Adams–Onís Treaty on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Adams–Onís Treaty () of 1819, also known as the Transcontinental Treaty, the Florida Purchase Treaty, or the Florida Treaty,Weeks, p.168. was a

Spain had long rejected repeated American efforts to purchase Florida. But by 1818, Spain was facing a troubling colonial situation in which the cession of Florida made sense. Spain had been exhausted by the

Spain had long rejected repeated American efforts to purchase Florida. But by 1818, Spain was facing a troubling colonial situation in which the cession of Florida made sense. Spain had been exhausted by the

In 1521, the Spanish Empire created the ''Virreinato de Nueva España'' (Viceroyalty of New Spain) to govern its conquests in the Caribbean, North America, and later the Pacific Ocean. In 1682, La Salle claimed Louisiana for France. For the Spanish Empire, this was an intrusion into the northeastern frontier of New Spain. In 1691, Spain created the Province of Tejas in an attempt to inhibit French settlement west of the Mississippi River. Fearing the loss of his American territories in the Seven Years' War, King Louis XV of France ceded Louisiana to King Charles III of Spain with the secret Treaty of Fontainebleau in 1762. The Treaty of Paris of 1763 split Louisiana with the portion east of the Mississippi River (except for

In 1521, the Spanish Empire created the ''Virreinato de Nueva España'' (Viceroyalty of New Spain) to govern its conquests in the Caribbean, North America, and later the Pacific Ocean. In 1682, La Salle claimed Louisiana for France. For the Spanish Empire, this was an intrusion into the northeastern frontier of New Spain. In 1691, Spain created the Province of Tejas in an attempt to inhibit French settlement west of the Mississippi River. Fearing the loss of his American territories in the Seven Years' War, King Louis XV of France ceded Louisiana to King Charles III of Spain with the secret Treaty of Fontainebleau in 1762. The Treaty of Paris of 1763 split Louisiana with the portion east of the Mississippi River (except for

The British government claimed the region west of the Continental Divide between the undefined borders of Alta California and

The British government claimed the region west of the Continental Divide between the undefined borders of Alta California and

/ref> The United States claimed essentially the same region on the basis of (1) Robert Gray's Columbia River expedition, the voyage of Robert Gray up the Columbia River in 1792, (2) the United States

On 16 July 1741, the crew of the

On 16 July 1741, the crew of the

The Spanish Empire claimed all lands west of the Continental Divide throughout the Americas.The claim of Spain to all lands west of the Continental Divide in the Americas dated to the papal bull ''

The Spanish Empire claimed all lands west of the Continental Divide throughout the Americas.The claim of Spain to all lands west of the Continental Divide in the Americas dated to the papal bull ''

The treaty, consisting of 16 articles was signed in Adams' State Department office at

The treaty, consisting of 16 articles was signed in Adams' State Department office at

The treaty was ratified by Spain in 1820, and by the United States in 1821 (during the time that Spain and Mexico were engaged in the prolonged

The treaty was ratified by Spain in 1820, and by the United States in 1821 (during the time that Spain and Mexico were engaged in the prolonged

online

* . ;Sources

Avalon Project – Treaty Text

Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture – Adams–Onís Treaty

{{DEFAULTSORT:Adams-Onis Treaty 1819 treaties Boundary treaties New Spain Missouri Territory Spanish Florida Spanish Texas Treaties of the Spanish Empire Treaties of the United States Mexico–United States border 1819 in New Spain 1819 in the United States 1819 in Alta California 16th United States Congress History of United States expansionism Pre-statehood history of Florida Spain–United States relations Red River of the South February 1819 events Purchased territories

treaty

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal pe ...

between the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

and Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

in 1819 that ceded Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

to the U.S. and defined the boundary between the U.S. and New Spain. It settled a standing border dispute between the two countries and was considered a triumph of American diplomacy. It came in the midst of increasing tensions related to Spain's territorial boundaries in North America against the United States and the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

in the aftermath of the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

; it also came during the Latin American wars of independence

The Spanish American wars of independence (25 September 1808 – 29 September 1833; es, Guerras de independencia hispanoamericanas) were numerous wars in Spanish America with the aim of political independence from Spanish rule during the early ...

.

Florida had become a burden to Spain, which could not afford to send settlers or garrisons, so the Spanish government decided to cede the territory to the United States in exchange for settling the boundary dispute along the Sabine River in Spanish Texas

Spanish Texas was one of the interior provinces of the colonial Viceroyalty of New Spain from 1690 until 1821. The term "interior provinces" first appeared in 1712, as an expression meaning "far away" provinces. It was only in 1776 that a lega ...

. The treaty established the boundary of U.S. territory and claims through the Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico ...

and west to the Pacific Ocean, in exchange for the U.S. paying residents' claims against the Spanish government up to a total of $5 million and relinquishing the U.S. claims on parts of Spanish Texas west of the Sabine River and other Spanish areas, under the terms of the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

.

The treaty remained in full effect for only 183 days: from February 22, 1821, to August 24, 1821, when Spanish military officials signed the Treaty of Córdoba

The Treaty of Córdoba established Mexican independence from Spain at the conclusion of the Mexican War of Independence. It was signed on August 24, 1821 in Córdoba, Veracruz, Mexico. The signatories were the head of the Army of the Three Guara ...

acknowledging the independence of Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

; Spain repudiated that treaty, but Mexico effectively took control of Spain's former colony. The Treaty of Limits between Mexico and the United States, signed in 1828 and effective in 1832, recognized the border defined by the Adams–Onís Treaty as the boundary between the two nations.

History

The Adams–Onís Treaty was negotiated byJohn Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States ...

, the Secretary of State under U.S. President James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe was ...

, and the Spanish "minister plenipotentiary" (diplomatic envoy) Luis de Onís y González-Vara, during the reign of King Ferdinand VII.

Florida

Spain had long rejected repeated American efforts to purchase Florida. But by 1818, Spain was facing a troubling colonial situation in which the cession of Florida made sense. Spain had been exhausted by the

Spain had long rejected repeated American efforts to purchase Florida. But by 1818, Spain was facing a troubling colonial situation in which the cession of Florida made sense. Spain had been exhausted by the Peninsular War

The Peninsular War (1807–1814) was the military conflict fought in the Iberian Peninsula by Spain, Portugal, and the United Kingdom against the invading and occupying forces of the First French Empire during the Napoleonic Wars. In Spain ...

(1807–1814) against Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

in Europe and needed to rebuild its credibility and presence in its colonies. Revolutionaries in Central America and South America had been waging wars of independence since 1810. Spain was unwilling to invest further in Florida, encroached on by American settlers, and it worried about the border between New Spain (a large area including today's Mexico, Central America, and much of the current U.S. western states) and the United States. With minor military presence in Florida, Spain was not able to restrain the Seminole

The Seminole are a Native American people who developed in Florida in the 18th century. Today, they live in Oklahoma and Florida, and comprise three federally recognized tribes: the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, the Seminole Tribe of Florida, ...

warriors who routinely crossed the border and raided American villages and farms, as well as protected southern slave refugees from slave owners and traders of the southern United States.Weeks

The United States from 1810 to 1813 annexed and then invaded most of West Florida

West Florida ( es, Florida Occidental) was a region on the northern coast of the Gulf of Mexico that underwent several boundary and sovereignty changes during its history. As its name suggests, it was formed out of the western part of former S ...

