Angevin Kings Of England on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Angevins (; "from

The adjective Angevin is especially used in English history to refer to the kings who were also counts of Anjoubeginning with Henry IIdescended from Geoffrey and Matilda; their characteristics, descendants and the period of history which they covered from the mid-twelfth to early-thirteenth centuries. In addition, it is also used pertaining to Anjou, or any sovereign, government derived from this. As a noun, it is used for any native of Anjou or Angevin ruler. As such, Angevin is also used for other

The adjective Angevin is especially used in English history to refer to the kings who were also counts of Anjoubeginning with Henry IIdescended from Geoffrey and Matilda; their characteristics, descendants and the period of history which they covered from the mid-twelfth to early-thirteenth centuries. In addition, it is also used pertaining to Anjou, or any sovereign, government derived from this. As a noun, it is used for any native of Anjou or Angevin ruler. As such, Angevin is also used for other

Henry I of England named his daughter

Henry I of England named his daughter

On the day of Richard's English coronation, there was a mass slaughter of Jews, described by

On the day of Richard's English coronation, there was a mass slaughter of Jews, described by  John's French defeats weakened his position in England. The rebellion of his English vassals resulted in ''

John's French defeats weakened his position in England. The rebellion of his English vassals resulted in ''

Henry was an unpopular king, and few grieved his death; William of Newburgh wrote during the 1190s, "In his own time he was hated by almost everyone". He was widely criticised by contemporaries, even in his own court. Henry's son Richard's contemporary image was more nuanced, since he was the first king who was also a

Henry was an unpopular king, and few grieved his death; William of Newburgh wrote during the 1190s, "In his own time he was hated by almost everyone". He was widely criticised by contemporaries, even in his own court. Henry's son Richard's contemporary image was more nuanced, since he was the first king who was also a

Anjou Anjou may refer to:

Geography and titles France

*County of Anjou, a historical county in France and predecessor of the Duchy of Anjou

**Count of Anjou, title of nobility

*Duchy of Anjou, a historical duchy and later a province of France

**Duke ...

") were a royal house of French origin that ruled England in the 12th and early 13th centuries; its monarchs were Henry II, Richard I

Richard I (8 September 1157 – 6 April 1199) was King of England from 1189 until his death in 1199. He also ruled as Duke of Normandy, Aquitaine and Gascony, Lord of Cyprus, and Count of Poitiers, Anjou, Maine, and Nantes, and was ...

and John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

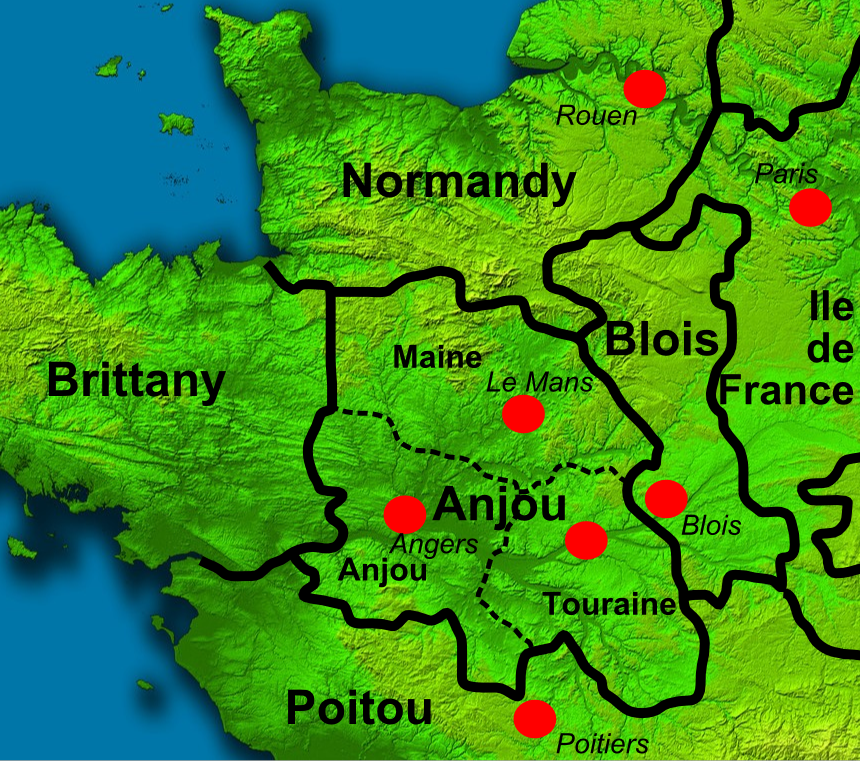

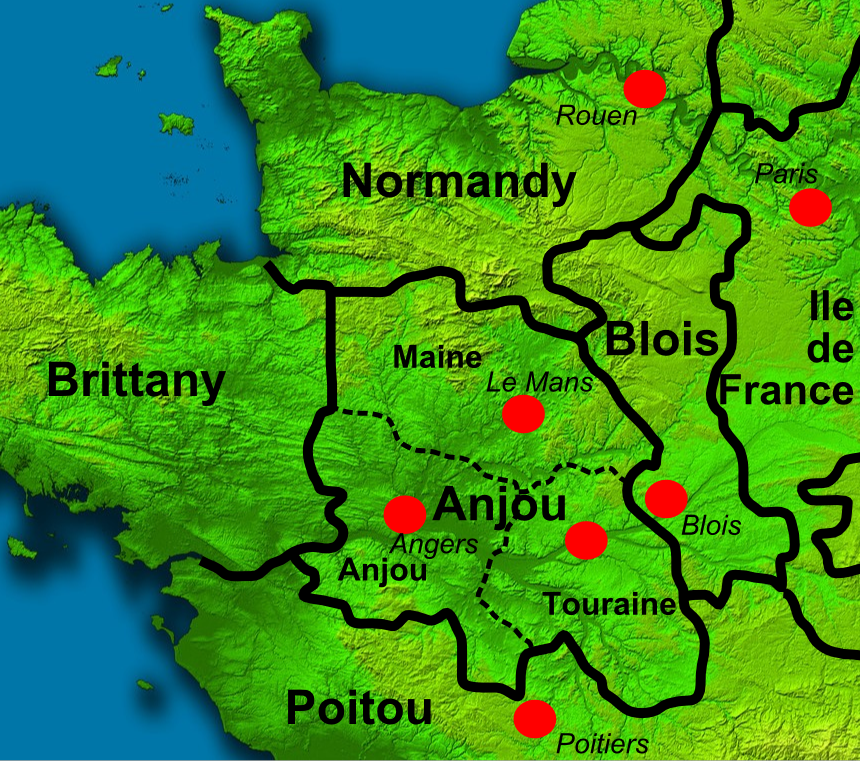

. In the 10 years from 1144, two successive counts of Anjou

The Count of Anjou was the ruler of the County of Anjou, first granted by Charles the Bald in the 9th century to Robert the Strong. Ingelger and his son, Fulk the Red, were viscounts until Fulk assumed the title of Count of Anjou. The Robertians ...

in France, Geoffrey and his son, the future Henry II, won control of a vast assemblage of lands in western Europe that would last for 80 years and would retrospectively be referred to as the Angevin Empire

The Angevin Empire (; french: Empire Plantagenêt) describes the possessions of the House of Plantagenet during the 12th and 13th centuries, when they ruled over an area covering roughly half of France, all of England, and parts of Ireland and W ...

. As a political entity this was structurally different from the preceding Norman and subsequent Plantagenet

The House of Plantagenet () was a royal house which originated from the lands of Anjou in France. The family held the English throne from 1154 (with the accession of Henry II at the end of the Anarchy) to 1485, when Richard III died in b ...

realms. Geoffrey became Duke of Normandy

In the Middle Ages, the duke of Normandy was the ruler of the Duchy of Normandy in north-western France. The duchy arose out of a grant of land to the Viking leader Rollo by the French king Charles III in 911. In 924 and again in 933, Normand ...

in 1144 and died in 1151. In 1152, his heir, Henry, added Aquitaine

Aquitaine ( , , ; oc, Aquitània ; eu, Akitania; Poitevin-Saintongeais: ''Aguiéne''), archaic Guyenne or Guienne ( oc, Guiana), is a historical region of southwestern France and a former administrative region of the country. Since 1 Janu ...

by virtue of his marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine

Eleanor ( – 1 April 1204; french: Aliénor d'Aquitaine, ) was Queen of France from 1137 to 1152 as the wife of King Louis VII, List of English royal consorts, Queen of England from 1154 to 1189 as the wife of Henry II of England, King Henry I ...

