Anti-Japanese Sentiment In The United States on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States has existed since the late 19th century, especially during the

"Anti-Japanese exclusion movement,"

''Densho Encyclopedia''. Retrieved 15 July 2014. Some cite the formation of the

The most profound cause of anti-Japanese sentiment outside of Asia had its beginning in the

The most profound cause of anti-Japanese sentiment outside of Asia had its beginning in the

Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2003 , p.116 Allied soldiers believed that Japanese soldiers were inclined to feign surrender, in order to make surprise attacks. Therefore, according to Straus, " nior officers opposed the taking of prisoners on the grounds that it needlessly exposed American troops to risks..."

online

* Buell, Raymond Leslie. "The development of the anti-Japanese agitation in the United States." ''Political Science Quarterly'' 37.4 (1922): 605-638

online

* Daniels, Roger. ''The politics of prejudice: The anti-Japanese movement in California and the struggle for Japanese exclusion'' (Univ of California Press, 1977). * MeGovney, Dudley O. "The anti-Japanese land laws of California and ten other states." ''California Law Review'' 35 (1947): 7+ eGovney, Dudley O. "The anti-Japanese land laws of California and ten other states." Calif. L. Rev. 35 (1947): 7. online * Okihiro, Gary. ''Cane fires: The anti-Japanese movement in Hawaii, 1865-1945'' (Temple UP, 1992). * Shim, Doobo. "From yellow peril through model minority to renewed yellow peril." ''Journal of Communication Inquiry'' 22.4 (1998): 385-409

online

* Tamura, Eileen H. "The English-only effort, the anti-Japanese campaign, and language acquisition in the education of Japanese Americans in Hawaii, 1915–40." ''History of Education Quarterly'' 33.1 (1993): 37-58. {{portalbar, Japan, United States Anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States Anti-Japanese sentiment Asian-American issues Asian-American-related controversies Japan–United States relations History of racism in the United States Japanese-American history Racially motivated violence against Asian-Americans Xenophobia White supremacy in the United States

Yellow Peril

The Yellow Peril (also the Yellow Terror and the Yellow Specter) is a racial color metaphor that depicts the peoples of East and Southeast Asia as an existential danger to the Western world. As a psychocultural menace from the Eastern world ...

, which had also extended to other Asian immigrants.

Anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States would peak during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, when they were belligerents in the Pacific War theater. After the war, the rise of Japan as a major economic power, which was seen as a widespread economic threat to the United States and also led to a renewal of anti-Japanese sentiment, known as Japan bashing.

Origins

In theUnited States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

, anti-Japanese sentiment had its beginnings well before World War II. Racial prejudice against Asian immigrants began building soon after Chinese workers started arriving in the country in the mid-19th century, and set the tone for the resistance Japanese would face in the decades to come. Although Chinese were heavily recruited in the mining and railroad industries initially, whites in Western states and territories came to view the immigrants as a source of economic competition and a threat to racial "purity" as their population increased. A network of anti-Chinese groups (many of which would reemerge in the anti-Japanese movement) worked to pass laws that limited Asian immigrants' access to legal and economic equality with whites. Most important of these discriminatory laws was the exclusion of Asians from citizenship rights.

The Naturalization Act of 1870

The Naturalization Act of 1870 () was a United States federal law that created a system of controls for the naturalization process and penalties for fraudulent practices. It is also noted for extending the naturalization process to "aliens of A ...

revised the previous law, under which only white immigrants could become U.S. citizens, to extend eligibility to people of African descent. By designating Asians as permanent aliens, the law prohibited them from voting and serving on juries, which, combined with laws that prevented people of color from testifying against whites in court, made it virtually impossible for Asian Americans to participate in the country's legal and political systems. Also significant were alien land laws

Alien land laws were a series of legislative attempts to discourage Asian and other "non-desirable" immigrants from settling permanently in U.S. states and territories by limiting their ability to own land and property. Because the Naturalization ...

, which relied on coded language barring "aliens ineligible for citizenship" from owning land or real estate, and in some cases from even entering into a temporary lease, to discourage Asian immigrants from establishing homes and businesses in over a dozen states. These laws were greatly detrimental to the newly arrived immigrants, since many of them were farmers and had little choice but to become migrant workers.

After the Chinese Exclusion Act

The Chinese Exclusion Act was a United States federal law signed by President Chester A. Arthur on May 6, 1882, prohibiting all immigration of Chinese laborers for 10 years. The law excluded merchants, teachers, students, travelers, and diplo ...

of 1882 stopped immigration from China, American labor recruiters began targeting Japanese workers, triggering a rapid increase in the country's Japanese population, which in turn triggered the movement to decrease their number and restrict their economic and political power.Anderson, Emily"Anti-Japanese exclusion movement,"

''Densho Encyclopedia''. Retrieved 15 July 2014. Some cite the formation of the

Asiatic Exclusion League

The Asiatic Exclusion League (often abbreviated AEL) was an organization formed in the early 20th century in the United States and Canada that aimed to prevent immigration of people of Asian origin.

United States

In May 1905, a mass meeting was h ...

as the start of the anti-Japanese movement in California, where, along with the Japanese American population, the exclusion movement was centered. Their efforts focused on ending Japanese immigration and, as with the previous anti-Chinese movement, nativist groups like the Asiatic Exclusion League lobbied to limit and finally, with the Immigration Act of 1924

The Immigration Act of 1924, or Johnson–Reed Act, including the Asian Exclusion Act and National Origins Act (), was a United States federal law that prevented immigration from Asia and set quotas on the number of immigrants from the Eastern ...

