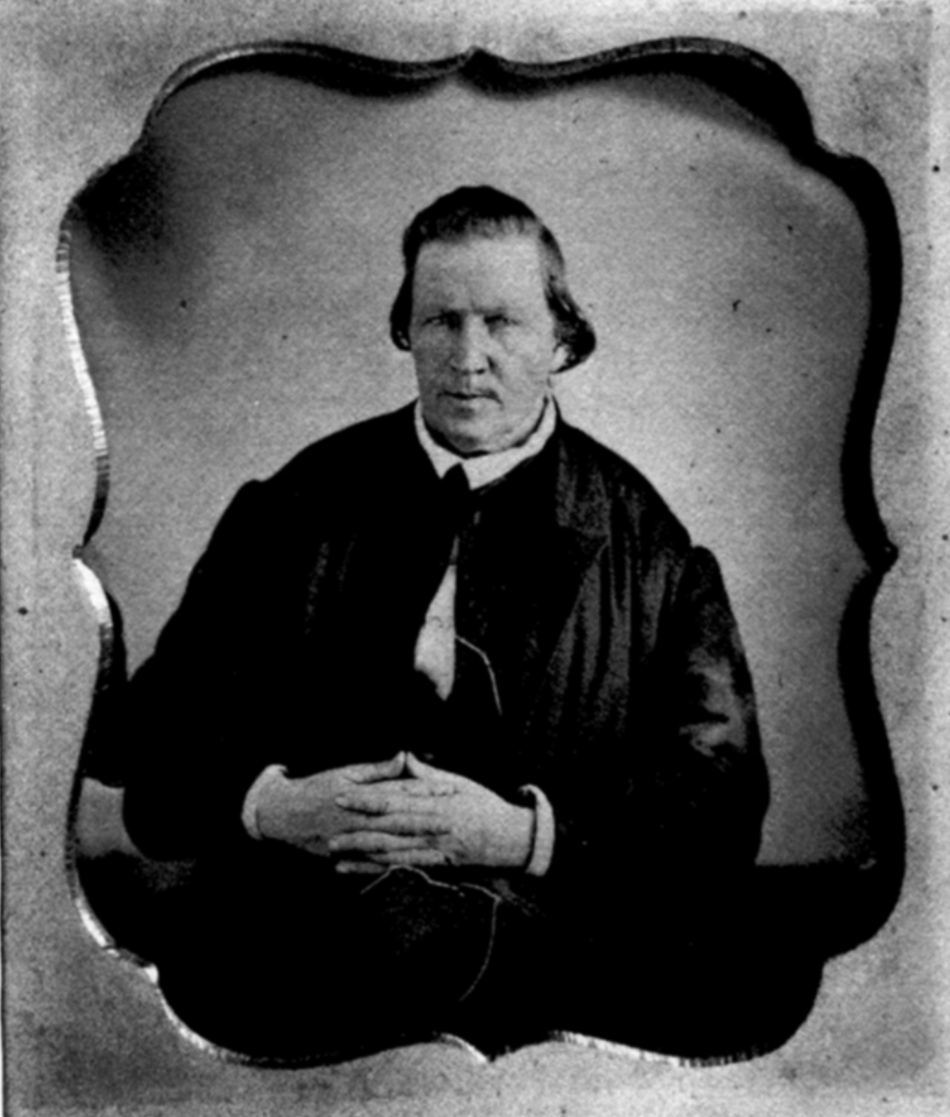

Brigham Young ( ; June 1, 1801August 29, 1877) was an American

Young was born on June 1, 1801, in

Young was born on June 1, 1801, in  Young married Miriam Angeline Works, whom he had met in Port Byron in October 1824. They first resided in a small house adjacent to a pail factory, which was Young's main place of employment at the time. Their daughter, Elizabeth, was born on September 26, 1825. According to William Hayden, Young participated in the Bucksville Forensic and Oratorical Society. Young converted to the Reformed Methodist Church in 1824 after studying the Bible. Upon joining the Methodists, he insisted on being baptized by immersion rather than by their normal practice of sprinkling. In 1828, the family moved briefly to Oswego, New York, on the shore of Lake Ontario, and in 1828 to Mendon, New York. Young's father, two brothers, and sister had already moved to Mendon. In Mendon, Young first became acquainted with Heber C. Kimball, an early member of the LDS Church. Young worked as a carpenter and joiner, and built and operated a saw mill.

Young married Miriam Angeline Works, whom he had met in Port Byron in October 1824. They first resided in a small house adjacent to a pail factory, which was Young's main place of employment at the time. Their daughter, Elizabeth, was born on September 26, 1825. According to William Hayden, Young participated in the Bucksville Forensic and Oratorical Society. Young converted to the Reformed Methodist Church in 1824 after studying the Bible. Upon joining the Methodists, he insisted on being baptized by immersion rather than by their normal practice of sprinkling. In 1828, the family moved briefly to Oswego, New York, on the shore of Lake Ontario, and in 1828 to Mendon, New York. Young's father, two brothers, and sister had already moved to Mendon. In Mendon, Young first became acquainted with Heber C. Kimball, an early member of the LDS Church. Young worked as a carpenter and joiner, and built and operated a saw mill.

By the time Young moved to Mendon in 1828, he had effectively left the Reformed Methodist Church and become a Christian seeker, unconvinced that he had found a church possessing the true authority of

By the time Young moved to Mendon in 1828, he had effectively left the Reformed Methodist Church and become a Christian seeker, unconvinced that he had found a church possessing the true authority of

At a conference on February 14, 1835, Brigham Young was named and ordained a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. On May 4, 1835, Young and other apostles went on a mission to the east coast, specifically in Pennsylvania and New York. His call was to preach to the "remnants of Joseph", a term people in the church used to refer to indigenous people. In August 1835, Young and the rest of the Quorum of the Twelve issued a testimony in support of the divine origin of the Doctrine and Covenants. He oversaw the finishing of the Kirtland temple and spoke in tongues at its dedication in 1836. Shortly afterwards, Young went on another mission with his brother Joseph to New York and New England. On this mission, he visited the family of his aunt, Rhoda Howe Richards. They converted to the church, including his cousin Willard Richards. In August 1837, Young went on another mission to the eastern states. He then returned to Kirtland where he remained until dissenters, unhappy with the failure of the Kirtland Safety Society, forced him to flee the community in December 1837. He then stayed for a short time in Dublin, Indiana, with his brother Lorenzo before moving to Far West, Missouri, in 1838. He was later joined by his family and by other members of the church in Missouri. He became the oldest member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles when David Patten died after the Battle of Crooked River. When Joseph Smith arrived in Far West, he appointed Young, along with Thomas Marsh and David Patten, as "presidency pro tem" in Missouri.

Under Young's direction, the quorum organized the exodus of Latter Day Saints from Missouri to Illinois in 1838. Young also served a year-long mission to the United Kingdom. There, he showed a talent for organizing the church's work and maintaining good relationships with Joseph Smith and the other apostles. Under his leadership, members in the United Kingdom began publishing ''Millennial Star'', a hymnal, and a new edition of the Book of Mormon. Young also served in various leadership and community organization roles among church members in Nauvoo. He joined the Nauvoo city council in 1841 and oversaw the first baptisms for the dead in the unfinished Nauvoo temple. He joined the Masons in Nauvoo on April 7, 1842, and participated in an early endowment ritual led by Joseph Smith that May and became part of the

At a conference on February 14, 1835, Brigham Young was named and ordained a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. On May 4, 1835, Young and other apostles went on a mission to the east coast, specifically in Pennsylvania and New York. His call was to preach to the "remnants of Joseph", a term people in the church used to refer to indigenous people. In August 1835, Young and the rest of the Quorum of the Twelve issued a testimony in support of the divine origin of the Doctrine and Covenants. He oversaw the finishing of the Kirtland temple and spoke in tongues at its dedication in 1836. Shortly afterwards, Young went on another mission with his brother Joseph to New York and New England. On this mission, he visited the family of his aunt, Rhoda Howe Richards. They converted to the church, including his cousin Willard Richards. In August 1837, Young went on another mission to the eastern states. He then returned to Kirtland where he remained until dissenters, unhappy with the failure of the Kirtland Safety Society, forced him to flee the community in December 1837. He then stayed for a short time in Dublin, Indiana, with his brother Lorenzo before moving to Far West, Missouri, in 1838. He was later joined by his family and by other members of the church in Missouri. He became the oldest member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles when David Patten died after the Battle of Crooked River. When Joseph Smith arrived in Far West, he appointed Young, along with Thomas Marsh and David Patten, as "presidency pro tem" in Missouri.

