Algoman orogeny on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Algoman orogeny, known as the Kenoran orogeny in Canada, was an episode of mountain-building (

The Algoman orogeny, known as the Kenoran orogeny in Canada, was an episode of mountain-building (

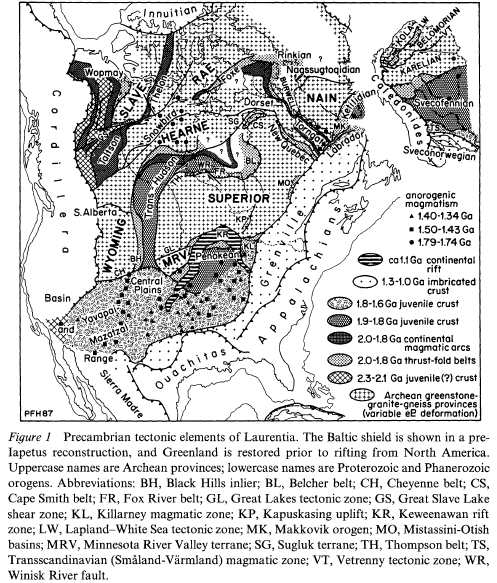

The Superior province forms the core of both the North American continent and the Canadian shield, and has a thickness of at least . Its granites date from 2,700 to 2,500 million years ago. It was formed by the welding together of many small

The Superior province forms the core of both the North American continent and the Canadian shield, and has a thickness of at least . Its granites date from 2,700 to 2,500 million years ago. It was formed by the welding together of many small

The Wabigoon subprovince is a formerly active volcanic island chain, made up of metavolcanic-metasedimentary intrusions. These metamorphosed rocks are volcanically derived greenstone belts, and are surrounded and cut by granitic plutons and batholiths. The subprovince's greenstone belts consist of felsic volcanics, felsic batholiths and felsic plutons aged from 3,000 to 2,670 million years old.

The Wabigoon subprovince is a formerly active volcanic island chain, made up of metavolcanic-metasedimentary intrusions. These metamorphosed rocks are volcanically derived greenstone belts, and are surrounded and cut by granitic plutons and batholiths. The subprovince's greenstone belts consist of felsic volcanics, felsic batholiths and felsic plutons aged from 3,000 to 2,670 million years old.

In extensive regions of the Slave province of northern Canada, the magma that later became batholiths heated the surrounding rock to create metamorphic regions called ''aureoles'' about 2,575 million years ago. These regions are typically wide. The creation of aureoles was a continuous process, but three recognizable metamorphic phases can be correlated with established deformational phases. The cycle began with a deformation phase unaccompanied by metamorphism. This evolved into the second phase accompanied by broad regional metamorphism as thermal doming began. With continued updoming of the isotherms, the third phase produced minor folding but caused major metamorphic recrystallization, resulting in the emplacement of granite at the core of the thermal dome. This phase occurred at lower pressure because of erosional unloading, but the temperatures were more extreme, ranging up to about . With deformation complete, the thermal dome decayed; minor mineralogical changes occurred during this decay phase. The region has since been effectively stable.

Geochronology of several Archean rock units establishes a sequence of events, approximately 75 million years in duration, leading to the formation of a new crustal segment. The oldest rocks, at 2,650 million years old, are basic metavolcanics with largely calc-alkaline characteristics. Radiometric dating indicates ages of 2,640 to 2,620 million years are recorded for the syn-kinematic

In extensive regions of the Slave province of northern Canada, the magma that later became batholiths heated the surrounding rock to create metamorphic regions called ''aureoles'' about 2,575 million years ago. These regions are typically wide. The creation of aureoles was a continuous process, but three recognizable metamorphic phases can be correlated with established deformational phases. The cycle began with a deformation phase unaccompanied by metamorphism. This evolved into the second phase accompanied by broad regional metamorphism as thermal doming began. With continued updoming of the isotherms, the third phase produced minor folding but caused major metamorphic recrystallization, resulting in the emplacement of granite at the core of the thermal dome. This phase occurred at lower pressure because of erosional unloading, but the temperatures were more extreme, ranging up to about . With deformation complete, the thermal dome decayed; minor mineralogical changes occurred during this decay phase. The region has since been effectively stable.

