Ancient Egyptian pottery includes all objects of fired

clay

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4).

Clays develop plasticity when wet, due to a molecular film of water surrounding the clay pa ...

from

ancient Egypt. First and foremost,

ceramic

A ceramic is any of the various hard, brittle, heat-resistant and corrosion-resistant materials made by shaping and then firing an inorganic, nonmetallic material, such as clay, at a high temperature. Common examples are earthenware, porcelain, ...

s served as household wares for the storage, preparation, transport, and consumption of food, drink, and raw materials. Such items include beer and wine mugs and water jugs, but also bread moulds, fire pits, lamps, and stands for holding round vessels, which were all commonly used in the Egyptian household. Other types of

pottery

Pottery is the process and the products of forming vessels and other objects with clay and other ceramic materials, which are fired at high temperatures to give them a hard and durable form. Major types include earthenware, stoneware and ...

served ritual purposes. Ceramics are often found as

grave goods

Grave goods, in archaeology and anthropology, are the items buried along with the body.

They are usually personal possessions, supplies to smooth the deceased's journey into the afterlife or offerings to the gods. Grave goods may be classed as a ...

.

Specialists in ancient Egyptian pottery draw a fundamental distinction between ceramics made of

Nile clay and those made of

marl

Marl is an earthy material rich in carbonate minerals, clays, and silt. When hardened into rock, this becomes marlstone. It is formed in marine or freshwater environments, often through the activities of algae.

Marl makes up the lower part ...

clay, based on

chemical

A chemical substance is a form of matter having constant chemical composition and characteristic properties. Some references add that chemical substance cannot be separated into its constituent elements by physical separation methods, i.e., w ...

and

mineralogical

Mineralogy is a subject of geology specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure, and physical (including optical) properties of minerals and mineralized artifacts. Specific studies within mineralogy include the p ...

composition and ceramic properties. Nile clay is the result of

eroded material in the

Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

n mountains, which was transported into Egypt by the Nile. This clay has deposited on the banks of the Nile in Egypt since the

Late Pleistocene

The Late Pleistocene is an unofficial age in the international geologic timescale in chronostratigraphy, also known as Upper Pleistocene from a stratigraphic perspective. It is intended to be the fourth division of the Pleistocene Epoch withi ...

by the

flooding of the Nile

The flooding of the Nile has been an important natural cycle in Egypt since ancient times. It is celebrated by Egyptians as an annual holiday for two weeks starting August 15, known as ''Wafaa El-Nil''. It is also celebrated in the Coptic Church ...

. Marl clay is a yellow-white stone which occurs in

limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms w ...

deposits. These deposits were created in the

Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological Epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fina ...

, when the primordial waters of the Nile and its tributaries brought sediment into Egypt and deposited in on what was then the desert edge.

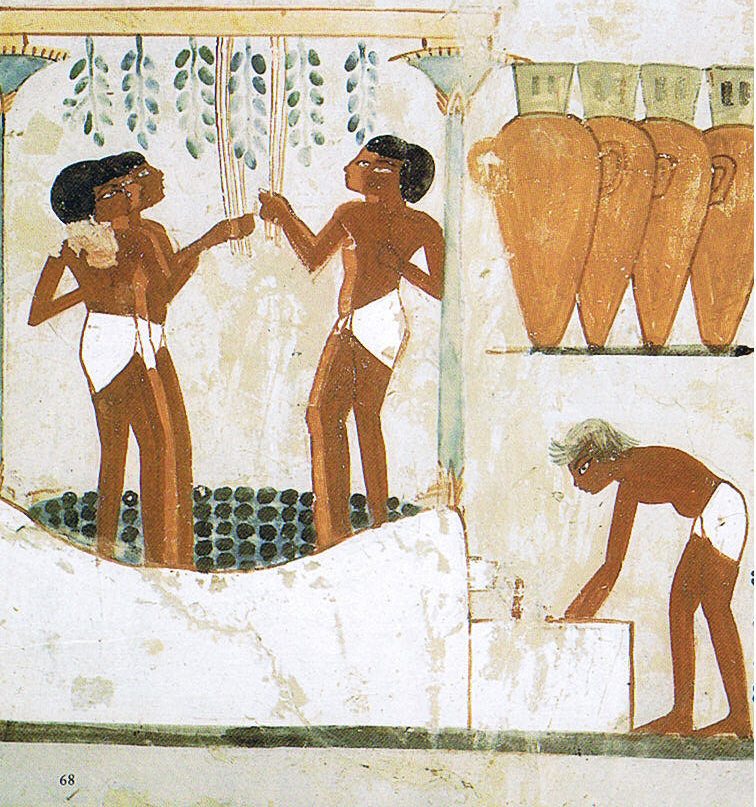

Our understanding of the nature and organisation of ancient Egyptian pottery manufacture is based on tomb paintings, models, and archaeological remains of pottery workshops. A characteristic of the development of Egyptian ceramics is that the new methods of production which were developed over time never entirely replaced older methods, but expanded the repertoire instead, so that eventually, each group of objects had its own manufacturing technique. Egyptian potters employed a wide variety of decoration techniques and motifs, most of which are associated with specific periods of time, such as the creation of unusual shapes, decoration with incisions, various different firing processes, and painting techniques.

An important

classification Classification is a process related to categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated and understood.

Classification is the grouping of related facts into classes.

It may also refer to:

Business, organizat ...

system for Egyptian pottery is the ''Vienna system'', which was developed by ,

Manfred Bietak,

Janine Bourriau,

Helen

Helen may refer to:

People

* Helen of Troy, in Greek mythology, the most beautiful woman in the world

* Helen (actress) (born 1938), Indian actress

* Helen (given name), a given name (including a list of people with the name)

Places

* Helen, ...

and

Jean Jacquet, and

Hans-Åke Nordström

Hans-Åke Nordström (1933-2022) was a Swedish archaeologist and professor at Uppsala University. His work has included excavations in parts of Nubia, submerged since the construction of the Aswan Dam, and the development of the Vienna System for c ...

at a meeting in

Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

in 1980.

Seriation of Egyptian pottery has proven useful for the

relative chronology of ancient Egypt. This method was invented by

Flinders Petrie

Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie ( – ), commonly known as simply Flinders Petrie, was a British Egyptologist and a pioneer of systematic methodology in archaeology and the preservation of artefacts. He held the first chair of Egyp ...

in 1899. It is based on the changes of vessel types and the proliferation and decline of different types over time.

Material

Understanding of the raw material is essential for understanding the development, production, and typology of Egyptian ceramics. In

Egyptian archaeology

Egyptology (from ''Egypt'' and Greek , ''-logia''; ar, علم المصريات) is the study of ancient Egyptian history, language, literature, religion, architecture and art from the 5th millennium BC until the end of its native religious p ...

the distinction between Nile clay and marl clay is fundamental. Mixtures of the two types of clay can be seen as a third group.

[D. Arnold: "Keramik", ''LÄ III'', col. 394.]

Nile clay

Nile clay is the result of

eroded material in the

Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

n mountains, which was transported into Egypt by the Nile. This clay was deposited on the banks of the Nile in Egypt since the

Late Pleistocene

The Late Pleistocene is an unofficial age in the international geologic timescale in chronostratigraphy, also known as Upper Pleistocene from a stratigraphic perspective. It is intended to be the fourth division of the Pleistocene Epoch withi ...

by the

cyclic Nile floods. As a result, deposits can be found far from the modern floodplain as well as within the level covered by the flood in modern times. Chemically, the clay is characterised by high

silicon

Silicon is a chemical element with the symbol Si and atomic number 14. It is a hard, brittle crystalline solid with a blue-grey metallic luster, and is a tetravalent metalloid and semiconductor. It is a member of group 14 in the periodic ...

content and a high level of

iron oxide

Iron oxides are chemical compounds composed of iron and oxygen. Several iron oxides are recognized. All are black magnetic solids. Often they are non-stoichiometric. Oxyhydroxides are a related class of compounds, perhaps the best known of wh ...

. Mineralogically, it is

mica

Micas ( ) are a group of silicate minerals whose outstanding physical characteristic is that individual mica crystals can easily be split into extremely thin elastic plates. This characteristic is described as perfect basal cleavage. Mica is ...

caeous,

illite

Illite is a group of closely related non-expanding clay minerals. Illite is a secondary mineral precipitate, and an example of a phyllosilicate, or layered alumino-silicate. Its structure is a 2:1 sandwich of silica tetrahedron (T) – alumina ...

