History

There are many different methods available to load a short initial program into a computer. These methods reach from simple, physical input to removable media that can hold more complex programs.

There are many different methods available to load a short initial program into a computer. These methods reach from simple, physical input to removable media that can hold more complex programs.

Pre integrated-circuit-ROM examples

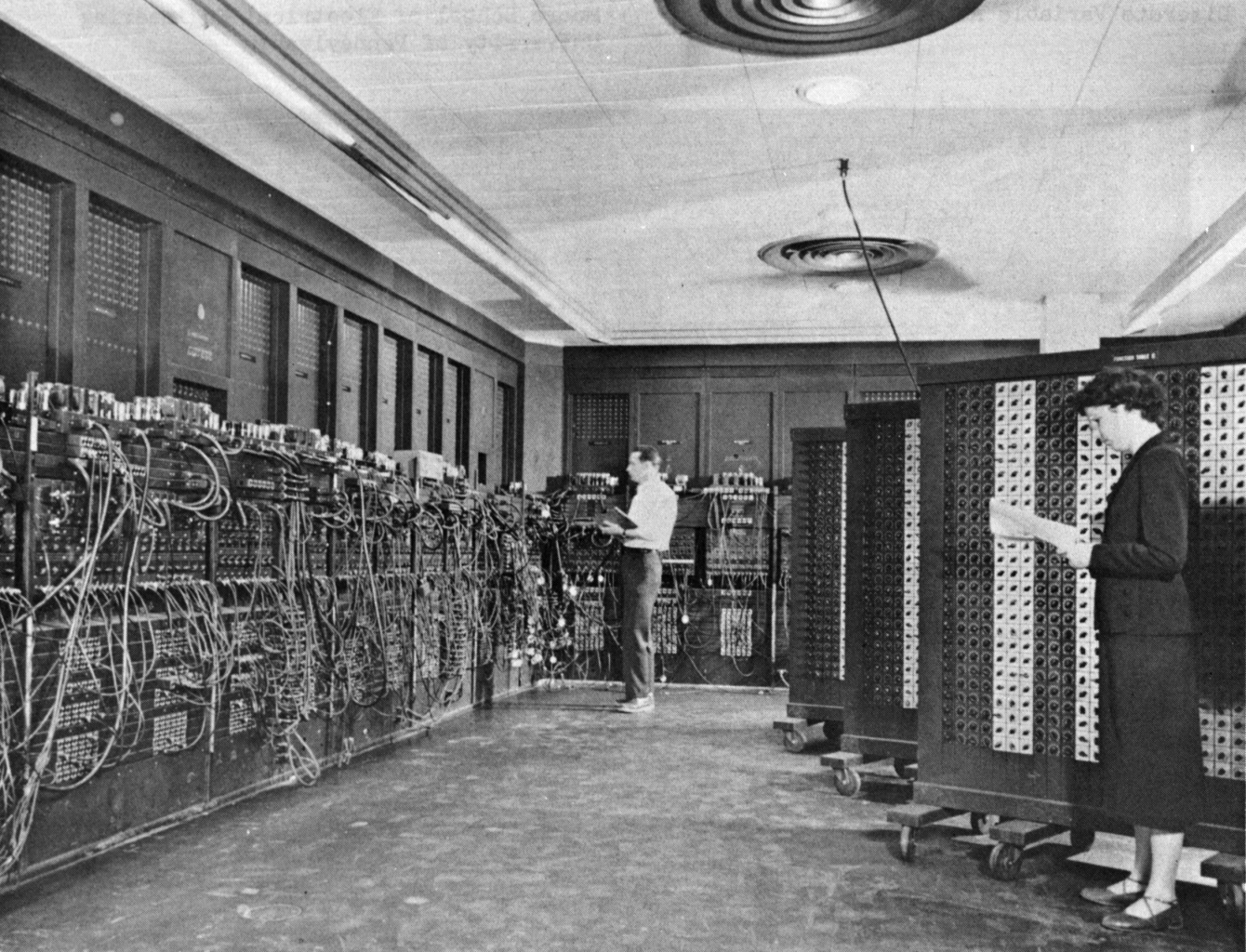

Early computers

Early computers in the 1940s and 1950s were one-of-a-kind engineering efforts that could take weeks to program, and program loading was one of many problems that had to be solved. An early computer, ENIAC, had no program stored in memory but was set up for each problem by a configuration of interconnecting cables. Bootstrapping did not apply to ENIAC, whose hardware configuration was ready for solving problems as soon as power was applied. The EDSAC system, the second stored-program computer to be built, used stepping switches to transfer a fixed program into memory when its start button was pressed. The program stored on this device, which David Wheeler (computer scientist), David Wheeler completed in late 1948, loaded further instructions from punched tape and then executed them.First commercial computers

The first programmable computers for commercial sale, such as the UNIVAC I and the IBM 701 included features to make their operation simpler. They typically included instructions that performed a complete input or output operation. The same hardware logic could be used to load the contents of a punch card (the most typical ones) or other input media, such as a magnetic drum or magnetic tape, that contained a bootstrap program by pressing a single button. This booting concept was called a variety of names for IBM computers of the 1950s and early 1960s, but IBM used the term "Initial Program Load" with the IBM 7030 Stretch and later used it for their mainframe lines, starting with the System/360 in 1964. The IBM 701 computer (1952–1956) had a "Load" button that initiated reading of the first 36-bit word (computer architecture), word into computer memory, main memory from a punched card in a punched card reader, card reader, a magnetic tape in a tape drive, or a magnetic drum unit, depending on the position of the Load Selector switch. The left 18-bit half-word was then executed as an instruction, which usually read additional words into memory. The loaded boot program was then executed, which, in turn, loaded a larger program from that medium into memory without further help from the human operator. The IBM 704, IBM 7090, and IBM 7094 had similar mechanisms, but with different load buttons for different devices. The term "boot" has been used in this sense since at least 1958.

