Adephaga on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Adephaga (from

The Adephaga (from

Adephaga

Tree of Life {{DEFAULTSORT:Adephaga Insect suborders

The Adephaga (from

The Adephaga (from Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

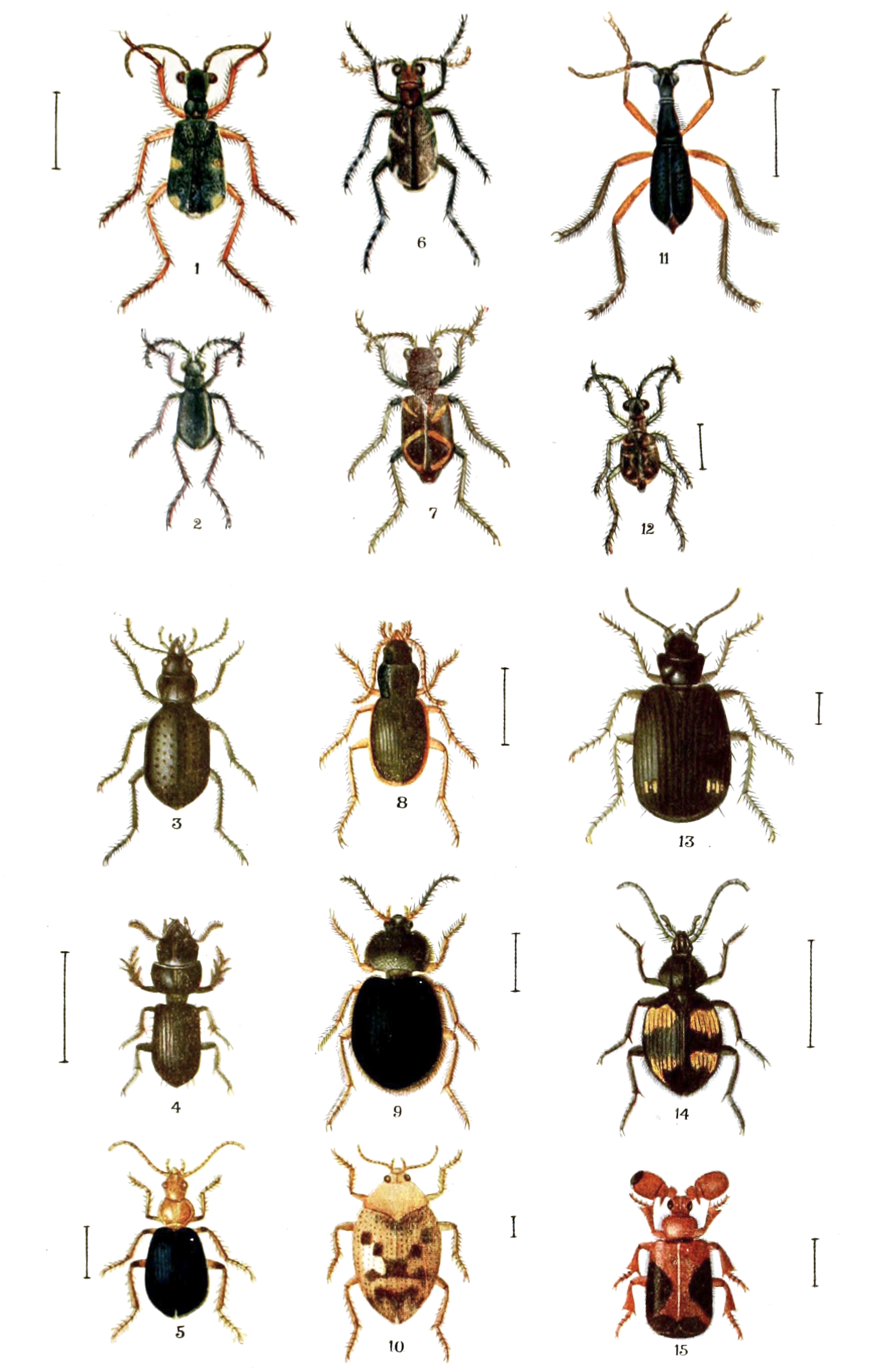

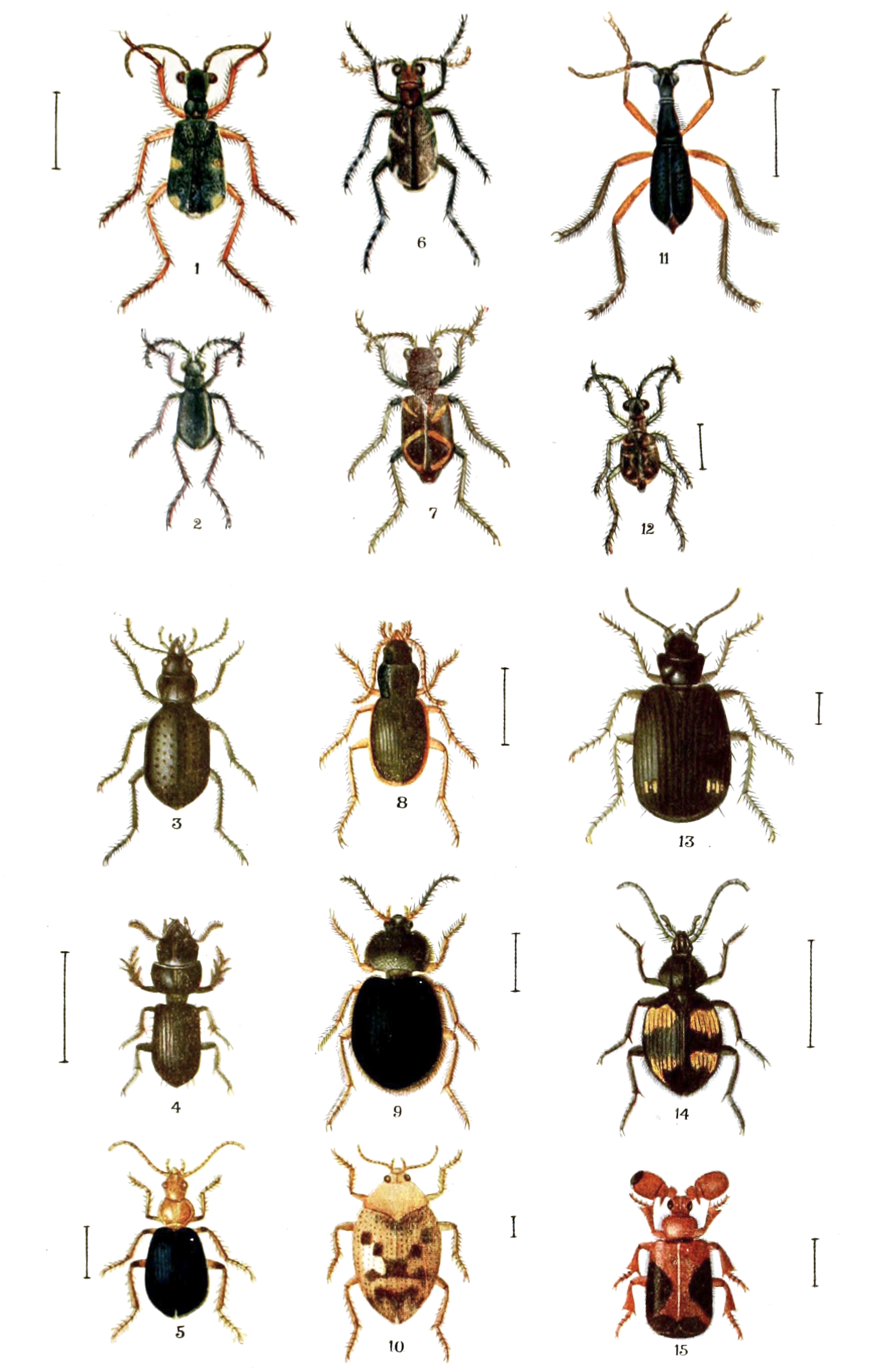

ἀδηφάγος, ''adephagos'', "gluttonous") are a suborder of beetles

Beetles are insects that form the Taxonomic rank, order Coleoptera (), in the superorder Endopterygota. Their front pair of wings are hardened into wing-cases, Elytron, elytra, distinguishing them from most other insects. The Coleoptera, wit ...