-rich sediment clay, containing many different

sand

Sand is a granular material composed of finely divided mineral particles. Sand has various compositions but is defined by its grain size. Sand grains are smaller than gravel and coarser than silt. Sand can also refer to a textural class ...

and stone particles brought from the various contexts through which the Nile flows.

The clay turns a red or brown colour when it is

fired in an oxygen-rich oven. When unfired, it varies in colour from grey to nearly black.

[Janine D. Bourriau, Paul T. Nicholson, Pamela J. Rose: "Pottery." Paul T. Nicholson, Ian Shaw (ed.): ''Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology.'' ]Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

2000, p. 121.

Marl clay

The marl clay (or 'desert clay') is found along the Nile valley, from

Esna

Esna ( ar, إسنا , egy, jwny.t or ; cop, or ''Snē'' from ''tꜣ-snt''; grc-koi, Λατόπολις ''Latópolis'' or (''Pólis Látōn'') or (''Lattōn''); Latin: ''Lato''), is a city of Egypt. It is located on the west bank of ...

to

Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metr ...

, in the

oases

In ecology, an oasis (; ) is a fertile area of a desert or semi-desert environment'ksar''with its surrounding feeding source, the palm grove, within a relational and circulatory nomadic system.”

The location of oases has been of critical im ...

and at the edges of the

Nile Delta

The Nile Delta ( ar, دلتا النيل, or simply , is the delta formed in Lower Egypt where the Nile River spreads out and drains into the Mediterranean Sea. It is one of the world's largest river deltas—from Alexandria in the west to ...

. It is a yellow-white stone, which is found in limestone deposits. The deposits were created in the Pleistocene, when the original Nile river and its tributaries deposited this clay in what had previously been desert. Marl clay includes a range of kinds of clay based on their base substance. In general, they have a lower percentage of silica and significantly higher

calcium

Calcium is a chemical element with the symbol Ca and atomic number 20. As an alkaline earth metal, calcium is a reactive metal that forms a dark oxide-nitride layer when exposed to air. Its physical and chemical properties are most similar ...

content.

[D. Arnold: "Keramik." ''LÄ III'', col. 395.] The most important sub-types of marl clay are:

* Qena clay: secondary deposits like that at Wadi

Qena

Qena ( ar, قنا ' , locally: ; cop, ⲕⲱⲛⲏ ''Konē'') is a city in Upper Egypt, and the capital of the Qena Governorate. Situated on the east bank of the Nile, it was known in antiquity as Kaine ( Greek Καινή, meaning "new (city ...

. This clay comes from sediments which were washed down the

wadi

Wadi ( ar, وَادِي, wādī), alternatively ''wād'' ( ar, وَاد), North African Arabic Oued, is the Arabic term traditionally referring to a valley. In some instances, it may refer to a wet (ephemeral) riverbed that contains water ...

and mixed with local

slate

Slate is a fine-grained, foliated, homogeneous metamorphic rock derived from an original shale-type sedimentary rock composed of clay or volcanic ash through low-grade regional metamorphism. It is the finest grained foliated metamorphic rock. ...

and limestone.

* Marl clay from slate and limestone which is found along the Nile between Esna and Cairo.

Marl clay is normally cream or white in colour when it is fired in an oxygen-rich oven. Cuts can reveal pink or orange areas. It is rich in mineral salts, so the outer surface often has a thin layer of weathered

salt

Salt is a mineral composed primarily of sodium chloride (NaCl), a chemical compound belonging to the larger class of salts; salt in the form of a natural crystalline mineral is known as rock salt or halite. Salt is present in vast quant ...

which forms a white surface layer when fired, which can be mistaken for a 'glaze' by the unwary. At higher firing temperature (c. 1000 °C), this layer becomes olive-green and resembles a green glaze.

[Janine D. Bourriau, Paul T. Nicholson, Pamela J. Rose, "Pottery." Paul T. Nicholson, Ian Shaw (ed.): ''Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology.'' Cambridge 2000, p. 122.]

File:Karima,nile silt.jpg, Dry, clay-filled Nile mud, in an area near Karima, Sudan

Karima is a town in Northern State in Sudan some 400 km from Khartoum on a loop of the Nile.

Karima houses the Jebel Barkal Museum. The hill of Jebel Barkal is near Karima. Beside it are the ruins of Napata, a city-state of ancient Nub ...

which is flooded annually.

File:Aufgearbeiteter Ton.JPG, Mineral clay after collection

Production

Selection of material

The selection of material was based on local conditions and the function of the object being manufactured. Nile clay was principally used for household crockery and containers, as well as ceramics for ritual use. Marl clay was principally used for storage and prestige objects like figural vessels.

[D. Arnold: ''Keramik.'' In: ''LÄ III'', Sp. 399.]

Gathering the clay

There is little precise information on how and where Egyptian potters got their raw material, how

clay pit

A clay pit is a quarry or mine for the extraction of clay, which is generally used for manufacturing pottery, bricks or Portland cement. Quarries where clay is mined to make bricks are sometimes called brick pits.

A brickyard or brickworks i ...

s were run, how it was transported and how it was assigned to individual potters.

In general, it seems that the clay came from three different places: the shore of the Nile or irrigation canals, the desert near the fields, and the hills of the desert itself. A depiction in the tomb of

Rekhmire (

TT100

The Theban Tomb TT100 is located in Sheikh Abd el-Qurna, part of the Theban Necropolis, on the west bank of the Nile, opposite to Luxor. It is the mortuary chapel of the ancient Egyptian vizier Rekhmire. There is no burial chamber next to thi ...

) shows workers in the process of building up pile of Nile mud with hoes in order to make

mudbrick

A mudbrick or mud-brick is an air-dried brick, made of a mixture of loam, mud, sand and water mixed with a binding material such as rice husks or straw. Mudbricks are known from 9000 BCE, though since 4000 BCE, bricks have also been ...

s. Clay for pottery production might have been gathered in a similar way. The scene also shows that Nile clay did not absolutely have to be taken from the fields. Piles of Nile clay were built up in the process of digging irrigation canals - as still happens today.

File:Maler der Grabkammer des Rechmirê 002.jpg, Gathering Nile mud in order to make mudbricks.

File:Bundesarchiv Bild 135-S-17-16-28, Tibetexpedition, Lössabbau.jpg, Use of hoes to gather loess

Loess (, ; from german: Löss ) is a clastic, predominantly silt-sized sediment that is formed by the accumulation of wind-blown dust. Ten percent of Earth's land area is covered by loess or similar deposits.

Loess is a periglacial or aeoli ...

in Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa people, ...

(photo from 1938)

Preparation of the clay

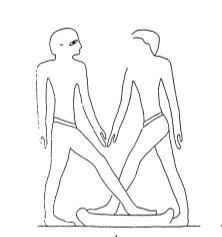

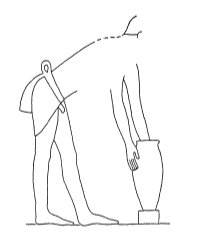

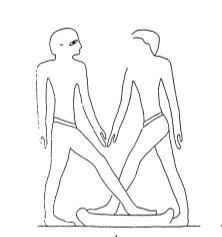

Egyptian tomb paintings often show the preparation of the clay. There are also models which provide some other details. Clear archaeological remains of pottery workshops, however, are rare. It is possible that they were very ephemeral structures.

Clay which is exposed to air, dries very quickly. As a result, clay often reached the potter as dry, stony clumps (especially the marl clay from the desert) which first had to be cleaned and mixed with water in order to make it possible to shape it. The raw clay was also dried and crushed in order to remove any large impurities, like stones, by passing it through a sieve. Another possibility was the

elutriation

Elutriation is a process for separating particles based on their size, shape and density, using a stream of gas or liquid flowing in a direction usually opposite to the direction of sedimentation. This method is mainly used for particles smalle ...

of the clay by repeatedly immersing hard clay pellets in water and skimming the fine clay off the top. There is no evidence for such a process in the pottery workshop in

Ayn Asil (

Dakhla Oasis

Dakhla Oasis (Egyptian Arabic: , , "''the inner oasis"''), is one of the seven oases of Egypt's Western Desert. Dakhla Oasis lies in the New Valley Governorate, 350 km (220 mi.) from the Nile and between the oases of Farafra and Khar ...

), but there is some possible evidence at

Hieraconpolis. This elutriation would have to have been carried out in one or more pits or watering holes. Even before these finds, the depictions of potters in the tomb of (

TT93) had been interpreted as depicting elutriation in a watering hole. At least for the clay used in Meidum-ware in the Old Kingdom and the remarkably homogeneous Nile clay used from the beginning of the 18th dynasty, some kind of refining technology must have been used.

