Black Dahlia (computer Game) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

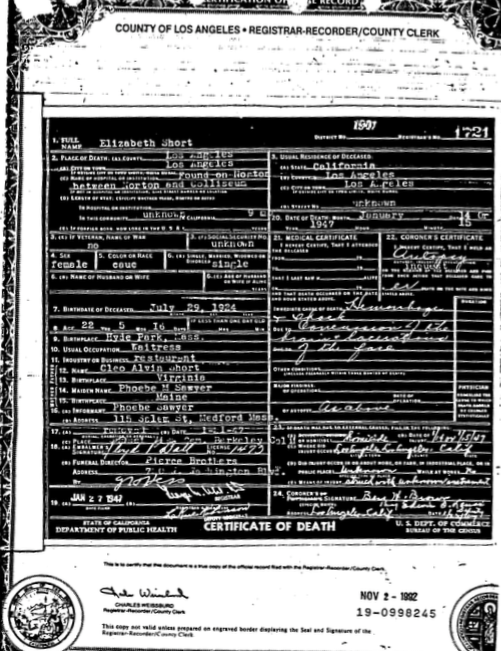

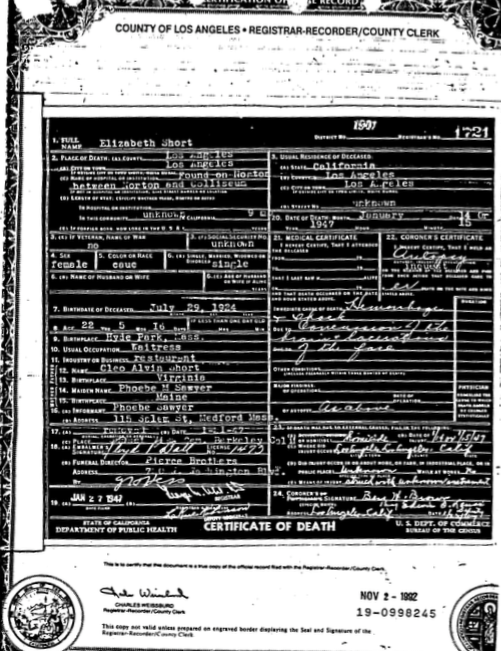

Elizabeth Short (July 29, 1924 – , 1947), posthumously known as the Black Dahlia, was an American woman found murdered in the

In late 1942, Short's mother received a letter of apology from her presumed-deceased husband, which revealed that he was in fact alive and had started a new life in

In late 1942, Short's mother received a letter of apology from her presumed-deceased husband, which revealed that he was in fact alive and had started a new life in

Short's body had been cut completely in half by a technique taught in the 1930s called a

Short's body had been cut completely in half by a technique taught in the 1930s called a

According to newspaper reports shortly after the murder, Short received the nickname "Black Dahlia" from staff and patrons at a Long Beach drugstore in mid-1946 as wordplay on the film '' The Blue Dahlia'' (1946). Other popularly-circulated rumors claim that the media crafted the name because Short adorned her hair with

According to newspaper reports shortly after the murder, Short received the nickname "Black Dahlia" from staff and patrons at a Long Beach drugstore in mid-1946 as wordplay on the film '' The Blue Dahlia'' (1946). Other popularly-circulated rumors claim that the media crafted the name because Short adorned her hair with

BlackDahlia.info. including a Chicago police officer who was a suspect in the case; FBI files on the case also contain a statement from one of Short's alleged lovers. Short's autopsy itself, which was reprinted in full in Michael Newton's 2009 book ''The Encyclopedia of Unsolved Crimes'', notes that her

Short is interred at the Mountain View Cemetery in

Short is interred at the Mountain View Cemetery in

The Black Dahlia

– FBI

The Black Dahlia case files

from the

''Somebody Knows'' episode

a 1950 radio program on the case * {{DEFAULTSORT:Black Dahlia 1924 births 1947 deaths People murdered in 1947 20th-century American people 20th-century American women American murder victims American women civilians in World War II Burials at Mountain View Cemetery (Oakland, California) Crimes in Los Angeles Deaths by beating in the United States Deaths from bleeding Female murder victims in the United States People from Hyde Park, Boston People from Medford, Massachusetts People murdered in Los Angeles Restaurant staff Retail clerks Unsolved murders in California Vandenberg Space Force Base

Leimert Park

Leimert Park (; ) is a neighborhood in the South Los Angeles region of Los Angeles, California.

Developed in the 1920s as a mainly residential community, it features Spanish Colonial Revival homes and tree-lined streets. The Life Magazine/Leim ...

neighborhood of Los Angeles

Los Angeles, often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, most populous city in the U.S. state of California, and the commercial, Financial District, Los Angeles, financial, and Culture of Los Angeles, ...

, California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

, on January 15, 1947. Her case became highly publicized owing to the gruesome nature of the crime, which included the mutilation and bisection of her corpse.

A native of Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

, Short spent her early life in New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

and Florida

Florida ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders the Gulf of Mexico to the west, Alabama to the northwest, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the north, the Atlantic ...

before relocating to California, where her father lived. It is commonly held that she was an aspiring actress, though she had no known acting credits or jobs during her time in Los Angeles. Short acquired the nickname of the Black Dahlia posthumously, as newspapers of the period often nicknamed particularly lurid crimes; the term may have originated from the film noir

Film noir (; ) is a style of Cinema of the United States, Hollywood Crime film, crime dramas that emphasizes cynicism (contemporary), cynical attitudes and motivations. The 1940s and 1950s are generally regarded as the "classic period" of Ameri ...

thriller '' The Blue Dahlia'' (1946). After the discovery of her body, the Los Angeles Police Department

The City of Los Angeles Police Department, commonly referred to as Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD), is the primary law enforcement agency of Los Angeles, California, United States. With 8,832 officers and 3,000 civilian staff, it is the th ...

(LAPD) began an extensive investigation that produced over 150 suspects but yielded no arrests.

Short's unsolved murder and the details surrounding it have had a lasting cultural impact, generating various theories and public speculation. Her life and death have been the basis of numerous books and films, and her murder is frequently cited as one of the most famous unsolved murders in U.S. history, as well as one of the oldest unsolved cases in Los Angeles County

Los Angeles County, officially the County of Los Angeles and sometimes abbreviated as LA County, is the most populous county in the United States, with 9,663,345 residents estimated in 2023. Its population is greater than that of 40 individua ...

. It has likewise been credited by historians as one of the first major crimes in postwar

A post-war or postwar period is the interval immediately following the end of a war. The term usually refers to a varying period of time after World War II, which ended in 1945. A post-war period can become an interwar period or interbellum, ...

America to capture national attention.

Life

Childhood

Elizabeth Short was born on July 29, 1924, in the Hyde Park neighborhood ofBoston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

, Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

, the third of five daughters to Cleo Alvin Short Jr. (October 18, 1885 – January 19, 1967) and his wife, Phoebe May Sawyer (July 2, 1897 – March 1, 1992). Her sisters were Virginia May West (born 1920), Dorothea Schloesser (born 1922), Elnora Chalmers (born 1925) and Muriel Short (born 1929). Short's father was a United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

sailor from Gloucester Courthouse, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

, while her mother was a native of Milbridge, Maine

Maine ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the United States, and the northeasternmost state in the Contiguous United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and ...

. The Shorts were married in Portland, Maine

Portland is the List of municipalities in Maine, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maine and the county seat, seat of Cumberland County, Maine, Cumberland County. Portland's population was 68,408 at the 2020 census. The Portland metropolit ...

, in 1918. The Short family briefly relocated to Portland in 1927, before settling in Medford, Massachusetts

Medford is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. At the time of the 2020 United States census, Medford's population was 59,659. It is home to Tufts University, which has its campus on both sides of the Medford and Somervill ...

, a suburb of Boston, that same year.

