Armistice of Belgrade on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The armistice of Belgrade was an agreement on the termination of

On 29 September 1918, in the final stages of

On 29 September 1918, in the final stages of

Austria-Hungary signed the

Austria-Hungary signed the

On 6 November, Károlyi led a delegation consisting of the Minister for Nationalities,

On 6 November, Károlyi led a delegation consisting of the Minister for Nationalities,

Károlyi reported on the negotiations at a cabinet meeting on 8 November, noting the amount of horses and rolling stock demanded by the Allies for transportation. He also reported that the administration of the country (including south of the demarcation line) would be left to Hungary. The cabinet decided to wait for Clemenceau to reply before acting any further. That day, the Serbian ''Drina'' Division was tasked with occupying Syrmia and a part of Slavonia east of the Brod–

Károlyi reported on the negotiations at a cabinet meeting on 8 November, noting the amount of horses and rolling stock demanded by the Allies for transportation. He also reported that the administration of the country (including south of the demarcation line) would be left to Hungary. The cabinet decided to wait for Clemenceau to reply before acting any further. That day, the Serbian ''Drina'' Division was tasked with occupying Syrmia and a part of Slavonia east of the Brod–

The signed agreement consisted of 18 points. The first specified the demarcation line running along the upper course of the

The signed agreement consisted of 18 points. The first specified the demarcation line running along the upper course of the

Charles I abdicated on 13 November, and days later, the

Charles I abdicated on 13 November, and days later, the

In order to address increasingly frequent skirmishes along the Hungarian–Romanian line of control, the Paris Peace Conference decided on 26 February 1919 to allow Romanian troops in an area beyond the demarcation line established by the armistice of Belgrade, and set up an additional neutral zone to be occupied by Allied forces other than Romanians. This established the "temporary frontier" along the Arad–Carei–Satu Mare line. Vix was tasked with presenting the demand to the Hungarian authorities, along with the request that their withdrawal must start on 23 March and be completed within ten days. On 20 March 1919, Hungary was presented with the demand that became known as the

In order to address increasingly frequent skirmishes along the Hungarian–Romanian line of control, the Paris Peace Conference decided on 26 February 1919 to allow Romanian troops in an area beyond the demarcation line established by the armistice of Belgrade, and set up an additional neutral zone to be occupied by Allied forces other than Romanians. This established the "temporary frontier" along the Arad–Carei–Satu Mare line. Vix was tasked with presenting the demand to the Hungarian authorities, along with the request that their withdrawal must start on 23 March and be completed within ten days. On 20 March 1919, Hungary was presented with the demand that became known as the

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

hostilities between the Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French '' entente'' meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland as well a ...

and the Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the Coronation of the Hungarian monarch, c ...

concluded in Belgrade

Belgrade ( , ;, ; names in other languages) is the capital and largest city in Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers and the crossroads of the Pannonian Plain and the Balkan Peninsula. Nearly 1,166,763 mi ...

on 13 November 1918. It was largely negotiated by General

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". O ...

Louis Franchet d'Espèrey

Louis Félix Marie François Franchet d'Espèrey (25 May 1856 – 8 July 1942) was a French general during World War I. As commander of the large Allied army based at Salonika, he conducted the successful Macedonian campaign, which caused t ...

, as the commanding officer of the Allied Army of the Orient, and Hungarian Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

Mihály Károlyi, on 7 November. It was signed by General Paul Prosper Henrys

Paul Prosper Henrys (or Paul-Prosper) (13 March 1862 – 6 November 1943) was a French general.

In his early career, Henrys was stationed in French Algeria. In 1912, he participated in the French conquest of Morocco under general Hubert Lyautey. ...

and '' vojvoda'' Živojin Mišić

Field Marshal Živojin Mišić ( sr-cyrl, Живојин Мишић; 19 July 1855 in Struganik – 20 January 1921 in Belgrade) was a Field Marshal who participated in all of Serbia's wars from 1876 to 1918. He directly commanded the First Se ...

, as representatives of the Allies, and by the Hungarian Minister of War, Béla Linder

Béla Linder ( Majs, 10 February 1876 – Belgrade, 15 April 1962), Hungarian colonel of artillery, Secretary of War of Mihály Károlyi government, minister without portfolio of Dénes Berinkey government, military attaché of Hungarian Sovie ...

.

The agreement defined a demarcation line

{{Refimprove, date=January 2008

A political demarcation line is a geopolitical border, often agreed upon as part of an armistice or ceasefire.

Africa

* Moroccan Wall, delimiting the Moroccan-controlled part of Western Sahara from the Sahrawi ...

marking the southern limit of deployment of most Hungarian armed forces. It left large parts of the Lands of the Crown of Saint Stephen

The Lands of the Crown of Saint Stephen ( hu, a Szent Korona Országai), informally Transleithania (meaning the lands or region "beyond" the Leitha River) were the Hungarian territories of Austria-Hungary, throughout the latter's entire exis ...

(the Hungarian part of Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

) outside Hungarian control – including parts or entire regions of Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the A ...

, Banat

Banat (, ; hu, Bánság; sr, Банат, Banat) is a geographical and historical region that straddles Central and Eastern Europe and which is currently divided among three countries: the eastern part lies in western Romania (the counties of ...

, Bačka

Bačka ( sr-cyrl, Бачка, ) or Bácska () is a geographical and historical area within the Pannonian Plain bordered by the river Danube to the west and south, and by the river Tisza to the east. It is divided between Serbia and Hunga ...

, Baranya, as well as Croatia-Slavonia

The Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia ( hr, Kraljevina Hrvatska i Slavonija; hu, Horvát-Szlavónország or ; de-AT, Königreich Kroatien und Slawonien) was a nominally autonomous kingdom and constitutionally defined separate political nation with ...

. It also spelled out in eighteen points the obligations imposed on Hungary by the Allies. Those obligations included Hungary's armed forces being reduced to eight divisions, the clearing of naval mine

A naval mine is a self-contained explosive device placed in water to damage or destroy surface ships or submarines. Unlike depth charges, mines are deposited and left to wait until they are triggered by the approach of, or contact with, an ...

s, as well as the turning over of certain quantities of rolling stock

The term rolling stock in the rail transport industry refers to railway vehicles, including both powered and unpowered vehicles: for example, locomotives, freight and passenger cars (or coaches), and non-revenue cars. Passenger vehicles ca ...

, river ships, tugboat

A tugboat or tug is a marine vessel that manoeuvres other vessels by pushing or pulling them, with direct contact or a tow line. These boats typically tug ships in circumstances where they cannot or should not move under their own power, su ...

s, barge

Barge nowadays generally refers to a flat-bottomed inland waterway vessel which does not have its own means of mechanical propulsion. The first modern barges were pulled by tugs, but nowadays most are pushed by pusher boats, or other vessels. ...

s, river monitor

River monitors are military craft designed to patrol rivers.