(already independent as the Republic of West Florida west of the Pearl River

The Pearl River, also known by its Chinese name Zhujiang or Zhu Jiang in Mandarin pinyin or Chu Kiang and formerly often known as the , is an extensive river system in southern China. The name "Pearl River" is also often used as a catch-a ...

) up to the Perdido River

Perdido River, historically Rio Perdido (1763), is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed April 15, 2011 river in the U.S. states of Alabama and Florida; the Perdido, a desig ...

(modern border river between the states of Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County

, LargestMetro = Greater Birmingham

, area_total_km2 = 135,765 ...

and Florida), claiming that the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

covered West Florida also.Marshall (1914), p. 11. General James Wilkinson invaded and occupied Mobile

Mobile may refer to:

Places

* Mobile, Alabama, a U.S. port city

* Mobile County, Alabama

* Mobile, Arizona, a small town near Phoenix, U.S.

* Mobile, Newfoundland and Labrador

Arts, entertainment, and media Music Groups and labels

* Mobile ( ...

during the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States, United States of America and its Indigenous peoples of the Americas, indigenous allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom ...

and the Spanish never returned to West Florida west of the Perdido River.

The State of Muskogee

The State of Muskogee was a proclaimed sovereign nation located in Florida, founded in 1799 and led by William Augustus Bowles, a Loyalist veteran of the American Revolutionary War who lived among the Muscogee, and envisioned uniting the Am ...

(1799-1803) demonstrated Spain's inability to control the interior of East Florida, at least ''de facto

''De facto'' ( ; , "in fact") describes practices that exist in reality, whether or not they are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms. It is commonly used to refer to what happens in practice, in contrast with ''de jure'' ("by la ...

''; the Spanish presence had been reduced to the capital ( San Agustín) and other coastal cities, while the interior belonged to the Seminole nation.

While fighting escaped African-American slaves, outlaws, and Native Americans in U.S.-controlled Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

during the First Seminole War

The Seminole Wars (also known as the Florida Wars) were three related military conflicts in Florida between the United States and the Seminole, citizens of a Native American nation which formed in the region during the early 1700s. Hostilities ...

, American General Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

had pursued them into Spanish Florida. He built Fort Scott, at the southern border of Georgia (i.e., the U.S.), and used it to destroy the Negro Fort in northwest Florida, whose existence was perceived as an intolerably disruptive risk by Georgia plantation owners.

To stop the Seminole based in East Florida

East Florida ( es, Florida Oriental) was a colony of Great Britain from 1763 to 1783 and a province of Spanish Florida from 1783 to 1821. Great Britain gained control of the long-established Spanish colony of ''La Florida'' in 1763 as part of ...

from raiding Georgia settlements and offering havens for runaway slaves, the U.S. Army led increasingly frequent incursions into Spanish territory. This included the 1817–1818 campaign by Andrew Jackson that became known as the First Seminole War, after which the U.S. effectively seized control of Florida; albeit for purposes of lawful government and administration in Georgia and not for the outright annexation of territory for the U.S. Adams said the U.S. had to take control because Florida (along the border of Georgia and Alabama Territory) had become "a derelict open to the occupancy of every enemy, civilized or savage, of the United States, and serving no other earthly purpose than as a post of annoyance to them". Spain asked for British intervention, but London declined to assist Spain in the negotiations. Some of President Monroe's cabinet demanded Jackson's immediate dismissal for invading Florida, but Adams realized that his success had given the U.S. a favorable diplomatic position. Adams was able to negotiate very favorable terms.

