Biological Control Agent on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Biological control or biocontrol is a method of controlling pests, such as

Biological control or biocontrol is a method of controlling pests, such as

Prickly pear cacti were introduced into

Prickly pear cacti were introduced into

Biological control or biocontrol is a method of controlling pests, such as

Biological control or biocontrol is a method of controlling pests, such as insect

Insects (from Latin ') are pancrustacean hexapod invertebrates of the class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body (head, thorax and abdomen), three pairs ...

s, mite

Mites are small arachnids (eight-legged arthropods). Mites span two large orders of arachnids, the Acariformes and the Parasitiformes, which were historically grouped together in the subclass Acari, but genetic analysis does not show clear evid ...

s, weed

A weed is a plant considered undesirable in a particular situation, "a plant in the wrong place", or a plant growing where it is not wanted.Harlan, J. R., & deWet, J. M. (1965). Some thoughts about weeds. ''Economic botany'', ''19''(1), 16-24. ...

s, and plant diseases, using other organisms. It relies on predation

Predation is a biological interaction

In ecology, a biological interaction is the effect that a pair of organisms living together in a community have on each other. They can be either of the same species (intraspecific interactions), or o ...

, parasitism, herbivory

A herbivore is an animal anatomically and physiologically adapted to eating plant material, for example foliage or marine algae, for the main component of its diet. As a result of their plant diet, herbivorous animals typically have mouthp ...

, or other natural mechanisms, but typically also involves an active human management role. It can be an important component of integrated pest management

Integrated pest management (IPM), also known as integrated pest control (IPC) is a broad-based approach that integrates both chemical and non-chemical practices for economic control of pests. IPM aims to suppress pest populations below the eco ...

(IPM) programs.

There are three basic strategies for biological pest control: classical (importation), where a natural enemy of a pest is introduced in the hope of achieving control; inductive (augmentation), in which a large population of natural enemies are administered for quick pest control; and inoculative (conservation), in which measures are taken to maintain natural enemies through regular reestablishment.

Natural enemies of insect pests, also known as biological control agents, include predators, parasitoids, pathogen

In biology, a pathogen ( el, πάθος, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of") in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a ger ...

s, and competitors

Competition is a rivalry where two or more parties strive for a common goal which cannot be shared: where one's gain is the other's loss (an example of which is a zero-sum game). Competition can arise between entities such as organisms, indivi ...

. Biological control agents of plant diseases are most often referred to as antagonists. Biological control agents of weeds include seed predators, herbivore

A herbivore is an animal anatomically and physiologically adapted to eating plant material, for example foliage or marine algae, for the main component of its diet. As a result of their plant diet, herbivorous animals typically have mouthp ...

s, and plant pathogens.

Biological control can have side-effects on biodiversity

Biodiversity or biological diversity is the variety and variability of life on Earth. Biodiversity is a measure of variation at the genetic ('' genetic variability''), species ('' species diversity''), and ecosystem ('' ecosystem diversity' ...

through attacks on non-target species by any of the above mechanisms, especially when a species is introduced without a thorough understanding of the possible consequences.

History

The term "biological control" was first used byHarry Scott Smith

Harry Scott Smith (November 29, 1883 – November 28, 1957), an entomologist and professor at University of California, Riverside (UCR), was a pioneer in the field of biological pest control.

United States Department of Agriculture

Smith grew ...

at the 1919 meeting of the Pacific Slope Branch of the American Association of Economic Entomologists, in Riverside, California

Riverside is a city in and the county seat of Riverside County, California, United States, in the Inland Empire metropolitan area. It is named for its location beside the Santa Ana River. It is the most populous city in the Inland Empire and ...

. It was brought into more widespread use by the entomologist Paul H. DeBach (1914–1993) who worked on citrus crop pests throughout his life. However, the practice has previously been used for centuries. The first report of the use of an insect species to control an insect pest comes from " Nanfang Caomu Zhuang" (南方草木狀 ''Plants of the Southern Regions'') (), attributed to Western Jin dynasty

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

botanist ''Ji Han'' (嵇含, 263–307), in which it is mentioned that "''Jiaozhi

Jiaozhi (standard Chinese, pinyin: ''Jiāozhǐ''), or Giao Chỉ (Vietnamese), was a historical region ruled by various Chinese dynasties, corresponding to present-day northern Vietnam. The kingdom of Nanyue (204–111 BC) set up the Jiaozhi C ...

people sell ants and their nests attached to twigs looking like thin cotton envelopes, the reddish-yellow ant being larger than normal. Without such ants, southern citrus fruits will be severely insect-damaged''". The ants used are known as ''huang gan'' (''huang'' = yellow, ''gan'' = citrus) ants (''Oecophylla smaragdina

''Oecophylla smaragdina'' (common names include Asian weaver ant, weaver ant, green ant, green tree ant, semut rangrang, semut kerangga, and orange gaster) is a species of arboreal ant found in tropical Asia and Australia. These ants form colon ...

''). The practice was later reported by Ling Biao Lu Yi (late Tang Dynasty

The Tang dynasty (, ; zh, t= ), or Tang Empire, was an imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907 AD, with an interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dynasty and followed by the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdo ...

or Early Five Dynasties

The Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (), from 907 to 979, was an era of political upheaval and division in 10th-century Imperial China. Five dynastic states quickly succeeded one another in the Central Plain, and more than a dozen concu ...

), in ''Ji Le Pian'' by ''Zhuang Jisu'' ( Southern Song Dynasty), in the ''Book of Tree Planting'' by Yu Zhen Mu (Ming Dynasty

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last ort ...

), in the book ''Guangdong Xing Yu'' (17th century), ''Lingnan'' by Wu Zhen Fang (Qing Dynasty), in ''Nanyue Miscellanies'' by Li Diao Yuan, and others.

Biological control techniques as we know them today started to emerge in the 1870s. During this decade, in the US, the Missouri State Entomologist C. V. Riley and the Illinois State Entomologist W. LeBaron began within-state redistribution of parasitoids to control crop pests. The first international shipment of an insect as a biological control agent was made by Charles V. Riley in 1873, shipping to France the predatory mites ''Tyroglyphus phylloxera'' to help fight the grapevine phylloxera ( ''Daktulosphaira vitifoliae'') that was destroying grapevines in France. The United States Department of Agriculture

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) is the federal executive department responsible for developing and executing federal laws related to farming, forestry, rural economic development, and food. It aims to meet the needs of com ...

(USDA) initiated research in classical biological control following the establishment of the Division of Entomology in 1881, with C. V. Riley as Chief. The first importation of a parasitoidal wasp into the United States was that of the braconid ''Cotesia glomerata

''Cotesia glomerata'', the white butterfly parasite, is a small parasitoid wasp species belonging to family Braconidae. It was first described by Carl Linnaeus in his 1758 publication 10th edition of Systema Naturae.

Description

The adults ...

'' in 1883–1884, imported from Europe to control the invasive cabbage white butterfly, ''Pieris rapae

''Pieris rapae'' is a small- to medium-sized butterfly species of the whites-and-yellows family Pieridae. It is known in Europe as the small white, in North America as the cabbage white or cabbage butterfly, on several continents as the small c ...

''. In 1888–1889 the vedalia beetle, ''Rodolia cardinalis

''Novius cardinalis'' (common names vedalia beetle or cardinal ladybird) is a species of ladybird beetle native to Australia. It was formerly placed in the genus ''Rodolia'', but that genus was synonymized under the genus '' Novius'' in 2020.Pan ...

'', a lady beetle, was introduced from Australia to California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the ...

to control the cottony cushion scale, '' Icerya purchasi''. This had become a major problem for the newly developed citrus industry in California, but by the end of 1889, the cottony cushion scale population had already declined. This great success led to further introductions of beneficial insects into the US.Coulson, J. R.; Vail, P. V.; Dix M.E.; Nordlund, D.A.; Kauffman, W.C.; Eds. 2000. 110 years of biological control research and development in the United States Department of Agriculture: 1883–1993. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. pages=3–11

In 1905 the USDA initiated its first large-scale biological control program, sending entomologists to Europe and Japan to look for natural enemies of the spongy moth, '' Lymantria dispar dispar'', and the brown-tail moth, ''Euproctis chrysorrhoea'', invasive pests of trees and shrubs. As a result, nine parasitoids (solitary wasps) of the spongy moth, seven of the brown-tail moth, and two predators of both moths became established in the US. Although the spongy moth was not fully controlled by these natural enemies, the frequency, duration, and severity of its outbreaks were reduced and the program was regarded as successful. This program also led to the development of many concepts, principles, and procedures for the implementation of biological control programs.

