Arthropod on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Arthropods (, (gen. ποδός)) are invertebrate

The embryos of all arthropods are segmented, built from a series of repeated modules. The

The embryos of all arthropods are segmented, built from a series of repeated modules. The  The most conspicuous specialization of segments is in the head. The four major groups of arthropods –

The most conspicuous specialization of segments is in the head. The four major groups of arthropods –

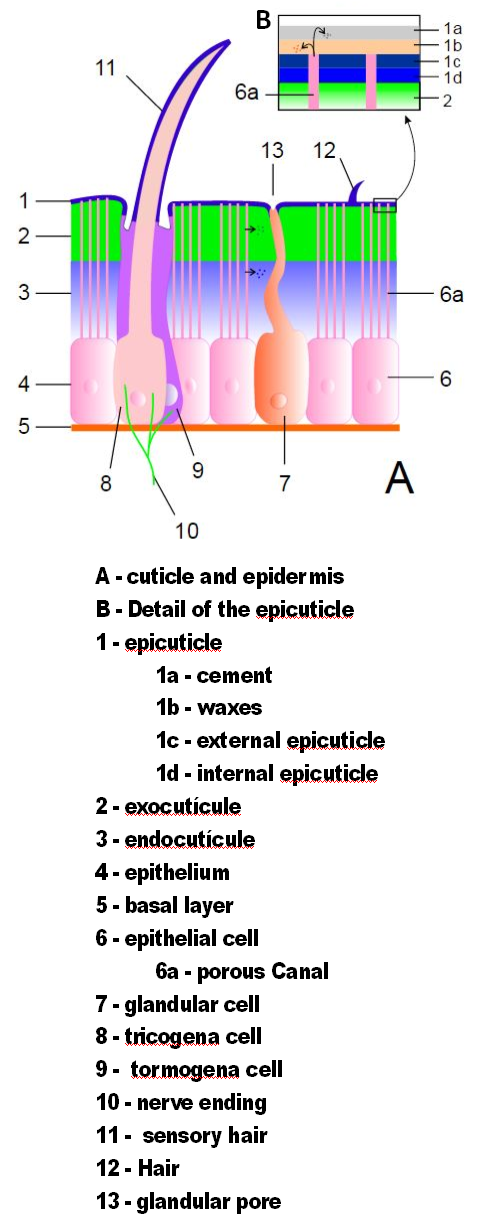

Arthropod exoskeletons are made of

Arthropod exoskeletons are made of

The exoskeleton cannot stretch and thus restricts growth. Arthropods, therefore, replace their exoskeletons by undergoing ecdysis (moulting), or shedding the old exoskeleton after growing a new one that is not yet hardened. Moulting cycles run nearly continuously until an arthropod reaches full size. Ruppert, Fox & Barnes (2004), pp. 523–524

The developmental stages between each moult (ecdysis) until sexual maturity is reached is called an instar. Differences between instars can often be seen in altered body proportions, colors, patterns, changes in the number of body segments or head width. After moulting, i.e. shedding their exoskeleton, the juvenile arthropods continue in their life cycle until they either pupate or moult again.

In the initial phase of moulting, the animal stops feeding and its epidermis releases moulting fluid, a mixture of enzymes that digests the

The exoskeleton cannot stretch and thus restricts growth. Arthropods, therefore, replace their exoskeletons by undergoing ecdysis (moulting), or shedding the old exoskeleton after growing a new one that is not yet hardened. Moulting cycles run nearly continuously until an arthropod reaches full size. Ruppert, Fox & Barnes (2004), pp. 523–524

The developmental stages between each moult (ecdysis) until sexual maturity is reached is called an instar. Differences between instars can often be seen in altered body proportions, colors, patterns, changes in the number of body segments or head width. After moulting, i.e. shedding their exoskeleton, the juvenile arthropods continue in their life cycle until they either pupate or moult again.

In the initial phase of moulting, the animal stops feeding and its epidermis releases moulting fluid, a mixture of enzymes that digests the

Most arthropods have sophisticated visual systems that include one or more usually both of

Most arthropods have sophisticated visual systems that include one or more usually both of

A few arthropods, such as

A few arthropods, such as  Most arthropods lay eggs, but scorpions are ovoviparous: they produce live young after the eggs have hatched inside the mother, and are noted for prolonged maternal care. Newly born arthropods have diverse forms, and insects alone cover the range of extremes. Some hatch as apparently miniature adults (direct development), and in some cases, such as silverfish, the hatchlings do not feed and may be helpless until after their first moult. Many insects hatch as grubs or

Most arthropods lay eggs, but scorpions are ovoviparous: they produce live young after the eggs have hatched inside the mother, and are noted for prolonged maternal care. Newly born arthropods have diverse forms, and insects alone cover the range of extremes. Some hatch as apparently miniature adults (direct development), and in some cases, such as silverfish, the hatchlings do not feed and may be helpless until after their first moult. Many insects hatch as grubs or

It has been proposed that the Ediacaran animals ''

It has been proposed that the Ediacaran animals '' The earliest fossil crustaceans date from about in the

The earliest fossil crustaceans date from about in the

From 1952 to 1977, zoologist

From 1952 to 1977, zoologist

Venomous Arthropods

chapter in United States Environmental Protection Agency and University of Florida/ Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences National Public Health Pesticide Applicator Training Manual

Arthropods – Arthropoda

Insect Life Forms {{good article Extant Cambrian first appearances

animal

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the biological kingdom Animalia. With few exceptions, animals consume organic material, breathe oxygen, are able to move, can reproduce sexually, and go through an ontogenetic stage in ...

s with an exoskeleton, a segmented body, and paired jointed appendages. Arthropods form the phylum Arthropoda. They are distinguished by their jointed limbs and cuticle

A cuticle (), or cuticula, is any of a variety of tough but flexible, non-mineral outer coverings of an organism, or parts of an organism, that provide protection. Various types of "cuticle" are non- homologous, differing in their origin, structu ...

made of chitin, often mineralised with calcium carbonate. The arthropod body plan

A body plan, ( ), or ground plan is a set of morphological features common to many members of a phylum of animals. The vertebrates share one body plan, while invertebrates have many.

This term, usually applied to animals, envisages a "blueprin ...

consists of segments, each with a pair of appendages. Arthropods are bilaterally symmetrical and their body possesses an external skeleton

An exoskeleton (from Greek ''éxō'' "outer" and ''skeletós'' "skeleton") is an external skeleton that supports and protects an animal's body, in contrast to an internal skeleton (endoskeleton) in for example, a human. In usage, some of the l ...

. In order to keep growing, they must go through stages of moulting, a process by which they shed their exoskeleton to reveal a new one. Some species have wings. They are an extremely diverse group, with up to 10 million species.

The haemocoel

The blood circulatory system is a system of organs that includes the heart, blood vessels, and blood which is circulated throughout the entire body of a human or other vertebrate. It includes the cardiovascular system, or vascular system, tha ...

, an arthropod's internal cavity, through which its haemolymph – analogue of blood – circulates, accommodates its interior organs

In biology, an organ is a collection of tissues joined in a structural unit to serve a common function. In the hierarchy of life, an organ lies between tissue and an organ system. Tissues are formed from same type cells to act together in a ...

; it has an open circulatory system

The blood circulatory system is a system of organs that includes the heart, blood vessels, and blood which is circulated throughout the entire body of a human or other vertebrate. It includes the cardiovascular system, or vascular system, t ...

. Like their exteriors, the internal organs of arthropods are generally built of repeated segments. Their nervous system is "ladder-like", with paired ventral

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to unambiguously describe the anatomy of animals, including humans. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. This position prov ...

nerve cords running through all segments and forming paired ganglia in each segment. Their heads are formed by fusion of varying numbers of segments, and their brains are formed by fusion of the ganglia of these segments and encircle the esophagus. The respiratory

The respiratory system (also respiratory apparatus, ventilatory system) is a biological system consisting of specific organs and structures used for gas exchange in animals and plants. The anatomy and physiology that make this happen varies gre ...

and excretory

Excretion is a process in which metabolic waste

is eliminated from an organism. In vertebrates this is primarily carried out by the lungs, kidneys, and skin. This is in contrast with secretion, where the substance may have specific tasks after le ...

systems of arthropods vary, depending as much on their environment as on the subphylum to which they belong.