Louisiana

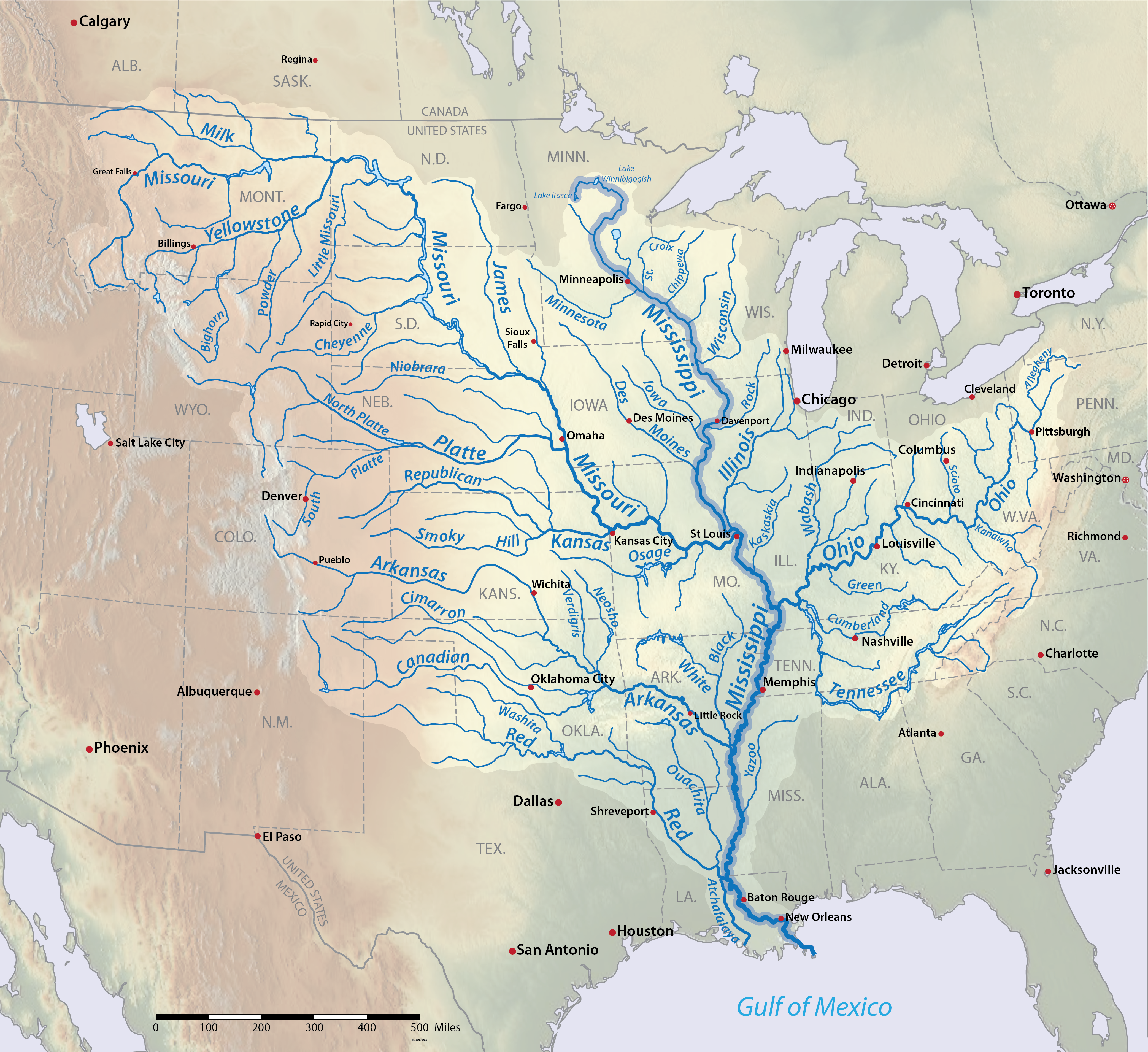

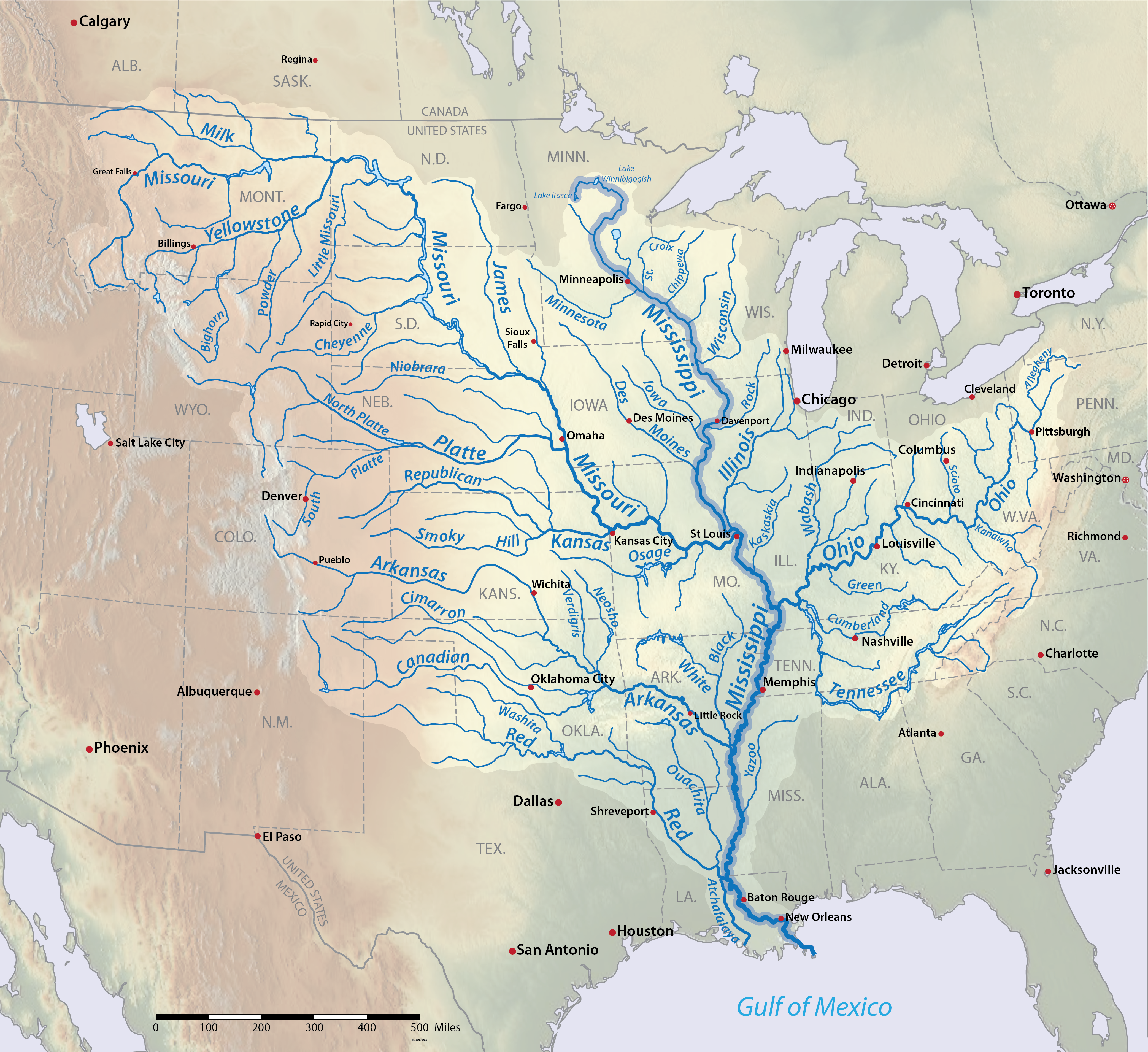

In 1521, the Spanish Empire created the ''Virreinato de Nueva España'' (Viceroyalty of New Spain) to govern its conquests in the Caribbean, North America, and later the Pacific Ocean. In 1682, La Salle claimed Louisiana for France. For the Spanish Empire, this was an intrusion into the northeastern frontier of New Spain. In 1691, Spain created the Province of Tejas in an attempt to inhibit French settlement west of the Mississippi River. Fearing the loss of his American territories in the Seven Years' War, King Louis XV of France ceded Louisiana to King Charles III of Spain with the secret Treaty of Fontainebleau in 1762. The Treaty of Paris of 1763 split Louisiana with the portion east of the Mississippi River (except for

In 1521, the Spanish Empire created the ''Virreinato de Nueva España'' (Viceroyalty of New Spain) to govern its conquests in the Caribbean, North America, and later the Pacific Ocean. In 1682, La Salle claimed Louisiana for France. For the Spanish Empire, this was an intrusion into the northeastern frontier of New Spain. In 1691, Spain created the Province of Tejas in an attempt to inhibit French settlement west of the Mississippi River. Fearing the loss of his American territories in the Seven Years' War, King Louis XV of France ceded Louisiana to King Charles III of Spain with the secret Treaty of Fontainebleau in 1762. The Treaty of Paris of 1763 split Louisiana with the portion east of the Mississippi River (except for Île d'Orléans

Île d'Orléans (; en, Island of Orleans) is an island located in the Saint Lawrence River about east of downtown Quebec City, Quebec, Canada. It was one of the first parts of the province to be colonized by the French, and a large percentage ...

) becoming a part of British North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland, then further south at Roanoke and Jamestow ...

and the portion west of the river becoming the District of Louisiana within New Spain. This eliminated the French threat, and the Spanish provinces of Luisiana, Tejas, and Santa Fe de Nuevo México coexisted with only loosely defined borders. In 1800, French First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte forced King Charles IV of Spain

, house = Bourbon-Anjou

, father = Charles III of Spain

, mother = Maria Amalia of Saxony

, birth_date =11 November 1748

, birth_place =Palace of Portici, Portici, Naples

, death_date =

, death_place ...

to cede Louisiana to France with the secret Third Treaty of San Ildefonso

The Third Treaty of San Ildefonso was a secret agreement signed on 1 October 1800 between the Spanish Empire and the French Republic by which Spain agreed in principle to exchange its North American colony of Louisiana for territories in Tuscany ...

. Spain continued to administer Louisiana until 1802 when Spain publicly transferred the district to France. The following year, Napoleon sold the territory to the United States to raise money for his military campaigns.Marshall (1914), p. 7.

