Australian Republic on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Republicanism in Australia is a movement to change Australia's system of government from a

Some leaders and participants of the revolt at the

Some leaders and participants of the revolt at the

At the Australian Federation Convention, which produced the first draft that was to become the

At the Australian Federation Convention, which produced the first draft that was to become the

, Robert Harris Oration, 12th Convention of the Royal Australasian College of Dental Surgeons, Canberra, 16 April 1994 However beginning with

online version

*Flint, David, ''The Cane Toad Republic'' Wakefield Press (1999) *Goot, Murray, "Contingent Inevitability: Reflections on the Prognosis for Republicanism" (1994) in George Winterton (ed), ''We, the People: Australian Republican Government'' (1994), pp 63–96 *Hirst, John., ''A Republican Manifesto,'' Oxford University Press (1994) *Jones, Benjamin T, ''This Time: Australia’s Republican Past and Future'', Schwartz Publishing Pty Ltd 2018 *Keating, P. J., ''An Australian Republic: The Way Forward,'' Australian Government Publishing Service (1995) *Mackay, Hugh, ''Turning Point. Australians Choosing Their Future'', Pan Macmillan, Sydney, New South Wales, C. 18, 'Republic. The people have their say.' (1999) * * McKenna, Mark, ''The Captive Republic: A History of Republicanism in Australia 1788–1996'' (1998) *McKenna, Mark, ''The Traditions of Australian Republicanism'' (1996

online version

*McKenna, Mark, ''The Nation Reviewed'' (March 2008, ''

online version

*Stephenson, M. and Turner, C. (eds.), ''Australia Republic or Monarchy? Legal and Constitutional Issues'', University of Queensland Press (1994) *Vizard, Steve, ''Two Weeks in Lilliput: Bear Baiting and Backbiting At the Constitutional Convention'' (Penguin, 1998, ) *Warden, J., "The Fettered Republic: The Anglo American Commonwealth and the Traditions of Australian Political Thought," ''Australian Journal of Political Science,'' Vol. 28, 1993. pp. 84–85. *Wark, McKenzie, ''The Virtual Republic: Australia's Culture Wars of the 1990s'' (1998) *Winterton, George. ''Monarchy to Republic: Australian Republican Government'' Oxford University Press (1986). *Winterton, George (ed), ''We, the People: Australian Republican Government'', Allen & Unwin (1994), *Woldring, Klaas, '' Australia: Republic or US Colony?'' (2006)

Australian Republican Movement (official website)

Australians for Constitutional Monarchy (official website)Australian Monarchist League (official website)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Republicanism In Australia

constitutional monarchy

Constitutional monarchy, also known as limited monarchy, parliamentary monarchy or democratic monarchy, is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in making decisions. ...

to a republic

A republic, based on the Latin phrase ''res publica'' ('public affair' or 'people's affair'), is a State (polity), state in which Power (social and political), political power rests with the public (people), typically through their Representat ...

; presumably, a form of parliamentary republic

A parliamentary republic is a republic that operates under a parliamentary system of government where the Executive (government), executive branch (the government) derives its legitimacy from and is accountable to the legislature (the parliament). ...

that would replace the monarch of Australia

The monarchy of Australia is a key component of Australia's form of government, by which a hereditary monarch serves as the country's sovereign and head of state. It is a constitutional monarchy, modelled on the Westminster system of parli ...

(currently King Charles III

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms.

Charles was born at Buckingham Palace during the reign of his maternal grandfather, King George VI, and ...

) with a non-royal Australian

Australian(s) may refer to:

Australia

* Australia, a country

* Australians, citizens of the Commonwealth of Australia

** European Australians

** Anglo-Celtic Australians, Australians descended principally from British colonists

** Aboriginal Aus ...

head of state

A head of state is the public persona of a sovereign state.#Foakes, Foakes, pp. 110–11 "

. It is opposed to monarchism in Australia. Republicanism was first espoused in Australia before he head of state

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (letter), the fifth letter of the Semitic abjads

* He (pronoun), a pronoun in Modern English

* He (kana), one of the Japanese kana (へ in hiragana and ヘ in katakana)

* Ge (Cyrillic), a Cyrillic letter cal ...

being an embodiment of the State itself or representative of its international persona." The name given to the office of head of sta ...Federation

A federation (also called a federal state) is an entity characterized by a political union, union of partially federated state, self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a #Federal governments, federal government (federalism) ...

in 1901. After a period of decline following Federation, the movement again became prominent at the end of the 20th century after successive legal and socio-cultural changes loosened Australia's ties with the United Kingdom.

In a referendum held in 1999, Australian voters rejected a proposal to establish a republic with a parliamentary appointed head of state. This was despite polls showing a majority of Australians supported a republic in principle for some years before the vote.

Republicanism is officially supported by the Labor Party and the Greens. It is supported by some members of the Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world.

The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left. For example, while the political systems ...

and other members of the Australian Parliament

The Parliament of Australia (officially the Parliament of the Commonwealth and also known as the Federal Parliament) is the federal legislature of Australia. It consists of three elements: the Monarchy of Australia, monarch of Australia (repr ...

. Under the first Albanese ministry

The first Albanese ministry was the 73rd ministry of the Government of Australia. It was led by the country's 31st Prime Minister, Anthony Albanese. The Albanese ministry succeeded the second Morrison ministry, which resigned on 23 May 2022 ...

, there was an assistant minister for the republic from 1 June 2022 until 29 July 2024.

History

Before federation

In his journal ''The Currency Lad'', first published in Sydney in 1832, pastoralist and politicianHoratio Wills

Horatio Spencer Howe Wills (5 October 1811 – 17 October 1861) was an Australian pastoralist, politician and newspaper owner.

Biography

Born in Sydney in the British penal colony of New South Wales, Wills grew up on George Street with his ...

was the first person to openly espouse Australian republicanism. Born to a convict

A convict is "a person found guilty of a crime and sentenced by a court" or "a person serving a sentence in prison". Convicts are often also known as "prisoners" or "inmates" or by the slang term "con", while a common label for former convicts ...

father, Wills was devoted to the emancipist

An emancipist was a convict sentenced and transported under the convict system to Australia, who had been given a conditional or absolute pardon. The term was also used to refer to those convicts whose sentences had expired, and might sometimes ...

cause and promoted the interests of " currency lads and lasses" (Australian-born Europeans).

Eureka Stockade

The Eureka Rebellion was a series of events involving gold miners who revolted against the British administration of the colony of Victoria, Australia, during the Victorian gold rush. It culminated in the Battle of the Eureka Stockade, wh ...

in 1854 held republican views and the incident has been used to encourage republicanism in subsequent years, with the Eureka Flag

The Eureka Flag was flown at the Battle of the Eureka Stockade, which took place on 3 December 1854 at Ballarat in Victoria, Australia. It was the culmination of the 1851 to 1854 Eureka Rebellion on the Victorian goldfields. Gold miners prot ...

appearing in connection with some republican groups. The Australian Republican Association (ARA) was founded in response to the Eureka Stockade, advocating the abolition of governors and their titles, the revision of the penal code, payment of members of parliament, the nationalisation of land and an independent federal Australian republic outside of the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

. David Flint

David Edward Flint (born 1938) is an Australian legal academic, known for his leadership of Australians for Constitutional Monarchy and for his tenure as head of the Australian Broadcasting Authority.

Early life and education

David Flint was ...

, the national convener of Australians for Constitutional Monarchy

Australians for Constitutional Monarchy (ACM) is a group that aims to preserve Australia's constitutional monarchy, with Charles III as King of Australia. The group states that it is a non-partisan, not-for-profit organisation whose role is "To ...

, notes that a movement emerged in favour of a White Australia policy; however British authorities in Whitehall

Whitehall is a road and area in the City of Westminster, Central London, England. The road forms the first part of the A roads in Zone 3 of the Great Britain numbering scheme, A3212 road from Trafalgar Square to Chelsea, London, Chelsea. It ...

were opposed to segregational laws. He suggests that to circumvent Westminster, those in favour of the discriminatory policies backed the proposed secession from the Empire as a republic.