Short's father built miniature golf courses until he lost most of his savings in the 1929 stock market crash. In 1930, his car was found abandoned on the Charlestown Bridge

The Charlestown Bridge, officially named the William Felton "Bill" Russell Bridge, is located in Boston, Massachusetts, Boston and spans the Charles River. As the river's easternmost crossing, the bridge connects the neighborhoods of Charlesto ...

, and it was assumed that he had jumped into the Charles River

The Charles River (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ), sometimes called the River Charles or simply the Charles, is an river in eastern Massachusetts. It flows northeast from Hopkinton, Massachusetts, Hopkinton to Boston along a highly me ...

. Believing her husband to be deceased, Short's mother began working as a bookkeeper to support the family. Troubled by bronchitis

Bronchitis is inflammation of the bronchi (large and medium-sized airways) in the lungs that causes coughing. Bronchitis usually begins as an infection in the nose, ears, throat, or sinuses. The infection then makes its way down to the bronchi. ...

and severe asthma

Asthma is a common long-term inflammatory disease of the airways of the lungs. It is characterized by variable and recurring symptoms, reversible airflow obstruction, and easily triggered bronchospasms. Symptoms include episodes of wh ...

attacks, Short underwent lung surgery at age 15, after which doctors suggested she periodically relocate to a milder climate to prevent further respiratory problems. Her mother sent her to spend winters with family friends in Miami

Miami is a East Coast of the United States, coastal city in the U.S. state of Florida and the county seat of Miami-Dade County, Florida, Miami-Dade County in South Florida. It is the core of the Miami metropolitan area, which, with a populat ...

, Florida

Florida ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders the Gulf of Mexico to the west, Alabama to the northwest, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the north, the Atlantic ...

, for the next three years. Short dropped out of Medford High School during her sophomore

In the United States, a sophomore ( or ) is a person in the second year at an educational institution; usually at a secondary school or at the college and university level, but also in other forms of Post-secondary school, post-secondary educatio ...

year.

Relocation to California

In late 1942, Short's mother received a letter of apology from her presumed-deceased husband, which revealed that he was in fact alive and had started a new life in

In late 1942, Short's mother received a letter of apology from her presumed-deceased husband, which revealed that he was in fact alive and had started a new life in California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

. In December of that year, at age 18, Short relocated to Vallejo, California

Vallejo ( ; ) is a city in Solano County, California, United States, and the second largest city in the North Bay (San Francisco Bay Area), North Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area, Bay Area. Located on the shores of San Pablo Bay, the ci ...

, to live with her father, whom she had not seen since age 6. At the time her father was working at the nearby Mare Island Naval Shipyard

The Mare Island Naval Shipyard (MINSY or MINS) was the first United States Navy base established on the Pacific Ocean and was in service 142 years from 1854 to 1996. It is located on Mare Island, northeast of San Francisco, in Vallejo, Califor ...

on San Francisco Bay

San Francisco Bay (Chochenyo language, Chochenyo: 'ommu) is a large tidal estuary in the United States, U.S. state of California, and gives its name to the San Francisco Bay Area. It is dominated by the cities of San Francisco, California, San ...

. Arguments between Short and her father led to her moving out in January 1943.

Short took a job at the Base Exchange

An exchange is a type of retail store found on United States military installations worldwide. Once similar to trading posts, today they resemble modern department stores or strip malls. The terminology varies by armed service; some examples inc ...

at Camp Cooke (now Vandenberg Space Force Base

Vandenberg Space Force Base , previously Vandenberg Air Force Base, is a United States Space Force Base in Santa Barbara County, California. Established in 1941, Vandenberg Space Force Base is a space launch base, launching spacecraft from the ...

) near Lompoc, California

Lompoc ( ; Chumashan ) is a city in Santa Barbara County, California, United States. Located on the Central Coast, its population was 43,834 as of July 2021.

Lompoc has been inhabited for thousands of years by the Chumash people, who called t ...

, briefly living with a United States Army Air Force

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

sergeant who reportedly abused her. She left Lompoc in mid-1943 and moved to Santa Barbara, where she was arrested on September 23 for drinking at a local bar while underage. Juvenile authorities sent her back to Massachusetts, but she returned instead to Florida, making only occasional visits to her family near Boston.

While in Florida, Short met Major Matthew Michael Gordon Jr., a decorated Army Air Force officer of the 2nd Air Commando Group

The 352nd Special Operations Wing is an operational unit of the United States Air Force Special Operations Command currently stationed at RAF Mildenhall, United Kingdom. The unit's heritage dates back to 1944 as an air commando unit.

The 352 ...

, who was training for deployment to Southeast Asian theater of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. Short later told friends that Gordon had written to propose marriage while he was recovering from injuries from a plane crash in India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

. She accepted his offer, but Gordon died in a second crash on August 10, 1945. Short's sister Dorothea also served in the war and was assigned to decode Japanese messages.

In July 1946, Short relocated to Los Angeles

Los Angeles, often referred to by its initials L.A., is the List of municipalities in California, most populous city in the U.S. state of California, and the commercial, Financial District, Los Angeles, financial, and Culture of Los Angeles, ...

to visit Army Air Force Lieutenant Joseph Gordon Fickling, an acquaintance from Florida, who was stationed at the Naval Reserve Air Base in Long Beach

Long Beach is a coastal city in southeastern Los Angeles County, California, United States. It is the list of United States cities by population, 44th-most populous city in the United States, with a population of 451,307 as of 2022. A charter ci ...

. Short spent the last six months of her life in southern California

Southern California (commonly shortened to SoCal) is a geographic and Cultural area, cultural List of regions of California, region that generally comprises the southern portion of the U.S. state of California. Its densely populated coastal reg ...

, mostly in the Los Angeles area; shortly before her death she had been working as a waitress and rented a room behind the Florentine Gardens nightclub on Hollywood Boulevard

Hollywood Boulevard is a major east–west street in Los Angeles, California. It runs through the Hollywood, East Hollywood, Little Armenia, Thai Town, and Los Feliz districts. Its western terminus is at Sunset Plaza Drive in the Hollyw ...

. Short has been variously described and depicted as an aspiring or "would-be" actress. According to some sources, she did in fact have aspirations to be a film star, though she had no known acting jobs or credits.

Murder

Prior activities

On January 9, 1947, Short returned to her home in Los Angeles after a brief trip toSan Diego

San Diego ( , ) is a city on the Pacific coast of Southern California, adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a population of over 1.4 million, it is the List of United States cities by population, eighth-most populous city in t ...

with Robert "Red" Manley, a 25-year-old married salesman she had been dating. Manley stated that he dropped Short off at the Biltmore Hotel

Bowman-Biltmore Hotels was a hotel chain created by the hotel magnate John McEntee Bowman.

The name evokes the Vanderbilt family's Biltmore Estate, whose buildings and the gardens within are privately owned historical landmarks and tourist attra ...

in downtown Los Angeles

Downtown Los Angeles (DTLA) is the central business district of the city of Los Angeles. It is part of the Central Los Angeles region and covers a area. As of 2020, it contains over 500,000 jobs and has a population of roughly 85,000 residents ...

, and that Short was to meet one of her sisters, who was visiting from Boston, that afternoon. By some accounts, staff of the Biltmore recalled having seen Short using the lobby telephone. Shortly after, she was allegedly seen by patrons of the Crown Grill Cocktail Lounge at 754 South Olive Street, approximately away from the Biltmore.

Discovery

On the morning of January 15, 1947, Short's naked body, severed into two pieces, was found in a vacant lot on the west side of South Norton Avenue, midway between Coliseum Street and West 39th Street (at ) in the neighborhood ofLeimert Park

Leimert Park (; ) is a neighborhood in the South Los Angeles region of Los Angeles, California.

Developed in the 1920s as a mainly residential community, it features Spanish Colonial Revival homes and tree-lined streets. The Life Magazine/Leim ...

, which was largely undeveloped at the time.

Short's severely mutilated

Mutilation or maiming (from the ) is severe damage to the body that has a subsequent harmful effect on an individual's quality of life.

