Abdul Qadeer Khan on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Abdul Qadeer Khan, (; ur, ; 1 April 1936 – 10 October 2021), known as A. Q. Khan, was a Pakistani

In April 1976, Khan joined the atomic bomb program and became part of the enrichment division, initially collaborating with Khalil Qureshi – a

In April 1976, Khan joined the atomic bomb program and became part of the enrichment division, initially collaborating with Khalil Qureshi – a

Many of his theorists were unsure that military-grade uranium would be feasible on time without the centrifuges, since Alam had notified PAEC that the "blueprints were incomplete" and "lacked the scientific information needed even for the basic gas-centrifuges." Calculations by Tasneem Shah, and confirmed by Alam, showed that Khan's earlier estimation of the quantity of uranium needing enrichment for the production of weapon-grade uranium was possible, even with the small number of centrifuges deployed.

Khan produced the designs of the centrifuges from

Many of his theorists were unsure that military-grade uranium would be feasible on time without the centrifuges, since Alam had notified PAEC that the "blueprints were incomplete" and "lacked the scientific information needed even for the basic gas-centrifuges." Calculations by Tasneem Shah, and confirmed by Alam, showed that Khan's earlier estimation of the quantity of uranium needing enrichment for the production of weapon-grade uranium was possible, even with the small number of centrifuges deployed.

Khan produced the designs of the centrifuges from  Scientists have said that Khan would have never got any closer to success without the assistance of Alam and others. The issue is controversial; Khan maintained to his biographer that when it came to defending the "centrifuge approach" and really putting work into it, both Shah and Alam refused.

Khan was also very critical of PAEC's concentrated efforts towards developing a plutonium ' implosion-type' nuclear devices and provided strong advocacy for the relatively simple ' gun-type' device that only had to work with high-enriched uranium – a design concept of gun-type device he eventually submitted to Ministry of Energy (MoE) and Ministry of Defense (MoD). Khan downplayed the importance of plutonium despite many of the theorists maintaining that "plutonium and the fuel cycle has its significance", and he insisted on the uranium route to the Bhutto administration when France's offer for an extraction plant was in the offing.

Though he had helped to come up with the centrifuge designs, and had been a long-time proponent of the concept, Khan was not chosen to head the development project to test his nation's first nuclear-weapons (his reputation of a thorny personality likely played a role in this) after India conducted its series of nuclear tests, '

Scientists have said that Khan would have never got any closer to success without the assistance of Alam and others. The issue is controversial; Khan maintained to his biographer that when it came to defending the "centrifuge approach" and really putting work into it, both Shah and Alam refused.

Khan was also very critical of PAEC's concentrated efforts towards developing a plutonium ' implosion-type' nuclear devices and provided strong advocacy for the relatively simple ' gun-type' device that only had to work with high-enriched uranium – a design concept of gun-type device he eventually submitted to Ministry of Energy (MoE) and Ministry of Defense (MoD). Khan downplayed the importance of plutonium despite many of the theorists maintaining that "plutonium and the fuel cycle has its significance", and he insisted on the uranium route to the Bhutto administration when France's offer for an extraction plant was in the offing.

Though he had helped to come up with the centrifuge designs, and had been a long-time proponent of the concept, Khan was not chosen to head the development project to test his nation's first nuclear-weapons (his reputation of a thorny personality likely played a role in this) after India conducted its series of nuclear tests, '

The innovation and improved designs of centrifuges were marked as classified for export restriction by the Pakistan government, though Khan was still in possession of earlier designs of centrifuges from when he worked for URENCO in the 1970s. In 1990, the United States alleged that highly sensitive information was being exported to North Korea in exchange for rocket engines. Pakistan's

The innovation and improved designs of centrifuges were marked as classified for export restriction by the Pakistan government, though Khan was still in possession of earlier designs of centrifuges from when he worked for URENCO in the 1970s. In 1990, the United States alleged that highly sensitive information was being exported to North Korea in exchange for rocket engines. Pakistan's

nuclear physicist

Nuclear physics is the field of physics that studies atomic nuclei and their constituents and interactions, in addition to the study of other forms of nuclear matter.

Nuclear physics should not be confused with atomic physics, which studies the ...

and metallurgical engineer

Metallurgy is a domain of materials science and engineering that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their inter-metallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are known as alloys.

Metallurgy encompasses both the s ...

. He was a key figure in Pakistan’s nuclear weapons program and is colloquially known as the "Father of Pakistan's atomic weapons program". He is a national hero in Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

.

An ''émigré

An ''émigré'' () is a person who has emigrated, often with a connotation of political or social self-exile. The word is the past participle of the French ''émigrer'', "to emigrate".

French Huguenots

Many French Huguenots fled France followin ...

(Muhajir

Muhajir or Mohajir ( ar, مهاجر, '; pl. , ') is an Arabic word meaning ''migrant'' (see immigration and emigration) which is also used in other languages spoken by Muslims, including English. In English, this term and its derivatives may refer ...

)'' from India who migrated to Pakistan in 1952, Khan was educated in the metallurgical engineering departments of Western European technical universities where he pioneered studies in phase transitions

In chemistry, thermodynamics, and other related fields, a phase transition (or phase change) is the physical process of transition between one state of a medium and another. Commonly the term is used to refer to changes among the basic states of ...

of metallic alloys, uranium metallurgy, and isotope separation

Isotope separation is the process of concentrating specific isotopes of a chemical element by removing other isotopes. The use of the nuclides produced is varied. The largest variety is used in research (e.g. in chemistry where atoms of "marker" ...

based on gas centrifuges. After learning of India's "Smiling Buddha

Operation Smiling BuddhaThis test has many code names. Civilian scientists called it "Operation Smiling Buddha" and the Indian Army referred to it as ''Operation Happy Krishna''. According to United States Military Intelligence, ''Operation H ...

" nuclear test in 1974, Khan joined his nation's clandestine efforts to develop atomic weapons

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bom ...

when he founded the Khan Research Laboratories

The Dr. A. Q. Khan Research Laboratories, ( ur, ) or KRL for short, is a federally funded, multi-program national research institute and national laboratory site primarily dedicated to uranium enrichment, supercomputing and fluid mechanics. It ...

(KRL) in 1976 and was both its chief scientist and director for many years.

In January 2004, Khan was subjected to a debriefing by the Musharraf administration over evidence of nuclear proliferation

Nuclear proliferation is the spread of nuclear weapons, fissionable material, and weapons-applicable nuclear technology and information to nations not recognized as " Nuclear Weapon States" by the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Wea ...

handed to them by the Bush administration of the United States. Khan admitted his role in running a nuclear proliferation network – only to retract his statements in later years when he leveled accusations at the former administration of Pakistan's Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto

Benazir Bhutto ( ur, بینظیر بُھٹو; sd, بينظير ڀُٽو; Urdu ; 21 June 1953 – 27 December 2007) was a Pakistani politician who served as the 11th and 13th prime minister of Pakistan from 1988 to 1990 and again from 1993 t ...

in 1990, and also directed allegations at President Musharraf over the controversy in 2008.

Khan was accused of selling nuclear secrets illegally and was put under house arrest in 2004. After years of house arrest, Khan successfully filed a lawsuit against the Federal Government of Pakistan

The Government of Pakistan ( ur, , translit=hakúmat-e pákistán) abbreviated as GoP, is a federal government established by the Constitution of Pakistan as a constituted governing authority of the four provinces, two autonomous territories, ...

at the Islamabad High Court

The Islamabad High Court is the senior court of the Islamabad Capital Territory, Pakistan, with appellate jurisdiction over the following district courts:

* Islamabad District Court (East)

* Islamabad District Court (West)

Justice Aamer Far ...

whose verdict declared his debriefing unconstitutional and freed him on 6 February 2009. The United States reacted negatively to the verdict and the Obama administration

Barack Obama's tenure as the 44th president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 2009, and ended on January 20, 2017. A Democrat from Illinois, Obama took office following a decisive victory over Republican ...

issued an official statement warning that Khan still remained a "serious proliferation risk".