One attendee of the ARA meetings was the Australian-born poet Henry Lawson

Henry Archibald Hertzberg Lawson (17 June 1867 – 2 September 1922) was an Australian writer and bush poet. Along with his contemporary Banjo Paterson, Lawson is among the best-known Australian poets and fiction writers of the colonial period ...

, who wrote his first poem, entitled ''A Song of the Republic'', in ''The Republican'' journal.

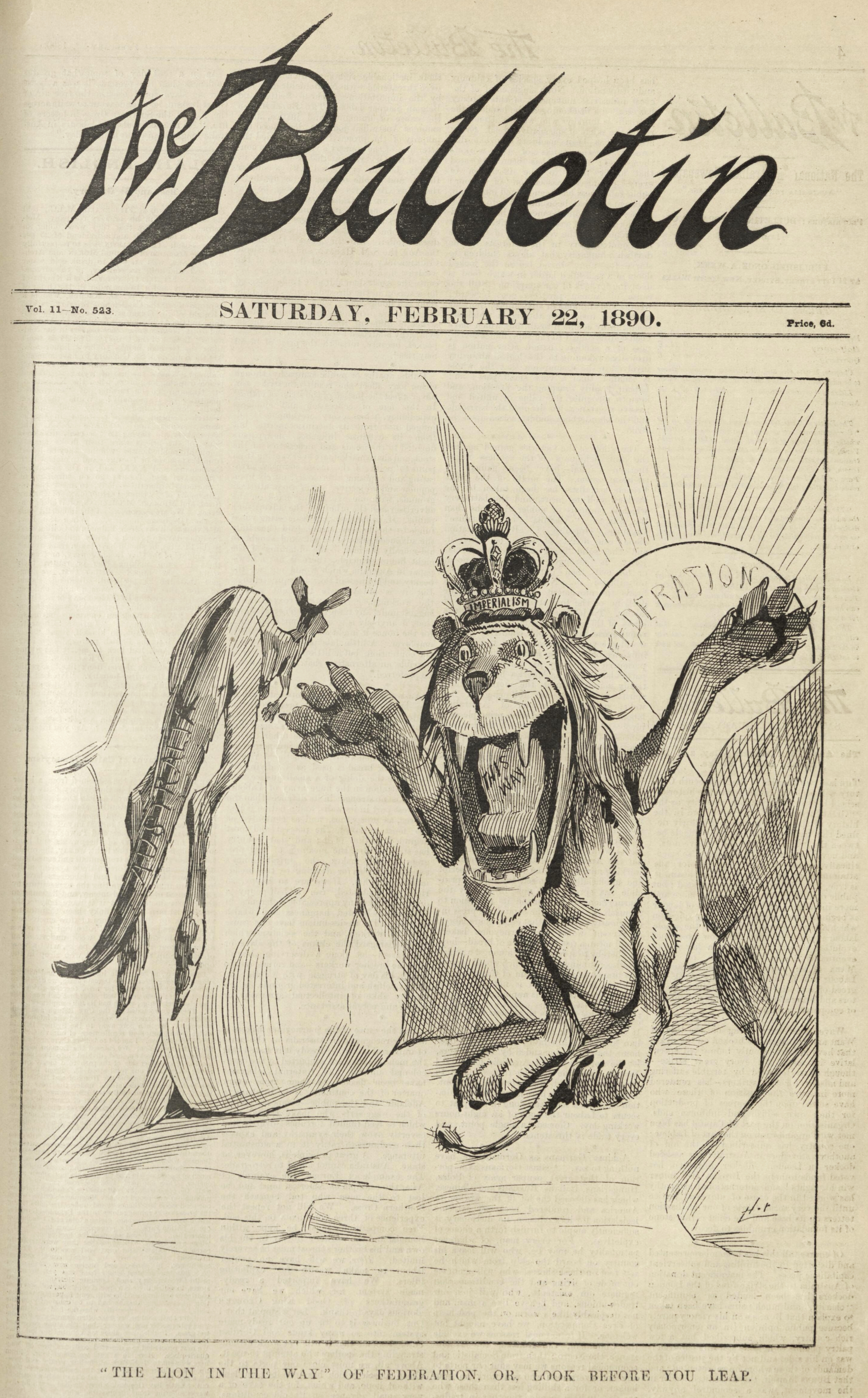

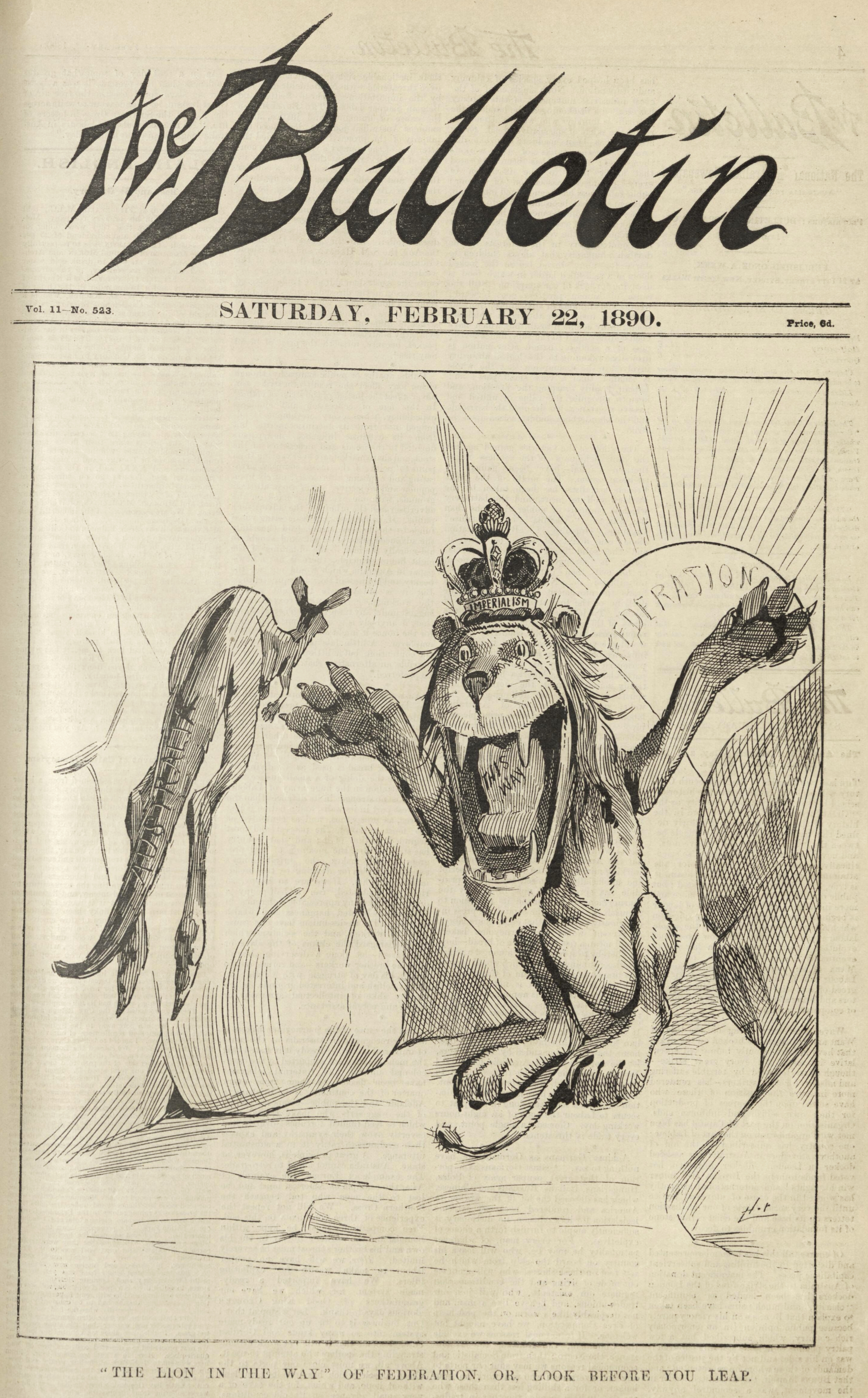

Federation and decline

At the Australian Federation Convention, which produced the first draft that was to become the

At the Australian Federation Convention, which produced the first draft that was to become the Australian Constitution

The Constitution of Australia (also known as the Commonwealth Constitution) is the fundamental law that governs the political structure of Australia. It is a written constitution, which establishes the country as a Federation of Australia, ...

in 1891, a former Premier of New South Wales, George Dibbs

Sir George Richard Dibbs KCMG (12 October 1834 – 5 August 1904) was an Australian politician who was Premier of New South Wales on three occasions.