Geochronology of several Archean rock units establishes a sequence of events, approximately 75 million years in duration, leading to the formation of a new crustal segment. The oldest rocks, at 2,650 million years old, are basic metavolcanics with largely calc-alkaline characteristics. Radiometric dating indicates ages of 2,640 to 2,620 million years are recorded for the syn-kinematic

The Algoman orogeny, known as the Kenoran orogeny in Canada, was an episode of mountain-building (

The Algoman orogeny, known as the Kenoran orogeny in Canada, was an episode of mountain-building (orogeny

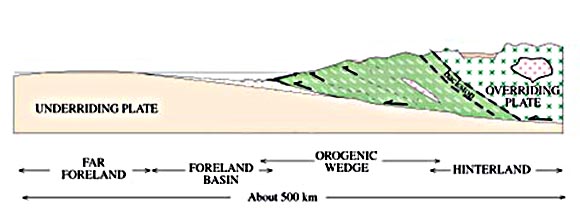

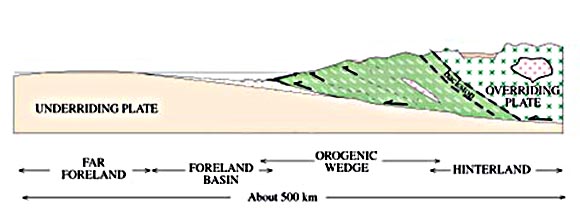

Orogeny is a mountain building process. An orogeny is an event that takes place at a convergent plate margin when plate motion compresses the margin. An '' orogenic belt'' or ''orogen'' develops as the compressed plate crumples and is uplifted ...

) during the Late Archean

The Archean Eon ( , also spelled Archaean or Archæan) is the second of four geologic eons of Earth's history, representing the time from . The Archean was preceded by the Hadean Eon and followed by the Proterozoic.

The Earth during the Arc ...

Eon that involved repeated episodes of continental collision

In geology, continental collision is a phenomenon of plate tectonics that occurs at convergent boundaries. Continental collision is a variation on the fundamental process of subduction, whereby the subduction zone is destroyed, mountains produ ...

s, compressions and subduction

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at convergent boundaries. Where the oceanic lithosphere of a tectonic plate converges with the less dense lithosphere of a second plate, ...

s. The Superior province and the Minnesota River Valley terrane

In geology, a terrane (; in full, a tectonostratigraphic terrane) is a crust fragment formed on a tectonic plate (or broken off from it) and accreted or " sutured" to crust lying on another plate. The crustal block or fragment preserves its ow ...

collided about 2,700 to 2,500 million years ago. The collision folded the Earth's crust and produced enough heat and pressure to metamorphose the rock. Blocks were added to the Superior province along a boundary that stretches from present-day eastern South Dakota into the Lake Huron area. The Algoman orogeny brought the Archean Eon to a close, about ; it lasted less than 100 million years and marks a major change in the development of the Earth's crust.

The Canadian shield

The Canadian Shield (french: Bouclier canadien ), also called the Laurentian Plateau, is a geologic shield, a large area of exposed Precambrian igneous and high-grade metamorphic rocks. It forms the North American Craton (or Laurentia), the anc ...

contains belts of metavolcanic and metasedimentary

In geology, metasedimentary rock is a type of metamorphic rock. Such a rock was first formed through the deposition and solidification of sediment

Sediment is a naturally occurring material that is broken down by processes of weathering and e ...

rocks formed by the action of metamorphism on volcanic and sedimentary rock. The areas between individual belts consist of granite

Granite () is a coarse-grained ( phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies un ...

s or granitic gneisses that form fault zone

In geology, a fault is a planar fracture or discontinuity in a volume of rock across which there has been significant displacement as a result of rock-mass movements. Large faults within Earth's crust result from the action of plate tectoni ...

s. These two types of belts can be seen in the Wabigoon, Quetico and Wawa subprovince

A province is almost always an administrative division within a country or state. The term derives from the ancient Roman ''provincia'', which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire's territorial possessions out ...

s; the Wabigoon and Wawa are of volcanic origin and the Quetico is of sedimentary origin. These three subprovinces lie linearly in southwestern- to northeastern-oriented belts about wide on the southern portion of the Superior Province.

The Slave province and portions of the Nain province

In Labrador, Canada, the North Atlantic Craton is known as the Nain Province. The Nain geologic province was intruded by the Nain Plutonic Suite, which divides the province into the northern Saglek block and the southern Hopedale block.