, ban Japanese and other East Asians from entering the U.S. However, in the process they created an atmosphere of systematic hostility and discrimination that would later contribute to the push to incarcerate 120,000 Japanese Americans during World War II.

Early 20th century

Anti-Japanese racism and fear of theYellow Peril

The Yellow Peril (also the Yellow Terror and the Yellow Specter) is a racial color metaphor that depicts the peoples of East and Southeast Asia as an existential danger to the Western world. As a psychocultural menace from the Eastern world ...

had become increasingly xenophobic

Xenophobia () is the fear or dislike of anything which is perceived as being foreign or strange. It is an expression of perceived conflict between an in-group and out-group and may manifest in suspicion by the one of the other's activities, a ...

in California after the Japanese victory over the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

in the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

. On October 11, 1906, the San Francisco, California Board of Education passed a regulation whereby children of Japanese descent would be required to attend racially segregated and separate schools. At the time, Japanese immigrants made up approximately 1% of the population of California; many of them had come under the treaty in 1894 which had assured free immigration from Japan.

In 1907, Californian nativists supporting exclusion of Japanese immigrants and maintenance of segregated schools for Caucasian and Japanese students rioted in San Francisco.

Anti-Japanese organizations

*California Farm Bureau *California Joint Immigration Committee

The California Joint Immigration Committee (CJIC) was a nativist lobbying organization active in the early to mid-twentieth century that advocated exclusion of Asian and Mexican immigrants to the United States.

Background

The CJIC was a succ ...

*Committee of One Thousand

*Japanese Exclusion League of California

*Native Sons and Daughters of the Golden West

*Anti-Japanese League of Washington

Alien land laws

TheCalifornia Alien Land Law of 1913

The California Alien Land Law of 1913 (also known as the Webb–Haney Act) prohibited "aliens ineligible for citizenship" from owning agricultural land or possessing long-term leases over it, but permitted leases lasting up to three years. It affe ...

was specifically created to prevent land ownership among Japanese citizens who were residing in the state of California. In ''State of California v. Jukichi Harada'' (1918), Judge Hugh H. Craig sided with the defendant and ruled that American children - who happened to be born to Japanese parents - had the right to own land. California proceeded to strengthen its Alien land law in 1920 and 1923.Ferguson, Edwin E. 1947. "The California Alien Land Law and the Fourteenth Amendment." California Law Review 35 (1): 61.Kurashige, Scott. 2008. The Shifting Grounds of Race: Black and Japanese Americans in the Making of Multiethnic Los Angeles. Princeton: Princeton University Press.Bunje, Emil T. H. 1957. The Story of Japanese Farming in California. Saratoga, California: Robert D. Reed.

Other states passes similar laws including Washington in 1921 and Oregon in 1923.

In ''State of California v. Oyama'' (1948), the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that California's Alien Land Law was anti-Japanese in concept, and deemed unfit to stand in America's law books. Justices Murphy and Rutledge wrote:

It took four years for California's Supreme Court to concede that the law was unconstitutional, in ''State of California v. Fujii'' (1952). Finally, in 1956, California voters repealed the law.

Anti-Japanese immigration agreements and legislation

In 1907, the Gentlemen's Agreement was an informal deal between the governments of Japan and the U.S. It ended the immigration of Japanese laborers, though it did allow the immigration of spouses and children of Japanese immigrants already in the United States. TheImmigration Act of 1924

The Immigration Act of 1924, or Johnson–Reed Act, including the Asian Exclusion Act and National Origins Act (), was a United States federal law that prevented immigration from Asia and set quotas on the number of immigrants from the Eastern ...

banned the immigration of all but a few token Japanese. Passage of the Immigration Act contributed to the growth of anti-Americanism and ending of a growing democratic movement in Japan during this time period, opening the door to Japanese militarist government control.

Japanese military activity prior to American entry in World War II

The Japanese invasion of China in 1931 and the annexation ofManchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer M ...

was roundly criticized in the US. In addition, efforts by citizens who were outraged by Japanese atrocities

The Empire of Japan committed war crimes in many Asian-Pacific countries during the period of Japanese imperialism, primarily during the Second Sino-Japanese and Pacific Wars. These incidents have been described as an "Asian Holocaust". Some w ...

, such as the Nanjing Massacre

The Nanjing Massacre (, ja, 南京大虐殺, Nankin Daigyakusatsu) or the Rape of Nanjing (formerly romanized as ''Nanking'') was the mass murder of Chinese civilians in Nanjing, the capital of the Republic of China, immediately after the ...

, led to calls for American economic intervention to encourage Japan to leave China; these calls played a role in shaping American foreign policy. As more and more unfavorable reports of Japanese actions came to the attention of the American government, embargoes on oil and other supplies were placed on Japan, out of concern for the safety of the Chinese populace and concern for the safety of American interests in the Pacific.

Furthermore, the European American population became strongly pro-Chinese and strongly anti-Japanese, an example of which was a grass-roots campaign to ask women to stop buying silk stockings, because the material was procured from Japan through its colonies. European traders sought access to Chinese markets and resources. Chinese Americans were again distressed when an estimated 150,000 Taishanese

Taishanese (), alternatively romanized in Cantonese as Toishanese or Toisanese, in local dialect as Hoisanese or Hoisan-wa, is a dialect of Yue Chinese native to Taishan, Guangdong. Although it is related to Cantonese, Taishanese has littl ...

locals died from starvation in Taishan County by the Japanese blockade, as Taishan County was the homeland of most Chinese Americans at that time.

