Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Anthony Ashley Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury

PC FRS (22 July 1621 – 21 January 1683; known as Anthony Ashley Cooper from 1621 to 1630, as Sir Anthony Ashley Cooper, 2nd Baronet from 1630 to 1661, and as The Lord Ashley from 1661 to 1672) was a prominent

English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

politician during the

Interregnum

An interregnum (plural interregna or interregnums) is a period of discontinuity or "gap" in a government, organization, or social order. Archetypally, it was the period of time between the reign of one monarch and the next (coming from Latin '' ...

and the reign of King

Charles II. A founder of the

Whig party, he was also the patron of

John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism". Considered one of ...

.

Cooper was born in 1621. Having lost his parents by the age of eight, he was raised by

Edward Tooker and other guardians named in his father's will. He attended

Exeter College, Oxford

(Let Exeter Flourish)

, old_names = ''Stapeldon Hall''

, named_for = Walter de Stapledon, Bishop of Exeter

, established =

, sister_college = Emmanuel College, Cambridge

, rector = Sir Richard Trainor

...

, and

Lincoln's Inn

The Honourable Society of Lincoln's Inn is one of the four Inns of Court in London to which barristers of England and Wales belong and where they are called to the Bar. (The other three are Middle Temple, Inner Temple and Gray's Inn.) Lincol ...

. He married the daughter of

Thomas Coventry, 1st Baron Coventry in 1639; that patronage secured his first seat in the

Short Parliament

The Short Parliament was a Parliament of England that was summoned by King Charles I of England on the 20th of February 1640 and sat from 13th of April to the 5th of May 1640. It was so called because of its short life of only three weeks.

Af ...

. He soon lost a disputed election to the

Long Parliament

The Long Parliament was an English Parliament which lasted from 1640 until 1660. It followed the fiasco of the Short Parliament, which had convened for only three weeks during the spring of 1640 after an 11-year parliamentary absence. In Septe ...

. During the

English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I (" Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of r ...

s he fought as a

Royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of gov ...

; then as a

Parliamentarian from 1644. During the

English Interregnum

The Interregnum was the period between the execution of Charles I on 30 January 1649 and the arrival of his son Charles II in London on 29 May 1660 which marked the start of the Restoration. During the Interregnum, England was under various for ...

, he served on the

English Council of State

The English Council of State, later also known as the Protector's Privy Council, was first appointed by the Rump Parliament on 14 February 1649 after the execution of King Charles I.

Charles' execution on 30 January was delayed for several hour ...

under

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three ...

, although he opposed Cromwell's attempt to rule without Parliament during the

Rule of the Major-Generals

The Rule of the Major-Generals, was a period of direct military government from August 1655 to January 1657, during Oliver Cromwell's Protectorate. England and Wales were divided into ten regions, each governed by a major-general who answered to th ...

. He also opposed the religious extremism of the

Fifth Monarchists during

Barebone's Parliament

Barebone's Parliament, also known as the Little Parliament, the Nominated Assembly and the Parliament of Saints, came into being on 4 July 1653, and was the last attempt of the English Commonwealth to find a stable political form before the inst ...

.

Later as a member and patron he opposed the

New Model Army

The New Model Army was a standing army formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians during the First English Civil War, then disbanded after the Stuart Restoration in 1660. It differed from other armies employed in the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Th ...

's attempts to rule after

Richard Cromwell

Richard Cromwell (4 October 162612 July 1712) was an English statesman who was the second and last Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland and son of the first Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell.

On his father's deat ...

's ousting; encouraged Sir

George Monck

George Monck, 1st Duke of Albemarle JP KG PC (6 December 1608 – 3 January 1670) was an English soldier, who fought on both sides during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. A prominent military figure under the Commonwealth, his support was cruc ...

's march on London, a pivotal march in restoring the monarchy; sat in the

Convention Parliament of 1660 which agreed to

restore the English monarchy; and travelled as a member of its twelve-strong delegation to the

Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands ( Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiograph ...

to invite King

Charles II to return. Charles, shortly before his coronation, created Cooper Lord Ashley; thus, when the

Cavalier Parliament

The Cavalier Parliament of England lasted from 8 May 1661 until 24 January 1679. It was the longest English Parliament, and longer than any Great British or UK Parliament to date, enduring for nearly 18 years of the quarter-century reign of C ...

assembled in 1661 the new peer moved from the

House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

to the

House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminst ...

. He served as

Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the Exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and head of HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, the Ch ...

, 1661–1672. During the ministry of the

Earl of Clarendon, he opposed the

Clarendon Code, preferring Charles II's Declaration of Indulgence (1662), which the King was forced to relinquish. After the fall of Clarendon, he was one of the five among the later-criticised, acronym-based,

Cabal Ministry or 'the cabal', serving as

Lord Chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. Th ...

in 1672–1673; he was created

Earl of Shaftesbury

Earl of Shaftesbury is a title in the Peerage of England. It was created in 1672 for Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 1st Baron Ashley, a prominent politician in the Cabal then dominating the policies of King Charles II. He had already succeeded his fa ...

in 1672. During this period,

John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism". Considered one of ...

entered his household. Ashley took an interest in colonial ventures and was one of the Lords Proprietor of the

Province of Carolina

Province of Carolina was a province of England (1663–1707) and Great Britain (1707–1712) that existed in North America and the Caribbean from 1663 until partitioned into North and South on January 24, 1712. It is part of present-day Alabam ...

. In 1669, Ashley and Locke collaborated in writing the

Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina

The ''Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina'' were adopted on March 1, 1669 by the eight Lords Proprietors of the Province of Carolina, which included most of the land between what is now Virginia and Florida. It replaced the '' Charter of Caro ...

. By 1673, Ashley was worried that the heir to the throne,

James, Duke of York

James VII and II (14 October 1633 16 September 1701) was King of England and King of Ireland as James II, and King of Scotland as James VII from the death of his elder brother, Charles II, on 6 February 1685. He was deposed in the Glorious ...

, was secretly a

Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

.

Shaftesbury became a leading opponent of the policies of

Thomas Osborne, Earl of Danby who favoured strict interpretation of

penal laws and compulsory

Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of t ...

adherence. Shaftesbury, who sympathized with Protestant

Nonconformists, briefly agreed to work with the possible heir to the throne, the Duke of York (James), who opposed enforcing the penal laws against Roman Catholic

recusants

Recusancy (from la, recusare, translation=to refuse) was the state of those who remained loyal to the Catholic Church and refused to attend Church of England services after the English Reformation.

The 1558 Recusancy Acts passed in the reign ...

. By 1675, however, Shaftesbury was convinced that Danby, assisted by high church bishops, was determined to revert England to an

absolute monarchy

Absolute monarchy (or Absolutism as a doctrine) is a form of monarchy in which the monarch rules in their own right or power. In an absolute monarchy, the king or queen is by no means limited and has absolute power, though a limited constituti ...

. He soon came to see the Duke of York's religion as linked to this aspiration. Opposed to the growth of "popery and arbitrary government" throughout the period 1675–1680, Shaftesbury argued in favour of frequent parliaments (spending time in the

Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is sep ...

in 1677–1678 for espousing this view) and argued that the nation needed protection from a potential Roman Catholic successor; thus during the

Exclusion Crisis

The Exclusion Crisis ran from 1679 until 1681 in the reign of King Charles II of England, Scotland and Ireland. Three Exclusion bills sought to exclude the King's brother and heir presumptive, James, Duke of York, from the thrones of England, Sco ...

he was an outspoken supporter of the

Exclusion Bill

The Exclusion Crisis ran from 1679 until 1681 in the reign of King Charles II of England, Scotland and Ireland. Three Exclusion bills sought to exclude the King's brother and heir presumptive, James, Duke of York, from the thrones of England, Sco ...