Arthropods use combinations of compound eye

A compound eye is a visual organ found in arthropods such as insects and crustaceans. It may consist of thousands of ommatidia, which are tiny independent photoreception units that consist of a cornea, lens, and photoreceptor cells which disti ...

s and pigment-pit ocelli for vision. In most species, the ocelli can only detect the direction from which light is coming, and the compound eyes are the main source of information, but the main eyes of spiders are ocelli that can form images and, in a few cases, can swivel to track prey. Arthropods also have a wide range of chemical and mechanical sensors, mostly based on modifications of the many bristles known as setae that project through their cuticles. Similarly, their reproduction and development are varied; all terrestrial species use internal fertilization, but this is sometimes by indirect transfer of the sperm via an appendage or the ground, rather than by direct injection. Aquatic species use either internal or external fertilization. Almost all arthropods lay eggs, but many species give birth to live young after the eggs have hatched inside the mother, and a few are genuinely viviparous, such as aphid

Aphids are small sap-sucking insects and members of the superfamily Aphidoidea. Common names include greenfly and blackfly, although individuals within a species can vary widely in color. The group includes the fluffy white woolly aphids. A t ...

s. Arthropod hatchlings vary from miniature adults to grubs and caterpillar

Caterpillars ( ) are the larval stage of members of the order Lepidoptera (the insect order comprising butterflies and moths).

As with most common names, the application of the word is arbitrary, since the larvae of sawflies (suborder Symph ...

s that lack jointed limbs and eventually undergo a total metamorphosis to produce the adult form. The level of maternal care for hatchlings varies from nonexistent to the prolonged care provided by social insects

Eusociality (from Greek εὖ ''eu'' "good" and social), the highest level of organization of sociality, is defined by the following characteristics: cooperative brood care (including care of offspring from other individuals), overlapping generat ...

.

The evolutionary ancestry of arthropods dates back to the Cambrian

The Cambrian Period ( ; sometimes symbolized Ꞓ) was the first geological period of the Paleozoic Era, and of the Phanerozoic Eon. The Cambrian lasted 53.4 million years from the end of the preceding Ediacaran Period 538.8 million years ago ( ...

period. The group is generally regarded as monophyletic, and many analyses support the placement of arthropods with cycloneuralia

Cycloneuralia is a clade of ecdysozoan animals including the Scalidophora (Kinorhynchans, Loriciferans, Priapulids) and the Nematoida (nematodes, Nematomorphs). It may be paraphyletic, or may be a sister group to Panarthropoda. Or perhaps Pa ...

ns (or their constituent clades) in a superphylum Ecdysozoa. Overall, however, the basal relationships of animals are not yet well resolved. Likewise, the relationships between various arthropod groups are still actively debated. Today, Arthropods contribute to the human food supply both directly as food, and more importantly, indirectly as pollinators

A pollinator is an animal that moves pollen from the male anther of a flower to the female carpel, stigma of a flower. This helps to bring about fertilization of the ovules in the flower by the male gametes from the pollen grains.

Insects are ...

of crops. Some species are known to spread severe disease to humans, livestock, and crops.

Etymology

The word ''arthropod'' comes from the Greek ''árthron'', " joint", and ''pous'' (gen.

The Book of Genesis (from Greek ; Hebrew: בְּרֵאשִׁית ''Bəreʾšīt'', "In hebeginning") is the first book of the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament. Its Hebrew name is the same as its first word, ( "In the beginning"). ...

''podos (ποδός)''), i.e. "foot" or "leg

A leg is a weight-bearing and locomotive anatomical structure, usually having a columnar shape. During locomotion, legs function as "extensible struts". The combination of movements at all joints can be modeled as a single, linear element c ...

", which together mean "jointed leg". The designation "Arthropoda" was coined in 1848 by the German physiologist and zoologist Karl Theodor Ernst von Siebold

Prof Karl (Carl) Theodor Ernst von Siebold FRS(For) HFRSE (16 February 1804 – 7 April 1885) was a German physiologist and zoologist. He was responsible for the introduction of the taxa Arthropoda and Rhizopoda, and for defining the taxon Protoz ...

(1804–1885).

In common parlance, terrestrial arthropods are often called bugs. The term is also occasionally extended to colloquial names for freshwater or marine crustaceans (e.g. Balmain bug Balmain may refer to:

Places

* Balmain, New South Wales, a suburb of Sydney, Australia

* Electoral district of Balmain, an electoral division in New South Wales, Australia

* Balmain East, New South Wales, a suburb of Sydney, Australia

* Balmain H ...

, Moreton Bay bug

''Thenus orientalis'' is a species of slipper lobster from the Indian and Pacific oceans.

''T. orientalis'' is known by a number of common names. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization prefers the name flathead lobster, while t ...

, mudbug

Crayfish are freshwater crustaceans belonging to the clade Astacidea, which also contains lobsters. In some locations, they are also known as crawfish, craydids, crawdaddies, crawdads, freshwater lobsters, mountain lobsters, rock lobsters, mu ...

) and used by physicians and bacteriologists for disease-causing germs (e.g. superbug

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) occurs when microbes evolve mechanisms that protect them from the effects of antimicrobials. All classes of microbes can evolve resistance. Fungi evolve antifungal resistance. Viruses evolve antiviral resistance. P ...

s), but entomologists reserve this term for a narrow category of "true bugs

Hemiptera (; ) is an order of insects, commonly called true bugs, comprising over 80,000 species within groups such as the cicadas, aphids, planthoppers, leafhoppers, assassin bugs, bed bugs, and shield bugs. They range in size from to aroun ...

", insects of the order Hemiptera

Hemiptera (; ) is an order of insects, commonly called true bugs, comprising over 80,000 species within groups such as the cicadas, aphids, planthoppers, leafhoppers, assassin bugs, bed bugs, and shield bugs. They range in size from to aroun ...

(which does not include ants, bees, beetles, butterflies or moths).

Description

Arthropods are invertebrates with segmented bodies and jointed limbs. The exoskeleton orcuticle

A cuticle (), or cuticula, is any of a variety of tough but flexible, non-mineral outer coverings of an organism, or parts of an organism, that provide protection. Various types of "cuticle" are non- homologous, differing in their origin, structu ...

s consists of chitin, a polymer of glucosamine

Glucosamine (C6H13NO5) is an amino sugar and a prominent precursor in the biochemical synthesis of glycosylated proteins and lipids. Glucosamine is part of the structure of two polysaccharides, chitosan and chitin. Glucosamine is one of the most ...

. The cuticle of many crustaceans, beetle mites, and millipedes (except for bristly millipedes) is also biomineralized with calcium carbonate. Calcification of the endosternite, an internal structure used for muscle attachments, also occur in some opiliones

The Opiliones (formerly Phalangida) are an order of arachnids colloquially known as harvestmen, harvesters, harvest spiders, or daddy longlegs. , over 6,650 species of harvestmen have been discovered worldwide, although the total number of ext ...

.

Diversity

Estimates of the number of arthropod species vary between 1,170,000 and 5 to 10 million and account for over 80 percent of all known living animal species. The number of species remains difficult to determine. This is due to the census modeling assumptions projected onto other regions in order to scale up from counts at specific locations applied to the whole world. A study in 1992 estimated that there were 500,000 species of animals and plants in Costa Rica alone, of which 365,000 were arthropods. They are important members of marine, freshwater, land and air ecosystems, and are one of only two major animal groups that have adapted to life in dry environments; the other isamniote

Amniotes are a clade of tetrapod vertebrates that comprises sauropsids (including all reptiles and birds, and extinct parareptiles and non-avian dinosaurs) and synapsids (including pelycosaurs and therapsids such as mammals). They are distin ...

s, whose living members are reptiles, birds and mammals. Ruppert, Fox & Barnes (2004), pp. 518–522 One arthropod sub-group, insects, is the most species-rich member of all ecological guilds in land and freshwater environments. The lightest insects weigh less than 25 micrograms (millionths of a gram), while the heaviest weigh over . Some living malacostracan

Malacostraca (from New Latin; ) is the largest of the six classes of crustaceans, containing about 40,000 living species, divided among 16 orders. Its members, the malacostracans, display a great diversity of body forms and include crabs, lobs ...

s are much larger; for example, the legs of the Japanese spider crab

The Japanese spider crab (''Macrocheira kaempferi'') is a species of marine crab that lives in the waters around Japan. It has the largest known leg-span of any arthropod. It goes through three main larval stages along with a prezoeal stage to g ...

may span up to , with the heaviest of all living arthropods being the American lobster

The American lobster (''Homarus americanus'') is a species of lobster found on the Atlantic coast of North America, chiefly from Labrador to New Jersey. It is also known as Atlantic lobster, Canadian lobster, true lobster, northern lobster, Cana ...

, topping out at over 20 kg (44 lbs).