, and with more than 40,000 recorded species in 10 families, the second-largest of the four beetle suborders. Members of this suborder are collectively known as adephagans. The largest family is Carabidae

Ground beetles are a large, cosmopolitan family of beetles, the Carabidae, with more than 40,000 species worldwide, around 2,000 of which are found in North America and 2,700 in Europe. As of 2015, it is one of the 10 most species-rich animal fam ...

(ground beetles) which comprises most of the suborder with over 40,000 species. Adephaga also includes a variety of aquatic beetles, such as predaceous diving beetle

The Dytiscidae – based on the Greek ''dytikos'' (δυτικός), "able to dive" – are the predaceous diving beetles, a family of water beetles. They occur in virtually any freshwater habitat around the world, but a few species live a ...

s and whirligig beetles.

Anatomy

Adephagans have simple antennae with no pectination or clubs. The galeae of themaxillae

The maxilla (plural: ''maxillae'' ) in vertebrates is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. The tw ...

usually consist of two segments. Adult adephagans have visible notopleural

The notopleuron (plural notopleura) is a region on an insect thorax. Notopleura are useful in characterizing species, particularly, though not uniquely, in the Order Diptera (the "true flies"). The notopleuron is a thoracic pleurite (a sclerite ...

sutures. The first visible abdominal sternum is completely separated by the hind coxae, which is one of the most easily recognizable traits of adephagans. Five segments are on each foot.

Wings

Thetransverse fold

Transverse may refer to:

* Transverse engine, an engine in which the crankshaft is oriented side-to-side relative to the wheels of the vehicle

* Transverse flute, a flute that is held horizontally

* Transverse force (or ''Euler force''), the tang ...

of the hind wing is near the wing tip. The median nervure

In statistics and probability theory, the median is the value separating the higher half from the lower half of a data sample, a population, or a probability distribution. For a data set, it may be thought of as "the middle" value. The basic ...

ends at this fold, where it is joined by a cross nervure

A cross is a geometrical figure consisting of two intersecting lines or bars, usually perpendicular to each other. The lines usually run vertically and horizontally. A cross of oblique lines, in the shape of the Latin letter X, is termed a s ...

.

Internal organs

Adephagans have four Malpighian tubules. Unlike the genetical structures of other beetles, yolk chambers alternate with egg chambers in the ovarian tubes of adephagans. The coiled, tubular testes consist of a single follicle, and the ovaries arepolytrophic

The Trophic State Index (TSI) is a classification system designed to rate water bodies based on the amount of biological productivity they sustain. Although the term "trophic index" is commonly applied to lakes, any surface water body may be inde ...

.

Chemical glands

All families of adephagan have paired pygidialgland

In animals, a gland is a group of cells in an animal's body that synthesizes substances (such as hormones) for release into the bloodstream ( endocrine gland) or into cavities inside the body or its outer surface ( exocrine gland).

Structure

...

s located posterodorsally in the abdomen

The abdomen (colloquially called the belly, tummy, midriff, tucky or stomach) is the part of the body between the thorax (chest) and pelvis, in humans and in other vertebrates. The abdomen is the front part of the abdominal segment of the tors ...

, which are used for secreting chemicals. The glands consist of complex invaginations of the cuticle lined with epidermal cells contiguous with the integument. The glands have no connection with the rectum and open on the eighth abdominal tergum

A ''tergum'' (Latin for "the back"; plural ''terga'', associated adjective tergal) is the dorsal ('upper') portion of an arthropod segment other than the head. The anterior edge is called the 'base' and posterior edge is called the 'apex' or 'm ...

.

Secretions pass from the secretory lobe 440px

Secretion is the movement of material from one point to another, such as a secreted chemical substance from a cell or gland. In contrast, excretion is the removal of certain substances or waste products from a cell or organism. The classi ...

s, which are aggregations of secretory cells, through a tube to a reservoir lined with muscles. This reservoir then narrows to a tube leading to an opening valve. The secretory lobes differ structurally from one taxon to another; it may be elongated or oval, branched basally or apically, or unbranched.