In the modern era, the term has an overwhelmingly negative connotation, referring to alterations that rend ...

body was completely severed at the waist and drained of blood, leaving her skin a pallid white. Medical examiner

The medical examiner is an appointed official in some American jurisdictions who is trained in pathology and investigates deaths that occur under unusual or suspicious circumstances, to perform post-mortem examinations, and in some jurisdicti ...

s determined that she had been dead for around ten hours prior to the discovery, leaving her time of death either sometime during the evening of January 14 or the early morning hours of January 15. The body had apparently been washed by the killer. Short's face had been slashed from the corners of her mouth to her ears, creating an effect known as the "Glasgow smile

A Glasgow smile (also known as a Chelsea grin/smile, or a Glasgow, Smiley, Huyton, A buck 50, forced smile or Cheshire grin) is a wound caused by making a cut from the corners of a victim's mouth up to the ears, leaving a scar in the shape o ...

". She had several cuts on her thigh and breasts, where entire portions of flesh had been sliced away. The lower half of her body was positioned a foot away from the upper, and her intestines

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The tract is the largest of the body's systems, after the cardiovascular system. ...

had been tucked neatly beneath her buttocks. The corpse had been "posed", with her hands over her head, her elbows bent at right angles, and her legs spread apart.

'' Los Angeles Herald-Express'' reporter Aggie Underwood was among the first to arrive at the crime scene, and took several photos of Short's body and its surroundings. Near the body, detectives located a heel print on the ground amid the tire tracks, and a cement sack containing watery blood was also found nearby.

Autopsy and identification

Anautopsy

An autopsy (also referred to as post-mortem examination, obduction, necropsy, or autopsia cadaverum) is a surgical procedure that consists of a thorough examination of a corpse by dissection to determine the cause, mode, and manner of deat ...

of Short's body was performed on January 16, 1947, by Frederick Newbarr, the Los Angeles County

Los Angeles County, officially the County of Los Angeles and sometimes abbreviated as LA County, is the most populous county in the United States, with 9,663,345 residents estimated in 2023. Its population is greater than that of 40 individua ...

coroner

A coroner is a government or judicial official who is empowered to conduct or order an inquest into the manner or cause of death. The official may also investigate or confirm the identity of an unknown person who has been found dead within th ...

. Newbarr's autopsy report stated that Short was tall, weighed and had light blue eyes, brown hair and badly decayed teeth. There were ligature marks on her ankles, wrists and neck, and an "irregular laceration

A wound is any disruption of or damage to living tissue, such as skin, mucous membranes, or organs. Wounds can either be the sudden result of direct trauma (mechanical, thermal, chemical), or can develop slowly over time due to underlying diseas ...

with superficial tissue loss" on her right breast. Newbarr also noted superficial lacerations on the right forearm, left upper arm and the lower left side of the chest.

Short's body had been cut completely in half by a technique taught in the 1930s called a

Short's body had been cut completely in half by a technique taught in the 1930s called a hemicorporectomy

Hemicorporectomy is a radical surgery in which the body below the waist is amputated, transecting the lumbar spine. This removes the legs, the genitalia (internal and external), urinary system, pelvic bones, anus, and rectum. It is a major proced ...

. The lower half of her body had been removed by transecting the lumbar spine between the second and third lumbar vertebrae

The lumbar vertebrae are located between the thoracic vertebrae and pelvis. They form the lower part of the back in humans, and the tail end of the back in quadrupeds. In humans, there are five lumbar vertebrae. The term is used to describe t ...

, thus severing the intestine at the duodenum

The duodenum is the first section of the small intestine in most vertebrates, including mammals, reptiles, and birds. In mammals, it may be the principal site for iron absorption.

The duodenum precedes the jejunum and ileum and is the shortest p ...

. Newbarr's report noted "very little" ecchymosis

A bruise, also known as a contusion, is a type of hematoma of tissue, the most common cause being capillaries damaged by trauma, causing localized bleeding that extravasates into the surrounding interstitial tissues. Most bruises occur clo ...

(bruising) along the incision line, suggesting it had been performed after death. Another "gaping laceration" measuring long ran longitudinally from the umbilicus

Umbilicus may refer to:

*The navel or belly button

*Umbilicus (mollusc), a feature of gastropod, Nautilus and Ammonite shell anatomy

*Umbilicus (plant), ''Umbilicus'' (plant), a genus of over ninety species of perennial flowering plants

*Umbilicus ...

to the suprapubic region

The hypogastrium (also called the hypogastric region or suprapubic region) is a region of the abdomen located below the umbilical region.

Etymology

The roots of the word ''hypogastrium'' mean "below the stomach"; the roots of ''suprapubic'' me ...

. The lacerations on each side of the face, which extended from the corners of the lips, were measured at on the right side of the face, and on the left. The skull was not fractured, but there was bruising noted on the front and right side of her scalp, with a small amount of bleeding in the subarachnoid space on the right side, consistent with blows to the head. The cause of death was determined to be hemorrhaging

Bleeding, hemorrhage, haemorrhage or blood loss, is blood escaping from the circulatory system from damaged blood vessels. Bleeding can occur internally, or externally either through a natural opening such as the mouth, nose, ear, urethra, ...

from the lacerations to her face and the shock from blows to the head and face. Newbarr noted that Short's anal canal was dilated at , suggesting that she might have been rape

Rape is a type of sexual assault involving sexual intercourse, or other forms of sexual penetration, carried out against a person without consent. The act may be carried out by physical force, coercion, abuse of authority, or against a person ...

d. Samples were taken from her body testing for the presence of sperm, but the results came back negative.

Short was identified after her fingerprints were sent to the Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic Intelligence agency, intelligence and Security agency, security service of the United States and Federal law enforcement in the United States, its principal federal law enforcement ag ...

(FBI); her fingerprints were on file from her 1943 arrest. Immediately following the identification, reporters from William Randolph Hearst

William Randolph Hearst (; April 29, 1863 – August 14, 1951) was an American newspaper publisher and politician who developed the nation's largest newspaper chain and media company, Hearst Communications. His extravagant methods of yellow jou ...

's ''Los Angeles Examiner

The ''Los Angeles Examiner'' was a newspaper founded in 1903 by William Randolph Hearst in Los Angeles. The afternoon '' Los Angeles Herald-Express'' and the morning ''Los Angeles Examiner'', both of which had been publishing in the city since t ...

'' contacted her mother, Phoebe Short, in Boston, and told her that her daughter had won a beauty contest. It was only after prying as much personal information as they could from Phoebe that the reporters revealed that her daughter had in fact been murdered. The ''Examiner'' also offered to pay Phoebe's airfare and accommodations if she would travel to Los Angeles to help with the police investigation; that was yet another ploy since the newspaper kept her away from police and other reporters to protect its scoop

Scoop, Scoops or The Scoop may refer to:

Artefacts

* Scoop (machine part), a component of machinery to carry things

* Scoop (tool), a shovel-like tool, particularly one deep and curved, used in digging

* Scoop (theater), a type of wide area l ...

. The ''Examiner'' and another Hearst newspaper, the ''Herald-Express'', later sensationalized

In journalism and mass media, sensationalism is a type of editorial tactic. Events and topics in news stories are selected and worded to excite the greatest number of readers and viewers. This style of news reporting encourages biased or emotiona ...

the case, with one ''Examiner'' article describing the black tailored suit Short was last seen wearing as "a tight skirt and a sheer blouse." The media nicknamed her the "Black Dahlia", and described her as an "adventuress" who "prowled Hollywood Boulevard." Additional newspaper reports, such as one published in the ''Los Angeles Times

The ''Los Angeles Times'' is an American Newspaper#Daily, daily newspaper that began publishing in Los Angeles, California, in 1881. Based in the Greater Los Angeles city of El Segundo, California, El Segundo since 2018, it is the List of new ...

'' on January 17, deemed the murder a "sex fiend slaying."

