African Leopard on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The African leopard (''Panthera pardus pardus'') is the

''Felis pardus'' was the

''Felis pardus'' was the

The African leopard exhibits great variation in coat color, depending on location and habitat. Coat colour varies from pale yellow to deep gold or tawny, and sometimes

The African leopard exhibits great variation in coat color, depending on location and habitat. Coat colour varies from pale yellow to deep gold or tawny, and sometimes

The African leopards inhabited a wide range of habitats within

The African leopards inhabited a wide range of habitats within

Species portrait African leopard; IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group

Leopards .:. wild-cat.org — Information about research and conservation of leopards

The Cape Leopard Trust, South Africa

Safarinow.com: ''African Leopard » Panthera pardus » 'Luiperd

Image of a leopard from the Central African forests of Gabon

Predation on a child

at Queen Elizabeth National Park, Uganda {{Taxonbar, from=Q39153 African leopard African leopard Taxa named by Carl Linnaeus Mammals of Sub-Saharan Africa

nominate subspecies

In biological classification, subspecies is a rank below species, used for populations that live in different areas and vary in size, shape, or other physical characteristics ( morphology), but that can successfully interbreed. Not all speci ...

of the leopard

The leopard (''Panthera pardus'') is one of the five extant species in the genus '' Panthera'', a member of the cat family, Felidae. It occurs in a wide range in sub-Saharan Africa, in some parts of Western and Central Asia, Southern Russia, ...

, native to many countries in Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

. It is widely distributed in most of sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is, geographically, the area and regions of the continent of Africa that lies south of the Sahara. These include West Africa, East Africa, Central Africa, and Southern Africa. Geopolitically, in addition to the List of sov ...

, but the historical range has been fragmented in the course of habitat conversion. Leopards have also been recorded in North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

as well.

Taxonomy

''Felis pardus'' was the

''Felis pardus'' was the scientific name

In taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called nomenclature ("two-name naming system") or binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, bo ...

used by Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, ...

in the 10th edition of ''Systema Naturae'' in 1758. His description was based on descriptions by earlier naturalists such as Conrad Gessner. He assumed that the leopard occurred in India.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, several naturalists described various leopard skins and skulls from Africa, including:

* ''Felis pardus panthera'' proposed by Johann Christian Daniel von Schreber

Johann Christian Daniel von Schreber (17 January 1739 in Weißensee, Thuringia – 10 December 1810 in Erlangen), often styled J.C.D. von Schreber, was a German naturalist.

Career

He was appointed professor of'' materia medica'' at the Univer ...

in 1778 based on descriptions by earlier naturalists

* ''Felis leopardus'' var. ''melanotica'' by Albert Günther

Albert Karl Ludwig Gotthilf Günther FRS, also Albert Charles Lewis Gotthilf Günther (3 October 1830 – 1 February 1914), was a German-born British zoologist, ichthyologist, and herpetologist. Günther is ranked the second-most productive r ...

in 1885 from the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is ...

, Southern Africa

Southern Africa is the southernmost subregion of the African continent, south of the Congo and Tanzania. The physical location is the large part of Africa to the south of the extensive Congo River basin. Southern Africa is home to a number o ...

* ''Felis leopardus suahelicus'' by Oscar Neumann in 1900 from the Tanganyika territory

* ''Felis leopardus nanopardus'' by Oldfield Thomas

Michael Rogers Oldfield Thomas (21 February 1858 – 16 June 1929) was a British zoologist.

Career

Thomas worked at the Natural History Museum on mammals, describing about 2,000 new species and subspecies for the first time. He was appo ...

in 1904 from Italian Somaliland

Italian Somalia ( it, Somalia Italiana; ar, الصومال الإيطالي, Al-Sumal Al-Italiy; so, Dhulka Talyaaniga ee Soomaalida), was a protectorate and later colony of the Kingdom of Italy in present-day Somalia. Ruled in the 19th centu ...

* ''Felis pardus ruwenzorii'' by Lorenzo Camerano

Lorenzo Camerano (9 April 1856 Biella – 22 November 1917 Turin) was an Italian herpetologist and entomologist.