. He combined this with supporting Charles II's remarrying a Protestant princess to produce a legitimate Protestant heir, or legitimizing his illegitimate Protestant son the

Duke of Monmouth. The

Whig party was born during this crisis, and Shaftesbury was one of the party's most prominent leaders.

In 1681, during the

Tory

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. The ...

reaction following the failure of the Exclusion Bill, Shaftesbury was arrested for

high treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

, a prosecution dropped several months later. In 1682, after the Tories had gained the power to pack London

juries

A jury is a sworn body of people (jurors) convened to hear evidence and render an impartial verdict (a finding of fact on a question) officially submitted to them by a court, or to set a penalty or judgment.

Juries developed in England duri ...

with their supporters,

Shaftesbury, fearing re-arrest and trial, fled abroad, arrived in

Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Amstel'') is the capital and most populous city of the Netherlands, with The Hague being the seat of government. It has a population of 907,976 within the city proper, 1,558,755 in the urban ar ...

, fell ill and soon died, in January 1683.

Biography

Early life and first marriage, 1621–1640

Cooper was the eldest son and successor of

Sir John Cooper, 1st Baronet

Sir John Cooper, 1st Baronet (died 23 March 1630), was an English landowner and politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1628 to 1629. He was the father of Anthony Ashley Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury.

Life

Cooper was the son of Sir ...

, of

Rockbourne in Hampshire, and his mother was the former Anne Ashley, daughter and sole heiress of

Sir Anthony Ashley, 1st Baronet. He was born on 22 July 1621, at the home of his maternal grandfather Sir Anthony Ashley in

Wimborne St Giles

Wimborne St Giles is a village and civil parish in east Dorset, England, on Cranborne Chase, seven miles north of Wimborne Minster and 12 miles north of Poole. The village lies within the Shaftesbury estate, owned by the Earl of Shaftesbury. A tr ...

, Dorset.

[Tim Harris. "Cooper, Anthony Ashley", in the '']Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

''. Oxford University Press, 2004–2007. He was named Anthony Ashley Cooper because of a promise the couple had made to Sir Anthony.

Although Sir Anthony Ashley was of minor gentry stock, he had served as

Secretary at War

The Secretary at War was a political position in the English and later British government, with some responsibility over the administration and organization of the Army, but not over military policy. The Secretary at War ran the War Office. Afte ...

in the reign of Queen

Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

, and in 1622, two years after the death of his first wife, Sir Anthony Ashley married the 19-year-old Philippa Sheldon (51 years his junior), a relative of

George Villiers, Marquess of Buckingham, thus cementing relations with the most powerful man at court.

Cooper's father was created a

baronet

A baronet ( or ; abbreviated Bart or Bt) or the female equivalent, a baronetess (, , or ; abbreviation Btss), is the holder of a baronetcy, a hereditary title awarded by the British Crown. The title of baronet is mentioned as early as the 14t ...

in 1622, and he represented

Poole

Poole () is a large coastal town and seaport in Dorset, on the south coast of England. The town is east of Dorchester and adjoins Bournemouth to the east. Since 1 April 2019, the local authority is Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole Counc ...

in the parliaments of 1625 and 1628, supporting the attack on

Richard Neile

Richard Neile (or Neale; 1562 – 31 October 1640) was an English churchman, bishop successively of six English dioceses, more than any other man, including the Archdiocese of York from 1631 until his death. He was involved in the last burnin ...

,

Bishop of Winchester

The Bishop of Winchester is the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Winchester in the Church of England. The bishop's seat (''cathedra'') is at Winchester Cathedral in Hampshire. The Bishop of Winchester has always held ''ex officio'' (except ...

for his

Arminian

Arminianism is a branch of Protestantism based on the theological ideas of the Dutch Reformed theologian Jacobus Arminius (1560–1609) and his historic supporters known as Remonstrants. Dutch Arminianism was originally articulated in the '' ...

tendencies.

Sir Anthony Ashley insisted that a man with

Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. ...

leanings, Aaron Guerdon, be chosen as Cooper's first tutor.

Cooper's mother died in 1628. In the following year his father remarried, this time to the widowed Mary Moryson, one of the daughters of wealthy London textile merchant

Baptist Hicks

Baptist Hicks, 1st Viscount Campden (1551 – 18 October 1629) was an English cloth merchant and politician who sat in the House of Commons between 1621 and 1628. King James I knighted Hicks in 1603 and in 1620 he was created a baronet.

He w ...

and co-

heir

Inheritance is the practice of receiving private property, titles, debts, entitlements, privileges, rights, and obligations upon the death of an individual. The rules of inheritance differ among societies and have changed over time. Offic ...

of his fortune.

Through his stepmother, Cooper thus gained an important political connection in the form of her grandson, the future

1st Earl of Essex. Cooper's father died in 1630, leaving him a wealthy

orphan

An orphan (from the el, ορφανός, orphanós) is a child whose parents have died.

In common usage, only a child who has lost both parents due to death is called an orphan. When referring to animals, only the mother's condition is usuall ...

.

Upon his father's death, he inherited his father's

baronetcy

A baronet ( or ; abbreviated Bart or Bt) or the female equivalent, a baronetess (, , or ; abbreviation Btss), is the holder of a baronetcy, a hereditary title awarded by the British Crown. The title of baronet is mentioned as early as the 14th ...

and was now Sir Anthony Ashley Cooper.

Cooper's father had held his lands in

knight-service

Knight-service was a form of feudal land tenure under which a knight held a fief or estate of land termed a knight's fee (''fee'' being synonymous with ''fief'') from an overlord conditional on him as tenant performing military service for his ov ...

, so Cooper's inheritance now came under the authority of the

Court of Wards.

The

trustees

Trustee (or the holding of a trusteeship) is a legal term which, in its broadest sense, is a synonym for anyone in a position of trust and so can refer to any individual who holds property, authority, or a position of trust or responsibility to t ...

whom his father had appointed to administer his estate, his brother-in-law (Anthony Ashley Cooper's uncle by marriage) Edward Tooker and his colleague from the House of Commons, Sir Daniel Norton, purchased Cooper's wardship from the king, but they remained unable to sell Cooper's land without permission of the Court of Wards because, on his death, Sir John Cooper had left some £35,000 in gambling debts.

The Court of Wards ordered the sale of the best of Sir John's lands to pay his debts, with several sales commissioners picking up choice properties at £20,000 less than their market value, a circumstance which led Cooper to hate the Court of Wards as a corrupt institution.

Cooper was sent to live with his father's trustee

Sir Daniel Norton in

Southwick, Hampshire

Southwick is a village in Hampshire, England. north of the Portsmouth boundary measured from Portsea Island. Homes and farms in the village are influenced by the style of the Middle Ages apart from Church Lodge.

History

Southwick was in ...

(near

Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most d ...

). Norton had joined in Sir John Cooper's denunciation of Arminianism in the 1628–29 parliament, and Norton chose a man with

Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become more Protestant. ...

leanings named Fletcher as Cooper's tutor.

Sir Daniel died in 1636, and Cooper was sent to live with his father's other trustee,

Edward Tooker, at

Maddington, near Salisbury. Here his tutor was a man with an MA from

Oriel College, Oxford

Oriel College () is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in Oxford, England. Located in Oriel Square, the college has the distinction of being the oldest royal foundation in Oxford (a title formerly claimed by University College, ...

.

Cooper matriculated at

Exeter College, Oxford

(Let Exeter Flourish)

, old_names = ''Stapeldon Hall''

, named_for = Walter de Stapledon, Bishop of Exeter

, established =

, sister_college = Emmanuel College, Cambridge

, rector = Sir Richard Trainor

...

, on 24 March 1637, aged 15, where he studied under its master, the

Regius Professor of Divinity,

John Prideaux, a

Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John C ...

with vehemently anti-Arminian tendencies.

