Alice Hamilton on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Alice Hamilton (February 27, 1869Corn, J

Hamilton, Alice

''American National Biography'' – September 22, 1970) was an American physician, research scientist, and author. She was a leading expert in the field of occupational health and a pioneer in the field of industrial toxicology. Hamilton trained at the

Alice was the second oldest of five siblings that included three sisters (Edith, Margaret, and Norah) and a brother (Arthur "Quint"), all of whom were accomplished in their respective fields. The girls remained especially close throughout their childhood and into their professional careers.

Alice was the second oldest of five siblings that included three sisters (Edith, Margaret, and Norah) and a brother (Arthur "Quint"), all of whom were accomplished in their respective fields. The girls remained especially close throughout their childhood and into their professional careers.

Hamilton's parents homeschooled their children from an early age. Following a family tradition among the Hamilton women, Alice completed her early education at Miss Porter's Finishing School for Young Ladies (also known as

Hamilton's parents homeschooled their children from an early age. Following a family tradition among the Hamilton women, Alice completed her early education at Miss Porter's Finishing School for Young Ladies (also known as  In 1893–94, after graduation from medical school, Hamilton completed internships at the Northwestern Hospital for Women and Children in Minneapolis and at the New England Hospital for Women and Children in

In 1893–94, after graduation from medical school, Hamilton completed internships at the Northwestern Hospital for Women and Children in Minneapolis and at the New England Hospital for Women and Children in

In January 1919, Hamilton accepted a position as assistant professor in a newly formed Department of Industrial Medicine (and after 1925 the School of Public Health) at

In January 1919, Hamilton accepted a position as assistant professor in a newly formed Department of Industrial Medicine (and after 1925 the School of Public Health) at

The Woman Who Founded Industrial Medicine

Scientific American, October 23, 2019

Hamilton, Alice, 1869-1970. Papers of Alice Hamilton, 1909-1987 (inclusive), 1909-1965 (bulk): A Finding AidSchlesinger Library

, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University. *

Alice Hamilton in The Connecticut Women's Hall of Fame

at The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

Alice Hamilton, M.D.

– Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

Exploring the Dangerous Trades ExcerptAudio Clip of Dr. Alice Hamilton: "But Who Will Darn the Stockings?"Dr. Alice Hamilton

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hamilton, Alice American occupational health practitioners 1869 births 1970 deaths Johns Hopkins University alumni Harvard University faculty American centenarians American democratic socialists American women physicians American toxicologists American pacifists Northwestern University faculty Industrial hygiene University of Michigan Medical School alumni Physicians from New York City People from Fort Wayne, Indiana Women centenarians Miss Porter's School alumni International Congress of Women people American women academics American people of Scotch-Irish descent

Hamilton, Alice

''American National Biography'' – September 22, 1970) was an American physician, research scientist, and author. She was a leading expert in the field of occupational health and a pioneer in the field of industrial toxicology. Hamilton trained at the

University of Michigan Medical School

Michigan Medicine (University of Michigan Health System or UMHS before 2017) is the wholly owned academic medical center of the University of Michigan, a public research university in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Michigan Medicine includes the Unive ...

. She became a professor of pathology at the Woman's Medical School of Northwestern University

Northwestern University is a private research university in Evanston, Illinois. Founded in 1851, Northwestern is the oldest chartered university in Illinois and is ranked among the most prestigious academic institutions in the world.

Charte ...

in 1897. In 1919, she became the first woman appointed to the faculty of Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of highe ...

.

Her scientific research focused on the study of occupational illnesses and the dangerous effects of industrial metals and chemical compound

A chemical compound is a chemical substance composed of many identical molecules (or molecular entities) containing atoms from more than one chemical element held together by chemical bonds. A molecule consisting of atoms of only one element ...

s. In addition to her scientific work, Hamilton was a social-welfare reformer, humanitarian, peace activist, and a resident-volunteer at Hull House

Hull House was a settlement house in Chicago, Illinois, United States that was co-founded in 1889 by Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr. Located on the Near West Side of the city, Hull House (named after the original house's first owner Ch ...

in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

from 1887 to 1919. She received numerous honors and awards, including the Albert Lasker Public Service Award

The Lasker-Bloomberg Public Service Award, known until 2009 as the Mary Woodard Lasker Public Service Award, is awarded by the Lasker Foundation to honor an individual or organization whose public service has profoundly enlarged the possibilities f ...

.

Early life and family

Hamilton, the second child of Montgomery Hamilton (1843–1909) and Gertrude (née Pond) Hamilton (1840–1917), was born on February 27, 1869, inManhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

, New York City, New York. She spent a sheltered childhood among an extended family in Fort Wayne, Indiana

Fort Wayne is a city in and the county seat of Allen County, Indiana, United States. Located in northeastern Indiana, the city is west of the Ohio border and south of the Michigan border. The city's population was 263,886 as of the 2020 Censu ...

, where her grandfather, Allen Hamilton

Allen Hamilton (1798–1864) was a founding father of Fort Wayne in Allen County, Indiana.