Early years

Dibbs was born in Sydney, son of Captain John Dibbs, who 'disappeared' in the ...

, stated the "inevitable destiny of the people of this great country" would be the establishment of "the Republic of Australia". The fervour of republicanism tailed off in the 1890s as the labour movement became concerned with the Federation of Australia

The Federation of Australia was the process by which the six separate British self-governing colonies of Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania, South Australia (which also governed what is now the Northern Territory), and Wester ...

. The republican movement dwindled further during and after World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

as emotional and patriotic support for the war effort went hand in hand with a renewed sense of loyalty to the monarchy. '' The Bulletin'' abandoned republicanism and became a conservative, Empire loyalist paper. The Returned and Services League

The Returned and Services League of Australia, also known as RSL, RSL Australia and the RSLA, is an independent support organisation for people who have served or are serving in the Australian Defence Force.

History

The League was formed in ...

formed in 1916 and became an important bastion of monarchist sentiment.

The conservative parties were fervently monarchist and although the Labor Party campaigned for greater Australian independence within the Empire and generally supported the appointment of Australians as Governor-General

Governor-general (plural governors-general), or governor general (plural governors general), is the title of an official, most prominently associated with the British Empire. In the context of the governors-general and former British colonies, ...

, it did not question the monarchy itself. Under the Labor government of John Curtin

John Curtin (8 January 1885 – 5 July 1945) was an Australian politician who served as the 14th prime minister of Australia from 1941 until his death in 1945. He held office as the leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP), having been most ...

, a member of the Royal Family, Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester

Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester (Henry William Frederick Albert; 31 March 1900 – 10 June 1974) was a member of the British royal family. He was the third son of King George V and Mary of Teck, Queen Mary, and was a younger brother of kings E ...

, was appointed Governor-General during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. The royal tour of Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 19268 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until Death and state funeral of Elizabeth II, her death in 2022. ...

in 1954 saw a reported 7 million Australians (out of a total population of 9 million) out to see her.

The 1975 Australian constitutional crisis

The 1975 Australian constitutional crisis, also known simply as the Dismissal, culminated on 11 November 1975 with the dismissal from office of the Prime Minister of Australia, prime minister, Gough Whitlam of the Australian Labor Party (ALP), ...

, which culminated in the dismissal of Prime Minister Gough Whitlam

Edward Gough Whitlam (11 July 191621 October 2014) was the 21st prime minister of Australia, serving from December 1972 to November 1975. To date the longest-serving federal leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP), he was notable for being ...

by Governor-General John Kerr, raised questions about the value of maintaining a supposedly symbolic office that still possessed many key constitutional powers and what an Australian president with the same reserve powers would do in a similar situation.

Changes to oaths and titles

References to the monarchy were removed from various institutions through the late 1980s and 1990s. For example, in 1993, the Oath of Citizenship, which included an assertion of allegiance to the Australian monarch, was replaced by a pledge to be loyal to "Australia and its people". Earlier, in 1990, the formula of enactment for theParliament of Australia

The Parliament of Australia (officially the Parliament of the Commonwealth and also known as the Federal Parliament) is the federal legislature of Australia. It consists of three elements: the Monarchy of Australia, monarch of Australia (repr ...

was changed from "Be it enacted by the Queen, and the Senate, and the House of Representatives of the Commonwealth of Australia as follows" to "The Parliament of Australia enacts".

Barristers in New South Wales

New South Wales (commonly abbreviated as NSW) is a States and territories of Australia, state on the Eastern states of Australia, east coast of :Australia. It borders Queensland to the north, Victoria (state), Victoria to the south, and South ...

(from 1993), Queensland

Queensland ( , commonly abbreviated as Qld) is a States and territories of Australia, state in northeastern Australia, and is the second-largest and third-most populous state in Australia. It is bordered by the Northern Territory, South Austr ...

(from 1994), ACT (from 1995), Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Queen Victoria (1819–1901), Queen of the United Kingdom and Empress of India

* Victoria (state), a state of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, Canada, a provincial capital

* Victoria, Seychelles, the capi ...

(from 2000), Western Australia

Western Australia (WA) is the westernmost state of Australia. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to the south, the Northern Territory to the north-east, and South Australia to the south-east. Western Aust ...

(from 2001), Tasmania

Tasmania (; palawa kani: ''Lutruwita'') is an island States and territories of Australia, state of Australia. It is located to the south of the Mainland Australia, Australian mainland, and is separated from it by the Bass Strait. The sta ...

(from 2005), Northern Territory

The Northern Territory (abbreviated as NT; known formally as the Northern Territory of Australia and informally as the Territory) is an states and territories of Australia, Australian internal territory in the central and central-northern regi ...

(from 2007), Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the 15th century. Originally a phrase (the common-wealth ...

(from March 2007) and South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a States and territories of Australia, state in the southern central part of Australia. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories by area, which in ...

(from 2008) were no longer appointed Queen's Counsel

A King's Counsel (Post-nominal letters, post-nominal initials KC) is a senior lawyer appointed by the monarch (or their Viceroy, viceregal representative) of some Commonwealth realms as a "Counsel learned in the law". When the reigning monarc ...

(QC), but as Senior Counsel (SC). These changes were criticised by Justice Michael Kirby and other monarchists as moves to a "republic by stealth".A Republic by Stealth?, Robert Harris Oration, 12th Convention of the Royal Australasian College of Dental Surgeons, Canberra, 16 April 1994 However beginning with

Queensland

Queensland ( , commonly abbreviated as Qld) is a States and territories of Australia, state in northeastern Australia, and is the second-largest and third-most populous state in Australia. It is bordered by the Northern Territory, South Austr ...

in 2013, Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Queen Victoria (1819–1901), Queen of the United Kingdom and Empress of India

* Victoria (state), a state of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, Canada, a provincial capital

* Victoria, Seychelles, the capi ...

and the Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the 15th century. Originally a phrase (the common-wealth ...

in 2014 and followed by South Australia in 2020 the title of Queen's Counsel (QC) and now King's Counsel

A King's Counsel (Post-nominal letters, post-nominal initials KC) is a senior lawyer appointed by the monarch (or their Viceroy, viceregal representative) of some Commonwealth realms as a "Counsel learned in the law". When the reigning monarc ...

(KC) has again been conferred, in part due to the title's greater regard and recognition, internationally and domestically. There remains interest in New South Wales

New South Wales (commonly abbreviated as NSW) is a States and territories of Australia, state on the Eastern states of Australia, east coast of :Australia. It borders Queensland to the north, Victoria (state), Victoria to the south, and South ...

for a reintroduction of the title. In 2024, South Australia reverted back to only appointing SCs.

Keating government proposals

TheAustralian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party (ALP), also known as the Labor Party or simply Labor, is the major Centre-left politics, centre-left List of political parties in Australia, political party in Australia and one of two Major party, major parties in Po ...

(ALP) first made republicanism its official policy in 1991, with then Prime Minister Bob Hawke

Robert James Lee Hawke (9 December 1929 – 16 May 2019) was an Australian politician and trade unionist who served as the 23rd prime minister of Australia from 1983 to 1991. He held office as the Australian Labor Party, leader of the La ...

describing a republic as "inevitable". Following the ALP decision, the Australian Republican Movement

The Australian Republic Movement (ARM) is a Nonpartisanism, non-partisan organisation campaigning for Australia to become a republic. The ARM and its supporters have promoted various models, including a parliamentary republic, and the organisa ...

(ARM) was born. Hawke's successor, Paul Keating

Paul John Keating (born 18 January 1944) is an Australian former politician and trade unionist who served as the 24th prime minister of Australia from 1991 to 1996. He held office as the leader of the Labor Party (ALP), having previously ser ...

, pursued the republican agenda much more actively than Hawke and established the Republic Advisory Committee

The Republic Advisory Committee was a committee established by the then Australian Prime Minister Paul Keating in April 1993 to examine the constitutional and legal issues that would arise were Australia to become a republic. The committee's ma ...

to produce an options paper on issues relating to the possible transition to a republic to take effect on the centenary of Federation: 1 January 2001. The committee produced its report in April 1993 and in it argued that "a republic is achievable without threatening Australia's cherished democratic institutions".