Standard images show one or two men involved in preparing the clay, once they had softened it, by treading it with their feet in order to turn it into a malleable mass. At this stage, the clay might be supplemented with

temper, if it was decided that it did not already contain sufficient fine impurities, like sand. It was important that these not be too big or sharp, "excessively large temper can make the walls of pottery vessels unstable, since the clay will not be able to mesh together properly. Sharp particles, like stones, could hurt the potter when kneading the clay and forming the vessels and prevent the creation of a smooth surface." Through the addition of balanced temper, the clay could be made "more malleable and stable during production, and also more porous, which made it easier to dry, bake, and use the finished vessel."

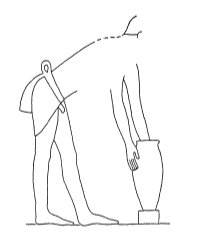

After the clay had been mixed with water it would be full of air bubbles. To prevent cracking during the firing process, the clay had to be kneaded. In this process, two halves of a lump of clay were beaten against one another with significant force. In the tomb paintings, a worker in a bent position is shown working the clay with his hands before handing the kneaded balls directly over to the potter.

Shaping

There were five different techniques for shaping clay in ancient Egypt:

* by hand

* using a rotatable pilaster

* using a

potter's wheel

In pottery, a potter's wheel is a machine used in the shaping (known as throwing) of clay into round ceramic ware. The wheel may also be used during the process of trimming excess clay from leather-hard dried ware that is stiff but malleable, ...

operated by one of the potter's hands

* using a

mould

* on a rapidly spinning potter's wheel, operated by an assistant or the potter's foot.

Characteristic of the development of ceramics is that, although new methods were developed over time, they never entirely replaced older ones. Rather, they expanded the repertoire, so that at the high point in the history of Egyptian pottery, each type of object had its own manufacturing technique.

Hand-shaping

There were several different techniques for making pottery by hand: stacking a number of

coils on a flat clay base, weaving, and free modelling. These three techniques were used from the

predynastic

Prehistoric Egypt and Predynastic Egypt span the period from the earliest human settlement to the beginning of the Early Dynastic Period around 3100 BC, starting with the first Pharaoh, Narmer for some Egyptologists, Hor-Aha for others, with th ...

period until at least the Old Kingdom.

[C. Köhler: ''Buto III. Die Keramik von der späten Vorgeschichte bis zum frühen Alten Reich (Schicht III bis VI).'' Mainz 1998, p. 69.]

Free modelling by kneading and pulling at the clay with the hands is the oldest and most enduring technique for shaping clay. It was employed for all vessels in the

Faiyum A culture, in the

Merimde culture, and probably also in the

Badari culture. In the Old Kingdom, it was used for the most important types and it was used for figures and models in all periods.

The resulting product had thick walls. The technique is recognisable by pressure marks where individual bits of clay have been pressed together.

In the weaving technique, flat rectangular pieces of clay were woven together. The technique can be recognised by the fact that the broken vessels tend to form rectangular sherds. The technique seems to have come into widespread use in early Egypt, from the time when larger pottery vessels began to be made at the latest. Throughout the whole Pharaonic period and down to Roman times, large basins and tubs were made using this technique.

In the clay coil method, a series of coils of clay were stacked one on top of the other to form the walls of a pot. This technique is seen in late predynastic pottery from

Heliopolis.

Rotating pilaster

During the

Chalcolithic

The Copper Age, also called the Chalcolithic (; from grc-gre, χαλκός ''khalkós'', "copper" and ''líthos'', "Rock (geology), stone") or (A)eneolithic (from Latin ''wikt:aeneus, aeneus'' "of copper"), is an list of archaeologi ...

, the rotating pilaster came into use for the manufacture of ceramics. This may have arisen from the desire to make the body and especially the opening of the vessel being made symmetrical. The technique can be clearly recognised from a horizontal rotation mark in the opening of the vessel.

Unlike the potter's wheel, there was no fixed axis around which rotations were centred.

The pilaster used in this technique could by a bowl, plate, basket, mat, textile, or even a pottery sherd. This pilaster was rotated along with the vessel, as the potter shaped it. The rotation technique was used only for the creation of the vessel's shell. The earlier techniques were also used for other parts of the manufacturing process. Thus, on finished vessels, traces of free modelling are found, especially in the lower parts, but the edges were turned after the completion of the whole vessel.

Hand-operated potter's wheel

An important advance was the invention of the

potter's wheel

In pottery, a potter's wheel is a machine used in the shaping (known as throwing) of clay into round ceramic ware. The wheel may also be used during the process of trimming excess clay from leather-hard dried ware that is stiff but malleable, ...

, which rotated on a central axis. This enabled the potter to rotate the wheel and the vessel with one hand, while shaping the vessel with the other hand.

[C. Köhler: ''Buto III. Die Keramik von der späten Vorgeschichte bis zum frühen Alten Reich (Schicht III bis VI).'' Mainz 1998, p. 70.]

According to , the slow potter's wheel was invented some time during the

Fourth Dynasty. has subsequently argued that this should be corrected to a substantially earlier period, "the invention of the potter's wheel is a development which generally accompanied a certain form of mass-production. It enabled standardisation and the rapid production of finished vessels."

According to her, this development can clearly be traced back to the mass-produced conical bowls of the

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

n

Uruk culture at

Habuba Kabira.

In production, first, a large clay cone was shaped on the disc. The peak of the cone was the actual point of rotation, around which the bowl was to be formed. It was then sliced off with a wire or a cord. The resulting bowls had a relatively thick wall near the base and marks from rotation and pulling on the underside of the base. Christiana Köhler detected such marks on vessels of the predynastic period, which makes it fairly likely that the slow potter's wheel was in use in this period.

Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Gui ...

(c. 1930)

Mold

It is assumed that baking pans for conical bread were made with the help of a mold. It is possible that they were shaped around a conical wooden core, which had the shape of the conical bread which would eventually be baked in the pans.

Fast potter's wheel

Manufacture on the fast potter's wheel, operated by an assistant or the foot of the potter was a relatively late development, which took place in the New Kingdom at the earliest. The earliest depiction comes from the Tomb of Kenamun from the middle of the

Eighteenth Dynasty, in which an assistant grips the wheel and thereby helps the potter to use the wheel, while the potter himself uses his foot to stabilise it.

Surface treatment

The shaped vessel first had to be dried enough that the walls would be stable for further work. The clay was brought to roughly the consistency of leather, remaining damp enough that it could still be moulded and shaped. At this point paint,

glaze and

slip could be added if desired. After further drying the vessel was polished.

[C. Köhler: ''Buto III. Die Keramik von der späten Vorgeschichte bis zum frühen Alten Reich (Schicht III bis VI).'' Mainz 1998, p. 71.] There were two techniques for polishing the vessel's surface:

[D. Arnold: "Keramik." In: ''LÄ III'', col. 401 f.]

* Polishing by rubbing without pressure produced a consistent, light sheen. Examples include jugs from the Old Kingdom, jugs and dishes from the

First Intermediate Period

The First Intermediate Period, described as a 'dark period' in ancient Egyptian history, spanned approximately 125 years, c. 2181–2055 BC, after the end of the Old Kingdom. It comprises the Seventh (although this is mostly considered spuriou ...

and possibly the

Middle Kingdom.

* Polishing with a burnish or significant pressure on the vessel's surface. This results in very shiny surfaces, but only in rare cases of especially careful work (such as

Meidum

Meidum, Maydum or Maidum ( ar, ميدوم, , ) is an archaeological site in Lower Egypt. It contains a large pyramid and several mudbrick mastabas. The pyramid was Egypt's first straight-sided one, but it partially collapsed in ancient times. The ...

bowls of the Old Kingdom) are no polishing marks left behind. In the

Thinis

Thinis (Greek: Θίνις ''Thinis'', Θίς ''This'' ; Egyptian: Tjenu; cop, Ⲧⲓⲛ; ar, ثينيس) was the capital city of the first dynasties of ancient Egypt. Thinis remains undiscovered but is well attested by ancient writers, incl ...

period and the

Seventeenth and

Eighteenth dynasties, potters made decorative patterns with the marks left by this polishing process.

At this stage, impressions or incisions could also be made in the clay, "when the clay was still damp enough that it would not break in the process, but was dry enough that no raised areas would be left in the incisions." This was done with various tools, including bone or wooden nails, combs made from bone or shellfish, and

flint

Flint, occasionally flintstone, is a sedimentary cryptocrystalline form of the mineral quartz, categorized as the variety of chert that occurs in chalk or marly limestone. Flint was widely used historically to make stone tools and start ...

knives.