They are normally the largest of all riverine warships in river flotillas, and mount the heaviest weapons. The name originated from the US Navy's , which made her first appearance in ...

s, horses and other materiel

Materiel (; ) refers to supplies, equipment, and weapons in military supply-chain management, and typically supplies and equipment in a commercial supply chain context.

In a military context, the term ''materiel'' refers either to the spec ...

to the Allies. Hungary was also obliged to make certain personnel available to repair wartime damage inflicted on Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia ( Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin and the Balkans. It shares land borders with Hu ...

's telegraph infrastructure, as well as to provide personnel to staff railways.

The terms of the armistice and the subsequent actions of the Allies embittered a significant part of Hungary's population and caused the downfall of Károlyi and the First Hungarian Republic

The First Hungarian Republic ( hu, Első Magyar Köztársaság), until 21 March 1919 the Hungarian People's Republic (), was a short-lived unrecognized country, which quickly transformed into a small rump state due to the foreign and military ...

, which had been established only days after its signing. In 1919, the First Hungarian Republic was replaced by the short-lived, communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

-ruled Hungarian Soviet Republic

The Socialist Federative Republic of Councils in Hungary ( hu, Magyarországi Szocialista Szövetséges Tanácsköztársaság) (due to an early mistranslation, it became widely known as the Hungarian Soviet Republic in English-language sources ( ...

. Much of the Allied-occupied territories determined by the demarcation line (and additional territories elsewhere) were detached from Hungary through the 1920 Treaty of Trianon

The Treaty of Trianon (french: Traité de Trianon, hu, Trianoni békeszerződés, it, Trattato del Trianon) was prepared at the Paris Peace Conference and was signed in the Grand Trianon château in Versailles on 4 June 1920. It forma ...

.

