Anatolian Languages on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Anatolian languages are an

The Anatolian branch is often considered the earliest to have split from the Proto-Indo-European language, from a stage referred to either as Indo-Hittite or "Archaic PIE"; typically a date in the mid-4th millennium BC is assumed. Under the Kurgan hypothesis, there are two possibilities for how the early Anatolian speakers could have reached Anatolia: from the north via the Caucasus, and from the west, via the Balkans, the latter of which is considered somewhat more likely by Mallory (1989), Steiner (1990) and Anthony (2007). Statistical research by Quentin Atkinson and others using

The Anatolian branch is often considered the earliest to have split from the Proto-Indo-European language, from a stage referred to either as Indo-Hittite or "Archaic PIE"; typically a date in the mid-4th millennium BC is assumed. Under the Kurgan hypothesis, there are two possibilities for how the early Anatolian speakers could have reached Anatolia: from the north via the Caucasus, and from the west, via the Balkans, the latter of which is considered somewhat more likely by Mallory (1989), Steiner (1990) and Anthony (2007). Statistical research by Quentin Atkinson and others using

Kloekhorst (2022) has proposed a more detailed classification, with estimated dating for some of the reconstructed stages:

* Proto-Anatolian (diverged around the 31st century BCE)

** Proto-Luwo-Lydian

*** Proto-Luwo-Palaic

**** Proto-Luwic (ca. 21st–20th century BCE)

***** Proto-Luwian (ca. 18th century BCE)

****** Cuneiform Luwian (16th–15th century BCE)

****** Hieroglyphic Luwian (13th–8th century BCE)

***** Proto-Lyco-Carian

****** Carian (7th–3rd century BCE)

****** Milyan (5th century BCE)

****** Lycian (5th–4th century BCE)

****** Sidetic (5th–2nd century BCE)

***** Pisidian (1st–2nd century CE), whose exact position remains uncertain (from a direct descendant or a sister-language of Proto-Lyco-Carian)

****Proto-Palaic

*****Palaic (16th–15th century BCE)

***Proto-Lydian

****Lydian (8th–3rd century BCE)

**Proto-Hittite (ca. 2100 BCE)

*** Kanišite Hittite (ca. 1935–1710 BCE)

*** Hittite (ca. 1650–1180 BCE)

Kloekhorst (2022) has proposed a more detailed classification, with estimated dating for some of the reconstructed stages:

* Proto-Anatolian (diverged around the 31st century BCE)

** Proto-Luwo-Lydian

*** Proto-Luwo-Palaic

**** Proto-Luwic (ca. 21st–20th century BCE)

***** Proto-Luwian (ca. 18th century BCE)

****** Cuneiform Luwian (16th–15th century BCE)

****** Hieroglyphic Luwian (13th–8th century BCE)

***** Proto-Lyco-Carian

****** Carian (7th–3rd century BCE)

****** Milyan (5th century BCE)

****** Lycian (5th–4th century BCE)

****** Sidetic (5th–2nd century BCE)

***** Pisidian (1st–2nd century CE), whose exact position remains uncertain (from a direct descendant or a sister-language of Proto-Lyco-Carian)

****Proto-Palaic

*****Palaic (16th–15th century BCE)

***Proto-Lydian

****Lydian (8th–3rd century BCE)

**Proto-Hittite (ca. 2100 BCE)

*** Kanišite Hittite (ca. 1935–1710 BCE)

*** Hittite (ca. 1650–1180 BCE)

Hittite (''nešili'') was the language of the Hittite Empire, dated approximately 1650–1200 BC, which ruled over nearly all of Anatolia during that time. The earliest sources of Hittite are the 19th century BC Kültepe texts, the

Hittite (''nešili'') was the language of the Hittite Empire, dated approximately 1650–1200 BC, which ruled over nearly all of Anatolia during that time. The earliest sources of Hittite are the 19th century BC Kültepe texts, the

The Luwian language is attested in two different scripts,

The Luwian language is attested in two different scripts,

Lycian (called "Lycian A" when Milyan was a "Lycian B") was spoken in classical Lycia, in southwestern Anatolia. It is attested from 172 inscriptions, mainly on stone, from about 150 funerary monuments, and 32 public documents. The writing system is the Lycian alphabet, which the Lycians modified from the Greek alphabet. In addition to the inscriptions are 200 or more coins stamped with Lycian names. Of the texts, some are bilingual in Lycian and Greek, and one, the Létôon trilingual, is in Lycian, Greek, and Aramaic. The longest text, the

Lycian (called "Lycian A" when Milyan was a "Lycian B") was spoken in classical Lycia, in southwestern Anatolia. It is attested from 172 inscriptions, mainly on stone, from about 150 funerary monuments, and 32 public documents. The writing system is the Lycian alphabet, which the Lycians modified from the Greek alphabet. In addition to the inscriptions are 200 or more coins stamped with Lycian names. Of the texts, some are bilingual in Lycian and Greek, and one, the Létôon trilingual, is in Lycian, Greek, and Aramaic. The longest text, the