When the Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific Th ...

broke out in 1937, Western public opinion was decidedly pro-China, with eyewitness reports by Western journalists on atrocities committed against Chinese civilians further strengthening anti-Japanese sentiments. African American sentiments at the time could be quite different than the mainstream, with organizations like the Pacific Movement of the Eastern World

The Pacific Movement of the Eastern World (PMEW) was a 1930s North American based pro-Japanese movement of African Americans which promoted the idea that Japan was the champion of all non-white peoples.

The Japanese ultra-nationalist Black Dragon ...

(PMEW) which promised equality and land distribution under Japanese rule. The PMEW had thousands of members hopefully preparing for liberation from white supremacy with the arrival of the Japanese Imperial Army

The was the official ground-based armed force of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945. It was controlled by the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office and the Ministry of the Army, both of which were nominally subordinate to the Emperor ...

.

World War II

The most profound cause of anti-Japanese sentiment outside of Asia had its beginning in the

The most profound cause of anti-Japanese sentiment outside of Asia had its beginning in the attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii ...

, as it propelled the United States into World War II. The Americans were unified by the attack to fight against the Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II Constitution of Japan, 1947 constitu ...

and its allies, the German Reich

German ''Reich'' (lit. German Realm, German Empire, from german: Deutsches Reich, ) was the constitutional name for the German nation state that existed from 1871 to 1945. The ''Reich'' became understood as deriving its authority and sovereignty ...

and the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy ( it, Regno d'Italia) was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia was proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946, when civil discontent led to an institutional referendum to abandon the monarchy and f ...

.

The bombing of Pearl Harbor by Japan on the neutral

Neutral or neutrality may refer to:

Mathematics and natural science Biology

* Neutral organisms, in ecology, those that obey the unified neutral theory of biodiversity

Chemistry and physics

* Neutralization (chemistry), a chemical reaction in ...

United States without warning and the deaths of almost 2,500 people during ongoing U.S./Japanese peace negotiations was presented to the American populace as an act of treachery, barbarism, and cowardice. Following the attack, many non-governmental " Jap hunting licenses" were circulated around the country. ''Life

Life is a quality that distinguishes matter that has biological processes, such as Cell signaling, signaling and self-sustaining processes, from that which does not, and is defined by the capacity for Cell growth, growth, reaction to Stimu ...

'' magazine published an article on how to distinguish a Japanese person from a Chinese person by the shape of the nose and the stature of the body. Japanese conduct during the war did little to quell anti-Japanese sentiment. Fanning the flames of outrage were the treatment of American and other prisoners of war. Military-related outrages included the murder of POWs, the use of POWs as slave labor for Japanese industries, the Bataan Death March

The Bataan Death March (Filipino: ''Martsa ng Kamatayan sa Bataan''; Spanish: ''Marcha de la muerte de Bataán'' ; Kapampangan: ''Martsa ning Kematayan quing Bataan''; Japanese: バターン死の行進, Hepburn: ''Batān Shi no Kōshin'') wa ...

, the kamikaze

, officially , were a part of the Japanese Special Attack Units of military aviators who flew suicide attacks for the Empire of Japan against Allied naval vessels in the closing stages of the Pacific campaign of World War II, intending t ...

attacks on Allied ships, and atrocities committed on Wake Island

Wake Island ( mh, Ānen Kio, translation=island of the kio flower; also known as Wake Atoll) is a coral atoll in the western Pacific Ocean in the northeastern area of the Micronesia subregion, east of Guam, west of Honolulu, southeast of T ...

and elsewhere. The Guadalacanal diary, which was published in 1942, wrote about the accounts of American soldiers, collecting Japanese 'gold teeth' or body parts such as hands or ears, to keep as trophies. The diary became extremely popular within the United States during the Second World war.

U.S. historian James J. Weingartner attributes the very low number of Japanese in U.S. POW compounds to two key factors: a Japanese reluctance to surrender and a widespread American "conviction that the Japanese were 'animals' or 'subhuman' and unworthy of the normal treatment accorded to POWs." The latter reasoning is supported by Niall Ferguson

Niall Campbell Ferguson FRSE (; born 18 April 1964)Biography

Niall Ferguson

, who says that "Allied troops often saw the Japanese in the same way that Germans regarded Russians ic— as Untermenschen." Weingartner believes this explains the fact that a mere 604 Japanese captives were alive in Allied POW camps by October 1944.

Ulrich Straus, a U.S. Niall Ferguson

Japanologist

Japanese studies ( Japanese: ) or Japan studies (sometimes Japanology in Europe), is a sub-field of area studies or East Asian studies involved in social sciences and humanities research on Japan. It incorporates fields such as the study of Japanes ...

, believes that front line troops intensely hated Japanese military personnel and were "not easily persuaded" to take or protect prisoners. They believed that Allied personnel who surrendered got "no mercy" from the Japanese.Ulrich Straus, ''The Anguish Of Surrender: Japanese POWs of World War II'' (excerpts)Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2003 , p.116 Allied soldiers believed that Japanese soldiers were inclined to feign surrender, in order to make surprise attacks. Therefore, according to Straus, " nior officers opposed the taking of prisoners on the grounds that it needlessly exposed American troops to risks..."