Investigation

Initial investigation

Letters and interviews

On January 21, a person claiming to be Short's killer placed a phone call to the office of James Richardson, the editor of the ''Examiner'', congratulating Richardson on the newspaper's coverage of the case and stating he planned on eventually turning himself in, but not before allowing police to pursue him further. Additionally, the caller told Richardson to "expect some souvenirs of Beth Short in the mail". Three days later, a suspicious manila envelope was discovered, addressed to "The ''Los Angeles Examiner'' and other Los Angeles papers", with individual words that had been cut-and-pasted from newspaper clippings; additionally, a large message on the face of the envelope read: "Here is Dahlia's belongings letter to follow." The envelope contained Short's birth certificate, business cards, photographs, names written on pieces of paper and an address book with the name Mark Hansen embossed on the cover. The packet had been carefully cleaned with gasoline, similarly to Short's body, which led police to suspect the packet had been sent directly by her killer. Despite efforts to clean the packet, several partial fingerprints were lifted from the envelope and sent to the FBI for testing; however, the prints were compromised in transit and thus could not be properly analyzed. The same day the packet was received by the ''Examiner'', a handbag and a black suede shoe were reported to have been seen on top of a garbage can in an alley a short distance from Norton Avenue, from the crime scene. The items were recovered by police but had also been wiped clean with gasoline, destroying any fingerprints. On March 14, an apparentsuicide note

A suicide note or death note is a message written by a person who intends to die by suicide.

A study examining Japanese suicide notes estimated that 25–30% of suicides are accompanied by a note. However, incidence rates may depend on ethnic ...

scrawled in pencil on a bit of paper was found tucked in a shoe in a pile of men's clothing by the ocean's edge at the foot of Breeze Avenue in Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

. The note read: "To whom it may concern: I have waited for the police to capture me for the Black Dahlia killing, but have not. I am too much of a coward to turn myself in, so this is the best way out for me. I couldn't help myself for that, or this. Sorry, Mary." The pile of clothing was first seen by a beach caretaker, who reported the discovery to lifeguard captain John Dillon. Dillon immediately notified Captain L. E. Christensen of West Los Angeles

West Los Angeles is an area within the city of Los Angeles, California, United States. The residential and commercial neighborhood is divided by the Interstate 405 freeway, and each side is sometimes treated as a distinct neighborhood, mapped ...

police station. The clothes included a coat and trousers of blue herringbone tweed, a brown and white T-shirt, white jockey shorts, tan socks and tan moccasin leisure shoes, size about eight. The clothes gave no clue about the identity of their owner.

Police quickly deemed Mark Hansen, the owner of the address book found in the packet, a suspect. Hansen was a wealthy local nightclub and theater owner and an acquaintance at whose home Short had stayed with friends. According to some sources, Hansen also confirmed that the purse and shoe discovered in the alley were in fact Short's. Ann Toth Ann (Anna Dolores) Toth (1922–1991) was a Hollywood starlet and girlfriend of Mark Hansen who operated the Florentine Gardens in Hollywood. She befriended and roomed at the Carlos Avenue, Hollywood residence with Elizabeth Short, prior to Short's ...

, Short's friend and roommate, told investigators that Short had recently rejected sexual advances from Hansen, and suggested it as potential motive for him to kill her; however, Hansen was cleared of suspicion in the case. In addition to Hansen, the Los Angeles Police Department

The City of Los Angeles Police Department, commonly referred to as Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD), is the primary law enforcement agency of Los Angeles, California, United States. With 8,832 officers and 3,000 civilian staff, it is the th ...

(LAPD) interviewed over 150 men in the ensuing weeks who they believed to be potential suspects. Robert Manley, who had been one of the last people to see Short alive, was also investigated, but was cleared of suspicion after passing numerous polygraph

A polygraph, often incorrectly referred to as a lie detector test, is a pseudoscientific device or procedure that measures and records several physiological indicators such as blood pressure, pulse, respiration, and skin conductivity while a ...

examinations. Police also interviewed several persons found listed in Hansen's address book, including Martin Lewis, who had been an acquaintance of Short's. Lewis was able to provide an alibi

An alibi (, from the Latin, '' alibī'', meaning "somewhere else") is a statement by a person under suspicion in a crime that they were in a different place when the offence was committed. During a police investigation, all suspects are usually a ...

for the date of Short's murder, as he was in Portland

Portland most commonly refers to:

*Portland, Oregon, the most populous city in the U.S. state of Oregon

*Portland, Maine, the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maine

*Isle of Portland, a tied island in the English Channel

Portland may also r ...

, Oregon

Oregon ( , ) is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is a part of the Western U.S., with the Columbia River delineating much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while t ...

, visiting his dying father-in-law.

A total of 750 investigators from the LAPD and other departments worked on the Short case during its initial stages, including 400 sheriff's deputies and 250 California State Patrol officers. Various locations were searched for potential evidence, including storm drains throughout Los Angeles, abandoned structures and various sites along the Los Angeles River

The Los Angeles River (), historically known as by the Tongva and the by the Spanish, is a major river in Los Angeles County, California. Its headwaters are in the Simi Hills and Santa Susana Mountains, and it flows nearly from Canoga Park ...

, but the searches yielded no further evidence. Los Angeles City Council

The Los Angeles City Council is the Legislature, lawmaking body for the Government of Los Angeles, city government of Los Angeles, California, the second largest city in the United States. It has 15 members who each represent the 15 city council ...

man Lloyd G. Davis posted a reward for information leading police to Short's killer. After the announcement of the reward, various persons came forward with confessions, most of which police dismissed as false. Several of the false confessors were charged with obstruction of justice

In United States jurisdictions, obstruction of justice refers to a number of offenses that involve unduly influencing, impeding, or otherwise interfering with the justice system, especially the legal and procedural tasks of prosecutors, investiga ...

.

Media response; decline

On January 26, another letter was received by the ''Examiner'', this time handwritten, which read: "Here it is. Turning in Wed., Jan. 29, 10 am. Had my fun at police. Black Dahlia Avenger." The letter also named a location at which the supposed killer would turn himself in. Police waited at the location on the morning of January 29, but the alleged killer did not appear. Instead, at 1:00pm, the ''Examiner'' offices received another cut-and-pasted letter which read: "Have changed my mind. You would not give me a square deal. Dahlia killing was justified." The graphic nature of the murder and the subsequent letters received by the ''Examiner'' had resulted in amedia circus

Media circus is a colloquial metaphor or idiom describing a news event for which the level of media coverage—measured by such factors as the number of reporters at the scene and the amount of material broadcast or published—is perceived to b ...

surrounding Short's murder. Both local and national publications heavily covered the story, many of which reprinted sensationalistic reports suggesting that Short had been tortured for hours prior to her death; the information, however, was false, yet police allowed the reports to circulate so as to conceal Short's true cause of death—cerebral hemorrhage

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), also known as hemorrhagic stroke, is a sudden bleeding into the tissues of the brain (i.e. the parenchyma), into its ventricles, or into both. An ICH is a type of bleeding within the skull and one kind of stro ...

—from the public. Further reports about Short's personal life were publicized, including details about her alleged declining of Hansen's sexual advances; additionally, a stripper

A stripper or exotic dancer is a person whose occupation involves performing striptease in a public adult entertainment venue such as a strip club. At times, a stripper may be hired to perform at private events.

Modern forms of stripping m ...

who was an acquaintance of Short's told police that she "liked to get guys worked up over her, but she'd leave them hanging dry." This led some reporters (namely the ''Herald-Express''s Bevo Means) and detectives to look into the possibility that Short was a lesbian

A lesbian is a homosexual woman or girl. The word is also used for women in relation to their sexual identity or sexual behavior, regardless of sexual orientation, or as an adjective to characterize or associate nouns with female homosexu ...

