Arthropod Tribes on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Arthropods ( ) are

Arthropoda is the largest animal

Arthropoda is the largest animal

The

The

Arthropod exoskeletons are made of

Arthropod exoskeletons are made of

The exoskeleton cannot stretch and thus restricts growth. Arthropods, therefore, replace their exoskeletons by undergoing

The exoskeleton cannot stretch and thus restricts growth. Arthropods, therefore, replace their exoskeletons by undergoing

Arthropods have open

Arthropods have open

Living arthropods have paired main nerve cords running along their bodies below the gut, and in each segment the cords form a pair of

Living arthropods have paired main nerve cords running along their bodies below the gut, and in each segment the cords form a pair of

The stiff

The stiff

Most arthropods lay eggs, but scorpions are

Most arthropods lay eggs, but scorpions are

It has been proposed that the

It has been proposed that the

The earliest fossil of likely pancrustacean larvae date from about in the

The earliest fossil of likely pancrustacean larvae date from about in the

Further analysis and discoveries in the 1990s reversed this view, and led to acceptance that arthropods are

Higher up the "family tree", the

File:20191203 Anomalocaris canadensis.png, ''

(

(

(

( Luolishaniidae)

Marrella.png, ''

(

(

(

(

File:20201229 Acutiramus cummingsi.png, ''

(

(

(

(Thylacocephala)

List of arthropod groups and genera († denotes extinct taxa)

* "Dinocaridida" Extinction, † (generally considered paraphyletic, sometimes treated as Lobopodia, lobopodians)

**

Crustaceans such as crabs, lobsters, crayfish, shrimp, and prawns have long been part of human cuisine, and are now raised commercially. Insects and their grubs are at least as nutritious as meat, and are eaten both raw and cooked in many cultures, though not most European, Hindu, and Islamic cultures. Cooked tarantulas are considered a delicacy in Cambodia, and by the Piaroa people, Piaroa Indians of southern Venezuela, after the highly irritant hairs – the spider's main defense system – are removed. Humans also Entomophagy#Unintentional ingestion, unintentionally eat arthropods in other foods, and food safety regulations lay down acceptable contamination levels for different kinds of food material. The intentional cultivation of arthropods and other small animals for human food, referred to as minilivestock, is now emerging in animal husbandry as an ecologically sound concept. Commercial butterfly breeding provides Lepidoptera stock to Butterfly house (conservatory), butterfly conservatories, educational exhibits, schools, research facilities, and cultural events.

However, the greatest contribution of arthropods to human food supply is by pollination: a 2008 study examined the 100 crops that FAO lists as grown for food, and estimated pollination's economic value as €153 billion, or 9.5 per cent of the value of world agricultural production used for human food in 2005. Besides pollinating, bees produce honey, which is the basis of a rapidly growing industry and international trade.

The red dye cochineal, produced from a Central American species of insect, was economically important to the Aztecs and Maya civilization, Mayans. While the region was under Spain, Spanish control, it became Mexico's second most-lucrative export, and is now regaining some of the ground it lost to synthetic competitors. Shellac, a resin secreted by a species of insect native to southern Asia, was historically used in great quantities for many applications in which it has mostly been replaced by synthetic resins, but it is still used in woodworking and as a food additive. The blood of horseshoe crabs contains a clotting agent, Limulus Amebocyte Lysate, which is now used to test that antibiotics and kidney machines are free of dangerous bacteria, and to detect spinal meningitis. Forensic entomology uses evidence provided by arthropods to establish the time and sometimes the place of death of a human, and in some cases the cause. Recently insects have also gained attention as potential sources of drugs and other medicinal substances.

The relative simplicity of the arthropods' body plan, allowing them to move on a variety of surfaces both on land and in water, have made them useful as models for robotics. The redundancy provided by segments allows arthropods and biomimesis, biomimetic robots to move normally even with damaged or lost appendages.

Although arthropods are the most numerous phylum on Earth, and thousands of arthropod species are venomous, they inflict relatively few serious bites and stings on humans. Far more serious are the effects on humans of diseases like malaria carried by Hematophagy, blood-sucking insects. Other blood-sucking insects infect livestock with diseases that kill many animals and greatly reduce the usefulness of others. Ticks can cause tick paralysis and several parasite-borne diseases in humans. A few of the closely related

Crustaceans such as crabs, lobsters, crayfish, shrimp, and prawns have long been part of human cuisine, and are now raised commercially. Insects and their grubs are at least as nutritious as meat, and are eaten both raw and cooked in many cultures, though not most European, Hindu, and Islamic cultures. Cooked tarantulas are considered a delicacy in Cambodia, and by the Piaroa people, Piaroa Indians of southern Venezuela, after the highly irritant hairs – the spider's main defense system – are removed. Humans also Entomophagy#Unintentional ingestion, unintentionally eat arthropods in other foods, and food safety regulations lay down acceptable contamination levels for different kinds of food material. The intentional cultivation of arthropods and other small animals for human food, referred to as minilivestock, is now emerging in animal husbandry as an ecologically sound concept. Commercial butterfly breeding provides Lepidoptera stock to Butterfly house (conservatory), butterfly conservatories, educational exhibits, schools, research facilities, and cultural events.

However, the greatest contribution of arthropods to human food supply is by pollination: a 2008 study examined the 100 crops that FAO lists as grown for food, and estimated pollination's economic value as €153 billion, or 9.5 per cent of the value of world agricultural production used for human food in 2005. Besides pollinating, bees produce honey, which is the basis of a rapidly growing industry and international trade.

The red dye cochineal, produced from a Central American species of insect, was economically important to the Aztecs and Maya civilization, Mayans. While the region was under Spain, Spanish control, it became Mexico's second most-lucrative export, and is now regaining some of the ground it lost to synthetic competitors. Shellac, a resin secreted by a species of insect native to southern Asia, was historically used in great quantities for many applications in which it has mostly been replaced by synthetic resins, but it is still used in woodworking and as a food additive. The blood of horseshoe crabs contains a clotting agent, Limulus Amebocyte Lysate, which is now used to test that antibiotics and kidney machines are free of dangerous bacteria, and to detect spinal meningitis. Forensic entomology uses evidence provided by arthropods to establish the time and sometimes the place of death of a human, and in some cases the cause. Recently insects have also gained attention as potential sources of drugs and other medicinal substances.

The relative simplicity of the arthropods' body plan, allowing them to move on a variety of surfaces both on land and in water, have made them useful as models for robotics. The redundancy provided by segments allows arthropods and biomimesis, biomimetic robots to move normally even with damaged or lost appendages.

Although arthropods are the most numerous phylum on Earth, and thousands of arthropod species are venomous, they inflict relatively few serious bites and stings on humans. Far more serious are the effects on humans of diseases like malaria carried by Hematophagy, blood-sucking insects. Other blood-sucking insects infect livestock with diseases that kill many animals and greatly reduce the usefulness of others. Ticks can cause tick paralysis and several parasite-borne diseases in humans. A few of the closely related

Venomous Arthropods

chapter in United States Environmental Protection Agency and University of Florida/Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences National Public Health Pesticide Applicator Training Manual

Arthropods – Arthropoda

Insect Life Forms {{Authority control Arthropods, Extant Cambrian first appearances

invertebrate

Invertebrates are animals that neither develop nor retain a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''spine'' or ''backbone''), which evolved from the notochord. It is a paraphyletic grouping including all animals excluding the chordata, chordate s ...

s in the phylum

In biology, a phylum (; : phyla) is a level of classification, or taxonomic rank, that is below Kingdom (biology), kingdom and above Class (biology), class. Traditionally, in botany the term division (taxonomy), division has been used instead ...

Arthropoda. They possess an exoskeleton

An exoskeleton () . is a skeleton that is on the exterior of an animal in the form of hardened integument, which both supports the body's shape and protects the internal organs, in contrast to an internal endoskeleton (e.g. human skeleton, that ...

with a cuticle

A cuticle (), or cuticula, is any of a variety of tough but flexible, non-mineral outer coverings of an organism, or parts of an organism, that provide protection. Various types of "cuticle" are non- homologous, differing in their origin, structu ...

made of chitin

Chitin (carbon, C8hydrogen, H13oxygen, O5nitrogen, N)n ( ) is a long-chain polymer of N-Acetylglucosamine, ''N''-acetylglucosamine, an amide derivative of glucose. Chitin is the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature (behind only cell ...

, often mineralised with calcium carbonate

Calcium carbonate is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is a common substance found in Rock (geology), rocks as the minerals calcite and aragonite, most notably in chalk and limestone, eggshells, gastropod shells, shellfish skel ...

, a body with differentiated ( metameric) segments, and paired jointed appendage

An appendage (or outgrowth) is an external body part or natural prolongation that protrudes from an organism's body such as an arm or a leg. Protrusions from single-celled bacteria and archaea are known as cell-surface appendages or surface app ...

s. In order to keep growing, they must go through stages of moulting

In biology, moulting (British English), or molting (American English), also known as sloughing, shedding, or in many invertebrates, ecdysis, is a process by which an animal casts off parts of its body to serve some beneficial purpose, either at ...

