Anne Royall on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

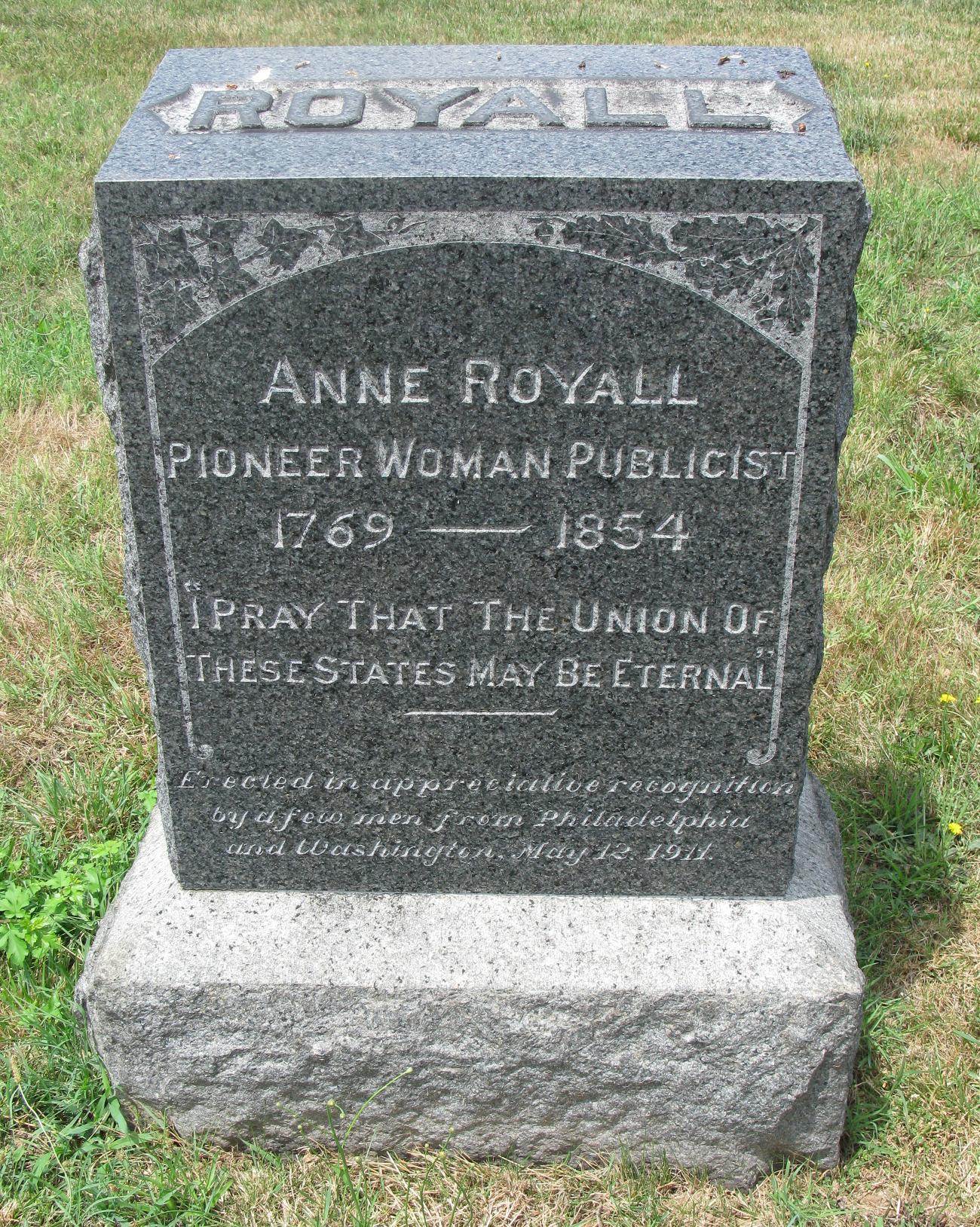

Anne Royall (June 11, 1769 – October 1, 1854) was a travel writer, newspaper editor, and, by some accounts, the first professional female

biographer Jeff Biggers

traveling first to the new state of Alabama, where she wrote the initial of her series of "Black Books". The popular volumes were "informative but sardonic portraits of the elite and their denizens from Mississippi to Maine". In an expanding nation, Royall's incisive descriptions of American life and individual Americans from many walks of life were popular reading and a sharp contrast to the sentimental literature penned by other female writers. She arrived in Washington in 1824 to petition for a federal pension as the widow of a veteran; under the pension law at the time, widows had to plead their cases beforeCongressional Cemetery Interment Records search page

