Anarchism in the United States on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

For anarchist historian Eunice Minette Schuster,

For anarchist historian Eunice Minette Schuster,

"The culture of individualist anarchist in Late-nineteenth century America"

. an influential individualist anarchist publication of

What do anarchists want from us?

, '' Slate.com'' ''The Peaceful Revolutionist'', the four-page weekly paper Warren edited during 1833, was the first anarchist periodical published, an enterprise for which he built his own printing press, cast his own type and made his own printing plates. After New Harmony failed, Warren shifted his ideological loyalties from socialism to anarchism which anarchist Peter Sabatini described as "no great leap, given that Owen's socialism had been predicated on Godwin's anarchism". The emergence and growth of anarchism in the United States in the 1820s and 1830s has a close parallel in the simultaneous emergence and growth of

pg. 42

"LA INSUMISIÓN VOLUNTARIA. EL ANARQUISMO INDIVIDUALISTA ESPAÑOL DURANTE LA DICTADURA Y LA SEGUNDA REPÚBLICA (1923–1938)" by Xavier Diez

"Many have seen in Thoreau one of the precursors of ecologism and For American anarchist historian Eunice Minette Schuster, " is apparent ..that Proudhonian Anarchism was to be found in the United States at least as early as 1848 and that it was not conscious of its affinity to the Individualist Anarchism of Josiah Warren and Stephen Pearl Andrews. .. William B. Greene presented this Proudhonian Mutualism in its purest and most systematic form". William Batchelder Greene was a 19th-century mutualist,

For American anarchist historian Eunice Minette Schuster, " is apparent ..that Proudhonian Anarchism was to be found in the United States at least as early as 1848 and that it was not conscious of its affinity to the Individualist Anarchism of Josiah Warren and Stephen Pearl Andrews. .. William B. Greene presented this Proudhonian Mutualism in its purest and most systematic form". William Batchelder Greene was a 19th-century mutualist,

An important current within American individualist anarchism was Free love. Free love advocates sometimes traced their roots back to Josiah Warren and to experimental communities, and viewed sexual freedom as a clear, direct expression of an individual's self-ownership. Free love particularly stressed

An important current within American individualist anarchism was Free love. Free love advocates sometimes traced their roots back to Josiah Warren and to experimental communities, and viewed sexual freedom as a clear, direct expression of an individual's self-ownership. Free love particularly stressed  Heywood's philosophy was instrumental in furthering individualist anarchist ideas through his extensive pamphleteering and reprinting of works of Josiah Warren, author of ''True Civilization'' (1869), and William B. Greene. At a 1872 convention of the New England Labor Reform League in Boston, Heywood introduced Greene and Warren to eventual ''Liberty'' publisher Benjamin Tucker. Heywood saw what he believed to be a disproportionate concentration of capital in the hands of a few as the result of a selective extension of government-backed privileges to certain individuals and organizations. ''The Word'' was an individualist anarchist free love magazine edited by Ezra Heywood and Angela Heywood, issued first from

Heywood's philosophy was instrumental in furthering individualist anarchist ideas through his extensive pamphleteering and reprinting of works of Josiah Warren, author of ''True Civilization'' (1869), and William B. Greene. At a 1872 convention of the New England Labor Reform League in Boston, Heywood introduced Greene and Warren to eventual ''Liberty'' publisher Benjamin Tucker. Heywood saw what he believed to be a disproportionate concentration of capital in the hands of a few as the result of a selective extension of government-backed privileges to certain individuals and organizations. ''The Word'' was an individualist anarchist free love magazine edited by Ezra Heywood and Angela Heywood, issued first from  Individualist anarchism found in the United States an important space of discussion and development within what is known as the Boston anarchists. Even among the 19th-century American individualists, there was not a monolithic doctrine, as they disagreed amongst each other on various issues including

Individualist anarchism found in the United States an important space of discussion and development within what is known as the Boston anarchists. Even among the 19th-century American individualists, there was not a monolithic doctrine, as they disagreed amongst each other on various issues including  ''

'' Some of the American individualist anarchists later in this era such as Benjamin Tucker abandoned natural rights positions and converted to Max Stirner's

Some of the American individualist anarchists later in this era such as Benjamin Tucker abandoned natural rights positions and converted to Max Stirner's

by

By the 1880s anarcho-communism was already present in the United States as can be seen in the publication of the journal ''Freedom: A Revolutionary Anarchist-Communist Monthly'' by

By the 1880s anarcho-communism was already present in the United States as can be seen in the publication of the journal ''Freedom: A Revolutionary Anarchist-Communist Monthly'' by

at the Lucy Parsons Center Lucy Parsons debated in her time in the US with fellow anarcha-communist A gifted orator, Most propagated these ideas throughout Marxist and anarchist circles in the United States and attracted many adherents, most notably Emma Goldman and

A gifted orator, Most propagated these ideas throughout Marxist and anarchist circles in the United States and attracted many adherents, most notably Emma Goldman and  Emma Goldman was an anarchist known for her political activism, writing, and speeches. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europe in the first half of the 20th century. Born in

Emma Goldman was an anarchist known for her political activism, writing, and speeches. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europe in the first half of the 20th century. Born in

Biography of Emma Goldman

. UIC Library Emma Goldman Collection. Retrieved on December 13, 2008. Attracted to anarchism after the Haymarket affair, Goldman became a writer and a renowned lecturer on anarchist philosophy, women's rights, and social issues, attracting crowds of thousands. She and anarchist writer Alexander Berkman, her lover and lifelong friend, planned to assassinate industrialist and financier Henry Clay Frick as an act of propaganda of the deed. Although Frick survived the attempt on his life, Berkman was sentenced to twenty-two years in prison. Goldman was imprisoned several times in the years that followed, for "inciting to riot" and illegally distributing information about

The anti-authoritarian sections of the First International were the precursors of the anarcho-syndicalists, seeking to "replace the privilege and authority of the State" with the "free and spontaneous organization of labor."

After embracing anarchism Albert Parsons, husband of Lucy Parsons, turned his activity to the growing movement to establish the 8-hour day. In January 1880, the Eight-Hour League of Chicago sent Parsons to a national conference in Washington, D.C., a gathering which launched a national lobbying movement aimed at coordinating efforts of labor organizations to win and enforce the 8-hour workday. In the fall of 1884, Parsons launched a weekly

The anti-authoritarian sections of the First International were the precursors of the anarcho-syndicalists, seeking to "replace the privilege and authority of the State" with the "free and spontaneous organization of labor."

After embracing anarchism Albert Parsons, husband of Lucy Parsons, turned his activity to the growing movement to establish the 8-hour day. In January 1880, the Eight-Hour League of Chicago sent Parsons to a national conference in Washington, D.C., a gathering which launched a national lobbying movement aimed at coordinating efforts of labor organizations to win and enforce the 8-hour workday. In the fall of 1884, Parsons launched a weekly  Two individualist anarchists who wrote in Benjamin Tucker's ''Liberty'' were also important labor organizers of the time. Jo Labadie was an American labor organizer, individualist anarchist, social activist, printer, publisher, essayist, and poet. Without the oppression of the state, Labadie believed, humans would choose to harmonize with "the great natural laws ... without robbing

Two individualist anarchists who wrote in Benjamin Tucker's ''Liberty'' were also important labor organizers of the time. Jo Labadie was an American labor organizer, individualist anarchist, social activist, printer, publisher, essayist, and poet. Without the oppression of the state, Labadie believed, humans would choose to harmonize with "the great natural laws ... without robbing

Preface

Frustration with abolitionism, spiritualism, and labor reform caused Lum to embrace anarchism and radicalize workers, as he came to believe that revolution would inevitably involve a violent struggle between the working class and the employing class. Convinced of the necessity of violence to enact social change he volunteered to fight in the American Civil War, hoping thereby to bring about the end of slavery. The ''

Italian anti-organizationalist individualist anarchism was brought to the United States"it was in times of severe social repression and deadening social quiescence that individualist anarchists came to the foreground of libertarian activity – and then primarily as terrorists. In France, Spain, and the United States, individualistic anarchists committed acts of terrorism that gave anarchism its reputation as a violently sinister conspiracy.