The IBM 701 computer (1952–1956) had a "Load" button that initiated reading of the first 36-bit word (computer architecture), word into computer memory, main memory from a punched card in a punched card reader, card reader, a magnetic tape in a tape drive, or a magnetic drum unit, depending on the position of the Load Selector switch. The left 18-bit half-word was then executed as an instruction, which usually read additional words into memory. The loaded boot program was then executed, which, in turn, loaded a larger program from that medium into memory without further help from the human operator. The IBM 704, IBM 7090, and IBM 7094 had similar mechanisms, but with different load buttons for different devices. The term "boot" has been used in this sense since at least 1958.

Other IBM computers of that era had similar features. For example, the IBM 1401 system (c. 1958) used a card reader to load a program from a punched card. The 80 characters stored in the punched card were read into memory locations 001 to 080, then the computer would branch to memory location 001 to read its first stored instruction. This instruction was always the same: move the information in these first 80 memory locations to an assembly area where the information in punched cards 2, 3, 4, and so on, could be combined to form the stored program. Once this information was moved to the assembly area, the machine would branch to an instruction in location 080 (read a card) and the next card would be read and its information processed.

Another example was the IBM 650 (1953), a decimal machine, which had a group of ten 10-position switches on its operator panel which were addressable as a memory word (address 8000) and could be executed as an instruction. Thus setting the switches to 7004000400 and pressing the appropriate button would read the first card in the card reader into memory (op code 70), starting at address 400 and then jump to 400 to begin executing the program on that card. The IBM 7040, IBM 7040 and 7044 have a similar mechanism, in which the Load button causes the instruction set up in the entry keys on the front panel is executed, and the channel that instruction sets up is given a command to transfer data to memory starting at address 00100; when that transfer finishes, the CPU jumps to address 00101.

IBM's competitors also offered single button program load.

* The CDC 6600 (c. 1964) had a ''dead start'' panel with 144 toggle switches; the dead start switch entered 12 12-bit words from the toggle switches to the memory of CDC 6000 series#Peripheral processors, ''peripheral processor'' (''PP'') 0 and initiated the load sequence by causing PP 0 to execute the code loaded into memory. PP 0 loaded the necessary code into its own memory and then initialized the other PPs.

* The GE-600 series, GE 645 (c. 1965) had a "SYSTEM BOOTLOAD" button that, when pressed, caused one of the I/O controllers to load a 64-word program into memory from a diode read-only memory and deliver an interrupt to cause that program to start running.

* The first model of the PDP-10 had a "READ IN" button that, when pressed, reset the processor and started an I/O operation on a device specified by switches on the control panel, reading in a 36-bit word giving a target address and count for subsequent word reads; when the read completed, the processor started executing the code read in by jumping to the last word read in.

A noteworthy variation of this is found on the Burroughs Corporation, Burroughs B1700 where there is neither a boot ROM nor a hardwired IPL operation. Instead, after the system is reset it reads and executes microinstructions sequentially from a cassette tape drive mounted on the front panel; this sets up a boot loader in RAM which is then executed. However, since this makes few assumptions about the system it can equally well be used to load diagnostic (Maintenance Test Routine) tapes which display an intelligible code on the front panel even in cases of gross CPU failure.

Other IBM computers of that era had similar features. For example, the IBM 1401 system (c. 1958) used a card reader to load a program from a punched card. The 80 characters stored in the punched card were read into memory locations 001 to 080, then the computer would branch to memory location 001 to read its first stored instruction. This instruction was always the same: move the information in these first 80 memory locations to an assembly area where the information in punched cards 2, 3, 4, and so on, could be combined to form the stored program. Once this information was moved to the assembly area, the machine would branch to an instruction in location 080 (read a card) and the next card would be read and its information processed.

Another example was the IBM 650 (1953), a decimal machine, which had a group of ten 10-position switches on its operator panel which were addressable as a memory word (address 8000) and could be executed as an instruction. Thus setting the switches to 7004000400 and pressing the appropriate button would read the first card in the card reader into memory (op code 70), starting at address 400 and then jump to 400 to begin executing the program on that card. The IBM 7040, IBM 7040 and 7044 have a similar mechanism, in which the Load button causes the instruction set up in the entry keys on the front panel is executed, and the channel that instruction sets up is given a command to transfer data to memory starting at address 00100; when that transfer finishes, the CPU jumps to address 00101.

IBM's competitors also offered single button program load.

* The CDC 6600 (c. 1964) had a ''dead start'' panel with 144 toggle switches; the dead start switch entered 12 12-bit words from the toggle switches to the memory of CDC 6000 series#Peripheral processors, ''peripheral processor'' (''PP'') 0 and initiated the load sequence by causing PP 0 to execute the code loaded into memory. PP 0 loaded the necessary code into its own memory and then initialized the other PPs.

* The GE-600 series, GE 645 (c. 1965) had a "SYSTEM BOOTLOAD" button that, when pressed, caused one of the I/O controllers to load a 64-word program into memory from a diode read-only memory and deliver an interrupt to cause that program to start running.

* The first model of the PDP-10 had a "READ IN" button that, when pressed, reset the processor and started an I/O operation on a device specified by switches on the control panel, reading in a 36-bit word giving a target address and count for subsequent word reads; when the read completed, the processor started executing the code read in by jumping to the last word read in.