Segmentation

The embryos of all arthropods are segmented, built from a series of repeated modules. The

The embryos of all arthropods are segmented, built from a series of repeated modules. The last common ancestor

In biology and genetic genealogy, the most recent common ancestor (MRCA), also known as the last common ancestor (LCA) or concestor, of a set of organisms is the most recent individual from which all the organisms of the set are descended. The ...

of living arthropods probably consisted of a series of undifferentiated segments, each with a pair of appendages that functioned as limbs. However, all known living and fossil arthropods have grouped segments into tagmata in which segments and their limbs are specialized in various ways.

The three-part appearance of many insect bodies and the two-part appearance of spiders is a result of this grouping; Gould (1990), pp. 102–106 in fact there are no external signs of segmentation in mites. Arthropods also have two body elements that are not part of this serially repeated pattern of segments, an ocular somite at the front, where the mouth and eyes originated, and a telson

The telson () is the posterior-most division of the body of an arthropod. Depending on the definition, the telson is either considered to be the final segment of the arthropod body, or an additional division that is not a true segment on accou ...

at the rear, behind the anus

The anus (Latin, 'ring' or 'circle') is an opening at the opposite end of an animal's digestive tract from the mouth. Its function is to control the expulsion of feces, the residual semi-solid waste that remains after food digestion, which, de ...

.

Originally it seems that each appendage-bearing segment had two separate pairs of appendages: an upper, unsegmented exite and a lower, segmented endopod. These would later fuse into a single pair of biramous The arthropod leg is a form of jointed appendage of arthropods, usually used for walking. Many of the terms used for arthropod leg segments (called podomeres) are of Latin origin, and may be confused with terms for bones: ''coxa'' (meaning hip, plu ...

appendages united by a basal segment (protopod or basipod), with the upper branch acting as a gill while the lower branch was used for locomotion. The appendages of most crustaceans

Crustaceans (Crustacea, ) form a large, diverse arthropod taxon which includes such animals as decapods, seed shrimp, branchiopods, fish lice, krill, remipedes, isopods, barnacles, copepods, amphipods and mantis shrimp. The crustacean group c ...

and some extinct taxa such as trilobites

Trilobites (; meaning "three lobes") are extinct marine arthropods that form the class Trilobita. Trilobites form one of the earliest-known groups of arthropods. The first appearance of trilobites in the fossil record defines the base of the A ...

have another segmented branch known as exopods, but whether these structures have a single origin remain controversial. In some segments of all known arthropods the appendages have been modified, for example to form gills, mouth-parts, antennae for collecting information, or claws for grasping; arthropods are "like Swiss Army knives, each equipped with a unique set of specialized tools." In many arthropods, appendages have vanished from some regions of the body; it is particularly common for abdominal appendages to have disappeared or be highly modified.

The most conspicuous specialization of segments is in the head. The four major groups of arthropods –

The most conspicuous specialization of segments is in the head. The four major groups of arthropods – Chelicerata

The subphylum Chelicerata (from New Latin, , ) constitutes one of the major subdivisions of the phylum Arthropoda. It contains the sea spiders, horseshoe crabs, and arachnids (including harvestmen, scorpions, spiders, solifuges, ticks, and mit ...

(sea spider

Sea spiders are marine arthropods of the order Pantopoda ( ‘all feet’), belonging to the class Pycnogonida, hence they are also called pycnogonids (; named after '' Pycnogonum'', the type genus; with the suffix '). They are cosmopolitan, ...

s, horseshoe crabs and arachnid

Arachnida () is a class of joint-legged invertebrate animals (arthropods), in the subphylum Chelicerata. Arachnida includes, among others, spiders, scorpions, ticks, mites, pseudoscorpions, harvestmen, camel spiders, whip spiders and vinegaro ...

s), Myriapoda

Myriapods () are the members of subphylum Myriapoda, containing arthropods such as millipedes and centipedes. The group contains about 13,000 species, all of them terrestrial.

The fossil record of myriapods reaches back into the late Silurian, a ...

(symphylan

Symphylans, also known as garden centipedes or pseudocentipedes, are soil-dwelling arthropods of the class Symphyla in the subphylum Myriapoda. Symphylans resemble centipedes, but are very small, non-venomous, and only distantly related to bot ...

, pauropod

Pauropods are small, pale, millipede-like arthropods. Around 830 species in twelve families are found worldwide, living in soil and leaf mold. They look rather like centipedes, or millipedes, and may be a sister group of the latter. However, th ...

s, millipedes and centipede

Centipedes (from New Latin , "hundred", and Latin , "foot") are predatory arthropods belonging to the class Chilopoda (Ancient Greek , ''kheilos'', lip, and New Latin suffix , "foot", describing the forcipules) of the subphylum Myriapoda, an a ...

s), Crustacea

Crustaceans (Crustacea, ) form a large, diverse arthropod taxon which includes such animals as decapods, seed shrimp, branchiopods, fish lice, krill, remipedes, isopods, barnacles, copepods, amphipods and mantis shrimp. The crustacean group ...

(oligostracan

Oligostraca is a superclass of crustacean

Crustaceans (Crustacea, ) form a large, diverse arthropod taxon which includes such animals as decapods, seed shrimp, branchiopods, fish lice, krill, remipedes, isopods, barnacles, copepods, amph ...

s, copepod

Copepods (; meaning "oar-feet") are a group of small crustaceans found in nearly every freshwater and saltwater habitat. Some species are planktonic (inhabiting sea waters), some are benthic (living on the ocean floor), a number of species have p ...

s, malacostracan

Malacostraca (from New Latin; ) is the largest of the six classes of crustaceans, containing about 40,000 living species, divided among 16 orders. Its members, the malacostracans, display a great diversity of body forms and include crabs, lobs ...

s, branchiopod

Branchiopoda is a class of crustaceans. It comprises fairy shrimp, clam shrimp, Diplostraca (or Cladocera), Notostraca and the Devonian ''Lepidocaris''. They are mostly small, freshwater animals that feed on plankton and detritus.

Description

...

s, hexapods, etc.), and the extinct Trilobita – have heads formed of various combinations of segments, with appendages that are missing or specialized in different ways. Despite myriapods and hexapods both having similar head combinations, hexapods are deeply nested within crustacea while myriapods are not, so these traits are believed to have evolved separately. In addition, some extinct arthropods, such as ''Marrella

''Marrella'' is an extinct genus of marrellomorph arthropod known from the middle Cambrian Burgess Shale of British Columbia. It is the most common animal represented in the Burgess Shale, with tens of thousands of specimens collected. Much rar ...

'', belong to none of these groups, as their heads are formed by their own particular combinations of segments and specialized appendages. Summarised in Gould (1990), pp. 107–121.

Working out the evolutionary stages by which all these different combinations could have appeared is so difficult that it has long been known as "the arthropod head problem

The (pan)arthropod head problem is a long-standing zoological dispute concerning the segmental composition of the heads of the various arthropod groups, and how they are evolutionarily related to each other. While the dispute has historically c ...

". In 1960, R. E. Snodgrass even hoped it would not be solved, as he found trying to work out solutions to be fun.

Exoskeleton

cuticle

A cuticle (), or cuticula, is any of a variety of tough but flexible, non-mineral outer coverings of an organism, or parts of an organism, that provide protection. Various types of "cuticle" are non- homologous, differing in their origin, structu ...

, a non-cellular material secreted by the epidermis

The epidermis is the outermost of the three layers that comprise the skin, the inner layers being the dermis and hypodermis. The epidermis layer provides a barrier to infection from environmental pathogens and regulates the amount of water relea ...

. Their cuticles vary in the details of their structure, but generally consist of three main layers: the epicuticle

The cuticle forms the major part of the integument of the Arthropoda. It includes most of the material of the exoskeleton of the insects, Crustacea, Arachnida, and Myriapoda.

Morphology

In arthropods, the integument, the external "skin", or "s ...

, a thin outer wax

Waxes are a diverse class of organic compounds that are lipophilic, malleable solids near ambient temperatures. They include higher alkanes and lipids, typically with melting points above about 40 °C (104 °F), melting to give low ...

y coat that moisture-proofs the other layers and gives them some protection; the exocuticle

The cuticle forms the major part of the integument of the Arthropoda. It includes most of the material of the exoskeleton of the insects, Crustacea, Arachnida, and Myriapoda.

Morphology

In arthropods, the integument, the external "skin", or "s ...

, which consists of chitin and chemically hardened proteins; and the endocuticle

The cuticle forms the major part of the integument of the Arthropoda. It includes most of the material of the exoskeleton of the insects, Crustacea, Arachnida, and Myriapoda.

Morphology

In arthropods, the integument, the external "skin", or "s ...