After an initial drying phase, the round base was finished. This was done by hand until the seventeenth dynasty, using a flat tool to cut and smooth the base. A foot was also cut by hand, or molded from an additional lump of clay. After the beginning of the seventeenth dynasty, the foot was instead made on the potter's wheel from the mass of clay used for the creation of the base of the vessel. At this point, bases and stands increasingly have rotation marks on the outside.

Drying

In the drying process, the vessel had to be kept under controlled conditions, such that all parts of the vessel dried equally and no shrinking took place. In this process, a lot of water had to evaporate, since the remaining water would boil at the beginning of the firing process, which led the water vapour to expand in volume, leading to explosions if it could not escape.

The vessel was left to dry in direct sunlight when the light was weak, in the shade when it was strong, or in a closed room when it was raining or cold. The drying process could take several days, depending on the humidity, the size, wall-thickness, and porosity of the vessel. Even when drying was complete, vessels remained between 3-5% saturated with water, which was only expelled during the firing process.

Firing

In the

firing

Dismissal (also called firing) is the termination of employment by an employer against the will of the employee. Though such a decision can be made by an employer for a variety of reasons, ranging from an economic downturn to performance-related ...

process, the clay is transformed from a malleable material to a rigid one. Up to this point it is possible to make the clay malleable again by making it wet. After firing, damaged vessels, like misfirings, are nearly unfixable.

[Janine D. Bourriau, Paul T. Nicholson, Pamela J. Rose: "Pottery." In: Paul T. Nicholson, Ian Shaw (ed.): ''Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology.'' Cambridge 2000, p. 127.]

In order for the transformation of the clay into this final and moisture-less form, it must be heated to a temperature of 550–600 °C. Before this, at around 100 °C, residual moisture escapes into the air and at 300 °C the chemically-bonded

water of crystallization

In chemistry, water(s) of crystallization or water(s) of hydration are water molecules that are present inside crystals. Water is often incorporated in the formation of crystals from aqueous solutions. In some contexts, water of crystallization i ...

also escapes. The supply of

oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements ...

during the firing process is critical, since it is used up as the fuel is burnt. If more is not supplied (e.g. through a vent), an atmosphere rich in

carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide ( chemical formula CO) is a colorless, poisonous, odorless, tasteless, flammable gas that is slightly less dense than air. Carbon monoxide consists of one carbon atom and one oxygen atom connected by a triple bond. It is the simpl ...

or free

carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element with the symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalent—its atom making four electrons available to form covalent chemical bonds. It belongs to group 14 of the periodic table. Carbon ma ...

will develop and it will create a black or brown-black

iron(II) oxide

Iron(II) oxide or ferrous oxide is the inorganic compound with the formula FeO. Its mineral form is known as wüstite. One of several iron oxides, it is a black-colored powder that is sometimes confused with rust, the latter of which consists of ...

, which gives the fired pottery a grey or dark brown colour. This is called a

reducing firing. In an

oxidating firing by contrast, a continuous supply of oxygen is maintained. The iron in the clay absorbs oxygen and becomes the red or red-brown

iron(III) oxide

Iron(III) oxide or ferric oxide is the inorganic compound with the formula Fe2O3. It is one of the three main oxides of iron, the other two being iron(II) oxide (FeO), which is rare; and iron(II,III) oxide (Fe3O4), which also occurs naturally a ...

. The resulting pottery has a red-brown colour.

The simplest and earliest firing method is the

open fire. The vessel to be fired is covered and filled with flammable material. It is placed on a flat piece of ground, surrounded by a low wall, or put in a pit. During the firing process, the potter has relatively little control. The vessel is in direct contact with the flames and the fuel, which heats quickly and then cools down again quickly.

Optimisation of the firing process became possible once the pottery was placed inside a chamber with a vent and separated from the fuel of the fire, i.e. a

kiln

A kiln is a thermally insulated chamber, a type of oven, that produces temperatures sufficient to complete some process, such as hardening, drying, or chemical changes. Kilns have been used for millennia to turn objects made from clay int ...

. This technological leap was made in the early Old Kingdom at the latest, but possibly in the

Early Dynastic or late Predynastic period.

[C. Köhler: ''Buto III. Die Keramik von der späten Vorgeschichte bis zum frühen Alten Reich (Schicht III bis VI).'' Mainz 1998, p. 72.]

The simplest form of a kiln was a shaft with no separation of the area where the fuel was burnt from the chamber where the ceramics were placed. This could be loaded through a shaft and then set on fire through an opening on the ground. This opening enabled a continuous supply of oxygen, which could be used to create an oxidising atmosphere. The oven now had to reach a set firing temperature in order to heat the clay in the firing chamber. As a result, the fire lasted longer and burnt more consistently.

The next technological advance was the introduction of a grating, which separated the fuel from the pottery being fired. This prevented smoky flames and carbonised fuel from coming in contact with the ceramics and leaving flecks and smudges on it.

The vessels being fired were placed in the upper part, with the opening underneath. The hot air rose up to the vessels and circulated around them, indirectly firing the clay.

[Janine D. Bourriau, Paul T. Nicholson, Pamela J. Rose: "Pottery." In: Paul T. Nicholson, Ian Shaw (ed.): ''Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology.'' Cambridge 2000, p. 128.] Shaft ovens of this type, with a grating, are attested in

Egyptian art

Ancient Egyptian art refers to art produced in ancient Egypt between the 6th millennium BC and the 4th century AD, spanning from Prehistoric Egypt until the Christianization of Roman Egypt. It includes paintings, sculpture ...

and by archaeology from the Old Kingdom onwards.

Decoration

Egyptian potters employed a broad range of decorative techniques and motifs, many of which are characteristic of specific periods. There are three points in the manufacturing process in which decoration could be added: before, during, or after the firing process.

Since the predynastic period, potters added decorative elements in the molding stage, creating unusual shapes or imitating other materials, like basketwork, metal, wood or stone. The majority of the 'fancy features' were created during the process of shaping the vessel and smoothing its surfaces, long before it was fired. The elements were either shaped from a piece of clay by hand or impressed into the clay while it was still malleable - often causing fingerprints to be left on the inside of the vessel. In figural vessels, these were often parts of a human or animal body, or the face of the god

Bes BES or Bes may refer to:

* Bes, Egyptian deity

* Bes (coin), Roman coin denomination

* Bes (Marvel Comics), fictional character loosely based on the Egyptian deity

Abbreviations

* Bachelor of Environmental Studies, a degree

* Banco Espírito ...

or the goddess

Hathor

Hathor ( egy, ḥwt-ḥr, lit=House of Horus, grc, Ἁθώρ , cop, ϩⲁⲑⲱⲣ, Meroitic: ) was a major goddess in ancient Egyptian religion who played a wide variety of roles. As a sky deity, she was the mother or consort of the sky ...

. It was also common to cut out parts of the vessel in order to imitate another type of material.

Even in the earliest Egyptian pottery, produced by an early phase of the

Merimde culture, there are incised decorations like the

herringbone pattern

The herringbone pattern is an arrangement of rectangles used for floor tilings and road pavement, so named for a fancied resemblance to the bones of a fish such as a herring.

The blocks can be rectangles or parallelograms. The block edge length ...

. In this technique, the surface of the pot was scratched with a sharp instrument, like a twig, knife, nail, or fingernail before it was fired.

Pots fired in a firing pit often have a black upper rim. These black rims were increasingly a decorative feature, which required technical knowledge to produce consistently. In combination with a dark-red colour and polish, this

''black-topped'' ware was one of the most fashionable and popular types of pottery. The black colour was a result of

carbonisation

Carbonization is the conversion of organic matters like plants and dead animal remains into carbon through destructive distillation.

Complexity in carbonization

Carbonization is a pyrolytic reaction, therefore, is considered a complex process ...

, created by the introduction of smoke particles to the oven during the firing process for example. Some aspects of this special process are still unclear.

Painted decoration could be added with a brush before or after firing. For specific patters, paint might be sprayed on the surface of a vessel, or it might be dipped in the paint. There are eight major types of painted pottery from ancient Egypt:

* Petrie's ''white-cross-lined'' style: this pottery is found only in

Upper Egypt

Upper Egypt ( ar, صعيد مصر ', shortened to , , locally: ; ) is the southern portion of Egypt and is composed of the lands on both sides of the Nile that extend upriver from Lower Egypt in the north to Nubia in the south.