Under Young's direction, the quorum organized the exodus of Latter Day Saints from Missouri to Illinois in 1838. Young also served a year-long mission to the United Kingdom. There, he showed a talent for organizing the church's work and maintaining good relationships with Joseph Smith and the other apostles. Under his leadership, members in the United Kingdom began publishing ''Millennial Star'', a hymnal, and a new edition of the Book of Mormon. Young also served in various leadership and community organization roles among church members in Nauvoo. He joined the Nauvoo city council in 1841 and oversaw the first baptisms for the dead in the unfinished Nauvoo temple. He joined the Masons in Nauvoo on April 7, 1842, and participated in an early endowment ritual led by Joseph Smith that May and became part of the

The Utah Territory was created by Congress as part of the Compromise of 1850. As founder of

The Utah Territory was created by Congress as part of the Compromise of 1850. As founder of

Before his death in Salt Lake City on August 29, 1877, Young suffered from cholera morbus and inflammation of the bowels. It is believed that he died of peritonitis from a ruptured appendix. His last words were "Joseph! Joseph! Joseph!", invoking the name of the late Joseph Smith Jr., founder of the Latter Day Saint movement. On September 2, 1877, Young's funeral was held in the Tabernacle with an estimated 12,000 to 15,000 people in attendance. He is buried on the grounds of the Mormon Pioneer Memorial Monument in the heart of Salt Lake City. A bronze marker was placed at the grave site June 10, 1938, by members of the Young Men and Young Women organizations, which he founded.

Before his death in Salt Lake City on August 29, 1877, Young suffered from cholera morbus and inflammation of the bowels. It is believed that he died of peritonitis from a ruptured appendix. His last words were "Joseph! Joseph! Joseph!", invoking the name of the late Joseph Smith Jr., founder of the Latter Day Saint movement. On September 2, 1877, Young's funeral was held in the Tabernacle with an estimated 12,000 to 15,000 people in attendance. He is buried on the grounds of the Mormon Pioneer Memorial Monument in the heart of Salt Lake City. A bronze marker was placed at the grave site June 10, 1938, by members of the Young Men and Young Women organizations, which he founded.

Of Young's fifty-six wives, twenty-one had never been married before; seventeen were widows; six were divorced; six had living husbands; and the marital status of six others is unknown. Young built the Lion House, the Beehive House, the Gardo House, and the White House in downtown Salt Lake City to accommodate his sizable family. The Beehive House and the Lion House remain as prominent Salt Lake City landmarks. At the north end of the Beehive House was a family store, at which Young's wives and children had running accounts and could buy what they needed. In 1865, Karl Maeser began to privately tutor Young's fifty-six children and stopped when he was called on a mission to Germany in 1867.

At the time of Young's death, nineteen of his wives had predeceased him; he was divorced from ten, and twenty-three survived him. The status of four was unknown. A few of his wives served in administrative positions in the church, such as Zina Huntington and Eliza R. Snow. In his

Of Young's fifty-six wives, twenty-one had never been married before; seventeen were widows; six were divorced; six had living husbands; and the marital status of six others is unknown. Young built the Lion House, the Beehive House, the Gardo House, and the White House in downtown Salt Lake City to accommodate his sizable family. The Beehive House and the Lion House remain as prominent Salt Lake City landmarks. At the north end of the Beehive House was a family store, at which Young's wives and children had running accounts and could buy what they needed. In 1865, Karl Maeser began to privately tutor Young's fifty-six children and stopped when he was called on a mission to Germany in 1867.

At the time of Young's death, nineteen of his wives had predeceased him; he was divorced from ten, and twenty-three survived him. The status of four was unknown. A few of his wives served in administrative positions in the church, such as Zina Huntington and Eliza R. Snow. In his

publication number 35554

*

Brigham Young Letters, MSS SC 890

a

L. Tom Perry Special Collections

Tanner Trust Books

a

University of Utah Digital LibraryMarriott Library Special Collections

{{DEFAULTSORT:Young, Brigham 1801 births 1877 deaths People from Whitingham, Vermont People from Mendon, New York American Freemasons American general authorities (LDS Church) American carpenters American Mormon missionaries in the United Kingdom American people of English descent American proslavery activists Converts to Mormonism from Methodism Governors of Utah Territory American Mormon missionaries in Canada Mormon pioneers Mountain Meadows Massacre Politicians from Salt Lake City People pardoned by James Buchanan Richards–Young family American city founders 19th-century Mormon missionaries Presidents of the Church (LDS Church) Apostles (LDS Church) Presidents of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles (LDS Church) Apostles of the Church of Christ (Latter Day Saints) People of the Utah War Doctrine and Covenants people Deaths from peritonitis Burials at the Mormon Pioneer Memorial Monument Religious leaders from Vermont Latter Day Saints from Utah Latter Day Saints from Vermont Latter Day Saints from Ohio Latter Day Saints from Illinois Latter Day Saints from New York (state) University and college founders Child marriage in the United States Christian miracle workers

religious leader

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

and politician. He was the second president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, informally known as the LDS Church or Mormon Church, is a Nontrinitarianism, nontrinitarian Restorationism, restorationist Christianity, Christian Christian denomination, denomination and the ...

(LDS Church) from 1847 until his death in 1877. He also served as the first governor of the Utah Territory from 1851 until his resignation in 1858.

Young was born in 1801 in Vermont and raised in Upstate New York

Upstate New York is a geographic region of New York (state), New York that lies north and northwest of the New York metropolitan area, New York City metropolitan area of downstate New York. Upstate includes the middle and upper Hudson Valley, ...

. After working as a painter and carpenter, he became a full-time LDS Church leader in 1835. Following a short period of service as a missionary

A missionary is a member of a Religious denomination, religious group who is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Thoma ...

, he moved to Missouri in 1838. Later that year, Missouri governor Lilburn Boggs signed the Mormon Extermination Order, and Young organized the migration of the Latter Day Saints from Missouri to Illinois, where he became an inaugural member of the Council of Fifty. In 1844, while he was traveling to gain support for Joseph Smith's presidential campaign, Smith was killed by a mob, igniting the Illinois Mormon War and triggering a succession crisis in the Latter Day Saint movement. After negotiating a ceasefire, Young was unanimously elected as the church's second president in 1847. During the Mormon exodus, Young led his followers west from Nauvoo, Illinois

Nauvoo ( ; from the ) is a small city in Hancock County, Illinois, United States, on the Mississippi River near Fort Madison, Iowa. The population of Nauvoo was 950 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. Nauvoo attracts visitors for its h ...

, via the Mormon Trail to the Salt Lake Valley

Salt Lake Valley is a valley in Salt Lake County, Utah, Salt Lake County in the north-central portion of the U.S. state of Utah. It contains Salt Lake City, Utah, Salt Lake City and many of its suburbs, notably Murray, Utah, Murray, Sandy, Uta ...

. Once settled in Utah, he ordered the construction of numerous temples, including the Salt Lake Temple

The Salt Lake Temple is a Temple (LDS Church), temple of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints on Temple Square in Salt Lake City, Utah, United States. At , it is the Comparison of temples of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Sa ...

. He also formalized the prohibition of black men attaining priesthood and directed the Mormon Reformation. A supporter of education, Young worked to establish the learning institutions that would later become the University of Utah

The University of Utah (the U, U of U, or simply Utah) is a public university, public research university in Salt Lake City, Utah, United States. It was established in 1850 as the University of Deseret (Book of Mormon), Deseret by the General A ...

and Brigham Young University

Brigham Young University (BYU) is a Private education, private research university in Provo, Utah, United States. It was founded in 1875 by religious leader Brigham Young and is the flagship university of the Church Educational System sponsore ...