. Henry also inherited the claim of his mother, Empress Matilda

Empress Matilda ( 7 February 110210 September 1167), also known as the Empress Maude, was one of the claimants to the English throne during the civil war known as the Anarchy. The daughter of King Henry I of England, she moved to Germany as ...

, the daughter of King Henry I, to the English throne, to which he succeeded in 1154 following the death of King Stephen.

Henry was succeeded by his third son, Richard

Richard is a male given name. It originates, via Old French, from Old Frankish and is a compound of the words descending from Proto-Germanic ''*rīk-'' 'ruler, leader, king' and ''*hardu-'' 'strong, brave, hardy', and it therefore means 'stro ...

, whose reputation for martial prowess won him the epithet "" or "Lionheart". He was born and raised in England but spent very little time there during his adult life, perhaps as little as six months. Despite this Richard remains an enduring icon

An icon () is a religious work of art, most commonly a painting, in the cultures of the Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and Catholic churches. They are not simply artworks; "an icon is a sacred image used in religious devotion". The mos ...

ic figure both in England and in France, and is one of very few kings of England remembered by his nickname as opposed to regnal number

Regnal numbers are ordinal numbers used to distinguish among persons with the same name who held the same office. Most importantly, they are used to distinguish monarchs. An ''ordinal'' is the number placed after a monarch's regnal name to differ ...

.

When Richard died, his brother John – Henry's fifth and last surviving son – took the throne. In 1204, John lost many of the Angevins' continental territories, including Anjou, to the French crown. He and his successors were still recognized as dukes of Aquitaine

The Duke of Aquitaine ( oc, Duc d'Aquitània, french: Duc d'Aquitaine, ) was the ruler of the medieval region of Aquitaine (not to be confused with modern-day Aquitaine) under the supremacy of Frankish, English, and later French kings.

As succ ...

. The loss of Anjou, for which the dynasty is named, is the rationale behind John's son, Henry III of England

Henry III (1 October 1207 – 16 November 1272), also known as Henry of Winchester, was King of England, Lord of Ireland, and Duke of Aquitaine from 1216 until his death in 1272. The son of King John and Isabella of Angoulême, Henry ...

, being considered the first Plantagenet

The House of Plantagenet () was a royal house which originated from the lands of Anjou in France. The family held the English throne from 1154 (with the accession of Henry II at the end of the Anarchy) to 1485, when Richard III died in b ...

a name derived from the nickname of his great-grandfather, Geoffrey. Where no distinction is made between the Angevinsand Angevin eraand subsequent English kings, Henry II is the first Plantagenet king. From John, the dynasty continued successfully and unbroken in the senior male line until the reign of Richard II

Richard II (6 January 1367 – ), also known as Richard of Bordeaux, was King of England from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399. He was the son of Edward the Black Prince, Prince of Wales, and Joan, Countess of Kent. Richard's father ...

before dividing into two competing cadet branch

In history and heraldry, a cadet branch consists of the male-line descendants of a monarch's or patriarch's younger sons ( cadets). In the ruling dynasties and noble families of much of Europe and Asia, the family's major assets— realm, t ...

es, the House of Lancaster

The House of Lancaster was a cadet branch of the royal House of Plantagenet. The first house was created when King Henry III of England created the Earldom of Lancasterfrom which the house was namedfor his second son Edmund Crouchback in 126 ...

and the House of York

The House of York was a cadet branch of the English royal House of Plantagenet. Three of its members became kings of England in the late 15th century. The House of York descended in the male line from Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of Yor ...

. In the 17th century, historians would use the term "Plantagenet" when describing the house.

Terminology

Angevin

The adjective Angevin is especially used in English history to refer to the kings who were also counts of Anjoubeginning with Henry IIdescended from Geoffrey and Matilda; their characteristics, descendants and the period of history which they covered from the mid-twelfth to early-thirteenth centuries. In addition, it is also used pertaining to Anjou, or any sovereign, government derived from this. As a noun, it is used for any native of Anjou or Angevin ruler. As such, Angevin is also used for other

The adjective Angevin is especially used in English history to refer to the kings who were also counts of Anjoubeginning with Henry IIdescended from Geoffrey and Matilda; their characteristics, descendants and the period of history which they covered from the mid-twelfth to early-thirteenth centuries. In addition, it is also used pertaining to Anjou, or any sovereign, government derived from this. As a noun, it is used for any native of Anjou or Angevin ruler. As such, Angevin is also used for other counts and dukes of Anjou

The Count of Anjou was the ruler of the County of Anjou, first granted by Charles the Bald in the 9th century to Robert the Strong. Ingelger and his son, Fulk the Red, were viscounts until Fulk assumed the title of Count of Anjou. The Robertian ...

; including the three kings' ancestors, their cousins who held the crown of Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

and unrelated later members of the French royal family who were granted the titles to form different dynasties amongst which were the Capetian House of Anjou

The Capetian House of Anjou or House of Anjou-Sicily, was a royal house and cadet branch of the direct French House of Capet, part of the Capetian dynasty. It is one of three separate royal houses referred to as ''Angevin'', meaning "from Anjou" ...

and the Valois House of Anjou.

Angevin Empire

The term "Angevin Empire

The Angevin Empire (; french: Empire Plantagenêt) describes the possessions of the House of Plantagenet during the 12th and 13th centuries, when they ruled over an area covering roughly half of France, all of England, and parts of Ireland and W ...

" was coined in 1887 by Kate Norgate. As far as it is known, there was no contemporary name for this assemblage of territories, which were referred toif at allby clumsy circumlocutions such as ''our kingdom and everything subject to our rule whatever it may be'' or ''the whole of the kingdom which had belonged to his father''. Whereas the Angevin part of this term has proved uncontentious, the empire portion has proved controversial. In 1986, a convention of historical specialists concluded that there had been no Angevin state and no empire but the term ''espace Plantagenet'' was acceptable.

''Plantagenet''

Richard of York, 3rd Duke of York

Richard of York, 3rd Duke of York (21 September 1411 – 30 December 1460), also named Richard Plantagenet, was a leading English magnate and claimant to the throne during the Wars of the Roses. He was a member of the ruling House of Plantage ...

, adopted Plantagenet as his family name in the 15th century. ''Plantegenest'' (or ''Plante Genest'') had been a 12th-century nickname for his ancestor Geoffrey, Count of Anjou

The Count of Anjou was the ruler of the County of Anjou, first granted by Charles the Bald in the 9th century to Robert the Strong. Ingelger and his son, Fulk the Red, were viscounts until Fulk assumed the title of Count of Anjou. The Robertians ...

and Duke of Normandy

In the Middle Ages, the duke of Normandy was the ruler of the Duchy of Normandy in north-western France. The duchy arose out of a grant of land to the Viking leader Rollo by the French king Charles III in 911. In 924 and again in 933, Normand ...

. One of many popular theories suggests the blossom of common broom

''Cytisus scoparius'' ( syn. ''Sarothamnus scoparius''), the common broom or Scotch broom, is a deciduous leguminous shrub native to western and central Europe. In Britain and Ireland, the standard name is broom; this name is also used for other ...

, a bright yellow ("gold") flowering plant, genista

Genista is a genus of flowering plants in the legume family Fabaceae, native to open habitats such as moorland and pasture in Europe and western Asia. They include species commonly called broom, though the term may also refer to other genera, i ...

in medieval Latin

Medieval Latin was the form of Literary Latin used in Roman Catholic Western Europe during the Middle Ages. In this region it served as the primary written language, though local languages were also written to varying degrees. Latin functioned ...

, as the source of the nickname.

It is uncertain why Richard chose this specific name, although, during the Wars of the Roses

The Wars of the Roses (1455–1487), known at the time and for more than a century after as the Civil Wars, were a series of civil wars fought over control of the throne of England, English throne in the mid-to-late fifteenth century. These w ...

, it emphasised Richard's status as Geoffrey's patrilineal descendant. The retrospective usage of the name for all of Geoffrey's male-line descendants was popular during the subsequent Tudor dynasty

The House of Tudor was a royal house of largely Welsh and English origin that held the English throne from 1485 to 1603. They descended from the Tudors of Penmynydd and Catherine of France. Tudor monarchs ruled the Kingdom of England and it ...

, perhaps encouraged by the further legitimacy it gave to Richard's great-grandson, Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

. In the late 17th century, this name passed into common usage among historians.