, and begin questioning employees and patrons of gay bar

A gay bar is a Bar (establishment), drinking establishment that caters to an exclusively or predominantly lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender or queer (LGBTQ+) clientele; the term ''gay'' is used as a broadly inclusive concept for LGBTQ+ communi ...

s in Los Angeles; this claim, however, remained unsubstantiated. The ''Herald-Express'' also received several letters from the purported killer, again made with cut-and-pasted clippings, one of which read: "I will give up on Dahlia killing if I get 10 years. Don't try to find me."

On February 1, the ''Los Angeles Daily News

The ''Los Angeles Daily News'' is the second-largest-circulating paid daily newspaper of Los Angeles, California, after the unrelated ''Los Angeles Times'', and the flagship newspaper of the Southern California News Group, a branch of Colorado ...

'' reported that the case had "run into a Stone Wall", with no new leads for investigators to pursue. The ''Examiner'' continued to run stories on the murder and the investigation, which was front-page news for thirty-five days following the discovery of the body.

When interviewed, lead investigator Captain Jack Donahue told the press that he believed Short's murder had taken place in a remote building or shack on the outskirts of Los Angeles, and that her body was transported to the location where it was disposed of. Based on the precise cuts and dissection of Short's body, the LAPD looked into the possibility that the murderer had been a surgeon, doctor or someone with medical knowledge. In mid-February 1947, the LAPD served a warrant to the University of Southern California Medical School

The USC Keck School of Medicine is the medical school of the University of Southern California. The school teaches and trains physicians, biomedical scientists and other healthcare professionals, conducts medical research, and treats patients. F ...

, which was located near the site where the body had been discovered, requesting a complete list of the program's students. The university agreed so long as the students' identities remained private. Background checks were conducted but yielded no results.

Grand jury and aftermath

By the spring of 1947, Short's murder had become acold case

''Cold Case'' is an American police procedural crime drama television series. It ran on CBS from September 28, 2003, to May 2, 2010. The series revolved around a fictionalized Philadelphia Police Department division that specializes in invest ...

with few new leads. Sergeant Finis Brown, one of the lead detectives on the case, blamed the press for compromising the investigation through journalists' probing of details and unverified reporting. In September 1949, a grand jury

A grand jury is a jury empowered by law to conduct legal proceedings, investigate potential criminal conduct, and determine whether criminal charges should be brought. A grand jury may subpoena physical evidence or a person to testify. A grand ju ...

convened to discuss inadequacies in the LAPD's homicide unit based on their failure to solve numerous murders—especially those of women and children—in the previous several years, Short's being one of them. In the aftermath of the grand jury, further investigation was done on Short's past, with detectives tracing her movements between Massachusetts, California and Florida, and also interviewed people who knew Short in Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

and New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

. However, the interviews yielded no useful information in the murder.

Suspects and confessions

The notoriety of Short's murder has spurred a large number of confessions over the years, many of which have been deemed false. During the initial investigation, police received a total of sixty confessions, most made by men. Since that time, over 500 people have confessed to the crime, some of whom had not even been born at the time of her death. Sergeant John P. St. John, an LAPD detective who worked the case until his retirement, stated, "It is amazing how many people offer up a relative as the killer." In 2003, Ralph Asdel, one of the original detectives on the case, told the ''Times'' that he believed he had interviewed Short's killer, a man who had been seen with his sedan parked near the crime scene in the early morning hours of January 15, 1947. A neighbor driving by that day stopped to dispose of a bag of lawn clippings in the lot when he saw a parked sedan, allegedly with its right rear door open; the driver of the sedan was standing in the lot. His arrival apparently startled the owner of the sedan, who approached his car and peered in the window before returning to the sedan and driving away. The owner of the sedan was followed to a local restaurant where he worked, but was ultimately cleared of suspicion. Suspects remaining under discussion by various authors and experts include a doctor named Walter Bayley, proposed by former ''Times'' copyeditor Larry Harnisch; ''Times'' publisherNorman Chandler

Norman Chandler (September 14, 1899 – October 20, 1973) was the publisher of the ''Los Angeles Times'' from 1945 to 1960.

Personal

Norman Chandler was born in Los Angeles on September 14, 1899, one of eight children of Harry Chandler and M ...

, whom biographer Donald Wolfe claims impregnated Short; Leslie Dillon, Joseph A. Dumais, Artie Lane, Mark Hansen, Francis E. Sweeney, Woody Guthrie

Woodrow Wilson Guthrie (; July 14, 1912 – October 3, 1967) was an American singer, songwriter, and composer widely considered to be one of the most significant figures in American folk music. His work focused on themes of American Left, A ...

, Bugsy Siegel

Benjamin "Bugsy" Siegel (; February 28, 1906 – June 20, 1947) was an American gangster, mobster who was a driving force behind the development of the Las Vegas Strip. Siegel was influential within the Jewish-American organized crime, Jewish Mo ...

, Orson Welles

George Orson Welles (May 6, 1915 – October 10, 1985) was an American director, actor, writer, producer, and magician who is remembered for his innovative work in film, radio, and theatre. He is among the greatest and most influential film ...

, George Hodel

George Hill Hodel (October 10, 1907 – May 17, 1999) was an American physician, and a suspect in the murder of Elizabeth Short, the Black Dahlia. He was never formally charged with the crime but, at the time, police considered him a viable s ...

, Hodel's friend Fred Sexton, George Knowlton, Robert M. "Red" Manley, Patrick S. O'Reilly, and Jack Anderson Wilson.

Although he was never formally charged in the crime, George Hodel came to wider attention after his death when he was accused by his son, LAPD homicide detective Steve Hodel, of killing Short and committing several additional murders. Prior to the Dahlia case, George Hodel was suspected, but not charged, in the death of his secretary, Ruth Spaulding; and was accused of raping his own daughter, Tamar, but acquitted

In common law jurisdictions, an acquittal means that the criminal prosecution has failed to prove that the accused is guilty beyond a reasonable doubt of the charge presented. It certifies that the accused is free from the charge of an o ...

. Hodel fled the country several times and lived in the Philippines between 1950 and 1990. Additionally, Steve Hodel has cited his father's training as a surgeon as circumstantial evidence. In 2003, it was revealed in notes from the 1949 grand jury report that investigators had wiretapped

Wiretapping, also known as wire tapping or telephone tapping, is the Surveillance, monitoring of telephone and Internet-based conversations by a third party, often by covert means. The wire tap received its name because, historically, the monito ...

George Hodel's home and obtained recorded conversation of him with an unidentified visitor, saying: "Supposin' I did kill the Black Dahlia. They couldn't prove it now. They can't talk to my secretary because she's dead. They thought there was something fishy. Anyway, now they may have figured it out. Killed her. Maybe I did kill my secretary."

In 1991, Janice Knowlton, who was aged 10 at the time of Short's murder, claimed that she witnessed her father, George Knowlton, beat Short to death with a claw hammer

A claw hammer is a hammer primarily used in carpentry for driving nail (fastener), nails into or pulling them from wood. Historically, a claw hammer has been associated with woodworking, but is also used in general applications. It is not sui ...

in the detached garage of her family's home in Westminster

Westminster is the main settlement of the City of Westminster in Central London, Central London, England. It extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street and has many famous landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Buckingham Palace, ...

. She also published a book titled ''Daddy was the Black Dahlia Killer'' in 1995, in which she made additional claims that her father sexually abused

Sexual abuse or sex abuse is abusive sexual behavior by one person upon another. It is often perpetrated using physical force, or by taking advantage of another. It often consists of a persistent pattern of sexual assaults. The offender is r ...

her. The book was condemned as "trash" by Knowlton's stepsister, Jolane Emerson, who stated: "She believed it, but it wasn't reality. I know, because I lived with her father for sixteen years." Additionally, St. John told the ''Times'' that Knowlton's claims were "not consistent with the facts of the case."