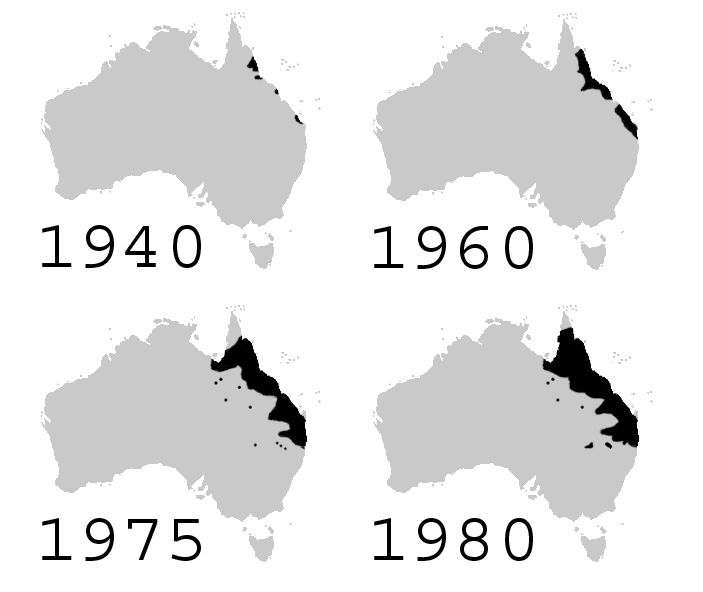

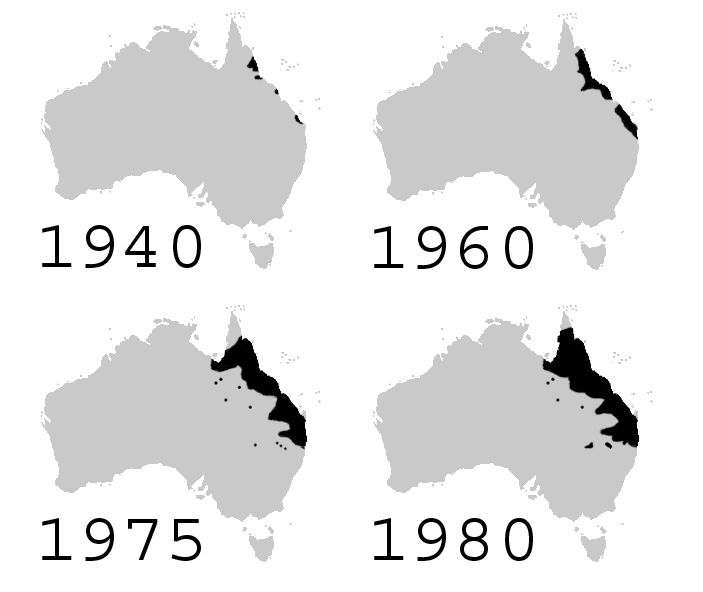

Prickly pear cacti were introduced into

Prickly pear cacti were introduced into Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, established_ ...

, Australia as ornamental plants, starting in 1788. They quickly spread to cover over 25 million hectares of Australia by 1920, increasing by 1 million hectares per year. Digging, burning, and crushing all proved ineffective. Two control agents were introduced to help control the spread of the plant, the cactus moth '' Cactoblastis cactorum'', and the scale insect '' Dactylopius''. Between 1926 and 1931, tens of millions of cactus moth eggs were distributed around Queensland with great success, and by 1932, most areas of prickly pear had been destroyed.

The first reported case of a classical biological control attempt in Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tota ...

involves the parasitoidal wasp '' Trichogramma minutum''. Individuals were caught in New York State

New York, officially the State of New York, is a U.S. state, state in the Northeastern United States. It is often called New York State to distinguish it from its largest city, New York City. With a total area of , New York is the List of U.S. ...

and released in Ontario

Ontario ( ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada.Ontario is located in the geographic eastern half of Canada, but it has historically and politically been considered to be part of Central Canada. Located in Central C ...

gardens in 1882 by William Saunders, a trained chemist and first Director of the Dominion Experimental Farms, for controlling the invasive currantworm ''Nematus ribesii

''Nematus ribesii'' is a species of sawfly in the family Tenthredinidae. English names include common gooseberry sawfly

Importation or classical biological control involves the introduction of a pest's natural enemies to a new locale where they do not occur naturally. Early instances were often unofficial and not based on research, and some introduced species became serious pests themselves.

To be most effective at controlling a pest, a biological control agent requires a colonizing ability which allows it to keep pace with changes to the habitat in space and time. Control is greatest if the agent has temporal persistence so that it can maintain its population even in the temporary absence of the target species, and if it is an opportunistic forager, enabling it to rapidly exploit a pest population.

One of the earliest successes was in controlling '' Icerya purchasi'' (cottony cushion scale) in Australia, using a predatory insect ''

Augmentation involves the supplemental release of natural enemies that occur in a particular area, boosting the naturally occurring populations there. In inoculative release, small numbers of the control agents are released at intervals to allow them to reproduce, in the hope of setting up longer-term control and thus keeping the pest down to a low level, constituting prevention rather than cure. In inundative release, in contrast, large numbers are released in the hope of rapidly reducing a damaging pest population, correcting a problem that has already arisen. Augmentation can be effective, but is not guaranteed to work, and depends on the precise details of the interactions between each pest and control agent.

An example of inoculative release occurs in the horticultural production of several crops in

Augmentation involves the supplemental release of natural enemies that occur in a particular area, boosting the naturally occurring populations there. In inoculative release, small numbers of the control agents are released at intervals to allow them to reproduce, in the hope of setting up longer-term control and thus keeping the pest down to a low level, constituting prevention rather than cure. In inundative release, in contrast, large numbers are released in the hope of rapidly reducing a damaging pest population, correcting a problem that has already arisen. Augmentation can be effective, but is not guaranteed to work, and depends on the precise details of the interactions between each pest and control agent.

An example of inoculative release occurs in the horticultural production of several crops in

Cropping systems can be modified to favor natural enemies, a practice sometimes referred to as habitat manipulation. Providing a suitable habitat, such as a shelterbelt,

Cropping systems can be modified to favor natural enemies, a practice sometimes referred to as habitat manipulation. Providing a suitable habitat, such as a shelterbelt,

Predators are mainly free-living species that directly consume a large number of

Predators are mainly free-living species that directly consume a large number of  Several species of

Several species of  For rodent pests,

For rodent pests,

Entomopathogenic fungi, which cause disease in insects, include at least 14 species that attack

Entomopathogenic fungi, which cause disease in insects, include at least 14 species that attack

Vertebrate animals tend to be generalist feeders, and seldom make good biological control agents; many of the classic cases of "biocontrol gone awry" involve vertebrates. For example, the

Vertebrate animals tend to be generalist feeders, and seldom make good biological control agents; many of the classic cases of "biocontrol gone awry" involve vertebrates. For example, the

Introduction to Biological Control

. Midwest Institute for Biological Control, Illinois. * * * *

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20071123044914/http://www.biotechnologyonline.gov.au/enviro/canetoad.cfm Cane toad: a case study 2003. * Humphrey, J. and Hyatt. 2004. CSIRO Australian Animal Health Laboratory. ''Biological Control of the Cane Toad Bufo marinus in Australia'' * * Johnson, M. 2000. Nature and Scope of Biological Control. ''Biological Control of Pests''.

Association of Natural Biocontrol ProducersInternational Organization for Biological Control

{{DEFAULTSORT:Biological Pest Control American inventions Chinese inventions Insects in culture

Rodolia cardinalis

''Novius cardinalis'' (common names vedalia beetle or cardinal ladybird) is a species of ladybird beetle native to Australia. It was formerly placed in the genus ''Rodolia'', but that genus was synonymized under the genus '' Novius'' in 2020.Pan ...