The United States and the Spanish Empire disagreed over the territorial boundaries of the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

of 1803. The United States maintained the claim of France that Louisiana included the Mississippi River and "all lands whose waters flow to it". To the west of , the United States assumed the French claim to all land east and north of either the Sabine RiverMarshall (1914), p. 10. or the Rio Grande.Marshall (1914), p. 13. "The idea that the Louisiana Purchase extended to the Rio Grande became a certainty with Jefferson early in 1804."At the time of the treaty negotiations, the exploration of the western Mississippi River Basin had only begun. A modern definition of the border initially claimed by the United States begins at the mouth of Sabine Pass

Sabine Pass is the natural outlet of Sabine Lake into the Gulf of Mexico. It borders Jefferson County, Texas, and Cameron Parish, Louisiana.

History Civil War

Two major battles occurred here during the American Civil War, known as the First and ...

on the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico ( es, Golfo de México) is an ocean basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, largely surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United ...

(), thence up the Sabine River to its source (), thence due north (a distance of about along meridian 96°12'58"W) to the southern extent of the Red River drainage basin (), thence westward along the southern extent of the Red River drainage basin to the tripoint

A tripoint, trijunction, triple point, or tri-border area is a geographical point at which the boundaries of three countries or subnational entities meet. There are 175 international tripoints as of 2020. Nearly half are situated in rivers, l ...

of the Red River, Arkansas River

The Arkansas River is a major tributary of the Mississippi River. It generally flows to the east and southeast as it traverses the U.S. states of Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. The river's source basin lies in the western United Stat ...

, and Brazos River drainage basin

A drainage basin is an area of land where all flowing surface water converges to a single point, such as a river mouth, or flows into another body of water, such as a lake or ocean. A basin is separated from adjacent basins by a perimeter, ...

s (), thence northwestward along the southern extent of the Arkansas River

The Arkansas River is a major tributary of the Mississippi River. It generally flows to the east and southeast as it traverses the U.S. states of Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. The river's source basin lies in the western United Stat ...

drainage basin to the tripoint of the Mississippi River, Colorado River

The Colorado River ( es, Río Colorado) is one of the principal rivers (along with the Rio Grande) in the Southwestern United States and northern Mexico. The river drains an expansive, arid watershed that encompasses parts of seven U.S. s ...

, and San Luis drainage basins (), thence northward along the Continental Divide of the Americas

The Continental Divide of the Americas (also known as the Great Divide, the Western Divide or simply the Continental Divide; ) is the principal, and largely mountainous, hydrological divide of the Americas. The Continental Divide extends from t ...

to the tripoint of the Mississippi River, Colorado River, and Columbia River drainage basins (on Three Waters Mountain) (). At this tripoint, the United States claim to the Oregon Country began (see #Oregon Country.) Spain maintained that all land west of the Calcasieu River

The Calcasieu River ( ; french: Rivière Calcasieu) is a river on the Gulf Coast in southwestern Louisiana. Approximately long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed June 20, ...

and south of the Arkansas River

The Arkansas River is a major tributary of the Mississippi River. It generally flows to the east and southeast as it traverses the U.S. states of Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. The river's source basin lies in the western United Stat ...

belonged to Tejas and Santa Fe de Nuevo México.