North ...

were also affected. Between about 2,000 and these combined with the Sask and Wyoming

Wyoming () is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the southwest, and Colorado to t ...

craton

A craton (, , or ; from grc-gre, κράτος "strength") is an old and stable part of the continental lithosphere, which consists of Earth's two topmost layers, the crust and the uppermost mantle. Having often survived cycles of merging and ...

s to form the first supercontinent

In geology, a supercontinent is the assembly of most or all of Earth's continental blocks or cratons to form a single large landmass. However, some geologists use a different definition, "a grouping of formerly dispersed continents", which leav ...

, the Kenorland

Kenorland was one of the earliest known supercontinents on Earth. It is thought to have formed during the Neoarchaean Era c. 2.72 billion years ago (2.72 Ga) by the accretion of Neoarchaean cratons and the formation of new continental crust. ...

supercontinent.

Overview

Through most of theArchean

The Archean Eon ( , also spelled Archaean or Archæan) is the second of four geologic eons of Earth's history, representing the time from . The Archean was preceded by the Hadean Eon and followed by the Proterozoic.

The Earth during the Arc ...

Eon, the Earth had a heat production at least twice that of the present. The timing of initiation of plate tectonics is still debated, but if modern-day tectonics were operative in the Archean, higher heat fluxes might have caused tectonic

Tectonics (; ) are the processes that control the structure and properties of the Earth's crust and its evolution through time. These include the processes of mountain building, the growth and behavior of the strong, old cores of continents ...

processes to be more active. As a result, plates and continents may have been smaller. No broad blocks as old as 3 Ga are found in Precambrian

The Precambrian (or Pre-Cambrian, sometimes abbreviated pꞒ, or Cryptozoic) is the earliest part of Earth's history, set before the current Phanerozoic Eon. The Precambrian is so named because it preceded the Cambrian, the first period of th ...

shields. Toward the end of the Archean, however, some of these blocks or ''terranes

In geology, a terrane (; in full, a tectonostratigraphic terrane) is a crust fragment formed on a tectonic plate (or broken off from it) and accreted or " sutured" to crust lying on another plate. The crustal block or fragment preserves its own ...

'' came together to form larger blocks welded together by greenstone belts

Greenstone belts are zones of variably metamorphosed mafic to ultramafic volcanic sequences with associated sedimentary rocks that occur within Archaean and Proterozoic cratons between granite and gneiss bodies.

The name comes from the green h ...

.

Two such terranes that now form part of the Canadian shield

The Canadian Shield (french: Bouclier canadien ), also called the Laurentian Plateau, is a geologic shield, a large area of exposed Precambrian igneous and high-grade metamorphic rocks. It forms the North American Craton (or Laurentia), the anc ...

collided about . These were the Superior province and the large Minnesota River Valley terrane, the former composed mainly of granite

Granite () is a coarse-grained ( phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies un ...

and the latter of gneiss

Gneiss ( ) is a common and widely distributed type of metamorphic rock. It is formed by high-temperature and high-pressure metamorphic processes acting on formations composed of igneous or sedimentary rocks. Gneiss forms at higher temperatures a ...

. This led to the mountain-building episode known as the ''Algoman orogeny'' in the U. S. (named for Algoma, Kewaunee County, Wisconsin

Kewaunee County is a county located in the U.S. state of Wisconsin. As of the 2020 census, the population was 20,563. Its county seat is Kewaunee. The county was created in 1852 and organized in 1859. Its Menominee name is ''Kewāneh'', an a ...

), and the ''Kenoran orogeny'' in Canada. Its duration is estimated at 50 to 100 million years. The current boundary between these terranes is known as the Great Lakes tectonic zone (GLTZ). This zone is wide and extends in a line roughly 1,200 kilometers long from the middle of South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state in the North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Lakota and Dakota Sioux Native American tribes, who comprise a large po ...

, east through the middle of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan

The Upper Peninsula of Michigan – also known as Upper Michigan or colloquially the U.P. – is the northern and more elevated of the two major landmasses that make up the U.S. state of Michigan; it is separated from the Lower Peninsula by ...

, into the Sudbury, Ontario

Sudbury, officially the City of Greater Sudbury is the largest city in Northern Ontario by population, with a population of 166,004 at the 2021 Canadian Census. By land area, it is the largest in Ontario and the fifth largest in Canada. It is a ...

region. The region remains slightly active today. Rift

In geology, a rift is a linear zone where the lithosphere is being pulled apart and is an example of extensional tectonics.