, which consists of chitin and unhardened proteins. The exocuticle and endocuticle together are known as the procuticle

The cuticle forms the major part of the integument of the Arthropoda. It includes most of the material of the exoskeleton of the insects, Crustacea, Arachnida, and Myriapoda.

Morphology

In arthropods, the integument, the external "skin", or " ...

. Each body segment and limb section is encased in hardened cuticle. The joints between body segments and between limb sections are covered by flexible cuticle.

The exoskeletons of most aquatic crustacean

Crustaceans (Crustacea, ) form a large, diverse arthropod taxon which includes such animals as decapods, seed shrimp, branchiopods, fish lice, krill, remipedes, isopods, barnacles, copepods, amphipods and mantis shrimp. The crustacean group ...

s are biomineralized with calcium carbonate extracted from the water. Some terrestrial crustaceans have developed means of storing the mineral, since on land they cannot rely on a steady supply of dissolved calcium carbonate. Biomineralization generally affects the exocuticle and the outer part of the endocuticle. Two recent hypotheses about the evolution of biomineralization in arthropods and other groups of animals propose that it provides tougher defensive armor, and that it allows animals to grow larger and stronger by providing more rigid skeletons; and in either case a mineral-organic composite

Composite or compositing may refer to:

Materials

* Composite material, a material that is made from several different substances

** Metal matrix composite, composed of metal and other parts

** Cermet, a composite of ceramic and metallic materials ...

exoskeleton is cheaper to build than an all-organic one of comparable strength.

The cuticle may have setae (bristles) growing from special cells in the epidermis. Setae are as varied in form and function as appendages. For example, they are often used as sensors to detect air or water currents, or contact with objects; aquatic arthropods use feather-like setae to increase the surface area of swimming appendages and to filter food particles out of water; aquatic insects, which are air-breathers, use thick felt

Felt is a textile material that is produced by matting, condensing and pressing fibers together. Felt can be made of natural fibers such as wool or animal fur, or from synthetic fibers such as petroleum-based acrylic or acrylonitrile or wood ...

-like coats of setae to trap air, extending the time they can spend under water; heavy, rigid setae serve as defensive spines.

Although all arthropods use muscles attached to the inside of the exoskeleton to flex their limbs, some still use hydraulic

Hydraulics (from Greek: Υδραυλική) is a technology and applied science using engineering, chemistry, and other sciences involving the mechanical properties and use of liquids. At a very basic level, hydraulics is the liquid counter ...

pressure to extend them, a system inherited from their pre-arthropod ancestors; for example, all spiders extend their legs hydraulically and can generate pressures up to eight times their resting level.

Moulting

The exoskeleton cannot stretch and thus restricts growth. Arthropods, therefore, replace their exoskeletons by undergoing ecdysis (moulting), or shedding the old exoskeleton after growing a new one that is not yet hardened. Moulting cycles run nearly continuously until an arthropod reaches full size. Ruppert, Fox & Barnes (2004), pp. 523–524

The developmental stages between each moult (ecdysis) until sexual maturity is reached is called an instar. Differences between instars can often be seen in altered body proportions, colors, patterns, changes in the number of body segments or head width. After moulting, i.e. shedding their exoskeleton, the juvenile arthropods continue in their life cycle until they either pupate or moult again.

In the initial phase of moulting, the animal stops feeding and its epidermis releases moulting fluid, a mixture of enzymes that digests the

The exoskeleton cannot stretch and thus restricts growth. Arthropods, therefore, replace their exoskeletons by undergoing ecdysis (moulting), or shedding the old exoskeleton after growing a new one that is not yet hardened. Moulting cycles run nearly continuously until an arthropod reaches full size. Ruppert, Fox & Barnes (2004), pp. 523–524

The developmental stages between each moult (ecdysis) until sexual maturity is reached is called an instar. Differences between instars can often be seen in altered body proportions, colors, patterns, changes in the number of body segments or head width. After moulting, i.e. shedding their exoskeleton, the juvenile arthropods continue in their life cycle until they either pupate or moult again.

In the initial phase of moulting, the animal stops feeding and its epidermis releases moulting fluid, a mixture of enzymes that digests the endocuticle

The cuticle forms the major part of the integument of the Arthropoda. It includes most of the material of the exoskeleton of the insects, Crustacea, Arachnida, and Myriapoda.

Morphology

In arthropods, the integument, the external "skin", or "s ...

and thus detaches the old cuticle. This phase begins when the epidermis

The epidermis is the outermost of the three layers that comprise the skin, the inner layers being the dermis and hypodermis. The epidermis layer provides a barrier to infection from environmental pathogens and regulates the amount of water relea ...

has secreted a new epicuticle

The cuticle forms the major part of the integument of the Arthropoda. It includes most of the material of the exoskeleton of the insects, Crustacea, Arachnida, and Myriapoda.

Morphology

In arthropods, the integument, the external "skin", or "s ...

to protect it from the enzymes, and the epidermis secretes the new exocuticle while the old cuticle is detaching. When this stage is complete, the animal makes its body swell by taking in a large quantity of water or air, and this makes the old cuticle split along predefined weaknesses where the old exocuticle was thinnest. It commonly takes several minutes for the animal to struggle out of the old cuticle. At this point, the new one is wrinkled and so soft that the animal cannot support itself and finds it very difficult to move, and the new endocuticle has not yet formed. The animal continues to pump itself up to stretch the new cuticle as much as possible, then hardens the new exocuticle and eliminates the excess air or water. By the end of this phase, the new endocuticle has formed. Many arthropods then eat the discarded cuticle to reclaim its materials.

Because arthropods are unprotected and nearly immobilized until the new cuticle has hardened, they are in danger both of being trapped in the old cuticle and of being attacked by predators. Moulting may be responsible for 80 to 90% of all arthropod deaths.

Internal organs

Arthropod bodies are also segmented internally, and the nervous, muscular, circulatory, and excretory systems have repeated components. Arthropods come from a lineage of animals that have acoelom

The coelom (or celom) is the main body cavity in most animals and is positioned inside the body to surround and contain the digestive tract and other organs. In some animals, it is lined with mesothelium. In other animals, such as molluscs, it r ...

, a membrane-lined cavity between the gut and the body wall that accommodates the internal organs. The strong, segmented limbs of arthropods eliminate the need for one of the coelom's main ancestral functions, as a hydrostatic skeleton

A hydrostatic skeleton, or hydroskeleton, is a flexible skeleton supported by fluid pressure. Hydrostatic skeletons are common among simple invertebrate organisms. While more advanced organisms can be considered hydrostatic, they are sometimes refe ...

, which muscles compress in order to change the animal's shape and thus enable it to move. Hence the coelom of the arthropod is reduced to small areas around the reproductive and excretory systems. Its place is largely taken by a hemocoel

The blood circulatory system is a system of organs that includes the heart, blood vessels, and blood which is circulated throughout the entire body of a human or other vertebrate. It includes the cardiovascular system, or vascular system, t ...

, a cavity that runs most of the length of the body and through which blood flows. Ruppert, Fox & Barnes (2004), pp. 527–528

Respiration and circulation

Arthropods have open circulatory systems, although most have a few short, open-endedarteries

An artery (plural arteries) () is a blood vessel in humans and most animals that takes blood away from the heart to one or more parts of the body (tissues, lungs, brain etc.). Most arteries carry oxygenated blood; the two exceptions are the p ...

. In chelicerates and crustaceans, the blood carries oxygen to the tissues, while hexapods use a separate system of tracheae

The trachea, also known as the windpipe, is a cartilaginous tube that connects the larynx to the bronchi of the lungs, allowing the passage of air, and so is present in almost all air-breathing animals with lungs. The trachea extends from the la ...

. Many crustaceans, but few chelicerates and tracheates, use respiratory pigment A respiratory pigment is a metalloprotein that serves a variety of important functions, its main being O2 transport. Other functions performed include O2 storage, CO2 transport, and transportation of substances other than respiratory gases. There ar ...

s to assist oxygen transport. The most common respiratory pigment in arthropods is copper-based hemocyanin; this is used by many crustaceans and a few centipede

Centipedes (from New Latin , "hundred", and Latin , "foot") are predatory arthropods belonging to the class Chilopoda (Ancient Greek , ''kheilos'', lip, and New Latin suffix , "foot", describing the forcipules) of the subphylum Myriapoda, an a ...

s. A few crustaceans and insects use iron-based hemoglobin, the respiratory pigment used by vertebrates. As with other invertebrates, the respiratory pigments of those arthropods that have them are generally dissolved in the blood and rarely enclosed in corpuscles as they are in vertebrates.

