Amy Carter on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Amy Lynn Carter (born October 19, 1967) is the only daughter and fourth child of the 39th U.S. president

In January 1977, at the age of nine, Carter entered the White House, where she lived for four years. She was the subject of much media attention during this period. Young children had not lived in the White House since the early 1960s presidency of John F. Kennedy (and would not again do so after the Carter presidency until the inauguration of

In January 1977, at the age of nine, Carter entered the White House, where she lived for four years. She was the subject of much media attention during this period. Young children had not lived in the White House since the early 1960s presidency of John F. Kennedy (and would not again do so after the Carter presidency until the inauguration of  On February 21, 1977, during a

On February 21, 1977, during a

Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (October 1, 1924December 29, 2024) was an American politician and humanitarian who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party ...

and his wife Rosalynn Carter

Eleanor Rosalynn Carter ( ; ; August 18, 1927 – November 19, 2023) was an American activist and humanitarian who served as the first lady of the United States from 1977 to 1981, as the wife of President Jimmy Carter. Throughout her decades of ...

. Carter first entered the public spotlight as a child when she lived in the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest (Washington, D.C.), NW in Washington, D.C., it has served as the residence of every U.S. president ...

during her father's presidency.

Early life

Amy Carter was born on October 19, 1967, inPlains, Georgia

Plains is a city in Sumter County, Georgia, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 573. It is well-known as the home of Jimmy Carter and his wife Rosalynn, who were the 39th president and first lady of the Un ...

. Prior to her birth, the family held a vote whether their parents should try for a baby daughter. According to her brother: "The family voted a year before she was born on whether my parents ought to have a baby daughter, and a year later, there she was. We even picked out her name beforehand—out of a Webster's Dictionary." She was raised in Plains until her father was elected governor of Georgia

The governor of Georgia is the head of government of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia and the commander-in-chief of the state's Georgia National Guard, National Guard, when not in federal service, and Georgia State Defense Force, State Defense Fo ...

in 1970

Events

January

* January 1 – Unix time epoch reached at 00:00:00 UTC.

* January 5 – The 7.1 1970 Tonghai earthquake, Tonghai earthquake shakes Tonghai County, Yunnan province, China, with a maximum Mercalli intensity scale, Mercalli ...

and her family moved into the Georgia Governor's Mansion in Atlanta. In 1976, when she was nine, her father was elected President of the United States, and the family moved to the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest (Washington, D.C.), NW in Washington, D.C., it has served as the residence of every U.S. president ...

. Carter attended public schools in Washington during her four years in the White House; first Stevens Elementary School and then Rose Hardy Middle School. After her father's presidency, Carter moved to Atlanta and spent her senior year of high school at Woodward Academy in College Park, Georgia

College Park is a city in Fulton County, Georgia, Fulton and Clayton County, Georgia, Clayton counties, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia, United States, adjacent to the southern boundary of the city of Atlanta. As of the 2020 United States census, ...

. She was a Senate page during the 1982 summer session. Carter attended Brown University

Brown University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Providence, Rhode Island, United States. It is the List of colonial colleges, seventh-oldest institution of higher education in the US, founded in 1764 as the ' ...

, where she was known for her activism against apartheid and the CIA. She was academically dismissed in 1987, "for failing to keep up with her coursework". Carter later earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts

A Bachelor of Fine Arts (BFA) is a standard undergraduate degree for students pursuing a professional education in the visual arts, Fine art, or performing arts. In some instances, it is also called a Bachelor of Visual Arts (BVA).

Background ...

degree from the Memphis College of Art and a master's degree

A master's degree (from Latin ) is a postgraduate academic degree awarded by universities or colleges upon completion of a course of study demonstrating mastery or a high-order overview of a specific field of study or area of professional prac ...

in art history from Tulane University

The Tulane University of Louisiana (commonly referred to as Tulane University) is a private research university in New Orleans, Louisiana, United States. Founded as the Medical College of Louisiana in 1834 by a cohort of medical doctors, it b ...

in New Orleans in 1996.