After his death on 10 October 2021, he was given a state funeral

A state funeral is a public funeral ceremony, observing the strict rules of protocol, held to honour people of national significance. State funerals usually include much pomp and ceremony as well as religious overtones and distinctive elements of ...

at the National Mosque of Pakistan, Faisal Mosque before being buried at the H-8 graveyard in Islamabad

Islamabad (; ur, , ) is the capital city of Pakistan. It is the country's ninth-most populous city, with a population of over 1.2 million people, and is federally administered by the Pakistani government as part of the Islamabad Capital ...

, the capital of Pakistan.

Early life and education

Abdul Qadeer Khan was born on 1 April 1936, inBhopal

Bhopal (; ) is the capital city of the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh and the administrative headquarters of both Bhopal district and Bhopal division. It is known as the ''City of Lakes'' due to its various natural and artificial lakes. It i ...

, a city then in the erstwhile British Indian

British Indians are citizens of the United Kingdom (UK) whose ancestral roots are from India. This includes people born in the UK who are of Indian origin as well as Indians who have migrated to the UK. Today, Indians comprise about 1.4 mil ...

princely state of Bhopal State

Bhopal State (pronounced ) was an Islamic principality founded in the beginning of 18th-century India by the Afghan Mughal noble Dost Muhammad Khan. It was a tributary state during 18th century, a princely salute state with 19-gun salute ...

, and now the capital city of Madhya Pradesh

Madhya Pradesh (, ; meaning 'central province') is a state in central India. Its capital is Bhopal, and the largest city is Indore, with Jabalpur, Ujjain, Gwalior, Sagar, and Rewa being the other major cities. Madhya Pradesh is the second ...

. He is a Muhajir

Muhajir or Mohajir ( ar, مهاجر, '; pl. , ') is an Arabic word meaning ''migrant'' (see immigration and emigration) which is also used in other languages spoken by Muslims, including English. In English, this term and its derivatives may refer ...

of Urdu-speaking Pashtun

Pashtuns (, , ; ps, پښتانه, ), also known as Pakhtuns or Pathans, are an Iranian ethnic group who are native to the geographic region of Pashtunistan in the present-day countries of Afghanistan and Pakistan. They were historically r ...

origin. His father, Abdul Ghafoor, was a schoolteacher who once worked for the Ministry of Education

An education ministry is a national or subnational government agency politically responsible for education. Various other names are commonly used to identify such agencies, such as Ministry of Education, Department of Education, and Ministry of Pub ...

, and his mother, Zulekha, was a housewife with a very religious mindset. His older siblings, along with other family members, had emigrated to Pakistan during the bloody partition of India

The Partition of British India in 1947 was the change of political borders and the division of other assets that accompanied the dissolution of the British Raj in South Asia and the creation of two independent dominions: India and Pakistan. T ...

(splitting off the independent state of Pakistan) in 1947, who would often write to Khan's parents about the new life they had found in Pakistan.

After his matriculation

Matriculation is the formal process of entering a university, or of becoming eligible to enter by fulfilling certain academic requirements such as a matriculation examination.

Australia

In Australia, the term "matriculation" is seldom used now ...

from a local school in Bhopal, in 1952 Khan emigrated from India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area, the List of countries and dependencies by population, second-most populous ...

to Pakistan on the Sind Mail

Sind Mail was a passenger train that ran between Bombay and Karachi during the British era in British India. This train used to operate via Ahmedabad–Palanpur–Marwar–Pali–Jodhpur– Luni– Barmer–Munabao– Khokhrapar–Mirpur Khas–Hy ...

train, partly due to the reservation politics at that time, and religious violence in India

Religious violence in India includes acts of violence by followers of one religious group against followers and institutions of another religious group, often in the form of rioting. Religious violence in India has generally involved Hindus an ...

during his youth had left an indelible impression on his world view. Upon settling in Karachi

Karachi (; ur, ; ; ) is the most populous city in Pakistan and 12th most populous city in the world, with a population of over 20 million. It is situated at the southern tip of the country along the Arabian Sea coast. It is the former c ...

with his family, Khan briefly attended the D. J. Science College before transferring to the University of Karachi

The University of Karachi ( sd, ; informally Karachi University, KU, or UoK) is a public research university located in Karachi, Sindh, Pakistan. Established in June 1951 by an act of Parliament and as a successor to the University of Sindh ...

, where he graduated in 1956 with a Bachelor of Science

A Bachelor of Science (BS, BSc, SB, or ScB; from the Latin ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for programs that generally last three to five years.

The first university to admit a student to the degree of Bachelor of Science was the University o ...

(BSc) in physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which ...

with a concentration on solid-state physics

Solid-state physics is the study of rigid matter, or solids, through methods such as quantum mechanics, crystallography, electromagnetism, and metallurgy. It is the largest branch of condensed matter physics. Solid-state physics studies how th ...

.

From 1956 to 1959, Khan was employed by the Karachi Metropolitan Corporation

Karachi Metropolitan Corporation () is a public corporation and governing body to provide municipal services in Karachi, the largest city of Pakistan.

History

1852

Karachi Conservancy Board was established to control cholera epidemics in Kara ...

(city government

Local government is a generic term for the lowest tiers of public administration within a particular sovereign state. This particular usage of the word government refers specifically to a level of administration that is both geographically-loca ...

) as an Inspector of weights and measures, and applied for a scholarship

A scholarship is a form of financial aid awarded to students for further education. Generally, scholarships are awarded based on a set of criteria such as academic merit, diversity and inclusion, athletic skill, and financial need.

Scholars ...

that allowed him to study in West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 ...

. In 1961, Khan departed for West Germany to study material science at the Technical University

An institute of technology (also referred to as: technological university, technical university, university of technology, technological educational institute, technical college, polytechnic university or just polytechnic) is an institution of te ...

in West Berlin

West Berlin (german: Berlin (West) or , ) was a political enclave which comprised the western part of Berlin during the years of the Cold War. Although West Berlin was de jure not part of West Germany, lacked any sovereignty, and was under mi ...

, where he academically excelled in courses in metallurgy, but left West Berlin when he switched to the Delft University of Technology

Delft University of Technology ( nl, Technische Universiteit Delft), also known as TU Delft, is the oldest and largest Dutch public technical university, located in Delft, Netherlands. As of 2022 it is ranked by QS World University Rankings among ...

in the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

in 1965.

In 1962, while on vacation in The Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a city and municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's administrative centre and its seat of government, and while the official capital o ...

, he met Hendrina "Henny" Reternik – a British passport holder who had been born in South Africa to Dutch expatriates. She spoke Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

and had spent her childhood in Africa before returning with her parents to the Netherlands where she lived as a registered foreigner. In 1963, he married Henny in a modest Muslim ceremony at Pakistan's embassy in The Hague. Khan and Henny together had two daughters, Dina Khan - who is a doctor, and Ayesha Khan.

In 1967, Khan obtained an engineer's degree

An engineer's degree is an advanced academic degree in engineering which is conferred in Europe, some countries of Latin America, North Africa and a few institutions in the United States. The degree may require a thesis but always requires a non-a ...

in materials technology – an equivalent to a Master of Science

A Master of Science ( la, Magisterii Scientiae; abbreviated MS, M.S., MSc, M.Sc., SM, S.M., ScM or Sc.M.) is a master's degree in the field of science awarded by universities in many countries or a person holding such a degree. In contrast t ...

(MS) offered in English-speaking nations such as Pakistan – and joined the doctoral program

A doctorate (from Latin ''docere'', "to teach"), doctor's degree (from Latin ''doctor'', "teacher"), or doctoral degree is an academic degree awarded by universities and some other educational institutions, derived from the ancient formalism '' l ...

in metallurgical engineering at the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven

KU Leuven (or Katholieke Universiteit Leuven) is a Catholic research university in the city of Leuven, Belgium. It conducts teaching, research, and services in computer science, engineering, natural sciences, theology, humanities, medicine, ...

in Belgium. He worked under Belgian professor Martin J. Brabers at Leuven University

KU Leuven (or Katholieke Universiteit Leuven) is a Catholic research university in the city of Leuven, Belgium. It conducts teaching, research, and services in computer science, engineering, natural sciences, theology, humanities, medicine, ...