Origins

The Angevins descend fromGeoffrey II, Count of Gâtinais Geoffrey II, de Château-Landon (died 1043 or 1046) was the Count of Gâtinais.John Burke & Sir Bernard Burke, C.B., ''Burke's Peerage, Baronetage, and Knightage'', Edited by Peter Townsend (Burke's Peerage Ltd.,London, 1963)p. xciiiDetlev Schwenni ...

and Ermengarde of Anjou. In 1060 this couple inherited, via cognatic kinship

Cognatic kinship is a mode of descent calculated from an ancestor counted through any combination of male and female links, or a system of bilateral kinship where relations are traced through both a father and mother. Such relatives may be known ...

, the county of Anjou from an older line dating from 870 and a noble called Ingelger

Ingelger (died 888), also called Ingelgarius, was a Frankish nobleman, who was the founder of the County of Anjou and of the original House of Anjou. Later generations of his family believed that he was the son of Tertullus (Tertulle) and Petron ...

. The marriage of Count Geoffrey to Matilda, the only surviving legitimate child of Henry I of England

Henry I (c. 1068 – 1 December 1135), also known as Henry Beauclerc, was King of England from 1100 to his death in 1135. He was the fourth son of William the Conqueror and was educated in Latin and the liberal arts. On William's death in ...

, was part of a struggle for power during the tenth and eleventh centuries among the lords of Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

, Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known as Armorica during the period ...

, Poitou

Poitou (, , ; ; Poitevin: ''Poetou'') was a province of west-central France whose capital city was Poitiers. Both Poitou and Poitiers are named after the Pictones Gallic tribe.

Geography

The main historical cities are Poitiers (historical c ...

, Blois

Blois ( ; ) is a commune and the capital city of Loir-et-Cher department, in Centre-Val de Loire, France, on the banks of the lower Loire river between Orléans and Tours.

With 45,898 inhabitants by 2019, Blois is the most populated city of the ...

, Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and nor ...

and the kings of France. It was from this marriage that Geoffrey's son, Henry, inherited the claims to England, Normandy and Anjou that marks the beginning of the Angevin and Plantagenet dynasties. This was the third attempt by Geoffrey's father Fulk V to build a political alliance with Normandy. The first was by marrying his daughter Matilda

Matilda or Mathilda may refer to:

Animals

* Matilda (chicken) (1990–2006), World's Oldest Living Chicken record holder

* Matilda (horse) (1824–1846), British Thoroughbred racehorse

* Matilda, a dog of the professional wrestling tag-team The ...

to Henry's heir William Adelin

William Ætheling (, ; 5 August 1103 – 25 November 1120), commonly called Adelin (sometimes ''Adelinus'', ''Adelingus'', ''A(u)delin'' or other Latinised Norman-French variants of ''Ætheling'') was the son of Henry I of England by his wife M ...

, who drowned in the wreck of the ''White Ship

The ''White Ship'' (french: la Blanche-Nef; Medieval Latin: ''Candida navis'') was a vessel transporting many nobles, including the heir to the English throne, that sank in the Channel during a trip from France to England near the Normandy ...

''. Fulk then married his daughter Sibylla to William Clito

William Clito (25 October 110228 July 1128) was a member of the House of Normandy who ruled the County of Flanders from 1127 until his death and unsuccessfully claimed the Duchy of Normandy. As the son of Robert Curthose, the eldest son of William ...

, heir to Henry's older brother Robert Curthose

Robert Curthose, or Robert II of Normandy ( 1051 – 3 February 1134, french: Robert Courteheuse / Robert II de Normandie), was the eldest son of William the Conqueror and succeeded his father as Duke of Normandy in 1087, reigning until 1106. ...

, but Henry had the marriage annulled to avoid strengthening William's rival claim to his lands.

Inheritance custom and Angevin practice

As society became more prosperous and stable in the 11th century, inheritance customs developed that allowed daughters (in the absence of sons) to succeed to principalities as well as landed estates. The twelfth-century chroniclerRalph de Diceto

Ralph de Diceto (or Ralph of Diss; c. 1120c. 1202) was archdeacon of Middlesex, dean of St Paul's Cathedral (from c. 1180), and author of two chronicles, the ''Abbreviationes chronicorum'' and the ''Ymagines historiarum''.

Early career

Ralph is ...

noted that the counts of Anjou extended their dominion over their neighbours by marriage rather than conquest. The marriage of Geoffrey to the daughter of a king (and widow of an emperor) occurred in this context. It is unknown whether King Henry intended to make Geoffrey his heir, but it is known that the threat presented by William Clito's rival claim to the duchy of Normandy made his negotiating position very weak. Even so, it is probable that, should the marriage be childless, King Henry would have attempted to be succeeded by one of his Norman kinsmen such as Theobald II, Count of Champagne Theobald is a Germanic dithematic name, composed from the elements '' theod-'' "people" and ''bald'' "bold". The name arrived in England with the Normans.

The name occurs in many spelling variations, including Theudebald, Diepold, Theobalt, Tyba ...

, or Stephen of Blois

Stephen (1092 or 1096 – 25 October 1154), often referred to as Stephen of Blois, was King of England from 22 December 1135 to his death in 1154. He was Count of Boulogne ''jure uxoris'' from 1125 until 1147 and Duke of Normandy from 1135 unti ...

, who in the event did seize King Henry's English crown. King Henry's great relief in 1133 at the birth of a son to the couple, described as "the heir to the Kingdom", is understandable in the light of this situation. Following this, the birth of a second son raised the question of whether custom would be followed with the maternal inheritance passing to first born and the paternal inheritance going to his brother, Geoffrey.

According to William of Newburgh

William of Newburgh or Newbury ( la, Guilelmus Neubrigensis, ''Wilhelmus Neubrigensis'', or ''Willelmus de Novoburgo''. 1136 – 1198), also known as William Parvus, was a 12th-century English historian and Augustinian canon of Anglo-Saxon de ...

, writing in the 1190s, the plan failed because of Geoffrey's early death in 1151. The dying Geoffrey decided that Henry would have the paternal and maternal inheritances while he needed the resources to overcome Stephen, and left instructions that his body would not be buried until Henry swore an oath that, once England and Normandy were secured, the younger Geoffrey would have Anjou. Henry's brother Geoffrey died in 1158, too soon to receive Anjou, but not before being installed count in Nantes after Henry aided a rebellion by its citizens against their previous lord.

The unity of Henry's assemblage of domains was largely dependent on the ruling family, influencing the opinion of most historians that this instability made it unlikely to endure. The French custom of partible inheritance at the time would lead to political fragmentation. Indeed, if Henry II's sons Henry the Young King and Geoffrey of Brittany had not died young, the inheritance of 1189 would have been fundamentally altered. Henry and Richard both planned for partition on their deaths while attempting to provide overriding sovereignty to hold the lands together. For example, in 1173 and 1183, Henry tried to force Richard to acknowledge allegiance to his older brother for the duchy of Aquitaine, and later Richard would confiscate Ireland from John. This was complicated by the Angevins being subjects of the kings of France, who felt these feudal rights of homage and the right of allegiance more legally belonged to them. This was particularly true when the wardship of Geoffrey's son Arthur and lordship of Brittany was contended between 1202 and 1204. Upon the Young King's death in 1183, Richard became heir in chief, but refused to give up Aquitaine to give John an inheritance. More by accident than design this meant that, while Richard inherited the patrimony, John would become lord of Ireland and Arthur would be duke of Brittany. By the mid-thirteenth century, there was a clear unified patrimony and Plantagenet empire but this cannot be called an ''Angevin Empire'' as by this date Anjou and most of the continental lands had been lost.

Arrival in England

Matilda

Matilda or Mathilda may refer to:

Animals

* Matilda (chicken) (1990–2006), World's Oldest Living Chicken record holder

* Matilda (horse) (1824–1846), British Thoroughbred racehorse

* Matilda, a dog of the professional wrestling tag-team The ...

heir; but when he died in 1135 Matilda was far from England in Anjou or Maine, while her cousin Stephen

Stephen or Steven is a common English first name. It is particularly significant to Christians, as it belonged to Saint Stephen ( grc-gre, Στέφανος ), an early disciple and deacon who, according to the Book of Acts, was stoned to death; ...

was closer in Boulogne, giving him the advantage he needed to race to England and have himself crowned and anointed king of England. Matilda's husband Geoffrey, though he had little interest in England, commenced a long struggle for the duchy of Normandy.. To create a second front, Matilda landed in England during 1139 to challenge Stephen, instigating the civil war known as the Anarchy

The Anarchy was a civil war in England and Normandy between 1138 and 1153, which resulted in a widespread breakdown in law and order. The conflict was a war of succession precipitated by the accidental death of William Adelin, the only legi ...

