Benjamin Huger (general) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Benjamin Huger (November 22, 1805 – December 7, 1877) was a regular officer in the

Huger fought notably in 1846–48 during the Mexican–American War, serving as chief of ordnance on the staff of Maj. Gen.

Huger fought notably in 1846–48 during the Mexican–American War, serving as chief of ordnance on the staff of Maj. Gen.

In early 1862

In early 1862  Due to the combination of the naval action at Elizabeth City on February 10, the Battle of New Bern on March 14, the Battle of South Mills on April 19, and other Union landings during the Peninsula Campaign, Confederate authorities determined Huger could not hold Norfolk. On April 27 he was ordered by Gen. Joseph E. Johnston to abandon the area, salvaging from Gosport Navy Yard as much usable equipment as he could, and join the main army. On May 1 Huger began to evacuate his men and ordered the destruction by fire of the naval yards at both Norfolk as well as nearby

Due to the combination of the naval action at Elizabeth City on February 10, the Battle of New Bern on March 14, the Battle of South Mills on April 19, and other Union landings during the Peninsula Campaign, Confederate authorities determined Huger could not hold Norfolk. On April 27 he was ordered by Gen. Joseph E. Johnston to abandon the area, salvaging from Gosport Navy Yard as much usable equipment as he could, and join the main army. On May 1 Huger began to evacuate his men and ordered the destruction by fire of the naval yards at both Norfolk as well as nearby

According to Johnston's battle plan, Huger's three

According to Johnston's battle plan, Huger's three

Lee continued to order his army to pursue and destroy the Union forces. Following the action at Oak Grove, he pulled much of the defense around Richmond and added them to the chase, Huger's division included. On June 29, Magruder thought his position was to be attacked by overwhelming numbers and asked for reinforcements. Lee sent two brigades from Huger's division in response with instructions they were to be returned at 2 p.m. if Magruder was not hit by then. The appointed hour came and passed, Huger's men were sent back, and later that day Magruder "halfheartedly" fought the

Lee continued to order his army to pursue and destroy the Union forces. Following the action at Oak Grove, he pulled much of the defense around Richmond and added them to the chase, Huger's division included. On June 29, Magruder thought his position was to be attacked by overwhelming numbers and asked for reinforcements. Lee sent two brigades from Huger's division in response with instructions they were to be returned at 2 p.m. if Magruder was not hit by then. The appointed hour came and passed, Huger's men were sent back, and later that day Magruder "halfheartedly" fought the  The following day, July 1, turned out to be Huger's last fight with the Army of Northern Virginia as well as his final field command in the American Civil War. His division was directed toward the Union forces on

The following day, July 1, turned out to be Huger's last fight with the Army of Northern Virginia as well as his final field command in the American Civil War. His division was directed toward the Union forces on

''General Officers of the Confederate Army: Officers of the Executive Departments of the Confederate States, Members of the Confederate Congress by States''

Mattituck, NY: J. M. Carroll & Co., 1983. . First published 1911 by Neale Publishing Co.

ricehope.com

Rice Hope Plantation Inn site biography of Huger.

History Central site biography of Huger. {{DEFAULTSORT:Huger, Benjamin 1805 births 1877 deaths Military personnel from Charleston, South Carolina Confederate States Army major generals People of South Carolina in the American Civil War American military personnel of the Mexican–American War Members of the Aztec Club of 1847 United States Military Academy alumni Burials at Green Mount Cemetery

United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land warfare, land military branch, service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight Uniformed services of the United States, U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army o ...

, who served with distinction as chief of ordnance in the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Second Federal Republic of Mexico, Mexico f ...

and in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by state ...

, as a Confederate general

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". O ...

. He notably surrendered Roanoke Island

Roanoke Island () is an island in Dare County, bordered by the Outer Banks of North Carolina, United States. It was named after the historical Roanoke, a Carolina Algonquian people who inhabited the area in the 16th century at the time of Engli ...

and then the rest of the Norfolk, Virginia

Norfolk ( ) is an independent city (United States), independent city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. Incorporated in 1705, it had a population of 238,005 at the 2020 United States Census, 2020 cen ...

shipyards, attracting criticism for allowing valuable equipment to be captured. At Seven Pines Seven Pines may refer to the following places in the United States:

* Seven Pines, Virginia, in Henrico County, location of a Civil War battle and cemetery

** Battle of Seven Pines

** Seven Pines National Cemetery

* Seven Pines, Mississippi, in ...

, he was blamed by General James Longstreet

James Longstreet (January 8, 1821January 2, 1904) was one of the foremost Confederate generals of the American Civil War and the principal subordinate to General Robert E. Lee, who called him his "Old War Horse". He served under Lee as a corps c ...

for impeding the Confederate attack, and was transferred to an administrative post after a lacklustre performance in the Seven Days Battles

The Seven Days Battles were a series of seven battles over seven days from June 25 to July 1, 1862, near Richmond, Virginia, during the American Civil War. Confederate General Robert E. Lee drove the invading Union Army of the Potomac, comman ...

.

Early life and U.S. Army career

Huger was born in 1805 in Charleston, South Carolina. (He pronounced his name , although today many Charlestonians say .) He was a son of Francis Kinloch Huger and his wife Harriet Lucas Pinckney, making him a grandson of Maj. Gen.Thomas Pinckney

Thomas Pinckney (October 23, 1750November 2, 1828) was an early American statesman, diplomat, and soldier in both the American Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, achieving the rank of major general. He served as Governor of South Carolina an ...