'' (the vedalia beetle). This success was repeated in California using the beetle and a parasitoidal fly, ''Cryptochaetum

''Cryptochetum'' is a genus of scale parasite flies in the family Cryptochetidae. There are more than 30 described species in ''Cryptochetum''.

Species

These 35 species belong to the genus ''Cryptochetum'':

*'' C. acuticornutum'' (Yang & Yang, ...

iceryae''. Other successful cases include the control of '' Antonina graminis'' in Texas by '' Neodusmetia sangwani'' in the 1960s.

Damage from '' Hypera postica'', the alfalfa weevil, a serious introduced pest of forage, was substantially reduced by the introduction of natural enemies. 20 years after their introduction the population of weevil

Weevils are beetles belonging to the superfamily Curculionoidea, known for their elongated snouts. They are usually small, less than in length, and herbivorous. Approximately 97,000 species of weevils are known. They belong to several families, ...

s in the alfalfa area treated for alfalfa weevil in the Northeastern United States remained 75 percent down.

Alligator weed was introduced to the United States from South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the souther ...

. It takes root in shallow water, interfering with navigation

Navigation is a field of study that focuses on the process of monitoring and controlling the movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another.Bowditch, 2003:799. The field of navigation includes four general categories: land navigation, ...

, irrigation

Irrigation (also referred to as watering) is the practice of applying controlled amounts of water to land to help grow crops, landscape plants, and lawns. Irrigation has been a key aspect of agriculture for over 5,000 years and has been dev ...

, and flood control

Flood control methods are used to reduce or prevent the detrimental effects of flood waters."Flood Control", MSN Encarta, 2008 (see below: Further reading). Flood relief methods are used to reduce the effects of flood waters or high water level ...

. The alligator weed flea beetle and two other biological controls were released in Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, a ...

, greatly reducing the amount of land covered by the plant. Another aquatic weed, the giant salvinia (''Salvinia molesta

''Salvinia molesta'', commonly known as giant salvinia, or as kariba weed after it infested a large portion of Lake Kariba between Zimbabwe and Zambia, is an aquatic fern, native to south-eastern Brazil. It is a free-floating plant that does n ...

'') is a serious pest, covering waterways, reducing water flow and harming native species. Control with the salvinia weevil ('' Cyrtobagous salviniae'') and the salvinia stem-borer moth ('' Samea multiplicalis)'' is effective in warm climates, and in Zimbabwe, a 99% control of the weed was obtained over a two-year period.

Small commercially reared parasitoidal wasp

A wasp is any insect of the narrow-waisted suborder Apocrita of the order Hymenoptera which is neither a bee nor an ant; this excludes the broad-waisted sawflies (Symphyta), which look somewhat like wasps, but are in a separate suborder. Th ...

s, '' Trichogramma ostriniae'', provide limited and erratic control of the European corn borer (''Ostrinia nubilalis''), a serious pest. Careful formulations of the bacterium ''Bacillus thuringiensis

''Bacillus thuringiensis'' (or Bt) is a gram-positive, soil-dwelling bacterium, the most commonly used biological pesticide worldwide. ''B. thuringiensis'' also occurs naturally in the gut of caterpillars of various types of moths and butter ...

'' are more effective. The O. nubilalis integrated control releasing Tricogramma brassicae (egg parasitoiod) and later Bacillus thuringiensis subs. kurstaki (larvicidae effect) reduce pest damages as better than insecticide treatments

The population of ''Levuana iridescens

The levuana moth (''Levuana iridescens'') is an extinct species of moth in the family Zygaenidae. It is monotypic within the genus ''Levuana''.

The levuana moth became a serious pest for coconut plants in 1877, in Viti Levu, Fiji. On the islan ...

'', the Levuana moth, a serious coconut pest in Fiji, was brought under control by a classical biological control program in the 1920s.

Augmentation

Augmentation involves the supplemental release of natural enemies that occur in a particular area, boosting the naturally occurring populations there. In inoculative release, small numbers of the control agents are released at intervals to allow them to reproduce, in the hope of setting up longer-term control and thus keeping the pest down to a low level, constituting prevention rather than cure. In inundative release, in contrast, large numbers are released in the hope of rapidly reducing a damaging pest population, correcting a problem that has already arisen. Augmentation can be effective, but is not guaranteed to work, and depends on the precise details of the interactions between each pest and control agent.

An example of inoculative release occurs in the horticultural production of several crops in

Augmentation involves the supplemental release of natural enemies that occur in a particular area, boosting the naturally occurring populations there. In inoculative release, small numbers of the control agents are released at intervals to allow them to reproduce, in the hope of setting up longer-term control and thus keeping the pest down to a low level, constituting prevention rather than cure. In inundative release, in contrast, large numbers are released in the hope of rapidly reducing a damaging pest population, correcting a problem that has already arisen. Augmentation can be effective, but is not guaranteed to work, and depends on the precise details of the interactions between each pest and control agent.

An example of inoculative release occurs in the horticultural production of several crops in greenhouse

A greenhouse (also called a glasshouse, or, if with sufficient heating, a hothouse) is a structure with walls and roof made chiefly of transparent material, such as glass, in which plants requiring regulated climatic conditions are grown.These ...

s. Periodic releases of the parasitoidal wasp, '' Encarsia formosa'', are used to control greenhouse whitefly

Whiteflies are Hemipterans that typically feed on the undersides of plant leaves. They comprise the family Aleyrodidae, the only family in the superfamily Aleyrodoidea. More than 1550 species have been described.

Description and taxonomy

The ...

, while the predatory mite '' Phytoseiulus persimilis'' is used for control of the two-spotted spider mite.

The egg parasite '' Trichogramma'' is frequently released inundatively to control harmful moths. New way for inundative releases are now introduced i.e. use of drones. Egg parasitoids are able to find the eggs of the target host by means of several cues. Kairomones were found on moth scales. Similarly, ''Bacillus thuringiensis'' and other microbial insecticides are used in large enough quantities for a rapid effect. Recommended release rates for ''Trichogramma'' in vegetable or field crops range from 5,000 to 200,000 per acre (1 to 50 per square metre) per week according to the level of pest infestation. Similarly, nematodes

The nematodes ( or grc-gre, Νηματώδη; la, Nematoda) or roundworms constitute the phylum Nematoda (also called Nemathelminthes), with plant-parasitic nematodes also known as eelworms. They are a diverse animal phylum inhabiting a broa ...

that kill insects (that are entomopathogenic) are released at rates of millions and even billions per acre for control of certain soil-dwelling insect pests.

Conservation

The conservation of existing natural enemies in an environment is the third method of biological pest control. Natural enemies are already adapted to thehabitat

In ecology, the term habitat summarises the array of resources, physical and biotic factors that are present in an area, such as to support the survival and reproduction of a particular species. A species habitat can be seen as the physical ...

and to the target pest, and their conservation can be simple and cost-effective, as when nectar-producing crop plants are grown in the borders of rice fields. These provide nectar to support parasitoids and predators of planthopper pests and have been demonstrated to be so effective (reducing pest densities by 10- or even 100-fold) that farmers sprayed 70% less insecticides and enjoyed yields boosted by 5%. Predators of aphids were similarly found to be present in tussock grasses by field boundary hedges in England, but they spread too slowly to reach the centers of fields. Control was improved by planting a meter-wide strip of tussock grasses in field centers, enabling aphid predators to overwinter there.

Cropping systems can be modified to favor natural enemies, a practice sometimes referred to as habitat manipulation. Providing a suitable habitat, such as a shelterbelt,

Cropping systems can be modified to favor natural enemies, a practice sometimes referred to as habitat manipulation. Providing a suitable habitat, such as a shelterbelt, hedgerow

A hedge or hedgerow is a line of closely spaced shrubs and sometimes trees, planted and trained to form a barrier or to mark the boundary of an area, such as between neighbouring properties. Hedges that are used to separate a road from adjoini ...