A noteworthy variation of this is found on the Burroughs Corporation, Burroughs B1700 where there is neither a boot ROM nor a hardwired IPL operation. Instead, after the system is reset it reads and executes microinstructions sequentially from a cassette tape drive mounted on the front panel; this sets up a boot loader in RAM which is then executed. However, since this makes few assumptions about the system it can equally well be used to load diagnostic (Maintenance Test Routine) tapes which display an intelligible code on the front panel even in cases of gross CPU failure.

IBM System/360 and successors

In the IBM System/360 and its successors, including the current z/Architecture machines, the boot process is known as IBM System/360 architecture#Initial Program Load, ''Initial Program Load'' (IPL). IBM coined this term for the IBM 7030 Stretch, 7030 (Stretch), revived it for the design of the System/360, and continues to use it in those environments today. In the System/360 processors, an IPL is initiated by the computer operator by selecting the three hexadecimal digit device address (CUU; C=I/O Channel address, UU=Control unit and Device addressUU was often of the form Uu, U=Control unit address, u=Device address, but some control units attached only 8 devices; some attached more than 16. Indeed, the 3830 DASD controller offered 32-drive-addressing as an option.) followed by pressing the ''LOAD'' button. On the high end System/360 models, mostExcluding the 370/145 and 370/155, which used a 3210 or 3215 console typewriter. System/370 and some later systems, the functions of the switches and the LOAD button are simulated using selectable areas on the screen of a graphics console, oftenOnly the S/360 used the 2250; the 360/85, 370/165 and 370/168 used a keyboard/display device compatible with nothing else. an IBM 2250-like device or an IBM 3270-like device. For example, on the System/370 Model 158, the keyboard sequence 0-7-X (zero, seven and X, in that order) results in an IPL from the device address that was keyed into the input area. The Amdahl Corporation, Amdahl 470V/6 and related CPUs supported four hexadecimal digits on those CPUs which had the optional second channel unit installed, for a total of 32 channels. Later, IBM would also support more than 16 channels. The IPL function in the System/360 and its successors prior to IBM Z, and its compatibles such as Amdahl's, reads 24 bytes from an operator-specified device into main storage starting at real address zero. The second and third groups of eight bytes are treated as Channel Command Words (CCWs) to continue loading the startup program (the first CCW is always simulated by the CPU and consists of a Read IPL command, , with command chaining and suppress incorrect length indication being enforced). When the I/O channel commands are complete, the first group of eight bytes is then loaded into the processor's Program Status Word (PSW) and the startup program begins execution at the location designated by that PSW. The IPL device is usually a disk drive, hence the special significance of the read-type command, but exactly the same procedure is also used to IPL from other input-type devices, such as tape drives, or even card readers, in a device-independent manner, allowing, for example, the installation of an operating system on a brand-new computer from an OS initial distribution magnetic tape. For disk controllers, the command also causes the selected device to seek to cylinder , head , simulating a Seek cylinder and head command, , and to search for record , simulating a Search ID Equal command, ; seeks and searches are not simulated by tape and card controllers, as for these device classes a Read IPL command is simply a sequential read command. The disk, tape or card deck must contain a special program to load the actual operating system or standalone utility into main storage, and for this specific purpose "IPL Text" is placed on the disk by the stand-alone DASDI (Direct Access Storage Device Initialization) program or an equivalent program running under an operating system, e.g., ICKDSF, but IPL-able tapes and card decks are usually distributed with this "IPL Text" already present. IBM introduced some evolutionary changes in the IPL process, changing some details for System/370 Extended Architecture (S/370-XA) and later, and adding a new type of IPL for z/Architecture.Minicomputers

Minicomputers, starting with the Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) PDP-5 and PDP-8 (1965) simplified design by using the CPU to assist input and output operations. This saved cost but made booting more complicated than pressing a single button. Minicomputers typically had some way to ''toggle in'' short programs by manipulating an array of switches on the front panel. Since the early minicomputers used magnetic-core memory, which did not lose its information when power was off, these bootstrap loaders would remain in place unless they were erased. Erasure sometimes happened accidentally when a program bug caused a loop that overwrote all of memory.

Other minicomputers with such simple form of booting include Hewlett-Packard's HP 2100 series (mid-1960s), the original Data General Nova (1969), and DEC's PDP-4 (1962) and PDP-11 (1970).

As the I/O operations needed to cause a read operation on a minicomputer I/O device were typically different for different device controllers, different bootstrap programs were needed for different devices.

DEC later added, in 1971, an optional diode matrix read-only memory for the PDP-11 that stored a bootstrap program of up to 32 words (64 bytes). It consisted of a printed circuit card, the M792, that plugged into the Unibus and held a 32 by 16 array of semiconductor diodes. With all 512 diodes in place, the memory contained all "one" bits; the card was programmed by cutting off each diode whose bit was to be "zero". DEC also sold versions of the card, the BM792-Yx series, pre-programmed for many standard input devices by simply omitting the unneeded diodes.

Following the older approach, the earlier PDP-1 has a hardware loader, such that an operator need only push the "load" switch to instruct the paper tape reader to load a program directly into core memory. The PDP-7, PDP-9, and PDP-15 successors to the PDP-4 have an added Read-In button to read a program in from paper tape and jump to it. The Data General Data General Nova#SuperNOVA, Supernova used front panel switches to cause the computer to automatically load instructions into memory from a device specified by the front panel's data switches, and then jump to loaded code.

Minicomputers, starting with the Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) PDP-5 and PDP-8 (1965) simplified design by using the CPU to assist input and output operations. This saved cost but made booting more complicated than pressing a single button. Minicomputers typically had some way to ''toggle in'' short programs by manipulating an array of switches on the front panel. Since the early minicomputers used magnetic-core memory, which did not lose its information when power was off, these bootstrap loaders would remain in place unless they were erased. Erasure sometimes happened accidentally when a program bug caused a loop that overwrote all of memory.