. In 1141, she captured Stephen at the battle of Lincoln, prompting the collapse of his support. While Geoffrey pushed on with the conquest of Normandy over the next four years, Matilda threw away her position through arrogance and inability to be magnanimous in victory. She was even forced to release Stephen in a hostage exchange for her half-brother Robert, 1st Earl of Gloucester

Robert FitzRoy, 1st Earl of Gloucester (c. 1090 – 31 October 1147David Crouch, 'Robert, first earl of Gloucester (b. c. 1090, d. 1147)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 200Retrieved ...

, allowing Stephen to resume control of much of England. Geoffrey never visited England to offer practical assistance, but instead sent Henry as a male figureheadbeginning in 1142 when Henry was only 9with a view that if England was conquered it would be Henry that would become king. In 1150, Geoffrey also transferred the title of Duke of Normandy to Henry but retained the dominant role in governance. Three fortuitous events allowed Henry to finally bring the conflict to a successful conclusion:

* In 1151, Count Geoffrey died before having time to complete his plan to divide his inheritance between his sons Henry and Geoffrey, who would have received England and Anjou respectively.

* Louis VII of France

Louis VII (1120 – 18 September 1180), called the Younger, or the Young (french: link=no, le Jeune), was King of the Franks from 1137 to 1180. He was the son and successor of King Louis VI (hence the epithet "the Young") and married Duchess ...

divorced Eleanor of Aquitaine

Eleanor ( – 1 April 1204; french: Aliénor d'Aquitaine, ) was Queen of France from 1137 to 1152 as the wife of King Louis VII, List of English royal consorts, Queen of England from 1154 to 1189 as the wife of Henry II of England, King Henry I ...

whom Henry quickly married, greatly increasing his resources and power with the acquisition of Duchy of Aquitaine

The Duchy of Aquitaine ( oc, Ducat d'Aquitània, ; french: Duché d'Aquitaine, ) was a historical fiefdom in western, central, and southern areas of present-day France to the south of the river Loire, although its extent, as well as its name, flu ...

.

* In 1153, Stephen's son Eustace

Eustace, also rendered Eustis, ( ) is the rendition in English of two phonetically similar Greek given names:

*Εὔσταχυς (''Eústachys'') meaning "fruitful", "fecund"; literally "abundant in grain"; its Latin equivalents are ''Fæcundus/Fe ...

died. The disheartened Stephen, who had also recently been widowed, gave up the fight and, with the Treaty of Wallingford

The Treaty of Wallingford, also known as the Treaty of Winchester or the Treaty of Westminster, was an agreement reached in England in the summer of 1153. It effectively ended a civil war known as '' the Anarchy'' (1135–54), caused by a dispute ...

, repeated the peace offer that Matilda had rejected in 1142: Stephen would be king for life, Henry his successor, preserving Stephen's second son William

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Engl ...

's rights to his family estates. Stephen did not live long and so Henry inherited in late 1154.

Henry faced many challenges to secure possession of his father's and grandfathers’ lands that required the reassertion and extension of old suzerainties. In 1162 Theobald Theobald is a Germanic dithematic name, composed from the elements '' theod-'' "people" and ''bald'' "bold". The name arrived in England with the Normans.

The name occurs in many spelling variations, including Theudebald, Diepold, Theobalt, Tyb ...

, Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Just ...

, died, and Henry saw an opportunity to re-establish what he saw as his rights over the church in England by appointing his friend Thomas Becket

Thomas Becket (), also known as Saint Thomas of Canterbury, Thomas of London and later Thomas à Becket (21 December 1119 or 1120 – 29 December 1170), was an English nobleman who served as Lord Chancellor from 1155 to 1162, and the ...

to succeed him. Instead, Becket proved to be an inept politician whose defiance alienated the king and his counsellors. Henry and Becket clashed repeatedly: over church tenures, Henry's brother's marriage and taxation. Henry reacted by getting Becket, and other members of the English episcopate, to recognise sixteen ancient customsgoverning relations between the king, his courts, and the churchin writing for the first time in the Constitutions of Clarendon

The Constitutions of Clarendon were a set of legislative procedures passed by Henry II of England in 1164. The Constitutions were composed of 16 articles and represent an attempt to restrict ecclesiastical privileges and curb the power of the Chur ...

. When Becket tried to leave the country without permission, Henry attempted to ruin him by laying a number of suits relating to Becket's time as chancellor. In response Becket fled into exile for five years. Relations later improved, allowing Becket's return, but soured again when Becket saw the coronation of Henry's son as coregent

A coregency is the situation where a monarchical position (such as prince, princess, king, queen, emperor or empress), normally held by only a single person, is held by two or more. It is to be distinguished from diarchies or duumvirates such ...

by the Archbishop of York

The archbishop of York is a senior bishop in the Church of England, second only to the archbishop of Canterbury. The archbishop is the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of York and the metropolitan bishop of the province of York, which covers ...

as a challenge to his authority and excommunicated those who had offended him. When he heard the news, Henry said: "What miserable drones and traitors have I nurtured and promoted in my household who let their lord be treated with such shameful contempt by a low-born clerk." Three of Henry's men killed Becket in Canterbury Cathedral

Canterbury Cathedral in Canterbury, Kent, is one of the oldest and most famous Christian structures in England. It forms part of a World Heritage Site. It is the cathedral of the Archbishop of Canterbury, currently Justin Welby, leader of the ...

after Becket resisted a botched attempt to arrest him. Within Christian Europe Henry was widely considered complicit in Becket's death. The opinion of this transgression against the church made Henry a pariah, so in penance he walked barefoot into Canterbury Cathedral where he was scourged by monks.

In 1171, Henry invaded Ireland to assert his overlordship following alarm at the success of knights that he had allowed to recruit soldiers in England and Wales, who had assumed the role of colonisers and accrued autonomous power, including Strongbow. Pope Adrian IV

Pope Adrian IV ( la, Adrianus IV; born Nicholas Breakspear (or Brekespear); 1 September 1159, also Hadrian IV), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 4 December 1154 to his death in 1159. He is the only Englishman t ...

had given Henry a papal blessing

In religion, a blessing (also used to refer to bestowing of such) is the impartation of something with grace, holiness, spiritual redemption, or divine will.

Etymology and Germanic paganism

The modern English language term ''bless'' likely ...

to expand his power into Ireland to reform the Irish church. Originally, this would have allowed some territory to be granted to Henry's brother, William, but other matters had distracted Henry and William was now dead. Instead, Henry's designs were made plain when he gave the lordship of Ireland to his youngest son, John.

In 1172, Henry II tried to give his landless youngest son John a wedding gift of the three castles of Chinon

Chinon () is a commune in the Indre-et-Loire department, Centre-Val de Loire, France.

The traditional province around Chinon, Touraine, became a favorite resort of French kings and their nobles beginning in the late 15th and early 16th centurie ...

, Loudun

Loudun (; ; Poitevin: ''Loudin'') is a commune in the Vienne department and the region of Nouvelle-Aquitaine, western France.

It is located south of the town of Chinon and 25 km to the east of the town Thouars. The area south of Loudun i ...

and Mirebeau

Mirebeau (; Poitevin: ''Mirebea'') is a commune in the Vienne department, in the region of Nouvelle-Aquitaine, western France.

History

Fulk Nerra (970-1040), Count of Anjou conquered Mirebeau and built a castle there. His son, Geoffrey of An ...