, or beetle bank where beneficial insects such as parasitoidal wasps can live and reproduce, can help ensure the survival of populations of natural enemies. Things as simple as leaving a layer of fallen leaves or mulch in place provides a suitable food source for worms and provides a shelter for insects, in turn being a food source for such beneficial mammals as hedgehog

A hedgehog is a spiny mammal of the subfamily Erinaceinae, in the eulipotyphlan family Erinaceidae. There are seventeen species of hedgehog in five genera found throughout parts of Europe, Asia, and Africa, and in New Zealand by introduct ...

s and shrew

Shrews (family Soricidae) are small mole-like mammals classified in the order Eulipotyphla. True shrews are not to be confused with treeshrews, otter shrews, elephant shrews, West Indies shrews, or marsupial shrews, which belong to diffe ...

s. Compost pile

Compost is a mixture of ingredients used as plant fertilizer and to improve soil's physical, chemical and biological properties. It is commonly prepared by decomposing plant, food waste, recycling organic materials and manure. The resulting ...

s and stacks of wood can provide shelter for invertebrates and small mammals. Long grass and pond

A pond is an area filled with water, either natural or Artificiality, artificial, that is smaller than a lake. Defining them to be less than in area, less than deep, and with less than 30% Aquatic plant, emergent vegetation helps in disting ...

s support amphibians. Not removing dead annuals and non-hardy plants in the autumn allow insects to make use of their hollow stems during winter. In California, prune trees are sometimes planted in grape vineyards to provide an improved overwintering habitat or refuge for a key grape pest parasitoid. The providing of artificial shelters in the form of wooden caskets, box

A box (plural: boxes) is a container used for the storage or transportation of its contents. Most boxes have flat, parallel, rectangular sides. Boxes can be very small (like a matchbox) or very large (like a shipping box for furniture), and ca ...

es or flowerpot

A flowerpot, planter, planterette or plant pot, is a container in which flowers and other plants are cultivated and displayed. Historically, and still to a significant extent today, they are made from plain terracotta with no ceramic glaze, wi ...

s is also sometimes undertaken, particularly in gardens, to make a cropped area more attractive to natural enemies. For example, earwigs are natural predators that can be encouraged in gardens by hanging upside-down flowerpots filled with straw

Straw is an agricultural byproduct consisting of the dry stalks of cereal plants after the grain and chaff have been removed. It makes up about half of the yield of cereal crops such as barley, oats, rice, rye and wheat. It has a numbe ...

or wood wool

Wood wool, known primarily as excelsior in North America, is a product made of wood slivers cut from logs. It is mainly used in packaging, for cooling pads in home evaporative cooling systems known as swamp coolers, for erosion control mats, and ...

. Green lacewings can be encouraged by using plastic bottles with an open bottom and a roll of cardboard inside. Birdhouses enable insectivorous birds to nest; the most useful birds can be attracted by choosing an opening just large enough for the desired species.

In cotton production, the replacement of broad-spectrum insecticides with selective control measures such as Bt cotton

Bt cotton is a genetically modified pest resistant plant cotton variety, which produces an insecticide to combat bollworm.

Description

Strains of the bacterium ''Bacillus thuringiensis'' produce over 200 different Bt toxins, each harmful to di ...

can create a more favorable environment for natural enemies of cotton pests due to reduced insecticide exposure risk. Such predators or parasitoids

In evolutionary ecology, a parasitoid is an organism that lives in close association with its host at the host's expense, eventually resulting in the death of the host. Parasitoidism is one of six major evolutionary strategies within parasitis ...

can control pests not affected by the Bt protein. Reduced prey quality and abundance associated with increased control from Bt cotton can also indirectly decrease natural enemy populations in some cases, but the percentage of pests eaten or parasitized in Bt and non-Bt cotton are often similar.

Biological control agents

Predators

Predators are mainly free-living species that directly consume a large number of

Predators are mainly free-living species that directly consume a large number of prey

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill the ...

during their whole lifetime. Given that many major crop pests are insects, many of the predators used in biological control are insectivorous species. Lady beetles, and in particular their larvae which are active between May and July in the northern hemisphere, are voracious predators of aphid

Aphids are small sap-sucking insects and members of the superfamily Aphidoidea. Common names include greenfly and blackfly, although individuals within a species can vary widely in color. The group includes the fluffy white woolly aphids. A ...

s, and also consume mites

Mites are small arachnids (eight-legged arthropods). Mites span two large orders of arachnids, the Acariformes and the Parasitiformes, which were historically grouped together in the subclass Acari, but genetic analysis does not show clear evi ...

, scale insect

Scale insects are small insects of the order Hemiptera, suborder Sternorrhyncha. Of dramatically variable appearance and extreme sexual dimorphism, they comprise the infraorder Coccomorpha which is considered a more convenient grouping than th ...

s and small caterpillar

Caterpillars ( ) are the larva, larval stage of members of the order Lepidoptera (the insect order comprising butterfly, butterflies and moths).

As with most common names, the application of the word is arbitrary, since the larvae of sawfly ...

s. The spotted lady beetle (''Coleomegilla maculata

''Coleomegilla maculata'', commonly known as the spotted lady beetle, pink spotted lady beetle or twelve-spotted lady beetle, is a large coccinellid beetle native to North America. The adults and larvae feed primarily on aphids and the species ...

'') is also able to feed on the eggs and larvae of the Colorado potato beetle

The Colorado potato beetle (''Leptinotarsa decemlineata''), also known as the Colorado beetle, the ten-striped spearman, the ten-lined potato beetle, or the potato bug, is a major pest of potato crops. It is about long, with a bright yellow/or ...

(''Leptinotarsa decemlineata'').

The larvae of many hoverfly

Hover flies, also called flower flies or syrphid flies, make up the insect family Syrphidae. As their common name suggests, they are often seen hovering or nectaring at flowers; the adults of many species feed mainly on nectar and pollen, while ...

species principally feed upon aphid

Aphids are small sap-sucking insects and members of the superfamily Aphidoidea. Common names include greenfly and blackfly, although individuals within a species can vary widely in color. The group includes the fluffy white woolly aphids. A ...

s, one larva devouring up to 400 in its lifetime. Their effectiveness in commercial crops has not been studied.

The running crab spider '' Philodromus cespitum'' also prey heavily on aphids, and act as a biological control agent in European fruit orchards.

Several species of

Several species of entomopathogenic nematode

Entomopathogenic nematodes (EPN) are a group of nematodes (thread worms), that cause death to insects. The term ''entomopathogenic'' has a Greek origin, with ''entomon'', meaning ''insect'', and ''pathogenic'', which means ''causing disease''. Th ...

are important predators of insect and other invertebrate pests. Entomopathogenic nematodes form a stress–resistant stage known as the infective juvenile. These spread in the soil and infect suitable insect hosts. Upon entering the insect they move to the hemolymph

Hemolymph, or haemolymph, is a fluid, analogous to the blood in vertebrates, that circulates in the interior of the arthropod (invertebrate) body, remaining in direct contact with the animal's tissues. It is composed of a fluid plasma in which ...

where they recover from their stagnated state of development and release their bacterial

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among ...

symbionts

Symbiosis (from Greek , , "living together", from , , "together", and , bíōsis, "living") is any type of a close and long-term biological interaction between two different biological organisms, be it mutualistic, commensalistic, or parasit ...

. The bacterial symbionts reproduce and release toxins, which then kill the host insect. '' Phasmarhabditis hermaphrodita'' is a microscopic nematode that kills slugs. Its complex life cycle includes a free-living, infective stage in the soil where it becomes associated with a pathogenic bacteria such as '' Moraxella osloensis''. The nematode enters the slug through the posterior mantle region, thereafter feeding and reproducing inside, but it is the bacteria that kill the slug. The nematode is available commercially in Europe and is applied by watering onto moist soil. Entomopathogenic nematodes have a limited shelf life

Shelf life is the length of time that a commodity may be stored without becoming unfit for use, consumption, or sale. In other words, it might refer to whether a commodity should no longer be on a pantry shelf (unfit for use), or no longer on a ...

because of their limited resistance to high temperature and dry conditions. The type of soil they are applied to may also limit their effectiveness.