In response to the report, Keating promised a referendum

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate (rather than their Representative democracy, representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either bin ...

on the establishment of a republic, replacing the Governor-General with a president, and removing references to the Australian sovereign. The president was to be nominated by the prime minister and appointed by a two-thirds majority in a joint sitting of the Senate and House of Representatives. The referendum was to be held either in 1998 or 1999. However, Keating's party lost the 1996 federal election in a landslide and he was replaced by John Howard, a monarchist, as prime minister.

1998 Constitutional Convention

With the change in government in 1996, Prime MinisterJohn Howard

John Winston Howard (born 26 July 1939) is an Australian former politician who served as the 25th prime minister of Australia from 1996 to 2007. He held office as leader of the Liberal Party of Australia. His eleven-year tenure as prime min ...

proceeded with an alternative policy of holding a constitutional convention. This was held over two weeks in February 1998 at Old Parliament House. Half of the 152 delegates were elected and half were appointed by the federal and state governments. Convention delegates were asked whether or not Australia should become a republic and which model for a republic is preferred. At the opening of the convention, Howard stated that if the convention could not decide on a model to be put to a referendum, then plebiscites would be held on the model preferred by the Australian public.

At the convention, a republic gained majority support (89 votes to 52 with 11 abstentions), but the question of what model for a republic should be put to the people at a referendum produced deep divisions among republicans.Vizard, Steve, Two Weeks in Lilliput: Bear Baiting and Backbiting At the Constitutional Convention (Penguin, 1998, ) Four republican models were debated: two involving direct election

Direct election is a system of choosing political officeholders in which the voters directly cast ballots for the persons or political party that they want to see elected. The method by which the winner or winners of a direct election are chosen ...

of the head of state; one involving appointment on the advice of the prime minister (the McGarvie Model); and one involving appointment by a two-thirds majority of parliament (the bi-partisan appointment model).

The latter was eventually successful at the convention, even though it only obtained a majority because of 22 abstentions in the final vote (57 against delegates voted against the model and 73 voted for, three votes short of an actual majority of delegates). A number of those who abstained were republicans who supported direct election (such as Ted Mack, Phil Cleary

Philip Ronald Cleary (born 8 December 1952) is an Australian political and sport commentator. He is a former Australian rules footballer who played 205 games at the Coburg Football Club, before serving as the member for Division of Wills, Wills ...

, Clem Jones

Clem Jones Order of Australia, AO (16 January 191815 December 2007), a surveyor by profession, was the longest serving Lord Mayor of Brisbane, Queensland, representing the Australian Labor Party (Queensland Branch), Labor Party from 1961 to 1975 ...

, and Andrew Gunter), thereby allowing the bi-partisan model to succeed. They reasoned that the model would be defeated at a referendum and a second referendum called with direct election as the model.

The convention also made recommendations about a preamble

A preamble () is an introductory and expressionary statement in a document that explains the document's purpose and underlying philosophy. When applied to the opening paragraphs of a statute, it may recite historical facts pertinent to the su ...

to the constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these pri ...

and a proposed preamble was also put to referendum.

According to critics, the two-week timeline and quasi-democratic composition of the convention is evidence of an attempt by John Howard to frustrate the republican cause, a claim John Howard adamantly rejects.

1999 Republican referendum

The republic referendum was held on 6 November 1999, after a national advertising campaign and the distribution of 12.9 million 'Yes/No' case pamphlets. It comprised two questions: The first asked whether Australia should become a republic in which the Governor-General and monarch would be replaced by one office, the President of the Commonwealth of Australia, the occupant elected by a two-thirds vote of the Australian parliament for a fixed term. The second question, generally deemed to be far less important politically, asked whether Australia should alter the constitution to insert apreamble

A preamble () is an introductory and expressionary statement in a document that explains the document's purpose and underlying philosophy. When applied to the opening paragraphs of a statute, it may recite historical facts pertinent to the su ...

. Neither of the amendments passed, with 55% of all electors and all states voting 'no' to the proposed amendment; it was not carried in any state. The preamble referendum question was also defeated, with a Yes vote of only 39 per cent.

Many opinions were put forward for the defeat, some relating to perceived difficulties with the parliamentary appointment model, others relating to the lack of public engagement or that most Australians were simply happy to keep the status quo. Some republicans voted no because they did not agree with provisions such as the president being instantly dismissible by the prime minister.

2000s: Following the referendum

On 26 June 2003, the Senate referred an inquiry into an Australian republic to the Senate Legal and Constitutional References Committee. During 2004, the committee reviewed 730 submissions and conductedhearings

In law, a hearing is the formal examination of a case (civil or criminal) before a judge. It is a proceeding before a court or other decision-making body or officer, such as a government agency or a legislative committee.

Description

A hearing ...

in all state capitals. The committee tabled its report, called ''Road to a Republic'', on 31 August 2004. The report examined the contest between minimalist and direct-election models and gave attention to hybrid models such as the electoral college model, the constitutional council model, and models having both an elected president and a Governor-General.

The bi-partisan recommendations of committee supported educational initiatives and holding a series of plebiscites to allow the public to choose which model they preferred, prior to a final draft and referendum, along the lines of plebiscites proposed by John Howard at the 1998 constitutional convention.

Issues related to republicanism were raised by the March 2006 tour of Australia by Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 19268 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until Death and state funeral of Elizabeth II, her death in 2022. ...

. John Howard, still serving as prime minister, was then questioned by British journalists about the future of the Australian monarchy and there was debate about playing Australia's royal anthem, "God Save the Queen

"God Save the King" ("God Save the Queen" when the monarch is female) is '' de facto'' the national anthem of the United Kingdom. It is one of two national anthems of New Zealand and the royal anthem of the Isle of Man, Australia, Canada and ...

", during the opening of that year's Commonwealth Games, at which the monarch was present.

In July 2007, Opposition Leader Kevin Rudd

Kevin Michael Rudd (born 21 September 1957) is an Australian diplomat and former politician who served as the 26th prime minister of Australia from 2007 to 2010 and June to September 2013. He held office as the Leaders of the Australian Labo ...

pledged to hold a new referendum on a republic if called on to form a government. However, he stated there was no fixed time frame for such a move and that the result of the 1999 referendum must be respected. After his party won the 2007 federal election and Rudd was appointed prime minister, he stated in April 2008 that a move to a republic was "not a top-order priority".

In the lead-up to the 2010 federal election, Prime Minister Julia Gillard

Julia Eileen Gillard (born 29 September 1961) is an Australian former politician who served as the 27th prime minister of Australia from 2010 to 2013. She held office as the leader of the Labor Party (ALP), having previously served as the ...

stated: "I believe that this nation should be a republic. I also believe that this nation has got a deep affection for Queen Elizabeth." She stated her belief that it would be appropriate for Australia to become a republic only once Queen Elizabeth II's reign ends.

2010s

In November 2013, Governor-GeneralQuentin Bryce

Dame Quentin Alice Louise Bryce, (née Strachan; born 23 December 1942) is an Australian academic who served as the 25th Governor-General of Australia from 2008 to 2014. She is the List of elected and appointed female heads of state, first wom ...

proclaimed her support for an Australian republic, stating in a speech "perhaps, my friends, one day, one young girl or boy may even grow up to be our nation's first head of state". She had previously emphasised the importance of debate about the future of the Australian head of state and the evolution of the constitution.

In January 2015, Opposition Leader Bill Shorten

William Richard Shorten (born 12 May 1967) is an Australian former politician and trade unionist. He was the leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) and Leader of the Opposition (Australia), Leader of the Opposition from 2013 to 2019. He also ...

called for a new push for a republic, stating: "Let us declare that our head of state should be one of us. Let us rally behind an Australian republic - a model that truly speaks for who we are, our modern identity, our place in our region and our world."