. This angered the 18-year-old Young King, who had yet to receive any lands from his father, and prompted a rebellion

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

by Henry II's wife and three eldest sons. Louis VII

Louis VII (1120 – 18 September 1180), called the Younger, or the Young (french: link=no, le Jeune), was King of the Franks from 1137 to 1180. He was the son and successor of King Louis VI (hence the epithet "the Young") and married Duchess ...

supported the rebellion to destabilise Henry II. William the Lion

William the Lion, sometimes styled William I and also known by the nickname Garbh, "the Rough"''Uilleam Garbh''; e.g. Annals of Ulster, s.a. 1214.6; Annals of Loch Cé, s.a. 1213.10. ( 1142 – 4 December 1214), reigned as King of Scots from 11 ...

and other subjects of Henry II also joined the revolt and it took 18 months for Henry to force the rebels to submit to his authority. In Le Mans in 1182, Henry II gathered his children to plan a partible inheritance

Partible inheritance is a system of inheritance in which property is apportioned among heirs. It contrasts in particular with primogeniture, which was common in feudal society and requires that the whole or most of the inheritance passes to the el ...

in which his eldest son (also called Henry) would inherit England, Normandy and Anjou; Richard

Richard is a male given name. It originates, via Old French, from Old Frankish and is a compound of the words descending from Proto-Germanic ''*rīk-'' 'ruler, leader, king' and ''*hardu-'' 'strong, brave, hardy', and it therefore means 'stro ...

the Duchy of Aquitaine; Geoffrey Brittany, and John Ireland. This degenerated into further conflict. The younger Henry rebelled again before he died of dysentery

Dysentery (UK pronunciation: , US: ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications ...

and, in 1186, Geoffrey died after a tournament accident. In 1189, Richard and Philip II of France

Philip II (21 August 1165 – 14 July 1223), byname Philip Augustus (french: Philippe Auguste), was King of France from 1180 to 1223. His predecessors had been known as kings of the Franks, but from 1190 onward, Philip became the first French m ...

took advantage of Henry's failing health and forced him to accept humiliating peace terms, including naming Richard as his sole heir. Two days later, the old king died, defeated and miserable in the knowledge that even his favoured son John had rebelled. This fate was seen as the price he paid for the murder of Beckett.

Decline

On the day of Richard's English coronation, there was a mass slaughter of Jews, described by

On the day of Richard's English coronation, there was a mass slaughter of Jews, described by Richard of Devizes

Richard of Devizes (fl. late 12th century), English chronicler, was a monk of St Swithin's house at Winchester.

His birthplace is probably indicated by his surname, Devizes in Wiltshire, but not much is known about his life. He is credited by Ba ...

as a "holocaust". After his coronation, Richard put the Angevin Empire's affairs in order before joining the Third Crusade

The Third Crusade (1189–1192) was an attempt by three European monarchs of Western Christianity ( Philip II of France, Richard I of England and Frederick I, Holy Roman Emperor) to reconquer the Holy Land following the capture of Jerusalem by ...

to the Middle East in early 1190. Opinions of Richard by his contemporaries varied. He had rejected and humiliated the king of France's sister; deposed the king of Cyprus and sold the island; insulted and refused to give spoils from the Third Crusade to Leopold V, Duke of Austria

Leopold V (1157 – 31 December 1194), known as the Virtuous (german: der Tugendhafte) was a member of the House of Babenberg who reigned as Duke of Austria from 1177 and Duke of Styria from 1192 until his death. The Georgenberg Pact resulted in L ...

, and allegedly arranged the assassination of Conrad of Montferrat

Conrad of Montferrat ( Italian: ''Corrado del Monferrato''; Piedmontese: ''Conrà ëd Monfrà'') (died 28 April 1192) was a nobleman, one of the major participants in the Third Crusade. He was the ''de facto'' King of Jerusalem (as Conrad I) by ...

. His cruelty was exemplified by the massacre of 2,600 prisoners in Acre. However, Richard was respected for his military leadership and courtly manners. Despite victories in the Third Crusade

The Third Crusade (1189–1192) was an attempt by three European monarchs of Western Christianity ( Philip II of France, Richard I of England and Frederick I, Holy Roman Emperor) to reconquer the Holy Land following the capture of Jerusalem by ...

he failed to capture Jerusalem, retreating from the Holy Land with a small band of followers.

Richard was captured by Leopold on his return journey. He was transferred to Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor

Henry VI (German: ''Heinrich VI.''; November 1165 – 28 September 1197), a member of the Hohenstaufen dynasty, was King of Germany ( King of the Romans) from 1169 and Holy Roman Emperor from 1191 until his death. From 1194 he was also King of ...

, and a 25-percent tax on goods and income was required to pay his 150,000-mark

Mark may refer to:

Currency

* Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark, the currency of Bosnia and Herzegovina

* East German mark, the currency of the German Democratic Republic

* Estonian mark, the currency of Estonia between 1918 and 1927

* Finn ...

ransom. Philip II of France had overrun Normandy, while John of England

John (24 December 1166 – 19 October 1216) was King of England from 1199 until his death in 1216. He lost the Duchy of Normandy and most of his other French lands to King Philip II of France, resulting in the collapse of the Angevin ...

controlled much of Richard's remaining lands. However, when Richard returned to England he forgave John and re-established his control. Leaving England permanently in 1194, Richard fought Philip for five years for the return of holdings seized during his incarceration. On the brink of victory, he was wounded by an arrow during the siege of Château de Châlus-Chabrol

The Château de Châlus-Chabrol ( Occitan Limousin : ''Chasteu de Chasluç-Chabròl'') is a castle in the ''commune'' of Châlus in the ''département'' of Haute-Vienne, France.

The castle dominates the town of Châlus. It consists today of an ...

and died ten days later.

His failure to produce an heir caused a succession crisis. Anjou, Brittany, Maine and Touraine chose Richard's nephew Arthur

Arthur is a common male given name of Brythonic origin. Its popularity derives from it being the name of the legendary hero King Arthur. The etymology is disputed. It may derive from the Celtic ''Artos'' meaning “Bear”. Another theory, more wi ...

as heir, while John succeeded in England and Normandy. Philip II of France again destabilised the Plantagenet territories on the European mainland, supporting his vassal Arthur's claim to the English crown. Eleanor supported her son John, who was victorious at the Battle of Mirebeau

The Battle of Mirebeau was a battle in 1202 between the House of Lusignan- Breton alliance and the Kingdom of England. King John of England successfully smashed the Lusignan army by surprise.

Background

After Richard I's death on 6 April ...

and captured the rebel leadership.

Arthur was murdered (allegedly by John), and his sister Eleanor

Eleanor () is a feminine given name, originally from an Old French adaptation of the Old Provençal name ''Aliénor''. It is the name of a number of women of royalty and nobility in western Europe during the High Middle Ages.

The name was intro ...

would spend the rest of her life in captivity. John's behaviour drove a number of French barons to side with Philip, and the resulting rebellions by Norman and Angevin barons ended John's control of his continental possessions—the ''de facto'' end of the Angevin Empire, although Henry III would maintain his claim until 1259.

After re-establishing his authority in England, John planned to retake Normandy and Anjou by drawing the French from Paris while another army (under Otto IV, Holy Roman Emperor

Otto IV (1175 – 19 May 1218) was the Holy Roman Emperor from 1209 until his death in 1218.

Otto spent most of his early life in England and France. He was a follower of his uncle Richard the Lionheart, who made him Count of Poitou in 11 ...

) attacked from the north. However, his allies were defeated at the Battle of Bouvines

The Battle of Bouvines was fought on 27 July 1214 near the town of Bouvines in the County of Flanders. It was the concluding battle of the Anglo-French War of 1213–1214. Although estimates on the number of troops vary considerably among mod ...

in one of the most decisive battles in French history. John's nephew Otto retreated and was soon overthrown, with John agreeing to a five-year truce. Philip's victory was crucial to the political order in England and France, and the battle was instrumental in establishing absolute monarchy in France

Absolute monarchy in France slowly emerged in the 16th century and became firmly established during the 17th century. Absolute monarchy is a variation of the governmental form of monarchy in which the monarch holds supreme authority and where th ...

.

John's French defeats weakened his position in England. The rebellion of his English vassals resulted in ''

John's French defeats weakened his position in England. The rebellion of his English vassals resulted in ''Magna Carta

(Medieval Latin for "Great Charter of Freedoms"), commonly called (also ''Magna Charta''; "Great Charter"), is a royal charter of rights agreed to by King John of England at Runnymede, near Windsor, on 15 June 1215. First drafted by t ...

'', which limited royal power and established common law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omniprese ...

. This would form the basis of every constitutional battle of the 13th and 14th centuries. The barons and the crown failed to abide by ''Magna Carta'', leading to the First Barons' War

The First Barons' War (1215–1217) was a civil war in the Kingdom of England in which a group of rebellious major landowners (commonly referred to as barons) led by Robert Fitzwalter waged war against King John of England. The conflict resulte ...

when rebel barons provoked an invasion by Prince Louis. Many historians use John's death and William Marshall's appointment as protector of nine-year-old Henry III to mark the end of the Angevin period and the beginning of the Plantagenet dynasty. Marshall won the war with victories at Lincoln

Lincoln most commonly refers to:

* Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865), the sixteenth president of the United States

* Lincoln, England, cathedral city and county town of Lincolnshire, England

* Lincoln, Nebraska, the capital of Nebraska, U.S.