Biography

Hamilton, an Irish emigrant, lived in Lawrenceburg in Dearborn County, Indiana, in 1820, when he married Emerine J. Holman, the daughter ...

, an Irish immigrant, had settled in 1823. He married Emerine Holman, the daughter of Indiana Supreme Court

The Indiana Supreme Court, established by Article 7 of the Indiana Constitution, is the highest judicial authority in the state of Indiana. Located in Indianapolis, the Court's chambers are in the north wing of the Indiana Statehouse.

In Decem ...

Justice Jesse Lynch Holman

Jesse Lynch Holman (October 24, 1784 – March 28, 1842) was an Indiana attorney, politician and jurist, as well as a novelist, poet, city planner and preacher. He helped to found Indiana University, Franklin College and the Indiana Historical ...

, in 1828 and became a successful Fort Wayne businessman and a land speculator. Much of the city of Fort Wayne was built on land that he once owned. Alice grew up on the Hamilton family's large estate that encompassed a three-block area of downtown Fort Wayne. The Hamilton family also spent many summers at Mackinac Island, Michigan. For the most part, the second and third generations of the extended Hamilton family, which included Alice's family, as well as her uncles, aunts, and cousins, lived on inherited wealth.

Montgomery Hamilton, Alice's father, attended Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the ...

and Harvard Law School

Harvard Law School (Harvard Law or HLS) is the law school of Harvard University, a private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1817, it is the oldest continuously operating law school in the United States.

Each c ...

. He also studied in Germany, where he met Gertrude Pond, the daughter of a wealthy sugar importer. They were married in 1866.Weber, p. 31. Alice's father became a partner in a wholesale grocery business in Fort Wayne, but the partnership dissolved in 1885 and he withdrew from public life. Although the business failure caused a financial loss for the family, Alice's outspoken mother, Gertrude, remained socially active in the Fort Wayne community.

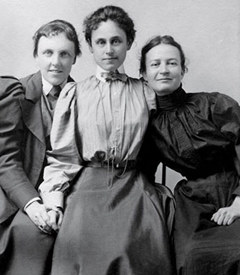

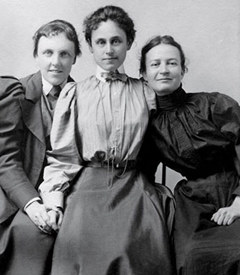

Alice was the second oldest of five siblings that included three sisters (Edith, Margaret, and Norah) and a brother (Arthur "Quint"), all of whom were accomplished in their respective fields. The girls remained especially close throughout their childhood and into their professional careers.

Alice was the second oldest of five siblings that included three sisters (Edith, Margaret, and Norah) and a brother (Arthur "Quint"), all of whom were accomplished in their respective fields. The girls remained especially close throughout their childhood and into their professional careers. Edith

Edith is a feminine given name derived from the Old English words ēad, meaning 'riches or blessed', and is in common usage in this form in English, German, many Scandinavian languages and Dutch. Its French form is Édith. Contractions and var ...

(1867–1963), an educator and headmistress at Bryn Mawr School

Bryn Mawr School, founded in 1885 as the first college-preparatory school for girls in the United States, is an independent, nonsectarian all-girls school for grades PK-12, with a coed preschool. Bryn Mawr School is located in the Roland Park co ...

in Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore was ...

, became a classicist and renowned author for her essays and best-selling books on ancient Greek and Roman civilizations. Margaret

Margaret is a female first name, derived via French () and Latin () from grc, μαργαρίτης () meaning "pearl". The Greek is borrowed from Persian.

Margaret has been an English name since the 11th century, and remained popular through ...

(1871–1969), like her older sister Edith, became an educator and headmistress at Bryn Mawr School. Norah (1873–1945) was an artist, living and working at Hull House

Hull House was a settlement house in Chicago, Illinois, United States that was co-founded in 1889 by Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr. Located on the Near West Side of the city, Hull House (named after the original house's first owner Ch ...

. Arthur

Arthur is a common male given name of Brythonic origin. Its popularity derives from it being the name of the legendary hero King Arthur. The etymology is disputed. It may derive from the Celtic ''Artos'' meaning “Bear”. Another theory, more wi ...

(1886–1967), the youngest Hamilton sibling, became a writer, professor of Spanish, and assistant dean for foreign students at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

The University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (U of I, Illinois, University of Illinois, or UIUC) is a public land-grant research university in Illinois in the twin cities of Champaign and Urbana. It is the flagship institution of the Un ...

. Arthur was the only sibling to marry; he and his wife, Mary (Neal) Hamilton, had no children.

Education

Hamilton's parents homeschooled their children from an early age. Following a family tradition among the Hamilton women, Alice completed her early education at Miss Porter's Finishing School for Young Ladies (also known as

Hamilton's parents homeschooled their children from an early age. Following a family tradition among the Hamilton women, Alice completed her early education at Miss Porter's Finishing School for Young Ladies (also known as Miss Porter's School

Miss Porter's School (MPS) is an elite American private college preparatory school for girls founded in 1843, and located in Farmington, Connecticut. The school draws students from 21 states, 31 countries (with dual-citizenship and/or residence), ...