Other minicomputers with such simple form of booting include Hewlett-Packard's HP 2100 series (mid-1960s), the original Data General Nova (1969), and DEC's PDP-4 (1962) and PDP-11 (1970).

As the I/O operations needed to cause a read operation on a minicomputer I/O device were typically different for different device controllers, different bootstrap programs were needed for different devices.

DEC later added, in 1971, an optional diode matrix read-only memory for the PDP-11 that stored a bootstrap program of up to 32 words (64 bytes). It consisted of a printed circuit card, the M792, that plugged into the Unibus and held a 32 by 16 array of semiconductor diodes. With all 512 diodes in place, the memory contained all "one" bits; the card was programmed by cutting off each diode whose bit was to be "zero". DEC also sold versions of the card, the BM792-Yx series, pre-programmed for many standard input devices by simply omitting the unneeded diodes.

Following the older approach, the earlier PDP-1 has a hardware loader, such that an operator need only push the "load" switch to instruct the paper tape reader to load a program directly into core memory. The PDP-7, PDP-9, and PDP-15 successors to the PDP-4 have an added Read-In button to read a program in from paper tape and jump to it. The Data General Data General Nova#SuperNOVA, Supernova used front panel switches to cause the computer to automatically load instructions into memory from a device specified by the front panel's data switches, and then jump to loaded code.

= Early minicomputer boot loader examples

= In a minicomputer with a paper tape reader, the first program to run in the boot process, the boot loader, would read into core memory either the second-stage boot loader (often called a ''Binary Loader'') that could read paper tape with checksum or the operating system from an outside storage medium. Pseudocode for the boot loader might be as simple as the following eight instructions: # Set the P register to 9 # Check paper tape reader ready # If not ready, jump to 2 # Read a byte from paper tape reader to accumulator # Store accumulator to address in P register # If end of tape, jump to 9 # Increment the P register # Jump to 2 A related example is based on a loader for a Nicolet Instrument Corporation minicomputer of the 1970s, using the paper tape reader-punch unit on a Teletype Model 33 ASR teleprinter. The bytes of its second-stage loader are read from paper tape in reverse order. # Set the P register to 106 # Check paper tape reader ready # If not ready, jump to 2 # Read a byte from paper tape reader to accumulator # Store accumulator to address in P register # Decrement the P register # Jump to 2 The length of the second stage loader is such that the final byte overwrites location 7. After the instruction in location 6 executes, location 7 starts the second stage loader executing. The second stage loader then waits for the much longer tape containing the operating system to be placed in the tape reader. The difference between the boot loader and second stage loader is the addition of checking code to trap paper tape read errors, a frequent occurrence with relatively low-cost, "part-time-duty" hardware, such as the Teletype Model 33 ASR. (Friden Flexowriters were far more reliable, but also comparatively costly.)Booting the first microcomputers

The earliest microcomputers, such as the Altair 8800 (released first in 1975) and an even earlier, similar machine (based on the Intel 8008 CPU) had no bootstrapping hardware as such. When powered-up, the CPU would see memory that would contain random data. The front panels of these machines carried toggle switches for entering addresses and data, one switch per bit of the computer memory word and address bus. Simple additions to the hardware permitted one memory location at a time to be loaded from those switches to store bootstrap code. Meanwhile, the CPU was kept from attempting to execute memory content. Once correctly loaded, the CPU was enabled to execute the bootstrapping code. This process, similar to that used for several earlier minicomputers, was tedious and had to be error-free.Integrated circuit read-only memory era

The introduction of integrated circuit read-only memory (ROM), with its many variants, including Mask ROM, mask-programmed ROMs, programmable ROMs (PROM), erasable programmable ROMs (EPROM), and flash memory, reduced the physical size and cost of ROM. This allowed firmware boot programs to be included as part of the computer.

The introduction of integrated circuit read-only memory (ROM), with its many variants, including Mask ROM, mask-programmed ROMs, programmable ROMs (PROM), erasable programmable ROMs (EPROM), and flash memory, reduced the physical size and cost of ROM. This allowed firmware boot programs to be included as part of the computer.

Minicomputers

The Data General Data General Nova#1200 and 800, Nova 1200 (1970) and Data General Nova#1200 and 800, Nova 800 (1971) had a program load switch that, in combination with options that provided two ROM chips, loaded a program into main memory from those ROM chips and jumped to it. Digital Equipment Corporation introduced the integrated-circuit-ROM-based BM873 (1974), M9301 (1977), M9312 (1978), REV11-A and REV11-C, MRV11-C, and MRV11-D ROM memories, all usable as bootstrap ROMs. The PDP-11/34 (1976), PDP-11/60 (1977), PDP-11/24 (1979), and most later models include boot ROM modules. An Italian telephone switching computer, called "Gruppi Speciali", patented in 1975 by Alberto Ciaramella, a researcher at CSELT, included an (external) ROM. Gruppi Speciali was, starting from 1975, a fully single-button machine booting into the operating system from a ROM memory composed from semiconductors, not from ferrite cores. Although the ROM device was not natively embedded in the computer of Gruppi Speciali, due to the design of the machine, it also allowed the single-button ROM booting in machines not designed for that (therefore, this "bootstrap device" was architecture-independent), e.g. the PDP-11. Storing the state of the machine after the switch-off was also in place, which was another critical feature in the telephone switching contest. Some minicomputers and superminicomputers include a separate console processor that bootstraps the main processor. The PDP-11/44 had an Intel 8085 as a console processor; the VAX-11/780, the first member of Digital's VAX line of 32-bit superminicomputers, had an LSI-11-based console processor, and the VAX-11/730 had an 8085-based console processor. These console processors could boot the main processor from various storage devices. Some other superminicomputers, such as the VAX-11/750, implement console functions, including the first stage of booting, in CPU microcode.Microprocessors and microcomputers