, who supervised his doctoral thesis

A thesis ( : theses), or dissertation (abbreviated diss.), is a document submitted in support of candidature for an academic degree or professional qualification presenting the author's research and findings.International Standard ISO 7144: ...

which Khan successfully defended, and graduated with a DEng Deng may refer to:

* Deng (company), is a Danish engineering, electrical, solar power and sales company in Accra, Ghana

* Deng (state), an ancient Chinese state

* Deng (Chinese surname), originated from the state

** Deng Xiaoping, paramount leader ...

in metallurgical engineering

Metallurgy is a domain of materials science and engineering that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their inter-metallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are known as alloys.

Metallurgy encompasses both the sci ...

in 1972. His thesis included fundamental work on martensite

Martensite is a very hard form of steel crystalline structure. It is named after German metallurgist Adolf Martens. By analogy the term can also refer to any crystal structure that is formed by diffusionless transformation.

Properties

M ...

and its extended industrial applications in the field of graphene morphology.

Career in Europe

In 1972, Khan joined the Physics Dynamics Research Laboratory (or inDutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

: FDO), an engineering firm subsidiary of Verenigde Machinefabrieken (VMF) based in Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Amstel'') is the capital and most populous city of the Netherlands, with The Hague being the seat of government. It has a population of 907,976 within the city proper, 1,558,755 in the urban ar ...

, from Brabers's recommendation. The FDO was a subcontractor for Ultra-Centrifuge Nederland of the, British-German-Dutch uranium enrichment

Enriched uranium is a type of uranium in which the percent composition of uranium-235 (written 235U) has been increased through the process of isotope separation. Naturally occurring uranium is composed of three major isotopes: uranium-238 (238 ...

consortium, URENCO

The Urenco Group is a British-German-Dutch nuclear fuel consortium operating several uranium enrichment plants in Germany, the Netherlands, United States, and United Kingdom. It supplies nuclear power stations in about 15 countries, and stat ...

which was operating a uranium enrichment plant in Almelo

Almelo () is a municipality and a city in the eastern Netherlands. The main population centres in the town are Aadorp, Almelo, Mariaparochie, and Bornerbroek.

Almelo has about 72,000 inhabitants in the middle of the rolling countryside of Twente, ...

and employed gaseous centrifuge method to assure a supply of nuclear fuel for nuclear power plants in the Netherlands. Soon after, Khan left FDO when URENCO offered him a senior technical position, initially conducting studies on the uranium metallurgy.

Uranium enrichment is an extremely difficult process because uranium in its natural state is composed of just 0.71% of uranium-235

Uranium-235 (235U or U-235) is an isotope of uranium making up about 0.72% of natural uranium. Unlike the predominant isotope uranium-238, it is fissile, i.e., it can sustain a nuclear chain reaction. It is the only fissile isotope that exi ...

(U235), which is a fissile material

In nuclear engineering, fissile material is material capable of sustaining a nuclear fission chain reaction. By definition, fissile material can sustain a chain reaction with neutrons of thermal energy. The predominant neutron energy may be t ...

, 99.3% of uranium-238

Uranium-238 (238U or U-238) is the most common isotope of uranium found in nature, with a relative abundance of 99%. Unlike uranium-235, it is non-fissile, which means it cannot sustain a chain reaction in a thermal-neutron reactor. However ...

(U238), which is non-fissile, and 0.0055% of uranium-234

Uranium-234 (234U or U-234) is an isotope of uranium. In natural uranium and in uranium ore, 234U occurs as an indirect decay product of uranium-238, but it makes up only 0.0055% (55 parts per million) of the raw uranium because its half-life ...

(U234), a daughter product

In nuclear physics, a decay product (also known as a daughter product, daughter isotope, radio-daughter, or daughter nuclide) is the remaining nuclide left over from radioactive decay. Radioactive decay often proceeds via a sequence of steps (de ...

which is also a non-fissile. The URENCO Group utilised the Zippe-type of centrifugal method to electromagnetically separate the isotopes

Isotopes are two or more types of atoms that have the same atomic number (number of protons in their nuclei) and position in the periodic table (and hence belong to the same chemical element), and that differ in nucleon numbers ( mass numbers ...

U234, U235, and U238 from sublimed raw uranium by rotating

Rotation, or spin, is the circular movement of an object around a '' central axis''. A two-dimensional rotating object has only one possible central axis and can rotate in either a clockwise or counterclockwise direction. A three-dimensional ...

the uranium hexafluoride (UF6) gas at up to ~100,000 revolutions per minute

Revolutions per minute (abbreviated rpm, RPM, rev/min, r/min, or with the notation min−1) is a unit of rotational speed or rotational frequency for rotating machines.

Standards

ISO 80000-3:2019 defines a unit of rotation as the dimensio ...

(rpm). Khan, whose work was based on physical metallurgy {{unreferenced, date=April 2017

Physical metallurgy is one of the two main branches of the scientific approach to metallurgy, which considers in a systematic way the physical properties of metals and alloys. It is basically the fundamentals and ap ...

of the uranium metal, eventually dedicated his investigations on improving the efficiency of the centrifuges by 1973–74.

Frits Veerman, Khan's colleague at FDO, uncovered nuclear espionage at Almelo where Khan had stolen designs of the centrifuges from URENCO for the nuclear weapons programme of Pakistan. Veerman became aware of the espionage when Khan had taken classified URENCO documents home to be copied and translated by his Dutch-speaking wife and had asked Veerman to photograph some of them. In 1975, Khan was transferred to a less sensitive section when URENCO became suspicious and he subsequently returned to Pakistan with his wife and two daughters. Khan was sentenced in absentia

is Latin for absence. , a legal term, is Latin for "in the absence" or "while absent".

may also refer to:

* Award in absentia

* Declared death in absentia, or simply, death in absentia, legally declared death without a body

* Election in ab ...

to four years in prison in 1983 by the Netherlands for espionage but the conviction was later overturned due to a legal technicality

The term legal technicality is a casual or colloquial phrase referring to a technical aspect of law. The phrase is not a term of art in the law; it has no exact meaning, nor does it have a legal definition. It implies that strict adherence to the ...

. Ruud Lubbers

Rudolphus Franciscus Marie "Ruud" Lubbers (; 7 May 1939 – 14 February 2018) was a Dutch politician, diplomat and businessman who served as Prime Minister of the Netherlands from 1982 to 1994, and as United Nations High Commissioner for Re ...

, Prime Minister of the Netherlands

The prime minister of the Netherlands ( nl, Minister-president van Nederland) is the head of the executive branch of the Government of the Netherlands. Although the monarch is the ''de jure'' head of government, the prime minister ''de facto'' ...

at the time, later said that the General Intelligence and Security Service

The General Intelligence and Security Service ( nl, Algemene Inlichtingen- en Veiligheidsdienst, AIVD; ) is the intelligence and security agency of the Netherlands, tasked with domestic, foreign and signals intelligence and protecting nationa ...

(BVD) was aware of Khan's espionage activities but he was allowed to continue due to pressure from the CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

, with the US backing Pakistan during the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

. This was also highlighted when despite Archie Pervez (Khan's associate for nuclear procurement in the US) being convicted in 1988, no action was taken against Khan or his proliferation network by the US government which needed the support of Pakistan during the Soviet–Afghan War

The Soviet–Afghan War was a protracted armed conflict fought in the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan from 1979 to 1989. It saw extensive fighting between the Soviet Union and the Afghan mujahideen (alongside smaller groups of anti-Soviet ...

.

, a Dutch engineer and businessman who had studied metallurgy with Khan at the Delft University of Technology, continued providing goods needed for enriching uranium to Khan in Pakistan through his company Slebos Research. Slebos was sentenced in 1985 to one year in prison but the sentence was reduced on appeal in 1986 to six months of probation and a fine of 20,000 guilders. Though Slebos continued to export goods to Pakistan and was again sentenced to one year in prison and a fine of around was imposed on his company.