Background

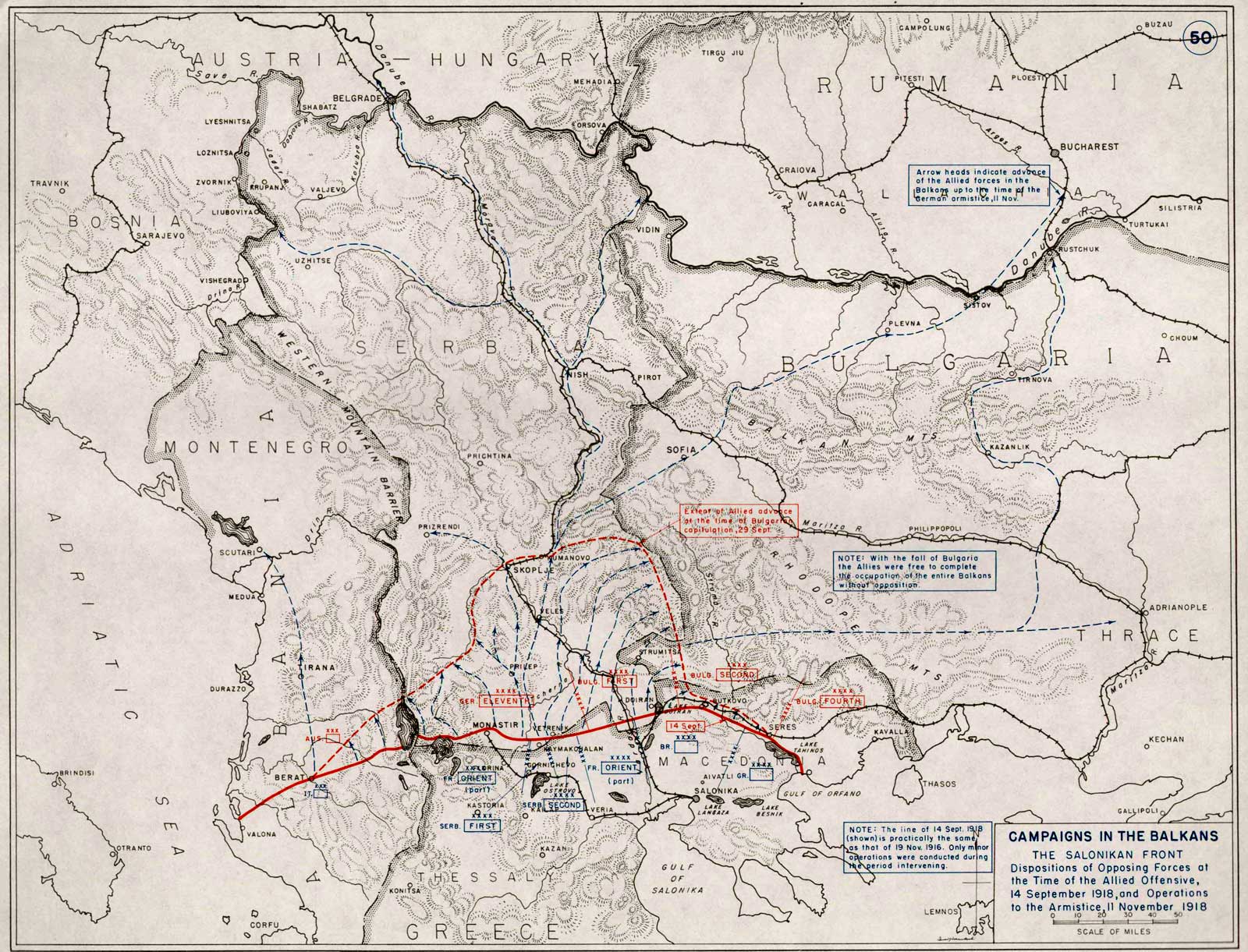

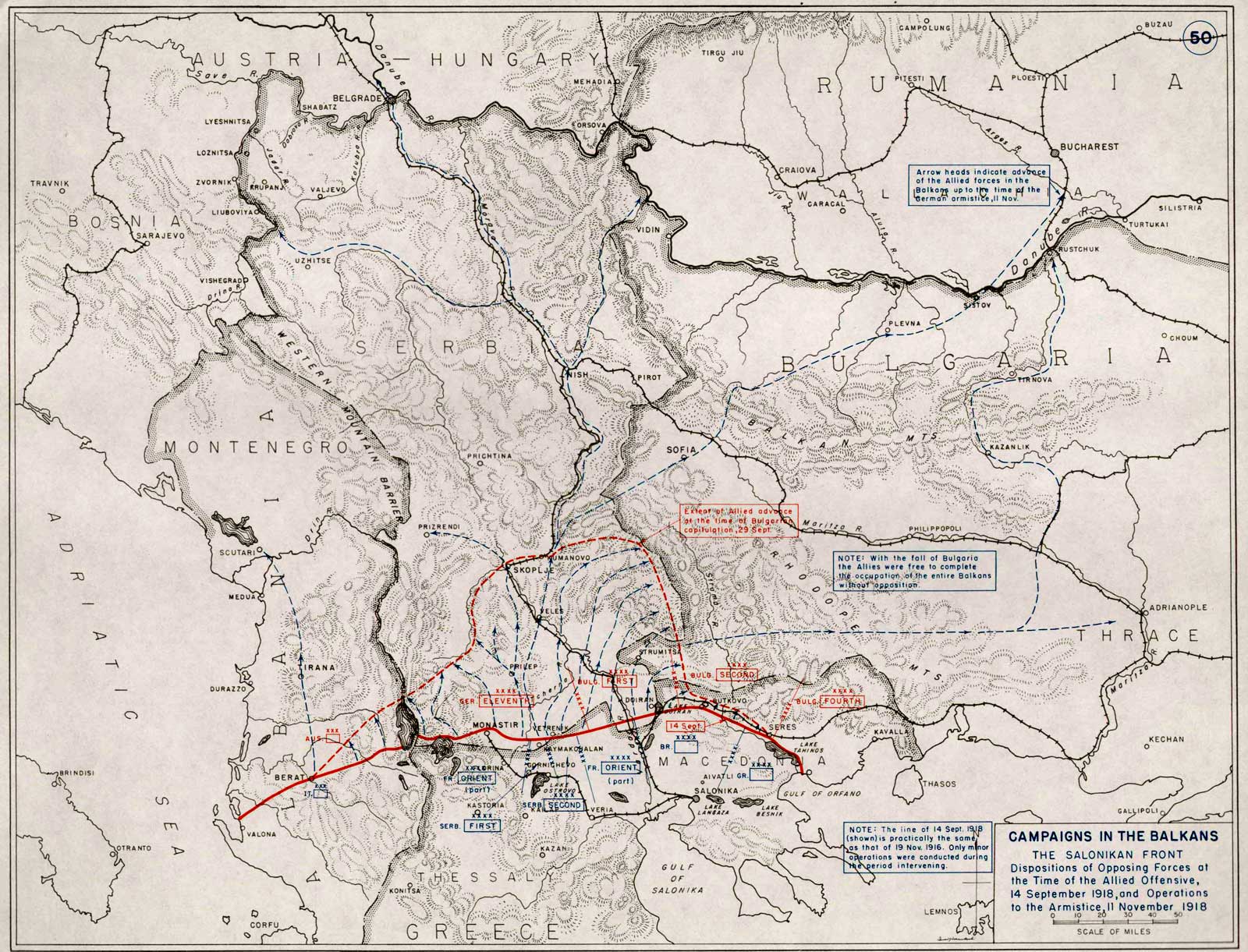

On 29 September 1918, in the final stages of

On 29 September 1918, in the final stages of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

signed the armistice of Salonica

The Armistice of Salonica (also known as the Armistice of Thessalonica) was signed on 29 September 1918 between Bulgaria and the Allied Powers in Thessaloniki. The convention followed a request by the Bulgarian government for a ceasefire on 2 ...

following the collapse of its defensive positions at the Macedonian front

The Macedonian front, also known as the Salonica front (after Thessaloniki), was a military theatre of World War I formed as a result of an attempt by the Allies of World War I, Allied Powers to aid Kingdom of Serbia, Serbia, in the autumn of 191 ...

and withdrew from the war. The Allied Army of the Orient, commanded by French General

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". O ...

Louis Franchet d'Espèrey

Louis Félix Marie François Franchet d'Espèrey (25 May 1856 – 8 July 1942) was a French general during World War I. As commander of the large Allied army based at Salonika, he conducted the successful Macedonian campaign, which caused t ...

, rapidly advanced north as a result, recapturing ground that had been lost to the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in W ...

in 1915. By 1 November, the Serbian First Army

The Serbian First Army (Српска Прва Армија / Srpska Prva Armija) was a Serbian field army that fought during World War I.

Order of battle

August 1914

*First Army - staff in the village Rača

**I Timok Infantry Division - Smed ...

under '' vojvoda'' Petar Bojović

Petar Bojović (, ; 16 July 1858 – 19 January 1945) was a Serbian military commander who fought in the Serbo-Turkish War, the Serbo-Bulgarian War, the First Balkan War, the Second Balkan War, World War I and World War II. Following the ...

and the French '' Armée d'Orient'', led by General Paul Prosper Henrys

Paul Prosper Henrys (or Paul-Prosper) (13 March 1862 – 6 November 1943) was a French general.

In his early career, Henrys was stationed in French Algeria. In 1912, he participated in the French conquest of Morocco under general Hubert Lyautey. ...

, reached Belgrade

Belgrade ( , ;, ; names in other languages) is the capital and largest city in Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers and the crossroads of the Pannonian Plain and the Balkan Peninsula. Nearly 1,166,763 mi ...

. Once there, the troops stopped to rest, with only minimal forces deployed across the Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

and Sava

The Sava (; , ; sr-cyr, Сава, hu, Száva) is a river in Central and Southeast Europe, a right-bank and the longest tributary of the Danube. It flows through Slovenia, Croatia and along its border with Bosnia and Herzegovina, and finally t ...

rivers, which represented Serbia's pre-war border with Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

. The liberation of Serbia was largely complete.

By the second half of October 1918, Austria-Hungary was rapidly disintegrating, despite Charles I of Austria

Charles I or Karl I (german: Karl Franz Josef Ludwig Hubert Georg Otto Maria, hu, Károly Ferenc József Lajos Hubert György Ottó Mária; 17 August 18871 April 1922) was Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary (as Charles IV, ), King of Croati ...

's offer to federalise the empire. In the Lands of the Crown of Saint Stephen

The Lands of the Crown of Saint Stephen ( hu, a Szent Korona Országai), informally Transleithania (meaning the lands or region "beyond" the Leitha River) were the Hungarian territories of Austria-Hungary, throughout the latter's entire exis ...

(the Hungarian part of the dual monarchy), the government was deposed as a result of the 28–31 October Aster Revolution

The Aster Revolution or Chrysanthemum Revolution ( hu, Őszirózsás forradalom) was a revolution in Hungary led by Count Mihály Károlyi in the aftermath of World War I which resulted in the foundation of the short-lived First Hungarian Peop ...

, and then replaced by the Hungarian National Council The Hungarian National Council ( hu, Magyar Nemzeti Tanács) was an institution from the time of transition from the Kingdom of Hungary (part of Austria-Hungary) to the People's Republic in 1918. At the congress of the Hungarian Social Democratic Pa ...