, a process by which they shed their exoskeleton to reveal a new one. They form an extremely diverse group of up to ten million species.

Haemolymph

Hemolymph, or haemolymph, is a fluid, similar to the blood in invertebrates, that circulates in the inside of the arthropod's body, remaining in direct contact with the animal's tissues. It is composed of a fluid plasma in which hemolymph ce ...

is the analogue of blood

Blood is a body fluid in the circulatory system of humans and other vertebrates that delivers necessary substances such as nutrients and oxygen to the cells, and transports metabolic waste products away from those same cells.

Blood is com ...

for most arthropods. An arthropod has an open circulatory system

In vertebrates, the circulatory system is a system of organs that includes the heart, blood vessels, and blood which is circulated throughout the body. It includes the cardiovascular system, or vascular system, that consists of the heart a ...

, with a body cavity called a haemocoel

In vertebrates, the circulatory system is a system of organs that includes the heart, blood vessels, and blood which is circulated throughout the body. It includes the cardiovascular system, or vascular system, that consists of the heart an ...

through which haemolymph circulates to the interior organs

In a multicellular organism, an organ is a collection of tissues joined in a structural unit to serve a common function. In the hierarchy of life, an organ lies between tissue and an organ system. Tissues are formed from same type cells to a ...

. Like their exteriors, the internal organs of arthropods are generally built of repeated segments. They have ladder-like nervous system

In biology, the nervous system is the complex system, highly complex part of an animal that coordinates its behavior, actions and sense, sensory information by transmitting action potential, signals to and from different parts of its body. Th ...

s, with paired ventral

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to describe unambiguously the anatomy of humans and other animals. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. This position prov ...

nerve cords running through all segments and forming paired ganglia

A ganglion (: ganglia) is a group of neuron cell bodies in the peripheral nervous system. In the somatic nervous system, this includes dorsal root ganglia and trigeminal ganglia among a few others. In the autonomic nervous system, there a ...

in each segment. Their heads are formed by fusion of varying numbers of segments, and their brain

The brain is an organ (biology), organ that serves as the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals. It consists of nervous tissue and is typically located in the head (cephalization), usually near organs for ...

s are formed by fusion of the ganglia of these segments and encircle the esophagus

The esophagus (American English), oesophagus (British English), or œsophagus (Œ, archaic spelling) (American and British English spelling differences#ae and oe, see spelling difference) all ; : ((o)e)(œ)sophagi or ((o)e)(œ)sophaguses), c ...

. The respiratory

The respiratory system (also respiratory apparatus, ventilatory system) is a biological system consisting of specific organs and structures used for gas exchange in animals and plants. The anatomy and physiology that make this happen varies gr ...

and excretory

Excretion is elimination of metabolic waste, which is an essential process in all organisms. In vertebrates, this is primarily carried out by the lungs, kidneys, and skin. This is in contrast with secretion, where the substance may have specific ...

systems of arthropods vary, depending as much on their environment as on the subphylum

In zoological nomenclature, a subphylum is a taxonomic rank below the rank of phylum.

The taxonomic rank of " subdivision" in fungi and plant taxonomy is equivalent to "subphylum" in zoological taxonomy. Some plant taxonomists have also used th ...

to which they belong.

Arthropods use combinations of compound eye

A compound eye is a Eye, visual organ found in arthropods such as insects and crustaceans. It may consist of thousands of ommatidium, ommatidia, which are tiny independent photoreception units that consist of a cornea, lens (anatomy), lens, and p ...

s and pigment-pit ocelli for vision. In most species, the ocelli can only detect the direction from which light is coming, and the compound eyes are the main source of information, but the main eyes of spider

Spiders (order (biology), order Araneae) are air-breathing arthropods that have eight limbs, chelicerae with fangs generally able to inject venom, and spinnerets that extrude spider silk, silk. They are the largest order of arachnids and ran ...

s are ocelli that can form images and, in a few cases, can swivel to track prey. Arthropods also have a wide range of chemical and mechanical sensors, mostly based on modifications of the many bristles known as seta

In biology, setae (; seta ; ) are any of a number of different bristle- or hair-like structures on living organisms.

Animal setae

Protostomes

Depending partly on their form and function, protostome setae may be called macrotrichia, chaetae, ...

e that project through their cuticles. Similarly, their reproduction and development are varied; all terrestrial

Terrestrial refers to things related to land or the planet Earth, as opposed to extraterrestrial.

Terrestrial may also refer to:

* Terrestrial animal, an animal that lives on land opposed to living in water, or sometimes an animal that lives on o ...

species use internal fertilization

Internal fertilization is the union of an egg and sperm cell during sexual reproduction inside the female body. Internal fertilization, unlike its counterpart, external fertilization, brings more control to the female with reproduction. For inte ...

, but this is sometimes by indirect transfer of the sperm

Sperm (: sperm or sperms) is the male reproductive Cell (biology), cell, or gamete, in anisogamous forms of sexual reproduction (forms in which there is a larger, female reproductive cell and a smaller, male one). Animals produce motile sperm ...

via an appendage or the ground, rather than by direct injection. Aquatic species use either internal or external fertilization

External fertilization is a mode of reproduction in which a male organism's sperm fertilizes a female organism's egg outside of the female's body.

It is contrasted with internal fertilization, in which sperm are introduced via insemination and then ...

. Almost all arthropods lay eggs, with many species giving birth to live young after the eggs have hatched inside the mother; but a few are genuinely viviparous

In animals, viviparity is development of the embryo inside the body of the mother, with the maternal circulation providing for the metabolic needs of the embryo's development, until the mother gives birth to a fully or partially developed juve ...

, such as aphid

Aphids are small sap-sucking insects in the Taxonomic rank, family Aphididae. Common names include greenfly and blackfly, although individuals within a species can vary widely in color. The group includes the fluffy white Eriosomatinae, woolly ...

s. Arthropod hatchlings vary from miniature adults to grubs and caterpillar

Caterpillars ( ) are the larval stage of members of the order Lepidoptera (the insect order comprising butterflies and moths).

As with most common names, the application of the word is arbitrary, since the larvae of sawflies (suborder ...

s that lack jointed limbs and eventually undergo a total metamorphosis

Metamorphosis is a biological process by which an animal physically develops including birth transformation or hatching, involving a conspicuous and relatively abrupt change in the animal's body structure through cell growth and different ...

to produce the adult form. The level of maternal care for hatchlings varies from nonexistent to the prolonged care provided by social insects

Eusociality (Greek 'good' and social) is the highest level of organization of sociality. It is defined by the following characteristics: cooperative brood care (including care of offspring from other individuals), overlapping generations with ...

.

The evolutionary ancestry of arthropods dates back to the Cambrian

The Cambrian ( ) is the first geological period of the Paleozoic Era, and the Phanerozoic Eon. The Cambrian lasted 51.95 million years from the end of the preceding Ediacaran period 538.8 Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the Ordov ...

period. The group is generally regarded as monophyletic

In biological cladistics for the classification of organisms, monophyly is the condition of a taxonomic grouping being a clade – that is, a grouping of organisms which meets these criteria:

# the grouping contains its own most recent co ...

, and many analyses support the placement of arthropods with cycloneuralia

Cycloneuralia is a proposed clade of ecdysozoan animals including the Scalidophora ( Kinorhynchans, Loriciferans, Priapulids), the Nematoida (nematodes, Nematomorphs), and the extinct Palaeoscolecida. It may be paraphyletic, or may be a si ...

ns (or their constituent clades) in a superphylum Ecdysozoa

Ecdysozoa () is a group of protostome animals, including Arthropoda (insects, chelicerates (including arachnids), crustaceans, and myriapods), Nematoda, and several smaller phylum (biology), phyla. The grouping of these animal phyla into a single ...

. Overall, however, the basal relationships of animals are not yet well resolved. Likewise, the relationships between various arthropod groups are still actively debated. Today, arthropods contribute to the human food supply both directly as food, and more importantly, indirectly as pollinators

A pollinator is an animal that moves pollen from the male anther of a flower to the female stigma of a flower. This helps to bring about fertilization of the ovules in the flower by the male gametes from the pollen grains.

Insects are the ma ...

of crops. Some species are known to spread severe disease to humans, livestock, and crops.

Etymology

The word ''arthropod'' comes from theGreek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

, and ( gen. ) or , which together mean "jointed leg", with the word "arthropodes" initially used in anatomical descriptions by Barthélemy Charles Joseph Dumortier

Barthélemy Charles Joseph Dumortier (; 3 April 1797 – 9 July 1878) was a Belgians, Belgian who conducted a parallel career of botanist and Member of Parliament and is the first discoverer of biological cell division.

Over the course of his lif ...

published in 1832. The designation "Arthropoda" appears to have been first used in 1843 by the German zoologist Johann Ludwig Christian Gravenhorst

Johann Ludwig Christian Carl Gravenhorst (14 November 1777 – 14 January 1857), sometimes Jean Louis Charles or Carl, was a German entomologist, herpetologist, and zoologist.

Life

Gravenhorst was born in Braunschweig. His early interest in inse ...