In September 2015, former ARM

In human anatomy, the arm refers to the upper limb in common usage, although academically the term specifically means the upper arm between the glenohumeral joint (shoulder joint) and the elbow joint. The distal part of the upper limb between ...

chair Malcolm Turnbull

Malcolm Bligh Turnbull (born 24 October 1954) is an Australian former politician and businessman who served as the 29th prime minister of Australia from 2015 to 2018. He held office as Liberal Party of Australia, leader of the Liberal Party an ...

became leader of the Liberal Party and was appointed prime minister. He stated he would not pursue "his dream" of Australia becoming a republic until after the end of the Queen's reign, instead focusing his efforts toward the economy. Upon meeting Elizabeth II in July 2017, Turnbull declared himself an "Elizabethan" and stated he did not believe a majority of Australians would support a republic before the end of her reign.

In December 2016, News.com.au

News.com.au (stylised in all lowercase) is an Australian website owned by News Corp Australia. It had 9.6 million unique readers in April 2019 and covers national and international news, lifestyle, travel, entertainment, technology, finance an ...

found that a slim majority of members of both houses of parliament supported Australia becoming a republic (54% in the House and 53% in the Senate).

In July 2017, Opposition Leader Bill Shorten revealed that, should the Labor Party be elected in the 2019 federal election, they would legislate for a compulsory plebiscite on the issue. Should that plebiscite be supported by a majority of Australians, a second vote would be held, this time a referendum, asking the public for their support for a specific model of government. Labor lost the election.

2020s

Following Labor's victory in the 2022 federal election, the new Prime Minister,Anthony Albanese

Anthony Norman Albanese ( or ; born 2 March 1963) is an Australian politician serving as the 31st and current prime minister of Australia since 2022. He has been the Leaders of the Australian Labor Party#Leader, leader of the Labor Party si ...

, appointed Matt Thistlethwaite

Matthew James Thistlethwaite (born 6 September 1972) is an Australian politician. He has been an Australian Labor Party member of the Australian House of Representatives since 2013, representing the electorate of Division of Kingsford Smith, Kin ...

as the Assistant Minister for the Republic, signalling a commitment to prepare Australia for a transition to republic following the next election. After the death of Elizabeth II, former prime minister Julia Gillard

Julia Eileen Gillard (born 29 September 1961) is an Australian former politician who served as the 27th prime minister of Australia from 2010 to 2013. She held office as the leader of the Labor Party (ALP), having previously served as the ...

opined that Australia would inevitably choose to be a republic, but agreed with Albanese's timing on debate about the matter. When asked if he supported another referendum following the Queen's death, Albanese stated it was "not the time" to discuss a republic. Instead the government had focused on the referendum to enshrine an Indigenous Voice to Parliament

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice, also known as the Indigenous Voice to Parliament, the First Nations Voice or simply the Voice, was a proposed Australian federal advisory body to comprise Aboriginal Australians, Aboriginal a ...

, which has been described by the assistant minister as a "critical first step" before a vote possibly some time in 2026. The Prime Minister Anthony Albanese had stated: "I couldn't envisage a circumstance where we changed our head of state to an Australian head of state but still didn't recognise First Nations people in our constitution."

After the Voice referendum

The 2023 Australian Indigenous Voice referendum was a constitutional referendum held on 14October 2023 in which the proposed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice was rejected. Voters were asked to approve an alteration to the Australia ...

failed, the government began to prioritise immediate economic policy over constitutional reforms, leading to concern from some republican leaders that a chance to hold another referendum would be delayed for a generation. In January 2024, the Labor government confirmed that a referendum was no longer a priority, however a break with the monarchy was still long-term party policy.

On 28 July 2024, the position of assistant minister for the republic, which was first established on 1 June 2022, was abolished in a ministerial reshuffle.

On 13 May 2025, following the Coalition's defeat at the 2025 federal election, Sussan Ley

Sussan Penelope Ley (pron. , "Susan Lee"; ; born 14 December 1961) is an Australian politician who is the current Leader of the Opposition (Australia), Leader of the Opposition and Leader of the Liberal Party of Australia, leader of the Liberal ...

and Ted O'Brien were elected as leader and deputy leader of the Liberal Party, respectively. Ley has previously declared her support for a republic, while O'Brien served as Chair of the Australian Republic Movement between 2005 and 2007.

Arguments for change

Independence and head of state

A central argument made by Australian republicans is that, as Australia is an independent country, it is inappropriate and anomalous for Australia to share the person of its monarch with the United Kingdom. Republicans argue that the Australian monarch is not Australian and, as a national and resident of another country, cannot adequately represent Australia or Australian national aspirations, either to itself or to the rest of the world. Former Chief JusticeGerard Brennan

Sir Francis Gerard Brennan (22 May 1928 – 1 June 2022) was an Australian lawyer and jurist who served as the 10th Chief Justice of Australia. As a judge in the High Court of Australia, he wrote the lead judgement on the Mabo decision, which ...

stated that "so long as we retain the existing system our head of state is determined for us essentially by the parliament at Westminster". As ARM member Frank Cassidy put it in a speech on the issue: "In short, we want a resident for President."

Multiculturalism

Some republicans associate the monarchy with British identity and argue that Australia has changed demographically and culturally, from being "British to our bootstraps", as prime ministerSir Robert Menzies

''Sir'' is a formal honorific address in English for men, derived from Sire in the High Middle Ages. Both are derived from the old French "" (Lord), brought to England by the French-speaking Normans, and which now exist in French only as part ...

once put it, to being less British in nature (albeit maintaining an "English Core"). Many Australian republicans are of non-British ancestry, and feel no connection to the "mother country" to speak of. According to an Australian government inquiry, arguments put forth by these republicans include the claim that the idea of one person being both monarch of Australia and of the United Kingdom is an anomaly.

However, monarchists argue that immigrants who left unstable republics and have arrived in Australia since 1945 welcomed the social and political stability that they found in Australia under a constitutional monarchy. Further, some Aboriginal Australians, such as former Senator Neville Bonner

Neville Thomas Bonner AO (28 March 19225 February 1999) was an Australian politician, and the first Aboriginal Australian to become a member of the Parliament of Australia. He was appointed by the Queensland Parliament to fill a casual vacancy ...

, said a republican president would not "care one jot more for my people".

Social values and contemporary Australia

From some perspectives, it has been argued that several characteristics of the monarchy are in conflict with modern Australian values. The hereditary nature of the monarchy is said to conflict withegalitarianism

Egalitarianism (; also equalitarianism) is a school of thought within political philosophy that builds on the concept of social equality, prioritizing it for all people. Egalitarian doctrines are generally characterized by the idea that all hum ...

and dislike of inherited privilege. The laws of succession were, before amendment to them in 2015, held by some to be sexist

Sexism is prejudice or discrimination based on one's sex or gender. Sexism can affect anyone, but primarily affects women and girls. It has been linked to gender roles and stereotypes, and may include the belief that one sex or gender is int ...

and the links between the monarchy and the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

inconsistent with Australia's secular

Secularity, also the secular or secularness (from Latin , or or ), is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. The origins of secularity can be traced to the Bible itself. The concept was fleshed out through Christian hi ...

character.

Sectarianian divides

Under theAct of Settlement

The Act of Settlement ( 12 & 13 Will. 3. c. 2) is an act of the Parliament of England that settled the succession to the English and Irish crowns to only Protestants, which passed in 1701. More specifically, anyone who became a Roman Cathol ...

, the monarch is prohibited from being a Catholic. Monarchism and republicanism in Australia have been claimed to delineate historical and persistent sectarian

Sectarianism is a debated concept. Some scholars and journalists define it as pre-existing fixed communal categories in society, and use it to explain political, cultural, or religious conflicts between groups. Others conceive of sectarianism a ...

tensions with, broadly speaking, Catholics

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

more likely to be republicans and Protestants

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

more likely to be monarchists.Knightley, Philip. Australia: A Biography of a Nation. London: Vintage (2001). This developed out of a historical cleavage in 19th- and 20th-century Australia, in which republicans were predominantly of Irish Catholic background and loyalists

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cr ...

were predominantly of British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

Protestant background. Whilst mass immigration since the Second World War has diluted this conflict, the Catholic–Protestant divide has been cited as a dynamic in the republic debate, particularly in relation to the referendum

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate (rather than their Representative democracy, representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either bin ...

campaign in 1999. Nonetheless, others have stated that Catholic–Protestant tensions—at least in the sense of an Irish–British conflict—are at least forty years dead.