In ancient E ...

in the

Naqada I culture (c. 4000–3500 BC). It s usually made from Nile clay (Nile clay A). The surface is a dark red or reddish brown and is polished. The characteristic feature of this style is the white or cream coloured painting of geometric patterns or (occasionally) animals, plants, people and boats.

* Petrie's ''decorated'' style: this pottery is typical of the

Naqada II

The Gerzeh culture, also called Naqada II, refers to the archaeological stage at Gerzeh (also Girza or Jirzah), a prehistoric Egyptian cemetery located along the west bank of the Nile. The necropolis is named after el-Girzeh, the nearby contem ...

and

Naqada III

Naqada III is the last phase of the Naqada culture of ancient Egyptian prehistory, dating from approximately 3200 to 3000 BC. It is the period during which the process of state formation, which began in Naqada II, became highly visible, w ...

cultures (c. 3500–3000 BC). It is usually made of marl clay (marl clay A1). The surface is thoroughly smoothed, but not polished and its colour varies from light red to yellowy grey. Red-brown paint was used to paint a number of motifs - most commonly, ships, deserts, flamingos, people, spirals, wavy lines, and Z-shaped lines.

* ''White background'' style: this style was made in the

First Intermediate Period

The First Intermediate Period, described as a 'dark period' in ancient Egyptian history, spanned approximately 125 years, c. 2181–2055 BC, after the end of the Old Kingdom. It comprises the Seventh (although this is mostly considered spuriou ...

, early Middle Kingdom, New Kingdom, and the

Late Period (c. 2200–300 BC). The surfaces of this style were decorated with various colours on a white background, after firing. The decoration normally depicts carefully designed offering scenes.

* The ''scenic'' style: this style occurred sporadically in all periods. It is very similar to the ''white background'' style, except that the scenes were painted directly onto the surface of the vessel without a white background.

* The ''blue-painted'' style: this style occurred from the middle of the 18th dynasty until the end of the

20th Dynasty

The Twentieth Dynasty of Egypt (notated Dynasty XX, alternatively 20th Dynasty or Dynasty 20) is the third and last dynasty of the Ancient Egyptian New Kingdom period, lasting from 1189 BC to 1077 BC. The 19th and 20th Dynasties furthermore toget ...

(c. 1500–1000 BC). It is characterised by the use of blue pigments, along with black, red and occasionally yellow. The main motif is floral decorations:

lotus flowers and buds, and individual petals of various flowers, painted as if they were on a thread draped around the neck and shoulders of the vase. Depictions of young animals and symbols of Hathor and Bes are also encountered. The vessels are usually made of Nile clay.

* The ''brown-and-red painted'' style: this style developed at the beginning of the 18th Dynasty (c. 1500 BC) from the decorative use of lines in the late Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate period. Unlike the ''blue-painted'' style, this pottery is usually made from marl clay. The style is characterised by very specific decorative patters: a group of two to four parallel lines, with various elements like dots, zigzag lines, wavy lines, and the like painted in between them. These were painted in different colours: either brown elements and red lines or vice versa.

* The ''lotus-flower-and-crosslined-band'' style.

File:Naqada II Vessels 1.jpg, Decorated pottery vessel of the Naqada II period (Petrie's ''decorated'' style)

File:RPM Ägypten 130.jpg, ''Black-Topped'' pottery of the Naqada I period

File:WineVesselWithMaskOfGodBes.png, Bes pot

Objects and function

In Egyptology, the term 'pottery' is used to refer to all non-figural objects made from fired clay. The majority of pottery vessels surely served as household wares and were used for the storage, preparation, transport and consumption of food and other raw materials. In addition to this, there were other objects frequently used in the household, like bread moulds, fireboxes, lamps and stands for vessels with round bases. Other types of pottery served ritual purposes. Sometimes water pipes were constructed from

amphora

An amphora (; grc, ἀμφορεύς, ''amphoreús''; English plural: amphorae or amphoras) is a type of container with a pointed bottom and characteristic shape and size which fit tightly (and therefore safely) against each other in storag ...

e laid back-to-back, but actual ceramic water pipes were only introduced in the

Roman period

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediter ...

. Musical instruments, like

rattles, could also be made from ceramics, in the form of bottles filled with pebbles and then sealed before being fired.

[Dorothea Arnold, ''Keramik.'' in Wolfgang Helck, Wolfhart Westendorf: ''Lexikon der Ägyptologie.'' Vol. III, Wiesbaden 1980, col. 392][Janine D. Bourriau, Paul T. Nicholson, Pamela J. Rose: "Pottery," Paul T. Nicholson, Ian Shaw (ed.): ''Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology.'' Cambridge 2000, p. 142.]

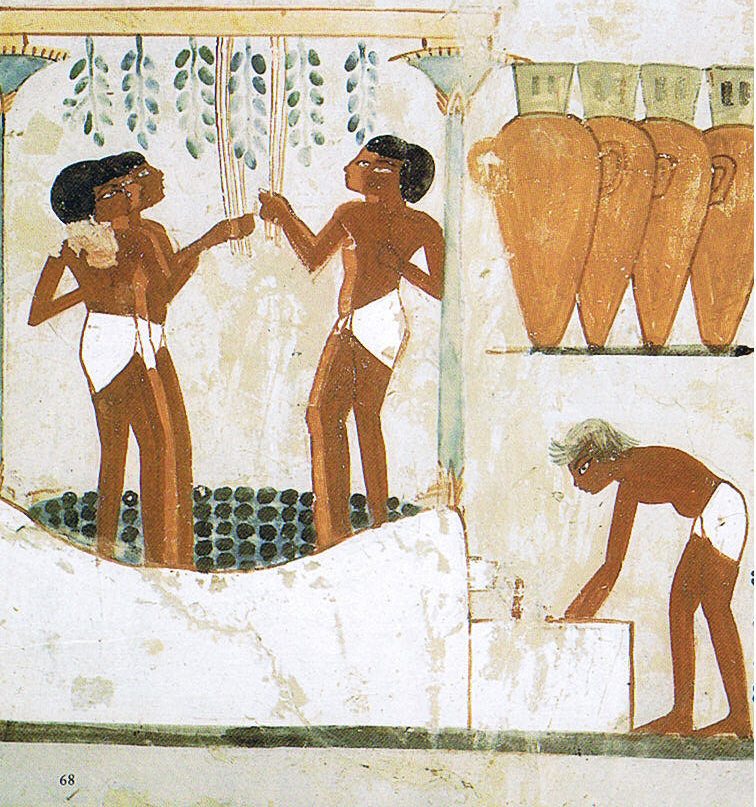

Evidence for the function of individual pottery types is given by depictions in tombs, textual descriptions, their shape and design, remains of their contents, and the archaeological context in which they are found. In tombs, pottery is often only sketched out schematically. Nevertheless, in some cases it is possible to identify the function of a vessel based on depictions in tombs. Examples include bread molds, spinning weights, and beer jugs. The shapes of beer jugs make it possible to link them with scenes of beer manufacture, such as the Mastaba of Ti: they are ovoid, round-bodied bottles, often with weakly defined lips, which are generally roughly shaped and are made of clay with a lot of organic matter mixed in.

[C. Köhler: ''Buto III. Die Keramik von der späten Vorgeschichte bis zum frühen Alten Reich (Schicht III bis VI).'' Mainz 1998, pp. 40 ff.]

Inscriptions giving the contents of the vessel are not unusual in the New Kingdom. As a result, wine jugs and

fish kettle

A fish kettle is a kind of large, oval-shaped kettle used for cooking whole fish. Owing to their necessarily unwieldy size, fish kettles usually have racks and handles, and notably tight-fitting lids.

''Larousse Gastronomique'' describes the fish ...

s can be identified, although wine jugs were also used for other raw materials, like oil and honey. One of the largest finds of inscribed wine vessels came from the tomb of

Tutankhamun

Tutankhamun (, egy, twt-ꜥnḫ-jmn), Egyptological pronunciation Tutankhamen () (), sometimes referred to as King Tut, was an Egyptian pharaoh who was the last of his royal family to rule during the end of the Eighteenth Dynasty (ruled ...

(

KV62

The tomb of Tutankhamun, also known by its tomb number, KV62, is the burial place of Tutankhamun (reigned c. 1334–1325 BC), a pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt, Eighteenth Dynasty of ancient Egypt, in the Valley of the Kings. The tomb ...

). The inscriptions on the 26 inscribed wine jugs provide more information about the wine they contain than most modern wine labels. The year of the

lees was recorded in the king's regnal years. The quality, the origin of the grapes, the owner of the winery, and the name of the

vintner

A winemaker or vintner is a person engaged in winemaking. They are generally employed by wineries or wine companies, where their work includes:

*Cooperating with viticulturists

*Monitoring the maturity of grapes to ensure their quality and to dete ...

who was responsible for the actual product were all recorded. (See also ).