Typical rift features are a central linear downfaulted depression, called a graben, or more commonly a half-grabe ...

ing in the GLTZ began about at the end of the Algoman orogeny.

The orogeny affected adjacent regions of northern Minnesota and Ontario in the Superior province as well as the Slave

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

and the eastern part of the Nain province

In Labrador, Canada, the North Atlantic Craton is known as the Nain Province. The Nain geologic province was intruded by the Nain Plutonic Suite, which divides the province into the northern Saglek block and the southern Hopedale block.

North ...

, a far wider region of influence than in subsequent orogenies. It is the earliest datable orogeny in North America and brought the Archean Eon to a close. The end of the Archean Eon marks a major change in the development of the Earth's crust

Earth's crust is Earth's thin outer shell of rock, referring to less than 1% of Earth's radius and volume. It is the top component of the lithosphere, a division of Earth's layers that includes the crust and the upper part of the mantle. The ...

: the crust was essentially formed and achieved thicknesses of about under the continents.

Tectonics

The collision between terranes folded the Earth's crust, and produced enough heat and pressure to metamorphose then-existing rock. Repeated continental collisions, compression along a north–south axis, andsubduction

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at convergent boundaries. Where the oceanic lithosphere of a tectonic plate converges with the less dense lithosphere of a second plate, ...

resulted in the uprising of the Algoman Mountains. This was followed by intrusions of granite

Granite () is a coarse-grained ( phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies un ...

pluton

In geology, an igneous intrusion (or intrusive body or simply intrusion) is a body of intrusive igneous rock that forms by crystallization of magma slowly cooling below the surface of the Earth. Intrusions have a wide variety of forms and com ...

s and batholithic domes within the gneisses about ; two examples are the Sacred Heart granite of southwestern Minnesota and the Watersmeet Domes metagabbros (metamorphosed gabbro

Gabbro () is a phaneritic (coarse-grained), mafic intrusive igneous rock formed from the slow cooling of magnesium-rich and iron-rich magma into a holocrystalline mass deep beneath the Earth's surface. Slow-cooling, coarse-grained gabbro is ...

s) that straddle the border of Wisconsin and Michigan's Upper Peninsula

The Upper Peninsula of Michigan – also known as Upper Michigan or colloquially the U.P. – is the northern and more elevated of the two major landmasses that make up the U.S. state of Michigan; it is separated from the Lower Peninsula by ...

. After the intrusions solidified, new stresses on the greenstone belt caused movement horizontally along several faults and moved huge blocks of the crust vertically relative to adjacent blocks. This combination of folding, intrusion and faulting built mountain ranges throughout northern Minnesota, northern Wisconsin, Michigan's Upper Peninsula and southernmost Ontario. Igneous and high-grade metamorphic rocks are associated with the orogeny.

By extrapolating the now-eroded and tilted beds upward, geologists have determined that these mountains were several kilometers high. Similar projections of the tilted beds downward, coupled with geophysical measurements on the greenstone belts in Canada, suggest the metavolcanic and metasedimentary rocks of the belts project downward at least a few kilometers.

Greenstone

The action of metamorphism on the border between granite and gneiss bodies produces a succession of metamorphosed volcanic and sedimentary rocks calledgreenstone belts

Greenstone belts are zones of variably metamorphosed mafic to ultramafic volcanic sequences with associated sedimentary rocks that occur within Archaean and Proterozoic cratons between granite and gneiss bodies.

The name comes from the green h ...

. Most Archean volcanic rocks are concentrated within greenstone belts; the green color comes from minerals, such as chlorite

The chlorite ion, or chlorine dioxide anion, is the halite with the chemical formula of . A chlorite (compound) is a compound that contains this group, with chlorine in the oxidation state of +3. Chlorites are also known as salts of chlorou ...

, epidote

Epidote is a calcium aluminium iron sorosilicate mineral.

Description

Well developed crystals of epidote, Ca2Al2(Fe3+;Al)(SiO4)(Si2O7)O(OH), crystallizing in the monoclinic system, are of frequent occurrence: they are commonly prismatic in ...

and actinolite

Actinolite is an amphibole silicate mineral with the chemical formula .

Etymology

The name ''actinolite'' is derived from the Greek word ''aktis'' (), meaning "beam" or "ray", because of the mineral's fibrous nature.

Mineralogy

Actinolite is ...

that formed during metamorphism. After metamorphism occurred, these rocks were folded and faulted into a system of mountains by the Algoman orogeny.