The 2017 book ''Black Dahlia, Red Rose'' by Piu Eatwell focuses on Leslie Dillon, a bellhop

A bellhop (North America), or hotel porter (international), is a hotel employee who helps patrons with their luggage while checking in or out. Bellhops often wear a uniform, like certain other page boys or doormen. This occupation is also know ...

who was a former mortician's assistant; his associates Mark Hansen and Jeff Connors; and Sergeant Finis Brown, a lead detective who had links to Hansen and was allegedly corrupt

Corruption is a form of dishonesty or a criminal offense that is undertaken by a person or an organization that is entrusted in a position of authority to acquire illicit benefits or abuse power for one's gain. Corruption may involve activities ...

. Eatwell posits that Short was murdered because she knew too much about the men's involvement in a scheme for robbing hotels. She further suggests that Short was killed at the Aster Motel in Los Angeles, where the owners reported finding one of their rooms "covered in blood and fecal matter" on the morning Short's body was found. The ''Examiner'' stated in 1949 that LAPD chief William A. Worton denied that the Aster Motel had anything to do with the case, although its rival newspaper, the ''Los Angeles Herald

The ''Los Angeles Herald'' or the ''Evening Herald'' was a newspaper published in Los Angeles in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Founded in 1873 by Charles A. Storke, the newspaper was acquired by William Randolph Hearst in 1931. It ...

'', claimed that the murder took place there.

In 2000, Buz Williams, a retired detective with the Long Beach Police Department, wrote an article for the LBPD newsletter ''The Rap Sheet'' on Short's murder. His father, Richard F. Williams, was a member of the LAPD's Gangster Squad investigating the case. Williams' father reportedly believed that Dillon was the killer, and that when Dillon returned to his home state of Oklahoma

Oklahoma ( ; Choctaw language, Choctaw: , ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Texas to the south and west, Kansas to the north, Missouri to the northea ...

he was able to avoid extradition

In an extradition, one Jurisdiction (area), jurisdiction delivers a person Suspect, accused or Conviction, convicted of committing a crime in another jurisdiction, into the custody of the other's law enforcement. It is a cooperative law enforc ...

to California because his ex-wife Georgia Stevenson was second cousins with Illinois Governor

The governor of Illinois is the head of government of Illinois, and the various agencies and departments over which the officer has jurisdiction, as prescribed in the state constitution. It is a directly elected position, votes being cast by p ...

Adlai Stevenson II

Adlai Ewing Stevenson II (; February 5, 1900 – July 14, 1965) was an American politician and diplomat who was the United States ambassador to the United Nations from 1961 until his death in 1965. He previously served as the 31st governor of Ill ...

, who contacted the governor of Oklahoma

The governor of Oklahoma is the head of government of the U.S. state of Oklahoma. Under the Oklahoma Constitution, the governor serves as the head of the Oklahoma Executive (government), executive branch, of the government of Oklahoma. The gover ...

on Dillon's behalf. Williams' article claimed that Dillon sued the LAPD for $3 million, but that the suit was dropped. Harnisch disputes this, stating that Dillon was cleared by police after an exhaustive investigation and that the district attorney

In the United States, a district attorney (DA), county attorney, county prosecutor, state attorney, state's attorney, prosecuting attorney, commonwealth's attorney, or solicitor is the chief prosecutor or chief law enforcement officer represen ...

's files positively placed him in San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

when Short was killed. Harnisch claims that there was no LAPD coverup, and that Dillon did in fact receive a financial settlement from the City of Los Angeles, but has not produced concrete evidence to prove this.

Theories and potentially related crimes

Cleveland Torso Murders

Several crime authors, as well as police detective Peter Merylo, have suspected a link between the Short murder and the Cleveland Torso Murders, which took place inCleveland

Cleveland is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located along the southern shore of Lake Erie, it is situated across the Canada–U.S. maritime border and approximately west of the Ohio-Pennsylvania st ...

, Ohio

Ohio ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders Lake Erie to the north, Pennsylvania to the east, West Virginia to the southeast, Kentucky to the southwest, Indiana to the ...

, between 1934 and 1938. As part of their investigation into other murders that took place before and after the Short killing, the original LAPD investigators studied the Torso Murders in 1947 but later discounted any connection between the two cases. In 1980, new evidence implicating a former Torso Murder suspect, Jack Anderson Wilson, was investigated by St. John in relation to Short's murder. He claimed he was close to arresting Wilson in Short's murder, but that Wilson died in a fire on February 4, 1982. The possible connection to the Torso Murders received renewed media attention when it was profiled on the NBC

The National Broadcasting Company (NBC) is an American commercial broadcast television and radio network serving as the flagship property of the NBC Entertainment division of NBCUniversal, a subsidiary of Comcast. It is one of NBCUniversal's ...

series ''Unsolved Mysteries

''Unsolved Mysteries'' is an American mystery documentary television series, created by John Cosgrove and Terry Dunn Meurer. Documenting cold cases and paranormal phenomena, it began as a series of seven specials, presented by Raymond Burr, Kar ...

'' in 1992, in which Eliot Ness

Eliot Ness (April 19, 1903 – May 16, 1957) was an American Bureau of Prohibition, Prohibition agent known for his efforts to bring down Al Capone while enforcing Prohibition in the United States, Prohibition in Chicago. He was leader of a team ...

biographer Oscar Fraley

Oscar Fraley (August 2, 1914 – January 6, 1994) was an American sports writer and author, perhaps best known, with Eliot Ness, as the co-author of the American memoir ''The Untouchables''.

Early life

Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Fraley ...

suggested Ness knew the identity of the killer responsible for both cases.

Lipstick Murders

Crime authors such as Steve Hodel and William Rasmussen have suggested a link between the Short murder and the 1946 murder and dismemberment of 6-year-old Suzanne Degnan inChicago

Chicago is the List of municipalities in Illinois, most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of Unite ...

, Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. It borders on Lake Michigan to its northeast, the Mississippi River to its west, and the Wabash River, Wabash and Ohio River, Ohio rivers to its ...

. Captain Donahoe of the LAPD stated publicly that he believed the Black Dahlia and the "Lipstick Murders" in Chicago were "likely connected." Among the evidence cited is the fact that Short's body was found on Norton Avenue, three blocks west of Degnan Boulevard, Degnan being the last name of the girl from Chicago. There were also striking similarities between the handwriting on the Degnan ransom

Ransom refers to the practice of holding a prisoner or item to extort money or property to secure their release. It also refers to the sum of money paid by the other party to secure a captive's freedom.

When ransom means "payment", the word ...

note and that of the "Black Dahlia Avenger." Both texts used a combination of capitals and small letters (the Degnan note read in part "BuRN This FoR heR SAfTY" ), and both notes contain a similar misshapen letter P and have one word that matches exactly. Convicted serial killer

A serial killer (also called a serial murderer) is a person who murders three or more people,An offender can be anyone:

*

*

*

*

* (This source only requires two people) with the killings taking place over a significant period of time in separat ...

William Heirens

William George Heirens (November 15, 1928 – March 5, 2012) was an American criminal and serial killer who confessed to three murders. He was subsequently convicted of the crimes in 1946. Heirens was called the Lipstick Killer after a notorious ...

served life in prison for Degnan's murder. Initially arrested at age 17 for breaking into a residence close to that of Degnan, Heirens claimed he was torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a person for reasons including corporal punishment, punishment, forced confession, extracting a confession, interrogational torture, interrogation for information, or intimid ...

d by police, forced to confess and made a scapegoat

In the Bible, a scapegoat is one of a pair of kid goats that is released into the wilderness, taking with it all sins and impurities, while the other is sacrificed. The concept first appears in the Book of Leviticus, in which a goat is designate ...

for the murder. After being taken from the medical infirmary at the Dixon Correctional Center

The Dixon Correctional Center is a medium security adult male prison of the Illinois Department of Corrections in Dixon, Illinois

Dixon is a city in Lee County, Illinois, United States, and its county seat. The population was 15,274 as of th ...

on February 26, 2012, for health problems, Heirens died at the University of Illinois Medical Center

The University of Illinois Hospital & Health Sciences System (UI Health) is a member of the Illinois Medical District, one of the largest urban healthcare, educational, research, and technology districts in the USA. The University of Illinois Ho ...

on March 5, 2012, at age 83.