Jap hunts

The attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 plunged the United States into war and planted the notion that the Japanese were treacherous and barbaric in the minds of Americans. The hysteria which enveloped the West Coast during the early months of the war, combined with long standing anti-Asian prejudices, set the stage for what was to come. Executive Order 9066 authorized the military to exclude any person from any area of the country where national security was considered threatened. It gave the military broad authority over the civilian population without the imposition ofmartial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

. Although the order did not mention any specific group or recommend detention, its language implied that any citizen might be removed. In practice, the order was applied almost exclusively to Japanese Americans and Japanese nationals, with only few Italian and German Americans suffering similar fates. Ultimately, approximately 110,000 Japanese nationals and Japanese Americans were interned in housing facilities called " War Relocation Camps".Various primary and secondary sources list counts between 110,000 and 120,000 persons.

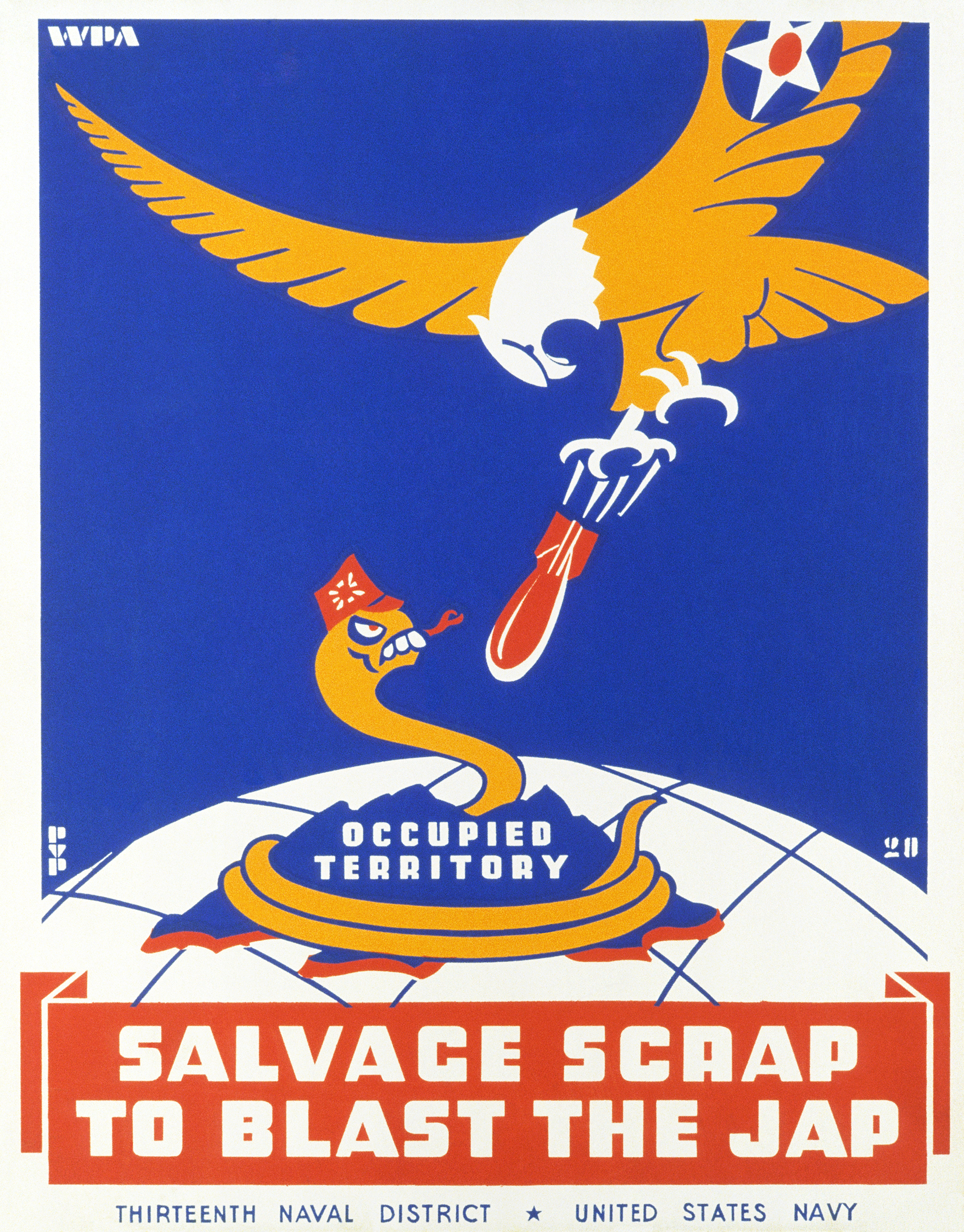

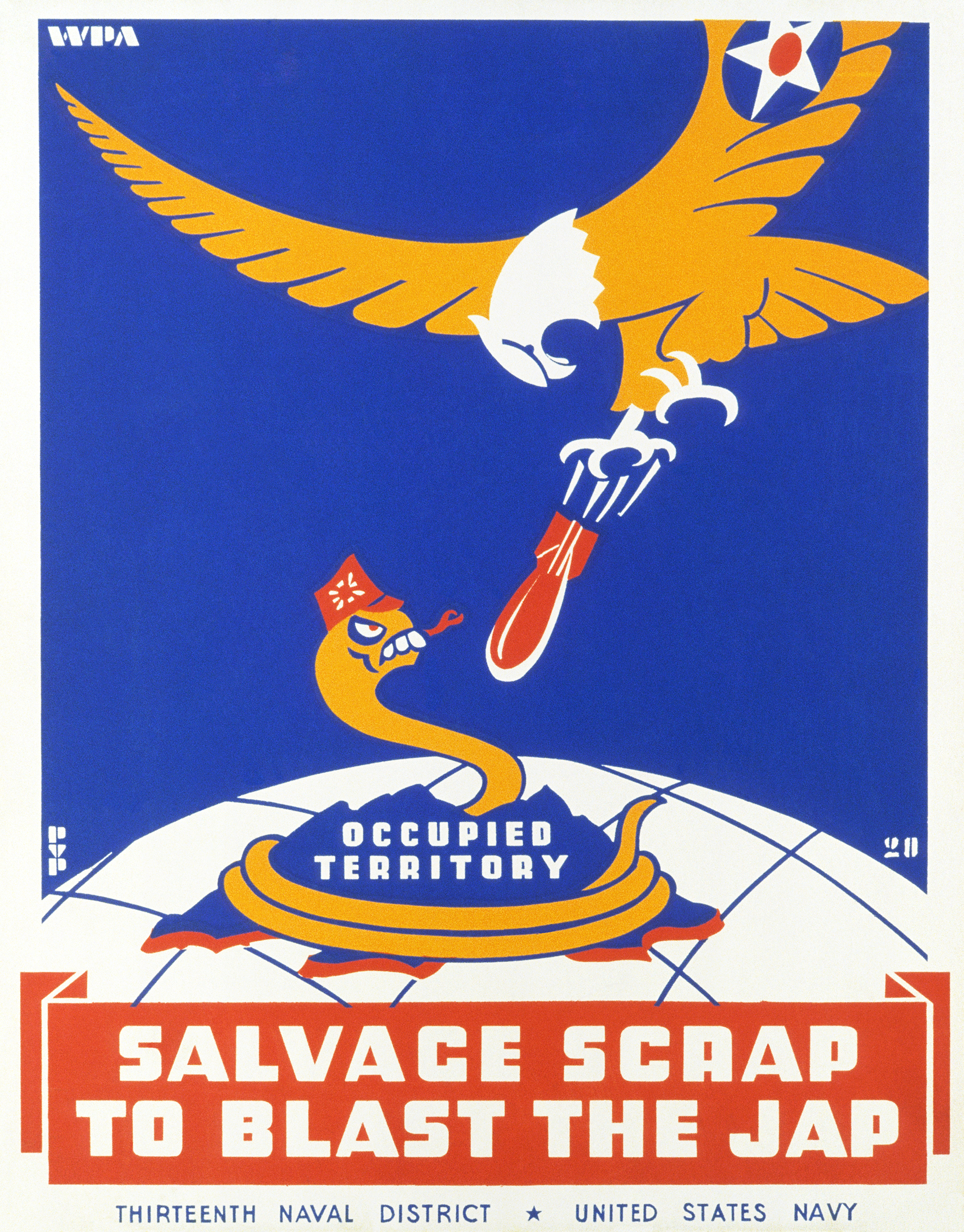

After the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, much anti-Japanese paraphernalia and propaganda surfaced in the United States. An example of this was the so-called "Jap hunting license", a faux-official document, button or medallion that purported to authorize "open season" on "hunting" the Japanese, despite the fact that over a quarter of a million Americans at that time were of Japanese origin. Some reminded holders that there was "no limit" on the number of " Japs" they could "hunt or trap". These "licenses" often characterized Japanese people as sub-human. Many of the "Jap Hunting Licenses", for example, depicted the Japanese in animalistic fashion.

Edmund Russell writes that, whereas in Europe Americans perceived themselves to be struggling against "great individual monsters", such as Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