While there he fomented a minor riot and left without taking a degree. In February 1638, Cooper was admitted to

Lincoln's Inn

The Honourable Society of Lincoln's Inn is one of the four Inns of Court in London to which barristers of England and Wales belong and where they are called to the Bar. (The other three are Middle Temple, Inner Temple and Gray's Inn.) Lincol ...

,

[ where he was exposed to the Puritan preaching of chaplains ]Edward Reynolds

Edward Reynolds (November 1599 – 28 July 1676) was a bishop of Norwich in the Church of England and an author.Cyclopaedia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature. Prepared by the Rev. John M'Clintock, D.D., and James Strong, ...

and Joseph Caryl

Joseph Caryl (November 1602 – 25 February 1673) was an English ejected minister.

Life

He was born in London, educated at Merchant Taylors' School, and graduated at Exeter College, Oxford, and became preacher at Lincoln's Inn. He frequently p ...

.Lord Keeper of the Great Seal

The Lord Keeper of the Great Seal of England, and later of Great Britain, was formerly an officer of the English Crown charged with physical custody of the Great Seal of England. This position evolved into that of one of the Great Officers of S ...

for Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

.Canonbury

Canonbury is a residential area of Islington in the London Borough of Islington, North London. It is roughly in the area between Essex Road, Upper Street and Cross Street and either side of St Paul's Road.

In 1253 land in the area was granted to ...

in Islington

Islington () is a district in the north of Greater London, England, and part of the London Borough of Islington. It is a mainly residential district of Inner London, extending from Islington's High Street to Highbury Fields, encompassing the ...

.

Early political career, 1640–1660

Parliament, 1640–1642

In March 1640, while still a minor, Cooper was elected Member of Parliament for the borough of

In March 1640, while still a minor, Cooper was elected Member of Parliament for the borough of Tewkesbury

Tewkesbury ( ) is a medieval market town and civil parish in the north of Gloucestershire, England. The town has significant history in the Wars of the Roses and grew since the building of Tewkesbury Abbey. It stands at the confluence of the Ri ...

, Gloucestershire, in the Short Parliament

The Short Parliament was a Parliament of England that was summoned by King Charles I of England on the 20th of February 1640 and sat from 13th of April to the 5th of May 1640. It was so called because of its short life of only three weeks.

Af ...

[History of Parliament Online – Cooper, Sir Anthony Ashley]

/ref> through the influence of Lord Coventry.Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

's Lord Keeper

The Lord Keeper of the Great Seal of England, and later of Great Britain, was formerly an officer of the English Crown charged with physical custody of the Great Seal of England. This position evolved into that of one of the Great Officers of ...

, Coventry

Coventry ( or ) is a city in the West Midlands, England. It is on the River Sherbourne. Coventry has been a large settlement for centuries, although it was not founded and given its city status until the Middle Ages. The city is governed b ...

, would be too sympathetic to the king.

Royalist, 1642–1644

When the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

began in 1642, Cooper initially supported the King (somewhat echoing Holles' concerns). After a period of vacillating, in summer 1643, at his own expense, he raised a regiment of foot

The foot ( : feet) is an anatomical structure found in many vertebrates. It is the terminal portion of a limb which bears weight and allows locomotion. In many animals with feet, the foot is a separate organ at the terminal part of the leg mad ...

and a troop

A troop is a military sub-subunit, originally a small formation of cavalry, subordinate to a squadron. In many armies a troop is the equivalent element to the infantry section or platoon. Exceptions are the US Cavalry and the King's Tr ...

of horse

The horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') is a domesticated, one-toed, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two extant subspecies of ''Equus ferus''. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 million yea ...

for the King, serving as their colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge ...

and captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

respectively.Royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of gov ...

victory at the Battle of Roundway Down on 13 July 1643, Cooper was one of three commissioners appointed to negotiate the surrender of Dorchester, at which he negotiated a deal whereby the town agreed to surrender in exchange for being spared plunder and punishment. However, troops under Prince Maurice

Maurice, Prince Palatine of the Rhine KG (16 January 1621, in Küstrin Castle, Brandenburg – September 1652, near the Virgin Islands), was the fourth son of Frederick V, Elector Palatine and Princess Elizabeth, only daughter of King James VI ...

soon arrived and plundered Dorchester and Weymouth anyway, leading to heated words between Cooper and Prince Maurice. William Seymour, Marquess of Hertford, the commander of the Royalist forces in the west, had recommended Cooper be appointed governor of

William Seymour, Marquess of Hertford, the commander of the Royalist forces in the west, had recommended Cooper be appointed governor of Weymouth and Portland

Weymouth and Portland was a local government district and borough in Dorset, England. It consisted of the resort of Weymouth and the Isle of Portland, and includes the areas of Wyke Regis, Preston, Melcombe Regis, Upwey, Broadwey, Southi ...

, but Prince Maurice intervened to block the appointment, on grounds of Cooper's youth and alleged inexperience.Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the Exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and head of HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, the Ch ...

, Edward Hyde; Hyde arranged a compromise whereby Cooper would be appointed as governor but resign as soon as it was possible to do so without losing face.High Sheriff of Dorset

The High Sheriff of Dorset is an ancient high sheriff title which has been in existence for over one thousand years. Until 1567 the Sheriff of Somerset was also the Sheriff of Dorset.

On 1 April 1974, under the provisions of the Local Government ...

and president of the council of war

A council of war is a term in military science that describes a meeting held to decide on a course of action, usually in the midst of a battle. Under normal circumstances, decisions are made by a commanding officer, optionally communicated ...

for Dorset, both of which were offices more prestigious than the governorship. Cooper spent the remainder of 1643 as governor of Weymouth and Portland.

Parliamentarian and second marriage, 1644–1652

In early 1644, Cooper resigned all of his posts under the king, and travelled to Hurst Castle

Hurst Castle is an artillery fort established by Henry VIII on the Hurst Spit in Hampshire, England, between 1541 and 1544. It formed part of the king's Device Forts coastal protection programme against invasion from France and the Holy Rom ...

, the headquarters of the Parliamentarians.Committee of Both Kingdoms

The Committee of Both Kingdoms, (known as the Derby House Committee from late 1647), was a committee set up during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms by the Parliamentarian faction in association with representatives from the Scottish Covenanters, aft ...

, on 6 March 1644, he explained that he believed that Charles I was now being influenced by Roman Catholic influences (Catholics were increasingly prominent at Charles' court, and he had recently signed a truce with Irish Catholic

Irish Catholics are an ethnoreligious group native to Ireland whose members are both Catholic and Irish. They have a large diaspora, which includes over 36 million American citizens and over 14 million British citizens (a quarter of the Briti ...

rebels) and that he believed Charles had no intention of "promoting or preserving ... the Protestant religion and the liberties of the kingdom" and that he, therefore, believed the parliamentary cause was just, and he offered to take the Solemn League and Covenant

The Solemn League and Covenant was an agreement between the Scottish Covenanters and the leaders of the English Parliamentarians in 1643 during the First English Civil War, a theatre of conflict in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. On 17 August 1 ...

.House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

gave Cooper permission to leave London, and he soon joined parliamentary forces in Dorset.Self-denying Ordinance

The Self-denying Ordinance was passed by the English Parliament on 3 April 1645. All members of the House of Commons or Lords who were also officers in the Parliamentary army or navy were required to resign one or the other, within 40 days fr ...

, Cooper chose to resign his commissions in the parliamentary army (which was, at any rate, being supplanted by the creation of the New Model Army

The New Model Army was a standing army formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians during the First English Civil War, then disbanded after the Stuart Restoration in 1660. It differed from other armies employed in the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Th ...