The vessels themselves provide evidence for their purpose, for example by the type of clay used, the treatment of the outer surface, and the shape of the vessel. Among the significant factors, is whether

porosity

Porosity or void fraction is a measure of the void (i.e. "empty") spaces in a material, and is a fraction of the volume of voids over the total volume, between 0 and 1, or as a percentage between 0% and 100%. Strictly speaking, some tests measur ...

was desirable or not. Thus, in modern water jugs like ''zirs'' and ''gullas'', the water seeps through the walls, so that the contents can be

cooled through evaporation.

[Janine D. Bourriau, Paul T. Nicholson, Pamela J. Rose: "Pottery." Paul T. Nicholson, Ian Shaw (ed.): ''Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology.'' Cambridge 2000, p. 143.] This effect can be best achieved with a bright clay or coating. Thus, Christiana Köhler in her study of the Early dynastic pottery from

Buto

Buto ( grc, Βουτώ, ar, بوتو, ''Butu''), Bouto, Butus ( grc, links=no, Βοῦτος, ''Boutos'') Herodotus ii. 59, 63, 155. or Butosus was a city that the Ancient Egyptians called Per-Wadjet. It was located 95 km east of Alexandr ...

was able to identify bottles or jugs with a white coating or light, large-grained marl clay, as water containers. An opposite effect could be created with a dark overcoat. By this, the pores of the outer surface were filled and the walls of the vessel were made impermeable to liquids. This made a vessel low-maintenance and hygienic, since no low-grade food residue would sick to the walls of the vessel. This can be seen, since no drink and food trays and plates can be detected.

Social context of production

The place of the ceramic industry in the wider social and economic context of ancient Egyptian society has been treated only cursorily in research to date.

Tomb decorations and pottery models provide only a few pieces of evidence for the context of pottery production. Depictions from the Old Kingdom are closely linked with brewery and bakery scenes (although these are also depicted separately at times). This indicates that pottery production was an independent part of food production. However, the inhabitants of tombs desired food and drink in the afterlife, not empty vessels.

Models of pottery workshops from the First Intermediate period and the Middle Kingdom give only a little indication of where the production took place. In all cases they are depicted in the open air - sometimes in a courtyard. More information is offered by the Middle Kingdom scenes in the tombs at

Beni Hasan

Beni Hasan (also written as Bani Hasan, or also Beni-Hassan) ( ar, بني حسن) is an ancient Egyptian cemetery. It is located approximately to the south of modern-day Minya in the region known as Middle Egypt, the area between Asyut and Me ...

. Here pottery production is shown taking place alongside other crafts, like carpentry, metal-working, textile production, and the manufacturing of stone vases - and much less frequently with food production. This trend continues in the only depictions we have from the New Kingdom, in the tomb of Kenamun in Thebes.

[Janine D. Bourriau, Paul T. Nicholson, Pamela J. Rose, "Pottery." in Paul T. Nicholson, Ian Shaw (ed.): ''Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology.'' Cambridge 2000, p. 136.]

The models only ever show one or two men at work, which might indicate that production was carried out on a small scale. In almost all depictions, the works are male. There are a few examples from the Old Kingdom of women participating in the production process, e.g. helping to load the kiln. Little is known about the individual workers, but they were surely of low social status. That they were not part of higher society is also indicated by the absence of epigraphic evidence for this vocation.

This is also illustrated by the ''Satire of the Occupations'':

On the other hand, pottery production had an important place in Egyptian culture. As part of everyday life it belonged to a level where perfection did not matter. From that point of view it was less about social stratification than about a stratification of the value which people attach to things. It would therefore be wrong to say that Egyptian potters were despised. There was a strong sense that the process was a creative one. Thus, the word for 'potter' (''qd'') is the same one used for 'building' walls and structures. Even the activities of creator gods were depicted using the image of the potter. The ram-headed creator god

Khnum

Khnum or also romanised Khnemu (; egy, 𓎸𓅱𓀭 ẖnmw, grc-koi, Χνοῦβις) was one of the earliest-known Egyptian deities, originally the god of the source of the Nile. Since the annual flooding of the Nile brought with it silt an ...

was shown creating gods, men, animals and plants on the potter's wheel. This suggests high esteem for ceramic production.

investigated the social and organisational circumstances of pottery production in the transitional period from the Old Kingdom to the Middle Kingdom, asking how the archaeological evidence can be connected to the image of the historical situation which we have built up from other sources. He concludes that the economic situation in the Old Kingdom favoured a centralised, standardised, and specialised production in great quantities, using complicated procedures. The organisational capacity of the state enabled focused production with high-quality pottery suitable for storage and transport in the context of the extensive distribution of goods by a centralised system. In the late Old Kingdom and the First Intermediate period, the centralised system deteriorated. It was replaced by decentralised production in small quantities for the circulation of goods within relatively small areas. In order to achieve high output, it was necessary to compromise on the quality of the wares. The profound transformation of the archaeological material indicates the extent of the social transformation which affected the whole cultural system at this time.

Economic context of production

E. Christiana Köhler has shown that a non-industrial system of pottery production, based in individual households, developed in late predynastic

Buto

Buto ( grc, Βουτώ, ar, بوتو, ''Butu''), Bouto, Butus ( grc, links=no, Βοῦτος, ''Boutos'') Herodotus ii. 59, 63, 155. or Butosus was a city that the Ancient Egyptians called Per-Wadjet. It was located 95 km east of Alexandr ...

in particular, as a result of the unfavourable climatic conditions of the

Nile delta

The Nile Delta ( ar, دلتا النيل, or simply , is the delta formed in Lower Egypt where the Nile River spreads out and drains into the Mediterranean Sea. It is one of the world's largest river deltas—from Alexandria in the west to ...

. At the same time, specialisation can already be seen in pottery production in the late Naqada I and early Naqada II cultures in

Upper Egypt

Upper Egypt ( ar, صعيد مصر ', shortened to , , locally: ; ) is the southern portion of Egypt and is composed of the lands on both sides of the Nile that extend upriver from Lower Egypt in the north to Nubia in the south.

In ancient E ...

, where the typical pottery found in settlements is a simple, tempered, weak Nile-clay pottery (''Rough ware''). However, the typical red ware for cemeteries, the ''Red-polished'' and ''Black-topped'' ware, was made entirely differently: "whereas the rough ware of the settlements was fired at only c. 500-800 °C, temperatures of up to 1000 °C were used for the red wares." Although the red ware had a fine-grained, thick fabric, it was only occasionally tempered and it required a controlled firing process. This situation suggests that two different systems of manufacture already existed: a professional, specialised industry making funerary pottery and household production of rough wares.

The environment of Upper Egypt seems to have been more conducive to specialised pottery production. In densely settled areas like

Hierakonpolis and

Naqada

Naqada ( Egyptian Arabic: ; Coptic language: ; Ancient Greek: ) is a town on the west bank of the Nile in Qena Governorate, Egypt, situated ca. 20 km north of Luxor. It includes the villages of Tukh, Khatara, Danfiq, and Zawayda. Ac ...

, there was also heavy demand for pottery. "In the course of Naqada II, a society developed in Upper Egypt which placed significant value in their burials and the grave goods that they included in them, so that the demand for high-value pottery quickly increased." Only for funerary pottery does there seem to have been any demand for professional pottery, since the fine wares are regularly found in graves and very rarely in settlement contexts.

The best archaeological evidence for pottery production is provided by kilns:

* Even in the predynastic period, pottery production in Hierakonpolis had reached amazing heights. Fifteen kiln complexes have been identified. The excavated kilns are not very technologically advanced, but they produced at least three different kinds of ware in many different forms for both household and funerary use.

* In the late

5th

Fifth is the ordinal form of the number five.

Fifth or The Fifth may refer to:

* Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, as in the expression "pleading the Fifth"

* Fifth column, a political term

* Fifth disease, a contagious rash tha ...

or early

6th Dynasty

The Sixth Dynasty of ancient Egypt (notated Dynasty VI), along with the Third, Fourth and Fifth Dynasty, constitutes the Old Kingdom of Dynastic Egypt.

Pharaohs

Known pharaohs of the Sixth Dynasty are listed in the table below. Manetho acc ...