Born in Biella in 1856 he studied in Bologna and Torino, where he settled in order to take, between 1871 and 1873, a painting co ...

in 1906 from the Ruwenzori and Virunga Mountains

* ''Felis pardus chui'' by Edmund Heller

Edmund Heller (May 21, 1875 – July 18, 1939) was an American zoologist. He was President of the Association of Zoos & Aquariums for two terms, from 1935-1936 and 1937-1938.

Early life

While at Stanford University, he collected specimens in th ...

in 1913 from Uganda

}), is a landlocked country in East Africa. The country is bordered to the east by Kenya, to the north by South Sudan, to the west by the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to the south-west by Rwanda, and to the south by Tanzania. The ...

* ''Felis pardus iturensis'' by Joel Asaph Allen in 1924 from the Belgian Congo

The Belgian Congo (french: Congo belge, ; nl, Belgisch-Congo) was a Belgian colony in Central Africa from 1908 until independence in 1960. The former colony adopted its present name, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), in 1964.

Colo ...

* ''Felis pardus reichenowi'' by Ángel Cabrera in 1927 from Cameroon

Cameroon (; french: Cameroun, ff, Kamerun), officially the Republic of Cameroon (french: République du Cameroun, links=no), is a country in west-central Africa. It is bordered by Nigeria to the west and north; Chad to the northeast; the ...

* ''Panthera pardus adusta'' by Reginald Innes Pocock

Reginald Innes Pocock Fellow of the Royal Society, F.R.S. (4 March 1863 – 9 August 1947) was a British zoologist.

Pocock was born in Clifton, Bristol, the fourth son of Rev. Nicholas Pocock (historian), Nicholas Pocock and Edith Prichard. He ...

in 1927 from the Ethiopian Highlands

* ''Panthera pardus adersi'' by Pocock in 1932 from Unguja Island, Zanzibar

Zanzibar (; ; ) is an insular semi-autonomous province which united with Tanganyika in 1964 to form the United Republic of Tanzania. It is an archipelago in the Indian Ocean, off the coast of the mainland, and consists of many small islan ...

* ''Panthera pardus brockmani'' by Pocock in 1932 from Somaliland

Somaliland,; ar, صوماليلاند ', ' officially the Republic of Somaliland,, ar, جمهورية صوماليلاند, link=no ''Jumhūrīyat Ṣūmālīlānd'' is a ''de facto'' sovereign state in the Horn of Africa, still conside ...

Results of genetic analyses

Genetic analysis is the overall process of studying and researching in fields of science that involve genetics and molecular biology. There are a number of applications that are developed from this research, and these are also considered parts of ...

indicate that all African leopard populations are generally closely related and represent only one subspecies

In biological classification, subspecies is a rank below species, used for populations that live in different areas and vary in size, shape, or other physical characteristics ( morphology), but that can successfully interbreed. Not all specie ...

, namely ''P. p. pardus''. However, results of an analysis of molecular variance and the pairwise fixation index of African leopard museum specimens shows differences in the ND-5 locus spanning five major haplogroups, namely in Central–Southern Africa, Southern Africa, West Africa, coastal West–Central Africa, and Central–East Africa. In some cases, fixation indices showed higher diversity than for the Arabian leopard and ''Panthera pardus tulliana

''Panthera pardus tulliana'' is a leopard subspecies native to the Iranian Plateau and surrounding areas encompassing Turkey, the Caucasus, Azerbaijan, Georgia (country), Georgia, Armenia, Iraq, Iran, Turkmenistan, Afghanistan and possibly Paki ...

'' in Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an are ...

.