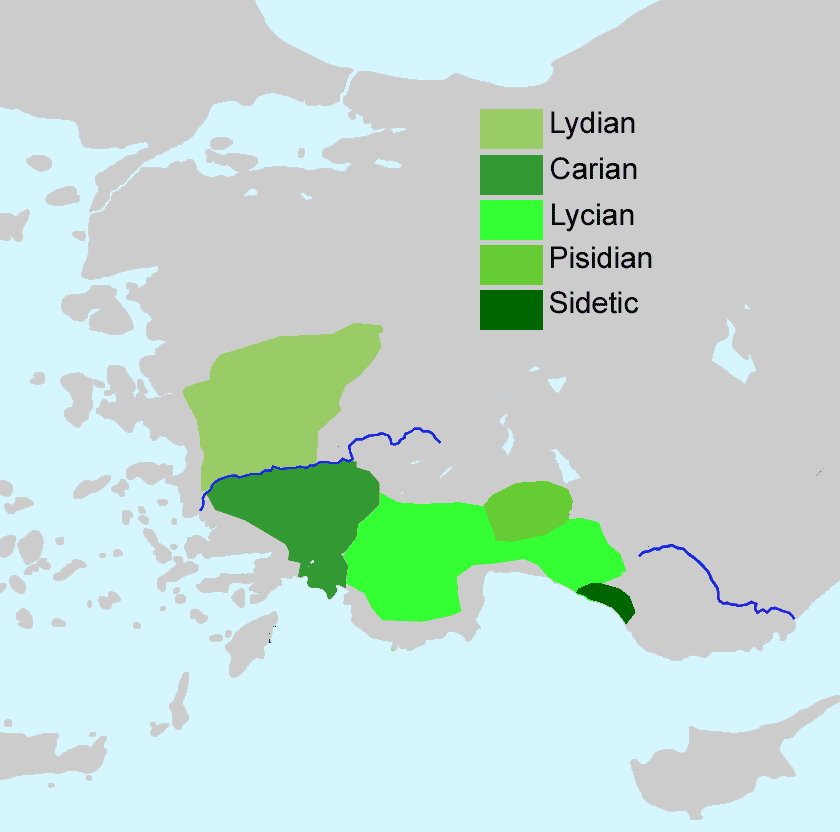

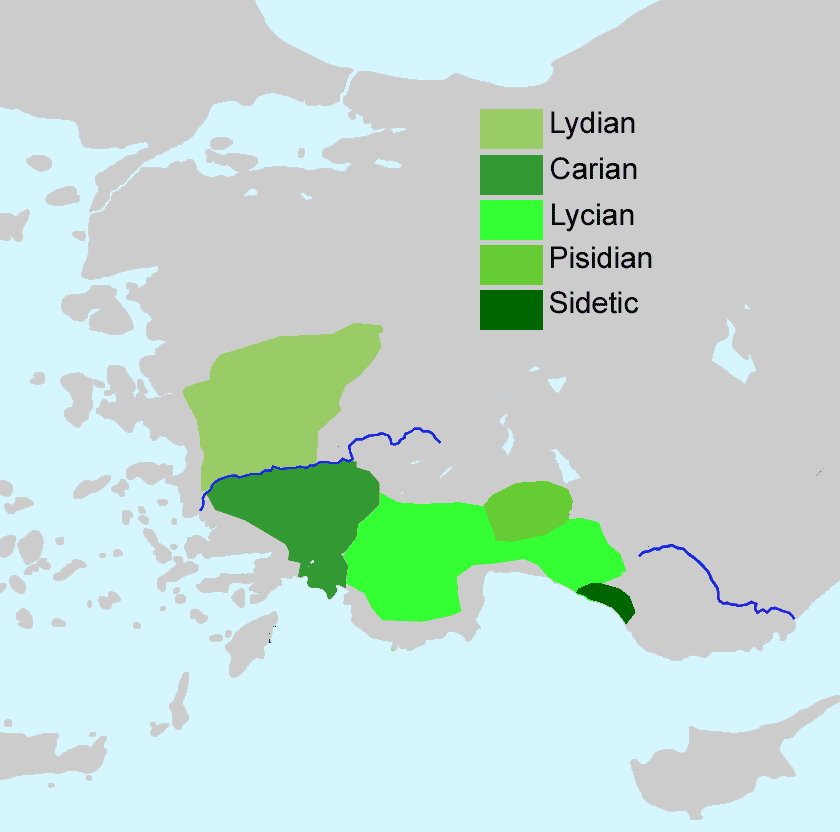

Sidetic was spoken in the city of Side. It is known from coin legends and bilingual inscriptions that date from the 5th–2nd century BC.