Ernst Piffl, was convicted and sentenced to three and a half years in prison by Germany in 1998 for supplying nuclear centrifuge parts through his company Team GmbH to Khan's Khan Research Laboratories

The Dr. A. Q. Khan Research Laboratories, ( ur, ) or KRL for short, is a federally funded, multi-program national research institute and national laboratory site primarily dedicated to uranium enrichment, supercomputing and fluid mechanics. It ...

in Kahuta

Kahuta (Punjabi, Urdu: کہوٹہ) is a census-designated city and tehsil in the Rawalpindi District of Punjab Province, Pakistan. The population of the Kahuta Tehsil is approximately 220,576 at the 2017 census. Kahuta is the home to the Kahuta ...

. Asher Karni

Asher Karni ( he, אשר קרני; born 1954) is a South African and Israeli businessman known for his financial involvement and support for both the Pakistani and Israeli nuclear programs.

Biography

Asher Karni was born in Hungary. He moved ...

, a Hungarian-South African businessman was sentenced to three years in prison in the US for the sale of restricted nuclear equipment to Pakistan through Humayun Khan (an associate of A. Q. Khan) and his Pakland PME Corporation.

Scientific career in Pakistan

Smiling Buddha and initiation

Upon learning of India's surprise nuclear test, 'Smiling Buddha

Operation Smiling BuddhaThis test has many code names. Civilian scientists called it "Operation Smiling Buddha" and the Indian Army referred to it as ''Operation Happy Krishna''. According to United States Military Intelligence, ''Operation H ...

', in May 1974, Khan wanted to contribute to efforts to build an atomic bomb and met with officials at the Pakistani Embassy in The Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a city and municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's administrative centre and its seat of government, and while the official capital o ...

, who dissuaded him by saying it was "hard to find" a job in PAEC as a "metallurgist". In August 1974, Khan wrote a letter which went unnoticed, but he directed another letter through the Pakistani ambassador to the Prime Minister's Secretariat in September 1974.

Unbeknownst to Khan, his nation's scientists were already working towards feasibility of the atomic bomb under a secretive crash weapons program since 20 January 1972 that was being directed by Munir Ahmad Khan

Munir Ahmad Khan ( ur, ; 20 May 1926 – 22 April 1999), , was a Pakistani nuclear reactor physicist who is credited, among others, with being the "father of the atomic bomb program" of Pakistan for their leading role in developing their nati ...

, a reactor physicist, which calls into question of his "''father-of''" claim. After reading his letter, Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto

Zulfikar (or Zulfiqar) Ali Bhutto ( ur, , sd, ذوالفقار علي ڀٽو; 5 January 1928 – 4 April 1979), also known as Quaid-e-Awam ("the People's Leader"), was a Pakistani barrister, politician and statesman who served as the fourt ...

had his military secretary run a security check on Khan, who was unknown at that time, for verification and asked PAEC to dispatch a team under Bashiruddin Mahmood that met Khan at his family home in Almelo

Almelo () is a municipality and a city in the eastern Netherlands. The main population centres in the town are Aadorp, Almelo, Mariaparochie, and Bornerbroek.

Almelo has about 72,000 inhabitants in the middle of the rolling countryside of Twente, ...

and directed Bhutto's letter to meet him in Islamabad.Edward Nasim (23 July 2009). "Interview with Sultan Bashir Mahmood". Scientists of Pakistan. Season 1. 0:30 minutes in. Nawa-e-Waqt. Capital Studios. Upon arriving in December 1974, Khan took a taxi straight to the Prime Minister's Secretariat. He met with Prime Minister Bhutto in the presence of Ghulam Ishaq Khan

Ghulam Ishaq Khan ( ur, غلام اسحاق خان; 20 January 1915 – 27 October 2006), was a Pakistani bureaucrat who served as the seventh president of Pakistan, elected in 1988 following Zia's death until his resignation in 1993. He wa ...

, Agha Shahi

Agha Shahi ( ur, آغا شا ﮨی; 25 August 1920 – 6 September 2006), ''NI'', was a Pakistani career Foreign service officer who was the leading civilian figure in the military government of former President General Zia-ul-Haq from 1977 t ...

, and Mubashir Hassan

Mubashir Hassan ( ur, ; 22 January 1922 – 14 March 2020), was a Pakistani politician, humanist, political adviser, and an engineer who served in the capacity of Finance Minister in Bhutto administration from 1971 until 1974.

In 1967, Hass ...

where he explained the significance of highly enriched uranium, with the meeting ending with Bhutto's remark: "He seems to make sense."

The next day, Khan met with Munir Ahmad and other senior scientists where he focused the discussion on production of highly enriched uranium

Enriched uranium is a type of uranium in which the percent composition of uranium-235 (written 235U) has been increased through the process of isotope separation. Naturally occurring uranium is composed of three major isotopes: uranium-238 (238U ...

(HEU), against weapon-grade plutonium, and explained to Bhutto why he thought the idea of "plutonium" would not work. Later, Khan was advised by several officials in the Bhutto administration to remain in the Netherlands to learn more about centrifuge technology but continue to provide consultation on the Project-706

Project-706, also known as Project-786 was the codename of a research and development program to develop Pakistan's first nuclear weapons. The program was initiated by Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto in 1974 in response to the Indian nuc ...

enrichment program led by Mahmood. By December 1975, Khan was given a transfer to a less sensitive section when URENCO became suspicious of his indiscreet open sessions with Mahmood to instruct him on centrifuge technology. Khan began to fear for his safety in the Netherlands, ultimately insisting on returning home.

Khan Research Laboratories and atomic bomb program

physical chemist

Physical chemistry is the study of macroscopic and microscopic phenomena in chemical systems in terms of the principles, practices, and concepts of physics such as motion, energy, force, time, thermodynamics, quantum chemistry, statistical mech ...

. Calculations performed by him were valuable contributions to centrifuges and a vital link to nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

research, but continue to push for his ideas for feasibility of weapon-grade uranium even though it had a low priority, with most efforts still aimed to produce military-grade plutonium

Plutonium is a radioactive chemical element with the symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is an actinide metal of silvery-gray appearance that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exh ...

. Because of his interest in uranium metallurgy and his frustration at having been passed over for director of the uranium division (the job was instead given to Bashiruddin Mahmood), Khan refused to engage in further calculations and caused tensions with other researchers. Khan became highly unsatisfied and bored with the research led by Mahmood – finally, he submitted a critical report to Bhutto, in which he explained that the "enrichment program" was nowhere near success.

Upon reviewing the report, Bhutto sensed a great danger as the scientists were split between military-grade uranium and plutonium and informed Khan to take over the enrichment division from Mahmood, who separated the program from PAEC by founding the Engineering Research Laboratories

The Dr. A. Q. Khan Research Laboratories, ( ur, ) or KRL for short, is a federally funded, multi-program national research institute and national laboratory site primarily dedicated to uranium enrichment, supercomputing and fluid mechanics. It ...

(ERL). The ERL functioned directly under the Army's Corps of Engineers, with Khan being its chief scientist, and the army engineers located the national site at isolated lands in Kahuta

Kahuta (Punjabi, Urdu: کہوٹہ) is a census-designated city and tehsil in the Rawalpindi District of Punjab Province, Pakistan. The population of the Kahuta Tehsil is approximately 220,576 at the 2017 census. Kahuta is the home to the Kahuta ...

for the enrichment program as ideal site for preventing accidents.

The PAEC did not forgo their electromagnetic isotope separation

A calutron is a mass spectrometer originally designed and used for separating the isotopes of uranium. It was developed by Ernest Lawrence during the Manhattan Project and was based on his earlier invention, the cyclotron. Its name was derived ...

program, and a parallel program was led by G. D. Alam at the Air Research Laboratories (ARL) located at Chaklala Air Force Base, even though Alam had not seen a centrifuge, and only had a rudimentary knowledge of the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development undertaking during World War II that produced the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project w ...