Italian anti-organizationalist individualist anarchism was brought to the United States"it was in times of severe social repression and deadening social quiescence that individualist anarchists came to the foreground of libertarian activity – and then primarily as terrorists. In France, Spain, and the United States, individualistic anarchists committed acts of terrorism that gave anarchism its reputation as a violently sinister conspiracy.

Emma Goldman was arrested on suspicion of being involved in the assassination, but was released due to insufficient evidence. She later incurred a great deal of negative publicity when she published "The Tragedy at Buffalo". In the article, she compared Czolgosz to Sacco and Vanzetti were suspected anarchists who were convicted of murdering two men during the 1920

Sacco and Vanzetti were suspected anarchists who were convicted of murdering two men during the 1920  Ross Winn was an American

Ross Winn was an American

An American anarcho-pacifist current developed in this period as well as a related

An American anarcho-pacifist current developed in this period as well as a related

,

John Cage at Seventy: An Interview

by Stephen Montague. ''American Music'', Summer 1985. Ubu.com. Accessed May 24, 2007. Paul Goodman was an American sociologist, poet, writer, anarchist, and public intellectual. Goodman is now mainly remembered as the author of '' Growing Up Absurd'' (1960) and an activist on the Anarchism proved to be influential also in the early environmentalist movement in the United States. Leopold Kohr (1909–1994) was an

Anarchism proved to be influential also in the early environmentalist movement in the United States. Leopold Kohr (1909–1994) was an  The Libertarian League was founded in New York City in 1954 as a political organization building on the Libertarian Book Club. Members included Sam Dolgoff, Russell Blackwell, Dave Van Ronk, Enrico Arrigoni and Murray Bookchin. Its central principle, stated in its journal ''Views and Comments'', was "equal freedom for all in a free socialist society". Branches of the League opened in a number of other American cities, including Detroit and San Francisco. It was dissolved at the end of the 1960s. Sam Dolgoff (1902–1990) was a Russian American anarchist and anarcho-syndicalist. After being expelled from the Young People's Socialist League (1907), Young People's Socialist League, Dolgoff joined the

The Libertarian League was founded in New York City in 1954 as a political organization building on the Libertarian Book Club. Members included Sam Dolgoff, Russell Blackwell, Dave Van Ronk, Enrico Arrigoni and Murray Bookchin. Its central principle, stated in its journal ''Views and Comments'', was "equal freedom for all in a free socialist society". Branches of the League opened in a number of other American cities, including Detroit and San Francisco. It was dissolved at the end of the 1960s. Sam Dolgoff (1902–1990) was a Russian American anarchist and anarcho-syndicalist. After being expelled from the Young People's Socialist League (1907), Young People's Socialist League, Dolgoff joined the

Andrew Cornell reports that " Sam Dolgoff and others worked to revitalize the

Andrew Cornell reports that " Sam Dolgoff and others worked to revitalize the  Anarchists became more visible in the 1980s, as a result of publishing, protests and conventions. In 1980, the First International Symposium on Anarchism was held in Portland, Oregon. In 1986, the Haymarket Remembered conference was held in Chicago, to observe the centennial of the infamous Haymarket Riot. This conference was followed by annual, continental conventions in Minneapolis (1987), Toronto (1988), and San Francisco (1989). Recently there has been a resurgence in anarchist ideals in the United States.Sean Sheehan Published 2004 Reaktion Book

Anarchists became more visible in the 1980s, as a result of publishing, protests and conventions. In 1980, the First International Symposium on Anarchism was held in Portland, Oregon. In 1986, the Haymarket Remembered conference was held in Chicago, to observe the centennial of the infamous Haymarket Riot. This conference was followed by annual, continental conventions in Minneapolis (1987), Toronto (1988), and San Francisco (1989). Recently there has been a resurgence in anarchist ideals in the United States.Sean Sheehan Published 2004 Reaktion Book

Anarchism

175 pages In the 1980s anarchism became linked with squatting and social centers such as ABC No Rio and C-Squat in New York City. The Institute for Anarchist Studies is a non-profit organization founded by Chuck W. Morse following the anarchist-communist school of thought, in 1996 to assist anarchist writers and further develop the theoretical aspects of the anarchist movement. In 1984 Workers Solidarity Alliance was founded as an anarcho-syndicalist political organization which published

Ideas and Action

' and was at one time affiliated to the IWA–AIT, International Workers Association (IWA-AIT), an international federation of anarcho-syndicalist unions and groups. In the late 1980s, started as a newspaper and in 1991 expanded into a continental federation. It brought new ideas to the movement's mainstream, such as white privilege, and new people, including anti-imperialists and former members of the Trotskyist Revolutionary Socialist League (U.S.), Revolutionary Socialist League. It collapsed in 1998 amid disagreements about the organization's racial justice tenets and the viability of anarchism. Love and Rage involved hundreds of activists across the country at its peak and included a section based in Mexico City, Amor Y Rabia, which published a newspaper of the same name. Contemporary anarchism, with its shift in focus from class-based oppression to all forms of oppression, began to address race-based oppression in earnest in the 1990s with Black anarchists Lorenzo Ervin and Kuwasi Balagoon, the journal ''Race Traitor (journal), Race Traitor'', and movement-building organizations including Love and Rage, , , and . In the mid-1990s, an insurrectionary anarchist tendency also emerged in the United States mainly absorbing southern European influences."Insurrectionary anarchism has been developing in the English language anarchist movement since the 1980s, thanks to translations and writings by Jean Weir in her "Elephant Editions" and her magazine "Insurrection". .. In Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, local comrades involved in the Anarchist Black Cross, the local anarchist social center, and the magazines "No Picnic" and "Endless Struggle" were influenced by Jean's projects, and this carried over into the always developing practice of insurrectionary anarchists in this region today ... The anarchist magazine "Demolition Derby" in Montreal also covered some insurrectionary anarchist news back in the day"

"Anarchism, insurrections and insurrectionalism" by Joe Black

CrimethInc., is a decentralized anarchist collective of autonomous Clandestine cell system, cells.* CrimethInc. emerged during this period initially as the hardcore punk zine ''Inside Front'', and began operating as a collective in 1996. It has since published widely read articles and zines for the anarchist movement and distributed posters and books of its own publication. CrimethInc. cells have published books, released records and organized national campaigns against globalization and representative democracy in favor of radical community organizing. American anarchists increasingly became noticeable at protests, especially through a tactic known as the Black bloc. U.S. anarchists became more prominent as a result of the WTO Ministerial Conference of 1999 protest activity, anti-WTO protests in Seattle. Common Struggle – Libertarian Communist Federation or Lucha Común – Federación Comunista Libertaria (formerly the North Eastern Federation of Anarchist Communists (NEFAC) or the Fédération des Communistes Libertaires du Nord-Est) was a platformism, platformist/Anarchist communism, anarchist communist organization based in the northeast region of the United States which was founded in 2000 at a conference in Boston following the 1999 World Trade Organization protests in Seattle. Following months of discussion between former Atlantic Anarchist Circle affiliates and ex-Love and Rage members in the United States and ex-members of the Demanarchie newspaper collective in Quebec City. Founded as a bi-lingual French and English-speaking federation with member and supporter groups in the northeast of the United States, southern Ontario and the Quebec province, the organization later split up in 2008. The Québécoise membership reformed as the Union Communiste Libertaire (UCL) and the American membership retained the name NEFAC, before changing its name to Common Struggle in 2011 before merging into Black Rose Anarchist Federation. Former members based in Toronto went on to help found an Ontario-based platformist organization known as Common Cause. The Green Mountain Anarchist Collective, which a local affiliate of NEFAC following Seattle, supported leftist causes in Vermont such as unionization, the living wage campaign, and access to social services. In the wake of Hurricane Katrina, anarchist activists were visible as founding members of the Common Ground Collective. Anarchists also had an early role in the Occupy movement. In November 2011, ''Rolling Stone'' magazine credited American anarchist and scholar David Graeber with giving the Occupy Wall Street movement its theme: "We are the 99 percent". ''Rolling Stone'' reported that Graeber helped create the first New York City General Assembly, with only 60 participants, on August 2, 2011. He spent the next six weeks involved with the burgeoning movement, including facilitating general assemblies, attending working group meetings, and organizing legal and medical training and classes on nonviolent resistance. Following the Occupy Wall Street movement, author Mark Bray wrote ''Translating Anarchy: The Anarchism of Occupy Wall Street'', which gave a first hand account of anarchist involvement. In the period before and after the Occupy movement several new organizations and efforts became active. A series invitational conferences called the Class Struggle Anarchist Conference, initiated by Workers Solidarity Alliance and joined by others, aimed to bring together a number of local and regional based anarchist organizations. The conference was first held in New York City in 2008 and brought together hundreds of activists and subsequent conferences were held in Detroit in 2009, Seattle in 2010 and Buffalo in 2012. One group that was founded during this period was May First Anarchist Alliance in 2011 with members in Michigan and Minnesota which defines itself as having a working class orientation and promoting a non-doctrinaire anarchism. Another group founded during this period is Black Rose Anarchist Federation (BRRN) in 2013 which combined a number of local and regional groups including Common Struggle, formerly known as the Northeastern Federation of Anarchist Communists (NEFAC), Four Star Anarchist Organization in Chicago, Miami Autonomy and Solidarity, Rochester Red and Black, and Wild Rose Collective based in Iowa City. Some individual members of the Workers Solidarity Alliance joined the new group but the organization voted to remain separate. The group has a variety of influences, most notably anarcho-communism,