.

After arriving in Utah, Young founded Salt Lake City

Salt Lake City, often shortened to Salt Lake or SLC, is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Utah. It is the county seat of Salt Lake County, the most populous county in the state. The city is the core of the Salt Lake Ci ...

and established the State of Deseret

The State of Deseret (modern pronunciation , contemporaneously , as recorded in the Deseret alphabet spelling 𐐔𐐯𐑅𐐨𐑉𐐯𐐻) was a proposed U.S. state, state of the United States promoted by leaders of the Church of Jesus Chri ...

before being appointed Utah's first territorial governor by President Millard Fillmore in 1850. As governor, Young allowed polygamy

Polygamy (from Late Greek , "state of marriage to many spouses") is the practice of marriage, marrying multiple spouses. When a man is married to more than one wife at the same time, it is called polygyny. When a woman is married to more tha ...

, supported slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

and its expansion into Utah, and led the efforts to legalize and regulate slavery in the 1852 Act in Relation to Service, based on his beliefs on slavery. He exerted considerable power over the territory through his theocratic political system, theodemocracy. After President James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was the 15th president of the United States, serving from 1857 to 1861. He also served as the United States Secretary of State, secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and represented Pennsylvan ...

appointed a new governor of the territory, Young declared martial law

Martial law is the replacement of civilian government by military rule and the suspension of civilian legal processes for military powers. Martial law can continue for a specified amount of time, or indefinitely, and standard civil liberties ...

and re-activated the Nauvoo Legion, beginning the Utah War. During the conflict, the Utah Territorial Militia committed a series of attacks that resulted in the mass murder of at least 120 members of the Baker–Fancher immigrant wagon train, known as the Mountain Meadows Massacre. The following month, the Aiken massacre was perpetrated on Young's orders. In 1858, the war ended when Young agreed to resign as governor and allow federal troops to enter the Utah Territory in exchange for a pardon granted to Mormon settlers from President Buchanan.

A polygamist

Polygamy (from Late Greek , "state of marriage to many spouses") is the practice of marriage, marrying multiple spouses. When a man is married to more than one wife at the same time, it is called polygyny. When a woman is married to more tha ...

, Young had 56 wives and 57 children. His teachings are contained in the 19 volumes of transcribed and edited sermons in the '' Journal of Discourses''. His legacy and impact are seen throughout the American West

The Western United States (also called the American West, the Western States, the Far West, the Western territories, and the West) is census regions United States Census Bureau

As American settlement in the U.S. expanded westward, the mea ...

, including numerous memorials, temples, and schools named in his honor. In 2016, Young was estimated to have around 30,000 descendants.

Early life

Young was born on June 1, 1801, in

Young was born on June 1, 1801, in Whitingham, Vermont

Whitingham is a New England town, town in Windham County, Vermont, Windham County, Vermont, United States. The town was named for Nathan Whiting, a landholder. The population was 1,344 at the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census. Whitingham is t ...

. He was the ninth child of John Young and Abigail "Nabby" Howe. Young's father was a farmer, and when Young was three years old his family moved to upstate New York, settling in Chenango County. Young received little formal education, but his mother taught him how to read and write. At age twelve, he moved with his parents to the township of Genoa

Genoa ( ; ; ) is a city in and the capital of the Italian region of Liguria, and the sixth-largest city in Italy. As of 2025, 563,947 people live within the city's administrative limits. While its metropolitan city has 818,651 inhabitan ...

, close to Cayuga Lake. His mother died of tuberculosis in June 1815. Following her death, he moved with his father to Tyrone, New York.

While there, Young's father remarried to a widow named Hannah Brown and sent Young off to learn a trade. Young moved to Auburn, New York

Auburn is a city in Cayuga County, New York, United States. Located at the north end of Owasco Lake, one of the Finger Lakes in Central New York, the city had a population of 26,866 at the 2020 census. It is the largest city of Cayuga County, the ...

, where he was an apprentice to John C. Jeffries. He worked as a carpenter

Carpentry is a skilled trade and a craft in which the primary work performed is the cutting, shaping and installation of building materials during the construction of buildings, ships, timber bridges, concrete formwork, etc. Carpenter ...

, glazier, and painter

Painting is a Visual arts, visual art, which is characterized by the practice of applying paint, pigment, color or other medium to a solid surface (called "matrix" or "Support (art), support"). The medium is commonly applied to the base with ...

. One of the homes that Young helped paint in Auburn belonged to Elijah Miller and later to William Seward, and is now a local museum. With the onset of the Panic of 1819

The Panic of 1819 was the first widespread and durable financial crisis in the United States that slowed westward expansion in the Cotton Belt and was followed by a general collapse of the American economy that persisted through 1821. The Panic ...

, Jeffries dismissed Young from his apprenticeship, and Young moved to Port Byron, which was then called Bucksville. Young reported having a strict Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to rid the Church of England of what they considered to be Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should b ...

-style Christian upbringing. He used tobacco but did not drink alcohol. He refused to sign a temperance pledge, however, stating that "if I sign the temperance pledge I feel that I am bound, and I wish to do just right, without being bound to do it; I want my liberty."

Young married Miriam Angeline Works, whom he had met in Port Byron in October 1824. They first resided in a small house adjacent to a pail factory, which was Young's main place of employment at the time. Their daughter, Elizabeth, was born on September 26, 1825. According to William Hayden, Young participated in the Bucksville Forensic and Oratorical Society. Young converted to the Reformed Methodist Church in 1824 after studying the Bible. Upon joining the Methodists, he insisted on being baptized by immersion rather than by their normal practice of sprinkling. In 1828, the family moved briefly to Oswego, New York, on the shore of Lake Ontario, and in 1828 to Mendon, New York. Young's father, two brothers, and sister had already moved to Mendon. In Mendon, Young first became acquainted with Heber C. Kimball, an early member of the LDS Church. Young worked as a carpenter and joiner, and built and operated a saw mill.

Young married Miriam Angeline Works, whom he had met in Port Byron in October 1824. They first resided in a small house adjacent to a pail factory, which was Young's main place of employment at the time. Their daughter, Elizabeth, was born on September 26, 1825. According to William Hayden, Young participated in the Bucksville Forensic and Oratorical Society. Young converted to the Reformed Methodist Church in 1824 after studying the Bible. Upon joining the Methodists, he insisted on being baptized by immersion rather than by their normal practice of sprinkling. In 1828, the family moved briefly to Oswego, New York, on the shore of Lake Ontario, and in 1828 to Mendon, New York. Young's father, two brothers, and sister had already moved to Mendon. In Mendon, Young first became acquainted with Heber C. Kimball, an early member of the LDS Church. Young worked as a carpenter and joiner, and built and operated a saw mill.

Latter Day Saint conversion

Jesus Christ

Jesus (AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Chris ...

. Sometime in 1830, Young was introduced to the Book of Mormon by way of a copy that his brother, Phineas Howe, had obtained from Samuel H. Smith. Young did not immediately accept the divine claims of the Book of Mormon. In 1831, five missionaries of the Latter Day Saint movement

The Latter Day Saint movement (also called the LDS movement, LDS restorationist movement, or Smith–Rigdon movement) is the collection of independent church groups that trace their origins to a Christian Restorationist movement founded by ...

—Eleazer Miller, Elial Strong, Alpheus Gifford, Enos Curtis, and Daniel Bowen—came from the branch of the church in Columbia, Pennsylvania

Columbia, formerly Wright's Ferry, is a borough (town) in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, United States. As of the 2020 census, it had a population of 10,222. It is southeast of Harrisburg, on the east (left) bank of the Susquehanna River, ...

, to preach in Mendon. A key element of the teachings of this group in Young's eyes was their practicing of spiritual gifts like speaking in tongues

Speaking in tongues, also known as glossolalia, is an activity or practice in which people utter words or speech-like sounds, often thought by believers to be languages unknown to the speaker. One definition used by linguists is the fluid voc ...

and prophecy. This was partly experienced when Young traveled with his wife, Miriam, and Heber C. Kimball to visit the branch of the church in Columbia.