The heart is typically a muscular tube that runs just under the back and for most of the length of the hemocoel. It contracts in ripples that run from rear to front, pushing blood forwards. Sections not being squeezed by the heart muscle are expanded either by elastic ligaments or by small muscles, in either case connecting the heart to the body wall. Along the heart run a series of paired ostia, non-return valves that allow blood to enter the heart but prevent it from leaving before it reaches the front.

Arthropods have a wide variety of respiratory systems. Small species often do not have any, since their high ratio of surface area to volume enables simple diffusion through the body surface to supply enough oxygen. Crustacea usually have gills that are modified appendages. Many arachnids have book lung

A book lung is a type of respiration organ used for atmospheric gas exchange that is present in many arachnids, such as scorpions and spiders. Each of these organs is located inside an open ventral abdominal, air-filled cavity (atrium) and conn ...

s. Tracheae, systems of branching tunnels that run from the openings in the body walls, deliver oxygen directly to individual cells in many insects, myriapods and arachnid

Arachnida () is a class of joint-legged invertebrate animals (arthropods), in the subphylum Chelicerata. Arachnida includes, among others, spiders, scorpions, ticks, mites, pseudoscorpions, harvestmen, camel spiders, whip spiders and vinegaro ...

s.

Nervous system

Living arthropods have paired main nerve cords running along their bodies below the gut, and in each segment the cords form a pair of ganglia from which sensory and motor nerves run to other parts of the segment. Although the pairs of ganglia in each segment often appear physically fused, they are connected bycommissure

A commissure () is the location at which two objects abut or are joined. The term is used especially in the fields of anatomy and biology.

* The most common usage of the term refers to the brain's commissures, of which there are five. Such a commi ...

s (relatively large bundles of nerves), which give arthropod nervous systems a characteristic "ladder-like" appearance. The brain is in the head, encircling and mainly ''above'' the esophagus. It consists of the fused ganglia of the acron and one or two of the foremost segments that form the head – a total of three pairs of ganglia in most arthropods, but only two in chelicerates, which do not have antennae or the ganglion connected to them. The ganglia of other head segments are often close to the brain and function as part of it. In insects these other head ganglia combine into a pair of subesophageal ganglia The suboesophageal ganglion (acronym: SOG; synonym: ''subesophageal ganglion'') of arthropods and in particular insects is part of the arthropod central nervous system (CNS). As indicated by its name, it is located ''below the'' ''oesophagus'', insi ...

, under and behind the esophagus. Spiders take this process a step further, as ''all'' the segmental ganglia

The segmental ganglia (singular: s. ganglion) are ganglia of the annelid and arthropod central nervous system that lie in the segmented ventral nerve cord

The ventral nerve cord is a major structure of the invertebrate central nervous system. I ...

are incorporated into the subesophageal ganglia, which occupy most of the space in the cephalothorax (front "super-segment"). Ruppert, Fox & Barnes (2004), pp. 531–532

Excretory system

There are two different types of arthropod excretory systems. In aquatic arthropods, the end-product of biochemical reactions thatmetabolise

Metabolism (, from el, μεταβολή ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cell ...

nitrogen is ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the formula . A stable binary hydride, and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinct pungent smell. Biologically, it is a common nitrogenous wa ...

, which is so toxic that it needs to be diluted as much as possible with water. The ammonia is then eliminated via any permeable membrane, mainly through the gills. All crustaceans use this system, and its high consumption of water may be responsible for the relative lack of success of crustaceans as land animals. Ruppert, Fox & Barnes (2004), pp. 529–530 Various groups of terrestrial arthropods have independently developed a different system: the end-product of nitrogen metabolism is uric acid

Uric acid is a heterocyclic compound of carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and hydrogen with the formula C5H4N4O3. It forms ions and salts known as urates and acid urates, such as ammonium acid urate. Uric acid is a product of the metabolic breakdown o ...

, which can be excreted as dry material; the Malpighian tubule system

The Malpighian tubule system is a type of excretory and osmoregulatory system found in some insects, myriapods, arachnids and tardigrades.

The system consists of branching tubules extending from the alimentary canal that absorbs solutes, wate ...

filters the uric acid and other nitrogenous waste out of the blood in the hemocoel, and dumps these materials into the hindgut, from which they are expelled as feces. Most aquatic arthropods and some terrestrial ones also have organs called nephridia

The nephridium (plural ''nephridia'') is an invertebrate organ, found in pairs and performing a function similar to the vertebrate kidneys (which originated from the chordate nephridia). Nephridia remove metabolic wastes from an animal's body. Neph ...

("little kidneys"), which extract other wastes for excretion as urine

Urine is a liquid by-product of metabolism in humans and in many other animals. Urine flows from the kidneys through the ureters to the urinary bladder. Urination results in urine being excreted from the body through the urethra.

Cellular m ...

.

Senses

The stiffcuticle

A cuticle (), or cuticula, is any of a variety of tough but flexible, non-mineral outer coverings of an organism, or parts of an organism, that provide protection. Various types of "cuticle" are non- homologous, differing in their origin, structu ...

s of arthropods would block out information about the outside world, except that they are penetrated by many sensors or connections from sensors to the nervous system. In fact, arthropods have modified their cuticles into elaborate arrays of sensors. Various touch sensors, mostly setae, respond to different levels of force, from strong contact to very weak air currents. Chemical sensors provide equivalents of taste and smell

Smell may refer to;

* Odor, airborne molecules perceived as a scent or aroma

* Sense of smell, the scent also known scientifically as olfaction

* "Smells" (''Bottom''), an episode of ''Bottom''

* The Smell, a music venue in Los Angeles, Californ ...

, often by means of setae. Pressure sensors often take the form of membranes that function as eardrums, but are connected directly to nerves rather than to auditory ossicle

The ossicles (also called auditory ossicles) are three bones in either middle ear that are among the smallest bones in the human body. They serve to transmit sounds from the air to the fluid-filled labyrinth (cochlea). The absence of the auditor ...

s. The antennae of most hexapods include sensor packages that monitor humidity, moisture and temperature. Ruppert, Fox & Barnes (2004), pp. 532–537

Most arthropods lack balance and acceleration

In mechanics, acceleration is the rate of change of the velocity of an object with respect to time. Accelerations are vector quantities (in that they have magnitude and direction). The orientation of an object's acceleration is given by the ...

sensors, and rely on their eyes to tell them which way is up. The self-righting behavior of cockroach

Cockroaches (or roaches) are a paraphyletic group of insects belonging to Blattodea, containing all members of the group except termites. About 30 cockroach species out of 4,600 are associated with human habitats. Some species are well-known as ...

es is triggered when pressure sensors on the underside of the feet report no pressure. However, many malacostracan

Malacostraca (from New Latin; ) is the largest of the six classes of crustaceans, containing about 40,000 living species, divided among 16 orders. Its members, the malacostracans, display a great diversity of body forms and include crabs, lobs ...

crustaceans have statocyst

The statocyst is a balance sensory receptor present in some aquatic invertebrates, including bivalves, cnidarians, ctenophorans, echinoderms, cephalopods, and crustaceans. A similar structure is also found in ''Xenoturbella''. The statocyst cons ...

s, which provide the same sort of information as the balance and motion sensors of the vertebrate inner ear

The inner ear (internal ear, auris interna) is the innermost part of the vertebrate ear. In vertebrates, the inner ear is mainly responsible for sound detection and balance. In mammals, it consists of the bony labyrinth, a hollow cavity in the ...

.

The proprioceptor

Proprioception ( ), also referred to as kinaesthesia (or kinesthesia), is the sense of self-movement, force, and body position. It is sometimes described as the "sixth sense".

Proprioception is mediated by proprioceptors, mechanosensory neurons ...

s of arthropods, sensors that report the force exerted by muscles and the degree of bending in the body and joints, are well understood. However, little is known about what other internal sensors arthropods may have.

Optical

Most arthropods have sophisticated visual systems that include one or more usually both of

Most arthropods have sophisticated visual systems that include one or more usually both of compound eye

A compound eye is a visual organ found in arthropods such as insects and crustaceans. It may consist of thousands of ommatidia, which are tiny independent photoreception units that consist of a cornea, lens, and photoreceptor cells which disti ...

s and pigment-cup ocelli ("little eyes"). In most cases ocelli are only capable of detecting the direction from which light is coming, using the shadow cast by the walls of the cup. However, the main eyes of spiders are pigment-cup ocelli that are capable of forming images, and those of jumping spiders can rotate to track prey.

Compound eyes consist of fifteen to several thousand independent ommatidia

The compound eyes of arthropods like insects, crustaceans and millipedes are composed of units called ommatidia (singular: ommatidium). An ommatidium contains a cluster of photoreceptor cells surrounded by support cells and pigment cells. The ...