, which was led by Mihály Károlyi. Due to his pacifist

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campai ...

views, Károlyi was the most popular Hungarian politician at the time. On 29 October, the Sabor

The Croatian Parliament ( hr, Hrvatski sabor) or the Sabor is the unicameral legislature of the Republic of Croatia. Under the terms of the Croatian Constitution, the Sabor represents the people and is vested with legislative power. The Sabo ...

of Croatia-Slavonia

The Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia ( hr, Kraljevina Hrvatska i Slavonija; hu, Horvát-Szlavónország or ; de-AT, Königreich Kroatien und Slawonien) was a nominally autonomous kingdom and constitutionally defined separate political nation with ...

broke its legal ties with Austria-Hungary, and the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs

The State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs ( sh, Država Slovenaca, Hrvata i Srba / ; sl, Država Slovencev, Hrvatov in Srbov) was a political entity that was constituted in October 1918, at the end of World War I, by Slovenes, Croats and Serbs ( ...

(comprising the South Slavic-inhabited Habsburg lands

The Habsburg monarchy (german: Habsburgermonarchie, ), also known as the Danubian monarchy (german: Donaumonarchie, ), or Habsburg Empire (german: Habsburgerreich, ), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities ...

) became independent. As the newly proclaimed authorities seized power, violence became widespread outside the capitals. Tens of thousands of army deserters, known as Green Cadres

The Green Cadres,, ''Zeleni kader''; cz, Zelené kádry; german: Grüner Kader or sometimes referred to as; Green Brigades or Green Guards, were originally groups of Austro-Hungarian Army deserters in the First World War. They were later joi ...

, resorted to banditry and looting for survival. Representatives of the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs met with Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia ( Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin and the Balkans. It shares land borders with Hu ...

n Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

Nikola Pašić

Nikola Pašić ( sr-Cyrl, Никола Пашић, ; 18 December 1845 – 10 December 1926) was a Serbian and Yugoslav politician and diplomat who was a leading political figure for almost 40 years. He was the leader of the People's Radical ...

in Geneva on 6–9 November to discuss the creation of a unified South Slavic state, which even then was sometimes referred to as Yugoslavia.

Prelude

Austria-Hungary signed the

Austria-Hungary signed the armistice of Villa Giusti

The Armistice of Villa Giusti or Padua ended warfare between Italy and Austria-Hungary on the Italian Front during World War I. The armistice was signed on 3 November 1918 in the Villa Giusti, outside Padua in the Veneto, Northern Italy, a ...

with Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

on 3 November. The same day Bojović informed the Serbian Supreme Command that lieutenant colonels Koszlovány and Dormanti, attached to the Hungarian general staff, had reached the ''Dunav'' Division's headquarters on authority of ''Generalfeldmarschall

''Generalfeldmarschall'' (from Old High German ''marahscalc'', "marshal, stable master, groom"; en, general field marshal, field marshal general, or field marshal; ; often abbreviated to ''Feldmarschall'') was a rank in the armies of several ...

'' Hermann Kövess von Kövessháza, with offers of an armistice. This information was then forwarded to d'Espèrey, who provided the Chief-of-staff of the Serbian Supreme Command, ''vojvoda'' Živojin Mišić

Field Marshal Živojin Mišić ( sr-cyrl, Живојин Мишић; 19 July 1855 in Struganik – 20 January 1921 in Belgrade) was a Field Marshal who participated in all of Serbia's wars from 1876 to 1918. He directly commanded the First Se ...

, with a list of six conditions to be demanded from Hungary before any negotiations could commence. They included the disarmament and withdrawal of Hungarian forces from a zone extending from the pre-war Serbian and Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

n borders, the surrender of all vessels on the Danube, Sava, and Drina

The Drina ( sr-Cyrl, Дрина, ) is a long Balkans river, which forms a large portion of the border between Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia. It is the longest tributary of the Sava River and the longest karst river in the Dinaric Alps whi ...

rivers and in the Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) to th ...

, and the supply of a delegate authorised to discuss the terms of the armistice. Mišić replied to d'Espèrey with a demand that Austro-Hungarian forces should evacuate from all territories reserved for a future South Slavic state, and requested that the Serbian Army be allowed to occupy the Banat

Banat (, ; hu, Bánság; sr, Банат, Banat) is a geographical and historical region that straddles Central and Eastern Europe and which is currently divided among three countries: the eastern part lies in western Romania (the counties of ...

and Bačka

Bačka ( sr-cyrl, Бачка, ) or Bácska () is a geographical and historical area within the Pannonian Plain bordered by the river Danube to the west and south, and by the river Tisza to the east. It is divided between Serbia and Hunga ...

regions up to the Mureș– Baja–Subotica

Subotica ( sr-cyrl, Суботица, ; hu, Szabadka) is a city and the administrative center of the North Bačka District in the autonomous province of Vojvodina, Serbia. Formerly the largest city of Vojvodina region, contemporary Subotica i ...

–Pécs

Pécs ( , ; hr, Pečuh; german: Fünfkirchen, ; also known by other #Name, alternative names) is List of cities and towns of Hungary#Largest cities in Hungary, the fifth largest city in Hungary, on the slopes of the Mecsek mountains in the countr ...

line. He noted that Serbia had been promised these areas following the 1915 Treaty of London.

In view of this development, Mišić directed Bojović to continue advancing north to capture Banat south of the Mureș River, and west of the line about east of Bela Crkva

Bela Crkva ( sr-cyrl, Бела Црква, ; german: Weißkirchen; hu, Fehértemplom; ro, Biserica Albă) is a town and municipality located in the South Banat District of the autonomous province of Vojvodina, Serbia. The town has a populatio ...

, Vršac

Vršac ( sr-cyr, Вршац, ; hu, Versec; ro, Vârșeț) is a city and the administrative centre of the South Banat District in the autonomous province of Vojvodina, Serbia. As of 2011, the city urban area had a population of 35,701, while ...

, and Timișoara

), City of Roses ( ro, Orașul florilor), City of Parks ( ro, Orașul parcurilor)

, image_map = Timisoara jud Timis.svg

, map_caption = Location in Timiș County

, pushpin_map = Romania#Europe

, pushpin_ ...

. He also instructed Bojović to capture Bačka south of the Baja–Subotica line. Both the First and the Second

The second (symbol: s) is the unit of time in the International System of Units (SI), historically defined as of a day – this factor derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes and finally to 60 seconds ea ...

armies were instructed in less precise terms to advance west to Syrmia

Syrmia ( sh, Srem/Срем or sh, Srijem/Сријем, label=none) is a region of the southern Pannonian Plain, which lies between the Danube and Sava rivers. It is divided between Serbia and Croatia. Most of the region is flat, with the exc ...

, Slavonia

Slavonia (; hr, Slavonija) is, with Dalmatia, Croatia proper, and Istria, one of the four historical regions of Croatia. Taking up the east of the country, it roughly corresponds with five Croatian counties: Brod-Posavina, Osijek-Bar ...

, Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = " Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capi ...

, Bosnia

Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sh, / , ), abbreviated BiH () or B&H, sometimes called Bosnia–Herzegovina and Pars pro toto#Geography, often known informally as Bosnia, is a country at the crossroads of Southern Europe, south and southeast Euro ...

, Herzegovina

Herzegovina ( or ; sh-Latn-Cyrl, Hercegovina, separator=" / ", Херцеговина, ) is the southern and smaller of two main geographical region of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the other being Bosnia. It has never had strictly defined geogra ...

, and Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see names in other languages) is one of the four historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of the Adriatic Sea, str ...

; Serbian troops started heading towards these regions on 5 November. The same day, d'Espèrey learned of the armistice of Villa Giusti and sent a telegram to Paris asking if he should continue negotiations or simply apply the terms of the existing agreement to his area of responsibility.

Negotiations

Károlyi–d'Espèrey talks

On 6 November, Károlyi led a delegation consisting of the Minister for Nationalities,

On 6 November, Károlyi led a delegation consisting of the Minister for Nationalities, Oszkár Jászi

Oszkár Jászi (born Oszkár Jakobuvits; 2 March 1875 – 13 February 1957), also known in English as Oscar Jászi, was a Hungarian social scientist, historian, and politician.

Early life

Oszkár Jászi was born in Nagykároly on March 2, ...

, Hungarian National Council representative Ferenc Hatvany

Baron Ferenc Hatvany (29 October 1881 – 7 February 1958) was a Hungarian painter and art collector. A son of Sándor Hatvany-Deutsch and a member of the , he graduated in the Académie Julian in Paris. His collection included paintings by Ti ...

, Workers' and Soldiers' councils representatives Dezső Bokányi and , and Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

's office secretary Bakony. They were accompanied by 12 journalists from Budapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population o ...

– travelling by train to Subotica and then to Novi Sad

Novi Sad ( sr-Cyrl, Нови Сад, ; hu, Újvidék, ; german: Neusatz; see below for other names) is the second largest city in Serbia and the capital of the autonomous province of Vojvodina. It is located in the southern portion of the P ...

, where they boarded the ''SS Millenium'', which took them to Belgrade. The group also included a French interpreter. Károlyi hoped to save as much of the former Lands of the Crown of Saint Stephen as possible. He hoped the Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French '' entente'' meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland as well a ...

would by sympathetic to his government on account of his wartime declarations against the war and alliance with Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

– and perceive Hungary as a neutral, friendly nation.

The day when the Hungarian delegates arrived, d'Espèrey received orders to continue negotiations while applying provisions of the armistice of Villa Giusti. He went to Niš

Niš (; sr-Cyrl, Ниш, ; names in other languages) is the third largest city in Serbia and the administrative center of the Nišava District. It is located in southern part of Serbia. , the city proper has a population of 183,164, whi ...

, where he had talks with Mišić and Regent Alexander regarding the upcoming talks with Károlyi, with a particular emphasis placed on the demarcation line

{{Refimprove, date=January 2008

A political demarcation line is a geopolitical border, often agreed upon as part of an armistice or ceasefire.

Africa

* Moroccan Wall, delimiting the Moroccan-controlled part of Western Sahara from the Sahrawi ...

.

On 7 November, d'Espèrey arrived in Belgrade accompanied by the chief operating officer

A chief operating officer or chief operations officer, also called a COO, is one of the highest-ranking executive positions in an organization, composing part of the " C-suite". The COO is usually the second-in-command at the firm, especially if ...

of the Serbian Supreme Command, Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge ...

Danilo Kalafatović. D'Espèrey summoned Károlyi and the rest of the delegation to his residence at 7:00 p.m. to start negotiations. While the two were travelling to Belgrade, a telegram was sent from Paris to d'Espèrey instructing him to discuss only the implementation of the armistice of Villa Giusti and to forego any discussion of political matters. This message was forwarded to Belgrade via Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its metropolitan area, and the capital of the geographic region of ...

, Skopje

Skopje ( , , ; mk, Скопје ; sq, Shkup) is the capital and largest city of North Macedonia. It is the country's political, cultural, economic, and academic centre.

The territory of Skopje has been inhabited since at least 4000 BC; r ...

and Niš where it was intercepted by the assistant Chief of Staff of the Serbian Supreme Command, Colonel . He forwarded the telegram to Kalafatović along with a separate telegram from Mišić asking Kalafatović not to hand the message to d'Espèrey until after the negotiations were completed. Pešić later sent another telegram to Kalafatović instructing him to tell d'Espèrey that in case he had agreed to a demarcation line further south than the Timișoara–Sombor

Sombor ( sr-Cyrl, Сомбор, ; hu, Zombor; rue, Зомбор, Zombor) is a city and the administrative center of the West Bačka District in the autonomous province of Vojvodina, Serbia. The city has a total population of 47,623 (), while ...

line, Serbia would continue the war against Hungary alone. Kalafatović never showed d'Espèrey the last telegram because the line agreed between him and Alexander in Niš was ultimately included in the terms.

Károlyi offered to agree to a cessation of hostilities and to implement a neutral foreign policy. D'Espèrey presented him with 18 conditions for the armistice, explaining that he considered Hungary a defeated power. Károlyi stated he could not accept d'Espèrey's terms and expect not to be executed upon returning to Budapest. He asked permission to send a telegram to French Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

Georges Clemenceau

Georges Benjamin Clemenceau (, also , ; 28 September 1841 – 24 November 1929) was a French statesman who served as Prime Minister of France from 1906 to 1909 and again from 1917 until 1920. A key figure of the Independent Radicals, he was a ...

, which was reluctantly granted by d'Espèrey. In the message, Károlyi explained he could only accept the terms of the armistice if the territorial integrity of Hungary was preserved – except in terms of Croatia-Slavonia, which he was willing to relinquish. At 10:30 p.m., the meeting was suspended for dinner and resumed for another 90 minutes at midnight. Károlyi then returned to Budapest, leaving two members of the delegation in Belgrade to await Clemenceau's reply.

Approval and signing of the agreement

Károlyi reported on the negotiations at a cabinet meeting on 8 November, noting the amount of horses and rolling stock demanded by the Allies for transportation. He also reported that the administration of the country (including south of the demarcation line) would be left to Hungary. The cabinet decided to wait for Clemenceau to reply before acting any further. That day, the Serbian ''Drina'' Division was tasked with occupying Syrmia and a part of Slavonia east of the Brod–

Károlyi reported on the negotiations at a cabinet meeting on 8 November, noting the amount of horses and rolling stock demanded by the Allies for transportation. He also reported that the administration of the country (including south of the demarcation line) would be left to Hungary. The cabinet decided to wait for Clemenceau to reply before acting any further. That day, the Serbian ''Drina'' Division was tasked with occupying Syrmia and a part of Slavonia east of the Brod–Osijek

Osijek () is the fourth-largest city in Croatia, with a population of 96,848 in 2021. It is the largest city and the economic and cultural centre of the eastern Croatian region of Slavonia, as well as the administrative centre of Osijek-Baranja ...