* Lincol ...

and Dover

Dover () is a town and major ferry port in Kent, South East England. It faces France across the Strait of Dover, the narrowest part of the English Channel at from Cap Gris Nez in France. It lies south-east of Canterbury and east of Maids ...

in 1217, leading to the Treaty of Lambeth

The Treaty of Lambeth of 1217, also known as the Treaty of Kingston to distinguish it from the Treaty of Lambeth of 1212, was a peace treaty signed by Louis of France in September 1217 ending the campaign known as the First Barons' War to uphold ...

in which Louis renounced his claims. In victory, the Marshal Protectorate reissued ''Magna Carta'' as the basis of future government.

Legacy

House of Plantagenet

Historians use the period of Prince Louis's invasion to mark the end of the Angevin period and the beginning of thePlantagenet

The House of Plantagenet () was a royal house which originated from the lands of Anjou in France. The family held the English throne from 1154 (with the accession of Henry II at the end of the Anarchy) to 1485, when Richard III died in b ...

dynasty. The outcome of the military situation was uncertain at John's death; William Marshall saved the dynasty, forcing Louis to renounce his claim with a military victory. However, Philip had captured all the Angevin possessions in France except Gascony

Gascony (; french: Gascogne ; oc, Gasconha ; eu, Gaskoinia) was a province of the southwestern Kingdom of France that succeeded the Duchy of Gascony (602–1453). From the 17th century until the French Revolution (1789–1799), it was part ...

. This collapse had several causes, including long-term changes in economic power, growing cultural differences between England and Normandy and (in particular) the fragile, familial nature of Henry's empire. Henry III continued his attempts to reclaim Normandy and Anjou until 1259, but John's continental losses and the consequent growth of Capetian power during the 13th century marked a "turning point in European history".

Richard of York

Richard of York, 3rd Duke of York (21 September 1411 – 30 December 1460), also named Richard Plantagenet, was a leading English magnate and claimant to the throne during the Wars of the Roses. He was a member of the ruling House of Plantage ...

adopted "Plantagenet" as a family name for himself and his descendants during the 15th century. ''Plantegenest'' (or ''Plante Genest'') was Geoffrey's nickname, and his emblem may have been the common broom

''Cytisus scoparius'' ( syn. ''Sarothamnus scoparius''), the common broom or Scotch broom, is a deciduous leguminous shrub native to western and central Europe. In Britain and Ireland, the standard name is broom; this name is also used for other ...

(''planta genista'' in medieval Latin). It is uncertain why Richard chose the name, but it emphasised Richard's hierarchal status as Geoffrey's (and six English kings') patrilineal descendant during the Wars of the Roses

The Wars of the Roses (1455–1487), known at the time and for more than a century after as the Civil Wars, were a series of civil wars fought over control of the throne of England, English throne in the mid-to-late fifteenth century. These w ...

. The retrospective use of the name for Geoffrey's male descendants was popular during the Tudor period

The Tudor period occurred between 1485 and 1603 in England and Wales and includes the Elizabethan period during the reign of Elizabeth I until 1603. The Tudor period coincides with the dynasty of the House of Tudor in England that began wit ...

, perhaps encouraged by the added legitimacy it gave Richard's great-grandson Henry VIII of England

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

.

Descent

Through John, descent from the Angevins (legitimate and illegitimate) is widespread, and includes all subsequent monarchs of England and the United Kingdom. He had five legitimate children with Isabella: * Henry III – king of England for most of the 13th century *Richard

Richard is a male given name. It originates, via Old French, from Old Frankish and is a compound of the words descending from Proto-Germanic ''*rīk-'' 'ruler, leader, king' and ''*hardu-'' 'strong, brave, hardy', and it therefore means 'stro ...

– a noted European leader and King of the Romans

King of the Romans ( la, Rex Romanorum; german: König der Römer) was the title used by the king of Germany following his election by the princes from the reign of Henry II (1002–1024) onward.

The title originally referred to any German k ...

in the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 unt ...

* Joan Joan may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Joan (given name), including a list of women, men and fictional characters

*: Joan of Arc, a French military heroine

*Joan (surname)

Weather events

*Tropical Storm Joan (disambiguation), multip ...

– married Alexander II of Scotland

Alexander II ( Medieval Gaelic: '; Modern Gaelic: '; 24 August 1198 – 6 July 1249) was King of Scotland from 1214 until his death. He concluded the Treaty of York (1237) which defined the boundary between England and Scotland, virtually un ...

, becoming his queen consort.

* Isabella – married the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II.

* Eleanor

Eleanor () is a feminine given name, originally from an Old French adaptation of the Old Provençal name ''Aliénor''. It is the name of a number of women of royalty and nobility in western Europe during the High Middle Ages.

The name was intro ...

– married William Marshal's son (also called William

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Engl ...

) and, later, English rebel Simon de Montfort

Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester ( – 4 August 1265), later sometimes referred to as Simon V de Montfort to distinguish him from his namesake relatives, was a nobleman of French origin and a member of the English peerage, who led the ...

.

John also had illegitimate children with a number of mistresses, including nine sons—Richard

Richard is a male given name. It originates, via Old French, from Old Frankish and is a compound of the words descending from Proto-Germanic ''*rīk-'' 'ruler, leader, king' and ''*hardu-'' 'strong, brave, hardy', and it therefore means 'stro ...

, Oliver, John, Geoffrey, Henry, Osbert Gifford, Eudes, Bartholomew and (probably) Philip—and three daughters—Joan Joan may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Joan (given name), including a list of women, men and fictional characters

*: Joan of Arc, a French military heroine

*Joan (surname)

Weather events

*Tropical Storm Joan (disambiguation), multip ...

, Maud and (probably) Isabel. Of these, Joan was the best known, since she married Prince Llywelyn the Great

Llywelyn the Great ( cy, Llywelyn Fawr, ; full name Llywelyn mab Iorwerth; c. 117311 April 1240) was a King of Gwynedd in north Wales and eventually " Prince of the Welsh" (in 1228) and "Prince of Wales" (in 1240). By a combination of war and ...

of Wales.

Contemporary opinion

The chroniclerGerald of Wales

Gerald of Wales ( la, Giraldus Cambrensis; cy, Gerallt Gymro; french: Gerald de Barri; ) was a Cambro-Norman priest and historian. As a royal clerk to the king and two archbishops, he travelled widely and wrote extensively. He studied and taugh ...

borrowed elements of the Melusine

Mélusine () or Melusina is a figure of European folklore, a female spirit of fresh water in a holy well or river. She is usually depicted as a woman who is a serpent or fish from the waist down (much like a lamia or a mermaid). She is als ...

legend to give the Angevins a demonic origin, and the kings were said to tell jokes about the stories.

Henry was an unpopular king, and few grieved his death; William of Newburgh wrote during the 1190s, "In his own time he was hated by almost everyone". He was widely criticised by contemporaries, even in his own court. Henry's son Richard's contemporary image was more nuanced, since he was the first king who was also a

Henry was an unpopular king, and few grieved his death; William of Newburgh wrote during the 1190s, "In his own time he was hated by almost everyone". He was widely criticised by contemporaries, even in his own court. Henry's son Richard's contemporary image was more nuanced, since he was the first king who was also a knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the Christian denomination, church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood ...

. Known as a valiant, competent and generous military leader, he was criticised by chroniclers for taxing the clergy for the Crusade and his ransom; clergy were usually exempt from taxes.

Chroniclers Richard of Devizes

Richard of Devizes (fl. late 12th century), English chronicler, was a monk of St Swithin's house at Winchester.

His birthplace is probably indicated by his surname, Devizes in Wiltshire, but not much is known about his life. He is credited by Ba ...

, William of Newburgh

William of Newburgh or Newbury ( la, Guilelmus Neubrigensis, ''Wilhelmus Neubrigensis'', or ''Willelmus de Novoburgo''. 1136 – 1198), also known as William Parvus, was a 12th-century English historian and Augustinian canon of Anglo-Saxon de ...

, Roger of Hoveden

Roger is a given name, usually masculine, and a surname. The given name is derived from the Old French personal names ' and '. These names are of Germanic origin, derived from the elements ', ''χrōþi'' ("fame", "renown", "honour") and ', ' ( ...

and Ralph de Diceto

Ralph de Diceto (or Ralph of Diss; c. 1120c. 1202) was archdeacon of Middlesex, dean of St Paul's Cathedral (from c. 1180), and author of two chronicles, the ''Abbreviationes chronicorum'' and the ''Ymagines historiarum''.