Typically, a microprocessor will, after a reset or power-on condition, perform a start-up process that usually takes the form of "begin execution of the code that is found starting at a specific address" or "look for a multibyte code at a specific address and jump to the indicated location to begin execution". A system built using that microprocessor will have the permanent ROM occupying these special locations so that the system always begins operating without operator assistance. For example, Intel x86 processors always start by running the instructions beginning at F000:FFF0, while for the MOS 6502 processor, initialization begins by reading a two-byte vector address at $FFFD (MS byte) and $FFFC (LS byte) and jumping to that location to run the bootstrap code. Apple Computer's first computer, the Apple I, Apple 1 introduced in 1976, featured PROM chips that eliminated the need for a front panel for the boot process (as was the case with the Altair 8800) in a commercial computer. According to Apple's ad announcing it "No More Switches, No More Lights ... the firmware in PROMS enables you to enter, display and debug programs (all in hex) from the keyboard." Due to the expense of read-only memory at the time, the Apple II booted its disk operating systems using a series of very small incremental steps, each passing control onward to the next phase of the gradually more complex boot process. (See Apple DOS#Boot loader, Apple DOS: Boot loader). Because so little of the disk operating system relied on ROM, the hardware was also extremely flexible and supported a wide range of customized disk copy protection mechanisms. (See Software cracking#History, Software Cracking: History.) Some operating systems, most notably pre-1995 Macintosh systems from Apple Inc., Apple, are so closely interwoven with their hardware that it is impossible to natively boot an operating system other than the standard one. This is the opposite extreme of the scenario using switches mentioned above; it is highly inflexible but relatively error-proof and foolproof as long as all hardware is working normally. A common solution in such situations is to design a boot loader that works as a program belonging to the standard OS that hijacks the system and loads the alternative OS. This technique was used by Apple for its A/UX Unix implementation and copied by various freeware operating systems and BeOS, BeOS Personal Edition 5. Some machines, like the Atari ST microcomputer, were "instant-on", with the operating system executing from a ROM. Retrieval of the OS from secondary or tertiary store was thus eliminated as one of the characteristic operations for bootstrapping. To allow system customizations, accessories, and other support software to be loaded automatically, the Atari's floppy drive was read for additional components during the boot process. There was a timeout delay that provided time to manually insert a floppy as the system searched for the extra components. This could be avoided by inserting a blank disk. The Atari ST hardware was also designed so the cartridge slot could provide native program execution for gaming purposes as a holdover from Atari's legacy making electronic games; by inserting the Spectre GCR cartridge with the Macintosh system ROM in the game slot and turning the Atari on, it could "natively boot" the Macintosh operating system rather than Atari's own Atari TOS, TOS. The IBM Personal Computer included ROM-based firmware called the BIOS; one of the functions of that firmware was to perform a power-on self test when the machine was powered up, and then to read software from a boot device and execute it. Firmware compatible with the BIOS on the IBM Personal Computer is used in IBM PC compatible computers. The UEFI was developed by Intel, originally for Itanium-based machines, and later also used as an alternative to the BIOS in x86-based machines, including Apple–Intel architecture, Apple Macs using Intel processors. Unix workstations originally had vendor-specific ROM-based firmware. Sun Microsystems later developed OpenBoot, later known as Open Firmware, which incorporated a Forth (programming language), Forth interpreter, with much of the firmware being written in Forth. It was standardized by the IEEE as IEEE standard ; firmware that implements that standard was used in PowerPC-based Macintosh, Macs and some other PowerPC-based machines, as well as Sun's own SPARC-based computers. The Advanced RISC Computing specification defined another firmware standard, which was implemented on some MIPS architecture, MIPS-based and DEC Alpha, Alpha-based machines and the SGI Visual Workstation x86-based workstations.Modern boot loaders

When a computer is turned off, its softwareincluding operating systems, application code, and dataremains stored on non-volatile memory. When the computer is powered on, it typically does not have an operating system or its loader in random-access memory (RAM). The computer first executes a relatively small program stored in read-only memory (ROM, and later EEPROM, NOR flash) which support execute in place, to initialize CPU and motherboard, to initialize the memory (especially on x86 systems), to initialize and access the storage (usually a block-addressed device, e.g. hard disk drive, NAND flash, solid-state drive) from which the operating system programs and data can be loaded into RAM, and to initialize other I/O devices. The small program that starts this sequence is known as a ''bootstrap loader'', ''bootstrap'' or ''boot loader''. Often, multiple-stage boot loaders are used, during which several programs of increasing complexity load one after the other in a process of chain loading. Some earlier computer systems, upon receiving a boot signal from a human operator or a peripheral device, may load a very small number of fixed instructions into memory at a specific location, initialize at least one CPU, and then point the CPU to the instructions and start their execution. These instructions typically start an input operation from some peripheral device (which may be switch-selectable by the operator). Other systems may send hardware commands directly to peripheral devices or I/O controllers that cause an extremely simple input operation (such as "read sector zero of the system device into memory starting at location 1000") to be carried out, effectively loading a small number of boot loader instructions into memory; a completion signal from the I/O device may then be used to start execution of the instructions by the CPU. Smaller computers often use less flexible but more automatic boot loader mechanisms to ensure that the computer starts quickly and with a predetermined software configuration. In many desktop computers, for example, the bootstrapping process begins with the CPU executing software contained in ROM (for example, the BIOS of an IBM PC) at a predefined address (some CPUs, including the Intel Intel 8086, x86 series are designed to execute this software after reset without outside help). This software contains rudimentary functionality to search for devices eligible to participate in booting, and load a small program from a special section (most commonly the boot sector) of the most promising device, typically starting at a fixed entry point such as the start of the sector. Boot loaders may face peculiar constraints, especially in size; for instance, on the IBM PC and compatibles, the boot code must fit in the Master Boot Record (MBR) and the Partition Boot Record (PBR), which in turn are limited to a single sector; on the IBM System/360, the size is limited by the IPL medium, e.g., Punched card, card size, track size. On systems with those constraints, the first program loaded into RAM may not be sufficiently large to load the operating system and, instead, must load another, larger program. The first program loaded into RAM is called a first-stage boot loader, and the program it loads is called a second-stage boot loader. On many embedded CPUs, the CPU built-in boot ROM, sometimes called the zero-stage boot loader, can find and load first-stage boot loaders.First-stage boot loaders