, pottery was manufactured in the

Mortuary temple of the

Pyramid of Khentkaus II

The pyramid of Khentkaus II is a queen's pyramid in the necropolis of Abusir in Egypt, which was built during the Fifth dynasty of Ancient Egypt. It is attributed to the queen Khentkaus II, who may have ruled Egypt as a reigning queen after the ...

in

Abusir

Abusir ( ar, ابو صير ; Egyptian ''pr wsjr'' cop, ⲃⲟⲩⲥⲓⲣⲓ ' "the House or Temple of Osiris"; grc, Βούσιρις) is the name given to an Egyptian archaeological locality – specifically, an extensive necropolis ...

. It was a small worship, dated rather later than the actual establishment. Inside the temple, there was a manufacturing area, a storage space and a kiln. Possibly vessels were manufactured here for cult purposes.

* Near the mortuary temple of

Menkaure

Menkaure (also Menkaura, Egyptian transliteration ''mn-k3w-Rˁ''), was an ancient Egyptian king ( pharaoh) of the fourth dynasty during the Old Kingdom, who is well known under his Hellenized names Mykerinos ( gr, Μυκερῖνος) (by He ...

at

Giza

Giza (; sometimes spelled ''Gizah'' arz, الجيزة ' ) is the second-largest city in Egypt after Cairo and fourth-largest city in Africa after Kinshasa, Lagos and Cairo. It is the capital of Giza Governorate with a total population of 9.2 ...

, an industrial area has been excavated, which included kilns.

Mark Lehner

Mark Lehner is an American archaeologist with more than 30 years of experience excavating in Egypt. He was born in North Dakota in 1950. His approach, as director of Ancient Egypt Research Associates (AERA), is to conduct interdisciplinary archaeo ...

also identified possible locations for the mixing of the clay. All food production and pottery production was subordinate to worship.

* In

Elephantine

Elephantine ( ; ; arz, جزيرة الفنتين; el, Ἐλεφαντίνη ''Elephantíne''; , ) is an island on the Nile, forming part of the city of Aswan in Upper Egypt. The archaeological sites on the island were inscribed on the UNESCO ...

, there were kilns outside the walls of the city, which were established in the Old Kingdom. They date to the middle of the 4th C BC, through to the early 5th century BC, and were part of a substantial industry.

* The best example of a workshop in a settlement context, comes from Ayn Asil in the

Dakhla Oasis

Dakhla Oasis (Egyptian Arabic: , , "''the inner oasis"''), is one of the seven oases of Egypt's Western Desert. Dakhla Oasis lies in the New Valley Governorate, 350 km (220 mi.) from the Nile and between the oases of Farafra and Khar ...

. These workshops produced pottery from the end of the Old Kingdom into the First Intermediate Period and were located outside the settlement's walls, like the kilns in Elephantine. It is estimated that they were operated by teams of five to ten workers, working with a wide variety of clays and producing a number of different forms. The presence of bread moulds in these workshops led the excavators to conclude that there was no household pottery production in the community, since these would be the most likely things to be produced in individual households. However, not all the city's needs were met by this production and only a little locally produced pottery was found in the city's cemetery.

* In Nag el-Baba in

Nubia

Nubia () ( Nobiin: Nobīn, ) is a region along the Nile river encompassing the area between the first cataract of the Nile (just south of Aswan in southern Egypt) and the confluence of the Blue and White Niles (in Khartoum in central Sud ...

a pottery workshop has been uncovered, which was active from the

12th Dynasty

The Twelfth Dynasty of ancient Egypt (Dynasty XII) is considered to be the apex of the Middle Kingdom by Egyptologists. It often is combined with the Eleventh, Thirteenth, and Fourteenth dynasties under the group title, Middle Kingdom. Some ...

to the

Second Intermediate Period

The Second Intermediate Period marks a period when ancient Egypt fell into disarray for a second time, between the end of the Middle Kingdom and the start of the New Kingdom. The concept of a "Second Intermediate Period" was coined in 1942 b ...

. It was a compound with several rooms, including some for the preparation of the clay and one with a 'simple' oven. Some tools were also identified, including probable fragments of a potter's wheel.

* Several kilns have been identified in

Akhenaten

Akhenaten (pronounced ), also spelled Echnaton, Akhenaton, ( egy, ꜣḫ-n-jtn ''ʾŪḫə-nə-yātəy'', , meaning "Effective for the Aten"), was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh reigning or 1351–1334 BC, the tenth ruler of the Eighteenth D ...

's capital city of

Amarna

Amarna (; ar, العمارنة, al-ʿamārnah) is an extensive Egyptian archaeological site containing the remains of what was the capital city of the late Eighteenth Dynasty. The city was established in 1346 BC, built at the direction of the Ph ...

, as well as traces of both industrial and household pottery production.

* Remains of workshops from about the same time as those at Amarna have been found at Harube in north

Sinai. They were located outside the settlement, near the granaries and contained areas for preparing the clay and for kilns. They fulfilled the demand of nearby garrisons and official convoys passing through the area.

Classification and analysis

Various methods have been developed in archaeology for the classification of Egyptian pottery. The most important is called the Vienna system. This system is based on the following terms:

*

Fabric

Textile is an umbrella term that includes various fiber-based materials, including fibers, yarns, filaments, threads, different fabric types, etc. At first, the word "textiles" only referred to woven fabrics. However, weaving is not ...

: this indicates the type of clay, and whether it consists of a combination of types of clay and temper or additives.

* Form: this includes changes to the mixture introduced by the potter, such as temper-additives and surface treatments.

* Ware: this can encompass a number of different styles with the same clay-mixture.

* Fracture/fracturing: this refers to the assessment of the way in which

sherd

In archaeology, a sherd, or more precisely, potsherd, is commonly a historic or prehistoric fragment of pottery

Pottery is the process and the products of forming vessels and other objects with clay and other ceramic materials, which are ...

s break.

The Vienna system

The 'Vienna System' is a classification system for Egyptian pottery, which was developed by Dorothea Arnold,

Manfred Bietak,

Janine Bourriau, Helen and Jean Jacquet and

Hans-Åke Nordström

Hans-Åke Nordström (1933-2022) was a Swedish archaeologist and professor at Uppsala University. His work has included excavations in parts of Nubia, submerged since the construction of the Aswan Dam, and the development of the Vienna System for c ...

at a conference in Vienna in 1980. All of them brought sherds from their own excavations which formed the basis for the classification system, with a few exceptions. As a result, the system is mainly based on find spots of the 'classic' periods and regions of Egypt. According to the group who developed it, the system was only intended as a departure point, a guide for the description of pottery. The classification of the various wares is based on the measurement of the size of the organic and non-organic components of the pottery fabric.

The components are divided into three groups according to their size. Mineral particles like

sand

Sand is a granular material composed of finely divided mineral particles. Sand has various compositions but is defined by its grain size. Sand grains are smaller than gravel and coarser than silt. Sand can also refer to a textural class ...

and

limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms w ...

are classified as fine (60-250

μm

The micrometre ( international spelling as used by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures; SI symbol: μm) or micrometer ( American spelling), also commonly known as a micron, is a unit of length in the International System of Uni ...

), medium (250-500 μm), and large (larger than 500 μm), while

straw

Straw is an agricultural byproduct consisting of the dry stalks of cereal plants after the grain and chaff have been removed. It makes up about half of the yield of cereal crops such as barley, oats, rice, rye and wheat. It has a number ...

is categorised as fine (smaller than 2 mm), medium (2–5 mm), and large (over 5 mm). The meaningfulness of the system is limited somewhat by the caprice of the potter and a degree of accident during manufacture. The system also provides various criteria for the subdivision of Nile clay and marl clay, "thus the marl clay consists of naturally occurring geological groupings, but with Nile clay the different mixtures were created artificially." The system does not take account of surface treatment. The system is only of limited use for predynastic pottery and pottery that post-dates the New Kingdom. This shows the uncertain state of published research on these periods and the large variation in technique, distribution and raw material which occurred in both of these periods.

Nile clay A

The fabric consists of a fine, homogeneous clay and a significant proportion of

loam

Loam (in geology and soil science) is soil composed mostly of sand ( particle size > ), silt (particle size > ), and a smaller amount of clay (particle size < ). By weight, its mineral composition is about 40–40–20% concentration of sand–si ...

. Components are fine sand, a conspicuous amount of medium-grained sand and occasionally large grains of sand.

Mica

Micas ( ) are a group of silicate minerals whose outstanding physical characteristic is that individual mica crystals can easily be split into extremely thin elastic plates. This characteristic is described as perfect basal cleavage. Mica is ...

also occurs. Small amounts of tiny straw particles can occur, but they are not typical of this form. The quantity of clay and loam and the fine particles suggests that the sand is a natural component, not an addition for tempering.