.Dupuy, p. 354. His paternal grandfather, also named Benjamin Huger, was a patriot in the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolu ...

, killed at Charleston during the British occupation.

In 1821 Huger entered the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

at West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

and graduated four years later, standing eighth out of 37 cadets. On July 1, 1825, he was commissioned a brevet

Brevet may refer to:

Military

* Brevet (military), higher rank that rewards merit or gallantry, but without higher pay

* Brevet d'état-major, a military distinction in France and Belgium awarded to officers passing military staff college

* Aircre ...

second lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army until 1 ...

, then promoted to second lieutenant in the 3rd U.S. Artillery on that same date.Eicher, ''CW High Commands'', p. 308. He served as a topographical engineer until 1828, when he took a leave of absence from the Army to visit Europe from 1828 to 1830. He then was on recruiting duty, after which he served as part of Fort Trumbull

Fort Trumbull is a fort near the mouth of the Thames River on Long Island Sound in New London, Connecticut and named for Governor Jonathan Trumbull. The original fort was built in 1777, but the present fortification was built between 1839 and ...

's garrison in New London, Connecticut

New London is a seaport city and a port of entry on the northeast coast of the United States, located at the mouth of the Thames River in New London County, Connecticut. It was one of the world's three busiest whaling ports for several decades ...

. From 1832 to 1839 Huger commanded the Fortress Monroe

Fort Monroe, managed by partnership between the Fort Monroe Authority for the Commonwealth of Virginia, the National Park Service as the Fort Monroe National Monument, and the City of Hampton, is a former military installation in Hampton, Virgi ...

arsenal

An arsenal is a place where arms and ammunition are made, maintained and repaired, stored, or issued, in any combination, whether privately or publicly owned. Arsenal and armoury (British English) or armory (American English) are mostly ...

located in Hampton, Virginia

Hampton () is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. As of the 2020 census, the population was 137,148. It is the 7th most populous city in Virginia and 204th most populous city in the nation. Hampton ...

.

On February 7, 1831, Huger married his first cousin, Elizabeth Celestine Pinckney. They would have five children together; Benjamin, Eustis, Francis, Thomas Pinckney and Celestine Pinckney. One of his sons, Francis (Frank) Kinloch Huger, also attended West Point and graduated in 1860. Frank Huger

Francis Huger (1837-1897), a son of Gen Benjamin Huger, served as a Confederate artilleryman in the American Civil War.

Pre-war

Francis (Frank) Kinloch Huger, a son of Benjamin Huger and Elizabeth Celestine Pinckney, was born in Norfolk, Virg ...

would enter the Confederate forces during the American Civil War as well, rising to the rank of lieutenant colonel and leading a battalion

A battalion is a military unit, typically consisting of 300 to 1,200 soldiers commanded by a lieutenant colonel, and subdivided into a number of companies (usually each commanded by a major or a captain). In some countries, battalions are ...

of field artillery

Field artillery is a category of mobile artillery used to support armies in the field. These weapons are specialized for mobility, tactical proficiency, short range, long range, and extremely long range target engagement.

Until the early 20 ...

by the end of the conflict. On May 30, 1832, Huger was transferred to the Army's ordnance department with the rank of captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

; he would spend the rest of his U.S. Army career with this branch. From 1839 to 1846 he served as a member of the U.S. Army Ordnance Board, and from 1840 into 1841 he was on official duty in Europe. Huger again commanded the Fort Monroe Arsenal from 1841 to 1846, until hostilities began with Mexico

Mexico ( Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guate ...

.

War with Mexico

Huger fought notably in 1846–48 during the Mexican–American War, serving as chief of ordnance on the staff of Maj. Gen.

Huger fought notably in 1846–48 during the Mexican–American War, serving as chief of ordnance on the staff of Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as a general in the United States Army from 1814 to 1861, taking part in the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the early s ...

throughout the conflict. Huger had command of the siege train during the Siege of Veracruz

The Battle of Veracruz was a 20-day siege of the key Mexican beachhead seaport of Veracruz during the Mexican–American War. Lasting from March 9–29, 1847, it began with the first large-scale amphibious assault conducted by United States ...

, March 9–29, 1847. He was appointed to the rank of brevet major for his performance at the Veracruz on March 29, and to lieutenant colonel for the Battle of Molino del Rey

The Battle of Molino del Rey (8 September 1847) was one of the bloodiest engagements of the Mexican–American War as part of the Battle for Mexico City. It was fought in September 1847 between Mexican forces under General Antonio León against ...

on September 8. Huger was brevetted a colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge ...

five days later for "gallant and meritorious conduct" during the storming of Chapultepec

Chapultepec, more commonly called the "Bosque de Chapultepec" (Chapultepec Forest) in Mexico City, is one of the largest city parks in Mexico, measuring in total just over 686 hectares (1,695 acres). Centered on a rock formation called Chapultep ...

.