(1777–1857). The origin of the name has been the subject of considerable confusion, with credit often given erroneously to Pierre André Latreille

Pierre André Latreille (; 29 November 1762 – 6 February 1833) was a French zoology, zoologist, specialising in arthropods. Having trained as a Roman Catholic priest before the French Revolution, Latreille was imprisoned, and only regained hi ...

or Karl Theodor Ernst von Siebold

Prof Karl (Carl) Theodor Ernst von Siebold Royal Society of London, FRS(For) HFRSE (16 February 1804 – 7 April 1885) was a German physiologist and zoologist. He was responsible for the introduction of the taxa Arthropoda and Rhizopoda, and for d ...

instead, among various others.

Terrestrial arthropods are often called bugs. The term is also occasionally extended to colloquial names for freshwater or marine crustacean

Crustaceans (from Latin meaning: "those with shells" or "crusted ones") are invertebrate animals that constitute one group of arthropods that are traditionally a part of the subphylum Crustacea (), a large, diverse group of mainly aquatic arthrop ...

s (e.g., Balmain bug Balmain may refer to:

Places

* Balmain, New South Wales, a suburb of Sydney, Australia

* Electoral district of Balmain, an electoral division in New South Wales, Australia

* Balmain East, New South Wales, a suburb of Sydney, Australia

* Balmain Ho ...

, Moreton Bay bug

''Thenus orientalis'' is a species of slipper lobster from the Indian and Pacific oceans.

''T. orientalis'' is known by a number of common names. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization prefers the name flathead lobster, while i ...

, mudbug

Crayfish are freshwater crustaceans belonging to the infraorder Astacidea, which also contains lobsters. Taxonomically, they are members of the Superfamily (taxonomy), superfamilies Astacoidea and Parastacoidea. They breathe through feather- ...

) and used by physicians and bacteriologists for disease-causing germs (e.g., superbug Super Bug or Superbug may refer to:

* Superbug, an antimicrobial- or antibiotic-resistant microorganism

* ''Super Bug'' (video game), a 1977 arcade game featuring a Volkswagen Beetle

* ''Superbug'' (film series), a West German film series about ...

s), but entomologists reserve this term for a narrow category of "true bugs

Hemiptera (; ) is an order (biology), order of insects, commonly called true bugs, comprising more than 80,000 species within groups such as the cicadas, aphids, planthoppers, leafhoppers, assassin bugs, Cimex, bed bugs, and shield bugs. They ...

", insects of the order Hemiptera

Hemiptera (; ) is an order of insects, commonly called true bugs, comprising more than 80,000 species within groups such as the cicadas, aphids, planthoppers, leafhoppers, assassin bugs, bed bugs, and shield bugs. They range in size from ...

.

Description

Arthropods areinvertebrate

Invertebrates are animals that neither develop nor retain a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''spine'' or ''backbone''), which evolved from the notochord. It is a paraphyletic grouping including all animals excluding the chordata, chordate s ...

s with segmented bodies and jointed limbs. The exoskeleton

An exoskeleton () . is a skeleton that is on the exterior of an animal in the form of hardened integument, which both supports the body's shape and protects the internal organs, in contrast to an internal endoskeleton (e.g. human skeleton, that ...

or cuticle

A cuticle (), or cuticula, is any of a variety of tough but flexible, non-mineral outer coverings of an organism, or parts of an organism, that provide protection. Various types of "cuticle" are non- homologous, differing in their origin, structu ...

consists of chitin

Chitin (carbon, C8hydrogen, H13oxygen, O5nitrogen, N)n ( ) is a long-chain polymer of N-Acetylglucosamine, ''N''-acetylglucosamine, an amide derivative of glucose. Chitin is the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature (behind only cell ...

, a polymer of N-Acetylglucosamine. The cuticle of many crustaceans, beetle mites, the clades Penetini and Archaeoglenini inside the beetle subfamily Phrenapatinae

Phrenapatinae is a subfamily of darkling beetles in the family Tenebrionidae

Darkling beetle is the common name for members of the beetle family Tenebrionidae, comprising over 20,000 species in a cosmopolitan distribution.

Taxonomy

''Tenebrio ...

, and millipedes (except for bristly millipedes) is also biomineralized with calcium carbonate

Calcium carbonate is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is a common substance found in Rock (geology), rocks as the minerals calcite and aragonite, most notably in chalk and limestone, eggshells, gastropod shells, shellfish skel ...

. Calcification of the endosternite, an internal structure used for muscle attachments, also occurs in some opiliones

The Opiliones (formerly Phalangida) are an Order (biology), order of arachnids,

Common name, colloquially known as harvestmen, harvesters, harvest spiders, or daddy longlegs (see below). , over 6,650 species of harvestmen have been discovered w ...

, and the pupal cuticle of the fly ''Bactrocera dorsalis

''Bactrocera dorsalis'', previously known as ''Dacus dorsalis'' and commonly referred to as the oriental fruit fly, is a species of Tephritidae, tephritid fruit fly that is endemism, endemic to Southeast Asia. It is one of the major Pest (organis ...

'' contains calcium phosphate.

Diversity

Arthropoda is the largest animal

Arthropoda is the largest animal phylum

In biology, a phylum (; : phyla) is a level of classification, or taxonomic rank, that is below Kingdom (biology), kingdom and above Class (biology), class. Traditionally, in botany the term division (taxonomy), division has been used instead ...

, with the estimates of the number of arthropod species varying from 1,170,000 to 5~10 million and accounting for over 80 percent of all known living animal species. One arthropod sub-group, the insect

Insects (from Latin ') are Hexapoda, hexapod invertebrates of the class (biology), class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body (Insect morphology#Head, head, ...

s, includes more described species than any other taxonomic class. The total number of species remains difficult to determine, as estimates rely on census counts at specific locations, scaled up and projected onto other regions, then totalled - allowing for double-counting - to cover the whole world. Modeling assumptions are involved at each stage, introducing uncertainty. A study in 1992 estimated that there were 500,000 species of animals and plants in Costa Rica

Costa Rica, officially the Republic of Costa Rica, is a country in Central America. It borders Nicaragua to the north, the Caribbean Sea to the northeast, Panama to the southeast, and the Pacific Ocean to the southwest, as well as Maritime bo ...

alone, of which 365,000 were arthropods.

They are important members of marine, freshwater, land and air ecosystem

An ecosystem (or ecological system) is a system formed by Organism, organisms in interaction with their Biophysical environment, environment. The Biotic material, biotic and abiotic components are linked together through nutrient cycles and en ...

s and one of only two major animal groups that have adapted to life in dry environments; the other is amniote

Amniotes are tetrapod vertebrate animals belonging to the clade Amniota, a large group that comprises the vast majority of living terrestrial animal, terrestrial and semiaquatic vertebrates. Amniotes evolution, evolved from amphibious Stem tet ...

s, whose living members are reptiles, birds and mammals. Ruppert, Fox & Barnes (2004), pp. 518–522 Both the smallest and largest arthropods are crustacean

Crustaceans (from Latin meaning: "those with shells" or "crusted ones") are invertebrate animals that constitute one group of arthropods that are traditionally a part of the subphylum Crustacea (), a large, diverse group of mainly aquatic arthrop ...

s. The smallest belong to the class Tantulocarida

Tantulocarida is a highly specialised group of parasitic crustaceans that consists of about 33 species, treated as a class in superclass Multicrustacea. They are typically ectoparasites that infest copepods, isopods, tanaids, amphipods and ost ...

, some of which are less than long. The largest

Large means of great size.

Large may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Arbitrarily large, a phrase in mathematics

* Large cardinal, a property of certain transfinite numbers

* Large category, a category with a proper class of objects and morphisms (or ...

are species in the class Malacostraca

Malacostraca is the second largest of the six classes of pancrustaceans behind insects, containing about 40,000 living species, divided among 16 orders. Its members, the malacostracans, display a great diversity of body forms and include crab ...

, with the legs of the Japanese spider crab

The Japanese giant spider crab (''Macrocheira kaempferi'') is a species of marine crab and is the biggest one that lives in the waters around Japan. At around 3.7 meters, it has the largest leg-span of any arthropod. The Japanese name for this s ...

potentially spanning up to and the American lobster

The American lobster (''Homarus americanus'') is a species of lobster found on the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast of North America, chiefly from Labrador to New Jersey. It is also known as Atlantic lobster, Canadian lobster, true lobster, norther ...

reaching weights over 20 kg (44 lbs).

Segmentation

The

The embryo

An embryo ( ) is the initial stage of development for a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after fertilization of the female egg cell by the male sp ...

s of all arthropods are segmented, built from a series of repeated modules. The last common ancestor

A most recent common ancestor (MRCA), also known as a last common ancestor (LCA), is the most recent individual from which all organisms of a set are inferred to have descended. The most recent common ancestor of a higher taxon is generally assu ...

of living arthropods probably consisted of a series of undifferentiated segments, each with a pair of appendage

An appendage (or outgrowth) is an external body part or natural prolongation that protrudes from an organism's body such as an arm or a leg. Protrusions from single-celled bacteria and archaea are known as cell-surface appendages or surface app ...

s that functioned as limbs. However, all known living and fossil arthropods have grouped segments into tagmata in which segments and their limbs are specialized in various ways.