In the period before and after the Occupy movement several new organizations and efforts became active. A series invitational conferences called the Class Struggle Anarchist Conference, initiated by Workers Solidarity Alliance and joined by others, aimed to bring together a number of local and regional based anarchist organizations. The conference was first held in New York City in 2008 and brought together hundreds of activists and subsequent conferences were held in Detroit in 2009, Seattle in 2010 and Buffalo in 2012. One group that was founded during this period was May First Anarchist Alliance in 2011 with members in Michigan and Minnesota which defines itself as having a working class orientation and promoting a non-doctrinaire anarchism. Another group founded during this period is Black Rose Anarchist Federation (BRRN) in 2013 which combined a number of local and regional groups including Common Struggle, formerly known as the Northeastern Federation of Anarchist Communists (NEFAC), Four Star Anarchist Organization in Chicago, Miami Autonomy and Solidarity, Rochester Red and Black, and Wild Rose Collective based in Iowa City. Some individual members of the Workers Solidarity Alliance joined the new group but the organization voted to remain separate. The group has a variety of influences, most notably anarcho-communism,

"A new anarchism emerges, 1940–1954"

. * Andrew Cornell

"Anarchism and the Movement for a New Society: Direct Action and Prefigurative Community in the 1970s and 80s."

Perspectives 2009. Institute for Anarchist Studies. * * James J. Martin]

''Men Against the State: the State the Expositors of Individualist Anarchism''

The Adrian Allen Associates, Dekalb, Illinois, 1953. * Eunice Minette Schuster

* Jessica Moran.

The Firebrand and the Forging of a New Anarchism: Anarchist Communism and Free Love

". * Max Nettlau, ''A Short History of Anarchism.'' Freedom Press, 1996. * William O. Reichert, ''Partisans of Freedom: A Study in American Anarchism''. Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1976. * Rudolf Rocker, Rocker, Rudolf. ''Pioneers of American Freedom: Origin of Liberal and Radical Thought in America''. Rocker Publishing Committee. 1949. * Steve J. Shone.

American Anarchism

.'' Brill. Leiden and Boston. 2013. * Kenyon Zimmer, ''Immigrants Against the State: Yiddish and Italian Anarchism in America.'' Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2015.

Anarchy: A Journal of Desire Armed

Black Rose Anarchist Federation (BRRN)

Common Ground Collective

First of May Anarchist Alliance

Institute for Anarchist Studies

Workers Solidarity Alliance

{{Portal bar, Anarchism, United States Anarchism in the United States, 1820s establishments in the United States Anarchism by country, United States Left-wing politics in the United States Political movements in the United States

Anarchism

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not neces ...

in the United States began in the mid-19th century and started to grow in influence as it entered the American labor movements, growing an anarcho-communist

Anarcho-communism, also known as anarchist communism, (or, colloquially, ''ancom'' or ''ancomm'') is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private property but retains resp ...

current as well as gaining notoriety for violent propaganda of the deed

Propaganda of the deed (or propaganda by the deed, from the French ) is specific political direct action meant to be exemplary to others and serve as a catalyst for revolution.

It is primarily associated with acts of violence perpetrated by pro ...

and campaigning for diverse social reform

A reform movement or reformism is a type of social movement that aims to bring a social or also a political system closer to the community's ideal. A reform movement is distinguished from more radical social movements such as revolutionary mov ...

s in the early 20th century. By around the start of the 20th century, the heyday of individualist anarchism had passed and anarcho-communism and other social anarchist currents emerged as the dominant anarchist tendency. Social anarchists, like Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman (June 27, 1869 – May 14, 1940) was a Russian-born anarchist political activist and writer. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europe in the first half of the ...

, can be credited with the introduction of LGBTQ social movements

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) movements are social movements that advocate for LGBT people in society. Some focus on equal rights, such as the ongoing movement for same-sex marriage, while others focus on liberation, as in th ...

to the United States.

In the post-World War II

The aftermath of World War II was the beginning of a new era started in late 1945 (when World War II ended) for all countries involved, defined by the decline of all colonial empires and simultaneous rise of two superpowers; the Soviet Union (US ...

era, anarchism regained influence through new developments such as anarcho-pacifism, the American New Left and the counterculture of the 1960s

The counterculture of the 1960s was an anti-establishment cultural phenomenon that developed throughout much of the Western world in the 1960s and has been ongoing to the present day. The aggregate movement gained momentum as the civil rights mo ...

. Contemporary anarchism in the United States influenced and became influenced and renewed by developments both inside and outside the worldwide anarchist movement such as platformism

Platformism is a form of anarchist organization that seeks unity from its participants, having as a defining characteristic the idea that each platformist organization should include only people that are fully in agreement with core group ideas, r ...

, insurrectionary anarchism

Insurrectionary anarchism is a revolutionary theory and tendency within the anarchist movement that emphasizes insurrection as a revolutionary practice. It is critical of formal organizations such as labor unions and federations that are base ...

, the new social movements (anarcha-feminism

Anarcha-feminism, also referred to as anarchist feminism, is a system of analysis which combines the principles and power analysis of anarchist theory with feminism. Anarcha-feminism closely resembles intersectional feminism. Anarcha-feminism ...

, queer anarchism and green anarchism

Green anarchism (or eco-anarchism"green anarchism (also called eco-anarchism)" in '' An Anarchist FAQ'' by various authors.) is an anarchist school of thought that puts a particular emphasis on ecology and environmental issues. A green anarchi ...

) and the alter-globalization

Alter-globalization (also known as alternative globalization or alter-mundialization—from the French alter- mondialisation—and overlapping with the global justice movement) is a social movement whose proponents support global cooperation and ...

movements. Within contemporary anarchism, the anti-capitalism of classical anarchism

The history of anarchism is as ambiguous as anarchism itself. Scholars find it hard to define or agree on what anarchism means, which makes outlining its history difficult. There is a range of views on anarchism and its history. Some feel anar ...

has remained prominent.

Around the turn of the 21st century, anarchism grew in popularity and influence as part of the anti-war

An anti-war movement (also ''antiwar'') is a social movement, usually in opposition to a particular nation's decision to start or carry on an armed conflict, unconditional of a maybe-existing just cause. The term anti-war can also refer to p ...