) to preserve his claim to be the rightful member for Downton.plantation

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. Th ...

s, investing in a plantation in the English colony

The English overseas possessions, also known as the English colonial empire, comprised a variety of overseas territories that were colonised, conquered, or otherwise acquired by the former Kingdom of England during the centuries before the Ac ...

of Barbados

Barbados is an island country in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the Caribbean region of the Americas, and the most easterly of the Caribbean Islands. It occupies an area of and has a population of about 287,000 (2019 estima ...

in 1646.Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their n ...

s against the Independents, and, as such, opposed the regicide of Charles I.justice of the peace

A justice of the peace (JP) is a judicial officer of a lower or '' puisne'' court, elected or appointed by means of a commission ( letters patent) to keep the peace. In past centuries the term commissioner of the peace was often used with the s ...

for Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated Wilts) is a historic and ceremonial county in South West England with an area of . It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset to the southwest, Somerset to the west, Hampshire to the southeast, Gloucestershire ...

and Dorset

Dorset ( ; archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a county in South West England on the English Channel coast. The ceremonial county comprises the unitary authority areas of Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole and Dorset. Covering an area of , ...

in February 1649 and acting as High Sheriff of Wiltshire

This is a list of the Sheriffs and (after 1 April 1974) High Sheriffs of Wiltshire.

Until the 14th century, the shrievalty was held ''ex officio'' by the castellans of Old Sarum Castle.

On 1 April 1974, under the provisions of the Local Go ...

for 1647.David Cecil, 3rd Earl of Exeter

David Cecil, 3rd Earl of Exeter (c. 1600–1643) was an English peer and member of the House of Lords.

Life

David Cecil was the son of Sir Richard Cecil of Wakerley, Northamptonshire. He was educated at Clare College, Cambridge, and admitted at ...

.Anthony

Anthony or Antony is a masculine given name, derived from the '' Antonii'', a ''gens'' ( Roman family name) to which Mark Antony (''Marcus Antonius'') belonged. According to Plutarch, the Antonii gens were Heracleidae, being descendants of Anton, ...

, lived to adulthood.

Statesman under the Commonwealth of England and the Protectorate, 1652–1660

On 17 January 1652, the Rump Parliament

The Rump Parliament was the English Parliament after Colonel Thomas Pride commanded soldiers to purge the Long Parliament, on 6 December 1648, of those members hostile to the Grandees' intention to try King Charles I for high treason.

"R ...

appointed Cooper to the committee on law reform chaired by Sir Matthew Hale

Sir Matthew Hale (1 November 1609 – 25 December 1676) was an influential English barrister, judge and jurist most noted for his treatise '' Historia Placitorum Coronæ'', or ''The History of the Pleas of the Crown''.

Born to a barrister an ...

(the so-called Hale Commission, none of whose moderate proposals were ever enacted).pardon

A pardon is a government decision to allow a person to be relieved of some or all of the legal consequences resulting from a criminal conviction. A pardon may be granted before or after conviction for the crime, depending on the laws of the j ...

for his time as a Royalist, opening the way for his return to public office. Following the dissolution of the Rump in April 1653, Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three ...

and the Army Council nominated Cooper to serve in Barebone's Parliament

Barebone's Parliament, also known as the Little Parliament, the Nominated Assembly and the Parliament of Saints, came into being on 4 July 1653, and was the last attempt of the English Commonwealth to find a stable political form before the inst ...

as member for Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated Wilts) is a historic and ceremonial county in South West England with an area of . It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset to the southwest, Somerset to the west, Hampshire to the southeast, Gloucestershire ...

.[ On 14 July, Cromwell appointed Cooper to the ]English Council of State

The English Council of State, later also known as the Protector's Privy Council, was first appointed by the Rump Parliament on 14 February 1649 after the execution of King Charles I.

Charles' execution on 30 January was delayed for several hour ...

, where he was a member of the Committee for the Business of the Law, which was intended to continue the reform work of the Hale Commission.tithes

A tithe (; from Old English: ''teogoþa'' "tenth") is a one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government. Today, tithes are normally voluntary and paid in cash or cheques or more ...

.First Protectorate Parliament

The First Protectorate Parliament was summoned by the Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell under the terms of the Instrument of Government. It sat for one term from 3 September 1654 until 22 January 1655 with William Lenthall as the Speaker of the Ho ...

in summer 1654, Cooper headed a slate of ten candidates who stood in Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated Wilts) is a historic and ceremonial county in South West England with an area of . It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset to the southwest, Somerset to the west, Hampshire to the southeast, Gloucestershire ...

against 10 republican MPs headed by Edmund Ludlow

Edmund Ludlow (c. 1617–1692) was an English parliamentarian, best known for his involvement in the execution of Charles I, and for his ''Memoirs'', which were published posthumously in a rewritten form and which have become a major source ...

.Stonehenge

Stonehenge is a prehistoric monument on Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire, England, west of Amesbury. It consists of an outer ring of vertical sarsen standing stones, each around high, wide, and weighing around 25 tons, topped by connec ...

.Tewkesbury

Tewkesbury ( ) is a medieval market town and civil parish in the north of Gloucestershire, England. The town has significant history in the Wars of the Roses and grew since the building of Tewkesbury Abbey. It stands at the confluence of the Ri ...

and Poole

Poole () is a large coastal town and seaport in Dorset, on the south coast of England. The town is east of Dorchester and adjoins Bournemouth to the east. Since 1 April 2019, the local authority is Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole Counc ...

[ but chose to sit for Wiltshire. Although Cooper was generally supportive of Cromwell during the First Protectorate Parliament (he voted in favour of making Cromwell king in December 1654), he grew worried that Cromwell was growing inclined to rule through the Army rather than through Parliament.]Henry Spencer, 1st Earl of Sunderland

Henry Spencer, 1st Earl of Sunderland, 3rd Baron Spencer of Wormleighton (c. 23 November 1620 – 20 September 1643), known as The Lord Spencer between 1636 and June 1643, was an English peer, nobleman, and politician from the Spencer family who ...

.Second Protectorate Parliament

The Second Protectorate Parliament in England sat for two sessions from 17 September 1656 until 4 February 1658, with Thomas Widdrington as the Speaker of the House of Commons. In its first session, the House of Commons was its only chamber; in ...

,[ although when the parliament met on 17 September 1656, Cooper was one of 100 members whom the Council of State excluded from the parliament.]Sir George Booth

George Booth, 1st Baron Delamer (18 December 16228 August 1684), was an English landowner and politician from Cheshire, who served as an MP from 1646 to 1661, when he was elevated to the House of Lords as Baron Delamer.

A member of the moder ...

.Humble Petition and Advice

The Humble Petition and Advice was the second and last codified constitution of England after the Instrument of Government.

On 23 February 1657, during a sitting of the Second Protectorate Parliament, Sir Christopher Packe, a Member of Parliam ...

that stipulated that the excluded members could return to parliament. Upon his return to the house, Cooper spoke out against Cromwell's Other House. Cooper was elected to the

Cooper was elected to the Third Protectorate Parliament

The Third Protectorate Parliament sat for one session, from 27 January 1659 until 22 April 1659, with Chaloner Chute and Thomas Bampfylde as the Speakers of the House of Commons. It was a bicameral Parliament, with an Upper House having a pow ...

in early 1659 as member for Wiltshire.[ During the debates in this parliament, Cooper sided with the republicans who opposed the Humble Petition and Advice and insisted that the bill recognising ]Richard Cromwell

Richard Cromwell (4 October 162612 July 1712) was an English statesman who was the second and last Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland and son of the first Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell.

On his father's deat ...

as Protector should limit his control over the militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

and eliminate the protector's ability to veto legislation.House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminst ...

.Sir George Booth

George Booth, 1st Baron Delamer (18 December 16228 August 1684), was an English landowner and politician from Cheshire, who served as an MP from 1646 to 1661, when he was elevated to the House of Lords as Baron Delamer.

A member of the moder ...

's Presbyterian royalist uprising in Cheshire

Cheshire ( ) is a ceremonial and historic county in North West England, bordered by Wales to the west, Merseyside and Greater Manchester to the north, Derbyshire to the east, and Staffordshire and Shropshire to the south. Cheshire's county tow ...