Life in the White House

In January 1977, at the age of nine, Carter entered the White House, where she lived for four years. She was the subject of much media attention during this period. Young children had not lived in the White House since the early 1960s presidency of John F. Kennedy (and would not again do so after the Carter presidency until the inauguration of

In January 1977, at the age of nine, Carter entered the White House, where she lived for four years. She was the subject of much media attention during this period. Young children had not lived in the White House since the early 1960s presidency of John F. Kennedy (and would not again do so after the Carter presidency until the inauguration of Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton (né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician and lawyer who was the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, ...

, in January 1993, when Chelsea moved in.)

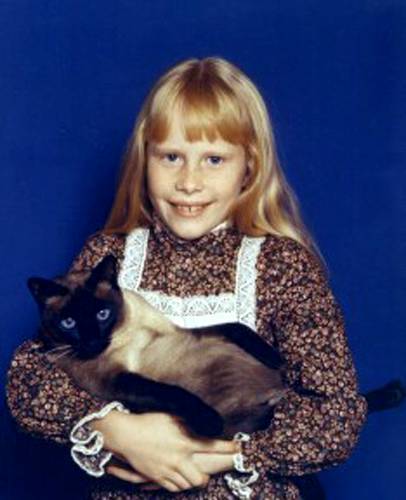

While Carter was in the White House, she had a Siamese cat named Misty Malarky Ying Yang, which was the last cat to occupy the White House until Socks

A sock is a piece of clothing worn on the feet and often covering the ankle or some part of the Calf (leg), calf. Some types of shoes or boots are typically worn over socks. In ancient times, socks were made from leather or matted animal hair. ...

, owned by Clinton. Carter also accepted an elephant from Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, also known historically as Ceylon, is an island country in South Asia. It lies in the Indian Ocean, southwest of the Bay of Bengal, separated from the Indian subcontinent, ...

; the animal was given to the National Zoo in Washington, D.C.

Carter roller-skated through the White House's East Room and had a treehouse on the South Lawn. When she invited friends over for slumber parties in her tree house, Secret Service

A secret service is a government agency, intelligence agency, or the activities of a government agency, concerned with the gathering of intelligence data. The tasks and powers of a secret service can vary greatly from one country to another. For i ...

agents monitored the event from the ground.

Mary Prince (an African American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from an ...

woman wrongly convicted of murder, and later exonerated and pardon

A pardon is a government decision to allow a person to be relieved of some or all of the legal consequences resulting from a criminal conviction. A pardon may be granted before or after conviction for the crime, depending on the laws of the j ...

ed) acted as her nanny

A nanny is a person who provides child care. Typically, this care is given within the children's family setting. Throughout history, nannies were usually servants in large households and reported directly to the lady of the house. Today, modern ...

for most of the period from 1971 until Jimmy Carter's presidency ended, having begun in that position through a prison release program in Georgia.

Carter did not receive the "hands off" treatment that most of the media later afforded to Chelsea Clinton

Chelsea Victoria Clinton (born February 27, 1980) is an American writer. She is the only child of former U.S. President Bill Clinton and Hillary Clinton, a former U.S. Secretary of State and U.S. Senator.

Clinton was born in Little Rock, Ar ...

. President Carter mentioned his daughter during a 1980 debate with Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

, when he said he had asked her what the most important issue in that election was and she said, "the control of nuclear arms

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon), producing a nuclear expl ...

".

On February 21, 1977, during a

On February 21, 1977, during a White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest (Washington, D.C.), NW in Washington, D.C., it has served as the residence of every U.S. president ...

state dinner for Canada's Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau

Joseph Philippe Pierre Yves Elliott Trudeau (October 18, 1919 – September 28, 2000) was a Canadian politician, statesman, and lawyer who served as the 15th prime minister of Canada from 1968 to 1979 and from 1980 to 1984. Between his no ...

, nine-year-old Amy was seen reading two books, '' Charlie and the Great Glass Elevator'' and ''The Story of the Gettysburg Address'', while the formal toasts by her father and Trudeau were exchanged.