) in Farmington, Connecticut

Farmington is a town in Hartford County in the Farmington Valley area of central Connecticut in the United States. The population was 26,712 at the 2020 census. It sits 10 miles west of Hartford at the hub of major I-84 interchanges, 20 miles ...

, from 1886 to 1888. In addition to Alice, three of her aunts, three cousins, and all three of her sisters were alumnae of the school.

Although Hamilton had led a privileged life in Fort Wayne, she aspired to provide some type of useful service to the world and chose medicine as a way to financially support herself. Hamilton, who was an avid reader, also cited literary influence for inspiring her to become a physician, even though she had not yet received any training in the sciences: "I meant to be a medical missionary to Teheran

Tehran (; fa, تهران ) is the largest city in Tehran Province and the capital of Iran. With a population of around 9 million in the city and around 16 million in the larger metropolitan area of Greater Tehran, Tehran is the most popul ...

, having been fascinated by the description of Persia in dmondO'Donovan's ''The Merv Oasis.'' I doubted if I could ever be good enough to be a real missionary, but if I could care for the sick, that would do instead."

After her return to Indiana from school in Connecticut, Hamilton studied science with a high school teacher in Fort Wayne and anatomy at Fort Wayne College of Medicine for a year before enrolling at the University of Michigan

, mottoeng = "Arts, Knowledge, Truth"

, former_names = Catholepistemiad, or University of Michigania (1817–1821)

, budget = $10.3 billion (2021)

, endowment = $17 billion (2021)As o ...

Medical School in 1892.Weber, p. 32.

There she had the opportunity of studying with "a remarkable group of men" – John Jacob Abel

John Jacob Abel (19 May 1857 – 26 May 1938) was an American biochemist and pharmacologist. He established the pharmacology department at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in 1893, and then became America's first full-time professor o ...

(pharmacology), William Henry Howell (physiology), Frederick George Novy

__NOTOC__

Frederick George Novy (December 9, 1864 – August 8, 1957) was an American bacteriologist, organic chemist, and instructor.

Born in Chicago, Illinois, the third son of Joseph Novy and his wife Frances, grew up on the West Side, near t ...

(bacteriology), Victor C. Vaughan (biochemistry) and George Dock

George may refer to:

People

* George (given name)

* George (surname)

* George (singer), American-Canadian singer George Nozuka, known by the mononym George

* George Washington, First President of the United States

* George W. Bush, 43rd Presid ...

(medicine). During her last year of study she served on Dr. Dock's staff, going on rounds, taking histories and doing clinical laboratory work.

Hamilton earned a medical degree from the university in 1893.

In 1893–94, after graduation from medical school, Hamilton completed internships at the Northwestern Hospital for Women and Children in Minneapolis and at the New England Hospital for Women and Children in

In 1893–94, after graduation from medical school, Hamilton completed internships at the Northwestern Hospital for Women and Children in Minneapolis and at the New England Hospital for Women and Children in Roxbury Roxbury may refer to:

Places

;Canada

* Roxbury, Nova Scotia

* Roxbury, Prince Edward Island

;United States

* Roxbury, Connecticut

* Roxbury, Kansas

* Roxbury, Maine

* Roxbury, Boston, a municipality that was later integrated into the city of Bo ...

, a suburban neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts, to gain some clinical experience.Weber, p. 33. Hamilton had already decided that she was not interested in establishing a medical practice and returned to the University of Michigan in February 1895 to study bacteriology Bacteriology is the branch and specialty of biology that studies the morphology, ecology, genetics and biochemistry of bacteria as well as many other aspects related to them. This subdivision of microbiology involves the identification, classificat ...

as a resident graduate and lab assistant of Frederick George Novy. She also began to develop an interest in public health.

In the fall of 1895, Alice and her older sister, Edith, traveled to Germany. Alice planned to study bacteriology and pathology at the advice of her professors at Michigan, while Edith intended to study the classics and attend lectures.Weber, p. 43. The Hamilton sisters faced some opposition to their efforts to study abroad. Although Alice was welcomed in Frankfurt

Frankfurt, officially Frankfurt am Main (; Hessian: , " Frank ford on the Main"), is the most populous city in the German state of Hesse. Its 791,000 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located on it ...

, her requests to study in Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

were rejected and she experienced some prejudice against women when the two sisters studied at universities in Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the third-largest city in Germany, after Berlin and ...

and Leipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as ...

.

When Alice returned to the United States in September 1896, she continued postgraduate studies for a year at the Johns Hopkins University

Johns Hopkins University (Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private research university in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1876, Johns Hopkins is the oldest research university in the United States and in the western hemisphere. It consi ...