Species used to control spider mites include the predatory mites '' Phytoseiulus persimilis'', '' Neoseilus californicus,'' and ''Amblyseius

''Amblyseius'' is a large genus of predatory mites belonging to the family Phytoseiidae.de Moraes, G. J. (2005)Phytoseiidae Species Listing Biology Catalog, Texas A&M University. Retrieved on August 19, 2010. Many members of this genus feed on ...

cucumeris'', the predatory midge '' Feltiella acarisuga'', and a ladybird ''Stethorus punctillum

''Stethorus punctillum'', known generally as the lesser mite destroyer or spider mite destroyer, is a species of lady beetle in the family Coccinellidae

Coccinellidae () is a widespread family of small beetles ranging in size from . They a ...

''. The bug ''Orius insidiosus

''Orius insidiosus'', common name the insidious flower bug, is a species of minute pirate bug, a predatory insect in the order Hemiptera (the true bugs). They are considered beneficial, as they feed on small pest arthropods and their eggs. They a ...

'' has been successfully used against the two-spotted spider mite and the western flower thrips (''Frankliniella occidentalis'').

Predators including ''Cactoblastis cactorum'' (mentioned above) can also be used to destroy invasive plant species. As another example, the poison hemlock moth (''Agonopterix alstroemeriana)'' can be used to control poison hemlock (''Conium maculatum''). During its larval stage, the moth strictly consumes its host plant, poison hemlock, and can exist at hundreds of larvae per individual host plant, destroying large swathes of the hemlock.

For rodent pests,

For rodent pests, cat

The cat (''Felis catus'') is a domestic species of small carnivorous mammal. It is the only domesticated species in the family Felidae and is commonly referred to as the domestic cat or house cat to distinguish it from the wild members of ...

s are effective biological control when used in conjunction with reduction of "harborage"/hiding locations. While cats are effective at preventing rodent "population explosions", they are not effective for eliminating pre-existing severe infestations. Barn owls are also sometimes used as biological rodent control. Although there are no quantitative studies of the effectiveness of barn owls for this purpose, they are known rodent predators that can be used in addition to or instead of cats; they can be encouraged into an area with nest boxes.

In Honduras, where the mosquito ''Aedes aegypti

''Aedes aegypti'', the yellow fever mosquito, is a mosquito that can spread dengue fever, chikungunya, Zika fever, Mayaro and yellow fever viruses, and other disease agents. The mosquito can be recognized by black and white markings on its l ...

'' was transmitting dengue fever

Dengue fever is a mosquito-borne tropical disease caused by the dengue virus. Symptoms typically begin three to fourteen days after infection. These may include a high fever, headache, vomiting, muscle and joint pains, and a characteristic ...

and other infectious diseases, biological control was attempted by a community action plan; copepod

Copepods (; meaning "oar-feet") are a group of small crustaceans found in nearly every freshwater and saltwater habitat. Some species are planktonic (inhabiting sea waters), some are benthic (living on the ocean floor), a number of species have p ...

s, baby turtle

Turtles are an order of reptiles known as Testudines, characterized by a special shell developed mainly from their ribs. Modern turtles are divided into two major groups, the Pleurodira (side necked turtles) and Cryptodira (hidden necked ...

s, and juvenile tilapia

Tilapia ( ) is the common name for nearly a hundred species of cichlid fish from the coelotilapine, coptodonine, heterotilapine, oreochromine, pelmatolapiine, and tilapiine tribes (formerly all were "Tilapiini"), with the economically most i ...

were added to the wells and tanks where the mosquito breeds and the mosquito larvae were eliminated.

Even amongst arthropods usually thought of as obligate predator

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill ...

s of animals (especially other arthropods), floral

A flower, sometimes known as a bloom or blossom, is the reproductive structure found in flowering plants (plants of the division Angiospermae). The biological function of a flower is to facilitate reproduction, usually by providing a mechanism ...

food sources ( nectar and to a lesser degree pollen

Pollen is a powdery substance produced by seed plants. It consists of pollen grains (highly reduced microgametophytes), which produce male gametes (sperm cells). Pollen grains have a hard coat made of sporopollenin that protects the gametop ...

) are often useful adjunct sources. It had been noticed in one study that adult '' Adalia bipunctata'' (predator and common biocontrol of ''Ephestia kuehniella

The Mediterranean flour moth or mill moth (''Ephestia kuehniella'') is a moth of the family Pyralidae. It is a common pest of cereal grains, especially flour. This moth is found throughout the world, especially in countries with temperate climate ...

'') could survive on flowers but never completed its life cycle

Life cycle, life-cycle, or lifecycle may refer to:

Science and academia

* Biological life cycle, the sequence of life stages that an organism undergoes from birth to reproduction ending with the production of the offspring

* Life-cycle hypothesi ...

, so a meta-analysis was done to find such an overall trend in previously published data, if it existed. In some cases floral resources are outright necessary. Overall, floral resources (and an imitation, i.e. sugar water) increase longevity

The word " longevity" is sometimes used as a synonym for "life expectancy" in demography. However, the term ''longevity'' is sometimes meant to refer only to especially long-lived members of a population, whereas ''life expectancy'' is always d ...

and fecundity

Fecundity is defined in two ways; in human demography, it is the potential for reproduction of a recorded population as opposed to a sole organism, while in population biology, it is considered similar to fertility, the natural capability to pr ...

, meaning even predatory population numbers can depend on non-prey food abundance. Thus biocontrol population maintenance - and success - may depend on nearby flowers.

Parasitoids

Parasitoids lay their eggs on or in the body of an insect host, which is then used as a food for developing larvae. The host is ultimately killed. Most insect parasitoids arewasps

A wasp is any insect of the narrow-waisted suborder Apocrita of the order Hymenoptera which is neither a bee nor an ant; this excludes the broad-waisted sawflies (Symphyta), which look somewhat like wasps, but are in a separate suborder. Th ...

or flies

Flies are insects of the Order (biology), order Diptera, the name being derived from the Ancient Greek, Greek δι- ''di-'' "two", and πτερόν ''pteron'' "wing". Insects of this order use only a single pair of wings to fly, the hindwing ...

, and many have a very narrow host range. The most important groups are the ichneumonid wasps, which mainly use caterpillar

Caterpillars ( ) are the larva, larval stage of members of the order Lepidoptera (the insect order comprising butterfly, butterflies and moths).

As with most common names, the application of the word is arbitrary, since the larvae of sawfly ...

s as hosts; braconid wasps, which attack caterpillars and a wide range of other insects including aphids; chalcidoid wasps, which parasitize eggs and larvae of many insect species; and tachinid flies, which parasitize a wide range of insects including caterpillars, beetle

Beetles are insects that form the order Coleoptera (), in the superorder Endopterygota. Their front pair of wings are hardened into wing-cases, elytra, distinguishing them from most other insects. The Coleoptera, with about 400,000 describ ...

adults and larvae, and true bugs

Hemiptera (; ) is an order of insects, commonly called true bugs, comprising over 80,000 species within groups such as the cicadas, aphids, planthoppers, leafhoppers, assassin bugs, bed bugs, and shield bugs. They range in size from to a ...

. Parasitoids are most effective at reducing pest populations when their host organisms have limited refuges to hide from them.

Parasitoids are among the most widely used biological control agents. Commercially, there are two types of rearing systems: short-term daily output with high production of parasitoids per day, and long-term, low daily output systems. In most instances, production will need to be matched with the appropriate release dates when susceptible host species at a suitable phase of development will be available. Larger production facilities produce on a yearlong basis, whereas some facilities produce only seasonally. Rearing facilities are usually a significant distance from where the agents are to be used in the field, and transporting the parasitoids from the point of production to the point of use can pose problems. Shipping conditions can be too hot, and even vibrations from planes or trucks can adversely affect parasitoids.

'' Encarsia formosa'' is a small parasitoid wasp attacking whiteflies

Whiteflies are Hemipterans that typically feed on the undersides of plant leaves. They comprise the family Aleyrodidae, the only family in the superfamily Aleyrodoidea. More than 1550 species have been described.

Description and taxonomy

The ...

, sap-feeding insects which can cause wilting and black sooty moulds in glasshouse vegetable and ornamental crops. It is most effective when dealing with low level infestations, giving protection over a long period of time. The wasp lays its eggs in young whitefly 'scales', turning them black as the parasite larvae pupate. '' Gonatocerus ashmeadi'' ( Hymenoptera: Mymaridae) has been introduced to control the glassy-winged sharpshooter ''Homalodisca vitripennis'' (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae) in French Polynesia

)Territorial motto: ( en, "Great Tahiti of the Golden Haze")

, anthem =

, song_type = Regional anthem

, song = "Ia Ora 'O Tahiti Nui"

, image_map = French Polynesia on the globe (French Polynesia centered).svg

, map_alt = Location of French ...

and has successfully controlled ~95% of the pest density.