Sidetic was spoken in the city of Side. It is known from coin legends and bilingual inscriptions that date from the 5th–2nd century BC.

extinct

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds (taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of the species, although the capacity to breed and ...

branch of Indo-European languages that were spoken in Anatolia, part of present-day Turkey. The best known Anatolian language is Hittite, which is considered the earliest-attested Indo-European language.

Undiscovered until the late 19th and 20th centuries, they are often believed to be the earliest branch to have split from the Indo-European family. Once discovered, the presence of laryngeal consonants ''ḫ'' and ''ḫḫ'' in Hittite and Luwian provided support for the laryngeal theory of Proto-Indo-European linguistics. While Hittite attestation ends after the Bronze Age, hieroglyphic Luwian survived until the conquest of the Neo-Hittite kingdoms

The states that are called Syro-Hittite, Neo-Hittite (in older literature), or Luwian-Aramean (in modern scholarly works), were Luwian and Aramean regional polities of the Iron Age, situated in southeastern parts of modern Turkey and northwestern ...

by Assyria, and alphabetic inscriptions in Anatolian languages are fragmentarily attested until the early first millennium AD, eventually succumbing to the Hellenization of Anatolia.

Origins

The Anatolian branch is often considered the earliest to have split from the Proto-Indo-European language, from a stage referred to either as Indo-Hittite or "Archaic PIE"; typically a date in the mid-4th millennium BC is assumed. Under the Kurgan hypothesis, there are two possibilities for how the early Anatolian speakers could have reached Anatolia: from the north via the Caucasus, and from the west, via the Balkans, the latter of which is considered somewhat more likely by Mallory (1989), Steiner (1990) and Anthony (2007). Statistical research by Quentin Atkinson and others using

The Anatolian branch is often considered the earliest to have split from the Proto-Indo-European language, from a stage referred to either as Indo-Hittite or "Archaic PIE"; typically a date in the mid-4th millennium BC is assumed. Under the Kurgan hypothesis, there are two possibilities for how the early Anatolian speakers could have reached Anatolia: from the north via the Caucasus, and from the west, via the Balkans, the latter of which is considered somewhat more likely by Mallory (1989), Steiner (1990) and Anthony (2007). Statistical research by Quentin Atkinson and others using Bayesian inference

Bayesian inference is a method of statistical inference in which Bayes' theorem is used to update the probability for a hypothesis as more evidence or information becomes available. Bayesian inference is an important technique in statistics, a ...

and glottochronological markers favors an Indo-European origin in Anatolia, though the method's validity and accuracy are subject to debate.

Classification

Melchert (2012) has proposed the following classification: *Proto-Anatolian

Proto-Anatolian is the proto-language from which the ancient Anatolian languages emerged (i.e. Hittite and its closest relatives). As with almost all other proto-languages, no attested writings have been found; the language has been reconstruc ...

** Hittite

** Luwic

*** Luwian

*** Carian

*** Milyan

*** Lycian

*** Sidetic

*** Pisidian

** Palaic

** Lydian

Features

Phonology

The phonology of the Anatolian languages preserves distinctions lost in its sister branches of Indo-European. Famously, the Anatolian languages retain the PIE laryngeals in words such as Hittite ''ḫāran-'' (cf. Greek ὄρνῑς,Lithuanian

Lithuanian may refer to:

* Lithuanians

* Lithuanian language

* The country of Lithuania

* Grand Duchy of Lithuania

* Culture of Lithuania

* Lithuanian cuisine

* Lithuanian Jews as often called "Lithuanians" (''Lita'im'' or ''Litvaks'') by other Jew ...

''eręlis'', Old Norse ''ǫrn'', PIE *h₃éron-) and Lycian 𐊜𐊒𐊄𐊀 ''χuga'' (cf. Latin ''avus'', Old Prussian ''awis'', Archaic Irish ᚐᚃᚔ (avi), PIE *h₂éwh₂s). The three dorsal consonant series of PIE also remained distinct in Proto-Anatolian and have different reflexes in the Luwic languages, e.g. Luwian where *kʷ > ''ku-'', *k > ''k-'', and *ḱ > ''z-.'' The three-way distinction in Proto-Indo-European stops (i.e. *p, *b, *bʰ) collapsed into a fortis-lenis

In linguistics, fortis and lenis ( and ; Latin for "strong" and "weak"), sometimes identified with tense and lax, are pronunciations of consonants with relatively greater and lesser energy, respectively. English has fortis consonants, such as the ...

distinction in Proto-Anatolian, conventionally written as /p/ vs. /b/. In Hittite and Luwian cuneiform, the lenis stops were written as single voiceless consonants while the fortis stops were written as doubled voiceless, indicating a geminated

In phonetics and phonology, gemination (), or consonant lengthening (from Latin 'doubling', itself from '' gemini'' 'twins'), is an articulation of a consonant for a longer period of time than that of a singleton consonant. It is distinct fr ...

pronunciation. By the first millennium, the lenis consonants seem to have been spirantized in Lydian, Lycian, and Carian.