. During this time, Alam accomplished a great feat by perfectly balancing the rotation of the first generation of centrifuge

A centrifuge is a device that uses centrifugal force to separate various components of a fluid. This is achieved by spinning the fluid at high speed within a container, thereby separating fluids of different densities (e.g. cream from milk) or ...

to ~30,000 rpm and was immediately dispatched to ERL which was suffering from many setbacks in setting up its own program under Khan's direction based on centrifuge technology dependent on URENCO's methods. Khan eventually committed to work on problems involving the differential equations concerning the rotation around fixed axis to perfectly balance the machine under influence of gravity and the design of first generation of centrifuges became functional after Khan and Alam succeeded in separating the 235U and 238U isotopes from raw natural uranium.

In the military circles, Khan's scientific ability was well recognised and was often known with his moniker "''Centrifuge Khan''" and the national laboratory was renamed after him upon the visit of President Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq

General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq HI, GCSJ, ร.ม.ภ, (Urdu: ; 12 August 1924 – 17 August 1988) was a Pakistani four-star general and politician who became the sixth President of Pakistan following a coup and declaration of martial law in ...

in 1983. In spite of his role, Khan was never in charge of the actual designs of the nuclear devices, their calculations, and eventual weapons testing which remained under the directorship of Munir Ahmad Khan and the PAEC.

The PAEC's senior scientists who worked with him and under him remember him as "an egomania

Egomania is a psychiatric term used to describe excessive preoccupation with one's ego, identity or selfdictionary.com and applies the same preoccupation to anyone who follows one’s own ungoverned impulses, is possessed by delusions of personal ...

cal lightweight" given to exaggerating his scientific achievements in centrifuges. At one point, Munir Khan said that, "most of the scientists who work on the development of atomic bomb projects were extremely 'serious'. They were sobered by the weight of what they don't know; Abdul Qadeer Khan is a showman." Viewed 7 January 2013. During the timeline of the bomb program, Khan published papers on analytical mechanics

In theoretical physics and mathematical physics, analytical mechanics, or theoretical mechanics is a collection of closely related alternative formulations of classical mechanics. It was developed by many scientists and mathematicians during the ...

of balancing of rotating masses and thermodynamics with mathematical rigour

Rigour (British English) or rigor (American English; see spelling differences) describes a condition of stiffness or strictness. These constraints may be environmentally imposed, such as "the rigours of famine"; logically imposed, such as m ...

to compete, but still failed to impress his fellow theorists at PAEC, generally in the physics community. In later years, Khan became a staunch critic of Munir Khan's research in physics, and on many occasions tried unsuccessfully to belittle Munir Khan's role in the atomic bomb projects. Their scientific rivalry became public and widely popular in the physics community and seminars held in the country over the years.

Nuclear tests: Chagai-I

Many of his theorists were unsure that military-grade uranium would be feasible on time without the centrifuges, since Alam had notified PAEC that the "blueprints were incomplete" and "lacked the scientific information needed even for the basic gas-centrifuges." Calculations by Tasneem Shah, and confirmed by Alam, showed that Khan's earlier estimation of the quantity of uranium needing enrichment for the production of weapon-grade uranium was possible, even with the small number of centrifuges deployed.

Khan produced the designs of the centrifuges from

Many of his theorists were unsure that military-grade uranium would be feasible on time without the centrifuges, since Alam had notified PAEC that the "blueprints were incomplete" and "lacked the scientific information needed even for the basic gas-centrifuges." Calculations by Tasneem Shah, and confirmed by Alam, showed that Khan's earlier estimation of the quantity of uranium needing enrichment for the production of weapon-grade uranium was possible, even with the small number of centrifuges deployed.

Khan produced the designs of the centrifuges from URENCO

The Urenco Group is a British-German-Dutch nuclear fuel consortium operating several uranium enrichment plants in Germany, the Netherlands, United States, and United Kingdom. It supplies nuclear power stations in about 15 countries, and stat ...

. However, they were riddled with serious technical errors, and while he bought some components for analysis, they were broken pieces, making them useless for quick assembly of a centrifuge. Its separative work unit (SWU) rate was extremely low, so that it would have to be rotated for thousands of RPMs at the cost of millions of taxpayers money, Alam maintained. Though Khan's knowledge of copper metallurgy greatly aided the it was the calculations and validation that came from his team of fellow theorists, including mathematician Tasneem Shah and Alam, who solved the differential equations

In mathematics, a differential equation is an equation that relates one or more unknown functions and their derivatives. In applications, the functions generally represent physical quantities, the derivatives represent their rates of change, an ...

concerning rotation around a fixed axis under the influence of gravity, which led Khan to come up with the innovative centrifuge designs.

Pokhran-II

The Pokhran-II tests were a series of five nuclear bomb Nuclear weapons testing, test explosions conducted by India at the Indian Army's Pokhran#Pokhran Nuclear Test Range, Pokhran Test Range in May 1998. It was the second instance of nuclear t ...

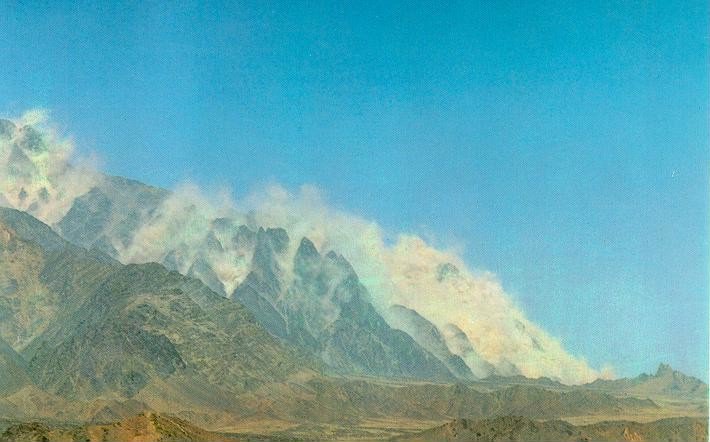

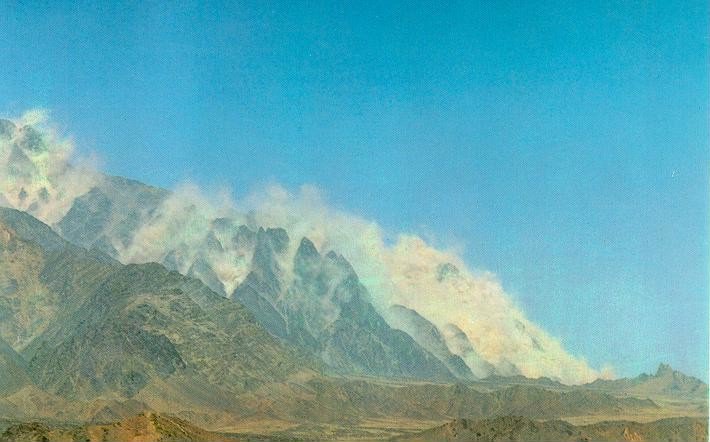

' in 1998. Intervention by the Chairman Joint Chiefs, General Jehangir Karamat, allowed Khan to be a participant and eye-witness his nation's first nuclear test, 'Chagai-I

Chagai-I is the code name of five simultaneous underground nuclear tests conducted by Pakistan at 15:15 hrs PKT on 28 May 1998. The tests were performed at Ras Koh Hills in the Chagai District of Balochistan Province.

Chagai-I was Pakistan' ...

' in 1998. At a news conference, Khan confirmed the testing of the boosted fission devices while stating that it was KRL's highly enriched uranium (HEU) that was used in the detonation of Pakistan's first nuclear devices on 28 May 1998.

Many of Khan's colleagues were irritated that he seemed to enjoy taking full credit for something he had only a small part in, and in response, he authored an article, "Torch-Bearers", which appeared in ''The News International

''The News International'', published in broadsheet size, is one of the largest English language newspapers in Pakistan. It is published daily from Karachi, Lahore and Rawalpindi/Islamabad. An overseas edition is published from London that cater ...