The eastern spruce budworm is an example of a destructive insect in fir

Firs (''Abies'') are a genus of 48–56 species of evergreen coniferous trees in the family (biology), family Pinaceae. They are found on mountains throughout much of North America, North and Central America, Europe, Asia, and North Africa. The ...

and spruce

A spruce is a tree of the genus ''Picea'' (), a genus of about 35 species of coniferous evergreen trees in the family Pinaceae, found in the northern temperate and boreal ( taiga) regions of the Earth. ''Picea'' is the sole genus in the sub ...

forests. Birds are a natural form of biological control, but the ''Trichogramma minutum'', a species of parasitic wasp, has been investigated as an alternative to more controversial chemical controls.

There are a number of recent studies pursuing sustainable methods for controlling urban cockroaches using parasitic wasps. Since most cockroaches remain in the sewer system and sheltered areas which are inaccessible to insecticides, employing active-hunter wasps is a strategy to try and reduce their populations.

Pathogens

Pathogenic micro-organisms includebacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were am ...

, fungi

A fungus (plural, : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of Eukaryote, eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and Mold (fungus), molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified ...

, and viruses

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

Cell may also refer to:

Locations

* Monastic cell, a small room ...

. They kill or debilitate their host and are relatively host-specific. Various microbial

A microorganism, or microbe,, ''mikros'', "small") and ''organism'' from the el, ὀργανισμός, ''organismós'', "organism"). It is usually written as a single word but is sometimes hyphenated (''micro-organism''), especially in olde ...

insect diseases occur naturally, but may also be used as biological pesticide

A Biopesticide is a biological substance or organism that damages, kills, or repels organisms seens as pests. Biological pest management intervention involves predatory, parasitic, or chemical relationships.

They are obtained from organisms inclu ...

s. When naturally occurring, these outbreaks are density-dependent in that they generally only occur as insect populations become denser.

The use of pathogens against aquatic weed Aquatic plant management involves the science and methodologies used to control invasive and non-invasive aquatic plant species in waterways. Methods used include spraying herbicide, biological controls, mechanical removal as well as habitat modifi ...

s was unknown until a groundbreaking 1972 proposal by Zettler and Freeman. Up to that point biocontrol of any kind had not been used against any water weeds. In their review of the possibilities, they noted the lack of interest and information thus far, and listed what was known of pests-of-pests - whether pathogens or not. They proposed that this should be relatively straightfoward to apply in the same way as other biocontrols. And indeed in the decades since, the same biocontrol methods that are routine on land have become common in the water.

Bacteria

Bacteria used for biological control infect insects via their digestive tracts, so they offer only limited options for controlling insects with sucking mouth parts such as aphids and scale insects. ''Bacillus thuringiensis

''Bacillus thuringiensis'' (or Bt) is a gram-positive, soil-dwelling bacterium, the most commonly used biological pesticide worldwide. ''B. thuringiensis'' also occurs naturally in the gut of caterpillars of various types of moths and butter ...

'', a soil-dwelling bacterium, is the most widely applied species of bacteria used for biological control, with at least four sub-species used against Lepidopteran (moth

Moths are a paraphyletic group of insects that includes all members of the order Lepidoptera that are not butterflies, with moths making up the vast majority of the order. There are thought to be approximately 160,000 species of moth, many of ...

, butterfly

Butterflies are insects in the macrolepidopteran clade Rhopalocera from the order Lepidoptera, which also includes moths. Adult butterflies have large, often brightly coloured wings, and conspicuous, fluttering flight. The group comprises ...

), Coleoptera

Beetles are insects that form the order Coleoptera (), in the superorder Endopterygota. Their front pair of wings are hardened into wing-cases, elytra, distinguishing them from most other insects. The Coleoptera, with about 400,000 describ ...

n (beetle) and Dipteran (true fly) insect pests. The bacterium is available to organic farmers in sachets of dried spores which are mixed with water and sprayed onto vulnerable plants such as brassica

''Brassica'' () is a genus of plants in the cabbage and mustard family (Brassicaceae). The members of the genus are informally known as cruciferous vegetables, cabbages, or mustard plants. Crops from this genus are sometimes called ''cole ...

s and fruit tree

A fruit tree is a tree which bears fruit that is consumed or used by animals and humans — all trees that are flowering plants produce fruit, which are the ripened ovary (plants), ovaries of flowers containing one or more seeds. In hortic ...

s. Gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "... Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a b ...

s from ''B. thuringiensis'' have also been incorporated into transgenic crops

Genetically modified crops (GM crops) are plants used in agriculture, the DNA of which has been modified using genetic engineering methods. Plant genomes can be engineered by physical methods or by use of '' Agrobacterium'' for the delivery of ...

, making the plants express some of the bacterium's toxins, which are protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respon ...

s. These confer resistance to insect pests and thus reduce the necessity for pesticide use. If pests develop resistance to the toxins in these crops, ''B. thuringiensis'' will become useless in organic farming also.

The bacterium '' Paenibacillus popilliae'' which causes milky spore disease has been found useful in the control of Japanese beetle

The Japanese beetle (''Popillia japonica'') is a species of scarab beetle. The adult measures in length and in width, has iridescent copper-colored elytra and a green thorax and head. It is not very destructive in Japan (where it is control ...

, killing the larvae. It is very specific to its host species and is harmless to vertebrates and other invertebrates.

''Bacillus

''Bacillus'' (Latin "stick") is a genus of Gram-positive, rod-shaped bacteria, a member of the phylum '' Bacillota'', with 266 named species. The term is also used to describe the shape (rod) of other so-shaped bacteria; and the plural ''Bacil ...

'' spp.,p.94-5, II. Biocontrol Modes of Action fluorescent Pseudomonads, and Streptomycete

The ''Streptomycetaceae'' are a family of ''Actinomycetota'', making up the monotypic order ''Streptomycetales''. It includes the important genus ''Streptomyces''. This was the original source of many antibiotics, namely streptomycin, the first a ...

s are controls of various fungal pathogens.p.94

Fungi

Entomopathogenic fungi, which cause disease in insects, include at least 14 species that attack

Entomopathogenic fungi, which cause disease in insects, include at least 14 species that attack aphid

Aphids are small sap-sucking insects and members of the superfamily Aphidoidea. Common names include greenfly and blackfly, although individuals within a species can vary widely in color. The group includes the fluffy white woolly aphids. A ...

s. '' Beauveria bassiana'' is mass-produced and used to manage a wide variety of insect pests including whiteflies

Whiteflies are Hemipterans that typically feed on the undersides of plant leaves. They comprise the family Aleyrodidae, the only family in the superfamily Aleyrodoidea. More than 1550 species have been described.

Description and taxonomy

The ...

, thrips

Thrips (order Thysanoptera) are minute (mostly long or less), slender insects with fringed wings and unique asymmetrical mouthparts. Different thrips species feed mostly on plants by puncturing and sucking up the contents, although a few are ...

, aphids and weevils. '' Lecanicillium'' spp. are deployed against white flies, thrips and aphids. '' Metarhizium'' spp. are used against pests including beetles, locusts

Locusts (derived from the Vulgar Latin ''locusta'', meaning grasshopper) are various species of short-horned grasshoppers in the family Acrididae that have a swarming phase. These insects are usually solitary, but under certain circumst ...

and other grasshoppers, Hemiptera, and spider mite

Spider mites are members of the Tetranychidae family, which includes about 1,200 species. They are part of the subclass Acari (mites). Spider mites generally live on the undersides of leaves of plants, where they may spin protective silk webs, ...

s. ''Paecilomyces fumosoroseus

''Isaria fumosorosea'' is an entomopathogenic fungus, formerly known as ''Paecilomyces fumosoroseus''. It shows promise as a biological pesticide with an extensive host range.

Life cycle

When a conidium or blastospore of ''Isaria fumosorosea'' ...