/ref>

' – Retrieved May 2004 from the

The Trials of a Scold: The Incredible True Story of Writer Anne Royall

', St. Martin's Press/Thomas Dunne Books. * Elizabeth J. Clapp (2016), ''A Notorious Woman: Anne Royall in Jacksonian America'' University of Virginia Press

Governor Lincoln Gets the Anne Royall Treatment

* Daniel Walker Howe, ''What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848'' * Sarah Harvey Porter (1908)

''The life and times of Anne Royall''

Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

dramatization of her life

with

journalist

A journalist is an individual that collects/gathers information in form of text, audio, or pictures, processes them into a news-worthy form, and disseminates it to the public. The act or process mainly done by the journalist is called journalism ...

in the United States.

Early life

She was born Anne Newport inBaltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore was ...

, Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to it ...

. Anne grew up in the western frontier of Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; (Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, Mary ...

before her impoverished and fatherless family migrated south to the mountains of western Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth are ...

. There, at 16, she and her widowed mother were employed as servants in the household of William Royall, a wealthy American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

major, freemason

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

and deist

Deism ( or ; derived from the Latin ''deus'', meaning "god") is the philosophical position and rationalistic theology that generally rejects revelation as a source of divine knowledge, and asserts that empirical reason and observation of ...

who lived at Sweet Springs in Monroe County (now in West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the ...

). Royall, a learned gentleman farmer twenty years Anne's senior, took an interest in her and arranged for her education, introducing her to the works of Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

and Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his '' nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his criticism of Christianity— ...

, and allowing her to make free use of his extensive library.

Marriage

Anne and William Royall were wed in 1797. The couple lived comfortably together for fifteen years until his death in 1812. His death touched off litigation between Anne and Royall's relatives, who claimed that they were never legally married and that his will leaving her most of his property was a forgery. After seven years, the will was nullified and she was left virtually penniless.Career in journalism

Anne spent the next four years traveling aroundAlabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = " Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County

, LargestMetro = Greater Birmingham

, area_total_km2 = 135,7 ...

, writing letters to a friend about the evolution of the young state that were eventually turned into a manuscript published as ''Letters from Alabama''. She also penned a novel called ''The Tennessean'' before setting off for Washington D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, N ...

She became an "itinerant storyteller", according tbiographer Jeff Biggers

traveling first to the new state of Alabama, where she wrote the initial of her series of "Black Books". The popular volumes were "informative but sardonic portraits of the elite and their denizens from Mississippi to Maine". In an expanding nation, Royall's incisive descriptions of American life and individual Americans from many walks of life were popular reading and a sharp contrast to the sentimental literature penned by other female writers. She arrived in Washington in 1824 to petition for a federal pension as the widow of a veteran; under the pension law at the time, widows had to plead their cases before

Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

. She remained unsatisfied until Congress passed a new pension law in 1848. Even then, her husband's family claimed most of her pension money.

While in Washington attempting to secure a pension, Anne caught President John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States S ...

during one of his usual early morning naked swims in the Potomac River

The Potomac River () drains the Mid-Atlantic United States, flowing from the Potomac Highlands into Chesapeake Bay. It is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map. Retrieved Augu ...

. It is commonly recounted, but apocryphal, that she gathered the president's clothes and sat on them until he answered her questions, earning her the first presidential interview ever granted to a woman.

Adams afterward supported Anne's petition for a pension. He also invited her to visit his wife, Louisa Adams

Louisa Catherine Adams ( ''née'' Johnson; February 12, 1775 – May 15, 1852) was the First Lady of the United States from 1825 to 1829 during the presidency of John Quincy Adams.

Early life

Adams was born on February 12, 1775, in the City ...

, at their home in Washington, which she did. Mrs. Adams gave her a white shawl when she journeyed north to obtain proof of her husband's military service.

Afterward Anne toured New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

, Pennsylvania, New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* ...

and Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

, all the while taking copious notes and using her Masonic connections to help fund her travels.

In Boston, she stopped in on former President John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Before his presidency, he was a leader of t ...

to give him an update on his son and daughter-in-law. Then, in 1826, at 57, she published her notes in a book titled ''Sketches of History, Life and Manners in the United States''. Her previous manuscript ''The Tennessean'' would follow a year later.