Early career

Ralph is ...

were generally unsympathetic to John's behaviour under Richard, but more tolerant of the earliest years of John's reign. Accounts of the middle and later years of his reign are limited to Gervase of Canterbury

Gervase of Canterbury (; Latin: Gervasus Cantuariensis or Gervasius Dorobornensis) (c. 1141 – c. 1210) was an English chronicler.

Life

If Gervase's brother Thomas, who like himself was a monk of Christ Church, Canterbury, was Thomas of ...

and Ralph of Coggeshall

Ralph of Coggeshall (died after 1227), English chronicler, was at first a monk and afterwards sixth abbot (1207–1218) of Coggeshall Abbey, an Essex foundation of the Cistercian order.

Chronicon Anglicanum

Ralph himself tells us these facts; ...

, neither of whom were satisfied with John's performance as king. His later negative reputation was established by two chroniclers writing after the king's death: Roger of Wendover

Roger of Wendover (died 6 May 1236), probably a native of Wendover in Buckinghamshire, was an English chronicler of the 13th century.

At an uncertain date he became a monk at St Albans Abbey; afterwards he was appointed prior of the cell o ...

and Matthew Paris

Matthew Paris, also known as Matthew of Paris ( la, Matthæus Parisiensis, lit=Matthew the Parisian; c. 1200 – 1259), was an English Benedictine monk, chronicler, artist in illuminated manuscripts and cartographer, based at St Albans Abbey ...

. The latter claimed that John attempted to convert to Islam, but this is not believed by modern historians.

Constitutional impact

Many of the changes Henry introduced during his rule had long-term consequences. His legal innovations form part of the basis forEnglish law

English law is the common law legal system of England and Wales, comprising mainly criminal law and civil law, each branch having its own courts and procedures.

Principal elements of English law

Although the common law has, historically, b ...

, with the Exchequer of Pleas a forerunner of the Common Bench

The Court of Common Pleas, or Common Bench, was a common law court in the English legal system that covered "common pleas"; actions between subject and subject, which did not concern the king. Created in the late 12th to early 13th century af ...

at Westminster. Henry's itinerant justices also influenced his contemporaries' legal reforms: Philip Augustus's creation of itinerant ''bailli'', for example, drew on Henry's model. Henry's intervention in Brittany, Wales and Scotland had a significant long-term impact on the development of their societies and governments. John's reign, despite its flaws, and his signing of ''Magna Carta'', were seen by Whig historians as positive steps in the constitutional development of England and part of a progressive and universalist course of political and economic development in medieval England. Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

said, " en the long tally is added, it will be seen that the British nation and the English-speaking world owe far more to the vices of John than to the labours of virtuous sovereigns". ''Magna Carta'' was reissued by the Marshal Protectorate and later as a foundation of future government.

Architecture, language and literature

There was no distinct Angevin or Plantagenet culture that would distinguish or set them apart from their neighbours in this period.Robert of Torigni

Robert of Torigni (also known as Roburtus de Monte) (c. 1110–1186) was a Norman monk, prior, abbot and twelfth century chronicler.

Religious life

Robert was born at Torigni-sur-Vire, Normandy c. 1110 most probably to an aristocratic family but ...

recorded that Henry built or renovated castles throughout his domain in Normandy, England, Aquitaine, Anjou, Maine and Tourraine. However, this patronage had no distinctive style except in the use of circular or octagonal kitchens of the Fontevraud type. Similarly, amongst the multiple vernacularsFrench, English and Occitanthere was not a unifying literature. French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

was the lingua franca

A lingua franca (; ; for plurals see ), also known as a bridge language, common language, trade language, auxiliary language, vehicular language, or link language, is a language systematically used to make communication possible between groups ...

of the secular elite and Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

or the church.

The Angevins were closely associated with the Fontevraud Abbey in Anjou. Henry's aunt

An aunt is a woman who is a sibling of a parent or married to a sibling of a parent. Aunts who are related by birth are second-degree relatives. Known alternate terms include auntie or aunty. Children in other cultures and families may re ...

was Abbess

An abbess (Latin: ''abbatissa''), also known as a mother superior, is the female superior of a community of Catholic nuns in an abbey.

Description

In the Catholic Church (both the Latin Church and Eastern Catholic), Eastern Orthodox, Copt ...

, Eleanor retired there to be a nun and the abbey was originally the site of his grave and those of Eleanor, Richard, his daughter Joan Joan may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Joan (given name), including a list of women, men and fictional characters

*: Joan of Arc, a French military heroine

*Joan (surname)

Weather events

*Tropical Storm Joan (disambiguation), multip ...

, grandson Raymond VII of Toulouse

Raymond VII (July 1197 – 27 September 1249) was Count of Toulouse, Duke of Narbonne and Marquis of Provence from 1222 until his death.

Family and marriages

Raymond was born at the Château de Beaucaire, the son of Raymond VI of Toulouse ...

and John's wifeIsabella of Angoulême

Isabella (french: Isabelle, ; c. 1186/ 1188 – 4 June 1246) was Queen of England from 1200 to 1216 as the second wife of King John, Countess of Angoulême in her own right from 1202 until her death in 1246, and Countess of La Marche from 122 ...

. Henry III visited the abbey in 1254 to reorder these tombs and requested that his heart be buried with them.

Historiography

According to historianJohn Gillingham

John Bennett Gillingham (born 3 August 1940) is Emeritus Professor of Medieval History at the London School of Economics and Political Science. On 19 July 2007 he was elected a Fellow of the British Academy.

Gillingham is renowned as an expert on ...

, Henry and his reign have attracted historians for many years and Richard (whose reputation has "fluctuated wildly") is remembered largely because of his military exploits. Steven Runciman

Sir James Cochran Stevenson Runciman ( – ), known as Steven Runciman, was an English historian best known for his three-volume '' A History of the Crusades'' (1951–54).

He was a strong admirer of the Byzantine Empire. His history's negativ ...

, in the third volume of the ''History of the Crusades'', wrote: "He was a bad son, a bad husband, and a bad king, but a gallant and splendid soldier."

Eighteenth-century historian David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; 7 May 1711 NS (26 April 1711 OS) – 25 August 1776) Cranston, Maurice, and Thomas Edmund Jessop. 2020 999br>David Hume" '' Encyclopædia Britannica''. Retrieved 18 May 2020. was a Scottish Enlightenment ph ...

wrote that the Angevins were pivotal in creating a genuinely English monarchy and, ultimately, a unified Britain. Interpretations of ''Magna Carta'' and the role of the rebel barons in 1215 have been revised; although the charter's symbolic, constitutional value for later generations is unquestionable, for most historians it is a failed peace agreement between factions. John's opposition to the papacy and his promotion of royal rights and prerogatives won favour from 16th-century Tudors. John Foxe

John Foxe (1516/1517 – 18 April 1587), an English historian and martyrologist, was the author of '' Actes and Monuments'' (otherwise ''Foxe's Book of Martyrs''), telling of Christian martyrs throughout Western history, but particularly the s ...

, William Tyndale

William Tyndale (; sometimes spelled ''Tynsdale'', ''Tindall'', ''Tindill'', ''Tyndall''; – ) was an English biblical scholar and linguist who became a leading figure in the Protestant Reformation in the years leading up to his execu ...

and Robert Barnes viewed John as an early Protestant hero, and Foxe included the king in his ''Book of Martyrs

The ''Actes and Monuments'' (full title: ''Actes and Monuments of these Latter and Perillous Days, Touching Matters of the Church''), popularly known as Foxe's Book of Martyrs, is a work of Protestant history and martyrology by Protestant Engl ...

''. John Speed

John Speed (1551 or 1552 – 28 July 1629) was an English cartographer, chronologer and historian of Cheshire origins.S. Bendall, 'Speed, John (1551/2–1629), historian and cartographer', ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (OUP 2004/ ...

's 1632 ''Historie of Great Britaine'' praised John's "great renown" as king, blaming biased medieval chroniclers for the king's poor reputation. Similarly, later Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

historians view Henry's role in Thomas Becket's death and his disputes with the French as worthy of praise. Similarly, increased access to contemporary records during the late Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwa ...

led to a recognition of Henry's contributions to the evolution of English law and the exchequer. William Stubbs

William Stubbs (21 June 182522 April 1901) was an English historian and Anglican bishop. He was Regius Professor of Modern History at the University of Oxford between 1866 and 1884. He was Bishop of Chester from 1884 to 1889 and Bishop of O ...

called Henry a "legislator king" because of his responsibility for major, long-term reforms in England; in contrast, Richard was "a bad son, a bad husband, a selfish ruler, and a vicious man".