'', emphasising that he was not alone in the weapon's development. He made an attempt to work on the Teller–Ulam design

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a lo ...

for the hydrogen bomb, but the military strategists had objected to the idea as it went against the government's policy of minimum credible deterrence

Credible minimum deterrence is the principle on which India's nuclear strategy is based.

It underlines no first use (NFU) with an assured second strike capability and falls under minimal deterrence, as opposed to mutually assured destruction. I ...

. Khan often got engrossed in projects which were theoretically interesting but practically unfeasible.

Proliferation controversy

In the 1970s, Khan had been very vocal about establishing a network to acquire imported electronic materials from the Dutch firms and had very little trust of PAEC's domestic manufacturing of materials, despite the government accepting PAEC's arguments for the long term sustainability of the nuclear weapons program. At one point, Khan reached out to thePeople's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

for acquiring the uranium hexafluoride (UF6) when he attended a conference there – the Pakistani Government sent it back to the People's Republic of China, asking KRL to use the UF6 supplied by PAEC. In an investigative report published by Nuclear Threat Initiative

The Nuclear Threat Initiative, generally referred to as NTI, is a non-profit organization located in Washington, D.C. The American foreign policy think tank was founded in 2001 by former U.S. Senator Sam Nunn and describes itself as a "nonprofi ...

, Chinese scientists were reportedly present at Khan Research Laboratories

The Dr. A. Q. Khan Research Laboratories, ( ur, ) or KRL for short, is a federally funded, multi-program national research institute and national laboratory site primarily dedicated to uranium enrichment, supercomputing and fluid mechanics. It ...

(KRL) in Kahuta

Kahuta (Punjabi, Urdu: کہوٹہ) is a census-designated city and tehsil in the Rawalpindi District of Punjab Province, Pakistan. The population of the Kahuta Tehsil is approximately 220,576 at the 2017 census. Kahuta is the home to the Kahuta ...

in the early 1980s. In 1996, the U.S. intelligence community maintained that China provided magnetic rings for special suspension bearings mounted at the top of rotating centrifuge cylinders. In 2005, it was revealed that President Zia-ul-Haq's military government

A military government is generally any form of government that is administered by military forces, whether or not this government is legal under the laws of the jurisdiction at issue, and whether this government is formed by natives or by an occup ...

had KRL run a HEU programme in the Chinese nuclear weapons program.Kan, Shirley A. (2009). "§A.Q. Khan's nuclear network". China and Proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction and Missiles: Policy issues. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service

The Congressional Research Service (CRS) is a public policy research institute of the United States Congress. Operating within the Library of Congress, it works primarily and directly for members of Congress and their committees and staff on a ...

(CRS): Congressional Research Service (CRS). pp. 5–6. ISBN Congressional Research Service (CRS). Khan said that "KRL has built a centrifuge facility for China in Hanzhong

Hanzhong (; abbreviation: Han) is a prefecture-level city in the southwest of Shaanxi province, China, bordering the provinces of Sichuan to the south and Gansu to the west.

The founder of the Han dynasty, Liu Bang, was once enfeoffed as ...

city". China also exported some of DF-11

The Dong-Feng 11 (a.k.a. M-11, CSS-7) is a short-range ballistic missile developed by the People's Republic of China.

History

The DF-11 is a road-mobile short-range ballistic missile (SRBM) which began development in 1984 as the M-11, of whi ...

's ballistic missile

A ballistic missile is a type of missile that uses projectile motion to deliver warheads on a target. These weapons are guided only during relatively brief periods—most of the flight is unpowered. Short-range ballistic missiles stay within t ...

technology to Pakistan, where Pakistan's Ghaznavi and Shaheen-II

The Shaheen-II (Urdu:شاهين–اا; codename: Hatf–VI Shaheen) is a Pakistani land-based supersonic surface-to-surface medium-range guided ballistic missile. The ''Shaheen-II'' is designed and developed by the NESCOM and the National ...

borrowed from DF-11 technology.Duncan Lennox; ''Hatf 6 (Shaheen 2), Jane's Strategic Weapon Systems''; June 15, 2004.

In 1982, an unnamed Arab country reached out to Khan for the sale of centrifuge technology. Khan was very receptive to the financial offer, but one scientist alerted the Zia administration which investigated the matter, only for Khan to vehemently deny such an offer was made to him. The Zia administration tasked Major-General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Ali Nawab, an engineering officer, to keep surveillance on Khan, which he did until 1983 when he retired from his military service, and Khan's activities went undetected for several years after. Viewed 24 October 2012.

Court controversy and U.S. objections

In 1979, theDutch government

The politics of the Netherlands take place within the framework of a parliamentary representative democracy, a constitutional monarchy, and a decentralised unitary state.''Civil service systems in Western Europe'' edited by A. J. G. M. Bekk ...

eventually probed Khan on suspicion of nuclear espionage but he was not prosecuted due to lack of evidence, though it did file a criminal complaint against him in a local court in Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Amstel'') is the capital and most populous city of the Netherlands, with The Hague being the seat of government. It has a population of 907,976 within the city proper, 1,558,755 in the urban ar ...

, which sentenced him ''in absentia

is Latin for absence. , a legal term, is Latin for "in the absence" or "while absent".

may also refer to:

* Award in absentia

* Declared death in absentia, or simply, death in absentia, legally declared death without a body

* Election in ab ...

'' in 1985 to four years in prison. Upon learning of the sentence, Khan filed an appeal through his attorney, S. M. Zafar, who teamed up with the administration of Leuven University

KU Leuven (or Katholieke Universiteit Leuven) is a Catholic research university in the city of Leuven, Belgium. It conducts teaching, research, and services in computer science, engineering, natural sciences, theology, humanities, medicine, ...

, and successfully argued that the technical information requested by Khan was commonly found and taught in undergraduate and doctoral physics at the university – the court exonerated Khan by overturning his sentence on a legal technicality

The term legal technicality is a casual or colloquial phrase referring to a technical aspect of law. The phrase is not a term of art in the law; it has no exact meaning, nor does it have a legal definition. It implies that strict adherence to the ...

. Reacting to the suspicions of espionage, Khan stressed that: "I had requested for it as we had no library of our own at KRL, at that time. All the research work t Kahutawas the result of our innovation and struggle. We did not receive any technical 'know-how' from abroad, but we cannot reject the use of books, magazines, and research papers in this connection."

In 1979, the Zia administration, which was making an effort to keep their nuclear capability

Eight sovereign states have publicly announced successful detonation of nuclear weapons. Five are considered to be nuclear-weapon states (NWS) under the terms of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT). In order of acquisi ...

discreet to avoid pressure from the Reagan administration

Ronald Reagan's tenure as the 40th president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 1981, and ended on January 20, 1989. Reagan, a Republican from California, took office following a landslide victory over ...

of the United States (U.S.), nearly lost its patience with Khan when he reportedly attempted to meet with a local journalist to announce the existence of the enrichment program. During the Indian Operation Brasstacks

Operation Brasstacks was a major combined arms military exercise of the Indian Armed Forces in Rajasthan state of India, that took place from November 1986 to January 1987 near Pakistan border.

As part of a series of exercises to simulate th ...

military exercise in 1987, Khan gave another interview to local press and stated: "the Americans had been well aware of the success of the atomic quest of Pakistan", allegedly confirming the speculation of technology export. At both instances, the Zia administration sharply denied Khan's statement and a furious President Zia met with Khan and used a "tough tone", promising Khan severe repercussions had he not retracted all of his statements, which Khan immediately did by contacting several news correspondents.

In 1996, Khan again appeared on his country's news channels and maintained that "''at no stage was the program of producing 90% weapons-grade enriched uranium ever stopped''", despite Benazir Bhutto

Benazir Bhutto ( ur, بینظیر بُھٹو; sd, بينظير ڀُٽو; Urdu ; 21 June 1953 – 27 December 2007) was a Pakistani politician who served as the 11th and 13th prime minister of Pakistan from 1988 to 1990 and again from 1993 t ...