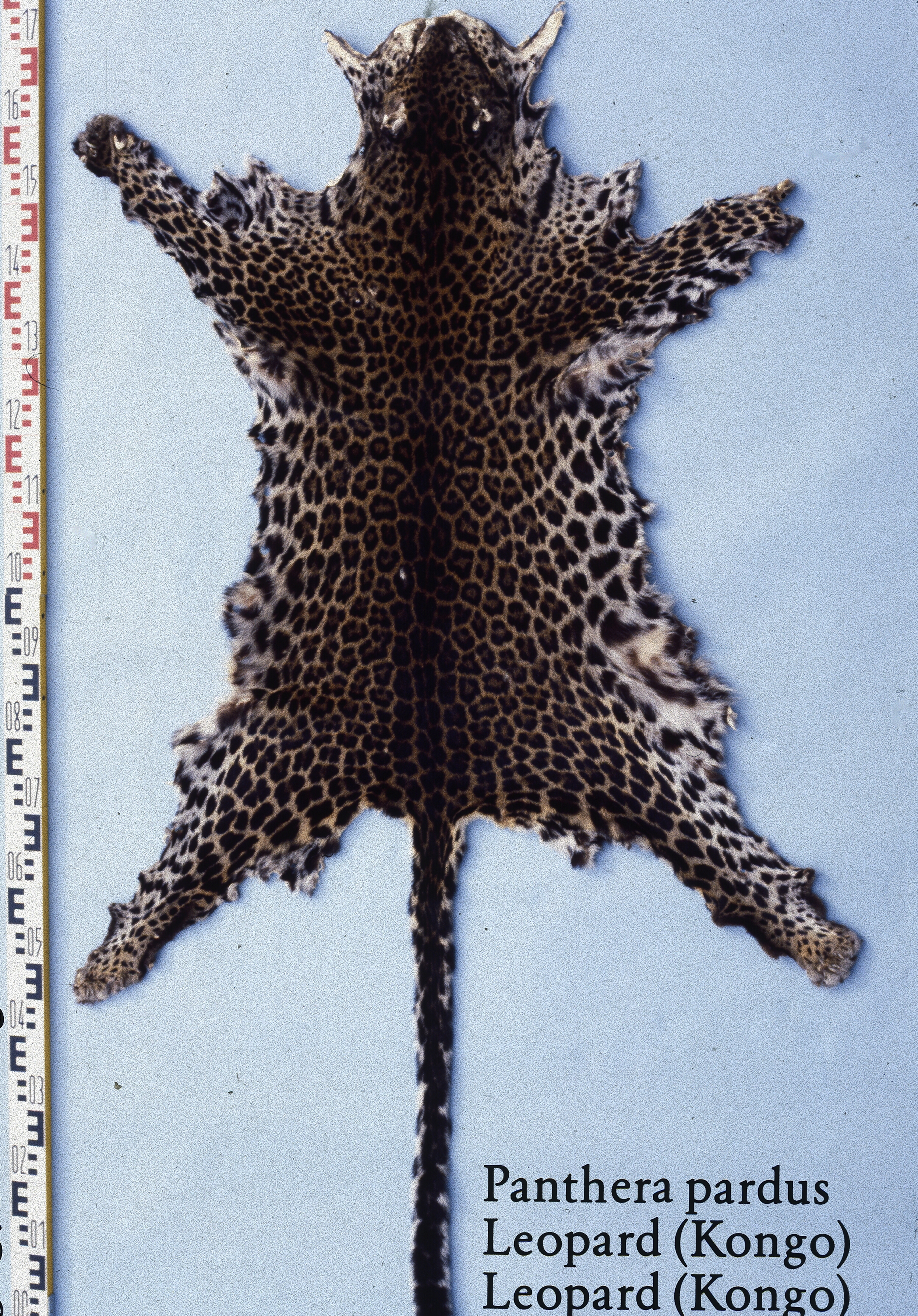

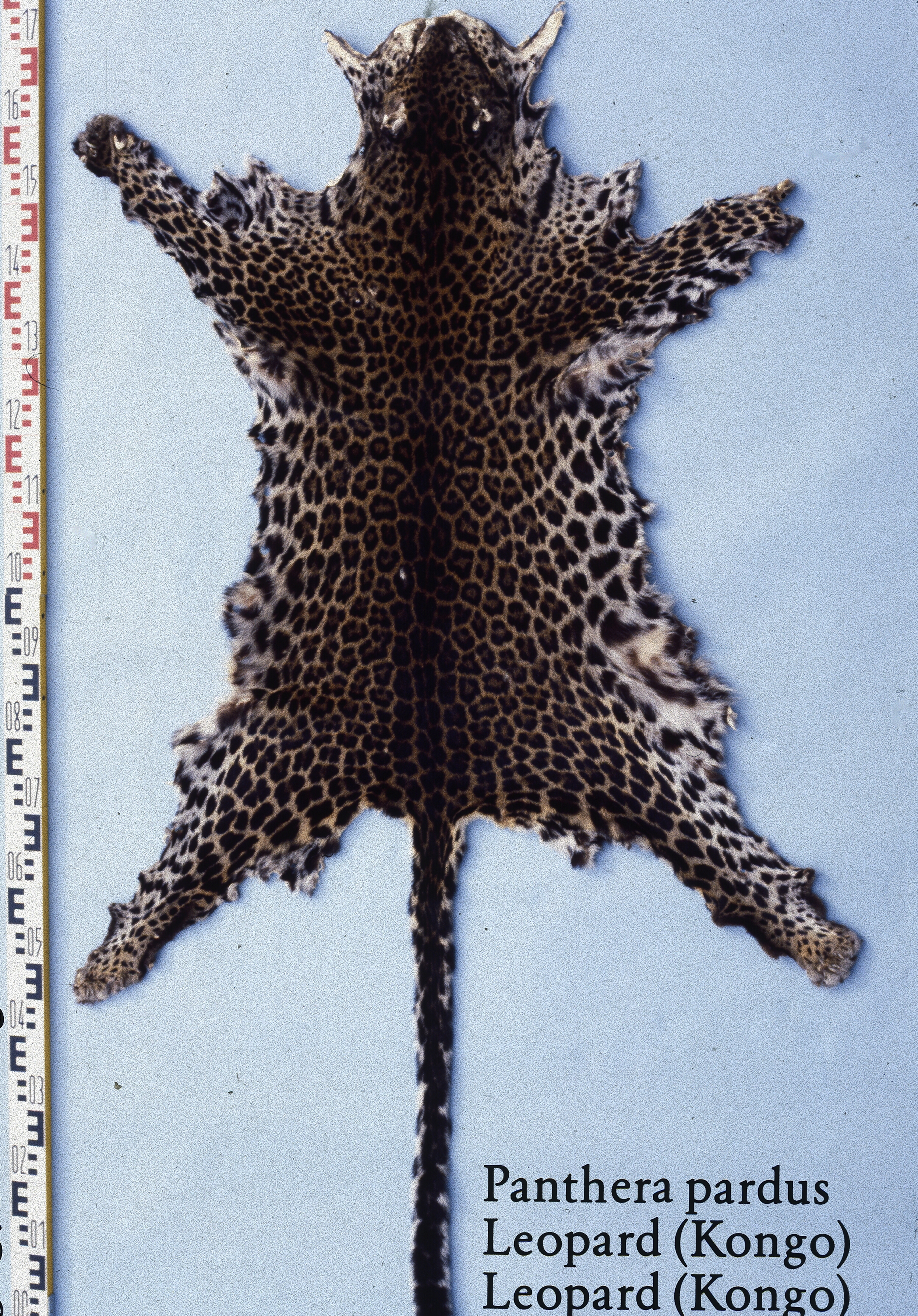

Characteristics

The African leopard exhibits great variation in coat color, depending on location and habitat. Coat colour varies from pale yellow to deep gold or tawny, and sometimes

The African leopard exhibits great variation in coat color, depending on location and habitat. Coat colour varies from pale yellow to deep gold or tawny, and sometimes black

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white ha ...

, and is patterned with black rosettes while the head, lower limbs and belly are spotted with solid black. Male leopards are larger, averaging with being the maximum weight attained by a male. Females weigh about on average.

The African leopard is sexually dimorphic; males are larger and heavier than females. Between 1996 and 2000, 11 adult leopards were radio-collared on Namibia

Namibia (, ), officially the Republic of Namibia, is a country in Southern Africa. Its western border is the Atlantic Ocean. It shares land borders with Zambia and Angola to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south and ea ...

n farmlands. Males weighed only, and females . The heaviest known leopard weighed about , and was recorded in South West Africa.

According to Alfred Edward Pease, black leopards in North Africa were similar in size to lions

The lion (''Panthera leo'') is a large cat of the genus '' Panthera'' native to Africa and India. It has a muscular, broad-chested body; short, rounded head; round ears; and a hairy tuft at the end of its tail. It is sexually dimorphic; ad ...

. An Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

n leopard killed in 1913 was reported to have measured approximately , before being skinned.

Leopards inhabiting the mountains of the Cape Provinces appear smaller and less heavy than leopards further north. Leopards in Somalia and Ethiopia are also said to be smaller.