The Proto-Anatolian laryngeal consonant *H patterned with the stops in fortition and lenition and appears as geminated -ḫḫ- or plain -ḫ- in cuneiform. Reflexes of *H in Hittite are interpreted as pharyngeal fricatives and those in Luwian as uvular fricatives based on loans in Ugaritic and Egyptian, as well as vowel-coloring effects. The laryngeals were lost in Lydian but became Lycian 𐊐 (''χ'') and Carian 𐊼 (''k''), both pronounced as well as labiovelars —Lycian 𐊌 (''q''), Carian 𐊴 (''q'')—when labialized. Suggestions for their realization in Proto-Anatolian include pharyngeal fricatives, uvular fricatives, or uvular stops.

Verbs

Despite their antiquity, Anatolian morphology is considerably simpler than other early Indo-European (IE) languages. The verbal system distinguishes only two tenses (present-future and preterite), two voices (active and mediopassive), and two moods ( indicative and imperative), lacking thesubjunctive

The subjunctive (also known as conjunctive in some languages) is a grammatical mood, a feature of the utterance that indicates the speaker's attitude towards it. Subjunctive forms of verbs are typically used to express various states of unreality ...

and optative moods found in other old IE languages like Tocharian, Sanskrit, and Ancient Greek. Anatolian verbs are also typically divided into two conjugations: the ''mi'' conjugation and ''ḫi'' conjugation, named for their first-person singular present indicative suffix in Hittite. While the ''mi'' conjugation has clear cognates outside of Anatolia, the ''ḫi'' conjugation is distinctive and appears to be derived from a reduplicated or intensive form in PIE.

Gender

The Anatolian gender system is based on two classes: animate and inanimate (also termed common and neuter). Proto-Anatolian almost certainly did not inherit a separate feminine agreement class from PIE. The two-gender system has been described as a merger of masculine and feminine genders following the phonetic merger of PIE a-stems with o-stems. However the discovery of a group of inherited nouns with suffix *-eh2 in Lycian and therefore Proto-Anatolian raised doubts about the existence of a feminine gender in PIE. The feminine gender typically marked with ''-ā'' in non-Anatolian Indo-European languages may be connected to a derivational suffix *-h2, attested for abstract nouns and collectives in Anatolian. The appurtenance suffix *''-ih2'' is scarce in Anatolian but fully productive as a feminine marker in Tocharian. This suggests the Anatolian gender system is the original for IE, while the feminine-masculine-neuter classification of Tocharian + Core IE languages may have arisen following a sex-based split within the class of topical nouns to provide more precise reference tracking for male and female humans.Case

Proto-Anatolian retained the nominal case system of Proto-Indo-European, including the vocative, nominative, accusative, instrumental, dative, genitive, and locative cases, and innovated an additional allative case. Nouns distinguish singular and plural numbers, as well as a collective plural for inanimates in Old Hittite and remnant dual forms for natural pairs. The Anatolian branch also has a split-ergative system based on gender, with inanimate nouns being marked in the ergative case when the subject of a transitive verb. This may be an areal influence from nearby non-IE ergative languages like Hurrian.Syntax

The basic word order in Anatolian is subject-object-verb except for Lycian, where verbs typically precede objects. Clause-initial particles are a striking feature of Anatolian syntax; in a given sentence, a connective or the first accented word usually hosts a chain of clitics in Wackernagel's position. Enclitic pronouns, discourse markers, conjunctions, and local or modal particles appear in rigidly ordered slots. Words fronted before the particle chain are topicalized.Languages

The list below gives the Anatolian languages in a relatively flat arrangement, following a summary of the Anatolian family tree byRobert Beekes

Robert Stephen Paul Beekes (; 2 September 1937 – 21 September 2017) was a Dutch linguist who was emeritus professor of Comparative Indo-European Linguistics at Leiden University and an author of many monographs on the Proto-Indo-European la ...

(2010). This model recognizes only one clear subgroup, the Luwic languages. Modifications and updates of the branching order continue, however. A second version opposes Hittite to Western Anatolian, and divides the latter node into Lydian, Palaic, and a Luwian group (instead of Luwic).

Hittite

Akkadian language

Akkadian (, Akkadian: )John Huehnergard & Christopher Woods, "Akkadian and Eblaite", ''The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World's Ancient Languages''. Ed. Roger D. Woodard (2004, Cambridge) Pages 218-280 is an extinct East Semitic language th ...

records of the ''kârum kaneš'', or "port of Kanes," an Assyrian enclave of merchants within the city of ''kaneš'' (Kültepe). This collection records Hittite names and words loaned into Akkadian from Hittite. The Hittite name for the city was '' Neša'', from which the Hittite endonym

An endonym (from Greek: , 'inner' + , 'name'; also known as autonym) is a common, ''native'' name for a geographical place, group of people, individual person, language or dialect, meaning that it is used inside that particular place, group, ...

for the language, ''Nešili'', was derived. The fact that the enclave was Assyrian, rather than Hittite, and that the city name became the language name, suggest that the Hittites were already in a position of influence, perhaps dominance, in central Anatolia.