's administration reaching an understanding with the United States Clinton administration

Bill Clinton's tenure as the 42nd president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 1993, and ended on January 20, 2001. Clinton, a Democrat from Arkansas, took office following a decisive election victory over ...

to cap the program to 3% enrichment in 1990.

North Korea, Iran, and Libya

The innovation and improved designs of centrifuges were marked as classified for export restriction by the Pakistan government, though Khan was still in possession of earlier designs of centrifuges from when he worked for URENCO in the 1970s. In 1990, the United States alleged that highly sensitive information was being exported to North Korea in exchange for rocket engines. Pakistan's

The innovation and improved designs of centrifuges were marked as classified for export restriction by the Pakistan government, though Khan was still in possession of earlier designs of centrifuges from when he worked for URENCO in the 1970s. In 1990, the United States alleged that highly sensitive information was being exported to North Korea in exchange for rocket engines. Pakistan's Ghauri missile

The Ghauri–I ( ur, غوری-ا; official codename: Hatf–V Ghauri–I) is a land-based surface-to-surface medium-range ballistic missile, in current service with the Pakistan Army's Strategic Forces Command— a subordinate command of Stra ...

was based entirely on North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korean Peninsula and shares borders with China and Russia to the north, at the Yalu (Amnok) and T ...

's Rodong-1

The Hwasong-7 (; spelled Hwaseong-7 in South Korea, lit. Mars Type 7), also known as Nodong-1 (Hangul: ; Hanja: ), is a single- stage, mobile liquid propellant medium-range ballistic missile developed by North Korea. Developed in the mid-1980s, i ...

as reflected in its technology. The project was supported by Benazir Bhutto

Benazir Bhutto ( ur, بینظیر بُھٹو; sd, بينظير ڀُٽو; Urdu ; 21 June 1953 – 27 December 2007) was a Pakistani politician who served as the 11th and 13th prime minister of Pakistan from 1988 to 1990 and again from 1993 t ...

who consulted for the project with North Korea and facilitated the technology transfer

Technology transfer (TT), also called transfer of technology (TOT), is the process of transferring (disseminating) technology from the person or organization that owns or holds it to another person or organization, in an attempt to transform invent ...

to Khan Research Laboratories

The Dr. A. Q. Khan Research Laboratories, ( ur, ) or KRL for short, is a federally funded, multi-program national research institute and national laboratory site primarily dedicated to uranium enrichment, supercomputing and fluid mechanics. It ...

in 1993.

On multiple occasions, Khan levelled accusations against Benazir Bhutto's administration of providing secret enrichment information, on a compact disc

The compact disc (CD) is a digital optical disc data storage format that was co-developed by Philips and Sony to store and play digital audio recordings. In August 1982, the first compact disc was manufactured. It was then released in O ...

(CD), to North Korea; these accusations were denied by Benazir Bhutto's staff and military personnel.

Between 1987 and 1989, Khan secretly leaked knowledge of centrifuges to Iran without notifying the Pakistan Government, although this issue is a subject of political controversy. In 2003, the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are located primarily in Europe, Europe. The union has a total area of ...

pressured Iran to accept tougher inspections of its nuclear program and the International Atomic Energy Agency

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) is an intergovernmental organization that seeks to promote the peaceful use of nuclear energy and to inhibit its use for any military purpose, including nuclear weapons. It was established in 195 ...

(IAEA) revealed an enrichment facility in the city of Natanz

Natanz ( fa, نطنز, also romanized as Naţanz) is a city and capital of Natanz County, Isfahan Province, Iran. At the 2006 census, its population was 12,060, in 3,411 families. It is located south-east of Kashan.

Its bracing climate and l ...

, Iran, utilising gas centrifuges based on the designs and methods used by URENCO. The IAEA inspectors quickly identified the centrifuges as ''P-1'' types, which had been obtained "from a foreign intermediary in 1989", and the Iranian negotiators turned over the names of their suppliers, which identified Khan as one of them. Heinz Mebus, a German engineer and businessman and college friend of Khan, was named as one of the suppliers - acting as a middleman for Khan.

In May 1998, ''Newsweek

''Newsweek'' is an American weekly online news magazine co-owned 50 percent each by Dev Pragad, its president and CEO, and Johnathan Davis (businessman), Johnathan Davis, who has no operational role at ''Newsweek''. Founded as a weekly print m ...

'' reported that Khan had sent Iraq centrifuge designs, which were apparently confiscated by the UNMOVIC

The United Nations Monitoring, Verification and Inspection Commission (UNMOVIC) was created through the adoption of United Nations Security Council resolution 1284 of 17 December 1999 and its mission lasted until June 2007.

UNMOVIC was meant to ...

officials. Iraqi officials said "the documents were authentic but that they had not agreed to work with A. Q. Khan, fearing an ISI

ISI or Isi may refer to:

Organizations

* Intercollegiate Studies Institute, a classical conservative organization focusing on college students

* Ice Skating Institute, a trade association for ice rinks

* Indian Standards Institute, former name of ...

sting operation, due to strained relations between two countries.

In 2003, merchant vessel

A merchant ship, merchant vessel, trading vessel, or merchantman is a watercraft that transports cargo or carries passengers for hire. This is in contrast to pleasure craft, which are used for personal recreation, and naval ships, which are ...

'' BBC China'' was caught carrying nuclear centrifuges to Libya from Malaysia, the Scomi Group and Khan Research Laboratories

The Dr. A. Q. Khan Research Laboratories, ( ur, ) or KRL for short, is a federally funded, multi-program national research institute and national laboratory site primarily dedicated to uranium enrichment, supercomputing and fluid mechanics. It ...

were supplying nuclear parts to Libya through Khan's Dubai-based Sri Lankan associate Buhary Syed Abu Tahir. This was further revealed in the Scomi Precision Engineering nuclear scandal

Syarikat Scomi Precision Engineering Sdn Bhd (SCOPE) was established under the Scomi group of companies controlled by Kamaluddin Abdullah, a businessman who is the son of former Malaysian Prime Minister Abdullah Ahmad Badawi. On 4 February 2004, ...

surrounding Scomi CEO Shah Hakim Zain and , son of former Malaysian Prime Minister Abdullah Ahmad Badawi

Tun Abdullah bin Ahmad Badawi ( Jawi: عبد الله بن احمد بدوي; born 26 November 1939) is a Malaysian politician who served as the 5th Prime Minister of Malaysia from October 2003 to April 2009. He was also the sixth president of ...

.

Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Suda ...

negotiated with the United States to roll back its nuclear program to have economic sanctions lifted, effected by the Iran and Libya Sanctions Act

The Iran and Libya Sanctions Act of 1996 (ILSA) was a 1996 act of the United States Congress that imposed economic sanctions on firms doing business with Iran and Libya. On September 20, 2004, the President signed an Executive Order to terminate ...

, and shipped centrifuges to the United States that were identified as ''P-1'' models by the American inspectors. Ultimately, the Bush administration launched its investigation of Khan, focusing on his personal role, when Libya handed over a list of its suppliers. Friedrich Tinner

Friedrich Tinner, also known as Fred Tinner (born 1936), is a Swiss nuclear engineer and a long-associated friend of Abdul Qadeer Khan—Pakistan's former top scientist—and connected with the Khan nuclear network trafficking in the proliferati ...

, a nuclear engineer and friend of Khan since their days at the Leuven University

KU Leuven (or Katholieke Universiteit Leuven) is a Catholic research university in the city of Leuven, Belgium. It conducts teaching, research, and services in computer science, engineering, natural sciences, theology, humanities, medicine, ...

, was one of the heads of Libya's nuclear programme and worked in nuclear enrichment for Libya and Pakistan. In 2008, German nuclear engineer was convicted and sentenced to five years and six months in prison for procuring centrifuges for Libya from Khan, Lerch also acted as Khan's middleman for Iran. Alfred Hempel, a German businessman, arranged the shipment of gas centrifuge parts from Khan in Pakistan to Libya and Iran via Dubai.