The skull of a West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali ...

n leopard specimen measured in basal length, and in breadth, and weighed . To compare, that of an Indian leopard measured in basal length, and in breadth, and weighed .

Distribution and habitat

The African leopards inhabited a wide range of habitats within

The African leopards inhabited a wide range of habitats within Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

, from mountainous forests to grasslands and savannah

A savanna or savannah is a mixed woodland-grassland (i.e. grassy woodland) ecosystem characterised by the trees being sufficiently widely spaced so that the canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to reach the ground to ...

s, excluding only extremely sandy desert. It is most at risk in areas of semi-desert, where scarce resources often result in conflict with nomadic farmers and their livestock.

It used to occur in most of sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is, geographically, the area and regions of the continent of Africa that lies south of the Sahara. These include West Africa, East Africa, Central Africa, and Southern Africa. Geopolitically, in addition to the List of sov ...

, occupying both rainforest

Rainforests are characterized by a closed and continuous tree canopy, moisture-dependent vegetation, the presence of epiphytes and lianas and the absence of wildfire. Rainforest can be classified as tropical rainforest or temperate rainfores ...

and arid desert

A desert is a barren area of landscape where little precipitation occurs and, consequently, living conditions are hostile for plant and animal life. The lack of vegetation exposes the unprotected surface of the ground to denudation. About on ...

habitats. It lived in all habitats with annual rainfall above , and can penetrate areas with less than this amount of rainfall along river courses. It ranges up to , has been sighted on high slopes of the Ruwenzori and Virunga volcanoes, and observed when drinking thermal water in the Virunga National Park.

It appears to be successful at adapting to altered natural habitat and settled environments in the absence of intense persecution. It has often been recorded close to major cities. But already in the 1980s, it has become rare throughout much of West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali ...

. Now, it remains patchily distributed within historical limits. During surveys in 2013, it was recorded in Gbarpolu County and Bong County

Bong is a county in the north-central portion of the West African nation of Liberia. One of 15 counties that comprise the first-level of administrative division in the nation, it has twelve districts. Gbarnga serves as the capital. The area of t ...

in the Upper Guinean forests

The Upper Guinean forests is a tropical seasonal forest region of West Africa. The Upper Guinean forests extend from Guinea and Sierra Leone in the west through Liberia, Côte d'Ivoire and Ghana to Togo in the east, and a few hundred kilometers in ...

of Liberia

Liberia (), officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to Guinea–Liberia border, its north, Ivory Coast to Ivory Coast� ...

.

Leopards are rare in North Africa. A relict population

In biogeography and paleontology, a relict is a population or taxon of organisms that was more widespread or more diverse in the past. A relictual population is a population currently inhabiting a restricted area whose range was far wider during a ...

persists in the Atlas Mountains

The Atlas Mountains are a mountain range in the Maghreb in North Africa. It separates the Sahara Desert from the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean; the name "Atlantic" is derived from the mountain range. It stretches around through ...

of Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to A ...

, in forest and mountain steppe in elevations of , where the climate is temperate to cold.

In 2014, a leopard was killed in the Elba Protected Area in southeastern Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

. This was the first sighting of a leopard in the country since the 1950s.

In 2016, a leopard was recorded for the first time in a semi-arid area of Yechilay in northern Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

.

Behavior and ecology

InKruger National Park

Kruger National Park is a South African National Park and one of the largest game reserves in Africa. It covers an area of in the provinces of Limpopo and Mpumalanga in northeastern South Africa, and extends from north to south and from ea ...

, male leopards and female leopards with cubs were more active at night than solitary females. The highest rates of daytime activity were recorded for leopards using thorn thickets during the wet season, when impala also used them. Leopards are generally most active between sunset and sunrise, and kill more prey

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill ...

at this time.

Diet and hunting

The leopard has an exceptional ability to adapt to changes in prey availability, and has a very broad diet. It takes small prey where largeungulate

Ungulates ( ) are members of the diverse clade Ungulata which primarily consists of large mammals with hooves. These include odd-toed ungulates such as horses, rhinoceroses, and tapirs; and even-toed ungulates such as cattle, pigs, giraffes, ...

s are less common. The known prey of leopards ranges from dung beetle

Dung beetles are beetles that feed on feces. Some species of dung beetles can bury dung 250 times their own mass in one night.