Delivery of glandular compounds

Secretion can occur in multiple manners: *Oozing: if the gland is not muscle-lined, the discharge is limited in amount. *Spraying: if the gland is muscle-lined, which is typically the case of carabids, the substances are ejected more or less forcefully. *Crepitation: boiling noxious chemical spray ejected with a popping sound. Crepitation is only associated with the Brachininae carabids and several related species. See bombardier beetle for a detailed description. The secretions differ in the chemical constituents, according to the taxa. Gyrinids, for instance, secrete norsesquiterpenes such as gyrinidal, gyrinidione, or gyrinidone. Dytiscids discharge aromaticaldehyde

In organic chemistry, an aldehyde () is an organic compound containing a functional group with the structure . The functional group itself (without the "R" side chain) can be referred to as an aldehyde but can also be classified as a formyl group ...

s, ester

In chemistry, an ester is a compound derived from an oxoacid (organic or inorganic) in which at least one hydroxyl group () is replaced by an alkoxy group (), as in the substitution reaction of a carboxylic acid and an alcohol. Glycerides ...

s, and acids, especially benzoic acid. Carabids typically produce carboxylic acid

In organic chemistry, a carboxylic acid is an organic acid that contains a carboxyl group () attached to an R-group. The general formula of a carboxylic acid is or , with R referring to the alkyl, alkenyl, aryl, or other group. Carboxyl ...

s, particularly formic acid

Formic acid (), systematically named methanoic acid, is the simplest carboxylic acid, and has the chemical formula HCOOH and structure . It is an important intermediate in chemical synthesis and occurs naturally, most notably in some ants. Est ...

, methacrylic acid, and tiglic acid, but also aliphatic ketones, saturated ester

Saturation, saturated, unsaturation or unsaturated may refer to:

Chemistry

* Saturation, a property of organic compounds referring to carbon-carbon bonds

**Saturated and unsaturated compounds

** Degree of unsaturation

**Saturated fat or fatty aci ...

s, phenol

Phenol (also called carbolic acid) is an aromatic organic compound with the molecular formula . It is a white crystalline solid that is volatile. The molecule consists of a phenyl group () bonded to a hydroxy group (). Mildly acidic, it ...

s, aromatic aldehydes, and quinones.

Accessory glands or modified structures are present in some taxa: the Dytiscidae

The Dytiscidae – based on the Greek ''dytikos'' (δυτικός), "able to dive" – are the predaceous diving beetles, a family of water beetles. They occur in virtually any freshwater habitat around the world, but a few species live ...

and Hygrobiidae also possess paired prothoracic glands secreting steroid

A steroid is a biologically active organic compound with four rings arranged in a specific molecular configuration. Steroids have two principal biological functions: as important components of cell membranes that alter membrane fluidity; and ...

s; and the Gyrinidae are unique in the extended shape of the external opening of the pygidial gland.

The function of many compounds remain unknown, yet several hypotheses have been advanced:

*As toxins or deterrent against predator

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill ...

s; some compounds indirectly play this role by easing the penetration of the deterrent into the predator's integument.

*Antimicrobial

An antimicrobial is an agent that kills microorganisms or stops their growth. Antimicrobial medicines can be grouped according to the microorganisms they act primarily against. For example, antibiotics are used against bacteria, and antifungals ...

and antifungal agents (especially in Hydradephaga)

*A means to increase wettability of the integument (especially in Hydradephaga)

*Alarm pheromones (especially in Gyrinidae)

*Propellant on water surfaces (especially in Gyrinidae)

*Conditioning plant tissues associated with oviposition

Distribution and habitat

Habitat

In ecology, the term habitat summarises the array of resources, physical and biotic factors that are present in an area, such as to support the survival and reproduction of a particular species. A species habitat can be seen as the physical ...

s range from cave

A cave or cavern is a natural void in the ground, specifically a space large enough for a human to enter. Caves often form by the weathering of rock and often extend deep underground. The word ''cave'' can refer to smaller openings such as sea ...

s to rainforest

Rainforests are characterized by a closed and continuous tree canopy, moisture-dependent vegetation, the presence of epiphytes and lianas and the absence of wildfire. Rainforest can be classified as tropical rainforest or temperate rainfo ...

canopy and alpine habitats. The body forms of some are structurally modified for adaptation to habitats: members of the family Gyrinidae live at the air-water interface, Rhysodinae live in heartwood, and Paussinae carabids inhabit ant nests.