The three-part appearance of many insect

Insects (from Latin ') are Hexapoda, hexapod invertebrates of the class (biology), class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body (Insect morphology#Head, head, ...

bodies and the two-part appearance of spider

Spiders (order (biology), order Araneae) are air-breathing arthropods that have eight limbs, chelicerae with fangs generally able to inject venom, and spinnerets that extrude spider silk, silk. They are the largest order of arachnids and ran ...

s is a result of this grouping. There are no external signs of segmentation in mite

Mites are small arachnids (eight-legged arthropods) of two large orders, the Acariformes and the Parasitiformes, which were historically grouped together in the subclass Acari. However, most recent genetic analyses do not recover the two as eac ...

s. Arthropods also have two body elements that are not part of this serially repeated pattern of segments, an ocular somite at the front, where the mouth and eyes originated, and a telson

The telson () is the hindmost division of the body of an arthropod. Depending on the definition, the telson is either considered to be the final segment (biology), segment of the arthropod body, or an additional division that is not a true segm ...

at the rear, behind the anus

In mammals, invertebrates and most fish, the anus (: anuses or ani; from Latin, 'ring' or 'circle') is the external body orifice at the ''exit'' end of the digestive tract (bowel), i.e. the opposite end from the mouth. Its function is to facil ...

.

Originally, it seems that each appendage-bearing segment had two separate pairs of appendages: an upper, unsegmented exite

The arthropod leg is a form of jointed appendage of arthropods, usually used for walking. Many of the terms used for arthropod leg segments (called podomeres) are of Latin origin, and may be confused with terms for bones: ''coxa'' (meaning hip, : ...

and a lower, segmented endopod. These would later fuse into a single pair of biramous

The arthropod leg is a form of jointed appendage of arthropods, usually used for walking. Many of the terms used for arthropod leg segments (called podomeres) are of Latin origin, and may be confused with terms for bones: ''coxa'' (meaning hip, ...

appendages united by a basal segment (protopod or basipod), with the upper branch acting as a gill

A gill () is a respiration organ, respiratory organ that many aquatic ecosystem, aquatic organisms use to extract dissolved oxygen from water and to excrete carbon dioxide. The gills of some species, such as hermit crabs, have adapted to allow r ...

while the lower branch was used for locomotion. The appendages of most crustaceans

Crustaceans (from Latin meaning: "those with shells" or "crusted ones") are invertebrate animals that constitute one group of Arthropod, arthropods that are traditionally a part of the subphylum Crustacea (), a large, diverse group of mainly aquat ...

and some extinct taxa such as trilobites

Trilobites (; meaning "three-lobed entities") are extinct marine arthropods that form the class Trilobita. One of the earliest groups of arthropods to appear in the fossil record, trilobites were among the most successful of all early animals, ...

have another segmented branch known as exopod

The arthropod leg is a form of jointed appendage of arthropods, usually used for walking. Many of the terms used for arthropod leg segments (called podomeres) are of Latin origin, and may be confused with terms for bones: ''coxa'' (meaning hip (a ...

s, but whether these structures have a single origin remain controversial. In some segments of all known arthropods, the appendages have been modified, for example to form gills, mouth-parts, antennae for collecting information, or claws for grasping; arthropods are "like Swiss Army knives, each equipped with a unique set of specialized tools." In many arthropods, appendages have vanished from some regions of the body; it is particularly common for abdominal appendages to have disappeared or be highly modified.

The most conspicuous specialization of segments is in the head. The four major groups of arthropods – Chelicerata

The subphylum Chelicerata (from Neo-Latin, , ) constitutes one of the major subdivisions of the phylum Arthropoda. Chelicerates include the sea spiders, horseshoe crabs, and arachnids (including harvestmen, scorpions, spiders, solifuges, tic ...

(sea spider

Sea spiders are marine arthropods of the class (biology), class Pycnogonida, hence they are also called pycnogonids (; named after ''Pycnogonum'', the type genus; with the suffix '). The class includes the only now-living order (biology), order P ...

s, horseshoe crab

Horseshoe crabs are arthropods of the family Limulidae and the only surviving xiphosurans. Despite their name, they are not true crabs or even crustaceans; they are chelicerates, more closely related to arachnids like spiders, ticks, and scor ...

s and arachnid

Arachnids are arthropods in the Class (biology), class Arachnida () of the subphylum Chelicerata. Arachnida includes, among others, spiders, scorpions, ticks, mites, pseudoscorpions, opiliones, harvestmen, Solifugae, camel spiders, Amblypygi, wh ...

s), Myriapoda

Myriapods () are the members of subphylum Myriapoda, containing arthropods such as millipedes and centipedes. The group contains about 13,000 species, all of them terrestrial.

Although molecular evidence and similar fossils suggests a diversifi ...

(symphylan

Symphylans, also known as garden centipedes or pseudocentipedes, are soil-dwelling arthropods of the class (biology), class Symphyla in the subphylum Myriapoda. Symphylans resemble centipedes, but are very small, non-venomous, and Myriapoda#Myri ...

s, pauropod

Pauropoda is a class of small, pale, millipede-like arthropods in the subphylum Myriapoda. More than 900 species in twelve families are found worldwide, living in soil and leaf mold. Pauropods look like centipedes or millipedes and may be a sist ...

s, millipede

Millipedes (originating from the Latin , "thousand", and , "foot") are a group of arthropods that are characterised by having two pairs of jointed legs on most body segments; they are known scientifically as the class Diplopoda, the name derive ...

s and centipede

Centipedes (from Neo-Latin , "hundred", and Latin , "foot") are predatory arthropods belonging to the class Chilopoda (Ancient Greek , ''kheilos'', "lip", and Neo-Latin suffix , "foot", describing the forcipules) of the subphylum Myriapoda, ...

s), Pancrustacea

Pancrustacea is the clade that comprises all crustaceans and all hexapods (insects and relatives). This grouping is contrary to the Atelocerata hypothesis, in which Hexapoda and Myriapoda are sister taxa, and Crustacea are only more distantl ...

(oligostracan

Oligostraca is a superclass (biology), superclass of crustaceans. It consists of the following classes:

Class Derocheilocarididae, Mystacocarida: Minute crustaceans (0.5 to 1 mm in length) restricted to interstitial marine sediments. Locomo ...

s, copepod

Copepods (; meaning 'oar-feet') are a group of small crustaceans found in nearly every freshwater and saltwater habitat (ecology), habitat. Some species are planktonic (living in the water column), some are benthos, benthic (living on the sedimen ...

s, malacostracan

Malacostraca is the second largest of the six class (biology), classes of pancrustaceans behind insects, containing about 40,000 living species, divided among 16 order (biology), orders. Its members, the malacostracans, display a great diversity ...

s, branchiopod

Branchiopoda, from Ancient Greek βράγχια (''bránkhia''), meaning "gill", and πούς (''poús''), meaning "foot", is a class of crustaceans. It comprises fairy shrimp, clam shrimp, Diplostraca (or Cladocera), Notostraca, the Devonian ...

s, hexapods, etc.), and the extinct Trilobita

Trilobites (; meaning "three-lobed entities") are extinction, extinct marine arthropods that form the class (biology), class Trilobita. One of the earliest groups of arthropods to appear in the fossil record, trilobites were among the most succ ...

– have heads formed of various combinations of segments, with appendages that are missing or specialized in different ways. Despite myriapods and hexapods both having similar head combinations, hexapods are deeply nested within crustacea while myriapods are not, so these traits are believed to have evolved separately. In addition, some extinct arthropods, such as ''Marrella

''Marrella'' is an extinct genus of marrellomorph arthropod known from the Middle Cambrian of North America and Asia. It is the most common animal represented in the Burgess Shale of British Columbia, Canada, with tens of thousands of specimen ...

'', belong to none of these groups, as their heads are formed by their own particular combinations of segments and specialized appendages. Summarised in .

Working out the evolutionary stages by which all these different combinations could have appeared is so difficult that it has long been known as "The arthropod head problem

The (pan)arthropod head problem is a long-standing zoological dispute concerning the Segmentation (biology), segmental composition of the heads of the various arthropod groups, and how they are evolutionarily related to each other. While the dis ...

". In 1960, R. E. Snodgrass even hoped it would not be solved, as he found trying to work out solutions to be fun.