The main cache of Hittite texts is the approximately 30,000 clay tablet fragments, of which only some have been studied, from the records of the royal city of ''Hattuša

Hattusa (also Ḫattuša or Hattusas ; Hittite: URU''Ḫa-at-tu-ša'', Turkish: Hattuşaş , Hattic: Hattush) was the capital of the Hittite Empire in the late Bronze Age. Its ruins lie near modern Boğazkale, Turkey, within the great loop of ...

'', located on a ridge near what is now Boğazkale, Turkey (formerly named Boğazköy). The records show a gradual rise to power of the Anatolian language speakers over the native Hattians, until at last the kingship became an Anatolian privilege. From then on, little is heard of the Hattians, but the Hittites kept the name. The records include rituals, medical writings, letters, laws and other public documents, making possible an in-depth knowledge of many aspects of the civilization.

Most of the records are dated to the 13th century BC (Late Bronze Age). They are written in cuneiform

Cuneiform is a logo- syllabic script that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Middle East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. It is named for the characteristic wedg ...

script borrowing heavily from the Mesopotamian system of writing. The script is a syllabary

In the linguistic study of written languages, a syllabary is a set of written symbols that represent the syllables or (more frequently) moras which make up words.

A symbol in a syllabary, called a syllabogram, typically represents an (optiona ...

. This fact, combined with frequent use of Akkadian and Sumerian

Sumerian or Sumerians may refer to:

*Sumer, an ancient civilization

**Sumerian language

**Sumerian art

**Sumerian architecture

**Sumerian literature

**Cuneiform script, used in Sumerian writing

*Sumerian Records, an American record label based in ...

words, as well as logograms, or signs representing whole words, to represent lexical items, often introduces considerable uncertainty as to the form of the original. However, phonetic syllable signs are present also, representing syllables of the form V, CV, VC, CVC, where V is "vowel" and C is "consonant."

Hittite is divided into Old, Middle, and New (or Neo-). The dates are somewhat variable. They are based on an approximate coincidence of historical periods and variants of the writing system: the Old Kingdom and the Old Script, the Middle Kingdom and the Middle Script, and the New Kingdom and the New Script. Fortson gives the dates, which come from the reigns of the relevant kings, as 1570–1450 BC, 1450–1380 BC, and 1350–1200 BC respectively. These are not glottochronologic. All cuneiform Hittite came to an end at 1200 BC with the destruction of Hattusas and the end of the empire.

Palaic

Palaic, spoken in the north-central Anatolian region ofPalā

Pala (cuneiform ''pa-la-a'') was a Bronze Age country in Northern Anatolia. Little is known of Pala except its native Palaic language and its native religion. The only known person of Palaic origin was the ritual priestess Anna. Their language sha ...

(later Paphlagonia), extinct around the 13th century BC, is known only from fragments of quoted prayers in Old Hittite texts. It was extinguished by the replacement of the culture, if not the population, as a result of an invasion by the Kaskas, which the Hittites could not prevent.

Luwic branch

The term Luwic was proposed byCraig Melchert

Harold Craig Melchert (born April 5, 1945) is an American linguist known particularly for his work on the Anatolian branch of Indo-European.

Biography

He received his B.A. in German from Michigan State University in 1967 and his Ph.D. in Lingui ...

as the node of a branch to include several languages that seem more closely related than the other Anatolian languages. This is not a neologism, as ''Luvic'' had been used in the early 20th century AD to mean the Anatolian language group as a whole, or languages identified as Luvian by the Hittite texts. The name comes from Hittite ''luwili''. The earlier use of ''Luvic'' fell into disuse in favor of ''Luvian''. Meanwhile, most of the languages now termed Luvian, or Luvic, were not known to be so until the latter 20th century AD. Even more fragmentary attestations might be discovered in the future.

''Luvian'' and ''Luvic'' have other meanings in English, so currently ''Luwian'' and ''Luwic'' are preferred. Before the term ''Luwic'' was proposed for Luwian and its closest relatives, scholars used the term Luwian Languages in the sense of "Luwic Languages". For example, Silvia Luraghi's Luwian branch begins with a root language she terms the "Luwian Group", which logically is in the place of Common Luwian or Proto-Luwian. Its three offsprings, according to her, are Milyan, Proto-Luwian, and Lycian, while Proto-Luwian branches into Cuneiform and Hieroglyphic Luwian..