, Benito Mussolini, and Joseph Goebbels, Americans often saw themselves fighting against a "nameless mass of vermin", in regards to Japan. Russell attributes this to the outrage of Americans in regards to the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the Bataan Death March, the killing of American POWs in the hands of Imperial Japanese forces, and the perceived "inhuman tenacity" demonstrated in the refusal of Imperial forces to surrender. Kamikaze suicide bombings, according to John Morton Blum, were instrumental in confirming this stereotype of the "insane martial spirit" of Imperial Japan, and the bigoted picture it would engender of the Japanese people as a whole.

Commonwealth troops also employed rhetoric of "hunting", in regards to their engagement with Imperial Japanese forces. According to T. R. Moreman, the demonization of the Japanese served "to improve morale, foster belief that the war in the Far East was worthwhile and build the moral component of fighting power". Training instruction issued by the headquarters of 5th Indian Division suggested, "The JAP is a fanatic and therefore a menace until he is dead!... It will be our fanatical aim to KILL JAPS. Hunt him and kill him like any other wild beast!"

US Professor of Japanese History, John Dower, introduces his 'War Hates and War Crimes' by quoting American Historian, Allan Nevins, that 'no foe has been so detested as were the Japanese', in his essay about the Second World War. Dower highlights how the Japanese were more despised than the Germans by the American public, and he claims that it was a result of racial hatred. This racial element separated Japanese and Germans, as Dower presents how Germans could be distinguished as "good" or "bad", whereas the 'savage' and 'brutal' traits associated with the Japanese military in the war, were just seen as being "Japanese". Magazines like ''Time'' hammered this home even further by frequently referring to "the Jap" rather than "Japs", thereby denying the enemy even the merest semblance of pluralism.