Oregon Country

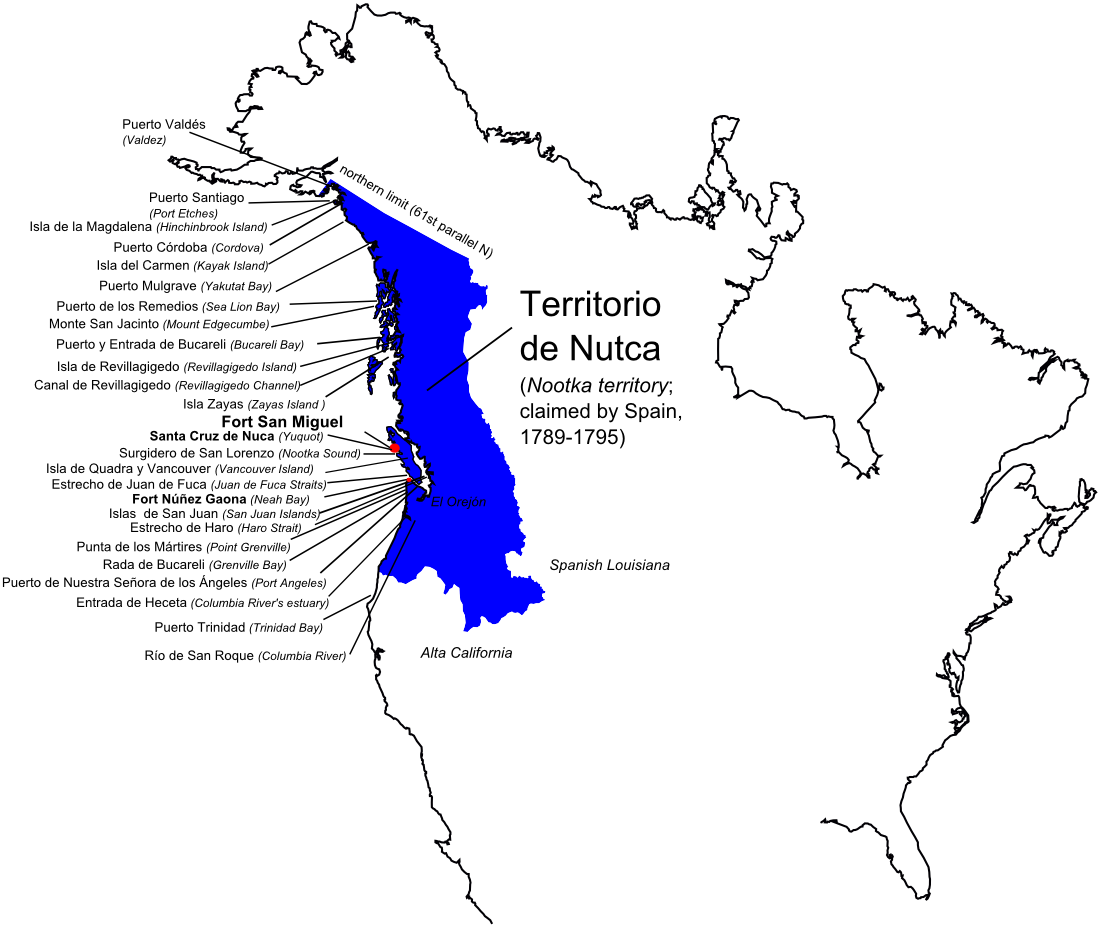

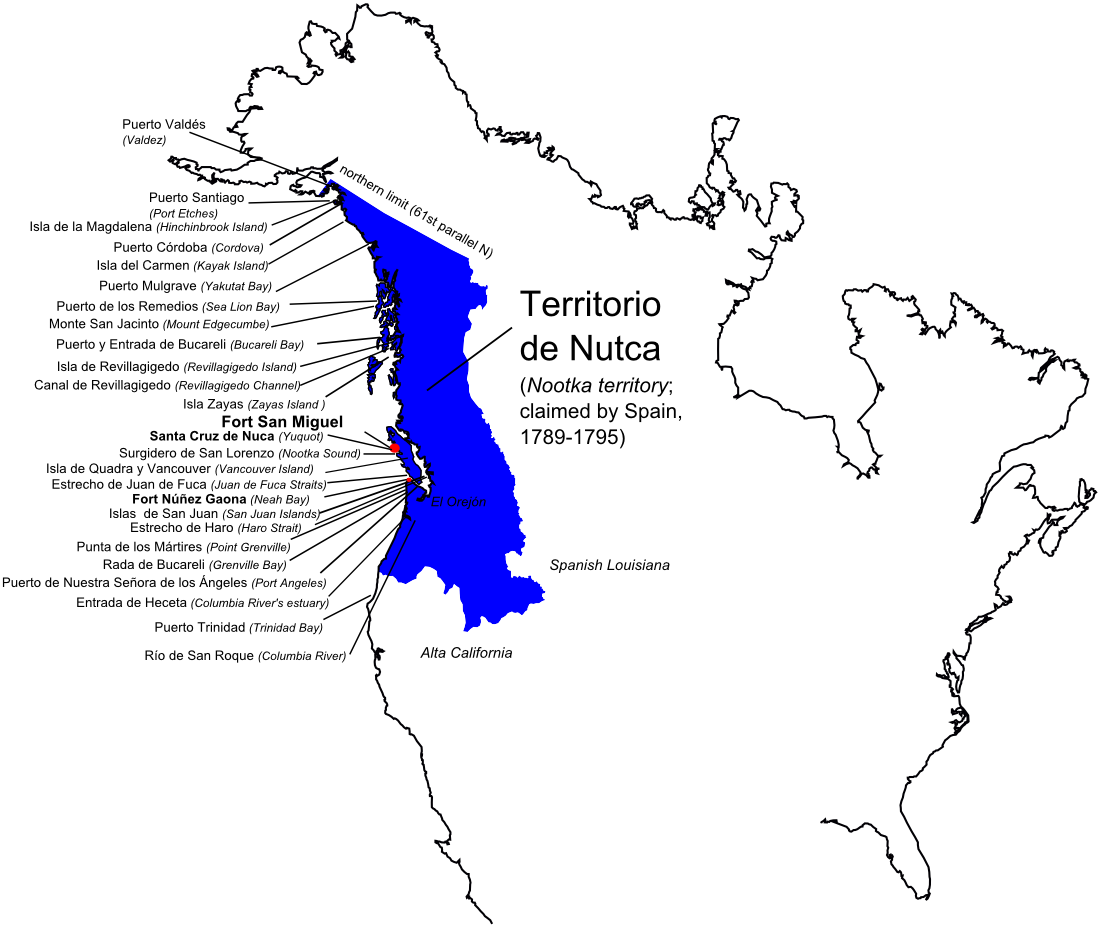

The British government claimed the region west of the Continental Divide between the undefined borders of Alta California and

The British government claimed the region west of the Continental Divide between the undefined borders of Alta California and Russian Alaska

Russian America (russian: Русская Америка, Russkaya Amerika) was the name for the Russian Empire's colonial possessions in North America from 1799 to 1867. It consisted mostly of present-day Alaska in the United States, but a ...

on the basis of (1) the third voyage of James Cook

James Cook's third and final voyage (12 July 1776 – 4 October 1780) took the route from Plymouth via Cape Town and Tenerife to New Zealand and the Hawaiian Islands, and along the North American coast to the Bering Strait.

Its ostensible ...

in 1778, (2) the Vancouver Expedition

The Vancouver Expedition (1791–1795) was a four-and-a-half-year voyage of exploration and diplomacy, commanded by Captain George Vancouver of the Royal Navy. The British expedition circumnavigated the globe and made contact with five continen ...

in 1791–1795, (3) the solo journey of Alexander Mackenzie to the North Bentinck Arm in 1792–1793, and (4) the exploration of David Thompson in 1807–1812. The Third Nootka Convention of 1794 stipulated that both the British and Spanish would abandon any settlements they had in the Nootka Sound.Carlos Calvo, ''Recueil complet des traités, conventions, capitulations, armistices et autres actes diplomatiques de tous les états de l'Amérique latine,'' Tome IIIe, Paris, Durand, 1862, pp.366-368/ref> The United States claimed essentially the same region on the basis of (1) Robert Gray's Columbia River expedition, the voyage of Robert Gray up the Columbia River in 1792, (2) the United States

Lewis and Clark Expedition

The Lewis and Clark Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery Expedition, was the United States expedition to cross the newly acquired western portion of the country after the Louisiana Purchase. The Corps of Discovery was a select gr ...

of 1804–1806, and (3) the establishment of Fort Astoria

Fort Astoria (also named Fort George) was the primary fur trading post of John Jacob Astor's Pacific Fur Company (PFC). A maritime contingent of PFC staff was sent on board the ''Tonquin (1807 ship), Tonquin'', while another party traveled overl ...

on the Columbia River in 1811. On 20 October 1818, the Anglo-American Convention of 1818 was signed setting the border between British North America and the United States east of the Continental Divide along the 49th parallel north and calling for joint Anglo-American occupancy west of the Great Divide. The Anglo-American Convention ignored the Nootka Convention of 1794 which gave Spain joint rights in the region. The convention also ignored Russian settlements in the region. The U.S. government referred to this region as the Oregon Country, while the British government referred to the region as the Columbia District

The Columbia District was a fur trading district in the Pacific Northwest region of British North America in the 19th century. Much of its territory overlapped with the disputed Oregon Country. It was explored by the North West Company betw ...

.

Russian America

On 16 July 1741, the crew of the

On 16 July 1741, the crew of the Imperial Russian Navy

The Imperial Russian Navy () operated as the navy of the Russian Tsardom and later the Russian Empire from 1696 to 1917. Formally established in 1696, it lasted until dissolved in the wake of the February Revolution of 1917. It developed from ...

ship ''Saint Peter

) (Simeon, Simon)

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Bethsaida, Gaulanitis, Syria, Roman Empire

, death_date = Between AD 64–68

, death_place = probably Vatican Hill, Rome, Italia, Roman Empire

, parents = John (or Jonah; Jona)

, occupat ...

'' (''Святой Пётр''), captained by Vitus Bering

Vitus Jonassen Bering (baptised 5 August 1681 – 19 December 1741),All dates are here given in the Julian calendar, which was in use throughout Russia at the time. also known as Ivan Ivanovich Bering, was a Danish cartographer and explorer in ...

, sighted Mount Saint Elias

Mount Saint Elias (also designated Boundary Peak 186), the second-highest mountain in both Canada and the United States, stands on the Yukon and Alaska border about southwest of Mount Logan, the highest mountain in Canada. The Canadian side of ...

, the fourth-highest summit in North America. While dispatched on the Russian Great Northern Expedition

The Great Northern Expedition (russian: Великая Северная экспедиция) or Second Kamchatka Expedition (russian: Вторая Камчатская экспедиция) was one of the largest exploration enterprises in hi ...