Luwian

cuneiform

Cuneiform is a logo- syllabic script that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Middle East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. It is named for the characteristic wedg ...

and Anatolian hieroglyph

Anatolian hieroglyphs are an indigenous logographic script native to central Anatolia, consisting of some 500 signs. They were once commonly known as Hittite hieroglyphs, but the language they encode proved to be Luwian, not Hittite, and the ...

s, over more than a millennium. While the earlier scholarship tended to treat these two corpora as separate linguistic entities, the current tendency is to separate genuine dialectal distinctions within Luwian from orthographic differences. Accordingly, one now frequently speaks of Kizzuwatna Luwian (attested in cuneiform transmission), Empire Luwian (cuneiform and hieroglyphic transmission), and Iron Age Luwian / Late Luwian (hieroglyphic transmission), as well as several more Luwian dialects, which are more scarcely attested.

The cuneiform corpus (Melchert's CLuwian) is recorded in glosses and short passages in Hittite texts, mainly from Boğazkale. About 200 tablet fragments of the approximately 30,000 contain CLuwian passages. Most of the tablets reflect the Middle and New Script, although some Old Script fragments have also been attested. Benjamin Fortson hypothesizes that "Luvian was employed in rituals adopted by the Hittites." A large proportion of tablets containing Luwian passages reflect rituals emanating from Kizzuwatna. On the other hand, many Luwian glosses (foreign words) in Hittite texts appear to reflect a different dialect, namely Empire Luwian. The Hittite language of the respective tablets sometimes displays interference features, which suggests that they were recorded by Luwian native speakers.

The hieroglyphic corpus (Melchert's HLuwian) is recorded in Anatolian hieroglyph

Anatolian hieroglyphs are an indigenous logographic script native to central Anatolia, consisting of some 500 signs. They were once commonly known as Hittite hieroglyphs, but the language they encode proved to be Luwian, not Hittite, and the ...

s, reflecting Empire Luwian and its descendant Iron Age Luwian. Some HLuwian texts were found at Boğazkale, so it was formerly thought to have been a "Hieroglyphic Hittite." The contexts in which CLuwian and HLuwian have been found are essentially distinct. Annick Payne asserts: "With the exception of digraphic seals, the two scripts were never used together."

HLuwian texts are found on clay, shell, potsherds, pottery, metal, natural rock surfaces, building stone and sculpture, mainly carved lions. The images are in relief or counter-relief that can be carved or painted. There are also seals and sealings. A sealing is a counter-relief impression of hieroglyphic signs carved or cast in relief on a seal. The resulting signature can be stamped or rolled onto a soft material, such as sealing wax. The HLuwian writing system contains about 500 signs, 225 of which are logograms, and the rest purely functional determinatives and syllabograms, representing syllables of the form V, CV, or rarely CVCV.

HLuwian texts appear as early as the 14th century BC in names and titles on seals and sealings at Hattusa. Longer texts first appear in the 13th century BC. Payne refers to the Bronze Age HLuwian as Empire Luwian. All Hittite and CLuwian came to an end at 1200 BC as part of the Late Bronze Age collapse

The Late Bronze Age collapse was a time of widespread societal collapse during the 12th century BC, between c. 1200 and 1150. The collapse affected a large area of the Eastern Mediterranean (North Africa and Southeast Europe) and the Near East ...

, but the concept of a "fall" of the Hittite Empire must be tempered in regard to the south, where the civilization of a number of Syro-Hittite states went on uninterrupted, using HLuwian, which Payne calls Iron-Age Luwian and dates 1000–700 BC. Presumably these autonomous "Neo-Hittite" heads of state no longer needed to report to Hattusa. HLuwian caches come from ten city states in northern Syria and southern Anatolia: Cilicia

Cilicia (); el, Κιλικία, ''Kilikía''; Middle Persian: ''klkyʾy'' (''Klikiyā''); Parthian: ''kylkyʾ'' (''Kilikiyā''); tr, Kilikya). is a geographical region in southern Anatolia in Turkey, extending inland from the northeastern coas ...

, Charchamesh, Tell Akhmar, Maras, Malatya, Commagene, Amuq

The Amik Valley ( tr, Amik Ovası; ar, ٱلْأَعْمَاق, al-ʾAʿmāq) is located in the Hatay Province, close to the city of Antakya ( Antioch on the Orontes River) in the southern part of Turkey. Along with Dabiq in northwestern Syria ...

, Aleppo

)), is an adjective which means "white-colored mixed with black".

, motto =

, image_map =

, mapsize =

, map_caption =

, image_map1 =

...

, Hama

, timezone = EET

, utc_offset = +2

, timezone_DST = EEST

, utc_offset_DST = +3

, postal_code_type =

, postal_code =

, ar ...

, and Tabal.