Exoskeleton

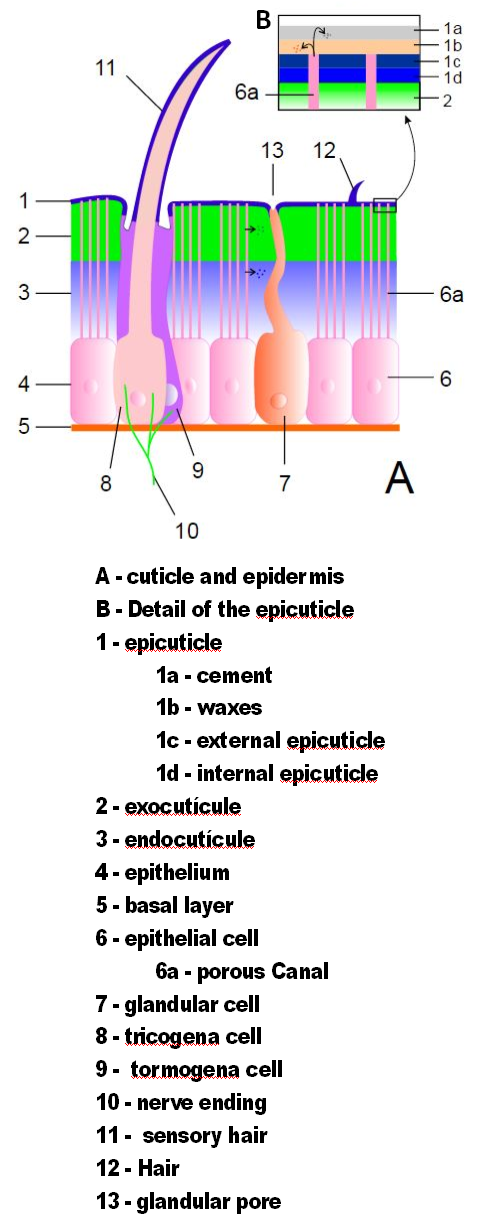

cuticle

A cuticle (), or cuticula, is any of a variety of tough but flexible, non-mineral outer coverings of an organism, or parts of an organism, that provide protection. Various types of "cuticle" are non- homologous, differing in their origin, structu ...

, a non-cellular material secreted by the epidermis

The epidermis is the outermost of the three layers that comprise the skin, the inner layers being the dermis and Subcutaneous tissue, hypodermis. The epidermal layer provides a barrier to infection from environmental pathogens and regulates the ...

. Their cuticles vary in the details of their structure, but generally consist of three main layers: the epicuticle

Arthropods are covered with a tough, resilient integument, cuticle or exoskeleton of chitin. Generally the exoskeleton will have thickened areas in which the chitin is reinforced or stiffened by materials such as minerals or hardened proteins. T ...

, a thin outer wax

Waxes are a diverse class of organic compounds that are lipophilic, malleable solids near ambient temperatures. They include higher alkanes and lipids, typically with melting points above about 40 °C (104 °F), melting to give lo ...

y coat that moisture-proofs the other layers and gives them some protection; the exocuticle

Arthropods are covered with a tough, resilient integument, cuticle or exoskeleton of chitin. Generally the exoskeleton will have thickened areas in which the chitin is reinforced or stiffened by materials such as minerals or hardened proteins. T ...

, which consists of chitin

Chitin (carbon, C8hydrogen, H13oxygen, O5nitrogen, N)n ( ) is a long-chain polymer of N-Acetylglucosamine, ''N''-acetylglucosamine, an amide derivative of glucose. Chitin is the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature (behind only cell ...

and chemically hardened protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residue (biochemistry), residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including Enzyme catalysis, catalysing metab ...

s; and the endocuticle

Arthropods are covered with a tough, resilient integument, cuticle or exoskeleton of chitin. Generally the exoskeleton will have thickened areas in which the chitin is reinforced or stiffened by materials such as minerals or hardened proteins. T ...

, which consists of chitin and unhardened proteins. The exocuticle and endocuticle together are known as the procuticle

Arthropods are covered with a tough, resilient integument, cuticle or exoskeleton of chitin. Generally the exoskeleton will have thickened areas in which the chitin is reinforced or stiffened by materials such as minerals or hardened proteins. T ...

. Each body segment and limb section is encased in hardened cuticle. The joints between body segments and between limb sections are covered by flexible cuticle.

The exoskeletons of most aquatic crustacean

Crustaceans (from Latin meaning: "those with shells" or "crusted ones") are invertebrate animals that constitute one group of arthropods that are traditionally a part of the subphylum Crustacea (), a large, diverse group of mainly aquatic arthrop ...

s are biomineralized with calcium carbonate

Calcium carbonate is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is a common substance found in Rock (geology), rocks as the minerals calcite and aragonite, most notably in chalk and limestone, eggshells, gastropod shells, shellfish skel ...

extracted from the water. Some terrestrial crustaceans have developed means of storing the mineral, since on land they cannot rely on a steady supply of dissolved calcium carbonate. Biomineralization generally affects the exocuticle and the outer part of the endocuticle. Two recent hypotheses about the evolution of biomineralization in arthropods and other groups of animals propose that it provides tougher defensive armor, and that it allows animals to grow larger and stronger by providing more rigid skeletons; and in either case a mineral-organic composite

Composite or compositing may refer to:

Materials

* Composite material, a material that is made from several different substances

** Metal matrix composite, composed of metal and other parts

** Cermet, a composite of ceramic and metallic material ...

exoskeleton is cheaper to build than an all-organic one of comparable strength.

The cuticle may have seta

In biology, setae (; seta ; ) are any of a number of different bristle- or hair-like structures on living organisms.

Animal setae

Protostomes

Depending partly on their form and function, protostome setae may be called macrotrichia, chaetae, ...

e (bristles) growing from special cells in the epidermis. Setae are as varied in form and function as appendages. For example, they are often used as sensors to detect air or water currents, or contact with objects; aquatic arthropods use feather

Feathers are epidermal growths that form a distinctive outer covering, or plumage, on both avian (bird) and some non-avian dinosaurs and other archosaurs. They are the most complex integumentary structures found in vertebrates and an exa ...

-like setae to increase the surface area of swimming appendages and to filter food particles out of water; aquatic insects, which are air-breathers, use thick felt

Felt is a textile that is produced by matting, condensing, and pressing fibers together. Felt can be made of natural fibers such as wool or animal fur, or from synthetic fibers such as petroleum-based acrylic fiber, acrylic or acrylonitrile or ...

-like coats of setae to trap air, extending the time they can spend under water; heavy, rigid setae serve as defensive spines.

Although all arthropods use muscles attached to the inside of the exoskeleton to flex their limbs, some still use hydraulic

Hydraulics () is a technology and applied science using engineering, chemistry, and other sciences involving the mechanical properties and use of liquids. At a very basic level, hydraulics is the liquid counterpart of pneumatics, which concer ...

pressure to extend them, a system inherited from their pre-arthropod ancestors; for example, all spiders extend their legs hydraulically and can generate pressures up to eight times their resting level.

Moulting

The exoskeleton cannot stretch and thus restricts growth. Arthropods, therefore, replace their exoskeletons by undergoing

The exoskeleton cannot stretch and thus restricts growth. Arthropods, therefore, replace their exoskeletons by undergoing ecdysis

Ecdysis is the moulting of the cuticle in many invertebrates of the clade Ecdysozoa. Since the cuticle of these animals typically forms a largely inelastic exoskeleton, it is shed during growth and a new, larger covering is formed. The remnant ...

(moulting), or shedding the old exoskeleton, the exuviae

In biology, exuviae are the remains of an exoskeleton and related structures that are left after ecdysozoans (including insects, crustaceans and arachnids) have molted. The exuviae of an animal can be important to biologists as they can often be ...

, after growing a new one that is not yet hardened. Moulting cycles run nearly continuously until an arthropod reaches full size. The developmental stages between each moult (ecdysis) until sexual maturity is reached is called an instar

An instar (, from the Latin '' īnstar'' 'form, likeness') is a developmental stage of arthropods, such as insects, which occurs between each moult (''ecdysis'') until sexual maturity is reached. Arthropods must shed the exoskeleton in order to ...

. Differences between instars can often be seen in altered body proportions, colors, patterns, changes in the number of body segments or head width. After moulting, i.e. shedding their exoskeleton, the juvenile arthropods continue in their life cycle until they either pupate or moult again. Ruppert, Fox & Barnes (2004), pp. 523–524

In the initial phase of moulting, the animal stops feeding and its epidermis releases moulting fluid, a mixture of enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

s that digests the endocuticle

Arthropods are covered with a tough, resilient integument, cuticle or exoskeleton of chitin. Generally the exoskeleton will have thickened areas in which the chitin is reinforced or stiffened by materials such as minerals or hardened proteins. T ...

and thus detaches the old cuticle. This phase begins when the epidermis

The epidermis is the outermost of the three layers that comprise the skin, the inner layers being the dermis and Subcutaneous tissue, hypodermis. The epidermal layer provides a barrier to infection from environmental pathogens and regulates the ...

has secreted a new epicuticle

Arthropods are covered with a tough, resilient integument, cuticle or exoskeleton of chitin. Generally the exoskeleton will have thickened areas in which the chitin is reinforced or stiffened by materials such as minerals or hardened proteins. T ...

to protect it from the enzymes, and the epidermis secretes the new exocuticle while the old cuticle is detaching. When this stage is complete, the animal makes its body swell by taking in a large quantity of water or air, and this makes the old cuticle split along predefined weaknesses where the old exocuticle was thinnest. It commonly takes several minutes for the animal to struggle out of the old cuticle. At this point, the new one is wrinkled and so soft that the animal cannot support itself and finds it very difficult to move, and the new endocuticle has not yet formed. The animal continues to pump itself up to stretch the new cuticle as much as possible, then hardens the new exocuticle and eliminates the excess air or water. By the end of this phase, the new endocuticle has formed. Many arthropods then eat the discarded cuticle to reclaim its materials.