, anti-capitalist

Anti-capitalism is a political ideology and movement encompassing a variety of attitudes and ideas that oppose capitalism. In this sense, anti-capitalists are those who wish to replace capitalism with another type of economic system, such as so ...

and anti-globalization

The anti-globalization movement or counter-globalization movement, is a social movement critical of economic globalization. The movement is also commonly referred to as the global justice movement, alter-globalization movement, anti-globalist m ...

movements. Anarchists became known for their involvement in protests against the meetings of the WTO, G8 and the World Economic Forum

The World Economic Forum (WEF) is an international non-governmental and lobbying organisation based in Cologny, canton of Geneva, Switzerland. It was founded on 24 January 1971 by German engineer and economist Klaus Schwab. The foundation, ...

. Some anarchist factions at these protests engaged in rioting, property destruction and violent confrontations with the police. These actions were precipitated by ''ad hoc

Ad hoc is a Latin phrase meaning literally 'to this'. In English, it typically signifies a solution for a specific purpose, problem, or task rather than a generalized solution adaptable to collateral instances. (Compare with ''a priori''.)

Com ...

'', leaderless and anonymous cadres known as black blocs, although other peaceful organizational tactics pioneered in this time include affinity groups, security culture and the use of decentralized technologies such as the Internet

The Internet (or internet) is the global system of interconnected computer networks that uses the Internet protocol suite (TCP/IP) to communicate between networks and devices. It is a '' network of networks'' that consists of private, p ...

. A significant event of this period was the 1999 Seattle WTO protests.

History

Early anarchism

For anarchist historian Eunice Minette Schuster,

For anarchist historian Eunice Minette Schuster, American individualist anarchism

Individualist anarchism in the United States was strongly influenced by Benjamin Tucker, Josiah Warren, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Lysander Spooner, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Max Stirner, Herbert Spencer and Henry David Thoreau. Other important individ ...

"stresses the isolation of the individual—his right to his own tools, his mind, his body, and to the products of his labor. To the artist who embraces this philosophy it is 'aesthetic

Aesthetics, or esthetics, is a branch of philosophy that deals with the nature of beauty and taste, as well as the philosophy of art (its own area of philosophy that comes out of aesthetics). It examines aesthetic values, often expressed t ...

' anarchism, to the reformer, ethical anarchism, to the independent mechanic, economic anarchism. The former is concerned with philosophy, the latter with practical demonstration. The economic anarchist is concerned with constructing a society on the basis of anarchism. Economically he sees no harm whatever in the private possession of what the individual produces by his own labor, but only so much and no more. The aesthetic and ethical type found expression in the transcendentalism

Transcendentalism is a philosophical movement that developed in the late 1820s and 1830s in New England. "Transcendentalism is an American literary, political, and philosophical movement of the early nineteenth century, centered around Ralph Wald ...

, humanitarianism

Humanitarianism is an active belief in the value of human life, whereby humans practice benevolent treatment and provide assistance to other humans to reduce suffering and improve the conditions of humanity for moral, altruistic, and emotional ...

, and romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

of the first part of the nineteenth century, the economic type in the pioneer life of the West during the same period, but more favorably after the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

". It is for this reason that it has been suggested that in order to understand American individualist anarchism one must take into account "the social context of their ideas, namely the transformation of America from a pre-capitalist to a capitalist society, ..the non-capitalist nature of the early U.S. can be seen from the early dominance of self-employment (artisan and peasant production). At the beginning of the 19th century, around 80% of the working (non-slave) male population were self-employed. The great majority of Americans during this time were farmers working their own land, primarily for their own needs" and so "individualist anarchism is clearly a form of artisan

An artisan (from french: artisan, it, artigiano) is a skilled craft worker who makes or creates material objects partly or entirely by hand. These objects may be functional or strictly decorative, for example furniture, decorative art ...

al socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes th ...

..while communist anarchism and anarcho-syndicalism

Anarcho-syndicalism is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that views revolutionary industrial unionism or syndicalism as a method for workers in capitalist society to gain control of an economy and thus control influence in ...

are forms of industrial (or proletarian

The proletariat (; ) is the social class of wage-earners, those members of a society whose only possession of significant economic value is their labour power (their capacity to work). A member of such a class is a proletarian. Marxist philoso ...

) socialism".

Historian Wendy McElroy

Wendy McElroy (born 1951) is a Canadian individualist feminist and voluntaryist writer. She was a co-founder along with Carl Watner and George H. Smith of ''The Voluntaryist'' magazine in 1982 and is the author of a number of books. McElroy ...

reports that American individualist anarchism received an important influence of three European thinkers. According to McElroy, " e of the most important of these influences was the French political philosopher Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (, , ; 15 January 1809, Besançon – 19 January 1865, Paris) was a French socialist,Landauer, Carl; Landauer, Hilde Stein; Valkenier, Elizabeth Kridl (1979) 959 "The Three Anticapitalistic Movements". ''European Socia ...

, whose words "Liberty is not the Daughter But the Mother of Order" appeared as a motto on ''Liberty

Liberty is the ability to do as one pleases, or a right or immunity enjoyed by prescription or by grant (i.e. privilege). It is a synonym for the word freedom.

In modern politics, liberty is understood as the state of being free within society fr ...

'' masthead",Wendy McElroy

Wendy McElroy (born 1951) is a Canadian individualist feminist and voluntaryist writer. She was a co-founder along with Carl Watner and George H. Smith of ''The Voluntaryist'' magazine in 1982 and is the author of a number of books. McElroy ...

"The culture of individualist anarchist in Late-nineteenth century America"

. an influential individualist anarchist publication of

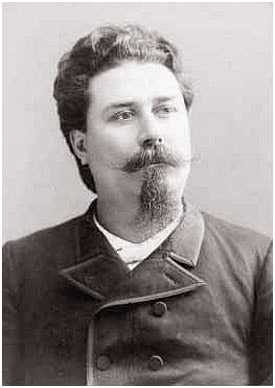

Benjamin Tucker

Benjamin Ricketson Tucker (; April 17, 1854 – June 22, 1939) was an American individualist anarchist and libertarian socialist.Martin, James J. (1953)''Men Against the State: The Expositers of Individualist Anarchism in America, 1827–1908''< ...

. McElroy further stated that " other major foreign influence was the German philosopher Max Stirner

Johann Kaspar Schmidt (25 October 1806 – 26 June 1856), known professionally as Max Stirner, was a German post-Hegelian philosopher, dealing mainly with the Hegelian notion of social alienation and self-consciousness. Stirner is often seen a ...

. The third foreign thinker with great impact was the British philosopher Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer (27 April 1820 – 8 December 1903) was an English philosopher, psychologist, biologist, anthropologist, and sociologist famous for his hypothesis of social Darwinism. Spencer originated the expression " survival of the f ...

". Other influences to consider include William Godwin

William Godwin (3 March 1756 – 7 April 1836) was an English journalist, political philosophy, political philosopher and novelist. He is considered one of the first exponents of utilitarianism and the first modern proponent of anarchism. God ...

's anarchism which "exerted an ideological influence on some of this, but more so the socialism of Robert Owen

Robert Owen (; 14 May 1771 – 17 November 1858) was a Welsh people, Welsh textile manufacturer, philanthropist and social reformer, and a founder of utopian socialism and the cooperative movement. He strove to improve factory working conditio ...

and Charles Fourier

François Marie Charles Fourier (;; 7 April 1772 – 10 October 1837) was a French philosopher, an influential early socialist thinker and one of the founders of utopian socialism. Some of Fourier's social and moral views, held to be radical ...

. After success of his British venture, Owen himself established a cooperative community within the United States at New Harmony, Indiana

New Harmony is a historic town on the Wabash River in Harmony Township, Posey County, Indiana. It lies north of Mount Vernon, the county seat, and is part of the Evansville metropolitan area. The town's population was 789 at the 2010 census. ...

during 1825. One member of this commune was Josiah Warren

Josiah Warren (; 1798–1874) was an American utopian socialist, American individualist anarchist, individualist philosopher, polymath, social reformer, inventor, musician, printer and author. He is regarded by anarchist historians like Jam ...