Medical School. There she worked with Simon Flexner

Simon Flexner, M.D. (March 25, 1863 in Louisville, Kentucky – May 2, 1946) was a physician, scientist, administrator, and professor of experimental pathology at the University of Pennsylvania (1899–1903). He served as the first director ...

on pathological anatomy. She also had the opportunity to learn from William H. Welch and William Osler

Sir William Osler, 1st Baronet, (; July 12, 1849 – December 29, 1919) was a Canadian physician and one of the "Big Four" founding professors of Johns Hopkins Hospital. Osler created the first residency program for specialty training of phys ...

.

Career

Early years at Chicago's Hull House

In 1897 Hamilton accepted an offer to become a professor of pathology at the Woman's Medical School ofNorthwestern University

Northwestern University is a private research university in Evanston, Illinois. Founded in 1851, Northwestern is the oldest chartered university in Illinois and is ranked among the most prestigious academic institutions in the world.

Charte ...

. Soon after her move to Chicago, Illinois, Hamilton fulfilled a longtime ambition to become a member and resident of Hull House

Hull House was a settlement house in Chicago, Illinois, United States that was co-founded in 1889 by Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr. Located on the Near West Side of the city, Hull House (named after the original house's first owner Ch ...

, the settlement house

The settlement movement was a reformist social movement that began in the 1880s and peaked around the 1920s in United Kingdom and the United States. Its goal was to bring the rich and the poor of society together in both physical proximity and s ...

founded by social reformer Jane Addams

Laura Jane Addams (September 6, 1860 May 21, 1935) was an American Settlement movement, settlement activist, Social reform, reformer, social worker, sociologist, public administrator, and author. She was an important leader in the history of s ...

and Ellen Gates Starr

Ellen Gates Starr (March 19, 1859 – February 10, 1940) was an American social reformer and activist. With Jane Addams, she founded Chicago's Hull House, an adult education center, in 1889; the settlement house expanded to 13 buildings in ...

. While Hamilton taught and did research at the medical school during the day, she maintained an active life at Hull House, her full-time residence from 1897 to 1919.

Hamilton became Jane Addams' personal physician and volunteered her time at Hull House to teach English and art. She also directed the men's fencing and athletic clubs, operated a well-baby clinic, and visited the sick in their homes.Weber, p. 34.

Other inhabitants of Hull House included Alice's sister Norah, and her friends Rachelle and Victor Yarros.

Although Hamilton moved away from Chicago in 1919 when she accepted a position as an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School

Harvard Medical School (HMS) is the graduate medical school of Harvard University and is located in the Longwood Medical Area of Boston, Massachusetts. Founded in 1782, HMS is one of the oldest medical schools in the United States and is cons ...

, she returned to Hull House and stayed for several months each spring until Jane Addams's death in 1935.

Through her association and work at Hull House and living side by side with the poor residents of the community, Hamilton witnessed the effects that the dangerous trades had on workers' health through exposure to carbon monoxide and lead poisoning

Lead poisoning, also known as plumbism and saturnism, is a type of metal poisoning caused by lead in the body. The brain is the most sensitive. Symptoms may include abdominal pain, constipation, headaches, irritability, memory problems, infertil ...

. As a result, she became increasingly interested in the problems the workers faced, especially occupational injuries and illnesses. The experience also caused Hamilton to begin considering how to merge her interests in medical science and social reform to improve the health of American workers.

When the Woman's Medical School closed in 1902, Hamilton took a position as bacteriologist with the Memorial Institute for Infectious Diseases, working with Ludvig Hektoen

Ludvig Hektoen (July 2, 1863 – July 5, 1951) was an American pathologist known for his work in the fields of pathology, microbiology and immunology. Hektoen was appointed to the National Academy of Sciences in 1918, and served as president of ...

. During this time, she also formed a friendship with bacteriologist Ruth Tunnicliffe. Hamilton investigated a typhoid epidemic in Chicago before focusing her research on the investigation of industrial diseases.Sicherman and Green, p. 304. Some of Hamilton's early research in this area included attempts to identify causes of typhoid and tuberculosis in the community surrounding Hull House. Her work on typhoid in 1902 led to the replacement of the chief sanitary inspector of the area by the Chicago Board of Health The Chicago Board of Health is the local board of health for the city of Chicago. Two previous iterations existed before the modern board was formed in 1932. The modern board is a policy-making body for health related matters and advises the Chicag ...

.

The study of industrial medicine (work-related illnesses) had become increasingly important because the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

of the late nineteenth century had led to new dangers in the workplace. In 1907 Hamilton began exploring existing literature from abroad and noticed that industrial medicine was not being studied as much in America. She set out to change the situation and published her first article on the topic in 1908.