, they became the first Europeans to land in northwestern North America. The Russian fur trade soon followed the discovery. By 1812, the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

claimed Alaska and the Pacific Coast of North America as far south as the Russian settlement of Fortress Ross, only northwest of the Spain's Presidio Real de San Francisco.

New Spain

The Spanish Empire claimed all lands west of the Continental Divide throughout the Americas.The claim of Spain to all lands west of the Continental Divide in the Americas dated to the papal bull ''

The Spanish Empire claimed all lands west of the Continental Divide throughout the Americas.The claim of Spain to all lands west of the Continental Divide in the Americas dated to the papal bull ''Inter caetera

''Inter caetera'' ('Among other orks) was a papal bull issued by Pope Alexander VI on the 4 May () 1493, which granted to the Catholic Monarchs King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile all lands to the "west and south" of ...

'' issued by Pope Alexander VI on May 4, 1493, which granted to the Crowns of Castile and Aragon the rights to colonize all "pagan lands" 100 leagues west of the Azores

)

, motto =( en, "Rather die free than subjected in peace")

, anthem= ( en, "Anthem of the Azores")

, image_map=Locator_map_of_Azores_in_EU.svg

, map_alt=Location of the Azores within the European Union

, map_caption=Location of the Azores wi ...

and south of the Cabo Verde islands. This edict was superseded by the Treaty of Tordesillas signed on June 7, 1494, which divided the Earth into hemispheres along a meridian 370 leagues west of the Cabo Verde islands. In 1513, explorer Vasco Núñez de Balboa

Vasco Núñez de Balboa (; c. 1475around January 12–21, 1519) was a Spanish explorer, governor, and conquistador. He is best known for having crossed the Isthmus of Panama to the Pacific Ocean in 1513, becoming the first European to lead an ...

claimed the entire "Mar de Sur" (Pacific Ocean) and all lands adjacent for the Crowns of Castile and Aragon. Between 1774 and 1779, King Charles III of Spain ordered three naval expeditions north along the Pacific Coast to assert Spain's territorial claims. In July 1774, Juan José Pérez Hernández

Juan José Pérez Hernández (born Joan Perés c. 1725 – November 3, 1775), often simply Juan Pérez, was an 18th-century Spanish explorer. He was the first known European to sight, examine, name, and record the islands near present-day Br ...

reached latitude 54°40′ north off the northwestern tip of Langara Island before being forced to turn south. On 15 August 1775, Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra reached the latitude 59°0′ before returning south. On 23 July 1779, Ignacio de Arteaga y Bazán and Bodega y Quadra reached Puerto de Santiago on Isla de la Magdalena (now Port Etches Port Etches is a bay in the southcentral part of the U.S. state of Alaska. It is located on the west side of Hinchinbrook Island and opens onto Hinchinbrook Entrance, a strait between Hinchinbrook Island and Montague Island, connecting Prince Wil ...

on Hinchinbrook Island

Hinchinbrook Island (or Pouandai to the Biyaygiri people) is an island in the Cassowary Coast Region, Queensland, Australia. It lies east of Cardwell and north of Lucinda, separated from the north-eastern coast of Queensland by the narrow H ...

) where they held a formal possession ceremony commemorating Saint James, the patron saint

A patron saint, patroness saint, patron hallow or heavenly protector is a saint who in Catholicism, Anglicanism, or Eastern Orthodoxy is regarded as the heavenly advocate of a nation, place, craft, activity, class, clan, family, or perso ...

of Spain. This marked the northernmost Spanish exploration in the Pacific Ocean.

Between 1788 and 1793, Spain launched several more expeditions

Exploration refers to the historical practice of discovering remote lands. It is studied by geographers and historians.

Two major eras of exploration occurred in human history: one of convergence, and one of divergence. The first, covering most ...

north of Alta California. On 24 June 1789, Esteban José Martínez Fernández y Martínez de la Sierra Esteban () is a Spanish male given name, derived from Greek Στέφανος (Stéphanos) and related to the English names Steven and Stephen. Although in its original pronunciation the accent is on the penultimate syllable, English-speakers tend t ...

established the Spanish colony of Santa Cruz de Nuca

Santa Cruz de Nuca (or Nutca) was a Spanish colonial fort and settlement and the first European colony in what is now known as British Columbia. The settlement was founded on Vancouver Island in 1789 and abandoned in 1795, with its far northerl ...

on the northwest coast of Vancouver Island

Vancouver Island is an island in the northeastern Pacific Ocean and part of the Canadian province of British Columbia. The island is in length, in width at its widest point, and in total area, while are of land. The island is the largest by ...

. Asserting Spain's claim of exclusive sovereignty and navigation rights, Martínez seized several ships in Nootka Sound provoking the Nootka Crisis

The Nootka Crisis, also known as the Spanish Armament, was an international incident and political dispute between the Nuu-chah-nulth Nation, the Spanish Empire, the Kingdom of Great Britain, and the fledgling United States of America triggered b ...

with Great Britain. In negotiations to resolve the crisis, Spain claimed that its Nootka Territory extended north from Alta California to the 61st parallel north and from the Continental Divide west to the 147th meridian west. On 11 January 1794, the Spanish and British governments signed the Third Nootka Convention which called for the abandonment of all permanent settlements on Nootka Sound. Santa Cruz de Nuca was formally abandoned on 28 March 1795. The convention also stipulated that both nations were free to use Nootka Sound as a port and erect temporary structures, but, "neither ... shall form any permanent establishment in the said port or claim any right of sovereignty or territorial dominion there to the exclusion of the other. And Their said Majesties will mutually aid each other to maintain for their subjects free access to the port of Nootka against any other nation which may attempt to establish there any sovereignty or dominion". On 19 August 1796, Spain made the decision to join the French Republic in their war against Great Britain with the signing of the Second Treaty of San Ildefonso

The Second Treaty of San Ildefonso was signed on 19 August 1796 between the Spanish Empire and the First French Republic. Based on the terms of the agreement, France and Spain would become allies and combine their forces against the Kingdom of Grea ...

, thus ending Spanish and British cooperation in the Americas.

East of the Continental Divide, the Spanish Empire claimed all land south of the Arkansas River that was west of the Calcasieu River

The Calcasieu River ( ; french: Rivière Calcasieu) is a river on the Gulf Coast in southwestern Louisiana. Approximately long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed June 20, ...

.At the time of the treaty negotiations, the course of the Calcasieu, Red and Arkansas Rivers were only partially known and the location of the Continental Divide was yet to be determined. A modern definition of the border initially claimed by Spain begins at the mouth of Calcasieu Pass on the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico ( es, Golfo de México) is an ocean basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, largely surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United ...