Because arthropods are unprotected and nearly immobilized until the new cuticle has hardened, they are in danger both of being trapped in the old cuticle and of being attacked by predator

Predation is a biological interaction in which one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common List of feeding behaviours, feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation ...

s. Moulting may be responsible for 80 to 90% of all arthropod deaths.

Internal organs

Arthropod bodies are also segmented internally, and the nervous, muscular, circulatory, and excretory systems have repeated components. Arthropods come from a lineage of animals that have acoelom

The coelom (or celom) is the main body cavity in many animals and is positioned inside the body to surround and contain the digestive tract and other organs. In some animals, it is lined with mesothelium. In other animals, such as molluscs, i ...

, a membrane-lined cavity between the gut and the body wall that accommodates the internal organs. The strong, segmented limbs of arthropods eliminate the need for one of the coelom's main ancestral functions, as a hydrostatic skeleton

A hydrostatic skeleton or hydroskeleton is a type of skeleton supported by hydrostatic fluid pressure or liquid, common among soft-bodied organism, soft-bodied invertebrate animals colloquially referred to as "worms". While more advanced organisms ...

, which muscles compress in order to change the animal's shape and thus enable it to move. Hence the coelom of the arthropod is reduced to small areas around the reproductive and excretory systems. Its place is largely taken by a hemocoel

In vertebrates, the circulatory system is a organ system, system of organs that includes the heart, blood vessels, and blood which is circulated throughout the body. It includes the cardiovascular system, or vascular system, that consists of ...

, a cavity that runs most of the length of the body and through which blood

Blood is a body fluid in the circulatory system of humans and other vertebrates that delivers necessary substances such as nutrients and oxygen to the cells, and transports metabolic waste products away from those same cells.

Blood is com ...

flows. Ruppert, Fox & Barnes (2004), pp. 527–528

Respiration and circulation

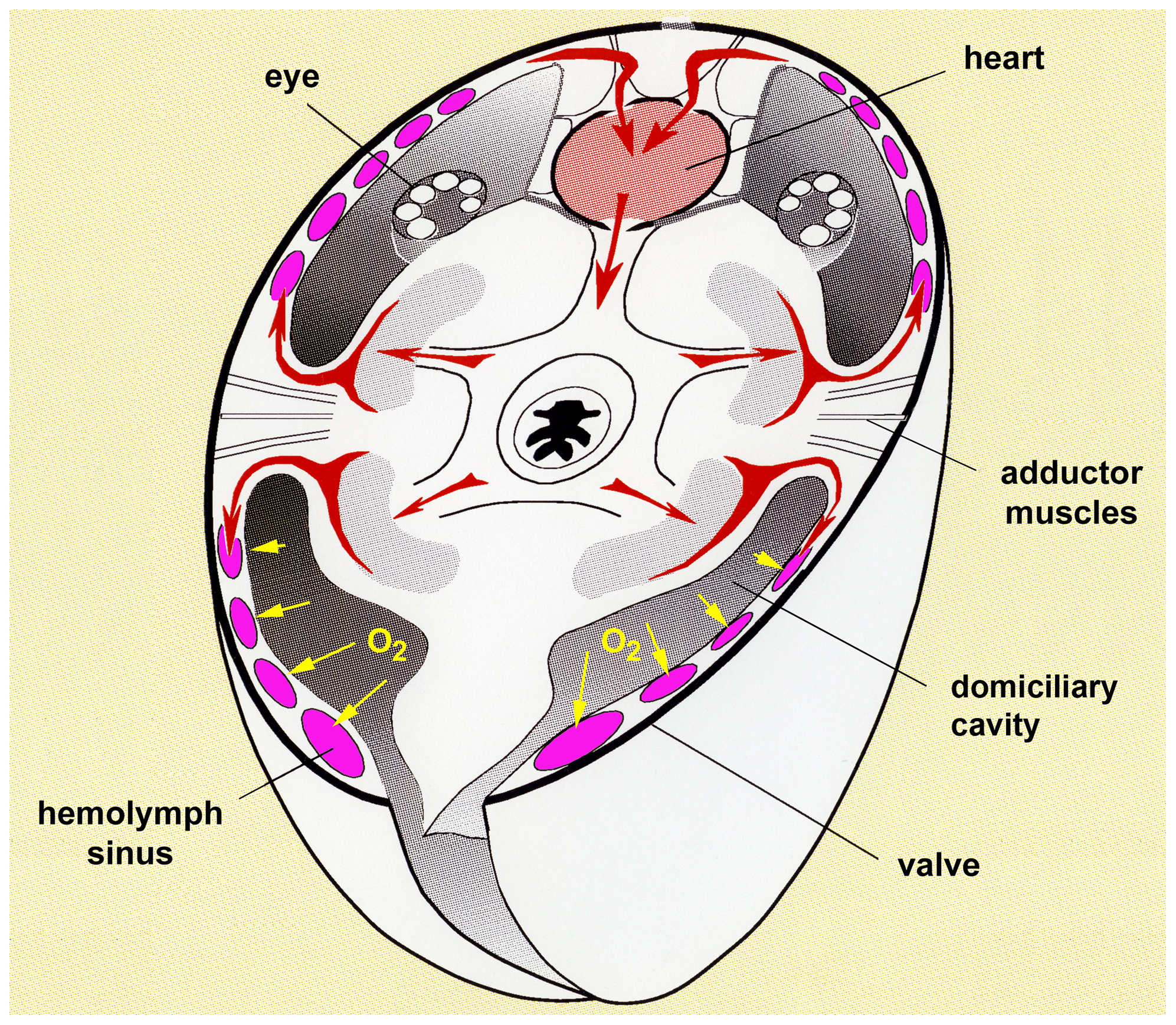

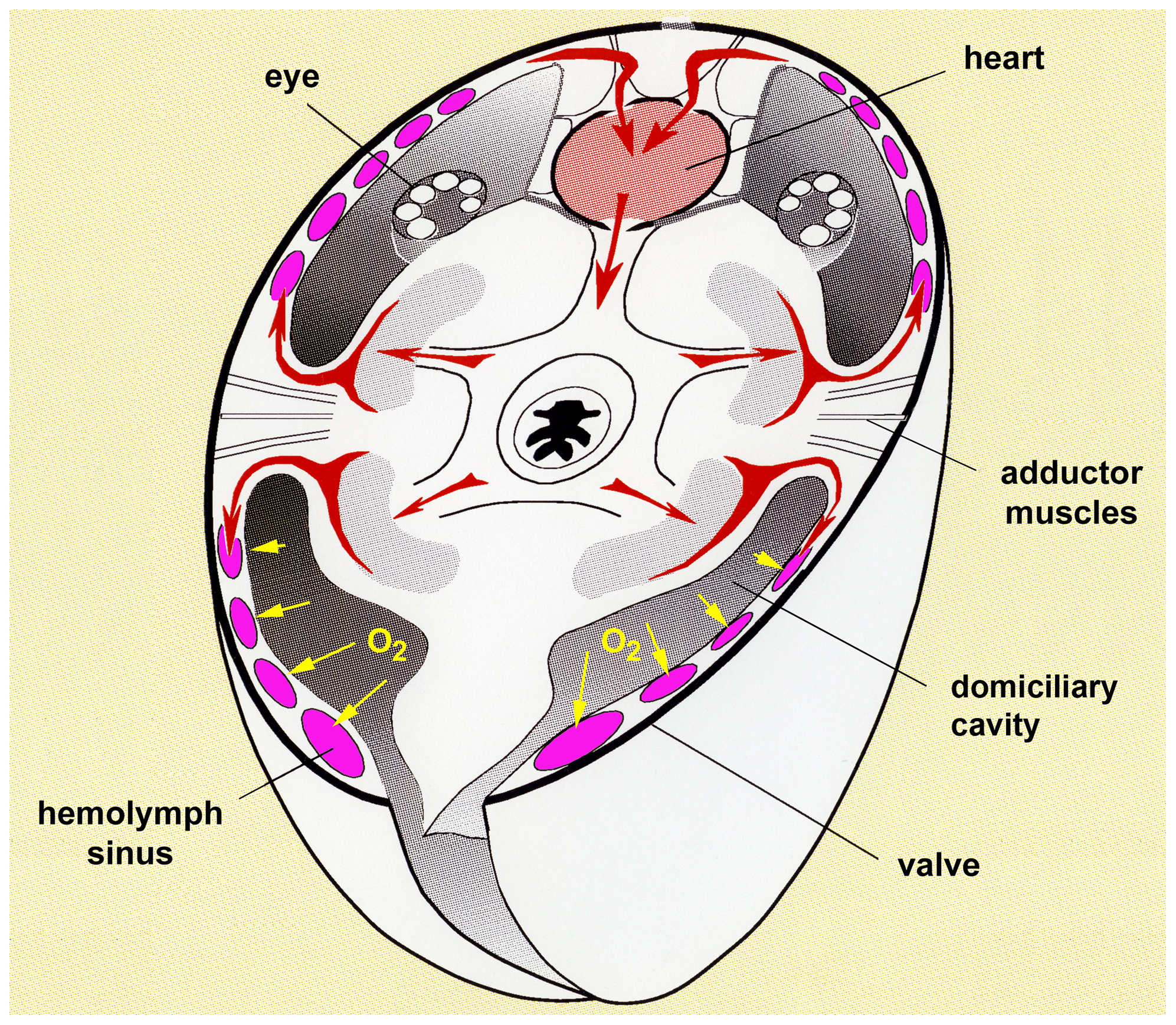

Arthropods have open

Arthropods have open circulatory system

In vertebrates, the circulatory system is a system of organs that includes the heart, blood vessels, and blood which is circulated throughout the body. It includes the cardiovascular system, or vascular system, that consists of the heart ...

s. Most have a few short, open-ended arteries

An artery () is a blood vessel in humans and most other animals that takes oxygenated blood away from the heart in the systemic circulation to one or more parts of the body. Exceptions that carry deoxygenated blood are the pulmonary arteries in ...