It has also been claimed, however, that the Catholic–Protestant divide is intermingled with class issues. Republicanism in Australia has traditionally been supported most strongly by members of the urban working class with Irish Catholic backgrounds, whereas monarchism is a core value associated with urban and rural inhabitants of British Protestant heritage and the middle class, to the extent that there were calls in 1999 for 300,000 exceptionally enfranchised British subjects who were not Australian citizens to be barred from voting on the grounds that they would vote as a loyalist bloc in a tight referendum.

Proposals for change

A typical proposal for an Australian republic provides for the King and Governor-General to be replaced by a president or an executive federal council. There is much debate on the appointment or election process that would be used and what role such an office would have.Australians for Constitutional Monarchy

Australians for Constitutional Monarchy (ACM) is a group that aims to preserve Australia's constitutional monarchy, with Charles III as King of Australia. The group states that it is a non-partisan, not-for-profit organisation whose role is "To ...

and the Australian Monarchist League

The Australian Monarchist League (AML) is a voluntary association that advocates for the retention of Australia's constitutional monarchy. The organisation supported the "No" vote in the 1999 republic referendum, which asked citizens whether t ...

argue that no model is better than the present system and argue that the risk and difficulty of changing the constitution is best demonstrated by inability of republicans to back a definitive design.

The range of models

Australian republicans usually propose that theGovernor-General

Governor-general (plural governors-general), or governor general (plural governors general), is the title of an official, most prominently associated with the British Empire. In the context of the governors-general and former British colonies, ...

is replaced by an Australian Head of State

A head of state is the public persona of a sovereign state.#Foakes, Foakes, pp. 110–11 "

. They have proposed or shown support for a variety of methods for selecting and/or electing such a Head of State as follows:

*Election

**by a he head of state

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (letter), the fifth letter of the Semitic abjads

* He (pronoun), a pronoun in Modern English

* He (kana), one of the Japanese kana (へ in hiragana and ヘ in katakana)

* Ge (Cyrillic), a Cyrillic letter cal ...

being an embodiment of the State itself or representative of its international persona." The name given to the office of head of sta ...popular vote

Popularity or social status is the quality of being well liked, admired or well known to a particular group.

Popular may also refer to:

In sociology

* Popular culture

* Popular fiction

* Popular music

* Popular science

* Populace, the tota ...

of all Australian citizens;

**by the federal parliament

The Parliament of Australia (officially the Parliament of the Commonwealth and also known as the Federal Parliament) is the federal legislature of Australia. It consists of three elements: the monarch of Australia (represented by the governor ...

alone;

**by federal and state parliaments;

**by a hybrid process of popular and parliamentary votes.

* Selection

**by the prime minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

;

**by consensus among the government and opposition;

**by an electoral college.

Alternatively, some proposals provide for replacing only the monarchy and entirely retaining the role of Governor-General. The McGarvie model replaces the monarch with a constitutional council of former governors and judges. Copernican models replace the monarch with a directly elected figurehead, without executive authority. These models maintain the executive authority and reserve powers of the current Governor-General, appointed by the council or elected figurehead respectively.

Occasionally, it is proposed to abolish the roles of the Governor-General and the monarchy and have their functions exercised by other constitutional officers such as the speaker

Speaker most commonly refers to:

* Speaker, a person who produces speech

* Loudspeaker, a device that produces sound

** Computer speakers

Speaker, Speakers, or The Speaker may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* "Speaker" (song), by David ...

.

2022 Australian Choice Model

Since 2022, theARM

In human anatomy, the arm refers to the upper limb in common usage, although academically the term specifically means the upper arm between the glenohumeral joint (shoulder joint) and the elbow joint. The distal part of the upper limb between ...

has supported the Australian Choice Model, which they developed after consultation with more than 10,000 Australians. Originating in a 2004 Senate submission and 2018 book, the current model proposes that state, territory and Federal parliaments nominate eleven candidates which are then put to a national vote. The model aims to bridge a longstanding controversy of whether the parliament or people should elect a head of state.

The model includes specific constitutional amendments drafted and supported by ten constitutional law scholars. The proposed amendments codify the reserve powers of the Head of State with some variance from how they are exercised presently. The ARM claims that their research shows that their approach has significantly higher levels of support in the Australian community than direct election or parliamentary appointment models and would have the best prospects of success at a referendum.

Process models

From its foundation until the1999 referendum

The Australian republic referendum held on 6 November 1999 was a two-question referendum to amend the Constitution of Australia. The first question asked whether Australia should become a republic, under a bi-partisan appointment model where ...

, the ARM supported the bi-partisan appointment model, which would result in a President elected by the Parliament of Australia

The Parliament of Australia (officially the Parliament of the Commonwealth and also known as the Federal Parliament) is the federal legislature of Australia. It consists of three elements: the Monarchy of Australia, monarch of Australia (repr ...

, with the powers currently held by the Governor-General. It is argued that the requirement of a two-thirds majority in a vote of both houses of parliament would result in a bi-partisan appointment, preventing a party politician from becoming president.

From 2010 to 2022, the ARM proposed a non-binding plebiscite to decide the model, followed by a binding referendum to amend the Constitution, reflecting the model chosen. Opponents of holding non-binding plebiscites include monarchist David Flint

David Edward Flint (born 1938) is an Australian legal academic, known for his leadership of Australians for Constitutional Monarchy and for his tenure as head of the Australian Broadcasting Authority.

Early life and education

David Flint was ...

, who described this process as "inviting a vote of no confidence in one of the most successful constitutions in the world," and minimalist republican Greg Craven, who states "a multi-option plebiscite inevitably will produce a direct election model, precisely for the reason that such a process favours models with shallow surface appeal and multiple flaws. Equally inevitably, such a model would be doomed at referendum."

Public opinion

Polls and surveys generate different responses depending on the wording of the questions, mostly in regards the type of republic, and often appear contradictory. In 2009, the Australian Electoral Survey that is conducted following all elections by theAustralian National University

The Australian National University (ANU) is a public university, public research university and member of the Group of Eight (Australian universities), Group of Eight, located in Canberra, the capital of Australia. Its main campus in Acton, A ...

has found that support for a republic has remained reasonably static since 1987 at around 60%, if the type of republic is not part of the question. The survey also shows that support or opposition is relatively weak: 31% strongly support a republic while only 10% strongly oppose. Roy Morgan

Roy Morgan, formerly known as Roy Morgan Research, is an independent Australian social and political market research and public opinion statistics company headquartered in Melbourne, Victoria. It operates nationally as Roy Morgan and internatio ...

research has indicated that support for the monarchy has been supported by a majority of Australians since 2010, with support for a republic being in the majority between 1999 and 2004.

An opinion poll held in November 2008 that separated the questions found support for a republic at 50% with 28% opposed. Asked how the president should be chosen if there were to be a republic, 80 percent said elected by the people, against 12 percent who favoured appointment by parliament. In October 2009, another poll by UMR found 59% support for a republic and 33% opposition. 73% supported direct election, versus 18% support for parliamentary appointment.

On 29 August 2010, ''The Sydney Morning Herald

''The Sydney Morning Herald'' (''SMH'') is a daily Tabloid (newspaper format), tabloid newspaper published in Sydney, Australia, and owned by Nine Entertainment. Founded in 1831 as the ''Sydney Herald'', the ''Herald'' is the oldest continuous ...

'' published a poll produced by Neilson, asking multiple questions on the future of the monarchy:

*48% of the 1400 respondents were opposed to constitutional change (a rise of 8 per cent since 2008)

*44% supported change (a drop of 8 per cent since 2008).

But when asked which of the following statements best described their view:

*31% said Australia should never become a republic.

*29% said Australia should become a republic as soon as possible.

*34% said Australia should become a republic only after Queen Elizabeth II's reign ends.

A survey of 1,000 readers of ''The Sun-Herald

''The Sun-Herald'' is an Australian newspaper published in tabloid or compact format on Sundays in Sydney by Nine Entertainment. It is the Sunday counterpart of the ''Sydney Morning Herald''. In the six months to September 2005, ''The Sun-H ...