Returning from Mexico, Huger was appointed to a board which created an instructional system for teaching artillery principles in the US Army. From 1848 to 1851 he once more commanded the arsenal at Fort Monroe, and then led the arsenal at Harpers Ferry

Harpers Ferry is a historic town in Jefferson County, West Virginia. It is located in the lower Shenandoah Valley. The population was 285 at the 2020 census. Situated at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers, where the U.S. state ...

until 1854. During 1852 his home state presented him with a sword, commemorating Huger's long and distinguished service to South Carolina. From 1854 to 1860, he commanded the arsenal located at Pikesville in Baltimore County, Maryland

Baltimore County ( , locally: or ) is the third-most populous county in the U.S. state of Maryland and is part of the Baltimore metropolitan area. Baltimore County (which partially surrounds, though does not include, the independent City of ...

, during which he was promoted to major as of February 15, 1855. Huger was then sent to the Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included t ...

as an official foreign observer in 1856. Beginning in 1860, Huger commanded the Charleston Arsenal, holding the post until resigning in the spring of 1861.

American Civil War service

Despite thesecession

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics l ...

of his home state in December 1860, Huger remained in the U.S. Army until after the Battle of Fort Sumter

The Battle of Fort Sumter (April 12–13, 1861) was the bombardment of Fort Sumter near Charleston, South Carolina by the South Carolina militia. It ended with the surrender by the United States Army, beginning the American Civil War.

Foll ...

, resigning effective April 22, 1861. Just prior to the battle, Huger traveled to the fort and conferred with its commander, Maj. Robert Anderson, to determine where he stood. Although Anderson was also Southern-born, he had already chosen to follow the Union cause, and Huger left when "their discussions came to naught."

Huger was commissioned an infantry lieutenant colonel in the regular Confederate Army

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fighti ...

on March 16, and then briefly commanded the forces in and around Norfolk, Virginia. On May 22 he was appointed a brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed t ...

in the state's militia, and the next day took command of the Department of Norfolk, with defensive responsibilities for North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia a ...

and southern Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the East Coast of the United States, Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography an ...

, with his headquarters located at Norfolk. Sometime that June he was also commissioned a brigadier in the Virginia Provisional Army, however Huger entered the Confederate volunteer forces on June 17 as a brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed t ...

. Later on October 7 he was promoted to the rank of major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

.

Roanoke Island and the loss of Norfolk

In early 1862

In early 1862 Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union of the collective states. It proved essential to th ...

and Navy

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and related functions. It include ...

forces approached the North Carolina-Virginia coastline and Huger's area of responsibility. At Roanoke Island

Roanoke Island () is an island in Dare County, bordered by the Outer Banks of North Carolina, United States. It was named after the historical Roanoke, a Carolina Algonquian people who inhabited the area in the 16th century at the time of Engli ...

his subordinate, Brig. Gen. Henry A. Wise, asked Huger for a variety of supplies, ammunition, field artillery, and most importantly additional men, greatly fearing an attack on his quite unfinished defenses. Huger's response to Wise asked him to rely on "hard work and coolness among the troops you have, instead of more men." Eventually Confederate President

The president of the Confederate States was the head of state and head of government of the Confederate States. The president was the chief executive of the federal government and was the commander-in-chief of the Confederate Army and the Confed ...

Jefferson Davis did order Huger to send help to the Roanoke Island area, but it proved too late. On February 7–8 Flag Officer

A flag officer is a commissioned officer in a nation's armed forces senior enough to be entitled to fly a flag to mark the position from which the officer exercises command.

The term is used differently in different countries:

*In many countr ...

Louis M. Goldsborough and his gunboats landed Brig. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside's infantry, initiating the Battle of Roanoke Island

The opening phase of what came to be called the Burnside Expedition, the Battle of Roanoke Island was an amphibious operation of the American Civil War, fought on February 7–8, 1862, in the North Carolina Sounds a short distance south of the ...

. Huger, having about 13,000 soldiers, failed to reinforce the immediate commanders there, an ailing Wise and Col. H. M. Shaw

H is the eighth letter of the Latin alphabet.

H may also refer to:

Musical symbols

* H number, Harry Halbreich reference mechanism for music by Honegger and Martinů

* H, B (musical note)

* H, B major

People

* H. (noble) (died after 1 ...

, and Burnside quickly eliminated the Confederate resistance and forced a surrender.

When news of the fall of Roanoke Island reached the population of Norfolk they quickly panicked, spreading the alarm to Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, a ...

. Military historian Shelby Foote

Shelby Dade Foote Jr. (November 17, 1916 – June 27, 2005) was an American writer, historian and journalist. Although he primarily viewed himself as a novelist, he is now best known for his authorship of '' The Civil War: A Narrative'', a three ...

believed this loss "...shook whatever confidence the citizens had managed to retain in Huger, who was charged with their defense." On February 27, President Davis declared martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

in Norfolk and suspended the right of habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a recourse in law through which a person can report an unlawful detention or imprisonment to a court and request that the court order the custodian of the person, usually a prison official, t ...

, attempting to regain control, and two days later he did the same in Richmond.