After meeting Joseph Smith

Joseph Smith Jr. (December 23, 1805June 27, 1844) was an American religious and political leader and the founder of Mormonism and the Latter Day Saint movement. Publishing the Book of Mormon at the age of 24, Smith attracted tens of thou ...

, Young joined the Church of Christ in April 9, 1832. He was baptized by Eleazer Miller. Young's siblings and their spouses were baptized that year or the year afterwards. In April 1832, a branch of the church was organized in Mendon; eight of the fifteen families were Youngs. There, Young saw Alpheus Gifford speak in tongues, and in response, Young also spoke in tongues. Young and Kimball spent the summer following their baptism conducting missionary work in western New York, while Vilate Kimball cared for Young's family. After Miriam died of consumption, Vilate continued to care for Brigham's children while he, Heber, and Joseph Young traveled to visit Joseph Smith in Kirtland, Ohio. During the visit, Brigham spoke in a tongue that Smith identified as the " Adamic language".

After visiting Joseph Smith in Kirtland, Brigham set out to preach with his brother Joseph in the winter of 1832–1833. Joseph had been a Reformed Methodist preacher and the two made a similar "preaching circuit" in eastern Canada. They described the Book of Mormon as the "stick of Joseph", mentioned in Ezekiel 37. Young continued to preach in eastern Canada in the spring and accompanied two Canadian converts to Kirtland in July 1833. Young and his two daughters moved to Kirtland along with the Kimball family later that summer. Here he became acquainted with Mary Ann Angell, a convert to the faith from Rhode Island

Rhode Island ( ) is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Connecticut to its west; Massachusetts to its north and east; and the Atlantic Ocean to its south via Rhode Island Sound and Block Is ...

, and the two were married in February 1834 and obtained a marriage certificate on March 31, 1834.

In May 1834, Young became a member of Zion's Camp and traveled to Missouri. He returned to Kirtland with members of the camp in August. After his return to Kirtland, Young did carpentry, painting, and glazing work to earn money. He also worked on the Kirtland Temple and went to a grammar school. His third child and first son, Joseph A. Young, was born shortly after his return. Mary Ann, who was pregnant at the time, had provided for Young's two daughters and the children of her brother Solomon Angell and their friend Lorenzo Booth while Young was away with Zion's Camp.

LDS Church service

Anointed Quorum The Anointed Quorum, also known as the Quorum of the Anointed, or the Holy Order, was a select body of men and women who Joseph Smith initiated into Mormon Temple (Latter Day Saints), temple Ordinance (Latter Day Saints), ordinances at Nauvoo, Illin ...

. Young and the other apostles directed the church's missionary work and the immigration of new converts from this point forward. Young served another mission to the Eastern seaboard.

During his time in Nauvoo, Joseph Smith introduced the doctrine of plural marriage among church leaders. Young performed the sealing ordinances for two of Joseph Smith's plural wives in early 1842. Young proposed marriage to Martha Brotherton, who was seventeen years old at the time and had recently immigrated from Manchester, England. Brotherton signed an affidavit saying that she had been pressured by Young and then Smith to accept polygamy. The affidavit was created at John C. Bennett's request, after his excommunication and in conjunction with his distribution of false information combined with true information about the church's practice of polygamy. Brigham Young and William Smith discredited Brotherton's character, and Brotherton herself did not associate with the church afterwards. Young campaigned against Bennett's allegations that Joseph Smith practiced "spiritual wifery"; Young knew of Smith's hidden practice of polygamy. He also helped to convince Hyrum to accept polygamy.

Young married Lucy Ann Decker in June 1842, making her his first plural wife. Young knew her father, Isaac Decker, in New York. Lucy was still married to William Seeley when Young married her. Young supported her and her two children while they lived in their own home in Nauvoo. Lucy and Young had seven children together. Young was one of the first men in Nauvoo to practice polygamy, and he married more women than any other polygamist while in Nauvoo. While in Nauvoo, he married Clarissa Decker, Clarissa Ross, Emily Dow Partidge, Louisa Beaman, Margaret Maria Alley, Emmeline Free, Margaret Piece, and Zina Diantha Huntington. These wives bore him children after they moved to Utah. He also married in Nauvoo, but did not have children with Augusta Adams Cobb, Susannah Snively, Eliza Bowker, Ellen A. Rockwood, and Namah K. J. Carter. Eight of Young's plural marriages in Nauvoo were to Joseph Smith's widows.

Young traveled east with Wilford Woodruff and George A. Smith from July to October 1843 on a mission to raise funds for the Nauvoo temple and its guesthouse. Young's six-year-old daughter Mary Ann died while he was on this mission. On November 22, 1843, Young and his wife Mary Ann received the second anointing, a ritual that assured them that their salvation and exaltation would occur. In March 1844, Brigham Young was an inaugural member of the Council of Fifty, which later organized the Mormon exodus from Nauvoo.

In 1844, Young traveled east again to solicit votes for Joseph Smith in his presidential campaign. In June 1844, while Young was away, Joseph Smith was killed by an armed mob who stormed the jail where he was awaiting trial for the charge of treason. Young did not learn of the assassination until early July. Several claimants to fill the leadership vacuum emerged during the succession crisis that ensued. Church members gathered at a meeting on August 8, 1844, with the intent to choose between two claimants, Young and Sidney Rigdon, the senior surviving member of the church's First Presidency. At the meeting, Rigdon argued no one could succeed Smith and that he (Rigdon) should become Smith's "spokesman" and guardian of the church. Young argued that the church needed more than a spokesman and that the twelve apostles, not Rigdon, had "the fullness of the priesthood" necessary to succeed Smith's leadership. Young claimed access to revelation to know God's choice of successor because of his position as an apostle. The majority of attendants voted that the Quorum of the Twelve was to lead the church. Many of Young's followers stated in reminiscent accounts (the earliest in 1850 and the latest in 1920) that when Young spoke to the congregation, he miraculously looked or sounded exactly like Smith, which they attributed to the power of God. Young began acting as the church's president afterwards, though he did not yet have a full presidency. He also led the Anointed Quorum. Young led the church as president of the Quorum of the Twelve until December 5, 1847, when the quorum unanimously agreed to organize a new First Presidency with Young as president of the church. A church conference held in Iowa sustained Young and his First Presidency on December 27, 1847.

Not all church members followed Young. Rigdon became the president of a separate church organization based in Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, United States, and its county seat. It is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, second-most populous city in Pennsylvania (after Philadelphia) and the List of Un ...

, Pennsylvania, and several other potential successors emerged to lead what became other denominations of the movement.

Before departing Nauvoo, Young focused on completing the Nauvoo temple. After the exterior was completed on December 10, 1845, members received their temple endowments day and night, and Young officiated many of these sessions. An estimated 5,000 members were endowed between December 10, 1845, and February 1846. With the repealing of Nauvoo's charter in January 1845, church members in Nauvoo lost their courts, police, and militia, leaving them vulnerable to attacks by mobs. Young instructed victims of anti-Mormon violence on the outskirts of Nauvoo to move to Nauvoo. Young negotiated with Stephen A. Douglas and agreed to lead church members out of Nauvoo in the spring in exchange for peace. Some Mormons counterfeited American and Mexican money, and a grand jury indicted Young and other church leaders in 1845. When officers arrived at the Nauvoo temple to arrest Young, he sent William Miller out in Young's hat and cloak. Miller was arrested but released when it was discovered he was not Brigham Young. Young himself condemned the counterfeiting. John Turner's biography states: "it remains unclear whether Young ..had sanctioned the bogus-making operation". The indictment of Young and other leaders, combined with rumors that troops would prevent the Mormons from leaving, led Young to start their exodus in February 1846.

Migration west

Repeated conflict in Nauvoo led Young to relocate his group of Latter-day Saints to theSalt Lake Valley

Salt Lake Valley is a valley in Salt Lake County, Utah, Salt Lake County in the north-central portion of the U.S. state of Utah. It contains Salt Lake City, Utah, Salt Lake City and many of its suburbs, notably Murray, Utah, Murray, Sandy, Uta ...