. In chelicerates and crustaceans, the blood carries oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

to the tissues, while hexapods use a separate system of tracheae. Many crustaceans and a few chelicerates and tracheates use respiratory pigment

A respiratory pigment is a metalloprotein that serves a variety of important functions, its main being O2 transport. Other functions performed include O2 storage, CO2 transport, and transportation of substances other than respiratory gases. There ...

s to assist oxygen transport. The most common respiratory pigment in arthropods is copper

Copper is a chemical element; it has symbol Cu (from Latin ) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish-orang ...

-based hemocyanin

Hemocyanins (also spelled haemocyanins and abbreviated Hc) are proteins that transport oxygen throughout the bodies of some invertebrate animals. These metalloproteins contain two copper atoms that reversibly bind a single oxygen molecule (O2 ...

; this is used by many crustaceans and a few centipede

Centipedes (from Neo-Latin , "hundred", and Latin , "foot") are predatory arthropods belonging to the class Chilopoda (Ancient Greek , ''kheilos'', "lip", and Neo-Latin suffix , "foot", describing the forcipules) of the subphylum Myriapoda, ...

s. A few crustaceans and insects use iron-based hemoglobin

Hemoglobin (haemoglobin, Hb or Hgb) is a protein containing iron that facilitates the transportation of oxygen in red blood cells. Almost all vertebrates contain hemoglobin, with the sole exception of the fish family Channichthyidae. Hemoglobin ...

, the respiratory pigment used by vertebrate

Vertebrates () are animals with a vertebral column (backbone or spine), and a cranium, or skull. The vertebral column surrounds and protects the spinal cord, while the cranium protects the brain.

The vertebrates make up the subphylum Vertebra ...

s. As with other invertebrates, the respiratory pigments of those arthropods that have them are generally dissolved in the blood and rarely enclosed in corpuscles as they are in vertebrates.

The heart is a muscular tube that runs just under the back and for most of the length of the hemocoel. It contracts in ripples that run from rear to front, pushing blood forwards. Sections not being squeezed by the heart muscle are expanded either by elastic ligament

A ligament is a type of fibrous connective tissue in the body that connects bones to other bones. It also connects flight feathers to bones, in dinosaurs and birds. All 30,000 species of amniotes (land animals with internal bones) have liga ...

s or by small muscle

Muscle is a soft tissue, one of the four basic types of animal tissue. There are three types of muscle tissue in vertebrates: skeletal muscle, cardiac muscle, and smooth muscle. Muscle tissue gives skeletal muscles the ability to muscle contra ...

s, in either case connecting the heart to the body wall. Along the heart run a series of paired ostia, non-return valves that allow blood to enter the heart but prevent it from leaving before it reaches the front.

Arthropods have a wide variety of respiratory systems. Small species often do not have any, since their high ratio of surface area to volume enables simple diffusion through the body surface to supply enough oxygen. Crustacea usually have gills that are modified appendages. Many arachnids have book lung

A book lung is a type of respiration organ used for atmospheric gas-exchange that is present in many arachnids, such as scorpions and spiders. Each of these organs is located inside an open, ventral-abdominal, air-filled cavity (atrium) and co ...

s. Tracheae, systems of branching tunnels that run from the openings in the body walls, deliver oxygen directly to individual cells in many insects, myriapods and arachnid

Arachnids are arthropods in the Class (biology), class Arachnida () of the subphylum Chelicerata. Arachnida includes, among others, spiders, scorpions, ticks, mites, pseudoscorpions, opiliones, harvestmen, Solifugae, camel spiders, Amblypygi, wh ...

s.

Nervous system

Living arthropods have paired main nerve cords running along their bodies below the gut, and in each segment the cords form a pair of

Living arthropods have paired main nerve cords running along their bodies below the gut, and in each segment the cords form a pair of ganglia

A ganglion (: ganglia) is a group of neuron cell bodies in the peripheral nervous system. In the somatic nervous system, this includes dorsal root ganglia and trigeminal ganglia among a few others. In the autonomic nervous system, there a ...

from which sensory

Sensory may refer to:

Biology

* Sensory ecology, how organisms obtain information about their environment

* Sensory neuron, nerve cell responsible for transmitting information about external stimuli

* Sensory perception, the process of acquiri ...

and motor

An engine or motor is a machine designed to convert one or more forms of energy into mechanical energy.

Available energy sources include potential energy (e.g. energy of the Earth's gravitational field as exploited in hydroelectric power gene ...

nerves run to other parts of the segment. Although the pairs of ganglia in each segment often appear physically fused, they are connected by commissure

A commissure () is the location at which two objects wikt:abut#Verb, abut or are joined. The term is used especially in the fields of anatomy and biology.

* The most common usage of the term refers to the brain's commissures, of which there are at ...

s (relatively large bundles of nerves), which give arthropod nervous systems a characteristic ladder-like appearance. The brain is in the head, encircling and mainly above the esophagus. It consists of the fused ganglia of the acron and one or two of the foremost segments that form the head – a total of three pairs of ganglia in most arthropods, but only two in chelicerates, which do not have antennae or the ganglion connected to them. The ganglia of other head segments are often close to the brain and function as part of it. In insects, these other head ganglia combine into a pair of subesophageal ganglia The suboesophageal ganglion (acronym: SOG; synonym: ''subesophageal ganglion'') of arthropods and in particular insects is part of the arthropod central nervous system (CNS). As indicated by its name, it is located ''below the'' ''oesophagus'', ins ...

, under and behind the esophagus. Spiders take this process a step further, as all the segmental ganglia

The segmental ganglia (singular: s. ganglion) are ganglia of the annelid and arthropod central nervous system that lie in the segmented ventral nerve cord

The ventral nerve cord is a major structure of the invertebrate central nervous syste ...

are incorporated into the subesophageal ganglia, which occupy most of the space in the cephalothorax (front "super-segment"). Ruppert, Fox & Barnes (2004), pp. 531–532

Excretory system

There are two different types of arthropod excretory systems. In aquatic arthropods, the end-product of biochemical reactions thatmetabolise

Metabolism (, from ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cellular processes; the co ...

nitrogen

Nitrogen is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a Nonmetal (chemistry), nonmetal and the lightest member of pnictogen, group 15 of the periodic table, often called the Pnictogen, pnictogens. ...

is ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic chemical compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the chemical formula, formula . A Binary compounds of hydrogen, stable binary hydride and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinctive pu ...

, which is so toxic that it needs to be diluted as much as possible with water. The ammonia is then eliminated via any permeable membrane, mainly through the gills. All crustaceans use this system, and its high consumption of water may be responsible for the relative lack of success of crustaceans as land animals. Ruppert, Fox & Barnes (2004), pp. 529–530 Various groups of terrestrial arthropods have independently developed a different system: the end-product of nitrogen metabolism is uric acid

Uric acid is a heterocyclic compound of carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and hydrogen with the Chemical formula, formula C5H4N4O3. It forms ions and salts known as urates and acid urates, such as ammonium acid urate. Uric acid is a product of the meta ...

, which can be excreted as dry material; the Malpighian tubule system

The Malpighian tubule system is a type of excretory and osmoregulatory system found in some insects, myriapods, arachnids and tardigrades. It has also been described in some crustacean species, and is likely the same organ as the posterior cae ...

filters the uric acid and other nitrogenous waste out of the blood in the hemocoel, and dumps these materials into the hindgut, from which they are expelled as feces

Feces (also known as faeces American and British English spelling differences#ae and oe, or fæces; : faex) are the solid or semi-solid remains of food that was not digested in the small intestine, and has been broken down by bacteria in the ...

. Most aquatic arthropods and some terrestrial ones also have organs called nephridia

The nephridium (: nephridia) is an invertebrate organ, found in pairs and performing a function similar to the vertebrate kidneys (which originated from the chordate nephridia). Nephridia remove metabolic wastes from an animal's body. Nephridia co ...