'' and ''The Sydney Morning Herald'', published in ''The Sydney Morning Herald'' on 21 November 2010, found 68% of respondents were in favour of Australia becoming a republic, while 25% said it should not. More than half the respondents, 56%, said Australia should become a republic as soon as possible while 31% said it should happen after the Queen dies.

However, an opinion poll conducted in 2011 saw a sharp decline in the support for an Australian republic. The polling conducted by the Morgan Poll

Roy Morgan, formerly known as Roy Morgan Research, is an independent Australian social and political market research and public opinion statistics company headquartered in Melbourne, Victoria. It operates nationally as Roy Morgan and internation ...

in May 2011 showed the support for the monarchy was now 55% (up 17% since 1999), whereas the support for a republic was at 34% (down 20%). The turnaround in support for a republic has been called the "strange death of Australian republicanism".

The Australian Broadcasting Corporation

The Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) is Australia’s principal public service broadcaster. It is funded primarily by grants from the federal government and is administered by a government-appointed board of directors. The ABC is ...

's ''Vote Compass'' during the 2013 Australian federal election

The 2013 Australian federal election to elect the members of the 44th Parliament of Australia took place on Saturday, 7 September 2013. The centre-right Coalition (Australia), Liberal/National Coalition Opposition (Australia), opposition led by ...

found that 40.4% of respondents disagreed with the statement ''"Australia should end the monarchy and become a republic"'', whilst 38.1% agreed (23.1% strongly agreed) and 21.5% were neutral. Support for a republic was highest among those with a left-leaning political ideology. Younger people had the highest rate for those neutral towards the statement (27.8%) with their support for strongly agreed the lowest of all age groups at 17.1%. Support for a republic was highest in the Australian Capital Territory

The Australian Capital Territory (ACT), known as the Federal Capital Territory until 1938, is an internal States and territories of Australia, territory of Australia. Canberra, the capital city of Australia, is situated within the territory, an ...

and Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Queen Victoria (1819–1901), Queen of the United Kingdom and Empress of India

* Victoria (state), a state of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, Canada, a provincial capital

* Victoria, Seychelles, the capi ...

and lowest in Queensland

Queensland ( , commonly abbreviated as Qld) is a States and territories of Australia, state in northeastern Australia, and is the second-largest and third-most populous state in Australia. It is bordered by the Northern Territory, South Austr ...

and Western Australia. More men than women said they support a republic.

In early 2014, a ReachTEL poll of 2,146 Australian conducted just after Australia Day

Australia Day is the official national day of Australia. Observed annually on 26 January, it marks the 1788 landing of the First Fleet and raising of the Flag of Great Britain, Union Flag of Great Britain by Arthur Phillip at Sydney Cove, a ...

showed only 39.4% supported a republic with 41.6% opposed. Lowest support was in the 65+ year cohort followed by the 18–34-year cohort. ARM chair Geoff Gallop

Geoffrey Ian Gallop (born 27 September 1951) is an Australian academic and former politician who served as the 27th premier of Western Australia from 2001 to 2006. He is currently a professor and director of the Graduate School of Government at ...

said higher support for a republic among Generation X and baby boomer voters could be explained by them having participated in the 1999 referendum and remembering the 1975 constitutional crisis.

In April 2014, a poll found that "support for an Australian republic has slumped to its lowest level in more than three decades"; namely, on the eve of the visit to Australia by the Duke

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of Royal family, royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and above sovereign princes. As royalty or nobi ...

and Duchess of Cambridge

Duke of Cambridge is a hereditary title of nobility in the British royal family, one of several royal dukedoms in the United Kingdom. The title is named after the city of Cambridge in England. It is heritable by male descendants by primogeni ...

, and Prince George, 42% of those polled agreed with the statement that "Australia should become a republic", whereas 51% opposed.

ARM commissioned a poll to be conducted by Essential Research from 5 to 8 November in 2015, asking "When Prince Charles becomes King of Australia, will you support or oppose replacing the British monarch with an Australian citizen as Australia's head of state?" Of the 1008 participants, 51% said they would prefer an Australian head of state to "King Charles", 27% opposed and 22% were undecided.

The Australian

''The Australian'', with its Saturday edition ''The Weekend Australian'', is a broadsheet daily newspaper published by News Corp Australia since 14 July 1964. As the only Australian daily newspaper distributed nationally, its readership of b ...

has polled the same question "Are you personally in favour or against Australia becoming a republic?" multiple times since 1999. After Australia Day

Australia Day is the official national day of Australia. Observed annually on 26 January, it marks the 1788 landing of the First Fleet and raising of the Flag of Great Britain, Union Flag of Great Britain by Arthur Phillip at Sydney Cove, a ...

2016 they found 51% support. This level of support was similar to levels found between 1999 and 2003 by the same newspaper. Total against was 37% which was an increase over the rates polled in all previous polls other than 2011. Uncommitted at 12% was the lowest ever polled. However support for a republic was again lowest in the 18–34-year cohort.

In November 2018, Newspoll

Newspoll is an Australian opinion polling brand, published by ''The Australian'' and administered by Australian polling firm Pyxis Polling & Insights. Pyxis is founded by the team led by Dr Campbell White, who redesigned Newspoll's methodology ...

found support for a republic had collapsed to 40%. It was also the first time in their polling since the 1999 referendum

The Australian republic referendum held on 6 November 1999 was a two-question referendum to amend the Constitution of Australia. The first question asked whether Australia should become a republic, under a bi-partisan appointment model where ...

that support for the monarchy was higher than a republic. A July 2020 YouGov poll found 62% of Australians believed Australia's head of state should be an Australian, not Queen Elizabeth II. An Ipsos poll in January 2021 found support for a republic was 34%, the lowest since 1979. However, one conducted by Ipsos in December 2022 (after the death of the Queen) showed support for the republic had risen to 54% (see above reference.)

In October 2024, an opinion poll

conducted by Roy Morgan

Roy Morgan, formerly known as Roy Morgan Research, is an independent Australian social and political market research and public opinion statistics company headquartered in Melbourne, Victoria. It operates nationally as Roy Morgan and internatio ...

, shortly after the King and Queen’s royal tour, showed a dramatic increase in support for the monarchy, with 57 per cent of respondents believing Australia should remain a monarchy.

Party political positions

Political party summary

Republicanism has a level support in all major political parties. Most parties take a stance on this issue and have developed or implemented policy accordingly. The various positions are as follows:Liberal–National Coalition

TheLiberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world.

The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left. For example, while the political systems ...

espouses both conservative and classically liberal

Classical liberalism is a political tradition and a branch of liberalism that advocates free market and laissez-faire economics and civil liberties under the rule of law, with special emphasis on individual autonomy, limited government, econ ...

positions. It has no official position on the issue of monarchy, but both republicans and monarchists have held prominent positions within the party.

Proponents of republicanism in the Liberal Party include former prime minister and ARM

In human anatomy, the arm refers to the upper limb in common usage, although academically the term specifically means the upper arm between the glenohumeral joint (shoulder joint) and the elbow joint. The distal part of the upper limb between ...

leader Malcolm Turnbull

Malcolm Bligh Turnbull (born 24 October 1954) is an Australian former politician and businessman who served as the 29th prime minister of Australia from 2015 to 2018. He held office as Liberal Party of Australia, leader of the Liberal Party an ...

, former prime minister Malcolm Fraser

John Malcolm Fraser (; 21 May 1930 – 20 March 2015) was an Australian politician who served as the 22nd prime minister of Australia from 1975 to 1983. He held office as the leader of the Liberal Party of Australia, and is the fourth List of ...

, former opposition leader John Hewson

John Robert Hewson AM (born 28 October 1946) is an Australian former politician who served as leader of the Liberal Party from 1990 to 1994. He led the Liberal-National Coalition to defeat at the 1993 Australian federal election.

Hewson w ...

, former premiers Gladys Berejiklian

Gladys Berejiklian (; born 22 September 1970) is an Australian businesswoman and former politician who served as the 45th premier of New South Wales and the leader of the New South Wales division of the Liberal Party from 2017 to 2021. Berejikl ...

(of NSW), Mike Baird

Michael Bruce Baird (born 1 April 1968) is an Australian investment banker and former politician who was the 44th Premier of New South Wales, the Minister for Infrastructure, the Minister for Jobs, Investment, Tourism and Western Sydney, Mini ...