–Pécs line.

Clemenceau's reply to Károlyi's messages arrived in Belgrade on 9 November. D'Espèrey was instructed to discuss military matters only and leave the political matters to others. He then left Kalafatić to forward the message to the remaining Hungarian delegates. The two returned to Budapest the night of 9–10 November, and d'Espèrey left to Niš for a conference with Mišić and Henrys before proceeding to Thessaloniki. On 9 November, a unit of former prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of w ...

led by Serbian Army Major

Major ( commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicato ...

Vojislav Bugarski captured Novi Sad unopposed, and a different unit captured Vršac

Vršac ( sr-cyr, Вршац, ; hu, Versec; ro, Vârșeț) is a city and the administrative centre of the South Banat District in the autonomous province of Vojvodina, Serbia. As of 2011, the city urban area had a population of 35,701, while ...

the following day.

In Thessaloniki, d'Espèrey urged the Romanian government to enter the war on the side of the Allies, and they complied – ordering mobilisation on 10 November and commencing hostilities the next day. On 11 November, Bugarski forwarded Kalafatović a message he was given by a Hungarian officer stating that the Hungarian National Council had accepted Clemenceau's terms and that Minister of War Béla Linder

Béla Linder ( Majs, 10 February 1876 – Belgrade, 15 April 1962), Hungarian colonel of artillery, Secretary of War of Mihály Károlyi government, minister without portfolio of Dénes Berinkey government, military attaché of Hungarian Sovie ...

was arriving that day to Belgrade to sign the agreement. The message was then relayed to d'Espèrey in Thessaloniki. He authorised Henrys to sign the agreement as revised by Clemenceau on behalf of the Allies, together with Mišić.

After learning of the armistice of 11 November 1918

The Armistice of 11 November 1918 was the armistice signed at Le Francport near Compiègne that ended fighting on land, sea, and air in World War I between the Entente and their last remaining opponent, Germany. Previous armistices ...

and that it applied to Hungary as well, Mišić again instructed Bojović to advance as far east in Banat as possible towards the Orșova

Orșova (; german: Orschowa, hu, Orsova, sr, Оршава/Oršava, bg, Орсово, pl, Orszawa, cs, Oršava, tr, Adakale) is a port city on the Danube river in southwestern Romania's Mehedinți County. It is one of four localities in the ...

–Lugoj

Lugoj (; hu, Lugos; german: Lugosch; sr, Лугош, Lugoš; bg, Лугож; tr, Logoş) is a city in Timiș County, Romania. The Timiș River divides the city into two halves, the so-called "Romanian Lugoj" that spreads on the right bank and t ...

– Timișoara line regardless of the presence of any Allied forces there. The armistice signatories met in the building of the State Direction of Funds in Belgrade at 9:00 p.m. on 13 November. No further changes were discussed regarding the text, except the time of cessation of hostilities. Originally, the draft stipulated a time 24 hours after the signing of the agreement, but Linder insisted that hostilities had already ceased. Henrys accepted his view and Mišić then complied as well. The agreement was signed by Mišić, Henrys, and Linder at 11:15 p.m.

Terms

Someș

The Someș (; hu, Szamos; german: Somesch or ''Samosch'') is a left tributary of the Tisza in Hungary and Romania. It has a length of (including its source river Someșul Mare), of which 50 km are in Hungary.Bistrița

(; german: link=no, Bistritz, archaic , Transylvanian Saxon: , hu, Beszterce) is the capital city of Bistrița-Năsăud County, in northern Transylvania, Romania. It is situated on the Bistrița River. The city has a population of approxima ...

, then south to the Mureș River and along its course to confluence with the Tisza

The Tisza, Tysa or Tisa, is one of the major rivers of Central and Eastern Europe. Once, it was called "the most Hungarian river" because it flowed entirely within the Kingdom of Hungary. Today, it crosses several national borders.

The Tisza be ...

from where it proceeded west to Subotica, Baja, and Pécs before reaching the Drava and the border with Croatia-Slavonia. It stipulated that the Allies would occupy the territory south and east of the line, with Hungarian police and gendarmerie units remaining in numbers sufficient to maintain public order and some army units being used to guard railways. The ninth point required the surrender of weapons and other materiel

Materiel (; ) refers to supplies, equipment, and weapons in military supply-chain management, and typically supplies and equipment in a commercial supply chain context.

In a military context, the term ''materiel'' refers either to the spec ...

at places designated by the Allies for potential use by units they may establish. The tenth called for the immediate release of Allied prisoners of war and the continued captivity of Hungarian prisoners of war.

The second point limited the size of the Hungarian Armed Forces

The Hungarian Defence Forces ( hu, Magyar Honvédség) is the national defence force of Hungary. Since 2007, the Hungarian Armed Forces is under a unified command structure. The Ministry of Defence maintains the political and civil control over ...

to six infantry and two cavalry divisions. The third point allowed the Allies to occupy any location in Hungary and use all means of transport for military purposes. Under the eleventh and the sixteenth points, German troops present on Hungarian soil were given until 18 November to depart. Hungary would void all commitments to Germany and forbid the transportation of troops and arms and prevent any military telegraphic communications with Germany. The fourteenth point placed all post and telegraph offices under Allied control. Furthermore, under the seventh point, Hungary was required to provide a detachment of telegraphists and material required to repair postal and telegraph service in Serbia.

Points four through six and eight determined the number of horses, rolling stock

The term rolling stock in the rail transport industry refers to railway vehicles, including both powered and unpowered vehicles: for example, locomotives, freight and passenger cars (or coaches), and non-revenue cars. Passenger vehicles ca ...

, ships, tugboat

A tugboat or tug is a marine vessel that manoeuvres other vessels by pushing or pulling them, with direct contact or a tow line. These boats typically tug ships in circumstances where they cannot or should not move under their own power, su ...

s, and barge

Barge nowadays generally refers to a flat-bottomed inland waterway vessel which does not have its own means of mechanical propulsion. The first modern barges were pulled by tugs, but nowadays most are pushed by pusher boats, or other vessels. ...

s to be placed at the disposal of the Allied commander in Thessaloniki or as indemnity for Serbian war losses, as well as the supply of railway personnel for the same. The same provisions required the surrender of all river monitor

River monitors are military craft designed to patrol rivers.