The "A. Q. Khan network" involved numerous shell companies

A shell corporation is a company or corporation that exists only on paper and has no office and no employees, but may have a bank account or may hold passive investments or be the registered owner of assets, such as intellectual property, or ...

set-up by Khan in Dubai to obtain equipment necessary for nuclear enrichment. of Iran's Defense Industries Organization

The Defense Industries Organization (DIO) is a Conglomerate (company), conglomerate of companies run by the Iran, Islamic Republic of Iran whose function is to provide the Armed Forces of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Armed Forces with the necessar ...

was involved in nuclear proliferation

Nuclear proliferation is the spread of nuclear weapons, fissionable material, and weapons-applicable nuclear technology and information to nations not recognized as " Nuclear Weapon States" by the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Wea ...

for Iran and North Korea through China. Parts needed for nuclear enrichment in Pakistan were also imported by Khan from several Japanese companies.

Security hearings, pardon, and aftermath

Starting in 2001, Khan served as an adviser on science and technology in the Musharraf administration and had become a public figure who enjoyed much support from his country's political conservative sphere. In 2003, the Bush administration reportedly turned over evidence of anuclear proliferation

Nuclear proliferation is the spread of nuclear weapons, fissionable material, and weapons-applicable nuclear technology and information to nations not recognized as " Nuclear Weapon States" by the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Wea ...

network that implicated Khan's role to the Musharraf administration. Khan was dismissed from his post on 31 January 2004. On 4 February 2004, Khan appeared on Pakistan Television

Pakistan Television Corporation ( ur, ; reporting name: PTV) is the Pakistani state-owned broadcaster. Pakistan entered the television broadcasting age in 1964, with a pilot television station established at Lahore.

Background

Historical c ...

(PTV) and confessed to running a proliferation ring, and transferring technology to Iran between 1989 and 1991, and to North Korea and Libya between 1991 and 1997. The Musharraf administration avoided arresting Khan but launched security hearings on Khan who confessed to the military investigators that former Chief of Army Staff General Mirza Aslam Beg

General Mirza Aslam Beg ( ur, ; born 2 August 1931), also known as M. A. Beg, was a Pakistan Army officer, who served as the 3rd Chief of Army Staff from 1988 until his retirement in 1991. His appointment as chief of army staff came when hi ...

had given authorisation for technology transfer to Iran.

On 5 February 2004, President Pervez Musharraf

General Pervez Musharraf ( ur, , Parvez Muśharraf; born 11 August 1943) is a former Pakistani politician and four-star general of the Pakistan Army who became the tenth president of Pakistan after the successful military takeover of t ...

issued a pardon to Khan as he feared that the issue would be politicised by his political rivals.

Bill Powell and Tim McGirk, "The Man Who Sold the Bomb; How Pakistan's A.Q. Khan outwitted Western intelligence to build a global nuclear-smuggling ring that made the world a more dangerous place", ''Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and event (philosophy), events that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various me ...

'', 14 February 2005, p. 22. Despite the pardon, Khan, who had strong conservative support, had badly damaged the political credibility of the Musharraf administration and the image of the United States who was attempting to win hearts and minds __NOTOC__

Winning hearts and minds is a concept occasionally expressed in the resolution of war, insurgency, and other conflicts, in which one side seeks to prevail not by the use of superior force, but by making emotional or intellectual appeals ...

of local populations during the height of the Insurgency in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

The insurgency in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, also known as the War in North-West Pakistan or Pakistan's war on terror, is an ongoing armed conflict involving Pakistan, and Islamist militant groups such as the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), Jund ...

. While the local television news media aired sympathetic documentaries on Khan, the opposition parties in the country protested so strongly that the U.S. Embassy in Islamabad

The Embassy of the United States in Islamabad is the diplomatic mission of the United States in Pakistan. The embassy in Islamabad is one of the largest U.S. embassies in the world, in terms of personnel, and houses a chancery and complex of ...

had pointed out to the Bush administration that the successor to Musharraf could be less friendly towards the United States. This restrained the Bush administration from applying further ''direct'' pressure on Musharraf due to a strategic calculation that it might cause the loss of Musharraf as an ally.

In December 2006, the Weapons of Mass Destruction Commission The Weapons of Mass Destruction Commission (WMDC) is established on an initiative by the late Foreign Minister of Sweden, Anna Lindh, acting on a proposal by then United Nations Under-Secretary-General Jayantha Dhanapala. The Swedish Government invi ...

(WMDC), headed by Hans Blix

Hans Martin Blix (; born 28 June 1928) is a Swedish diplomat and politician for the Liberal People's Party. He was Swedish Minister for Foreign Affairs (1978–1979) and later became the head of the International Atomic Energy Agency. As suc ...

, stated that Khan could not have acted alone "without the awareness of the Pakistan Government". Blix's statement was also reciprocated by the United States government, with one anonymous American government intelligence official quoted by independent journalist and author Seymour Hersh

Seymour Myron "Sy" Hersh (born April 8, 1937) is an American Investigative journalism, investigative journalist and political writer.

Hersh first gained recognition in 1969 for exposing the My Lai Massacre and its cover-up during the Vietnam Wa ...

: "Suppose if Edward Teller

Edward Teller ( hu, Teller Ede; January 15, 1908 – September 9, 2003) was a Hungarian-American theoretical physicist who is known colloquially as "the father of the hydrogen bomb" (see the Teller–Ulam design), although he did not care for ...

had suddenly decided to spread nuclear technology around the world. Could he really do that without the American government knowing?".

In 2007, the U.S. and European Commission

The European Commission (EC) is the executive of the European Union (EU). It operates as a cabinet government, with 27 members of the Commission (informally known as "Commissioners") headed by a President. It includes an administrative body ...

politicians as well as IAEA officials had made several strong calls to have Khan interrogated by IAEA investigators, given the lingering scepticism about the disclosures made by Pakistan, but Prime Minister Shaukat Aziz

Shaukat Aziz ( ur, ; born 6 March 1949) is a Pakistani former banker and financier who served as 17th prime minister of Pakistan from 28 August 2004 to 15 November 2007, as well as the finance minister of Pakistan from 6 November 1999 to 15 ...

, who remained supportive of Khan and spoke highly of him, strongly dismissed the calls by terming it as "case closed".

In 2008, the security hearings were officially terminated by Chairman joint chiefs General Tariq Majid

General Tariq Majid ( ur, ; born 23 August 1950) is a retired four-star rank army general in the Pakistan Army who served as the 13th Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee from 2007 to 2010, the principal and highest-ranking militar ...

who marked the details of debriefings as "''classified''". In 2008, in an interview, Khan laid the whole blame on former President Pervez Musharraf, and labelled Musharraf as the "''Big Boss''" for proliferation deals. In 2012, Khan also implicated Benazir Bhutto's administration in proliferation matters, pointing to the fact as she had issued "clear directions in thi regard." Khan also said that he was persecuted because he was a Muhajir

Muhajir or Mohajir ( ar, مهاجر, '; pl. , ') is an Arabic word meaning ''migrant'' (see immigration and emigration) which is also used in other languages spoken by Muslims, including English. In English, this term and its derivatives may refer ...

.

Government work, academia, and political advocacy

Khan's strong advocacy fornuclear sharing

Nuclear sharing is a concept in NATO's policy of nuclear deterrence, which allows member countries without nuclear weapons of their own to participate in the planning for the use of nuclear weapons by NATO. In particular, it provides for the ar ...

of technology eventually led to his ostracisation by much of the scientific community, but Khan was still quite welcome in his country's political and military circles. After leaving the directorship of the Khan Research Laboratories in 2001, Khan briefly joined the Musharraf administration as a policy adviser on science and technology on a request from President Musharraf. In this capacity, Khan promoted increased defence spending on his nation's missile program to counter the perceived threats from the Indian missile program and advised the Musharraf administration on space policy. He presented the idea of using the ''Ghauri'' missile system as an expendable launch system