(of NSW) and Jeff Kennett

Jeffrey Gibb Kennett (born 2 March 1948) is an Australian former politician who served as the 43rd Premier of Victoria between 1992 and 1999, Leader of the Victorian Liberal Party from 1982 to 1989 and from 1991 to 1999, and the Member for ...

(of Victoria), former deputy leader Julie Bishop

Julie Isabel Bishop (born 17 July 1956) is an Australian former politician who served as Minister for Foreign Affairs (Australia), Minister for Foreign Affairs from 2013 to 2018 and Leader of the Liberal Party of Australia#Federal deputy leader ...

, and former federal treasurers Joe Hockey

Joseph Benedict Hockey (born 2 August 1965) is an Australian former politician and diplomat. He was the Member of Parliament for Division of North Sydney, North Sydney from 1996 Australian federal election, 1996 until 2015. He was the Treasurer ...

and Peter Costello

Peter Howard Costello (born 14 August 1957) is an Australian businessman, lawyer and former politician who served as the treasurer of Australia in Howard government, government of John Howard from 1996 to 2007. He is the longest-serving trea ...

.

Supporters of the status quo include former prime ministers Robert Menzies

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' () "fame, glory, honour, praise, reno ...

, Scott Morrison

Scott John Morrison (born 13 May 1968) is an Australian former politician who served as the 30th prime minister of Australia from 2018 to 2022. He held office as leader of the Liberal Party of Australia, leader of the Liberal Party and was ...

, Tony Abbott

Anthony John Abbott (; born 4 November 1957) is an Australian former politician who served as the 28th prime minister of Australia from 2013 to 2015. He held office as the leader of the Liberal Party of Australia and was the member of parli ...

(who led Australians for Constitutional Monarchy

Australians for Constitutional Monarchy (ACM) is a group that aims to preserve Australia's constitutional monarchy, with Charles III as King of Australia. The group states that it is a non-partisan, not-for-profit organisation whose role is "To ...

from 1992 to 1994), John Howard

John Winston Howard (born 26 July 1939) is an Australian former politician who served as the 25th prime minister of Australia from 1996 to 2007. He held office as leader of the Liberal Party of Australia. His eleven-year tenure as prime min ...

(whose government oversaw the 1999 referendum

The Australian republic referendum held on 6 November 1999 was a two-question referendum to amend the Constitution of Australia. The first question asked whether Australia should become a republic, under a bi-partisan appointment model where ...

) and former opposition leaders Peter Dutton

Peter Craig Dutton (born 18 November 1970) is an Australian former politician who served as the Leader of the Opposition (Australia), Leader of the Opposition and the Leader of the Liberal Party of Australia, leader of the Liberal Party from 2 ...

, Alexander Downer

Alexander John Gosse Downer (born 9 September 1951) is an Australian former politician and diplomat who was leader of the Liberal Party from 1994 to 1995, Minister for Foreign Affairs from 1996 to 2007, and High Commissioner to the United Ki ...

and Brendan Nelson

Brendan John Nelson (born 19 August 1958) is an Australian business leader, physician and former politician. He served as the federal Leader of the Opposition from 2007 to 2008, going on to serve as Australia's senior diplomat to the European ...

.

The National Party National Party or Nationalist Party may refer to:

Active parties

* National Party of Australia, commonly known as ''The Nationals''

* Bangladesh:

** Bangladesh Nationalist Party

** Jatiya Party (Ershad) a.k.a. ''National Party (Ershad)''

* Californ ...

officially supports the status quo, but there have been some republicans within the party, such as former leader Tim Fischer

Timothy Andrew Fischer (3 May 1946 – 22 August 2019) was an Australian politician and diplomat who served as leader of the National Party of Australia, National Party from 1990 to 1999. He was the tenth Deputy Prime Minister of Australia, d ...

. The Country Liberal Party

The Country Liberal Party of the Northern Territory (CLP), commonly known as the Country Liberals, is a centre-right and conservative political party in Australia's Northern Territory. In territory politics, it operates in a two-party system wi ...

also supports the status quo, but some republicans have been members of the party, including former leader Gary Higgins

Gary John Higgins (born 26 May 1954) is an Australian former politician. A member of the Country Liberal Party, he was elected to represent the seat of Daly in the Northern Territory Legislative Assembly at the 2012 election. After the 2016 e ...

.

Under then prime minister John Howard, a monarchist, the government initiated a process

A process is a series or set of activities that interact to produce a result; it may occur once-only or be recurrent or periodic.

Things called a process include:

Business and management

* Business process, activities that produce a specific s ...

to settle the republican debate, involving a constitutional convention and a referendum. Howard says the matter was resolved by the failure of the referendum.

Australian Labor Party

The Labor Party has supported constitutional change to become a republic since 1991 and has incorporated republicanism into its platform. Labor has proposed a series ofplebiscite

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a direct vote by the electorate (rather than their representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either binding (resulting in the adoption of a new policy) or adv ...

s to restart the republican process

A process is a series or set of activities that interact to produce a result; it may occur once-only or be recurrent or periodic.

Things called a process include:

Business and management

* Business process, activities that produce a specific s ...

. Along with this, Labor spokesperson (and former federal attorney general) Nicola Roxon

Nicola Louise Roxon (born 1 April 1967) is an Australian former politician. After politics, she has worked as a company director and academic.

Roxon represented the lower house seat of Gellibrand in Victoria for the Australian Labor Party; ...

has previously said that reform will "always fail if we seek to inflict a certain option on the public without their involvement. This time round, the people must shape the debate". In the 2019 federal election, Labor's platform included a two-stage referendum on a republic to be held during the next parliamentary term; however, Labor was defeated in the election.

Australian Greens

TheAustralian Greens

The Australian Greens, commonly referred to simply as the Greens, are a Left-wing politics, left-wing green party, green Australian List of political parties in Australia, political party. As of 2025, the Greens are the third largest politica ...

are a strong proponent for an Australian republic, and this is reflected in the Greens "Constitutional Reform & Democracy" policy. In 2009, the Greens proposed legislation to hold a plebiscite

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a direct vote by the electorate (rather than their representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either binding (resulting in the adoption of a new policy) or adv ...

on a republic at the 2010 federal election. The bill was subject to a Senate inquiry, which made no recommendation on the subject, and the proposal was subsequently dropped.

Democrats

TheAustralian Democrats

The Australian Democrats is a centrist political party in Australia. Founded in 1977 from a merger of the Australia Party and the New Liberal Movement, both of which were descended from Liberal Party splinter groups, it was Australia's lar ...

, Australia's third party from the 1970s until the 2000s, strongly supported a move towards a republic through a system of an elected head of state through popular voting.

Notable supporters

*Thomas Keneally

Thomas Michael Keneally, Officer of the Order of Australia, AO (born 7 October 1935) is an Australian novelist, playwright, essayist, and actor. He is best known for his historical fiction novel ''Schindler's Ark'', the story of Oskar Schindler' ...

, writer and founder of the Australian Republic Movement

The Australian Republic Movement (ARM) is a non-partisan organisation campaigning for Australia to become a republic. The ARM and its supporters have promoted various models, including a parliamentary republic, and the organisation has branche ...

(ARM)

* Gough Whitlam

Edward Gough Whitlam (11 July 191621 October 2014) was the 21st prime minister of Australia, serving from December 1972 to November 1975. To date the longest-serving federal leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP), he was notable for being ...

, former prime minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

(1972-1975)

* Malcolm Fraser

John Malcolm Fraser (; 21 May 1930 – 20 March 2015) was an Australian politician who served as the 22nd prime minister of Australia from 1975 to 1983. He held office as the leader of the Liberal Party of Australia, and is the fourth List of ...

, former prime minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

(1975-1983)

* Bob Hawke

Robert James Lee Hawke (9 December 1929 – 16 May 2019) was an Australian politician and trade unionist who served as the 23rd prime minister of Australia from 1983 to 1991. He held office as the Australian Labor Party, leader of the La ...

, former prime minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

(1983-1991)

* Paul Keating

Paul John Keating (born 18 January 1944) is an Australian former politician and trade unionist who served as the 24th prime minister of Australia from 1991 to 1996. He held office as the leader of the Labor Party (ALP), having previously ser ...

, former prime minister