Medical Investigator

Hamilton began her long career in public health and workplace safety in 1910, when Illinois governor Charles S. Deneen appointed her as a medical investigator to the newly formed Illinois Commission on Occupational Diseases. Hamilton led the commission's investigations, which focused on industrial poisons such as lead and other toxins. She also authored the "Illinois Survey," the commission's report that documented its findings of industrial processes that exposed workers to lead poisoning and other illnesses. The commission's efforts resulted in the passage of the first workers' compensation laws in Illinois in 1911, in Indiana in 1915, and occupational disease laws in other states. The new laws required employers to take safety precautions to protect workers. By 1916 Hamilton had become America's leading authority on lead poisoning. For the next decade she investigated a range of issues for a variety of state and federal health committees. Hamilton focused her explorations on occupational toxic disorders, examining the effects of substances such asaniline dyes

Aniline is an organic compound with the formula C6 H5 NH2. Consisting of a phenyl group attached to an amino group, aniline is the simplest aromatic amine. It is an industrially significant commodity chemical, as well as a versatile startin ...

, carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide ( chemical formula CO) is a colorless, poisonous, odorless, tasteless, flammable gas that is slightly less dense than air. Carbon monoxide consists of one carbon atom and one oxygen atom connected by a triple bond. It is the simpl ...

, mercury, tetraethyl lead

Tetraethyllead (commonly styled tetraethyl lead), abbreviated TEL, is an organolead compound with the formula Pb( C2H5)4. It is a fuel additive, first being mixed with gasoline beginning in the 1920s as a patented octane rating booster that al ...

, radium

Radium is a chemical element with the symbol Ra and atomic number 88. It is the sixth element in group 2 of the periodic table, also known as the alkaline earth metals. Pure radium is silvery-white, but it readily reacts with nitrogen (rat ...

, benzene

Benzene is an organic chemical compound with the molecular formula C6H6. The benzene molecule is composed of six carbon atoms joined in a planar ring with one hydrogen atom attached to each. Because it contains only carbon and hydrogen atoms ...

, carbon disulfide

Carbon disulfide (also spelled as carbon disulphide) is a neurotoxic, colorless, volatile liquid with the formula and structure . The compound is used frequently as a building block in organic chemistry as well as an industrial and chemical n ...

and hydrogen sulfide

Hydrogen sulfide is a chemical compound with the formula . It is a colorless chalcogen-hydride gas, and is poisonous, corrosive, and flammable, with trace amounts in ambient atmosphere having a characteristic foul odor of rotten eggs. The under ...

gases. In 1925, at a Public Health Service conference on the use of lead in gasoline, she testified against the use of lead and warned of the danger it posed to people and the environment. Nevertheless, leaded gasoline was allowed. The EPA

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is an independent executive agency of the United States federal government tasked with environmental protection matters. President Richard Nixon proposed the establishment of EPA on July 9, 1970; it be ...

in 1988 estimated that over the previous 60 years that 68 million children suffered high toxic exposure to lead from leaded fuels.

Her work on the manufacture of white lead

White lead is the basic lead carbonate 2PbCO3·Pb(OH)2. It is a complex salt, containing both carbonate and hydroxide ions. White lead occurs naturally as a mineral, in which context it is known as hydrocerussite, a hydrate of cerussite. It was ...

and lead oxide

Lead oxides are a group of inorganic compounds with formulas including lead (Pb) and oxygen (O).

Common lead oxides include:

* Lead(II) oxide, PbO, litharge (red), massicot (yellow)

* Lead(II,IV) oxide

Lead(II,IV) oxide, also called red lead o ...

, as a special investigator for the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) is a unit of the United States Department of Labor. It is the principal fact-finding agency for the U.S. government in the broad field of labor economics and statistics and serves as a principal agency of ...

, is considered a "landmark study". Relying primarily on "shoe leather epidemiology" (her process of making personal visits to factories, conducting interviews with workers, and compiling details of diagnosed poisoning cases) and the emerging laboratory science of toxicology, Hamilton pioneered occupational epidemiology

Occupational epidemiology is a subdiscipline of epidemiology that focuses on investigations of workers and the workplace. Occupational epidemiologic studies examine health outcomes among workers, and their potential association with conditions in ...

and industrial hygiene

Occupational hygiene (United States: industrial hygiene (IH)) is the anticipation, recognition, evaluation, control, and confirmation (ARECC) of protection from hazards at work that may result in injury, illness, or affect the well being of work ...

. She also created the specialized field of industrial medicine in the United States. Her findings were scientifically persuasive and influenced sweeping health reforms that changed laws and general practice to improve the health of workers.Weber, p. 35.

During World War I, the US Army tasked her with solving a mysterious ailment striking workers at a munitions plant in New Jersey. She led a team that included George Minot

George Richards Minot (December 2, 1885 – February 25, 1950) was an American medical researcher who shared the 1934 Nobel Prize with George Hoyt Whipple and William P. Murphy for their pioneering work on pernicious anemia.

Early life

George R ...

, a professor at Harvard Medical School. She deduced that the workers were being sickened through contact with the explosive trinitrotoluene

Trinitrotoluene (), more commonly known as TNT, more specifically 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene, and by its preferred IUPAC name 2-methyl-1,3,5-trinitrobenzene, is a chemical compound with the formula C6H2(NO2)3CH3. TNT is occasionally used as a reage ...