, considered to be the first individualist anarchist.Palmer, Brian (2010-12-29What do anarchists want from us?

, '' Slate.com'' ''The Peaceful Revolutionist'', the four-page weekly paper Warren edited during 1833, was the first anarchist periodical published, an enterprise for which he built his own printing press, cast his own type and made his own printing plates. After New Harmony failed, Warren shifted his ideological loyalties from socialism to anarchism which anarchist Peter Sabatini described as "no great leap, given that Owen's socialism had been predicated on Godwin's anarchism". The emergence and growth of anarchism in the United States in the 1820s and 1830s has a close parallel in the simultaneous emergence and growth of

abolitionism

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

as no one needed anarchy more than a slave. Warren termed the phrase " cost the limit of price", with "cost" here referring not to monetary price paid but the labor one exerted to produce an item. Therefore, " proposed a system to pay people with certificates indicating how many hours of work they did. They could exchange the notes at local time stores for goods that took the same amount of time to produce". He put his theories to the test by establishing an experimental "labor for labor store" called the Cincinnati Time Store, where trade was facilitated by notes backed by a promise to perform labor. The store proved successful and operated for three years after which it was closed so that Warren could pursue establishing colonies based on mutualism. These included Utopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imaginary community or society that possesses highly desirable or nearly perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book '' Utopia'', describing a fictional island soc ...

and Modern Times. Warren said that Stephen Pearl Andrews' ''The Science of Society'', published in 1852, was the most lucid and complete exposition of Warren's own theories. Catalan historian Xavier Diez report that the intentional communal experiments pioneered by Warren were influential in European individualist anarchists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries such as Émile Armand

Émile Armand (26 March 1872 – 19 February 1962), pseudonym of Ernest-Lucien Juin Armand, was an influential French individualist anarchist at the beginning of the 20th century and also a dedicated free love/polyamory, intentional community, a ...

and the intentional communities started by them.Xavier Diez. ''L'ANARQUISME INDIVIDUALISTA A ESPANYA 1923–1938''pg. 42

Henry David Thoreau

Henry David Thoreau (July 12, 1817May 6, 1862) was an American naturalist, essayist, poet, and philosopher. A leading transcendentalist, he is best known for his book ''Walden'', a reflection upon simple living in natural surroundings, and h ...

was an important early influence in individualist anarchist thought in the United States and Europe. Thoreau was an American author, poet, naturalist, tax resister, development critic, surveyor, historian, philosopher and leading transcendentalist. ''Civil Disobedience

Civil disobedience is the active, professed refusal of a citizen to obey certain laws, demands, orders or commands of a government (or any other authority). By some definitions, civil disobedience has to be nonviolent to be called "civil". H ...

'' is an essay by Thoreau that was first published in 1849. It argues that people should not permit governments to overrule or atrophy their consciences, and that people have a duty to avoid allowing such acquiescence

In law, acquiescence occurs when a person knowingly stands by without raising any objection to the infringement of their rights, while someone else unknowingly and without malice aforethought acts in a manner inconsistent with their rights. As a ...

to enable the government to make them the agents of injustice. Thoreau was motivated in part by his disgust with slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

and the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the ...

. It would influence Mohandas Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

, Martin Luther King Jr., Martin Buber

Martin Buber ( he, מרטין בובר; german: Martin Buber; yi, מארטין בובער; February 8, 1878 –

June 13, 1965) was an Austrian Jewish and Israeli philosopher best known for his philosophy of dialogue, a form of existentialism ...

and Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich TolstoyTolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; russian: link=no, Лев Николаевич Толстой,In Tolstoy's day, his name was written as in pre-refor ...

through its advocacy of nonviolent resistance

Nonviolent resistance (NVR), or nonviolent action, sometimes called civil resistance, is the practice of achieving goals such as social change through symbolic protests, civil disobedience, economic or political noncooperation, satyagraha, ...

. It is also the main precedent for anarcho-pacifism. Anarchism started to have an ecological view mainly in the writings of American individualist anarchist and transcendentalist Thoreau. In his book ''Walden

''Walden'' (; first published in 1854 as ''Walden; or, Life in the Woods'') is a book by American transcendentalist writer Henry David Thoreau. The text is a reflection upon the author's simple living in natural surroundings. The work is part ...

'', he advocates simple living

Simple living refers to practices that promote simplicity in one's lifestyle. Common practices of simple living include reducing the number of possessions one owns, depending less on technology and services, and spending less money. Not only is ...

and self-sufficiency

Self-sustainability and self-sufficiency are overlapping states of being in which a person or organization needs little or no help from, or interaction with, others. Self-sufficiency entails the self being enough (to fulfill needs), and a self-s ...

among natural surroundings in resistance to the advancement of industrial civilization:"Su obra más representativa es Walden, aparecida en 1854, aunque redactada entre 1845 y 1847, cuando Thoreau decide instalarse en el aislamiento de una cabaña en el bosque, y vivir en íntimo contacto con la naturaleza, en una vida de soledad y sobriedad. De esta experiencia, su filosofía trata de transmitirnos la idea que resulta necesario un retorno respetuoso a la naturaleza, y que la felicidad es sobre todo fruto de la riqueza interior y de la armonía de los individuos con el entorno natural. Muchos han visto en Thoreau a uno de los precursores del ecologismo y del anarquismo primitivista representado en la actualidad por Jonh Zerzan. Para George Woodcock(8), esta actitud puede estar también motivada por una cierta idea de resistencia al progreso y de rechazo al materialismo creciente que caracteriza la sociedad norteamericana de mediados de siglo XIX"LA INSUMISIÓN VOLUNTARIA. EL ANARQUISMO INDIVIDUALISTA ESPAÑOL DURANTE LA DICTADURA Y LA SEGUNDA REPÚBLICA (1923–1938)" by Xavier Diez

"Many have seen in Thoreau one of the precursors of ecologism and

anarcho-primitivism

Anarcho-primitivism is an anarchist critique of civilization (anti-civ) that advocates a return to non-civilized ways of life through deindustrialization, abolition of the division of labor or specialization, and abandonment of large-scale organ ...

represented today in John Zerzan

John Edward Zerzan ( ; born August 10, 1943) is an American anarchist and primitivist ecophilosopher and author. His works criticize agricultural civilization as inherently oppressive, and advocates drawing upon the ways of life of hunter-gath ...

. For George Woodcock

George Woodcock (; May 8, 1912 – January 28, 1995) was a Canadian writer of political biography and history, an anarchist thinker, a philosopher, an essayist and literary critic. He was also a poet and published several volumes of travel wri ...

, this attitude can be also motivated by certain idea of resistance to progress and of rejection of the growing materialism which is the nature of American society in the mid-19th century". Zerzan himself included the text "Excursions" (1863) by Thoreau in his edited compilation of anti-civilization writings called '' Against Civilization: Readings and Reflections'' from 1999. Walden made Thoreau influential in the European individualist anarchist green current of anarcho-naturism.

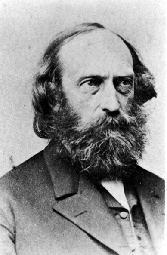

For American anarchist historian Eunice Minette Schuster, " is apparent ..that Proudhonian Anarchism was to be found in the United States at least as early as 1848 and that it was not conscious of its affinity to the Individualist Anarchism of Josiah Warren and Stephen Pearl Andrews. .. William B. Greene presented this Proudhonian Mutualism in its purest and most systematic form". William Batchelder Greene was a 19th-century mutualist,

For American anarchist historian Eunice Minette Schuster, " is apparent ..that Proudhonian Anarchism was to be found in the United States at least as early as 1848 and that it was not conscious of its affinity to the Individualist Anarchism of Josiah Warren and Stephen Pearl Andrews. .. William B. Greene presented this Proudhonian Mutualism in its purest and most systematic form". William Batchelder Greene was a 19th-century mutualist, individualist anarchist

Individualist anarchism is the branch of anarchism that emphasizes the individual and their will over external determinants such as groups, society, traditions and ideological systems."What do I mean by individualism? I mean by individualism t ...