Examples of first-stage (hardware initialization stage) boot loaders include BIOS, UEFI, coreboot, Libreboot and Das U-Boot. On the IBM PC, the boot loader in the Master Boot Record (MBR) and the Partition Boot Record (PBR) was coded to require at least 32 KB (later expanded to 64 KB) of system memory and only use instructions supported by the original 8088/8086 processors.Second-stage boot loaders

Second-stage (OS initialization stage) boot loaders, such as shim, GNU GRUB, rEFInd, BOOTMGR, Syslinux, and NTLDR, are not themselves operating systems, but are able to load an operating system properly and transfer execution to it; the operating system subsequently initializes itself and may load extra device drivers. The second-stage boot loader does not need drivers for its own operation, but may instead use generic storage access methods provided by system firmware such as the BIOS, UEFI or Open Firmware, though typically with restricted hardware functionality and lower performance. Many boot loaders (like GNU GRUB, rEFInd, Windows's BOOTMGR, Syslinux, and Windows NT/2000/XP's NTLDR) can be configured to give the user multiple booting choices. These choices can include different operating systems (for dual boot, dual or multi-booting from different partitions or drives), different versions of the same operating system (in case a new version has unexpected problems), different operating system loading options (e.g., booting into a rescue or safe mode), and some standalone programs that can function without an operating system, such as memory testers (e.g., memtest86+), a basic shell (as in GNU GRUB), or even games (see List of PC Booter games). Some boot loaders can also load other boot loaders; for example, GRUB loads BOOTMGR instead of loading Windows directly. Usually a default choice is preselected with a time delay during which a user can press a key to change the choice; after this delay, the default choice is automatically run so normal booting can occur without interaction. The boot process can be considered complete when the computer is ready to interact with the user, or the operating system is capable of running system programs or application programs.Embedded and multi-stage boot loaders

Many embedded systems must boot immediately. For example, waiting a minute for a Television set, digital television or a GPS navigation device to start is generally unacceptable. Therefore, such devices have software systems in ROM or flash memory so the device can begin functioning immediately; little or no loading is necessary, because the loading can be precomputed and stored on the ROM when the device is made. Large and complex systems may have boot procedures that proceed in multiple phases until finally the operating system and other programs are loaded and ready to execute. Because operating systems are designed as if they never start or stop, a boot loader might load the operating system, configure itself as a mere process within that system, and then irrevocably transfer control to the operating system. The boot loader then terminates normally as any other process would.Network booting

Most computers are also capable of booting over a computer network. In this scenario, the operating system is stored on the disk of a server (computing), server, and certain parts of it are transferred to the client using a simple protocol such as the Trivial File Transfer Protocol (TFTP). After these parts have been transferred, the operating system takes over the control of the booting process. As with the second-stage boot loader, network booting begins by using generic network access methods provided by the network interface's boot ROM, which typically contains a Preboot Execution Environment (PXE) image. No drivers are required, but the system functionality is limited until the operating system kernel and drivers are transferred and started. As a result, once the ROM-based booting has completed it is entirely possible to network boot into an operating system that itself does not have the ability to use the network interface.IBM-compatible personal computers (PC)

Boot devices

The boot device is the storage device from which the operating system is loaded. A modern PC's UEFI or BIOS firmware supports booting from various devices, typically a local solid-state drive or hard disk drive via the GUID Partition Table, GPT or Master Boot Record (MBR) on such a drive or disk, an optical disc drive (using El Torito (CD-ROM standard), El Torito), a USB mass storage device (USB flash drive, memory card reader, USB hard disk drive, USB optical disc drive, USB solid-state drive, etc.), or a network interface card (using Preboot Execution Environment, PXE). Older, less common BIOS-bootable devices include boot floppy, floppy disk drives, Zip drives, and LS-120 drives.

Typically, the system firmware (UEFI or BIOS) will allow the user to configure a ''boot order''. If the boot order is set to "first, the DVD drive; second, the hard disk drive", then the firmware will try to boot from the DVD drive, and if this fails (e.g. because there is no DVD in the drive), it will try to boot from the local hard disk drive.

For example, on a PC with Windows installed on the hard drive, the user could set the boot order to the one given above, and then insert a Linux Live CD in order to try out Linux without having to install an operating system onto the hard drive. This is an example of dual booting, in which the user chooses which operating system to start after the computer has performed its power-on self-test (POST). In this example of dual booting, the user chooses by inserting or removing the DVD from the computer, but it is more common to choose which operating system to boot by selecting from a boot manager menu on the selected device, by using the computer keyboard to select from a BIOS or UEFI boot menu, or both; the boot menu is typically entered by pressing or keys during the POST; the BIOS setup is typically entered by pressing or keys during the POST.

Several devices are available that enable the user to ''quick-boot'' into what is usually a variant of Linux for various simple tasks such as Internet access; examples are Splashtop OS, Splashtop and Latitude ON.