, which was then part of Mexico. Young organized the journey that would take the Mormon pioneers

The Mormon pioneers were members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), also known as Latter-day Saints, who Human migration, migrated beginning in the mid-1840s until the late-1860s across the United States from the ...

to Winter Quarters, Nebraska, in 1846, before continuing on to the Salt Lake Valley. By the time Young arrived at the final destination, it had come under American control as a result of war with Mexico, although U.S. sovereignty would not be confirmed until 1848. Young arrived in the Salt Lake Valley on July 24, 1847, a date now recognized as Pioneer Day in Utah. Two days after their arrival, Young and the Twelve Apostles climbed the peak just north of the city and raised the American flag, calling it the "Ensign of Liberty".

Among Young's first acts upon arriving in the valley were the naming of the city as "The City of the Great Salt Lake" and its organization into blocks of ten acres, each divided into eight equal-sized lots. On August 7, Young suggested that the members of the camp be re-baptized to signify a re-dedication to their beliefs and covenants. Young spent just over a month in the Valley recovering from mountain fever before returning to Winter Quarters on August 31. Young's expedition was one of the largest and one of the best organized westward treks, and he made various trips back and forth between the Salt Lake Valley and Winter Quarters to assist other companies in their journeys.

After three years of leading the church as the President of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, Young reorganized a new First Presidency and was sustained as the second president of the church on December 27, 1847, at Winter Quarters. Young named Heber C. Kimball as his first counselor and Willard Richards as his second. Young and his counselors were again sustained unanimously by church members at a church conference in Salt Lake City in September 1850.

Governor of Utah Territory

The Utah Territory was created by Congress as part of the Compromise of 1850. As founder of

The Utah Territory was created by Congress as part of the Compromise of 1850. As founder of Salt Lake City

Salt Lake City, often shortened to Salt Lake or SLC, is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Utah. It is the county seat of Salt Lake County, the most populous county in the state. The city is the core of the Salt Lake Ci ...

, Young was appointed the territory's first governor and superintendent of American Indian affairs by President Millard Fillmore on February 3, 1851. He was sworn in by Justice Daniel H. Wells for a salary of $1,500 a year and named as superintendent of Indian Affairs for an additional $1,000. During his time as governor, Young directed the establishment of settlements throughout present-day Utah, Idaho, Arizona, Nevada, California, and parts of southern Colorado and northern Mexico. Under his direction, the Mormons built roads, bridges, forts, and irrigation projects; established public welfare; organized a militia; issued a "selective extermination" order against male Timpanogos; and after a series of wars, eventually made peace with the Native Americans. Young was also one of the first to subscribe to Union Pacific

The Union Pacific Railroad is a Class I freight-hauling railroad that operates 8,300 locomotives over routes in 23 U.S. states west of Chicago and New Orleans. Union Pacific is the second largest railroad in the United States after BNSF, ...

stock, for the construction of the First transcontinental railroad

America's first transcontinental railroad (known originally as the "Pacific Railroad" and later as the "Overland Route (Union Pacific Railroad), Overland Route") was a continuous railroad line built between 1863 and 1869 that connected the exis ...

. He also authorized the construction of the Utah Central railroad line, which connected Salt Lake City to the Union Pacific transcontinental railroad. Young organized the first Utah Territorial Legislature and established Fillmore as the territory's first capital.

Young established a gold mint in 1849 and called for the minting of coins using gold dust that had been accumulated from travelers during the Gold Rush. The mint was closed in 1861 by Alfred Cumming, gubernatorial successor to Young. Young also organized a board of regents to establish a university in the Salt Lake Valley. It was established on February 28, 1850, as the University of Deseret; its name was eventually changed to the University of Utah

The University of Utah (the U, U of U, or simply Utah) is a public university, public research university in Salt Lake City, Utah, United States. It was established in 1850 as the University of Deseret (Book of Mormon), Deseret by the General A ...

. In 1849, Young arranged for a printing press to be brought to the Salt Lake Valley, which was later used to print the ''Deseret News

The ''Deseret News'' () is a multi-platform newspaper based in Salt Lake City, published by Deseret News Publishing Company, a subsidiary of Deseret Management Corporation, which is owned by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS ...

'' periodical.

In 1851, Young and several federal officials—including territorial Secretary Broughton Harris—became unable to work cooperatively. Within months, Harris and the others departed their Utah appointments without replacements being named, and their posts remained unfilled for the next two years. These individuals later became known as the Runaway Officials of 1851.

Young supported slavery and its expansion into Utah and led the efforts to legalize and regulate slavery in the 1852 Act in Relation to Service, based on his beliefs on slavery. Young said in an 1852 speech, "In as much as we believe in the Bible... we must believe in slavery. This colored race have been subjected to severe curses... which they have brought upon themselves." Seven years later in 1859, Young stated in an interview with the ''New York Tribune'' that he considered slavery a "divine institution... not to be abolished".

In 1856, Young organized an efficient mail service known as the Brigham Young Express and Carrying Company, which transported mail and passengers between Missouri and California. In 1858, following the events of the Utah War and Mountain Meadows Massacre, he stepped down to his gubernatorial successor, Alfred Cumming.

LDS Church president

Young served for 29 years as the LDS Church president and is the longest-serving in that role.Educational endeavors

During time as prophet and governor, Young encouraged bishops to establish grade schools for their congregations, which would be supported by volunteer work and tithing payments. Young viewed education as a process of learning how to make the Kingdom of God a reality on earth, and at the core of his "philosophy of education" was the belief that the church had within itself all that was necessary to save mankind materially, spiritually, and intellectually. On October 16, 1875, Young deeded buildings and land inProvo, Utah

Provo ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Utah County, Utah, United States. It is south of Salt Lake City along the Wasatch Front, and lies between the cities of Orem, Utah, Orem to the north and Springville, Utah, Springville to the south ...

, to a board of trustees for establishing an institution of learning, ostensibly as part of the University of Deseret. Young said, "I hope to see an Academy established in Provo ... at which the children of the Latter-day Saints can receive a good education unmixed with the pernicious atheistic influences that are found in so many of the higher schools of the country." The school broke off from the University of Deseret and became Brigham Young Academy in 1876 under the leadership of Karl G. Maeser, and was the precursor to Brigham Young University

Brigham Young University (BYU) is a Private education, private research university in Provo, Utah, United States. It was founded in 1875 by religious leader Brigham Young and is the flagship university of the Church Educational System sponsore ...

.

Within the church, Young reorganized the Relief Society for women in 1867 and created organizations for young women in 1869 and young men in 1875. The Young Women organization was first called the Retrenchment Association and was intended to promote the turning of young girls away from the costly and extravagant ways of the world. It later became known as the Young Ladies Mutual Improvement Association and was a charter member of the National Council of Women and International Council of Women.

Young also organized a committee to refine the Deseret alphabet

The Deseret alphabet (; Deseret: or ) is a phoneme, phonemic English-language spelling reform developed between 1847 and 1854 by the board of regents of the University of Deseret under the leadership of Brigham Young, the second President of t ...

—a phonetic alphabet that had been developed sometime between 1847 and 1854. At its prime, the alphabet was used in two ''Deseret News'' articles, two elementary readers, and in a translation of the Book of Mormon. By 1870, it had all but disappeared from use.

Temple building

Young was involved intemple

A temple (from the Latin ) is a place of worship, a building used for spiritual rituals and activities such as prayer and sacrifice. By convention, the specially built places of worship of some religions are commonly called "temples" in Engli ...

building throughout his membership in the LDS Church, making it a priority during his time as church president. Under Smith's leadership, Young participated in the building of the Kirtland and Nauvoo temples. Just four days after arriving in the Salt Lake Valley, Young designated the location for the Salt Lake Temple

The Salt Lake Temple is a Temple (LDS Church), temple of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints on Temple Square in Salt Lake City, Utah, United States. At , it is the Comparison of temples of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Sa ...