The volcanic beds are thick. About the greenstone belt was subjected to new stresses that caused movement along several faults. Faulting on both small and large scales is typical of greenstone belt deformation. These faults show both vertical and horizontal movement relative to adjacent blocks. Large-scale faults typically occur along the margins of the greenstone belts where they are in contact with enclosed granitic rocks. Vertical movement may be thousands of meters and horizontal movements of many kilometers occur along some fault zones.

Some time before , masses of magma

Magma () is the molten or semi-molten natural material from which all igneous rocks are formed. Magma is found beneath the surface of the Earth, and evidence of magmatism has also been discovered on other terrestrial planets and some natura ...

intruded under and within the igneous

Igneous rock (derived from the Latin word ''ignis'' meaning fire), or magmatic rock, is one of the three main rock types, the others being sedimentary and metamorphic. Igneous rock is formed through the cooling and solidification of magma or ...

and sedimentary rocks, heating and pressing the rocks to metamorphose them into hard greenish greenstones. They began with fissure eruptions of basalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the surface of a rocky planet or moon. More than 90 ...

, continued with intermediate and felsic

In geology, felsic is a modifier describing igneous rocks that are relatively rich in elements that form feldspar and quartz.Marshak, Stephen, 2009, ''Essentials of Geology,'' W. W. Norton & Company, 3rd ed. It is contrasted with mafic rocks, wh ...

rocks erupted from volcanic centers and ended with deposition of sediments from the erosion of the volcanic pile. The rising magma was extruded under a shallow ancient sea where it cooled to form pillowed greenstones. Some of Minnesota's pillows probably cooled at depths as great as and contain no gas cavities or vesicles

Vesicle may refer to:

; In cellular biology or chemistry

* Vesicle (biology and chemistry), a supramolecular assembly of lipid molecules, like a cell membrane

* Synaptic vesicle

; In human embryology

* Vesicle (embryology), bulge-like features o ...

.

Most greenstone belts, with all of their components, have been folded into troughlike synclines

In structural geology, a syncline is a fold with younger layers closer to the center of the structure, whereas an anticline is the inverse of a syncline. A synclinorium (plural synclinoriums or synclinoria) is a large syncline with superimpose ...

; the original basaltic rock, which was on the bottom, occurs on the outer margins of the trough. The overlying, younger rock units – rhyolite

Rhyolite ( ) is the most silica-rich of volcanic rocks. It is generally glassy or fine-grained (aphanitic) in texture, but may be porphyritic, containing larger mineral crystals ( phenocrysts) in an otherwise fine-grained groundmass. The miner ...

s and greywackes – occur closer to the center of the syncline. The rocks are so intensely folded that most have been tilted nearly 90°, with the tops of layers on one side of the synclinal belt facing those on the other side; the rock sequences are in effect lying on their sides. The folding can be so complex that a single layer may be exposed at the surface many times by subsequent erosion.

Volcanic activity

As the greenstone belts were forming, volcanoes ejectedtephra

Tephra is fragmental material produced by a volcanic eruption regardless of composition, fragment size, or emplacement mechanism.

Volcanologists also refer to airborne fragments as pyroclasts. Once clasts have fallen to the ground, they r ...

into the air which settled as sediments to become compacted into the greywacke

Greywacke or graywacke (German ''grauwacke'', signifying a grey, earthy rock) is a variety of sandstone generally characterized by its hardness, dark color, and poorly sorted angular grains of quartz, feldspar, and small rock fragments or lit ...

s and mudstone

Mudstone, a type of mudrock, is a fine-grained sedimentary rock whose original constituents were clays or muds. Mudstone is distinguished from '' shale'' by its lack of fissility (parallel layering).Blatt, H., and R.J. Tracy, 1996, ''Petrology.' ...

s of the Knife Lake and Lake Vermilion formations. Greywackes are poorly sorted mixtures of clay

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4).

Clays develop plasticity when wet, due to a molecular film of water surrounding the clay pa ...