'' is effective against white flies, thrips and aphids; '' Purpureocillium lilacinus'' is used against root-knot nematodes, and 89 ''Trichoderma

''Trichoderma'' is a genus of fungi in the family Hypocreaceae that is present in all soils, where they are the most prevalent culturable fungi. Many species in this genus can be characterized as opportunistic avirulent plant symbionts. This ...

'' species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of ...

against certain plant pathogens.p.93 '' Trichoderma viride'' has been used against Dutch elm disease

Dutch elm disease (DED) is caused by a member of the sac fungi (Ascomycota) affecting elm trees, and is spread by elm bark beetles. Although believed to be originally native to Asia, the disease was accidentally introduced into America, Europe, ...

, and has shown some effect in suppressing silver leaf, a disease of stone fruits caused by the pathogenic fungus ''Chondrostereum purpureum

Silver leaf is a fungal disease of trees caused by the fungus plant pathogen ''Chondrostereum purpureum''. It attacks most species of the rose family Rosaceae, particularly the genus ''Prunus''. The disease is progressive and often fatal. The comm ...

''.

Pathogenic fungi may be controlled by other fungi, or bacteria or yeasts, such as: ''Gliocladium

''Gliocladium''Corda (1840) ''Icon. fung. (Prague)'' 4: 30. is an asexual fungal genus in the Hypocreaceae. Certain other species including ''Gliocladium virens'' were recently transferred to the genus ''Trichoderma'' and ''G. roseum'' became ' ...

'' spp., mycoparasitic ''Pythium

''Pythium'' is a genus of parasitic oomycetes. They were formerly classified as fungi. Most species are plant parasites, but '' Pythium insidiosum'' is an important pathogen of animals, causing pythiosis. The feet of the fungus gnat are fre ...

'' spp., binucleate

Binucleated cells are cells that contain two nuclei. This type of cell is most commonly found in cancer cells and may arise from a variety of causes. Binucleation can be easily visualized through staining and microscopy. In general, binucleation ...

types of ''Rhizoctonia

''Rhizoctonia'' is a genus of fungi in the order Cantharellales. Species form thin, effused, corticioid basidiocarps (fruit bodies), but are most frequently found in their sterile, anamorphic state. ''Rhizoctonia'' species are saprotrophic, bu ...

'' spp., and '' Laetisaria'' spp.

The fungi ''Cordyceps

''Cordyceps'' is a genus of ascomycete fungi (sac fungi) that includes about 600 species. Most ''Cordyceps'' species are endoparasitoids, parasitic mainly on insects and other arthropods (they are thus entomopathogenic fungi); a few are parasit ...

'' and '' Metacordyceps'' are deployed against a wide spectrum of arthropods. ''Entomophaga

''Entomophaga'' is a genus of flies in the family Tachinidae. It was reviewed by T. Tachi and H. Shima in 2006 and was found to be paraphyletic; it was also found to form a monophyletic group with '' Proceromyia''.

Species

*'' E. exoleta'' ( Me ...

'' is effective against pests such as the green peach aphid

''Myzus persicae'', known as the green peach aphid, greenfly, or the peach-potato aphid, is a small green aphid belonging to the order Hemiptera. It is the most significant aphid pest of peach trees, causing decreased growth, shrivelling of the ...

.

Several members of Chytridiomycota

Chytridiomycota are a division of zoosporic organisms in the kingdom Fungi, informally known as chytrids. The name is derived from the Ancient Greek ('), meaning "little pot", describing the structure containing unreleased zoöspores. Chytri ...

and Blastocladiomycota have been explored as agents of biological control. From Chytridiomycota, '' Synchytrium solstitiale'' is being considered as a control agent of the yellow star thistle

''Centaurea solstitialis'', the yellow star-thistle, is a species of thorny plant in the genus '' Centaurea'', which is part of the family Asteraceae. A winter annual, it is native to the Mediterranean Basin region and invasive in many other p ...

(''Centaurea solstitialis'') in the United States.

Viruses

Baculoviruses

''Baculoviridae'' is a family of viruses. Arthropods, among the most studied being Lepidoptera, Hymenoptera and Diptera, serve as natural hosts. Currently, 85 species are placed in this family, assigned to four genera.

Baculoviruses are kno ...

are specific to individual insect host species and have been shown to be useful in biological pest control. For example, the Lymantria dispar multicapsid nuclear polyhedrosis virus has been used to spray large areas of forest in North America where larvae of the spongy moth are causing serious defoliation. The moth larvae are killed by the virus they have eaten and die, the disintegrating cadavers leaving virus particles on the foliage to infect other larvae.

A mammalian virus, the rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus was introduced to Australia to attempt to control the European rabbit

The European rabbit (''Oryctolagus cuniculus'') or coney is a species of rabbit native to the Iberian Peninsula (including Spain, Portugal, and southwestern France), western France, and the northern Atlas Mountains in northwest Africa. It h ...

populations there. It escaped from quarantine and spread across the country, killing large numbers of rabbits. Very young animals survived, passing immunity to their offspring in due course and eventually producing a virus-resistant population. Introduction into New Zealand in the 1990s was similarly successful at first, but a decade later, immunity had developed and populations had returned to pre-RHD levels.

RNA mycovirus

Mycoviruses (Ancient Greek: μύκης ' ("fungus") + Latin '), also known as mycophages, are viruses that infect fungi. The majority of mycoviruses have double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) genomes and isometric particles, but approximately 30% have pos ...

es are controls of various fungal pathogens.

Oomycota

'' Lagenidium giganteum'' is a water-borne mold that parasitizes the larval stage of mosquitoes. When applied to water, the motile spores avoid unsuitable host species and search out suitable mosquito larval hosts. This mold has the advantages of a dormant phase, resistant to desiccation, with slow-release characteristics over several years. Unfortunately, it is susceptible to many chemicals used in mosquito abatement programmes.Competitors

Thelegume

A legume () is a plant in the family Fabaceae (or Leguminosae), or the fruit or seed of such a plant. When used as a dry grain, the seed is also called a pulse. Legumes are grown agriculturally, primarily for human consumption, for livestock fo ...

vine ''Mucuna pruriens

''Mucuna pruriens'' is a tropical legume native to Africa and tropical Asia and widely naturalized and cultivated. Its English common names include monkey tamarind, velvet bean, Bengal velvet bean, Florida velvet bean, Mauritius velvet bean, Yoko ...

'' is used in the countries of Benin

Benin ( , ; french: Bénin , ff, Benen), officially the Republic of Benin (french: République du Bénin), and formerly Dahomey, is a country in West Africa. It is bordered by Togo to the west, Nigeria to the east, Burkina Faso to the nort ...

and Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making it ...

as a biological control for problematic ''Imperata cylindrica

''Imperata cylindrica'' (commonly known as cogongrass or kunai grass ) is a species of perennial rhizomatous grass native to tropical and subtropical Asia, Micronesia, Melanesia, Australia, Africa, and southern Europe. It has also been introduc ...

'' grass: the vine is extremely vigorous and suppresses neighbouring plants by out-competing them for space and light. ''Mucuna pruriens'' is said not to be invasive outside its cultivated area. ''Desmodium

''Desmodium'' is a genus of plants in the legume family Fabaceae, sometimes called tick-trefoil, tick clover, hitch hikers or beggar lice. There are dozens of species and the delimitation of the genus has shifted much over time.

These are mostly ...

uncinatum'' can be used in push-pull farming to stop the parasitic plant

A parasitic plant is a plant that derives some or all of its nutritional requirements from another living plant. They make up about 1% of angiosperms and are found in almost every biome. All parasitic plants develop a specialized organ called the ...

, witchweed (''Striga

''Striga'', commonly known as witchweed, is a genus of parasitic plants that occur naturally in parts of Africa, Asia, and Australia. It is currently classified in the family Orobanchaceae, although older classifications place it in the Scrophul ...

'').

The Australian bush fly, '' Musca vetustissima'', is a major nuisance pest in Australia, but native decomposers found in Australia are not adapted to feeding on cow dung, which is where bush flies breed. Therefore, the Australian Dung Beetle Project

The Australian Dung Beetle Project (1965–1985), conceived and led by Dr George Bornemissza of the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), was an international scientific research and biological control project with ...