; he presided over its groundbreaking years later on April 6, 1853. During his tenure, Young oversaw construction of the Salt Lake Tabernacle and announced plans to build the St. George (1871), Manti (1875), and Logan (1877) temples. He also provisioned the building of the Endowment House

The Endowment House was an early building used by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) to administer Temple (LDS Church), temple Ordinance (Latter Day Saints), ordinances in Salt Lake City, Utah Territory. From the construc ...

, a "temporary temple", which began to be used in 1855 to provide temple ordinances to church members while the Salt Lake Temple was under construction.

Teachings

The majority of Young's teachings are contained in the 19 volumes of transcribed and edited sermons in the '' Journal of Discourses''. The LDS Church's Doctrine and Covenants contains one section from Young that has been canonized as scripture, added in 1876.Polygamy

Thoughpolygamy

Polygamy (from Late Greek , "state of marriage to many spouses") is the practice of marriage, marrying multiple spouses. When a man is married to more than one wife at the same time, it is called polygyny. When a woman is married to more tha ...

was practiced by Young's predecessor, Joseph Smith, the practice is often associated with Young. Some Latter Day Saint denominations, such as the Community of Christ, consider Young the "Father of Mormon Polygamy". In 1853, Young made the church's first official statement on the subject since the church had arrived in Utah. Young acknowledged that the doctrine was challenging for many women, but stated its necessity for creating large families, proclaiming: "But the first wife will say, 'It is hard, for I have lived with my husband twenty years, or thirty, and have raised a family of children for him, and it is a great trial to me for him to have more women;' then I say it is time that you gave him up to other women who will bear children." Young believed that sexual desire was given by God to ensure the perpetuation of humankind and believed sex should be confined to marriage.

Adam-God doctrine and blood atonement

One of the more controversial teachings of Young during the Mormon Reformation was the Adam–God doctrine. According to Young, he was taught by Smith thatAdam

Adam is the name given in Genesis 1–5 to the first human. Adam is the first human-being aware of God, and features as such in various belief systems (including Judaism, Christianity, Gnosticism and Islam).

According to Christianity, Adam ...

is "our Father and our God, and the only God with whom we have to do". According to the doctrine, Adam was once a mortal man who became resurrected and exalted. From another planet, Adam brought Eve

Eve is a figure in the Book of Genesis in the Hebrew Bible. According to the origin story, "Creation myths are symbolic stories describing how the universe and its inhabitants came to be. Creation myths develop through oral traditions and there ...

, one of his wives, with him to the earth, where they became mortal by eating the fruit of the tree of knowledge of good and evil. After bearing mortal children and establishing the human race, Adam and Eve returned to their heavenly thrones where Adam acts as the god of this world. Later, as Young is generally understood to have taught, Adam returned to the earth to become the biological father of Jesus. The LDS Church has since repudiated the Adam–God doctrine.

Young also taught the doctrine of blood atonement, in which the atonement of Jesus

Jesus (AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Chris ...

cannot redeem an eternal sin, which included apostasy

Apostasy (; ) is the formal religious disaffiliation, disaffiliation from, abandonment of, or renunciation of a religion by a person. It can also be defined within the broader context of embracing an opinion that is contrary to one's previous re ...

, theft, fornication

Fornication generally refers to consensual sexual intercourse between two people who are not married to each other. When a married person has consensual sexual relations with one or more partners whom they are not married to, it is called adu ...

(but not sodomy

Sodomy (), also called buggery in British English, principally refers to either anal sex (but occasionally also oral sex) between people, or any Human sexual activity, sexual activity between a human and another animal (Zoophilia, bestiality). I ...

), or adultery. Instead, those who committed such sins could partially atone for their sin by sacrificing their life in a way that sheds blood. The LDS Church has formally repudiated the doctrine as early as 1889 and multiple times since the days of Young.

Race restrictions on temples, priesthood, and interracial marriage

Young is generally considered to have instituted a church ban against conferring the priesthood on men of black African descent, who had generally been treated equally to white men in this respect under Smith's presidency. After settling in Utah in 1848, Young announced the ban, which also forbade blacks from participating in Mormon temple rites such as the endowment or sealings. On many occasions, Young taught that blacks were denied the priesthood because they were "the seed of Cain". In 1863, Young stated: "Shall I tell you the law of God in regard to the African race? If the white man who belongs to the chosen seed mixes his blood with the seed of Cain, the penalty, under the law of God, is death on the spot. This will always be so." Young was also a vocal opponent of theories of human polygenesis, being a firm voice for stating that all humans were the product of one creation. Throughout his time as prophet, Young went to great lengths to deny the assumption that he was the author of the practice of priesthood denial to black men, asserting instead that the Lord was. According to Young, the matter was beyond his personal control and was divinely determined rather than historically or personally as many assumed. Young taught that the day would come when black men would again have the priesthood, saying that after "all the other children of Adam have the privilege of receiving the Priesthood, and of coming into the kingdom of God, and of being redeemed from the four-quarters of the earth, and have received their resurrection from the dead, then it will be time enough to remove the curse from Cain and his posterity." These racial restrictions remained in place until 1978, when the policy was rescinded by church president Spencer W. Kimball, and the church subsequently "disavow dtheories advanced in the past" to explain this ban, essentially attributing the origins of the ban solely to Young.Mormon Reformation

During 1856 and 1857, a period of renewed emphasis on spirituality within the church known as the Mormon Reformation took place under Young's direction. The Mormon Reformation called for a spiritual reawakening among members of the church and took place largely in the Utah Territory. Jedediah M. Grant, one of the key figures of the Reformation and one of Young's counselors, traveled throughout the Territory, preaching to Latter-day Saint communities and settlements with the goal of inspiring them to reject sin and turn towards spiritual things. As part of the Reformation, almost all "active" or involved LDS Church members were rebaptized as a symbol of their commitment. At a church meeting on September 21, 1856, Brigham Young stated: "We need a reformation in the midst of this people; we need a thorough reform." Large gatherings and meetings during this period were conducted by Young and Grant, and Young played a key role in the circulation of the Mormon Reformation with his emphasis onplural marriage

Polygamy (called plural marriage by Latter-day Saints in the 19th century or the Principle by modern fundamentalist practitioners of polygamy) was practiced by leaders of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) for more ...

, rebaptism, and passionate preaching and oration. It was during this period that the controversial doctrine of blood atonement was occasionally preached by Young, though it was repudiated in 1889 and never practiced by members of the church. The Reformation appeared to have ended completely by early 1858.

Conflicts

Shortly after the arrival of Young's pioneers, the new Latter-day Saint colonies were incorporated into the United States through theMexican Cession

The Mexican Cession () is the region in the modern-day Western United States that Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United S ...

. Young petitioned the U.S. Congress to create the State of Deseret

The State of Deseret (modern pronunciation , contemporaneously , as recorded in the Deseret alphabet spelling 𐐔𐐯𐑅𐐨𐑉𐐯𐐻) was a proposed U.S. state, state of the United States promoted by leaders of the Church of Jesus Chri ...

. The Compromise of 1850 instead carved out Utah Territory, and Young was appointed governor. As governor and church president, Young directed both religious and economic matters. He encouraged independence and self-sufficiency. Many cities and towns in Utah, and some in neighboring states, were founded under Young's direction. Young's leadership style has been viewed as autocratic.

Utah War

When federal officials received reports of widespread and systematic obstruction of federal officials in Utah (most notably judges), U.S. PresidentJames Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was the 15th president of the United States, serving from 1857 to 1861. He also served as the United States Secretary of State, secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and represented Pennsylvan ...

decided in early 1857 to install a non-Mormon governor. Buchanan accepted the reports of the Runaway Officials without any further investigation, and the new non-sectarian governor was appointed and sent to the new territory accompanied by 2,500 soldiers. When Young received word in July that federal troops were headed to Utah with his replacement, he called out his militia to ambush the federal force using delaying tactics. During the defense of Utah, now called the Utah War, Young held the U.S. Army at bay for a winter by taking their cattle and burning supply wagons. Young eventually reached a settlement with the aid of a peace commission and agreed to step down as governor. Buchanan later pardon

A pardon is a government decision to allow a person to be relieved of some or all of the legal consequences resulting from a criminal conviction. A pardon may be granted before or after conviction for the crime, depending on the laws of the j ...

ed Young.