, but in September the Council found him not guilty of any involvement.New Model Army

The New Model Army was a standing army formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians during the First English Civil War, then disbanded after the Stuart Restoration in 1660. It differed from other armies employed in the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Th ...

dissolved the Rump Parliament and replaced the Council of State with its own Committee of Safety.Henry Neville Henry Neville or Nevile may refer to:

* Henry Neville (died c.1415), MP for leicestershire

* Henry Neville, 5th Earl of Westmorland (1525–1564), English peer

*Henry Neville (Gentleman of the Privy Chamber) (c. 1520–1593)

*Henry Neville (died 1 ...

and six other members of the Council of State continued to meet in secret, referring to themselves as the rightful Council of State. Upon General Monck's march into London, Monck was displeased that the Rump Parliament was not prepared to confirm him as commander-in-chief of the army.

Upon General Monck's march into London, Monck was displeased that the Rump Parliament was not prepared to confirm him as commander-in-chief of the army.Pride's Purge

Pride's Purge is the name commonly given to an event that took place on 6 December 1648, when soldiers prevented members of Parliament considered hostile to the New Model Army from entering the House of Commons of England.

Despite defeat in the ...

, and Monck obliged on 21 February 1660.[

Beginning in spring 1660, Cooper drew closer to the royalist cause. As late as mid-April, he appears to have favoured only a conditional restoration. In April 1660 he was re-elected MP for Wiltshire in the Convention Parliament.][ On 25 April he voted in favour of an unconditional restoration.]The Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a city and municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's administrative centre and its seat of government, and while the official capital o ...

to invite Charles II to return to England.

Restoration politician, 1660–1683

Cooper returned to England with Charles in late May.Thomas Wriothesley, 4th Earl of Southampton

Thomas Wriothesley, 4th Earl of Southampton, KG ( ; 10 March 1607 – 16 May 1667), styled Lord Wriothesley before 1624, was an English statesman, a staunch supporter of King Charles II who after the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660 r ...

, Charles appointed Cooper to his privy council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mo ...

on 27 May 1660.Declaration of Breda

The Declaration of Breda (dated 4 April 1660) was a proclamation by Charles II of England in which he promised a general pardon for crimes committed during the English Civil War and the Interregnum for all those who recognized Charles as the la ...

and was formally pardoned for his support of the English Commonwealth on 27 June 1660.execution

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that ...

should be exempt from the general pardon.English Interregnum

The Interregnum was the period between the execution of Charles I on 30 January 1649 and the arrival of his son Charles II in London on 29 May 1660 which marked the start of the Restoration. During the Interregnum, England was under various for ...

, including Hugh Peters

Hugh Peter (or Peters) (baptized 29 June 1598 – 16 October 1660) was an English preacher, political advisor and soldier who supported the Parliamentary cause during the English Civil War, and became highly influential. He employed a flamboyant ...

, Thomas Harrison, and Thomas Scot

Thomas Scot (or Scott; died 17 October 1660) was an English politician who sat in the House of Commons at various times between 1645 and 1660. He was executed as one of the regicides of King Charles I.

Early life

Scot was educated at Westmi ...

.excise

file:Lincoln Beer Stamp 1871.JPG, upright=1.2, 1871 U.S. Revenue stamp for 1/6 barrel of beer. Brewers would receive the stamp sheets, cut them into individual stamps, cancel them, and paste them over the Bunghole, bung of the beer barrel so when ...

imposed by the Long Parliament to compensate the crown for the loss of revenues associated with the abolition of the court. On 20 April 1661, three days before his

On 20 April 1661, three days before his coronation

A coronation is the act of placement or bestowal of a crown upon a monarch's head. The term also generally refers not only to the physical crowning but to the whole ceremony wherein the act of crowning occurs, along with the presentation of o ...

at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

, Charles II announced his coronation honours, and in those honours, he created Cooper Baron Ashley, of Wimborne St Giles.

Chancellor of the Exchequer, 1661–1672

Following the coronation, the Cavalier Parliament

The Cavalier Parliament of England lasted from 8 May 1661 until 24 January 1679. It was the longest English Parliament, and longer than any Great British or UK Parliament to date, enduring for nearly 18 years of the quarter-century reign of C ...

met beginning on 8 May 1661. Lord Ashley took his seat in the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminst ...

on 11 May.Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the Exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and head of HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, the Ch ...

and under-treasurer (Southampton, Ashley's uncle by marriage, was at the time Lord High Treasurer

The post of Lord High Treasurer or Lord Treasurer was an English government position and has been a British government position since the Acts of Union of 1707. A holder of the post would be the third-highest-ranked Great Officer of State ...

).Catherine of Braganza

Catherine of Braganza ( pt, Catarina de Bragança; 25 November 1638 – 31 December 1705) was Queen of England, Scotland and Ireland during her marriage to King Charles II, which lasted from 21 May 1662 until his death on 6 February 1685. She ...

because the marriage would involve supporting the Portuguese, and Portugal's ally France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, in Portugal's struggle against Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

.Lord Chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. Th ...

, the Earl of Clarendon, thus beginning what would prove to be a long-running political rivalry with Clarendon.Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

dissenters.Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon

Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon (18 February 16099 December 1674), was an English statesman, lawyer, diplomat and historian who served as chief advisor to Charles I during the First English Civil War, and Lord Chancellor to Charles II fr ...

, Charles' Lord Chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. Th ...

, for opposing the royal prerogative

The royal prerogative is a body of customary authority, privilege and immunity, recognized in common law and, sometimes, in civil law jurisdictions possessing a monarchy, as belonging to the sovereign and which have become widely vested in th ...

to dispense with laws. Clarendon remarked that in his opinion, the declaration was " Ship-Money in religion". In May 1663, Ashley was one of eight Lords Proprietors (Lord Clarendon was one of the others) given title to a huge tract of land in North America, which eventually became the

In May 1663, Ashley was one of eight Lords Proprietors (Lord Clarendon was one of the others) given title to a huge tract of land in North America, which eventually became the Province of Carolina

Province of Carolina was a province of England (1663–1707) and Great Britain (1707–1712) that existed in North America and the Caribbean from 1663 until partitioned into North and South on January 24, 1712. It is part of present-day Alabam ...

, named in honour of King Charles.John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism". Considered one of ...

drafted a plan for the colony known as the Grand Model, which included the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina

The ''Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina'' were adopted on March 1, 1669 by the eight Lords Proprietors of the Province of Carolina, which included most of the land between what is now Virginia and Florida. It replaced the '' Charter of Caro ...

and a framework for settlement and development.

By early 1664, Ashley was a member of the circle of John Maitland, 1st Duke of Lauderdale

John Maitland, 1st Duke and 2nd Earl of Lauderdale, 3rd Lord Maitland of Thirlestane KG PC (24 May 1616, Lethington, East Lothian – 24 August 1682), was a Scottish politician, and leader within the Cabal Ministry.

Background

Maitl ...

, who ranged themselves in opposition to Lord Clarendon.

During the debate on the Conventicle Bill in May 1664, Ashley proposed mitigating the harshness of the penalties initially suggested by the House of Commons.illegitimate

Legitimacy, in traditional Western common law, is the status of a child born to parents who are legally married to each other, and of a child conceived before the parents obtain a legal divorce. Conversely, ''illegitimacy'', also known as '' ...

son James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth

James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth, 1st Duke of Buccleuch, KG, PC (9 April 1649 – 15 July 1685) was a Dutch-born English nobleman and military officer. Originally called James Crofts or James Fitzroy, he was born in Rotterdam in the Netherlan ...

.Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against Fr ...

squadron seized the Dutch colony of New Netherland

New Netherland ( nl, Nieuw Nederland; la, Novum Belgium or ) was a 17th-century colonial province of the Dutch Republic that was located on the east coast of what is now the United States. The claimed territories extended from the Delmarva ...