, Unitarian minister, soldier and promoter of free banking in the United States. Greene is best known for the works ''Mutual Banking'' (1850) which proposed an interest-free banking system and ''Transcendentalism'', a critique of the New England philosophical school.

After 1850, Greene became active in labor reform and was "elected vice president of the New England Labor Reform League, the majority of the members holding to Proudhon's scheme of mutual banking, and in 1869 president of the Massachusetts Labor Union". He then published ''Socialistic, Mutualistic, and Financial Fragments'' (1875). He saw mutualism as the synthesis of "liberty and order". His "associationism ..is checked by individualism. ..'Mind your own business,' 'Judge not that ye be not judged.' Over matters which are purely personal, as for example, moral conduct, the individual is sovereign, as well as over that which he himself produces. For this reason he demands 'mutuality' in marriage—the equal right of a woman to her own personal freedom and property".

Stephen Pearl Andrews was an individualist anarchist and close associate of Josiah Warren. Andrews was formerly associated with the Fourierist

Fourierism () is the systematic set of economic, political, and social beliefs first espoused by French intellectual Charles Fourier (1772–1837). Based upon a belief in the inevitability of communal associations of people who worked and lived to ...

movement, but converted to radical individualism after becoming acquainted with the work of Warren. Like Warren, he held the principle of "individual sovereignty" as being of paramount importance. Contemporary American anarchist Hakim Bey

Peter Lamborn Wilson (October 20, 1945 – May 23, 2022) was an American anarchist author and poet, primarily known for his concept of Temporary Autonomous Zones, short-lived spaces which elude formal structures of control. During the 1970s, Wils ...

reports that "Steven Pearl Andrews ..was not a fourierist, but he lived through the brief craze for phalansteries in America and adopted a lot of fourierist principles and practices .. a maker of worlds out of words. He syncretized abolitionism, Free Love

Free love is a social movement that accepts all forms of love. The movement's initial goal was to separate the state from sexual and romantic matters such as marriage, birth control, and adultery. It stated that such issues were the concern ...

, spiritual universalism, Warren, and Fourier into a grand utopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imaginary community or society that possesses highly desirable or nearly perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book '' Utopia'', describing a fictional island soc ...

n scheme he called the Universal Pantarchy. ..He was instrumental in founding several 'intentional communities,' including the 'Brownstone Utopia' on 14th Street in New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

and 'Modern Times' in Brentwood, Long Island. The latter became as famous as the best-known fourierist communes (Brook Farm in Massachusetts and the North American Phalanx in New Jersey)—in fact, Modern Times became downright notorious for "Free Love" and finally foundered under a wave of scandalous publicity. Andrews (and Victoria Woodhull

Victoria Claflin Woodhull, later Victoria Woodhull Martin (September 23, 1838 – June 9, 1927), was an American leader of the women's suffrage movement who ran for President of the United States in the 1872 election. While many historians ...

) were members of the infamous Section 12 of the 1st International

The International Workingmen's Association (IWA), often called the First International (1864–1876), was an international organisation which aimed at uniting a variety of different left-wing socialist, communist and anarchist groups and trad ...

, expelled by Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

for its anarchist, feminist, and spiritualist

Spiritualism is the metaphysical school of thought opposing physicalism and also is the category of all spiritual beliefs/views (in monism and dualism) from ancient to modern. In the long nineteenth century, Spiritualism (when not lowercase) ...

tendencies".

19th-century individualist anarchism

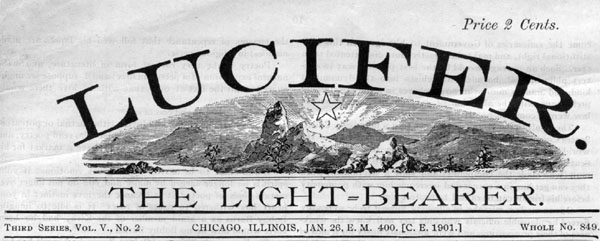

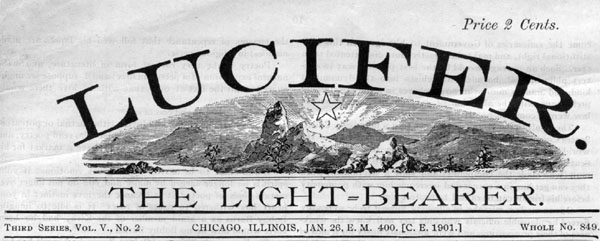

An important current within American individualist anarchism was Free love. Free love advocates sometimes traced their roots back to Josiah Warren and to experimental communities, and viewed sexual freedom as a clear, direct expression of an individual's self-ownership. Free love particularly stressed

An important current within American individualist anarchism was Free love. Free love advocates sometimes traced their roots back to Josiah Warren and to experimental communities, and viewed sexual freedom as a clear, direct expression of an individual's self-ownership. Free love particularly stressed women's rights

Women's rights are the rights and entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st centuries. In some countri ...

since most sexual laws discriminated against women: for example, marriage laws and anti-birth control measures. The most important American free love journal was ''Lucifer the Lightbearer

Moses Harman (October 12, 1830January 30, 1910) was an American schoolteacher and publisher notable for his staunch support for women's rights. He was prosecuted under the Comstock Law for content published in his anarchist periodical ''Lucifer ...

'' (1883–1907) edited by Moses Harman and Lois WaisbrookerJoanne E. Passet, "Power through Print: Lois Waisbrooker and Grassroots Feminism," in: ''Women in Print: Essays on the Print Culture of American Women from the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries'', James Philip Danky and Wayne A. Wiegand, eds., Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2006; pp. 229–250. but also there existed Ezra Heywood and Angela Heywood

Angela Fiducia Heywood (1840–1935) was a radical writer and activist, known as a free love advocate, suffragist, socialist, spiritualist, labor reformer, and abolitionist.

Early life

Angela Heywood was born in Deerfield, New Hampshire, arou ...

's '' The Word'' (1872–1890, 1892–1893). M. E. Lazarus was an important American individualist anarchist who promoted free love.

Hutchins Hapgood

Hutchins Harry Hapgood (1869–1944) was an American journalist, author and anarchist.

Life and career

Hapgood was born to Charles Hutchins Hapgood (1836–1917) and Fanny Louise (Powers) Hapgood (1846–1922) and grew up in Alton, Illinois, ...

was an American journalist, author, individualist anarchist and philosophical anarchist

Philosophical anarchism is an anarchist school of thought which focuses on intellectual criticism of authority, especially political power, and the legitimacy of governments. The American anarchist and socialist Benjamin Tucker coined the term '' ...

who was well known within the Bohemian

Bohemian or Bohemians may refer to:

*Anything of or relating to Bohemia

Beer

* National Bohemian, a brand brewed by Pabst

* Bohemian, a brand of beer brewed by Molson Coors

Culture and arts

* Bohemianism, an unconventional lifestyle, origin ...

environment of around the start of 20th-century New York City. He advocated free love and committed adultery frequently. Hapgood was a follower of the German philosophers Max Stirner

Johann Kaspar Schmidt (25 October 1806 – 26 June 1856), known professionally as Max Stirner, was a German post-Hegelian philosopher, dealing mainly with the Hegelian notion of social alienation and self-consciousness. Stirner is often seen a ...

and Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (; or ; 15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher, prose poet, cultural critic, philologist, and composer whose work has exerted a profound influence on contemporary philosophy. He began his ...

.Biographical Essay by Dowling, Robert M. American Writers, Supplement XVII. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 2008

The mission of ''Lucifer the Lightbearer'' was, according to Harman, "to help woman to break the chains that for ages have bound her to the rack of man-made law, spiritual, economic, industrial, social and especially sexual, believing that until woman is roused to a sense of her own responsibility on all lines of human endeavor, and especially on lines of her special field, that of reproduction of the race, there will be little if any real advancement toward a higher and truer civilization." The name was chosen because "Lucifer

Lucifer is one of various figures in folklore associated with the planet Venus. The entity's name was subsequently absorbed into Christianity as a name for the devil. Modern scholarship generally translates the term in the relevant Bible passa ...