(1965–1985), led by George Bornemissza

George Francis Bornemissza (born György Ferenc Bornemissza; 11 February 1924 – 10 April 2014) was a Hungarian-born entomologist and ecologist. He studied science at the University of Budapest before obtaining his Ph.D. in zoology at the Un ...

of the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation

The Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) is an Australian Government agency responsible for scientific research.

CSIRO works with leading organisations around the world. From its headquarters in Canberra, CSIRO ...

, released forty-nine species of dung beetle

Dung beetles are beetles that feed on feces. Some species of dung beetles can bury dung 250 times their own mass in one night.

Many dung beetles, known as ''rollers'', roll dung into round balls, which are used as a food source or breeding cha ...

, to reduce the amount of dung and therefore also the potential breeding sites of the fly.

Combined use of parasitoids and pathogens

In cases of massive and severe infection of invasive pests, techniques of pest control are often used in combination. An example is theemerald ash borer

The emerald ash borer (''Agrilus planipennis''), also known by the acronym EAB, is a green buprestid or jewel beetle native to north-eastern Asia that feeds on ash species. Females lay eggs in bark crevices on ash trees, and larvae feed underne ...

, ''Agrilus planipennis

The emerald ash borer (''Agrilus planipennis''), also known by the acronym EAB, is a green buprestid or jewel beetle native to north-eastern Asia that feeds on ash species. Females lay eggs in bark crevices on ash trees, and larvae feed undern ...

'', an invasive beetle

Beetles are insects that form the order Coleoptera (), in the superorder Endopterygota. Their front pair of wings are hardened into wing-cases, elytra, distinguishing them from most other insects. The Coleoptera, with about 400,000 describ ...

from China, which has destroyed tens of millions of ash trees in its introduced range in North America. As part of the campaign against it, from 2003 American scientists and the Chinese Academy of Forestry searched for its natural enemies in the wild, leading to the discovery of several parasitoid wasps, namely ''Tetrastichus planipennisi'', a gregarious larval endoparasitoid, '' Oobius agrili'', a solitary, parthenogenic egg parasitoid, and '' Spathius agrili'', a gregarious larval ectoparasitoid. These have been introduced and released into the United States of America

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territor ...

as a possible biological control of the emerald ash borer. Initial results for ''Tetrastichus planipennisi'' have shown promise, and it is now being released along with '' Beauveria bassiana'', a fungal pathogen

In biology, a pathogen ( el, πάθος, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of") in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a ger ...

with known insecticidal properties.

Target pests

Fungal pests

''Botrytis cinerea

''Botrytis cinerea'' is a necrotrophic fungus that affects many plant species, although its most notable hosts may be wine grapes. In viticulture, it is commonly known as "botrytis bunch rot"; in horticulture, it is usually called "grey mould" ...

'' on lettuce

Lettuce (''Lactuca sativa'') is an annual plant of the family Asteraceae. It is most often grown as a leaf vegetable, but sometimes for its stem and seeds. Lettuce is most often used for salads, although it is also seen in other kinds of foo ...

, by ''Fusarium

''Fusarium'' is a large genus of filamentous fungi, part of a group often referred to as hyphomycetes, widely distributed in soil and associated with plants. Most species are harmless saprobes, and are relatively abundant members of the soil ...

'' spp. and '' Penicillium claviforme'', on grape

A grape is a fruit, botanically a berry (botany), berry, of the deciduous woody vines of the flowering plant genus ''Vitis''. Grapes are a non-Climacteric (botany), climacteric type of fruit, generally occurring in clusters.

The cultivation of ...

and strawberry

The garden strawberry (or simply strawberry; ''Fragaria × ananassa'') is a widely grown hybrid species of the genus '' Fragaria'', collectively known as the strawberries, which are cultivated worldwide for their fruit. The fruit is widely a ...

by ''Trichoderma

''Trichoderma'' is a genus of fungi in the family Hypocreaceae that is present in all soils, where they are the most prevalent culturable fungi. Many species in this genus can be characterized as opportunistic avirulent plant symbionts. This ...

'' spp., on strawberry by '' Cladosporium herbarum'', on Chinese cabbage

Chinese cabbage (''Brassica rapa'', subspecies ''pekinensis'' and ''chinensis'') can refer to two cultivar groups of leaf vegetables often used in Chinese cuisine: the Pekinensis Group (napa cabbage) and the Chinensis Group ( bok choy).

These ...

by '' Bacillus brevis'', and on various other crops by various yeasts and bacteria. '' Sclerotinia sclerotiorum'' by several fungal biocontrols. Fungal pod infection of snap bean by '' Trichoderma hamatum'' if before or concurrent with infection.p.93-4 ''Cryphonectria parasitica

The pathogenic fungus ''Cryphonectria parasitica'' (formerly ''Endothia parasitica'') is a member of the Ascomycota (sac fungi). This necrotrophic fungus is native to East Asia and South East Asia and was introduced into Europe and North America ...

'', '' Gaeumannomyces graminis'', '' Sclerotinia'' spp., and ''Ophiostoma novo-ulmi

''Ophiostoma'' is a genus of fungi within the family Ophiostomataceae. It was circumscribed in 1919 by mycologists Hans Sydow and Paul Sydow.

Species

*'' Ophiostoma adjuncti''

*''Ophiostoma ainoae''

*'' Ophiostoma allantosporum''

*'' Ophiostoma ...

'' by viruses. Various powdery mildew

Powdery mildew is a fungal disease that affects a wide range of plants. Powdery mildew diseases are caused by many different species of ascomycete fungi in the order Erysiphales. Powdery mildew is one of the easier plant diseases to identify, as ...

s and rust

Rust is an iron oxide, a usually reddish-brown oxide formed by the reaction of iron and oxygen in the catalytic presence of water or air moisture. Rust consists of hydrous iron(III) oxides (Fe2O3·nH2O) and iron(III) oxide-hydroxide (FeO(OH), ...

s by various ''Bacillus

''Bacillus'' (Latin "stick") is a genus of Gram-positive, rod-shaped bacteria, a member of the phylum '' Bacillota'', with 266 named species. The term is also used to describe the shape (rod) of other so-shaped bacteria; and the plural ''Bacil ...

'' spp. and fluorescent Pseudomonads. ''Colletotrichum orbiculare

''Colletotrichum orbiculare'' is a plant pathogen of melons and cucumber. It causes the disease anthracnose that can effect curcubits causing lesions on various parts of the plant. It can effect cucumbers, melon, squash, watermelon and pumpkin, ...

'' will suppress further infection by itself if manipulated to produce plant-induced systemic resistance by infected the lowest leaf.p.95-6

Difficulties

Many of the most important pests are exotic, invasive species that severely impact agriculture, horticulture, forestry, and urban environments. They tend to arrive without their co-evolved parasites, pathogens and predators, and by escaping from these, populations may soar. Importing the natural enemies of these pests may seem a logical move but this may haveunintended consequences

In the social sciences, unintended consequences (sometimes unanticipated consequences or unforeseen consequences) are outcomes of a purposeful action that are not intended or foreseen. The term was popularised in the twentieth century by Ameri ...

; regulations may be ineffective and there may be unanticipated effects on biodiversity, and the adoption of the techniques may prove challenging because of a lack of knowledge among farmers and growers.

Side effects

Biological control can affectbiodiversity

Biodiversity or biological diversity is the variety and variability of life on Earth. Biodiversity is a measure of variation at the genetic ('' genetic variability''), species ('' species diversity''), and ecosystem ('' ecosystem diversity' ...

through predation, parasitism, pathogenicity, competition, or other attacks on non-target species. An introduced control does not always target only the intended pest species; it can also target native species. In Hawaii during the 1940s parasitic wasps were introduced to control a lepidopteran pest and the wasps are still found there today. This may have a negative impact on the native ecosystem; however, host range and impacts need to be studied before declaring their impact on the environment.

Vertebrate animals tend to be generalist feeders, and seldom make good biological control agents; many of the classic cases of "biocontrol gone awry" involve vertebrates. For example, the

Vertebrate animals tend to be generalist feeders, and seldom make good biological control agents; many of the classic cases of "biocontrol gone awry" involve vertebrates. For example, the cane toad