.the Duke of Buckingham

Duke of Buckingham held with Duke of Chandos, referring to Buckingham, is a title that has been created several times in the peerages of England, Great Britain, and the United Kingdom. There have also been earls and marquesses of Buckingham ...

, which sought to prevent the importation of Irish cattle into England.Lord Lieutenant of Ireland

Lord Lieutenant of Ireland (), or more formally Lieutenant General and General Governor of Ireland, was the title of the chief governor of Ireland from the Williamite Wars of 1690 until the Partition of Ireland in 1922. This spanned the King ...

, James Butler, 1st Duke of Ormonde

Lieutenant-General James FitzThomas Butler, 1st Duke of Ormond, KG, PC (19 October 1610 – 21 July 1688), was a statesman and soldier, known as Earl of Ormond from 1634 to 1642 and Marquess of Ormond from 1642 to 1661. Following the failur ...

. He suggested that Irish peers such as Ormonde should have no precedence over English commoners. In October 1666, Ashley met

In October 1666, Ashley met John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism". Considered one of ...

, who would in time become his personal secretary.liver

The liver is a major organ only found in vertebrates which performs many essential biological functions such as detoxification of the organism, and the synthesis of proteins and biochemicals necessary for digestion and growth. In humans, it i ...

infection. There he was impressed with Locke, and persuaded him to become part of his retinue. Locke had been looking for a career, and in spring 1667 moved into Ashley's home at Exeter House

Exeter House was an early 17th-century brick-built mansion, which stood in Full Street, Derby until demolished in 1854. Named for the Earls of Exeter, whose family owned the property until 1757, the house was notable for the stay of Charles E ...

in London, ostensibly as the household physician. Beginning in 1667, Shaftesbury and Locke worked closely on the Grand Model for the Province of Carolina

The Grand Model (or "Grand Modell" as it was spelled at the time) was a utopian plan for the Province of Carolina, founded in . It consisted of a constitution coupled with a settlement and development plan for the colony. The former was titled the ...

and its centrepiece, the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina

The ''Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina'' were adopted on March 1, 1669 by the eight Lords Proprietors of the Province of Carolina, which included most of the land between what is now Virginia and Florida. It replaced the '' Charter of Caro ...

.

When Southampton died in May 1667, Ashley, as under-treasurer, was expected to succeed Southampton as Lord High Treasurer.Duke of Buckingham

Duke of Buckingham held with Duke of Chandos, referring to Buckingham, is a title that has been created several times in the peerages of England, Great Britain, and the United Kingdom. There have also been earls and marquesses of Buckingham.

...

, the Earl of Bristol, and Sir Henry Bennett, who by this point had been created Henry Bennet, 1st Earl of Arlington

Henry Bennet, 1st Earl of Arlington, KG, PC (1618 – 28 July 1685) was an English statesman.

Background and early life

He was the son of Sir John Bennet of Dawley, Middlesex, by Dorothy, daughter of Sir John Crofts of Little Saxham, Suf ...

).Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is sep ...

on a charge of treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

.Royal Africa Company

The Royal African Company (RAC) was an English mercantile ( trading) company set up in 1660 by the royal Stuart family and City of London merchants to trade along the west coast of Africa. It was led by the Duke of York, who was the brother o ...

.

After the fall of Lord Clarendon in 1667, Lord Ashley became a prominent member of the Cabal

A cabal is a group of people who are united in some close design, usually to promote their private views or interests in an ideology, a state, or another community, often by intrigue and usually unbeknownst to those who are outside their group. T ...

, in which he formed the second "A".Buckingham

Buckingham ( ) is a market town in north Buckinghamshire, England, close to the borders of Northamptonshire and Oxfordshire, which had a population of 12,890 at the United Kingdom Census 2011, 2011 Census. The town lies approximately west of ...

, Ashley, and Lauderdale

Lauderdale is the valley of the Leader Water (a tributary of the Tweed) in the Scottish Borders. It contains the town of Lauder, as well as Earlston. The valley is traversed from end to end by the A68 trunk road, which runs from Darlington to ...

) never formed a coherent ministerial team.John Wilkins

John Wilkins, (14 February 1614 – 19 November 1672) was an Anglican clergyman, natural philosopher, and author, and was one of the founders of the Royal Society. He was Bishop of Chester from 1668 until his death.

Wilkins is one of the ...

, Bishop of Chester

The Bishop of Chester is the Ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Chester in the Province of York.

The diocese extends across most of the historic county boundaries of Cheshire, including the Wirral Peninsula and has its see in ...

, in introducing government-backed bills in October 1667 and February 1668 to include moderate dissenters within the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Brit ...

.

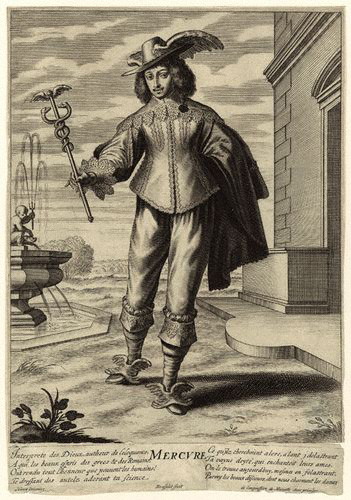

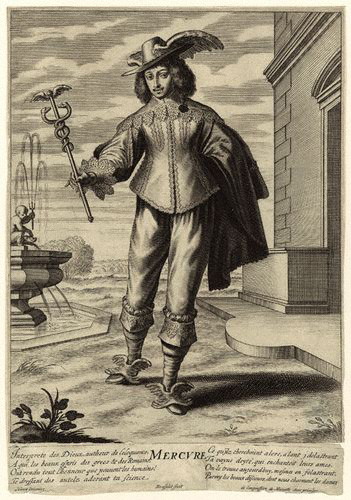

Cabal Ministry

The Cabal ministry or the CABAL refers to a group of high councillors of King Charles II of England, Scotland and Ireland from 1668 to .

The term ''Cabal'' has a double meaning in this context. It refers to the fact that, for perhaps the first ...

" widths="100px" heights="100px" perrow="5">

File:1stLordClifford.jpg,

Thomas Clifford, 1st Baron Clifford of Chudleigh (1630–1673).

File:Henry Bennett Earl of Arlington.jpg,

Henry Bennet, 1st Earl of Arlington (1618–1685).

File:2ndDukeOfBuckingham.jpg,

George Villiers, 2nd Duke of Buckingham (1628–1687).

File:Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury.jpg, Anthony Ashley Cooper, 1st Baron Ashley of Wimborne St Giles (1621–1683).

File:John Maitland, Duke of Lauderdale by Jacob Huysmans.jpg,

John Maitland, 1st Duke of Lauderdale (1616–1682).

In May 1668, Ashley became ill, apparently with a

hydatid cyst.

His secretary, John Locke, recommended an operation that almost certainly saved Ashley's life and Ashley was grateful to Locke for the rest of his life.

As part of the operation, a tube was inserted to drain fluid from the

abscess

An abscess is a collection of pus that has built up within the tissue of the body. Signs and symptoms of abscesses include redness, pain, warmth, and swelling. The swelling may feel fluid-filled when pressed. The area of redness often extends ...

, and after the operation, the physician left the tube in the body, and installed a copper tap to allow for possible future drainage.

In later years, this would be the occasion for his Tory enemies to dub him "Tapski", with the

Polish ending because Tories accused him of wanting to make England an

elective monarchy

An elective monarchy is a monarchy ruled by an elected monarch, in contrast to a hereditary monarchy in which the office is automatically passed down as a family inheritance. The manner of election, the nature of candidate qualifications, and t ...

like the

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Crown of the Kingdom of ...

.