, mica

Micas ( ) are a group of silicate minerals whose outstanding physical characteristic is that individual mica crystals can easily be split into extremely thin elastic plates. This characteristic is described as perfect basal cleavage. Mica is ...

and quartz

Quartz is a hard, crystalline mineral composed of silica ( silicon dioxide). The atoms are linked in a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon-oxygen tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tetrahedra, giving an overall chemical f ...

that may be derived from the decomposition of pyroclastic

Pyroclastic rocks (derived from the el, πῦρ, links=no, meaning fire; and , meaning broken) are clastic rocks composed of rock fragments produced and ejected by explosive volcanic eruptions. The individual rock fragments are known as pyroc ...

debris; the presence of this debris suggests that some explosive volcanic activity had occurred in the area earlier. The volcanism took place on the surface and the other deformations took place at various depths. Numerous earthquakes accompanied the volcanism

Volcanism, vulcanism or volcanicity is the phenomenon of eruption of molten rock (magma) onto the surface of the Earth or a solid-surface planet or moon, where lava, pyroclastics, and volcanic gases erupt through a break in the surface called a ...

and faulting.

Superior province

terranes

In geology, a terrane (; in full, a tectonostratigraphic terrane) is a crust fragment formed on a tectonic plate (or broken off from it) and accreted or " sutured" to crust lying on another plate. The crustal block or fragment preserves its own ...

, the ages of which decrease away from the nucleus. This progression is illustrated by the age of the Wabigoon, Quetico and Wawa subprovinces, discussed in their individual sections. Later terranes docked on the periphery of continental masses with geosyncline

A geosyncline (originally called a geosynclinal) is an obsolete geological concept to explain orogens, which was developed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, before the theory of plate tectonics was envisaged. Şengör (1982), p. 11 A geo ...

s developing between the fused nuclei and oceanic crust. In general the Superior province consists of east–west-trending belts of predominately volcanic rocks alternating with belts of sedimentary and gneissic rocks.

Due to down warping along elongate zones, each belt is essentially a large downfold or downfaulted block. The areas between individual belts are fault zones consisting of granite or granitic gneiss. Its western part contains a regional pattern of east–west-trending wide granitic greenstone and metasedimentary belts (subprovinces). Western Superior province's mantle has remained intact since the 2,700-million-year-ago accretion of the subprovinces.

Both folding and faulting can be seen in the Wabigoon, Quetico and Wawa subprovinces. These three subprovinces lie linearly in southwestern- to northeastern-oriented belts of about wide (see figure on right). The northernmost and widest province is the Wabigoon. It begins in north-central Minnesota and continues northeasterly into central Ontario; it is partially interrupted by the Southern province. Immediately to the south, the Quetico subprovince extends as far west in north-central Minnesota, and extends further to the northeast. It is completely interrupted by a narrow band of the 1,100- to 1,550-million-year-old Southern province to the northeast of Thunder Bay

Thunder Bay is a city in and the seat of Thunder Bay District, Ontario, Canada. It is the most populous municipality in Northwestern Ontario and the second most populous (after Greater Sudbury) municipality in Northern Ontario; its populati ...

. The Wawa subprovince is the most southerly of the three; it begins in central Minnesota, continues northeast to Thunder Bay, Ontario, Canada, (where its southern border just skims north Thunder Bay) and then extends east beyond Lake Superior. The northern boundary continues in a roughly northeasterly heading, while the southern border dips south to follow the northeast shore of Lake Superior.

Fault zones

The three subprovinces are separated by steeply dippingshear zones

Boudinaged quartz vein (with strain fringe) showing ''Fault (geology)">sinistral shear sense'', Starlight Pit, Fortnum Gold Mine, Western Australia

In geology, shear is the response of a rock to deformation usually by compressive stress and f ...

caused by continued compression that occurred during the Algoman orogeny. These boundaries are major fault zones.

The boundary between the Wabigoon and Quetico subprovinces seems to have been also controlled by colliding plates and subsequent transpression

In geology, transpression is a type of strike-slip deformation that deviates from simple shear because of a simultaneous component of shortening perpendicular to the fault plane. This movement ends up resulting in oblique shear. It is generally ve ...

s. This Rainy Lake – Seine River fault zone is a major northeast–southwest trending strike-slip

In geology, a fault is a planar fracture or discontinuity in a volume of rock across which there has been significant displacement as a result of rock-mass movements. Large faults within Earth's crust result from the action of plate tectonic ...

fault zone; it trends N80°E to cut through the northwest part of Voyageurs National Park

Voyageurs National Park is an American national park in northern Minnesota near the city of International Falls established in 1975. The park's name commemorates the ''voyageurs''—French-Canadian fur traders who were the first European settle ...

in Minnesota and extends westward to near International Falls, Minnesota and Fort Frances

Fort Frances is a town in, and the seat of, Rainy River District in Northwestern Ontario, Canada. The population as of the 2016 census was 7,739. Fort Frances is a popular fishing destination. It hosts the annual Fort Frances Canadian Bass Cha ...