Lone Woman Murders

Between 1943 and 1949, over a dozen unsolved murders occurred in Los Angeles which involved thesexual mutilation

Genital modifications are forms of body modifications applied to the human sexual organs, including invasive modifications performed through genital cutting or surgery. The term genital enhancement seem to be generally used for genital modificat ...

of young attractive women. Authorities suspected at the time that they could have been the work of a single unidentified serial killer. In 1949, a Los Angeles County grand jury

A grand jury is a jury empowered by law to conduct legal proceedings, investigate potential criminal conduct, and determine whether criminal charges should be brought. A grand jury may subpoena physical evidence or a person to testify. A grand ju ...

was tasked with investigating the failure on the part of law enforcement to solve the cases. As a result, further investigation was done on the homicides although none of them were solved.

* On July 27, 1943, the son of a greenskeeper discovered the nude body of 41-year-old Ora Elizabeth Murray lying on the ground near the parking lot of the Fox Hills Golf Course. Murray had been severely beaten about her face and body, and the autopsy determined that her cause of death was due to "constriction of the larynx

The larynx (), commonly called the voice box, is an organ (anatomy), organ in the top of the neck involved in breathing, producing sound and protecting the trachea against food aspiration. The opening of larynx into pharynx known as the laryngeal ...

by strangulation". Murray was last seen on July 26, 1943, attending a dance at the Zenda Ballroom in downtown Los Angeles with her sister before leaving with an unidentified man. Her murder remains unsolved.

* John Gilmore John Gilmore may refer to:

* John Gilmore (activist) (born 1955), co-founder of the Electronic Frontier Foundation and Cygnus Solutions

* John Gilmore (musician) (1931–1995), American jazz saxophonist

* John Gilmore (representative) (1780–1845), ...

's 1994 book '' Severed: The True Story of the Black Dahlia Murder'', suggests a possible connection between Short's murder and that of 20-year-old Georgette Bauerdorf. At 11 a.m. on October 12, 1944, Bauerdorf's maid and a janitor arrived to clean her apartment in West Hollywood

West Hollywood is a city in Los Angeles County, California, United States. Incorporated in 1984, it is home to the Sunset Strip. As of the 2020 U.S. Census, its population was 35,757.

History

Most historical writings about West Hollywood be ...

where they found her body face down in her bathtub. It is believed that Bauerdorf was attacked by a man who was waiting inside the apartment for her. Gilmore suggests that Short's employment at the Hollywood Canteen

The Hollywood Canteen operated at 1451 North Cahuenga Boulevard in the Los Angeles, California, neighborhood of Hollywood between October 3, 1942 and November 22, 1945, as a club offering food, dancing, and entertainment for enlisted men and ...

, where Bauerdorf also worked as a hostess, could be a potential connection between the two women. However, the claim that Short ever worked at the Hollywood Canteen has been disputed by other sources, such as the retired ''Times'' copy-editor Larry Harnisch. Regardless, Steve Hodel has still suggested that both women were killed by the same individual since in both cases the media received notes supposedly from the killer taunting the police and boasting of his skills.

* The murder of 44-year-old Jeanne "Nettie" French on February 10, 1947, was also considered by the media and detectives as possibly being related to Short's killing. French's body was discovered in West Los Angeles on Grand View Boulevard, nude and badly beaten. Written on her stomach in lipstick was what appeared to say "Fuck You B.D." and the letters "TEX" below. The ''Herald-Express'' covered the story heavily and drew comparisons to the Short murder less than a month prior, surmising the initials "B.D." stood for "Black Dahlia". According to historian Jon Lewis, however, the scrawling actually read "P.D.", ostensibly standing for "police department."

* On March 12, 1947, the nude body of 43-year-old Evelyn Winters was found at 12:10 a.m. in a vacant lot of an abandoned rail yard in Norwalk, California

Norwalk is a city in Los Angeles County, California, United States. The population was 102,773 at the 2020 census.

Founded in the late 19th century, Norwalk was incorporated as a city in 1957. It is located southeast of downtown Los Angeles a ...

, along the Los Angeles River. Winters had been bludgeoned and strangled to death. She was last seen by a male acquaintance, James Joseph Tiernan, who stated to authorities that he saw her leave the Albany Hotel in Los Angeles at 8:00 p.m.

* Dorothy Ella Montgomery, aged 36, was found at about 10:30 a.m. in a vacant field on May 4, 1947, under a pepper tree Pepper tree is a common name for several trees, including:

* Those in the genus '' Schinus''

* ''Macropiper excelsum

''Piper excelsum'' (formerly known as ''Macropiper excelsum'') of the pepper family (Piperaceae) and commonly known as kawak ...

in Florence-Graham, California

Florence-Graham (also known as Florence-Firestone) is a census-designated place in Los Angeles County, California, United States. The population was 61,983 at the 2020 census, down from 63,387 at the 2010 census. The census area includes separa ...

. Montgomery had died due to strangulation and was found nude and beaten. She had been missing since 9:30 p.m. the previous evening when she had left her home to pick up her daughter at a dance recital.

* On May 12, 1947, the body of 39-year-old Laura Eliza Trelstad was discovered by an oil company patrolman in an oil field on Long Beach Boulevard. Trelstad had been sexually assaulted

Sexual assault is an act of sexual abuse in which one intentionally sexually touches another person without that person's consent, or coerces or physically forces a person to engage in a sexual act against their will. It is a form of sexua ...

, strangled with a belt and then thrown from a moving vehicle. According to her husband, they had both been playing cards the night prior at their home in 2211 Locust Avenue, Long Beach, with friends in the late afternoon. Trelstad's husband wanted to continue; but she had become bored and left to go to the Crystal Ballroom. She stated: "If the boys can play poker, we girls can go dance." She was not seen alive again.

* On July 8, 1947, the naked body of Rosenda Josephine Mondragon, aged 21, was discovered by a postal clerk in a gutter near Los Angeles City Hall

Los Angeles City Hall, completed in 1928, is the center of the government of the city of Los Angeles, California, and houses the Mayor of Los Angeles, mayor's office and the meeting chambers and offices of the Los Angeles City Council. It is loca ...

. Mondragon had been strangled by a silk stocking. She was last seen by her estranged husband that morning, at 1 a.m., when he had been served by her with divorce papers at his residence. She then left entering a stranger's car.

* On the evening of October 2, 1947, Lillian Dominguez, aged 15, was walking home with her sister and a friend in Santa Monica

Santa Monica (; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Santa Mónica'') is a city in Los Angeles County, California, Los Angeles County, situated along Santa Monica Bay on California's South Coast (California), South Coast. Santa Monica's 2020 United Sta ...

, when a man approached them and proceeded to stab Dominguez in the heart with a stiletto blade, between her second and third ribs. One week later, on October 9, a note on the back of a business card was left under the door of a furniture store. The message was written in pencil and read: "I killed the Santa Monica Girl, I will kill others."

* On February 14, 1948, 42-year-old Gladys Eugenia Kern, a Los Angeles real estate agent, was found stabbed in the back with a hunting knife in a vacant house that she was showing in the Los Feliz

LOS, or Los, or LoS may refer to:

Science and technology

* Length of stay, the duration of a single episode of hospitalisation

* Level of service, a measure used by traffic engineers

* Level of significance, a measure of statistical significanc ...

district at 4217 Cromwell Avenue. That afternoon Kern was last seen with an unidentified man at the counter of a nearby drugstore. The murderer had stolen her appointment book and had cleaned the murder weapon before he left.

* Cosmetologist

Cosmetology (from Greek , ''kosmētikos'', "beautifying"; and , ''-logia'') is the study and application of beauty treatment. Branches of specialty include hairstyling, skin care, cosmetics, manicures/ pedicures, non-permanent hair removal suc ...