The growth of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

led historian Kate Norgate to begin detailed research into Henry's continental possessions and create the term "Angevin Empire" during the 1880s. However, 20th-century historians challenged many of these conclusions. During the 1950s, Jacques Boussard, John Jolliffe and others focused on the nature of Henry's "empire"; French scholars, in particular, analysed the mechanics of royal power during this period. Anglocentric aspects of many histories of Henry's reign were challenged beginning in the 1980s, with efforts to unite British and French historical analyses of the period. Detailed study of Henry's written records has cast doubt on earlier interpretations; Robert Eyton's 1878 volume (tracing Henry's itinerary by deductions from pipe rolls), for example, has been criticised for not acknowledging uncertainty. Although many of Henry's royal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, b ...

s have been identified, their interpretation, the financial information in the pipe rolls and broad economic data from his reign has proven more challenging than once thought. Significant gaps in the historical analysis of Henry remain, particularly about his rule in Anjou and the south of France.

Interest in the morality of historical figures and scholars waxed during the Victorian period, leading to increased criticism of Henry's behaviour and Becket's death. Historians relied on the judgement of chroniclers to focus on John's ethos. Norgate wrote that John's downfall was due not to his military failures but his "almost superhuman wickedness", and James Ramsay blamed John's family background and innate cruelty for his downfall.

Richard's sexuality has been controversial since the 1940s, when John Harvey challenged what he saw as "the conspiracy of silence" surrounding the king's homosexuality

Homosexuality is Romance (love), romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or Human sexual activity, sexual behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romant ...

with chronicles of Richard's behaviour, two public confessions, penances and childless marriage. Opinion remains divided, with Gillingham arguing against Richard's homosexuality and Jean Flori acknowledging its possibility.

According to recent biographers Ralph Turner and Lewis Warren, although John was an unsuccessful monarch, his failings were exaggerated by 12th- and 13th-century chroniclers. Jim Bradbury echoes the contemporary consensus that John was a "hard-working administrator, an able man, an able general" with, as Turner suggests, "distasteful, even dangerous personality traits". John Gillingham (author of a biography of Richard I) agrees and judges John to be a less-effective general than Turner and Warren do. Bradbury takes a middle view, suggesting that modern historians have been overly lenient in evaluating John's flaws. Popular historian Frank McLynn

Francis James McLynn FRHistS FRGS (born 29 August 1941), known as Frank McLynn, is a British author, biographer, historian and journalist. He is noted for critically acclaimed biographies of Napoleon Bonaparte, Robert Louis Stevenson, Carl Jung, ...

wrote that the king's modern reputation amongst historians is "bizarre" and, as a monarch, John "fails almost all those eststhat can be legitimately set".

In popular culture

Henry II appears as a fictionalised character in several modern plays and films. The king is a central character inJames Goldman

James Goldman (June 30, 1927 – October 28, 1998) was an American playwright and screenwriter. He won an Academy Award for his screenplay '' The Lion in Winter'' (1968). His younger brother was novelist and screenwriter William Goldman.

Biog ...

's play '' The Lion in Winter'' (1966), depicting an imaginary encounter between Henry's family and Philip Augustus over Christmas 1183 at Chinon

Chinon () is a commune in the Indre-et-Loire department, Centre-Val de Loire, France.

The traditional province around Chinon, Touraine, became a favorite resort of French kings and their nobles beginning in the late 15th and early 16th centurie ...

. Philip's strong character contrasts with John, an "effete weakling". In the 1968 film

The year 1968 in film involved some significant events, with the release of Stanley Kubrick's '' 2001: A Space Odyssey'', as well as two highly successful musical films, '' Funny Girl'' and ''Oliver!'', the former earning Barbra Streisand the Ac ...

, Henry is a sacrilegious, fiery and determined king. Henry also appears in Jean Anouilh

Jean Marie Lucien Pierre Anouilh (; 23 June 1910 – 3 October 1987) was a French dramatist whose career spanned five decades. Though his work ranged from high drama to absurdist farce, Anouilh is best known for his 1944 play ''Antigone'', an a ...

's play ''Becket

''Becket or The Honour of God'' (french: Becket ou l'honneur de Dieu) is a 1959 play written in French by Jean Anouilh. It is a depiction of the conflict between Thomas Becket and King Henry II of England leading to Becket's assassination in 117 ...

'', which was filmed in 1964. The Becket conflict is the basis for T. S. Eliot's play '' Murder in the Cathedral'', an exploration of Becket's death and Eliot's religious interpretation of it.

During the Tudor period, popular representations of John emerged. He appeared as a "proto-Protestant martyr" in the anonymous play ''The Troublesome Reign of King John

''The Troublesome Reign of John, King of England'', commonly called ''The Troublesome Reign of King John'' (c. 1589) is an Elizabethan history play, probably by George Peele, that is generally accepted by scholars as the source and model that Wi ...

'' and John Bale

John Bale (21 November 1495 – November 1563) was an English churchman, historian and controversialist, and Bishop of Ossory in Ireland. He wrote the oldest known historical verse drama in English (on the subject of King John), and developed ...

's morality play '' Kynge Johan'', in which John attempts to save England from the "evil agents of the Roman Church". Shakespeare's anti-Catholic '' King John'' draws on ''The Troublesome Reign'', offering a "balanced, dual view of a complex monarch as both a proto-Protestant victim of Rome's machinations and as a weak, selfishly motivated ruler". Anthony Munday

Anthony Munday (or Monday) (1560?10 August 1633) was an English playwright and miscellaneous writer. He was baptized on 13 October 1560 in St Gregory by St Paul's, London, and was the son of Christopher Munday, a stationer, and Jane Munday. He ...

's plays '' The Downfall and The Death of Robert Earl of Huntington'' demonstrate many of John's negative traits, but approve of the king's stand against the Roman Catholic Church.

Richard is the subject of two operas: In 1719, George Frideric Handel

George Frideric (or Frederick) Handel (; baptised , ; 23 February 1685 – 14 April 1759) was a German-British Baroque music, Baroque composer well known for his opera#Baroque era, operas, oratorios, anthems, concerto grosso, concerti grossi, ...

used Richard's invasion of Cyprus as the plot for ''Riccardo Primo

''Riccardo primo, re d'Inghilterra'' ("Richard the First, King of England", HWV 23) is an opera seria in three acts written by George Frideric Handel for the Royal Academy of Music (1719) . The Italian-language libretto was by Paolo Antonio Ro ...

'', and, in 1784, André Grétry

André Ernest Modeste Grétry (; baptised 11 February 1741; died 24 September 1813) was a

composer from the Prince-Bishopric of Liège (present-day Belgium), who worked from 1767 onwards in France and took French nationality. He is most famous ...

wrote '' Richard Coeur-de-lion''.

Robin Hood

The earliest ballads ofRobin Hood

Robin Hood is a legendary heroic outlaw originally depicted in English folklore and subsequently featured in literature and film. According to legend, he was a highly skilled archer and swordsman. In some versions of the legend, he is dep ...

such as those compiled in ''A Gest of Robyn Hode

''A Gest of Robyn Hode'' (also known as ''A Lyttell Geste of Robyn Hode'', and hereafter referred to as ''Gest'') is one of the earliest surviving texts of the Robin Hood tales. ''Gest'' (which meant tale or adventure) is a compilation of vari ...

'' associated the character with a king named "Edward" and the setting is usually attributed by scholars to either the 13th or the 14th century. As the historian J.C. Holt notes at some time around the 16th century, tales of Robin Hood started to mention him as a contemporary and supporter of Richard, Robin being driven to outlawry during John's misrule, while in the narratives Richard was largely absent, away at the Third Crusade. Plays such as Robert Davenport Robert Davenport may refer to:

* Robert Davenport (dramatist) (fl. 1623–1639), English dramatist

* Robert Davenport (Australian politician)

Robert Davenport (1816 – 3 September 1896) was a pioneer and politician in the early days of the Co ...

's '' King John and Matilda'' further developed the Elizabethan

The Elizabethan era is the epoch in the Tudor period of the history of England during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603). Historians often depict it as the golden age in English history. The symbol of Britannia (a female personific ...

works in the mid-17th century, focussing on John's tyranny and transferring the role of Protestant champion to the barons. Graham Tulloch noted that unfavourable 19th-century fictionalised depictions of John were influenced by Sir Walter Scott