Many dung beetles, known as ''rollers'', roll dung into round balls, which are used as a food source or breeding cha ...

s to adult elands, which can reach . In sub-Saharan Africa, at least 92 prey species have been documented in leopard scat, including rodent

Rodents (from Latin , 'to gnaw') are mammals of the order Rodentia (), which are characterized by a single pair of continuously growing incisors in each of the upper and lower jaws. About 40% of all mammal species are rodents. They are n ...

s, bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweig ...

s, small and large antelope

The term antelope is used to refer to many species of even-toed ruminant that are indigenous to various regions in Africa and Eurasia.

Antelope comprise a wastebasket taxon defined as any of numerous Old World grazing and browsing hoofed mamm ...

s, hyrax

Hyraxes (), also called dassies, are small, thickset, herbivorous mammals in the order Hyracoidea. Hyraxes are well-furred, rotund animals with short tails. Typically, they measure between long and weigh between . They are superficially simila ...

es, hare

Hares and jackrabbits are mammals belonging to the genus ''Lepus''. They are herbivores, and live solitarily or in pairs. They nest in slight depressions called forms, and their young are able to fend for themselves shortly after birth. The g ...

s, and arthropod

Arthropods (, (gen. ποδός)) are invertebrate animals with an exoskeleton, a segmented body, and paired jointed appendages. Arthropods form the phylum Arthropoda. They are distinguished by their jointed limbs and cuticle made of chiti ...

s. Leopards generally focus their hunting activity on locally abundant medium-sized ungulates in the range, while opportunistically taking other prey. Average intervals between ungulate kills range from seven to 12–13 days.

Leopards often hide large kills in trees, a behavior for which great strength is required. There have been several observations of leopards hauling carcasses of young giraffe

The giraffe is a large African hoofed mammal belonging to the genus ''Giraffa''. It is the tallest living terrestrial animal and the largest ruminant on Earth. Traditionally, giraffes were thought to be one species, '' Giraffa camelopardal ...

s, estimated to weigh up to , i.e. 2–3 times the weight of the leopard, up to into trees.

In Serengeti National Park

The Serengeti National Park is a large national park in northern Tanzania that stretches over . It is located entirely in eastern Mara Region and north east portion of Simiyu Region and contains over of virgin savanna. The park was established ...

, leopards were radio-collared for the first time in the early 1970s. Their hunting at night was difficult to watch; the best time for observing them was after dawn. Of their 64 daytime hunts, only three were successful. In this woodland area, they preyed mostly on impalas, both adult and young, and caught some Thomson's gazelles in the dry season. Occasionally, they successfully hunted warthog

''Phacochoerus'' is a genus in the family Suidae, commonly known as warthogs (pronounced ''wart-hog''). They are pigs who live in open and semi-open habitats, even in quite arid regions, in sub-Saharan Africa. The two species were formerly con ...

s, dik-diks, reedbucks, duikers, steenbok

The steenbok (''Raphicerus campestris'') is a common small antelope of southern and eastern Africa. It is sometimes known as the steinbuck or steinbok.

Description

Steenbok resemble small oribi, standing 45–60 cm (16"–24") at the s ...

s, blue wildebeest

The blue wildebeest (''Connochaetes taurinus''), also called the common wildebeest, white-bearded gnu or brindled gnu, is a large antelope and one of the two species of wildebeest. It is placed in the genus '' Connochaetes'' and family Bovidae, a ...

and topi

''Damaliscus lunatus jimela'' is a subspecies of topi, and is usually just called a topi. It is a highly social and fast type of antelope found in the savannas, semi-deserts, and floodplains of sub-Saharan Africa.