The caustic observations in her books and public stances on issues caused a stir and earned her some powerful enemies. She was derided as an eccentric scold, a virago

A virago is a woman who demonstrates abundant masculine virtues. The word comes from the Latin word ''virāgō'' (genitive virāginis) meaning vigorous' from ''vir'' meaning "man" or "man-like" (cf. virile and virtue) to which the suffix ''-āg ...

, and (in the words of one newspaper editor) "a literary wild-cat from the backwoods". In 1829, Anne Royall returned to Washington, D.C. and began living on Capitol Hill

Capitol Hill, in addition to being a metonym for the United States Congress, is the largest historic residential neighborhood in Washington, D.C., stretching easterly in front of the United States Capitol along wide avenues. It is one of the ...

, near a fire house. The firehouse, which had been built with federal money, had been allowing a small Presbyterian congregation to use its facilities for their services. Royall, who had long made Presbyterians a particular object of scorn in her writing, objected to their using the building as a blurring of the lines between church and state. She also claimed that some of the congregation's children began throwing stones at her windows. One member of the congregation began praying silently beneath her window and others visited her in an attempt to convert her, she claimed. Royall responded to their taunts with cursing and was arrested. She was tried and convicted of being a "public nuisance, a common brawler and a common scold

Common may refer to:

Places

* Common, a townland in County Tyrone, Northern Ireland

* Boston Common, a central public park in Boston, Massachusetts

* Cambridge Common, common land area in Cambridge, Massachusetts

* Clapham Common, originally co ...

". Although a ducking stool

Cucking stools or ducking stools were chairs formerly used for punishment of disorderly women, scolds, and dishonest tradesmen in England, Scotland, and elsewhere. The cucking-stool was a form of or "women's punishment," as referred to in La ...

had been constructed nearby, the court ruled that the traditional common law punishment of ducking for a scold was obsolete, and she was instead fined $10. Two reporters from Washington's newspaper, '' The National Intelligencer'', paid the fine. Embarrassed by the incident, Royall left Washington to continue traveling.

Back in Washington in 1831, she published a newspaper from her home with the help of a friend, Sally Stack. The paper, ''Paul Pry'', exposed political corruption and fraud. Sold as single issues, it contained her editorials, letters to the editor and her responses, and advertisements. It was published until 1836, when it was succeeded by ''The Huntress''. Royall hired orphans to set the type and faced constant financial woes, which were exacerbated when postmasters refused to deliver her issues to subscribers, until her death at 85 in 1854, bringing an end to her 30-year news career.

She is buried in the Congressional Cemetery

The Congressional Cemetery, officially Washington Parish Burial Ground, is a historic and active cemetery located at 1801 E Street, SE, in Washington, D.C., on the west bank of the Anacostia River. It is the only American "cemetery of national ...

./ref>

References

Further reading

* ''Original text based o' – Retrieved May 2004 from the

Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It is the oldest federal cultural institution in the country. The library ...

' online archives

* Jeff Biggers (2017), The Trials of a Scold: The Incredible True Story of Writer Anne Royall

', St. Martin's Press/Thomas Dunne Books. * Elizabeth J. Clapp (2016), ''A Notorious Woman: Anne Royall in Jacksonian America'' University of Virginia Press

Governor Lincoln Gets the Anne Royall Treatment

* Daniel Walker Howe, ''What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848'' * Sarah Harvey Porter (1908)

''The life and times of Anne Royall''

Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

External links

*Cavalcade of America

''Cavalcade of America'' is an anthology drama series that was sponsored by the DuPont Company, although it occasionally presented musicals, such as an adaptation of ''Show Boat'', and condensed biographies of popular composers. It was initially ...

– February 20, 1940, radidramatization of her life

with

Ethel Barrymore

Ethel Barrymore (born Ethel Mae Blythe; August 15, 1879 – June 18, 1959) was an American actress and a member of the Barrymore family of actors. Barrymore was a stage, screen and radio actress whose career spanned six decades, and was regarde ...

, via YouTube

{{DEFAULTSORT:Royall, Anne

1769 births

1854 deaths

19th-century American women writers

American women journalists

American women novelists

Burials at the Congressional Cemetery

Writers from Baltimore

People from Monroe County, West Virginia

19th-century American novelists

Novelists from West Virginia

Novelists from Maryland

19th-century American journalists