Lycian

Lycian (called "Lycian A" when Milyan was a "Lycian B") was spoken in classical Lycia, in southwestern Anatolia. It is attested from 172 inscriptions, mainly on stone, from about 150 funerary monuments, and 32 public documents. The writing system is the Lycian alphabet, which the Lycians modified from the Greek alphabet. In addition to the inscriptions are 200 or more coins stamped with Lycian names. Of the texts, some are bilingual in Lycian and Greek, and one, the Létôon trilingual, is in Lycian, Greek, and Aramaic. The longest text, the

Lycian (called "Lycian A" when Milyan was a "Lycian B") was spoken in classical Lycia, in southwestern Anatolia. It is attested from 172 inscriptions, mainly on stone, from about 150 funerary monuments, and 32 public documents. The writing system is the Lycian alphabet, which the Lycians modified from the Greek alphabet. In addition to the inscriptions are 200 or more coins stamped with Lycian names. Of the texts, some are bilingual in Lycian and Greek, and one, the Létôon trilingual, is in Lycian, Greek, and Aramaic. The longest text, the Xanthus stele Xanthus (; grc, Ξάνθος, ''Xanthos'', "yellow, blond") or Xanthos may refer to:

In Greek mythology

* Xanthos (King of Thebes), the son of Ptolemy, killed by Andropompus or Melanthus

* Xanthus (mythology), several figures, including gods, men ...

, with about 250 lines, was originally believed to be bilingual in Greek and Lycian; however the identification of a verse in another, closely related language, a "Lycian B" identified now as Milyan, renders the stele trilingual. The earliest of the coins date before 500 BC; however, the writing system must have required time for its development and implementation.

The name of Lycia appears in Homer but more historically, in Hittite and in Egyptian documents among the " Sea Peoples", as the Lukka, dwelling in the Lukka lands. No Lycian text survives from Late Bronze Age times, but the names offer a basis for postulating its continued existence.

Lycia was completely Hellenized by the end of the 4th century BC, after which Lycian is not to be found. Stephen Colvin goes so far as to term this, and the other scantily attested Luwic languages, "Late Luwian", although they probably did not begin late. Analogously, Ivo Hajnal

Ivo Hajnal (born 1961 in Zürich) is a Swiss–Austrian philologist and linguist, specialized in Indo-European studies and Mycenaean Greek.

Hajnal studied Indo-European linguistics and philology at the University of Zurich, and received his PhD ...

calls them – using an equivalent German term – ''Jungluwisch''.

Milyan

Milyan was previously considered a variety of Lycian, as "Lycian B", but it is now classified as a separate language.Carian

Carian was spoken in Caria. It is fragmentarily attested from graffiti by Carian mercenaries and other members of an ethnic enclave inMemphis, Egypt

, alternate_name =

, image =

, alt =

, caption = Ruins of the pillared hall of Ramesses IIat Mit Rahina

, map_type = Egypt#Africa

, map_alt =

, map_size =

, relief =

, coordinates = ...

(and other places in Egypt), personal names in Greek records, twenty inscriptions from Caria (including four bilingual inscriptions), scattered inscriptions elsewhere in the Aegean world and words stated as Carian by ancient authors. Inscriptions first appeared in the 7th century BC.

Sidetic

Sidetic was spoken in the city of Side. It is known from coin legends and bilingual inscriptions that date from the 5th–2nd century BC.

Sidetic was spoken in the city of Side. It is known from coin legends and bilingual inscriptions that date from the 5th–2nd century BC.

Pisidian

The Pisidic language was spoken in Pisidia. Known from some thirty short inscriptions from the first to second centuries AD, it appears to be closely related to Lycian and Sidetic.Lydian

Lydian was spoken inLydia

Lydia (Lydian language, Lydian: 𐤮𐤱𐤠𐤭𐤣𐤠, ''Śfarda''; Aramaic: ''Lydia''; el, Λυδία, ''Lȳdíā''; tr, Lidya) was an Iron Age Monarchy, kingdom of western Asia Minor located generally east of ancient Ionia in the mod ...

. Within the Anatolian group, Lydian occupies a unique and problematic position due, first, to the still very limited evidence and understanding of the language and, second, to a number of features not shared with any other Anatolian language. The Lydian language is attested in graffiti and in coin legends from the end of the 8th or the beginning of the 7th century BC down to the 3rd century BC, but well-preserved inscriptions of significant length are presently limited to the 5th–4th centuries BC, during the period of Persian domination. Extant Lydian texts now number slightly over one hundred but are mostly fragmentary.

Other possible languages

It has been proposed that other languages of the family existed that have left no records, including the pre-Greek languages of Lycaonia andIsauria

Isauria ( or ; grc, Ἰσαυρία), in ancient geography, is a rugged, isolated, district in the interior of Asia Minor, of very different extent at different periods, but generally covering what is now the district of Bozkır and its surrou ...

unattested in the alphabetic era. In these regions, only Hittite, Hurrian, and Luwian are attested in the Bronze Age. Languages of the region such as Mysian and Phrygian are Indo-European but not Anatolian, and are thought to have entered Anatolia from the Balkan peninsula at a later date than the Anatolian languages.