The boot device is the storage device from which the operating system is loaded. A modern PC's UEFI or BIOS firmware supports booting from various devices, typically a local solid-state drive or hard disk drive via the GUID Partition Table, GPT or Master Boot Record (MBR) on such a drive or disk, an optical disc drive (using El Torito (CD-ROM standard), El Torito), a USB mass storage device (USB flash drive, memory card reader, USB hard disk drive, USB optical disc drive, USB solid-state drive, etc.), or a network interface card (using Preboot Execution Environment, PXE). Older, less common BIOS-bootable devices include boot floppy, floppy disk drives, Zip drives, and LS-120 drives.

Typically, the system firmware (UEFI or BIOS) will allow the user to configure a ''boot order''. If the boot order is set to "first, the DVD drive; second, the hard disk drive", then the firmware will try to boot from the DVD drive, and if this fails (e.g. because there is no DVD in the drive), it will try to boot from the local hard disk drive.

For example, on a PC with Windows installed on the hard drive, the user could set the boot order to the one given above, and then insert a Linux Live CD in order to try out Linux without having to install an operating system onto the hard drive. This is an example of dual booting, in which the user chooses which operating system to start after the computer has performed its power-on self-test (POST). In this example of dual booting, the user chooses by inserting or removing the DVD from the computer, but it is more common to choose which operating system to boot by selecting from a boot manager menu on the selected device, by using the computer keyboard to select from a BIOS or UEFI boot menu, or both; the boot menu is typically entered by pressing or keys during the POST; the BIOS setup is typically entered by pressing or keys during the POST.

Several devices are available that enable the user to ''quick-boot'' into what is usually a variant of Linux for various simple tasks such as Internet access; examples are Splashtop OS, Splashtop and Latitude ON.

Boot sequence

Upon starting, an IBM-compatible personal computer's x86 CPU, executes in real mode, the instruction located at reset vector (the physical memory address on 16-bit x86 processors and on 32-bit and 64-bit x86 processors), usually pointing to the firmware (UEFI or BIOS) entry point inside the ROM. This memory location typically contains a jump instruction that transfers execution to the location of the firmware (UEFI or BIOS) start-up program. This program runs a power-on self-test (POST) to check and initialize required devices such as main memory (DRAM), the PCI bus and the PCI devices (including running embedded option ROMs). One of the most involved steps is setting up DRAM over Serial Presence Detect, SPD, further complicated by the fact that at this point memory is very limited.

After initializing required hardware, the firmware (UEFI or BIOS) goes through a pre-configured list of Non-volatile memory, non-volatile storage devices ("boot device sequence") until it finds one that is bootable.

Upon starting, an IBM-compatible personal computer's x86 CPU, executes in real mode, the instruction located at reset vector (the physical memory address on 16-bit x86 processors and on 32-bit and 64-bit x86 processors), usually pointing to the firmware (UEFI or BIOS) entry point inside the ROM. This memory location typically contains a jump instruction that transfers execution to the location of the firmware (UEFI or BIOS) start-up program. This program runs a power-on self-test (POST) to check and initialize required devices such as main memory (DRAM), the PCI bus and the PCI devices (including running embedded option ROMs). One of the most involved steps is setting up DRAM over Serial Presence Detect, SPD, further complicated by the fact that at this point memory is very limited.

After initializing required hardware, the firmware (UEFI or BIOS) goes through a pre-configured list of Non-volatile memory, non-volatile storage devices ("boot device sequence") until it finds one that is bootable.