Due to the combination of the naval action at Elizabeth City on February 10, the Battle of New Bern on March 14, the Battle of South Mills on April 19, and other Union landings during the Peninsula Campaign, Confederate authorities determined Huger could not hold Norfolk. On April 27 he was ordered by Gen. Joseph E. Johnston to abandon the area, salvaging from Gosport Navy Yard as much usable equipment as he could, and join the main army. On May 1 Huger began to evacuate his men and ordered the destruction by fire of the naval yards at both Norfolk as well as nearby

Due to the combination of the naval action at Elizabeth City on February 10, the Battle of New Bern on March 14, the Battle of South Mills on April 19, and other Union landings during the Peninsula Campaign, Confederate authorities determined Huger could not hold Norfolk. On April 27 he was ordered by Gen. Joseph E. Johnston to abandon the area, salvaging from Gosport Navy Yard as much usable equipment as he could, and join the main army. On May 1 Huger began to evacuate his men and ordered the destruction by fire of the naval yards at both Norfolk as well as nearby Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city status in the United Kingdom, city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is admi ...

. Ten days later Union forces occupied the Gosport Yards. Military historian Webb Garrison, Jr. believed Huger did not leave the area properly, stating: "...the evacuation of Norfolk was handled poorly by Confederate Gen. Benjamin Huger—too much property was left intact." Also lost as a result was the famous Ironclad warship

An ironclad is a steam engine, steam-propelled warship protected by Wrought iron, iron or steel iron armor, armor plates, constructed from 1859 to the early 1890s. The ironclad was developed as a result of the vulnerability of wooden warships ...

''CSS Virginia

CSS ''Virginia'' was the first steam-powered ironclad warship built by the Confederate States Navy during the first year of the American Civil War; she was constructed as a casemate ironclad using the razéed (cut down) original lower hull a ...

'', scuttled by her own crew when she could not stay in the James River

The James River is a river in the U.S. state of Virginia that begins in the Appalachian Mountains and flows U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed April 1, 2011 to Ches ...

, get past Union Naval forces at its mouth, nor survive at sea even if it did. The Union would control the facilities at Norfolk for the rest of the war, and the Confederate Congress

The Confederate States Congress was both the provisional and permanent legislative assembly of the Confederate States of America that existed from 1861 to 1865. Its actions were for the most part concerned with measures to establish a new nat ...

soon began to investigate Huger's part in the defeat at Roanoke Island. He led his soldiers to Petersburg

Petersburg, or Petersburgh, may refer to:

Places Australia

*Petersburg, former name of Peterborough, South Australia

Canada

* Petersburg, Ontario

Russia

*Saint Petersburg, sometimes referred to as Petersburg

United States

*Peterborg, U.S. Virg ...

, where he remained until summoned by Johnston at the end of May.

Peninsula Campaign

Confederate President Jefferson Davis assigned Huger to divisional command under Gen. Johnston within theArmy of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was the primary military force of the Confederate States of America in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most o ...