("little kidney

In humans, the kidneys are two reddish-brown bean-shaped blood-filtering organ (anatomy), organs that are a multilobar, multipapillary form of mammalian kidneys, usually without signs of external lobulation. They are located on the left and rig ...

s"), which extract other wastes for excretion as urine

Urine is a liquid by-product of metabolism in humans and many other animals. In placental mammals, urine flows from the Kidney (vertebrates), kidneys through the ureters to the urinary bladder and exits the urethra through the penile meatus (mal ...

.

Senses

The stiff

The stiff cuticle

A cuticle (), or cuticula, is any of a variety of tough but flexible, non-mineral outer coverings of an organism, or parts of an organism, that provide protection. Various types of "cuticle" are non- homologous, differing in their origin, structu ...

s of arthropods would block out information about the outside world, except that they are penetrated by many sensors or connections from sensors to the nervous system. In fact, arthropods have modified their cuticles into elaborate arrays of sensors. Various touch sensors, mostly seta

In biology, setae (; seta ; ) are any of a number of different bristle- or hair-like structures on living organisms.

Animal setae

Protostomes

Depending partly on their form and function, protostome setae may be called macrotrichia, chaetae, ...

e, respond to different levels of force, from strong contact to very weak air currents. Chemical sensors provide equivalents of taste

The gustatory system or sense of taste is the sensory system that is partially responsible for the perception of taste. Taste is the perception stimulated when a substance in the mouth biochemistry, reacts chemically with taste receptor cells l ...

and smell, often by means of setae. Pressure sensors often take the form of membranes that function as eardrum

In the anatomy of humans and various other tetrapods, the eardrum, also called the tympanic membrane or myringa, is a thin, cone-shaped membrane that separates the external ear from the middle ear. Its function is to transmit changes in pres ...

s, but are connected directly to nerves rather than to auditory ossicle

The ossicles (also called auditory ossicles) are three irregular bones in the middle ear of humans and other mammals, and are among the smallest bones in the human body. Although the term "ossicle" literally means "tiny bone" (from Latin ''ossicu ...

s. The antennae of most hexapods include sensor packages that monitor humidity

Humidity is the concentration of water vapor present in the air. Water vapor, the gaseous state of water, is generally invisible to the human eye. Humidity indicates the likelihood for precipitation (meteorology), precipitation, dew, or fog t ...

, moisture and temperature. Ruppert, Fox & Barnes (2004), pp. 532–537

Most arthropods lack balance and acceleration

In mechanics, acceleration is the Rate (mathematics), rate of change of the velocity of an object with respect to time. Acceleration is one of several components of kinematics, the study of motion. Accelerations are Euclidean vector, vector ...

sensors, and rely on their eyes to tell them which way is up. The self-righting behavior of cockroach

Cockroaches (or roaches) are insects belonging to the Order (biology), order Blattodea (Blattaria). About 30 cockroach species out of 4,600 are associated with human habitats. Some species are well-known Pest (organism), pests.

Modern cockro ...

es is triggered when pressure sensors on the underside of the feet report no pressure. However, many malacostracan

Malacostraca is the second largest of the six class (biology), classes of pancrustaceans behind insects, containing about 40,000 living species, divided among 16 order (biology), orders. Its members, the malacostracans, display a great diversity ...

crustaceans have statocyst

The statocyst is a balance sensory receptor present in some aquatic invertebrates, including bivalves, cnidarians, ctenophorans, echinoderms, cephalopods, crustaceans, and gastropods, A similar structure is also found in '' Xenoturbella''. T ...

s, which provide the same sort of information as the balance and motion sensors of the vertebrate inner ear

The inner ear (internal ear, auris interna) is the innermost part of the vertebrate ear. In vertebrates, the inner ear is mainly responsible for sound detection and balance. In mammals, it consists of the bony labyrinth, a hollow cavity in the ...

.

The proprioceptor

Proprioception ( ) is the sense of self-movement, force, and body position.

Proprioception is mediated by proprioceptors, a type of sensory receptor, located within muscles, tendons, and joints. Most animals possess multiple subtypes of propri ...

s of arthropods, sensors that report the force exerted by muscles and the degree of bending in the body and joints, are well understood. However, little is known about what other internal sensors arthropods may have.

Optical

Most arthropods have sophisticated visual systems that include one or more usually both ofcompound eye

A compound eye is a Eye, visual organ found in arthropods such as insects and crustaceans. It may consist of thousands of ommatidium, ommatidia, which are tiny independent photoreception units that consist of a cornea, lens (anatomy), lens, and p ...

s and pigment-cup ocelli

A simple eye or ocellus (sometimes called a pigment pit) is a form of eye or an optical arrangement which has a single lens without the sort of elaborate retina that occurs in most vertebrates. These eyes are called "simple" to distinguish the ...

("little eyes"). In most cases, ocelli are only capable of detecting the direction from which light is coming, using the shadow cast by the walls of the cup. However, the main eyes of spider

Spiders (order (biology), order Araneae) are air-breathing arthropods that have eight limbs, chelicerae with fangs generally able to inject venom, and spinnerets that extrude spider silk, silk. They are the largest order of arachnids and ran ...

s are pigment-cup ocelli that are capable of forming images, and those of jumping spider

Jumping spiders are a group of spiders that constitute the family (biology), family Salticidae. , this family contained over 600 species description, described genus, genera and over 6,000 described species, making it the largest family of spide ...

s can rotate to track prey.

Compound eyes consist of fifteen to several thousand independent ommatidia

The compound eyes of arthropods like insects, crustaceans and millipedes are composed of units called ommatidia (: ommatidium). An ommatidium contains a cluster of photoreceptor cells surrounded by support cells and pigment cells. The outer part ...

, columns that are usually hexagon

In geometry, a hexagon (from Greek , , meaning "six", and , , meaning "corner, angle") is a six-sided polygon. The total of the internal angles of any simple (non-self-intersecting) hexagon is 720°.

Regular hexagon

A regular hexagon is de ...

al in cross section

Cross section may refer to:

* Cross section (geometry)

** Cross-sectional views in architecture and engineering 3D

*Cross section (geology)

* Cross section (electronics)

* Radar cross section, measure of detectability

* Cross section (physics)

**A ...

. Each ommatidium is an independent sensor, with its own light-sensitive cells and often with its own lens

A lens is a transmissive optical device that focuses or disperses a light beam by means of refraction. A simple lens consists of a single piece of transparent material, while a compound lens consists of several simple lenses (''elements'') ...

and cornea

The cornea is the transparency (optics), transparent front part of the eyeball which covers the Iris (anatomy), iris, pupil, and Anterior chamber of eyeball, anterior chamber. Along with the anterior chamber and Lens (anatomy), lens, the cornea ...

. Compound eyes have a wide field of view, and can detect fast movement and, in some cases, the polarization of light

, or , is a property of transverse waves which specifies the geometrical orientation of the oscillations. In a transverse wave, the direction of the oscillation is perpendicular to the direction of motion of the wave. One example of a polarize ...

. On the other hand, the relatively large size of ommatidia makes the images rather coarse, and compound eyes are shorter-sighted than those of birds and mammals – although this is not a severe disadvantage, as objects and events within are most important to most arthropods. Several arthropods have color vision, and that of some insects has been studied in detail; for example, the ommatidia of bees contain receptors for both green and ultra-violet

Ultraviolet radiation, also known as simply UV, is electromagnetic radiation of wavelengths of 10–400 nanometers, shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiation is present in sunlight and constitutes about 10% of the ...

.

Olfaction

Reproduction and development

A few arthropods, such asbarnacle

Barnacles are arthropods of the subclass (taxonomy), subclass Cirripedia in the subphylum Crustacean, Crustacea. They are related to crabs and lobsters, with similar Nauplius (larva), nauplius larvae. Barnacles are exclusively marine invertebra ...

s, are hermaphroditic

A hermaphrodite () is a sexually reproducing organism that produces both male and female gametes. Animal species in which individuals are either male or female are gonochoric, which is the opposite of hermaphroditic.

The individuals of many ...

, that is, each can have the organs of both sex

Sex is the biological trait that determines whether a sexually reproducing organism produces male or female gametes. During sexual reproduction, a male and a female gamete fuse to form a zygote, which develops into an offspring that inheri ...

es. However, individuals of most species remain of one sex their entire lives. A few species of insect

Insects (from Latin ') are Hexapoda, hexapod invertebrates of the class (biology), class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body (Insect morphology#Head, head, ...

s and crustaceans can reproduce by parthenogenesis

Parthenogenesis (; from the Greek + ) is a natural form of asexual reproduction in which the embryo develops directly from an egg without need for fertilization. In animals, parthenogenesis means the development of an embryo from an unfertiliz ...

, especially if conditions favor a "population explosion". However, most arthropods rely on sexual reproduction

Sexual reproduction is a type of reproduction that involves a complex life cycle in which a gamete ( haploid reproductive cells, such as a sperm or egg cell) with a single set of chromosomes combines with another gamete to produce a zygote tha ...

, and parthenogenetic species often revert to sexual reproduction when conditions become less favorable. The ability to undergo meiosis

Meiosis () is a special type of cell division of germ cells in sexually-reproducing organisms that produces the gametes, the sperm or egg cells. It involves two rounds of division that ultimately result in four cells, each with only one c ...