, columns that are usually hexagon

In geometry, a hexagon (from Greek , , meaning "six", and , , meaning "corner, angle") is a six-sided polygon. The total of the internal angles of any simple (non-self-intersecting) hexagon is 720°.

Regular hexagon

A '' regular hexagon'' has ...

al in cross section

Cross section may refer to:

* Cross section (geometry)

** Cross-sectional views in architecture & engineering 3D

*Cross section (geology)

* Cross section (electronics)

* Radar cross section, measure of detectability

* Cross section (physics)

**Abs ...

. Each ommatidium is an independent sensor, with its own light-sensitive cells and often with its own lens

A lens is a transmissive optical device which focuses or disperses a light beam by means of refraction. A simple lens consists of a single piece of transparent material, while a compound lens consists of several simple lenses (''elements''), ...

and cornea

The cornea is the transparent front part of the eye that covers the iris, pupil, and anterior chamber. Along with the anterior chamber and lens, the cornea refracts light, accounting for approximately two-thirds of the eye's total optical powe ...

. Compound eyes have a wide field of view, and can detect fast movement and, in some cases, the polarization of light. On the other hand, the relatively large size of ommatidia makes the images rather coarse, and compound eyes are shorter-sighted than those of birds and mammals – although this is not a severe disadvantage, as objects and events within are most important to most arthropods. Several arthropods have color vision, and that of some insects has been studied in detail; for example, the ommatidia of bees contain receptors for both green and ultra-violet.

Olfaction

Reproduction and development

barnacle

A barnacle is a type of arthropod constituting the subclass Cirripedia in the subphylum Crustacea, and is hence related to crabs and lobsters. Barnacles are exclusively marine, and tend to live in shallow and tidal waters, typically in erosive ...

s, are hermaphroditic

In reproductive biology, a hermaphrodite () is an organism that has both kinds of reproductive organs and can produce both gametes associated with male and female sexes.

Many taxonomic groups of animals (mostly invertebrates) do not have sepa ...

, that is, each can have the organs of both sex

Sex is the trait that determines whether a sexually reproducing animal or plant produces male or female gametes. Male plants and animals produce smaller mobile gametes (spermatozoa, sperm, pollen), while females produce larger ones (ova, ...

es. However, individuals of most species remain of one sex their entire lives. A few species of insects and crustaceans can reproduce by parthenogenesis, especially if conditions favor a "population explosion". However, most arthropods rely on sexual reproduction, and parthenogenetic species often revert to sexual reproduction when conditions become less favorable. The ability to undergo meiosis is widespread among arthropods including both those that reproduce sexually and those that reproduce parthenogenetically

Parthenogenesis (; from the Greek grc, παρθένος, translit=parthénos, lit=virgin, label=none + grc, γένεσις, translit=génesis, lit=creation, label=none) is a natural form of asexual reproduction in which growth and development ...

. Although meiosis is a major characteristic of arthropods, understanding of its fundamental adaptive benefit has long been regarded as an unresolved problem, that appears to have remained unsettled.

Aquatic arthropods may breed by external fertilization, as for example horseshoe crabs do, or by internal fertilization, where the ova

, abbreviated as OVA and sometimes as OAV (original animation video), are Japanese animated films and series made specially for release in home video formats without prior showings on television or in theaters, though the first part of an OVA s ...

remain in the female's body and the sperm

Sperm is the male reproductive cell, or gamete, in anisogamous forms of sexual reproduction (forms in which there is a larger, female reproductive cell and a smaller, male one). Animals produce motile sperm with a tail known as a flagellum, wh ...

must somehow be inserted. All known terrestrial arthropods use internal fertilization. Opiliones

The Opiliones (formerly Phalangida) are an order of arachnids colloquially known as harvestmen, harvesters, harvest spiders, or daddy longlegs. , over 6,650 species of harvestmen have been discovered worldwide, although the total number of ext ...

(harvestmen), millipedes, and some crustaceans use modified appendages such as gonopod

Gonopods are specialized appendages of various arthropods used in reproduction or egg-laying. In males, they facilitate the transfer of sperm from male to female during mating, and thus are a type of intromittent organ. In crustaceans and milliped ...

s or penises

A penis (plural ''penises'' or ''penes'' () is the primary sexual organ that male animals use to inseminate females (or hermaphrodites) during copulation. Such organs occur in many animals, both vertebrate and invertebrate, but males do no ...

to transfer the sperm directly to the female. However, most male terrestrial arthropods produce spermatophore

A spermatophore or sperm ampulla is a capsule or mass containing spermatozoa created by males of various animal species, especially salamanders and arthropods, and transferred in entirety to the female's ovipore during reproduction. Spermatophore ...

s, waterproof packets of sperm

Sperm is the male reproductive cell, or gamete, in anisogamous forms of sexual reproduction (forms in which there is a larger, female reproductive cell and a smaller, male one). Animals produce motile sperm with a tail known as a flagellum, wh ...

, which the females take into their bodies. A few such species rely on females to find spermatophores that have already been deposited on the ground, but in most cases males only deposit spermatophores when complex courtship

Courtship is the period wherein some couples get to know each other prior to a possible marriage. Courtship traditionally may begin after a betrothal and may conclude with the celebration of marriage. A courtship may be an informal and private m ...

rituals look likely to be successful. Ruppert, Fox & Barnes (2004), pp. 537–539

Most arthropods lay eggs, but scorpions are ovoviparous: they produce live young after the eggs have hatched inside the mother, and are noted for prolonged maternal care. Newly born arthropods have diverse forms, and insects alone cover the range of extremes. Some hatch as apparently miniature adults (direct development), and in some cases, such as silverfish, the hatchlings do not feed and may be helpless until after their first moult. Many insects hatch as grubs or

Most arthropods lay eggs, but scorpions are ovoviparous: they produce live young after the eggs have hatched inside the mother, and are noted for prolonged maternal care. Newly born arthropods have diverse forms, and insects alone cover the range of extremes. Some hatch as apparently miniature adults (direct development), and in some cases, such as silverfish, the hatchlings do not feed and may be helpless until after their first moult. Many insects hatch as grubs or caterpillar

Caterpillars ( ) are the larval stage of members of the order Lepidoptera (the insect order comprising butterflies and moths).

As with most common names, the application of the word is arbitrary, since the larvae of sawflies (suborder Symph ...

s, which do not have segmented limbs or hardened cuticles, and metamorphose

Metamorphosis is a biological process by which an animal physically develops including birth or hatching, involving a conspicuous and relatively abrupt change in the animal's body structure through cell growth and differentiation. Some inse ...

into adult forms by entering an inactive phase in which the larval tissues are broken down and re-used to build the adult body. Dragonfly

A dragonfly is a flying insect belonging to the infraorder Anisoptera below the order Odonata. About 3,000 extant species of true dragonfly are known. Most are tropical, with fewer species in temperate regions. Loss of wetland habitat threat ...

larvae have the typical cuticles and jointed limbs of arthropods but are flightless water-breathers with extendable jaws. Crustaceans commonly hatch as tiny nauplius larvae that have only three segments and pairs of appendages.

Evolutionary history

Last common ancestor

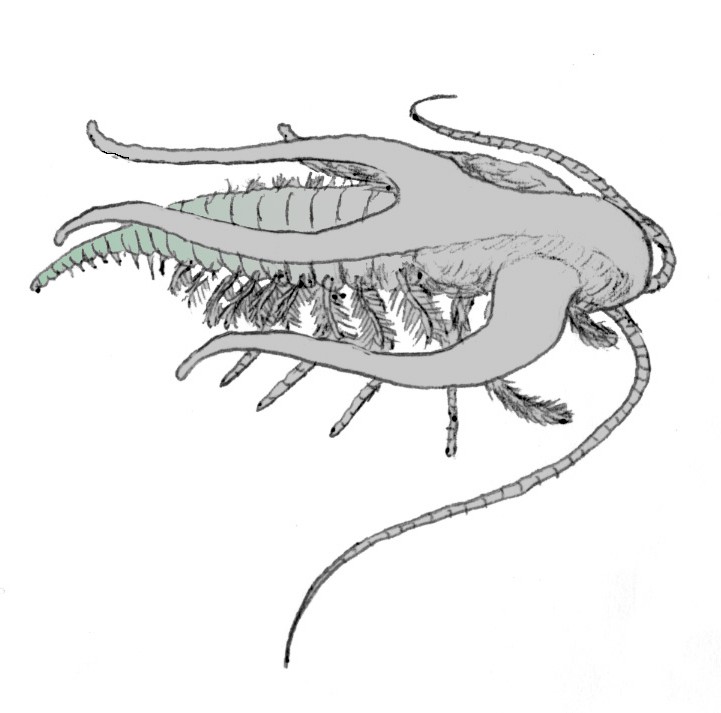

Based on the distribution of sharedplesiomorphic

In phylogenetics, a plesiomorphy ("near form") and symplesiomorphy are synonyms for an ancestral character shared by all members of a clade, which does not distinguish the clade from other clades.