(), thence up the Calcasieu River to its source (), thence due north (along meridian 93°12'47"W) to the Red River (), thence up the Red River to the meridian (99°15′19″W) of the source of the Medina River (), thence due north along that meridian (99°15′19″W) to the Arkansas River (), thence up the Arkansas River to its source (), thence due west (a distance of about along the parallel 39°15'30"N) to the Continental Divide (), thence northward along the Continental Divide presumably all the way to the Bering Strait. The vast disputed region between the territorial claims of the United States and Spain was occupied primarily by native peoples with very few traders of either Spain or the United States present. In the south, the disputed region between the Calcasieu River and the Sabine River encompassed Los Adaes

Los Adaes was the capital of Tejas on the northeastern frontier of New Spain from 1729 to 1770. It included a mission, San Miguel de Cuellar de los Adaes, and a presidio, Nuestra Señora del Pilar de Los Adaes (Our Lady of the Pillar of the Adae ...

, the first capital of Spanish Texas. The region between the Calcasieu and Sabine rivers become a lawless no man's land. The United States saw great potential in these western lands, and hoped to settle their borders. Spain, seeing the end of New Spain, hoped to employ its territorial claims before it would be forced to grant Mexico its independence

Independence is a condition of a person, nation, country, or state in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the statu ...

(later in 1821). Spain hoped to regain much of its territory after the regional demands for independence subsided.

Details of the treaty

The treaty, consisting of 16 articles was signed in Adams' State Department office at

The treaty, consisting of 16 articles was signed in Adams' State Department office at Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

, on February 22, 1819, by John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States ...

, U.S. Secretary of State

The United States secretary of state is a member of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States and the head of the U.S. Department of State. The office holder is one of the highest ranking members of the president's Ca ...

, and Luis de Onís

Luis is a given name. It is the Spanish form of the originally Germanic name or . Other Iberian Romance languages have comparable forms: (with an accent mark on the i) in Portuguese and Galician, in Aragonese and Catalan, while is archaic ...

, Spanish minister. Ratification was postponed for two years, because Spain wanted to use the treaty as an incentive to keep the United States from giving diplomatic support to the revolutionaries in South America. On February 24th, the U.S. Senate ratified the treaty unanimously,Marshall (1914), p. 63. but because of Spain's stalling, a new ratification was necessary and this time there were objections. Henry Clay and other Western spokesmen demanded that Spain also give up Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

. This proposal was defeated by the Senate, which ratified the treaty a second time on February 19, 1821, following ratification by Spain on October 24, 1820. Ratifications were exchanged three days later and the treaty was proclaimed on February 22, 1821, two years after the signing.

The Treaty closed the first era of United States expansion by providing for the cession of East Florida under Article 2; the abandonment of the controversy over West Florida under Article 2 (a portion of which had been seized by the United States); and the definition of a boundary with New Spain, that clearly made Texas a part of it, under Article 3, thus ending much of the vagueness in the boundary of the Louisiana Purchase. Spain also ceded to the U.S. its claims to the Oregon Country, under Article 3.

The U.S. did not pay Spain for Florida, but instead agreed to pay the legal claims of American citizens against Spain, to a maximum of $5 million, under Article 11.The U.S. commission established to adjudicate claims considered some 1,800 claims and agreed that they were collectively worth $5,454,545.13. Since the treaty limited the payment of claims to $5 million, the commission reduced the amount paid out proportionately by 8⅓ percent. Under Article 12, Pinckney's Treaty

Pinckney's Treaty, also known as the Treaty of San Lorenzo or the Treaty of Madrid, was signed on October 27, 1795 by the United States and Spain.

It defined the border between the United States and Spanish Florida, and guaranteed the United S ...

of 1795 between the U.S. and Spain was to remain in force. Under Article 15, Spanish goods received exclusive most-favored-nation privileges in the ports at Pensacola

Pensacola () is the westernmost city in the Florida Panhandle, and the county seat and only incorporated city of Escambia County, Florida, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, the population was 54,312. Pensacola is the principal ci ...

and St. Augustine for twelve years.

Under Article 2, the U.S. received ownership of Spanish Florida. Under Article 3, the U.S. relinquished its own claims on parts of Texas west of the Sabine River and other Spanish areas.

Border

Article 3 of the treaty states:The Boundary Line between the two Countries, West of the Mississippi, shall begin on theAt the time the treaty was signed, the course of the Sabine River, Red River, and Arkansas River had only been partially charted. Furthermore, the rivers changed course periodically. It would take many years before the location of the border would be fully determined. South of the 32nd parallel north, the Spanish Empire and the United States settled for the U.S. claim along the Sabine River. Between the meridians 94°2′45" and 100° west, the parties settled on the Spanish claim along the Red River. West of the 100th meridian west, the parties settled on the Spanish claim along the Arkansas River. From the source of the Arkansas River in theGulf of Mexico The Gulf of Mexico ( es, Golfo de México) is an ocean basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, largely surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United ..., at the mouth of the River Sabine in the Sea (), continuing North, along the Western Bank of that River, to the 32d degree of Latitude (); thence by a Line due North to the degree of Latitude, where it strikes the Rio Roxo of Nachitoches, or Red-River (), then following the course of the Rio-Roxo Westward to the degree of Longitude, 100 West from London and 23 from Washington (), then crossing the said Red-River, and running thence by a Line due North to the River Arkansas (), thence, following the Course of the Southern bank of the Arkansas to its source in Latitude, 42. North and thence by that parallel of Latitude to the South-Sea acific Ocean The whole being as laid down in Melishe's Map of the United States, published at Philadelphia, improved to the first of January 1818. But if the Source of the Arkansas River shall be found to fall North or South of Latitude 42, then the Line shall run from the said Source () due South or North, as the case may be, till it meets the said Parallel of Latitude 42 (), and thence along the said Parallel to the South Sea ().

Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico ...

, the parties settled on a border due north along that meridian (106°20′37″W) to the 42nd parallel north

The 42nd parallel north is a circle of latitude that is 42 degrees north of the Earth's equatorial plane. It crosses Europe, the Mediterranean Sea, Asia, the Pacific Ocean, North America, and the Atlantic Ocean.

At this latitude the sun is v ...

, thence west along the 42nd parallel to the Pacific Ocean.

Spain won substantial buffer zones around its provinces of Tejas, Santa Fe de Nuevo México, and Alta California in New Spain. While the United States relinquished substantial territory east of Continental Divide, the newly defined border allowed settlement of the southwestern part of the State of Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

, the Arkansas Territory

The Arkansas Territory was a territory of the United States that existed from July 4, 1819, to June 15, 1836, when the final extent of Arkansas Territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Arkansas. Arkansas Post was the first territo ...

, and the Missouri Territory

The Territory of Missouri was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from June 4, 1812, until August 10, 1821. In 1819, the Territory of Arkansas was created from a portion of its southern area. In 1821, a southea ...

.

Spain relinquished all claims in the Americas north of the 42nd parallel north. This was a historic retreat in its 327-year pursuit of lands in the Americas. The previous Anglo-American Convention of 1818 meant that both American and British citizens could settle land north of the 42nd parallel and west of the Continental Divide. The United States now had a firm foothold on the Pacific Coast and could commence settlement of the jointly occupied Oregon Country (known as the Columbia District

The Columbia District was a fur trading district in the Pacific Northwest region of British North America in the 19th century. Much of its territory overlapped with the disputed Oregon Country. It was explored by the North West Company betw ...

to the British government). The Russian Empire also claimed this entire region as part of Russian America.