Mountain Meadows Massacre

The degree of Young's involvement in the Mountain Meadows Massacre, which took place in Washington County in 1857, is disputed. Leonard J. Arrington reports that Young received a rider at his office on the day of the massacre, and that when he learned of the contemplated attack by members of the church in Parowan and Cedar City, he sent back a letter directing that the Fancher party be allowed to pass through the territory unmolested. Young's letter reportedly arrived on September 13, 1857, two days after the massacre. As governor, Young had promised the federal government he would protect migrants passing through Utah Territory, but over 120 men, women, and children were killed in this incident. There is no debate concerning the involvement of individual Mormons from the surrounding communities by scholars. Only children under the age of seven, who were cared for by local Mormon families, survived, and the murdered members of the wagon train were left unburied. The remains of about 40 people were later found and buried, and U.S. Army officer James Henry Carleton had a large cross made from local trees, the transverse beam bearing the engraving, "Vengeance Is Mine, Saith The Lord: I Will Repay" and erected acairn

A cairn is a human-made pile (or stack) of stones raised for a purpose, usually as a marker or as a burial mound. The word ''cairn'' comes from the (plural ).

Cairns have been and are used for a broad variety of purposes. In prehistory, t ...

of rocks at the site. A large slab of granite was put up on which he had the following words engraved: "Here 120 men, women and children were massacred in cold blood early in September, 1857. They were from Arkansas." For two years, the monument stood as a memorial to those traveling the Spanish Trail through Mountain Meadow. According to Wilford Woodruff, Young brought an entourage to Mountain Meadows in 1861 and suggested that the monument instead read "Vengeance is mine and I have taken a little".

Death

Before his death in Salt Lake City on August 29, 1877, Young suffered from cholera morbus and inflammation of the bowels. It is believed that he died of peritonitis from a ruptured appendix. His last words were "Joseph! Joseph! Joseph!", invoking the name of the late Joseph Smith Jr., founder of the Latter Day Saint movement. On September 2, 1877, Young's funeral was held in the Tabernacle with an estimated 12,000 to 15,000 people in attendance. He is buried on the grounds of the Mormon Pioneer Memorial Monument in the heart of Salt Lake City. A bronze marker was placed at the grave site June 10, 1938, by members of the Young Men and Young Women organizations, which he founded.

Before his death in Salt Lake City on August 29, 1877, Young suffered from cholera morbus and inflammation of the bowels. It is believed that he died of peritonitis from a ruptured appendix. His last words were "Joseph! Joseph! Joseph!", invoking the name of the late Joseph Smith Jr., founder of the Latter Day Saint movement. On September 2, 1877, Young's funeral was held in the Tabernacle with an estimated 12,000 to 15,000 people in attendance. He is buried on the grounds of the Mormon Pioneer Memorial Monument in the heart of Salt Lake City. A bronze marker was placed at the grave site June 10, 1938, by members of the Young Men and Young Women organizations, which he founded.

Business ventures and wealth

Young engaged in a vast assortment of commercial ventures by himself and in partnership with others. These included a wagon express company, a ferryboat company, a railroad, and the manufacturing of processed lumber, wool, sugar beets, iron, and liquor. Young achieved greatest success in real estate. He also tried to promote Mormon self-sufficiency by establishing collectivist communities, known as the United Order of Enoch. Young was also involved in the organization of the Salt Lake Gas Works, the Salt Lake Water Works, an insurance company, a bank, and the ZCMI store in downtown Salt Lake City. In 1873, he announced that he would step down as president of the Deseret National Bank and of ZCMI, as well as from his role as trustee-in-trust for the church. He cited as his reason for this that he was ready to relieve himself from the burden of "secular affairs". At the time of his death, Young was the wealthiest man in Utah, with an estimated personal fortune of $600,000 ().Legacy

Impact

Young had many nicknames during his lifetime, among the most popular being "AmericanMoses

In Abrahamic religions, Moses was the Hebrews, Hebrew prophet who led the Israelites out of slavery in the The Exodus, Exodus from ancient Egypt, Egypt. He is considered the most important Prophets in Judaism, prophet in Judaism and Samaritani ...

" (alternatively, "Modern Moses" or "Mormon Moses"), because, like the biblical

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) biblical languages ...

figure, Young led his followers, the Mormon pioneers, in an exodus through a desert, to what they saw as a promised land.

He credited Young's leadership with helping to settle much of the American West:

Memorials to Young include a bronze statue in front of the Abraham O. Smoot Administration Building, Brigham Young University; a marble statue in the National Statuary Hall Collection

The National Statuary Hall Collection in the United States Capitol is composed of statues donated by individual states to honor persons notable in their history. Limited to two statues per state, the collection was originally set up in the old Hal ...

at the United States Capitol

The United States Capitol, often called the Capitol or the Capitol Building, is the Seat of government, seat of the United States Congress, the United States Congress, legislative branch of the Federal government of the United States, federal g ...

, donated by the State of Utah in 1950; and a statue atop the '' This is the Place Monument'' in Salt Lake City.

Views of race and slavery

Young believed in the racial superiority of white men. His manuscript history from January 5, 1852, which was published in the ''Deseret News

The ''Deseret News'' () is a multi-platform newspaper based in Salt Lake City, published by Deseret News Publishing Company, a subsidiary of Deseret Management Corporation, which is owned by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS ...

'', reads:The negro … should serve the seed of Abraham; he should not be a ruler, nor vote for men to rule over me nor my brethren. The Constitution of Deseret is silent upon this, we meant it should be so. The seed of Canaan cannot hold any office, civil or ecclesiastical. … The decree of God that Canaan should be a servant of servants unto his brethren (i.e., Shem and Japhet ic is in full force. The day will come when the seed of Canaan will be redeemed and have all the blessings their brethren enjoy. Any person that mingles his seed with the seed of Canaan forfeits the right to rule and all the blessings of the Priesthood of God; and unless his blood were spilled and that of his offspring he nor they could not be saved until the posterity of Canaan are redeemed.'Young adopted the idea of the Curse of Ham—a racist interpretation of Genesis 9 which white proponents of slavery in antebellum America used to justify enslaving black people of African descent—and applied it liberally and literally. On this topic, Young wrote: "They have not wisdom to act like white men." Young also predicted a future in which Chinese and Japanese people would immigrate to America. He averred that Chinese and Japanese immigrants would need to be governed by white men as they would have no understanding of government. Young had a somewhat mixed view of slavery which historian John G. Turner called a "bundle of contradictions". In the 1840s, Young strove to keep aloof from nationwide political debates over slavery, avoiding committing to either antislavery or proslavery positions. In the early 1850s, he expressed some support for the antislavery "free soil" position in American politics, and in January 1852, he declared in a speech that "no property can or should be recognized as existing in slaves", suggesting opposition to the existence of slavery. However, two weeks later Young declared himself a "firm believer in slavery".

Family and descendants

Young was a polygamist, having at least fifty-six wives. The policy and practice of polygamy was difficult for many in the church to accept. Young stated that upon being taught about plural marriage by Joseph Smith: "It was the first time in my life that I desired the grave." By the time of his death, Young had fifty-seven children by sixteen of his wives; forty-six of his children reached adulthood. Sources have varied on the number of Young's wives, as well as their ages. This is due to differences in what scholars have considered to be a "wife". There were fifty-six women who Young was sealed to during his lifetime. While the majority of the sealings were "for eternity", some were "for time only", meaning that Young was sealed to these women as a proxy for their previous husbands who had died. Researchers state that not all of the fifty-six marriages were conjugal. Young did not live with a number of his wives or publicly hold them out as wives, which has led to confusion on the number and their identities. Thirty-one of his wives were not connubial and had exchanged eternity-only vows with him. Of Young's fifty-six wives, twenty-one had never been married before; seventeen were widows; six were divorced; six had living husbands; and the marital status of six others is unknown. Young built the Lion House, the Beehive House, the Gardo House, and the White House in downtown Salt Lake City to accommodate his sizable family. The Beehive House and the Lion House remain as prominent Salt Lake City landmarks. At the north end of the Beehive House was a family store, at which Young's wives and children had running accounts and could buy what they needed. In 1865, Karl Maeser began to privately tutor Young's fifty-six children and stopped when he was called on a mission to Germany in 1867.