, the ancient name of the Morning Star, now called Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is sometimes called Earth's "sister" or "twin" planet as it is almost as large and has a similar composition. As an interior planet to Earth, Venus (like Mercury) appears in Earth's sky never f ...

, seems to us unsurpassed as a cognomen for a journal whose mission is to bring light to the dwellers in darkness." In February 1887, the editors and publishers of ''Lucifer'' were arrested after the journal ran afoul of the Comstock Act

The Comstock laws were a set of federal acts passed by the United States Congress under the Grant administration along with related state laws.Dennett p.9 The "parent" act (Sect. 211) was passed on March 3, 1873, as the Act for the Suppression o ...

for the publication of three letters, one in particular condemning forced sex within marriage, which the author identified as rape

Rape is a type of sexual assault usually involving sexual intercourse or other forms of sexual penetration carried out against a person without their consent. The act may be carried out by physical force, coercion, abuse of authority, or ...

. In the letter, the author described the plight of a woman who had been raped by her husband, tearing stitches from a recent operation after a difficult childbirth and causing severe hemorrhaging. The letter lamented the woman's lack of legal recourse. The Comstock Act specifically prohibited the public, printed discussion of any topics that were considered "obscene, lewd, or lascivious," and discussing rape, although a criminal matter, was deemed obscene. A Topeka

Topeka ( ; Kansa: ; iow, Dópikˀe, script=Latn or ) is the capital city of the U.S. state of Kansas and the seat of Shawnee County. It is along the Kansas River in the central part of Shawnee County, in northeast Kansas, in the Central Uni ...

district attorney

In the United States, a district attorney (DA), county attorney, state's attorney, prosecuting attorney, commonwealth's attorney, or state attorney is the chief prosecutor and/or chief law enforcement officer representing a U.S. state in a ...

eventually handed down 216 indictments. Moses Harman spent two years in jail. Ezra Heywood, who had already been prosecuted under the Comstock Law for a pamphlet attacking marriage, reprinted the letter in solidarity with Harman and was also arrested and sentenced to two years in prison. In February 1890, Harman, now the sole producer of ''Lucifer'', was again arrested on charges resulting from a similar article written by a New York physician. As a result of the original charges, Harman would spend large portions of the next six years in prison

A prison, also known as a jail, gaol (dated, standard English, Australian, and historically in Canada), penitentiary (American English and Canadian English), detention center (or detention centre outside the US), correction center, corre ...

. In 1896, ''Lucifer'' was moved to Chicago; however, legal harassment continued. The United States Postal Service

The United States Postal Service (USPS), also known as the Post Office, U.S. Mail, or Postal Service, is an independent agency of the executive branch of the United States federal government responsible for providing postal service in the ...

seized and destroyed numerous issues of the journal and, in May 1905, Harman was again arrested and convicted for the distribution of two articles, namely "The Fatherhood Question" and "More Thoughts on Sexology" by Sara Crist Campbell. Sentenced to a year of hard labor, the 75-year-old editor's health deteriorated greatly. After 24 years in production, ''Lucifer'' ceased publication in 1907 and became the more scholarly ''American Journal of Eugenics''.

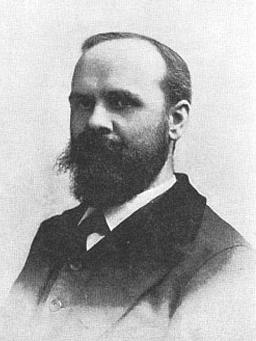

Heywood's philosophy was instrumental in furthering individualist anarchist ideas through his extensive pamphleteering and reprinting of works of Josiah Warren, author of ''True Civilization'' (1869), and William B. Greene. At a 1872 convention of the New England Labor Reform League in Boston, Heywood introduced Greene and Warren to eventual ''Liberty'' publisher Benjamin Tucker. Heywood saw what he believed to be a disproportionate concentration of capital in the hands of a few as the result of a selective extension of government-backed privileges to certain individuals and organizations. ''The Word'' was an individualist anarchist free love magazine edited by Ezra Heywood and Angela Heywood, issued first from

Heywood's philosophy was instrumental in furthering individualist anarchist ideas through his extensive pamphleteering and reprinting of works of Josiah Warren, author of ''True Civilization'' (1869), and William B. Greene. At a 1872 convention of the New England Labor Reform League in Boston, Heywood introduced Greene and Warren to eventual ''Liberty'' publisher Benjamin Tucker. Heywood saw what he believed to be a disproportionate concentration of capital in the hands of a few as the result of a selective extension of government-backed privileges to certain individuals and organizations. ''The Word'' was an individualist anarchist free love magazine edited by Ezra Heywood and Angela Heywood, issued first from Princeton, Massachusetts

Princeton is a town in Worcester County, Massachusetts, United States. It is bordered on the east by Sterling and Leominster, on the north by Westminster, on the northwest by Hubbardston, on the southwest by Rutland, and on the southeast by Ho ...

; and then from Cambridge, Massachusetts

Cambridge ( ) is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. As part of the Boston metropolitan area, the cities population of the 2020 U.S. census was 118,403, making it the fourth most populous city in the state, behind Boston, ...

. ''The Word'' was subtitled "A Monthly Journal of Reform," and it included contributions from Josiah Warren, Benjamin Tucker, and J.K. Ingalls. Initially, ''The Word'' presented free love as a minor theme which was expressed within a labor reform format. But the publication later evolved into an explicitly free love periodical. At some point Tucker became an important contributor but later became dissatisfied with the journal's focus on free love since he desired a concentration on economics. In contrast, Tucker's relationship with Heywood grew more distant. Yet, when Heywood was imprisoned for his pro-birth control stand from August to December 1878 under the Comstock laws, Tucker abandoned the ''Radical Review'' in order to assume editorship of Heywood's ''The Word''. After Heywood's release from prison, ''The Word'' openly became a free love journal; it flouted the law by printing birth control material and openly discussing sexual matters. Tucker's disapproval of this policy stemmed from his conviction that "Liberty, to be effective, must find its first application in the realm of economics".

M. E. Lazarus was an American individualist anarchist from Guntersville, Alabama

Guntersville (previously known as Gunter's Ferry and later Gunter's Landing) is a city and the county seat of Marshall County, Alabama, United States. At the 2020 census, the population of the city was 8,553. Guntersville is located in a HUBZon ...

. He is the author of several essays and anarchist pamphlettes including ''Land Tenure: Anarchist View'' (1889). A famous quote from Lazarus is "Every vote for a governing office is an instrument for enslaving me." Lazarus was also an intellectual contributor to Fourierism and the Free Love movement of the 1850s, a social reform group that called for, in its extreme form, the abolition of institutionalized marriage.

Freethought

Freethought (sometimes spelled free thought) is an epistemological viewpoint which holds that beliefs should not be formed on the basis of authority, tradition, revelation, or dogma, and that beliefs should instead be reached by other methods ...

as a philosophical position and as activism was important in North American individualist anarchism. In the United States "freethought was a basically anti-Christian, anti-clerical

Anti-clericalism is opposition to religious authority, typically in social or political matters. Historical anti-clericalism has mainly been opposed to the influence of Roman Catholicism. Anti-clericalism is related to secularism, which seeks to ...

movement, whose purpose was to make the individual politically and spiritually free to decide for himself on religious matters. A number of contributors to ''Liberty'' were prominent figures in both freethought and anarchism. The individualist anarchist George MacDonald was a co-editor of ''Freethought'' and, for a time, ''The Truth Seeker''. E.C. Walker was co-editor of the free-thought/free love journal ''Lucifer, the Light-Bearer''". "Many of the anarchists were ardent freethinkers; reprints from freethought papers such as ''Lucifer, the Light-Bearer'', ''Freethought'' and ''The Truth Seeker'' appeared in ''Liberty''...The church was viewed as a common ally of the state and as a repressive force in and of itself".