For the United States, this Treaty (and the Treaty of 1818 with Britain agreeing to joint control of the Pacific Northwest) meant that its claimed territory now extended far west from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean. For Spain, it meant that it kept its colony of Texas and also kept a buffer zone between its colonies in California and New Mexico and the U.S. territories. Many historians consider the Treaty to be a great achievement for the U.S., as time validated Adams's vision that it would allow the U.S. to open trade with the Orient across the Pacific.

Informally this new border has been called the "Step Boundary", although the step-like shape of the boundary was not apparent for several decades—the source of the Arkansas, believed to be near the 42nd parallel north, was not known until John C. Frémont located it in the 1840s, hundreds of miles south of the 42nd parallel.

Implementation

Washington set up a commission, 1821 to 1824, that handled American claims against Spain. Many notable lawyers, includingDaniel Webster

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the U.S. Secretary of State under Presidents William Henry Harrison ...

and William Wirt, represented claimants before the commission. Dr. Tobias Watkins

Tobias Watkins (December 12, 1780 – November 14, 1855) was an American physician, editor, writer, educator, and political appointee in the Baltimore- Washington, D.C. area. He played leading roles in early American literary institutions such ...

served as secretary. During its term, the commission examined 1,859 claims arising from over 720 spoliation incidents, and distributed the $5 million in a basically fair manner.

The treaty reduced tensions with Spain (and after 1821 Mexico), and allowed budget cutters in Congress to reduce the army budget and reject the plans to modernize and expand the army proposed by Secretary of War John C. Calhoun. The treaty was honored by both sides, although inaccurate maps from the treaty meant that the boundary between Texas and Oklahoma remained unclear for most of the 19th century.

Later developments

Mexican War of Independence

The Mexican War of Independence ( es, Guerra de Independencia de México, links=no, 16 September 1810 – 27 September 1821) was an armed conflict and political process resulting in Mexico's independence from Spain. It was not a single, co ...

). Luis de Onís

Luis is a given name. It is the Spanish form of the originally Germanic name or . Other Iberian Romance languages have comparable forms: (with an accent mark on the i) in Portuguese and Galician, in Aragonese and Catalan, while is archaic ...

published a 152-page memoir on the diplomatic negotiation in 1820, which was translated from Spanish to English by US diplomatic commission secretary, Tobias Watkins in 1821.

Spain finally recognized the independence of Mexico with the Treaty of Córdoba

The Treaty of Córdoba established Mexican independence from Spain at the conclusion of the Mexican War of Independence. It was signed on August 24, 1821 in Córdoba, Veracruz, Mexico. The signatories were the head of the Army of the Three Guara ...

signed on August 24, 1821. While Mexico was not initially a party to the Adams–Onís Treaty, in 1831 Mexico ratified the treaty by agreeing to the 1828 Treaty of Limits with the U.S.

With the Russo-American Treaty of 1824

The Russo-American Treaty of 1824 (also known as the Convention of 1824) was signed in St. Petersburg between representatives of Russia and the United States on April 17, 1824, ratified by both nations on January 11, 1825 and went into effect on J ...

, the Russian Empire ceded its claims south of parallel 54°40′ north to the United States. With the Treaty of Saint Petersburg in 1825, Russia set the southern border of Alaska on the same parallel in exchange for the Russian right to trade south of that border and the British right to navigate north of that border. This set the absolute limits of the Oregon Country/Columbia District between the 42nd parallel north and the parallel 54°40′ north west of the Continental Divide.

By the mid-1830s, a controversy developed regarding the border with Texas, during which the United States demonstrated that the Sabine and Neches rivers had been switched on maps, moving the frontier in favor of Mexico. As a consequence, the eastern boundary of Texas was not firmly established until the independence of the Republic of Texas in 1836. It was not agreed upon by the United States and Mexico until the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ( es, Tratado de Guadalupe Hidalgo), officially the Treaty of Peace, Friendship, Limits, and Settlement between the United States of America and the United Mexican States, is the peace treaty that was signed on 2 ...

in 1848, which concluded the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

. That treaty also formalized the cession by Mexico of Alta California and today's American Southwest

The Southwestern United States, also known as the American Southwest or simply the Southwest, is a geographic and cultural region of the United States that generally includes Arizona, New Mexico, and adjacent portions of California, Colorado ...

, except for the territory of the later Gadsden Purchase of 1854.

Another dispute occurred after Texas joined the Union. The treaty stated that the boundary between the French claims on the north and the Spanish claims on the south was Rio Roxo de Natchitoches (Red River) until it reached the 100th meridian, as noted on the John Melish map of 1818. But, the 100th meridian on the Melish map was marked some east of the true 100th meridian, and the Red River forked about east of the 100th meridian. Texas claimed the land south of the North Fork, and the United States claimed the land north of the South Fork (later called the Prairie Dog Town Fork Red River

Prairie Dog Town Fork Red River is a sandy-braided stream about long, formed at the confluence of Palo Duro Creek and Tierra Blanca Creek, about northeast of Canyon in Randall County, Texas, and flowing east-southeastward to the Red River about ...

). In 1860 Texas organized the area as Greer County. The matter was not settled until a United States Supreme Court ruling in 1896 upheld federal claims to the territory, after which it was added to the Oklahoma Territory.

The treaty gave rise to a later border dispute between the states of Oregon and California, which remains unresolved. Upon statehood in 1850, California established the 42nd parallel as its constitutional de jure border as it had existed since 1819 when the territory was part of Spanish Mexico. In an 1868–1870 border survey following the admission of Oregon as a state, errors were made in demarcating and marking the Oregon-California border, creating a dispute that continues to this day.

In 2020, a hoax appeared in Spain according to which, in 2055, the Adams–Onís Treaty would expire and Florida would be returned to Spain by the United States, which is false.

See also

*List of treaties

This list of treaties contains known agreements, pacts, peaces, and major contracts between states, armies, governments, and tribal groups.

Before 1200 CE

1200–1299

1300–1399

1400–1499

1500–1599

1600–1699

1700–1799

...

* Spain–United States relations

* Spanish expeditions to the Pacific Northwest

* Stephen H. Long's Expedition of 1820, an outcome of the treaty

* Republic of East Florida

The Republic of East Florida, also known as the Republic of Florida or the Territory of East Florida, was a putative republic declared by insurgents against the Spanish rule of East Florida, most of whom were from Georgia. John Houstoun McIn ...

Footnotes

References

Bibliography

* * * , the standard history. * * Warren, Harris G. "Textbook Writers and the Florida" Purchase" Myth." ''Florida Historical Quarterly'' 41.4 (1963): 325-33online

* . ;Sources

Avalon Project – Treaty Text

External links

Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture – Adams–Onís Treaty

{{DEFAULTSORT:Adams-Onis Treaty 1819 treaties Boundary treaties New Spain Missouri Territory Spanish Florida Spanish Texas Treaties of the Spanish Empire Treaties of the United States Mexico–United States border 1819 in New Spain 1819 in the United States 1819 in Alta California 16th United States Congress History of United States expansionism Pre-statehood history of Florida Spain–United States relations Red River of the South February 1819 events Purchased territories