At the time of Young's death, nineteen of his wives had predeceased him; he was divorced from ten, and twenty-three survived him. The status of four was unknown. A few of his wives served in administrative positions in the church, such as Zina Huntington and Eliza R. Snow. In his

Of Young's fifty-six wives, twenty-one had never been married before; seventeen were widows; six were divorced; six had living husbands; and the marital status of six others is unknown. Young built the Lion House, the Beehive House, the Gardo House, and the White House in downtown Salt Lake City to accommodate his sizable family. The Beehive House and the Lion House remain as prominent Salt Lake City landmarks. At the north end of the Beehive House was a family store, at which Young's wives and children had running accounts and could buy what they needed. In 1865, Karl Maeser began to privately tutor Young's fifty-six children and stopped when he was called on a mission to Germany in 1867.

At the time of Young's death, nineteen of his wives had predeceased him; he was divorced from ten, and twenty-three survived him. The status of four was unknown. A few of his wives served in administrative positions in the church, such as Zina Huntington and Eliza R. Snow. In his will

Will may refer to:

Common meanings

* Will and testament, instructions for the disposition of one's property after death

* Will (philosophy), or willpower

* Will (sociology)

* Will, volition (psychology)

* Will, a modal verb - see Shall and will

...

, Young shared his estate with the sixteen surviving wives who had lived with him; the six surviving non-conjugal wives were not mentioned in the will.

Notable descendants

In 1902, 25 years after his death, ''The New York Times'' established that Young's direct descendants numbered more than 1,000. Some of Young's descendants have become leaders in the LDS Church, as well as prominent political and cultural figures.In culture

In comics

Florence Claxton's ''The Adventures of a Woman in Search of Her Rights'' (1872), satirizes a would-be emancipated woman whose failure to establish an independent career results in her marriage to Young before she wakes to discover she's been dreaming. Brigham Young appears at the end of the bande dessinée '' Le Fil qui chante'', the last in the '' Lucky Luke'' series byRené Goscinny

René Goscinny (; ; 14 August 1926 – 5 November 1977) was a French comic editor and writer, who created the ''Asterix, Astérix'' comic book series with illustrator Albert Uderzo. Born in France to a Jewish family from Poland, he spent his chil ...

.

In literature

The Scottish poet John Lyon, who was an intimate friend of Young, wrote ''Brigham the Bold'' in tribute to him after his death.Arthur Conan Doyle

Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle (22 May 1859 – 7 July 1930) was a British writer and physician. He created the character Sherlock Holmes in 1887 for ''A Study in Scarlet'', the first of four novels and fifty-six short stories about Hol ...

gave Brigham Young a minor but pivotal in-person role in the Sherlock Holmes

Sherlock Holmes () is a Detective fiction, fictional detective created by British author Arthur Conan Doyle. Referring to himself as a "Private investigator, consulting detective" in his stories, Holmes is known for his proficiency with obser ...

short novel ''A Study in Scarlet

''A Study in Scarlet'' is an 1887 Detective fiction, detective novel by British writer Arthur Conan Doyle. The story marks the first appearance of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson, who would go on to become one of the most well-known detective ...

''. Young appears here in a scene set in 1860, some time before the novel's publication in 1887. Doyle had based this work, the first Holmes story, in part on Mormon history and portrays the Mormons and Young unsympathetically. When asked to comment, Doyle responded that he "provoked the animosity of the Mormon faithful" and that "all I said about the Danite Band and the murders is historical so I cannot withdraw that though it is likely that in a work of fiction it is stated more luridly than in a work of history." Doyle's daughter stated that, "You know father would be the first to admit that his first Sherlock Holmes novel was full of errors about the Mormons."

Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by the pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, and essayist. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has produced," with William Fau ...

devoted a chapter and much of two appendices to Young in '' Roughing It''. In the appendix, Twain describes Young as a theocratic "absolute monarch" defying the will of the U.S. government, and alleges using a dubious source that Young had ordered the Mountain Meadows massacre.

Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr., talking about his fondness of trees, joked in his '' The Autocrat of the Breakfast-Table'': "I call all trees mine that I have put my wedding-ring on, and I have as many tree-wives as Brigham Young has human ones."

In Fitz-James O'Brien's 1857 short story, "My Wife's Tempter", Brigham Young is depicted as an "apostle of hell", whose villainous disciple compels the hero's wife to annul her marriage and marry a Mormon.

In film and television

Young's character has appeared in a number of films. Dean Jagger played him in the eponymous 1940 film ''Brigham Young

Brigham Young ( ; June 1, 1801August 29, 1877) was an American religious leader and politician. He was the second President of the Church (LDS Church), president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) from 1847 until h ...

''. In '' The Avenging Angel'' (1995), he is played by Charlton Heston

Charlton Heston (born John Charles Carter; October 4, 1923 – April 5, 2008) was an American actor. He gained stardom for his leading man roles in numerous Cinema of the United States, Hollywood films including biblical epics, science-fiction f ...

. Terence Stamp plays him in the 2007 film '' September Dawn''. In '' Hell on Wheels'' (2011–2016), he is portrayed by Gregg Henry. He is played by Kim Coates in the Netflix miniseries '' American Primeval'' (2025).

In theater

In the 2011 satirical musical '' The Book of Mormon'', Young is portrayed as a tyrannical American regional warlord, cursed by God to have aclitoris

In amniotes, the clitoris ( or ; : clitorises or clitorides) is a female sex organ. In humans, it is the vulva's most erogenous zone, erogenous area and generally the primary anatomical source of female Human sexuality, sexual pleasure. Th ...

for a nose—a parable cautioning against female genital mutilation

Female genital mutilation (FGM) (also known as female genital cutting, female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) and female circumcision) is the cutting or removal of some or all of the vulva for non-medical reasons. Prevalence of female ge ...

.

Literary works

Since Young's death, a number of works have published collections of his discourses and sayings. * * * * * * * * * LDS Churcpublication number 35554

*

See also

* ''Brigham Young'' (1940 film) * Brigham Young Forest Farmhouse * Brigham Young Winter Home and Office * This Is The Place Heritage Park * Ann Eliza Young * List of people pardoned or granted clemency by the president of the United StatesNotes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * , republished online at . * * * * * * * . See also: '' The Mormon Prophet and His Harem''. * *External links

*Brigham Young Letters, MSS SC 890

a

L. Tom Perry Special Collections

Brigham Young University

Brigham Young University (BYU) is a Private education, private research university in Provo, Utah, United States. It was founded in 1875 by religious leader Brigham Young and is the flagship university of the Church Educational System sponsore ...

Tanner Trust Books

a

University of Utah Digital Library

{{DEFAULTSORT:Young, Brigham 1801 births 1877 deaths People from Whitingham, Vermont People from Mendon, New York American Freemasons American general authorities (LDS Church) American carpenters American Mormon missionaries in the United Kingdom American people of English descent American proslavery activists Converts to Mormonism from Methodism Governors of Utah Territory American Mormon missionaries in Canada Mormon pioneers Mountain Meadows Massacre Politicians from Salt Lake City People pardoned by James Buchanan Richards–Young family American city founders 19th-century Mormon missionaries Presidents of the Church (LDS Church) Apostles (LDS Church) Presidents of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles (LDS Church) Apostles of the Church of Christ (Latter Day Saints) People of the Utah War Doctrine and Covenants people Deaths from peritonitis Burials at the Mormon Pioneer Memorial Monument Religious leaders from Vermont Latter Day Saints from Utah Latter Day Saints from Vermont Latter Day Saints from Ohio Latter Day Saints from Illinois Latter Day Saints from New York (state) University and college founders Child marriage in the United States Christian miracle workers