Nile clay B

Nile clay B is subdivided into B1 and B2:

* B1: The fabric is relatively muddy and not as fine as Nile clay A. There is a lot of fine sand, with isolated particles of medium and large grains of sand. Mica particles are common. Isolated fine particles of straw also occur. Surfaces and incisions are often in the original red-brown, but black/gray or black/red areas can occur. This type is common from the Old Kingdom until the beginning of the 18th dynasty. It is the raw material for the spherical bowls and 'cups' of the Middle Kingdom and especially characteristic of the fine wares of the Delta and the region of

Memphis

Memphis most commonly refers to:

* Memphis, Egypt, a former capital of ancient Egypt

* Memphis, Tennessee, a major American city

Memphis may also refer to:

Places United States

* Memphis, Alabama

* Memphis, Florida

* Memphis, Indiana

* Memp ...

-

Fayyum

Faiyum ( ar, الفيوم ' , borrowed from cop, ̀Ⲫⲓⲟⲙ or Ⲫⲓⲱⲙ ' from egy, pꜣ ym "the Sea, Lake") is a city in Middle Egypt. Located southwest of Cairo, in the Faiyum Oasis, it is the capital of the modern Faiyum ...

in that period.

* B2: The fabric is similar to B1, but the mineral and organic components have larger grains and are more frequent. There are large amounts of fine sand and sand grains of medium size are common. Rounded grains of

sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicat ...

occur with limestone grains which show some signs of weathering. The demarcation between B and C is not very clear, especially between B2 and C. One aid in distinguishing them is that sand is the main additive in type B rather than straw. Unlike B1, B2 is common in all periods and regions. For example, Dorothea Arnold identified four varieties of it in

Lisht

Lisht or el-Lisht ( ar, اللشت, translit=Al-Lišt) is an Egyptian village located south of Cairo. It is the site of Middle Kingdom royal and elite burials, including two pyramids built by Amenemhat I and Senusret I. The two main pyramids were ...

-South. Manfred Bietak identified a large-grained variant from the Second Intermediate Period at

Tell El-Dab'a. Other examples include the late 12th and 13th dynasties at

Dahshur

DahshurAlso transliterated ''Dahshour'' (in English often called ''Dashur'' ar, دهشور ' , ''Dahchur'') is a royal necropolis located in the desert on the west bank of the Nile approximately south of Cairo. It is known chiefly for several p ...

and the late 18th dynasty at

Karnak

The Karnak Temple Complex, commonly known as Karnak (, which was originally derived from ar, خورنق ''Khurnaq'' "fortified village"), comprises a vast mix of decayed temples, pylons, chapels, and other buildings near Luxor, Egypt. Constru ...

.

File:Nile-b2-001.jpg, Nile clay B

File:Nile-b2-002.jpg, Nile clay B

File:Nile-b2-003.jpg, Nile clay B

Nile clay C

This material consists of muddy clay with rough or smooth grains of sand which can vary from fine to large and in frequency from seldom to often. Additives like limestone and other minerals, such as mica, crushed sherds of pottery and medium-grained stone particles, can occur. Straw is the dominant additive and is often visible in incisions and on the surface. These straw particles range from fine to large, with a large amount of large particles (over 5 mm). The straw is preserved as charred particles, appearing as white or grey

silica

Silicon dioxide, also known as silica, is an oxide of silicon with the chemical formula , most commonly found in nature as quartz and in various living organisms. In many parts of the world, silica is the major constituent of sand. Silica is ...

and as impressions in the paste. Nile clay C occurs in all periods and regions, and includes a wide variety of variants.

File:Nile-c1.jpg, Nile clay C1

File:Nile-c2.jpg, Nile clay C2

Nile clay D

The main sign of Nile clay D is the conspicuous quantity of limestone, which might be either a natural component or a tempering additive. Without this visible limestone component, this type of clay would be classified differently, as Nile clay A (at Tell el-Dab'a), lightly fired Nile clay B (at Dahshur), or as Nile clay B2 - C (at Memphis).

Nile clay E

This clay consists of a large amount of rounded sand particles, ranging from fine to large grains, which are clearly visible on the surface and in fractures. Aside from these diagnostic components, the fabric can look characteristic of Nile clay B or Nile clay C. Nile clay E has so far only been identified in a few locations: in the eastern Delta (Tell el-Dab’a and

Qantir

Qantir () is a village in Egypt. Qantir

is believed to mark what was probably the ancient site of the 19th Dynasty Pharaoh Ramesses II's capital, Pi-Ramesses or Per-Ramesses ("House or Domain of Ramesses"). It is situated around north of Faqous ...

) and the region of Memphis and the southern Fayyum.

File:Nile-e1.jpg, Nile clay E1

File:Nile-e2.jpg, Nile clay E2

Marl clay A

This group is divided into four variants. The shared characteristics of Marl clay A are its compact and homogeneous fabric, the fine mineral components and very low proportion of organic substances.

* Marl clay A1: The fabric consists of a relatively fine and homogeneous clay, tempered with visible particles of fine-to-medium grained limestone. This is the most visible aspect in fractures and outer surfaces. The particles are sharp and vary in size from 60 to 400 μm, with occasional larger particles. Fine sand and dark mica particles are common. Organic additives (straw) occur occasionally. This clay was common from Naqada II to the Old Kingdom and is one of the fabrics of Meidum ware.

[H.-Å. Nordström, J. Bourriau: ''Ceramic Technology: Clays and Fabrics.'' Mainz 1993, p. 176.]

* Marl clay A2: In this variant, the mineral additives are very fine and homogeneously distributed through the paste. Fine sand and limestone particles are present but do not dominate. Dark mica particles are present in small quantities. Marl clay A2 occurred from the Middle Kingdom, but is most common between the late Second Intermediate period and the 18th dynasty, mainly in Upper Egypt.

* Marl clay A3: This clay looks the most similar to modern Qena clay, although we cannot be sure that it came from this same region. A few mineral additives are visible under magnification in fractures and there is little sign that these were added as temper. The past is extraordinarily fine and homogeneous, which could indicate careful preparation of the clay, probably with a mortar. Occasionally, straw particles occur. This fabric occurs from the early Middle Kingdom into the New Kingdom, and seems to stem from Upper Egypt. On the other hand, it only rarely occurs in the eastern Delta (Tell el-Dab'a and Qantir) and the Memphis-Fayyum region.

* Marl clay A4: Of all the variants of Marl clay A, this has the greatest mix and quantity of fine and large sand particles. Mica particles and (often) straw particles can also occur. This clay already occurred in the Middle Kingdom, but is most common in the New Kingdom (Amarna,

Malqata

Malkata (or Malqata; ar, الملقطة, lit=the place where things are picked up), is the site of an Ancient Egyptian palace complex built during the New Kingdom, by the 18th Dynasty pharaoh Amenhotep III. It is located on the West Bank of the ...

, Memphis,

Saqqara

Saqqara ( ar, سقارة, ), also spelled Sakkara or Saccara in English , is an Egyptian village in Giza Governorate, that contains ancient burial grounds of Egyptian royalty, serving as the necropolis for the ancient Egyptian capital, Memph ...

, etc.).

Marl clay B

The fabric is homogeneous and very thick. The diagnostic feature of the fabric is its high sand content, which makes up roughly 40% of the paste and was added as temper. The particles range from angular to vaguely rounded and from fine to large. As in Marl clay A4, limestone additives are visible under magnification, appearing as a calcareous material in the clay's fabric at 45x magnification. Marl clay B was mainly used for large and mid-sized vessels and seems to be very restricted in space and time, to the Second Intermediate period and New Kingdom in Upper Egypt.

Marl clay C

This group is divided into three types. The shared feature of all three is the presence of numerous limestone particles, more or less ground down, which range from medium to large in size, and give the material a sparkly appearance. The fabric itself is fine and thick. Fine and medium sand particles, added as temper, are also encountered, as well as light and dark mica.

* Marl clay C1: This variant is defined by the presence of fine to medium ground particles of limestone. Fractures are almost always composed of different zones, each of which are red with a gray or black core and show many signs of prefatory glazing.

* Marl clay C2: Most of the limestone particles remain intact and fractures do not have zones, but a uniform colour which ranges from red (

Munsell 10R 4/6) to brown (Munsell 5YR 6/6). Another distinction from C1 is the sand temper: in C2 the proportion of sand is larger than that of limestone.

* Marl clay C compact: This clay has much less sand than C1 and C2 and is much thicker. This variant has thus far only been found in a single type of ware - large, egg-shaped flasks with grooved necks.

Marl clay D