(TNT). She recommended that workers wear protective clothing to be removed and washed at the end of each shift, solving the problem.

Hamilton's best-known research included her studies on carbon monoxide poisoning among American steelworkers, mercury poisoning of hatters, and " a debilitating hand condition developed by workers using jackhammers." At the request of the U.S. Department of Labor, she also investigated industries involved in developing high explosives, "spastic anemia known as 'dead fingers'" among Bedford, Indiana

Bedford is a city in Shawswick Township and the county seat of Lawrence County, Indiana, United States. In the 2020 census, the population was 13,792. That is up from 13,413 in 2010. Bedford is the principal city of the Bedford, IN Micropo ...

, limestone cutters, and the "unusually high incidence of pulmonary tuberculosis" among tombstone carvers working in the granite mills of Quincy, Massachusetts

Quincy ( ) is a coastal U.S. city in Norfolk County, Massachusetts, United States. It is the largest city in the county and a part of Metropolitan Boston as one of Boston's immediate southern suburbs. Its population in 2020 was 101,636, making ...

, and Barre, Vermont Barre, Vermont may refer to:

*Barre (city), Vermont

*Barre (town), Vermont

Barre ( ) is a town in Washington County, Vermont, United States. The population was 7,923 at the 2020 census, making it the 3rd largest municipality in Washington County ...

.Weber, p. 37. Hamilton was also a member of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of the Mortality from Tuberculosis in Dusty Trades, whose efforts "laid the groundwork for further studies and eventual widespread reform in the industry."

Women's rights and peace activist

During her years at Hull House, Hamilton was active in thewomen's rights

Women's rights are the rights and entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st centuries. In some countri ...

and peace movement

A peace movement is a social movement which seeks to achieve ideals, such as the ending of a particular war (or wars) or minimizing inter-human violence in a particular place or situation. They are often linked to the goal of achieving world pe ...

s. She traveled with Jane Addams

Laura Jane Addams (September 6, 1860 May 21, 1935) was an American Settlement movement, settlement activist, Social reform, reformer, social worker, sociologist, public administrator, and author. She was an important leader in the history of s ...

and Emily Greene Balch

Emily Greene Balch (January 8, 1867 – January 9, 1961) was an American economist, sociologist and pacifist. Balch combined an academic career at Wellesley College with a long-standing interest in social issues such as poverty, child labor, ...

to the 1915 International Congress of Women

The International Congress of Women was created so that groups of existing women's suffrage movements could come together with other women's groups around the world. It served as a way for women organizations across the nation to establish formal m ...

in The Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a city and municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's administrative centre and its seat of government, and while the official capital o ...

, where they met Aletta Jacobs

Aletta Henriëtte Jacobs (; 9 February 1854 – 10 August 1929) was a Dutch physician and women's suffrage activist. As the first woman officially to attend a Dutch university, she became one of the first female physicians in the Netherlands. ...

, a Dutch pacifist, feminist, and suffragist. Rediscovered historical footage shows Addams, Hamilton, and Jacobs before the Brandenburg Gate

The Brandenburg Gate (german: Brandenburger Tor ) is an 18th-century Neoclassical architecture, neoclassical monument in Berlin, built on the orders of Prussian king Frederick William II of Prussia, Frederick William II after Prussian invasion ...

in Berlin on May 24, 1915, during a visit to Germany to meet government leaders. She also visited German-occupied Belgium.

Hamilton returned to Europe with Addams in May 1919 to attend the second International Congress of Women at Zurich, Switzerland. In addition, Hamilton, Addams, Jacobs, and American Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abili ...

Carolena M. Wood became involved in a humanitarian mission to Germany to distribute food aid and investigate reports of famine.Sklar, Schüler, and Strasser, pp. 53–55.

Assistant professor, Harvard Medical School

In January 1919, Hamilton accepted a position as assistant professor in a newly formed Department of Industrial Medicine (and after 1925 the School of Public Health) at

In January 1919, Hamilton accepted a position as assistant professor in a newly formed Department of Industrial Medicine (and after 1925 the School of Public Health) at Harvard Medical School

Harvard Medical School (HMS) is the graduate medical school of Harvard University and is located in the Longwood Medical Area of Boston, Massachusetts. Founded in 1782, HMS is one of the oldest medical schools in the United States and is cons ...

, making her the first woman appointed to the Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of highe ...

faculty in any field. Her appointment was hailed by the ''New York Tribune

The ''New-York Tribune'' was an American newspaper founded in 1841 by editor Horace Greeley. It bore the moniker ''New-York Daily Tribune'' from 1842 to 1866 before returning to its original name. From the 1840s through the 1860s it was the domi ...

'' with the headline: "A Woman on Harvard Faculty—The Last Citadel Has Fallen—The Sex Has Come Into Its Own". Her own comment was "Yes, I am the first woman on the Harvard faculty—but not the first one who should have been appointed!"