Activism

Amy Carter later became known for her political activism. She participated insit-in

A sit-in or sit-down is a form of direct action that involves one or more people occupying an area for a protest, often to promote political, social, or economic change. The protestors gather conspicuously in a space or building, refusing to mo ...

s and protests during the 1980s and early 1990s that were aimed at changing U.S. foreign policy towards South African apartheid

Apartheid ( , especially South African English: , ; , ) was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. It was characterised by an ...

and Central America. Along with activist Abbie Hoffman

Abbot Howard Hoffman (November 30, 1936 – April 12, 1989) was an American political and social activist who co-founded the Youth International Party ("Yippies") and was a member of the Chicago Seven. He was also a leading proponent of the ...

and 13 others, she was arrested, while still a Brown student, during a 1986 demonstration at the University of Massachusetts Amherst

The University of Massachusetts Amherst (UMass Amherst) is a public land-grant research university in Amherst, Massachusetts, United States. It is the flagship campus of the University of Massachusetts system and was founded in 1863 as the ...

for protesting CIA recruitment there. She was acquitted of all charges in a well-publicized trial in Northampton, Massachusetts

The city of Northampton is the county seat of Hampshire County, Massachusetts, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population of Northampton (including its outer villages, Florence, Massachusetts, Florence and ...

. Attorney Leonard Weinglass, who defended Hoffman in the Chicago Seven trial in the 1960s, utilized the necessity

Necessary or necessity may refer to:

Concept of necessity

* Need

** An action somebody may feel they must do

** An important task or essential thing to do at a particular time or by a particular moment

* Necessary and sufficient condition, in l ...

defense, successfully arguing that because the CIA was involved in criminal activity in Central America and other hotspots, preventing it from recruiting on campus was equivalent to trespassing in a burning building.

Other work

Carter gave an interview on ''Late Night with David Letterman

''Late Night with David Letterman'' is an American television talk show broadcast by NBC. The show is the first installment of the '' Late Night''. Hosted by David Letterman, it aired from February1, 1982 to June 25, 1993, and was replaced by ...

'' in 1982. She illustrated '' The Little Baby Snoogle-Fleejer'', her father's book for children, published in 1995.

She is a member of the board of counselors of the Carter Center

The Carter Center is a nongovernmental, nonprofit organization founded in 1982 by former U.S. president Jimmy Carter. He and his wife Rosalynn Carter partnered with Emory University after his defeat in the 1980 United States presidential ele ...

, established by her father, which advocates for human rights

Human rights are universally recognized Morality, moral principles or Social norm, norms that establish standards of human behavior and are often protected by both Municipal law, national and international laws. These rights are considered ...

and diplomacy

Diplomacy is the communication by representatives of State (polity), state, International organization, intergovernmental, or Non-governmental organization, non-governmental institutions intended to influence events in the international syste ...

.

Personal life

From 1996 to 2005, Carter was married to computer consultant James Gregory Wentzel. They have a son, Hugo James Wentzel, who in 2023 was featured on the second season of reality TV competition show '' Claim to Fame''. Since 2007, she has been married to John Joseph "Jay" Kelly. They have a son.In popular culture

''Little House on the Prairie

The ''Little House on the Prairie'' books comprise a series of American children's novels written by Laura Ingalls Wilder (b. Laura Elizabeth Ingalls). The stories are based on her childhood and adulthood in the Midwestern United States, Americ ...

'' actress Alison Arngrim impersonated Carter on the 1977 Laff Records comedy album ''Heeere's Amy''.

See also

* List of children of presidents of the United StatesReferences

External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Carter, Amy 1967 births 20th-century American people 20th-century American women 21st-century American women American activists Brown University alumni A Children of presidents of the United States Georgia (U.S. state) Democrats Living people Memphis College of Art alumni People from Plains, Georgia Politicians from Atlanta Tulane University School of Liberal Arts alumni Woodward Academy alumni