Plesiomorphy, symplesiomorphy, apomorphy, and ...

features in extant and fossil taxa, the last common ancestor

In biology and genetic genealogy, the most recent common ancestor (MRCA), also known as the last common ancestor (LCA) or concestor, of a set of organisms is the most recent individual from which all the organisms of the set are descended. The ...

of all arthropods is inferred to have been as a modular organism with each module covered by its own sclerite (armor plate) and bearing a pair of biramous limbs. However, whether the ancestral limb was uniramous or biramous is far from a settled debate.

This Ur-arthropod had a ventral

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to unambiguously describe the anatomy of animals, including humans. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. This position prov ...

mouth, pre-oral antennae and dorsal

Dorsal (from Latin ''dorsum'' ‘back’) may refer to:

* Dorsal (anatomy), an anatomical term of location referring to the back or upper side of an organism or parts of an organism

* Dorsal, positioned on top of an aircraft's fuselage

* Dorsal co ...

eyes at the front of the body. It was assumed to have been a non-discriminatory sediment feeder, processing whatever sediment came its way for food, but fossil findings hint that the last common ancestor of both arthropods and priapulida shared the same specialized mouth apparatus; a circular mouth with rings of teeth used for capturing animal prey.

Fossil record

It has been proposed that the Ediacaran animals ''

It has been proposed that the Ediacaran animals ''Parvancorina

''Parvancorina'' is a genus of shield-shaped bilaterally symmetrical fossil animal that lived in the late Ediacaran seafloor. It has some superficial similarities with the Cambrian trilobite-like arthropods.

Etymology

The generic name is derived ...

'' and '' Spriggina'', from around , were arthropods, but later study shows that their affinities of being origin of arthropods are not reliable. Small arthropods with bivalve-like shells have been found in Early Cambrian fossil beds dating in China and Australia. The earliest Cambrian trilobite fossils are about 530 million years old, but the class was already quite diverse and worldwide, suggesting that they had been around for quite some time. In the Maotianshan shales

The Maotianshan Shales are a series of Early Cambrian deposits in the Chiungchussu Formation, famous for their '' Konservat Lagerstätten'', deposits known for the exceptional preservation of fossilized organisms or traces. The Maotianshan Shales ...

, which date to between 530 and 520 million years ago, fossils of arthropods such as ''Kylinxia

''Kylinxia'' is a genus of extinct arthropod described in 2020. It was described from six specimens discovered in Yu'anshan Formation (Maotianshan Shales) in southern China. The specimens are assigned to one species ''Kylinxia zhangi.'' Dated to ...

'' and ''Erratus

''Erratus'' is an extinct genus of marine arthropod from the Cambrian of China. Its type and only species is ''Erratus sperare''. ''Erratus'' is likely one of the most basal known arthropods, and its discovery has helped scientists understand th ...

'' have been found that seem to show a transitional split between lobopodia and other more primitive stem arthropods. Re-examination in the 1970s of the Burgess Shale

The Burgess Shale is a fossil-bearing deposit exposed in the Canadian Rockies of British Columbia, Canada. It is famous for the exceptional preservation of the soft parts of its fossils. At old (middle Cambrian), it is one of the earliest fos ...

fossils from about identified many arthropods, some of which could not be assigned to any of the well-known groups, and thus intensified the debate about the Cambrian explosion

The Cambrian explosion, Cambrian radiation, Cambrian diversification, or the Biological Big Bang refers to an interval of time approximately in the Cambrian Period when practically all major animal phyla started appearing in the fossil recor ...

.Whittington, H. B. (1979). Early arthropods, their appendages and relationships. In M. R. House (Ed.), The origin of major invertebrate groups (pp. 253–268). The Systematics Association Special Volume, 12. London: Academic Press. Gould (1990) A fossil of ''Marrella

''Marrella'' is an extinct genus of marrellomorph arthropod known from the middle Cambrian Burgess Shale of British Columbia. It is the most common animal represented in the Burgess Shale, with tens of thousands of specimens collected. Much rar ...

'' from the Burgess Shale has provided the earliest clear evidence of moulting.

The earliest fossil crustaceans date from about in the

The earliest fossil crustaceans date from about in the Cambrian

The Cambrian Period ( ; sometimes symbolized Ꞓ) was the first geological period of the Paleozoic Era, and of the Phanerozoic Eon. The Cambrian lasted 53.4 million years from the end of the preceding Ediacaran Period 538.8 million years ago ( ...

, and fossil shrimp from about apparently formed a tight-knit procession across the seabed. Crustacean fossils are common from the Ordovician

The Ordovician ( ) is a geologic period and system, the second of six periods of the Paleozoic Era. The Ordovician spans 41.6 million years from the end of the Cambrian Period million years ago (Mya) to the start of the Silurian Period Mya.

The ...

period onwards. They have remained almost entirely aquatic, possibly because they never developed excretory systems that conserve water. In 2020 scientists announced the discovery of ''Kylinxia

''Kylinxia'' is a genus of extinct arthropod described in 2020. It was described from six specimens discovered in Yu'anshan Formation (Maotianshan Shales) in southern China. The specimens are assigned to one species ''Kylinxia zhangi.'' Dated to ...

'', a five-eyed ~5 cm long shrimp-like animal living 518 Mya that – with multiple distinctive features – appears to be a key ‘ missing link’ of the evolution from ''Anomalocaris

''Anomalocaris'' ("unlike other shrimp", or "abnormal shrimp") is an extinct genus of radiodont, an order of early-diverging stem-group arthropods. The first fossils of ''Anomalocaris'' were discovered in the ''Ogygopsis'' Shale of the Stephen F ...

'' to true arthropods and could be at the evolutionary root of true arthropods.

Arthropods provide the earliest identifiable fossils of land animals, from about in the Late Silurian, and terrestrial tracks from about appear to have been made by arthropods. Arthropods possessed attributes that were easy coopted for life on land; their existing jointed exoskeletons provided protection against desiccation, support against gravity and a means of locomotion that was not dependent on water. Around the same time the aquatic, scorpion-like eurypterids became the largest ever arthropods, some as long as .

The oldest known arachnid

Arachnida () is a class of joint-legged invertebrate animals (arthropods), in the subphylum Chelicerata. Arachnida includes, among others, spiders, scorpions, ticks, mites, pseudoscorpions, harvestmen, camel spiders, whip spiders and vinegaro ...

is the trigonotarbid '' Palaeotarbus jerami'', from about in the Silurian period. ''Attercopus

''Attercopus'' is an extinct genus of arachnids, containing one species ''Attercopus fimbriunguis'', known from flattened cuticle fossils from the Panther Mountain Formation in Upstate New York. It is placed in the extinct order Uraraneida, sp ...

fimbriunguis'', from in the Devonian period, bears the earliest known silk-producing spigots, but its lack of spinnerets means it was not one of the true spiders, which first appear in the Late Carboniferous

The Carboniferous ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic that spans 60 million years from the end of the Devonian Period million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Permian Period, million years ago. The name ''Carboniferous ...

over . The Jurassic and Cretaceous periods provide a large number of fossil spiders, including representatives of many modern families. Fossils of aquatic scorpions with gills appear in the Silurian and Devonian periods, and the earliest fossil of an air-breathing scorpion with book lung

A book lung is a type of respiration organ used for atmospheric gas exchange that is present in many arachnids, such as scorpions and spiders. Each of these organs is located inside an open ventral abdominal, air-filled cavity (atrium) and conn ...

s dates from the Early Carboniferous period.

The oldest possible insect fossil is the Devonian ''Rhyniognatha hirsti

''Rhyniognatha'' is an extinct genus of arthropod of disputed placement. It has been considered in some analyses as the oldest insect known, as well as possibly being a flying insect. ''Rhyniognatha'' is known from a partial head with preserved m ...