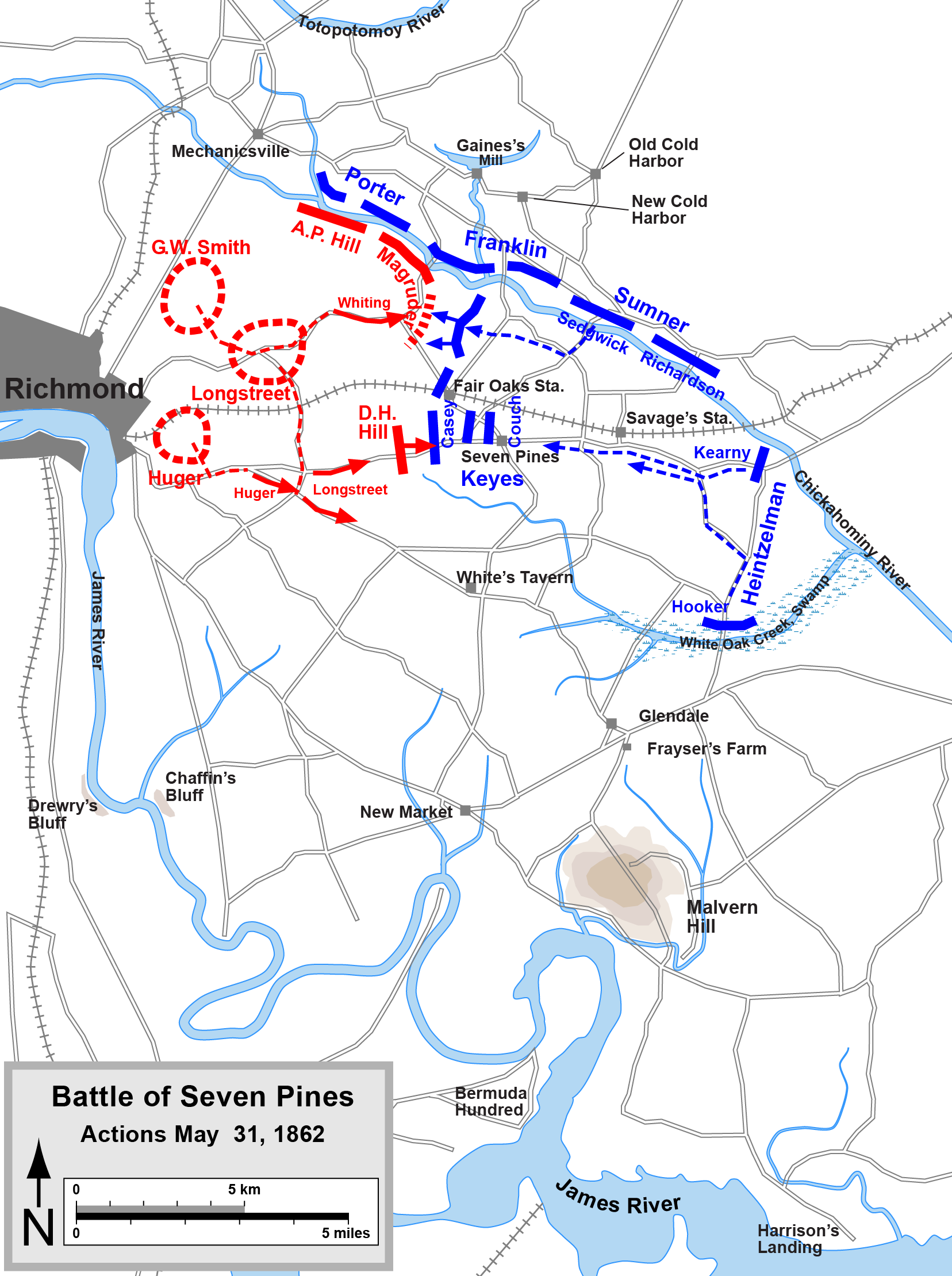

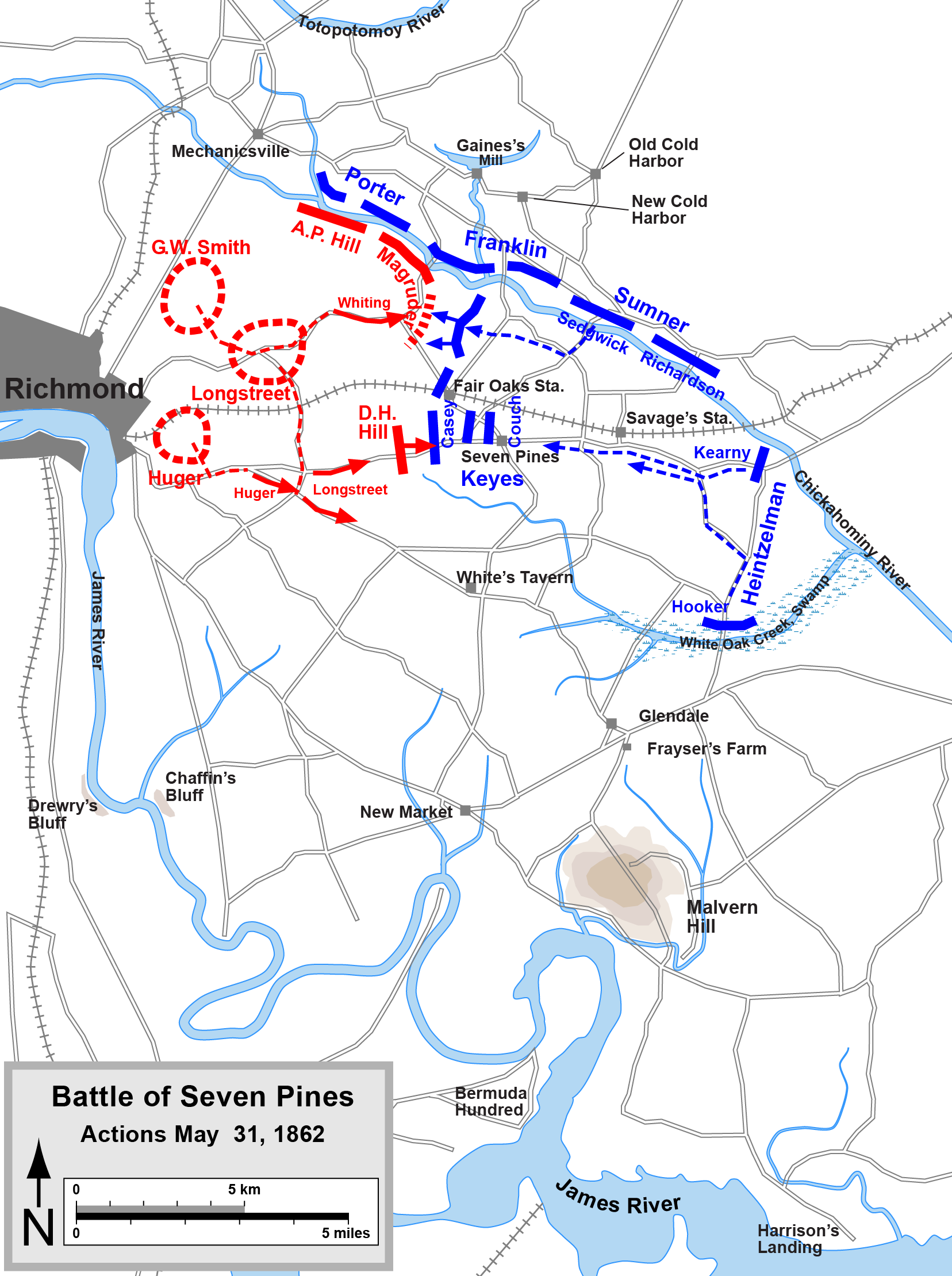

. His command fell back with the main body as Johnston retired towards Richmond, and then participated in the Battle of Seven Pines

The Battle of Seven Pines, also known as the Battle of Fair Oaks or Fair Oaks Station, took place on May 31 and June 1, 1862, in Henrico County, Virginia, nearby Sandston, as part of the Peninsula Campaign of the American Civil War. It was th ...

on May 31 and June 1, 1862.Fredriksen, p. 694.