Feeding

Most species arepredator

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill ...

s. Other less-typical forms of feeding include: eating algae (family Haliplidae), seed-feeding ( harpaline carabids), fungus-feeding (rhysodine carabids), and snail-feeding ( licinine and cychrine carabids). Some species are ectoparasitoid

In evolutionary ecology, a parasitoid is an organism that lives in close association with its host at the host's expense, eventually resulting in the death of the host. Parasitoidism is one of six major evolutionary strategies within parasi ...

s of insects ( brachinine and lebiine carabids) or of millipedes ( peleciine carabids).

Reproduction and larval stage

Some species are ovoviviparous, such as pseudomorphine carabids. Thelarva

A larva (; plural larvae ) is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into adults. Animals with indirect development such as insects, amphibians, or cnidarians typically have a larval phase of their life cycle.

Th ...

e are active, with well-chitin

Chitin ( C8 H13 O5 N)n ( ) is a long-chain polymer of ''N''-acetylglucosamine, an amide derivative of glucose. Chitin is probably the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature (behind only cellulose); an estimated 1 billion tons of chit ...

ized cuticle, often with elongated cerci and five-segmented legs, the foot-segment carrying two claws. Larvae have a fused labrum and no mandibular molae.

Phylogeny

Adephagans diverged from their sister group in the Late Permian, the most recent common ancestor of living adephagans probably existing in the earlyTriassic

The Triassic ( ) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.6 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.36 Mya. The Triassic is the first and shortest period ...

, around 240 million years ago. Both aquatic and terrestrial representatives of the suborder appear in fossil records of the late Triassic. The Jurassic fauna consisted of trachypachid

The Trachypachidae (sometimes known as false ground beetles) are a family of beetles that generally resemble small ground beetles, but that are distinguished by the large coxae of their rearmost legs. There are only six known extant species in ...

s, carabids, gyrinids, and haliplid

The Haliplidae are a family of water beetles that swim using an alternating motion of the legs. They are therefore clumsy in water (compared e.g. with the Dytiscidae or Hydrophilidae), and prefer to get around by crawling. The family consists o ...

-like forms. The familial and tribal diversification of the group spans the Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era ( ), also called the Age of Reptiles, the Age of Conifers, and colloquially as the Age of the Dinosaurs is the second-to-last era of Earth's geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Creta ...

, with a few tribes radiating explosively during the Tertiary

Tertiary ( ) is a widely used but obsolete term for the geologic period from 66 million to 2.6 million years ago.

The period began with the demise of the non- avian dinosaurs in the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, at the start ...

.

The adephagans were formerly grouped into the Geadephaga with the two terrestrial families Carabidae and Trachypachidae and the Hydradephaga, for the aquatic families. However this is no longer used as the Hydradephaga are not a monophyletic group. Modern analysis has supported the clade Dytiscoidea instead, which includes many aquatic adephagans, notably excluding Gyrinidae. Rhysodidae

Rhysodinae is a subfamily (sometimes called wrinkled bark beetles) in the family Carabidae. There are 19 genera and at least 380 described species in Rhysodinae. The group of genera making up Rhysodinae had been treated as the family Rhysodidae i ...

is suggested to represent a subgroup of Carabidae rather than a distinct family, with Cicindelidae often being treated as a distinct family from Carabidae.

Cladogram

A cladogram (from Greek ''clados'' "branch" and ''gramma'' "character") is a diagram used in cladistics to show relations among organisms. A cladogram is not, however, an evolutionary tree because it does not show how ancestors are related to ...

of the relationships of living adephagan families after Vasilikopoulos et al. 2021 and Baca et al. 2021:

See also

* List of subgroups of the order ColeopteraReferences

* *Adephaga

Tree of Life {{DEFAULTSORT:Adephaga Insect suborders