Strategic bombing of Japan

Author John M. Curatola wrote that the anti-Japanese sentiment probably played a role in thestrategic bombing

Strategic bombing is a military strategy used in total war with the goal of defeating the enemy by destroying its morale, its economic ability to produce and transport materiel to the theatres of military operations, or both. It is a systematica ...

of Japanese cities, which began on March 9/10, 1945 with the destructive ''Operation Meetinghouse

On the night of 9/10 March 1945, the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) conducted a devastating firebombing raid on Tokyo, the Japanese capital city. This attack was code-named Operation Meetinghouse by the USAAF and is known as the Great To ...

'' firebombing of Tokyo to August 15, 1945, with the surrender of Japan. Sixty-nine cities in Japan lost significant areas and hundreds of thousands of civilian lives to firebombing

Firebombing is a bombing technique designed to damage a target, generally an urban area, through the use of fire, caused by incendiary devices, rather than from the blast effect of large bombs.

In popular usage, any act in which an incendiary d ...

and nuclear attacks from United States Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

B-29 Superfortress

The Boeing B-29 Superfortress is an American four-engined propeller-driven heavy bomber, designed by Boeing and flown primarily by the United States during World War II and the Korean War. Named in allusion to its predecessor, the B-17 F ...

bombers during this period.

According to Curatola and historian James J. Weingartner, both firebombing and nuclear attacks were partially the result of a dehumanization of the enemy, with the latter saying, " e widespread image of the Japanese as sub-human constituted an emotional context which provided another justification for decisions which resulted in the death of hundreds of thousands" across Japan. On the second day after the Nagasaki bomb, President Harry S. Truman stated: "The only language they seem to understand is the one we have been using to bombard them. When you have to deal with a beast you have to treat him like a beast. It is most regrettable but nevertheless true".

Internment of Japanese Americans

An estimated 112,000 to 120,000 Japanese migrants and Japanese Americans from the West Coast were interned regardless of their attitude to the U.S. or Japan. They were held for the duration of the war in the inner U.S. The large Japanese population of Hawaii was not massively relocated in spite of their proximity to vital military areas. In 1942, with the Japanese incarcerated in ten American concentration camps, California Attorney General Earl Warren saw his chance and approved the state takeover of twenty parcels of land held in the name of American children of Japanese parents, ''in absentia''. In 1943, Governor Warren signed a bill that expanded the Alien Land Law by denying the Japanese the opportunity to farm as they had before World War II. In 1945, he followed up by signing two bills that facilitated the seizure of land owned by American descendants of the Japanese. In a December 19, 1944opinion poll

An opinion poll, often simply referred to as a survey or a poll (although strictly a poll is an actual election) is a human research survey of public opinion from a particular sample. Opinion polls are usually designed to represent the opinion ...

, it was found that 13% of the U.S. public were in favor of the extermination of all Japanese, as well as 50% of American GI's. Dower suggests the racial hatred of the front-lines in the war rubbed off onto the American public, through media representation of Japanese and propaganda.

Since World War II

Japan bashing

1970s

During the 1970s to 1980s, growing Americanprotectionism

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulatio ...

and suspicion at the time about the growing Japanese economy and their rapid entry into consumer electronics resulted in high anti-Japanese sentiment known as Japan bashing not seen since World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, when both countries were belligerents in the war. The waning fortunes of heavy industry in the United States prompted layoffs and hiring slowdowns just as counterpart businesses in Japan were making major inroads into U.S. markets. Nowhere was this more visible than in the automobile industry, where the then- lethargic Big Three automobile manufacturers

In the automotive industry, the term Big Three is used for a country's three largest motor vehicle manufacturers, especially indicating companies that sell under multiple brand names.

The term originated in the United States, where General Moto ...

( General Motors, Ford

Ford commonly refers to:

* Ford Motor Company, an automobile manufacturer founded by Henry Ford

* Ford (crossing), a shallow crossing on a river

Ford may also refer to:

Ford Motor Company

* Henry Ford, founder of the Ford Motor Company

* Ford F ...

, and Chrysler) watched as their former customers bought Japanese imports from Honda

is a Japanese public multinational conglomerate manufacturer of automobiles, motorcycles, and power equipment, headquartered in Minato, Tokyo, Japan.

Honda has been the world's largest motorcycle manufacturer since 1959, reaching a producti ...

, Toyota

is a Japanese multinational automotive manufacturer headquartered in Toyota City, Aichi, Japan. It was founded by Kiichiro Toyoda and incorporated on . Toyota is one of the largest automobile manufacturers in the world, producing about 10 ...

and Nissan, a consequence of the 1973 oil crisis. As a result, American–Japanese relations became relatively volatile around this time. Despite being ''de jure'' military allies, economic relations between the two were highly antagonistic, resulting in trade wars.

1980s

Such anti-Japanese sentiment manifested itself in occasional public destruction of Japanese cars. This also led to increased prejudice and violence against anyone perceived to be Japanese, including other Asians. This led to the 1982killing of Vincent Chin

Vincent Jen Chin ( zh, first=t, t=陳果仁; May 18, 1955 – June 23, 1982) was an American draftsman of Chinese descent who was killed in a racially motivated assault by two white men, Chrysler plant supervisor Ronald Ebens and his stepson, ...

, a Chinese American beaten to death when he was assumed to be Japanese. In 1987, a group of US congressmen smashed Toshiba products on Capitol Hill. The event was replayed hundreds of times on Japanese television. Many Japanese were shocked to see how they and their country were being perceived in the West

West or Occident is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic word passed into some ...