According to Johnston's battle plan, Huger's three

According to Johnston's battle plan, Huger's three brigade

A brigade is a major tactical military formation that typically comprises three to six battalions plus supporting elements. It is roughly equivalent to an enlarged or reinforced regiment. Two or more brigades may constitute a division. ...

s were placed under the command of Maj. Gen. James Longstreet

James Longstreet (January 8, 1821January 2, 1904) was one of the foremost Confederate generals of the American Civil War and the principal subordinate to General Robert E. Lee, who called him his "Old War Horse". He served under Lee as a corps c ...

as a support, but Huger was never notified of this. On June 1 as he moved his men toward the fight, their march was blocked by Longstreet's columns—who had taken an incorrect road—and halted. Huger found Longstreet, asked about the delay, and for the first time learned his role and the command relationship. Huger then asked whether he or Longstreet was the senior officer and was told that Longstreet was, which he accepted as true although it was not. This delay and Longstreet's instructions to stand by and wait for orders prevented Huger's division from supporting the advance on time and hampered the overall Confederate attack. In his official report of the Battle of Seven Pines, Longstreet unjustly blamed Huger for the less than completely successful action, complaining of his tardiness on May 31 but not relating the reason for the delay. In a private letter to an injured Johnston written on June 7, Longstreet stated:

Once he learned he had been criticized and blamed, Huger asked Johnston to investigate; however this was refused. He then asked President Davis to order a court-martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of mem ...

, but, although approved, it never took place. Writing after the war, Edward Porter Alexander stated, referring to Huger, "Indeed, it is almost tragic the way in which he became the scapegoat of this occasion."

The Seven Days

Huger then participated in several of theSeven Days Battles

The Seven Days Battles were a series of seven battles over seven days from June 25 to July 1, 1862, near Richmond, Virginia, during the American Civil War. Confederate General Robert E. Lee drove the invading Union Army of the Potomac, comman ...

with the Army of Northern Virginia, now under the command of Gen. Robert E. Lee, who replaced the wounded Johnston on June 1. Lee planned an offensive in late June against an isolated Union Army corps with the bulk of his army, leaving less than 30,000 men in the Richmond trenches to defend the Confederate capital. This force consisted of the divisions of Maj. Gens. John B. Magruder, Theophilus H. Holmes, and Huger. During the Battle of Oak Grove on June 25, his portion of the line was attacked by two divisions of the Union III Corps led by Brig. Gens. Joseph Hooker

Joseph Hooker (November 13, 1814 – October 31, 1879) was an American Civil War general for the Union, chiefly remembered for his decisive defeat by Confederate General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Chancellorsville in 1863.

Hooker had serv ...

and Philip Kearny. When part of the assault faltered in rough terrain, Huger took advantage of the confused, uneven Union line and counterattacked with the brigade of Brig. Gen. Ambrose R. Wright. After repulsing the charge, another Union force attacked Huger but was also stopped short of the line. The Battle of Oak Grove cost Huger 541 men killed and wounded, while inflicting 626 total casualties on the Union Army.

Lee continued to order his army to pursue and destroy the Union forces. Following the action at Oak Grove, he pulled much of the defense around Richmond and added them to the chase, Huger's division included. On June 29, Magruder thought his position was to be attacked by overwhelming numbers and asked for reinforcements. Lee sent two brigades from Huger's division in response with instructions they were to be returned at 2 p.m. if Magruder was not hit by then. The appointed hour came and passed, Huger's men were sent back, and later that day Magruder "halfheartedly" fought the

Lee continued to order his army to pursue and destroy the Union forces. Following the action at Oak Grove, he pulled much of the defense around Richmond and added them to the chase, Huger's division included. On June 29, Magruder thought his position was to be attacked by overwhelming numbers and asked for reinforcements. Lee sent two brigades from Huger's division in response with instructions they were to be returned at 2 p.m. if Magruder was not hit by then. The appointed hour came and passed, Huger's men were sent back, and later that day Magruder "halfheartedly" fought the Battle of Savage's Station

The Battle of Savage's Station took place on June 29, 1862, in Henrico County, Virginia, as the fourth of the Seven Days Battles ( Peninsula Campaign) of the American Civil War. The main body of the Union Army of the Potomac began a general with ...

alone. Even without those two brigades, Huger was late in reaching his assigned position on June 29, countermarching needlessly and encamping his command without engaging with the enemy. The next day Huger was ordered toward Glendale but was delayed by the retreating Union forces, who had cut trees to slow pursuit, and also by the terrain which easily allowed for ambush. Attempting to follow along the Charles City Road to his assignment, Huger had his men cut a new path through the woods with axes. This further slowed their advance, while the other Confederate commands waited for his guns to fire, which was their signal to attack. Huger informed Lee of the delay by simply stating his march was "obstructed" without further description.

Around 2 p.m. Huger's lead brigade under Brig. Gen. William Mahone

William Mahone (December 1, 1826October 8, 1895) was an American civil engineer, railroad executive, Confederate States Army general, and Virginia politician.