During her years at Harvard, from 1919 to her retirement in 1935, Hamilton never received a faculty promotion and held only a series of three-year appointments. At her request, the half-time appointments for which she taught one semester per year allowed her to continue her research and spend several months of each year at Hull House. Hamilton also faced discrimination as a woman. She was excluded from social activities, could not enter the Harvard Union, attend the Faculty Club, or receive a quota of football tickets. In addition, Hamilton was not allowed to march in the university's commencement ceremonies as the male faculty members did.Jay, p. 149.

Hamilton became a successful fundraiser for Harvard as she continued to write and conduct research on the dangerous trades. In addition to publishing "landmark reports for the U.S. Department of Labor" on research related to workers in Arizona copper mines and stonecutters at Indiana's limestone quarries, Hamilton also wrote ''Industrial Poisons in the United States'' (1925), the first American textbook on the subject, and another related textbook, ''Industrial Toxicology'' (1934).Sicherman and Green, p. 305. At a tetraethyl lead conference in Washington, D.C. in 1925, Hamilton was a prominent critic of adding tetraethyl lead

Tetraethyllead (commonly styled tetraethyl lead), abbreviated TEL, is an organolead compound with the formula Pb( C2H5)4. It is a fuel additive, first being mixed with gasoline beginning in the 1920s as a patented octane rating booster that al ...

to gasoline.

Hamilton also remained an activist in social reform efforts. Her specific interests in civil liberties, peace, birth control, and protective labor legislation for women caused some of her critics to consider her a "radical" and a "subversive." From 1924 to 1930, she served as the only woman member of the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference th ...

Health Committee. She also visited the Soviet Union in 1924 and Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

in April 1933. Hamilton wrote "The Youth Who Are Hitler's Strength," which was published in ''The New York Times''. The article described Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

exploitation of youth in the years between the two world wars.Sicherman, ''Alice Hamilton, A Life in Letters'', p. 437. She also criticized the Nazi education, especially its domestic training for girls.

Later years

After her retirement from Harvard in 1935, Hamilton became a medical consultant to the U.S. Division of Labor Standards. Her last field survey, which was made in 1937–38, investigated the viscose rayon industry. In addition, Hamilton served as president of the National Consumers League from 1944 to 1949. Hamilton spent her retirement years inHadlyme, Connecticut

The Hadlyme North Historic District is an Historic district (United States), historic district located in the southwest corner of the town of East Haddam, Connecticut (just north of the town line with Lyme, Connecticut, Lyme). It represents the ...

, at the home she had purchased in 1916 with her sister, Margaret. Hamilton remained an active writer in retirement. Her autobiography, ''Exploring the Dangerous Trades'', was published in 1943. Hamilton and coauthor Harriet Louise Hardy

Harriet Louise Hardy (September 23, 1906 - October 13, 1993) was an American pioneer in occupational medicine and the first woman professor at Harvard Medical School. Her main points of study were toxicology and environmental related illness. S ...

also revised ''Industrial Toxicology'' (1949), the textbook that Hamilton had initially written in 1934. Hamilton also enjoyed leisure activities such as reading, sketching, and writing, as well as spending time among her family and friends.

Death and legacy

Hamilton died of a stroke at her home inHadlyme, Connecticut

The Hadlyme North Historic District is an Historic district (United States), historic district located in the southwest corner of the town of East Haddam, Connecticut (just north of the town line with Lyme, Connecticut, Lyme). It represents the ...

, on September 22, 1970, at the age of 101.Sicherman and Green, p. 306. She is buried at Cove Cemetery in Hadlyme.

Hamilton was a tireless researcher and crusader against the use of toxic substances in the workplace. Within three months of her death in 1970, the U.S. Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washin ...

passed the Occupational Safety and Health Act

The Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 is a US labor law governing the federal law of occupational health and safety in the private sector and federal government in the United States. It was enacted by Congress in 1970 and was signed by P ...

to improve workplace safety in the United States.Weber, p. 39.

Recognition and awards

* Hamilton was awarded honorary degrees from the University of Michigan,Mount Holyoke College

Mount Holyoke College is a private liberal arts women's college in South Hadley, Massachusetts. It is the oldest member of the historic Seven Sisters colleges, a group of elite historically women's colleges in the Northeastern United States. ...

, and Smith College

Smith College is a private liberal arts women's college in Northampton, Massachusetts. It was chartered in 1871 by Sophia Smith and opened in 1875. It is the largest member of the historic Seven Sisters colleges, a group of elite women's coll ...

.

* She was included in the ''American Men in Science: A Biographical Dictionary'' (1906).

* In 1935 Eleanor Roosevelt

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt () (October 11, 1884November 7, 1962) was an American political figure, diplomat, and activist. She was the first lady of the United States from 1933 to 1945, during her husband President Franklin D. Roosevelt's four ...

presented Hamilton with the Chi Omega

Chi Omega (, also known as ChiO) is a women's fraternity and a member of the National Panhellenic Conference, the umbrella organization of 26 women's fraternities.

Chi Omega has 181 active collegiate chapters and approximately 240 alumnae chap ...

women's fraternity's National Achievement Award.