Names

The word ''tope'' or ''t ...

calves, jackals, Cape hares, guineafowl

Guineafowl (; sometimes called "pet speckled hens" or "original fowl") are birds of the family Numididae in the order Galliformes. They are endemic to Africa and rank among the oldest of the gallinaceous birds. Phylogenetically, they branched ...

and starlings. They were less successful in hunting plains zebras, Coke's hartebeests, giraffe

The giraffe is a large African hoofed mammal belonging to the genus ''Giraffa''. It is the tallest living terrestrial animal and the largest ruminant on Earth. Traditionally, giraffes were thought to be one species, '' Giraffa camelopardal ...

s, mongooses, genets, hyrax

Hyraxes (), also called dassies, are small, thickset, herbivorous mammals in the order Hyracoidea. Hyraxes are well-furred, rotund animals with short tails. Typically, they measure between long and weigh between . They are superficially simila ...

es and small birds. Scavenging from the carcasses of large animals made up a small proportion of their food. In the tropical rainforest

Tropical rainforests are rainforests that occur in areas of tropical rainforest climate in which there is no dry season – all months have an average precipitation of at least 60 mm – and may also be referred to as ''lowland equator ...

s of Central Africa

Central Africa is a subregion of the African continent comprising various countries according to different definitions. Angola, Burundi, the Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Co ...

, their diet consists of duikers and primate

Primates are a diverse order of mammals. They are divided into the strepsirrhines, which include the lemurs, galagos, and lorisids, and the haplorhines, which include the tarsiers and the simians ( monkeys and apes, the latter includin ...

s. Some individual leopards have shown a strong preference for pangolin

Pangolins, sometimes known as scaly anteaters, are mammals of the order Pholidota (, from Ancient Greek ϕολιδωτός – "clad in scales"). The one extant family, the Manidae, has three genera: '' Manis'', ''Phataginus'', and '' Smuts ...

s and porcupine

Porcupines are large rodents with coats of sharp spines, or quills, that protect them against predation. The term covers two families of animals: the Old World porcupines of family Hystricidae, and the New World porcupines of family, Erethiz ...

s.

In North Africa, the leopard preys on Barbary macaques (''Macaca sylvanus'').

Analysis of leopard scat in Taï National Park

Taï National Park () is a national park in Côte d'Ivoire that contains one of the last areas of primary rainforest in West Africa. It was inscribed as a World Heritage Site in 1982 due to the diversity of its flora and fauna. Five mammal specie ...

revealed that primate

Primates are a diverse order of mammals. They are divided into the strepsirrhines, which include the lemurs, galagos, and lorisids, and the haplorhines, which include the tarsiers and the simians ( monkeys and apes, the latter includin ...

s are primary leopard prey during the day.

In Gabon's Lope National Park, the most important prey species was found to be the red river hog (''Potamochoerus porcus''). African buffaloes (''Syncerus caffer'') and cane rats (''Thryonomys swinderianus''), comprised 13% each of the consumed biomass.

In the Central African Republic's Dzanga-Sangha Complex of Protected Areas, a leopard reportedly attacked and pursued a large western lowland gorilla

The western lowland gorilla (''Gorilla gorilla gorilla'') is one of two Critically Endangered subspecies of the western gorilla (''Gorilla gorilla'') that lives in montane, primary and secondary forest and lowland swampland in central Af ...

, but did not catch it. Gorilla parts found in leopard scat indicates that the leopard either scavenged on gorilla remains or killed it. African leopards were observed preying on adult eastern gorilla

The eastern gorilla (''Gorilla beringei'') is a critically endangered species of the genus ''Gorilla'' and the largest living primate. At present, the species is subdivided into two subspecies. There are 3,800 eastern lowland gorillas or Graue ...

s in the Kisoro

Kisoro is a town in the Western Region of Uganda. It is the chief town of Kisoro District and the site of the district headquarters.

Location

Kisoro is approximately , by road, west of Kabale, the largest city in the Kigezi sub-region. This is ...

area near Uganda's borders with Rwanda

Rwanda (; rw, u Rwanda ), officially the Republic of Rwanda, is a landlocked country in the Great Rift Valley of Central Africa, where the African Great Lakes region and Southeast Africa converge. Located a few degrees south of the Equator ...

and the Democratic Republic of the Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (french: République démocratique du Congo (RDC), colloquially "La RDC" ), informally Congo-Kinshasa, DR Congo, the DRC, the DROC, or the Congo, and formerly and also colloquially Zaire, is a country in ...

.