, Ontario. The fault has transported rocks in the greenstone belt a considerable distance from their origin. The greenstone belt is wide at the Seven Sisters Islands; to the west the greenstone interfingers with pods of anorthositic

Anorthosite () is a phaneritic, intrusive igneous rock characterized by its composition: mostly plagioclase feldspar (90–100%), with a minimal mafic component (0–10%). Pyroxene, ilmenite, magnetite, and olivine are the mafic minera ...

gabbro

Gabbro () is a phaneritic (coarse-grained), mafic intrusive igneous rock formed from the slow cooling of magnesium-rich and iron-rich magma into a holocrystalline mass deep beneath the Earth's surface. Slow-cooling, coarse-grained gabbro is ...

. Radiometric dating

Radiometric dating, radioactive dating or radioisotope dating is a technique which is used to date materials such as rocks or carbon, in which trace radioactive impurities were selectively incorporated when they were formed. The method compares ...

from the Rainy Lake area in Ontario show an age of about 2,700 million years old, which favors a moving tectonic plate model for the formation of the boundary.

The largest fault is the Vermilion fault separating the Quetico and Wawa subprovinces. It has a N40°E trend and was caused by the introduction of masses of magma. The Vermilion fault can be traced westward to North Dakota. It has had a horizontal movement with the northern block moving eastward and upward relative to the southern block. The junction between the Quetico and Wawa subprovinces has a zone of biotite

Biotite is a common group of phyllosilicate minerals within the mica group, with the approximate chemical formula . It is primarily a solid-solution series between the iron- endmember annite, and the magnesium-endmember phlogopite; more ...

-rich migmatite

Migmatite is a composite rock found in medium and high-grade metamorphic environments, commonly within Precambrian cratonic blocks. It consists of two or more constituents often layered repetitively: one layer is an older metamorphic rock th ...

, a rock that has characteristics of both igneous and metamorphic processes; this indicates a zone of partial melting which is possible only under high temperature and pressure conditions. It is visible as a wide belt. Most of the flattened large crystals in the fault indicate a simple compression rather than a wrenching, shearing or rotational event as the two subprovinces docked. This provides evidence that the Quetico and Wawa subprovinces were joined by the collision of two continental plates, about . Structures in the migmatite include folds and foliation

In mathematics (differential geometry), a foliation is an equivalence relation on an ''n''-manifold, the equivalence classes being connected, injectively immersed submanifolds, all of the same dimension ''p'', modeled on the decomposition of ...

s; the foliations cut across both limbs of earlier-phase folds. These cross-cutting foliations indicate that the migmatite has undergone at least two periods of ductile deformation.

Wabigoon subprovince

The Wabigoon subprovince is a formerly active volcanic island chain, made up of metavolcanic-metasedimentary intrusions. These metamorphosed rocks are volcanically derived greenstone belts, and are surrounded and cut by granitic plutons and batholiths. The subprovince's greenstone belts consist of felsic volcanics, felsic batholiths and felsic plutons aged from 3,000 to 2,670 million years old.

The Wabigoon subprovince is a formerly active volcanic island chain, made up of metavolcanic-metasedimentary intrusions. These metamorphosed rocks are volcanically derived greenstone belts, and are surrounded and cut by granitic plutons and batholiths. The subprovince's greenstone belts consist of felsic volcanics, felsic batholiths and felsic plutons aged from 3,000 to 2,670 million years old.

Quetico subprovince

The Quetico gneiss belt extends some across Ontario and parts of Minnesota. The dominant rocks within the belt areschist

Schist ( ) is a medium-grained metamorphic rock showing pronounced schistosity. This means that the rock is composed of mineral grains easily seen with a low-power hand lens, oriented in such a way that the rock is easily split into thin flakes ...

s and gneisses produced by intense metamorphism of greywackes and minor amounts of other sedimentary rocks. The sediments, alkalic plutons and felsic

In geology, felsic is a modifier describing igneous rocks that are relatively rich in elements that form feldspar and quartz.Marshak, Stephen, 2009, ''Essentials of Geology,'' W. W. Norton & Company, 3rd ed. It is contrasted with mafic rocks, wh ...

plutons are aged from 2,690 to 2,680 million years. The metamorphism is relatively low-grade on the margins and high-grade in the center. The low-grade components of the greywackes were derived primarily from volcanic rocks; the high-grade rocks are coarser-grained and contain minerals that reflect higher temperatures. The granitic intrusions within the high-grade metasediments were produced by subduction of the ocean crust and partial melting of metasedimentary rocks. Immediately south of Voyageurs National Park and extending to the Vermilion fault is a broad transition zone that contains migmatite.