Louise Margaret Springer, aged 35, was found murdered on June 13, 1949, in the backseat of her husband's convertible

A convertible or cabriolet () is a Car, passenger car that can be driven with or without a roof in place. The methods of retracting and storing the roof vary across eras and manufacturers.

A convertible car's design allows an open-air drivin ...

sedan alongside a street in South Central Los Angeles

South Los Angeles, also known as South Central Los Angeles or simply South Central, is a region in southwestern Los Angeles County, California, lying mostly within the city limits of Los Angeles, south of Downtown Los Angeles, downtown.

It is de ...

. She had been garrote

A garrote ( ; alternatively spelled as garotte and similar variants)''Oxford English Dictionary'', 11th Ed: garrotte is normal British English spelling, with single r alternate. Article title is US English spelling variant. or garrote vil () is ...

d with a length of clothesline that had been knotted and a stick had been inserted into her anus

In mammals, invertebrates and most fish, the anus (: anuses or ani; from Latin, 'ring' or 'circle') is the external body orifice at the ''exit'' end of the digestive tract (bowel), i.e. the opposite end from the mouth. Its function is to facil ...

. Springer's husband notified law enforcement of her disappearance that evening when he returned from an errand inside her shop to find both Springer and his vehicle missing.

* Mimi Boomhower, aged 48, was last heard from when she telephoned a friend from her home in the 700 block of Nimes Road in Los Angeles on August 18, 1949. Between 7:00 and 8:00 p.m., the call ended. Five days after she vanished, Boomhower's white handbag was discovered in a phonebooth at a grocery store in Los Angeles. Boomhower was never heard from again, and she was later declared legally dead

''Legally Dead'' is a 1923 American drama film directed by William Parke and written by Harvey Gates. The film stars Milton Sills, Margaret Campbell, Claire Adams, Eddie Sturgis, Faye O'Neill, and Charles A. Stevenson. The film was released o ...

.

* On the evening of October 7, 1949, 26-year-old Jean Spangler

Jean Elizabeth Spangler (September 2, 1923 – disappeared October 7, 1949) was an American actress who appeared in bit parts in several Hollywood films in the late 1940s. She garnered public attention for her mysterious disappearance in l ...

left her home in Los Angeles, telling her sister-in-law that she was going to meet with her ex-husband before going to work as an extra

Extra, Xtra, or The Extra may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media Film

* The Extra (1962 film), ''The Extra'' (1962 film), a Mexican film

* The Extra (2005 film), ''The Extra'' (2005 film), an Australian film

Literature

* Extra (newspaper), ...

on a film set. She was last seen alive at a grocery store several blocks from her home at approximately 6:00 p.m. Two days later, Spangler's tattered purse was discovered in a remote area of Griffith Park

Griffith Park is a large municipal park at the eastern end of the Santa Monica Mountains, in the Los Feliz neighborhood of Los Angeles, California. The park includes popular attractions such as the Los Angeles Zoo, the Autry Museum of the Amer ...

, approximately from her home; inside was a letter addressed to a "Kirk," which mentioned seeing a doctor.

Rumors and factual disputes

Numerous details regarding Short's personal life and death have been points of public dispute. The eager involvement of both the public and press in solving her murder have been credited as factors that complicated the investigation significantly, resulting in a complex, sometimes inconsistent narrative of events. According to Anne Marie DiStefano of the ''Portland Tribune

The ''Portland Tribune'' is a weekly newspaper published every Wednesday in Portland, Oregon, United States. It is part of the Pamplin Media Group, which publishes a number of community newspapers in the Portland metropolitan area. Launched i ...

'', many "unsubstantiated stories" have circulated about Short over the years: "She was a prostitute

Prostitution is a type of sex work that involves engaging in sexual activity in exchange for payment. The definition of "sexual activity" varies, and is often defined as an activity requiring physical contact (e.g., sexual intercourse, non-pe ...

, she was frigid, she was pregnant, she was a lesbian. And somehow, instead of fading away over time, the legend of the Black Dahlia just keeps getting more convoluted." Harnisch has refuted several supposed rumors and popular conceptions about Short and also disputed the validity of Gilmore's book ''Severed'', claiming the book is "25% mistakes, and 50% fiction." Harnisch had examined the district attorney's files (he claimed that Steve Hodel has examined some of them pertaining to his father, along with ''Times'' columnist Steve Lopez) and contrary to Eatwell's claims, the files showed that Dillon was thoroughly investigated and was determined to have been in San Francisco when Short was killed. Harnisch speculated that Eatwell either did not find these files or she chose to ignore them.

Murder and state of the body

A number of people, none of whom knew Short, contacted police and newspapers claiming to have seen her during her so-called "missing week," between her January 9 disappearance and the discovery of her body, on January 15. Police and district attorney's investigators ruled out each alleged sighting; in some cases, those interviewed were identifying other women whom they had mistaken for Short. Short's whereabouts in the days leading up to her murder and the discovery of her body are unknown. After the discovery of Short's body, numerous Los Angeles newspapers printed headlines claiming she had been tortured leading up to her death. This was denied by law enforcement at the time, but they allowed the claims to circulate so as to keep Short's actual cause of death a secret from the public. Some sources, such as Oliver Cyriax's ''Crime: An Encyclopedia'' (1993), state that Short's body was covered incigarette burns

Cigarette burns are usually deliberate injuries caused by pressing a lit cigarette or cigar to the skin. They are a common form of child abuse, self-harm, and torture

Torture is the deliberate infliction of severe pain or suffering on a p ...

inflicted on her while she was still alive, though there is no indication of this in her official autopsy report.

In ''Severed'', Gilmore states that the coroner who performed Short's autopsy suggested in conversation that she had been forced to consume feces

Feces (also known as faeces American and British English spelling differences#ae and oe, or fæces; : faex) are the solid or semi-solid remains of food that was not digested in the small intestine, and has been broken down by bacteria in the ...

based on his findings when examining the contents of her stomach. This claim has been denied by Harnisch and is also not indicated in Short's official autopsy, though it has been reprinted in several print and online media.

Nickname

According to newspaper reports shortly after the murder, Short received the nickname "Black Dahlia" from staff and patrons at a Long Beach drugstore in mid-1946 as wordplay on the film '' The Blue Dahlia'' (1946). Other popularly-circulated rumors claim that the media crafted the name because Short adorned her hair with

According to newspaper reports shortly after the murder, Short received the nickname "Black Dahlia" from staff and patrons at a Long Beach drugstore in mid-1946 as wordplay on the film '' The Blue Dahlia'' (1946). Other popularly-circulated rumors claim that the media crafted the name because Short adorned her hair with dahlia

''Dahlia'' ( , ) is a genus of bushy, tuberous, herbaceous perennial plants native to Mexico and Central America. Dahlias are members of the Asteraceae (synonym name: Compositae) family of dicotyledonous plants, its relatives include the sun ...

s. According to the FBI's official website, Short received the first part of the nickname from the press "for her rumored penchant for sheer black clothes."

However, reports by district attorney's investigators state that the nickname was invented by newspaper reporters covering her murder; ''Herald-Express'' reporter Bevo Means, who interviewed Short's acquaintances at the drugstore, has been credited with first using the "Black Dahlia" name, though reporters Underwood and Jack Smith have been alternatively named as its creators. While some sources claim that Short was referred to or went by the name during her life, others dispute this. Both Gilmore and Harnisch agree that the name originated during Short's lifetime and was not a creation of the press: Harnisch states that it was in fact a nickname she earned from the staff of the Long Beach drugstore she frequented; in ''Severed'', Gilmore names an A.L. Landers as the proprietor of the drugstore, though he does not provide the store's name. Prior to the circulation of the "Black Dahlia" name, Short's killing had been dubbed the "Werewolf Murder" by the ''Herald-Express'' because of the brutal nature of the crime.

Alleged prostitution and sexual history

Manytrue crime