Voltairine de Cleyre was an American anarchist writer and feminist

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male po ...

. She was a prolific writer and speaker, opposing the state, marriage, and the domination of religion in sexuality and women's lives. She began her activist career in the freethought movement. De Cleyre was initially drawn to individualist anarchism but evolved through mutualism to an " anarchism without adjectives." She believed that any system was acceptable as long as it did not involve force. However, according to anarchist author Iain McKay, she embraced the ideals of stateless communism. In her 1895 lecture entitled ''Sex Slavery,'' de Cleyre condemns ideals of beauty that encourage women to distort their bodies and child socialization practices that create unnatural gender role

A gender role, also known as a sex role, is a social role encompassing a range of behaviors and attitudes that are generally considered acceptable, appropriate, or desirable for a person based on that person's sex. Gender roles are usually cen ...

s. The title of the essay refers not to traffic in women for purposes of prostitution

Prostitution is the business or practice of engaging in Sex work, sexual activity in exchange for payment. The definition of "sexual activity" varies, and is often defined as an activity requiring physical contact (e.g., sexual intercourse, n ...

, although that is also mentioned, but rather to marriage laws that allow men to rape their wives without consequences. Such laws make "every married woman what she is, a bonded slave, who takes her master's name, her master's bread, her master's commands, and serves her master's passions."

Individualist anarchism found in the United States an important space of discussion and development within what is known as the Boston anarchists. Even among the 19th-century American individualists, there was not a monolithic doctrine, as they disagreed amongst each other on various issues including

Individualist anarchism found in the United States an important space of discussion and development within what is known as the Boston anarchists. Even among the 19th-century American individualists, there was not a monolithic doctrine, as they disagreed amongst each other on various issues including intellectual property

Intellectual property (IP) is a category of property that includes intangible creations of the human intellect. There are many types of intellectual property, and some countries recognize more than others. The best-known types are patents, co ...

rights and possession versus property

Property is a system of rights that gives people legal control of valuable things, and also refers to the valuable things themselves. Depending on the nature of the property, an owner of property may have the right to consume, alter, share, r ...

in land. Watner, Carl (1977). . ''Journal of Libertarian Studies

Ludwig von Mises Institute for Austrian Economics, or Mises Institute, is a libertarian nonprofit think tank headquartered in Auburn, Alabama, United States. It is named after the Austrian School economist Ludwig von Mises (1881–1973).

It wa ...

'', Vol. 1, No. 4, p. 308. A major schism occurred later in the 19th century when Tucker and some others abandoned their traditional support of natural rights as espoused by Lysander Spooner

Lysander Spooner (January 19, 1808May 14, 1887) was an American individualist anarchist, abolitionist, entrepreneur, essayist, legal theorist, pamphletist, political philosopher, Unitarian and writer.

Spooner was a strong advocate of the labor ...

and converted to an egoism modeled upon Stirner's philosophy. Besides his individualist anarchist activism, Spooner was also an important anti-slavery activist and became a member of the First International

The International Workingmen's Association (IWA), often called the First International (1864–1876), was an international organisation which aimed at uniting a variety of different left-wing socialist, communist and anarchist groups and trad ...

. Some Boston anarchists, including Tucker, identified themselves as socialists which in the 19th century was often used in the sense of a commitment to improving conditions of the working class (i.e. " the labor problem"). The Boston anarchists such as Tucker and his followers are considered socialists to this day due to their opposition to usury.

''

''Liberty

Liberty is the ability to do as one pleases, or a right or immunity enjoyed by prescription or by grant (i.e. privilege). It is a synonym for the word freedom.

In modern politics, liberty is understood as the state of being free within society fr ...

'' was a 19th-century anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessar ...

market socialist

Market socialism is a type of economic system involving the public, cooperative, or social ownership of the means of production in the framework of a market economy, or one that contains a mix of worker-owned, nationalized, and privately owned ...

and libertarian socialist

Libertarian socialism, also known by various other names, is a left-wing,Diemer, Ulli (1997)"What Is Libertarian Socialism?" The Anarchist Library. Retrieved 4 August 2019. anti-authoritarian, anti-statist and libertarianLong, Roderick T. (20 ...

periodical published in the United States by Benjamin Tucker

Benjamin Ricketson Tucker (; April 17, 1854 – June 22, 1939) was an American individualist anarchist and libertarian socialist.Martin, James J. (1953)''Men Against the State: The Expositers of Individualist Anarchism in America, 1827–1908''< ...

from August 1881 to April 1908. The periodical was instrumental in developing and formalizing the individualist anarchist philosophy through publishing essays and serving as a format for debate. Contributors included Benjamin Tucker, Lysander Spooner, Auberon Herbert Auberon (french: Oberon, links=no) may refer to:

People

* Auberon Herbert (1838–1906), British writer, theorist, philosopher and son of the 3rd Earl of Carnarvon

* Auberon Herbert, 9th Baron Lucas (1876–1916), British politician and fighter ...

, Dyer Lum

Dyer Daniel Lum (February 15, 1839 – April 6, 1893) was an American anarchist, labor activist and poet. A leading syndicalist and a prominent left-wing intellectual of the 1880s, Lum is best remembered as the lover and mentor of early anarch ...

, Joshua K. Ingalls, John Henry Mackay

John Henry Mackay, also known by the pseudonym Sagitta, (6 February 1864 – 16 May 1933) was an egoist anarchist, thinker and writer. Born in Scotland and raised in Germany, Mackay was the author of '' Die Anarchisten'' (The Anarchists, 1891) a ...

, Victor Yarros, Wordsworth Donisthorpe

__NOTOC__Wordsworth Donisthorpe (24 March 1847 – 30 January 1914) was an English barrister, individualist anarchist and inventor, pioneer of cinematography and chess enthusiast.

Life and work

Donisthorpe was born in Leeds, on 24 March 1847. ...

, James L. Walker

James L. Walker (June 1845 – April 2, 1904), sometimes known by the pen name Tak Kak, was an American individualist anarchist of the Egoist school, born in Manchester.

Walker was one of the main contributors to Benjamin Tucker's ''Liberty ...

, J. William Lloyd

J. William Lloyd (never using his given name John) (June 4, 1857 – October 23, 1940) was an American individualist anarchist, mystic and pantheist. Lloyd later modified his political position to minarchism.

Biography

He was born in Westfield ...

, Florence Finch Kelly

Florence Finch Kelly (March 27, 1858 – December 17, 1939) was an American feminist, suffragist, journalist and author of novels and short stories.

Biography

Florence Finch was born in Girard, Illinois, March 27, 1858. She was the youngest chil ...

, Voltairine de Cleyre, Steven T. Byington, John Beverley Robinson

John Beverley Robinson (February 21, 1821 – June 19, 1896) was a Canadian politician, lawyer and businessman. He was mayor of Toronto and a provincial and federal member of parliament. He was the fifth Lieutenant Governor of Ontario between ...

, Jo Labadie

Charles Joseph Antoine Labadie (April 18, 1850 – October 7, 1933) was an American labor organizer, anarchist, Greenbacker, social activist, printer, publisher, essayist, and poet.

Biography

Early years

Jo Labadie was born on April 18, 1850, i ...

, Lillian Harman, and Henry Appleton. Included in its masthead is a quote from Pierre Proudhon saying that liberty is "Not the Daughter But the Mother of Order."

Some of the American individualist anarchists later in this era such as Benjamin Tucker abandoned natural rights positions and converted to Max Stirner's

Some of the American individualist anarchists later in this era such as Benjamin Tucker abandoned natural rights positions and converted to Max Stirner's egoist anarchism

Egoist anarchism or anarcho-egoism, often shortened as simply egoism, is a school of anarchist thought that originated in the philosophy of Max Stirner, a 19th-century philosopher whose "name appears with familiar regularity in historically or ...