Extinction

Anatolia was heavily Hellenized following the conquests ofAlexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

, and the native languages of the area ceased to be spoken in subsequent centuries, making Anatolian the first well-attested branch of Indo-European to become extinct. The only other well-known branch with no living descendants is Tocharian, whose attestation ceases in the 8th century AD.

While Pisidian inscriptions date until the second century AD, the poorly-attested Isaurian language, which was probably a late Luwic dialect, appears to have been the last of the Anatolian languages to become extinct. Epigraphic evidence, including funerary inscriptions dating from as late as the 5th century, has been found by archaeologists.

Personal names with Anatolian etymologies are known from the Hellenistic and Roman era and may have outlasted the languages they came from. Examples include Cilicia

Cilicia (); el, Κιλικία, ''Kilikía''; Middle Persian: ''klkyʾy'' (''Klikiyā''); Parthian: ''kylkyʾ'' (''Kilikiyā''); tr, Kilikya). is a geographical region in southern Anatolia in Turkey, extending inland from the northeastern coas ...

n Ταρκυνδβερρας ''Tarku-ndberras'' "assistance of Tarḫunz", Isauria

Isauria ( or ; grc, Ἰσαυρία), in ancient geography, is a rugged, isolated, district in the interior of Asia Minor, of very different extent at different periods, but generally covering what is now the district of Bozkır and its surrou ...

n Ουαξαμοας ''Ouaxamoas < *Waksa-muwa'' "power of blessing(?)", and Lycaonian Πιγραμος ''Pigramos'' "resplendent, mighty" (cf. Carian 𐊷𐊹𐊼𐊥𐊪𐊸 ''Pikrmś,'' Luwian ''pīhramma/i-'').

Several Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic p ...

words are suggested to be Anatolian borrowings, for example:

*''Apóllōn'' (Doric: ''Apéllōn'', Cypriot: ''Apeílōn''), from *''Apeljōn'', as in Hittite ''Appaliunaš'';

* ''dépas'' 'cup; pot, vessel', Mycenaean ''di-pa'', from Hieroglyphic Luwian ''ti-pa-s'' 'sky; bowl, cup' (cf. Hittite ''nēpis'' 'sky; cup');

* ''eléphās'' 'ivory', from Hittite ''laḫpa'' (itself from Mesopotamia; cf. Phoenician ''ʾlp'', Egyptian ''Ȝbw'');

* ''kýanos'' 'dark blue glaze; enamel', from Hittite ''kuwannan-'' 'copper ore; azurite' (ultimately from Sumerian

Sumerian or Sumerians may refer to:

*Sumer, an ancient civilization

**Sumerian language

**Sumerian art

**Sumerian architecture

**Sumerian literature

**Cuneiform script, used in Sumerian writing

*Sumerian Records, an American record label based in ...

''kù-an'');

* ''kýmbachos'' 'helmet', from Hittite ''kupaḫi'' 'headgear';

* ''kýmbalon'' 'cymbal', from Hittite ''ḫuḫupal'' 'wooden percussion instrument';

* ''mólybdos'' 'lead', Mycenaean ''mo-ri-wo-do'', from *''morkw-io-'' 'dark', as in Lydian ''mariwda(ś)-k'' 'the dark ones';

* ''óbryza'' 'vessel for refining gold', from Hittite ''ḫuprušḫi'' 'vessel';

* ''tolýpē'' 'ball of wool', from Hittite ''taluppa'' 'lump'/'clod' (or Cuneiform Luwian ''taluppa/i'').

A few words in the Armenian language

Armenian ( classical: , reformed: , , ) is an Indo-European language and an independent branch of that family of languages. It is the official language of Armenia. Historically spoken in the Armenian Highlands, today Armenian is widely spoken th ...

have been also suggested as possible borrowings from Hittite or Luwian, such as Arm. զուռնա ''zuṙna'' (compare Luwian ''zurni'' "horn").Martirosyan, Hrach (2017). "Notes on Anatolian loanwords in Armenian." In Pavel S. Avetisyan, Yervand H. Grekyan (eds.), ''Bridging times and spaces: papers in ancient Near Eastern, Mediterranean and Armenian studies: Honouring Gregory E. Areshian on the occasion of his sixty-fifth birthday.'' Oxford: Archaeopress, 293–306.

See also

* Armenian hypothesis * Tree model * Urheimat * Galatian, a Celtic language spoken in AnatoliaNotes

References

* * * * . Originally published as ''Le Lingue Indoeuropee''. * * * * * * * * *Further reading

*External links

* * * * Luwian, Lycian and Lydian. * {{DEFAULTSORT:Anatolian Languages Indo-European languages