They are normally the largest of all riverine warships in river flotillas, and mount the heaviest weapons. The name originated from the US Navy's , which made her first appearance in ...

s. Point thirteen required Hungary to inform the Allies of the location of mines in the Danube and the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

and to clear them from Hungarian waterways.

The twelfth point required that Hungary contribute to the maintenance of the Allied occupation forces, allowing requisitioning at market prices. Under the fifteenth point, an Allied representative was to be attached to the Hungarian Ministry of Food to protect Allied interests. Concurrently, under the seventeenth point, the Allies vowed not to interfere with the internal administration of Hungary. The final point stated that hostilities between Hungary and the Allies had ceased.

Aftermath

Departures from the agreement

Charles I abdicated on 13 November, and days later, the

Charles I abdicated on 13 November, and days later, the First Hungarian Republic

The First Hungarian Republic ( hu, Első Magyar Köztársaság), until 21 March 1919 the Hungarian People's Republic (), was a short-lived unrecognized country, which quickly transformed into a small rump state due to the foreign and military ...

was proclaimed with Károlyi still at the helm. Henrys set up a French military mission to supervise the implementation of the armistice and deployed it to Budapest. It was led by Brevet Lieutenant Colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colon ...

otherwise assigned to Henrys's staff. It consisted of twelve officers and forty-five enlisted men who arrived at Budapest on 26 November. In addition to the implementation of the agreement, Vix was tasked with gathering intelligence on economic and military matters. Within 24 hours, Vix was sent orders to obtain Hungarian withdrawal from areas of present-day Slovakia, in violation of the armistice of Belgrade, to enforce a claim by Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

directed through French Foreign Minister Stephen Pichon. The Serbian Army occupied Subotica on the day of the armistice, but proceeded to capture Pécs the following day, as well as Timișoara, Orșova, and Lugoj on 15 November. It went on to occupy Sombor and Senta

Senta ( sr-cyrl, Сента, ; Hungarian: ''Zenta'', ; Romanian: ''Zenta'') is a town and municipality located in the North Banat District of the autonomous province of Vojvodina, Serbia. It is situated on the bank of the Tisa river in the g ...

on 16 November, and the part of Arad on the south bank Mureș on 21 November. The Serbian Army thereby completed the occupation of Banat, thus abolishing the Banat Republic

The Banat Republic (german: Banater Republik, hu, Bánáti Köztársaság or ''Bánsági Köztársaság'', ro, Republica bănățeană or ''Republica Banatului'', sr, Банатска република, ) was a short-lived state proclaimed ...

which had been proclaimed only days earlier. In early December, the commander of the French forces in Romania, General Henri Mathias Berthelot

Henri Mathias Berthelot (7 December 1861 – 29 January 1931) was a French general during World War I. He held an important staff position under Joseph Joffre, the French commander-in-chief, at the First Battle of the Marne, before later command ...

, informed Vix that Romanian troops would advance to the Satu Mare

Satu Mare (; hu, Szatmárnémeti ; german: Sathmar; yi, סאטמאר or ) is a city with a population of 102,400 (2011). It is the capital of Satu Mare County, Romania, as well as the centre of the Satu Mare metropolitan area. It lies in the ...

–Carei

Carei (; , ; /, yi, , ) is a city in Satu Mare County, northwestern Romania, near the border with Hungary. The city administers one village, Ianculești ( hu, Szentjánosmajor).

History

The first mention of the city under the name of "Karul ...

–Oradea

Oradea (, , ; german: Großwardein ; hu, Nagyvárad ) is a city in Romania, located in Crișana, a sub-region of Transylvania. The seat of Bihor County, Oradea is one of the most important economic, social and cultural centers in the western par ...

–Békéscsaba

Békéscsaba (; sk, Békešská Čaba; see also other alternative names) is a city with county rights in southeast Hungary, the capital of Békés County.

Geography

Békéscsaba is located in the Great Hungarian Plain, southeast from Budap ...

line on the pretext of protection of Romanian population in the area of Cluj-Napoca

; hu, kincses város)

, official_name=Cluj-Napoca

, native_name=

, image_skyline=

, subdivision_type1 = Counties of Romania, County

, subdivision_name1 = Cluj County

, subdivision_type2 = Subdivisions of Romania, Status

, subdivision_name2 ...

, and then ordered Vix to obtain Hungary's withdrawal from the city of Cluj-Napoca itself. Vix complained about the conflict of authority to Henrys and d'Espèrey as he was also receiving instructions from Berthelot and the Czechoslovak envoy to Hungary, Milan Hodža

Milan Hodža (1 February 1878 – 27 June 1944) was a Slovak politician and journalist, serving from 1935 to 1938 as the prime minister of Czechoslovakia. As a proponent of regional integration, he was known for his attempts to establish a demo ...

. Vix ultimately told Henrys that the armistice of Belgrade was worthless.

On 25 November, only days after the signing of the armistice, the Great People's Assembly of Serbs, Bunjevci and other Slavs in Banat, Bačka and Baranja

The Great People's Assembly of Serbs, Bunjevci and other Slavs in Banat, Bačka and Baranja () or Novi Sad Assembly () was an assembly held in Novi Sad on 25 November 1918, which proclaimed the unification of Banat, Bačka and Baranya with the King ...

was convened in Novi Sad to proclaim the unification of these regions with Serbia. The State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs moved to seize Međimurje – a region predominantly inhabited by Croats

The Croats (; hr, Hrvati ) are a South Slavic ethnic group who share a common Croatian ancestry, culture, history and language. They are also a recognized minority in a number of neighboring countries, namely Austria, the Czech Republic ...

located just north of the demarcation line. The first attempt to occupy Međimurje in mid-November failed, but a second incursion by the Royal Croatian Home Guard resulted in the region's occupation on behalf of the newly established Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes

Kingdom commonly refers to:

* A monarchy ruled by a king or queen

* Kingdom (biology), a category in biological taxonomy

Kingdom may also refer to:

Arts and media Television

* ''Kingdom'' (British TV series), a 2007 British television drama s ...

on 24 December 1918.

According to Jászi, before the armistice, the Hungarian public believed that the Allies would somehow reward Károlyi's pacifist pronouncements. Given that much hope had been placed in the principles of Wilsonianism

Wilsonianism, or Wilsonian idealism, is a certain type of foreign policy advice. The term comes from the ideas and proposals of President Woodrow Wilson. He issued his famous Fourteen Points in January 1918 as a basis for ending World War I and p ...

, the terms of the armistice led to widespread disillusionment. D'Espèrey was perceived as malicious, menacing, and ignorant. Many Hungarians grew bitter, not only because they found the terms of the armistice unjust, but also due to the real and perceived breaches of those terms. The number of discontent people grew further with the return of demobilised Hungarian troops, released prisoners of war and refugees from the occupied territories. The Károlyi government lost further support as it instituted a policy of land reform

Land reform is a form of agrarian reform involving the changing of laws, regulations, or customs regarding land ownership. Land reform may consist of a government-initiated or government-backed property redistribution, generally of agricultura ...