The Quetico gneiss belt represents an accretionary wedge that formed in a trench during the collision of several island arc

Island arcs are long chains of active volcanoes with intense seismic activity found along convergent tectonic plate boundaries. Most island arcs originate on oceanic crust and have resulted from the descent of the lithosphere into the mantle alon ...

s (greenstone belts). Boundaries between the gneiss belt and the flanking greenstone belts to the north and south are major fault zones, the Vermilion and Rainy Lake – Seine River fault zones.

Wawa subprovince

The Wawa subprovince is a formerly active volcanic island chain, consisting of metamorphosed greenstone belts which are surrounded by and cut by granitic plutons and batholiths. These greenstone belts consist of felsic volcanics, felsic batholiths, felsic plutons and sediments aged from 2,700 to 2,670 million years old. The predominant rock type is a white, coarse-grained, foliatedhornblende

Hornblende is a complex inosilicate series of minerals. It is not a recognized mineral in its own right, but the name is used as a general or field term, to refer to a dark amphibole. Hornblende minerals are common in igneous and metamorphic rock ...

tonalite. Minerals in the tonalite

Tonalite is an igneous, plutonic ( intrusive) rock, of felsic composition, with phaneritic (coarse-grained) texture. Feldspar is present as plagioclase (typically oligoclase or andesine) with alkali feldspar making up less than 10% of the total ...

are quartz, plagioclase, alkali feldspar and hornblende.

Slave province

quartz diorite

Quartz diorite is an igneous, plutonic ( intrusive) rock, of felsic composition, with phaneritic texture. Feldspar is present as plagioclase (typically oligoclase or andesine) with 10% or less potassium feldspar. Quartz is present at between 5 an ...

batholiths and 2,590 to 2,100 million years for the major late-kinematic bodies. Pegmatitic adamellite

Quartz monzonite is an intrusive, felsic, igneous rock that has an approximately equal proportion of orthoclase and plagioclase feldspars. It is typically a light colored phaneritic (coarse-grained) to porphyritic granitic rock. The plagiocl ...

s, at 2,575±25 million years, are the youngest plutonic units.

Metagreywackes and metapelite

A pelite ( Greek: ''pelos'', "clay") or metapelite is a metamorphosed fine-grained sedimentary rock, i.e. mudstone or siltstone. The term was earlier used by geologists to describe a clay-rich, fine-grained clastic sediment or sedimentary rock, ...

s from two areas traversing one of these aureoles near Yellowknife

Yellowknife (; Dogrib: ) is the capital, largest community, and only city in the Northwest Territories, Canada. It is on the northern shore of Great Slave Lake, about south of the Arctic Circle, on the west side of Yellowknife Bay near the ...

have been studied. Most of the Slave province rocks are granitic with metamorphosed Yellowknife metasedimentary and volcanic rocks. Isotopic ages of these rocks is around , the time of the Kenoran orogeny. Rocks comprising the Slave province represent a high grade of metamorphism, intrusion and basement remobilization typical of Archean terranes. Migmatites, batholithic intrusive and granulitic metamorphic rocks show foliation and compositional banding; the rocks are uniformly hard and so thoroughly deformed that little foliation exists. Most Yellowknife Supergroup metasediments are tightly folded ( isoclinal) or occur in plunging anticline

In structural geology, an anticline is a type of fold that is an arch-like shape and has its oldest beds at its core, whereas a syncline is the inverse of an anticline. A typical anticline is convex up in which the hinge or crest is t ...

s.

Nain province

The Archean rocks forming the Nain province of northeastern Canada and Greenland are separated from the Superior terrane by a narrow band of remobilized rocks. Greenland separated from North America less than and its Precambrian terranes align with Canada's on the opposite side of Baffin Bay. The southern tip of Greenland is part of the Nain Province, this means it was connected to North America at the end of the Kenoran orogen.See also

*References

{{Authority control Geologic provinces Archean orogenies Terranes Geology of Ontario Geology of Minnesota Orogenies of North America