As a young man, Mahone was prominent in the building of Virginia's roads and railroa ...

cut a mile-long path around the Union obstacles, winning the so-called "battle of the axes" and continued to approach Glendale. There he saw the 6,000-man division of Brig. Gen. Henry W. Slocum arrayed to block his way. Huger ordered one of his artillery batteries to fire on this Union position at 2:30 p.m. but Slocum's guns answered quickly, and Huger led his 9,000 men off the road and into the woods after taking some casualties. Despite outnumbering the Union division Huger made no further attempts to reach Glendale. However his few artillery shots were interpreted by the other Confederates as the signal to attack, igniting the Battle of Glendale

The Battle of Glendale, also known as the Battle of Frayser's Farm, Frazier's Farm, Nelson's Farm, Charles City Crossroads, New Market Road, or Riddell's Shop, took place on June 30, 1862, in Henrico County, Virginia, on the sixth day of the Se ...

, although Huger and his command would not take part in the fight and camped.

The following day, July 1, turned out to be Huger's last fight with the Army of Northern Virginia as well as his final field command in the American Civil War. His division was directed toward the Union forces on

The following day, July 1, turned out to be Huger's last fight with the Army of Northern Virginia as well as his final field command in the American Civil War. His division was directed toward the Union forces on Malvern Hill

Malvern Hill stands on the north bank of the James River in Henrico County, Virginia, USA, about eighteen miles southeast of Richmond. On 1 July 1862, it was the scene of the Battle of Malvern Hill, one of the Seven Days Battles of the Americ ...

without a definite target, as he was told that Lee would "place him where most needed" against the position. Because Magruder had mistakenly led his command away from the battle, Huger took up his place on the Confederate right, just north of the "Crew House", with the division of Maj. Gen. D.H. Hill on his left. To give his infantry a chance to charge and break the Union line, Lee ordered a concentrated artillery barrage at Malvern Hill. One of Huger's brigades, led by Brig. Gen. Lewis Armistead, was to determine when this barrage had the desired effect and begin the assault. Before the cannonade could begin however, the Union artillery fired first and took out most of the Confederate guns. Shortly after 2:30 p.m. Armistead went in anyway, and though his men made some progress he failed to penetrate the strong defensive position. Other Confederate units made less progress and took heavy casualties, and around 4 p.m. Magruder arrived and put in two brigades—about a third of his command—behind Armistead, but he too retired with high loss. Two more of Huger's brigades—led by Brig. Gen. Ambrose R. Wright and Mahone, about 2,500 men—followed Armistead and toward Malvern Hill. Taking Union artillery and infantry fire as they advanced, Huger's men slowed and then stopped, finding a measure of protection in a nearby bluff. They had fought to about of the Union line but could go no further. Huger's last brigade under Brig. Gen. Robert Ransom managed to get within by 6 p.m. but also fell back after receiving heavy casualties in the Confederate defeat.

Following the 1862 Peninsula Campaign, Gen. Lee began to reorganize his army and eliminate ineffective division commanders, including Huger. His actions since joining the army "left much to be desired" according to military biographer Ezra J. Warner.Warner, p. 144. Other historians have also criticized Huger throughout this time: Brendon A. Rehm summarized his battle performance as "not notably successful" and John C. Fredriksen stated Huger was "lethargic" during Seven Pines as well as moved "sluggishly" during the Seven Days fights. Furthermore, the Confederate Congress held Huger accountable for the defeat at Roanoke Island. His dilatory performance also appears to have been blamed on his rather advanced age; at nearly 57, he was well above the average age of most field officers. As a result, Huger was relieved of command on July 12, 1862 along with Maj. Gen. Theophilus Holmes, another aging, ineffective division commander. and that fall was ordered to serve in the Trans-Mississippi Department

The Trans-Mississippi Department was a geographical subdivision of the Confederate States Army comprising Arkansas, Missouri, Texas, western Louisiana, Arizona Territory and the Indian Territory; i.e. all of the Confederacy west of the Mississ ...

.

Trans-Mississippi service

After the Seven Days Battles, Huger was assigned to be assistantInspector General

An inspector general is an investigative official in a civil or military organization. The plural of the term is "inspectors general".

Australia

The Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security (Australia) (IGIS) is an independent statutory o ...

of artillery and ordnance for the Army of Northern Virginia. He held this post from his relief on June 12 until August, when he was sent to the Confederate Trans-Mississippi Department. Considered too old for field command, he would spend the remainder of the war in administrative duties. Huger was made the department's inspector of artillery and ordnance on August 26, and then was promoted to command of all ordnance within the department in July 1863. This position he held until the end of the American Civil War in 1865, when he surrendered along with Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith

General Edmund Kirby Smith (May 16, 1824March 28, 1893) was a senior officer of the Confederate States Army who commanded the Trans-Mississippi Department (comprising Arkansas, Missouri, Texas, western Louisiana, Arizona Territory and the I ...

and the rest of the Confederate Trans-Mississippi forces. Huger was paroled from Shreveport

Shreveport ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Louisiana. It is the third most populous city in Louisiana after New Orleans and Baton Rouge, respectively. The Shreveport–Bossier City metropolitan area, with a population of 393,406 in 2020, is t ...

, Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a U.S. state, state in the Deep South and South Central United States, South Central regions of the United States. It is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 20th-smal ...

, on June 12 of that same year and returned to civilian life.

Huger's Trans-Mississippi service in staff positions has been rated positively by historians. Ezra J. Warner believed this area of military service was "his proper sphere" and summarized Huger's overall performance there as: "These duties he energetically and faithfully discharged until the close of the war, most of the time in the Trans-Mississippi service." Likewise

John C. Fredriksen states "He functioned capably in this office until 1863, when he rose to chief of ordnance in the Trans-Mississippi Department until the end of the war."

Postbellum

After the war, Huger became a farmer in North Carolina and then inFauquier County, Virginia

Fauquier is a county in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 census, the population was 72,972. The county seat is Warrenton.

Fauquier County is in Northern Virginia and is a part of the Washington metropolitan area.

History

In 1 ...

, finally returning in poor health to his home in Charleston, South Carolina. He was also a member of Aztec Club of 1847

The Aztec Club of 1847 is a military society founded in 1847 by United States Army officers of the Mexican–American War. It exists as a hereditary organization including members who can trace a direct lineal connection to those originally elig ...

, a social club formed just after the Mexican–American War by army officers. Huger served as its vice president from 1852 to 1867.Wakelyn, p. 242; Aztec Club of 1847 site biography of Huger He died in Charleston in December 1877 and was buried at Green Mount Cemetery

Green Mount Cemetery is a historic rural cemetery in Baltimore, Maryland, United States. Established on March 15, 1838, and dedicated on July 13, 1839, it is noted for the large number of historical figures interred in its grounds as well as many ...

located in Baltimore, Maryland

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

.

See also

*List of American Civil War generals (Confederate)

Confederate generals

__NOTOC__

*#Confederate-Assigned to duty by E. Kirby Smith, Assigned to duty by E. Kirby Smith

*#Confederate-Incomplete appointments, Incomplete appointments

*#Confederate-State militia generals, State militia generals

Th ...

*Frank Huger

Francis Huger (1837-1897), a son of Gen Benjamin Huger, served as a Confederate artilleryman in the American Civil War.

Pre-war

Francis (Frank) Kinloch Huger, a son of Benjamin Huger and Elizabeth Celestine Pinckney, was born in Norfolk, Virg ...

Notes

References

* Alexander, Edward P. ''Fighting for the Confederacy: The Personal Recollections of General Edward Porter Alexander''. Edited by Gary W. Gallagher. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1989. . * Dupuy, Trevor N., Curt Johnson, and David L. Bongard. ''The Harper Encyclopedia of Military Biography''. New York: HarperCollins, 1992. . * Editors of Time-Life Books. ''Lee Takes Command: From Seven Days to Second Bull Run''. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1984. . *Eicher, David J.

David John Eicher (born August 7, 1961) is an American editor, writer, and popularizer of astronomy and space. He has been editor-in-chief of '' Astronomy'' magazine since 2002. He is author, coauthor, or editor of 23 books on science and America ...

''The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War''. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. .

* Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher, ''Civil War High Commands.'' Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. .

* Foote, Shelby. '' The Civil War: A Narrative''. Vol. 1, ''Fort Sumter to Perryville''. New York: Random House, 1958. .

* Fredriksen, John C. ''Civil War Almanac''. New York: Checkmark Books, 2008. .

* Garrison, Webb. ''Strange Battles of the Civil War''. Nashville, TN: Cumberland House, 2001. .

* Wakelyn, Jon L. ''Biographical Dictionary of the Confederacy''. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1977. .

* Warner, Ezra J. ''Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders.'' Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959. .

* Wert, Jeffry D.

Jeffry D. Wert (born May 8, 1946) is an American historian and author specializing in the American Civil War. He has written several books on the subject, which have been published in multiple languages and countries.

Early life

Jeffry Wert's i ...

''General James Longstreet: The Confederacy's Most Controversial Soldier: A Biography''. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1993. .

* Winkler, H. Donald. ''Civil War Goats and Scapegoats''. Nashville, TN: Cumberland House Publishing, 2008. .

* Wright, Marcus J.''General Officers of the Confederate Army: Officers of the Executive Departments of the Confederate States, Members of the Confederate Congress by States''

Mattituck, NY: J. M. Carroll & Co., 1983. . First published 1911 by Neale Publishing Co.

Aztec Club of 1847

The Aztec Club of 1847 is a military society founded in 1847 by United States Army officers of the Mexican–American War. It exists as a hereditary organization including members who can trace a direct lineal connection to those originally elig ...

site biography of Huger.

ricehope.com

Rice Hope Plantation Inn site biography of Huger.

Further reading

* Rhoades, Jeffrey L. ''Scapegoat General: The Story of General Benjamin Huger, C.S.A.'' Hamden, CT: Archon Books, 1985. . * Sauers, Richard. "The Confederate Congress and the Loss of Roanoke Island." ''Civil War History'' 40, No. 2, 1994, 134–50.External links

*History Central site biography of Huger. {{DEFAULTSORT:Huger, Benjamin 1805 births 1877 deaths Military personnel from Charleston, South Carolina Confederate States Army major generals People of South Carolina in the American Civil War American military personnel of the Mexican–American War Members of the Aztec Club of 1847 United States Military Academy alumni Burials at Green Mount Cemetery