, noting its inaccuracies and racial undertone. Most particularly, the Japanese were not particularly fond of the vague accusations, often without merit, that their industries and subsequent economic successes were based upon "stolen technology".

Other highly symbolic deals—including the sale of famous American commercial and cultural symbols such as Columbia Records, Columbia Pictures

Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. is an American film production studio that is a member of the Sony Pictures Motion Picture Group, a division of Sony Pictures Entertainment, which is one of the Big Five studios and a subsidiary of the mu ...

, and the Rockefeller Center

Rockefeller Center is a large complex consisting of 19 commercial buildings covering between 48th Street and 51st Street in Midtown Manhattan, New York City. The 14 original Art Deco buildings, commissioned by the Rockefeller family, span th ...

building to Japanese firms—further fanned anti-Japanese sentiment. When the Seattle Mariners

The Seattle Mariners are an American professional baseball team based in Seattle. They compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the American League (AL) West division. The team joined the American League as an expansion team ...

were being sold to Nintendo, 71 percent of Americans opposed the sale of an American baseball team to a Japanese corporation. Popular culture of the period reflected American's growing distrust of Japan. Futuristic period pieces such as ''Back to the Future Part II

''Back to the Future Part II'' is a 1989 American science fiction film directed by Robert Zemeckis from a screenplay by Bob Gale and a story by both. It is the sequel to the 1985 film '' Back to the Future'' and the second installment in the ...

'' and ''RoboCop 3

''RoboCop 3'' is a 1993 American science fiction action film directed by Fred Dekker and written by Dekker and Frank Miller. It is the sequel to the 1990 film '' RoboCop 2'' and the third entry in the ''RoboCop'' franchise. It stars Robert B ...

'' frequently showed Americans as working precariously under Japanese superiors. Criticism was also lobbied in many novels of the day. Author Michael Crichton took a break from science fiction to write ''Rising Sun'', a murder mystery (later made into a feature film

A feature film or feature-length film is a narrative film (motion picture or "movie") with a running time long enough to be considered the principal or sole presentation in a commercial entertainment program. The term ''feature film'' originall ...

) involving Japanese businessmen in the U.S. Likewise, in Tom Clancy

Thomas Leo Clancy Jr. (April 12, 1947 – October 1, 2013) was an American novelist. He is best known for his technically detailed espionage and military-science storylines set during and after the Cold War. Seventeen of his novels have ...

's book ''Debt of Honor

''Debt of Honor'' is a techno-thriller novel, written by Tom Clancy and released on August 17, 1994. A direct sequel to '' The Sum of All Fears'' (1991), Jack Ryan becomes the National Security Advisor when a secret cabal of Japanese industria ...

'', Clancy implies that Japan's prosperity is due primarily to unequal trading terms, and portrays Japan's business leaders acting in a power hungry cabal.

As argued by Marie Thorsten, however, Japanophobia mixed with Japanophilia during Japan's peak moments of economic dominance during the 1980s. The fear of Japan became a rallying point for "techno-nationalism", the imperative to be first in the world in mathematics, science and other quantifiable measures of national strength necessary to boost technological and economic supremacy. Notorious "Japan bashing" took place alongside the image of Japan as superhuman, mimicking in some ways the image of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

after it launched the first Sputnik satellite in 1957: both events turned the spotlight on American education. American bureaucrats purposely pushed this analogy.

In 1982, Ernest Boyer, a former U.S. Commissioner of Education, publicly declared that, "What we need is another Sputnik" to re-boot American education, and that "maybe what we should do is get the Japanese to put a Toyota into orbit". Japan was both a threat and a model for human resource development in education and the workforce, merging with the image of Asian-Americans as the "model minority". At the time, anti-Japanese sentiments were also intentionally incited by U.S. politicians as part of partisan politics of both the Democratic Party and the Republican Party, accusing each other of being "pro-Japanese" and "anti-American". In 1985, a ''The New York Times Magazine

''The New York Times Magazine'' is an American Sunday magazine supplement included with the Sunday edition of ''The New York Times''. It features articles longer than those typically in the newspaper and has attracted many notable contributors. ...

'' cover story featured Theodore H. White's ''The Danger from Japan'', which declared that the United States was "too lenient" to Japan at the end of World War II, and that if Japan continues to threaten the United States economically, then it is time "to teach them the same lesson we did after Pearl Harbor".

In 1987, the U.S. government imposed an remarkable 100% tariff on Japanese-made personal computers

A personal computer (PC) is a multi-purpose microcomputer whose size, capabilities, and price make it feasible for individual use. Personal computers are intended to be operated directly by an end user, rather than by a computer expert or tec ...

and color television exported to the United States. That same year, the Toshiba–Kongsberg scandal further deteriorated relations between Japan and the United States, as it was viewed as a violation of the Coordinating Committee for Multilateral Export Controls (CoCom), which was an embargo by the Western Bloc

The Western Bloc, also known as the Free Bloc, the Capitalist Bloc, the American Bloc, and the NATO Bloc, was a coalition of countries that were officially allied with the United States during the Cold War of 1947–1991. It was spearheaded by ...

against the Eastern Bloc during the Cold War. In response, members of the U.S. Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washin ...

urged a boycott of Toshiba, with even American politicians Helen Delich Bentley

Helen Delich Bentley (November 28, 1923 – August 6, 2016) was an American politician who was a Republican member of the United States House of Representatives from Maryland from 1985 to 1995. Before entering politics, she had been a leadi ...

and Elton Gallegly as well as other members of Congress using sledgehammers to publicly smash Toshiba products at the front of the United States Capitol

The United States Capitol, often called The Capitol or the Capitol Building, is the seat of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, which is formally known as the United States Congress. It is located on Capitol Hill ...