'', dated at , but its mandible

In anatomy, the mandible, lower jaw or jawbone is the largest, strongest and lowest bone in the human facial skeleton. It forms the lower jaw and holds the lower tooth, teeth in place. The mandible sits beneath the maxilla. It is the only movabl ...

s are of a type found only in winged insects, which suggests that the earliest insects appeared in the Silurian period, although later study shows possibility that ''Rhyniognatha'' can be myriapod, not an insect. The Mazon Creek lagerstätten from the Late Carboniferous, about , include about 200 species, some gigantic by modern standards, and indicate that insects had occupied their main modern ecological niches as herbivore

A herbivore is an animal anatomically and physiologically adapted to eating plant material, for example foliage or marine algae, for the main component of its diet. As a result of their plant diet, herbivorous animals typically have mouthp ...

s, detritivores and insectivores. Social termite

Termites are small insects that live in colonies and have distinct castes (eusocial) and feed on wood or other dead plant matter. Termites comprise the infraorder Isoptera, or alternatively the epifamily Termitoidae, within the order Blattode ...

s and ant

Ants are eusocial insects of the family Formicidae and, along with the related wasps and bees, belong to the order Hymenoptera. Ants evolved from vespoid wasp ancestors in the Cretaceous period. More than 13,800 of an estimated total of 22,0 ...

s first appear in the Early Cretaceous, and advanced social bees have been found in Late Cretaceous rocks but did not become abundant until the Middle Cenozoic

The Cenozoic ( ; ) is Earth's current geological era, representing the last 66million years of Earth's history. It is characterised by the dominance of mammals, birds and flowering plants, a cooling and drying climate, and the current configurat ...

.

Evolutionary family tree

From 1952 to 1977, zoologist

From 1952 to 1977, zoologist Sidnie Manton

Sidnie Milana Manton (4 May 1902 – 2 January 1979) was an influential British zoologist. She is known for making advances in the field of functional morphology. She is regarded as being one of the most outstanding zoologists of the twentieth ...

and others argued that arthropods are polyphyletic, in other words, that they do not share a common ancestor that was itself an arthropod. Instead, they proposed that three separate groups of "arthropods" evolved separately from common worm-like ancestors: the chelicerate

The subphylum Chelicerata (from New Latin, , ) constitutes one of the major subdivisions of the phylum Arthropoda. It contains the sea spiders, horseshoe crabs, and arachnids (including harvestmen, scorpions, spiders, solifuges, ticks, and mite ...

s, including spiders and scorpions; the crustaceans; and the uniramia

Uniramia (''uni'' – one, ''ramus'' – branch, i.e. single-branches) is a group within the arthropods. In the past this group included the Onychophora, which are now considered a separate category. The group is currently used in a narrower sens ...

, consisting of onychophoran

Onychophora (from grc, ονυχής, , "claws"; and , , "to carry"), commonly known as velvet worms (due to their velvety texture and somewhat wormlike appearance) or more ambiguously as peripatus (after the first described genus, '' Peripatus ...

s, myriapods and hexapods. These arguments usually bypassed trilobites, as the evolutionary relationships of this class were unclear. Proponents of polyphyly argued the following: that the similarities between these groups are the results of convergent evolution, as natural consequences of having rigid, segmented exoskeletons; that the three groups use different chemical means of hardening the cuticle; that there were significant differences in the construction of their compound eyes; that it is hard to see how such different configurations of segments and appendages in the head could have evolved from the same ancestor; and that crustaceans have biramous The arthropod leg is a form of jointed appendage of arthropods, usually used for walking. Many of the terms used for arthropod leg segments (called podomeres) are of Latin origin, and may be confused with terms for bones: ''coxa'' (meaning hip, plu ...

limbs with separate gill and leg branches, while the other two groups have uniramous The arthropod leg is a form of jointed appendage of arthropods, usually used for walking. Many of the terms used for arthropod leg segments (called podomeres) are of Latin origin, and may be confused with terms for bones: ''coxa'' (meaning hip, plu ...

limbs in which the single branch serves as a leg.

Further analysis and discoveries in the 1990s reversed this view, and led to acceptance that arthropods are monophyletic, in other words they are inferred to share a common ancestor that was itself an arthropod. For example, Graham Budd's analyses of ''Kerygmachela

''Kerygmachela kierkegaardi'' is a gilled lobopodian from the Cambrian Stage 3 aged Sirius Passet Lagerstätte in northern Greenland. Its anatomy strongly suggests that it, along with its relative ''Pambdelurion whittingtoni'', was a close rela ...

'' in 1993 and of '' Opabinia'' in 1996 convinced him that these animals were similar to onychophorans and to various Early Cambrian

The Cambrian Period ( ; sometimes symbolized Ꞓ) was the first geological period of the Paleozoic Era, and of the Phanerozoic Eon. The Cambrian lasted 53.4 million years from the end of the preceding Ediacaran Period 538.8 million years ago ( ...

"lobopod

The lobopodians, members of the informal group Lobopodia (from the Greek, meaning "blunt feet"), or the formally erected phylum Lobopoda Cavalier-Smith (1998), are panarthropods with stubby legs called lobopods, a term which may also be used as ...

s", and he presented an "evolutionary family tree" that showed these as "aunts" and "cousins" of all arthropods. These changes made the scope of the term "arthropod" unclear, and Claus Nielsen proposed that the wider group should be labelled " Panarthropoda" ("all the arthropods") while the animals with jointed limbs and hardened cuticles should be called "Euarthropoda" ("true arthropods").

A contrary view was presented in 2003, when Jan Bergström and Xian-Guang Hou argued that, if arthropods were a "sister-group" to any of the anomalocarids, they must have lost and then re-evolved features that were well-developed in the anomalocarids. The earliest known arthropods ate mud in order to extract food particles from it, and possessed variable numbers of segments with unspecialized appendages that functioned as both gills and legs. Anomalocarids were, by the standards of the time, huge and sophisticated predators with specialized mouths and grasping appendages, fixed numbers of segments some of which were specialized, tail fins, and gills that were very different from those of arthropods. In 2006, they suggested that arthropods were more closely related to lobopod

The lobopodians, members of the informal group Lobopodia (from the Greek, meaning "blunt feet"), or the formally erected phylum Lobopoda Cavalier-Smith (1998), are panarthropods with stubby legs called lobopods, a term which may also be used as ...

s and tardigrades than to anomalocarids. In 2014, research indicated that tardigrades were more closely related to arthropods than velvet worms.

Higher up the "family tree", the Annelida have traditionally been considered the closest relatives of the Panarthropoda, since both groups have segmented bodies, and the combination of these groups was labelled Articulata. There had been competing proposals that arthropods were closely related to other groups such as nematode

The nematodes ( or grc-gre, Νηματώδη; la, Nematoda) or roundworms constitute the phylum Nematoda (also called Nemathelminthes), with plant- parasitic nematodes also known as eelworms. They are a diverse animal phylum inhabiting a bro ...

s, priapulid

Priapulida (priapulid worms, from Gr. πριάπος, ''priāpos'' 'Priapus' + Lat. ''-ul-'', diminutive), sometimes referred to as penis worms, is a phylum of unsegmented marine worms. The name of the phylum relates to the Greek god of fertility ...

s and tardigrades, but these remained minority views because it was difficult to specify in detail the relationships between these groups.

In the 1990s, molecular phylogenetic

Molecular phylogenetics () is the branch of phylogeny that analyzes genetic, hereditary molecular differences, predominantly in DNA sequences, to gain information on an organism's evolutionary relationships. From these analyses, it is possible to ...

analyses of DNA sequences produced a coherent scheme showing arthropods as members of a superphylum labelled Ecdysozoa ("animals that moult"), which contained nematodes, priapulids and tardigrades but excluded annelids. This was backed up by studies of the anatomy and development of these animals, which showed that many of the features that supported the Articulata hypothesis showed significant differences between annelids and the earliest Panarthropods in their details, and some were hardly present at all in arthropods. This hypothesis groups annelids with molluscs and brachiopod

Brachiopods (), phylum Brachiopoda, are a phylum of trochozoan animals that have hard "valves" (shells) on the upper and lower surfaces, unlike the left and right arrangement in bivalve molluscs. Brachiopod valves are hinged at the rear end, wh ...

s in another superphylum, Lophotrochozoa

Lophotrochozoa (, "crest/wheel animals") is a clade of protostome animals within the Spiralia. The taxon was established as a monophyletic group based on molecular evidence. The clade includes animals like annelids, molluscs, bryozoans, brachiop ...

.

If the Ecdysozoa hypothesis is correct, then segmentation of arthropods and annelids either has evolved convergently or has been inherited from a much older ancestor and subsequently lost in several other lineages, such as the non-arthropod members of the Ecdysozoa.

Phylogeny of stem-group arthropods

Modern interpretations of the basal, extinctstem-group

In phylogenetics, the crown group or crown assemblage is a collection of species composed of the living representatives of the collection, the most recent common ancestor of the collection, and all descendants of the most recent common ancestor. ...

of Arthropoda recognised the following groups, from most basal to most crownward:

* The "Giant" or "Siberiid Lobopodians", such as ''Jianshanopodia