– criticised as too radical by landowners and as half-hearted by others. Discontent conservatives grouped around Károlyi's brother Gyula, whereas discontent former officers were led by Gyula Gömbös

Gyula Gömbös de Jákfa (26 December 1886 – 6 October 1936) was a Hungarian military officer and politician who served as Prime Minister of Hungary from 1 October 1932 to his death.

Background

Gömbös was born in Murga, Tolna County, Kingd ...

. The leader of the Communist Party of Hungary

The Hungarian Communist Party ( hu, Magyar Kommunista Párt, abbr. MKP), known earlier as the Party of Communists in Hungary ( hu, Kommunisták Magyarországi Pártja, abbr. KMP), was a communist party in Hungary that existed during the interwar ...

, Béla Kun

Béla Kun (born Béla Kohn; 20 February 1886 – 29 August 1938) was a Hungarian communist revolutionary and politician who governed the Hungarian Soviet Republic in 1919. After attending Franz Joseph University at Kolozsvár (today Cluj-Napo ...

, appealed to the proletariat

The proletariat (; ) is the social class of wage-earners, those members of a society whose only possession of significant economic value is their labour power (their capacity to work). A member of such a class is a proletarian. Marxist philo ...

.

Hungarian Soviet Republic

In order to address increasingly frequent skirmishes along the Hungarian–Romanian line of control, the Paris Peace Conference decided on 26 February 1919 to allow Romanian troops in an area beyond the demarcation line established by the armistice of Belgrade, and set up an additional neutral zone to be occupied by Allied forces other than Romanians. This established the "temporary frontier" along the Arad–Carei–Satu Mare line. Vix was tasked with presenting the demand to the Hungarian authorities, along with the request that their withdrawal must start on 23 March and be completed within ten days. On 20 March 1919, Hungary was presented with the demand that became known as the

In order to address increasingly frequent skirmishes along the Hungarian–Romanian line of control, the Paris Peace Conference decided on 26 February 1919 to allow Romanian troops in an area beyond the demarcation line established by the armistice of Belgrade, and set up an additional neutral zone to be occupied by Allied forces other than Romanians. This established the "temporary frontier" along the Arad–Carei–Satu Mare line. Vix was tasked with presenting the demand to the Hungarian authorities, along with the request that their withdrawal must start on 23 March and be completed within ten days. On 20 March 1919, Hungary was presented with the demand that became known as the Vix Note

The Vix Note or Vyx Note ( hu, Vix-jegyzék or ) was a communication note sent by (or Vyx), a French lieutenant colonel and delegate of the Entente, to the government of Mihály Károlyi of the First Hungarian Republic of the alliance's intention ...

. In response, Károlyi resigned, and a revolutionary council established by the Social Democratic Party

The name Social Democratic Party or Social Democrats has been used by many political parties in various countries around the world. Such parties are most commonly aligned to social democracy as their political ideology.

Active parties

For ...

and the Communist Party assumed power. The council abolished the First Hungarian Republic, replacing it with the Hungarian Soviet Republic

The Socialist Federative Republic of Councils in Hungary ( hu, Magyarországi Szocialista Szövetséges Tanácsköztársaság) (due to an early mistranslation, it became widely known as the Hungarian Soviet Republic in English-language sources ( ...

. In the summer of 1919, Soviet Hungary fought a war against Czechoslovakia and a war against Romania, resulting in the downfall of the communist regime and the Romanian capture of Budapest on 4 August. France urged the Army of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes to move against the Hungarian Soviet Republic by advancing north from Bačka, but no such military intervention ever took place. In June 1919, Banat was partitioned by the Allies against Romanian complaints that this was contrary to the promise of the entire region being awarded to Romania under the Treaty of Bucharest. By December, the Romanians gave way to diplomatic pressure and agreed to the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes receiving the western part of Banat.

On 12 August, the armed forces of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes occupied Prekmurje

Prekmurje (; dialectically: ''Prèkmürsko'' or ''Prèkmüre''; hu, Muravidék) is a geographically, linguistically, culturally and ethnically defined region of Slovenia, settled by Slovenes and a Hungarian minority, lying between the Mur R ...

. The move had been authorised by the Paris Peace Conference a month earlier as compensation for the kingdom's contribution to the suppression of the Hungarian Soviet Republic. A short-lived republic was proclaimed in Prekmurje in late May, but was suppressed by Hungarian troops in early June.

On 4 June 1920, the Paris Peace Conference produced the Treaty of Trianon

The Treaty of Trianon (french: Traité de Trianon, hu, Trianoni békeszerződés, it, Trattato del Trianon) was prepared at the Paris Peace Conference and was signed in the Grand Trianon château in Versailles on 4 June 1920. It forma ...

as the peace agreement between the Allies and Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Cr ...

. Territorial changes under the treaty awarded Transylvania, Crișana

Crișana ( hu, Körösvidék, german: Kreischgebiet) is a geographical and historical region in north-western Romania, named after the Criș (Körös) River and its three tributaries: the Crișul Alb, Crișul Negru, and Crișul Repede. In Rom ...

, the southern part of Maramureș

or Marmaroshchyna ( ro, Maramureș ; uk, Мармарощина, Marmaroshchyna; hu, Máramaros) is a geographical, historical and cultural region in northern Romania and western Ukraine. It is situated in the northeastern Carpathians, alon ...

and the eastern part of Banat to Romania – exceeding the armistice of Belgrade demarcation line in Romania's favour. The Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes formally received Bačka, the western part of Banat, and the southern part of Baranya – a territory similar to the one specified in the armistice of Belgrade. A Yugoslav-Hungarian Boundary Commission was tasked with defining a definitive delimitation between the two states. From those territories, as well as those lost to Czechoslovakia and Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

, 350,000–400,000 refugees left or fled to Hungary, where subsequently, according to Hungarian author Paul Lendvai

Paul Lendvai (born Lendvai Pál on August 24, 1929) is a Hungarian-born Austrian journalist. He moved to Austria in 1957, where he works as an author and journalist.

Biography

Lendvai was born on August 24, 1929, in Budapest to Jewish parent ...

, they became receptive to extremist and populist views.

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * * {{World War I Treaties concluded in 1918 Treaties entered into force in 1918Belgrade

Belgrade ( , ;, ; names in other languages) is the capital and largest city in Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers and the crossroads of the Pannonian Plain and the Balkan Peninsula. Nearly 1,166,763 mi ...

World War I treaties

Modern history of Hungary

Treaties of Hungary

Hungary–Serbia relations