. By the time the 1990s rolled around, there was widespread consensus in the U.S. that their partnership with Japan would be "impossible to sustain" unless Japan is "contained".

Japan's waning economic fortunes in the 1990s, known today as the Lost Decades

The was a period of economic stagnation in Japan caused by the asset price bubble's collapse in late 1991. The term originally referred to the 1990s, but the 2000s (Lost 20 Years, 失われた20年) and the 2010s (Lost 30 Years, 失われた ...

, coupled with an upsurge in the U.S. economy as the Internet took off largely crowded anti-Japanese sentiment out of the popular media. In an ironic twist, such sentiment in America has now turned back to one of anti-Chinese sentiment

Anti-Chinese sentiment, also known as Sinophobia, is a fear or dislike of China, Chinese people or Chinese culture. It often targets Chinese minorities living outside of China and involves immigration, development of national identity i ...

again, especially after the 2010s due to its economic dominance overpowering even Japan's during the 1980s.

Asian quota

Nevertheless, there are areas that have recently proven to be an issue such as for Asians in general accessing higher education in the US. For example, in August 2020, the U.S Justice Department argued thatYale University

Yale University is a Private university, private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Sta ...

had discriminated against Asian candidates on the basis of their race, a charge the university denied.

COVID-19 pandemic

TheCOVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic, also known as the coronavirus pandemic, is an ongoing global pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The novel virus was first identi ...

, was first reported in the city of Wuhan

Wuhan (, ; ; ) is the capital of Hubei Province in the People's Republic of China. It is the largest city in Hubei and the most populous city in Central China, with a population of over eleven million, the ninth-most populous Chinese city an ...

, Hubei, China, in December 2019, and as such has led to an increase in acts and displays of prejudice

Prejudice can be an affective feeling towards a person based on their perceived group membership. The word is often used to refer to a preconceived (usually unfavourable) evaluation or classification of another person based on that person's per ...

, xenophobia

Xenophobia () is the fear or dislike of anything which is perceived as being foreign or strange. It is an expression of perceived conflict between an in-group and out-group and may manifest in suspicion by the one of the other's activities, a ...

, discrimination, violence

Violence is the use of physical force so as to injure, abuse, damage, or destroy. Other definitions are also used, such as the World Health Organization's definition of violence as "the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened ...

, and racism against people of East and Southeast Asian descent, including Japanese people as well as Americans of Japanese descent.

In 2020, Japanese jazz pianist Tadataka Unno who was based in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

was randomly attacked in a anti-Asian hate crime incident, suffering permanent injuries. The attackers had also made assumptions that he was Chinese, and had made anti-Asian profanities. After the incident, he stated that he intends to return to Japan, adding that "My wife and I worry about raising kids here n the United States especially after this happened."

See also

* Anti-Americanism#Japan * Anti-Chinese sentiment in the United States *Japan–United States relations

International relations between Japan and the United States began in the late 18th and early 19th century with the diplomatic but Unequal treaty#Japan and Korea, force-backed missions of U.S. ship captains James Glynn and Matthew C. Perry to th ...

* Japanese American Citizens League

* Nativism (politics) in the United States

*Stereotypes of East Asians in the United States

Stereotypes of East and Southeast Asians in the United States refers to ethnic stereotypes of first-generation Asian immigrants as well as Americans with ancestry from East and Southeast Asian countries that are found in American society. ...

* Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974

*'' The Coming War with Japan'', 1991 American book

*'' The Japan That Can Say No'', 1989 Japanese essay

References

Sources

* * * * * * * *Further reading

* August, Jack. "The Anti-Japanese Crusade in Arizona's Salt River Valley: 1934-35." ''Arizona and the West'' 21.2 (1979): 113-136online

* Buell, Raymond Leslie. "The development of the anti-Japanese agitation in the United States." ''Political Science Quarterly'' 37.4 (1922): 605-638

online

* Daniels, Roger. ''The politics of prejudice: The anti-Japanese movement in California and the struggle for Japanese exclusion'' (Univ of California Press, 1977). * MeGovney, Dudley O. "The anti-Japanese land laws of California and ten other states." ''California Law Review'' 35 (1947): 7+ eGovney, Dudley O. "The anti-Japanese land laws of California and ten other states." Calif. L. Rev. 35 (1947): 7. online * Okihiro, Gary. ''Cane fires: The anti-Japanese movement in Hawaii, 1865-1945'' (Temple UP, 1992). * Shim, Doobo. "From yellow peril through model minority to renewed yellow peril." ''Journal of Communication Inquiry'' 22.4 (1998): 385-409

online

* Tamura, Eileen H. "The English-only effort, the anti-Japanese campaign, and language acquisition in the education of Japanese Americans in Hawaii, 1915–40." ''History of Education Quarterly'' 33.1 (1993): 37-58. {{portalbar, Japan, United States Anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States Anti-Japanese sentiment Asian-American issues Asian-American-related controversies Japan–United States relations History of racism in the United States Japanese-American history Racially motivated violence against Asian-Americans Xenophobia White supremacy in the United States