* In 1947 Hamilton became the first woman to receive the Albert Lasker Public Service Award

The Lasker-Bloomberg Public Service Award, known until 2009 as the Mary Woodard Lasker Public Service Award, is awarded by the Lasker Foundation to honor an individual or organization whose public service has profoundly enlarged the possibilities f ...

for her public service contributions.

* In 1948 Hamilton received the Donald E. Cummings Memorial Awards from the American Industrial Hygiene Association. In 1993, the organization established an award in her honor to recognize the contributions of outstanding women in the field of occupational and environmental hygiene.

* In 1956 she was named ''TIME'' magazine's "Woman of the Year" in medicine.

* In 1973 Hamilton was posthumously inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame

The National Women's Hall of Fame (NWHF) is an American institution incorporated in 1969 by a group of men and women in Seneca Falls, New York, although it did not induct its first enshrinees until 1973. As of 2021, it had 303 inductees.

Induc ...

.

* On February 27, 1987, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH, ) is the United States federal agency responsible for conducting research and making recommendations for the prevention of work-related injury and illness. NIOSH is part of the C ...

dedicated its research facility as the Alice Hamilton Laboratory for Occupational Safety and Health. The institute also began giving an annual Alice Hamilton Award to recognize excellent scientific research in the field.

* In 1995 the U.S. Postal Service honored Hamilton's contributions to public health

Public health is "the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through the organized efforts and informed choices of society, organizations, public and private, communities and individuals". Analyzing the det ...

with a 55-cent commemorative postage stamp in its Great Americans series

The Great Americans series is a set of definitive stamps issued by the United States Postal Service, starting on December 27, 1980, with the 19¢ stamp depicting Sequoyah, and continuing through 1999, the final stamp being the 55¢ Justin S. Morr ...

.

* In 2000 the city of Fort Wayne, Indiana, erected statues of Alice, her sister, Edith, and their cousin, Agnes, in the city's Headwaters Park.

* On September 21, 2002, the American Chemical Society

The American Chemical Society (ACS) is a scientific society based in the United States that supports scientific inquiry in the field of chemistry. Founded in 1876 at New York University, the ACS currently has more than 155,000 members at all ...

designated Hamilton and her work in industrial toxicology a National Historic Chemical Landmark in recognition of her pioneering role in the development of occupational medicine.

* Hamilton has been heralded as a pioneering female environmentalist. The Division of Occupational and Environmental Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, sponsors an annual lecture named in recognition of her achievements in these areas. Since 1997 the American Society for Environmental History has annually awarded the Alice Hamilton Prize for the best article published outside the ''Environmental History'' journal.

* On September 26, 2018, one bust of Alice Hamilton was placed in the foyer of the François-Xavier Bagnoud Building of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and another bust, also by local sculptor Robert Shure, was placed in the Atrium in the Tosteson Medical Education Center of the Harvard Medical School

Harvard Medical School (HMS) is the graduate medical school of Harvard University and is located in the Longwood Medical Area of Boston, Massachusetts. Founded in 1782, HMS is one of the oldest medical schools in the United States and is cons ...

.

* Annually, the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health's Committee on the Advancement of Women Faculty (CAWF) sponsors the annual Alice Hamilton lecture and award to recognize especially promising junior faculty women.

Selected published works

Books: * ''Industrial Poisons in the United States'' (1925) * ''Industrial Toxicology'' (1934’ rev. 1949) * ''Exploring the Dangerous Trades: The Autobiography of Alice Hamilton, M.D.'' (1943). Articles: * "Hitler Speaks: His Book Reveals the Man," ''Atlantic Monthly'' (April 1933) * "The Youth Who Are Hitler's Strength," ''New York Times'', 1933 * "A Woman of Ninety Looks at Her World," ''Atlantic Monthly'' (1961)Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Jay, Stephen J., "Alice Hamilton" in * * * * (Second publishing: University of Illinois Press, 2003. ) * Sicherman, Barbara, "Sense and Sensibility: A Case Study of Women's Victorian America," in * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * * * * (Second publishing- University of Illinois Press, 2003. ) *External links

The Woman Who Founded Industrial Medicine

Scientific American, October 23, 2019

Hamilton, Alice, 1869-1970. Papers of Alice Hamilton, 1909-1987 (inclusive), 1909-1965 (bulk): A Finding Aid

, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University. *

Alice Hamilton in The Connecticut Women's Hall of Fame

at The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

Alice Hamilton, M.D.

– Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

Exploring the Dangerous Trades Excerpt

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hamilton, Alice American occupational health practitioners 1869 births 1970 deaths Johns Hopkins University alumni Harvard University faculty American centenarians American democratic socialists American women physicians American toxicologists American pacifists Northwestern University faculty Industrial hygiene University of Michigan Medical School alumni Physicians from New York City People from Fort Wayne, Indiana Women centenarians Miss Porter's School alumni International Congress of Women people American women academics American people of Scotch-Irish descent