Threats

Throughout Africa, the major threats to leopards are habitat conversion and intense persecution, especially in retribution for real and perceived livestock loss. The Upper Guinean forests in Liberia are considered a biodiversity hotspot, but have already been fragmented into two blocks. Large tracts are affected by commerciallogging

Logging is the process of cutting, processing, and moving trees to a location for transport. It may include skidding, on-site processing, and loading of trees or logs onto trucks or skeleton cars.

Logging is the beginning of a supply cha ...

and mining

Mining is the extraction of valuable minerals or other geological materials from the Earth, usually from an ore body, lode, vein, seam, reef, or placer deposit. The exploitation of these deposits for raw material is based on the econom ...

activities, and are converted for agricultural use including large-scale oil palm

''Elaeis'' () is a genus of palms containing two species, called oil palms. They are used in commercial agriculture in the production of palm oil. The African oil palm '' Elaeis guineensis'' (the species name ''guineensis'' referring to its c ...

plantation

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. Th ...

s in concessions obtained by a foreign company.

The impact of trophy hunting

Trophy hunting is a form of hunting for sport in which parts of the hunted wild animals are kept and displayed as trophies. The animal being targeted, known as the " game", is typically a mature male specimen from a popular species of collectab ...

on populations is unclear, but may have impacts at the demographic and population level, especially when females are shot. In Tanzania

Tanzania (; ), officially the United Republic of Tanzania ( sw, Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania), is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It borders Uganda to the north; Kenya to the northeast; Comoro Islands ...

, only males are allowed to be hunted, but females comprised 28.6% of 77 trophies shot between 1995 and 1998. Removing an excessively high number of males may produce a cascade of deleterious effects on the population. Although male leopards provide no parental care to cubs, the presence of the sire allows females to raise cubs with a reduced risk of infanticide

Infanticide (or infant homicide) is the intentional killing of infants or offspring. Infanticide was a widespread practice throughout human history that was mainly used to dispose of unwanted children, its main purpose is the prevention of resou ...

by other males. There are few reliable observations of infanticide in leopards, but new males entering the population are likely to kill existing cubs.

Analysis of leopard scats and camera trapping surveys in contiguous forest landscapes in the Congo Basin revealed a high dietary niche overlap and an exploitative competition between leopards and bushmeat hunters. With increasing proximity to settlements and concomitant human hunting pressure, leopards exploit smaller prey and occur at considerably reduced population densities. In the presence of intensive bushmeat hunting surrounding human settlements, leopards appear entirely absent.

Transhumant

Transhumance is a type of pastoralism or nomadism, a seasonal movement of livestock between fixed summer and winter pastures. In montane regions (''vertical transhumance''), it implies movement between higher pastures in summer and lower val ...

pastoralists from the border area between Sudan and the Central African Republic take their livestock to the Chinko area. They are accompanied by armed merchants who engage in poaching large herbivores, sale of bushmeat and trading leopard skins in Am Dafok. Surveys in the area revealed that the leopard population decreased from 97 individuals in 2012 to 50 individuals in 2017. Rangers confiscated large amounts of poison

Poison is a chemical substance that has a detrimental effect to life. The term is used in a wide range of scientific fields and industries, where it is often specifically defined. It may also be applied colloquially or figuratively, with a broa ...

in the camps of livestock herders, who admitted that they use it for poisoning predators.

Conservation

The leopard is listed in CITES Appendix I. Hunting is banned in Zambia and Botswana, and was suspended in South Africa for 2016. Leopard populations are present in several protected areas, including: *Taï National Park *Etosha National Park *Virunga National Park *Kruger National ParkSee also

* Leopard subspecies * Chinese leopard *Zanzibar leopard

The Zanzibar leopard is an African leopard (''Panthera pardus pardus'') population on Unguja Island in the Zanzibar archipelago, Tanzania, that is considered extirpated due to persecution by local hunters and loss of habitat. It was the island's ...

References

External links

Species portrait African leopard; IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group

Leopards .:. wild-cat.org — Information about research and conservation of leopards

The Cape Leopard Trust, South Africa

Safarinow.com: ''African Leopard » Panthera pardus » 'Luiperd

Image of a leopard from the Central African forests of Gabon

Predation on a child

at Queen Elizabeth National Park, Uganda {{Taxonbar, from=Q39153 African leopard African leopard Taxa named by Carl Linnaeus Mammals of Sub-Saharan Africa