In 1669, Ashley supported Arlington and Buckingham's proposal for a

political union

A political union is a type of political entity which is composed of, or created from, smaller polities, or the process which achieves this. These smaller polities are usually called federated states and federal territories in a federal govern ...

of England with the

Kingdom of Scotland

The Kingdom of Scotland (; , ) was a sovereign state in northwest Europe traditionally said to have been founded in 843. Its territories expanded and shrank, but it came to occupy the northern third of the island of Great Britain, sharing a l ...

, although this proposal foundered when the Scottish insisted on equal representation with the English in parliament.

Ashley probably did not support the

Conventicles Act of 1670, but he did not sign the formal protest against the passage of the act either.

Ashley, in his role as one of the eight

Lords Proprietor

A lord proprietor is a person granted a royal charter for the establishment and government of an English colony in the 17th century. The plural of the term is "lords proprietors" or "lords proprietary".

Origin

In the beginning of the European ...

of the

Province of Carolina

Province of Carolina was a province of England (1663–1707) and Great Britain (1707–1712) that existed in North America and the Caribbean from 1663 until partitioned into North and South on January 24, 1712. It is part of present-day Alabam ...

, along with his secretary,

John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism". Considered one of ...

, drafted the

Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina

The ''Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina'' were adopted on March 1, 1669 by the eight Lords Proprietors of the Province of Carolina, which included most of the land between what is now Virginia and Florida. It replaced the '' Charter of Caro ...

, which were adopted by the eight Lords Proprietor in March 1669.

By this point, it had become obvious that the queen, Catherine of Braganza, was

barren

Barren primarily refers to a state of barrenness (infertility

Infertility is the inability of a person, animal or plant to reproduce by natural means. It is usually not the natural state of a healthy adult, except notably among certain eusoc ...

and would never produce an

heir

Inheritance is the practice of receiving private property, titles, debts, entitlements, privileges, rights, and obligations upon the death of an individual. The rules of inheritance differ among societies and have changed over time. Offic ...

, making the king's brother,

James, Duke of York

James VII and II (14 October 1633 16 September 1701) was King of England and King of Ireland as James II, and King of Scotland as James VII from the death of his elder brother, Charles II, on 6 February 1685. He was deposed in the Glorious ...

heir to the throne, which worried Ashley because he suspected that James was a Roman Catholic.

Ashley, Buckingham, and

Charles Howard, 1st Earl of Carlisle urged Charles to declare his illegitimate son, the Duke of Monmouth, legitimate.

When it became clear that Charles would not do so, they urged Charles to divorce Catherine and remarry.

This was the background to the famous Roos debate case:

John Manners, Lord Roos had obtained a

separation from bed and board from his wife in 1663, after he discovered she was committing

adultery

Adultery (from Latin ''adulterium'') is extramarital sex that is considered objectionable on social, religious, moral, or legal grounds. Although the sexual activities that constitute adultery vary, as well as the social, religious, and legal ...

, and he had also been granted a divorce by an

ecclesiastical court

An ecclesiastical court, also called court Christian or court spiritual, is any of certain courts having jurisdiction mainly in spiritual or religious matters. In the Middle Ages, these courts had much wider powers in many areas of Europe than be ...

and had Lady Roos' children declared

illegitimate

Legitimacy, in traditional Western common law, is the status of a child born to parents who are legally married to each other, and of a child conceived before the parents obtain a legal divorce. Conversely, ''illegitimacy'', also known as '' ...

. In March 1670, Lord Roos asked Parliament to allow him to remarry. The debate on the Roos divorce bill became politically charged because it impacted on whether Parliament could legally allow Charles to remarry.

During the debate, Ashley spoke out strongly in favour of the Roos divorce bill, arguing that marriage was a civil contract, not a

sacrament

A sacrament is a Christian rite that is recognized as being particularly important and significant. There are various views on the existence and meaning of such rites. Many Christians consider the sacraments to be a visible symbol of the rea ...

.

Parliament ultimately gave Lord Roos permission to remarry, but Charles II never attempted to divorce his wife.

Ashley did not know about the

Secret Treaty of Dover

The Treaty of Dover, also known as the Secret Treaty of Dover, was a treaty between England and France signed at Dover on 1 June 1670. It required that Charles II of England would convert to the Roman Catholic Church at some future date and th ...

, arranged by Charles II's sister

Henrietta Anne Stuart

Henrietta Anne of England (16 June 1644 O.S. N.S.">New_Style.html" ;"title="6 June 1644 New Style">N.S.– 30 June 1670) was the youngest daughter of King Charles I of England and Queen Henrietta Maria.

Fleeing England with her mother and ...

and signed 22 May 1670, whereby Charles II concluded an alliance with

Louis XIV of France

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of ...

against the

Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands ( Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiograph ...

. Under the terms of the Secret Treaty of Dover, Charles would receive an annual subsidy from France (to enable him to govern without calling a parliament) in exchange for a promise that he would convert to Catholicism and re-Catholicize England at an unspecified future date.

Of the members of the Cabal, only Arlington and Clifford were aware of the Catholic Clauses contained in the Secret Treaty of Dover.

For the benefit of Ashley, Buckingham, and Lauderdale, Charles II arranged a mock treaty (''traité simulé'') concluding an alliance with France. Although he was suspicious of France, Ashley was also wary of Dutch commercial competition, and he, therefore, signed the mock Treaty of Dover on 21 December 1670.

Throughout 1671, Ashley argued in favour of reducing the

duty

A duty (from "due" meaning "that which is owing"; fro, deu, did, past participle of ''devoir''; la, debere, debitum, whence "debt") is a commitment or expectation to perform some action in general or if certain circumstances arise. A duty may ...

on sugar imports, arguing that the duty would have an adverse effect on colonial sugar planters.

In September 1671, Ashley and Clifford oversaw a massive reform of England's customs system, whereby customs farmers were replaced with royal commissioners responsible for collecting customs.

This change was ultimately to the benefit of the crown, but it caused a short-term loss of revenues that led to the

Great Stop of the Exchequer.

Ashley was widely blamed for the Great Stop of the Exchequer, although Clifford was the chief advocate of stopping the exchequer and Ashley in fact opposed the move.

In early 1672, with the

Third Anglo–Dutch War looming, many in the government feared that Protestant dissenters in England would form a

fifth column

A fifth column is any group of people who undermine a larger group or nation from within, usually in favor of an enemy group or another nation. According to Harris Mylonas and Scott Radnitz, "fifth columns" are “domestic actors who work to un ...

and support their Dutch co-religionists against England.

In an attempt to conciliate the Nonconformists, on 15 March 1672, Charles II issued his

Royal Declaration of Indulgence

The Royal Declaration of Indulgence was Charles II of England's attempt to extend religious liberty to Protestant nonconformists and Roman Catholics in his realms, by suspending the execution of the Penal Laws that punished recusants from the ...

, suspending the penal laws that punished non-attendance at Church of England services. Ashley strongly supported this Declaration.

According to the terms of the Treaty of Dover, England declared war on the Dutch Republic on 7 April 1672, thus launching the Third Anglo-Dutch War.