BIOS

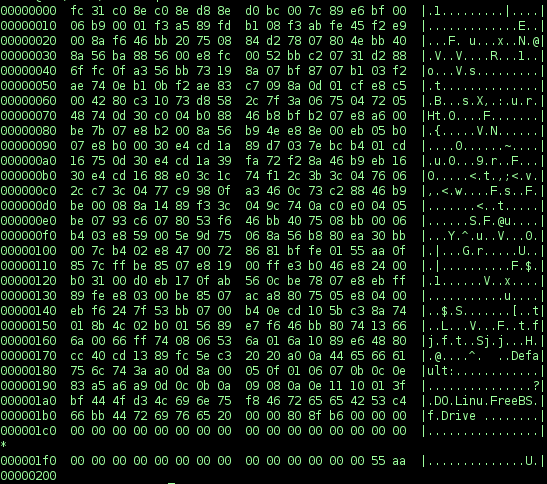

Once the BIOS has found a bootable device it loads the boot sector to linear address (usually X86 memory segmentation, segment:Offset (computer science), offset :, but some BIOSes erroneously use :) and transfers execution to the boot code. In the case of a hard disk, this is referred to as the Master Boot Record (MBR). The conventional MBR code checks the MBR's partition table for a partition set as ''bootable''The active partition may contain a Second-stage boot loader, e.g., OS/2 Boot Manager, rather than an OS. (the one with ''active'' flag set). If an active partition is found, the MBR code loads the boot sector code from that partition, known as Volume Boot Record (VBR), and executes it. The MBR boot code is often operating-system specific. A bootable MBR device is defined as one that can be read from, and where the last two bytes of the first sector contain the little-endian Word (data type), word , found as byte sequence , on disk (also known as the MBR boot signature), or where it is otherwise established that the code inside the sector is executable on x86 PCs. The boot sector code is the first-stage boot loader. It is located on fixed disks and removable drives, and must fit into the first 446 bytes of the Master Boot Record in order to leave room for the default 64-byte partition table with four partition entries and the two-byte MBR boot signature, boot signature, which the BIOS requires for a proper boot loader — or even less, when additional features like more than four partition entries (up to 16 with 16 bytes each), a MBR disk signature, disk signature (6 bytes), a MBR disk timestamp, disk timestamp (6 bytes), an Advanced Active Partition (18 bytes) or special multi-boot loaders have to be supported as well in some environments. In floppy and superfloppy Volume Boot Records, up to 59 bytes are occupied for the Extended BIOS Parameter Block on FAT12 and FAT16 volumes since DOS 4.0, whereas the FAT32 EBPB introduced with DOS 7.1 requires even 87 bytes, leaving only 423 bytes for the boot loader when assuming a sector size of 512 bytes. Microsoft boot sectors therefore traditionally imposed certain restrictions on the boot process, for example, the boot file had to be located at a fixed position in the root directory of the file system and stored as consecutive sectors, conditions taken care of by theSYS (DOS command), SYS command and slightly relaxed in later versions of DOS. The boot loader was then able to load the first three sectors of the file into memory, which happened to contain another embedded boot loader able to load the remainder of the file into memory. When Microsoft added Logical block addressing, LBA and FAT32 support, they even switched to a boot loader reaching over ''two'' physical sectors and using 386 instructions for size reasons. At the same time other vendors managed to squeeze much more functionality into a single boot sector without relaxing the original constraints on only minimal available memory (32 KB) and processor support (). For example, DR-DOS boot sectors are able to locate the boot file in the FAT12, FAT16 and FAT32 file system, and load it into memory as a whole via cylinder-head-sector, CHS or LBA, even if the file is not stored in a fixed location and in consecutive sectors.

The VBR is often OS-specific; however, its main function is to load and execute the operating system boot loader file (such as bootmgr or ntldr), which is the second-stage boot loader, from an active partition. Then the boot loader loads the OS kernel from the storage device.

If there is no active partition, or the active partition's boot sector is invalid, the MBR may load a secondary boot loader which will select a partition (often via user input) and load its boot sector, which usually loads the corresponding operating system kernel. In some cases, the MBR may also attempt to load secondary boot loaders before trying to boot the active partition. If all else fails, it should issue an INT (x86 instruction), INT 18h BIOS interrupt call (followed by an INT 19h just in case INT 18h would return) in order to give back control to the BIOS, which would then attempt to boot off other devices, attempt a network booting, remote boot via network.

UEFI

Many modern systems (Intel Macs and newer Personal computer, PCs) use UEFI. Unlike BIOS, UEFI (not Legacy boot via CSM) does not rely on boot sectors, UEFI system loads the boot loader (EFI application file in USB disk or in the EFI System Partition) directly, and the OS kernel is loaded by the boot loader.SoCs, embedded systems, microcontrollers, and FPGAs

Security

Various measures have been implemented which enhance the Computer security, security of the booting process. Some of them are made mandatory, others can be disabled or enabled by the end user. Traditionally, booting did not involve the use of cryptography. The security can be bypassed by Bootloader unlocking, unlocking the boot loader, which might or might not be approved by the manufacturer. Modern boot loaders make use of concurrency, meaning they can run multiple processor cores and threads at the same time, which add extra layers of complexity to secure booting. Matthew Garrett argued that booting security serves a legitimate goal but in doing so chooses Default (computer science), defaults that are hostile to users.Measures

* UEFI secure boot * Android Verified boot * Samsung Knox * Measured boot with the Trusted Platform Module, also known as "trusted boot". * Intel BootGuard * Disk encryption * Firmware passwordsBootloop

When debugging a concurrent and distributed system of systems, a bootloop (also written boot loop or boot-loop) is a diagnostic condition of an #Detection of an erroneous state, erroneous state that occurs on computing devices; when those devices repeatedly fail to complete the booting process and Reboot, restart before a boot sequence is finished, a restart might prevent a user from accessing the regular interface.

When debugging a concurrent and distributed system of systems, a bootloop (also written boot loop or boot-loop) is a diagnostic condition of an #Detection of an erroneous state, erroneous state that occurs on computing devices; when those devices repeatedly fail to complete the booting process and Reboot, restart before a boot sequence is finished, a restart might prevent a user from accessing the regular interface.

Detection of an erroneous state

The system might exhibit its erroneous state in, for example, an explicit bootloop or a blue screen of death, before recovery is indicated. Detection of an erroneous state may require a Apache Kafka, distributed event store and stream-processing platform for real-time operation of a distributed system.Recovery from an erroneous state

An erroneous state can trigger bootloops; this state can be caused by misconfiguration from previously known-good operations. Recovery attempts from that erroneous state then enter a reboot, in an attempt to return to a known-good state. In Windows OS operations, for example, the recovery procedure was to reboot three times, the reboots needed to return to a usable menu.Recovery policy

Recovery might be specified via Security Assertion Markup Language (SAML), which can also implement Single sign-on (SSO) for some applications; in the zero trust security model identification, authorization, and authentication are separable concerns in an SSO session. When recovery of a site is indicated (viz. a blue screen of death is displayed on an airport terminal screen) personal site visits might be required to remediate the situation.Examples

* Windows NT 4.0 * Windows 2000 * Windows Server * Windows 10 * The Nexus 5X * Android 10: when setting a specific image as wallpaper, the luminance value exceeded the maximum of 255 which happened due to a rounding error during conversion from sRGB to RGB color spaces, RGB. This then crashed the SystemUI component on every boot. * Google Nest hub * LG smartphone bootloop issues * On 19 July 2024, an update of CrowdStrikes Falcon software caused the 2024 CrowdStrike incident resulting in Microsoft Windows systems worldwide stuck in bootloops or recovery mode.See also

* * Multi-booting * Boot disk * Bootkit * Comparison of boot loaders * Linux startup process * Macintosh startup * Microreboot * Multi boot * Network booting * RedBoot * Self-booting disk * Windows startup processNotes

References

{{Firmware and booting Booting,