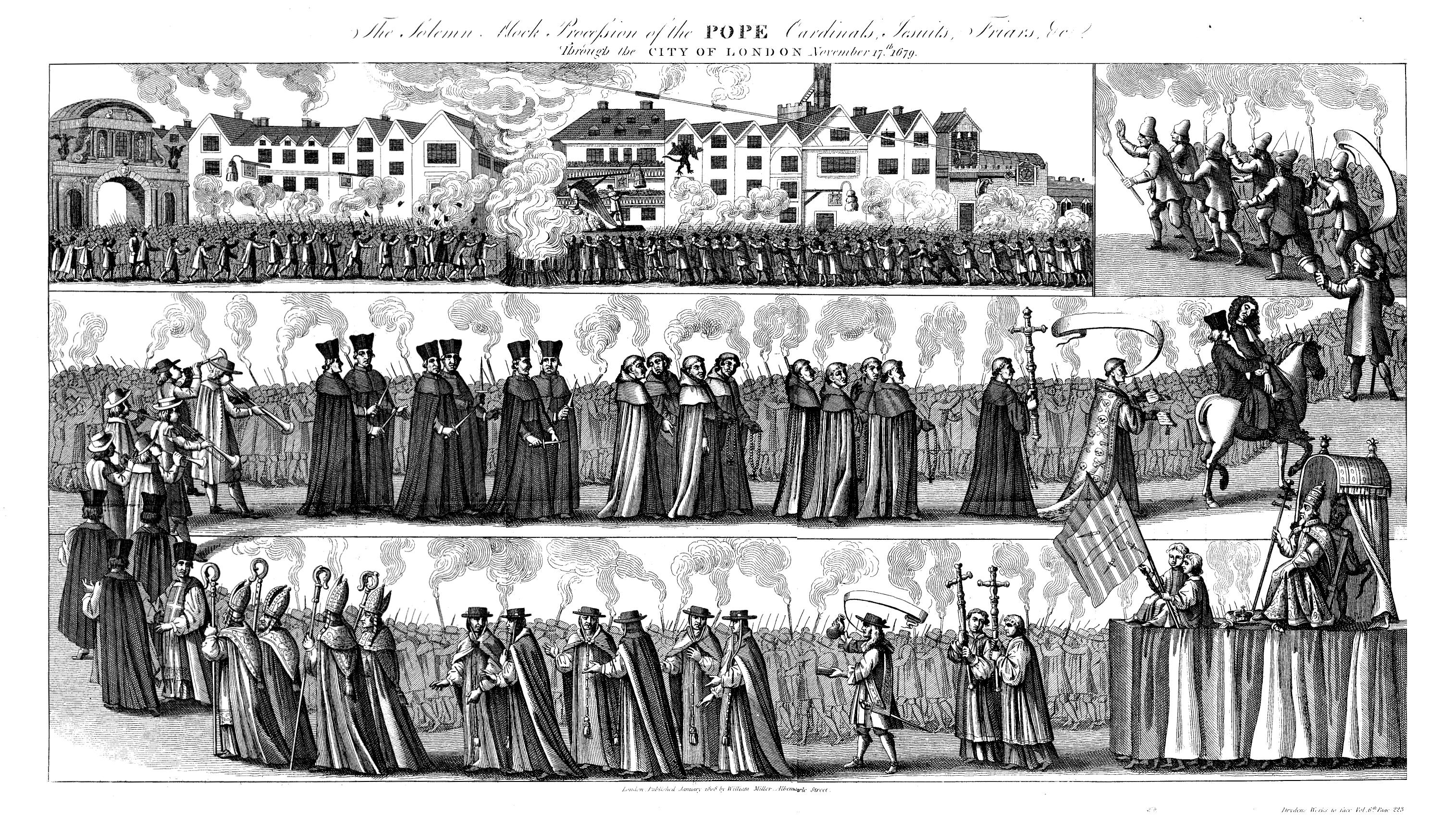

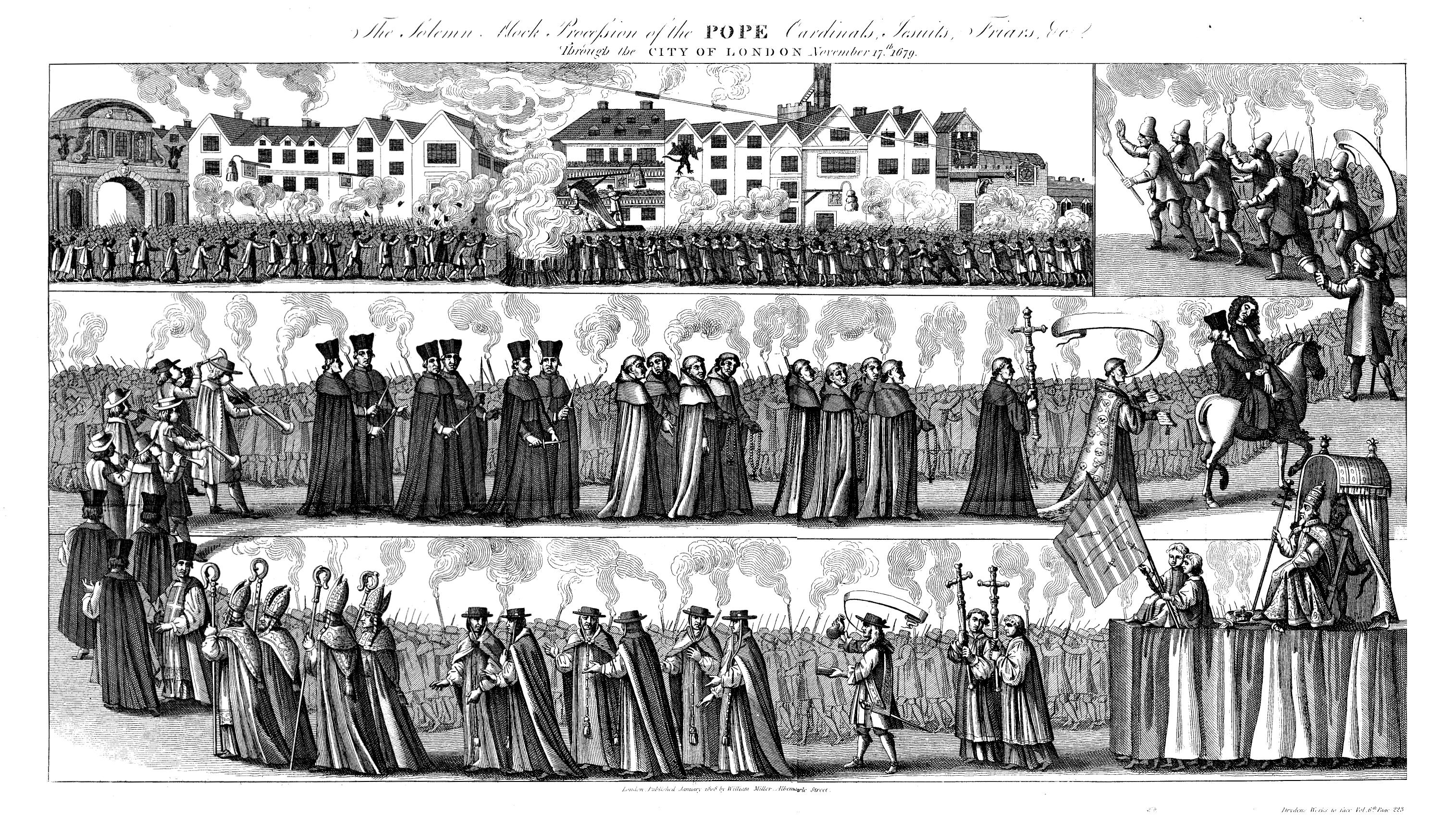

To accompany the commencement of the war, Charles issued a new round of honours, as part of which Ashley was named Earl of Shaftesbury and Baron Cooper on 23 April 1672.

In autumn 1672, Shaftesbury played a key role in setting up the

Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to 88% of the a ...

Adventurers' Company.

Lord Chancellor, 1672–1673

On 17 November 1672, the king named Shaftesbury

Lord Chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. Th ...

of England,

with

Sir John Duncombe replacing Shaftesbury as

Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the Exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and head of HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, the Ch ...

. As Lord Chancellor, he addressed the opening of a new session of the

Cavalier Parliament

The Cavalier Parliament of England lasted from 8 May 1661 until 24 January 1679. It was the longest English Parliament, and longer than any Great British or UK Parliament to date, enduring for nearly 18 years of the quarter-century reign of C ...

on 4 February 1673, calling on parliament to vote funds sufficient to carry out the war, arguing that the Dutch were the enemy of the monarchy and England's only major trade rival, and therefore had to be destroyed (at one point he exclaimed "